The Variety of Religious Experiences

Transcript of The Variety of Religious Experiences

THE VARIETY OF RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCES

JOSEPH O. BAKERBAYLOR UNIVERSITY

REVIEW OF RELIGIOUS RESEARCH 2009, VOLUME 51(1): PAGES 39-54

The primary effort of this study is to help move sociological studies of religious expe-rience out of the realm of abstract theory and into quantitative analysis. While thisis certainly not the first study to do this, the breadth of experiences assessed by the2005 Baylor Religion Survey provides more detailed information on the topic thanhas previously been presented. Results indicate that over 65% of American adultsclaim to have had at least one of the religious experiences assessed. The differentsocio-demographic patterning found among specific experiences indicates that usinga broad, all-encompassing question to analyze religious experiences is inadequate.A theoretical distinction is also proposed between experiences involving only feel-ings and those extending to other sensory sensations such as seeing, speaking, hear-ing, or healing. While income level does not influence claiming more normativereligious experiences of feeling, it is an important predictor of more intense, deviantreligious experiences.

INTRODUCTION

Despite increasing interest, religious experience remains a concept that suffers frompoor conceptualization, operationalization, and measurement in sociology. Under-lying these difficulties is the problem of defining religious experience satisfactori-

ly, a problem whose solution has eluded many scholars of religion in theology, the humanities,and the social sciences alike (Poloma 1995:166).

There is a distinctive commonality found within much of the scholarly work attemptingto study, classify, or describe religious experiences. Researchers often admit that investi-gating religious experiences can be similar to grasping sand, since “the normal require-ments for scientific research, such as objectivity, systematization, and exactitude, are noteasily adaptable in any kind of experience-related research” (Tamminen and Nurmi 1995:274-75). Defining the object of study can be daunting as well because a “precise referent of‘religious experience’ is elusive” (Yamane 1998:179). No matter how thorough the con-ceptualization process or in-depth the information received from people claiming to havesuch experiences, there always remains an element of the unseen. Along with the difficul-ty of definition and measurement, those having religious experiences claim to be in con-tact with, to borrow a phrase from Smith (2003), the “super-empirical.” Consequently, thehuman side of this human-divine relationship can be studied, but researchers must acceptthat the “divine” end of the connection is a concept ontologically beyond the grasp ofresearch (Tamminen and Nurmi 1995). Thus, research methods can never definitively assert

39

that someone did or did not have a prophetic vision. When investigation focuses on gener-al feelings of a supernatural presence, there is no way to determine what such a broad,closed-ended survey response means (Thomas and Cooper 1978). When in-depth data areobtained from individuals concerning their experiences of the divine, no classificationscheme is extensive enough to make sense of the immense variety of experiences, althoughsome have tried (see Hardy 1979). When the focus is placed on dramatic experiences, thereis the implication that the divine can be found in the mundane (Yamane 1998). Academicanalysis is always a sieve that allows certain aspects of religious experience to pass throughunacknowledged. However, difficulty of conceptualization should not deter investigation.While recognizing these limitations, there are great strides to be made in the sociologicalstudy of religious experiences, especially in the realm of quantitative analysis.

Religious experiences provide fertile ground for academic inquiry for a number of rea-sons. Primary among these are the amount of people claiming to have such experiences.High estimates for the proportion of people claiming religious experiences range from36.4% in Britain (Hay and Morisy 1978) to 50% in the U.S. (Wuthnow 1978). Further, thereare indications that the claiming of religious experiences has become more prevalent, withGallup polls reporting 20.5% responding affirmatively in 1962 and 48% responding affir-matively in 1987 (Beit-Hallahmi and Argyle 1997). Wuthnow claims that “virtually every-one appears to have [peak experiences] of one kind or another” (1978:73). Of course theseproportions and figures hinge on how religious experiences are defined and on the popula-tion that is examined. Moreover, these figures are now dated and need to be supplemented.Nevertheless, the prevalence of people claiming to have directly experienced the divine isimpressive.

In addition to volume, experiential facets of religion constitute an important aspect ofreligiosity that has personal and institutional consequences (Poloma 1995), especially sincereligious experiences serve to increase believers’ confidence in religious explanations (Starkand Finke 2000). While different religious traditions and groups place varying emphasis onthe experiential dimension, all religions assign import to religious experiences as a form ofreligiosity (Glock and Stark 1965). Early social scientists took this notion seriously, view-ing religious belief as resting on religious experience (Durkheim [1912] 1995; James [1902]1961). Despite early interest, this line of research was ignored until the latter half of the20th century. Thus, while experiences of the divine are generally accepted as an aspect ofreligion, only a small number of scholars “have done more than pay it lip service” (Polo-ma 1995:170).

Researchers have more recently shown more interest in the experiential facet of religion,realizing that in addition to being a vital component of studying religion, experiences haveprofound consequences for the rest of an individual’s life (Spilka, Brown, and Cassidy1992). Nevertheless, sociologists have often failed to assess the topic with methodologicalprecision (inasmuch as this is possible). Paramount among methodological problems isemploying a single, broad survey question for use in quantitative analysis. The types ofexperiences that people claim vary widely, and condensing these into a single question leadsto confusing results.1

The primary goal of this study is be to analyze social factors (specifically income andeducation) that influence who claims various types of religious experiences. In addition,specific types of religious experience will be analyzed separately to determine if a higher

40

Review of Religious Research

degree of specificity is necessary on survey questions addressing the topic. If all types ofexperiences have similar socio-demographic predictors, then a single question may sufficebecause of similarity in the social patterning of those claiming religious experiences. How-ever, if there are substantial differences among social factors influencing experiences, thencondensing various types of experiences into one question is inadequate. I will utilize datafrom Wave I of the Baylor Religion Survey to investigate these issues.

“Grasping” Religious ExperiencesPart of the difficulty in conceptualizing religious experiences arises from the radically

subjective nature of “experiencing.”Yamane explains that all that scholarly inquiry can actu-ally study is the linguistic representation of experience. He claims researchers must let goof the idea of examining experience directly and acknowledge the limitations that accom-pany studying linguistic representations. Scholars should “instead give our full attention tothe primary way people concretize, make sense of, and convey their experiences” (2000:176).This raises an important consideration for studying any type of experience in that it is onlyrepresentations of experience that can be studied (outside of monitoring biofeedback of theexperience itself). If people do not define their own experience as “speaking in tongues”then they will not report their experience as such. Consequently a certain amount of meas-urement error must be expected when dealing with experience. Moreover, there is signifi-cant diversity in religious experiences that leads to problems in definition, classification,and study (Batson, Schoenrade, and Ventis 1993).

Much of the work in the social sciences on religious experiences is built on ideas posit-ed by William James ([1902] 1961), who contends that there are no exclusively religiousemotions but rather natural emotions directed toward “the religious.” Framing religiousemotion in this way yields two benefits. First, it provides a basic understanding of why sim-ilarities exist between religious experiences across various faith traditions—because thesame principal emotions undergird all experience. Second, differences between experiencesacross faith traditions can be better understood because those who have had such experi-ences make sense of them within the context of their own faith. Consequently Catholics areapt to report visions of the Virgin Mary whereas Jews are not. The process of labeling andassigning meaning to experience also extends to the delineation between religious and “mun-dane” experiences.

Proudfoot (1985) asserts that the difference between dramatic religious and mundaneexperiences centers around where the agent attributes the source of the experience. Hedescribes an instance of recalling an image of the Virgin Mary in his mind, which is con-trasted with a person who believes that he has had a prophetic “vision” of the Virgin Mary.The difference in the two experiences lies in where each subject attributes the source oftheir respective image. In essence, what defines a religious experience is the type of expla-nation applied to the experience rather than the content of the experience itself (Proudfoot1985). Here the importance of social forces is evident in creating meaning and determin-ing which type of explanation a person will select.

Correlates and Antecedents of Religious ExperiencesAlthough quantitative sociological analysis of religious experiences is rare, there are

some studies. Yamane and Polzer (1994) conducted a binary logistic regression analysis to

41

The Variety of Religious Experiences

assess who was likely to claim an ecstatic experience. They found that male and unmarriedrespondents were more likely to claim an ecstatic experience when controlling for religiousvariables. Interestingly they also included a scale of occupational prestige in their models.Respondents with less prestigious jobs were more likely to claim ecstatic experiences beforeincluding religious controls; however, after including these controls, occupational prestigewas no longer significant.

Poloma and Pendleton (1989) found that the strongest predictors of religious experi-ences within the Assemblies of God denomination were private devotional practices suchas frequency of prayer and reading religious scripture. They also demonstrated that partic-ipation in religious services (such as Sunday school and worship) were not significant pre-dictors of a scale of religious experiences that included glossolalia, prophecy, and miraclehealing.

The connection between age and religious experiences is currently ambiguous. Hay(1987) found that older people were more likely to claim religious experiences, while Levin(1993) found that the effects of age upon experiences are dependent upon the type of expe-rience in question. The types of experiences analyzed in Levin’s study represented a mixof secular and religious mysticism; so a definitive age pattern has yet to be determined. Ithas also been suggested that women are more likely to have religious experiences than men(Hay 1987; Poloma 1995), although this is debated (see Yamane and Polzer 1994). Whilenot the direct focus of this study, age and gender could be necessary control variables.

A fundamental shortcoming of previous empirical studies is the tendency to treat alltypes of experience as the same. This results in the more prevalent types of experience over-whelming rarer and more deviant experiences in the dependent variable. In other words ifthere are fifty respondents claiming to have been “filled with the spirit” for every one claim-ing to have religious visions, the latter has very little impact on the dependent variable andtherefore on the overall analysis. Separate analyses of specific types of experience can helpimprove our understanding of these phenomena.

Religious Experiences, SES, and Stakes in ConformityGoing back to James ([1902] 1961), there has been an attempt to understand religious

experiences as a resolution of psychological discontent. Starbuck discusses personal prob-lems as being precursors to religious experiences (1899). Boisen (1936) follows this lineof thought with an account of his own experience with mental illness and the relief pro-vided by religious experience. More recent research has added to this understanding thatreligious experiences may be influenced by difficult life circumstances and that people lookfor answers outside the material world (Spilka et al. 1992). In addition, people who claimto have “peak experiences” are more likely to report living a meaningful, purposeful life(Wuthnow 1978).

Previous work by Chaves (2004) on congregational worship styles found evidence thatpeople of lower socioeconomic status are more likely to select worship styles that are effu-sive and openly emotive. Among the activities more likely to be found in congregationswhere members were of lower socioeconomic standing were “people speak in tongues” and“people testify/speak about religious experience” (2004:135). This provides preliminaryevidence that individuals of lower SES may be more likely to seek religious rewards thatare more emotionally charged, including intense religious experiences, than those of high-er social standing, which tend toward a more reserved and reverent form of worship.

42

Review of Religious Research

Direct contact with the divine provides an experience that literally transcends the mate-rial world, and in this transcendence there are benefits that cannot be achieved throughmaterial means, including psychological health, a sense of peace, the feeling of a purpose-ful life, or increased certainty in religious faith. However, different types of experience offervarying levels of reward to an actor. An analogy can be drawn to religious groups. Starkand Bainbridge (1987) contend that the higher tension a religious group is in with the sur-rounding socio-cultural environment, the more efficacious the intrinsic reward for partici-pating in the group—so too it would be with religious experiences. Feeling “filled with thespirit” would not provide the same sense of confidence in a religious explanation that hav-ing a religious vision would. The greater efficacy rewarded by the latter would be relatedto the higher social cost incurred by claiming such an experience.

If certain religious experiences incur more cost and higher levels of commitment, thentheories of deviance are applicable in explaining who is likely to claim such experiences.Toby articulated the concept of “stakes in conformity,” which refers to the extent to whichan individual is invested in conformist behavior (1957). Stakes in conformity indicate thata person has more to lose by engaging in deviant behavior (Vold, Bernard, and Snipes 1998).Stakes in conformity are also at the heart of Hirschi’s formulation of control theory (1969);the idea is that the stronger a person’s ties are to the conventional social order, the less like-ly one is to deviate

In order to establish such a theoretical framework for examining more deviant types ofreligious experiences, there must be some method of delineating experiences as deviant ornormative (or at least socially acceptable). Clearly this is an area of theoretical ambiguityand difficulty. Given the relativity of deviance depending on the social setting, some typesof experience such as “speaking in tongues” may be deviant in the broader culture, but quiteexpected within a certain denomination. As Glock and Stark (1965) illustrate through anaccount of H.L. Mencken’s observation of a charismatic Appalachian church (1956), it wasactually the stoic sociologist quietly observing, rather than the participants, who was beingdeviant during the church service. However, within the context of the broader culture in theUnited States, some forms of religious experiences are more deviant than others—and thisis the context that will be used to delineate some experiences as more deviant than others.

One of the primary delineations between normative and deviant in this regard is a reli-gious experience involving senses beyond “feeling.” Examples would include speaking (e.g.glossalalia), seeing (e.g. prophetic visions), or hearing (e.g. voices). Another deviant expe-rience in American culture would be miraculous healing, especially given the cultural relianceon modern science and medicine as the predominant paradigm used to explain and treat ill-ness. The most common and acceptable form of religious experience is a “feeling” of thedivine. This can range from a general feeling of God’s presence to feeling called to act incertain ways. In most cases within the United States, claiming such experiences would notbe considered unusual. “Feelings” of the divine tend to be amorphous and exclusively pri-vate. They are part and parcel of religion’s domain, whereas experiences that are more con-crete, involving sight, sound, and healing, may be outwardly visible to others, making themmore open to refutability and doubt. These types of experience also defy the “laws” of thematerial world, placing them at a greater distance from the mainstream culture and its faithin science as the most powerful explanatory tool. The forthcoming analyses will examinethis distinction between claiming religious experiences that deal only with feelings of thedivine and those that include sensory responses beyond “feelings.”

43

The Variety of Religious Experiences

HYPOTHESIS

It is expected that individuals with low stakes in conformity will have more to gain andless to lose by pursuing more intense and deviant religious experiences as rewards. Hencethe hypothesis: People at lower levels of income and education will be more likely to claimmore deviant religious experiences (those beyond feeling). Specifically these deviant reli-gious experiences will be claiming to have religious visions, speaking in tongues, hearingthe voice of God, and witnessing or experiencing a miraculous healing.

DATA AND METHODS

The data analyzed are taken from Wave I of the Baylor Religion Survey, which was field-ed in 2005 by the Gallup Organization using a mixed mode sampling design. A nationalrandom sample of phone numbers was used in the initial phase to contact 7,041 potentialrespondents potential respondents, with 3,002 agreeing to participate. Some were given abrief phone interview and 2,603 were mailed a sixteen page survey booklet. A five dollarincentive was included with the mailed surveys. Some 1,721 surveys were returned for ageneral response rate of 24.4% and 46.5% for the mailed survey phase. While the overallresponse rate is low due to the mixed methods sampling design, the demographic resultsof the BRS compare favorably to the General Social Survey (Bader, Froese and Mencken2007). Further information on the data collection process and comparison of the resultswith the GSS can be found in Bader et al. (2007). Gallup also weighted the data for race,gender, region of the country, age, and education. All forthcoming analyses employ thisweight.

Self-report and the Subjective Nature of ExperienceGiven that the data used for this study are taken from a mail survey, whether or not an

individual claims to have had a religious experience is left to the discretion of the respon-dent. In other words, the respondent must classify the private experience in the manneroffered by the response options in order to give an affirmative response. This issue recallsthe difficulty of proper definition discussed previously in that there is a radically subjec-tive component inherent to religious experiences. The experience of one person “hearingthe voice of God” may be vastly different from the experience of another responding thesame way. The similarity lies in how each person defines the experience. The responseoptions essentially provide templates for classification so that the respondents themselvesclassify their experiences in certain ways. While speaking in tongues may be a differentexperience for different people, so long as each classifies the experience in the same way,then as a watermark of the spiritual life, that individual has “spoken in tongues.” Thus, whilethe experience itself may differ radically, the labeling and categorization process serves toimbue and convey meaning to the individual and others about the religious experience. Itis then, as Yamane (2000) suggests, the labeling process that occurs after the experiencethat is studied here rather than experiencing itself.

How Common are Religious Experiences?The primary advantage afforded by accessing data from the BRS is that it uses multiple

questions on a wide range of religious experiences. As noted above, much of the priorresearch conducted on religious experiences used broad or vague questions. Yamane and

44

Review of Religious Research

Polzer (1994) point out that previous survey questions include: “Have you ever as an adulthad the feeling that you were somehow in the presence of God?” (Stark 1965); “Would yousay that you have ever had a ‘religious or mystical experience’—that is a moment of sud-den religious awakening or insight?” (Back and Bourque 1970); “How often have you…feltas though you were very close to a powerful, spiritual force that seemed to lift you out ofyourself” (Greeley 1974); and “During your lifetime have you ever had the feeling that youwere in close contact with something holy or sacred?” (Wuthnow 1978). Surveys differentfrom these mentioned above that included a question on religious experiences primarilyused copies of the questions shown (Yamane and Polzer 1994). They elicit a high percent-age of positive responses, but it is often unclear what types of experiences people are claim-ing. Given the aforementioned variety in types of religious experiences, more specificquestions provide a valuable step toward improving the existing understanding of ecstaticexperiences defined as religious and in determining if different types of experiences havedifferent socio-demographic patterns.

A battery of questions, divided into two sections, is devoted to gathering data on reli-gious experiences on the BRS. In the first section respondents are instructed to “indicatewhether or not you have ever had any of the following experiences.” Answer choices areyes and no. The following statements are posed: “I witnessed or experienced a miraculous,physical healing”; “I spoke in tongues at a place of worship”; “I personally had a vision ofa religious figure while awake”; “I felt called by God to do something”; “I heard the voiceof God speaking to me”; “I had a dream of religious significance”; and “I had a religiousconversion experience.” The question for the second section asked, “Have you ever had anexperience where you felt that…” with the questions being: “you were filled with the spir-it”; and “you were in a state of religious ecstasy.” Answer choices are again yes and no.

These questions provide quantitative information on a wide variety of religious experi-ences. Simple frequencies offer new information on the topic and give insight into how per-vasive or rare these types of phenomena are in the United States. Therefore it is informativeto present descriptive statistics on these questions. Frequencies are listed in descending

45

The Variety of Religious Experiences

Table 1: Frequency Reporting Having Various Religious Experiences

Experience % Answering “Yes”

Felt filled with the spirit 52.1

Felt called by God to do something 39.6

Had a religious conversion experience 27.2

Had a dream of religious significance 23.9

Witnessed or experienced miraculous, physical healing 23.0

Heard the voice of God speaking to me 14.8

Felt you were in a state of religious ecstasy 14.8

Spoke in tongues at place of worship 6.4

Had a vision of religious figure while awake 5.7

Those claiming at least one experience 65.9

Source: Baylor Religion Survey

N=1721

order, with the most common experience listed first. The final percentage represents thoseclaiming at least one of the experiences on the list. With 65.9% claiming at least one expe-rience, it is apparent that not only do a majority of individuals in the United States claimto have had some type of religious experience, but also that including all these experiencesin the same variable would lead to a great deal of measurement error for attempting to ana-lyze the less common experiences.

Independent VariablesIncome is measured in categories such that 1≤$10,000, 2=$10,001 to $20,000, 3=$20,001

to $35,000, 4=$35,001 to $50,000, 5=$50,001 to $100,000, 6=$100,001 to $150,000, and7>$150,000. Other socio-demographic variables in the model include education, age, mar-ital status, gender, region of the country, and race. Marital status (married=1), gender(female=1), region (south=1), and race (white=1) are all coded as dummy variables. Thereference group is non-married, non-white males living in a region of the U.S. outside ofthe south. Age is a continuous variable ranging from 18 to 93. Education is measured inattainment categories from 1 (less than high school diploma) to 7 (postgraduate degree).

Religious ControlsMultiple controls are included for religious participation and religiosity. Frequency of

prayer is measured with a variable ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (several times a day). A stan-dard church attendance variable is included with answer choices from 1 (never attend) to7 (attend more than once a week). A question addressing Biblical literalism is used withchoices such that 1 (the Bible is an ancient book of history and legends), 2 (The Bible con-tains some human error), 3 (The Bible is perfectly true, but it should not be taken literally,word-for-word. We must interpret its meaning), and 4 (The Bible means exactly what itsays. It should be taken literally, word-for-word, on all subjects).

Given that religious traditions differ in their encouragement or acceptance of religiousexperiences as part of worship (Chaves 2004), it is important to control for religious tradi-tion. This is done using the RELTRAD classification scheme (Steensland, Park, Regnerus,Robinson, Wilcox, and Woodberry 2000). This schematic separates religious tradition inthe United States into Evangelical Protestants, Mainline Protestants, Black Protestants,Catholics, Jews, religious other, and no religion. For the current analysis Evangelical Protes-tants are used as the reference category. Furthermore, the RELTRAD coding employedaggressive recovery of missing cases by classifying individuals using denomination andcongregation (see Dougherty, Johnson, and Polson 2006). For the regression analysis onthe question about hearing the voice of God, the results for Jewish respondents are exclud-ed because none of them claimed this experience.

RESULTS

Binary logistic regression models were conducted on the nine specific experiences includ-ed in Table 1. Table 2 contains specific experiences expected to be more normative. With-in this normative group the experiences are listed from the most common (feeling filledwith the spirit) to the least common (feeling a state of religious ecstasy). Table 3 containsthe experiences delineated as more deviant. These are also listed from most common (mirac-ulous healing) to least common (religious visions).

46

Review of Religious Research

47

The Variety of Religious Experiences

Ta

ble

2:

Res

ult

s fr

om

Bin

ary

Lo

gis

tic

Reg

ress

ion

of

Sp

ecif

ic R

elig

iou

s E

xp

erie

nce

sO

dd

s R

atio

s P

rese

nte

d w

ith

Sta

nd

ard

Err

ors

in

Par

enth

eses

F

ille

d

Cal

led

R

elig

iou

s

Rel

igio

us

Var

iab

les

w/S

pir

it

b

y G

od

C

on

ver

sio

n

D

ream

E

csta

sy

So

cio

dem

og

rap

hic

s

I

nco

me

.99

3 (

.05

2)

1.0

43

(.0

54

).9

78

(.0

59

).8

92

(.0

52

)*.9

06

(.0

61

)

E

du

cati

on

.97

0 (

.04

7)

1.0

77

(.0

47

)1

.11

9 (

.05

2)*

1.1

23

(.0

46

)*1

.00

1 (

.05

5)

F

emal

e.8

06

(.1

37

).9

87

(.1

38

)1

.04

1 (

.15

4)

.84

5 (

.13

7)

.71

6 (

.16

4)*

A

ge

.98

8 (

.00

4)*

*.9

84

(.0

04

)**

*.9

92

(.0

05

).9

83

(.0

04

)**

*.9

92

(.0

05

)

W

hit

e.6

73

(.2

23

).7

90

(.2

25

)1

.27

8 (.

25

9)

.56

1 (

.21

3)*

*.5

88

(.2

46

)*

S

ou

th.9

17

(.1

46

).7

29

(.1

48

)*1

.27

8 (

.15

5)

1.0

46

(.1

43

)1

.18

6 (

.16

7)

M

arri

ed1

.38

8 (

.15

1)*

1.1

07

(.1

54

)1

.11

1 (

.17

2)

.87

8 (

.15

2)

.79

3 (

.18

2)

Rel

igio

sity

A

tten

dan

ce1

.08

7 (

.02

9)*

*1

.11

0 (

.02

9)*

**

1.2

02

(.0

33

)**

*1

.04

2 (

.03

0)

1.0

90

(.0

37

)*

F

req

. o

f P

ray

er1

.64

9 (

.04

9)*

**

1.8

17

(.0

54

)**

*1

.38

7 (

.06

0)*

**

1.2

76

(.0

52

)**

*1

.22

5 (

.06

6)*

*

L

iter

alis

m1

.46

1 (

.08

0)*

**

1.4

32

(.0

86

)**

*1

.75

1 (

.10

4)*

**

1.2

19

(.0

86

)*1

.40

6 (

.11

1)*

*

RE

LT

RA

D

C

ath

oli

c.5

41

(.1

84

)**

*.6

11

(.1

91

)*.1

24

(.2

60

)**

*1

.29

5 (

.19

1)

.50

6 (

.26

8)*

B

lack

Pro

test

ant

1.2

34

(.3

95

)1

.55

3 (

.37

6)

.90

2 (

.37

7)

1.2

20

(.3

39

)1

.40

8 (

.36

4)

M

ain

lin

e1

.06

3 (

.18

1)

1.2

39

(.2

14

).4

19

(.1

96

)**

*1

.16

3 (

.18

7)

1.0

15

(.2

21

)

J

ewis

h.3

23

(.4

81

)*.1

92

(.6

17

)**

.23

3 (

.64

2)*

.62

5 (

.55

3)

.48

9 (

.71

9)

R

elig

iou

s o

ther

1.7

71

(.3

22

).7

66

(.3

19

)1

.95

3 (

.31

9)*

2.1

60

(.2

95

)**

2.4

69

(.3

30

)**

N

o r

elig

ion

.76

1 (

.29

1)

1.0

44

(.3

30

).8

15

(.3

72

).7

10

(.4

23

).9

73

(.3

92

)

R2

(Neg

elk

erk

e).3

85

.39

6.4

38

.14

7.1

78

N=

14

14

**

* P

≤.0

01

*

* P

≤.0

1

* P

≤.0

5

So

urc

e: 2

00

5 B

aylo

r R

elig

ion

Su

rvey

Table 2 shows that income level does not have a significant influence on the experiencesof “being filled with the spirit,” feeling “called by God,” having a “religious conversionexperience,” and feeling a “state of religious ecstasy.” Income level does have an impacton one of the more normative experiences such that each unit increase in income levelresults in a 10.8% decrease in the odds of claiming a dream of religious significance. It isunclear what the substantive difference between “filled with the spirit” and “religious ecsta-sy” is for respondents, but the former was much more common than the latter. A differencein terminology is the most likely source, as the term “ecstasy” has a more secular conno-tation in that it can be caused by nature, music, or sex (Beit-Hallahmi and Argyle 1997).Further, according the schematic developed by Glock and Stark (1965), an ecstatic expe-rience is second in intensity only to a revelatory experience. In any case, it is clear that thisterminology has a different meaning for respondents than “being filled with the spirit.”

Income level was a significant predictor of all four of the more deviant experiences. Aone unit increase in income level results in a 25.3% decrease in the odds of claiming to wit-ness or have a miraculous healing. In addition to the deviance of claiming this experience,there is a practical reason for this finding in that people with less income have less accessto the medical system in the United States—thereby increasing the need for miraculoushealing. Certainly all people can face medical problems beyond the help of conventionalmedicine, but in general those at lower income levels will be more in need of alternativesources of healing. A one unit increase in income level results in a 17.4% decrease in theodds of claiming to hear the voice of God, a 26.8% decrease in the odds of claiming tospeak in tongues at a place of worship, and a 32.7% decrease in the odds of claiming a reli-gious vision. Counter to the hypothesis based on stakes in conformity, education level isnot a consistent predictor of those likely to claim deviant religious experiences. Further,where education level is significant for claiming religious visions, it has a positive effect.

Among measures of religiosity, frequency of prayer was a strong and consistent pre-dictor for all of the experiences analyzed. In fact, frequency of prayer is the only variablethat is significant in all of the models. Biblical literalism also exerts a consistent influence,being statistically significant for eight of the nine experiences analyzed. By contrast atten-dance at religious services is significant in five of the nine models and only one of the mod-els examining more deviant experiences. These findings are similar to Poloma and Pendleton’s(1989) in that private religiosity was a better predictor of religious experiences than atten-dance at religious services.

Age is significant in three of the five more normative experiences analyzed. In all cases,younger respondents are more likely to claim the experience than older respondents. Thisis unusual assuming that all ages have an equal chance of having religious experiences. Ifthis assumption were true then older respondents should be more likely to claim many ofthe experiences simply by virtue of being alive longer, and consequently, having moreopportunity to have experiences. Hay found that older people were more likely to reportreligious experiences and stated that “one obvious explanation…is that the longer some-body lives, the more likely they are to have had one of these experiences” (1987:125). How-ever, the current findings indicate that the opposite is occurring in contemporary America.The question then becomes whether or not this is a cohort (cultural) or life-cycle effect. Itis unlikely that individuals would be willing to claim a religious experience while youngand not when older. It is more plausible that this is the result of cultural influences onyounger cohorts.

48

Review of Religious Research

49

The Variety of Religious Experiences

Tab

le 3

: R

esu

lts

fro

m B

inar

y L

og

isti

c R

egre

ssio

n o

f S

pec

ific

Rel

igio

us

Ex

per

ien

ces

Od

ds

Rat

ios

Rep

ort

ed w

ith

Sta

nd

ard

Err

ors

in

Par

enth

eses

Mir

acu

lou

s

Vo

ice

Sp

ok

e in

Rel

igio

us

Var

iab

les

Hea

lin

g

o

f G

od

To

ng

ues

Vis

ion

So

cio

dem

og

rap

hic

s

I

nco

me

.74

7 (

.05

7)*

**

.82

6 (

.06

6)*

*.7

32

(.0

91

)**

*.6

73

(.0

95

)**

*

E

du

cati

on

.99

6 (

.05

0)

1.0

37

(.0

59

).9

95

(.0

80

)1

.17

3 (

.08

1)*

F

emal

e.8

42

(.1

49

)1

.17

0 (

.17

9)

1.2

98

(.1

52

).6

62

(.2

48

)

A

ge

1.0

06

(.0

04

).9

89

(.0

05

)*1

.00

1 (

.00

7)

.99

2 (

.00

7)

W

hit

e.5

25

(.2

34

)**

.78

6 (

.28

5)

.81

4 (

.38

9)

.32

7 (

.32

1)*

**

S

ou

th1

.03

2 (

.15

4)

1.2

63

(.1

77

).9

01

(.2

38

).7

55

(.2

73

)

M

arri

ed1

.25

2 (

.16

9)

1.1

28

(.1

99

)1

.21

5 (

.27

2)

.75

8 (

.28

2)

Rel

igio

sity

A

tten

dan

ce1

.10

8 (

.03

3)*

*1

.03

1 (

.03

9)

1.0

41

(.0

53

).9

94

(.0

54

)

F

req

. o

f P

ray

er1

.50

8 (

.06

1)*

**

1.8

06

(.0

85

)**

*1

.69

7 (

.12

9)*

**

1.4

89

(.1

05

)**

*

L

iter

alis

m1

.36

6 (

.09

9)*

**

1.5

99

(.1

24

)**

*1

.64

3 (

.18

5)*

*1

.11

5 (

.15

7)

RE

LT

RA

D

C

ath

oli

c.7

02

(.2

16

).4

94

(.2

88

)*.1

62

(.5

55

)**

*1

.63

6 (

.33

5)

B

lack

Pro

test

ant

1.0

88

(.3

60

)1

.70

6 (

.39

8)

1.4

33

(.4

96

).2

46

(.6

51

)*

M

ain

lin

e.9

15

(.2

02

).9

54

(.2

37

).4

30

(.3

70

)*1

.71

3 (

.32

6)

J

ewis

h.0

80

(.9

68

)**

--

-

.

14

4 (

1.3

75

)

.39

2 (

1.2

40

)

R

elig

iou

s o

ther

2.1

79

(.3

27

)*.9

86

(.4

20

).2

59

(.8

75

)

.2

61

(.8

66

)

N

o R

elig

ion

1.7

79

(.3

43

)1

.74

2 (

.41

2)

.99

5 (

.58

4)

.27

0 (

.83

2)

R2

(Nag

elk

erk

e).2

98

.30

1.2

96

.17

2N

=1

41

4*

** P

≤.0

01

*

* P

≤.0

1

* P

≤.0

5

So

urc

e: 2

00

5 B

aylo

r R

elig

ion

Su

rvey

Gender significantly affects only one of the experiences assessed (religious ecstasy).Males are more likely to claim a state of religious ecstasy than females. This is contrary toother facets of religiosity such as church attendance (Stark 2002) or frequency of prayer(Baker 2008), where females are likely to be more religiously active than men. Controllingfor levels of religiosity such as prayer and attendance, the differences between men andwomen regarding the various experiences analyzed are minimized. When models are runwithout these religious controls women are more likely to claim five of the nine experi-ences analyzed.

Race is significant in four of the models with whites being less likely to claim a reli-gious dream, a state of religious ecstasy, a miraculous healing, or a religious vision. Whenexamining religious traditions, Catholics are consistently less likely than Evangelicals toclaim the experiences analyzed. Having a religious dream, visions, and miraculous healingare the exceptions. For these three experiences there are no significant differences betweenEvangelicals and Catholics. Jews are also less likely than Evangelicals to claim a numberof the experiences, although this is not surprising considering that many of the experiencesare more “Christian” in content. There are some differences between religious “others” andEvangelicals, with religious others being more likely to claim a conversion experience, areligious dream, a state of religious ecstasy, and miraculous healing. However, consideringthat the religious other category includes groups as diverse and Buddhists, Mormons, andMuslims, these results are difficult to substantively interpret.

DISCUSSION

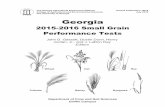

Support for the application of the concept of stakes in conformity is divided betweenincome and education. A high income level has a negative effect on the odds of claimingdeviant religious experiences and one of the less common normative experiences. Theincome variable demonstrates the cost of religious deviancy in vivid detail. Conceptualizedwithin Glock and Stark’s taxonomy (1965), the more intense the religious experience inquestion, the greater the influence of income. This is seen in figure one, showing the decreasein the odds of claiming a specific religious experience for a one unit increase in incomelevel. The only exception to the linear pattern is miraculous healing which, as previouslymentioned, has a practical reason for appealing to those at lower income levels.

Individuals at lower income levels have something to gain in claiming more intense reli-gious experiences in that they are privy to rewards unattainable through material means. Inessence, with little to lose in terms of class standing, they can achieve feelings, insights,and comfort that money literally cannot buy. Those in higher social classes have much moreinvested in conformity and in turn, a great deal to lose by claiming deviant religious expe-riences. In these instances the social standing accrued through income level could be lostif a person were to “lose face” within their social network. Losing face can be very costlysince, to quote Goffman, social face “can be [someone’s] most personal possession and thecenter of his security and pleasure, it is only on loan to him from society; it will be with-drawn unless he acts in a way that is worthy of it…” (1967:10). A surgeon claiming to havevisions might well lose the trust of her co-workers and patients, if not her job. A surgeonclaiming to have been called by God to her profession to help others will likely incur nosocial costs at all. The greater cost of claiming deviant experiences involved for people athigher income levels provides an explanation for the distinctive pattern shown in the pre-sented analyses.

50

Review of Religious Research

51

The Variety of Religious Experiences

In contrast, the findings for education level differ remarkably from those of income.Although the effects of education are minimal in this study, other studies have found a pos-itive, bivariate relationship between education level and claiming religious experiences(Beit-Hallahmi and Argyle 1997; Hay 1987; Hay and Morisy 1978). Here the opposite waspredicted based on stakes in conformity, but an increase in education level fails to reducethe likelihood of claiming deviant religious experiences. Further, the idea that educationdemystifies the supernatural does not apply to the religious experiences analyzed here.

As for age, younger people being more likely to claim normative religious experiencesmay be reflective of the influence of youth-oriented religious camps, retreats, and programs.Many of these programs provide social environments conducive to having religious expe-riences. In these environments, emotionally charged religious experiences can be quite com-mon and acceptable. Such atmospheres offer young people opportunities to have religiousexperiences in a welcoming environment. There could also be a broader cultural effect atwork whereby certain types of religious experiences are becoming more acceptable in main-stream culture over time. Levin (1993) found that mystical experiences are becoming morefrequent among younger cohorts. Similarly the National Survey of Youth and Religion foundthat 80% of teens reported having at least one type of religious experience (Smith and Den-ton 2005). Previous research has also indicated that younger people are more likely to par-ticipate in emotionally charged worship styles (Chaves 2004). The combination of theproliferation of youth-oriented religious programs, increased cultural acceptance of nor-mative religious experiences, and the tendency for young people to be more likely to selecthighly emotive worship styles provide potential explanations for the findings regarding age.

Figure 1

Percent Decrease in Odds of Claiming Religious Experience per

Unit Increase on Income Scale

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

Per

cen

t D

ecre

ase

in O

dd

s

Religious Dream

Miraculous H

ealing

Voice of G

od

Spoke in Tongues

Religious Visions

With any of the findings concerning religious measures as independent variables thereis an unresolved issue of causality, especially considering that 30.6% of respondents to theBaylor Religion Survey answered that they had “changed profoundly due to a religiousexperience.” It is certainly conceivable that having a religious experience could make a per-son more likely to attend church, pray, etc… For such variables there is clearly not unidi-rectional causality, but simply an influence. The relationship between religious experiencesand religious practice is likely reflexive in most cases. For the socio-demographic variablesthis is less of a concern due to time order. Other than the influence of income level on claim-ing more deviant experiences, there is not a definitive socio-demographic to the religiousexperiences analyzed here, which mirrors findings about secular paranormal experiences,which have been found to vary depending on the experience in question (Rice 2003).

CONCLUSION

Perhaps the most important aspect of the current study is the empirical support for amajority of Americans claiming some type of religious experience and evidence that thetypes of experiences claimed vary widely. In addition, the social forces influencing theseexperiences vary with the type of experience. The primary effort of this study has been tomove sociological studies of religious experience out of ambiguity and into quantitativeprecision. While this is certainly not the first study to do this, the breadth of experiencesanalyzed provides more detailed information on the topic than has previously been pre-sented. The differences found among specific experiences indicate that using a broad, all-encompassing question to analyze religious experiences is inadequate. A theoretical distinctionhas also been proposed between experiences involving only sensations of feeling and thoseinvolving other sensory sensations such as seeing, speaking, hearing, or healing. It is clearthat no matter how religious experiences are categorized, there are differences in the preva-lence and mainstream cultural acceptance of various types of experiences. Inquiring aboutthe tolerance of certain types of experiences, both in the broader American culture and with-in religious traditions, would undoubtedly advance our understanding of these distinctions.

We said in the introduction that any academic inquiry into religious experiences neces-sarily leaves questions unanswered—and this is the case here, as even the findings raisemore questions. Future studies could address what is causing the issues raised with age orthe disjoint between the influence of income and education. Yamane’s (2000) suggestionof incorporating narrative theory could also be utilized to provide more biographical con-text to experiences. Qualitative data would be valuable for assessing the personal effectsand consequences of having various types of religious experiences. Exploring the connec-tion between religious experiences and intense secular aesthetic, mystical, or paranormalexperiences could also be pursued. These are but a few of the directions that future inquirycould travel, and no matter how many studies are conducted there will always remain anelement of the unseen and the unknowable. That these experiences lay just beyond the“grasp” of research methods is what makes them intriguing and renders full disclosure ofsuch experiences impossible.

52

Review of Religious Research

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Direct all correspondence to: Joseph O. Baker; Department of Sociology; One Bear Place #97326; BaylorUniversity; Waco, TX 76798-7326. E-mail: [email protected]. Phone: (254)-710-7073. Thanks to ChrisBader, Carson Mencken, and Victor Hinojosa for their input and feedback on this project. The Baylor ReligionSurvey was funded by a grant from the John M. Templeton Foundation.

NOTES1Yamane (2000) provides an overview of previous methods used to assess religious experiences and an insight-

ful critique of solitary, closed-ended survey questions. Although he suggests applying a narrative approach tounderstanding religious experiences—a potentially fruitful but unexplored avenue—utilizing more specific sur-vey measures can help alleviate some of the issues raised by his criticism.

REFERENCES

Back, Kurt W., and Linda B Bourque. 1970. Can Feelings be Enumerated? Behavioral Science 15:487-96. Bader, Christopher D., Paul Froese, and F. Carson Mencken. 2007. American Piety 2005: Content and Methods

of the Baylor Religion Survey. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 46(4):447-63.Baker, Joseph O. 2008. An Investigation of the Sociological Patterns of Prayer Frequency and Content. Forth-

coming in Sociology of Religion. Batson, C. D., P. Schoenrade, and W. L. Ventis. 1993. Religion and the Individual: A Social-Psychological Per-

spective. New York: Oxford University Press.Beit-Hallahmi, Benjamin, and Michael Argyle. 1997. The Psychology of Religious Behavior, Belief, and Experi-

ence. London: Routledge.Boisen, Anton T. 1936. The Exploration of the Inner World. Norwood, Massachusetts: Plimpton.Chaves, Mark. 2004. Congregations in America. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.Dougherty, Kevin D., Byron R. Johnson, and Edward C. Polson. 2007. Recovering the Lost: Remeasuring U.S.

Religious Affiliation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 46(4):482-99. Durkheim, Émile. [1912] 1995. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, tr. Karen E. Fields. New York: Free Press.Goffman, Erving. 1967. Interaction Ritual: Essays on Face-to-Face Behavior. Garden City, New York: Anchor

Doubleday.Glock, Charles Y. and Rodney Stark. 1965. Religion and Society in Tension. Chicago, Illinois: Rand McNallyGreeley, Andrew M. 1974. Ecstasy: A Way of Knowing. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.Hardy, Alister. 1979. The Spiritual Nature of Man: A Study of Contemporary Religious Experiences. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.Hay, David. 1987. Exploring Inner Space: Is God Still Possible in the Twentieth Century? Oxford: A.R. Mowbray

& Co.__________, and Ann Morisy. 1978. Reports of Ecstatic, Paranormal, or Religious Experience in Great Britain

and the United States—A Comparison of Trends. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 17(3):255-68.Hirschi, Travis. 1969. Causes of Delinquency. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction.James, William. [1902] 1961. Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature. New York: Collier

Macmillan. Levin, Jeffery S. 1993. Age Differences in Mystical Experience. Gerontologist 33(4):507-13.Mencken, H. L. 1956. The Hills of Zion. Pp. 153-60 in The Vintage Mencken, ed. Alistair Cook. New York: Vin-

tage. Poloma, Margaret M. 1995. The Sociological Context of Religious Experience. Pp. 161-82 in Handbook of Reli-

gious Experience, ed. Ralph W. Hood, Jr. Birmingham, Alabama: Religious Education Press. __________, and Brian Pendleton. 1989. Religious Experiences, Evangelism, and Institutional Growth within the

Assemblies of God. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 28(4):415-31. Proudfoot, Wayne. 1985. Religious Experience. Berkeley: University of California Press.Rice, Tom W. 2003. Believe It or Not: Religious and Other Paranormal Beliefs in the United States. Journal for

the Scientific Study of Religion 42(1): 95-106. Smith, Christian. 2003. Moral Believing Animals: Human Personhood and Culture. New York: Oxford Universi-

ty Press.

53

The Variety of Religious Experiences

54

Review of Religious Research

__________, with Melinda Lundquist Denton. 2005. Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of Amer-ican Teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press.

Spilka, Bernhard, George A. Brown, and Stephen A. Cassidy. 1992. The Structure of Religious Mystical Experi-ence in Relation to Pre- and Postexperience Lifestyles. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion2(4):241-57.

Stark, Rodney. 1965. Social Contexts of Religious Experience. Review of Religious Research 7(1):17-28. __________. 2002. Physiology and Faith: Addressing the “Universal” Gender Difference in Religious Commit-

ment.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41(3):495-507.__________, and William S. Bainbridge. 1987. A Theory of Religion. New York: Peter Lang.__________, and Roger Finke. 2000. Acts of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion. Berkeley: Universi-

ty of California Press.Starbuck, Edwin Diller. 1899. The Psychology of Religion: An Empirical Study of the Growth of Religious Con-

sciousness. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons.Steensland, Brian, Jerry Z. Park, Mark D. Regnerus, Lynn D. Robinson, W. Bradford Wilcox, and Robert Wood-

berry. 2000. The Measure of American Religion: Toward Improving the State of the Art. Social Forces 79(1):291-324.

Tamminen, Kalevi and Kari E. Nurmi. 1995. Developmental Theories and Religious Experience. Pp. 269-311 inHandbook of Religious Experience, ed. Ralph W. Hood, Jr. Birmingham, Alabama: Religious Education Press.

Thomas, L. Eugene, and Pamela E. Cooper. 1978. Measurement and Incidence of Mystical Experiences: AnExploratory Study. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 17(4):433-37.

Toby, Jackson. 1957. Social Disorganization and Stake in Conformity: Complementary Factors in the PredatoryBehavior of Hoodlums. Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology and Police Science 48(May-June):12-17.

Vold, George B., Thomas J. Bernard, and Jeffery B. Snipes. 1998. Theoretical Criminology, 4th Ed. New York:Oxford University Press.

Wuthnow, Robert. 1978. Peak Experiences: Some Empirical Tests. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 18(3):59-75.

Yamane, David. 1998. Experience. Pp. 179-82 in Encyclopedia of Religion and Society, ed. William H. SwatosJr. Walnut Creek, California: AltaMira.

__________. 2000. Narrative and Religious Experience. Sociology of Religion 61(2):171-89.__________, and Megan Polzer. 1994. Ways of Seeing Ecstasy in Modern Society: Experiential-Expressive and

Cultural-Linguistic Views. Sociology of Religion 55(1):1-25.