The Translation of Kutiyattam into National and World Heritage on the Festival Stage: Some Identity...

Transcript of The Translation of Kutiyattam into National and World Heritage on the Festival Stage: Some Identity...

2013

Harrassowitz Verlag . Wiesbaden

South Asian Festivals on the Move

Edited by Ute Hüsken and Axel Michaels

Sonderdruck aus

Table of Contents

Introduction 9

1. Festivals as Sites of Public Negotiation

Eva Ambos & William S. Sax Discipline and Ecstasy: The Kandy and Kataragama Festivals in Sri Lanka................................... 27

Kerstin Schier Paṅkuṉi Uttiram and the Transmission of Cultural Memory..................... 59

Alexander Henn Moving the World—Moving the Self: The Gaude Jagor in Goa............... 83

Ute Hüsken Flag and Drum: Managing Conflicts in a South Indian Temple................ 99

Rich Freeman Arresting Possession: Spirit Mediums in the Multimedia of Malabar ....... 135

2. The Global and the Local

Christiane Brosius Negotiating Belonging in a Megacity: The Spatial Politics of a Public Art Festival .............................................. 169

Leah Lowthorp The Translation of Kutiyattam into National and World Heritage on the Festival Stage: Some Identity Implications ..................................... 193

Lokesh Ohri Political Appropriation and Cultural Othering in a Heritage Festival ....... 227

Heike Moser Kūṭiyāṭṭam on the Move: From Temple Theatres to Festival Stages .................................................. 245

Karin Polit Moving Deities and the Public Sphere ....................................................... 275

3. People on the Move: Festivals and Processions as Public Events

Silke Bechler Kumbha Mela: Millions of pilgrims on the move for immortality and identity ................. 297

Axel Michaels From Syncretism to Transculturality: The Dīpaṅkara Procession in the Kathmandu Valley ................................ 317

Jörg Gengnagel (in collaboration with Rajendra Singh Khangarot) Inside and Outside the Palace: The Worship of the Royal Insignia (śastravāhanādipūjā) in Jaipur .......... 343

4. The Old, the New and the Old Renewed

Annette Wilke Tamil Temple Festival Culture in Germany: A New Hindu Pilgrimage Place ................................................................. 369

Paul Younger Pilgrims in a Trans-national Setting: Pilgrimage in the Canadian Temple Traditions of Ayyappan and Athi Parasakthi ............................................. 397

Contributors 417 Index 421

LEAH LOWTHORP

The Translation of Kutiyattam into National and World Heritage on the Festival Stage:

Some Identity Implications1

The Translation of Kutiyattam

Traditionally performed as part of Kerala’s temple festival complex, Kutiyattam theater has been integrated into both national and international structures of recog-nition and patronage in a postcolonial Indian context. This integration has served to re-contextualize the art form in festivals of a new nature, namely those showcasing national and international “heritage.” This article critically examines the art form’s increasing recognition, patronage, representation and festival showcasing by the Sangeet Natak Akademi, India’s national academy for dance, drama, and music, as a process of deliberate integration into the narrative of the Indian nation-state. Moving on to consider how this process of national heritage transformation reached a pinnacle with Kutiyattam’s recognition by UNESCO as India’s first Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2001, it questions the implications of Kutiyattam as simultaneously a cultural representative of a national India on a global scale, and a cosmopolitan “heritage of humanity.” In both processes I ultimately explore how such translation into national and interna-tional heritage, with their implied “national” and “global” identities, is positioned among contemporary, professional Kutiyattam artists’ conceptions of belonging, and more widely in a plurality of Kutiyattam identities within Kerala’s postcolonial modernity.

Kutiyattam and Indian Heritage

Kutiyattam, reputed to be the oldest theater form in contemporary India, dates its earliest verifiable record to the 10th century C.E.2 Originally a secular tradition performed in royal courts, it was only later incorporated into Kerala’s conservative, caste-based temple complex in the 13th or 14th century.3 Kutiyattam embodies a mixture of elements both from Sanskritic tradition and the indigenous

————— 1 For the purposes of readability, I have chosen not to use diacritical marks in my translitera-

tions of Malayalam and Sanskrit words. 2 The record cites King Kulasekhara, who ruled a central Kerala kingdom in the 10th century

C.E., as having reformed Kutiyattam and authoring the plays Subhadra Dhananjayam and Tapatisamvaranam, see Raja 1974. Kutiyattam is also often described as the oldest continu-ously performed theater form in the world.

3 See Narayanan 2006: 142.

Leah Lowthorp

194

Fig. 1: Kalamandalam Sivan Nambudiri as Ravana (Photo: Leah Lowthorp).

cultural landscape of Kerala, and is traditionally performed annually by both men and women from the Chakyar, Nambiar and Nangiar castes in temple theaters called kuthambalams, often within the context of a temple festival.4 The term Kutiyattam encompasses a larger performance complex which includes Kutiya-ttam, the enactment of Sanskrit drama with multiple actors onstage; Nangiar ————— 4 For information regarding Kutiyattam’s performance in specific festival contexts, see

Chakyar, M. M. 1975; Chakyar, A. M. 1995; Johan 2011; n.d.; Menon 2000; Moser 2008; 2011; Rajagopalan 2000; Unni 2001. I would like to thank Dr. C. K. Jayanthy and V. Johan for correspondence with me pertaining to this subject.

The Translation of Kutiyattam

195

Koothu, the female acting solo; and Chakyar Koothu, the male verbal solo performance.5 Recognizable by its rich narrative expression through mudra hand gestures, highly emotive facial expressions, stylized movements, and sparse dia-logue of chanted Sanskrit, Kutiyattam’s focus on the aesthetic elaboration and extension of each moment means that one play is never performed in its entirety. Rather, as an “art of elaboration (that) extends the performance score to unbeliev-able heights of imaginative fancy,” one act has a general duration of five to ten days, and can last up to forty-one (Gopalakrishnan 2000).

Socio-historically, contemporary Kutiyattam was embedded in intense social, economic, and political upheavals which transformed twentieth century Kerala from a rigid, closed society with the strictest caste system in India, into a socially and geographically mobile, highly educated and politically active population (Jeffrey 1992). Twentieth century changes directly affecting the art include the crumbling of royal patronage, social movements agitating for the opening of temples to all castes, the establishment of Kerala state, the Communist land redistribution act depriving artists of their lands, and state legislation officially destroying matrilineal inheritance, the traditional base of the Kutiyattam family system.The blurred dichotomies of private/public, tradition/modernity, religious/ secular, and orthodox/progressive which largely characterize contemporary Kerala society as a result, are thereby also reflected in Kutiyattam.6 Despite being so rooted in contemporary processes of change, Kutiyattam has generally been represented as a “marginal survival” of an ancient, Sanskritic, pan-Indian past since the moment it first came to wider public attention with the “discovery” of the so-called Trivandum Bhasa plays in 1909.7 The palm leaf dramatic manuscripts that were brought to light by Ganapati Sastri in Kerala and attributed to the famed Sanskrit playwright Bhasa, whose plays had long been given up for lost, were found to be “preserved” in performance in Kerala’s Kutiyattam tradition (Sastri 1915).8 Thus since the first moment of wider attention outside of its immediate local and performance communities, Kutiyattam has largely been marked by

————— 5 For an extensive analysis of the history and performance of Nangiar Koothu, see Moser

2008; 2011; see also Daugherty 1994; Paniker 1992. For that of Kutiyattam, see Johan n.d.; Jones 1967; Richmond 1990; Sowle 1982; Sullivan 1997; Vatsyayan 1980. For a description of recent innovative trends in contemporary Nangiar Koothu, see Daugherty 2011.

6 For more information on how these dichotomies play out in Kutiyattam, see Lowthorp 2010a. 7 The concept of marginal survival is part of the Finnish or comparative method in the field of

Folkloristics, and encompasses the idea that traditions survive on the periphery, away from the center in which they may have originated but no longer exist. Kerala has a wider reputation for its preservation of Sanskritic culture as a “repository of ancient Sanskrit texts” (Raja 2001: xii) and Sanskritic expressive traditions such as Kutiyattam and Vedic chanting.

8 See also Brückner 1999/2000; Raja 2001; Unni 2001.

Leah Lowthorp

196

Fig. 2: Kalamandalam Reshmi as Sita (Photo: Leah Lowthorp).

pastness as the “only surviving link with the ancient Sanskrit theatre” (Sangeet Natak Akademi 1995).9 This characterization of the art form as a remnant of the past, a common trope in heritage discourse, has been tied to similar discourses of endangerment and “samrakshanam” (safeguarding) that I argue elsewhere have developed in ever-widening contexts through the present-day. 10 While artists

————— 9 This marking of pastness is embodied in arguments for analyzing Kutiyattam as a window

onto the past of ancient Sanskrit dramatic performance, such as in Byrski 1967. 10 See Lowthorp 2010b; 2010c; 2011a; 2011b; n.d.

The Translation of Kutiyattam

197

themselves often subscribe to the exaggerated age of Kutiyattam as two thousand years old, thus tying it to an age of the pan-Indian performance of Sanskrit drama”, they nevertheless struggle against common depictions of themselves in the media as remnants of an ancient past by virtue of being performers of an “ancient” art. I was witness to several attempts by artists to contemporize themselves through asserting their subjectivity as contemporary artists practicing a contemporary art form. I observed one young artist’s such assertion before an audience of university students from across India as she stated, “I am just like you. I also like to go to the cinema and spend time with my friends.”11 One newspaper article written about this same young artist called her a time traveler straddling two worlds, that of “the global village of mobile phones, e-mails, televisions and automobiles … (and) the other … peopled by mythical, larger-than-life characters who come alive on stages lit by the flickering golden light of traditional lamps” (Nagarajan 2009).

Heritage is conceptualized as a politically situated cultural practice which frequently promotes a state-sanctioned consensus view of history, in the process masking its own involvement in the production of power, identity and authority (Bendix 2000; Smith 2006). It has been imagined by Anderson (1983) as a process of political inheriting, by Appadurai (1996) as one of political museumizing, and by Vakil (2003) as a site of translation into the dominant culture. Implicated in a politics of inclusion and exclusion whereby symbols become part of a “totalizing classificatory grid” of the nation, peoples, regions, religions, traditions, languages, and monuments are thereby included or excluded from the national imaginary (Anderson 1983). It is this notion of heritage as a process of translation and selective inclusion in the construction of a national, cultural imaginary that I apply to my analysis of Kutiyattam’s heritage transformation.

Framed within examinations of the ways nations and communities are imagined and invented which reveal the fluidity of both the nation itself and of cultural identification, Cherian (2009: 34) has argued that the Indian nation was performed into being from a governmentally, economically, linguistically and socially divided territory through an affirmation of India’s cultural unity, namely: “the (Indian) State’s performances of modernity are based on an understanding of culture as both the locus of the traditional and as the imagined foundation of a social solidarity that makes the modern State possible.” Hancock (1998) has noted the effects and methods of governmentality embedded in the Indian state’s assertions that certain cultural expressions and languages were “national,” and interrogates the role of one influential figure, Dr. V. Raghavan, in propounding a hegemonic, Sanskrit-based national culture both nationally and internationally. India’s imagined cultural solidarity conforms to the standard legend of national formation which, according to Abrahams (1993), constitutes a process of historical purification whereby “an

————— 11 On the occasion of the 24th National Convention of Spic Macay in Trivandrum, May 2009,

that was dedicated to the memory of Guru Ammannur Madhava Chakyar.

Leah Lowthorp

198

old culture (is) resuscitated, (and) the intervening forms … swept away, along with the alien powers that conquered the land and put their culture into the place of the old traditions.” In this case, the legend of Indian national formation widely assumes an “ancient” pan-Indian Hindu-Aryan identity, itself a product of Orientalist knowledge construction in which the period of Mughal Muslim rule was characterized as that by foreign invaders.12

In the immediate postcolonial context, the Sangeet Natak Akademi (hereafter referred to as the Akademi), was established as the facilitator of the new nation’s cultural unity, a critical instrument linking the Center and the regions through practices of affiliation and recognition which brought art forms and institutions into a unified national framework, thereby critically subordinating the regional in a period of contentious claims to regional nationhood (Cherian 2005; Dalmia 2006). With the Akademi’s creation, the Indian government explicitly acknowledged its responsibility of “filling the vacuum” left by crumbled systems of royal arts pa-tronage, with the aim “to preserve (Indian) traditions by offering them an institutional form … not only for our own sake but also as our contribution to the cultural heritage of mankind” (SNA Annual Report 1953–58: 1). Contemporary Indian performing arts thus quickly became formulated as “heritage” by the Akademi as they became incorporated into a national centralized framework. In the case of Kutiyattam, it is important to note that Kerala had a seat at the national performing arts table since the very beginning of the Akademi in 1953, even preceding Kerala state’s 1956 formation. This early stake at the national level can be seen with Kathakali’s inclusion as one of only four dance forms originally recognized as classical, showcased in the first National Dance Festival of 1955. In a system where classical recognition by the Akademi increasingly became a political game of regional recognition (Cherian 2009), Kerala, as the only state with three recognized classical forms (Kutiyattam, Kathakali, and Mohiniyattam), continues to maintain its prominence on the national stage.

Kutiyattam and the Sangeet Natak Akademi

Kutiyattam came to be included in the Indian national narrative through its increasing recognition and patronage by the Akademi and its gradual incorporation into a national level festival framework. I argue that this represents a specific process of heritage creation as an “instrument of modernization and mark of modernity” for the Indian nation-state, one that often extended “museological values and methods (collection, documentation, preservation, presentation, evalua-tion, and interpretation) to living persons, their knowledge, practices, artifacts,

————— 12 See Bhatti 2005; Chakravarti 1989; Ludden 2005. For how 19th century nationalists appropri-

ated Orientalist discourses in a nationalization of Hindu traditions, see Dalmia 1997.

The Translation of Kutiyattam

199

social worlds, and life spaces” (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 2004; 2006).13 Kutiyattam’s translation into national heritage was accomplished through several strategies such as the early showcasing of the art in north India, national documentation and archiving projects, recognition through the Akademi awards system, and incorporation into national funding schemes.

The art form’s first exposure to the national occurred with its first formal public performance outside of the temple context, organized by All-India Radio in 1956 before an invited audience at the Zamorin’s royal palace in Calicut.14 As a programming consultant for All-India Radio, Sanskrit scholar Dr. V. Raghavan of Madras University, mentioned earlier for his role in promoting a Sanskritized national culture, was present at the performance, and went on to draw national attention to the art form with the presentation of his paper “Sanskrit Drama and Performance” at the first national Drama Seminar organized in Delhi the same year.15 In 1962 Dr. Raghavan, by this time a prominent member of the General Council of the national Akademi, played an instrumental role in bringing Kutiyattam outside of Kerala for the first time by inviting artist Mani Madhava Chakyar and troupe to perform at the Samskrita Ranga in Madras.16 He also introduced Sanskrit scholar Dr. Byrski of Poland to the art form, who went on to become the first non-traditional member as well as first foreigner to train in Kutiyattam. In 1964, Dr. Byrski played an instrumental role in bringing Kutiyattam artists to North India for the first time, where they performed in Delhi at the Paderewski Foundation, the National School of Drama, and in Benares at the BHU Arts College and the Maharaja’s Ramnagar Palace. They were further called back to Delhi the same year to perform upon the personal invitation of then-President of India, philosopher Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan.17 This first foray into the north was significantly undertaken by Mani Madhava Chakyar, the most accomplished Sanskrit scholar among Kutiyattam performers of the twentieth century, and accompanied by his Hindi-speaking son P.K.G. Nambiar who innovatively performed the role of the comical vidusaka in Hindi, thus bridging the linguistic

————— 13 While not within the scope of this article, I examine how these processes affected Kutiyattam

performance in my dissertation, see Lowthorp n.d. 14 This constituted Kutiyattam’s first public performance in its form of multiple actor drama. I

was told by the Mani family that Mani Madhava Chakyar was first requested for this 1956 performance, it being within his traditional geographical performance domain. Upon falling ill with chicken pox however, asked Painkulam Rama Chakyar to perform in his stead. Kuti-yattam’s initial temple exit occurred in 1949, when an adapted form of the male solo Chakyar Koothu was first performed outside of the temple by Painkulam Rama Chakyar.

15 See Raghavan 1993. Dalmia (2006) attributes this seminal paper with sparking a national level focus upon Sanskrit drama.

16 See Byrski 2008/09; Sreekanth 2008/09; Sangeet Natak Akademi Annual Report 1962–63. 17 See Byrski 2008/09; Sangeet Natak Akademi Annual Report 1963–64.

Leah Lowthorp

200

divide by making the form as intelligible to audiences in the north as to those in Kerala.18

Fig. 3: Mani Madhava Chakyar and daughter Amminikutty Nangiaramma on their first tour to North India, 1964 (Photo collection: Padmashree Mani Madhava Chakyar Smaraka Gurukulam).

Upon this initial trip to North India, the first documentation and archiving of Kutiyattam at the national level took place in Delhi, with Mani Madhava Chakyar filmed by the Akademi under the scheme “Filming the Repertoire of Outstanding Exponents of Traditional Dance Forms” (SNA Annual Report 1963–64). This agrees with the general trend noted by Polit (this volume) of Indian national cultural institutions bringing traditional forms to the capital to document and

————— 18 P. K. G. Nambiar has to my knowledge remained the only artist to this day who has success-

fully bridged the North/South Indian linguistic divide through the figure of the vidusaka.

The Translation of Kutiyattam

201

archive them, preferring to transport them to the Center rather than going out to the peripheral locations of the forms themselves. With this first transportation to the capital, Kutiyattam was thereby officially incorporated into the national narrative through its documentation and inclusion in the national archives of performing arts at the Akademi in Delhi. Antonnen (2005) compares the establishment of national archives to the institutionalization of museums as repositories and manifestations of national identity and cultural achievement, formulating them as housing “material” manifestations of the Herderian “spirit of a nation,” thus making them contested spaces in the same process of inclusion and exclusion in the national narrative. Firmly rooting Kutiyattam in the contested space of national heritage, this first documentation and archiving of Kutiyattam in 1964 began a trend of extensive documentation and archiving activities undertaken by the Akademi which have continued up to the present-day.

Through the Akademi Awards system of individual artistic recognition, Kutiya-ttam became incorporated into a national framework of both award recognition and festival showcasing. In 1964 Mani Madhava Chakyar became the first Kutiyattam artist to receive a national award in the form of a Sangeet Natak Akademi Award, and thereby performed in a showcase of national award winners which would later come to be known as the Akademi Festival of Arts (SNA Annual Report 1964-65). This event marks the transition from an initial independent performance exhibition of Kutiyattam at the national level, to its inclusion in a newly emerging trend of festival showcasing as one among several “Indian” performing arts, together embodying the popular slogan “unity in diversity.”19 Cherian (2005: 120) notes that the national Awards allowed the Akademi to center the discourse of tradition firmly within the framework of the state, thereby naturalizing the nation-state and “conferring it an indigenous and ancient vintage.” Such state recognition of performing artists was described metaphorically by the former President of India, Sri Venkataraman, who compared the process of artistic recognition to life-giving sustenance itself in his statement that “the recognition of talent is to art as what sunshine is to flowers,” which thereby discursively naturalized the nation-state as life-giver to the arts (SNA Annual Report 1988–89).

Kutiyattam was thus quickly thrown into the national spotlight from the time of its temple exit through intense national interest in the art form beginning in the early 1960’s. It is notable that this national claiming of Kutiyattam through struc-tures of recognition, archiving and showcasing occurred before its claiming by Kerala state when the art first became incorporated into the state performing arts institution, Kerala Kalamandalam, in 1965. The interest of the national government in the art form during this period can be contextualized in the governmental Third Plan (1960/61–1965/66) that Cherian (2009: 37) has characterized as a period

————— 19 For more information on the use of this slogan in India, see Wessler 2006.

Leah Lowthorp

202

solidifying the governmental project relating to culture, as one “of its retrieval and protection, and its staging as a sign of the past.” She further observes:

The Third Plan’s highlighting of the antiquity of India’s culture signals an important transition in terms of how the State engages the arts. From the 1960s onwards we see an institutional imperative supporting the production of cultural forms approxi-mating notions of the traditional. In short, the State takes upon itself the exercise of redeeming national culture (ibid).

Dalmia (2006: 170) details how the Akademi conceptualized performing arts a-cross India from its beginning as “rural derivations of and deviations from the all-encompassing Sanskritic tradition from which they had emanated and into which they could, under the new dispensation, flow again.” This early emphasis placed by the Akademi upon Sanskritic tradition came to particularly influence the develop-ment of a contemporary, “indigenous” Indian theater, as Sanskrit drama” in parti-cular became “a matter of state concern, not only as the fountainhead of all past forms but also as providing orientation for all future development” (ibid).20 With this contextualized focus on Sanskrit, antiquity, and notions of the traditional during this period, it therefore comes as no surprise that the Akademi was so interested in highlighting Kutiyattam, which as “traditional Sanskrit theater” personified all three.

The Akademi’s view of Kutiyattam as embodying antiquity, tradition, and San-skritic culture” is reflected in the terminology with which the art form has been represented in the Akademi’s annual reports through the present-day. In the early period, from the 1960’s through the early 1980’s, typical descriptors of the art form in the reports include: “the only surviving traditional form of classical Sanskrit Drama,” “the oldest form of Sanskrit drama tradition,” and “the only Sanskrit theatre tradition now surviving in Kerala.” It was also incorrectly oversimplified as a “form of theatre which is being staged as per the tenets of the Natya Sastra (which) survives in Kerala.”21 In a large twenty year interval from the early 1980’s through the early 2000’s however, Kutiyattam ceased being marked in the reports as ancient and/or Sanskritic, either not accompanied by any descriptive adjectives at all, or referred to simply as “the classical theatre of Kerala.”22 Interestingly enough, explicit emphasis upon the ancient and Sanskritic nature of Kutiyattam in

————— 20 Kutiyattam has been privileged as a reference within this contemporary theater movement,

with Mani Madhava Chakyar chosen to inaugurate the 1977 National Drama Festival (Sangeet Natak Akademi Annual Report 1977-78), numerous contemporary theater practi-tioners studying Kutiyattam techniques with masters in Kerala over the years, and most recently the month-long Kutiyattam workshops conducted in Delhi with the National School of Drama students by the artists of the Ammannur gurukulam, in 2009 and 2010.

21 For studies detailing how Kutiyattam differs from the Natya Sastra, see Gopalakrishnan 1988; Paulose 1993; Unni 2001.

22 Notwithstanding the erasure of the explicit terms “ancient” and “Sanskrit,” the employment of the term “classical” still encapsulates both of these notions.

The Translation of Kutiyattam

203

the Akademi’s vocabulary seems to have been renewed post-UNESCO recognition, re-emerging in the 2003–04 annual report and persisting through the present-day. Here Kutiyattam again becomes explicitly marked as Sanskritic, “the classical Sanskrit theatre of Kerala,” and as both ancient and Sanskritic with the widely employed descriptor “the age-old Sanskrit theatre of Kerala.” Most recently, Kutiyattam’s regional affiliation has been dropped altogether as it becomes simply “the ancient Sanskrit theatre.” It could be speculated that Kutiyattam’s recognition by UNESCO, characterized by a Western heritage discourse in which greater age is equated with greater authenticity, perhaps sparked renewed enthusiasm for this particular representation of Kutiyattam.23

I now turn to a further exploration of Kutiyattam’s re-contextualization from its performance as part of Kerala’s temple festival complex to its inclusion in India’s newly emerging national festival culture, in which various regional forms were exhibited in a process of heritage creation as representations of Indian national tradition. Cantwell (1993) distinguishes such festivals from museums and archives through their engagement of the body in “some immediate exhibitory way,” identi-fying a participant’s living presence with their artistic performance in a process which brings both into the possession of the Festival, and I argue that of the sponsoring institution and nation-state as well.24 The national festival trend in India began with the first national music, dance, and drama festivals in 1954, 55, and 54 respectively (SNA Annual Report 1953–58). The Akademi Awards and accompanying Akademi of Arts Festival was initiated annually beginning in 1954, but the Akademi otherwise began instituting annual performance festivals on a national scale only in the early 1980’s, with festivals initiated to support the work of young performing artists nationwide.25 Kutiyattam’s incorporation into these annual national performance festivals was first facilitated through the newly rein-vented female solo-form Nangiar Koothu in 1986, performed by Kalamandalam Girija at the Yuva Utsav festival in Madras.26 Nangiar Koothu’s easily condensa-ble female solo performance, which fit more easily into a larger dance framework than the multiple-character Kutiyattam drama, has remained by far the most commonly performed form within the Kutiyattam complex to participate in these ————— 23 For a detailed study on Western heritage discourse see Smith 2006. 24 Cantwell (1993) writes in the context of the Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife, see

in particular the chapter “The Empire of Ice Cream: A Poetics of Recognition.” 25 Lok Utsav, an annual festival of traditional music, dance, and theatre, and Natya Samaroh, a

festival giving an annual platform to young directors to showcase experimental theater, were both founded in 1984, while Yuva Utsav and Nritya Pratibha were both initiated the year thereafter as part of a concerted effort to “support and promote young talent in classical music and dance,” see Sangeet Natak Akademi Annual Report 1987-88.

26 Sangeet Natak Akademi Annual Report 1986-87. For a discussion of the reinvention of Kuti-yattam at Kerala Kalamandalam, see Lowthorp 2011b, and for literature examining the invention and reinvention of tradition on a wider scale, see Hobsbawm and Ranger 1983; Prickett 2009.

Leah Lowthorp

204

Akademi-sponsored national showcase festivals. The male nirvahanam solo element of Kutiyattam has also been featured in such festivals, but on a much lesser scale.27 The fact that Kutiyattam has predominantly been showcased in dance festivals is indicative of a larger genric ambiguity surrounding Kutiyattam’s classi-fication at the national level. Despite the fluidity of genric classification of performing arts in India, Kutiyattam is categorized by its artists predominantly as drama or theater. Within the frame of the Akademi Awards, the Akademi has classified Kutiyattam alternatively as traditional dance, dance, or the newer all-inclusive traditional/folk/tribal dance/music/theater/puppetry fairly indiscriminate-ly, however there does exist a broad progression of classification over time from traditional dance, to dance, to traditional/folk/tribal dance/music/ theater/puppetry in later years.28

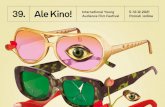

The 1995 Kutiyattam Mahotsavam, a six-day festival devoted exclusively to performances, lecture-demonstrations, and discussions of Kutiyattam in Delhi, was “the first time that a major event focussed (sic) on this important tradition of Indian theatre (was) held in the Capital” (Sangeet Natak Akademi 1995). Whereas Kutiyattam had previously numbered one among other “Indian” performing arts in national festival contexts, this event significantly placed Kutiyattam in a league of its own in recognition of what the Akademi termed the art’s “unique and … exalted place … among the traditional forms of Indian theatre … (as) our only surviving link with the ancient Sanskrit theatre”” (ibid). Documentation and archiving of the form were explicitly acknowledged as an important dimension of the festival, with certain dramatic performances “planned exclusively for archival recording during the festival days” (ibid). Indeed, a complete videographic record of the entire festi-val including performances, demonstrations, discussions and interviews can be found in the national Akademi archives in Delhi. With approximately forty Kuti-yattam artists participating from all major training and performance institutions at the time (Margi, Kerala Kalamandalam, Ammannur Chachu Chakyar Smaraka Gurukulam, and Mani Madhav Chakyar Smaraka Gurukulam), this festival represented the first instance of inter-institutional collaboration on such a grand scale, with artists assembling in far-off Delhi in the name of Kutiyattam, as they had never before assembled in Kerala itself. While the Kutiyattam Mahotsavam festival considerably reflected the art’s privileged position and greater integration into the performing arts canon of the Indian nation-state, I argue that it simul-taneously served to promote a larger, regionally based artistic identity among professional artists as part of a larger scheme benefitting the art as a whole, a point to which I will later return.

————— 27 Margi Madhu performed this at the 1990 Sangeet Nritah Samaroh festival in Delhi, see

Sangeet Natak Akademi Annual Report 1990-91. 28 Despite a general progression towards the latter category, Sivan Nambudiri’s 2007 Akademi

Award was classified as dance.

The Translation of Kutiyattam

205

Fig. 4: Cover of the special issue of the Sangeet Natak Akademi’s journal commemorating the 1995 Kutiyattam Mahotsavam, Sangeet Natak Akademi Archives.

Kutiyattam as National-cum-Global Heritage

Moving on to consider Kutiyattam’s integration into international structures of re-cognition and patronage, I mainly focus upon Kutiyattam’s 2001 recognition by UNESCO, and the implications this has had for the art in an Indian national context. To give a brief history of Kutiyattam’s wider involvement on an inter-national level, though the art’s first international exposure came with Dr. Byrski’s interest in the early 1960’s, its first foreign tour occurred in 1980 when the Kalamandalam Kutiyattam troupe performed in Paris under the aegis of Mandapa and Milena Salvini, and in Warsaw upon the invitation of Dr. Byrski. Since this initial tour, Kutiyattam has been extensively showcased in festivals and demonstra-tions across Europe, Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and the United States, and several artists have led workshops for contemporary theater practitioners or participated themselves in theater exchanges and experimental theater inter-nationally.29 It was on one such international tour to Paris in 1999, at a time when

————— 29 See Anonymous 2000; 2010; Moser 2008; 2011; Venu 2002.

Leah Lowthorp

206

Kutiyattam was already deeply embedded in global flows of performing artists worldwide, that Kutiyattam was invited to apply for a new program UNESCO was initiating, namely that of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.30

Fig. 5: Ammannur Madhava Chakyar on the cover of UNESCO’s First Proclamation of Master-pieces, 2001, UNESCO.

The Masterpieces program, part of a larger UNESCO intangible cultural heritage (ICH) initiative, was the first to formally recognize expressive culture on such an international scale. Emerging largely in response to “non-Western” critique of a hegemonic, Western materialist heritage discourse which was dominating interna-tional organizations like ICOMOS and UNESCO, the creation of an intangible counterpart to UNESCO’s World Heritage program was an attempt to correct the

————— 30 Interview with Gopalakrishan March 15, 2010; see also Gopalakrishnan 2011.

The Translation of Kutiyattam

207

world heritage global imbalance that was heavily weighed against developing nations. 31 The program has garnered extensive scholarly criticism, raising concerns about the extension of museological values and methods to living persons and their cultural worlds in attempts to “curate” culture, as well as critique of the implementation of preservationist management practices which potentially stifle cultural expression and promote cultural fossilization.32 As mentioned briefly above, despite a new approach focusing on the intangible aspect of heritage, this program was dominated by a Western heritage discourse characteristic of early salvage anthropology and folklore which stressed endangerment and an urgent need for safeguarding in a fast-changing “modern” world. The Masterpiece program in particular required that an art form must “risk disappearing due either to the lack of means for safeguarding and protection (sic) it or to processes of rapid change, urbanization or acculturation” (UNESCO 2001: 5).

Beginning in the 1970’s, the Akademi had already begun to employ a similar discourse at the national level by establishing a scheme to support endangered art forms entitled “Promotion and Preservation of Rare Forms of Traditional Perform-ing Arts,” which sought to ensure the continuation of art forms “threatened with extinction” by providing financial assistance to gurus to train pupils (SNA Annual Report 1974–75). While this and previous schemes had benefitted individual gurus and their students, the scheme “National Centres for Specialised Training in Music and Dance,” to which the previously mentioned Kutiyattam Mahotsavam belonged, was established in 1991 to benefit the art form as a whole. This scheme, which sought the preservation of performing-arts “threatened by a changing socio-econo-mic environment,” featured a “total care plan for the preservation of Koodiyattam,” the only art form to be included in its first year (SNA Annual Report 1991–92). As Kutiyattam was prominently featured early on among these “endangered” art forms that were conceived of and portrayed as somehow less able than others to adapt to the changing times, when UNESCO came onto the scene with rhetoric pitting “traditional” culture as threatened in the face of a destructive modernity, this constituted but a further manifestation of discourses of endangerment and safe-guarding that were already quite familiar to Kutiyattam.33

With its recognition by UNESCO in 2001, Kutiyattam became the cultural face of a national India on an international scale. As the only form sent by India for consideration to UNESCO, I argue that this constituted the pinnacle of India’s recognition of Kutiyattam as national heritage, with the art deemed capable of singularly representing the nation in this supranational forum. The Akademi’s earlier acknowledgement of Kutiyattam’s “unique and exalted place” within traditional Indian theater was further reinforced after UNESCO recognition and

————— 31 See Blake 2001; Hafstein 2007; Smith 2006. 32 Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 2004; See also Claessen 2002; Kurin 2002; Nas 2002. 33 For further discussion see Lowthorp 2010b; 2010c; n.d.

Leah Lowthorp

208

Fig. 6: Margi Madhu, Kalamandalam Ratheesh Bhas and Nepathya Saneesh in a Sangeet Natak Akademi Kutiyattam Kendra sponsored program, 2009 (Photo: Leah Lowthorp).

stated as such: “Kutiyattam, the Sanskrit theatre” tradition of Kerala, now recognized as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, has always found a special place in the schemes and programmes of the Sangeet Natak Akademi” (SNA Annual Report 2005–06). This simultaneous translation of expres-sive forms into international and privileged national heritage finds its embodiment in the festival that was held at UNESCO Headquarters in Paris showcasing six of the nineteen 2001 Masterpieces, as part of UNESCO’s 31st General Conference. Several Kutiyattam artists who participated in the festival narrated what they perceived to be Kutiyattam’s special status among the other art forms. Already among the few invited to perform in Paris, this observation was bolstered by artists’ descriptions of Kutiyattam as the first art form onstage as well as that allotted the greatest performance time. Venu (2002: 119) describes Kutiyattam’s UNESCO performance as “the first day’s aesthetic feast,” consisting of a fifteen minute performance of the Navarasas by Ammannur Madhava Chakyar which had audience and actor both “in tears,” followed by a thirty minute presentation of a portion of Surpanakhankam.34 This perception of Kutiyattam receiving special

————— 34 The actors who performed at UNESCO were: Kalamandalam Sivan Nambudiri as Sri Rama,

Margi Usha as Sita, Margi Narayanan as Lakshmana, Margi Sathi as Lalitha, and G. Venu as Surpanakha.

The Translation of Kutiyattam

209

treatment was also no doubt influenced by the selection of Ammannur Madhava Chakyar, with his piercing green eyes and aged authority, as the poster-child of UNESCO’s First Proclamation of Masterpieces brochure, described by Venu (2002: 121) as “yet another feather of glory for Kutiyattam.”.

Through its UNESCO recognition, Kutiyattam became further entrenched in international and national structures of patronage. Granted UNESCO funds in 1999 for its candidature file application, which included the making of a documentary film with internationally renowned director Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Kutiyattam lat-er received extensive financial support from UNESCO Japan Funds-in-Trust for help with the implementation of its action plan from 2001–2007. The most concrete result of the art’s UNESCO recognition on a national scale was the special finan-cial provision made, starting in the 2006 National Budget, for India’s three UNESCO Masterpieces (Kutiyattam, Vedic Chanting, and Ramlila), and the result-ing establishment of a permanent funding scheme by the Akademi in 2007 with the founding of the Kutiyattam Kendra institution in Trivandrum. After years of inter-mittent, low levels of funding, this provided a steady, permanent funding base for the art form from the Akademi, and allowed for the founding of several new training institutions, with both expanded salary and student opportunities, within the span of a few years.35 Kutiyattam thereby became included in a small, elite group of the Akademi’s three permanently state-funded art forms (Kathak, Mani-puri, and Kutiyattam), in what Cherian (2009: 41) terms “model institutions” that the Akademi established predominantly to systematize methods of practical training in performance.36

Identity & Kutiyattam

The literature of identity in both anthropology and folkloristics recognizes that identity is flexible, context-dependent, and multiple, with one individual embody-ing a number of identities at any given point. Exemplifying this in a contemporary Kerala context, Osella and Osella (2000: 10) describe identity as “always multiple, and always composed of interwoven threads of caste, class, religion, party affilia-tion, family, house name, occupation, gender, age and locality.” The exploration of postcolonial and postmodern identities has often applied Derrida’s notion of “différance” to the conceptualization of identities as structures of signification that are embedded in a continuous process of transformation (Sökefeld 1999). They have also recognized the locus of identity—the group or community—as imagined

————— 35 New institutions include the Painkulam Ramachakyar Smaraka Gurukulam, Nepathya, Pothi-

yil Gurukulam, Krishnan Nambiar Smaraka Mizhavu Kalari, and Koppu Nirmana Kendram. The existing institutions of Margi, Ammannur Chachu Chakyar Smaraka Gurukulam and Mani Madhav Chakyar Smaraka Gurukulam were also incorporated into this scheme, how-ever Kalamandalam, as a Kerala state-funded institution, was excluded.

36 Since this time, Sattriya has also been added to this list.

Leah Lowthorp

210

(Anderson 1983), invented (Hobsbawm and Ranger 1983) or constructed (Racine 2001). Folkloristics considers expressive culture such as Kutiyattam a function of shared identity that both emerges from and reinvents a group through performance simultaneously (Noyes 1995). In this section, I trace the thread of shifting Kutiya-ttam identities both constituted and reconstituted through the art’s performance in ever-widening spheres of the region, the nation, and the global. Through examining Kutiyattam artists’ opinions of Kutiyattam as a Kerala, Indian, or global tradition in light of the art’s UNESCO recognition, I argue that participation in showcase festivals on the national and international levels, though perhaps meant to foster a wider identification with the nation or the world, has rather served to both constitute and reinforce a shared artistic group identity among contemporary Kutiyattam artists that is infused with a strong regional identification with Kerala.

Notions of identity and belonging have a complex history in Kutiyattam, and fluidly parallel the fracturing of the art as described earlier into the blurred dicho-tomies of private/public, tradition/modernity, religious/secular, and orthodox/ pro-gressive. With the intense social, political, and economic changes that the Kuti-yattam community has undergone since the latter half of the twentieth century, the art as a locus of group identity has shifted from one in which family, ethnic/caste, occupational and performance identities were merged in the exclusively caste-based performance of the art form, to that of a primarily professionalized, occu-pational identity in which family and caste identifications have largely been re-moved from the equation.37 Kutiyattam performance as a kulathozhil, or traditional caste occupation, persisted exclusively until the art’s democratization in the 1960’s, and represented an identity complex that encompassed the combined notions of caste/ethnicity, family, occupation, and performance which together formed the plurality of Kutiyattam community identities.38 The performance of Kutiyattam as a temple occupation was a right inherited at birth by the Chakyar and Nambiar/ Nangiar castes, with both training and performance usually conducted within the family itself. 39 Such temple performance, still restricted solely to traditional performance castes, continues today to be infused with a strong sense of duty to the larger community and an emotional feeling of solidarity with performers of the ————— 37 However the notion of Kutiyattam as an art of the Chakyar/Nambiar/Nangiar castes still

persists in the contemporary public imagination in Kerala, India, and abroad, despite the fact that the form has been democratized nearly fifty years. Here I employ a hyphenated caste/ ethnic identity based on a body of literature which associates the concept of ethnicity with that of caste in India, see Osella & Osella 2000a; Reddy 2005.

38 In refraining from using the monolithic term “identity” in favor of the plural “identities,” I thereby recognize the plurality and ever-shifting nature of identity that characterizes Kutiya-ttam as a diverse group of individuals.

39 Chakyar is the caste of male actors, while Nambiar/Nangiar are gender-specific names for another caste, Nambiars beings the male drummers, and Nangiars being the female actresses and singing/chanting/symbol accompanists. For more information, see Johan n. d. and Moser 2008.

The Translation of Kutiyattam

211

past, particularly with one’s direct ancestors. It is generally believed that if these yearly temple (adiyantara) Kutiyattam performances are not conducted, some evil will befall the community at large. A sense of duty, self-sacrifice for the sake of the larger community, and a strong emotional connection with performing ancestors was poignantly revealed to me when a traditional performer emotionally recounted the narrative of her great-grandmother enduring eight miscarriages due to her preg-nant performance of the hanging scene from Nagananda, where the actress falls violently to the floor with an unraveling rope around her neck. Despite knowing the consequences, she narrated solemnly, her great-grandmother “performed anyway, out of duty to the community.”

During the course of the turbulent twentieth century in Kerala, many members of these families sought other occupations and ceased performing Kutiyattam, thus rejecting the existing agrarian order and becoming “agents of modernity in new forms of employment” like so many others in Kerala who came to associate their traditional occupations with an increasingly distant past (Osella & Osella 2006: 571). As a result, occupation was divorced from performance, and traditional (ie caste) performers of a professionalized Kutiyattam today are often met with skepticism and even scorn by fellow caste members who tend to devalue their traditional caste occupation in a contemporary context. One traditional young professional actress recounted to me how she dislikes attending extended family gatherings due to the endless questioning of why she continues to perform Kutiya-ttam: “Everyone always asks me why I don’t leave Kutiyattam for another profession. I feel blessed to have been born to my father, who values and therefore taught me the art. If I had been born a Nangiar to anyone else I would not be in the field today.”

Spheres of contemporary identities in Kutiyattam largely correspond with notions of the traditional and non-traditional intersecting with the professional and non-professional, and follow three predominant trends. I include professional and non-professional as categories of analytic distinction based upon conversations and interviews with several artists who conveyed a tension to me between “trained” and “untrained” traditional performers in reference to performance quality. Several were careful to explain that rather than representing a temporal break of before or after temple exit, performance caliber depended upon whether “proper” training had been undertaken.40 To conceptualize this I employ the use of a Venn diagram (see Illustration 1). The first sphere consists of traditional, non-professional performers who perform Kutiyattam exclusively in temples out of a sense of

————— 40 While all contemporary professional Kutiyattam artists, both traditional and non-traditional,

have inevitably been influenced by the aestheticization and standardization undertaken by Kerala Kalamandalam, a value upon aesthetics and power of acting has long been held as an ideal in Kutiyattam, with legends abounding of past performers’ feats of artistic prowess as cause for admiration, and interpreted as demonstrating the power and greatness of Kutiyattam as an art of the imagination.

Leah Lowthorp

212

fulfilling their familial, caste, and/or community duty, and not as a profession, which even if so desired would be impossible given the inadequate remuneration given to artists by temples nowadays (Chakyar 2011).41 The second sphere is comprised of non-traditional (ie non-caste), professional performers of a contem-porary, democratized Kutiyattam who perform exclusively in non-traditional contexts, and whose identity hinges on the unity of professional and performance identities. The space in between, belonging to both spheres, is occupied by traditional, professional performers who perform in both traditional and non-traditional contexts, thus actively negotiating between two simultaneous worlds of “traditional” and “modern” performance that co-exist in present-day Kutiyattam.42 In fact, while active performance throughout one’s lifetime has never been a prere-quisite for continued Chakyar/Nambiar/Nangiar group membership, the active performance of a professional, aestheticized Kutiyattam in a democratized public sphere is a constitutive element of the identities of professional performers of Kuti-yattam, both traditional and non-traditional, today.43

In order to contextualize this plurality of Kutiyattam identities within Kerala’s postmodernity, I explore the art’s relation to Kerala’s regional identity as part of a corpus of state performing arts. According to John (2006: 234), “the land of Kerala, from very ancient times was geographically, linguistically, ethnically and culturally a single cohesive unit,” and Malayalam speakers in these areas main-tained a common cultural identity despite various political demarcations through-out history. While this problematic statement ignores the vast historical and present-day linguistic, ethnic and cultural diversity of Kerala, it represents a wide-spread contemporary “national” imagining of Kerala as rooted in a deep past.44 Evidence used to bolster this imagined continuity include the Keralolpatti, a geographically variable account of Kerala’s history which details the creation myth of Parasuraman lifting the land from the sea by the throwing of his axe, as well as the legend of King Mahabali celebrated in the annual Onam festival, who ruled over all of Kerala as a just king in a mythical time characterized by “no quarrels, no cheating, no robbery, … no castes, and (where) everyone was equal” (Osella

————— 41 See also Daugherty 2011; Johan 2011. 42 For a discussion of how these two contemporary spheres relate to “ritualistic” and “aesthetic”

notions of performance in Kutiyattam, see Lowthorp 2010a; in relation to Nangiar Koothu, see Moser 2011; and in relation to Teyyam, see Tarabout 2005.

43 While traditionally the performance of the arrangettam, or stage debut, was (and is) required to become a full-fledged member of the Chakyar/Nambiar/Nangiar castes, continued group membership did not require every individual family member to actively perform throughout their lifetime, as long as enough members were fulfilling the family’s annual temple perform-ance obligations.

44 For a historical analysis of the emergence of a “pan-Kerala” identity that was upper caste, Brahminical and Sanskritic during the Cera kingdom (800-1124 CE), see Veluthat 2004b.

The Translation of Kutiyattam

213

Traditional, Caste Performers (Nangiar, Nambiar, Chakyar) Non-Professional Temple Venue

Traditional, Non-Traditional, Caste Non-Caste Performers Performers Professional Professional Temple & Public Public Venue Venue

and Osella 2000b: 141).45 This image of King Mahabali associated with universal equality was appropriated by the Communist Party of Kerala in the early 1940’s during their campaign for an Aikya Kerala (United Kerala), which eventually culminated in the formation of Kerala state with the Linguistic Reorganization Act of 1956 that unified formerly British administered Malabar with Malayalam-speaking districts of south Kanara, and the erstwhile princely states of Travancore and Cochin (John 2006).46 Such contemporary (re)imaginings of Kerala are rooted in what Bayly (1998) terms “old patriotisms” of regional bodies that themselves facilitate nationalism in the context of the modern Indian state.

Illustration 1: Venn diagram of contemporary Kutiyattam artists’ identity with respect to caste and professional status

The “traditional” performing arts constitute one of the keystone features of how Malayalis imagine their cultural identity. The founding of the Kerala performing arts institution Kerala Kalamandalam in 1930 played a definitive early role in creating a performing arts canon for the emerging state which further helped to

————— 45 For more information on the Parasurama narrative and the Keralolpatti, see Veluthat 2004a;

2004b, who describes it as a “Brahmanical document aimed at the validation of the Brahma-nical groups through a particular use of history” (2004a: 30). When I asked one artist about her conception of Kerala’s origins, she recounted the Parasuraman narrative and asserted that she believed it to be historical truth.

46 See also Osella & Osella 2000b; Zarilli 1996.

Leah Lowthorp

214

Fig. 7: Margi Usha, Kalamandalam Ramanunni & Kalamandalam Ravindran performing in the 2009 Kerala Utsavam state tourism festival (Photo: Leah Lowthorp).

promote a sense of regional identity. 47 The performing arts in Kerala have continued to play a vital role in the state government’s conscious assertion of a collective Malayali identity through its sustained sponsorship of cultural activities which focus on the performance of “traditional” Malayali art forms during festivals such as Onam and the extensive Kerala Utsavam tourism festival annually show-casing over one thousand artists in numerous state-wide locations. Countless VCDs/DVDs have also been produced featuring Kerala’s performing arts for tourist consumption as part of the State Tourism department’s aggressive “God’s Own Country” marketing campaign.48 In the case of government-sponsored tourist

————— 47 According to Zarilli (2000: 31), Vallathol’s founding of Kalamandalam, ostensibly only for

the promotion and training of Kathakali, also constituted a concerted attempt to preserve the art through promoting it as a marker of Malayali identity in Kerala, and Indian identity on a national stage.

48 Newspaper articles such as those entitled “Kerala Tourism taps new markets” and “Wooing tourists with deep pockets” demonstrate aggressive tourism campaigns targeting non-Malaya-li tourists (see Paul 2009; Staff Reporter 2009). For more information see Osella & Osella (2000); for the role of Kalaripayyat in this process, see Zarilli 1996; for that of Kaikottukali, see Guillebaud 2011; and for Teyyam see Tarabout 2005. Three such Tourism VCD/DVDs have been produced featuring Kutiyattam artists, namely Kutiyattam—Balivadham, Nangiar Koothu, and Mizhavu Thayambaka.

The Translation of Kutiyattam

215

festivals like Kerala Utsavam where the vast majority of the audience-cum-tourist-consumers are Malayali, and proceedings are predominantly conducted in Malayalam with no attempt to translate for the non-Malayali tourist, the ultimate result is the cementing of a regional identity through educating Malayali publics about “their” performing arts, many of which they are seeing for the first time. Kutiyattam has been featured in Kerala Utsavam since its 2007 inception, with a strong emphasis upon introducing Kerala audiences to an art form the majority have never seen before. Tarabout (2005) examines the annual government spon-sored Onam festival, aka Tourist Week Celebration or Kerala’s National Festival, where similar themes are played out. A newly re-imagined Malayali identity foregrounding the performing arts thus emerged in the immediate pre-Independ-ence period with a specific agendas of political mobilization, and continues through the present-day to create an imagined community of Malayalis both within and outside of Kerala in the wider national and international Malayali diaspora.49

Kutiyattam has long been embedded in these webs and processes of regional identity signification. While Kutiyattam families historically performed predomi-nantly only with each other in their respective temple performance territories, occasionally the best actors from across the three kingdoms of Kerala would be summoned to perform together onstage for the Maharaja of Cochin, thus creating and reinforcing through performance the idea of Kutiyattam as a “pan-Kerala” art form.50 This identification of a unified art form with the greater, trans-local entity of Kerala is embodied in contemporary discourse on performance style. While at least two distinct performance styles exist today, a result of both the orally and mimetically transmitted nature of the form as well as its contemporary reinvention at Kerala Kalamandalam, most artists assert that all Kutiyattam throughout Kerala is “basically the same.”51 In-group semiotic communicative devices such as speak-ing to one another in mudra hand gestures, both within and across institutions, serves to further solidify inclusion and group membership within a wider

————— 49 Following Anderson’s (1983) model of “print nationalism,” John (2006: 244) states that “the

concept of United Kerala was promoted, nurtured and propagated by the national minded poets and great writers of the period … (and) the mass media, especially the newspapers, played a decisive role in strengthening the feeling of oneness among the Malayalees.” John also mentions support for the movement by diasporic Malayalis in other parts of India, such as KPS Menon’s 1947 founding of the newspaper “Jaya Kerala” (Victory to Kerala) in Madras in solidarity with the unification movement.

50 For more details, see Chakyar 1975. It was in this wider Kutiyattam forum that inter-family rivalries were often played out, as described to me in tales of tricks such as that of placing chili powder in an actor’s eye-makeup so that he had difficulty performing in front of the Maharaja.

51 For a more detailed description of the form’s reinvention at Kerala Kalamandalam, see Lowthorp 2011b; Lowthorp n.d.

Leah Lowthorp

216

Kutiyattam imagined community. 52 The art form’s inclusion in a corpus of Kerala’s performing arts showcased extensively in Kerala, and at Malayali diaspo-ric cultural programs in other Indian cities and abroad, has further constructed and solidified this identification.

As I briefly noted earlier, later Akademi sponsored programs also served to promote a larger, regionally based artistic identity among professional Kutiyattam artists. While early funding schemes provided assistance to individual gurus to train their students, the 1991 initiated scheme described earlier aimed to benefit the art form and its artists, conceptualized as professional performers attached to performance institutions. This served both to exclude traditional, non-professional Kutiyattam artists from national funding structures, and to redefine Kutiyattam as a cohesive community of professionalized, institutionally-affiliated artists adminis-trated under a common scheme. A crowning event of this scheme was the Kutiyat-tam Mahotsavam festival in Delhi, which constructed a unified, professionalized Kutiyattam as national heritage. Its gathering together of artists from all extant performance institutions at the time, all of which were funded under the Akademi scheme, I argue fostered a greater solidarity among the artists as part of a united artistic community while simultaneously heightening their identity as Kerala artists through their common indexing as such in the nation’s capital.

I now move on to the crux of the matter, that of contemporary Kutiyattam artists’ conceptions of belonging amidst the diversity of identities that characterize the art form today in ever-widening performance contexts. Within each increasing-ly larger performance sphere, Kutiyattam is indexed by the category of belonging directly below it, in what Tarabout (2005) has referred to as different levels of “localities.” For example, within Kerala, Kutiyattam is often described as the “art of the Chakyars,” whereas moved to the Indian national level it becomes regionally marked as “Sanskrit theatre of Kerala,” and at the supranational level of UNESCO, it is indexed both by its Indian national belonging and as a “heritage of humani-ty.”53 As mentioned earlier, the translation of Kutiyattam into national and global heritage simultaneously attempts to create and propagate both national and global identities which may not necessarily reflect practitioners’ conceptions of belong-ing. Both processes relegate perhaps more salient local or regional identities to the background in their highlighting of solidarity within larger imagined structures such as national and global communities. While Kutiyattam has largely retained its regional identity markers in representations at the national level, this constitutes a concerted effort to construct the Indian nation as a colorful quilt of unity in diversity in which the region both produces, and is simultaneously subsumed by,

————— 52 It was a particularly exciting moment of acceptance into the tradition during my research

when artists started speaking to me through mudras and expecting a reply in kind. 53 See Tarabout (2005) for how this notion of various “localities” emerges within the context of

Teyyam.

The Translation of Kutiyattam

217

the nation.54 As locality for the modern nation-state is “a necessary condition of the production of nationals,” such is the nation also a necessary condition of the production of cosmopolitan supranationals (Appadurai 1996: 190). In the suprana-tional context of UNESCO where national identity markers supercede regional ones, I argue an exaggerated national identity is imposed on art forms such as Kutiyattam. While recognition by UNESCO as “the heritage of humanity” promotes a cosmopolitan notion of citizenship by attempting to disconnect citizen-ship from nationality, expressive forms conversely become more strongly tied to their nation-state of origin through the UNESCO structure of recognition via individual state parties. In what follows I explore how Kutiyattam artists’ notions of belonging are situated within the tangled web of these processes of signification.

I admittedly began, for lack of a more informed way to approach the topic at the time, with a flawed line of questioning which inadvertently reinforced the catego-ries of region, nation, and global, and which limited the scope of artist perspec-tives, as I only interviewed professional artists. My question during interviews with approximately fifty professional performing artists including actors, drummers, and senior students was, “Is Kutiyattam a Kerala, Indian, or world tradition, and has your opinion of this changed from pre- to post-UNESCO recognition?” Setting up such pre-established categories from which artists should choose rather than a simple open-ended question undoubtedly impacted artists’ responses, though it is difficult to surmise exactly to what extent. A few artists nevertheless chose a primary or associated identity category independent of those I had offered, namely that of “Chakyar.” Of these, most were in the vein of “because the Chakyars protected Kutiyattam, it has continued through today,” but a few (and notably all of these non-traditional artists) identified Kutiyattam as “a Chakyar traditional art,” and Chakyars as subsequently rooted in Kerala. One artist noted, “if there were Chakyars in other areas of India we don’t know, but we do know that they performed in Kerala as a family duty, and because of this the art form grew and was preserved until the present-day.” Another artist noted that Kutiyattam “was preserved because much earlier it was a Chakyar/Nambiar caste tradition, and it is for this reason that UNESCO recognized it as a traditional art,” markedly situating its caste origins as pande (in a far distant past), and attributing UNESCO’s recognition to this very quality.

While the majority of artist responses declared Kutiyattam as “Kerala’s tradi-tion,” there was a multiplicity of vastly differing formulations reflecting a culture of Kutiyattam artists that is both “multi-vocal and polyphonous” (Van Meijl 2008: 172). These varying responses ranged from Kutiyattam as an “Indian” tradition, to a “human expression,” to combinations of “Kerala and world,” “Kerala, Indian, and world,” “Kerala to Indian to world,” “Kerala and universal,” “Indian to

————— 54 Bénéï (2000: 215) argues that the Indian nation is continually “being constructed by means of

regional inputs.”

Leah Lowthorp

218

Kerala,” and “Indian to Kerala to world” tradition. There was only one artist who replied that Kutiyattam was singularly an Indian tradition, and he used the identifying marker “our”: “Kutiyattam is our tradition, Indian culture’s tradition—after UNESCO recognized it our Indian government gave it support from their budget.” In a completely opposite turn from this however, another artist laughed, “It’s not India’s! It’s a Kerala art itself.” Yet another artist, in postulating why Kutiyattam is presented as an Indian art form when it’s performed abroad, concluded, “It’s only in Kerala, but because Kerala is in India, that’s why they say it is an Indian art form.”

Among these other formulations a few artists replied that they thought of Kuti-yattam as a Kerala, Indian, and a world tradition rolled into one. Of these, one artist, though admitting Kutiyattam to be an Indian tradition, distanced this identification by attributing it to an outside authority while continuing to privilege Kerala, namely: “they say that Kutiyattam is an Indian tradition that came to Kerala, but it is in Kerala that Kutiyattam survived…” Other artists also foregrounded Kerala’s ownership of the form: “it is still Kerala’s, but nevertheless it is now a world-recognized art form,” or “Kutiyattam is still always a Kerala art, but with UNESCO everyone came to know about it.” Most among those who considered Kutiyattam a Kerala, Indian, and world tradition also admitted that their view of Kutiyattam as a world tradition had been influenced by UNESCO recognition. When I asked one young artist if his opinion had been thus influenced, he reflexively replied, “Otherwise I wouldn’t be sitting here talking about it as a world tradition.” Another young artist pinpointed his altered view not only to UNESCO recognition, but also to his 1998/99 participation in the World Theatre Project with theater practitioners from China, Sweden, Mozambique and Italy. He poetically described his conception of Kutiyattam as “human expression with no boundaries,” and then further contextualized it both within India and Kerala: “These are Indian plays, not Kerala plays, but Kutiyattam has survived because only the text is in Sanskrit—the rest is in Malayalam, the mother tongue. You cannot do theater in a foreign language.” One senior traditional artist privileged the identification of Kutiyattam as an art belonging to everyone, further stressing this way of viewing the art form as necessary for its survival: “Kerala is a state in India, and India is one of the countries in the world, so this is Kerala’s, India’s, and the world’s tradition. Kutiyattam is not only ours, it is universal. If you don’t think like that, it will be destroyed … therefore the responsibility to save it, to protect it, is not only mine but yours also, right? I’ve had this opinion both before and after UNESCO recognition.” Another senior artist in a similar vein stated that “you shouldn’t say it is Kerala’s tradition,” and advocated instead that it is only of the world: “This art is for the people of the world, it is everyone’s tradition, because UNESCO recognized it.”

Despite these cosmopolitan oriented formulations, the overwhelming majority of artists replied that Kutiyattam is a Kerala tradition. One laughingly replied, “of

The Translation of Kutiyattam

219

course it’s a Kerala tradition!” and several others employed further stressors such as “only” or “definitely” a Kerala tradition, most of these being both immediate and definitive answers. Another artist even repeated the phrase that Kutiyattam is “only Kerala’s” (Keralathinde mathrom) in ten different ways during her response, just to make sure that I completely understood her. A number of artists employed the term of ownership “our”, as in “our Kerala tradition,” and the majority of these answers did not consider their opinion as affected by the art’s UNESCO recogni-tion. Among these, one young artist commented on the state of the art form as he replied, “Kutiyattam belongs to the people of Kerala, it is a Kerala art form, but nevertheless they don’t know about Kutiyattam.” A senior artist beautifully substantiated her response by saying, “Even if it is a part of India itself, Kerala’s culture is special, with its customs and rituals. In other temples you can go in normally, but here you can only go in after purifying yourself … Kerala has a special beauty. In India if you go to each place, the atmosphere changes signifi-cantly. When you go to the north, east, west, it is really hot and really cold, like that … Kerala’s culture is special, because Kerala’s atmosphere is nice, everyone likes it—it is not too hot, not too cold.”55

Upon expressing my motivations in asking this question to my own Kutiyattam teacher, often a wise consultant during my research concerning strategies and avenues of questioning to pursue within the larger community, I explained that Kutiyattam is no longer confined to the temples, performed now on outside stages all over Kerala, and at the national and international levels. I continued by saying that I wanted to find out how exposure to these larger arenas had affected the identity of Kutiyattam artists, whereupon she interrupted me: “You mean how they tried to affect our identity, but it didn’t work!” We then laughed together as we so often do, sharing in the knowledge of the larger processes of (failed) identity construction at work.

Conclusion

While showcase festivals transform art forms into cultural signs that “constitute the participant for the Festival’s purposes” (Cantwell 1993: 265), thereby recontextu-alizing them, as in the case of Kutiyattam, as “Indian” or “world” heritage, I argue that this particular form of construction is ephemeral, time-bound, and site-specific. In the situated performance of Kutiyattam in such festivals, the art form is indeed transformed by the festival frame in that moment as it becomes, like numerous other embodied performances of cultural heritage, “inscribed in nationalist histories and refigured to conform to those histories” (Reed 1998: 511). However, such transformations are fleeting, with the practitioners themselves often resisting

————— 55 This argument is reminiscent of Handler’s (1988) generalization of formulations of national

existence, namely “We are a nation because we have a culture.”

Leah Lowthorp

220

full incorporation into nationalist (and supranationalist) discourses” (ibid). Despite prolonged processes and innumerable showcase festivals “converting” the art form into both national and international heritage, Kutiyattam artists have largely resisted being fully incorporated into these specific discourses, with artists quickly asserting, “Kutiyattam is a Kerala tradition, our tradition.” Nevertheless, resistance manifested through assertions of regional and artistic identities are tempered, however invisibly or unintentionally, with the degree to which these very processes of national and supranational identity construction have served to both constitute and reinforce Kerala and Kutiyattam as loci of identity.

As part of “the landscapes of group identity—the ethnoscapes—around the world (which) are no long familiar anthropological objects, insofar as groups are no longer tightly territorialized, spatially bounded, historically unselfconscious, or culturally homogeneous,” Kutiyattam artists are reflexive, heterogeneous subjects of a wider, global modernity that cannot be grouped as a monolithic, static entity (Appadurai 1990: 191–2). A multiplicity of identities, subjectivities, and positiona-lities characterize contemporary Kutiyattam, and are reflected in the wide array of responses to my identity query. While it appears that the region has emerged as the predominant locus of Kutiyattam identity, it is important to take into account those minority voices who subscribe to larger national and cosmopolitan frames of belonging.56 It is also pertinent to consider possible results of alternative research approaches—upon interviewing traditional, non-professional artists or given an open-ended question, it is entirely possible that artists may have replied using different categories. Yet regardless of the fact that it appears here that artists’ identities have remained largely rooted within Kerala, Kutiyattam artists continue to actively participate in national and international showcase festivals and structures of recognition and patronage which demand and reflect other levels of identification from the art form than the artists might personally subscribe to. An exploration of practices and negotiation strategies in such situations would doubt-less be an informative, productive endeavour. Nevertheless, like great events and great leaders are in Anderson’s (1983) terms “pearls strung along a thread of narrative” of a nation-state’s legitimizing past, Kutiyattam’s national and UNESCO recognition, concrete cultural capital, continue to locate the art form (with the artists’ full cognizance), as a prominent “pearl of heritage” strung along the necklace of the Indian state’s cultural legitimization and modernity.

References

Abrahams, Roger. 1993. “Phantoms of Romantic Nationalism in Folkloristics.” In: Journal of American Folklore 106: 3–37.

————— 56 Both Van Meijl’s (2008) concept of the “dialogical self” and Appiah’s (2007) discussion of

“rooted cosmopolitanism” may be useful in examining these identity formulations.

The Translation of Kutiyattam

221

Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

Anonymous (a correspondent). 2000. “Koodiyattam in Africa & Asia.” In: Sruti. Sept 2000: 47.

— 2010. “Sakuntalam in Koodiyattom Style to be staged in Paris.” In: The New Indian Express. June 25, 2010.

Antonnen, Pertti. 2005. Tradition through Modernity: Postmodernism and the Nation-State in Folklore Scholarship. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society.

Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. Modernity At Large. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Appiah, Kwame Anthony. 2007. The Ethics of Identity. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Bayly, Christopher Alan. 1998. Origins of Nationality in South Asia: Patriotism and Ethnical Government in the Making of Modern India. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Bendix, Regina. 2000. “Heredity, Hybridity and Heritage From One Fin de Siècle to the Next.” In: Pertti J. Antonnen et al (eds.), Folklore, Heritage Politics and Ethnic Diversity. Botskyrka, Sweden: Multicultural Center.

Bénéï, Véronique. 2000. “Teaching Nationalism in Maharashtra Schools.” In: Fuller, Christopher & Véronique Bénéï (eds.), The Everyday State and Society in Modern India. New Delhi: Social Science Press.

Bhatti, Anil. 2005. “Der koloniale Diskurs und Orte des Gedächtnisses.” In: Csáky, Moritz & Monika Sommer (eds.), Kulturerbe als soziokulturelle Praxis. Innsbruck: Studien Verlag, 115–128.

Blake, Janet. 2001. Developing a New Standard-Setting Instrument for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage: Elements for Consideration. Paris: UNESCO.

Brückner, Heidrun. 1999/2000. “Manuscripts and Performance Traditions of the so-called ‘Trivandrum-Plays’ ascribed to Bhasa—A Report on Work in Progress.” In: Bulletin d’Études Indiennes 17/18: 501–550.

Byrski, Maria Kryzstof. 1967. “Is Kudiyattam a Museumpiece?” In: Sangeet Natak 5: 45–54.