The spouse of the female manager: role and influence on the woman's career

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

8 -

download

0

Transcript of The spouse of the female manager: role and influence on the woman's career

Gender in Management: An International JournalThe spouse of the female manager: role and influence on the woman's careerSuvi Välimäki Anna#Maija Lämsä Minna Hiillos

Article information:To cite this document:Suvi Välimäki Anna#Maija Lämsä Minna Hiillos, (2009),"The spouse of the female manager: role andinfluence on the woman's career", Gender in Management: An International Journal, Vol. 24 Iss 8 pp. 596 -614Permanent link to this document:http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17542410911004867

Downloaded on: 24 September 2014, At: 05:12 (PT)References: this document contains references to 55 other documents.To copy this document: [email protected] fulltext of this document has been downloaded 1292 times since 2009*

Users who downloaded this article also downloaded:Ronald Burke, (1999),"Are families a career liability?", Women in Management Review, Vol. 14 Iss 5 pp.159-163Irene Chew Keng#Howe, Ziqi Liao, (1999),"Family structures on income and career satisfaction ofmanagers in Singapore", Journal of Management Development, Vol. 18 Iss 5 pp. 464-476Ronald J. Burke, (1997),"Are families damaging to careers?", Women in Management Review, Vol. 12 Iss 8pp. 320-324

Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by 306933 []

For AuthorsIf you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald forAuthors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelinesare available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information.

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.comEmerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The companymanages a portfolio of more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes, as well asproviding an extensive range of online products and additional customer resources and services.

Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committeeon Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archivepreservation.

*Related content and download information correct at time of download.

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

The spouse of the femalemanager: role and influence on

the woman’s careerSuvi Valimaki and Anna-Maija Lamsa

School of Business and Economics, University of Jyvaskyla, Jyvaskyla,Finland, and

Minna HiillosHSE Executive Education Ltd, Helsinki School of Economics, Helsinki, Finland

Abstract

Purpose – This paper aims to examine the role of the spouse, specifically the husband, for thewoman manager’s career by focusing on the gender role construction between spouses, and therelationship of these roles to the woman’s career.

Design/methodology/approach – The topic was investigated within a Finnish context byanalyzing the narratives of 29 female managers. A common feature among the women was theirmanagerial position and extensive work experience. All the women had or had had one or morespouses in the course of their careers, and all but one were mothers, mostly of teenage or adultchildren.

Findings – A typology distinguishing five types of spouses was constructed: determining,supporting, instrumental, flexible, and counterproductive. The results suggest that fluidity in genderroles between spouses is associated with the woman manager’s sense of success and satisfaction in hercareer compared with more conventional gender role construction. It seems that traditional genderroles between spouses can be one reason for women’s difficulties in attaining (top) managerialpositions in Finland.

Originality/value – The study contributes to the prior literature concerning the work-familyrelationship by extending research into an area so far overlooked: namely, the role of the spouse inrelation to the woman manager’s career. The study calls into question the straightforward andunequivocal view of the family – so typical in discussions about work-family issues – by showing themany different meanings that women managers attach to one of the family members.

Keywords Women, Managers, Careers, Spouses, Narratives, Finland

Paper type Research paper

IntroductionThe growing number of women in the workforce and in management hassimultaneously spurred wider scientific interest in the interface between work,family and personal life (Poelmans et al., 2008). This trend, coupled with a blurring ofgender roles, a shift in employee values, increasing shares of dual-earner couples andsingle parents (Greenhaus and Singh, 2004; Greenhaus and Powell, 2006), greaterfamily involvement by men, and heightened employer concern for employees’ qualityof life further stresses the importance of the work-family relationship (Eby et al., 2005).

This paper examines the work-family issue from the perspective of womenmanagers by focusing specifically on the role of the male spouse for her career. Thus,the topic is investigated in heterosexual family arrangements. Gender roles have

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/1754-2413.htm

GM24,8

596

Received 9 June 2009Revised 28 August 2009Accepted 28 August 2009

Gender in ManagementVol. 24 No. 8, 2009pp. 596-614q Emerald Group Publishing Limited1754-2413DOI 10.1108/17542410911004867

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

historically tended to endorse the woman’s role as a wife and the husband’s authorityover her (Crompton and Lyonette, 2006). Hence, the woman’s role and competence bothin her work and in the family domain easily come to be questioned. Married womenwith children are indeed known to advance more slowly in the managerial rankscompared to corresponding men (Tharenou, 2001).

Prior research suggests that female managers are often torn between theirmanagerial and family roles, which makes them feel guilty and stressed (Greenhausand Beutell, 1985; Ruderman et al., 2002). Gendered expectations regarding women’sfamily responsibilities and roles in Western societies and organizations contributeparticularly to tensions between work and family (Santos and Cabral-Cardoso, 2008).Rosenbaum and Cohen (1999) note, however, that there are some cases in the literaturewhich suggest that the stress of working mothers is not necessarily the result of toomany demands, but rather of their perception of the effects of outside employment ontheir role as mothers. More specifically, women who receive support from theirhusbands are less likely to feel that their role in the family sphere is threatened by thefact that they also have a career.

Further, many studies have observed that the career choices and careerdevelopment of managerial women is influenced by their family role (White, 1995;Gordon et al., 2002; O’Neil and Bilimoria, 2005; Lamsa and Hiillos, 2008). Despite asubstantial body of literature on the work-family intersection in organization research(Byron, 2005; Eby et al., 2005), the field can be criticized for its simple and unequivocalview of the family. Studies often ignore that besides there being different forms offamily, the family itself consists of different members: spouses, children, grandparents,etc. In this paper a family is understood as “two or more individuals occupyinginterdependent roles with the purpose of accomplishing shared goals” (Eby et al., 2005,p. 126). Research on work-family issues, both in general and explicitly in relation towomen managers, also tends to focus on a conflict perspective (Powell and Mainiero,1992; Hewlett, 2002; Blair-Loy, 2003; Byron, 2005) and downplay the favourable effectsof family on work and of work on family (Eby et al., 2005). Still, some studies haveproposed positive interdependencies between work and family – spillover, enrichmentand facilitation, for instance (Rothbard, 2001; Greenhaus and Powell, 2006).

This article attempts to contribute to the prior literature on the work-familydilemma by extending research to a largely overlooked area: namely the role of thespouse – in this study, the husband – in relation to a female manager’s career. Our aimhere is not to concentrate on either a negative or a positive perspective, but to gain aholistic picture of the topic. Of particular interest is the meaning of the spouse and therelation of gender role construction between spouses on the woman’s career. Our focusis on professional women who are pursuing managerial careers. These women arecareer-oriented and can be regarded as economically independent of the traditionalpatriarchal structures of income support of the marriage through their own worklifeactivity (see Gatrell, 2007). We study the topic in the Finnish context where, accordingto Crompton and Lyonette (2006), the dominant culture is what they refer to as “statemotherhood”: society’s strong support to women’s full employment.

Contrary to the quantitative approaches frequently used in previous studies onwork-family issues, we adopted a qualitative, more specifically a narrative approach inour study (Bruner, 1986, 1991; Polkinghorne, 1995). Since our aim was to provide a rich,holistic view and deeper understanding of the subject we decided to concentrate on the

The spouse ofthe female

manager

597

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

actual experiences of female managers. To this end we conducted an empirical researchinvestigating how they themselves tell about and make meaning of their spouses’ rolein their managerial career.

This article proceeds as follows. After discussing gender roles in Finland and therole of the spouse in prior research on the work-family relationship, we go on todescribe the narrative approach used in this study. We then present the typology ofspouses developed on the basis of our analysis of the spouse’s influence on thewoman’s career, describing the gender roles between spouses and the link betweengender role construction and the female manager’s career. The final sectionsummarizes the results, draws conclusions and discusses the study’s implications forfuture research.

Gender roles in FinlandA gender role is usually understood as the behavioral norms associated with males andfemales in a particular social context (Eagly, 1987). Gender roles also define thedivision of labor between women and men: for example, women are usually expected totake care of the children, while men are expected to work outside the home and be thebreadwinners of the family.

Among Western countries, Finland has the highest share of women in theworkforce. Finnish women typically work fulltime as opposed, for example, to TheNetherlands and the UK where the percentages of women in part-time employment arethe highest in Europe (Crompton and Lyonette, 2006). Like the other Nordic countries,Finland can be said to have relatively high gender equality in society, especially interms of legislation, politics and participation in work life (Hearn et al., 2003). Butdespite making up almost half of the Finnish workforce, women continue to represent aminority in the managerial population – and even more conspicuously in top-linemanagement. Although about 30 percent of Finnish managers are women (StatisticsFinland, 2007), only 7-8 percent are CEOs (Kotiranta et al., 2007). Moreover, one-third ofFinnish female managers are single, as compared to 10 percent of their malecounterparts. The spouses of managers of both genders are more likely to be upperwhite-collar employees and to participate in working live more often than the spousesof employees in general. Especially women managers aged 50-54 havemanagement-level husbands, while men managers’ wives are more frequentlylower-level white-collar employees. (Kartovaara, 2003.)

Hearn et al. (2003) argue that the fact that the Finnish labor market is segregatedboth vertically and horizontally has actually created two labor markets: one for womenand another for men. Recruiting for managerial positions, particularly for topmanagement, occurs mainly from a male pool in spite of Finnish women’s highereducational level compared to men’s. This, of course, makes it more difficult for womento attain (top) managerial positions. The consequent male domination in managementhas negative implications not only for gender equality but also for the competitiveadvantage of organizations (Kotiranta et al., 2007). Gender roles in management havethus come to be masculinized: management is seen to be primarily suited for men withspecific masculine characteristics (Lamsa and Tiensuu, 2002).

Apart from some outstanding examples of Finnish women in visible managerialpositions, often in family businesses (Kortelainen, 2007), women’s role has historicallybeen mainly restricted to the domestic sphere. The role of a mother and wife used to be

GM24,8

598

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

highly significant in the former agrarian society, where women had power over thehousehold. Yet, even at that time women were always subordinated to men and in allofficial contexts also represented by them – their husbands, fathers or brothers. Amarried woman was legally under the authority of her husband up until the year 1930and needed his permission, for example, to work outside the home (Tuomaala, 2008).

Gender roles changed as a result of industrialization, because women were neededin the workforce. The opening of educational and work opportunities to women formedthe basis for their public role in society (Korppi-Tommola, 2001). Still, Finnish womenhad worked as partners alongside the men for centuries in the agrarian culture, whichis why gender roles had never grown so drastically different in Finland as in manyother societies (Haavio-Mannila, 1970). With rise of industrialization the agrarianmodel was replaced by a middle-class idea of gender roles (Valtonen, 2004), with thewife seen as the provider of care in the domestic sphere and the husband as thebreadwinner acting in the public sphere. Gatrell (2006) claims that the norm of the idealfamily as a married heterosexual couple with two or three children began to spread inWestern Europe and North America particularly in the 1950s and 1960s. This idealalso became common in Finland, but the high share of women in the workforce and infulltime jobs is a distinctive feature of Finnish society compared to many otherWestern countries.

At the societal level, women’s participation in working life is facilitated by extensivechildcare support and maternity and child allowances, which enable Finnish women tocombine work and family responsibilities and permit them to have professional careers(Crompton and Lyonette, 2006). The purpose of these services and provisions is tocontribute to gender equality in business life. In practice, however, given that Finnishwomen have traditionally worked fulltime, they continue to carry a double-burden,taking care of both their outside job and their household.

On the other hand, the identity of the Finnish male and his value as a man havealways been defined through his work (Kortteinen, 1992), whereas today he is expectedto invest more into family life (Julkunen, 1992). Family support systems, for example,are now targeted to mothers and fathers alike, although it is still mainly women whotake advantage of these systems. Despite men’s increased participation in thehousehold, women nonetheless do nine hours more unpaid domestic work per weekthan men, and men work more hours in paid employment outside the home (Piekkolaand Ruuskanen, 2006). Thus, despite some changes and more fluidity in gender roles, itseems that that the traditional role division continues to be quite common in Finnishdomestic life, although women have moved from the family sphere towards workinglife and men vice versa. Men’s gender role in the future is predicted to be more of a careprovider in the family, and the work-family relationship is foreseen to grow moresimilar between genders (Varanka et al., 2006).

Work, family – and the role of the spouseThe interface between work and family has been extensively researched over the lastfew decades. Rothbard (2001) discerns two main approaches in this field of study:depletion and enrichment. Depletion, the dominating view, sees work and family astwo separate and conflicting domains that compete for people’s time and energy(Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985; Kossek and Ozeki, 1998; Byron, 2005). This argumentmaintains that people have a fixed amount of psychological and physiological

The spouse ofthe female

manager

599

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

resources and that tradeoffs are required to accommodate these resources. The conflictcomes from the fact that a female manager has limited resources to participate infamily life due to her career demands. The domestic workload, in turn, has a negativeeffect on her career. This makes it hard for her to live up to the multiple simultaneousrole expectations of a manager, a wife and a mother. The sociocultural context alsoplays a role in the level of the work-family conflict, as suggested by Santos andCabral-Cardoso (2008). Along this line of thought, a woman manager who gets spousalsupport may feel less conflict than one without such support. And correspondingly, ifthe gender roles between spouses are traditional – that is, if the woman is expected tobe primarily a mother and wife and the man is expected to be the breadwinner – thefemale manager can perceive a high level of conflict (Rosenbaum and Cohen, 1999).

The enrichment perspective, on the other hand, proposes that engagement in onerole can facilitate engagement in another role (Greenhaus and Powell, 2006; Greenhausand Foley, 2007). For example, the roles women play in their personal lives providethem with resources, like psychological benefits, emotional advice and support,enhanced multitasking, broadened personal interests, opportunities to enrichinterpersonal skills, and leadership practice – all relevant background factors in amanagement role (Ruderman et al., 2002). The enrichment claim draws on the notionthat a greater number of role commitments provides benefits to individuals: the wholeperson is more than the sum of the parts – or roles, in this case – and participation incertain roles generates resources to be used in other roles. From this point of view it isimportant to understand how a woman manager’s family life and work life aremeaningfully connected – and, more explicitly, what the role of the spouse is in thisconnection.

Some studies have specifically explored the spouse’s influence in women’s careers(e.g. White et al., 1997; Still and Timms, 1998; O’Neil and Bilimoria, 2005; Vanhala,2005; Lamsa and Hiillos, 2008). White et al. (1997) found that the spouse gives thefemale manager a secure background for building a career, although some women intheir study felt that the family had a negative effect on their managerial careers, forexample, by limiting their mobility or expecting them to follow the husbands’ careerpaths. Still and Timms (1998) reported that the choices, experiences and concerns oftheir husbands influenced the conditions under which women – especially the oldercareer age group of women managers and professionals in their study – assessed theirown careers and aspirations were influenced by. Similarly, O’Neil and Bilimoria (2005)argued that the spouse can have a significant impact on women’s career decisions andchoices. Vanhala (2005), for her part, observed that the spouse’s support in domesticwork can be very important for a female manager. Lamsa and Hiillos (2008), on theother hand, discovered that women managers could perceive their spouses’ role both innegative and positive terms. In some cases the spouse had not been able to cope withthe woman’s professional success, whereas in others he had played a very supportingrole.

Ezzedeen and Ritchey (2008) proposed a typology of spousal support to womenmanagers in an American context. Their typology captures five support behaviors byexecutive women’s spouses: emotional support, help with the household, help withfamily members, career and esteem support, and the husband’s career and lifestylechoices. Emotional support behavior is defined as encouraging, understanding andlistening. Help with the household refers to activities like cleaning, cooking, taking care

GM24,8

600

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

of bills and a willingness to spend money on help. Help with family members consistsof caring for children and aging family members and attending to pets. Career supportimplies emotional and instrumental support in the woman’s career aspirations – forinstance, offering technical assistance and professional advice. Esteem support, on theother hand, emerges as a sense of pride, appreciation and belief in her work. The lastcategory of spousal support refers to the husband’s career and lifestyle choices thatsupport the wife’s high-profile job. While their study is one of the few that represent thespouse’s role with respect to a woman’s work, it still does not focus explicitly on hercareer. And moreover, it was conducted in the USA, where gender roles are quitedifferent from those in Finland.

The empirical data and data analysisPrior research on the work-family relationship has generally followed a quantitativeapproach. Eby et al. (2005) suggested that the limited number of exploratory studies onthe issue may, in fact, have restricted the development of theory building. Sinceexploratory research helps to gain a general understanding of a phenomenon, it is afruitful alternative when the subject of study is not well known. Thus, in order toadequately understand the role of the spouse for a woman manager’s career, we chose anarrative approach in gathering the data. Drawing on an idea from Soderberg (2003)we understand a narrative as an account of events occurring over time, thusemphasizing that any narrative has a chronological dimension. Additionally, we see anarrative as a retrospective interpretation of sequential events from a certain point ofview. In other words, when a women manager tells of events related to her spouse, sheintegrates them retrospectively to her career to make them understandable from herown point of view. The adopted approach provides a fertile alternative as a form ofdata, as it concentrates on how women themselves make meaning of their experiencesand thereby allows for a richer understanding of the topic. An analysis of the narrationof the investigated women managers reveals how they construct the meanings theyattach to their spouses in relation to their career.

To attain a broad and rich view of the topic we sought to obtain a heterogeneousgroup of women for the study. Purposeful sampling (Patton, 2002) was used forselecting women in their mid and late career who had sufficient work and lifeexperience to reflect on the topic retrospectively. Thus, a common feature shared by theinterviewees was their managerial position and extensive work experience. Moreover,all of the women either had or had had one or more spouses in the course of theircareers, and all but one were mothers, mostly of teen-age or adult children. Weconducted 25 interviews and collected four written narratives from these femalemanagers. The sample included 29 Finnish women between the ages of 35 and 63. Themean age was 44 years; however, one of the participants did not disclose her age. Thewomen worked in small, medium and large organizations in the public and privatesectors; one-third of them were owners of the business. All had a long general workhistory between nine and 38 years and had held managerial positions between two and35 years. Their educational background varied from secondary-level to higheracademic degrees.

The interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed word-for-word. Each womanwas assigned a code number from 1 to 29, which is used later on in this article to refer aparticular manager. We analysed the women’s narratives following the idea of

The spouse ofthe female

manager

601

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

paradigmatic cognition by Polkinghorne (1995), see also Bruner, 1986). According tothis idea, the narrative data are interpreted by categorizing, producing taxonomies andtypologies, and looking for similarities and differences. To this end, data analysis wasorganized into six phases using Nnivo computer software.

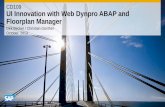

In the first phase we read the data multiple times to become properly familiar withthe study material. In the second phase the data were organized into three maincategories depending on the meanings given to the spouse: positive, negative andother. In this phase we first divided the narrative phrases into those containing positiveand negative meanings, based on White et al. (1997) and Lamsa and Hiillos (2008), whohave argued for this dichotomy. However, not all of the phrases fit these two groups, sowe added the category of other meanings. In the third phase the contents of each of thethree categories were scrutinized for differences and similarities within them. In thefourth phase we conducted an even more thorough and detailed investigation, leadingto the formation of the main meaning groups and a preliminary typology of spouses.At this stage the following types were identified: a determining, supporting,instrumental, flexible and negative spouse. Then, in the fifth phase we re-examinedand remodeled the third and fourth phases, and further clarified the typology. Andlastly, after many reformulations and discussions between ourselves we formed thefinal typology of spouses on the basis of the analysis, including a determining,supporting, instrumental, flexible and counterproductive spouse. Table I shows thefrequency of each type in the data.

Next, our discussion turns to a description of the identified types of spouses.Quotations from the data are presented to capture the essence of each type, but due tothe limited space of this article, only one direct citation per type is included.

Types of spousesThe determining spouse

But I’ve had, like, a rather interesting [situation], if you think about my career, you might saythat perhaps from my point of view it hasn’t been such a good solution, this, that Jarkko[husband] and I, we made the decision, we had one-year-old Janne [son], that we’d go off onthis assignment to location X [. . .] And my husband was terribly eager[to go]because he waspretty much in a deadlock about what to do and so on [. . .]Yes, he was terribly eager [. . .] (17).

In this category the spouse is constructed as having a determining influence on thewoman’s career. His work situation sets the boundaries for and implicitly directs andtakes priority over the woman’s career choices. In other words, she adjusts her careerpath to that of the husband’s. The woman manager tells how her spouse’s employmentsituation, his job and career, had a crucial impact in guiding her career decisions andmoves. In certain aspects this is in line with a finding by White et al. (1997), whoreported that some of the women managers in their study felt their career wasnegatively affected by family life due to their reduced mobility or the need to follow thehusband’s career. The narrations in our study reveal that the spouse had beenespecially influential in two main respects: first, regarding the woman’s studyorientation and motivation prior to her working career, and second, regarding hercareer breaks and moves both in the early and in later stages of her professionalhistory. However, largely in contrast to the result by White et al., the women in ourresearch did not make many negative remarks about this kind of spousal influence on

GM24,8

602

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

their careers. And moreover, White et al. did not examine the spouse’s role indetermining the woman’s future career during her student phase.

In the narrations in this study, the determining spouse is claimed to have had aneffect on the woman’s choice of place and field of study as well as her motivation tostudy. The woman had based her choice on the spouse’s location and was willing tomove to study wherever he was. Some women had even changed their field of studydepending on the available alternatives in the spouse’s location. One of the managers(21) said she would not have applied to university at all had it not been for her spouse.Narration in this category is generally positive in tone, although there are somenegative mentions as well. For example, one manager (8) regretted not having beenable to devote herself enough to her studies due to her spouse’s career move, becauseshe really felt it would have paid off later on in her career.

Women managers also described both shorter and longer breaks and moves in theircareers due to the spouse’s career mobility. There are several examples in the data of

Womanmanager

Determiningspouse

Supportingspouse

Instrumentalspouse

Flexiblespouse

Counterproductivespouse

No. 1 £ £ £No. 2 £ £ £No .3 £ £No. 4 £No. 5 £ £No. 6 £ £No. 7 £ £No. 8 £ £ £ £No. 9 £ £ £No. 10 £ £ £No. 11 £ £No. 12 £ £No. 13 £ £ £No. 14 £ £No. 15 £ £ £ £No. 16 £ £ £ £No. 17 £ £ £No. 18 £ £ £No. 19 £ £No. 20 £ £No. 21 £ £ £No. 22 £ £ £No. 23 £ £ £No. 24 £ £No. 25 £ £No. 26 £ £ £No. 27 £ £ £No. 28 £ £ £ £No. 29 £ £ £Total 15 27 5 12 19Coded phrasestotal 63 107 5 32 45

Table I.Distribution of spouse

types in the womenmanagers’ narratives

The spouse ofthe female

manager

603

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

the woman leaving a good job with career opportunities because the spouse’s newwork required moving to a new location. Some women had turned down a new job forfamily reasons if it meant moving to another place. For example, two women (8 and 27)had left their jobs to follow the husband, and had spent several years as housewivestaking care of the family during his assignment abroad. The nature of the spouse’swork appeared to be another reason for career breaks. If the spouse was in a verydemanding stage in his career or had to do a lot of traveling, the woman could interrupther own career to stay at home and look after the household and the children. Womentypically explained that their choices had been made from the viewpoint of the spouseand the whole family, saying they were mainly satisfied with their decisions. Besidesenabling these women to devote themselves to the family, staying at home also gavethem special skills – organizational skills, for example – that would prove useful laterin their careers.

Traditional gender roles seem to dominate in the category of a determining spouse:the woman’s career is put aside to give priority to the husband’s work and career. Thewoman’s primary task is to take care of the family and guarantee its welfare. Hergender role between spouses is first, as a wife and mother and only second, as aworking woman pursuing her career. The husband, for his part, is constructed as themain breadwinner of the family. Moreover, this gender role construction is hardlyquestioned in the narrations, but rather accepted as a normal situation. In the few caseswhere such gender roles were questioned, narration turned into a negative direction.

The supporting spouse

He has always encouraged [me] when I’ve been pondering about, like, well, and he has. . . andI remember when the CEO question was at hand, he told me to go and phone them and say“sure, I’ll take it right away”. [He said] that I didn’t need to consider, that of course I’d take itnow, for god’s sake I shouldn’t miss an opportunity like this [. . .] I’d say, well, he has been mybest supporter. He’s been like a sparring partner, he’s been the one, well, who has taken careof the home [. . .] And, like, he’s really supported me 110 percent [. . .] I’m just thinking that,well, and I’ve told him many times, “listen, without you I wouldn’t be here” (28).

The supporting spouse is described as a husband who helps and encourages thewoman in her career as well as discusses her work issues and challenges with her,backing her at various stages of her career and in difficult work situations. This type ofspouse is presented as providing active support instead of trying to overrun thewoman’s career. The relationship between spouses is defined as equal: they cherishand respect one another. The spouse is spoken about in positive terms and his supporthighly valued. A similar valuation of spousal support by executive women has alsobeen reported by Ezzedeen and Ritchey (2008).

In this study, spousal support could be roughly divided into two kinds of support:psychosocial, both explicit and tacit, and practical. The narratives suggest that whenthe spouse’s psychosocial support is explicit it involves discussions andencouragement and creating confidence and self-esteem in the woman. Tacitpsychosocial support refers to background support: the husband is seen as a securefoundation for building the woman’s career. One of the managers (4) said her husbandgave great help and support in the background, but she did not feel that he wasactively trying to influence her career. Another woman (6) remarked that her husband

GM24,8

604

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

had always spoken positively about her work to others and provided support in thatway.

Women managers described practical support by the spouse as highly relevant inachieving a work-family balance. His help diminished the domestic workload, makingit easier for the woman to advance in her career. This practical support might meantaking care of the children and the household, cleaning and cooking. Some women gaveexamples of their spouses’ concrete acts in helping them to progress their careers, suchas assisting in making job applications or organizing office facilities and equipment.For example, one manager (16) told how her husband had helped her to graduate fromuniversity by arranging a typewriter and Dictaphone for her. Another woman’s (27)husband had provided business premises for her so she was able to start a businesswithout significant effort or risk.

In this category, the spouses’ gender roles seems to be in balance: the womanmanager felt she could combine work and family, thanks to her husband’s variousforms of support. The relationship between spouses is constructed as egalitarian:although both spouses were working outside the home they both also took part incaring for the family and housework with neither partner dominating. Such supportmade the woman feel that her domestic role as a wife and mother was not threatenedby her professional role as a manager. From a career perspective, this type of balancedrelationship between spouses was presented as very important for the woman’spossibilities to invest in her career.

The instrumental spouse

You know, I’ve always had my rear securely covered and always had very successful menbehind me. So if things had gone bad for me I wouldn’t ever have been terribly hard hit, thosemen could have provided for me then. And this, I think [is the case] with women in general[. . .] You might say, and this has probably often been the case with women of my generation,that it’s been quite moral, without [fear of] losing the community’s respect, to fail and to be ahousewife, for instance (27).

This type of spouse is constructed as valuable in his ability to offer advantage andadded value to the woman’s career. In other words, he is seen to have instrumentalvalue with respect to the woman’s career.

In the narrations the instrumental spouse was appreciated especially because hecontributed to a certain social image and provided financial security and a comfortableliving environment. One female manager (19) felt that she had needed marriage and ahusband to create an appropriate social image and status to be taken seriously both asa business manager and a woman in the early phase of her career. Because she wasliving in a small locality, the community norm seemed to demand that she as a youngwoman working in a visible position should not be single but preferably a wife, and soshe decided to marry a suitable candidate. Another manager (16) mentioned that herhusband’s profession was very highly valued in the masculine business environmentshe herself worked in, and that her male superior always asked her to give his bestwishes to her husband. In fact she believed she was more appreciated in her workbecause of her husband. Still another woman (27) said her husband had given her asense of financial security. Had she failed in her business, he would have been able toprovide for her and the family. This had made it easy for her to be a business ownersince there was no fear of financial risk. The instrumental spouse was appreciated for

The spouse ofthe female

manager

605

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

his ability to ensure the desired kind of lifestyle for the woman, giving her a chance toinvest in her career. One of the women managers (28) described her husband’ssignificant role in creating a happy life for her by providing her a good livingenvironment in the countryside and thereby creating the conditions for success in hercareer.

In this category the husband’s gender role is constructed as a partner who can beutilized by the woman to achieve goals that are important to her. The spouse isregarded as a career resource for the female manager; in this sense she appears to enjoya socially dominant position over him, in contrast to the traditional gender roles wherethe woman is more commonly objectified. Yet the advantages that the husband wasexplained to provide were not related to the household or the family – women’straditional domains – but rather to general material and social benefits concerning thepublic sphere of life – men’s traditional domain. Consequently, the narrations definedthe spouse’s gender role with an emphasis on his traditional male role. In other words,although his gender role construction between spouses was untraditional, yet the wayhe was described to act in that role remains traditionally male. In general, theinstrumental spouse was seen to have a positive influence on the woman’s career.

The flexible spouse

It, to a certain extent it’s, it’s not so long ago we were just talking about this in the sauna orsomewhere. . . And in a way, when he reached the last straw, reached a certain stage there,then he said he had made a very conscious choice. That when he met me and then we gotmarried and Aapo [son] was born, [he said] that we’re so important to him that he’d rathertake it easier in his work. And that this, to him, is the big thing (29).

The flexible spouse is presented in the narratives as one who was willing to put thewoman’s career before his own: the spouse was ready to adapt to the demands of herjob as a manager. Moreover, he was willing to sacrifice his career development for thesake of hers. Here the husband is the one mainly in charge of domestic duties, liketaking care of the household and the family, to allow the woman to fully invest in hercareer. Thus, his flexibility enables her engrossment in her work. According to thenarrations, this kind of choice was made either by joint agreement between spouses orby the husband on his own, but there was no mention of the husband having followedthis traditionally female gender role for such reasons as a low salary or low workstatus. Four of the spouses had spent longer periods of time taking care of theirchildren at home. One manager (28) remarked that she and her spouse had made aconscious, mutual decision that she would create a career outside the home and hewould work from the home. Another woman (11) said her spouse had always been veryadjusting to her career demands.

The narratives reveal that the flexible spouse assumed responsibility for the homeand the children. His flexibility is described as particularly important in criticalsituations – for example, when the woman took on a new position, had to travel a lot,worked long hours or faced a demanding phase in her career. The women alsomentioned that in case of an urgent need both spouses were willing to adjust. One ofthem (13) said she and her husband had been flexible by turns whenever either onefaced major work challenges or was in a demanding career stage. For example, whenshe had taken a job in another city, her husband had been ready to reduce his business

GM24,8

606

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

travels and had set up an office in their hometown so that the children would alwayshave at least one parent near them.

It seems that the traditional gender roles between spouses had turned upside downin this category: the wife is constructed as having a challenging career in the publicsphere and being the main breadwinner in the family, while the husband is seen as themain care provider in the domestic sphere. Interestingly, the husband’s choice isdescribed to have been his own conscious and voluntary choice or a result of a mutualagreement between spouses. The narratives picture him as an active partner in thedecision instead of presenting this kind of choice as self-evident for a man.

Despite claims that traditional gender roles are blurring – in Finland (Varanka et al.,2006) as elsewhere in the Western countries (Greenhaus and Singh, 2004) – the womenin our study also pointed out that flexible husbands continued to face stereotyping andnegative attitudes from outsiders, especially if the husband had stayed at home to takecare of the children and the household. For example, the spouse of one of the managers(26) had experienced a lot of negativity and his decision to become a househusband hadfrequently been questioned. Making an unconventional choice from the viewpoint oftraditional female and male gender roles was described as not an easy decision for thehusband. Despite negative attitudes and stereotyping, the narrations have a positivetone: the spouse’s flexibility was seen to contribute to the woman’s career. Women notonly valued the husband’s choice to help them in their careers, but also appreciated themen’s courage in breaking the conventional social norm regarding gender roles. Thespouse was articulated as a brave norm-breaker, almost a hero in this sense.

The counterproductive spouse

Even our divorce was probably due to the fact that my husband didn’t really approve of mystudying or really of my career development either. Probably at the stage when I got mydegree and went to work as a manager. That began to create friction, as if I’d switched sides,like, to the employer’s side. It was this kind of interesting background thinking, that we’dbeen on the same side earlier when I’d, like, been an employee, but then I started to move there[to the other side] and that created some kind of friction [. . .] (15).

The counterproductive spouse is constructed as having a negative and dismissiveattitude to the woman’s career. He is described as being narrow-minded and havingdifficulties to accept the woman’s higher status and income and her career success. Thenarrations see the husband as uncertain about his own position between spouses andassume him to feel inferior to his wife. Furthermore, he has to face outside pressuresand stereotypes for failing to prove himself the main breadwinner in the family.

The narratives of two managers (9 and 24) describe the husbands’ sense ofinferiority to their wives: they were uncomfortable with the women’s career success.Another manager (5) noted that her husband did not support her at all, but insteadtried to argue against her taking part in any postgraduate training that might benefither career. This female manager felt that her husband’s behavior was very childish; hewould only give assistance in the domestic sphere if it was absolutely necessary, whichmeant hardly at all. There were some other examples where the spouses wereunderstood as one another’s rivals with respect to their working-life status. Forexample, one manager (17) said that while her spouse had occasionally been supportiveand encouraging, she also sensed that he did not appreciate her work because he didnot want her to be superior to him.

The spouse ofthe female

manager

607

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

Time-based conflicts had also occurred between spouses in defining the meaning ofa ‘normal’ working day. Especially when the husband worked at the employee level, hewas described as not being always able to identify with the wife’s work, particularlyher working hours, since for him a normal working day was eight hours: from 8 a.m. to4 p.m. In other words, it was difficult for the spouse to understand and accept the longand varying hours often necessary in a managerial position. This caused conflicts andwas restrictive from the woman’s career perspective. Two of the managers (12 and 15)noted that the fact that their husbands found it hard to accept their long working hoursnot only hindered their careers but also caused problems in the relationship betweenspouses. The two women described this as one of the reasons that eventually led themto divorce.

This category reflects the historical division of gender roles – women having beenrepresented in the public domain by their husbands or male relatives because theywere seen as incapable of representing themselves (Tuomaala, 2008): thecounterproductive spouse is described to support the idea of the woman’ssubordination to the man. Women’s refusal to follow and accept such constructionof gender roles, and their desire to be their own representatives and take an active partin the public sphere, was reported to raise conflicts and problems in the spousalrelationship. Thus, the tone of narration in this category is negative, with the spousegenerally described as restrictive and unsupportive from the woman’s careerviewpoint.

Summary and conclusionThis exploratory study has focused on the influence of the spouse on the femalemanager’s career. Particular attention was paid to the gender roles between themanager and her husband, and to the gender role construction between spouses inrelation to the woman’s career. We studied the narratives of 29 Finnish womenmanagers concerning the topic and developed a typology of spouses based on thewomen’s narration. This typology is summarized in Table II.

Our results support the argument presented in prior research about the importanceof the family in a woman manager’s career choices and career development (White,1995; Gordon et al., 2002; O’Neil and Bilimoria, 2005; Lamsa and Hiillos, 2008).However, our findings call into question the straightforward and unequivocal view ofthe family – so typical in discussions about work-family issues (see Eby et al., 2005) –by revealing the many different meanings that women managers attach to one of thefamily members: in this study, the husband. The results offer evidence that the spousehas a significant effect on a female manager’s career, although this particular aspecthas been largely overlooked in previous studies. Our article provides an overview ofthis somewhat unexplored topic, but we do feel that it merits further research in thefuture. In our view, it is relevant to understand the varying and multiple nature of thedynamics involved in the work-family dilemma in organizational life – not only fromthe viewpoint of managerial and employee wellbeing and stress management, which isa fairly common perspective in research, but also from the standpoint of careermanagement.

The developed typology illustrates that the dichotomy proposed by White et al.(1997) and Lamsa and Hiillos (2008), where the spouse’s role is seen as either positive ornegative for a woman manager’s career, gives a far too narrow and simplistic picture.

GM24,8

608

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

Our findings show that the spouse’s meaning for the woman’s career can beconstructed in many diverse ways. We identified five types of spouses in this study –determining, supporting, flexible, instrumental and counterproductive – but otherroles may be found as well. While the meanings given to the spouse in our study weregenerally positive in tone and the most common type in the narratives was, in fact, thesupporting spouse, still the counterproductive spouse was mentioned second mostfrequently. Indeed, women managers had often been obligated to justify their choice ofa managerial career – a domain that has traditionally viewed as male. This impliesthat even in Finland, the context of this study, which enjoys high gender equality inwork life participation (Hearn et al. 2003), a woman’s managerial career still often needsto be discussed and reasoned as a “special” case.

The determining spouse emerged as the third most common type in the narrations.Women described his influence as self-evident in their careers, seldom in negativeterms. This finding can be explained, for instance, by referring to an idea presented

Type of spouseDescription of keycharacteristics

Influence on womanmanager’s career

Link between spousalgender roles and womanmanager’s career

Determiningspouse

Spouse’s job preferenceslargely determinewoman’s career choicesand orientation

Woman’s studies, careerbreaks and orientationare based on spouse’scareer changes and careermoves

Woman’s career issubordinated to spouse’sdecisions: man’s genderrole is dominant betweenspouses

Supporting spouse Spouse activelyencourages and supportswoman in her career

Spouse’s psychosocialand practical supportenables and helpswoman’s careeradvancement

Woman makes her owncareer decisions but afterdiscussing with spouse;relationship betweenspouses is open,respectful and balanced

Instrumentalspouse

Women utilizes herspouse as an instrumentbeneficial for her career

Spouse creates socialstatus, ensuring financialsecurity and comfortableliving environment

Woman is grateful forbenefits to her careerreceived from spouse;woman is more dominantbetween spouses

Flexible spouse Spouse is flexible andwillingly adapts towoman’s career demands

Spouse takesresponsibility for homeand children; he adjustshis own work and careerin favour of woman’scareer advancement

Spouse’s action issubordinated to woman’scareer decisions; womanis more dominantbetween spouses; spousemay face externalstereotyping and negativeattitudes

Counterproductivespouse

Spouse hasunconstructive attitude towoman’s career and isreluctant to approve of orunderstand it

Spouse is unsupportiveand negative, which hasrestrictive effects onwoman’s career

Spouse prefers traditionalgender roles wherewoman is subordinate toman; his insecurity overhis own position isproblematic for woman’scareer

Table II.Summary: types of

spouses constructed bythe women managers

The spouse ofthe female

manager

609

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

already by Simone De Beauvoir (1999) in her book The Second Sex. She asserted thateven though women are as capable of choice as men, they tend to adopt a “passive” roleto the man’s “active” and subjective demands, which then leads to an unequalrelationship between them. On the other hand, there were some instances in our studywhere women had regrets or doubts about yielding to their husbands’ choices. Theyfelt dissatisfied at having accepted the traditional female gender role because it hadhad a negative influence on their careers.

The flexible spouse was fourth most common in the narrations. He was presented ashaving a clearly positive effect on a female manager’s career. The frequency of thistype suggests that traditional gender roles have changed into a more fluid direction inFinland (Varanka et al., 2006). The change may not be so marked, however, since thistype of spouse still had to face external pressures and stereotyping in a gender role thatwas recognized as typically suitable for women. In the narratives the least commonwas the instrumental spouse, although women had attached a variety of constructedmeanings to this type. From the perspective of gender roles between spouses, here thewoman emerged as the more dominant spouse. Interestingly the gender roles in boththe flexible and instrumental categories were untraditional and reversed; the malegender was constructed into a characteristically female role. On the other hand, bothtypes exhibited traditionally masculine behaviors: providing material security, in thecase of the instrumental spouse, and activity in decision making, even heroic breakingof social norms in the case of the flexible spouse. It implies that despite some changesin gender roles, a man cannot (yet) be entirely placed into a woman’s traditional genderrole. Both the flexible and the instrumental spouse were considered positive for thewoman’s career.

The findings presented above must be interpreted bearing in mind the limitations ofthe study. First, this study only captures the view of heterosexual couples and ignoresother types of family forms. We suggest that in the future it would also be important tostudy same-sex couples, which, in general, are an undiscovered topic in research on thework-life relationship and managerial careers. Second, although our findings arelimited to the Finnish context, they are intended to stimulate further research interestnot only in Finland but in other countries as well. Considering the existing societaldifferences in terms of the work-family relationship (see e.g. Rosenbaum and Cohen,1999; Crompton and Lyonette, 2006; Santos and Cabral-Cardoso, 2008), anygeneralization to other societal contexts should be made with caution. This is onereason why it might be advantageous for future research to explore the subject indifferent societies. Thirdly, since the sample in this study is rather heterogeneous dueto the exploratory nature of the study, it might be valuable to narrow it down inforthcoming studies to specific groups – top managers and board members, forexample.

While previous research has examined the spouse’s role from the explicit viewpointof a female managerial career (e.g. White et al., 1997; Still and Timms, 1998; O’Neil andBilimoria, 2005; Vanhala, 2005; Lamsa and Hiillos, 2008), the present study is the firstto seek a more holistic picture of the topic through empirical research. Prior studies onwork-family issues and women managers have inclined towards a conflict perspective(Powell and Mainiero, 1992; Hewlett, 2002; Blair-Loy, 2003; Byron, 2005). This studyshows that the relationship is much more varied. Our results indicate that more fluidityin gender roles between spouses can be associated with female managers’ sense of

GM24,8

610

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

success and satisfaction in their careers compared to more conventional gender roleconstruction. In any case, we suggest that spousal support to a woman’s career inmanagement is an area that surely requires more empirical research in the future.

It has also been proposed that a woman’s career and work life cannot be examinedwithout examining her non-work life as well (Powell and Mainiero, 1992). Our studyspecifically captures the link between her work life – her professional career – and hernon-work life – her spouse. We suggest that future research should pay addedattention to the role of the spouse: it would be especially beneficial to examine how thespousal role changes in the course of a woman’s career. Moreover, it would beworthwhile to explore the narrations of male managers to obtain a reciprocalperspective.

In practice, the results of this study indicate that having a husband with a flexibleand broad-minded view of gender roles and sharing common interests between thespouses may enable women better to manage their careers and integrate their workand family lives successfully. On the other hand, difficulties in marital relationshipsoften might reflect unfavorably on their careers and on the work-family balance.Women might benefit from both formal and informal mentoring relationships, whichcan provide not only direct support – such as networks for personal careerdevelopment – but also psycho-social support, role-modeling and advice in managingthe work-family relationship (Kram, 1985). From an organizational point of view, thedesign of formal mentoring programs might be particularly valuable for women, sincethey have been found to perceive more barriers to establishing informal mentoringrelationships than men (Ragins and Cotton, 1991, 1999). It further seems that differentkinds of supportive strategies to combine managerial career and family life are neededat the organizational level. Since the spouse’s role for the woman’s career can bevarious, such strategies should also consider people’s individual and varying lifesituations. In general, it would be fruitful to create an atmosphere and culture in theorganization that respects the personal and family concerns of its members andpromotes a flexible and broad-minded view of gender roles in organizationalresponsibilities.

To conclude, despite the fact that female and male gender roles in Finland are morefluid compared to many other Western countries (Crompton and Lyonette, 2006), thisstudy provides some evidence that traditional gender roles continue to have an effectfor women’s difficulties to attain (top) managerial positions in Finland. Such traditionalgender role construction might be considered prohibitive for women’s careers inmanagement even today. Our study implies that traditional gender role constructionstill makes the option of staying at home or choosing a less demanding career not (yet)an easy one for the male spouse of a female manager – even in fairly egalitarianFinland.

References

Blair-Loy, M. (2003), Competing Devotions, Career and Family among Women Executives,Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Bruner, J. (1986), Actual Minds, Possible Worlds, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Bruner, J. (1991), “The narrative construction of reality”, Critical Inquiry, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 1-21.

Byron, K. (2005), “A meta-analytic review of work-family conflict and its antecedents”, Journal ofVocational Behavior, Vol. 67 No. 2, pp. 169-98.

The spouse ofthe female

manager

611

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

Crompton, R. and Lyonette, C. (2006), “Work-life ‘balance’ in Europe”, Acta Sociologica, Vol. 49No. 4, pp. 379-93.

De Beauvoir, S. (1999), Toinen sukupuoli, Kustannusosakeyhtio Tammi, Helsinki (translated bySuni, A.) (originally published in 1949).

Eagly, A.H. (1987), Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-role Interpretation, LawrenceErlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ.

Eby, L.T., Casper, W.J., Lockwood, A., Bordeaux, C. and Brinley, A. (2005), “Work and familyresearch in IO/OB: content analysis and review of the literature (1980-2002)”, Journal ofVocational Behavior, Vol. 66 No. 1, pp. 124-97.

Ezzedeen, S.R. and Ritchey, K.R. (2008), “The man behind the woman: a qualitative study of thespousal support received and valued by executive women”, Journal of Family Issues,Vol. 29 No. 9, pp. 1107-35.

Gatrell, C.J. (2006), “Managing maternity”, in McTavish, D. and Miller, K. (Eds), Women inLeadership and Management, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp. 89-108.

Gatrell, C. (2007), “Whose child is it anyway? The negotiation of paternal entitlements withinmarriage”, The Sociological Review, Vol. 55 No. 2, pp. 352-71.

Gordon, J.R., Beatty, J.E. and Whelan-Berry, K.S. (2002), “The midlife transition of professionalwomen with children”, Women in Management Review, Vol. 17 No. 7, pp. 328-41.

Greenhaus, J.H. and Beutell, N.J. (1985), “Sources of conflict between work and family roles”,Academy of Management Review, Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 76-88.

Greenhaus, J.H. and Foley, S. (2007), “The intersection of work and family lives”, in Gunz, H. andPeiperl, M. (Eds), Handbook of Career Studies, Sage, Los Angeles, CA, pp. 131-52.

Greenhaus, J.H. and Powell, G.N. (2006), “When work and family are allies: a theory ofwork-family enrichment”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 31 No. 1, pp. 72-92.

Greenhaus, J.H. and Singh, R. (2004), “Family-work relationships”, in Spielberger, C.D. (Ed.),Encylopedia of Applied Psychology, Elsevier, San Diego, CA, pp. 687-98.

Haavio-Mannila, E. (1970), Suomalainen nainen ja mies, WSOY, Porvoo.

Hearn, J., Kovalainen, A. and Tallberg, T. (2003), “Organising knowledge, gender divisions andgender policies: the case of large Finnish corporations”, International Journal of Internetand Enterprise Management, Vol. 1 No. 4, pp. 404-20.

Hewlett, S.A. (2002), “Executive women and the myth of having it all”, Harvard Business Review,Vol. 80 No. 4, pp. 66-73.

Julkunen, R. (1992), Hyvinvointivaltio kaannekohdassa, Vastapaino, Tampere.

Kartovaara, L. (2003), “Miesjohtajalla ura ja perhe, enta naisjohtajalla?”, Hyvinvointikatsaus,No. 4, pp. 2-8.

Korppi-Tommola, A. (2001), Tahdolla ja tunteella tasa-arvoa: Naisjarjestojen Keskusliitto1911-2001, Gummerus, Jyvaskyla.

Kortelainen, A. (2007), Varhaiset johtotahdet – Suomen ensimmaisia johtajanaisia, EVA Raport,Taloustieto Oy, Yliopistopaino.

Kortteinen, M. (1992), Kunnian kentta: Suomalainen palkkatyo kulttuurisena muotona, KaristoOy, Hameenlinna.

Kossek, E.E. and Ozeki, C. (1998), “Work-family conflict, policies, and the job-life satisfactionrelationship: a review and directions for organizational behavior-human resourcesresearch”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 83 No. 2, pp. 139-49.

Kotiranta, A., Kovalainen, A. and Rouvinen, P. (2007), Naisten johtamat yritykset jakannattavuus, EVA Analysis No. 3, EVA, Helsinki.

GM24,8

612

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

Kram, K.E. (1985), Mentoring at Work: Developmental Relationships in Organizational Life,Scott Foresman, Glenview, IL.

Lamsa, A.-M. and Hiillos, M. (2008), “Career counselling for women managers: developing anautobiographical approach”, Gender in Management: An International Journal, Vol. 23No. 6, pp. 395-408.

Lamsa, A.-M. and Tiensuu, T. (2002), “Representations of the woman leader in Finnish businessmedia articles”, Business Ethics: A European Review, Vol. 11 No. 4, pp. 355-66.

O’Neil, D.A. and Bilimoria, D. (2005), “Women’s career development phases”, CareerDevelopment International, Vol. 10 No. 3, pp. 168-89.

Patton, M.Q. (2002), Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed., Sage, Thousand Oaks,CA.

Piekkola, H. and Ruuskanen, O.-P. (2006), Work and Time Use across Life Cycle – Mothers andAgeing Workers, Reports of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health Finland 2006:73,Ministry of Social Affairs and Health Finland, Helsinki.

Poelmans, S., Stepanova, O. and Masuda, A. (2008), “Positive spillover between personal andprofessional life: definitions, antecedents, consequences, and strategies”, in Korabik, K.,Lero, D.S. and Whitehead, D.L. (Eds), Handbook of Work-Family Integration, AcademicPress, London, pp. 141-56.

Polkinghorne, D.E. (1995), “Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis”, in Hatch, A.J. andWisniewski, R. (Eds), Life History and Narrative, Falmer Press, London, pp. 5-23.

Powell, G.N. and Mainiero, L.A. (1992), “Cross-currents in the river of the time: conceptualizingthe complexities of women’s careers”, Journal of Management, Vol. 18 No. 2, pp. 215-37.

Ragins, B.R. and Cotton, J.L. (1991), “Easier said than done: gender differences in perceivedbarriers to gaining a mentor”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 34 No. 4, pp. 939-51.

Ragins, B.R. and Cotton, J.L. (1999), “Mentor functions and outcomes: a comparison of men andwomen in formal and informal mentoring relationship”, Journal of Applied Psychology,Vol. 84 No. 4, pp. 529-50.

Rosenbaum, M. and Cohen, E. (1999), “Equalitarian marriages, spousal support, resourcefulness,and psychological distress among Israeli working women”, Journal of VocationalBehavior, Vol. 54 No. 1, pp. 102-13.

Rothbard, N.P. (2001), “Enriching or depleting? The dynamics of engagement in work and familyroles”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 46 No. 4, pp. 655-84.

Ruderman, M.N., Ohlott, P.J., Panzer, K. and King, S. (2002), “Benefits of multiple roles formanagerial women”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 45 No. 2, pp. 369-86.

Santos, G.G. and Cabral-Cardoso, C. (2008), “Work-family culture in academia: gendered view ofwork-family conflict and coping strategies”, Gender in Management: An InternationalJournal, Vol. 23 No. 6, pp. 442-57.

Soderberg, A-M. (2003), “Sensegiving and sensemaking in an integration process: a narrativeapproach to the study of an international acquisition”, in Czarniawska, B. and Gagliardi, P.(Eds), Narratives We Organize by, John Benjamins Publishing, Philadelphia, PA, pp. 3-35.

Statistics Finland (2007), Women and Men in Finland, Statistics Finland, Helsinki.

Still, L. and Timms, W. (1998), “Career barriers and the older woman manager”, Women inManagement Review, Vol. 13 No. 4, pp. 143-55.

Tharenou, P. (2001), “Going up? Do traits and informal social processes predict advancing inmanagement?”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 44 No. 5, pp. 1005-17.

The spouse ofthe female

manager

613

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

Tuomaala, S. (2008), “Holhouksenalaisuudesta koulutetuksi ja vapaaksi kansalaiseksi”, availableat: www.aanioikeus.fi/artikkelit/index.htm (accessed July 31, 2008).

Valtonen, H. (2004), “Minakuva, arvot ja mentaliteetit. Tutkimus 1900-luvun alussa syntyneidentoimihenkilonaisten omaelamankerroista”, Jyvaskyla Studies in Humanities, No. 26.

Vanhala, S. (2005), “Huono omatunto, naisjohtaja perheen, tyon ja uran tormayskurssilla”, Tyo jaihminen, Vol. 19 No. 2, pp. 199-214.

Varanka, J., Narhinen, A. and Siukola, R. (2006), “Men and gender equality, towards progressivepolicies”, available at www.stm.fi/Resource.phx/publishing/store/2007/01/hu 1168255554694/passthru.pdf (accessed August 5, 2008).

White, B. (1995), “The career development of successful women”, Women in ManagementReview, Vol. 10 No. 3, pp. 4-15.

White, B., Cox, C. and Cooper, C.L. (1997), “A portrait of successful women”, Women inManagement Review, Vol. 12 No. 1, pp. 27-34.

Further reading

Gergen, K.J. (1991), The Saturated Self: Dilemmas of Identity in Contemporary Life, Basic Books,New York, NY.

Gergen, K.J. and Gergen, M.M. (1983), “Narratives of the self”, in Sarbin, T.R. and Scheibe, K.E.(Eds), Studies in Social Identity, Praeger Publishers, New York, NY, pp. 254-73.

Madjar, N., Oldham, G.R. and Pratt, M.G. (2002), “There’s no place like home? The contributionsof work and nonwork creativity support to employees’ creative performance”, Academy ofManagement Journal, Vol. 45 No. 4, pp. 757-67.

Thompson, C.A., Beauvais, L.L. and Lyness, K.S. (1999), “When work-family benefits are notenough: the influence of work-family culture on benefit utilization, organizationalattachment, and work-family conflict”, Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 54 No. 3,pp. 392-415.

About the authorsSuvi Valimaki is a Doctoral Candidate in the School of Business and Economics at the Universityof Jyvaskyla, Finland. Suvi Valimaki is the corresponding author and can be contacted at:[email protected]

Anna-Maija Lamsa is Professor of Human Resource Management in the School of Businessand Economics at the University of Jyvaskyla, Finland.

Minna Hiillos is Dean of MBA and Open Programs in HSE Executive Education Ltd atHelsinki School of Economics, Finland.

GM24,8

614

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: [email protected] visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

This article has been cited by:

1. Suvi Heikkinen, Anna-Maija Lämsä, Minna Hiillos. 2014. Narratives by women managers about spousalsupport for their careers. Scandinavian Journal of Management 30:1, 27-39. [CrossRef]

2. Suvi Susanna Heikkinen. 2014. How do male managers narrate their female spouse's role in their career?.Gender in Management: An International Journal 29:1, 25-43. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

3. Jan Selmer, Vesa Suutari, Liisa Mäkelä, Marja Känsälä, Vesa Suutari. 2011. The roles of expatriates'spouses among dual career couples. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal 18:2, 185-197.[Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

4. Elizabeth Hamilton Volpe, Wendy Marcinkus Murphy. 2011. Married professional women's career exit:integrating identity and social networks. Gender in Management: An International Journal 26:1, 57-83.[Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

Dow

nloa

ded

by U

NIV

ER

SIT

Y O

F JY

VA

SKY

LA

, Mrs

Suv

i Hei

kkin

en A

t 05:

12 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

![Mission Manager[1]](https://static.fdokumen.com/doc/165x107/6313fe215cba183dbf075a68/mission-manager1.jpg)