Tourism and World Cup football amidst perceptions of risk: the case of South Africa

Transcript of Tourism and World Cup football amidst perceptions of risk: the case of South Africa

This article was downloaded by: [KSU Kent State University], [Andrew Lepp]On: 22 September 2011, At: 06:11Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: MortimerHouse, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and TourismPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/sjht20

Tourism and World Cup Football amidst Perceptionsof Risk: The Case of South AfricaAndrew Lepp a & Heather Gibson ba Kent State University, Ohiob University of Florida, USA

Available online: 22 Sep 2011

To cite this article: Andrew Lepp & Heather Gibson (2011): Tourism and World Cup Football amidst Perceptions of Risk:The Case of South Africa, Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11:3, 286-305

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2011.593361

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematicreproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form toanyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contentswill be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses shouldbe independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims,proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly inconnection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Tourism and World Cup Football amidstPerceptions of Risk: The Case ofSouth Africa

ANDREW LEPP* & HEATHER GIBSON**

*Kent State University, Ohio, and **University of Florida, USA

ABSTRACT Africa is generally perceived by those living outside the continent as a riskydestination for tourism. Many factors influence this perception, some real and someimagined. South Africa is the continent’s leading international tourism destination and tomaintain this industry it must manage perceptions of travel-related risk which can negativelyinfluence destination choice. Towards this end, South Africa has pursued and hosted avariety of sporting mega events including the Rugby and Cricket World Cups and the 2010FIFA World Cup with the aim of “reimaging through sport”. The purpose of this study wasto investigate the influence of the FIFA World Cup on the perception of risk associated withtravel to South Africa, knowledge of South Africa, perceived level of development, interest intraveling to South Africa, and related travel motivations and constraints. A repeatedmeasures design was used whereby a paired sample of US college students was surveyedbefore and after the FIFA World Cup. The post-test also measured level of involvement withthe World Cup as fans. Results suggest the World Cup did influence perceptions of SouthAfrica. The discussion furthers our understanding of tourism development and promotion inareas of the world perceived as risky.

KEY WORDS: Perceived risk, travel motivations, FIFA World Cup, sport mega events, Africa

Introduction

The continent of Africa is generally perceived as a risky destination for tourism. Lepp

and Gibson (2008) found that only the Middle East is perceived as riskier. Researchers

have identified a variety of risks tourists commonly associate with Africa, including

political and social instability, poor governance, war, terrorism, crime, disease,

unfriendly hosts, cultural and language barriers, primitive conditions, and economic

concerns such as currency instability (Ankomah & Crompton, 1990; Brown, 2000;

Carter, 1998; Sonmez & Graefe, 1998a; Teye, 1988). These perceptions persist

despite the fact that prospective tourists have admitted to knowing little or nothing

Correspondence Address: Andrew Lepp, Recreation, Park and Tourism Management, Kent State Univer-

sity, PO Box 5190, Kent, OH 44242, USA. Tel: + 1 330 672 0218. Fax: + 1 330 672 4106. E-mail:

Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism,

Vol. 11, No. 3, 286–305, October 2011

1502-2250 Print/1502-2269 Online/11/030286–20 # 2011 Taylor & Francis

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2011.593361

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

about Africa (Lepp, Gibson, & Lane, 2011). Unfortunately, as Keim (1999) points out,

this lack of knowledge about Africa typically leads individuals to rely on stereotypes

and broad generalizations. In tourism, this contributes to what Enders, Sandler and

Parise (1992) termed the generalization effect, or in other words, the tendency of tour-

ists to make broad generalizations about diverse regions. With Africa, this tendency is

common. For example, participants in a study by Carter (1998) described Africa as

“a single undifferentiated territory that was dangerous” for travel (p. 354). Similarly,

Lawson and Thyne (2001) found perceptions of travel-related risk were applied gener-

ally across the whole African continent with no recognition of regional variability.

Lastly, Mathers (2004) found Africa is imagined in the US as a homogenous landscape

of primitive nature, poverty, disease, and violence.

Of the many politically stable democracies in Africa vying for tourists, South Africa

is perhaps most burdened by many of the risk factors which tourists tend to generalize

across the continent (Altbeker, 2005). Since the end of apartheid in 1994, South Africa

has continually ranked among the world’s most dangerous nations in terms of violent

crime (Kynoch, 2005). For example, South Africa’s murder rate in 2008 was 36.5 per

100,000 people. By comparison, the murder rate in Kenya was 3.6, the United States’

was 5.2, and Sweden’s was 0.9 (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2010). In

terms of common infectious diseases like HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis, South Africa’s

rate of infection in the adult population according to the international HIV/AIDScharity AVERT, is two to three times greater than most other African nations

(AVERT, 2010). Ironically, South Africa is the continent’s leading destination for

international tourists and the country’s tourism industry is growing rapidly (WTO,

2009). Simultaneously, the “grandfather” of African tourism, Kenya, is experiencing

a decline. The reason, as proffered by Kenyan tourism researchers Akama and Kieti

(2003), is the increasing perception that Kenya is a risky destination.

The other side of this story is that South Africa’s independence in 1994 and the elec-

tion of President NelsonMandela remains one of the most inspiring and uplifting events

of the 20th century. The significance of Mandela’s presidency and his diplomacy on the

international stage greatly reduced the stigma associated with South Africa following

the apartheid period. In addition to his political abilities and charisma, Mandela cun-

ningly evoked the power of sporting mega-events for his country’s advantage. Initially,

this was to unite the country’s blacks and whites, as inspiringly told in the movie Invic-

tus and reported in the academic literature (Van Der Merwe, 2007). However, there

were many purposes of this sports-based strategy including improving South

Africa’s global image and boosting the nation’s tourism industry (Cornelissen, 2004;

2008, Ndlovu, 2010; Swart & Bob, 2007; Van Der Merwe, 2007). Since 1994,

South Africa has hosted the Rugby World Cup, the Cricket World Cup, and in 2010

the FIFA World Cup. Among sporting mega-events, the FIFA World Cup and the

Olympic Games are the most prized. These two events, more than any others,

capture the world’s attention (Cornelissen, 2008). Around the world, an estimated

700 million tuned in for South Africa’s 2010 World Cup (Wyatt, 2010). In the US,

the 2010 World Cup final between the Netherlands and Spain was the most watched

“soccer” match in US history with 24.3 million viewers (Nielsen, 2010a). Over the

course of the month-long tournament, it is estimated that 112 million US viewers

tuned in for at least part of a match (Nielsen, 2010b). In addition, billions of minutes

Tourism and World Cup Football 287

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

were spent following the 2010 World Cup through various digital media such as inter-

net websites and mobile apps (Gorman, 2010). As Mandela recognized, the tremendous

amount of positive media exposure created by sporting mega events has the potential to

re-position a country in the global tourism market and stimulate interest in visiting it

(Cornelissen, 2004, 2008).

For South Africa, this goal may be complicated by the perception of risk which tour-

ists tend to generalize across the African continent. Indeed, in the months leading up to

the 2010 FIFA World Cup, the western media was filled with stories about risks to vis-

iting fans from crime and terrorism (Bly, 2010). Indeed, Bleby (2010) an Australian

journalist suggested that “Crime is perhaps South Africa’s best-known brand after

Nelson Mandela” in an article entitled “No need to pack your flak jacket” after

the German team was advised to wear bullet proof vests. Considering all of this, the

purpose of this paper was to investigate the influence of the 2010 World Cup on the

perception of risk associated with travel to South Africa, interest in visiting South

Africa, and the related motivations or constraints. The study utilized a repeated

measures design whereby a paired sample of college students was surveyed before

and after the World Cup. The post-test also included various measures of respondents’

level of involvement with the World Cup. The current study aims at increasing our

understanding of tourism development and promotion in areas of the world perceived

as risky.

Background

Many factors contribute to the perception of risks associated with tourism (Roehl &

Fesenmaier, 1992). A recent survey by Simpson and Siguaw (2008) asked over

2,000 respondents to “think about your last trip to any location” and list the “risks

you considered before deciding to go” (p. 319). Their survey yielded 3,449 responses

which were grouped into categories. Although there could be some reasonable debate

over whether a “trip” is synonymous with tourism, their results are suggestive of the

breadth of risk factors tourists consider. Risks related to: health and well being; criminal

harm (muggings, assaults, terrorism, etc.); transportation (automotive breakdowns,

etc); service providers (inadequate lodging, etc.); the environment (weather, road con-

ditions, etc.); financial concerns (losing money, poor value for money, etc.); and social

factors (racism, poor treatment, unfriendly people, etc.) were listed. In the growing

body of research addressing perceived risk and international tourism, a similar list of

risk factors has come to dominate the discussion. These factors include terrorism,

war, political instability, crime, disease and other health concerns, and cultural differ-

ences (e.g. Brunt, Mawby, & Hambly, 2000; Carter, 1998; Cossens & Gin, 1994;

Gartner & Shen, 1992; Hollier, 1991; Lepp & Gibson, 2003; Reisinger & Mavondo,

2005; Sonmez & Graefe, 1998a,b). What these factors have in common is the percep-

tion they may cause physical or financial loss for a tourist. As suggested by Larsen,

Brun and Øgaard (2009), the prominence of these factors in the mind of the tourist

is due partly to their salience in the global media, particularly after the terrorist

attacks of 9/11.On the continent of Africa, tourists perceive these risk factors to exist in abundance

(Ankomah & Crompton, 1990; Brown, 2000; Carter, 1998; Lawson & Thyne, 2001;

288 A. Lepp & H. Gibson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

Sonmez & Graefe, 1998a; Teye, 1988). In a recent study by Lepp, Gibson and Lane

(2011), 20 risk factors identified in the literature as being associated with tourism in

Africa were examined. Using principal components analysis five underlying factors

were identified which begin to explain the risk tourists associate with travel to

Africa. The first factor was labeled “attributes of modern countries.” This factor

included items such as a stable economy, good governance, healthy people, good

health care facilities and political stability. In Africa, these attributes are perceived to

be in limited supply and thus, the continent is perceived as risky. The second factor

was labeled “attributes of primitive Africa.” This factor included dangerous wildlife,

primitive people, jungle and disease. These attributes are perceived to be abundant in

Africa and thus contribute to its risky image. The third factor was labeled “cultural

differences and barriers.” This included strange cultures, strange food and communi-

cation barriers. These attributes are also perceived to be common in Africa. The

fourth factor was labeled “violence, war and crime” and included terrorism, rebel

groups, kidnapping and other serious crimes. These attributes were perceived to

affect tourism in Africa more so than other regions of the world. The final factor was

labeled “interpersonal.” This included items related to interpersonal contact, such as

the risk that Africans would not be friendly or welcoming. The significance of these

factors is that they can be managed in order to reduce perceived risk. Indeed, Lepp

et al. demonstrated that the official tourism websites of African nations can be used

to reduce perceived risk by addressing these five factors. Perhaps, in the case of

South Africa, hosting sporting mega events might have the same effect. Certainly

Smith (2005) alludes to the possibility of “reimaging” a country through sport.

Ultimately, tourism managers strive to reduce perceived risk because of its impact on

travel decisions. Simply put, destinations perceived as risky are less likely to be visited

(Sirakaya, Sheppard, & McLellan, 1997; Sonmez & Graefe 1998a). Delving further

into this relationship, Reisinger and Mavondo (2005) found perceived risk to be associ-

ated with travel anxiety which in turn was negatively associated with intention to travel.

Similarly, Quintal, Lee, and Soutar (2010) found perceived risk has a negative influence

on attitudes towards travel. Furthermore, they found in some cases that negative atti-

tudes towards travel as a result of perceived risk reduce an individual’s travel inten-

tions. In a related line of research, Larsen et al. (2009) investigated tourist worries.

Tourist worry is the negative cognitive and emotional affect induced by the uncertainty

of future events. Their results showed that tourist worry is positively correlated with

subjective risk perception and negatively correlated with desire to travel. Interestingly,

in their study of tourists on vacation in Norway, they found that tourists did not worry

much. However, the authors suggested that this could be a function of the perceived

safety associated with travel in Norway and that results could be different for tourists

visiting destinations perceived to be risky.

The negative relationship between perceived risk and intent to travel is not surpris-

ing. However, tourists are not a homogenous group and individuals may react to per-

ceived risk differently. Kozak, Crotts, and Law (2007) found that while the majority

of their respondents (83.8%) would change travel plans as a result of increased risk

at their destination a sizeable minority (16.2%) would not. Respondents likely to

travel in the face of increased risk were older males with previous international

travel experience. Lepp and Gibson (2003) also found that perception of risk can

Tourism and World Cup Football 289

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

vary by gender, previous travel experience and tourist role. Regarding tourist role,

novelty seeking tourists such as Cohen’s (1972) Explorers and Drifters perceived

less risk related to international travel than those roles with a preference for familiarity

such as Organized Mass Tourists and Independent Mass Tourists. Pondering this

further, Lepp and Gibson suggested the perception of risk may sometimes attract

novelty-seeking tourists while most often repelling tourists with a preference for fam-

iliarity. This hypothesis was supported in later research when Lepp and Gibson (2008)

found that novelty seekers were attracted to riskier destinations and indeed were more

likely to have previously traveled to destinations perceived as risky. In a study of US

soccer club members and their interest in travel to the 2002 FIFAWorld Cup, Kim, and

Chalip (2004) conceptualized risk as a constraint on travel in terms of threats to health

and safety. They found that respondents who had attended previous World Cups per-

ceived less risk associated with the event than first time attendees. Although for the

same event, Toohey, Taylor, and Lee (2003) found that threat of terrorism did deter

some potential fans from attending. Thus, risk may be perceived differently by individ-

uals and potentially may be a motive for some and a constraint for others.

Pursuing this further, Lepp, Gibson, and Lane (2010, 2011) surveyed 286 under-

graduate students about the perceptions of risk associated with travel to Uganda, inter-

est in traveling there, and why a person might be interested or not interested in traveling

there. In addition, the authors investigated whether exposure to Uganda’s official

tourism website would influence the aforementioned variables. Results show that

regardless of preference for novelty, respondents perceived Uganda as a risky destina-

tion. However, 59% of novelty seekers were initially interested in traveling to Uganda,

while only 41% of those with a preference for familiarity were initially interested. Thus,

tourist role was a significant variable in predicting interest, interestingly, gender was

not. Respondents then listed their top two reasons explaining their interest (motiv-

ations) or lack of interest (constraints) for traveling to Uganda. The dominant constraint

was the perception that Uganda is not safe. After exposure to Uganda’s official tourism

website, interest in traveling to Uganda significantly increased, even among those with

a preference for familiarity. Importantly, the increase in interest corresponded to a

decrease in the perception that Uganda was not safe. Results seem to indicate that per-

ception of risk can be a significant constraint to travel, particularly among those with a

preference for familiarity like Cohen’s (1972) organized and independent mass tourists.

Furthermore, tourism managers can proactively manage this constraint and reduce it

with a well designed website.

Concerning motivations for travel to Uganda, results of the study suggest they are

relatively stable (Lepp et al., 2010). The four most frequent pre-test motivations

were the same for each tourist role and for males and females. These common motiv-

ations were: an interest in learning about Uganda, an interest in Uganda’s culture, an

interest in new experiences (novelty), and a general interest in travel. These four

themes accounted for nearly 80% of all motivations reported. After exposure to

Uganda’s official tourism website, these four motivations remained dominant, account-

ing for nearly 70% of all motivations reported. However, a few new motivations were

generated, namely: the desire to see wildlife, the belief that Uganda is tourist friendly,

and Uganda’s scenic beauty. With the exception of “a general interest in travel,” these

motivations would be considered pull factors meaning that they were aroused by the

290 A. Lepp & H. Gibson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

destination itself. Indeed, in one of the seminal papers on tourist motivations Crompton

(1979) noted that pull factors are easier for respondents to articulate than push factors.

Push factors are socio-psychological factors which motivate a person to travel such as

the need to escape from a perceived mundane environment, the need for relaxation, or

the need for prestige. Therefore, when asking respondents to consider a hypothetical

future tour of Uganda, it should not be surprising that destination specific pull

factors dominate. In Crompton’s study, two primary pull factors emerged: novelty

and opportunities for learning.

Since this early research by Crompton, tourist motivation has proven to be an active

line of inquiry. Yet, very few researchers have investigated motivations for travel to

African nations (Beh & Bruyere, 2007). However, the existing research suggests des-

tination specific pull factors are very important. Awaritefe (2003) investigated tourists

in Nigeria and found an interest in nature, culture and history to be important motives,

in addition, concerns over safety and security were identified as constraints. In a second

study, Awaritefe (2008) compared foreign tourists in Nigeria with domestic tourists in

terms of their motivations and found significant differences. While the domestic tourists

seemed motivated by push factors such as need for relaxation, foreign tourists were

motivated by environmental learning and adventure (novelty). Beh and Bruyere sur-

veyed 465 tourists in Kenya and found eight significant motivations: escape, learning

about culture, personal growth, seeing wildlife, adventure (novelty), general learning,

learning about nature, and general site seeing. Again, as suggested by Crompton

(1979), the majority of these are pull factors aroused by the destination itself. Similarly,

Barros, Butler and Correia (2008) surveyed Portuguese tourists traveling to “sun and

sand” type resorts in North Africa. Their analysis revealed culture and climate to be sig-

nificant motives while perceived exoticness of the destination was a constraint. Also,

results showed that previous exposure to travel brochures and destination-related tele-

vision spots had a positive influence on motivation. Finally, Kruger and Saayman

(2010) surveyed tourists visiting two national parks in South Africa. Their sample con-

tained mostly domestic tourists who had visited the parks several times previously.

Primary motivations were escape and relaxation, nostalgia and knowledge seeking.

Thus, in support of Awaritefe (2008), it appears that domestic tourists in Africa have

a slightly different set of motivations than foreign tourists with more emphasis

placed on relaxation. Overall, foreign tourists in Africa appear motivated by destina-

tion-induced pull factors such as culture, nature, opportunities for learning, and

novelty. An interesting question is whether these will differ for South Africa because

of its increasing involvement with sporting mega-events, exposure to which could

potentially arouse new motivations.

South Africa has aggressively and successfully pursued the hosting of sporting mega-

events (VanDerMerwe, 2007). One of the reasons for this strategy has been the quest for

tourism-related benefits. For example, as part of the preparation for hosting amega event

infrastructure vital for tourism such as airports, roads and hotels are developed or

upgraded (Hiller, 2000). In the short-term, the mega-event itself attracts tourists to the

host country. In South Africa for example, over half a million tourists are confirmed

to have entered the country to participate in the World Cup (South Africa, 2010a).

Hosting mega-events is also associated with short-term economic benefits (Cornelissen,

2004). In South Africa, it has been estimated that theWorld Cup had a 13.4 billion dollar

Tourism and World Cup Football 291

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

(US) gross economic impact (South Africa, 2010a). Considering long-term benefits,

researchers have identified a positive influence on destination image, improved destina-

tion marketing and promotion, increased investment in the tourism industry, and

increased international tourist flows (Cornelissen, 2004; Florek, Breitbarth, & Conejo,

2008; Smith, 2005). Already, South Africa’s image may be improving as a result of

the World Cup. As the CEO of South African Tourism said of the event, “The World

Cup has been fantastic exposure for South Africa. The World Cup has afforded South

Africa the opportunity to do away with stereotypes. Overall, the response from visitors

has been one of surprise. Surprise at our level of infrastructure development” (South

Africa, 2010b). Finally, some commentators have explained South Africa’s hosting of

the 2010 World Cup as an attempt to use the symbolism of football as a multicultural

and global phenomenon to represent the “new South Africa” which desires to be seen

as a multi-racial, inclusive, African democracy and a rightful and legitimate player on

the world’s stage (Cornelissen, 2008; Ndlovu, 2010; Van Der Merwe, 2007).

In summary, Africa is perceived to be a risky destination for international travel

(Lepp & Gibson, 2008). This perception tends to be generalized across the continent

(Carter, 1998; Lawson & Thyne, 2001). One factor contributing to this perception is

the belief that important elements of modern societies are missing from Africa while

elements of primitive societies are abundant (Lepp et al., 2011). While this may

attract some novelty-seeking tourists, it acts mostly as a constraint. Fortunately for

African nations, this perception can be changed by providing contrary information

through a trustworthy source, such as television or a tourism website (Gartner, 1993;

Lepp et al., 2011). This is a major reason for South Africa’s involvement with sporting

mega-events (Cornelissen, 2004, 2008; Van Der Merwe, 2007). By successfully

hosting an event like the FIFA World Cup, South Africa testifies to its modernity in

front of 100’s of millions of people from around the world. Certainly, Chalip, Green,

and Hill (2003) found that event telecasts that contain images of the destination can

influence perceptions and travel intentions, particularly among individuals who have

less knowledge about a country. Thus, ideally, media coverage of the FIFA World

Cup would reduce perceived risk and increase interest in visiting the country, particu-

larly among US residents whose knowledge of South Africa may be limited. With this

in mind, this study asked the following questions: (1) Did the World Cup affect per-

ceived knowledge of South Africa? (2) Did the World Cup affect the perceived level

of South Africa’s development? (3) Did the World Cup affect perceived risk associated

with travel to South Africa? (4) Did the World Cup affect interest in travel to South

Africa? (5) What are the primary motivations and constraints affecting interest in

travel to South Africa and were they affected by the World Cup?, and finally (6) if

effects are identified, do they vary by (a) time spent watching the world cup, (b)

gender, or (c) preference for novelty or familiarity in travel?

Method

Data Collection

Pre-test data were collected during April of 2010, 2 months before the start of the FIFA

World Cup, at a large public US university. Respondents were recruited in the

292 A. Lepp & H. Gibson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

classroom and given 10 minutes at the start of class to complete the survey. Although

no incentive was given, nearly all students participated. Students were in one of three

majors: Exercise Science, Physical Education, and Sport Administration. It was felt that

students in sport-related majors would be more likely to follow the World Cup. Since

the purpose was to explore whether following the World Cup influences perceptions of

South Africa and interest in traveling there, this was a logical population to study. In all,

284 students completed the pre-test. The pre-test consisted of a self-administered ques-

tionnaire measuring perceived knowledge of South Africa, perceived level of South

Africa’s development, perceived risk associated with travel to South Africa, interest

in traveling to South Africa, motivations and constraints. Perceived knowledge was

measured with a single item which read “Would you say that you know: (a) a lot

about South Africa, (b) a little bit about South Africa, (c) nothing about South

Africa.” Perceived level of development was measured with a single item which read

“Compared to other countries in Africa, South Africa is: (a) less developed, (b)

equally developed, (c) more developed.” Perceived risk was measured with a single

item which read “How would you rate the overall degree of risk associated with travel-

ing to South Africa: (a) very risky, (b) risky, (c) neither risky nor safe, (d) safe, (e) very

safe.” Interest in traveling to South Africa was measured with the following “yes or no”

question: “Assuming time and money are not concerns, would you travel to South

Africa for a two week tour of the country?” This was immediately followed with an

open ended request to “please list the two most important reasons explaining your

answer above, i.e. why you would or would not travel to South Africa.” The two

most common constraints to international travel, time and money (Nyaupane & Ander-

eck, 2008; Pennington-Gray & Kerstetter, 2002), were controlled for with this question.

This was done to encourage a deeper reflection on travel to South Africa and allow for

the possible emergence of socio-psychological constraints which research suggests may

be more influential in determining interest (Crawford, Jackson, & Godbey 1991; Hong,

Kim, Jang, & Lee, 2006; Hung & Petrick, 2010). In addition, the questionnaire categor-

ized respondents by preference for novelty or familiarity as operationalized by Lepp

and Gibson (2003). Accordingly, four statements were presented to respondents,

each describing the behaviors of one of Cohen’s four tourist roles. Respondents were

asked to choose the one which best described their travel characteristics. Finally,

basic demographics and students’ email addresses were collected. Email addresses

were used to administer an online post-test after the World Cup.

Three weeks after the conclusion of the World Cup, students who had completed the

pre-test were contacted by email and invited to participate in an online post-test. An

online survey was used because students were away from school on summer break.

The post-test contained the same items as the pre-test minus the demographics. In

addition, the post-test measured interest in the World Cup, the number of games

watched, hours spent following the tournament, and satisfaction with the hosting of

the event. Of the 284 pre-tests completed, 38 had illegible or otherwise non-useable

email addresses, thus 246 invitations were emailed. Three reminders were emailed

over the next 3 weeks. By the close of the survey, 95 students had participated.

After eliminating incomplete surveys, 79 remained for a 32% response rate. Only the

79 students who completed both the pre-test and the post-test were used for this

study. This allowed for the comparison of pre and post test results. If differences

Tourism and World Cup Football 293

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

were found between pre- and post-test data then the researchers assumed the massive

publicity generated by the World Cup for South Africa was partly responsible.

However, there is no way to test this assumption. Other variables not measured with

this study, such as political events in the news or popular Hollywood movies like Invic-

tus, could also have acted upon respondents between the pre and post tests and thereby

effected change. This is a limitation of the study. An experimental design with a ran-

domized control group which had zero exposure to the World Cup would have been

ideal. However, such a design would have been impossible owing to the duration of

the tournament, its popularity, and the ubiquitous media coverage associated with it.

Data Analysis

SPSS nonparametric tests (binomial for variables with two categories, chi square for

variables with three or more categories) were used to determine whether significant

differences exist between the 79 students who completed both surveys and the original

sample of 284 students. Every categorical variable on the pre-test was analyzed and no

significant differences were found except gender. The original sample of 284 students

was 35% female, the sample of 79 used for this study was 46% female (asymp. sig. ¼

0.034). For the pre-test versus post-test comparison, quantitative data were analyzed

with SPSS using frequencies, Wilcoxon sign rank test, non-parametric binomial

tests, and chi square. Open-ended responses (motivations and constraints) were ana-

lyzed by categorizing similar responses into single themes. Responses were simple

phrases and thus were clear in meaning. For example, the motivational theme

“culture” included the following responses: experience a different culture, see a new

culture, learn about a new culture, discover an interesting culture, South Africa has

an interesting culture, and so on. The categorization strategies and themes developed

during the pre-test analysis were applied to the post-test analysis ensuring internal

reliability and consistency. Such analyses are assumed reliable when undertaken by a

single well trained researcher as was the case here (Kirk & Miller, 1986). After all

the data had been categorized, the frequencies of pre- and post-test themes were

compared.

Participants

Of the 79 students who participated in this study, 43 (54%) were male and 36 (46%)

female. In terms of travel styles and preferences, 37 (47%) were novelty seekers and

41 (52%) preferred familiarity. Turning to the World Cup, interest was moderately

high: 46 (58.2%) were either interested or highly interested, 17 (21.5%) were

neutral, 16 (20%) were not interested. This translated in to a range of games being

watched. Twenty four (30%) students watched between 11 and 64 games, 38 (48%)

watched between two and 10 games, two (2.5%) only watched one game, and 15

(19%) did not watch any games. As a result, 70 (88.6%) students were aware that

the 2010 World Cup was held in South Africa and 70 (88.6%) felt South Africa did

a good or very good job at hosting the event. This preliminary look at the data indicates

that these students were involved with the World Cup as fans. The question now

294 A. Lepp & H. Gibson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

becomes, might the World Cup have influenced these students’ perceptions of South

Africa as well as interest in traveling there?

Results

Pre- and post-test results were compared for the pertinent categorical variables using chi

square tests and the results are displayed in Table 1. Regarding perceived knowledge, 3

weeks after the conclusion of the World Cup, students felt more knowledgeable about

South Africa (x2 ¼ 10.05, p ¼ 0.007). Although very few students felt they knew a lot

about South Africa, the post test shows a significant number had shifted from the “know

nothing” category to the “know a little” category. Regarding perceived level of devel-

opment, 3 weeks after the conclusion of the World Cup students perceived South Africa

to be slightly less developed than they did before the World Cup (x2 ¼ 13.21, p ¼

0.001). Before the World Cup, 63.3% of the students perceived South Africa to be

more developed than other countries in Africa. After the World Cup, only 48.1% of

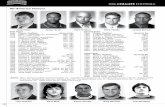

Table 1. Pre- and post-test perceptions of South Africa.

Variable Category N

Pre test Post test

df chi sq pFreq % Freq %

Perceived knowledge of SA 79 2 10.05 0.007∗

A lot 4 5.1 2 2.5

A little bit 42 53.2 56 70.9

Nothing 33 41.8 21 26.6

Total 79 100.0 79 100.0

Perceived level of development 79 2 13.21 0.001∗

Less developed 15 19 15 19

Equally developed 14 17.7 26 32.9

More developed 50 63.3 38 48.1

Total 79 100.0 79 100.0

Perceived risk in traveling to SA 79 3 2.518 0.472

Very risky 0 0 0 0

Risky 31 39.2 29 36.7

Neither risky nor safe 28 35.4 31 39.2

Safe 19 24.4 17 21.5

Very safe 0 0 2 2.5

No response 1 1.3 0 0

Total 79 100.0 79 100.0

Interest in traveling to SA 79 1 0.000 0.994

Yes 71 89.9 71 89.9

No 8 10.1 8 10.1

Total 79 100.0 79 100.0

Tourism and World Cup Football 295

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

students perceived South Africa to be more developed than other countries in Africa.

The remainder of students perceived South Africa to be equally developed or less

developed in comparison with other African countries. This is the opposite of South

Africa’s desired effect (Van Der Merwe, 2007). The third variable in the table is per-

ceived risk associated with travel to South Africa. In the pre-test, 39.2% of students per-

ceived South Africa as a risky destination, 35.4% were risk neutral, and 24.4%

perceived it as safe. Interestingly, no students perceived South Africa as very risky

or very safe. In previous research, the mean response to this same 5-point scale has

been used to assess the collective perceived risk a sample of respondents attaches to

a destination (Lepp & Gibson, 2008). Because 3.0 is neutral and the midpoint of the

scale, a mean greater than 3.0 indicates some degree of collective perceived risk. In

this study, the mean pre-test response was 3.15 and is similar to Lepp and Gibson’s

(2008) earlier use of the same scale with a larger sample to rate the degree of risk associ-

ated with travel to Africa where the mean response was 3.28. Interestingly, after the

World Cup perceived risk remained the same (x2 ¼ 2.518, p ¼ 0.472). The post-test

responses were nearly identical to the pre-test responses. The final variable in

Table 1 is interest in traveling to South Africa. Results show a high interest in traveling

to South Africa. In the pre-test, 90% of the respondents reported an interest in travelling

to South Africa. After the World Cup, 90% again expressed interest in such travel.

In this study, respondents who reported an interest in traveling to South Africa were

asked to provide two reasons for their interest. In both the pre-test and post-test, this

produced a list of 142 responses describing potential motivations for travel to South

Africa. In the pre-test, four primary motivations emerged. These were culture, learning,

novelty and enjoyment (Table 2). Cumulatively, these four motivations accounted for

69.7% of all pre-test responses. Several minor motivations emerged, these were: nature,

the idea of “always wanting to visit Africa,” the World Cup, the idea that “South Africa

is the most developed part of Africa,” and the idea of “always wanting to visit South

Africa.” After the World Cup, the post-test revealed novelty, culture, enjoyment and

learning remained dominant (Table 2). Together they accounted for 66.9% of all

responses. In addition to these four, nature emerged as a more important motivation

in the post-test, as 18 respondents commented on this motivation at post-test measure-

ment, compared to 10 respondents during the pre test. Among the minor motivations, it

is worth noting that “South Africa is tourist friendly” increased slightly (from 2 to 6

responses) after the tournament.

Turning to constraints, respondents who reported no interest in traveling to South

Africa were asked to provide two reasons for their lack of interest. Since there was

very little lack of interest, this only produced a list of 16 items. In the pre-test, the

primary constraint was the perception that South Africa is not safe. This was mentioned

five times. The other constraints were a lack of knowledge about South Africa, no inter-

est in traveling there, the idea that better destinations exist elsewhere, and the comment

that it is “not a tourist spot” (Table 3). After the World Cup, post-test results show the

perception that South Africa is not safe was only mentioned once. Lack of knowledge

as a constraint was mentioned just once as well. At the same time, the constraints “no

interest” and “better places” were mentioned more frequently.

Lastly, the analysis considered whether any change which may have occurred

between pre- and post-test responses was influenced by the following: (1) time spent

296 A. Lepp & H. Gibson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

watching the World Cup, (2) gender, and (3) tourist role. Differences in pre- and post-

test responses were categorized by each of these three variables. Quantitative data were

compared using the Wilcoxon signed ranks test. Open-ended responses were simply

divided among the categories of interest and frequencies were used for comparison.

Firstly, respondents were divided into three categories of equal size based on the

amount of time they spent watching the World Cup: low (0–3 hours), medium (4–

13 hours), high (15 or more hours). Differences between pre- and post-test responses

were independent of the amount of hours spent watching the tournament except for per-

ceived level of South Africa’s development. For the sample as a whole, respondents

perceived South Africa to be less developed after the World Cup than before the

World Cup. This effect was greatest among those who spent the most time watching

Table 3. Constraints associated with travel to South Africa (N ¼ 16).

Pre test Freq. Post test Freq.

Not safe 5 No interest 8

No response 3 Better places 6

Know nothing about it 3 Know nothing about it 1

No interest 3 Not safe 1

Better places 1

Not a tourist spot 1

Table 2. Motivations associated with travel to South Africa (N ¼ 142).

Pre test Freq. % Cum. % Post test Freq. % Cum. %

Culture 37 26.1 26.1 Novelty 30 21.1 21.1

Learning 23 16.2 42.3 Culture 29 20.4 41.5

Novelty 20 14.1 56.3 Enjoy travel 19 13.4 54.9

Enjoy travel 19 13.4 69.7 Nature 18 12.7 67.6

Nature 10 7.0 76.8 Learning 17 12.0 79.6

Africa 9 6.3 83.1 Tourist friendly 6 4.2 83.8

Sport: World Cup 5 3.5 86.6 Africa 5 3.5 87.3

Developed Africa 4 2.8 89.4 South Africa 4 2.8 90.1

Volunteer 3 2.1 91.5 History 3 2.1 92.3

Friend recommends 2 1.4 93.0 Sightseeing 2 1.4 93.7

History 2 1.4 94.4 Sport: Rugby 2 1.4 95.1

Sightseeing 2 1.4 95.8 Volunteer 2 1.4 96.5

South Africa 2 1.4 97.2 Beaches 1 0.7 97.2

Tourist friendly 2 1.4 98.6 Friends recommend 1 0.7 97.9

Sport: Rugby 1 0.7 99.3 Sport: general 1 0.7 98.6

Sport: World Cup 1 0.7 99.3

No response 1 0.7 100.0 No response 1 0.7 100.0

Tourism and World Cup Football 297

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

the tournament (Z ¼ 22.364, asymp. sig. ¼ 0.018). Secondly, gender was analyzed.

Differences between pre- and post-test responses were independent of gender.

Thirdly, novelty preference was analyzed. Differences between pre- and post-test

responses were independent of novelty preference.

Assuming the World Cup is at least a partial cause of any differences between the

pre-test and post-test, the results can now be summarized by returning to the original

research questions. First, did the World Cup affect perceived knowledge of South

Africa? The answer is yes. Respondents perceived that they knew more about South

Africa after the tournament than before. The results were independent of time spent

watching the tournament, gender and novelty preference. Second, did the World Cup

affect the perceived level of South Africa’s development? The answer is yes. Surpris-

ingly, respondents perceived South Africa’s level of development to be lower after the

tournament than before. This effect was greatest among those who spent the most time

watching the tournament. Gender and novelty preference had no effect. Third, did the

World Cup affect perceived risk associated with travel to South Africa? The answer is

no, and there was no interaction with any of the variables tested. Fourth, did the World

Cup affect interest in travel to South Africa? The answer is no because interest was

already very high in the pre-test. There was no interaction with any of the variables

tested. Fifth, what are the primary motivations affecting interest in travel to South

Africa and were they affected by the World Cup? The primary pre-test motivations

were culture, learning, novelty and enjoyment. Interestingly, sport was not a primary

motivation. These motivations persisted after the World Cup; in addition, nature

increased considerably in prominence after the tournament. These motives were con-

stant regardless of time spent watching the tournament, gender and tourist role.

Lastly, what are the primary constraints affecting lack of interest in travel to South

Africa and were they affected by the World Cup? Because interest in travel to South

Africa was so great, few constraints were identified. Primary pre-test constraints

were the perception that South Africa is not safe, no knowledge about South Africa,

no interest, and better destinations elsewhere. After the World Cup, the perception

that South Africa is not safe was reduced. Results show five respondents identified

this constraint before the World Cup while only one identified it after the World

Cup. A similar effect occurred for the constraint “lack of knowledge.” With only

eight respondents identifying constraints, no interactions could reliably be identified.

Discussion

Cornelissen (2004) noted that two possible benefits of hosting mega sporting events are

short- and long-term increases in tourism. Short-term increases are due to sport fans

entering the country for the event. Long-term increases are due to favorable changes

in perceptions about the host country as a result of the mega event. This research

was conducted to explore whether South Africa’s hosting of the 2010 FIFA World

Cup would change prospective travelers’ perceptions of the country. Of particular inter-

est was perception of travel-related risk. The African continent is generally perceived as

risky (Ankomah & Crompton, 1990; Brown, 2000). This is a major constraint to

international travel there (Carter, 1998; Lepp et al., 2010; Sonmez & Graefe, 1998a).

298 A. Lepp & H. Gibson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

As African nations strive to develop their tourism industries, reducing perceived risk is

an important task.

Results of this study indicate that the World Cup contributed to an increase in

perceived knowledge about South Africa. This is potentially good news for South

Africa’s tourism industry. Previous research indicates that people know very little

about Africa and therefore have trouble distinguishing one African destination from

another (Lepp et al., 2011). As a result, common stereotypes of Africa as underdeve-

loped, war torn, famine struck and disease ravaged persist and negatively influence

interest in travel to any African nation. However, in situations where prospective tour-

ists know little about the destination, misperceptions can be quickly corrected by pro-

viding alternative, destination specific information through a trusted format such as an

official tourism website, television spots and promotional material (Barros et al., 2008;

Chalip et al., 2003; Gartner, 1993; Gartner & Shen, 1992; Lepp et al., 2011). It appears

the media respondents used to follow the World Cup (mostly TV and internet) had a

similarly positive effect and supports Chalip et al’s finding that television coverage

of sports events containing images about the host destination can potentially influence

images of a destination, particularly among individuals whose knowledge of a destina-

tion is scant. Furthermore, research from leisure studies suggests that gathering infor-

mation about an activity is a common method used to negotiate constraints related to

perceived risk (Coble, Selin, & Erickson, 2003). Thus, increased information about a

destination which tourists know little about would be useful in overcoming constraints

to travel, such as the perception that the destination is not safe.

Surprisingly, results of this research suggest the World Cup may have actually had a

negative effect on respondents’ perception of South Africa’s level of development.

Prior to the tournament, respondents felt South Africa was more developed than

other African countries. Research by Mathers (2004) suggests US college students typi-

cally think of South Africa this way. After the tournament however, respondents in this

study felt South Africa was equally developed in comparison with other African

countries. This effect was certainly not intended. As Van Der Merwe (2007) explained,

South Africa has been hosting mega sporting events to signal its arrival as one of the

world’s developed nations. However, Ndlovu (2010) notes South African leaders,

including the President, routinely emphasized the 2010 World Cup was not a South

African event but an African event. In other words, there was an attempt to give it a

more Pan-African feel and that South Africa was hosting the World Cup on behalf

of the entire African continent (Cornelissen, 2008). Perhaps media tangential to the

tournament also embraced this theme and emphasized the political, economic and cul-

tural ties between South Africa and the rest of the continent thus contradicting, some-

what, the notion of South African exceptionality. Likewise, media tangential to the

tournament may have taken the opportunity to raise awareness about the poverty and

underdevelopment which still exists across South Africa. Whatever the cause, it may

not be a detriment to South African tourism. Certainly, many tourists visit Africa

with the hope of viewing or even experiencing “the primitive” (Fursich & Robins,

2004; Mathers, 2004). As Mathers (2004) reported, respondents in her study were

happy to leave South Africa’s cities in order to visit the rural countryside and see the

“real Africa” as they called it. Novelty-seeking tourists might be particularly attracted

by this as well (Lepp & Gibson, 2003; 2008). However, emphasizing “the primitive” in

Tourism and World Cup Football 299

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

African tourism promotion is not only associated with an escape from modernity,

nature and rural villages but also disease (Lepp et al., 2011). Therefore, if this percep-

tion is a minor part of South Africa’s image it may be beneficial. However, if this

becomes a dominant image it could have negative consequences.

Perceptions of primitive Africa contribute to the risk associated with travel to the

continent. The converse is true as well. Perceptions of Africa as modern decrease per-

ceived risk associated with travel. For example, Lepp et al. (2011) found images of

modern hotels, restaurants, and airports on Uganda’s official tourism website decreased

perceived risk. By hosting the World Cup and thereby signaling its modernity, it is

possible that South Africa may have been able to reduce perceptions of risk associated

with travel there. Pre-test results show this sample of US college students perceived

South Africa as a moderately risky destination before the World Cup. In fact, results

were very similar to an earlier study measuring the degree of travel-related risk

college students perceive across Africa in general (Lepp & Gibson, 2008). After the

World Cup, perceptions of risk remained unchanged. South Africa was still perceived

as a moderately risky destination. Furthermore, differences in perceived risk by gender

and tourist role were non-significant and may warrant further investigation as there con-

tinue to be inconsistent findings across studies, particularly in relation to risk percep-

tions and gender (e.g. Carr, 2001; Kozak et al., 2007; Lepp & Gibson, 2003, 2008;

Lepp et al., 2010, 2011; Pizam et al., 2004; Qi, Gibson, & Zhang, 2009). Perhaps

risk-reducing images of modern South Africa generated by the successful tournament

were neutralized by the negative change in perceptions of South Africa’s level of

development.

None of this affected interest in travel to South Africa which was very high. Ninety

percent of respondents expressed an interest in travel to South Africa (assuming time

and money were not concerns). For comparison, Lepp et al. (2010) used exactly the

same question to measure interest in travel to Uganda. Results showed only 48% of

the 278 college students surveyed were initially interested. Perhaps the tremendous

interest in South Africa reflects anticipation of the World Cup. Perhaps it is an aberra-

tion of a convenience sample. Yet, in the initial pretest administered to 284 students,

interest was 86.3% which is not significantly different from the smaller sample used

for this study. Post-test results were identical to pretest results suggesting this high

level of interest was sustained beyond the World Cup. Interestingly, while interest in

travel to South Africa appears to be much higher than interest in visiting other

African destinations such as Uganda, the motivations identified by respondents in

this study are similar to the motivations identified for other destinations across

Africa (Awaritefe, 2003, 2008; Beh & Bruyere, 2007; Kruger & Saayman, 2010;

Lepp et al., 2010). These are culture, learning, novelty, enjoyment of travel and

nature. Interestingly, nature only emerged in the post-test. Suggesting it was

somehow inspired by the World Cup. One explanation is that advertising during the

World Cup may have invoked a “Wild Africa” or “Safari” theme. For example, a fre-

quent and visually appealing advertisement in the US market was for Travelers Insur-

ance and featured a variety of African wildlife coexisting peacefully together around a

watering hole. The advertisement was actually filmed in South Africa (Goundry, 2010).

Considering the most frequent motivations elicited by respondents in this study, there

does not seem to be one specific to South Africa which would explain the tremendous

300 A. Lepp & H. Gibson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

interest in traveling there. Even the World Cup or sports in general were rarely offered

as reasons for wanting to travel there. Thus, a primary motivation unique to South

Africa was not discovered. This raises an interesting and important question: how

can the tremendous interest in travel to in South Africa be explained? It is by far the

most visited destination in Africa (WTO, 2009). Yet, it seems to trigger the same motiv-

ations for travel as competing destinations. Furthermore, it is perceived similarly to the

rest of Africa in terms of travel-related risk (Lepp & Gibson, 2008).

An explanation may exist in developing a better understanding of constraints to

travel and how tourists negotiate them. Previous research demonstrated that exposure

to Uganda’s official tourism website significantly increased interest in traveling

there. This occurred not by generating new motivations but by eliminating perceived

constraints (Lepp et al., 2011). Something similar may be occurring with South

Africa as a result of continually and successfully hosting sporting mega events and sup-

ports Smith’s (2005) contention of the ability to reimage a destination through sport.

Lepp et al. identified five factors underlying perceived risk associated with travel to

Africa: a lack of modern attributes, an abundance of primitive attributes, cultural differ-

ences and barriers, violence and crime, and risk from interpersonal relationships. The

first two risk factors have already been discussed and may have neutralized each

other in their influence on perceived risk associated with travel to South Africa. Yet

other factors are worth considering in relation to successfully hosting mega-events.

First, mega events may help potential tourists overcome constraints related to cultural

differences and barriers. In this case, sport serves as common cultural ground. Indeed,

Van Der Merwe (2007) already examined how South Africa’s hosting of the Rugby

World Cup helped the fledgling democracy forge common ground between black

and white South Africans. Likewise, the World Cup may help forge common ground

between South Africa and the rest of the football loving world. Second, successfully

hosting mega events may help potential tourists overcome constraints related to vio-

lence and crime. With all the global media coverage mega events generate, they

become targets for terrorism (Toohey et al., 2003). Already, London is preparing

anti-terrorism measures for the 2012 Summer Olympics (ESPN.com, 2010). When a

mega event is hosted without incident, it is an indication that a country can successfully

keep its citizens and tourists safe despite lurking dangers. Thirdly, hosting mega events

means being hospitable. It means opening your doors to the world and inviting in stran-

gers. This may reduce risks related to interpersonal contact simply by giving the

impression of hospitality.

Certainly the issue of tourism and perceived risk in South Africa is complex. There

are undoubtedly many more mitigating factors than sporting mega-events. Neverthe-

less, this research suggests that sporting mega events can affect travel-related percep-

tions and therefore travel decision making (Toohey et al., 2003). With this sample of

US undergraduate college students, the 2010 FIFA World Cup did influence percep-

tions of South Africa although the impact was probably not as significant as event plan-

ners would have hoped. Perhaps, this World Cup should be seen as part of a broader

mega-event strategy for South Africa (Swart & Bob, 2007). In the years just prior to

hosting the FIFA World Cup, South Africa hosted the Rugby World Cup, the

Cricket World Cup, and made unsuccessful bids for the 2006 FIFA World Cup and

the 2012 Summer Olympics. Together, these events may have a cumulative effect on

Tourism and World Cup Football 301

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

perceived risk larger than that of a single event. Undoubtedly, this is an area of research

which deserves further attention, particularly when considering the World Cup will

soon be hosted by Russia (2018) and Qatar in the Middle East (2022) – two desti-

nations perceived as risky for travel (Lepp & Gibson, 2008).

Notes on Contributors

Andrew Lepp is an Associate Professor with Kent State University’s Recreation, Park and Tourism

Management program. He received his PhD from the University of Florida. Prior to this he worked for

seven years in the fields of natural resource management, interpretation and tourism development. During

this time he worked with the United States Park Service, the United States Forest Service and the Uganda

Wildlife Authority in East Africa. This diversity of experience helped shape his research interests in

ecotourism, conservation and sustainable development and tourism development with a focus on Africa.

Heather Gibson is an associate professor at the University of Florida specializing in the sociology of

leisure, sport and tourism. Her research interests include leisure and tourism in later life; women travelers;

sport tourism with a particular focus on sport-related travel in later life and small-scale events; and perceived

risk in travel. Dr Gibson has published over 40 peer reviewed articles in scholarly journals and she edited the

book Sport Tourism: Concepts and Theories. Currently, she is an Associate Editor for Leisure Sciences,

Regional Editor for North America for Leisure Studies, and an editorial board member for the Journal of

Sport Management, the Journal of Sport & Tourism, and World Leisure Journal

References

Akama, J.S., & Kieti, D.M. (2003). Measuring tourist satisfaction with Kenya’s wildlife safari: A case study

of Tsavo West National Park. Tourism Management, 24(1), 73–81. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00044-4.

Altbeker, A. (2005). Is South Africa really the world’s crime capital? SA Crime Quarterly, 11, 1–8.

Ankomah, P.K., & Crompton, J.L. (1990). Unrealized tourism potential: The case of sub-Saharan Africa.

Tourism Management, 11(1), 11–28. doi:10.1016/0261-5177(90)90004-S.AVERT.org (2010). Sub-Saharan Africa HIV & AIDS statistics. Retrieved from http://www.avert.org/

africa-hiv-aids-statistics.htm.

Awaritefe, O.D. (2003). Destination environment quality and tourists’ spatial behavior in Nigeria: A case

study of Third World Tropical Africa. International Journal of Tourism Research, 5(4), 251–268.

doi: 10.1002/jtr.435.Awaritefe, O.D. (2008). Destination image differences between prospective and actual tourists in Nigeria.

Journal of Vacation Marketing, 10(3), 264–281. doi: 10.1177/135676670401000306.Barros, C.P., Butler, R., & Correia, A. (2008). Heterogeneity in destination choice. Journal of Travel

Research, 47(2), 235–246. doi: 10.1177/0047287508321200.Beh, A., & Bruyere, B.L. (2007). Segmentation by visitor motivation in three Kenyan national reserves.

Tourism Management, 28(6), 1464–1471. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2007.01.010.

Bleby, M. (2010). No need to pack your flak jacket. The Sydney Morning Herald, May 29, 2010. Retrieved

from http://www.smh.com.au/opinion/society-and-culture/no-need-to-pack-your-flak-jacket-

20100528-wlc5.html.

Bly, L. (2010). US Soccer fans warned of World Cup risks. USA Today, May 26, 2010. Retrieved from

http://travel.usatoday.com/destinations/dispatches/post/2010/05/us-soccer-fans-warned-of-world-cup-

risks/94403/1.

Brown, D.O. (2000). Political risk and other barriers to tourism promotion in Africa: Perceptions of

US-based travel intermediaries. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 6(3), 197–210. doi: 10.1177/135676670000600301.

Brunt, P., Mawby, R., & Hambly, Z. (2000). Tourist victimization and the fear of crime on holiday. Tourism

Management, 21(4), 417–424. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00084-9.

302 A. Lepp & H. Gibson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

Carr, N. (2001). An exploratory study of gendered differences in young tourists’ perception of danger within

London. Tourism Management, 22(5), 565–570. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00014-0.Carter, S. (1998). Tourists’ and travellers’ social constructions of Africa and Asia as risky locations.

Tourism Management, 19(4), 349–358. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00032-6.Chalip, L., Green, B.C., & Hill, B. (2003). Effects of sport event media on destination image and intention to

visit. Journal of Sport Management, 17(3), 214–234.

Coble, T.G., Selin, S.W., & Erickson, B.B. (2003). Hiking alone: Understanding fear, negotiation strategies

and leisure experiences. Journal of Leisure Research, 35(1), 1–22.

Cohen, E. (1972). Towards a sociology of international tourism. Sociological Research, 39(1), 164–182.

Cornelissen, S. (2004). Sport mega-events in Africa: Processes, impacts and prospects. Tourism Hospitality

Planning and Development, 1(1), 39–55. doi: 10.1080/1479053042000187793.Cornelissen, S. (2008). Scripting the nation: Sport, mega events, foreign policy and state building in post-

apartheid South Africa. Sport in Society, 11(4), 481–493. doi: 10.1080/17430430802019458.Cossens, J., & Gin, S. (1994). Tourism and AIDS: The perceived risk of HIV infection and destination

choice. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 3(4), 1–20. doi: 10.1300/J073v03n04_01.Crawford, D., Jackson, E., & Godbey, G. (1991). A hierarchical model of leisure constraints. Leisure

Sciences, 13(4), 309–320. doi: 10.1080/01490409109513147.Crompton, J. (1979). Motivations for pleasure vacation. Annals of Tourism Research, 6(4), 408–424.

doi:10.1016/0160-7383(79)90004-5.Enders, W., Sandler, T., & Parise, G.F. (1992). An econometric analysis of the impact of terrorism on

tourism. Kyklos, 45(4), 531–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6435.1992.tb02758.xESPN.com (2010). 2012 Games have ’severe’ terror threat. Retrieved from http://sports.espn.go.com/oly/

news/storyid=5849116.

Florek, M., Breitbarth, T., & Conejo, F. (2008). Mega events¼mega impact?: Travelling fans’ experience

and perceptions of the 2006 FIFA World Cup host nation. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 13(3),

199–219. doi: 10.1080/14775080802310231.Fursich, E., & Robins, M.B. (2004). Visiting Africa: Constructions of nation and identity on travel websites.

Journal of African and Asian Studies, 39(1–2), 133–152. doi: 10.1177/0021909604048255.Gartner, W.C. (1993). Image formation process. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 2(2–3),

191–215. doi: 10.1300/J073v02n02_12.Gartner, W.C., & Shen, J. (1992). The impact of Tiananmen Square on China’s tourism image. Journal of

Travel Research, 30(4), 47–52. doi: 10.1177/004728759203000407.Gorman, B. (2010). ESPN Reports 4.9 Billion Minutes Spent On 2010 FIFA World Cup Digital Media

Content. Retrieved from http://tvbythenumbers.zap2it.com/2010/07/13/espn-reports-4-9-billion-

minutes-spent-on-2010-fifa-world-cup-digital-media-content/57017.

Goundry, N. (2010). Travelers Insurance commercial shoots in South Africa. Retrieved from http://www.

thelocationguide.com/blog/2010/07/travelers-insurance-commercial-shoots-in-south-africa/.

Hiller, H. (2000). Mega-events, urban boosterism and growth strategies: An analysis of the objectives and

legitimations of the Cape Town 2004 Olympic bid. International Journal of Urban and Regional

Research, 24(2), 439–458. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.00256.Hollier, R. (1991). Conflict in the Gulf: Response of the tourism industry. Tourism Management, 12(1),

2–4. doi:10.1016/0261-5177(91)90022-L.Hong, S., Kim, J., Jang, H., & Lee, S. (2006). The roles of categorization, affective image and constraints on

destination choice: An application of the NMNL model. Tourism Management, 27(5), 750–761. doi:

10.1016/j.tourman.2005.11.001.

Hung, K., & Petrick, J.F. (2010). Developing a measurement scale for constraints to cruising. Annals of

Tourism Research, 37(1), 206–288. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2009.09.002.Keim, C. (1999). Mistaking Africa: Curiosities and inventions of the American mind. Boulder, CO:

Westview Press.

Kim, N., & Chalip, L. (2004). Why travel to the FIFAWorld Cup?: Effects of motives, background, interest,

and constraints. Tourism Management, 25(6), 695–707. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2003.08.011.

Kirk, J., & Miller, M.L. (1986). Reliability and validity in qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications.

Kozak, M., Crotts, J., & Law, R. (2007). The impact of the perception of risk on international travelers.

International Journal of Tourism Research, 9(4), 233–242. doi: 10.1002/jtr.607.

Tourism and World Cup Football 303

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

Kruger, M., & Saayman, M. (2010). Travel motivation of tourists to Kruger and Tsitsikamma National

Parks: A comparative study. South African Journal of Wildlife Research, 40(1), 93–102. doi:

10.3957/056.040.0106.Kynoch, G. (2005). Crime, conflict and politics in transition-era South Africa. African Affairs, 104(416),

493–514. doi: 10.1093/afraf/adi009.Larsen, S., Brun, W., & Øgaard, T. (2009). What tourists worry about – construction of a scale measuring

tourist worries. Tourism Management, 30(2), 260–265. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2008.06.004.

Lawson, R., & Thyne, M. (2001). Destination avoidance and inept destination sets. Journal of Vacation

Marketing, 7(3), 199–208. doi: 10.1177/135676670100700301.Lepp, A., & Gibson, H. (2003). Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Annals of Tourism

Research, 30(3), 606–624. doi:10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00024-0.Lepp, A., & Gibson, H. (2008). Sensation seeking and tourism: Tourist role, perception of risk and destina-

tion choice. Tourism Management, 29(4), 740–750. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2007.08.002.

Lepp, A., Gibson, H., & Lane, C. (2010). The impact of a tourism website on motivations and constraints.

Abstracts from the 2010 Leisure Research Symposium. Ashburn, VA: National Recreation and Park

Association. http://www.nrpa.org/uploadedFiles/book%20of%20abstracts%202010.pdf.

Lepp, A., Gibson, H., & Lane, C. (2011). Image and perceived risk: A Study of Uganda and its official

tourism website. Tourism Management, 32(3), 675–684. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2010.05.024.

Mathers, K. (2004). Reimagining Africa: What American students learn in South Africa. Tourism Review

International, 8(2), 127–141. doi: 10.3727/1544272042782200.Ndlovu, S.M. (2010). Sports as cultural diplomacy: The 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa’s foreign

policy. Soccer & Society, 11(1–2), 144–153. doi:10.1080/14660970903331466.Nielsen (2010a). 2010 World Cup Final Becomes Most Watched Soccer Game in U.S. TV History.

Retrieved from http://blog.nielsen.com/nielsenwire/media_entertainment/2010-world-cup-final-

becomes-most-watched-soccer-game-in-u-s-tv-history/.

Nielsen (2010b). 2010 World Cup Reaches Nearly 112 Million U.S. Viewers. Retrieved from http://

blog.nielsen.com/nielsenwire/media_entertainment/2010-world-cup-reaches-nearly-112-million-u-s-

viewers/.

Nyaupane, G., & Andereck, K.L. (2008). Understanding travel constraints: Application and extension of a

leisure constraints model. Journal of Travel Research, 46(4), 433–439. doi: 10.1177/0047287507308325.

Pennington-Gray, L., & Kerstetter, D. (2002). Testing a constraints model within the context of nature based

tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 40(4), 416–423. doi: 10.1177/0047287502040004008.Pizam, A., Jeong, G., Reichel, A., Van Boemmel, H., Lusson, J., Steynberg, L., State-Costache, O., Volo,

S., Kroesbacher, C., Hucerova, J., & Montmany, N. (2004). The relationship between risk taking,

sensation seeking and the tourist behavior of young adults: A cross-cultural study. Journal of

Travel Research, 42(3), 251–260. doi: 10.1177/0047287503258837.Qi, C., Gibson, H., & Zhang, J. (2009). Perceptions of risk and travel intentions: The case of China and

the Beijing Olympic Games. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 14(1), 43–67. doi: 10.1080/14775080902847439.

Quintal, V.A., Lee, J.A., & Soutar, G.N. (2010). Risk, uncertainty and the theory of planned behavior: A

tourism example. Tourism Management, 31(6), 797–805. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2009.08.006.

Reisinger, Y., &Mavondo, F. (2005). Travel anxiety and intentions to travel internationally: Implications of

travel risk perception. Journal of Travel Research, 43(3), 212–225. doi: 10.1177/0047287504272017.Roehl, W., & Fesenmaier, D. (1992). Risk perceptions and pleasure travel: An exploratory analysis. Journal

of Travel Research, 2(4), 17–26. doi: 10.1177/004728759203000403.Simpson, P.M., & Siguaw, J.A. (2008). Perceived travel risks: The traveler perspective and manageability.

International Journal of Tourism Research, 10(4), 315–327. doi: 10.1002/jtr.664.Sirakaya, E., Sheppard, A., & McLellan, R. (1997). Assessment of the relationship between perceived

safety at a vacation site and destination choice decisions: Extending the behavioral decision-making

model. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 21(2), 1–10. doi: 10.1177/109634809702100201.

Smith, A. (2005). Reimaging the city: The value of sport initiatives. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(1),

217–236. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2004.07.007.

304 A. Lepp & H. Gibson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

], [

And

rew

Lep

p] a

t 06:

11 2

2 Se

ptem

ber

2011

Sonmez, S., & Graefe, A. (1998a). Determining future travel behavior from past travel experience and

perceptions of risk and safety. Journal of Travel Research, 37(2), 171–177. doi: 10.1177/004728759803700209.

Sonmez, S., & Graefe, A.R. (1998b). Influence of terrorism risk on foreign tourism decisions. Annals of

Tourism Research, 25(1), 112–144. doi:10.1016/S0160-7383(97)00072-8.South Africa (2010a). SA’s World Cup ‘near-perfect’: FIFA. Retrieved from http://www.southafrica.info/

2010/nearperfect.htm.