Third and Last: Epigraphic Notes on the Ugaritic Tablet KTU² 1.19, Journal of the American Oriental...

Transcript of Third and Last: Epigraphic Notes on the Ugaritic Tablet KTU² 1.19, Journal of the American Oriental...

Journal of the American Oriental Society 136.4 (2016) 851

Third and Last: Epigraphic Notes on the Ugaritic Tablet KTU 1.19

Jonathan Yogev and Shamir YonaBen-gurion univerSitY of the negev

One of the most famous stories in Ugaritic literature is the legend of Aqht that was found at Ras Shamra, Syria, during the early 1930s. Written in Ugaritic script and spread over three worn and broken tablets, this text has been thoroughly studied for the past eighty years. More than a few studies have dealt with the following questions: Is the end of the known text in the third tablet really the end of the story? Or is there perhaps a missing tablet, or tablets, that continue the plot from the third tablet (KTU 1.19)? These questions have been answered on the base of storyline and plot, and many believe that there must be more contents that com-plete this story and that it cannot end where the text ends. In this paper we have tried to answer this question based on epigraphic evidence found in the third tablet of the Aqht legend. After carefully examining four unique features of this tablet, we conclude that KTU 1.19 is, in fact, the last one of this specific sequence. We support this evidence by an analysis of contents, showing that there is indeed enough text to suggest a proper closure for this legend.

After the first interpretations of the poetic Ugaritic tablets from Ras Shamra that were most-ly from Virolleaud in the 1930s, it became clear that some subjects and characters appear in more than a single tablet. 1 These discoveries led to the logical conclusion that some of the poetic stories were long enough to be written on more than a single tablet. The next step was to fit the tablets together and to find their correct sequence using various elements from the storylines. For example, Virolleaud designated the three tablets of the Krt epic as IK (KTU 1.14), IIK (KTU 1.16), and IIIK (KTU 1.15). 2 A few years later, further interpretation pro-posed interchanging IIK and IIIK, an interpretation which has since been widely accepted. 3 Another example of a “sequence puzzle” can be found in the Ugaritic Baal Cycle. Although most studies agree on the correct sequence of the tablets, 4 one can still find opinions that question this sequence. 5 When we try to solve a puzzle, the easiest way is to determine the limits of the frame, in this case the beginning and the end. This is, of course, a matter of debate that rests on interpretation. The difficulty in solving these puzzles is great because of the poor condition of the tablets when they were discovered, especially around the edges.

1. Ch. Virolleaud, “La mort de Baal, poème de Ras-Shamra (Ie AB),” Syria 15 (1934): 305–36; “La Naissance des dieux gracieux et beaux: Poème phénicien de Ras Shamra,” Syria 14 (1933): 128–51; “La révolte de Koser contre Baal: Poème de Ras Shamra (III AB, A),” Syria 16 (1935): 29–45; “Les chasses de Baal: Poème de Ras Shamra,” Syria 16 (1935): 247–66; “La légende phénicienne de Danel,” Syria 18 (1937): 104–13; “Un nouveau chant du poème d’Aleïn-Baal,” Syria 13 (1932): 113–63.

2. Ch. Virolleaud, La légende de Keret, roi des sidoniens (Mission de Ras-Shamra, vol. 2; Paris: Geuthner, 1936); “Le roi Kêret et son fils (II K): Poème de Ras Shamra,” Syria 22 (1941): 105–36; “Le roi Kêret et son fils,” Syria 22 (1941): 197–217; “Le roi Kéret et son fils (II K),” Syria 23 (1942): 1–20.

3. H. L. Ginsberg and W. F. Albright, “The Legend of King Keret: A Canaanite Epic of the Bronze Age,” BASOR, Supplementary Studies, no. 2/3 (1946): 1–50.

4. KTU 1.1–1.6.5. See the table in G. del Olmo Lete, Mitos y Leyendas de Canaan: Segun la Tradicion de Ugarit (Madrid:

Institucion San Jeronimo, 1981), 83; see also J. Yogev, “How Wide Should a Column Be?” UF 42 (2011): 847–52.

852 Journal of the American Oriental Society 136.4 (2016)

Furthermore, it is also possible that other tablets that were a part of the original sequence are missing. Another difficulty is that our understanding of the Ugaritic language is far from perfect. It is difficult to determine the order of the storyline when we are still struggling with the interpretation of words and sentences. This paper deals with the ending of the legend of Aqht, or KTU 1.19. Based mainly on epigraphic evidence we propose that KTU 1.19 is indeed the last in the sequence of Aqht,

The legend of Aqht consists of three tablets (KTU 1.17; 1.18; 1.19), 6 all found in the “Library of the High Priest” at Ugarit between 1930 and 1931. 7 It was first translated by Virolleaud in 1936, who named the story after the main protagonist, Dan-ilu. 8 Later, based on a small inscription at the top of KTU 1.19: 9 [l]aq[h]t, the legend was renamed after Dan-ilu’s son, Aqht. In total, about 480 complete or partial lines have survived on three tablets, and much of the contents is missing. Many elements of the legend are debatable, while other details are accepted by most scholars. Briefly, the legend tells of a well-known and respected man called Dan-ilu. 10 Dan-ilu longs for a son, and after appealing to the gods, he is given a son named Aqht. Dan-ilu receives a gift for his son from one of the gods, Kothar-and-Ḫasi—a wonderful bow, which is later coveted by the goddess Anat. 11 This conflict leads to Aqht’s death: he is killed by Anat and an accomplice, Yṭpn. His father and sister, Pģt, mourn for him. Dan-ilu sets off to find his son’s remains, and confronts some eagles, inside one of whom he finds his son’s remains. Dan-ilu mourns for seven years. Then, after a dialogue between him and his daughter, the latter sets out to reap vengeance for her brother’s death.

the Sequence of the taBletS

As we have seen above, Virolleaud suggested the following numbers for the three tab-lets: ID (KTU 1.19), IID (KTU 1.17), IIID (KTU 1.18), but a different sequence was soon

6. KTU 1.1 7 = CTA 17 = RS 2.[004]; KTU 1.18 = CTA 18 = RS 3.340; KTU 1.19 = CTA 19 = RS 3.322+3.349+3.366. KTU3 (CAT): See M. Dietrich, O. Loretz, and J. Sanmartin, eds., The Cuneiform Alphabetic Texts from Ugarit, Ras Ibn Hani and Other Places (Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 2013); CTA: A. Herdner, Corpus des tablettes en cuneiformes alphabetiques: decouvertes a Ras Shamra-Ugarit de 1929 a 1939 (Mission de Ras Shamra, vol. 10; Paris: Geuthner, 1963).

7. C. F. A. Schaeffer, Ch. Virolleaud, and F. Thureau-Dangin, La deuxieme campagne de fouilles a Ras-Shamra (Printemps 1930): Rapport et études préliminaires (Paris: Geuthner, 1931).

8. Ch. Virolleaud, La légende phénicienne de Danil: Texte cunéiforme alphabétique avec transcription et com-mentaire (Paris: Geuthner, 1936).

9. This phenomenon also exists on tablets KTU 1.14; 1.16 (Krt), and KTU 1.6 (Baal), all probably inscribed by the same master scribe, Ili-milku. See D. F. Freilich, “Ili-Malku the ṯ’y,” SEL 9 (1992): 21–26; G. Mazzini, “Baal and Niqmaddu—A Suggestion to Ugaritic KTU 1.2 I, 36–38,” SEL 21 (2004): 65–69; J. C. de Moor, “How Ilimilku Lost His Master (RS 92.2016),” UF 40 (2009): 179–90; J. Yogev and Sh. Yona, “A Trainee and a Skilled Ugaritic Scribe—KTU 1.12 and KTU 1.4,” ANES 50 (2013): 237–42.

10. According to Gordon, Dan-ilu is a king. See C. H. Gordon, Ugaritic Literature: A Comprehensive Trans-lation of the Poetic and Prose Texts (Rome: Pontificum Institutum Biblicum, 1949), 84–85. For the identification of Dan-ilu in biblical literature, see H. H. P. Dressler, “The Identification of the Ugaritic Dnil with the Daniel of Ezekiel,” VT 29 (1979): 152–61; id., “Reading and Interpreting the Aqht Text: A Rejoinder to Drs J. Day and B. Margalit,” VT 34 (1984): 78–82; J. Day, “The Daniel of Ugarit and Ezekiel and the Hero of the Book of Daniel,” VT 30 (1980): 174–84; B. Margalit, “Interpreting the Story of Aqht: A Reply to H. H. P. Dressler, VT 29 (1979): 152–61,” VT 30 (1980): 361–65; M. Noth, “Noah, Daniel und Hiob in Ezechiel XIV,” VT 1 (1951): 251–60.

11. For further on this bow see H. H. P. Dressler, “Is the Bow of Aqhat a Symbol of Virility?” UF 7 (1975): 217–20; D. R. Hillers, “The Bow of Aqhat: The Meaning of a Mythological Theme,” in Essays Presented to Cyrus H. Gordon on the Occasion of His Sixty-fifth Birthday, ed. H. A. Hoffner, Jr. (Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1973), 71–80; Y. Sukenik, “The Composite Bow of the Goddess Anath,” BASOR 107 (1947): 11–15.

853Yogev and Yona: Epigraphic Notes on the UgariticTablet KTU 1.19

suggested 12 and has since been accepted by most scholars. Many important studies suggest that the ending of the legend of Aqht is missing. This suggestion is based on several pieces of evidence. The first is contents. At the end of KTU 1.19, Pģt goes to Yṭpn, probably to avenge her brother’s murder. Some say that the murder of Yṭpn and its consequences must have been related on a fourth, missing, tablet. 13 The second piece of evidence concerns the tablets of the Rpum (KTU 1.20–1.22). The name of Dan-ilu appears once in KTU 1.20 (II, 7–8). Furthermore, the tablet KTU 1.18 of the legend of Aqht was found near KTU 1.20, and therefore some claim that at least one of the Rpum tablets continues the legend of Aqht. 14 We contend that KTU 1.19 is indeed the last in the sequence based on epigraphic evidence that deals with the work of the scribe when he prepared the third tablet.

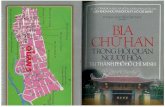

The Number of ColumnsWe present three drawings of the tablets depicting their basic outlines and measurements. 15

The first tablet 16 in the sequence is partially broken. Its width is about 12 cm, and its length almost 17 cm. Two columns have survived on each side of the tablet, but also only partially. The break on the right side clearly shows that at least one column (probably III and IV) is missing from each side. It is therefore likely that it, like others that were found in the “Library of the High Priest,” 17 originally has three columns per side.

The second tablet 18 is badly damaged. Its width is about 7 cm and its length about 11.5 cm. Only one partial column has survived on each side, and only a handful of complete lines. It is difficult to judge the original size of KTU 1.18 and the number of columns it contained. Some scholars have suggested four, but in our view this is only conjecture.

The third tablet 19 is in relatively good condition. Its width is about 11.6 cm and its length about 17.5 cm, and it originally had four columns. This raises the question: did the scribe preserve uniformity when preparing the tablets for writing? A good example can be found in the Krt epic, where all three tablets in the sequence (KTU 1.14, 1.15, 1.16) are of the same width (about 17 cm) and have three columns on each side. In our case, the first tablet had more than four columns while we have no information regarding the second. This means that there was a certain reduction in the number of columns between the first and third tablets. We suggest that the third tablet was made smaller because the scribe knew that there was not enough text left to fill six columns, and he wished to utilize the space efficiently.

12. U. Cassuto, “Daniel e le spighe: Un episodia della Tavola 1 D di Ras Shamra,” Orientalia 8 (1939): 238–43; H. L. Ginsberg, “The North-Canaanite Myth of Anath and Aqhat,” BASOR 97 (Feb. 1945): 3–10; id., “The North-Canaanite Myth of Anath and Aqhat II,” BASOR 98 (Apr. 1945): 15–23.

13. J. C. L. Gibson, Canaanite Myths and Legends, 2nd ed. (London: T. and T. Clark, 2014) 23–28; F. Landy, The Tale of Aqhat (London: Menard, 1981), 14–16; S. B. Parker, “Aqhat,” in Ugaritic Narrative Poetry, ed. S. B. Parker (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 1997), 49–80; N. Wyatt, Religious Texts from Ugarit: The Words of Ilimilku and His Colleagues, 2nd ed. (Sheffield: 2002), 246–48.

14. A. Caquot, “Les Rephaim ougaritiques,” Syria 37 (1960): 75–93; J. C. de Moor, An Anthology of Religious Texts from Ugarit (Leiden: Brill, 1987), 224; J. Gray, The Legacy of Canaan: The Ras Shamra Texts and Their Rele-vance to the Old Testament (Leiden: Brill, 1957), 91–93; B. Margalit, The Ugaritic Poem of Aqht: Text, Translation, Commentary (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1989), 5–6.

15. All facsimiles were made by means of high resolution images. We would like to thank all those involved in the Inscriptifact project of the University of Southern California West Semitic Research (www.inscriptifact.com), who gave us access to their Ugaritic database.

16. Preserved in the Louvre.17. See KTU 1.3, 1.5, 1.6, 1.10, 1.14, 1.15, and 1.1618. Preserved at the British Museum.19. Preserved at the Louvre.

854 Journal of the American Oriental Society 136.4 (2016)

Fig. 1. KTU 1.17

Fig. 2. KTU 1.18 Fig. 3. KTU 1.19

855Yogev and Yona: Epigraphic Notes on the UgariticTablet KTU 1.19

Fig. 4. KTU 1.19 Obv., Photo (C) RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Mathieu Rabeau.

856 Journal of the American Oriental Society 136.4 (2016)

Divided WordsIn many cases, in order to utilize all available space and to avoid writing into the inter-

columnium, the Ugaritic scribes divided words and spread them over two lines. Segert made a list of such writings in many of the mythological texts from Ugarit. 20 According to his study, our first tablet (KTU 1.17) contains four divided words and the second tablet (KTU 1.18) only one. In contrast, the third tablet (KTU 1.19) contains thirteen divided words, eleven of them in column IV. This means that over sixty percent of divided words in the legend of Aqht appear in its final column. It seems that the scribe squeezed in these words in order to complete his work on this tablet. If there had been further tablets, there would have been no need for this measure.

Inscription on the Edge of the TabletTo the left of column IV on the edge of KTU 1.19 there is a small inscription written verti-

cally (see Fig. 5), which was probably meant as a note for the reader.This line reads whndt . yṯb . lmspr. Parker translates “and here one returns to the story” 21

“. . . where the plot resumes after the interruption caused by Daniel’s rituals following Aqht’s death.” According to Pardee, this line should be translated: “Here is where to resume the story.” He suggests that this colophon is “an indication of how the story is to be taken up to the next tablet.” 22

A different translation can be based on other Ugaritic sources. The first appears in KTU 1.4, V, 42–43, which was probably written by the same scribe. In the middle of the fifth col-umn of this tablet the scribe made two vertical lines and wrote a note for the reader between them: wṯblmspr . ktlakn / ġlmm “and to return to the recitation (about) when the lads are sent.” 23 This note resembles that on the edge of KTU 1.19, and its function is probably to guide the reader to recite the part that begins with ktlakn / ġlmm once more. 24

The second example is KTU 1.40, 35: wṯb . lmspr . m[š]r . mšr . bt .ugrt “and to return to the recitation of ‘rectitude,’ rectitude of the daughter of Ugarit.” 25 Therefore the note on the edge of KTU 1.19 can be translated “and here this shall be recited again.” 26 But just what should be recited again? Several scholars have suggested that the reader should recite the part in the text that is parallel to the inscription on the edge, probably lines 10–24 (see Fig. 1). 27

20. S. Segert, “Words Spread over Two Lines,” UF 19 (1987): 283–88.21. “Aqhat,” 78. However, it is difficult to consider Dan-ilu’s rituals as an interruption in the storyline.22. D. Pardee, “The Aqhatu Legend,” in The Context of Scripture, vol. I, ed. W. H. Hallo and K. L. Younger

(Leiden: Brill, 1997), 356 n. 140.23. M. S. Smith and W. T. Pitard, The Ugaritic Baal Cycle, vol. II; Introduction with Text, Translation and Com-

mentary of KTU 1.3–1.4 (Leiden: Brill, 2009), 540, 574–76.24. The note in KTU 1.4, V, 42–43, is written on the front of the tablet, while that in KTU 1.19 is written on

the side. This can be compared with Ili-milku’s signature, which can be found on the front of tablet KTU 1.6 (VI, 54–58), but also on the edges of KTU 1.4, 1.16, and 1.17. For scribal education in Ugarit see W. H. van Soldt, “Babylonian Lexical, Religious and Literary Texts: And Scribal Education at Ugarit and Its Implications for the Alphabetic Literary Texts,” in Ugarit— ein Ostmediterranes Kulturzentrum im Alten Orient, ed. M. Dietrich and O. Loretz (Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 1993), 171–212.

25. D. Pardee, Ritual and Cult in Ugarit (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2002), 77–83.26. Perhaps also in KTU 1.23, 56–57: yṯbn / yspr . l ẖmš . . . : “he shall recite five times.” The complete Ugaritic

word mspr appears only in KTU 1.4; 1.19; 1.40. See J. L. Cunchillos, J. P. Vita, and J. Á. Zamora, A Concordance of Ugaritic Words (Piscataway, N.J.: Gorgias Press, 2003), 1995. For the translation of mspr see G. del Olmo Lete and J. Sanmartin, Diccionario de la Lengua Ugaritica (Sabadell/Barcelona: Editorial AUSA, 1996), 295.

27. J. C. L. Gibson, Canaanite Myths and Legends, 122; J. C. de Moor, An Anthology of Religious Texts from Ugarit (Leiden: Brill, 1987), 265. According to Dijkstra, “. . . ‘and this should be recited once more’ (referring to

857Yogev and Yona: Epigraphic Notes on the UgariticTablet KTU 1.19

Fig. 5. Inscription on the left edge of KTU 1.19.

858 Journal of the American Oriental Society 136.4 (2016)

The main difficulty with this suggestion is that lines 10–24 are not a part of a separate literary unit, since Dan-ilu’s mourning rituals appear in lines 1–25.

Both of the similar notes mentioned here tell the reader exactly what to recite again, whether a certain part of the text, or the virtues of the daughter of Ugarit, which shows that scribes needed to be specific in their notes. In KTU 1.19 the note is general, not specific, and so our contention is that this note refers to the whole legend. Written on the side of the last column of the last tablet, it was meant to remind the reciter that this story should be told over and over again in the future. 28

The Final Line of the TabletLine 61 in KTU 1.19, IV is unique. Generally, Ugaritic scribes utilize as much of the tab-

let’s surface as possible, and therefore they wrote on the side, upper, and lower edges. In this case, line 61 was written on the bottom of the tablet, as may be seen in Fig. 6.

Although the bottom of the tablet is broken, two important epigraphic details can be observed: 1) when the scribe wrote the last line, he did it without consideration of the rulings separating columns, 29 and 2) after squeezing the text onto the surface of the last column, the scribe finished his work utilizing the space under line 61. When needed, the scribes utilized the lower edge of the tablet to the full, 30 and in KTU 1.19 there is still enough space left for at least twenty more letters, or two full lines.

More important than epigraphic details are the contents of the final line. It is unreasonable to claim that line 61 is the last in the story without demonstrating a full closure of literary issues. After Dan-ilu’s mourning rituals, we see that Pģt sets off to avenge her brother’s death. She arrives at Yṭpn’s tent in disguise, where the two share wine while Yṭpn brags about his killings. 31 Thus we have the motive and the opportunity for Pģt’s vengeance and the only thing that is left is the final blow for the completion of the axis of feminine vengeance: Anat-Aqht / Pģt-Yṭpn. 32 It is difficult to imagine a fourth tablet consisting of hundreds of lines just to complete the story.

the legend from iv 23 onwards),” “Ugaritic Prose,” in Handbook of Ugaritic Studies, ed. W. G. E. Watson and N. Wyatt (Leiden: Brill, 1999), 140.

28. It is also possible that this inscription was meant to remind the reciter to repeat the entire last column of the legend.

29. Unlike KTU 1.14, 1.16, 1.3 and other instances where the scribe wrote on the bottom or upper part of the tablets without violating the separating lines.

30. See KTU 1.14, 1.23, 1.24, 1.100, and more.31. KTU 1.19, IV, 36–60.32. See S. B. Parker, The Pre-Biblical Narrative Tradition (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 1989), 131:

“Assuming that the poem as a whole would have concluded with the establishment of restoration of order as under-stood by the culture. . . it is legitimate to conclude that Yṭpn was killed before the end of the poem.”

Fig. 6. Inscription on the lower edge of KTU 1.19.

859Yogev and Yona: Epigraphic Notes on the UgariticTablet KTU 1.19

The transliteration of line 61 is [ y/ẖ/?]bl lbh . km bṯn y[ l/]ṣah ṯnm tšqy msk hwt tšqy. The first complete visible words are lbh . km bṯn “his heart like a serpent.” 33 The image of a serpent is well known in Ugaritic texts. It appears when Baal and Mot struggle at the end of KTU 1.6: yngḥn / krumm . mt . ʿz . bʿl / ʿz . ynṯkn . bṯnm / mt . ʿz . bʿl . ʿz 34 “they ram each other like rams, Mot is strong, Baal is strong. They bite each other (like) serpents, Mot is strong, Baal is strong.” This image is also used to describe the deadly Anat before she attempts to secure Aqht’s bow. 35 The first sign in line 61 is worn, so we cannot be sure if a verb appears before or after the phrase “his heart like a serpent.” Nonetheless, the mention of Yṭpn’s heart adjacent to the serpent imagery suggests that Pģt deals him a final and deadly blow straight to the heart, like a serpent’s bite, and the act of vengeance is complete.

The last five visible words in line 61 are ṯnm tšqy msk hwt tšqy. 36 We believe that these words close the legend of Aqht. They have been interpreted variously, For example, Wyatt renders them “A second time she gave him mixed wine to drink, she gave him to drink.” 37 Margalit: “She served him spirits a second time, she served him [the intoxicating bevera]ge.” 38 Gibson: “Twice they gave (her) his mixture to drink, they gave (her it) to drink and [.” 39 We accept Parker’s second interpretation: “Twice she drinks the mixed wine, drinks it.” 40 It seems that after the act of vengeance is complete, Pģt takes a couple of victory drinks, 41 as had Yṭpn while previously bragging about his own killings.

concluSion

We have suggested that the legend of Aqht ends with KTU 1.19. Although the last line of the tablet is not well preserved, it is possible to complete the storyline using the evidence we do have. Therefore there is no need to suppose that there is a missing tablet, given that Aqht was buried in all proper ritual and his murder was avenged by his sister. We have pre-sented epigraphic evidence to support this argument. While each piece of evidence by itself may not be convincing enough to prove our argument, when all are taken together, the tablet speaks for itself. We do not reject the possibility that there were once other tablets between KTU 1.17–1.18 and KTU 1.18–1.19, or that KTU 1.20 has provides some indirect context for Dan-ilu’s character, but we have to rely on the existing evidence, at least until further evidence presents itself.

33. For other suggestions see N. Wyatt, Religious Texts from Ugarit: The Words of Ilimilku and His Colleagues, 2nd ed. (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2002), 312 n. 279.

34. KTU 1.6, VI, 17–20.35. See KTU 1.17, VI, 14. See also bṯn as a deadly being in KTU 1.100, 73–76; 1.3, III, 41; 1.5, I, 1. This image

also appears in KTU 1.169, 3, but in a different sense.36. According to CTA, 92, there is a w after the word tšqy, although in fig. 62 it is clearly the letter s. KTU, 62

n. 19 gives (tšqyxs[xx]). From examination of the tablet, it is clear that the letter s does appear on the edge, but it is difficult to reconstruct its proper place or context.

37. Religious Texts from Ugarit, 312.38. See B. Margalit, The Ugaritic Poem of Aqht, 166. It seems that he accepts the opinion of Dijkstra and de

Moor, who restore the letter s on the edge to the word s[m] (“poison”); see M. Dijkstra and J. C. de Moor, “Prob-lematic Passages in the Legend of Aqhatu,” UF 7 (1975): 171–215.

39. See J. C. L. Gibson, Canaanite Myths and Legends, 122.40. See S. B. Parker, “Aqhat,” 78, 80 n. 46. The second interpretation reads tšqy as a verb in D-stem, “she

drinks,” rather than G-stem, “she gives a drink.”41. Or drinks for the second time.