There Is Water Everywhere: How News Framing Amplifies the Effect of Ecological Worldviews on...

Transcript of There Is Water Everywhere: How News Framing Amplifies the Effect of Ecological Worldviews on...

This article was downloaded by: [Hong Kong Baptist University]On: 15 September 2011, At: 19:57Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH,UK

Mass Communication andSocietyPublication details, including instructions forauthors and subscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hmcs20

There Is Water Everywhere:How News Framing Amplifiesthe Effect of EcologicalWorldviews on Preference forFlooding Protection PolicyTimothy K. F. Fung a , Dominique Brossard b &Isabella Ng ca Department of Communication Studies, Hong KongBaptist Universityb Department of Life Science Communication,University of Wisconsin––Madisonc Centre for Gender Studies, University of London

Available online: 09 Sep 2011

To cite this article: Timothy K. F. Fung, Dominique Brossard & Isabella Ng (2011):There Is Water Everywhere: How News Framing Amplifies the Effect of EcologicalWorldviews on Preference for Flooding Protection Policy, Mass Communication andSociety, 14:5, 553-577

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2010.521291

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes.Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan,sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone isexpressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make anyrepresentation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up todate. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should beindependently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liablefor any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damageswhatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connectionwith or arising out of the use of this material.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

There Is Water Everywhere: How NewsFraming Amplifies the Effect of

Ecological Worldviews on Preference forFlooding Protection Policy

Timothy K. F. FungDepartment of Communication Studies

Hong Kong Baptist University

Dominique BrossardDepartment of Life Science Communication

University of Wisconsin–Madison

Isabella NgCentre for Gender Studies

University of London

The purpose of this study is to examine the interactive effect of worldviewsand media frames on policy preference. Using flooding as a case study, we

Timothy K. F. Fung (Ph.D., University of Wisconsin–Madison, 2010) is an Assistant Pro-

fessor in the Department of Communication Studies at Hong Kong Baptist University. His

research interests include risk communication, health communication and cultural influence

on information processing and judgment.

Dominique Brossard (Ph.D., Cornell University, 2002) is an Associate Professor in the

Department of Life Science Communication at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Her

research focuses on the intersection between science, media and policy.

Isabella Ng (M.Phil., Hong Kong Baptist University, 2004) is a doctoral candidate in the

Centre for Gender Studies at the University of London. Her research interests include journal-

ism, gender and media.

Correspondence should be addressed to Timothy K. F. Fung, Department of Communi-

cation Studies, Hong Kong Baptist University, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong. E-mail:

Mass Communication and Society, 14:553–577, 2011Copyright # Mass Communication & Society Division

of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication

ISSN: 1520-5436 print=1532-7825 online

DOI: 10.1080/15205436.2010.521291

553

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

examine the interplay of ecological worldviews and news framed as eitheremphasizing harmony with nature or mastery over nature on individuals’ pref-erence for flood protection policy. A total of 255 undergraduate studentsparticipated in a 2 (ecological worldviews: balance-with-nature vs. human-domination-over-nature)� 2 (media frames: harmony frame vs. masteryframe) between-subjects experiment. The findings indicate that both thebalance-with-nature worldview and the human-domination-over-natureworldview have significant impacts on preference for flood protection policy.Furthermore, the harmony frame amplified the effect of the balance-with-nature worldview in supporting a natural approach to flood protection. Incontrast, the mastery frame amplified the effect of the human-domination-over-nature worldview on the preference for a structural approach to floodprotection. Implications are discussed.

Through media framing efforts, stakeholders on an issue can push their ownagenda in an attempt to influence public opinion and gain support for theirviews (e.g., Lewis, 2005; Saulny, 2007; Walsh, 1993). This is particularlytrue in the case of socially divisive issues. Indeed, research in risk (e.g.,Kahneman & Tversky, 1979), political (e.g., Shah, Kwak, Schmierbach, &Zubric, 2004), and health (Rothman & Salovey, 1997) arenas has demon-strated the potentially powerful effect of media framing in swaying publicattitudes and subsequent judgments. However, scholars have also arguedthat message framing effects are not universal across individuals (Price &Tewksbury, 1997; Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007). Individual differences, interms of values held and levels of political knowledge, for instance, mightinterplay with media framing (Hwang, Gotlieb, Nah, &McLeod, 2007; Shen,2004; Zaller, 1992). Although some have examined the role played by valuepredispositions in moderating media effects (e.g., Brossard, Scheufele, Kim,& Lewenstein, 2008; Domke, Shah, & Wackman, 1998; Shen & Edwards,2005), research has yet to examine the role of worldviews in shaping framingeffects in the context of environmental or risk-related issues. Worldviews arethe core assumptions an individual makes about the nature of the world andabout his or her relationship to the world (Sue, 1981). Because worldviewsare so fundamental, they play a central role in guiding individuals’ thoughts,perceptions, and evaluations about the world (Sodowsky, Maguire, Johnson,Ngumba, & Kohles, 1994). In particular, worldviews about ecological sys-tems (i.e., ecological worldviews) may influence individuals’ positions onenvironmental and risk-related issues such as flooding.

To examine the interacting effect of ecological worldviews and newsframing, we chose flooding protection policy as the context of inquiry.One reason for this selection is that recent floods in the Midwest and hurri-canes in Louisiana (Lydersen, 2008; Saulny, 2008) have revived concerns

554 FUNG, BROSSARD, NG

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

over flooding related risks since Hurricane Katrina hit the southern coast ofthe United States with devastating effects. Another reason is that the debateover what is the best approach to protect communities against floods hasbeen taking place in the public sphere for years, with two clearly definedopposing camps (Ayres, 1993; Janofsky, 1997; Jehl, 2001; Saulny, 2007;Schwartz, 2006). One camp advocates a structural approach, suggestingbuilding stronger and more technologically advanced dams and levees inflood prone areas. The other camp supports a natural approach, relyingprimarily on land management and suggesting the relocation of businessesand houses, to restrict development on flood-susceptible lands, to carveout more overflow areas for flood waters, and to turn the riverbanks backinto natural wetlands capable of soaking up and slowing flood waters toprotect lives and property (Stevens, 1993).

Thepurposeof this study is therefore toexplore the relationshipsbetweeneco-logicalworldviews andmedia frames in affecting individuals’ judgments of floodcontrol policy. Specifically, we examine how the effects of ecological worldviewsare moderated by framing the issue of flooding according to different perspec-tives regarding the nature of the relationship between humans and nature.

ECOLOGICAL WORLDVIEWS

As mentioned earlier, worldviews are sets of core assumptions regardinghow the world works, its perceived effect on human behavior, and humans’place in the universe (Horner & Vandersluis, 1981; Sire, 1976). Others havedescribed them as lay theories about the world (McLeod, Kosicki, &McLeod, 2002), or, as stated by Magee and Kalyanaraman (2009), ‘‘world-views are a chronically accessible collection of core assumptions or beliefs,often unconscious and untested, with which a person makes sense of theworld’’ (p. 4). Worldviews are considered fundamental to human beingsand are acquired through social interactions and socialization processes(Naugle, 2002; Sarason, 1984). In this sense, worldviews tend to be enduringand stable elements of our belief system. As such, these priori assumptionslay the groundwork for knowing and understanding the world and provide aframework that guides our perceptions, our interpretation of the world, andour behaviors (Koltko-Rivera, 2004). As noted by Sire (1976),

[Although] few people have anything approaching an articulate philosophy,everyone has a worldview. . . .Whenever any person thinks anything from acausal thought to a profound question—he or she is operating from such aframework. In fact, it is only the assumption of worldview—however basicand simple—that allows people to think at all. (p. 16)

MEDIA FRAMING AND ECOLOGICAL WORLDVIEWS 555

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

Worldviews can relate to a wide range of domains. Ecological world-views, for instance, are core beliefs regarding the relationship betweenhuman beings and nature (Arcury, Johnson, & Scollay, 1986; Kluckhohn& Strodtbeck, 1961). There are two major and opposed orientations for thisworldview: the human-domination-over-nature worldview versus thebalance-with-nature worldview. The human-domination-over-nature world-view assumes that human beings are disconnected from nature and that theearth and its natural resources exist for the sake of satisfying human needs(McHarg, 1970; Nash, 1989). Under this worldview, progress, growth, andprosperity are highly valued, and science and technology are considered thekeys to human progress that can ultimately lead to human control over nat-ure and to human salvation from natural disasters (Arcury et al., 1986). Thisworldview has dominated American culture for several centuries (Blaikie,1992).

An alternative worldview—the balance-with-nature worldview—hasemerged in the United States in recent decades, in parallel with increasingawareness of environmental problems (Arcury et al., 1986). Under thisworldview, human beings are considered as an intrinsic part of nature ratherthan being superior to nature and exempt from its laws (Dunlap & VanLiere, 1978). When holding this worldview, human beings attempt to under-stand the laws governing the natural world and to recognize the importanceof preserving the balance between human progress and natural settings. Insum, these individuals stress the need for humans to live in harmony withnature.

Dunlap and Van Liere (1978) developed a scale tapping into these twofundamental views about nature and humans relationship. The originalscale was modified later on, relabeled the New Ecological Paradigm scale(Dunlap, Van Liere, Mertig, & Jones, 2002), and validated over the yearsacross studies. Notably, it was shown that these two ecological worldviewsare acquired early in childhood (Van Petegem & Blieck, 2006).

Because ecological worldviews are deeply held, they are likely to play acentral role in the formation of individuals’ environment-related attitudes,behaviors, and judgments. For example, Poortinga, Steg, and Blek (2004)found that ecological worldviews were major determinants of individuals’decisions to engage in energy conservation behaviors and to support govern-mental regulations related to environmental problems. Another studyshowed that ecological worldviews were a significant predictor of recyclingbehavior (Vining & Ebreo, 2006). They were also a significant predictor ofthe willingness to address climate change (O’Connor, Bord, & Fisher, 1999).In addition, ecological worldviews significantly explained the variance inecologically conscious consumer behaviors (Roberts & Bacons, 1997). Inshort, worldviews are chronic dispositions and can provide guidance when

556 FUNG, BROSSARD, NG

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

perceiving and making sense of the world (Koltko-Rivera, 2004). In otherwords, worldviews can be used as cognitive shortcuts (Feldman, 1999;Feldman & Lynch, 1988). A recent study showed that people used world-views as heuristics when interpreting media content and making judgmentsabout products consumptions (Magee & Kalyanaraman, 2007).

As explained earlier, two different approaches have been put forward asbest practices to reduce risks related to floods. Relying on science and tech-nology, the structural approach advocates building dams and levees on floodplains. On the other hand, the natural approach emphasizes regulating landuse to preserve the natural environment so as to reduce flood damage andto protect lives and property. We argue that this long-standing debate height-ens the clash of the two opposing ecological worldviews and ultimatelyexacerbates conflicts in the enactment of flood protection policy. Individualsholding a balance-with-nature worldview might think that dams and leveesrestrain nature and attempt to bend it according to human desires. They,therefore, might prefer the natural approach to flood control. On the otherhand, those holding a human-domination-over-nature worldview mightbelieve in the power of science and technology to thwart destructive naturalforces. These people, thus, might support more a structural approach to floodprotection. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: A balance-with-nature worldview will be a significant predictor of prefer-ence for a natural approach to flood control. As the strength of thebalance-with-nature worldview increases, support for the naturalapproach to flood control will increase.

H2: A human-domination-over-nature worldview will be a significant predic-tor of preference for a structural approach to flood control. As thestrength of the human-domination-over-nature worldview increases,support for a structural approach to flood control will increase.

NEWS FRAMING

By selecting and emphasizing certain aspects of an issue and making themmore salient over others, a news story can influence which thoughts aboutthat issue are activated among audience members (Entman, 1993). As aresult, people can interpret an issue and form judgments about it corre-sponding to the perspective stressed in the news story. The process by whichnews accounts influence individuals’ information processing and social judg-ments has been called framing. Studies have shown that media framing cansignificantly influence individuals’ thoughts and opinions toward varioussocial issues (e.g., Nelson, Clawson, & Oxley, 1997; Price, Tewksbury, &Powers, 1997; Shah, Domke, & Wackman, 2001).

MEDIA FRAMING AND ECOLOGICAL WORLDVIEWS 557

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

Media is a place where different social groups and institutions struggleover the definition and construction of social reality (Gurevitch & Levy,1985). Symbolic contests of meaning are carried out in the media amongcompeting groups. As discussed earlier, framing is commonly used by com-peting groups to push forward the definition and meaning they each give toan issue. In the case of debates over flood control solutions, supporters ofboth the structural approach, which advocates the use of science and tech-nology to combat flood damage, and of the natural approach, which advo-cates the restoration and protection of the environment, may frame thehumans–nature relationship in a way that favors their own position in orderto gain public support. This framing can take place by associating ecologicalworldviews and flood control measures. For instance, flood control solu-tions can be framed as being in harmony with nature by characterizingthe relationship between humans and their natural environment as sym-biotic and by stressing the importance for humans of living harmoniouslywith nature (harmony frame). In contrast, flood control solutions can beframed as a way to achieve mastery over nature by highlighting the needfor natural forces of all kinds to be overcome and to be put to use for humanbeings (mastery frame). When news readers are exposed to these differentnews frames, this might trigger different frame-related thoughts and, as aresult, influence the formation of different attitudes toward flood controlpolicy.

However, a growing body of research has shown that frames do notalways shape the way in which an individual interprets or understands anissue, the framing effect is more likely to occur if the frame is resonant withthe individual’s existing schema (e.g., Hwang et al., 2007; Shen, 2004; Shen& Edwards, 2005; Shah, 2001). The underlying mechanism is explicated bythe applicability model of framing effects (Price & Tewksbury, 1997). Assuggested by Price and Tewksbury (1997), each individual possesses aunique set of existing knowledge constructs in his or her memory. The acti-vation of a particular knowledge construct at any time depends on certaincharacteristics such as its chronic and temporary accessibility, as well asthe salient attributes of the current situation. When an individual is exposedto a news story emphasizing a certain aspect of an issue, the activation ofrelevant frame-related thoughts by the news frame is dependent on theextent to which the information and message featured in the news framematch the knowledge construct held by the individual (Higgins, 1996; Price &Tewksbury, 1997). The more the knowledge construct and the newsframe resonate with each other, the more likely the news frame will renderthe knowledge construct applicable for issue interpretation. As a result, theknowledge construct is more likely to influence subsequent decision makingand judgment. Therefore, as Price et al. (1997) put it, through media framing

558 FUNG, BROSSARD, NG

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

‘‘salient attributes of a message (its organization, selection of content, orthematic structure) render particular thoughts applicable, resulting in theiractivation and use in evaluation’’ (p. 486). In this sense, audiences are notpassively influenced by a media message. Rather, they actively interpret rel-evant information in the media message to make subsequent judgments(Hwang et al., 2007). Therefore, news framing and individual schema maywork jointly in influencing individuals’ judgments.

Empirical studies have provided evidence supporting the interactionbetween audience schema and media frames. For example, Keum and col-leagues (2005) conducted a study of the effect of individual and societalnews framing on concerns for security and tolerance judgment. Newsemphasizing restrictions of individuals’ civil liberties augmented the effectof political ideology (an individual schema) on security concerns and toler-ance, whereas news framed in terms of restriction of group-level libertiesundermined the effect of political ideology on security concern and toler-ance. Shen and Edwards (2005) conducted another study examining theeffects of individuals’ values (i.e., humanitarianism and individualism) andmedia framing on attitudes toward welfare reform. In their study, respon-dents were exposed to a news article emphasizing the need for either publicassistance or strict work requirement. The results showed that individuals’values and media frames jointly influenced individuals’ thoughts andattitudes toward welfare reform.

Although some may put forward the concept of priming as the explana-tory mechanism of how news frames interact with individual preexistingknowledge constructs, the premises of framing and priming are different(Scheufele, 2000). The theoretical foundation of priming is based on accessi-bility (Scheufele, 2000; Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007). That is to say, theconcept of priming is built upon a memory-based model of information pro-cessing (Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007). According to the memory-basedprocessing model, individual attitudes and judgments depend on how avail-able and retrievable information is from the memory. In other words, prim-ing posits that media can make certain issues or certain aspects of an issueeasily brought to mind and, therefore, can influence the standards audienceuse when forming attitudes and judgments about social issues. As discussedearlier, the concept of framing, however, is based on applicability. It denotesthe ‘‘goodness of fit’’ between the salient attributes in the message and anindividual’s knowledge constructs (Higgins, 1996). Framing effects, thus,take place through the ‘‘match’’ between a media frame and an individual’spreexisting knowledge construct. Price and Tewksbury (1997) also notedthat the timing of influence is another major distinction between the appli-cability and the accessibility effects. During message processing, salientattributes render knowledge constructs applicable. They are then more likely

MEDIA FRAMING AND ECOLOGICAL WORLDVIEWS 559

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

to be used in evaluations and judgments. On the other hand, once a knowl-edge construct has been activated, it retains an activation potential and ismore likely to be activated and used for ensuing evaluations and judgments.The applicability effect refers to the immediate influence of a particularmessage on issue evaluation at the time of message processing (or immedi-ately following), whereas accessibility refers to the influence of activatedthoughts on subsequent evaluations and judgments. In short, framing andpriming are two distinct concepts.

The issue of flood control policy is particularly relevant to the examin-ation of a potential interaction between news frames and worldviews. Sup-port for either the structural approach or the natural approach maydepend on the ecological worldview an individual holds and on howstrongly he or she subscribes to that particular worldview. News coveringthe issue of flood control policy, which frames the humans–nature relation-ship in terms of harmony with nature, may be more appealing to thosewho hold a balance with nature worldview, and vice versa. In addition,the resonance between an individual’s predisposed ecological worldviewand a media frame may result in cognitive assonance, whereas the mis-match of a predisposed ecological worldview and a media frame may leadto cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957). For instance, individuals whohold a balance-with-nature worldview may experience cognitive dissonancewhen they are exposed to media content emphasizing human mastery overnature because there is a discrepancy between what they believe and theinterpretation of flooding suggested by the news frame. On the contrary,these individuals may experience cognitive assonance when they areexposed to media content emphasizing harmony with nature. As a conse-quence, they will be more likely to support a natural approach to floodcontrol. Building on this argument, we hypothesize that news framingmay amplify or attenuate the influence of ecological worldviews on thepreference for flood control policy. More specifically, a news story stres-sing humans’ harmonious relationship with nature may enhance the influ-ence of the balance-with-nature worldview on the support for a naturalapproach to flood control. Likewise, a news story framing the human–nat-ure relationship in terms of human mastery over nature will intensify theeffect of the human-domination-over-nature worldview. Thus, we positthe following hypotheses:

H3: News framing moderates the influence of ecological worldviews:(a) A harmony frame will amplify the effect of the balance-with-nature

worldview in supporting a natural approach to flood control.(b) A mastery frame will augment the effect of a human-domination-over-

nature worldview in supporting a structural approach flood control.

560 FUNG, BROSSARD, NG

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

METHOD

Design and Procedure

The hypotheses were tested by a 2 (media frames: harmony vs. mastery)� 2(ecological worldviews: balance-with-nature vs. human-domination-over-nature) between-subjects factorial design. The data in this study were col-lected using an experiment embedded in a web-based survey. Respondentsenrolled in undergraduate courses at a large midwestern university wereoffered extra credit for participating in this study. A total of 255 respon-dents (63% nonscience majors; 55.7% female; M age¼ 21 years,SD¼ 3.14) completed the survey. Respondents first answered a set of ques-tions measuring their ecological worldviews, embedded in other survey ques-tions. Upon completion of the pretest questions, respondents were randomlyassigned to the two framing conditions. Each respondent read a news articleregarding the debate over flood control policy and framed in terms of eithermastery over nature or harmony with nature (the order of presentation ofthe structural approach and of the natural approach to flood control in eachnews story was controlled for). After reading the news article, respondentsthen filled out a posttest questionnaire. Each session took about 25 minutes.

Stimulus Material

The stimuli materials (i.e., newspaper articles) were based on real newscoverage of the issue. Both articles provided some background informationon the flood issue, followed by the presentation of the structural approachand the natural approach to flood control. In the harmony-with-natureframing condition, the headline read, ‘‘A Call To Stop Flooding: WorkWith Nature.’’ It stressed the importance of working in coordination withnatural conditions. In addition, a direct quote from a hydrologist was used:‘‘Humans and nature are interdependent like Yin and Yang. Land manage-ment that works in harmony with nature is the best way to deal with flood-ing.’’ It presented the relationship between humans and nature as symbiotic.The headline in the mastery over nature framing condition read, ‘‘A Call ToStop Flooding: Work With Technology.’’ It emphasized the use of scienceand technology to overcome natural forces. A direct quote from the samehydrologist stated, ‘‘Levees and dams are like great fortresses. These struc-tures, a product of science, technology and human determination, are thebest way to deal with flooding.’’ It stressed the use of science and technologyas the main mean to control nature for the benefits of humankind.

The structure of both news articles consisted of a core section oftwo paragraphs with background information on the issue of flooding.

MEDIA FRAMING AND ECOLOGICAL WORLDVIEWS 561

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

These were followed by another core section of four paragraphs introduc-ing the structural and natural approaches to flood control. The head-line and the concluding paragraph were designed to set up one of the twoframes in each experimental condition. Both articles had the same length.The major differences of the news articles in the two conditions werethe pull-out quotes, headlines, and the direct quotes in the concludingparagraph.

Measures

Ecological worldviews. The strength of ecological worldviews wasmeasured with the New Ecological Paradigm scale (Dunlap et al.,2002). A principal component factor analysis with direct oblimin rotationwas employed to identify underlying dimensions. Two factors wereextracted, which explained 49.07% of the total variance. The first factor,labeled as balance-with-nature, consisted of six items and explained36.64% of the variance (M¼ 7.66, SD¼ 1.65). The second factor, labeledas human-domination-over-nature, consisted of six items and explained12.44% of the variance (M¼ 5.02, SD¼ 1.31). The Cronbach’s alphawas .81 for the first factor and was .72.1 for the second factor (see theappendix).

Preference for flood control policy. This variable was an additive indexof five items that asked respondents to rate their agreement on a 11-pointscale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree (see the appendix).A principal component factor analysis with direct oblimin rotation wasperformed to explore the underlying dimensions of the flood control mea-sures. Two factors were extracted, which explained 78.64% of the totalvariance. The first factor consisted of three items of flood control measuresand explained 49.82% of the variance. It was labeled ‘‘natural approach’’(M¼ 7.15, SD¼ 1.73) and had a Cronbach’s alpha of .79. The secondfactor was composed of two items in the flood control measures andexplained 28.82% of the variance. This factor was labeled ‘‘structuralapproach’’ (M¼ 6.72, SD¼ 2.15) and produced an interitem correlationof .78.

Control variables. Even in an experimental design with random assign-ment to conditions, controls help ensure that an experimental treatment is

1By convention, obtaining an alpha of .80 or higher is representative of a good scale. An

alpha at least .70 or above is considered acceptable (George & Mallery, 2003).

562 FUNG, BROSSARD, NG

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

not confounded with other factors in accounting for criterion variables(Keppel & Wickens, 2004; Kirk, 1995). According to a review of the litera-ture (Fransson & Garling, 1999), gender and rural-urban residency can becovariates of environmental values. Therefore, we controlled for these twovariables. Rural-urban residency was measured with a single item on11-point scale ranging from rural to urban (see the appendix). Because levelsof knowledge about a specific issue can influence individuals’ responses tomedia frames, issue knowledge was used as a control variable and was mea-sured on a 11-point scale ranging from not knowledgeable at all to veryknowledgeable (see the appendix).

Research has shown that media use can have a significant impact onenvironmental beliefs and concerns (e.g., Holbert, Kwak, & Shah, 2003;Shanahan, 1993; Shanahan & McComas, 1999; Shanahan, Morgan, &Stenbjerre, 1997). Therefore, we included media use as a control variable.Media attention was measured with a 11-point scale ranging from not atall to a great deal of attention. Media exposure was measured with 11-pointscale ranging from none to very often (see the appendix).

It has also been pointed out that people with high levels of political trustare more favorable to governmental actions addressing environmental prob-lems (Konisky et al., 2008). Political trust, hence, was included in our con-trol variables. It consisted of four items, and these items were measured by a11-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree (see theappendix). The Cronbach’s alpha was .76.

Finally, and specifically for our sample of college students, it wasimportant to control for participants’ study majors because they mighthave influenced how participants perceived the relationship betweenhuman beings and nature. Research has shown that academic disciplinesare related to environmental attitudes and actions (Ewert & Baker,2001). Students majoring in social sciences may have had more opportu-nities to be exposed to environmental-protection-related issues and corre-sponding literature. For instance, history students may take courses inenvironmental history (Jurin & Hutchinson, 2005). Students majoringin business administration may be exposed to topics of sustainability andcorporate responsibility. Courses such as environmental journalism=communication may be available to mass communications students. Onthe other hand, students majoring in the hard sciences such as physics,chemistry, or engineering may be more likely to be exposed to coursesemphasizing a mastery over nature. For example, students majoring in bio-technology may learn how to modify the genome of plants to increase foodproductivity and improve food quality. Thus, ‘‘academic major’’ wastreated as a control variable. It was coded into a dummy variable (1 forscience majors and 0 for nonscience majors).

MEDIA FRAMING AND ECOLOGICAL WORLDVIEWS 563

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

Analytical Approach

As suggested by Cohen, Cohen, West, and Aiken (2003), the primary analy-ses consisted of multiple regressions with the experimental conditions (har-mony frame vs. mastery frame), the balance-with-nature worldview, thehuman-domination-over-nature worldview, and their interactions as inde-pendent variables. This multiple regression approach allowed for an optimaluse of the balance-with-nature worldview and the human-domination-over-nature worldview variables, which were operationalized in our study as con-tinuous variables. In contrast to an analysis of variance approach, theregression approach prevented us from forcing these variables into artificialdichotomizations, a process that would have led to a loss of associated infor-mation (Cohen et al., 2003). Therefore, the two ecological worldviews weretreated as continuous variables through a regression approach and were notdichotomized into any specific groups (e.g., low vs. neutral vs. high groups)as traditionally done when using an analysis of variance approach (Cohenet al., 2003). In addition, these regression analyses facilitated tests of mod-eration involving ecological worldviews and media frames. Media frameswere dummy coded (mastery frame coded as 1, and harmony frame codedas 0), and the two ecological worldviews were mean-centered.

There were two primary sets of regression analyses. In the first set ofregression analyses, preference for a natural approach to flood controlwas the dependent variable. This first equation was used to test H1 andH3a. In the second regression analysis, preference for a structural approachto flood control was the dependent variable. This second equation was usedto test H2 and H3b.

In these analyses, the control variables were entered in a first block, fol-lowed by a second block consisting of the two ecological worldviews, adummy variable of media frames, and the Worldviews�Media Framesinteraction terms. The regression equations results provided us with assess-ments of the main effect of worldviews and of the interaction effects betweenworldviews and media frames.

RESULTS

Preference for the Natural Approach as Flood Control Solution

Participants’ preference for the natural approach was regressed on the con-trol variables, the balance-with-nature worldview, the human-domination-over-nature worldview, the media frames, and the Worldviews�MediaFrames interactions. The overall regression model was significant,R2¼ .30, F(11, 237)¼ 9.19, p< .001. As expected, the balance-over-nature

564 FUNG, BROSSARD, NG

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

worldview had a significant influence on preference for a natural approach,B¼ .29, t(237)¼ 4.52, p< .001. The balance-with-nature worldviewaccounted for 7.84% of the unique variance in preference for a naturalapproach to flood control (sr¼ .28), with one unit increase in balance-of-nature worldview associated with a .29 units increase in preference for anatural approach. Therefore, H1 was supported.

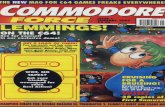

H3a predicted a Balance-With-Nature Worldview by Harmony Frameinteraction effect. The findings showed that the Balance-With-NatureWorldview by Harmony Frame interaction was significant B¼�.49, sr¼�.15), t(237)¼�2.37, p< .05, suggesting that the effect of balance-with-nature worldviews varied by media frames. The effect of the balance-with-nature worldview was .49 units more positive for individuals who wereexposed to the harmony frame compared to those who were exposed tothe mastery frame. This also indicates that the regression slopes of indivi-duals holding a balance-with-nature worldview significantly differedbetween those who were exposed to a harmony frame and a masteryframe. Figure 1 shows two separate regression slopes for the individuals

FIGURE 1 The interaction effect of balance-with-nature worldview by media frames on

preference for a natural approach.

MEDIA FRAMING AND ECOLOGICAL WORLDVIEWS 565

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

holding a balance-with-nature worldview who were exposed to a harmonyframe and a mastery frame, respectively. Put differently, as the strength oftheir balance-with-nature worldview increased, individuals who wereexposed to a harmony frame were .49 units more supportive of the naturalapproach of flood control policy than those who were exposed to a masteryframe.

The simple effect of the balance-with-nature worldview for individualswho were exposed to the harmony frame was significant B¼ .43,t(237)¼ 4.13, p< .001. The effect of a balance-with-nature worldviewfor individuals who were exposed to the harmony frame was .43 unitshigher in supporting a natural approach to flood control. H3a was there-fore supported. On the other hand, the simple effect of the balance-with-nature worldview for individuals who were exposed to the masteryframe was not significant B¼ .14, t(237)¼ .13, ns. This suggests thatthe mastery frame did not attenuate the effect of the balance-with-natureworldview on the preference for a natural approach to flood control (seeTable 1).

TABLE 1

Effect of Control Variables, Ecological Worldviews, and Media Frames on Preferences for a

Natural Approach to Flood Control

Eq. 1 Eq. 2 Eq. 3

Variables B b B b B b

Control variables

Male .27 .08 .21 .06 .27 .08

Attention to environmental news .33��� .47��� .24��� .35��� .25��� .35���

TV news exposure �.02 �.03 �.01 �.01 �.02 �.02

Visit Internet news sites .03 .05 .03 .05 .04 .06

Info. searching on the Internet �.06 �.09 �.03 �.05 �.06 �.09

Academic majors in sciences .18 .05 .29 .08 .33 .21

Worldviews and media frames

Balance-with-nature worldview .29��� .28��� .43��� .41���

Human-domination-over-nature

worldview

.05 .04 .09 .07

Mastery frame �.17 �.05 �.18 �.05

Interactions

Balance-With-Nature

Worldview�Mastery Frame

�.49� �.19�

Human-Domination-Over-Nature

Worldview�Mastery Frame

�.09 �.03

�p< .05. ���p< .001.

566 FUNG, BROSSARD, NG

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

Preference for a Structural Approach as Flood Control Solution

Participants’ preference for a structural approach to flood control wasregressed on control variables, balance-with-nature worldview, human-domination-over-nature worldview, media frames, and Worldviews�Media Frames interactions. The overall regression model was significantR2¼ .21, F(12, 236)¼ 5.17, p< .001.

As expected, a significant effect of human-domination-over-natureworldview on preference for a structural approach was observed B¼ .43,t(236)¼ 4.11, p< .001. Human-domination-over-nature worldview accoun-ted for 6.76% of the unique variance in preference for a structural approach(sr¼ .26), with a one unit increase in human-domination-of-nature world-view associated with a .44-units increase in preference for a structuralapproach. Therefore, H2 was supported.

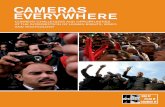

As hypothesized, as the strength of human-domination-over-natureworldview increased, individuals who were exposed to the mastery framewere more likely to support a structural approach to flood control thanthose who were exposed to the harmony frame. As predicted, a significantHuman-Domination-Over-Nature Worldview�Mastery Frame interactionwas observed B¼ .58, sr¼ .13, t(236)¼ 2.00, p< .05, suggesting that theeffect of human-domination-of-nature worldview varied by media frames.The effect of human-domination-of-nature worldviews was .58 units morepositive for individuals who were exposed to the mastery frame than forthose who were exposed to the harmony frame. In other words, the effectof media frames was increased by .58 units for every one unit increase inhuman-domination-over-nature worldview. This also implied that the reg-ression slopes for the individuals holding human-domination-over-natureworldview significantly differed between those who were exposed to theharmony frame and the mastery frame. Figure 2 shows the slopes for eachframe condition. Put differently, as the strength of the human-domination-over-nature worldview increased, individuals who were exposed to themastery frame were .58 units more supportive of a structural approach toflood control policy than those who were exposed to the harmony frame.

The simple effect of human-domination-over-nature worldview for indi-viduals who were exposed to the mastery frame was significant B¼ .66,t(236)¼ 4.25, p< .001. The effect of a human-domination-over-natureworldview for individuals who were exposed to the mastery frame was.66 units higher in supporting structural approach to flood control. H3bwas therefore supported. On the other hand, the simple effect of human-domination-over-nature worldview for individuals who were exposed tothe harmony frame was not significant B¼ .25, t(236)¼ 1.81, ns. Thisrevealed that the harmony frame did not undermine the effect of

MEDIA FRAMING AND ECOLOGICAL WORLDVIEWS 567

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

human-domination-over-nature worldview on the preference for a structur-al approach to flood control (see Table 2).

Additional Findings

Among the control variables, attention to environmental news was signifi-cant in predicting preference for flood control policy. More specifically,a significant positive effect of attention to environmental news on preferencefor a natural approach to flood control was observed B¼ .33, t(242)¼7.50, p< .001. It accounted for 18.83% of the variance in preference for anatural approach (sr¼ .43), with a one unit increase in attention to environ-mental news associated with a .33-units increase in preference for a naturalapproach (see Table 1). Conversely, a significant negative effect of attentionto environmental news on support for a structural approach of flood controlpolicy B¼�.19, t(236)¼�2.59, p< .01, was observed. It accounted for2.89% of the variance in support for a structural approach (sr¼�.17), with

FIGURE 2 The interaction effect of human-domination-over-nature worldview by media

frames on preference for structural approach.

568 FUNG, BROSSARD, NG

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

a one unit increase in attention to environmental news associated with a.19-units decrease in support for a structural approach (see Table 2). Thesefindings are consistent with previous studies examining the relationshipbetweenmedia use and environmental attitudes (e.g., Shanahan&McComas,1999; Shanahan et al., 1997).

Students’ academic major was another variable significantly predictingflood control policy preference. A statistically significant difference betweensciences and nonsciences majors on support for a structural approach offlood control policy was observed (B¼�.71, sr¼�.16), t(241)¼�2.12,p< .05. The mean difference between the two groups was .71 units. In otherwords, students who were nonsciences majors were less likely to support astructural approach to flood control policy as compared to those who weremajoring in the hard sciences (see Table 2). However, there was no signifi-cant difference between sciences and nonsciences majors as far as supportfor a natural approach to flood control policy B¼ .18, t(242)¼ .81, ns (seeTable 1). To assess whether there was an interactive effect of students’majors by media frames on flood control policy preferences, we conducted

TABLE 2

Effect of Control Variables, Ecological Worldviews, and Media Frames on Preferences

for a Structural Approach to Flood Control

Eq. 1 Eq. 2 Eq. 3

Variables B b B b B b

Control variables

Attention to environmental news �.19� �.22� �.13 �.15 �.14 �.16

Attention to national politics .09 .10 .09 .10 .10 .11

Attention to international affairs .14 .16 .11 .13 .12 .14

Knowledge about flooding �.06 �.07 �.12� �.13� �.12� �.14�

Rural-urban residency .06 .11 .06 .11 .06 .11

Political trust .15 .11 .12 .09 .13 .10

Academic majors in sciences �.71� �.16� �.61� �.14� �.59� �.13�

Worldviews and media frames

Balance-with-nature worldview .05 .04 .07 .05

Human-domination-over-nature

worldview

.43��� .26��� .25 .15

Mastery frame �.44 �.10 �.43 �.10

Interactions

Balance-With-Nature

Worldview�Mastery Frame

�.05 �.02

Human-Domination-Over-Nature

Worldview�Mastery Frame

.58� .17�

�p< .05. ���p< .001.

MEDIA FRAMING AND ECOLOGICAL WORLDVIEWS 569

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

a multivariate analysis of variance, with media frames and students’ majorsas the independent variables and the two flood control policy preferences asthe dependent variables. The overall multivariate F test for media frames bystudents’ majors interaction was not significant, F(2, 250)¼ 1.89, ns. Thissuggests that students’ majors and media frames did not jointly influenceflood control policy preference.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of our study was to examine the interplay of ecological world-views and news framing in making judgments related to environmentalpolicy. Based on an experimental design, we explored how stories framedin terms of mastery over nature versus stories framed in terms of harmonywith nature might impact individuals’ preference for specific flood controlsolutions. We also explored the role played by ecological worldviews injudgment making and the potential interactive effect of these worldviewsand media frames. As expected, we found that media frames and ecologicalworldviews worked jointly in influencing individuals’ judgments related toenvironmental policy.

Before we discuss our findings in greater details, we need to acknowledgesome limitations of this study. First, we relied on a sample of college students.College students, of course, are likely to differ from the general populationfor some attitudinal and behavioral variables. This raises the question ofwithin-sample variation for some of our variables. Notably, the mean scoreof the balance-with-nature worldview of our sample was 7.66 on an 11-pointscale (SD¼ 1.65), whereas the mean score of the human-domination-over-nature worldview of our sample was 5.02 (SD¼ 1.31). This result is consistentwith Dunlap and colleagues (2002), who noted that younger people are morelikely to score higher on the balance-with-nature worldview than the tra-ditional worldviews of human-domination-over-nature. Our sample henceshowed less variation than the general population on this variable. Thisimplies that some of the relationships we report are actually attenuated, com-pared to what we would find from the general population. Future researchshould attempt to replicate our study with the general population.

In addition, this study used the single issue of flood control whenexamining the effect of media frames and ecological worldviews on policypreferences. Future research should explore other environmental risk issuesin order to expand our understanding of the processes at play and thegeneralizability of our results.

Despite these limitations, our findings have important theoretical andpractical implications. It is worthwhile pointing out that our findings

570 FUNG, BROSSARD, NG

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

supported our hypotheses. Specifically, ecological worldviews significantlyinfluenced individuals’ preference for a specific flood control policy. Inother words, the level of support for natural approach to flood controlincreases as the level of the balance-with-nature worldview increases. In con-trast, the level of support for structural approach to flood control increasesas the level of the human-domination-over-nature worldview increases.

More important, we found significant interactive effects of media framesand ecological worldviews. That is, the effect of ecological worldview wasqualified by media frames. The effect of a balance-with-nature worldviewon preference for a natural approach to flood control was amplified whenindividuals were exposed to the harmony-with-nature news frame, com-pared to the mastery-over-nature news frame. In the similar vein, the influ-ence of the human-domination-over-nature worldview on preference forstructural approach was amplified when individuals were exposed to themastery-over-nature news frame, compared to the harmony-with-naturenews frame. In contrast, there was no significant impact on policy prefer-ence when media frames did not match individual’s ecological worldviews.

Our findings suggest that media frames and ecological worldviews workjointly in influencing individuals’ judgments related to environmental pol-icy. Ecological worldviews appear to be an important factor in makingjudgments related to environmental issues. In fact, this finding is not parti-cularly surprising in light of the literature on environment and attitudes.What is most intriguing here is that harmony framing amplified the effectof balance-with-nature worldview, whereas mastery framing amplified theeffect of human-domination-over-nature worldview. In the case of environ-mental issues, media frames tend to amplify individuals’ deeper convictionsrelated to the relationship between humans and nature. Given their beliefsthat human beings are intrinsic components of nature, individuals who wereexposed to news stories emphasizing a harmonious relationship betweenhumans and nature through a harmony frame, became even more likelyto stand up for a natural approach to flood control. On the other hand, indi-viduals who believed in the control of nature became even more supportiveof a structural approach to flood control. One could therefore argue thatmedia frames may polarize public opinion on the flood control issue (Keumet al., 2005). Research in ecological worldviews of college students (Bechtel,Corral-Verdugo, Asai, & Riesle, 2006; Bechtel, Corral-Verdugo, & Pinheiro,1999; Corral-Verdugo & Armendariz, 2000) found that college students’environmental beliefs in the United States are dichotomized. In other words,American college students perceive a clear-cut distinction between thebalance-with-nature and human-dominance-over-nature worldviews andperceived these two worldviews as conflicting with each other. Collegestudents might even consider the two worldviews as polarized opposites

MEDIA FRAMING AND ECOLOGICAL WORLDVIEWS 571

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

(Jurin & Hutchinson, 2005). In fact, the views of our sample on ecologicalworldviews were consistent with these previous studies, with the two ecologi-cal worldviews being negatively correlated in our study (r¼�.48, p< .001).

In sum, the polarization of public opinion about environmental policythat might be encouraged by news framing may aggravate the dichotomousincompatibility between the two worldviews. As a consequence, this polar-ization may deepen the continuing disagreement on environmental policyrather than foster the search for a mutual-agreed-upon solution throughthoughtful discussions and deliberations in media arenas. A more nuancedview of nature encompassing the need for a natural balance and for aresponse to human needs may be more beneficial to our sustainable devel-opment (Corral-Verdugo & Armendariz, 2000; Goodland, 1995).

This study makes theoretical contributions to news framing research. Weshow a connection between ecological worldviews and media frames. Thisconfirms the moderating role of news framing stressed in past studies(Hwang et al., 2007; Keum et al., 2005; Shen & Edwards, 2005) and high-lights the need to take into account worldviews when assessing effects ofmedia frames. The media frames produced contingent effects in relationto ecological worldviews. That is, when media frames resonate with one’secological worldview, the influence of ecological worldviews is likely to beintensified. Conversely, there was no significant influence on flood controlpolicy preference when a media frame and an individual’s preexisting eco-logical worldview did not resonate. In other words, audiences are less likelyto be affected when a media frame does not match an individual’s world-view. As a consequence, the unfitted media frame is less likely to be usedfor issue interpretation. Our study confirms the active role of audiences,with individuals bringing their own chronically accessible interpretive fra-meworks (i.e., ecological worldviews) when processing media messagesrelated to the environment. In other words, ecological worldviews are likelyto have a vital influence in guiding individuals’ interpretations of environ-mental issues. Meanwhile, predisposed ecological worldviews may alsodirect individuals on how to make sense of mediated messages and their cor-responding frames. If the media-induced humans-nature relations newsframe is in concert with an individual’s ecological worldview, the news frameenhances the preexisting individual ecological worldview, leading to a sup-port for an ecological worldview-consistent policy. In other words, thecontingent effect of worldviews and media frame highlighted in this studyprovides empirical support for the applicability model (Price & Tewksbury,1997; Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007). An activated construct will be used forissue interpretation if there is resonance between the news frame and predis-posed worldviews. An inapplicable media frame is less likely to be used forinterpretation.

572 FUNG, BROSSARD, NG

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

The findings in this study not only provide theoretical insights forframing theory but also offer practical implications for campaigns planningrelated to environmental issues particularly in the area of messages con-struction. As we showed, framing effects take place only when the framesused fit within the preexisting repertoire of individuals’ worldviews. Cam-paign practitioners, thus, should identify the ecological worldviews of theirtarget audience and then frame the issue consistently. In this case, messageframing may enhance audiences’ preexisting ecological worldviews andfoster support for the policy advocated. In contrast, if the frame used forthe environmental issue is inconsistent with audiences’ ecological world-views, the campaign message is less likely to have significant influence onaudiences’ attitudes toward the environmental policy advocated.

REFERENCES

Arcury, T. A., Johnson, T. P., & Scollay, S. J. (1986). Ecological worldview and environmental

knowledge: The new environmental paradigm. Journal of Environmental Education, 17,

35–40.

Ayres, B. D. (1993, July 12). The Midwest flooding; Dams and levees: Restraint on nature or

talisman for flood-prone areas. The New York Times. Retrieved from Lexis-Nexis

Universe: General News Topics database.

Bechtel, R. B., Corral-Verdugo, V., Asai, M., & Riesle, A. G. (2006). A cross cultural study of

environmental belief structures in USA, Japan, Mexico, and Peru. International Journal of

Psychology, 41, 145–151.

Bechtel, R., Corral-Verdugo, V., & Pinheiro, J. (1999). Environmental belief systems: United

States, Brazil and Mexico. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 30, 122–128.

Blaikie, N. (1992). The nature and origins of ecological worldviews: An Australian study. Social

Science Quarterly, 73(1), 144–165.

Brossard, D., Scheufele, D., Kim, E., & Lewenstein, B. (2008). Religiosity as a perceptual filter:

examining processes of opinion formation. Public Understanding of Science, 17(4), 1–13.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S., & Aiken, L. (2003). Applied multiple regression=correlation

analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Corral-Verdugo, V., & Armendariz, L. I. (2000). The new environmental paradigm in a

Mexican community. Journal of Environmental Education, 31, 25–31.

Domke, D., Shah, D. V., & Wackman, D. B. (1998). Media priming effects: Accessibility,

association, and activation. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 10, 51–74.

Dunlap, R. E., & Van Liere, K. D. (1978). The ‘‘new environmental paradigm’’: A proposed

instrument and preliminary results. Journal of Environmental Education, 9, 10–19.

Dunlap, R. E., Van Liere, K. D., Mertig, A. G., & Jones, R. E. (2002). New trends in measuring

environmental attitudes: Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised

NEP scale. Journal of Social Issues, 56, 425–442.

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of

Communication, 43(4), 51–58.

Ewert, A., & Baker, D. (2001). Standing for where you sit: An exploratory analysis of the

relationship between academic major and environment beliefs. Environment and Behavior,

33, 687–707.

MEDIA FRAMING AND ECOLOGICAL WORLDVIEWS 573

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

Feldman, J. M. (1999). Four questions about human behavior: The social cognitive approach to

culture and psychology. In J. Adamopoulos & Y. Kashima (Eds.), Social psychology and

cultural context (pp. 43–62). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Feldman, J. M., & Lynch, J. G. (1988). Self-generated validity and other effects of measurement

on belief, attitude, intention and behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 73, 421–435.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson.

Fransson, N., & Garling, T. (1999). Environmental concern: Conceptual definitions, measure-

ment methods, and research findings. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 19, 369–382.

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference.

11.0 update (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Goodland, R. (1995). The concept of environmental sustainability. Annual Review of Ecology

and Systematics, 26, 1–24.

Gurevitch, M., & Levy, M. (1985). Mass communication review yearbook, 5. Beverly Hills, CA:

Sage.

Higgins, E. T. (1996). Knowledge activation: Accessibility, applicability, and salience. In

E. T. Higgins & A. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles

(pp. 133–168). New York: Guilford.

Holbert, R. L., Kwak, N., & Shah, D. (2003). Environmental concern, patterns of television

viewing, and pro-environmental behaviors: Integrating models of media consumption and

effects. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 47, 177–196.

Horner, D., & Vandersluis, E. (1981). Cross-cultural counseling. In G. Althen (Ed.), Learning

across cultures (pp. 30–50). Washington, DC: National Association of Foreign Student

Affairs.

Hwang, H., Gotlieb, M., Nah, S., & McLeod, D. (2007). Apply a cognitive-processing model to

presidential debate effects: Post debate news analysis and primed reflection. Journal of

Communication, 57, 40–59.

Janofsky, M. (1997, March 19). Flood-control policy shift is meeting scant success. The New

York Times, pp. A16.

Jehl, D. (2001, April 27). Mississippi flooding is reviving a debate on government role. The New

York Times. Retrieved from Lexis-Nexis Universe: General News Topics database.

Jurin, R., & Hutchinson, S. (2005). Worldviews in transition: Using ecological autobiographies

to explore students’ worldview. Environmental Education Research, 11, 485–501.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk.

Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291.

Keppel, G., & Wickens, T. (2004). Design and analysis: A researcher’s handbook (4th ed.).

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Keum, H., Hillback, E., Rojas, H., De Zuniga, H., Shah, D., & McLeod, D. (2005). Personify-

ing the radical: How news framing polarizes security concerns and tolerance judgment.

Human Communication Research, 31, 337–364.

Kirk, R. E. (1995). Experimental design. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks=Cole.

Kluckhohn, F. R., & Strodtbeck, F. L. (1961). Variations in value orientations. Evanston, IL:

Row & Peterson.

Koltko-Rivera, M. E. (2004). The psychology of worldviews. Review of General Psychology,

8(1), 3–58.

Konisky, D. M., Milyo, J., & Richardson, L. E. (2008). Environmental policy attitudes: Issues,

geographical scale, and political trust. Social Science Quarterly, 89(5), 1066–1085.

Lewis, R. K. (2005, September 17). Using technology to combat nature has environmental and

economic costs. The Washington Post. Retrieved from Lexis-Nexis Universe: General News

Topics database.

574 FUNG, BROSSARD, NG

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

Lydersen, K. (2008, April 6). Flood season begins unusually early across heartland. The

Washington Post. Retrieved from Lexis-Nexis Universe: General News Topics database.

Magee, R. G., & Kalyanaraman, S. (2009). Effects of worldview and mortality salience in

persuasion processes. Media Psychology, 12, 171–194.

McHarg, I. L. (1970). Value, process, and form. In R. Disch (Ed.), The ecological consciences

(pp. 21–36). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Erlbaum.

McLeod, D. M., Kosicki, G. M., & McLeod, J. M. (2002). Resurveying the boundaries of polit-

ical communications effects. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in

theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 215–67). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Nash, R. F. (1989). The rights of nature. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Naugle, D. (2002). Worldview: The history of a concept. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Nelson, T. E., Clawson, R. A., & Oxley, Z. M. (1997). Media framing of a civil liberties conflict

and its effect on tolerance. American Political Science Review, 91, 567–583.

O’Conner, R., Bord, R., & Fisher, A. (1999). Risk perceptions, general environmental beliefs,

and willingness to address climate change. Risk Analysis, 19, 461–471.

Price, V., & Tewksbury, D. (1997). News values and public opinion: A theoretical account of

media priming and framing. In G. A. Barnett & F. J. Boster (Eds.), Progress in communi-

cation sciences: Advances in persuasion, 13 (pp. 173–212). Greenwich, CT: Ablex.

Price, V., Tewksbury, D., & Powers, E. (1997). Switching trains of thought: The impact of news

frames on readers’ cognitive responses. Communication Research, 24, 481–506.

Poortinga, W., Steg, L., & Blek, C. (2004). Values, environmental concern and environmental

behavior: A study into household energy use. Environment and Behavior, 36(1), 70–93.

Roberts, J. A., & Bacon, D. R. (1997). Exploring the subtle relationship between environmental

concern and ecologically conscious consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 40(1),

79–89.

Rothman, A. J., & Salovey, P. (1997). Shaping perceptions to motivate healthy behavior: The

role of message framing. Psychological Bulletin, 121(1), 3.

Sarason, S. B. (1984). If it can be studied or developed, shouldn’t it be?. American Psychologist,

39, 477–485.

Saulny, S. (2007, May 15). Trusting in levees, St. Louis area builds on flood plains. The New

York Times. Retrieved from Lexis-Nexis Universe: General News Topics database.

Saulny, S. (2008, June 16). In Midwest floods, a broad threat to Crops. The New York Times.

Retrieved from Lexis-Nexis Universe: General News Topics database.

Scheufele, D. A. (2000). Agenda-setting, priming, and framing revisited: Another look at cog-

nitive effects of political communication. Mass Communication and Society, 3, 297–316.

Scheufele, D. A., & Tewksbury, D. (2007). Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution

of three media effects models. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 9–20.

Schwartz, J. (2006, April 1). The dilemma of the Levees. The New York Times, pp. A12.

Shah, D. V. (2001). The collision of convictions: Value framing and value judgments. In R. P.

Hart & D. Shah (Eds.), Communication and U.S. elections: New agendas (pp. 57–74).

Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Shah, D. V., Domke, D., & Wackman, D. B. (2001). The effects of value-framing on political

judgment and reasoning. In S. D. Reese, J. O. H. Gandy, & A. E. Grant (Eds.), Framing pub-

lic life: Perspectives on media and our understanding of the social world (pp. 227–243). Mah-

wah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Shah, D. V., Kwak, N., Schmierbach, M., & Zubric, J. (2004). The interplay of news frames on

cognitive complexity. Human Communication Research, 30, 102–120.

Shanahan, J. (1993). Television and the cultivation of environmental concern: 1988–92. In A.

Hansen (Ed.), The mass media and environmental issues (pp. 181–197). Leicester, UK:

Leicester University Press.

MEDIA FRAMING AND ECOLOGICAL WORLDVIEWS 575

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

Shanahan, J., & McComas, K. (1999). Nature stories: Depictions of the environment and their

effects. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton.

Shanahan, I., Morgan, M., & Stenbjerre, M. (1997). Green or brown? Television and the cul-

tivation of environmental concern. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 47, 305–323.

Shen, F. (2004). Effects of news frames and schemas on individuals’ issue interpretations and

attitudes. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 81, 400–416.

Shen, F., & Edwards, H. (2005). Economic individualism, humanitarianism, and welfare

reform: A value-based account of framing effects. Journal of Communication, 55, 795–809.

Sire, J. W. (1976). The universe next door. Downing Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press.

Sodowsky, G., Maguire, K., Johnson, P., Ngumba, W., & Kohles, R. (1994). Worldviews of

White Americans, Mainland Chinese, Taiwanese and African Students: An investigation into

between-group differences. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 25, 309–324.

Stevens, W. K. (1993, July 20). The high risks of denying their flood plains. The New York

Times. Retrieved from Lexis-Nexis Universe: General News Topics database.

Sue, D. W. (1981). Counseling the culturally different: Theory and practices. New York: Wilsey.

Van Petegem, P., & Blieck, A. (2006). The environmental worldview of children: A cross-

cultural perspective. Environmental Education Research, 12, 625–635.

Vining, J., & Ebreo, A. (2006). Predicting recycling behavior from global and specific environ-

mental attitudes and changes in recycling opportunities. Journal of Applied Social Psychology,

22, 1580–1607.

Walsh, E. (1993, August 7). Along the Lower Mississippi, optimism abounds about flood;

Residents rely on federal levee system and river’s changing nature. Washington Post.

Retrieved from Lexis-Nexis Universe: General News Topics database.

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York: Cambridge University

Press.

APPENDIX: QUESTION ITEMS

Balance-with-nature worldview (a¼ .81)

The earth has very limited room and resources.

We are approaching the limit of the number of people the earth can support.

Humans are severely abusing the environment.

Plants and animals have as much right as humans to exist.

If things continue on their present course, we will soon experience a major ecological

catastrophe.

The balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset.

Human-domination-over-nature worldview (a¼ .72)

We have the right to modify the natural environment to suit our needs.

Human ingenuity will ensure that we do NOT make the earth unlivable.

The balance of nature is strong enough to cope with the impacts of modern industrial nations.

We are meant to rule over nature.

The so-called ecological crisis mankind are facing has been greatly exaggerated.

The earth has plenty of natural resources only if we learn how to develop them.

Natural approach to flood control policy (a¼ .79)

How much do you agree or disagree with relocation of houses and businesses as flood control

policy?

576 FUNG, BROSSARD, NG

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011

How much do you agree or disagree with restoration of natural wetlands as flood control

policy?

How much do you agree or disagree with restricting development on flood-susceptible land as

flood control policy?

Structural approach to flood control policy (a¼ .78)

How much do you agree or disagree with building technologically advanced (e.g., nervous

systems of electronic sensors) dams and levee as flood control policy?

How much do you agree or disagree with building higher dams and levee as flood control

policy?

Rural-urban residency

What is the best description of the place where you are currently living?

Issue knowledge

How knowledgeable would you say you are about flood control?

Media exposure

How often do you use each of the following types of media content?

Newspapers

Television news programs (local and national)

Search for information about current events on the Internet

Visit Internet news sites (e.g., NYTimes.com)

Media attention

Apart from how often you consume these types of content, how much attention do you pay to:

News stories about national politics

News stories about international affairs

News stories about environmental issues

Political trust (a¼ .76)

Do you think that people in the government waste a lot of money we pay in tax?

Would you say the government is pretty much run for the benefit of all the people?

Would you say the government is pretty much run by a few big interests looking out for

themselves?

How much of the time do you think you can trust the government in Washington to do what is

right?

MEDIA FRAMING AND ECOLOGICAL WORLDVIEWS 577

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Hon

g K

ong

Bap

tist U

nive

rsity

] at

19:

57 1

5 Se

ptem

ber

2011