Understanding Suicide: A Brief Psychological Autopsy of Robert E. Howard

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

9 -

download

0

Transcript of Understanding Suicide: A Brief Psychological Autopsy of Robert E. Howard

-------------_._--_ ...---

The William Glasser InstitutePresident & FounderWilliam Glasser, M.D.Executive Director

Linda Harshman22024 Lassen Street, # 118Chatsworth, California 913111-818-700-8000FAX 818-700-05551-800-899-0688

The William Glasser Institute-AustraliaPresident

Lois AndersonP.O. Box 134BurpengaryQueensland 4505Australia

The William Glasser Institute-IrelandDirector

Brian Lennon6 Red IslandSkerriesRepublic of Ireland011-849-9106FAX 011-353-1-849-2461

The Reality Therapy Association in JapanContact Person

Masaki Kakitani2205-23Oiso-MachiKanagawa 255Japan0463-33-8819FAX 0463-61-2434

The WilJiam Glasser Institute-New ZealandPresident

Sharlene PetersenWGI-NZPO Box 130059Christchurch, New ZealandPh 64-3-3264056FAX 64-3-3264057

KART: Korea Association for Reality TherapyChairperson

Rose- Inza Kim707-10, Hannam 2-dongyongsan-gu 140-212Seoul, Korea011-82-2-790-9361 /9362FAX 011-82-2-790-9363email: [email protected]

The William Glasser Institute-CanadaPresident

Ellen B. GelinasP.O. Box 3907St. Andrews. New BrunswickE5B 3S7Canada506-529-3270FAX 506-529-3363e-mail: [email protected]

Association for Reality Therapy-SingaporePresident

Kwee-Hiong Clare Ong, Ph.D.1 Goldhill Plaza# 03-35 Podium BlockSingapore 308899e-mail: wgi-singapore.com

The Institute for Reality Therapy UKContact PersonInstitute Executive Administrator -

Adrian GormanPO Box 227BillingshurstWest Sussex, RH14 OOLUnited KingdomTel: +44(0)1403 700023e-mail: [email protected]: Adrian.Gorman

The Israeli Reality Therapy AssociationContact PersonRefuah InstituteProf. Joshua Ritchie, MD., Dean95 Derech HahoreshJerusalem 97278, Israele-mail: [email protected] 2 5715112Fax: 972 2 5879557web: www.refuah.net

Croatian Association for Reality TherapyPresident

Dubravka StijacicKuslanova 59a10.000 ZagrebCroatia

Reality Therapy Association-SloveniaPres idem

Bojana GobboMorova 296310 IzolaSlovenia3866662706FAX 386 6674 7045

-~~----- ...~~~ -

International Journal of Reality Therapy

Vol XXIX No.1 Fall 2009

Larry Litwack Editor's Comments 3

Cynth ia Pal mer Mason Using Reality Therapy in Schools: 5Jill D. Duba Its Potential Impact on the Effectiveness

of the ASCA National Model

Jill D. Duba The Basic Needs Genogram: 13A Tool to Help Inter-Religious Couples Negotiate

Michael Bell Coaching for a Vision for Leadership 18Sylvia Habel

Adrian Schoo Choice Theory and Choosing Presence: 24Sylvia Habel A Reflection on Needs and the Filters of theMichael Bell Perceptual System

Robert E. Wubbolding 2029: Headline or Footnote? Mainstream or 26Backwater? Cutting Edge or Trai I ing Edge?Included or Excluded from the Professional World?

Leon Lojk 4th European International Conference 30in Edinburgh

Paul Pound Choice Theory and Psychoeducation for Parents 34of Out-Of-Competition Adolescent Athletes

Patrick M. Hillis Suggesting the Quality World Through Student 38Performance Outcomes

The 2009 Glasser Scholars The Impact of the Glasser Scholars Project onParticipants' Teaching and Research Initiatives:Part II

44

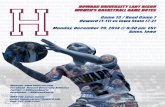

Ron Mottern Understanding Suicide: A Brief PsychologicalAutopsy of Robert E. Howard

54

Katrina Cook The Movie Nanny McPhee and the Magic ofReal ity Therapy

60

Thomas S. ParishGary C. Rehbein

Teaching Strategies and Student Orientation:Match or Mismatch?

63

International Journal of Reality Therapy. Fall 2009 • VoI.XXIX, number 1 • 1

~~~------------. --- ----- - --- --- .---

International Journal of Reality Therapy

Editor: Larry Litwack, Ed. D, ABPP,RTC

Advisory BoardThomas Bratter

Great Barrington, MassachusettsJohn Brickell

London, EnglandElijah Mickel

Washington, D.C.Robert Renna

Waltham, MassachusettsJoshua Ritchie

Jerusalem, IsraelRobert Wubbolding

Cincinnati. OhioAdrian Schoo

Hamilton. Australia

Editorial Office:International Journal of Reality Therapy

650 Laurel Avenue #402Highland Park, IL 60035email: llitwack@aoLcom

The International Journal of Reality Therapy is directed toconcepts of internal control psychology, with particular empha-sis on research, theory, development, or special descriptions ofthe successful application of internal control systems especiallyas exemplified in reality therapy and choice theory.

The International Journal of Reality Therapy is published semi-annually in Fall and Spring. rSSN: 1099-7717.

Material published in the Journal reflects the views of theauthors, and does not necessarily represent the official positionof, or endorsement by, the William Glasser Institute. The accu-racy of material published in the Journal is the responsibility ofthe authors.

Subscriptions: $15.00 for one year or $28.00 for two years. (US.currency) International rates: $23.00 for one year or $40.00 fortwo years. Single copies. $8.00 per issue. International $10.00per issue. Send payment order to the editor. Back issues VoL 1-8, $3.00 per issue. VoL 9-14, $4.00 per issue, VoL 15-19. $5.00per issue. Vol. 20-25, $7.00 per issue. VoL 26-28. $8.00 per issue.

Permissions: Copyright held by the International Journal ofReality Therapy. No part of any article appearing in this issuemay be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever withoutwritten permission of the editor-except in the case of briefquotations embodied in the article or review.

'.;~"";'.~lj.tWte'<Wi9~l6_~::-..; ._? . c; ••.•. "" ~ -\- .' '"' • \' ",::,,"*,~, '"7

2 • International Journal of Reality Therapy • Fall 2009 • Vol.XXIX, number 1

i!i!i

SaleOption OneComplete Set of Vol 1-28 of Journal1981-2009

List Price = $ 260Sale Price = $ 150(International = $ 200)

Option TwoVol 19-28 of Journal 1997-2008

List Price for 20 issues = $ 140Sale Price = $ 90(International = $ 120)

Send order toLarry Litwack

650 Laurel Ave, #402

Highland Park, IL 60035

llltwackesaol.com

International Resource Guide

Vol 1 Hard copy of RG(approx 200 pp) through 1995US & Canada $ 25International $ 35

Vol 2 Hard Copy of RG

(a pprox 60 pp) 1996 to 2007US & Canada $ 10International $ 20

Both Vol 1-2

US & Canada $ 30International $ 50

Send order to above address

Author and Title IndexesVol. 1-5 in Vol. 6-1Vol. 6-10 in Vol. 10-2Vol. 11-15 in Vol. 16-1Vol. 16-20 in Vol. 20-2Vol. 20-25 in Vol. 25-2

Editor's CommentsLarry Litwack

International Journal of Reality Therapy. Fall 2009 • Vol.XXIX, number 1 • 3

i

IiII!II~~~~~il~~~~j;;

ih:

~~~~!rj!4~~~"J::41

?i;~~:,~\l!

~,~~

i~

i;m'-"~~--.

~

;'I'~;, .'!;;i-

II;~i!i~~I,I

T;;his issue marks the start of the 29th year of publication for the Journal. That means that thisr will be the 57th issue of the Journal that I have edited. During that time, I have had the good

fortune to be helped by a great number of people - especially the authors of the hundreds of articlesthat have been published, the members of the editorial and advisory boards, and the support fromNortheastern University and National-Louis University in helping produce and mail the Journal.

I am particularly indebted to several individuals who have facilitated my growth and developmentover the years - starting with Perry Good and Al Katz who were my first RT instructors in the late'70s, this list includes some individuals who were constantly supportive of my efforts. This includesTom Bratter, John Brickell, Naomi Glasser, Adrian Gorman, Diane Gossen, Robert Renna, JoshuaRitchie,Adrian Schoo, Bob Wubbolding, and the leadership of the William Glasser Institute-Australia.

Since 1980, when I became RTC, I have been closely connected with the William Glasser Institute. Istarted the Journal because I felt there needed to be a public forum for the ideas of internal controlpsychology as exemplified by reality therapy and choice theory. I served for three years on the WGrAdvisory Board to more closely ally with the movement. Although we may have disagreed at timesover article or editorial content, I always felt that the Institute was supportive of my efforts.

Perhaps my greatest satisfaction over the years in addition to the Journal has been being the leaderin introducing reality therapy to Israel. Since the late 1990s, I have been going to Israel at least oncea year to conduct training there. Working with Joshua Ritchie, we have been able to develop a cadreof supervisors and trainers who hopefully will continue the training and development in the country.

Now it is time to move on. This will be the last issue under my editorship. I made this decision for avariety of reasons. Perhaps the major reason was that the cost of the Journal has always beendefrayed by individual and library subscriptions, accompanied by orders from WGl-England. WGI-Australia, and the William Glasser Institute in California. Considering the current financial status ofWGI, (at one time membership was in the 14-1500 range) the cost of printing and mailing theJournal to its members has become a burden that WGI no longer feels able to afford. Although stillsupportive of the Journal, the suggestion has been made to develop the Journal as an on-line publi-cation. I felt that such a move would be an excellent time to have the Journal move under newleadership.

I am happy to report that Dr. Thomas Parish has agreed to assume the editorship of the Journal,effective as of the start of 2010. Tom has been a long-time contributor to the Journal, and is wellaware of the challenges that lie ahead. The new mailing address as of January 1st for the Journal willbe 4606 SW Moundview Drive, Topeka, Kansas 66610-1602., tel no. 785-862-1379. I of course will beavailable to help Tom in any way I can to facilitate the transition. Back issues up to and includingthis issue will continue to be available from me. The Resource Guide including material from 1981-2007 will also continue to be available through me. Those of you who may be interested in workingwith Tom as reviewers, members of the editorial board, etc. are encouraged to contact him.

I am reminded of the words of John Silber, former president of Boston University, and one-timecandidate for governor of Massachusetts, who had the misfortune of saying during his gubernatorialcampaign (referring to the elderly) "When you're ripe, its time to go.". My thanks to all of you.

4 • International Journal of Reality Therapy. Fall 2009 • Vol.XXIX, number 1

Using Reality Therapy in Schools: Its Potential Impact on theEffectiveness of the ASCA National Model

Cynthia Palmer Mason and Jill D. Duba

Both authors are on the faculty of {he Department of Counseling and Student Affairs atWestern Kentucky University, Bowling Green. KY

ABSTRACT

The primary purpose of this manuscript is to examinethe application of Reality Therapy in schools. The basiccomponents of the American School CounselingAssociati.on's National Model and also the core tenets ofReality Therapy are reviewed in terms of pertinent litera-ture. Thi.s is followed by a focus on the delivery system ofthe national model. Lastly, specific emphasis will be placedon the potential impact Reality Therapy can have onstudent academic achievement, personal/social develop-ment, and career decision-making skills when applied toeach program component.

In 2003, the American School Counselor Association(ASCA) published the ASCA National Model: AFramework for School Counseling Programs (Wittmer &Clark, 2007). Using the best practices over the last fiftyyears, the national model was developed during a summitin 2001 by the leadership of ASCA, national school coun-seling leaders, school counselor educators, practicingschool counselors, state guidance coordinators. schooldistrict guidance coordinators, and representatives fromthe Education Trust. Much of the work incorporated in theframework was previously done by Drs. Norm Gysbers, C.D. Johnson, Sharon Johnson, and Robert Myrick(Wittmer & Clark, 2007).

This model provides a foundation, a delivery system, amanagement system, and an accountability system forprofessional school counselors (Wittmer & Clark, 2007).The ASCA National Model's framework includes thethree domains of academic achievement. career decision-making, and personal/social development. Perhaps themost significant change for school. counselors in the 21stCentury has been the expectation for them to spend alarger percentage of their time in the classroom usingdevelopmental guidance lessons to support and enhanceacademic achievement. In [act, because of the need forcounselors to impact academic achievement, universitytraining programs have changed from a theory basedpreparation to an education based preparation (House &Martin, 1998).

Effective school counseling programs have structuralcomponents and program components (Wittmer & Clark.2007). The structural components provi.de the ideologicalunderpinnings for the entire program, and should be writ-

ten by an advisory committee composed of administrators,counselors, teachers, parents and community leaders. TheMission Statement and the Rationale Statement are in thiselement. The Mission Statement outlines the purpose ofthe program. This narrative includes a set of principleswhich guides the development, implementation, and eval-uation of the entire program. Following the writing of theMission Statement, the advisory committee develops theRationale Statement. This document clearly presents thereasons for having a comprehensive, developmental coun-seling program in place. It also explains how the programwill benefit the students, the faculty, the parents, and thespecific community being served. The ProgramComponents of the ASCA National Model will bereviewed in the paragraphs that follow.

All activities that counselors perform to deliver theASCA National Model are framed within four programcomponents (guidance curriculum, individual planning,responsive services, and system support). Each componentmakes specific contributions to enhance academicachievement, career decision-making, and personal/socialdevelopment for students (Gysbers & Henderson. 2006).For instance, the Guidance Curriculum complements theacademic curriculum. Its purpose is to provide preventive,proactive lessons to promote positive mental health andenhanced academic achievement for all students.Guidance lessons and activities that focus on relationships,integrity, self-esteem. self-discipline, goal-setting. studyskills, time management, anger management, careers,decision-making, and the importance of acquiring a qual-ity education support and enhance the school instructionprogram.

The Individual Planning component consists of activi-ties that help students to plan, monitor, and manage theirown learning and personal career development. Withinthis element, students explore and evaluate their educa-tion, career options, and personal goals. School counselorswork closely with students on an individual basis andupdate their files after each intervention.

The Responsive Services component provides individ-ual counseling. small group counseling, consultations, andreferrals to meet the immediate needs and concerns ofstudents. This element of the counseling program is avail-able to all students and is often initiated by students.

International Journal oi Reality Therapy· Fall 2009 • Vol.XXIX, number 1 • 5

Services provided in this component help students toresolve personal concerns that could possibly impede theiracademic concentration and achievement if left unat-tended.

The System Support component provides managementactivities that support the total school counseling program.These elements include professional development, staffand community relations, consultations with teachers andparents, program management, advisory council activities,and research and development.

Effective school counseling programs are 100%programs with all counselor activities fitting into one ofthe four program components. Counselors at each levelmust consider the specifics of their particular schoolsetting and decide the percentage of time to devote to eachprogram component (Wittmer & Clark, 2007). The focusof ASCA National Model school counseling programs isclearly on the academic achievement, personal well-being,and equity of opportunity for all students. Now that thebasic components of the ASCA National Model have beenreviewed, the following paragraphs will address the coretenets of Reality Therapy.

Reality Therapy is a method of counseling andpsychotherapy that was developed by William Glasser(1965). Validated by research studies, this theoreticalapproach has been successfully taught and practiced in theUnited States, Canada, Korea, Japan, Singapore, theUnited Kingdom, Norway, Israel, Ireland. Germany,Spain, Slovenia, Croatia, Italy, Colombia, Kuwait, Russia,Australia, New Zealand, and Hong Kong (Wubbolding,2000). In addition to other areas, Reality Therapy hasbeen effectively applied to schools (Glasser, 1990, 1993),parenting (Glasser, 2002), and counseling and therapy(Wubbolding, 2000, 2004; Wubbolding & Brickell, 1999).

Choice Theory is the underlying theoretical basis forReality Therapy. According to Choice Theory, all humanbeings are motivated by five genetically encoded needs -survival, love and belonging, power or achievement, free-dom or independence, and fun - that drive us all our lives(Glasser, 1998). Glasser believes the need to love andbelong is the primary need and also the most difficult needto satisfy because the involvement of another individual isrequired to meet this desire.

Choice Theory emphasizes that beginn.ing shortly afterbirth and continuing all through life, individuals storeinformation inside their minds and build a file of wantscalled the Quality World. The Quality World consists ofpeople, activities, events, beliefs, possessions, and situa-tions that fill personal needs (Wubbolding, 2000). Peopleare the most important component of each Quality Worldand these are the individuals clients care about and wantmost to connect with. For therapy to be successful, a ther-apist must be the kind of person the client would considerputting in his/her quality world (Glasser, 2001). Choice

6 • International Journal of Reality Therapy > Fall 2009 • VoI.XXIX, number 1

theory explains that everything we do is chosen and everybehavior is our best attempt to get what we want to satisfyour needs (Glasser).

A basic goal of Reality Therapy is to help clients learnbetter ways of fulfilling their needs. The procedures thatlead to change are based on two specific assumptions(Glasser, 1992). The first assumption is that their presentbehavior is not getting them what they want; the secondassumption is that humans are motivated to change whenthey believe they can choose other behaviors that will getthem closer to what they want.

Reality Therapy emphasizes the importance of thetherapeutic relationship which is the foundation for effec-tive counseling outcomes (Wubbolding & Brickell, 1999).Counselors are able to develop positive relationships withclients when they possess the personal qualities of warmth,sincerity, congruence, understanding, acceptance, concern,openness, respect for the client and the willingness to bechallenged by others (Corey, 2009). These characteristicsallow school counselors to function as advocates who areable to instill a sense of hope in students. Once the thera-peutic relationship has been established, the counselorassists students in gaining a deeper understanding of theconsequences of their current behavior. At this point,students are helped to understand that they are not at themercy of others, are not victims, and that they have arange of options to choose from.

Reality Therapy provides the delivery system for help-ing individuals take more effective control of their lives.The acronym WDEP is used to describe the basic proce-dures of Reality Therapy. Each letter refers to a cluster ofstrategies that are designed to promote change: We wantsand needs; Dedirection and doing; Eeself-evaluation; andPe-planning (Wubbolding, 2000). The following para-graphs will focus on the delivery system of the ASCAnational model which includes the activities, interactions,and areas in which counselors work to enhance the lives ofboys and girls. Within the delivery system there are fourprogram components: school counseling curriculum, indi-vidual student planning, responsive services, and systemsupport (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006). Specific emphasiswill be placed on the potential impact Reality Therapy canhave on student academic achievement, personal/socialdevelopment, and career decision-making skills whenapplied to each program component.

School Counseling Curriculum

The School Counseling Curriculum program compo-nent is used to impart guidance and counseling content tostudents in a systematic way. Activities in this componentfocus on student's study and test-taking skills, post-second-ary planning, understanding of self and others, peerrelationships, substance abuse education, diversity aware-ness, coping strategies and career planning (ASCA. 2006).Guidance lessons are usually presented to students in

regular classroom settings. School counselors work withthe Steering Committee and the School CommunityAdvisory Committee to decide on the competencies(knowledge and skills) students should acquire at eachgrade level (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006). This curriculumallows counselors to be proactive rather than reactive intheir attempt to meet student needs.

School counselors are actually responsible for thedevelopment and organization of the school counselingcurriculum (Wittmer & Clark, 2007); however, the cooper-ation and support of the faculty, staff, parents andguardians are necessary for its successful implementation.This is one of the reasons why Reality Therapy practition-ers can be most effective in schools. Reality Therapyemphasizes the importance of the personal qualities ofwarmth, sincerity, congruence, understanding, acceptance,concern, openness and respect for each individual thattherapists must possess. These characteristics that pave theway for school counselors to develop positive therapeuticrelationships with students also help them to gain respect,cooperation, and support from parents, guardians andthose who work within the schools.

When deciding on specific lessons and activities for theschool counseling curriculum at each grade level, RealityTherapy practitioners consider the five basic needs that allhumans possess (survival, love and belonging, power orachievement, freedom or independence, and fun). Specialattention is always given to love and belonging whichGlasser (1998) believes is the primary need. These basicneeds make up the Quality World for each individual. Thispersonal world consists of specific images of people, activ-ities, events, beliefs, possessions and situations that fulfillindividual needs (Wubbolding, 2000). People are the mostimportant component of the Quality World. For a success-ful therapeutic outcome, the counselor must be the kind ofperson a client would consider putting in his/her QualityWorld. As Reality Therapy practitioners interact withstudents, their personal characteristics enable them toappeal to one or more of each student's basic needs.

Before focusing on the importance of academicachievement, personal/social development and careerinformation; Reality Therapy practitioners work at involv-ing, encouraging and supporting all students to help themfeel that they are cared for and actually belong to thisspecific group and this particular school. This interactionhelps to build trust. It is through this relationship with thetherapist that clients begin to focus and learn from them.

As guidance lessons are presented from the structuredcurriculum, school counselors at each grade level focus onthe underlying characteristics of reality therapy (Corey,2009). They begin by emphasizing choice and responsibil-ity. Students are taught that they choose all that they doand are responsible for what they choose. Reality thera-pists challenge students to examine and evaluate their ownbehavior. Students are encouraged to consider how effec-

tive their choices are with regard to their personal goalsfor academic achievement, personal/social adjustment andcareer development. After class discussions, students aretaught to make better choices -choices that will help themto meet their needs in more effective ways as they strive todevelop better relationships, increased happiness and asense of inner control of their lives (Wubbolding, 1988).

Individual Student Planning

When this program component is properly imple-mented, P-12 school students will graduate from theirrespective secondary schools with more realistic plans forthe future. This is a service whereby counselors focus ongoal setting, academic planning, career planning, problemsolving and an understanding of self (ASCA, 2006). Eachschool year, counselors at all levels should schedule at leastone individual planning session with each student in theirassigned group. It is important for parents to be invited toattend these sessions as their involvement and support arevital for student motivation. This cycle of counselingbegins with the counselor's efforts to create a positiveworking relationship with each student. The personalcharacteristics of each counselor are assets as he/she worksto develop a meaningful therapeutic relationship witheach counselee. When this relationship is an understand-ing and supportive one, it provides a foundation foreffective outcomes. Client involvement is important.Reality therapy practitioners use attending behaviors,listening skills, suspension of client judgment, facilitativeself-disclosure, summarizing and focusing to create thetype of climate that leads to client participation. Once theinvolvement has been established, counselors focus on thespecific procedures that lead to change in behavior.

The cycle of counseling proceeds with the employmentof the WDEP system. Students are encouraged to exploretheir wants. needs and perceptions in the areas ofacademic achievement. personal/social adjustment andcareer development. This is followed by an exploration oftheir total behavior in each of these areas and theirpersonal evaluations of how effective they are in movingtoward what they actually want. Students are asked if theirpresent behavior has a reasonable chance of getting themwhat they want now, and if they believe it is taking them inthe direction they want to go (Wubbolding, 20(0).

Standardized test scores, semester grades, andpersonal preferences are considered as student goals arereviewed. According to Glasser (1992), individuals aremotivated to change when they are convinced that theirpresent behavior is not getting them what they want andalso when they believe they can choose other behaviorsthat will get them closer to what they want. When studentsdecide to change, this is their choice. When they deter-mine what they want to change, Reality Therapypractitioners are able to help them formulate structuredplans for change. Wubbolding (2000) uses the acronymSAMIC to capture the essence of an effective plan: simple,

International Journal of Reality Therapy. Fall 2009 • VoI.XXIX, number 1 • 7

attainable, measureable, immediate. committed to andcontrolled by the planner.

Individual student planning sessions usually end with asummary of what has been agreed upon during the inter-view. Two copies are made of student plans when they arerevised; one copy is placed in the student's folder and theother copy is given to the student. Unless a definite datehas been scheduled for the next meeting, counselees areencouraged to consult with counselors as needed duringthe remainder of the school year.

Responsive Services

School counselors are called to respond to the immedi-ate needs and concerns of their students. Such responsesmay include the provision of information. peer mediation.referrals, counseling, or consultation. Further, the ASCANational Model provides specific criteria or objectives ofResponsive Services. Such objectives can be met throughthe use of basic Choice Theory concepts.

Prevention Education to Address Life Choices

The first criterion of Responsive Services states,"Every student K-12 receives prevention education toaddress life choices 10 academic, career, andpersonal/social development" (ASCA, 2003, p. 114). Howcan a school counselor provide prevention educationthrough a Choice Theory lens? Dr. Glasser writes,"Education is not acquiring knowledge; it is best definedas using knowledge" (1998, p. 238). Further, the value liesin applying what has been learned, rather than collecting amental cabinet of knowledge and data. So perhaps theinitial step is re-thinking about what is important to teach.From a Choice Theory perspective, there are two essentialelements or questions. First, how can school counselorsprovide opportunities for students to address life choices invarious areas in real time? Second, how will the counselorprovide good experiences for students as they learn how toaddress life choices?

The opporturuties are endless depending on howcreative one is. However, for the purpose of brevity, ideasfor Choice Theory based opportunities are outlined belowspecifically as they relate to a school counselor's call toprovide responsive services to all students in the areas ofacademic achievement, career development, andpersonal/social adjustment. In addition, these opportuni-ties are meant to set the context for enjoyable experiencesfor all involved, teachers and students alike.

Academic development. The opportunities suggestedare based upon the assumption that if one of the five basicneeds is not being satisfied, misery will follow (Glasser,1998). In a school system, misery is typically related toacademic difficulties, a lack of interest and motivation, andfailure. Consequently, school counselors are urged toconsider the uniqueness of each student, while providingopportunities that serve to meet all five of the Basic Needs.

8 • International Journal of Reality Therapy' Fall 2009 • Vol.XXIX, number 1

a. Survival and Health (physiological needs). Mentaland emotional stressors are directly linked to organicresponses within the body.

i. Teach students stress and relaxation coping mecha-nisms as a part of the health education curriculum

ii. Lead students through brief relaxation techniquesprior to all examinations

iii. Teach appropriate thought reframing and cognitiverestructuring, and its relation to pulse rate and thebody's stress response

b. Love and Belonging

i. Hold multiple small and large group parties, cele-brations, and groups in order to solidifyrelationships; goal of groups can be learning the 14habits (See Rapport, 2007)

ii. Use basic counseling skills so that they are betterable to relate to students on an intimate andfriendly level

iii. Teach students basic counseling skills so they arebetter able to relate to others

iv. Develop partnerships among students (account-ability, studying)

c. Self- Worth/Power

i. Set up activities so that all students can achieve.Encourage the use of open book tests

ii. Provide t1exible learning activities so that allstudents can be empowered

iii. Encourage leadership positions among all students(see Fox & Delgado, 2008, Secret Agents' Club).Students who appear introverted and withdrawnshould be sought to serve in such positions.

d. Freedom

i. Teach the students the WDEP system. Help themuse it.

ii. Curriculum, Reading: Students can select from alist of books as required reading

iii. Curriculum, Math: Set up role-play scenarios thatwould encourage students to use math abilities(i.e., paying at a restaurant, figuring the tip for anygiven service, developing a budget based on careerchoice)

e. Fun: All of the exercises above could includeelements of fun depending on the attitudes of allparticipating.

Career development. All students should he tutoredand encouraged to complete the Choice Theory CareerRating Scale, Figure I (based off of Glasser's Choice

"~

\li-II.,Wl;t~~~

IIt

Theory Needs Rating Scale). Group discussions and indi-vidual sessions should be available for students to talkabout how their career choices meet their Basic Needs.Another option is holding an annual career fair.Employees from the community can serve as representa-tives of any given career. While there are plenty ofopportunities for students to learn from these representa-tions, students also are put in a place where they canpractice relationship skills as they inquire about theircareers of interest.

After such a fair, students can be encouraged to chooseone particular career. The following outline serves as amethod of encouraging awareness about how one's careerchoice will impact flexibility in choices and options on aday to day schedule.

1. Students are asked to review career choice in termsof potential salary, schedule, and training.

2. Various cases will be distributed related to potentialcircumstances that could arise in adulthood such as aneed for a new car, personal or family illness,marriage, family obligations, etc. Students will needto consider how their chosen line of work and jobeither poses challenges when such personal issuesarise or allows for flexibility.

3. Students take the Choice Theory Career RatingScale for Children and Adolescents to evaluate ifsuch a career choice fits their needs.

This is only one example of how creativity can beapplied within a Choice Theory framework. Counselorsand teachers are encouraged to consider others.

Personal/Social Development. The authors suggest theuse of the Choice Theory Needs Raring Scale. School coun-selors can use this as a back-drop for discussing personaland social matters. For example, if a student is strugglingwith making friends, one would investigate where thestudent's need strength falls within the Love andBelonging scale. Next, the student would be asked to ratehis or her present need satisfaction within this scale.(Given the presenting problem, we could assume thatone's need satisfaction rating is going to be less than therating given for the need strength on this given scale.) Thecounselor could inquire about what steps would be impor-tant and essential in moving the client's need satisfactionrating up closer to the need strength rating. For example,let's say the student's need strength rating for Love andBelonging was a 10, however the student's need satisfac-tion rating on the same scale was a 4. The counselor mightrespond, "No wonder you are not feeling so good aboutmaking friends. You really want to have more friends;however, that is not working out so well [or you. You arenot very satisfied with the situation right now. Let's saythat next week, instead of being satisfied at a number 4,you moved up to a 5. So you were a bit more satisfied.What would you have done that week in order to feel

more satisfied with making friends and being a friend?"This is one way in which the Choice Theory Needs RatingScale can provide a context for conversation with studentsabout their desired personal and social development, aswell as what they are currently doing to meet related goals.

System Support

School counselors are called to manage activitieswithin the school that serve to establish, enhance, andmaintain the total counseling program. This involvescollaborating with colleagues. as well as providing profes-sional development opportunities to staff. From a ChoiceTheory perspective, the heart of successful collaborationincludes good. healthy, and effective relationships amongthose collaborating. Healthy relationships are possiblebecause there are healthy and happy people in them.

Glasser (1998) asserts that there are particular charac-teristics of people who can maintain healthy relationships.First. people in such relationships are healthy and happyindividuals. That is, they understand that the only behav-ior they can control is their own (so they are not usingwhat Glasser refers to as External Control Psychology).They do not experience misery because they are notinvolved in blaming others for their feelings or in the busi-ness of trying to control or manipulate others to think oract in certain ways (Glasser, 1998, p. 19). Further, they takeresponsibility for their feelings. Healthy people do notblame others when they are feeling upset, dismissed, ormisunderstood. More specifically, positive behaviors areused that include choosing to care, support, listen, negoti-ate, befriend, love, encourage. trust, accept, esteem, andwelcome while refraining from destructive ones such aschoosing to coerce, compel, force, reward, punish, boss,manipulate. criticize, motivate. blame, complain, badger,nag, rate, rank or withdraw (Glasser, 1998, p. 21). In orderto maintain and encourage such healthy relationships.school counselors might consider conducting a brief pres-entation to staff related to the harms of External ControlPsychology in relationships, as well as what behaviorscontribute to healthy collegial relationships.

In addition to upholding the above mentioned healthybehaviors, school counselors who are required to establishand maintain system support within the school are encour-aged to do so within a Lead Management framework. Byfollowing the four essential principles of LeadManagement, school counselors can provide an enjoyablesystem of collaboration that only serves to enhance rela-tionships among everyone in the school system.

I. The school counselor engages all colleagues in anongoing honest discussion of both the cost of thework and the quality that is needed for the systemsupport to be successful. In other words, all stake-holders (members of the system support team) areinvited to contribute their ideas without pressure toconform. All members of the team are educated on

international lournal of Reality Therapy' Fall 2009 • Vol.XXIX, number 1 • 9

the elements of healthy relationships and the abovementioned positive. as welt as destructive behaviors.

2. The school counselor models the job so that allstakeholders can see what she/he expects. One wayof assuring this is by involving oneself in an intro-spective process. For example, this might includeasking oneself the following questions: (a) is mycounseling with students based within a ChoiceTheory framework; (b) are my one-on-one relation-ships with colleagues consistent with what I amexpecting within this system: (c) am 1 open to feed-back about how I am leading the group. as well asfeedback regarding the struggles of the stakeholders.

3. The school counselor does not micro-manage butbelieves that all stakeholders are responsible forevaluating how they are contributing to the systemsupport. Stakeholders feel welcome to voice theirconcerns and struggles to the school counselor.

4. The school counselor accepts every opportunity toteach that the quality of the school system support isbased on continual improvement. That is, the roadtowards quality is a journey rather than a destina-tion. Consequently, the school counselor remainsfocused and hopeful at all times.

Please see Glasser, 1998, chapter 11 for an exhaustedexplanation of this concept.

DISCUSSION

The United States spends more money on educationthan other major countries, but failed in 2000 to rankamong the top ten countries for student performance inmathematics, science, and reading (Feller, 2(03). Also,current trends in youth related issues include increaseddishonesty; a growing disrespect for parents, teachers, andother authority figures; increased cruelty; a rise in preju-dice and hate crimes; a decline in the work ethic; increasedself-destructive behaviors which involve premature sexualactivity, substance abuse, and suicidal tendencies; and adecline in the perception of importance of personal andcivic responsibility (Wittmer & Clark, 20(7). These dataare indicative of a need for a transformed perspective.

The ASCA National Model: A Framework for SchoolCounseling Programs was developed by state and nationalschool counseling leaders. It includes the three domains ofacademic achievement, career decision-making, andpersonal/social development. All activities that counselorsperform to deliver the ASCA National Model are framedwithin four program components (guidance curriculum,individual student planning, responsive services, andsystem support), This model is both comprehensive anddevelopmental.

The school counseling program is important and so arethe counselors who will implement it. We believe that

10 • International Journal oi Reality Therapy > Fall 2009 • VoI.XXIX, number 1

Reality Therapy practitioners have the potential to impactstudent academic achievement, career decision-making,and personal/social development most effectively for twospecific reasons. First, Reality Therapy training empha-sizes the importance of the personal qualities of warmth,sincerity, congruence. understanding, acceptance, concern,openness, and respect for the individual. These character-istics help school counselors to build trust and developpositive therapeutic relationships with students. This isvital. Second. Reality Therapy practitioners understandand are able to teach students the basic principles ofChoice Theory, Basic Needs, and the Quality World. Thisknowledge will provide an added sense of self-esteem.self-worth, inner peace. and self confidence.

We have outlined a number of activities RealityTherapy practitioners could use in all four programcomponents to enhance academic achievement, careerdecision-making, and personal/social development. Also,we developed a Choice Theory Career Rating Scale forChildren and Adolescents. Counselors can use this scale asa guide for discussing career interest as well as personaland social matters.

Effective school counselors and school counseling:programs are vital to our society. We recommend thatschool districts purchase copies of The Quality School(Glasser, 1990) and The Quality School Teacher (1993) forall administrators and members or the faculty. We alsorecommend that school districts incorporate RealityTherapy training as a part of the required professionaldevelopment for all school personnel. These efforts couldmove school counseling from the periphery of schoolprograms to a position of leadership in all areas thatimpact student growth and development (EducationTrust, 20(3).

REFERENCESAmerican School Counselor Association. (2003). The

ASCA National Model: A framework for schoolcounseling programs. Alexandria. VA: Author.

American School Counselor Association. (2000). Rolestatement: The school counselor. Alexandria, VA:Author.

Corey. G. (2009). Theory and practice of counseling andpsvchotherap y. Belmont. CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Education Trust. (2003). Transforming school counseling.Retrieved August 13, 2006 fromhttp://www2.edtrust.org/EdTrust/Transforming+Scho01-iCounseling/Metlife. htrn

Feller, B. (2003. September Hi). U. S. outspends, doesn'toutrank in education. The Daily News, pp. AI. A6.

Glasser, W. (1965). Reality therapy. New York: HarperCollins.

Glasser, W. (1990). The quality school. New York: HarperCollins.

Glasser, W. (1992). Reality therapy. New York StateJournaljor Counseling and Development, 7 (1). 5-U.

Glasser. W. (1993). The quality school teacher. New York:Harper Collins.

Glasser. W. (1998). Choice theory. New York: HarperCollins.

Glasser, W. (2001). Counseling with choice theory. NewYork: Harper Collins.

Glasser. W. (2002). Unhappy teenagers. New York:Harper Collins.

Gysbers, N., & Henderson. P. (2006). Developing &managing your school guidance and counselingprogram. Alexandria, VA: American CounselingAssociation.

House, R. M., & Martin. P. J. (1998). Advocating forbetter futures for all students: A new vision schoolcounselor. Education. l19, 2~4-29 l.

Wittmer, J .. & Clark, M. A. (2007). Monaging y01/1' schoolcounseling program: K -12 developmental strategies.Minneapolis, MN: Educational Media Corporation.

Wubbolding. R. (1988). Using reality therapy. New York:Harper & Row.

Wubbolding. R. (2000). Reality therapy for the 21stcentury. Philadelphia, PA: Brunner- Routledge.

Wubbolding, R. (2004). Reality therapy training manual.Cincinnati. OH: Center for Reality Therapy.

Wubbolding, R., & Brickell. J. (1999). Counselling withreality therapy- Oxfordshire. UK: Spcechmark,

The first author may be contactedat cynthia.masontz'wku.edu

International Journal of Reality Therapy> Fall 2009 • VoI.XXIX, number 1 • 11

-~-------------- ..-- .. ---

Needs and their Definitions STRENGTH AND SATISFACTIONR4T1NG SCALE

Love and Belonging: Need Strength

The need for interpersonal contact, workingtogether with others, and the potential for 0 I 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10developing long term relationships and friendships.

Need SatisfactionTo feel wanted and approved of by classmates, aswell as by authorities.

0 I 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ]0

Self Worth/Power: Need Strength

The need for a sense of empowerment,competence, and opportunities for personal 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10effectiveness in the school environment. Aconnection between one's personal sense of Need Satisfaction

achievement and worthiness with similarexperiences in the home, school, and community. 0 I 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10Opportunities for leadership and managementroles.

Freedom: Need Strength

The need for autonomy, independence, and limitedrestrictions in the school environment and in the 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10home. Opportunities for spontaneity and change in

Need Satisfactionall areas of one's life.

0 I 2...,

4 5 6 7 8 9 10-'Fun and Enjoyment: Need Strength

The need for balance between work and pleasure.Sufficient opportunities for enjoyable and fun 0 I 2

...,4 5 6 7 8 9 10-'

experiences within the context of school, home,Need Satisfactionand community.

0 1 2...,

4 5 6 7 8 9 10.)

Survival & Health: Need Strength

Safe physical environment at home and school. Anenvironment that is a supportive context for one's 0 I 2

...,4 5 6 7 8 9 ]0.)

mental and emotional health. Family income thatNeed Satisfactionadequately provides for enhanced educational

opportunities, personal sel f-care, leisure activities,and vacations. 0 1 2 ..., 4 5 6 7 8 9 10.)

12 • International Journal of Reality Therapy' Fall 2009 • Vol.XXIX, number 1

The Basic Needs Cenogram:A Tool to Help Inter-Religious Couples Negotiate

Jill D. Duba

The author is an associate professor in the Department of Counseling and Stu dent Affairs atWestern Kentucky University in Bowling Green, Kentucky

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this article is two-fold. First, a briefreview of the unique characteristics of inter-religiouscouples, as well as the common negotiations made in suchrelationships will be provided. Second, salient counselingimplications will be presented, with the introduction of theBasic Needs Genogram as a possible technique in workingwith inter-religious couples. A case conceptualization anddiscussion will follow.

Consider the following example. Jane has a high needfor power. She satisfies this need by serving on variouschurch committees throughout the year. When she isunable to attend those committees, or feels guilty abouthow much time she is dedicating, she may experiencedissonance between her need for power and her inabilityto serve or her choice to feel guilty (respectively). Jane ismarried to Joe. Joe's need for power, on the other hand isquite low. However, his need for love and belonging is veryhigh (higher than Jane's). Joe is a Humanist and does notpractice in an organized religion. Although he can appre-ciate Jane's dedication to church; he has begun tocomplain to her about all of the time she spends on Sundayat church. He feels "threatened" and "deserted." Sheresponds by feeling guilty and becoming angry at Joe.They both agree they need counseling.

The above example involves more intricacies than itappears to present. Consequently, Professional Counselorsare behooved to consider the complexities involved inworking with inter-religious couples. First, a general under-standing of the challenges couples face, and thenegotiations needed to maintain a successful relationship isrequired. Second, counselors should be willing to educatethemselves about various religious backgrounds wheneverthey are working with someone whose life is informed byhis or her faith (Dub a, 2008). In addition, counselorsshould be aware of appropriate techniques that are suitablefor the religious related challenge or conflict.

The purpose of this article is two-fold. First, a briefreview of the unique characteristics of inter-religiouscouples, as well as the common negotiations made in suchrelationships will be provided. Second, salient counselingimplications will be presented, with the introduction of theBasic Needs Genograrn as a possible technique in workingwith inter-religious couples. A case conceptualization anddiscussion will follow.

Inter-religious Couples

The frequency of inter-religious marriages is on therise. For example, a survey conducted in 2001 suggestedthat one partner in every 23% of Catholic marriages, 33%of Protestant marriages, 27% of Jewish marriages, and21 % of Muslim marriages does not identify with thatparticular religious faith (Kosmin, Mayer & Keysar, 20(1).Although the number of inter-religious marriages in theUnited States is a minority compared to religious homog-enous relationships, Professional Counselors arebehooved to understand the complexities of such couples.

Many studies suggest that inter-religious couples tendto experience less marital satisfaction than their counter-parts (Lehrer, 1999; Parsons, Nalbone, Killmer, &Wetchler, 2007). If one is aware of the factors found to beassociated with marital satisfaction, this becomes clearer.Consider the following: communication, moral values,faith in God, forgiveness, equity, togetherness, intimacy,love, sexual intimacy and commitment (Bryant, Conger, &Meehan, 2001; Fincham & Beach, 2002; Frame, 2004;Weigel & Ballard-Reisch, 1999). Religious tenets and faithperspectives can provide benchmarks or standards, if youwill, for many of the above mentioned factors.

The sexual dimension of a religious couple's relationshipoften is informed by their faith. For example, guidelines forsexual intimacy are clearly defined by the Catholic Church.That is, every act of marital intercourse should be one thatis open to new life. Further, it is a context for both partnersto become one loving organism where each is giving oneselffreely to the other (Duba Onedera, 20(8). However, thismatter becomes complex if a Catholic is married to aProtestant. Both Liberal and Conservative Protestants tendto believe that there is not a biblical condemnation ofcontraception (Zink, 2008). How an inter-religious couplecommunicates and negotiates their sexual relationship willfactor into their overall marital satisfaction.

The degree of perceived equity may differ in coupleswho share varying religious viewpoints. For example,Islamic teachings give direction for role equity. Partnersmay be perceived as "equals" in the marital relationship,however their role expectations within the marital, as wellas family unit differ (Altareb, 2001'1).When an individual isinformed by his or her religious traditions and guidelines,and is unwilling or unable to negotiate with his or her

International Journal of Reality Therapy. Fall 1009 • VoI.XXIX, number "I • 13

partner's different set of religious tenets, it is no wonderwhy the marital satisfaction dwindles.

Religious beliefs also inform persons about how toresolve moral decisions. Sharing similar beliefs unitescouples and can make for an ease in decision making thatinter-religious couples may not benefit from. For example.the typical view of abortion from a Liberal ProtestantChristian standpoint is that the individual's right to makea responsible, prayerful decision regarding the termina-tion of pregnancy should be honored. Conseq uently,decisions made between two Liberal Protestant Christianpartners versus one Liberal Protestant Christian partnerand a Buddhist partner would be quite different, with thelatter's decision making process being much more compli-cated. The complexities of decision making betweenpartners being informed by two different religiousperspectives can be challenging, tiresome, and may lead toresentment.

Religious persons also tend to participate in religiousrelated activities. This can become exigent for inter-reli-gious couples, however. Consider the challenges ofnegotiating the celebration and attendance of differentreligious holiday functions together (i.e., Christmas,Hanukah). How will Jewish and Christian partners negoti-ate what religious symbols are displayed in the house inDecember? How will the Christian partner respect andhonor the meaning his/her Jewish partner ascribes toHanukah, especially in a society where this holiday is heldsecond to Christmas? How will a Christian partner par-ticipate in Hanukah related activities without feeling thathis/her Christian identity is being threatened; how doesthis impact the relationship'?

There is not enough space to address the multiplecomplexities that inter-religious couples may encounter.What appears to be significant however is the degree towhich partners align with the tenets of their religion andtheir ability to negotiate and show respect for each other'sbeliefs. Lehrer and Chiswick (1993) suggested that it is notwhether or not partners are of the same religion or denom-ination, but rather how compatible they were uponmarrying. This compatibility "dominates any adverseeffects of differences in the religious background" (p. 400).This suggests that during the counseling process, it may behelpful to inquire about how couples came to such agree-ments or negotiations upon marrying.

The Counseling Process: The Essential Elements

Basic Treatment Goals

The goal of treatment when working with inter-reli-gious couples may best be focused on helping coupleslearn how to work and talk through the particular prob-lem, rather than solving it. Religious differences are likelyto be "perpetual;" that is, issues that may never be solvedper say. Gottman (1998) underscores the importance offinding ways to talk about these "perpetual problems."

14 • International Journal of Reality Therapy' Felli 2009 • Vol.XXIX. number 1

More specifically, coming to an understanding of themeaning each person ascribes to his/her position is whatcounts. Consequently, the treatment goals should movecouples to a place where they can enter and maintain aconversation about the differences impacted by their vary-ing religious perspectives, rather than trying to conform tothe other's position.

When communicating about differences or perpetualproblems, it is important that couples maintain particularstances. Such stances include a state of curiosity, interest,openness and flexibility (Biever, Bobele, & North, 1998).Further. partners must be willing to negotiate while beingable to mentally reorganize theit religious experiences andbeliefs in a manner that allows space for another perspec-tive (Lara & Duba Onedera, 2008; Waldman, 2(05).Couples should be asked to verbally agree to the abovementioned stances both inside and outside of the counsel-ing context. The Professional Counselor also shouldinform the couple that when she/he perceives that oneindividual is breaking the agreement, an intervention willbe made. Such an intervention might include a gentleencourager, or asking the partner to reestablish him- orherself by taking a deep breath or re-visiting the overallcounseling goals.

The Basic Needs Genogram: A Tool for ExploringMeaning behind the Religious Conflict

Generally speaking, genograms provide a springboardfor conversation about one's family history and experi-ences. Through the use of this technique, clients, as well astheir counselors can begin to identify patterns of behav-iors, values, and attitudes across generations (Duba.Graham, Britzrnan. & Minatrea, 2009, p. 16). Such aware-ness often promotes behavioral changes and behavioralshifts on the part of clients. When using a Basic NeedsGenogram, clients become further acquainted with howtheir family history has impacted how their own basicneeds are and have been met. Further, the Basic NeedsGenogram is a tool that can motivate persons to considerabout how their "picture albums" have been formed andmaintained throughout generational lines. These "picturealbums" hold images of bow one wishes to satisfy the fivebasic needs: love and belonging, power, freedom, fun andenjoyment, and survival. Individuals are most "healthy" ifyou will, when their basic needs are being met (Duba etal.. 20(9). Further. choices (behaving, thinking, feeling,and physiologicing) are made to meet tbese needs.

Inter-religious Couples

Wubbolding (1988) suggests that marital discord isdirectly related to an incongruence or lack of commonal-ity between and among the wants or "picture albums" ofeach partner. Further, this discord is maintained by eitheror both of two conditions. First, one partner wants theother partner to complement his or her own pictures.Second, this individual (the one wanting the harmony) is

unwilling to change this want. This is clearly noted in thecase of Jane and Joe mentioned at the beginning of thisarticle.

The use of a Basic Needs Genagram in a religiouscontext can serve two objectives. First, this technique canbring about greater awareness about the strength of anygiven basic need, specifically in the context of familypatterns and expectations. Second, the Genogram shedslight on how religion informs individuals within the familyabout how to meet those basic needs. That is, the relevantquestion being, what religious hints or clues are containedin the family "picture albums?"

Comparing and contrasting each partner's Basic NeedsGenogram can lead to change in the marital relationship.An encouraging counselor can challenge each partner tochallenge and modify his or her own "picture albums" inways that bring greater accord to the overall relationship(Duba et al., 2009). This can be done by restructuring howthe Basic Needs are satisfied by considering the following:(a) how one's personal religious beliefs and values (versusthe consideration of only those expected within a familycontext) impact how the basic needs are met, (b) thecongruence between family expectations and one'spersonal incorporation of religion into his or her life: and(c) how the basic needs are currently helping him or herget what is wanted in the marriage. Finally, partners maydevelop new "pictures" based on their increased insight orupon developing similar activities or ways of getting theirindividual needs met.

In summary, individuals are moved to consider newprocesses or new pictures that continue to have individualand personal meaning within a religious context. Howeverclients also are encouraged to examine how they may haveunconsciously "adopted" meaning or patterns from thefamily system which are neither helpful nor supportive ofthe current relationship. For the remainder of this article.an inter-religious couple (without any identifying informa-tion being used) will be presented to illustrate how theBasic Needs Genogram can be used as a tool to break thedissonance between both partners.

Case Example

Evan and Annie were married four years ago in a largeCatholic wedding. Annie grew up in a very tight knitCatholic family. In fact, even during her marriage, sheattended weekend mass with her parents. Christian holydays and holidays such as Good Friday, Easter, andChristmas were spent with extended family members.Further, big celebrations were held in honor of thosemembers receiving the sacraments of baptism, commun-ion, and marriage. It was normal to have at least 300attendees at any given wedding. Not only was the familyconnected through such religious traditions, but Annieremarked that there is this "invisible undertone that Godholds us all together; crosses and other symbols are usually

! -,,,,",

in every room of everyone's home. You just know you areall in it together, one big Catholic family that will staytogether no matter what." Evan, on the other hand, didnot grow up with his faith as intertwined into his familylike at Annie's. He called himself a "Reform Jew" andbelieved that although his faith was "rock solid", hebelieved that peace between different groups was muchmore important than discussing differences and advocat-ing for his position. Evan appreciated how close Annie'sfamily was and wished he came from such a tight family.

Evan and Annie had a very large Catholicwedding which included a Catholic mass, and severalJewish wedding traditions. After the conclusion of themass, Annie and Evan expressed their marital commit-ment under a chuppah. The entire ceremony wascompleted with the Jewish wedding tradition of breakingthe glass. Both partners believed that their wedding was anincredible way of symbolically bridging their differentfaith perspectives.

Presenting Problem

Annie was feeling "disengaged from Evan" and waswondering if they made a "serious mistake in gettingmarried." Annie reported that she resented the fact thatEvan would never be able to participate in the mass withher; and that she and him would have to raise their futurechildren in both faith traditions. She also had a difficulttime understanding why Evan would not even considerlearning more about her faith, especially when he did notseem as committed to Judaism as she was to Catholicism.When asked what her thoughts were about this prior togetting married, Annie remarked that she "was immatureand never really thought about it." Evan, on the otherhand felt betrayed, and was beginning to experienceresentment towards Annie for focusing on this four yearsinto the marriage. Further, he was angry as he felt she wasimplying that his faith and beliefs were "not as importantas hers", and although he did not practice Judaism consis-tently throughout his childhood, it was still an "essentialpart" of who he was.

Case Conceptualization

The first goal of using a Basic Needs Genogram withEvan and Annie was to explore the need strengths of vary-ing family members, as well as how religion affected howmembers satisfy those needs. We explored this more indepth by considering how their religious perspectives,again within a family context .informed them about how tomeet those needs. The arduous process was bringing aboutchange in the marital relationship. Each partner wasresponsible for considering the restructuring of how his orher needs were being met (based within a more personalreligious framework) and whether or not they could usetheir faith to construct new ways' ofnteeting these needs(namely, the changing or altering of their picture albums).

International Journal of Reality Therapy. Fall 2009 • Vol.XXIX, number 1 • 15

~

II11t!1~

!~j~

!!j!~

'I!~1i

I~I{;~:j~.

"~}

\

------------------_ ... ---------

The religious and family influences on basic needstrengths. A review of Annie's need strengths illustratedstrong comparisons to most of her close family members.For example, love and belonging was a high need foreveryone in her immediate family. Upon exploring herextended family, strong family ties were noted and seemedto extend directly from her maternal grandmother, whowas a strong Catholic, and very much loved by everymember of the family. In addition, all members of herimmediate family, as well as those within her mother'simmediate family were practicing Catholics. Annie's needstrength for Power and Achievement also was very high. Avery strong emphasis on education, career excellence andfinancial security was present in her family of origin.Annie considered this further and explained that from areligious perspective, she was taught that with prayer anddependence on God, she could do anything. Her familyvalues and personal views helped satisfy her need forPower and Achievement. She trusted that. In a sense, shealso believed that God wanted certain things for her. "Hewants me to be happy." However, she also noted that thisdrive for power and inner control came at a cost to someof her family members (e.g., having to live far from familydue to job, divorce, marriage later in life). Annie reportedthat despite these negative consequences, everyone in herfamily managed to work through the challenges and arefor the most part, content with their lives. Finally, Fun andEnjoyment also were high on her basic needs. Anniereported that her family was for the most part, a verygenerous, happy and loving group. Everyone tried at leastto model good, Catholic values and they had fun doing it!She wanted to continue this.

Evan's Basic Needs Genogram also was revealing.First, he had high need strengths for both Power andAchievement, and Freedom. This was illustrated acrossthe family as well. All members of Evan's family weresuccessful in their careers. However, Evan noted that mostof his family members (including extended) were nothappy, or at least not as happy as he had witnessed Annie'sfamily members to be. He summed this up by saying, "Welearned that you just succeeded. That's it. Happiness is notsomething you need. Just do your work. Help your neigh-bor and, in the mean time, mind your own business." Herealized that because of this attitude, it was sometimesdifficult for him to understand why Annie was so "bent onbeing happy all of the time." Freedom was valued by thefamily as well. Evan believed that being a Reformed Jewallowed for religious freedom, as well as personal free-dom. Evan was encouraged to consider that there wereother ways of meeting his need for Power andAchievement than what he was accustomed to.

Personal restructuring and marital modification. Therestructuring of meeting one's basic needs did not occurwithin one counseling session. It was a process. somethingthat took trial and error in terms of trying new "personal-

16 • International Journal of Reality Therapy. Fall 2009 • VoI.XXIX, number 1

ities" on as Annie put it. Annie and Evan played with thedetails from their Basic Needs Genograms. Annie realizedthat to a great degree her basic needs were very similar tothose of her family. This was okay: however a part of theformation of her needs was very much related to her desireto meet the (nonverbal) expectations of her family. That is,her irritation towards Evan for not participating incompleting the rituals of the mass may be related to whatshe thought others thought of her. What would the otherpeople at church think about her? What did her familyreally think of Evan being Jewish? What did this say abouther Catholic identity? Such questions were based moreout of fear than fact, however Annie realized that some ofthe ways in which she met her basic needs were formedbased on what she thought was expected from her family.

Evan realized that he never really thought about themeaning of happiness (Fun and Enjoyment) in his ownlife. This was not a value within his family system: howeverfrom witnessing Annie's family, he realized how importantthis was to him. After being a part of the discussion aboutAnnie's need for belonging and love, he commented onhow this was "difficult to understand".

Annie was willing to modify a couple of the ways inwhich she satisfied her needs. For example, she decidedthat she was choosing to ask herself several harmful ques-tions as she pursued her need to belong to her family, aswell as within the Church. So she practiced thought-stop-ping, and asked Evan if he would be willing to volunteerwith her on a church committee. Evan was happy to do so.In addition, Annie realized that her need for Power (andcontrol) could be getting in the way of being happilymarried to Evan. She realized that she may never have herlife in perfect order. She also mentioned that perhaps itwas a good time to take a deeper look at her own self-worth and how she allows externals to determine herworth (e.g., how others see her as a wife). She welcomed areferral to an individual counselor.

Evan decided that he wanted to be happier; that wasimportant to him. He decided that volunteering withAnnie would be a start. He also came to a greater under-standing of why it was important for him to share in theactivities of the church and mass with Annie. Although hewas not ready to change his belief system, he was willing toshake hands with other parishioners during the Sign ofPeace during mass for example. Evan also agreed to readmore about Catholic traditions so that he could at leastconverse with Annie about them.

The couple was seen for a total of eight sessions. Muchof the progress was dependent on each partner's willing-ness to self-reflect, become vulnerable, and negotiate. Thecounselor's main task was to remain patient with eachpartner's process. as well as gently move them to considerother ways of thinking while remaining respectful of therole of religion in eacb individual's life.

III

------------------

CONCLUSION

Working with inter-religious couples takes time andpatience. There are various ways in which to work withcouples facing struggles associated with the differences intheir faith perspectives. Use of the Basic Needs Genogramwith a religious focus is just one way in which couples canexperience greater awareness of their own basic needs inthe context of the family system in a religious context.Such awareness is the foundation for negotiation andbehavioral change in order to negotiate through religiousbased differences.

REFERENCESAltareb, B. (2008). The practice of marriage and family

counseling and Islam. In 1. D. Duba Onedera (Ed.),The role of religion and marriage and family counsel-ing (pp. 89-104). New York: Taylor and Francis.

Biever, J. L, Bobele, M., & North, M. (1998). Therapywith intercultural couples: A postmodern approach.Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 11(2), 181-188.

Bryant, C. M., Conger, R. D., & Meehan, J. M. (2001).The influence of in-laws on change in marital success.Journal of Marriage and Family, 63,614-626.

Duba, J. D., Graham, M., Britzrnan, M., & Minatrea, N.(2009, Spring). Introducing the "basic needsgenogram" in reality therapy-based marriage andfamily counseling. International Journal of RealityTherapy, (28)2, 15-19.

Duba Onedera, 1. D. (2008). The practice of marriageand family counseling and Catholicism. In 1. D. DubaOnedera (Ed.), The role of religion and marriage andfamily counseling. New York, NY: Taylor andFrancis.

Fincham, F. D" & Beach, S. R. H. (2002). Forgiveness inmarriage: Implications for psychological aggressionand constructive communication. PersonalRelationships, 9, 239-25 I.

Frame, M. W. (2004). The challenges of interculturalmarriage: Strategies for pastoral care. PastoralPsychology, 52(3),219-232.

Gottman, J. (1998). The marriage clinic: A scientificallybased marital therapy. New York: Norton &Company.

Kosrnin, B. A., Mayer. E.. & Keysar, A. (2001). Americanreligious identification survey. New York: GraduateCenter of the City University of New York.

Lara, T.. & Duba Onedera, J. D. (2008). Inter-religionmarriages. In J. D. Duba Onedera (Ed.) The role ofreligion and marriage and [amity counseling. NewYork, NY: Taylor and Francis.

Lehrer, E. L., & Chiswick, C. U. (1993). Religion as adeterminant of marital stability, Demography, 30,3,s5-403.

Parsons, R. N., Nalbone, D. P, Killmer. J. M., &Wetchler, J, L. (2007). Identity development, differ-entiation, personal authority, and degree ofreligiosity as predictors of interfaith marital satisfac-tion. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 35,343-361.

Waldman, K. (2006). Psychotherapy with interculturalcouples: A contemporary psychodynamic approach.American Journal of Psychotherapy, 59(3),227-245.

Weigel, D. J.. & Ballard-Reisch, D. S. (1999). The influ-ence of marital duration on the use of relationshipmaintenance behaviors. Communication Reports,12(2),59-70.

Wubbolding, R. E. (1988). Using reality therapy. NewYork: Harper & Row.

Zink. D. W. (2008). The practice of marriage and familycounseling and conservative Christianity, In J. D.Duba Onedera (Ed.), The role of religion andmarriage and family counseling (pp. 55-72). NewYork: Taylor and Francis.

The author may be contacted at [email protected]

International Journal oi Reality Therapy > Fall 2009 • Vol.XXIX, number 1 • 17

1,-,

';;.'~~1

:;~,~i11

>;1N1

\ ,,:J

,'j,l:!.

~~~<3K<

~:;1<-'i:':~:':::.{;.~;i~'~,[~f:~~~~I'-~.-~"I:;.>;,: .?§j.~1'.!l

l~%:-',1: > .'1ii

Coaching for a Vision for Leadership"Oh the places we'll go and the thinks we can think"

Michael Bell and Sylvia Habel

The first author works at Flinders University, Adelaide, and botli authors run a consulting partnershipcalled Leading Potential ill South Australia

ABSTRACT

Research recognizes the role of values, beliefs andother character dispositions in the enactment of leader-ship. Researchers on Servant Leadership have identified aset of character attributes alongside a well described list ofactions of servant leaders in motion. This research reportson the Choice Theory based coaching processes used tohelp the first author develop total behavior that is congru-ent with that of a Servant Leader. The first author isreferred to as the leader and the second author as thecoach.

Leader: Servant-leadership described for me a waythat a leader could profoundly respect other human beingsand yet still operate to achieve organizational goals.Greenleaf describes Servant Leadership in terms of itseffect on others:

"Will all of the people touched by that leader's influencegrow as persons? Will they, while being served, becomehealthier, wiser, freer, more likely themselves to becomeservants? And what will the effect be on the least privilegedin society; will that person benefit or, at least, not be furtherdeprived?" (1970)

As I read further, I realized that a servant leader'svision for leadership was integral to the character of thatperson. For me, that would mean. 'I do servant leadershipbecause of my character (who I am)'. So if, "who I am"was to be the motivating force behind my action as aservant leader, then I would need to change that "who Iam" so it automatically motivated the actions and thinkingof a servant leader.

The question then was: "How do I change who I am?"

Coach: The leader's agenda for personal change needsto be clearly defined and the coaching processes need tocontinually refine that agenda into what becomes thevision for leadership. As a coach, my agenda does notconcern itself with the content of the leader's vision,although I could not agree to help the leader become lesseffective or more damaging to meeting the needs ofothers. My agenda was to maximize the effectiveness ofthe coaching to allow for change at the level of TotalBehavior.

18 • International Journal of Reality Therapy. Fall 2009 • VoI.XXIX, number 1

Leader and Coach: Together we agreed that theagenda for change would consist of building congruenceacross the elements of Total Behavior (as indicated inFigure 1) and with an enactment of the character of theservant leader. The choice of actions was described in theliterature (Page and Wong, 20(6) and would be used in aplanned way in each leadership context. The choice ofthinking would arise from the quality world images andbeliefs of the leader and, over time. these would becomeclearer and more congruent with what the literaturedescribed as the character of the servant leader. The phys-iology would be used as an indicator of congruence ofaction, thinking. and needs meeting while acting as aservant leader in eaeh context.

I DEStRED I---.--.§

Figure I: Overview of complete planning process

Leader: I knew from my reading of the literature(Laub, 1999; A bel, 2000; Russell and Stone, 2002;Sendjaya and Sarros, 2002; Stone, Russell and Patterson,2004) that the first step toward effective leadership is selfawareness. My agenda and the permission I had given thecoach would mean an intense increase in my level of selfawareness and my effectiveness at interrogating thatfurther for myself. If I wanted to be a leader who remainedhumble, served the growth of others and was effective inmeeting my own needs, I would need to become,absolutely aware of the processes for achieving that as well Ias how to restructure my inner realm. For me, the absoluteagenda was to achieve a consistent state that was rein-forced by the mind-body system in action. The '"uncomfortable physiology of incongruent behavior would "'.mean work needed to be done.

.~

I:~~,

Ii·.~d

Table I:Questions used to understandingphysiological responses

Understanding Physiological Responses

1.2.3.4.5.6.7.8.9.10.

Did you need to feel more connected?Did you need to be free to/free from ...?Were you feeling safe, organized, on top?Did you need to feel useful, powerful and effective?Did you need some fun, to be stretched, inspired?What did you need?What was this feeling about specifically?What do you think it's telling you?When have you had this physiology/feeling before?Is this a response to a new situation/plan or action?(nerves/excitement)?

Coach: What Ineeded was access to the leader as closeas possible to the time that the uncomfortable physiologymade its presence felt. This would enable me to help himevaluate what the 'message' from the physiology was whileit was fresh. I asked questions like those in Table 1.

Leader: In most cases I was quickly able to identifywhat the message was through my thinking. In some cases,the logistics of making contact with the coach meant Icould not examine the physiology for some days. While Ilearned to do it for myself, I occasionally could find noways to understand the confusion within. On both of theseoccasions the coach had me use the processes in Table 2 tomake progress.

Table 2: Reading Physiology

Reading Physiology

1. Relive the situation (Visual, Auditory, and Kinesthetic) mentally and thenask: "What am I thinking about the world? What am I thinking about myself?What do I think of others?"

2. Model possible responses based on likeliness (I am feeling X andtherefore could be thinking 1,2,3 .... )