The Task of Testimony: On "No Common Place: The Holocaust Testimony of Alina Bacall-Zwirn"

Transcript of The Task of Testimony: On "No Common Place: The Holocaust Testimony of Alina Bacall-Zwirn"

The Task of Testimony

On “No Common Place: The HolocaustTestimony of Alina Bacall-Zwirn”

JARED STARK

Video testimony of Alina Z., who was born in Warsaw, Poland in1922. She recalls attending an ORT school; German invasion;ghettoization; hunger and round-ups; marriage in 1941; jumpingfrom a train to Treblinka with her husband, having been warned bya Pole of their destination; hiding with a farmer; returning toWarsaw because they feared exposure; living on the Aryan side;returning to her parents in the ghetto because of blackmail threats;hiding in bunkers during the uprising; and deportation to Majdanekin May 1943 and Birkenau several months later. Mrs. Z. recalls herrealization that she was pregnant; establishing contact with herhusband; sharing extra food he supplied with her friends; the midwifetaking her son away immediately after birth (she never saw himagain); a death march to Ravensbrück; transport to Neustadt-Glewe;and liberation. She describes returning to Warsaw; traveling toKatowice and Prague; reunion with her husband in Germany; hersecond son’s birth in Marburg; reunion with her sister; and emigra-tion to the United States. Mrs. Z. discusses her pervasive memories;fears of discussing them with her children, and recently feeling able totalk about her experiences; the importance of learning lessons from thisperiod; and her fears that the lessons are lost when observing events inYugoslavia.1

37

Jared Stark

From 1993 to 1997 I worked with Alina Bacall-Zwirn, referred to aboveas Alina Z., and her family on a book titled No Common Place: TheHolocaust Testimony of Alina Bacall-Zwirn.2 The facts detailed in theabove-quoted bibliographic summary of Alina’s video testimony, fromthe Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale, aretherefore familiar to me. Yet in reading this electronic record, availableto the millions of users of online library catalogues, I cannot help but aska question that I confronted daily while working on No Common Place,namely the question of the relation between Alina’s traumatic past andthe attempt to retell her story, between personal memory and publichistory, whether at the archive or in the form of a book.

If I take the bibliographic summary as a point of departure, it isbecause it seems to offer a coherent formula for this process as it adaptsthe individual and variable voices of the thousands of survivors who havecontributed to the archive to the strict demands of the bibliographicgenre: a fixed number of characters and words, events related inchronological sequence, uniform spelling of place names, the embeddingof searchable key words.3 Above all, there is constant attention to thestatus of these videotapes as testimonies. In the case of Alina Z., thewitness’s experience is related entirely under the aegis of “she recalls,”words carefully chosen to reflect the scope and nature of the testimony.(Consider, for instance, the choice of words in the summary of HellaH.’s testimony: “She recounts her father’s death prior to her birth.”)4

The summary, moreover, records only material testimony. During thevideotaping process, nothing is inadmissible; “the interview,” writesarchivist Joanne Rudof, “belongs to the witness.”5 Nor, of course, arethe original tapes ever edited, abridged or annotated in any way.6 Thesummary, however, serves a different function: it records only theexperiences of the witness herself—no hearsay, no interpretation. Whenthe witness reports that her mother was gassed at Majdanek, that heryounger sister died during the Polish uprising in Warsaw, these parts ofher testimony are excluded from the summary. When she talks abouthow her husband was beaten in the camps, how he risked his life bybegging an SS guard to help his wife, this too will be omitted.

Yet the archival summary is careful to avoid the impression ofcomprehensiveness. In underscoring some of the witness’s prevalentconcerns and some of the important themes raised by the testimony, the

38

The Task of Testimony

archivist gestures towards aspects of the testimony that cannot becontained in a sequential narrative, towards a story behind, around andover the account of historical facts—such as, for instance, the story ofAlina Z.’s past reluctance to testify. It manages, in other words, to alertthe reader to a gap between memory and testimony—a gap that inscribesthe question of memory into the act of testimony, that makes the act ofremembering part of the sequence of events. With this gesture, thearchivist issues an invitation—not only to visit the archive, but also toconsider the question of how to listen to testimony, what to learn fromit and how to retell it. The bibliographic summary becomes more thansimply a fact-finding aid; it represents (along with the notes on which itis based) the initial step in an ongoing process of transmission. It lets usknow that there are elements of the story that it cannot simply retell,that perhaps the witness herself cannot simply retell. Indeed, in the caseof Alina Z. the summary is even forced to break with its own rules ofevidence to deliver, in parentheses, a declarative sentence that rupturesthe syntax of “she recalls”: “(she never saw him again).” What Alinatestifies to here cannot simply be contained in an objective clause. Fromwithin, the summary itself testifies to something that cannot simply bedescribed, summarized, recounted or recalled, something that happensor continues to happen in the testimony itself. (“Never” is also now. Shecontinues not to see him again.) This is something (the summary seemsto say) you will have to witness for yourself.

*

By 1992, when I was introduced to Alina Bacall-Zwirn and her family,I had been studying Holocaust video testimonies and following the workof the Fortunoff Video Archive for four years as a student at YaleUniversity. The Bacall family had also heard of the Archive’s work andfirst approached one of its founders, Dr. Dori Laub, for advice on howto go about publishing a manuscript which had been prepared twentyyears earlier by Alina’s late husband, Leo Bacall, also a Polish Jew, withthe help of a freelance writer, Lawrence Murphy.7 After Dr. Laubreferred the family to my teacher Cathy Caruth, the manuscript reachedme, but its historical inaccuracies and bizarre style made publication an

39

Jared Stark

unlikely prospect. Even more significantly, I learned that Alina, who hadparticipated only minimally in the preparation of the manuscript, had,since Leo’s death and her second marriage, begun to talk more about herown experiences in the camps. She had even started to wonder, herdaughter Sophia told me in our first phone conversation, whether theson she had given birth to in Auschwitz could possibly still be alive.

The shape of what is now No Common Place shifted over the fiveyears that I worked with Alina and her family. But from the start I knewthat we would have to shelve the existing manuscript and start again.Somehow the text would have to be in Alina’s own words, not mine;otherwise I would face difficulties similar to those confronted by thewriter of the first manuscript, whose imaginative and philosophicalframework distorted the Bacalls’ testimony.8 As a non-native speaker ofEnglish, Alina did not have the confidence to write her own story, nordid her children feel that they could undertake such a project unassisted.However, it was agreed from the start that I would not “ghostwrite” thestory; instead, the book would have to be based on Alina’s owntestimony. We also arranged for Alina to visit the Yale Video Archive. Iwas far from certain that I would be able to publish her story, but atleast the video testimony would preserve her story for her family and thepublic.

The initial and, it would turn out, decisive commitment to respectthe survivor’s own words now seems to me bound up in my own clumsyattempts to participate in the cataloguing process at the Yale VideoArchive. For a few hours each week for about a year, my job wasstraightforward: to watch a video testimony and take notes. My job wasto describe what was said on the tape—not to re-order the events, not toisolate overarching themes, but to set down the raw information fromwhich the summary could later be distilled.9 I felt myself, however,gravitate towards an impractical extreme: I wrote down every word.Whatever time the intermediary note-taking process was supposed to savewould be lost in attempts to extract information for the bibliographicsummary from a tangled verbatim transcript. Yet it mattered to me howthe witness said what she said. I feared that any rephrasing of her words,any omissions, even of a stutter, would misrepresent the testimony. Atmany moments, I would even set down the survivor’s words in the firstperson, unwilling to convert “I” to “he” or “she.”

40

The Task of Testimony

My memory of the tapes I watched that year is strangely poor, butthe two episodes I recall clearly seem to touch on some reasons for thisperceived obligation to set down the witness’s words verbatim. In onevideo, a survivor giving his testimony in English recalls a song from thecamps, which he proceeds to sing in a language unfamiliar to me;although it would not have been difficult to find a translator to help meovercome the language barrier, my inability to understand the songstood in for a more serious and perhaps more insurmountable barrier ofexperience, one that suggested that even if I had been able to translatethe song, I would never be able to fathom its meaning.

The second, fuller memory is of a Viennese Jewish woman whodescribes how, desperate to leave Austria after the Anschluss, her familymeticulously typed and retyped a long letter addressed to all the familiesthat shared their last name in a US telephone book. They sent forty-ninecopies of their plea asking the American families to claim them asrelatives and sponsor them for an immigration visa. Some were returnedunopened, marked “address unknown” or indicating that the addresseehad died or moved. But eventually one letter—it turned out to be theforty-ninth one—received a response, and Julianna L.’s family was ableto leave Austria.10

Julianna L.’s testimony came to illustrate for me some of the waysin which listening can become biased. For one, it bore out the cautionsof the most perceptive commentators on Holocaust testimony, who warnthat our need to draw a heroic or redemptive message from survivortestimony is less a mode of listening than a mode of defense against theirrecuperability of the Holocaust.11 Julianna L.’s narrative had all theelements of a potentially heroic tale: the evident resourcefulness of herfather, the eleventh-hour response of the American sponsor, a timelyflight on the eve of the systematic genocide of Austrian Jews. But toattribute her family’s survival to resourcefulness would necessarily implythat those who did not escape had somehow failed, while to celebratethe good sense of their American sponsor would be to forget the scoresof unanswered letters.12

Although I was prepared to avoid imposing this sort of redemptiveclosure on Julianna L.’s tale, it raised another specter for me. For, oddand troubling though it may seem, the witness’s story of survival alertedme to the fact that I had nonetheless come to the act of listening with

41

Jared Stark

certain expectations—expectations that, in the instant before theirimplications were felt, were disappointed by the family’s escape. Watchingthe witness’s testimony with no prior knowledge of its contents (before,that is, it had been catalogued and summarized), I had been waiting,expectantly, for Auschwitz. In the same way that the reader of JaneAusten’s Emma gathers the clues that foretell the heroine’s inevitablemarriage, my listening had been structured by a prior notion of wherethe story would lead, by a generic plot that proleptically cast a shadowover the entire testimony. If the story of Julianna L.’s flight from NaziEurope exposed me to my own ghastly expectations, then the instrumentof her flight—the verbatim reduplication of the letter that led to thesurvival of her family—seemed, on the other hand, to offer transcriptionas a mode of protecting her testimony against my unwittingly distortedmode of listening.

*

The decision to base No Common Place on verbatim transcripts of Alina’stestimony emerged, then, from an attempt to avoid the potentiallydistorting mediation of any less neutral mode of recording her tale. Byminimizing the number of steps between voice and text, the story wouldremain as close to unmediated as possible. It would fall to the reader todetermine how to interpret the grammatical slips, the repetitions, thelapses and hesitations in Alina’s non-native English. Alina’s patentdiscontent with the accuracy of the existing manuscript further suggestedthat a mere reporting of the story would efface important details, that itwould potentially erase or silence a crucial history. Indeed, the history ofher family’s attempts to retell the tale had more or less paralleled abroader movement in the history of the reception of Holocausttestimony—from an initial wave of information immediately after thewar, to relative silence in the 1950s and 1960s, to a wave of renewedattention in the 1970s, to a critical reevaluation of the historiographic,moral and aesthetic assumptions that seemed to shape representations ofthe Holocaust. The Yale Video Archive was itself founded by a group ofsurvivors in response to the made-for-television series Holocaust (1978),which presented what the survivors saw as a sanitized vision. Similarly,

42

The Task of Testimony

the unpublished manuscript completed by Lawrence Murphy in the mid-1970s, “One Small Candle,” cast the Bacalls’ experience in mainlyredemptive terms, as its title suggests. (Its epigraph was a bit of patrioticrhetoric from John F. Kennedy.) Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah (1985), ArtSpiegelman’s Maus (1991) and the Yale Video Archive (though all verydifferent, of course) presented me with important alternative modes ofapproaching survivor testimony, focused on the attempt to allow thesurvivor to speak for him or herself.

However, as Lanzmann, Spiegelman and the Video Archive attest,this attempt would be futile without a corresponding effort to respond.The Video Archive, as suggested above, enables this response not onlyin the format of the testimony, but in the ongoing efforts to create anaudience for this “Archive of Conscience,” as Geoffrey Hartman hascalled it.13 If the summaries, on the one hand, seem to frame andtherefore structure the reception of testimonies, they might also, myexperience with Julianna L. suggested, serve to dispel a listener’spreconceptions and therefore to open the act of listening to the specificityof the survivor’s voice and story. Indeed, if this episode has resonated sovividly it must be because it embodied for me the possibility of ameaningful response. Julianna L.’s story suggested that, as an AmericanJew with no direct familial connection to the Bacalls and whose familyhad lost no immediate relatives in the Shoah—by hearing their appeal,by responding—I could make a difference.

But what would such a response mean in Alina’s case? Wouldn’t itrepresent merely a displaced version of the attempt to redeem theHolocaust? Certainly, for Alina and her family, survival had becomeinextricably bound up with bearing witness. “If I told him [Leo] stay,and be a witness what happened, tell the story, that’s the same thing.Stay alive,” Alina would later tell me (NCP, 15). In the past, physicalsurvival constituted the condition of possibility for testimony: to tell thestory one had to remain alive. But Leo’s and Alina’s postwar efforts topublish their story also seemed to suggest the reverse, namely that todeliver their testimony came to appear as a necessary condition ofsurvival. “And finally realizing that the reason that she survived was totell the story,” Alina’s daughter would put it (NCP, 12). If it was toavoid the attempt to remedy the past, my work with the Bacalls wouldtherefore have to take this positive association of survival and witnessing

43

Jared Stark

into account as well as the larger history of their wish to bear wit-ness—that is, to ensure the survival of their story. It would have to takeinto account, that is, the fact that the Bacalls came to me only underpressure of Leo Bacall’s inability, during his lifetime, to find a publisherfor his story, the fact that my work with the Bacalls was irremediablybelated. But this belatedness, I venture to hope, does not preclude thepossibility of responding, if only to save the story.

The question was, how to save the story? What would it mean tosave the story? It should be clear by now that this would mean notsimply the recording of facts nor merely the conservation of testimony.Rather, it would demand, it seemed, some sort of encounter betweenwhat happened (what Alina recalls, the stuff of the summary) and howthat recollection takes place, some sort of confrontation with the role ofthe book itself in the story the book would tell. One might think of thisas a version of what Lawrence Langer describes as the “cotemporality”of survivor testimony, which, he writes,

becomes the controlling principle of these testimonies, as witnessesstruggle with the impossible task of making their recollections ofthe camp experience coalesce with the rest of their lives. If onetheme links their narratives more than any other, it is the unintend-ed, unexpected, but invariably unavoidable failure of such efforts.14

Langer asks us to focus not on the meanings that survivors might wantto draw from their experience and to communicate in their testimonies,but instead on what evades or disrupts the survivor’s testimony. His workcarries a necessary reminder that video testimony in itself is not history,particularly when the act of testimony takes place some fifty years afterthe event and is therefore subject to the vicissitudes of time.

But this insistence on the gap between memory and narration alsoimplies a hierarchical order. We are asked to hear through or around awitness’s efforts to make sense of the past to a memory—Langer calls it“deep memory”—that emerges in the act of testifying, and that breaksthrough the mediations of the speaker’s own desire to bring the past intoconformity with the present.15 While there is ample evidence thatLanger’s cautions are not misplaced—that the drive to redeem theHolocaust is strong with us—I wonder as well if the survivor’s own

44

The Task of Testimony

desire to tell her story in certain terms (be they redemptive, heroic,martyrizing, etc.) does not call for further discussion. At least, this wasthe question I confronted in my first taped discussion with Alina. Herfirst words to the tape recorder flew against what I had learned and hadthought to be my obligation in approaching Holocaust testimony, theobligation not to seek redemptive closure or to heroize: “I want myhusband to appear as a hero because I stayed alive only because of him.”

If the visitor to the video archive might consciously and criticallylisten for the witness’s struggle with the discrepancy between “the campexperiences” and “the rest of their lives,” it became clear that any writtenarrangement or compilation of transcripts would be subject to differentconditions. There would be no excuse in a redacted text, however“faithful” it claimed to be to the testimony, to maintain this discrepancy.If Langer was right, Alina’s testimony would be unable to sustain theheroic image she began with; and yet, to allow that failure to remain onthe page would be to shift the emphasis to what Langer calls “unheroicmemory” at the expense of Alina’s express purpose.16 Even the decisionto intervene as little as possible would therefore influence the shape ofthe story. To translate Alina’s testimony to another medium—to bearwitness for the witness contrary to Paul Celan’s bleak observation,“Nobody / bears witness for / the witness”17—what would this thenmean?

The cue came again from Alina when, after our first meetings inJanuary 1993, she decided to read her daughter a text she had writtena few months earlier, just before Rosh Hashanah. She wanted to translateit for me from Polish into English, but for some reason she did not tellme she had done any writing during our meetings. When I later askedfor a copy of the text, she told me that it had been lost. Her efforts toset her story down on paper and her lost text added another chapter tothe story that would become a second focal point for the book: the storyof her story. For however she might choose to relate the events of thepast, it was clear that the very desire to create a book emerged out of acomplex history that remained to be told, one of a series of interruptedattempts to testify. As we embarked on our joint project, the missing textentered as something of a challenge—a refusal on Alina’s part to fix herstory in any single form and a warning that any retelling would necessari-ly fail to record her true past.

45

Jared Stark

The problems raised by this missing text became the starting pointfor the book: Alina begins her story in and as an act of translation, butthe text she translates is itself lost. Her translation, then, cannot be heldup against an “original” or “true” text, but rather suggests an analogybetween the task of translation and the task of memory, both of whichfalter against the “meaning” of Alina’s experience:

I start preparing, and buying and buying and buying for theholidays. Food, mostly. I’m buying food to eat.

And like, I feel, I don’t know. I’m buying so much, sometimesI think that the war is coming. Any day it is going to break out andyou have to prepare food.

I realize, you know... nieswiadomie... I don’t know how to sayit... not knowing that... not knowing something happened to me,something is bothering me, and I really can’t find, you know, Ican’t find the place, i nie wiem why. (NCP, 1)

Perhaps Alina declined to give me her written text out of a lack ofconfidence in her writing, the symptom of an education cut short by theHolocaust and of a forced exile from her native tongue (even though shehad written in Polish). Although she knew that what had happened toher was important—that it had to be told—she placed less value in herown way of saying things. My academic credentials, it seemed, wouldallow me to give her story the form it deserved—to make it “soundgood.” But also, her testimony here suggests, it was due to a divorce sheseemed to feel between her experience and her mode of expression. The“meaning” she cannot find indicates on the one hand a problem intranslating from Polish to English, while on the other hand it gesturestowards a meaning inarticulable in any language. If my credentials weresupposed to allow me to “understand” her story, and to help othersunderstand it, Alina’s testimony extraordinarily begins here with theundermining of the possibility of understanding. “I can’t understand. Ican’t believe,” her text concludes (NCP, 3). Not “you can’t understand,”a phrase that would erect a wall between those who were there and thosewho were not. Instead, “I can’t understand. I can’t believe.” The storyis the story of this incomprehension.

46

The Task of Testimony

Crucially, however, this story of incomprehension is related here inmy absence, in a scene where Alina and her daughter are alone,recording their conversation on tape. During our initial interviews,Alina’s daughter, Sophia, had listened more or less in silence as Iinterviewed her mother. Sometimes, but rarely, Alina would turn toSophia as she spoke, and sometimes, but rarely, Sophia would ask hermother direct questions. As Alina translates her Polish text, however,Sophia became a direct participant in her mother’s testimony. The lossof the written text meant that I could never turn to an outside authorityor translator to interpret Alina’s words. Instead, Sophia enters the storyas the audience to her mother’s extemporaneous translation, as atranslator herself and as a witness:

ALINA: This is okropna prawda. How you say? This is...SOPHIA: Terrible truth.ALINA: This is terrible, terrible truth. (NCP, 3)

What was (and is) at stake in this joint translation emerges in theensuing conversation between mother and daughter, which revolvesaround the problem of telling. The very morning of the day when Sophiaand Alina recorded this tape (9 January 1993), Sophia had told me thatthere were parts of her mother’s story that she had never known, andthat even those parts she had known had reached her only indirectly:

I kept thinking all these years that I knew inside what happened,and I knew some of the stories, not because I asked them or notbecause I was told them, but only sometimes during the holidaysor when my parents had company over, especially other survivors,they would start talking about their accounts in the ghetto andtheir accounts in concentration camps. My father would basicallytalk about it a lot more than my mother. My mother would getangry at my father. [...] But I would sit there with eyes open, andlistening and listening because I wanted to get out as much as Icould. Too afraid to ask questions [...]. (NCP, 4)

I had become “company,” a catalyst to Alina’s testimony, with Sophiaagain an eavesdropping, and protective, presence. (“Mom, are you

47

Jared Stark

okay?” she would ask repeatedly while Alina spoke to me.) She evencharacterizes her childhood efforts to learn her parents’ histories, in anostensibly inadvertent phrase, as a need “to get out as much as I could,”as if testimony could externalize what she knows inside, as if it couldhelp her escape (get out) from this haunting knowledge. But after I leftAlina’s home that day, after Sophia had herself borne witness to her ownexperience of events she had never directly experienced, mother anddaughter engaged in a different kind of dialogue, centered on theircommon failure to know what happened. “I don’t know how to say it...not knowing that... not knowing something happened to me” (Alina).“I kept thinking all these years that I knew inside what happened”(Sophia). If Sophia once thought of her mother as concealing an alreadyknown past, this encounter suggests that the untold story (“whathappened”) is not so much deliberately concealed by Alina as it is not(yet) known, not fully available to her. When Sophia begins to askquestions, the distinction between “inside” and “outside” knowledge,between secrecy and disclosure, breaks down; consequently, she is ableto claim her right to hear the story. “I want to hear it,” she says. And inpressing her demand, she becomes a participant in the process of bearingwitness, one who will herself “remember forward.”18 Indeed, instead ofleaving the task in my hands, Sophia took it upon herself to transcribea large part of her mother’s testimony. (Perhaps tellingly, it was onlywhen she became pregnant with her first child that she found she nolonger had enough time to work on the transcripts.)

The transmission of the story between mother and daughter,however, does not take place independently of the attempt to bear publicwitness. The tape recorder is on as they speak, and Sophia, if sheenergetically pursues her parents’ wish to publish their history, does soalso in the interest of her own desire to hear their testimony. This is not,then, the story of a mother and daughter that is simply handed down tome and to the reader. Rather, an audience is already inscribed in theprocess of testimony and its transmission. As they struggle with themechanics of the tape recorder, Alina and Sophia also struggle with howthe story will come across:

ALINA: Here is like, that’s all what’s left for me, you know, mychildren, that’s what is... zostało... how you say it? Left over...

48

The Task of Testimony

SOPHIA: That’s all I have left.ALINA: That’s all what I have left, that’s all what I have left. I

have to change that.SOPHIA: Explain that you want to expand on that point, that

your children are all that you have left.ALINA: My children, yes... but this is something no good.

You’re stopping here...SOPHIA: You’re recording, you push two to record.ALINA: Now?SOPHIA: Yes, you’re on the tape. Explain what you want to

explain.ALINA: Oh, I see. I didn’t understand... (NCP, 4)

The literal question of how to record the testimony (of how the taperecorder works) intersects here with a larger question about how Alina’stestimony will appear to others, what points need clarification and, inparticular, what place her children will have in her testimony and in hersurvival. Faced with her mother’s uncertainty as to how her story shouldbe recorded, Sophia provides her mother with both technical andnarrative assistance, as she urges her to fill in what she sees as gaps inher mother’s testimony. She is, on the one hand, helping to translate hermother’s words, but the difficulties encountered in the act of translationalso open a space for Sophia to mark her own place in the story(“Explain ... that your children are all that you have left”), a place whereAlina’s survival of the Holocaust and her children’s story seem tointersect, to the point where the children themselves appear as survivors.Explain, one might ask, to whom? This delicate and perhaps unanswer-able question marks the way that the children’s participation in theproduction of their mother’s testimony might not only serve toencourage the relation of a history that might otherwise have remainedsilent, might not only serve to enable the preservation and transmissionof their mother’s story, but might also confront a more complicatedrelationship between the act of testimony and the community in whichthat act occurs and on which it depends.

*

49

Jared Stark

I want to conclude by addressing some of the implications of thisdependence as it appears at one of the turning points in Alina’s story,when she and her husband jumped from a Treblinka-bound train. Oneof two main focal points for Alina’s story of her husband’s heroism, thisepisode was depicted in the early manuscript, “One Small Candle,” as amoment of an almost existential liberation: “THIS WAS FREEDOM.”To the extent that this upper-case proclamation reflected Leo’s andAlina’s own view of their experience, the episode would have to behandled carefully. Leo’s actions in particular represented for Alina aheroic and exceptional act—a moment when her husband saved her life.Each time Alina told the story—in our first interviews at her home inFlorida, again at the Yale Video Archive and then in the presence ofSophia and her oldest brother George—Leo’s heroism entered intoAlina’s narrative. But by the same token it raised acute interpretiveproblems, not only concerning the moral value of the episode but alsoconcerning its reverberations for other parts of Alina’s story, for hersurvival and for her children. The passages that follow—which make upthe sixth chapter of No Common Place, “A Small Opening”—reflect myattempt to convey the charged significance of this episode.19

April 21, 1993New HavenFortunoff Video Archive at YaleALINA: I didn’t have any help from anybody. I was hiding, I

was scared, especially when we jumped from a train and we didn’thave a place where to go. We are free, we are not in Treblinka tobe killed, and we didn’t have any place to go.

* * *ALINA: You know, we were with our friends from school, all

young people. And the whole wagon was so many people, youngpeople.

And we told them... because when my husband... they put ourtrain on the side and they were waiting for the middle of the nightto start us to move. And my husband saw a guy who took care ofthe station, and he ask him, could you tell me where we are going?

50

The Task of Testimony

And he said, if you could, save yourself, because you are goingto Treblinka, to death camp.

DANA [Kline, interviewer]: Did you ever hear of Treblinka before?ALINA: No. You know, some people used to receive letters,

cards, that they are working, you know. The only thing, very latewe find out that they killing us. I didn’t think about gas orsomething like this. And then you get experience.

January 8, 1993Tamarac [Florida]ALINA: There were my schoolgirl friends. One was married and

the other one was like a sister of my friend’s husband, so we wereanother two couples, three couples altogether.

My husband took a handkerchief and put a knot in onecorner, and covered it. And he said, whoever is going to pick upthe knot, will be the first to jump.

SOPHIA: I always thought it was straws, I always thought it waslike a short stick.

ALINA [demonstrates with a paper napkin]: No, like this, a handker-chief. One of his friends picked up the knot, and they started to filethe bars. They opened it. It was a very small opening, like the trainsfor cows, you know, the cattle cars.

So he is going out, and he was scared, and he said he cannotdo it, and he came back. So I remember my husband, the firstthing he said is, okay, I am going to do it. He pushed him away,and he went out.

And he said—we were changing in the train—and he said, putsomething warm, like I have high boots and pants, and he lookedat me and said, okay. And he went out, and then he comes back.

And he wants to go after him, his friend, and he pushed himaway. He said, give me my wife first.

So they picked me up, and he held himself with one hand onthe wagon and with the other he took me from the hole, and hetook me like this, and we were standing together but between thetwo wagons. You understand how was that? Between the two cars.Do you have a problem to understand me?

51

Jared Stark

April 23, 1993U.S. Holocaust Memorial MuseumWashington DC

ALINA: I don’t remember if I came first with the feet or withthe head.

SOPHIA: Ma, I didn’t hear how you started to tell George.How did you do it again? How did you actually... how did daddy...

GEORGE: Dad filed through the bars.ALINA: Daddy was first who wants to go, because he was

afraid, the other guy... He was, daddy, here with the hand, holdinghere, and the other hand he hold here, someplace. And he pushesme... and he holds me and then... he holds me like this and pullsme someplace, I don’t know where. And I was holding here, andthis hand, daddy holds my hand, and daddy’s hand was by thesecond car...

SOPHIA: There were two cars connected...ALINA: Two cars connected, trains, not trains, wagons, cars.

And that’s where we were... I think was the... you know, theconnection. This is the connection. I think we were on thisconnection.

GEORGE: Yes, that’s where it would connect.ALINA: See, that’s on this connection, and daddy was holding

the other hand here, I was holding one here, and we jumped.But I don’t remember how, with feet or with my head. With

my feet I think I came out.

April 21, 1993New HavenFortunoff Video Archive at YaleALINA: Not a window, it wasn’t glass. It’s just like wires. My

husband went, and then he said, give me my wife. His friendwanted to go after him, he said, no, give me my wife. He wassomething. He was holding himself with one hand. You know, youhave a handle on the train. And with the other hand, he took melike this from the opening and pushed down. Then he moved andhold me by one hand, and then said, catch the other. He move

52

The Task of Testimony

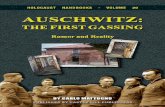

At the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, Alina, George, Sophia and I standbeside a freight car once used to transport Jews from the Warsaw ghetto toTreblinka. As Alina recounts how she and Leo made their escape, I point to thebar that runs vertically along the corner of the car. Courtesy of Sophia Bacall-Cagan.

53

Jared Stark

and he told me to take it. We were both like this, holding here andholding his hand, and he was teaching me how to jump.

He said, jump in the same direction the train is going, andjump far away. We were talking and he said, are you ready? And Isaid... I don’t know... I was like ready for everything.

All of a sudden, we saw a light, like a station. That was astation before Treblinka, I think was the name Tluszcz, and he saidwe had to jump, are you ready? [Tluszcz is located about twenty miles

northeast of Warsaw and twenty-five miles southwest of Treblinka.]I said, yes. He pushed me, I fell and I rolled myself to the

ditch, and then I hear shooting and shooting because they were onthe top of the train.

“One Small Candle,” p. 40–41We stood between the cars balancing ourselves against the

sway and pitch of the train. My wife did not know how to fall, andI demonstrated how to hit the ground with her shoulders and roll.I thought she could hear me. I thought she understood. Then Iheld her, and kissed her, she closed her eyes and I pushed her intothe night. Then I made my leap into freedom.

I felt the impact of the roadbed against my shoulders, and Irolled over and over, for the first time I heard shots. I had lost mybread bag in the fall, then more shots and the train was rushingpast—but THIS WAS FREEDOM—this was what freedom felt like.[...]

Others had jumped after us. All those had been shot. I foundtheir bodies after the train had passed. Further down the track Ifound my bread bag, and then I walked until I found my wife. Shewas cut and bruised, but alive. We walked back into the woods andthrew up by a stream. Then there was diarrhea. We had seen oneman curled up dead in a fetal position. This was all freedom and allstorms of war and all nights, and I took off my shirt and ripped itfor bandages for the cuts on my wife’s arms and side. We waited bythe stream, stunned with exhaustion.

54

The Task of Testimony

April 21, 1993New HavenFortunoff Video Archive at YaleALINA: I was there like in a dream. I didn’t know where I am.

I didn’t know what to expect. Nothing. I just hear my voice calling.My husband, he jumped after me, but the train was going so fastthat he find himself far away from me. And he was coming slowlyand calling, Ala, Ala, Ala.

And I said, yes?He said, so how you been?I said, I don’t know even. (NCP, 29–33)

As Alina attempts to recount the moment when her husband saved herlife, something happens—something that does not so much deny theheroism Alina attributed to her husband as set it in the background,rendering it irrelevant. There is no place in this episode for anythingresembling moral judgment, at least to the extent that to maintain thepossibility of moral action necessarily implies the possibility of immoralaction. The randomness of the lottery makes it impossible to interpretthe tale as one of heroic choice. The excerpt from “One Small Candle,”despite its imminently redemptive tone, seems to recognize this in thedescription of “one man curled up dead in a fetal position.” Alina’s ownnarrative is also haunted by an unheroic story, one where she beginsalone and ends on a note of apparent loss and disorientation.

In this light, a celebration of escape or “freedom” would appearonly cruelly ironic. The events she relates here bear witness instead to thecollapse of any distinction between “winner” and “loser,” survivor andvictim. They also seemed to defy mere narration, with Alina each timeinvolving her body in her storytelling, whether in her home with herdaughter and me, in the US Holocaust Memorial Museum or in the YaleHolocaust Video Archive. In each of these retellings, Alina began toshow, with her hands and props, how things took place: “here,” “there”“like this.” The history at stake here is not simply a history in the past,but one that is in the process of being “made” at the very moment ofremembrance and transmission. The question is not simply “whathappened,” but rather, what is happening. “This is the connection”: shestruggles, both in the scene and in its retelling, to make a connection,

55

Jared Stark

with her husband and with her children, between her husband and herchildren, between the family’s history and the public.

The immediacy of this mode of testimony as well as the problemsit engages are particularly striking in the scene at the US HolocaustMemorial Museum. As in the opening chapter, where Alina and Sophiaspeak into a tape recorder, the possibility of public commemoration spursthe attempt to retell and reenact the past. The photograph thataccompanies the scene at the museum was taken by Alina’s daughter,Sophia, and the transcript of the conversation at the museum is from avideotape filmed by her eldest son, George. Although I recorded mostof our visit to the museum on audio tape, at this crucial moment mytape recorder was off. Instead, Alina’s children, as they try to piecetogether their parents’ past, here took over the responsibility ofdocumenting their mother’s testimony. The lost story of the father isrehabilitated here at the intersection of family and public memory.

The fact that the freight car displayed at the US Holocaust Museumwas indeed used to transport Jews from the Warsaw ghetto to Treblinkaanimates this “connection.” It is, in other words, possible that this wasthe very car from which Leo and Alina escaped. But this possibility alsopoints to the larger probability that this was not the same car; that,indeed, this “connection” would have been made even if the freight cardisplayed had traveled an entirely different route. (“Yes, that’s what wecame by train [to Majdanek]. With the same train that will probably bein Washington D.C. Museum,” Alina said in one interview [NCP, 44].)

If the museum allows the children to approach their parents’histories—and their own histories—in an unprecedented way, it does so,then, only at a moment of both connection and disconnection, a momentat which the transmission of a particular story from parent to child occursthrough the mediation of cultural remembrance. Whatever is transmittedhere is transmitted through the museum, the museum as a place wherememory is constructed. In this light, the freight car displayed at themuseum could never take the place of the “original” car; in fact, whenit was given by the Polish government to the US Holocaust MemorialMuseum, layers of postwar paint had to be stripped to “restore” the carto the appearance it might have had as it rolled down the tracks toTreblinka. The artifact is already a product of a contemporary idea of itsfactual nature, a representation of itself.

56

The Task of Testimony

On the one hand these mediations seem to de-authenticate thehistory being transmitted here—in that they undermine the immediacyof Alina’s narration, in that they complicate the relationship betweenevent and testimony. I want to suggest, however, that it is in this veryestrangement, in the performance of an impossible obligation to “see theconnection,” that Alina’s history becomes transmissible. To state mattersdifferently, it seems that the possibility of a connection emerges at a siteof uncertainty—uncertainty as to precisely how Alina’s retelling is relatedto the event she retells, uncertainty as to how to interpret her testimony,uncertainty as to how it is being received. In Alina’s narrative, theseuncertainties most strikingly revolve around her preoccupation withwhether she “came first with the feet or the head”—a question that inits obstetric connotations connects the difficulty of accurately establishinga historical fact with the more engrossing problems of a traumaticmemory. Alina’s words raise the pressing question of how to read thismoment of testimony—as a simple failure of recollection, as the intrusionof a conventional metaphor of rebirth (or of the more haunting imageof a corpse in a “fetal position” employed by “One Small Candle”) or asthe echo of the trauma of bearing a child in Auschwitz. What appears tobe a moment of the breakdown or loss of memory might then equallybe read as a moment of surplus: the past is not forgotten but ratherexceeds the bounds of a linear, factual narrative.

My arrangement of the testimony sought to reflect what I heardwhen listening to Alina’s words. I wanted to convey both the specifictexture of Alina’s delivery of her story and the ways that a gap in herstory or a seeming insufficiency of memory might become “a smallopening,” a place where a reader may begin to hear the questions thatimpinge on the act of testimony and its interpretation. The chapterreproduced above therefore begins with a statement that is also aquestion, or even perhaps a plea: “I didn’t have any help from anybody.”And it proceeds to explore the ways in which this abandonment,devastating and irrecuperable, might, perhaps, find a response at themoment of bearing witness.

These questions are foregrounded, of course, by my editorialdecisions. This is one of the moments in the book when my role inshaping the story is most obtrusive—as is underscored by the photographshowing my shoulder and hand. The apparent question is whether my

57

Jared Stark

hand, as I called on Alina to speak to her history and to our own—as Iarranged her testimony, as I prepared it for publication—whether myhand, whether this book, could, with any degree of justice, help “see theconnection,” whether in pointing out where the connection took placemy hand serves a guiding function or just gets in the way.

My response, as already discussed, was to cling to Alina’s verbatimtestimony even while sounding out the apparent gaps in her narrative,the inconsistencies and failures of memory and the vicissitudes of herbroken English for the emergence of a transmissible history, one thatmight take into account the pressures exerted on the witness both bytraumatic memory and by the very task of testimony. In the book,verbatim testimony is set in a form that recalls two traditional genres ofmemory writing, the personal commonplace books of Anglo-Americanbelletrism and the collectively authored yizker-bikher or memorial booksof East European Jewish communities, books in which Holocaustsurvivors (and prior to the Holocaust, survivors of pogroms) sought tocommemorate their decimated communities.20 No Common Placeborrows from these genres the possibility of establishing personal andcommunity history through modes of collective authorship. The echo ofthese conventions also underlines the fragility of memory, as well as acompensatory belief in the durability of the book.

If these genres offer a structure for memory writing, oral testimony,with its lapses and digressions, with its spontaneity, seems almostantithetical to the quoted material, crafted tales and folkloric impressionsthat are the staple of commonplace and memorial books. Whetherintended as self-edification or as a testament to future generations, thesevolumes are composed with a view towards rereading; they are composed.No Common Place is equally composed, it is equally invested in the taskof commemoration, and it is equally, as Alina made clear in the book’sdedication to her husband and to their lost relatives, a kind of tomb-stone. Running counter to the lapidary epitomization of a life performedin epitaphic writing, however, is the volatility, the vulnerability, thediscomposure of the voice. A commonplace book or memory bookcomposed primarily of transcripts brings the role of reading to theforeground, for it imposes on the reader a text that is at once fixed andunstable, redacted and in process. To assume the task of receiving thissort of testimony—whether in the video archive, the museum or the

58

The Task of Testimony

memory book—might then entail an encounter not simply with a closed-off past or a static, fossilized archive, but rather with a continuing historyof testimony, a history that emerges and speaks to us from the intersticesbetween various ways a single event might be told, between variousmodes of memorialization and between various modes of response. Toassume a place in this history, then, might also be to allow the story toteach us how to listen to it, to teach us how to inhabit a momentwithout a predetermined future: “I didn’t know what I have to expect.Nothing. I just hear my voice calling.”

NOTES

1. Research Libraries Information Network bibliographic record of Alina Z.Holocaust Testimony (HVT-2045), Fortunoff Video Archive for HolocaustTestimonies, Yale University Library.

2. Alina Bacall-Zwirn and Jared Stark, No Common Place: The HolocaustTestimony of Alina Bacall-Zwirn (Lincoln, NE, 1999) (hereafter cited in the textas NCP). Alina Bacall-Zwirn died in April 1997, one month after the completionof the manuscript of No Common Place.

3. Although some aspects of the archivist’s practice as described here areshared with other archives, my focus here is the Fortunoff Video Archive forHolocaust Testimonies at Yale. I gratefully acknowledge the assistance of JoanneRudof, archivist there since 1984.

4. Research Libraries Information Network bibliographic record of Hella H.Holocaust Testimony (HVT-1562), Fortunoff Video Archive (emphasis added).

5. Joanne Rudof, “Witness Accounts of the Holocaust: Video Testimony?Interview? History? Factoid?” (paper presented at the Social Science HistoryAssociation Annual Meeting, 1996), 3. In accordance with this principle, theFortunoff Video Archive sets no limits of time or scope during videotaping andpractices “nondirective” interviews. This method and its implications have beendescribed in compelling terms by one of the archive’s founders, Dori Laub, andby its faculty advisor, Geoffrey H. Hartman; see Laub, “Bearing Witness or theVicissitudes of Listening,” in Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub, Testimony: Crisesof Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History (New York, 1992),especially 71–74; and Hartman, “Learning from Survivors: The Yale VideoArchive,” in idem, The Longest Shadow: In the Aftermath of the Holocaust(Bloomington, 1996). See also Nathan Beyrak’s description of the idealconditions for Holocaust video testimony at a related project in Israel, “The

59

Jared Stark

Contribution of Oral History to Historical Research,” International Journal onAudio-Visual Testimony (June 1998): 15–20. Furthermore, witnesses are giventhe option of restricting access to their testimony (for example, by limiting it toeducational use or by deferring access until a fixed date) and are advised of allrequests for permission to publish material from their testimony.

6. All testimonies recorded at the Fortunoff Video Archive are recorded ontwo sets of videotapes, one master set and another used only to create highresolution copies. A third set of viewing copies is housed in the main library,while the two original sets are stored in an environmentally controlled vault.

7. Lawrence Murphy, “One Small Candle: The True Story of Alina and LeoBacall” (unpublished manuscript).

8. My initial impressions of the manuscript were confirmed by Alina’s ownopinions of the text. I will give here just two examples. First, in a pseudo-allegorical mode, the manuscript throughout refers to Jews only as “members ofthe Tradition,” to Nazis as “enemies of the Tradition,” to the Warsaw ghetto as“the Walled City.” Second, in narrating Alina’s childbirth in Auschwitz, themanuscript has her, in the first person, compare her experience metaphoricallyto the metamorphosis of a butterfly—a moving image, perhaps, but one thatAlina entirely disavowed to me.

9. These notes are made available to viewers and also serve as finding aids.More recently, they are entered directly into a computerized, searchable database.

10. Julianna L. Holocaust Testimony (HVT-884), Fortunoff Video Archive.11. See especially Lawrence L. Langer, Holocaust Testimonies: The Ruins of

Memory (New Haven, 1991) and Preempting the Holocaust (New Haven, 1998).12. One of these, Julianna L. recalls, was even addressed to a US senator.13. Hartman, The Longest Shadow, 144. Irene Kacandes also offers a useful

consideration of the role and responsibility of interviewer and audience in “‘YouWho Live Safe in Your Warm Houses’: Your Role in the Production ofHolocaust Testimony,” in Dagmar Lorenz and Gabriele Weinberger, eds.,Insiders and Outsiders: Jewish and Gentile Culture in Germany and Austria(Detroit, 1994), 189–213.

14. Langer, Holocaust Testimonies, 3.15. See also Henry Greenspan, On Listening to Holocaust Survivors: Recounting

and Life History (Westport, CT, 1998), xiii, 9 and passim. Greenspan also offersan important discussion of the difference between conducting repeated interviewsof survivors and the usual format at the Fortunoff Video Archive and othersimilar projects where follow-up interviews are infrequent. In Greenspan’s terms,it is over the course of several interviews with a survivor that listeners stand thebest chance of understanding the influence of the “context of recounting” on thestories survivors tell.

60

The Task of Testimony

16. The implications of this double bind for the factual status of survivors’testimony are explored by Dori Laub in suggesting that one survivor’s testimony,in and through an apparent factual error, testifies to another kind of truth, thetruth of the very unbelievability of what she had witnessed and the possibility, inher testimony herself, of “bursting open the very frame of Auschwitz.” To writethis witness’s story in such a way that “corrected” her “mistake” would be ineffect to re-imprison her. See Felman and Laub, Testimony, 59–63.

17. “Niemand / zeugt für den / Zeugen.” From “Aschenglorie” (Ashglory)in Paul Celan, Breathturn, trans. Pierre Joris (Los Angeles, 1995), 179.

18. “The promise of extending experience from past to future via thecoherence of the stories we tell each other, stories that gather as a tradition—thatpromise was shattered. To remember forward—to transmit a personal story tochildren and grandchildren and all who should hear it—affirms a desegregationand the survivors’ reentry into the human family. The story that links us to theirpast also links them to our future.” Hartman, “The Book of Destruction,” in TheLongest Shadow, 122.

19. Each excerpt is preceded by an indication of its source. Asterisks separatenonconsecutive segments of the same source. Ellipses indicate pauses, hesitationsand interruptions that are part of the transcripts. Bracketed ellipses indicateeditorial omissions. Brackets indicate my explanations.

20. See Jack Kugelmass and Jonathan Boyarin, eds., From a Ruined Garden:The Memorial Books of Polish Jewry (New York, 1983).

61