Umberger 2002 Notions of Aztec History: The Case of the 1487 Great Temple Dedication

Transcript of Umberger 2002 Notions of Aztec History: The Case of the 1487 Great Temple Dedication

The President and Fellows of Harvard College

Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology

Notions of Aztec History: The Case of the Great Temple DedicationAuthor(s): Emily UmbergerSource: RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, No. 42 (Autumn, 2002), pp. 86-108Published by: The President and Fellows of Harvard CollegeThe President and Fellows of Harvard CollegeThePresident and Fellows of Harvard College acting through the Peabody Museum of Archaeology andEthnologyPeabody Museum of Archaeology and EthnologyPeabody Museum of Archaeology and EthnologyStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20167571Accessed: 14/10/2010 23:07

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available athttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unlessyou have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and youmay use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained athttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=pfhc.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printedpage of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

The President and Fellows of Harvard College and Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology arecollaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics.

http://www.jstor.org

86 RES 42 AUTUMN 2002

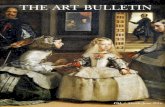

Figure 10. The Dedication Stone. Carved in 1487-1488 to commemorate a ceremony of royal

bloodletting by the reigning ruler Ahuitzotl and representing also his defunct predecessor, Tizoc. Museo Nacional de Antropolog?a, Mexico. Drawing by author.

Notions of Aztec history

The case of the Great Temple dedication

EMILY UMBERGER

In the following, I will reconstruct the course of a

series of events in the Aztec imperial capital?the events

involved in the expansion and dedication of the Templo

Mayor, the Great Temple, of Tenochtitlan between 1483

and 1488.1 I am considering, above all, how the Aztecs

thought about history and how they staged these events

accordingly. To accomplish the reconstruction I employ visual and material evidence in addition to the literary documents that are often used alone. I will first justify the use of these as necessary data.

Aztec history: Some issues

As is well known, the preconquest Aztecs did not

record history with texts of any length. They used

monuments and manuscripts with minimal pictographic and hieroglyphic notations, elaborated through oral

recitation. The alphabetical sources that late modern

historians use come from the colonial period. The

products of both Spanish and native authors, they preserve some aspects of preconquest thought, but most

are European-influenced adaptations of the material

provided by oral informants, older (now lost) written

documents, and pictorial manuscripts. To approach these sources critically, the scholar must understand

differences between preconquest and postconquest native thought, colonial demands on Mexican historians, and the European ideas of history that guided them in

making the data comprehensible and relevant to a new

audience.

Then he or she needs to consider how recent

scholars, in turn, have reshaped the colonial texts. Late

modern historians do acknowledge the early modern

origin of their sources, but do they appreciate fully the

problems and limitations? Few would say that colonial

historians had the same agendas as contemporary

historians, or that what "really happened" can be

recuperated. Such old-fashioned attitudes have been

revealed as increasingly problematic even in parts of the

world where texts exist from the period of study. Late

modern historians do acknowledge the presence of

Hispanic insertions, especially comments on the Aztec

religion, but do they recognize the less obvious re

conceptions of the data in most examples? Do they think that knowledge of preconquest mental structures is

necessary to reconstruction, or realize that some aspects are retrievable? My final question concerns the data of

historical inquiry. Specifically, can one recreate an Aztec

history that excludes the evidence of visual imagery and

archaeological remains?

The answer to this last query is no. Although the late

modern historian usually restricts analysis to the written

data that he/she was trained to study, the material

sources should not be ignored, because too much is

missed by not utilizing them. The archaeological remains are the actual detritus of Aztec events, and

preconquest artworks embody intentional messages from

the same time. The colonial pictorials, in turn, are the

only survivals of an important lost class of preconquest materials that need to be considered along with the

other evidence. To deal with this plethora of visual

and archaeological materials, historians must have

profound knowledge of the objects themselves and the

interpretative methods, or collaborate with specialists who do. It is only through incorporation of multiple data

sets, in fact, that the salient aspects of preconquest

thought can be reconstructed.

Now, at the turn of the twenty-first century, shifts in

theories of knowledge allow for greater appreciation of

native historical thought. It is understood that history is

wedded to politics in a broad sense, and that there are

potentially as many versions of events as interested

parties, with no single version incorporating all agendas. Thus, the historian's recuperation is of different

interpretations from different parties in different periods.

1. This is an expanded version of the paper titled "Notions of

Aztec History" presented in The Romance of Historical Reconstruction

Session at "West by Nonwest: The 50th Anniversary of Pre-Columbian

Art History," a conference sponsored by Columbia University at the

Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 10 to 12, 2000. The basic

questions that inspired this analysis were raised previously by H. B.

Nicholson and Eloise Qui?ones Keber (1983:52-55), Richard Townsend (1979:40-43), and Cecelia Klein (1987:318-324) in

discussions of the Dedication Stone. I thank Esther Pasztory for

suggesting and helping me shape the topic, an anonymous reviewer

for helpful questions, and Gerardo Aldana, Terry Stocker, and Barbara

Stark for important insights.

88 RES 42 AUTUMN 2002

Some of these are nearer in time and space to what

"really happened," and some are more distant Among them, even the more distant versions have interest as

records of their own times and places. As a genre,

history is distinguished from fiction by avowals of truth

or fact and by the presence of named people whose

actions take place in specified settings and time frames.

But history shares with fiction its narrative structures and

metaphorical connectors.2

The accepted parameters of historical recording and

communication have been expanded also in ways that

are more sympathetic to non-European forms. Now

allowed for are oral and visual as well as literary communication systems, fragmented as well as whole

expressions, metaphorical and poetic modes as well as

secularized prose, and improvised presentations as well

as memorized "texts." These changes in Western notions

encourage the historian to incorporate native ideas of

history into modern reconstructions, and to use non

textual materials to do so.3

This is not to say that the interpretation of visual

imagery and other material evidence is unproblematic. Aztec monuments project the changing, sometimes

inconsistent views of Aztec politicians, rendered in

terse, cryptic emblems. Moreover, political matters are

couched in metaphorical imagery featuring supernatural actors and costumed humans, and the ideas behind

these are not detailed visually. Even hieroglyphic names

and dates function like the pictographic motifs that they

accompany. As emblems that go beyond simple naming and dating, they are shorthand representatives of chains

of unpictured associations. Like the pictographs, they served as clues to other links that are difficult to

reconstruct because we do not know the reasoning behind their culturally defined chains of meaning. In

other words, the monuments supply no recognizable narrative connections among motives.

The question of "truth" in history is, of course, relative. Aztec images corresponded to truths current at

the time of their creation, which included, in fact,

reinterpretations of recent events to fit more recent ideas

and circumstances. From our modern point of view, their messages might be characterized as manipulative, even recasting what the most critical historian would

consider facts: what happened, when and where it

happened, for what reason it happened, which actor/s it

involved, and how they were dressed. No doubt, the

preconquest manuscripts that have not survived had the

same political motivations and limitations as the

monuments. Their surviving postconquest descendants

reflect and project additional colonial agendas, even in

examples that look very native (Douglas 2000).

Literary scholars are justified then in their belief that

the remnants of preconquest happenings survive in their

most complete forms in colonial alphabetical narratives

and annalistic histories, and that these contain also

many fragments of preconquest structures of thought and metaphors. No one would suggest abandonment of

these great bodies of literary evidence. Aztec history and

thought cannot be reconstructed through visual remains

alone. On the most obvious level passages within the

body of colonial literature recreate the contexts in which

monuments were made. Fray Diego Dur?n's sixteenth

century history of the Aztecs, for instance, includes

discussions between rulers and their prime ministers

about the imagery to be carved on monuments,

aggressions launched to acquire materials, wars fought for sacrificial victims to initiate monuments, and various

other steps in their creation.4 The focus of ceremonies

on monuments in the central precinct of the city is

highlighted also by their depiction in Dur?n's European

style illustrations (fig. 1). But assertions of important commemorative functions aside, what historical

evidence do actual monuments yield, given the

limitations listed above?

Primarily, they force us to revisit the complex and

seemingly contradictory data associated with particular events in colonial sources, and to test these data. They

2. Many historical thinkers may be acknowledged. Hayden White

(1973, 1987) stands out among theorists dealing with European materials.

3. Recent, original approaches to New World historiography are

found in Rolena Adorno (1986), Susan D. Cillespie (1989), Joanne

Rappaport (1990), Gary Urton (1989), Elizabeth Hill Boone (2000:

Chapters 1 and 2), Eduardo de Jes?s Douglas (2000), and Stephen D.

Houston (2000:168ff). Authors of other classics of historical

revisionism include Alfredo L?pez Austin (1973), Rudolph Van

Zantwijk (1985), H. B. Nicholson (1978), Nigel Davies (1980), and

Tom Zuidema (1990). Some of these New World studies use the visual

materials with great skill and subtlety.

4. For the Spanish version, written between 1579 and 1581, see

Duran 1967, vol. 2. For an English translation, see Doris Heyden's edition (Duran 1994), which is more faithful to the original manuscript. Parallel passages are found in the later cognate Cr?nica

mexicana, which was written in about 1598 by Hernando Alvarado

Tezoz?moc (1980), a descendant of the Aztec royal family. Duran and

Alvarado Tezozomoc's accounts differ in details but are believed to

have derived their basic outlines from a now lost manuscript, dubbed

the Cr?nica X, written in the Aztec language by an earlier, probably native author using the newly acquired alphabetical writing system.

Together the two manuscripts provide the most detailed colonial

narrative surviving on the course of preconquest Aztec history.

Umberger: Notions of Aztec history 89

fM/V 2$?

Figure 1. The Aztec ruler Axayacatl and his prime minister Tlacaelel discuss the form of a new

"stone of the sun" during its initiation (from Duran 1867-1880).

give us officially instituted dates from the period of

production, clues to chains of associations in their

imagery, and?when compared with earlier and later

data?they reveal instances of changing agendas and

reconceived history. In the following, I am using

preconquest remains and a colonial manuscript to

supplement and question the alphabetical sources. My

purpose is to reveal how the Aztecs staged a series of

ritual and historical events, while also accommodating

unanticipated happenings. I am addressing here only the

contribution of monumental data, as this particular series of events has little in the way of archaeological remains other than the architectural structure that was

the result of the building expansion (probably Phase VI

of the Templo Mayor).

The Aztec calendar: Structures and symbolism

Necessary to this reconstruction is an explication of

the functioning of the 260-day divinatory cycle

(tonalpohualli, "count of divinatory days") within the

months of the 365-day solar year (cemilhuitlapohualli, "count of feast days"), and the relationships of both to

the fifty-two-year cycle (xiuhmolpilli, "bundle of

years").5 After the conquest, Spanish friars like

Bernardino de Sahag?n (1950-1982:bks. 2 and 4-5)

described the two day-counts separately. This is not

surprising, as no European writing at the time

understood how they worked together. Even today, they are treated as separate systems in all but numerical

respects. Since the hieroglyphic dates on monuments

derived their names from the 260-day divinatory count

(here called the Trecena Cycle), that count is of

particular interest. In the past two decades, study of

these inscribed dates together with hieroglyphic names,

imagery, and style have made it possible to place many monuments in their approximate years of ritual use

(Umberger 1981a and elsewhere). Their more exact

placement within the years themselves requires a

detailed reconstruction of how the different counts

worked together. The events to be highlighted in a ritual year were

determined by specialists who saw the course of the

5. The name of the conjunction of days of the 365-day cycle is

unclear. I prefer the term cemilhuitlapohualli to the one chosen by

Tena (1987:11), xiuhtlapohualli ("year count"), in his discussion of

both terms.

90 RES 42 AUTUMN 2002

present as linked to the course of the past. Aztec records

of the past probably originally featured a continuous

and intertwined sequence of events that colonial

scholars subsequently categorized separately as myth and history. In this reconception they relegated

obviously cosmic and mythical aspects to the deep past and secularized the later period, which they considered

history proper. The Aztecs themselves had cast this later

period in more human terms, but colonial historians

furthered the process by removing the metaphorical

underpinnings. The resulting distinction between

periods, which continues in late modern scholarship, creates a distorted view of non-European thought.

Emphasizing the fictional aspects of mythic events in

order to negate their historicity, historians at the same

time dismiss as irrelevant figurative aspects that were

crucial to Aztec historical thought. This is a profound mistake, as it disrupts intimate, culturally defined

connections between different event-types; much from

the mythic period, in fact, formed typological

precedents for later history. The historical accounts of early colonial times begin

with this distant mythic period,6 consisting of four eras

dominated by their respective suns and the Fifth Era in

which the Aztecs lived. They then proceed through the

initiatory events of the Fifth Era, followed by the rise and

fall of important ancient "Toltec" polities and the events

of Aztec hegemony. Developing further a mode of

thought suggested by scholars like Richard Townsend

(1979:70), I believe that the later political happenings were seen as repetitions related in type to the primordial events. Some primary links were date names, for

instance, the year dates in the fifty-two-year cycle (fig. 3) which called up the specific associations listed beside

them. However, the structural relationship between past and present was conceived more flexibly when it was

necessary to link events of different dates. In these cases,

solar metaphors were used to relate all types of events

and their actors. Comparisons involved the sun's cyclical

positions: its dawning in the east, climb to the zenith,

eclipse, descent/setting in the west, and travel through the Underworld. These positions were used to represent the beginning, success, decline/failure, and end of

human lives, political reigns, calendar cycles, and

periods of agricultural fertility (Umberger 1987; in

process). In addition, the moon, stars, and earth had

their own metaphorical correspondences, usually in

relation to the sun. Over the span of the ritual calendar

the effect was the integration of cosmic and human

events into a sequence of alternating light and dark

periods. The linkage between cosmic events and human

political activities is clearly made in the charter story

underpinning the Aztec system of thought, one version

of which is most fully documented in Sahag?n's Florentine Codex (1950-1982:bk. 3:1-5). This account

describes the rise of the Aztec tribal god, Huitzilopochtli

("hummingbird, left"), as a struggle against other

anthropomorphic gods, following his birth fully armed

from a woman named Coatlicue ("serpents, her skirt") at

a mountain site called Coatepetl ("serpent mountain"). The battle ended in Huitzilopochtli's slaughter of an

army of enemies, his brothers the Centzonhuitznahua'

("400 [or innumerable] southerners"), and their leader, his sister Coyolxauhqui ("bells, painted") (fig. 2). Being the Aztec tribal god, Huitzilopochtli's rise to power

symbolized the Aztecs' political rise, his enemy siblings

represented their enemies, and his "sister'Vleader

represented a ruler who was transformed in defeat

into a woman (Umberger in process). The cosmic

correspondences of settings, actors, and actions of the

story are widely recognized, as are the political dimensions. Coatepetl and Coatlicue both represent the

earth, while Huitzilopochtli's "birth" is like the sun rising in the morning from the earth to defeat the moon and

stars (Seler 1960-1961, 3:327-328; 4:157-167;

Umberger 1987). It is also well known that the setting of

the story was in the city of Tenochtitlan in the form of

the pyramid-mountain of the Templo Mayor, which

represented Coatepetl, and nearby structures, like the

ballcourt and skull rack. In this setting, contemporary events were staged to follow the events of the past?the "historical" past of the Chichimecs and Toltecs, as well

the distant mythical past. Thus, in addition to Coatepetl, the forms and decorations of buildings referred to

revered cities like Calixtlahuaca, Culhuacan, Tenayuca, Xochicalco, Tula, and Teotihuacan. Unfortunately, the

layout of these structures in the city is relatively vague at

this point; but ceremonial activities focusing on them can be "mapped" in time.

Given the importance of connecting the past and

present, the priests who scheduled events had to consult

both the "books of days" (tonalamatl), which pictured the deity-actors and event possibilities of days in the

Trecena Cycle, and the "books of years" (xiuhamatl),

6. I suggest use of the terms metaphorical and figurative when

appropriate to replace mythical, as they bypass the distracting issue of

belief (that is, the assumption that non-Western systems of thought involved unanimous belief by the members of a society). The early

period of Aztec history can still be called myth, with the proviso that

its allegorical functions be recognized. For a lengthy analysis of Aztec

metaphorical thought, see Umberger (in process).

Umberger: Notions of Aztec history 91

Figure 2. Florentine Codex illustration of Huitzilopochtli's defeat of Coyolxauhqui and his other enemy siblings at

Coatepetl. Drawing by author (after Sahag?n 1905-1907).

which pictured the deity-actors and humans taking the

roles of deities during events of the past. The proper course of action could be determined only through

balancing the locations of particular days within the

calendar's structure with the associations their names

had accumulated through past experiences. Modern scholars have convincingly correlated the

Aztec 365-day solar year with years in the European calendar, as seen in figures 3, 4, and 5. Aztec years bore

the names Tochtli ("rabbit"), Acatl ("reed"), Tecpatl ("flint

knife"), and Calli ("house"), which are called "year

signs" by modern scholars. Each year in the fifty-two

year cycle had a distinct name, resulting from the

combination of the four signs alternating in order and

joined with the numbers 1 through 13. This pairing of

signs and numbers was repeated four times (fig. 3). The fifty-two-year cycle was not used solely to name

passing units of time, as it is now treated (e.g. Caso

1967). It was a great ceremonial cycle that reiterated the

events of pre-Aztec and Aztec history in a meaningful

sequence. In the deep or "real" time of annals like the

Historia de los mexicanos por sus pinturas (1973), the Leyenda de los soles (1975), the Anales de

Cuauhtitlan (1975), Alvarado Tezozomoc's Cr?nica

mexic?yotl (1975), the Anales de Tlatelolco (1980), and

Chimalpahin's Relaciones originales (1965), the events

spanned many cycles, but within the fifty-two-year cycle these same events were celebrated according to date in

a compressed and reordered sequence (fig. 3).7The first

year was 1 Tochtli, the anniversary of the separation of

the earth and sky of the Fifth Era. The second year, 2 Acatl, celebrated the lighting of the first fire and

"smoking of the sky" by the god Tezcatlipoca ("mirror, its smoke"), while the world was still without a sun. At

the beginning of the second quarter, 1 Acatl was a year date pertaining principally to Quetzalcoatl ("feathered

serpent"), the legendary deified ruler of the Aztecs' most

admired predecessors, theToltecs of Tollan (modern

Tula, Hidalgo). At the middle of the year count, 13 Acatl

and 1 Tecpatl were the anniversary years of the

births/first appearances of the sun and the Aztec god

Huitzilopochtli, respectively. Although separated by

many years in "real" time, the juxtaposition of their

dates in the fifty-two-year cycle emphasized the Aztecs'

close ties of dependency and responsibility to the sun.8

This juxtaposition also signaled well-known social

and political metaphors, wherein the rising sun was

synonymous with success, as indicated before. In

the case of the fifty-two-year cycle, the successful

dominance of the Aztec god over all others was

conceived metaphorically as another sunrise. The date

13 Acatl was simultaneously the year of the birth of the

moon. Having lost a contest with the sun, the moon

became a pale, nighttime reflection of the brighter orb, and a metaphorical analogue of all forces losing to the

Aztecs. The year after 1 Tecpatl, 2 Calli, was the

7. See Umberger 1981a:209-212, 200-206, and Umberger 1981 b for the sources of associations of dates to events and gods.

8. Thirteen Acatl is associated solely with the birth of the sun,

while 1 Tecpatl pertained to multiple, comparable Aztec events: their

departure from their homeland, their War of Independence in 1

Tecpatl, 1428-1429, and the "birth'Vappearance of their patron god,

Huitzilopochtli.

92 RES 42 AUTUMN 2002

PRIMARY /GENERAL

ASS'NS OF YEAR NAMES

TEMPLO MAYOR/TM PHASES

PLAQUES; OTHER EVENTS

Fifth Era begins

Tezcatlipoca creates first fire

1 Tochtli

2 Acatl

3 Tecpatl 4 Calli

5 Tochtli

6 Acatl

7 Tecpatl 8 Calli

9 Tochtli

10 Acatl

11 Tecpatl 12 Calli

13 Tochtli

1454-5

1455-6

1456-7

1457-8

1458-9

1459-60

1460-1

1461-2

1462-3

1463-4

1464-5

1465-6

1466-7

1 Tochtli Plaque on TM IV

New Fire Ceremony

Motecuhzoma I's Stone of the Sun?

Quetzalcoatl born

Sun born

1 Acatl

2 Tecpatl 3 Calli

4 Tochtli

5 Acatl

6 Tecpatl 7 Calli

8 Tochtli

9 Acatl

10 Tecpatl 11 Calli

12 Tochtli

13 Acatl

1467-8

1468-9

1469-70

1470-1

1471-2

1472-3

1473-4

1474-5

1475-6

1476-7

1477-8

1478-9

1479-80

AXAYACATL'S accession; 3 Calli Plaque on TM IVb

TM V built?

Axayacatl Stones of Sun initiated?

PRIMARY/GENERAL

ASS'NS OF YEAR NAMES

TEMPLO MAYOR/TM PHASES

PLAQUES; OTHER EVENTS

Huitzilopochtli born

Tenochtitlan founded 1325-6

Triple Alliance Empire founded 1431-2

1 Tecpatl 2 Calli

3 Tochtli

4 Acatl

5 Tecpatl 6 Calli

7 Tochtli

8 Acatl

9 Tecpatl 10 Calli

11 Tochtli

12 Acatl

13 Tecpatl

1480-1

1481-2

1482-3

1483-4

1484-5

1485-6

1486-7

1487-8

1488-9

1489-90

1490-1

1491-2

1492-3

TIZOC's accession

TM VI begun

TM VI pyramid and Tizoc's Stone of Sun initiated

AHUITZOTL's acession

TM VI shrines initiated; 8 Acatl on Dedication Stone

Twin City Tlatelolco founded 1337 1 Calli

2 Tochtli

3 Acatl

4 Tecpatl 5 Calli

6 Tochtli

7 Acatl

8 Tecpatl 9 Calli

10 Tochtli

11 Acatl

12 Tecpatl 13 Calli

1493-4

1494-5

1495-6

1496-7

1497-8

1498-9

1499-1500

1500-1

1501-2

1502-3

1503-4

1504-5

1505-6

Ahuitzotl's Stone of Sun initiated?

MOTECUHZOMA ll's accession

TM VII built?

Figure 3. The reconstruction of the Aztec Xiuhmolpilli (fifty-two-year cycle) extending from 1 Tochtli to 13 Calli, 1454-1506. Designed by Mookesh Patel.

Umberger: Notions of Aztec history 93

anniversary year of the foundation of the city of

Tenochtitlan in 1325-1326. The third year after 1

Tecpatl, 4 Acatl, was the anniversary of the beginning of the Aztec Triple Alliance Empire of Tenochtitlan, Tlacopan, andtexcoco in 1431-1432. The first year of

the fourth quarter, 1 Calli, was the anniversary of the

foundation of Tenochtitlan's "twin" city, Tlatelolco, on

the same island in 1337-1338.

Obviously, the first half of the cycle meshed pre Aztec cosmic and political events, while the second

half, beginning with 1 Tecpatl, was dominated by the

Aztecs and comprised a great period of symbolic solar

light. Actually, several layers of history, and alternating

periods of light and dark, were accommodated in this

and other temporal cycles. First were creation events

involving the sun, sky, moon, stars, earth, and

Underworld, and cosmic struggles between forces of

darkness and light. Second were events associated with

theToltecs: a period of Chichimec-like migration, urbanization at Tula, and finally the golden age of

Quetzalcoatl's rule and his struggle with Tezcatlipoca. The triumph of Tezcatlipoca brought a return of

symbolic darkness and political divisiveness. Third were

events associated with the Aztecs?the ones destined to

unite this divided world?from their own migration

period to their urban settlement at Tenochtitlan. Through the experiences of the migration period (including the

events at Coatepetl) and their early settlements in the

Valley of Mexico, they eventually became worthy inheritors of Toltec culture. Having divided into two

groups and settling on the islands of Tenochtitlan and

Tlatelolco in LakeTezcoco in the early fourteenth

century, they gained independence from their Tepanec overlords in 1 Tecpatl, 1428-1429. After the formation of the Triple Alliance Empire four years later in 1431

1432, they could then realize their Toltec-inherited right to political hegemony.

Each year in the fifty-two-year cycle consisted of 365

days, divided into eighteen month-like veintenas

(Spanish for the twenty-day periods), plus five leftover

days (figs. 4 and 5). Overlapping this Veintena Cycle were multiple occurrences of the Trecena Cycle, each of

which consisted of twenty week-like trecenas (Spanish for the thirteen-day periods). The veintenas, like months,

occupied the same positions in every year, and they were named for activities that took place during the

twenty days. The last day of each veintena was its feast

day. The day that gave its name to the year (called the

year-bearer) was found in the same two positions every

year, first as the feast day of Veintena IV (Hueitozoztli,

"great vigil") and second as the feast day of Veintena

XVII (Tititl, "stretching/shrinking"). The symbolic course

of the veintenas is poorly understood; their activities as

reported in colonial sources are complex to the point of

incomprehensibility as a system. Still, it may be said

that, whatever the individual emphases of different

years, the typical course of veintenas was directed

toward a climax of public ceremonies on the second

year-bearer day at an important temple. In addition,

preparation for these ceremonies probably began in

Veintena XI (Ochpaniztli, "sweeping") with the

ceremonial refurbishing of the city's temples. In contrast to the veintenas, the trecenas, like weeks,

changed their positions in the year. The days of the

Trecena Cycle were named through the combination of

the numbers 1 through 13 with twenty non-numerical

signs, among them the four year-signs. Since the

Veintena and Trecena Cycles ran together, each day had a name and position in an individual trecena plus a

position in an individual veintena. In the year 4 Acatl

(fig. 4) the first day of Veintena 1, Atlcahualo, was called

3 Ocelotl ("jaguar") for its position in the Trecena Cycle. It could also be designated as the first day of Atlcahualo,

or Atlcahualo 1. As time passed, the trecenas changed

position in relation to the veintenas. Thus, the first day of

each year was always Atlcahualo 1, but it was 3 Ocelotl

only once in a fifty-two-year cycle. At the tops of the diagrams in figures 4 and 5 are the

veintena names in N?huatl and English. Below them are

the Roman numerals that indicate their ordering, and

above them are their month and day dates in the present

European calendar. Along the left sides are the twenty

day-signs of the Trecena Cycle, numbered 1 through 20 to indicate their positions within the year's veintenas. In

the body of each diagram the matching of the day-signs with the repeating sequence of numbers 1 through 13

yields the names of individual days. Trecena 1, the first of every cycle begins with the day 1 Cipactli ("caiman")?the first numeral plus the first sign?and

proceeds to 13 Acatl. Trecena 2 begins with 1 Ocelotl

and proceeds to 13 Miquiztli ("death"), and so on.

The four day-signs that shared names with the fifty two years also shared the associated gods and event

types of particular dates, and this symbolic aspect tied

the day and year cycles together. In the year 1 Tochtli, for instance, the primary ceremony was on the day 1

Tochtli, at the end of the penultimate month. The day and the year had the same meaning; they both marked the anniversary of the beginning of the Fifth Era. The Trecena Cycle had sixteen additional day-signs, the non

year-signs, and some dates among them also had distinct

meanings, depending on their positions within the count

94 RES 42 AUTUMN 2002

4 Acatl / Reed 1483-4

Day Symbols -I = = *l > > ? > > X X

> > X X

Ocelotl/Jaguar 1 10 4 11 5 12 6 13 7 ?2 8 10 4 11 5 12

Cuauhtli / Eagle 2 115 12 6 13 7 719 8 10 4 11 5 12 6 13 Cozcacuauhtli / Vulture 12 6 13 7 /16 8 10 4 11 5 12 6 13 7

Ollin / Movement 13 7 /13 8 10

Tecpatl / Flintknife 5 /io 8 10 4 11 12 6 13 7 7io 8

?16

11 5 12 6 13 7 /is 8

Quiahuitl / Rain 6 10 4 11 5 12 13 7 /7 8 10

X?chitl / Flower 10 4 11 5 12 6 13 74 8 10 11

Cipactli / Caiman 10 4 11 12 6 13 7 li 8 10 4 11 5 12 Ehecatl/Wind 11 5 12 6 13 7 ?18 8 10 4 11 5 12 6 13

Calli /House 10 12 6 13 7 /is 8 10 4 11 5 12 6 13 7 ?15

Cuetzpallin / Lizard 11 13 7 712 8 10 11 12 6 13 7 ?12 8

Coatl / Snake 12 79 8 10 4 11 12 6 13 7 ?9 8

Miquiztli / Death 13 10 4 11 12 13 7 76 8 10 4

Mazatl / Deer 14 10 4 11 12 6 13 ?3 8 10 4 11 5 Tochtli / Rabbit 15 11 5 12 6 13 7 ?20 10 4 115 12 6

Atl / Water 16 12 6 13 7 717 8 10 4 11 5 12 6 13 7 Itzcuintli / Dog 17 13 7 /14 8 10 4 11 5 12 6 13 7 /14 8

Ozomatli / Monkey 18 111 8 10 4 11 5 12 6 13 7 In 8 Malinalli / Grass 19 10 4 11 12 6 13 7 la 8 10

Acatl / Reed 20 10 4) 115 12 6 13 7 Is 8 10 '4 ) 11

First Trecena Cycle Second Trecena Cycle

Key

1 = first day of trecena with trecena number next to it

^B = 4 Ollin, moveable feast dedicated to the sun

4 = year-bearer days at end of Veintenas IV and XVII, Hueitozoztli and Tititl

The European year 1484 began on the day 13 Cozcacuauhtli in Veintena XVII, Tititl

Figure 4. The reconstruction of the year 4 Acatl, 1483-1484, based on Rafael Tena's correlation (1987).

Designed by Mookesh Ratel.

Umberger: Notions of Aztec history 95

8 Acatl / Reed 1487-8

Day Symbols Ocelotl /Jaguar Cuauhtli / Eagle 2 ?

Cozcacuauhtli / Vulture

Ollin / Movement

Tecpatl / Flintknife 5 g

Quiahuitl / Rain 6 ?

X?chitl / Flower 7 ?r

Cipactli / Caiman 8

Ehecatl /Wind

Calli/House 10

Cuetzpallin / Lizard 11

Coatl / Snake 12

Miquiztli / Death 13

Mazatl / Deer 14

Tochtli / Rabbit 15

Atl / Water 16

Itzcuintli / Dog 17

Ozomatli / Monkey 18

Malinalli/Grass 19

Acatl / Reed 20

11

12

13

O

?2 8 10 4 12 6 13 7

104 115 12 6 13 7 7 19 8

10 4 12 6 13 7 716 8

115 126 137 7i3 8

12 6 13 7 7io 8 10 4 11

13 7 77 8 10 4 11 5 12

74 8 10 4 11 5 12 6 13

7i 8 10 4 11 5 12 6 13 7

104 115 12 6 13 7 7 18 8

10 4 11 12 6 13 7 7 is 8

115 12 6 13 7 712 8 10

12 6 13 7 79 8 10 4 11

13 7 ^76 10 4 11 5 12

73 8 10 4 11 5 12 6 13

10 4 11 5 12 6 i3 7 y I 104 115 12 6 13 7 717 8

104 115 12 6 13 7 7 14 8

11 5 12 6 13 7 1 ii 8 10 4

12 6 13 7 7s 8 10 4 11 5

13 7 7 5*8) 10^4 12 6

72 8

10 4

BE

10 4 11 5

11 5 12 6

12 6 13 7

6 13 7 >77|

74 8

7 1 8

10 4

10 4 115

11 5 12 6

12 6 13 7

13 7 leT" 13 8

10

10 4 11

10 4 M 5 12 | 11 5 12 6 13

12 6 13 7

13?7 15^8^2" Second Trecena Cycle Third Trecena Cycle

Key

1 = first day of trecena with trecena number next to it

^P = 4 Ollin, moveable feast dedicated to the sun

8 = year-bearer days at end of Veintenas IV and XVII, Hueitozoztli and Tititl

^ =

days highlighted in text

8

|9~

LLJL LLL rnr 79

It

PL ML LL NT

r?? rrr M2~

E3.

00 00

id O.

Tecpatl

The European year 1488 began on the day 4 Cozcacuauhtli in Veintena XVII, Tititl.

The Aztec Year 9 Tecpatl/Flint 1488-9 began on the day 8 Quiahuitl, Atlcahualo 1.

The feast day of Atlcahualo was 1 Tecpatl, which also marked the end of the

ceremonial period of the Great Temple dedication.

Figure 5. The reconstruction of the year 8 Acatl, 1487-1488 (after Tena 1987: table 2, with additions). Designed by Mookesh Pate I.

96 RES 42 AUTUMN 2002

and relationships to other days. Like year-sign dates,

non-year-sign dates could be linked to deities, different

aspects of a single deity, and, of course, associated

event-types. For instance, the non-year-sign date 1

Miquiztli was dedicated to Tezcatlipoca. All days with

special associations, whether year signs or not, are

called "moveable feast days'' by modern scholars (we do

not know their Aztec name), and the Aztecs had to

acknowledge the gods and actions attached to them, no

matter where the days fell in the Veintena Cycle. It

should be noted also that moveable feast days that

coincided with veintena feast days were doubly

important. Acatl years, like those diagrammed in figures 4 and 5, had more of these coincident dates than other

years, because the feast days 13, 7, 1, 2, and 4 Acatl all

had symbolic associations in the Trecena Cycle. In the

year 8 Acatl these were the feast days of ten of the

eighteen veintenas.

Like the macro-cycle of the fifty-two years, the micro

cycle of the trecenas reiterated the events of history, but

within a period of days. Because of their shared system of named dates, the symbolic associations of the years

were transferred to the Trecena Cycle, where they followed the same general sequence, although altered

somewhat by the insertion of the sixteen additional signs (their sequence can be followed in figure 5). The day that I believe began the sequence was 1 Tochtli, which

bore the same name as the first year of the Fifth Era and

the first year of the fifty-two-year cycle, but it was in the

final trecena of a waning Trecena Cycle. Thirteen days later, 1 Cipactli (a non-year-sign) began the next cycle.

This day-name symbolized the initiation of time

(Sahag?n 1950-1982:bks. 4-5:1). Time having been a

crucial instrument of political control, 1 Cipactli, not

surprisingly, was an appropriate day for Aztec ruler

coronations (Duran 1994:318).9 Thirteen days later, 13

Acatl commemorated the appearance of the sun, just as

the year 13 Acatl did in the fifty-two-year cycle (Caso

1927:35-36; Umberger 1981a:203-204). Four days after

that, in Trecena 2, 4 Ollin ("movement") celebrated the

day when the sun began to move (Sahag?n 1950-1982:

bks. 4-5:6). The seventh day of Trecena 3, 7 Acatl, initiated an important twenty-day period devoted to

Quetzalcoatl (Codex Telleriano-Remensis, f. 10r; in

Qui?ones 1995:23, 168). The period ran through Trecena 4 and ended on 1 Acatl, the first day of Trecena

5. Both 7 Acatl and 1 Acatl years were devoted to

Quetzalcoatl in the fifty-two-year cycle too (on the year 7 Acatl, see Umberger, 1981a:98-105, 127-132; on 1

Acatl, see also Sahag?n 1950-1982:bks. 4-5:29). Trecena 6 began with 1 Miquiztli, the day devoted to

Tezcatlipoca as "enslaver of men" (ibid.: 33-36) and the

first of an important fifty-two-day period of darkness, devoted to him and to Huitzilopochtli before the latter's

(solar) rise. Trecena 7 began with 1 Quiahuitl ("rain"), a

day of sacrifices in honor of the current ruler (ibid.:42). After this, in Trecena 8, at the approximate middle of the

fifty-two-day period, 2 Acatl was another day of

Tezcatlipoca (ibid.:56), this time as fire-lighter, the date

and activity being the same as in the fifty-two-year

cycle. The period ended with 1 Tecpatl at the beginning of Trecena 10, a day, like 1 Tecpatl in the year count, dedicated to Huitzilopochtli's "dawning" (ibid.:77-79). As in the fifty-two year cycle, in the Trecena Cycle the celebration of the successful Huitzilopochtli was

a metaphorical repetition of the cosmic, solar event

on 13 Acatl, and signified his dominance over all

other gods. The symbolic structure of the Trecena Cycle had

some similarities with that of the Fifty-two-year cycle. In

both, 1 Tecpatl marked the passage of half a cycle since

1 Tochtli, although a different number of units was

involved (130 days in the Trecena Cycle and twenty-six

years in the fifty-two-year cycle). In addition, in both

cycles the first half contained the important dates of

creation events and the powerful pre-Aztec gods, while

the more specifically Aztec dates fell at the center and

in the second half. Within these general outlines, there

are differences in details, notably in the sequence of

date names as well as the number of units of time

between them, which vary greatly. For instance, in the

fifty-two-year cycle, the date 2 Acatl is immediately after

1 Tochtli. In the Trecena Cycle 2 Acatl occurs 105 days after 1 Tochtli (approximately six trecenas), even after

the birth of the sun and the activities of Toltec

Quetzalcoatl. Likewise, the dates of the sun's birth, 13

Acatl, and Huitzilopochtli's rise, 1 Tecpatl, which are in

adjacent years at the center of the fifty-two-year cycle, are separated by 105 days in the Trecena Cycle. However, sense can be made of even such radical

changes, in that the deities who ruled these dates were

9. Note that 1 Tochtli and 1 Cipactli were both initiatory trecenas

straddling the border between Trecena Cycles. This type of doubling was necessary to ease transition between both day and year cycles and

to avoid the danger inherent in abrupt, impermeable boundaries (see

also Broda 1969:44). Similarly, a Trecena Cycle bridged the end of one

fifty-two-year cycle in the year 13 Calli, 1505-1506, and the

beginning of the next in 1 Tochtli, 1506-1507, as I will explain in

future work. A single day on which all cycles ended would have been

a very dangerous time; so the occurrence of such a day was made

numerically impossible by the structure of the calendar. In other

words, no year began on the day 1 Cipactli, the first day of the

Trecena Cycle.

Umberger: Notions of Aztec history 97

placed in the same cosmic scenarios in both year and

day cycles. Tezcatlipoca lights fire during a time of

darkness, and Huitzilopochtli rises like the sun at the

end of the period.10 The most important change from the fifty-two-year

cycle to the Trecena Cycle was the emphasis placed on

the political sequence of the gods Quetzalcoatl,

Tezcatlipoca, and Huitzilopochtli, who represented the

Toltecs, their post-Toltec successors, and the Aztecs,

respectively. In historical sources all three deities had

been involved in creation but returned many year cycles later in altered forms as political patrons. Quetzalcoatl,

for a while the successful ruler of Tollan, was then

defeated and driven from that city by Tezcatlipoca (Nicholson 1957; L?pez 1973). By early Aztec times

Tezcatlipoca had become the patron god of the

powerful Tepanec and Acolhua polities in the Valley of

Mexico, but, with the rise to dominance of Aztec

Tenochtitlan, he became a "cadet" to the Aztec patron

god, Huitzilopochtli (Umberger 1996b:250-251, and in

process). In the Trecena Cycle, although the time periods devoted to these gods fall after the events of cosmic

creation, some of their actions are comparable in being originary and primordial as much as political (for

instance, Tezcatlipoca's fire-lighting and Huitzilopochtli's solar emergence). Or, it might be said that the political significance of events was backed by supernatural powers.

Given the complex reappearance of actors and

comparable events on specific dates, as each Trecena

Cycle passed, there were simultaneous celebrations of

happenings from different periods on the moveable feast

days. In other words, although the sequence of dates in the Trecena Cycle, with its greater number of units,

mimicked more closely the sequence of "real history" than did the fifty-two-year cycle, it was still a condensed version. The cosmic, Toltec, post-Toltec, and Aztec

periods outlined above recurred in that relative order, but references to the different periods also overlapped. Thus, the ceremonial costumes worn on days of

significance in several cycles conflated political and

cosmic powers in ways that we do not yet understand.

Having established the complexity of references in the ceremonies of the Trecena Cycle alone, another

important questions arise: how did the veintenas

10. The other important symbolic dates in the fifty-two-year

cycle?2 Calli, 4 Acatl, and 1 Calli?do not make comparable sense in

their patterning, and perhaps they were not conceived as part of this

important sequence in the Trecena Cycle. 7 Acatl also takes radically different positions in the two counts.

accommodate the appearance of supernatural

powers on the moveable feast days, and how were

contemporary historical events inserted?

The question of historical commemoration brings up

again the interrelationship of days and years. Some

historical events could be scheduled for the anniversary year, such as the celebrations in honor of the

appearance of the sun and Huitzilopochtli that must

have taken place in the years 13 Acatl and 1 Tecpatl (1479-1481), but the Aztecs also had to celebrate such

charter events in years of other names. Five kings ruled

during the fifty-two-year cycle from 1 Tochtli to 13 Calli, 1454 to 1506 (fig. 3), but 13 Acatl and 1 Tecpatl fell

only within the reign of one of these, Axayacatl. In the cases of the other reigns, the celebrations of important events had to be transferred to days of the same names

in the Trecena Cycle. In the day cycle every significant anniversary date recurred at least once a year, and less

predictable events such as rulers' deaths and accessions could be scheduled either on fixed day dates, like 1

Cipactli, or other, variable but appropriate dates. This use of the day-names to represent years did not

solve all problems of scheduling. Because of the

changing positions of the trecenas within the individual

years, their overlap within the veintenas changed too.

Sometimes the overlap was not propitious. In years like 4 Acatl (fig. 4), the symbolically important 130-day

period from 1 Tochtli to 1 Tecpatl fell in the middle of the year, ending long before the year's proper ceremonial climax at the end of the penultimate veintena. Perhaps this split was not a problem for some

types of commemorations, but the sequence of days in other years, like 8 Acatl (fig. 5), allowed a ritual schedule in which the ceremonial climaxes of both Trecena and Veintena Cycles coincided, an important co-occurrence for major celebrations.

Although the different lengths of trecenas and veintenas produced differences like these between years, balance and linkage could be achieved by taking

advantage of certain regularities. First, the beginning and end days of the eighteen veintenas bore the same signs

within acatl, tecpatl, calli, and tochtli years, respectively. In acatl years all veintenas began with ocelotl days and

ended with acatl feast days. In tecpatl years the veintenas began with quiahuitl days and ended with

tecpatl days, in calli years they began with cuetzpalin ("lizard") days and ended with calli days, and in tochtli

years they began with atl ("water") days and ended with tochtli days. Years of the same sign were comparable also in that their feast days, in addition to having the same sign as the year itself, followed a set sequence. A

98 RES 42 AUTUMN 2002

Figure 6. Codex Telleriano-Remensis, folio 38v. Events of the years 4 Acatl and 5 Tecpatl, 1483-1485.

Biblioth?que Nacionale, Paris. Drawing by author (from Qui?ones 1995:80).

second regularity characteristic of every year was the

exact repetition of the day-names of the first five

veintenas, I through V, in the last five veintenas, XIV

through XVIII. Among these matching periods were the

two veintenas that ended with the year-bearer days; near

the beginning of the year was Veintena IV, Hueitozoztli

("great vigil"), and near the end was Veintena XVII, Tititl

("stretching/shrinking"). The Aztecs could use this

coincidence to stage complementary actions in earlier

and later veintenas, especially in the year-bearer veintenas. A third regularity involved the location of the

year-bearer of the previous year of the same sign. Just as

the year-bearers of a current year had set positions within the year, so too did the day of this name; it was

always in the middle of the 360-day block formed by the eighteen veintenas. For instance, in the year 8 Acatl

the day in the middle of the veintena block, 4 Acatl, was

the year-bearer of the previous acatl year. This feature

reinforced the close relationship between years of the

same sign, and could be used to justify a transferral of

ceremonies from one year to another of comparable structure four years later.

Obviously, the scheduling of a year's rituals was a

difficult task and involved numerous decisions, as will

be seen in the historically documented example of the

temple expansion initiated by Tizoc and completed by Ahuitzotl. The structural aspects and regularities of the

system are outlined above. In the following, I will

reconstruct an actual schedule of events, contrasting what Pierre Bourdieu (1977) would characterize as

structure or "theory" and actuality or "practice."

The building of the Great Temple by Tizoc and Ahuitzotl

The cumulative evidence of various sources indicates

that the dedicatory ceremonies at the Templo Mayor honored different stages of the expansion during its

construction from 1483 to 1488, the Aztec years 4 Acatl

to 8 Acatl. It is also evident that ceremonies were

patterned in both year and day cycles to follow the

events leading up to Huitzilopochtli's triumph on the hill

of Coatepetl, which the temple represented. As will be

seen, some sacrificial victims were dressed as actors at

Coatepetl and are pictured in Telleriano-Remensis as the

Umberger: Notions of Aztec history 99

Figure 7. Codex Telleriano-Remensis, folio 39r. Events of the years 6 Cal I i through 8 Acatl, 1485-1488. Biblioth?que Nacionale, Paris. Drawing by author (after Qui?ones 1995:81).

foci of the major rituals of 5 Tecpatl, 1485-1486, but the details of this year cannot be reconstructed more

specifically. However, in the fifth and final year, 8 Acatl, 1487-1488, manuscript illustrations, sculptures, and

alphabetical histories allow for the reconstruction of activities within both the Trecena and Veintena Cycles.

Logically, the climactic ceremonies were in the

penultimate month of the year, and these focused on the

great sacrifice dedicating the completed temple. This was followed by the triumph of the god Huitzilopochtli early in the following year.

The events of the 1480s are documented in multiple colonial sources, but none is more important for the

present purpose than the pictorial Codex Telleriano Remensis (figs. 6 and 7), which although well known has not been exhausted as a historical source. Folio 38v

documents the years 4 Acatl and 5 Tecpatl, when the

pyramid platform was enlarged over an earlier temple. The next page, Folio 39r, depicts the completed shrines on top of the platform and other events of 6 Calli, 7

Tochtli, and 8 Acatl. The whole sequence begins with the death of the ruler Axayacatl and the succession of

Tizoc. This change in leadership is depicted as having happened in the year 4 Acatl, 1483-1484, but other sources indicate that it probably occurred two years earlier in 2 Calli, 1481-1482 (whether this is true or not

is not important to the argument). Also below 4 Acatl the foundation is laid forTizoc's new temple, and a

sacrificial victim is offered at this time, a matching of event to year that is probably accurate, for reasons that

will become clear later.

The second vignette, under the year 5 Tecpatl (1484

1485), pictures the finished pyramid with the symbol of

Tenochtitlan on top (a cactus, tenochtli, growing from a

stone, tetl). Below to the left a male prisoner is pictured; to the right is a nude woman, who was apparently beaten to death by the warrior next to her. Her body looks like several monumental depictions of the goddess

Coyolxauhqui in her sprawled position and emphasized breasts (Garcia and Arana 1978; Matos 1991). The

Spanish gloss on the lower part of the page names the male prisoner as one of those from Tzinacantepec, a

town in the imperial province of Matlatzinco. The

picture tells us that both victims were dispatched before

100 RES 42 AUTUMN 2002

Figure 8. The Stone of Tizoc, probably initiated with the sacrifice of victims from the Matlatzinco area in 5 Tecpatl, 1484-1485. Museo Nacional de Antropolog?a, Mexico.

Photograph courtesy of the Instituto Nacional de Antropolog?a e Historia, Mexico.

the shrines were added, and seemingly the female was

killed before the male. The male figure actually stands

for a number of victims from the Matlatzinco area, while

the female may have been singular. Given that the

artificial mountain was an image of Coatepetl, it would

be logical to identify both figures as representatives of

Huitzilopochtli's enemies, who were defeated there. The

completion of the mountain base then was

commemorated with the sacrifice of atavars of the

enemy siblings, the female Coyolxauhqui and the male

Centzonhuitznahua', probably all represented by Matlatzinca captives.11

This evidence from the pictorial manuscript allows for

the dating of one well-known sculpture. Usually attributed to this temple phase, its initial use can now be

dated more specifically to the time of these sacrifices.

This is the Stone of Tizoc (fig. 8), a sacrificial platform

featuring a colossal image of the sun on its upper surface and conquered enemies grasped by Aztec victors

around the perimeter. Costume parts label the winners

11. Note the similarities between figures 2 and 6, although the one

who defeats Coyolxauhqui in figure 6 seems not to be Huitzilopochtli (in fact, recognizable deities are not represented in this part of the

historical section of Telleriano-Remensis).

as likeToltecs and the losers as like Chichimecs, while

the atl atls of the latter establish them as former nobility or rulers?that is, as former "Toltecs." Symbolically, Chichimecs were comparable to vassals and

commoners, while Toltecs were comparable to rulers

and nobles. The Aztec viewer would have seen the

conquered enemies also as like the mythical Cenzonhuitznahua', the defeated sibling-enemies of

Huitzilopochtli (see Umberger 1996a and in process).

Finally, since the featured conquest on the monument

pictures the ruler Tizoc, dressed as Huitzilopochtli and

identified by his name sign, taking a prisoner labeled as

from the Matlatzinco area (fig. 9), the Tizoc Stone must

have been created for the 5 Tecpatl sacrifice of the

Matlatzinca prisoners. The great greenstone

Coyolxauhqui Head, another sculpture generally

thought to have belonged to the same phase of the

temple (Pasztory 1983:153; Nicholson and Qui?ones 1983:48-51), could have been put in place at the same

time.12 So, as they completed the stages of each

enlargement of the Templo Mayor, the Aztecs seemingly

12. Alternatively, it may have been finished later, after the death of

Tizoc, as implied in a passage in Dur?n's history (1994:328). Its

particular date is not important to the argument of this article.

Umberger: Notions of Aztec history 101

Figure 9. The ruler Tizoc's conquest of the representative of the

Matlatzinco area, one of fifteen conquest scenes on the Stone of

Tizoc. Drawing by author.

installed sculptures corresponding to the actors and

actions in the myth. On Folio 39r, no action is pictured for the next year

date, 6 Calli (1485-1486), but in the following year, 7

Tochtli (1486-1487), Tizoc is depicted as having died

and been succeeded by his brother Ahuitzotl. Both are

seated on thrones. The scene under 8 Acatl (1487-1488) is the most complex in the historical section of the

codex. The completed temple is represented with the

shrines of Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli on top (reversed for some reason). Around it are scattered various

emblematic motifs. To the left of the temple the ruler

Ahuitzotl appears a second time on his throne. Below

the temple a symbol of the lighting of a "new fire" at the

structure is attached to the place glyph of Tenochtitlan.

Further below and to the right three sacrificial victims

(no doubt, conceived as other Centzonhuitznahua') are

labeled with hieroglyphs as from Xiuhcoac, Cuetlaxtlan, and possibly Tezapotitlan, three places in the eastern

part of the empire where Ahuitzotl had waged war

earlier in the year. At the bottom of the scene are the

hieroglyphs that give the total number of victims at the

dedication ceremony as 20,000 (Qui?ones 1995:225). The pyramid having already been initiated in Tizoc's

time, this ceremony actually celebrated the shrines, with

the completion of Huitzilopochtli's "house," no doubt

after that of the ancient earth and rain god Tlaloc.

I suggest that the motifs and form of the Tizoc Stone

indicate that this king, on commissioning it for the

sacrifice of prisoners from Matlatzinco, also anticipated its use in the ceremony at the completed temple several

years later. The Cr?nica X accounts of Duran and

Alvarado Tezozomoc assert that captives from all over

the empire were sacrificed at the temple dedication

(Carrasco 1999:419), and, asTownsend (1979:43-49) has pointed out, the stone is an ?mage of the empire in

cylindrical form. On it, each captive stands for a

conquered province, representing those that Tizoc

anticipated to be dispatched in the final ceremony

(Umberger 1998). The cosmic layout of the Tizoc Stone also echoes the

spatial diagram traced by the participants in the

ceremony described by Duran and Alvarado

Tezozomoc. Captives from the different provinces formed four lines along the causeways of the city and

converged at the center, to be sacrificed by Ahuitzotl, his prime minister Tlacaelel, and the kings of Texcoco

and Tlacopan, the other Triple Alliance members. The

Tizoc Stone represents a world divided into four

quarters, like the city itself, by the flinty teeth of the

102 RES 42 AUTUMN 2002

"earth monster" mouths on the band encircling the base

and by the large solar rays on the upper surface,

focusing on the sacrificial container at the center. Tizoc

then apparently planned for his great sacrificial stone to

be used in two major ceremonies.

The year 8 Acatl was an extremely important ceremonial year as a whole, and several lines of

evidence indicate that we should not read the vignettes under its sign in Codex Telleriano-Remensis as a unified

scene. Rather they mark different moments in the year. To reconstruct the sequence of events, we must

understand how Tizoc originally conceived of his temple

building. His predecessors had chosen dates of events

that could be interpreted according to solar metaphors to commemorate with their temple enlargements? calendar cycle beginnings, initiations of reigns, and

victories (Umberger 1987). Knowing the names of the

years that lay before him, Tizoc chose to begin his

enlargement in 4 Acatl because it was the anniversary of

the initiation of the Triple Alliance fifty-two years earlier

in 1431-1432, after the victory over the Tepanecs. This

was the alliance that eventually resulted in the empire, which was to be celebrated in the final ceremony.13 However, we know from many sources that the

dedication ceremonies were scheduled for the next

Acatl year, four years after 4 Acatl. Tizoc must have

planned this too. Since such a large structure could not

be completed within the year, he chose 8 Acatl because

its feast days followed the same sequence as those of 4

Acatl. In addition, 8 Acatl featured a better configuration of overlapping veintenas and trecenas leading to a

strong climax at the year's end. Finally, Tizoc knew that

the location of the day 4 Acatl in the middle of 8 Acatl established a close link between the two years. This then

would have been an acceptable type of postponement,

just as rituals were routinely delayed until propitious days. Most scholars writing on the 8 Acatl scene in

Telleriano-Remensis imply a single ceremony

incorporating all the acts of temple dedication pictured,

seemingly because of the survival of only one

commemorative plaque from the time. This monument,

dubbed the Dedication Stone (fig. 10), bears a large 8

Acatl date in a cartouche frame?the name of the year? below the named representations of the two kings who

built the temple. Carved like the Tizoc Stone and the

Coyolxauhqui Head from a dense polished stone and in

a similar style, it forms with them a plausible set of

contemporary monuments for the same temple phase. Like the other two, the Dedication Stone was not

attached to any archaeological phase, and its exact

original location remains unknown. In other words, it obviously pertained to the events of the year 8

Acatl, 1487-1488, but there is no evidence that it

commemorated the great public sacrifice, nor evidence

of an original location at the Templo Mayor. As seen in the description of the ceremony above, the

political activities of 7 Tochtli and 8 Acatl are detailed

most fully in Duran and Alvarado Tezozomoc's histories

(Duran 1994:chs. 41-44; Alvarado Tezozomoc 1980:

chs. 66-70). After Tizoc died and Ahuitzotl was elected

as his successor, the new king's coronation war was

waged against the province of Chiapa. The whole Aztec

world, including enemies, was invited to the public

ceremony on 1 Cipactli, but many invitees declined. The

ceremony included a feast and dancing for four days, followed by the sacrifice of prisoners on the "stone of the

sun"; the sacrifices wore priestly garments. The invited

lords left the city, having received extravagant gifts. Ahuitzotl then led the army against the Huastecs and

other provinces in the eastern part of the empire. Back

in Tenochtitlan the prisoners were made to eat earth in

front of Huitzilopochtli's image, were paraded around

the temple precinct, and distributed among the barrios

of the city. Ahuitzotl ordered artisans to complete the

temple and its sculptures, including "a sharp sacrificial

stone" and the image of Coyolxauhqui next to it.

Invitations to the dedication ceremony were sent to the

whole Aztec world, including the enemies who had

refused to come to Ahuitzotl's coronation. They

accepted this time. All visitors brought sacrificial

victims, who were lined up along the causeways and

counted. Ahuitzotl, sitting on his throne and flanked by the two allied kings, distributed tribute to the priests to

pay for the upcoming ceremonies and to the artisans to

make presents for the visiting lords. Ahuitzotl ordered

all the city's temples to be newly plastered, painted, and decorated.

The day before the festival, people from all over came

into the city in great crowds. At midnight of the feast

day the prisoners were (again) lined up on the four

causeways and moved to the center where they were

sacrificed by the three kings and Tlacaelel, helped by

priests wearing the garments of all the gods and

goddesses. The four primary sacrificers, in contrast, were

dressed in the Toltec-derived finery of rulers?the

turquoise crowns, turquoise-decorated capes, plus fine

loincloths and sandals that related them to the day sun

13. Archaeology reveals that this event, the rising of the Aztecs'

political "sun," had been commemorated in its own time with the

inscription of 4 Acatl on a plaque attached to Phase III of the temple

(Matos 1981:50; Umberger 1987).

Umberger: Notions of Aztec history 103

(as seen in fig. 1 and described in Alvarado Tezozomoc

1980:506-509). Ahuitzotl stood next to a sacrificial

stone called the tecatl, in front of the idol of

Huitzilopochtli, so that he could smear blood on the

god's mouth.14 The prime minister was at the "stone of

the sun," one would suppose the Tizoc Stone, but

whether this was on the temple platform or on its own

platform in front of the temple is unclear. The other

Triple Alliance kings were located at the sacrificial

stones of the Yopi Temple and the Huitznahuac Temple (ibid.:515-516).

The sacrificial ceremony lasted four days, and on the

fifth day Ahuitzotl gave gifts to the visiting kings, who then left. Festivities and diversions continued, and the

king distributed gifts to the soldiers, majordomos, officials, and priests, as well as the aged and poor of the

city. The old skull rack was destroyed, the skulls burned, and a new one was erected for the skulls of those

sacrificed in the temple dedication. The king gave gifts to all the artisans involved. The ceremonial period of the

temple dedication completed, Ahuitzotl moved on to the next war.

Obviously rolled into the events originally anticipated

by Tizoc were the activities of the new king who

replaced him midway through the temple expansion. In

Codex Telleriano-Remensis, Ahuitzotl is depicted on his

throne at the time of his accession and in the next year. This second throne scene emphasizes the temple dedication as the last in a longer-than-usual sequence of

coronation ceremonies, something that is reiterated by Alvarado Tezozomoc (ibid.:486, 488-490, 492).

Apparently, Ahuitzotl took offense on being snubbed by a significant number of foreign invitees to his original public accession event, and conceived the new temple dedication as an opportunity to demonstrate his power before them (Townsend 1979:40; Klein 1987:323). Since

captives from all provinces were sacrificed then and since only those taken by Ahuitzotl are pictured in

Telleriano-Remensis, these vignettes were meant

likewise to emphasize his participation. Tizoc had died prematurely under mysterious

circumstances. Duran says that members of the Aztec

court poisoned him; Torquemada (1969:1:184-185) says that foreign lords had him killed through sorcery; and

Ahuitzotl himself is named as a suspect in modern

literature (Hassig 1988:198-199). Whatever the original circumstances and the accuracy of recorded

interpretations, Ahuitzotl's commissioning of the image of the defunct ruler on the Dedication Stone indicates

that he conceived the temple expansion as a joint

project. Obviously, some changes were demanded after

Tizoc's death, but Ahuitzotl seems to have followed as

much as possible the earlier king's original program. The

rebuilding of the sacred mountain, after all, was in

imitation of an established royal activity, not merely Tizoc's whim (Umberger 1987).

Reconstruction of the ceremonial calendar of 8 Acatl, 1487-1488

Duran and Alvarado Tezozomoc give the general sequence, but the Telleriano-Remensis vignette,

monumental imagery, dates in alphabetical sources, and

moveable feast day associations provide the additional

evidence needed to reconstruct the day-by-day sequence and symbolic structures behind it (see fig. 5,

where black triangles point to important ceremonial

days). According to Chimalpahin (1965:220), on the

day 1 Miquiztli Ahuitzotl completed his war against Xiuhcoac, where he acquired one of the labeled

prisoners in the Telleriano-Remensis picture of the

temple inauguration. One Miquiztli was the beginning

day of Trecena 6, in this year falling within the veintena

that ended with the first occurrence of the year-bearer 8

Acatl. Both day-names recurred 260 days later during the highlighted month of the year, when the prisoners

were sacrificed at the Great Temple. So the warfare

event must have occurred in the earlier veintena, given the time needed to finish the conquest and return

with the prisoners to Tenochtitlan. The names of the

complementary, year-bearer months, when conquest and

sacrificial events occurred, "great vigil" and "stretching/

shrinking," may refer, respectively, to the anticipation of

the final ceremony and its realization as the year drew

to a close.

Chimalpahin (ibid.:220) also mentions a ceremony on

the day 4 Acatl, the feast day of Veintena IX in the

middle of the year. 4 Acatl, as a moveable feast day, was

the occasion of other public ceremonies of ruler

14. Alvarado Tezozomoc (1980:515) describes the tecatl as a

carved figure with twisted head, while Duran (1994:328) describes it as a sharp pointed stone next to the Coyolxauhqui image. I believe

that Alvarado Tezozomoc's text is confused, conflating this sacrificial

stone with another sculptural type, the chacmool (a reclining figure), which could well have been on the platform too, but not in front of

Huitzilopochtli's temple. The only platform that has survived at the

Templo Mayor excavations?Phase II of about 1390-1430?has a

chacmool in front of Tlaloc's shrine, while a plain upright stone,

presumably the tecatl, stands in front of Huitzilopochtli's shrine. It

seems more logical then to suppose that the tecatl was a plain stone in

front of Huitzilopochtli's temple and that the Coyolxauhqui head was

nearby.

104 RES 42 AUTUMN 2002

installation, besides those on 1 Cipactli, and it was

devoted to the fire god Xiuhtecuhtli (Sahag?n 1950 1982:bks. 4-5:88; Umberger 1981a:95-96). Chimalpahin, in fact, says that the ceremony was devoted to fire.

In the year 8 Acatl, this day's rituals must have

commemorated multiple additional events: the initiation

of the pyramid expansion in the year 4 Acatl four years earlier and the foundation of the Triple Alliance in the

year 4 Acatl, fifty-two years before that, as well as

Ahuitzotl's installation ceremony on a day 4 Acatl in the

previous year. As noted above, the day 4 Acatl, being at

the center of the year 8 Acatl, linked the two years

bracketing the temple construction.

The cleaning and refurbishing of the city's temples before the year's intensive ceremonial season, an act that

Duran mentions, would have occurred in Ochpaniztli. Two veintenas later 1 Tochtli commemorated the

initiation of the Fifth Era and began the 130-day period that encompassed the events of history leading up to the

triumph of the Aztecs, as well as the current events of

ruler accession and final temple dedication. In the

following veintena, a new Trecena Cycle began with 1

Cipactli, the date synonymous with calendrical

beginnings and ruler coronations. This particular 1

Cipactli was the anniversary of Ahuitzotl's coronation in

the previous year, and this aspect must have been

emphasized, given Ahuitzotl's conception of the temple dedication ceremonies as connected to his accession.

Thirteen days later was the anniversary of the

appearance of the Fifth Era's sun on 13 Acatl, the feast

day of Veintena XIV, at the end of primordial darkness.

Four days after that, 4 Ollin in the next veintena, the

anniversary of the sun's movement, would have featured

the sacrifice of the messenger to the sun at noon on one

of the city's sacrificial stones. The feast day of the same

month, 7 Acatl, initiated the twenty-day period dedicated to Quetzalcoatl. This period occupied the

following veintena and ended with 1 Acatl, another of

Quetzalcoatl's dates.

The association of Quetzalcoatl with this twenty-day

period is affirmed in the imagery of the Dedication

Stone. The Dedication Stone is unique among Aztec

monuments in its depiction of royal succession. On it, the dead Tizoc and the living Ahuitzotl, both wearing

Quetzalcoatl's priestly garb, stand below a small, unframed 7 Acatl glyph, the day that began the period, and draw blood from their ears. The streams that issue

flow into the mouth of the animated earth band, which, in turn, is above the large framed 8 Acatl glyph. Several

scholars have suggested that the monument thus

commemorated a royal bloodletting ceremony on the

day 7 Acatl in the year 8 Acatl. In this activity and the

royal costumes, Ahuitzotl (who performed it alone, since

Tizoc was dead) mimicked the example of Quetzalcoatl, who in Aztec lore was the first royal bloodletter

(Townsend 1979; Nicholson and Qui?ones 1983:54; Klein 1987; and Qui?ones 1979).15

I agree with this interpretation of the Dedication

Stone, but I disagree with the corollary idea put forth by these scholars?that the sacrifice of prisoners at the new

Templo Mayor took place on the same day (see also

Caso 1967:59; Tena 1987:87). Rather, the sacrifice of

prisoners, as the ceremonial climax of the ritual year, had to have been scheduled on the second year-bearing

day, 8 Acatl, forty days later. In addition to being the

year's primary feast day, 8 Acatl was at the end of the

veintena that contained the anniversary of the prisoners'

capture on 1 Miquiztli in the earlier year-bearing veintena. Thus, they would have been sacrificed soon

after this anniversary, linking the capture and sacrifice

events together. (Of course, the scheduling of these

events must be seen in reverse. Knowing that the

sacrifice was to occur on the second year-bearer day, 1

Miquiztli was chosen for the capture event because of

its occurrence in the year-bearer veintenas.) But why was 1 Miquiztli chosen for the capture

event, instead of 8 Acatl, which would have formed a

perfect symmetry? One Miquiztli was an obvious choice

because of its symbolic connection with Tezcatlipoca.

According to Sahag?n (1950-1982:bks. 4-5:33-36), on

1 Miquiztli, Tezcatlipoca, as lord of darkness, "went

withdrawing rule and power from others." On this day, he was characterized as lord of fate and arbitrariness,

who overturned the fortunes of those who did not

worship him properly, making the formerly rich into

slaves (slaves, in turn, being vulnerable to sacrifice). One Miquiztli then was a very appropriate day for

taking sacrificial captives, especially former rulers

brought low by defeat, like those represented on the

Tizoc Stone (and Quetzalcoatl before them). Sahag?n's

passages do not mention that Tezcatlipoca achieved this

through warfare, but that is the implication. Tizoc and his priests anticipated and planned the

ceremonial events of 8 Acatl, including the use of the

Tizoc Stone for the sacrifice of prisoners, as maintained

above. As in the case of the Dedication Stone, the

imagery of this monument both supports its association

15. Quetzalcoatl was named 1 Acatl, a date that serves as his

name on several sculptures. The same relative location of 7 Acatl near