The role of leadership in the implementation of person-centred care using Dementia Care Mapping: a...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of The role of leadership in the implementation of person-centred care using Dementia Care Mapping: a...

The role of leadership in the implementation of person-centredcare using Dementia Care Mapping: a study in three nursinghomes

ANNE MARIE MORK ROKSTAD RN , MH S1, SOLFRID VATNE RN , P h D

2, KNUT ENGEDAL MD , P h D3 and

GEIR SELBÆK PhD4

1PhD Candidate, Ageing and Health, Norwegian Centre for Dementia Research, Education and ServiceDevelopment, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, 2Professor, Molde University College, Specialized University inLogistics, Molde, 3Professor and Research manager, Ageing and Health, Norwegian Centre for Research,Education and Service Development, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo and 4Research Director, Centre for Old agePsychiatry Research, Innlandet Hospital Trust, Ottestad, Norway

Correspondence

Anne Marie Mork Rokstad

Ageing and Health, Norwegian

Centre for Research, Education

and Service Development,

Department of Geriatric Medicine

Oslo University Hospital

Bygg 37 Ullevaal

0407 Oslo

Norway

E-mail: anne.marie.rokstad@

aldringoghelse.no

ROKSTAD A.M.M., VATNE S., ENGEDAL K. & SELBÆK G. (2013) Journal of NursingManagementThe role of leadership in the implementation of person-centred care using

Dementia Care Mapping: a study in three nursing homes

Aim The aim of this study was to investigate the role of leadership in theimplementation of person-centred care (PCC) in nursing homes using Dementia

Care Mapping (DCM).

Background Leadership is important for the implementation of nursing practice.However, the empirical knowledge of positive leadership in processes enhancing

person-centred culture of care in nursing homes is limited.

Method The study has a qualitative descriptive design. The DCM method wasused in three nursing homes. Eighteen staff members and seven leaders

participated in focus-group interviews centring on the role of leadership infacilitating the development process.

Results The different roles of leadership in the three nursing homes, characterized

as ‘highly professional’, ‘market orientated’ or ‘traditional’, seemed to influenceto what extent the DCM process led to successful implementation of PCC.

Conclusion and Implications for Nursing Management This study provided useful

information about the influence of leadership in the implementation of person-centred care in nursing homes. Leaders should be active role models, expound a clear

vision and include and empower all staff in the professional development process.

Keywords: dementia, Dementia Care Mapping, focus-group interviews, leadership,

nursing homes, person-centred care

Accepted for publication: 18 January 2013

Introduction

Leadership is important for the implementation of

nursing practice. However, the empirical knowledge

of positive leadership in processes enhancing the per-

son-centred culture of care in nursing homes is lim-

ited. In this study, Dementia Care Mapping (DCM)

was used as a structured method to implement person-

centred care (PCC) in dementia care practice.

Person-centred dementia care was first described by

Kitwood (1997), who suggested the need for a new

culture of care that would preserve personhood in the

course of the development of the dementia disease

(Kitwood 1997). Based on this, Brooker (2007)

DOI: 10.1111/jonm.12072

ª 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1

Journal of Nursing Management, 2013

presented the following four main components in the

performance of PCC: valuing people with dementia;

using an individual approach that recognizes the

uniqueness of the person; making an effort to under-

stand the world from the perspective of the person; and

providing a supportive social environment (Brooker

2007). Additionally, McCormack and McCance (2006)

developed a framework for person-centred nursing com-

prising four constructs: prerequisites focusing on the

skills of the nurse; the care environment; person-centred

processes as shown in the care practice; and the expected

outcome (McCormack & McCance 2006, McCormack

et al. 2010). Strategies for the clinical delivery of PCC

for persons with dementia include the incorporation of

knowledge of the person’s history, the conduct of remi-

niscence sessions, providing validation therapy, priori-

tizing well-being ahead of routines and care tasks,

simplifying and personalizing the environment and per-

forming activities that promote a good life for the resi-

dent (Edvardsson et al. 2008). The DCM method is

based on the use of standardized observation by a

trained professional, which identifies the well-being and

behaviour of the patients and the interactions between

care staff and the patients. The results of these observa-

tions are discussed in a feedback session with the care

staff. Based on this feedback, actions to improve care

practice for the residents are defined and put in the care

plans (Brooker & Surr 2005, British Standard Institution

(BSI) 2010).

Good leadership plays a key role in developing

nurses’ understanding of patients’ needs and values

and the acceptance of new innovations to obtain

successful change and a positive care culture (Rycroft-

Malone et al. 2004, Scott-Cawiezell et al. 2005,

Gifford et al. 2007, Laschinger et al. 2007, Brady &

Cummings 2010, Jeon et al. 2010). By strengthening

the leadership skills of nursing home leaders, it may

be possible to achieve and sustain improvements that

are essential to promote a better quality of life for the

residents (Harvath et al. 2008). This study is about

the value of leadership in a structured process aimed

at implementing PCC in nursing home settings.

Literature review

‘Implementation’ is the aggregation of processes

needed to get an intervention into use within an orga-

nization on a daily basis (Rabin et al. 2008). It is a

social process modified by the context in which it

takes place (Davidoff et al. 2008). Engaging the team

members who are involved in an implementation

process is often overlooked, and therefore a leadership

strategy to accomplish this is necessary (Pronovost

et al. 2008).

According to Northouse’s definition, ‘leadership’ is

a process whereby an individual influences a group of

individuals to achieve a common goal (Northouse

2004). Nursing leaders have to take actions to achieve

a preferred future situation (Cummings 2011), provide

guidance for solving complex problems (Smith et al.

2006) and create structures that will facilitate the

implementation of useful processes for delivering nurs-

ing care (Anthony et al. 2005).

Four types of leader, who have the responsibility of

engaging the staff involved, have been identified by

Damschroder et al. (2009): (i) opinion leaders, who

are individuals within the organization who have for-

mal or informal influence on the attitudes and beliefs

of their colleagues; (ii) formally appointed internal

implementation leaders – for example, team leaders or

project leaders; (iii) champions, who dedicate them-

selves to supporting, marketing and overcoming resis-

tance to change within the organization; and (iv)

external agents of change with the formal role of

influencing or facilitating the process in a desirable

direction (Damschroder et al. 2009).

Previous research shows that nursing leadership

styles, focusing on people and relationships – such as

transformational leadership – are associated with

improved job satisfaction for nurses (Cummings et al.

2008, 2010), increased levels of intention to stay in

their current positions (Cowden et al. 2011) and bet-

ter patient outcomes (Anderson et al. 2003, Wong &

Cummings 2007, Tomey 2009). ‘Transformational

leadership’ is the process by which leaders and follow-

ers raise one another to higher levels of morale and

motivation. The main goal for transformational

leaders is to establish a shared vision and to bring fol-

lowers up to the level where they can succeed in

accomplishing organizational tasks without any direct

leading interventions (Burns 1978). Factors that moti-

vate nurses to perform well are identified as: autono-

mous practices; working relationships; resource

accessibility; individual nurse characteristics; and the

leadership style (Brady & Cummings 2010). A study

exploring the differences in leadership behaviour in

high- and low-performing nursing homes (Forbes-

Thompson et al. 2007) concluded that the creation of

clear, explicit and coherent goals, giving a strong

sense of mission in the organization, was important.

In addition, the leaders should be willing to help out

on the floor, promoting strong lateral decision-making

as opposed to the traditional top-down method. The

need for communicated goals and visions has been

ª 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

2 Journal of Nursing Management

A. M. Mork Rokstad et al.

pointed out as crucial to sustaining a high quality of

care in several previous studies ((Morgan et al. 2005,

Stolee et al. 2005, Scalzi et al. 2006).

Closely related to transformational leadership is

‘authentic leadership’, described as ‘leading by exam-

ple’. Authentic leadership is leader behaviour

grounded in positive psychological capacity and sound

ethical standards (Avolio & Gardner 2005,

Walumbwa et al. 2008), and it has the potential to

provide healthy working environments for care staff

and to optimize patient outcomes (Wong et al. 2010).

Authentic leaders are clear and open about their

perspectives, their actions are consistent with their

expressed values, they share information and feelings

appropriate for the situation with their employees,

and their self-awareness is demonstrated in their

understanding of their own strengths and weaknesses

(Gardner et al. 2005).

Based on a person-centred nursing framework

(McCormack & McCance 2006), a conceptual model

of transformational, situational leadership in nursing

homes has been presented by Lynch et al. (2011). This

model integrates person centeredness with leadership

thinking in order to impact effectively on the perfor-

mance of the staff in delivering PCC. Situational lead-

ership claims that there is no one leadership style that

works in all situations and outlines four sets of leader-

ship behaviour: directing (the leader uses one-

way-communication to give detailed instructions),

coaching (the leader listens to and takes in to consid-

eration the followers’ feelings, ideas and suggestions),

supporting (the locus of control for day-to-day

decision-making shifts over to assistants) and delegat-

ing (the assistant is given the responsibility for

decisions and the implementation of actions) (Hersey

& Blanchard 1993). Combining the key components

of situational leadership and the person-centred

nursing framework, Lynch et al. (2011) delineates

four central approaches for leadership: (i) developing

a shared vision of person centeredness and identifying

important outcomes; (ii) focusing on the impact of the

context and identifying situational conditions that

influence the delivery of patient care in practice; (iii)

matching leadership style to the development level of

the assistant using directive or supportive behaviour;

and (iv) changing the leadership behaviour flexibly so

as to take the assistant through the levels from begin-

ner to competent and committed carer (Lynch et al.

2011), or what we may call an ‘empowered carer’.

Kane-Urrabazo (2006) concludes that leaders need

to put support systems into place that allow the

staff the opportunity to empower themselves.

Empowerment is described as the process of enabling

others to do something, to make them feel free to act

on their own judgement and trust their own decisions.

The principle of empowerment contributes to each

carer’s sense of worth (Covey 1991) and stimulates

nurses to reach a higher standard (Spence Laschinger

2008). Several previous studies have been made on

‘structural empowerment’, defined as the presence of

social structures in the work place that enable employ-

ees to accomplish their work in meaningful ways

(Kanter 1993). These studies indicate that the presence

of structural empowerment results in: improved levels

of job satisfaction (Laschinger et al. 2001, 2004,

Manojlovich & Spence Laschinger 2002); better

organizational recruitment and commitment (Laschin-

ger et al. 2001, 2009); more organizational trust, jus-

tice and respect (Laschinger et al. 2001, Laschinger &

Finegan 2005); and an enhanced quality of patient

care (Spence Laschinger 2008). Additionally, among

the staff, lower levels of job strain, less burnout and

reduced turnover intentions have been reported

(Laschinger et al. 2003, Spence Laschinger et al.

2009a). There is a link between work-place empower-

ment and engagement with the task. Nurses who

engage positively in their work with vigour and dedi-

cation can make a difference to the quality of care by

inspiring colleagues and making the work setting

attractive (Spence Laschinger et al. 2009b).

The aim of this study was to investigate the role of

leadership in the implementation of PCC in nursing

homes using DCM. The main areas of investigation

were: how the leaders prepared and supported the

care staff during the development process; and what

the staff thought about the experience of taking part

in this process. To answer this, we compared three

nursing homes.

Methods

Design

The study had a qualitative descriptive design using

focus-group interviews to answer the main research

question. DCM was used as a method of implement-

ing PCC over a 12-month period.

Sample and settings

The leaders and staff of three nursing homes called

NHA, NHB and NHC were recruited from three

different parts of Norway. Trained DCM users,

working as supervisors in departments of geriatric

ª 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Journal of Nursing Management 3

Implementation of PCC in nursing homes using DCM

psychiatry, selected, contacted and asked the nursing

homes for their participation. The researcher

(A.M.M.R.) planned the DCM process in collabora-

tion with the DCM users, and was otherwise not

directly involved with the nursing homes in the DCM

process. The researcher planned and carried out six

focus-group interviews with the formal leaders and

the care staff at the participating nursing homes. Sepa-

rate focus groups were formed for the staff and the

leaders at each nursing home. The care staff, who par-

ticipated in the focus groups, consisting of both regis-

tered and auxiliary nurses, were all experienced

members of the nursing team. The leaders were head

managers and charge nurses. In NHC there was only

one responsible leader for the participating ward, and

she was interviewed individually.

Table 1 shows the number of participants from each

nursing home in the focus-group interviews, nursing-

home characteristics and the characteristics of the

nursing staff.

There were some differences in size, organization

and the structure of leadership. NHA had 50 resi-

dents, a continuous budget and one head manager of

the nursing home. Additionally, there were one charge

nurse in each ward housing 24 and 26 residents and

about 50 care staff members on each ward. NHB had

127 residents, activity-based income and a temporarily

appointed head manager of the nursing home. Two

charge nurses were each responsible for one ward

including 34 residents and about 70 care-staff employ-

ees. There were also informal leaders in each of the

wards. NHC had 64 residents and a continuous bud-

get. There was no head manager present at this nurs-

ing home as it was organized as part of a group of

nursing homes in the municipality with one manager

responsible for all the institutions. There was a charge

nurse in the participating ward and informal leaders.

All the leaders were on duty throughout the study per-

iod except for one nurse in charge of one of the wards

in NHB.

The nursing staff characteristics (Table 1) reveal

that most of the care staff members were women.

NHB had the highest number of staff working in their

current job for several years. Nearly half of the staff

had been there for more than 15 years. NHC was

opened 3 years before the project started and the

whole staff had been employed at the nursing home

since the beginning. NHB had the highest number of

staff employed for at least 75% of their time and also

the highest percentage of staff having additional train-

ing.

The implementation of PCC using DCM

In the DCM process, observations of the residents

were made over 6 h and altogether there were three

observations at 6-months intervals in each ward. Dur-

ing the observations the care staff were encouraged to

carry out their daily practice as usual. The mappings

were followed by feedback sessions with the staff, run

Table 1

Sample and settings characteristics

NHA NHB NHC Total

Focus group interview participants

Number of staff members interviewed 6 6 6 18

Number of leaders interviewed 3 3 1 7

Nursing home characteristics

Participating wards (number of patients on the wards) 2 (24 + 26) 2 (34 + 34) 1 (24) 5 (118)

Number of residents in the nursing homes 50 127 64 241

Nursing staff characteristics*N = 24 N = 23 N = 7 N = 54

Female gender (%) 22 (92) 21 (91) 7 (100) 50 (93)

Years in current job (%):

<1 year 5 (21) 2 (9) 0 (0) 7 (13)

1–5 years 10 (42) 5 (23) 7 (100) 22 (42)

6–15 years 9 (37) 5 (23) 0 (0) 14 (26)

Over 15 years 0 (0) 10 (45) 0 (0) 10 (19)

Staff working at least three-quarter time (%) 17 (71) 21 (91) 4 (57) 42 (78)

Occupation (%):

Unskilled care workers 3 (13) 3 (13) 1 (14) 7 (13)

Auxiliary nurses 13 (54) 11 (48) 3 (43) 27 (50)

Registered nurses 8 (33) 9 (39) 3 (43) 20 (37)

No additional training (%) 19 (91) 11 (61) 6 (86) 36 (78)

*Nursing-staff characteristics were collected by means of a self-report questionnaire.

ª 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

4 Journal of Nursing Management

A. M. Mork Rokstad et al.

by the trained external DCM users. The care staff

were requested to participate actively in the feedback

session and to share reflections on the observed find-

ings and their implications for their care practice on a

daily basis. Based on these discussions, action plans

could be made for each resident. The actions would

be evaluated by means of the repeated DCM observa-

tions.

Interviews and analysis

The focus-group interviews were made after the sec-

ond DCM observation at 6 months and repeated at

the end of the implementation time. They were based

on a semi-structured interview guide (Freeman 2006,

Krueger & Casey 2009, Kvale & Brinkmann 2009).

The main question to the leaders was: How did you

reflect and act as a leader in the preparation and the

developmental phases of using DCM? The nursing

staff were asked to say how they were involved and

stimulated by their leaders in the process of imple-

menting person-centred care in their daily nursing

practice. Both leaders and staff were asked to share

their experiences with the DCM method and how it

influenced their care practice from day to day.

The interviews were tape recorded, transcribed and

cross-checked by listening to the taped interviews. A

qualitative content analysis with a conventional

approach was used to analyse the interviews. The

analysis was not informed by a theoretical framework

(Graneheim & Lundman 2004, Hsieh & Shannon

2005, Zhang & Wildemuth 2009). Initially, each

interview was analysed separately. The text was sorted

into content areas, and was read through several times

to obtain a sense of the whole. Then, the text was

divided into ‘meaning units’ that were condensed and

labelled with a code using NVivo 8. A scheme consist-

ing of main categories and subcategories was con-

structed. The text was further organized and put into

a matrix making it possible to compare the three nurs-

ing homes. The information was analysed at the group

level, and the interaction within the focus groups was

not emphasized. Based on the preliminary analysis, a

subsequent interview was made with each group. In

this interview the participants were given the opportu-

nity to validate or/and supplement their statements

made in the first interview and confirm or deny the

temporary interpretations made by the researchers.

No interpretations were denied. The next step in the

content analysis was to identify prominent themes

based on the interpretation agreed by the participants.

To address the research question, descriptions of both

the context and the prominent themes were identified.

The matrix and comparisons between the nursing

homes were made in collaboration with the second

author (S.V.).

Results

Context

The context in which the implementation of PCC took

place was different in the three nursing homes, as

described below.

Vision and purpose

In the focus-group interviews, the leaders spoke about

the development of their vision and their main goals

for the home and the staff commented on how these

had influenced their daily practice. NHA had a clear

professional vision ahead of the DCM process, and

during the implementation project the vision was

extended and put into action by a group of 12 staff

members in collaboration with the leaders. NHB also

had a written vision statement, made 5 years earlier,

which consisted of 13 sentences pin-pointing the goals

of the institution. However, the staff found it difficult

to remember all the points. The nursing home leader

at NHC knew there had been a vision for the nursing

home, but she did not remember the content of it and

wanted to create a new vision. There was no exact

plan for this process and nothing happened during the

project in NHC.

Professional development

The focus on professional development in the three

institutions was different. NHA had chosen to focus

on the development of psychosocial interventions and

PCC, and the leaders were fully aware of the need to

see the development of the professionals’ competence

as a long-term project. The nursing home leader at

NHB wanted to develop the institution as a model for

others and, on this basis, to ensure the funding of the

institution. The leadership had developed their own

dementia plan and wanted to be able to arrange open

seminars for nursing homes in the local authority area.

They were also open for visits that displayed what

they had developed in terms of best practice in demen-

tia care. The staff, by contrast, claimed they did not

feel prepared to care for persons with dementia as a

result of organizational changes in recent years. The

wards had been transformed from traditional nursing

home units into special care units for persons with

dementia. NHC had a limited focus and no plan for

ª 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Journal of Nursing Management 5

Implementation of PCC in nursing homes using DCM

staff development in general and was more based on

traditional experience. The staff, however, said that

they would like to learn more about dementia.

The influence of the funding system

NHB differed from the other nursing homes in having

activity-based funding, meaning that they were

financed according to reported, detailed action plans

made for each resident. That means a focus on the

connection between activities and funding, which is a

market-orientated system. This documentation, which

was time consuming and experienced as a burden on

the leaders, had to be updated to release the funding.

These plans gave the care staff only a limited opportu-

nity for improvization and flexibility in their relations

with the residents. This kind of influence from the

funding system was not reported from the other nurs-

ing homes.

Based on the findings of contextual differences in

the three nursing homes (Box 1), we chose to charac-

terize the nursing homes as: the ‘highly professional’

nursing home (NHA), the ‘market-orientated’ nursing

home (NHB) and the ‘traditional’ nursing home

(NHC).

Main findings

Two main themes, leadership support (Box 1) and the

experience of the use of DCM in the implementation of

person-centred care (Box 2), were chosen to answer the

research questions on how the leaders supported

the care staff and how staff experienced taking part in

the DCM process. The connection between the partici-

pant’s quotes and the condensed meaning is shown in

the matrices (Boxes 1 and 2).

Leadership support (Box 1)

The leaders in the ‘highly professional’ nursing home

took an active part in the nursing practice and they

saw themselves as role models for the care staff. This

participation from the leaders was considered as cru-

cial by the staff members. They felt that their initia-

tives to act in the best interests of the residents were

accepted and appreciated by the leaders and they felt

encouraged and supported to deliver good quality

care. The leaders confirmed that they admired the

staff for their engagement and skills.

The leaders in the ‘market-orientated’ nursing home

said that they had no chance of being present on the

wards on a daily basis and had to lead through

informal leaders on the wards. They stated that their

initiatives to motivate the staff in favour of profes-

sional development were met by resistance from the

staff. The staff confirmed that they experienced their

leaders as only sporadically present on the ward. In

contrast to the leaders’ experience of resistance to

development, they asked for more continuous supervi-

sion.

The leader in the ‘traditional’ nursing home stated

that she gave support to the ward staff on occasions

when there were special needs. She encouraged the

staff to use their individual skills in their care practice.

The staff said they felt stretched to deliver good qual-

ity care. They had a good relationship with their lea-

der but, on a daily basis, they felt alone and

forgotten.

The experience of the use of DCM in the

implementation of person-centred care (Box 2)

The leaders in the ‘highly professional’ nursing home

claimed that the DCM process had motivated both

staff and leaders to join forces for further develop-

ment. The staff felt more focused on delivering indi-

vidualized, person-centred care and the leaders had

the chance to see the results of the action taken in the

feedback of the repeated DCM observations. Both

leaders and staff at the ‘market-orientated’ nursing

home found the DCM feedback useful and interesting.

However, the results of the mappings were not

reflected in action plans to be followed up and

because of this, the staff’s interest in participating in

the process decreased. In the ‘traditional’ nursing

home, the leader stated that the DCM process had

raised consciousness and reflections concerning care

practice. The staff claimed that the constructive feed-

back after the DCM observations was a good experi-

ence. To what extent the process had developed their

skills in PCC they were not able to tell.

Discussion

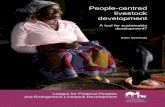

The findings in this study, as illustrated in Figure 1,

show major differences in the leadership in the partici-

pating nursing homes. These differences seem to influ-

ence the implementation of person-centred dementia

care even although the method used (DCM) in the

implementation process was the same.

The role of the leadership

The findings underline the importance of transforma-

tional leadership (Burns 1978, Wong & Cummings

2007, Tomey 2009, Cummings et al. 2010) and

especially the need for a clear and coherent vision to

ª 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

6 Journal of Nursing Management

A. M. Mork Rokstad et al.

obtain professional development and person-centred

dementia care. PCC is described as a ‘value base’

(Brooker 2007), and the goals for nursing practice

need to reflect these values to make them normative.

The ‘highly professional’ nursing home seemed to

manage to incorporate the values of PCC both in their

written vision and in the processes implementing it.

The vision of the ‘market-orientated’ nursing home

was more focused on terms like service and standard-

ized best practice, and the staff seemed more distant

to the meaning of PCC. The goals of effectiveness and

service, thought to be incompatible with the values of

Box 1

Theme: leadership support; condensed meaning units and statements from leaders and staff

Nursing home with key

points of context

Leaders Care staff

Condensed

meaning unit Statement

Condensed

meaning unit Statement

The ‘highly professional’

nursing home

� Clear and

integrated vision

� Long-term focus on

professional

development

� Basic funding

with no direct

influence on

daily practice

The leaders took

part in care

practice as models

‘We have to keep the idea

of person-centredness

warm all the

time. I have been present

on the ward

to follow up the actions;

we have decided

to focus on taking part in the

daily care practice.’

Staff felt

motivated by

the leaders

‘It all depends on the

charge nurse being

there to drag us along.’

The leaders showed

admiration

and encouraged the

staff initiatives for better

care practice

‘I admire the skills of

my staff, and,

within the aim of our

institution,

I encourage

their initiatives and ideas for

better care practice.’

Staff felt

encouraged to

deliver good

quality care

‘The more we do,

the happier our

leaders are; to

take good care of

the residents is what

matters the most.’

The ‘market-orientated’

nursing home

� Five years old

complicated vision

� Inconsistency between

the leader’s

and the care staff’s

experience of

professional

development

� Activity-based

funding giving

detailed instructions

on care practice

The leaders were not

able to be

present on the ward

and had to lead through

others

‘I cannot be present on the

wards on a daily

basis, so I have to lead the

care practice

through others (nurse 1).

I find this frustrating.’

Staff stated that

the leader

was only

sporadically

present on

the ward

‘I cannot remember

seeing her on the ward;

well, she walks through

the ward now and then.’

The leaders tried to motivate

the staff to participate in

professional development

but were met by insecure

and resistant staff members

‘I try to motivate and spread

professional

impulses but it kind of seems

like they don’t want it.’

‘Some of them look unsure

of themselves and

a little bit afraid to make their

own decisions.’

Staff asked for

continuous

supervision

‘I would like to have

some continuous

supervision.’

The ‘traditional’

nursing home

� No active vision known

� Professional

development asked for

by the staff but

not put into a

structured plan

� Basic funding

with no direct

influence on

daily practice

The leader gave support on

occasions of

special need on the ward

‘I can be of help on

the wards if

there is special

need and my time schedule

makes it possible.

I try to give the staff signals of

support, and I

participate in decisions

concerning the residents.’

Staff felt stretched

to deliver

good quality care

‘I think we stretch

ourselves as best

we can to meet

the needs of

the residents.’

The leader encouraged

the staff to use

their individual skills

‘I try to support them

and regularly

tell them what a

good job I think they

do and I try

to encourage

them to use their

individual skills.’

Staff loved their

leader but felt

forgotten from

day to day

‘Our leader is very

pleasant and we truly

love her, but on the

daily basis we

feel a little bit forgotten.’

ª 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Journal of Nursing Management 7

Implementation of PCC in nursing homes using DCM

PCC, frustrated both leaders and staff. In the ‘tradi-

tional’ nursing home a verbal vision was set out and

demonstrated by the leader in the way she acted and

supported the staff but her goals were unknown to

her nursing staff. These findings are supported by pre-

vious research which underlines the need of clear,

explicit and coherent goals to obtain results in the

quality of nursing (Scalzi et al. 2006, Forbes-Thomp-

son et al. 2007, Cummings 2011).

Situational leadership is recommended to develop a

person-centred culture of care (Lynch et al. 2011). To

practise situational leadership the leaders need to be

present on the wards, know the skills of their

employees and choose the appropriate leadership

behaviour. They have to choose directing, coaching,

supporting or delegating strategies to fit the nurses’

developmental levels and competence (Hersey &

Blanchard 1993). In the ‘highly professional’ nursing

home, the leaders were present on the wards on a

daily basis and the staff felt supported and engaged.

Given the circumstances of high work pressure and

many administrative tasks, the leaders at the ‘market-

orientated’ nursing home could not manage to take

this role in the wards. This fact seemed to result in

frustrated leaders and resigned staff. The leader at

the ‘traditional’ nursing home stated that she sup-

ported her staff on occasions of special need and par-

ticipated in decisions concerning the patients. The

staff felt they had to stretch themselves and manage

on their own as they felt forgotten. The fact that the

leader had no opportunity to be present on the wards

on a daily basis and observe the nurses’ needs for

supervision and support may have limited the effect

of her good intentions to support the staff when

needed.

Authentic leaders (Wong et al. 2010) are role mod-

els and supervisors demonstrating their professional

and ethical standards in the way they communicate

openly and act consistently with their expressed val-

ues. Such leadership behaviour, as we identified at the

‘highly professional’ nursing home, influences the

staff’s engagement, motivation and commitment

(Anderson et al. 2003, Avolio & Gardner 2005, Scalzi

et al. 2006). The situations at the ‘market-orientated’

and ‘traditional’ nursing homes were different, as the

leaders were responsible for larger groups of staff and

patients and had a more limited opportunity to ‘lead

by example’ (Avolio & Gardner 2005). An alternative

Box 2

Theme: the experience of the use of Dementia Care Mapping (DCM) in the implementation of person-centred care (PCC); condensed

meaning units and statements from leaders and staff

Nursing home

Leaders Care staff

Condensed meaning unit Statement Condensed meaning unit Statement

The ‘highly

professional’

nursing home

The process had made

staff and leaders joined

forces for development

‘I think the DCM process

has inspired us and

made us join forces in

the development of our

care practice because it

gives us the chance to

see the results of the

actions we choose to

take.’

The staff felt more focused

on delivering

individualized care

‘It (DCM) makes us focus

on the residents and

what to do together in a

staff group to develop

individualized care.’

The ‘market-

orientated’

nursing home

Both staff and leaders

found the first feedback

of the DCM observations

interesting but the

interest decreased during

the process

‘I think the feedback was

interesting and so did the

staff, but at the second

feedback session there

were only two of the staff

present. That’s really

disappointing.’

The staff found the

feedback useful but

asked for concrete

actions in the

continuation of the

feedback meeting

‘The feedback was useful

and made us reflect upon

how we meet the

patients, but no concrete

action was taken to

follow up the discussions

from the feedback.’

The ‘traditional’

nursing home

The process raised the

staff’s consciousness

‘The staff members have

become more aware of

ethical issues and their

consciousness

concerning their own

care practice has

increased.’

To get constructive

feedback was a good

experience for the staff

‘Constructive feedback

gives us the opportunity

to change. To be

observed and get

feedback from someone

outside (DCM mappers)

was a great experience.’

ª 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

8 Journal of Nursing Management

A. M. Mork Rokstad et al.

to this unsatisfactory situation could have been to

appoint internal implementation leaders (Damschroder

et al. 2009), who would be given the formal authority

and responsibility as project or team leaders and

enabled to be role models and supervisors on the

wards. A study of barriers and enablers to a culture of

change in nursing homes concluded that a critical

mass of change champions appeared to have a signifi-

cant influence in implementing and sustaining changes

(Scalzi et al. 2006). Change champions are individu-

als, not formal leaders, who dedicate themselves to

supporting, marketing and driving through an imple-

mentation by overcoming the resistance that the inter-

vention may provoke (Damschroder et al. 2009).

Opinion leaders having formal or informal influence

on the attitudes and beliefs of their colleagues and

external change agents also influence the development

process (Damschroder et al. 2009). In this study, we

focused on the role of the formal leaders, but studies

of the influence of different types of intervention lead-

ers would be interesting as well.

Staff empowerment has been emphasized in several

previous studies as a key strategy for successful pro-

fessional development (Kane-Urrabazo 2006, Spence

Laschinger 2008, Spence Laschinger et al. 2009b).

Encouraging the staff as a group to be actively

involved and take shared responsibility for the resi-

dents’ care is crucial, as demonstrated at the ‘highly

professional’ nursing home. The staff felt empowered

and trusted to take their own decisions in their daily

care practice. At the ‘traditional’ nursing home the

nursing staff were trusted by their leader but did not

feel supported in their work on a daily basis. In

addition, there were no formal delegation structures

to give staff members at the unit level the power and

opportunity to act as implementation leaders. They

lacked knowledge of how to treat persons with

dementia and asked for supervision and education.

The staff at the ‘market-orientated’ nursing home

also felt to some extent uncertain of how to act to

meet the patients’ needs and asked for continuous

formal supervision. However, the activity-based fund-

ing gave signals on what kind of activities the resi-

dents could be offered, and the activities were even

described with time limits. A paradox is the fact

that, comparing the three nursing homes, the ‘mar-

ket-orientated’ nursing home had the highest percent-

age of care staff with additional training, many years

of experience in the current job and the highest

percentage of staff working at least 75% of full time

(Table 1).

Summing up, the ‘highly professional’ nursing

home seemed to succeed in implementing PCC in

their daily practice through support from their lea-

der. In the ‘market-orientated’ nursing home, PCC

awareness was achieved but did not lead to change

Context

The Dementia Care Mapping (DCM) process

Implementation of person-centred care (PCC)

PCC awareness and practice

PCC awareness PCC awareness and reflections on it

Professional supportive leadership

through participation

in practicecare

Nodirectly

supportive leadership

Supportive leadership only

on request

Nursing home A'Highly professional'

-Clear and integrated vision-Long-term focus on professional development

-Basic funding

Nursing home B'Market-orientated'

-Complicated vision-Inconsistent professional development

-Activity-based funding

Nursing home C'Traditional'

-No vision-No structure for professional development

-Basic funding

Figure 1

The influence of context and the role of leadership in the implementation of person-centred care (PCC) using the Dementia Care Mapping

(DCM) process.

ª 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Journal of Nursing Management 9

Implementation of PCC in nursing homes using DCM

in care delivery. The ‘traditional’ nursing home also

achieved PCC awareness and increased reflection

among the care staff, but the influence on care prac-

tice was uncertain. These two had no support of

their leaders. The differences in how much the three

nursing homes succeeded in implementing PCC

might have several explanations. However, transfor-

mational, situational leadership and the existence of

a clear and coherent vision, clarifying the content of

PCC, seemed to be important. Additionally, the

leadership seemed to influence the nursing staff’s

experiences of empowerment and their ability to put

the idea of PCC into action to meet the patients’

needs. The way the nursing homes where organized,

including the funding system, seemed to have influ-

ence on the implementation process and needs to be

investigated further. Additionally, research is needed

on the use and influence of different kind of inter-

vention leaders.

Methodological considerations

Focus group interviews were chosen as the method of

finding out about the role of leadership in develop-

mental processes using DCM. The advantages of using

focus groups are that it is an efficient method of gath-

ering the viewpoints of many individuals in a short

time, and the interaction within the group may lead to

richer expressions of opinion. However, there is a

chance that some group participants find it difficult to

express themselves in front of the group (Polit & Beck

2008). To encourage open discussion within the

groups, the participants were divided into groups of

staff and groups of leaders. The content of the inter-

views in the separated groups of staff and leaders

could be compared to validate the different opinions

expressed.

The coding was made by the main researcher

(A.M.M.R.), and the second writer (S.V.) reviewed

and questioned the logic and consistency in the cod-

ing and the preliminary interpretations. The second

round of interviews contributed to the validation of

their previous conclusions. After much discussion, the

main researcher (A.M.M.R.) and the co-writers

summed up the findings and worked out the final

conclusions.

Conclusion

This study gave useful information about the influ-

ence of leadership on the implementation of PCC

using DCM in nursing homes. Leaders have a central

role in drawing up a clear and consistent professional

vision, being continuously supportive to the care staff

and taking an active part in the care practice as role

models. Structural empowerment and delegation of

authority and decision making to competent imple-

mentation leaders are alternatives to consider when

organizational limitations make it difficult for the

formal leaders to be present on the wards on a daily

basis. The effect of market-orientated leadership on

the development of PCC in nursing homes should be

investigated further.

Source of funding

The study was funded by the Norwegian Research

Council and The Norwegian Directorate of Health.

Ethical approval

The participants gave their informed written consent

and the study was accepted by the Regional Ethics

Committee for medical research in eastern Norway

(REK-east) and the Norwegian Data Inspectorate

(NSD).

As this study included only three nursing homes,

it would have been possible for those included, espe-

cially the leaders, to recognize themselves in the

description, and there might have been a chance

that they would feel offended or embarrassed.

Efforts have been made in the way the material is

presented to avoid this. During the second inter-

views the participants had the opportunity of con-

firming or distancing themselves from statements in

the first interviews. Nobody wanted to remove any

statements from the material, and the interpretations

were confirmed and to some extent amplified. The

consent of the participants was confirmed prior to

the second batch of interviews.

References

Anderson R.A., Issel L.M. & Daniel R.R. Jr (2003) Nursing

homes as complex adaptive systems: relationship between

management practice and resident outcomes. Nursing

Research 52, 12–21.

Anthony M.K., Standing T.S., Glick J., et al. (2005) Leadership

and nurse retention: the pivotal role of nurse managers. Jour-

nal of Nursing Administration 35 (3), 146–155.

Avolio B.J. & Gardner W.L. (2005) Authentic leadership devel-

opment: getting to the root of positive forms of leadership.

The Leadership Quarterly 16, 315–388.

Brady Germain P. & Cummings G.G. (2010) The influence of

nursing leadership on nurse performance: a systematic

ª 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

10 Journal of Nursing Management

A. M. Mork Rokstad et al.

literature review. Journal of Nursing Management 18 (4),

425–439.

British Standard Institution (BSI) (2010) PAS 800, Use of

Dementia Care Mapping for Improved Person-Centred Care

in Care Provider Organization [WWW document]. Available

at: http://www.bsigroup.com, accessed 29 January 2010.

Brooker D. & Surr C. (2005) Dementia Care Mapping: Princi-

ples and Practice. University of Bradford, Bradford.

Brooker D. (2007) Person-Centred Dementia Care: Making Ser-

vices Better. Jessica Kingsley, London.

Burns J.M. (1978) Leadership. Harper & Row, New York, NY.

Covey S.R. (1991) Principle-Centred Leadership. Simon &

Schuster, New York, NY.

Cowden T., Cummings G. & Profetto-McGrath J. (2011) Lead-

ership practices and staff nurses’ intent to stay: a systematic

review. Journal of Nursing Management 19 (4), 461–477.

Cummings G., Lee H., MacGregor T., et al. (2008) Factors con-

tributing to nursing leadership: a systematic review. Journal

of health services research & policy 13 (4), 240–248.

Cummings G.G., MacGregor T., Davey M., Lee H., Wong

C.A., Lo E., Muise M. & Stafford E. (2010) Leadership styles

and outcome patterns for the nursing workforce and work

environment: a systematic review. International Journal of

Nursing Studies 47 (3), 363–85.

Cummings G. (2011) The call for leadership to influence patient

outcomes. Nursing Leadership 24 (2), 22–25.

Damschroder L.J., Aron D.C., Keith R.E., Kirsh S.R., Alexander

J.A. & Lowery J.C. (2009) Fostering implementation of

health services research findings into practice: a consolidated

framework for advancing implementation science. Implemen-

tation Science 4, 50.

Davidoff F., Batalden P., Stevens D., Ogrinc G. & Mooney S.

(2008) Publication guidelines for quality improvement studies

in health care: evaluation of the SQUIRE project. Quality &

Safety in Health Care 17 (Suppl. 1), i3–9.

Edvardsson D., Winblad B. & Sandman P.O. (2008) Person-

centred care of people with severe Alzheimer’s disease:

current status and ways forward. Lancet Neurology 7,

362–367.

Forbes-Thompson S., Leiker T. & Bleich M.R. (2007) High-

performing and low-performing nursing homes: a view from

complexity science. Health Care Management Review 32,

341–351.

Freeman T. (2006) ‘Best practice’ in focus group research: mak-

ing sense of different views. Journal of Advanced Nursing 56,

491–497.

Gardner W.L., Avolio B.J., Luthans F., Douglas R.M. & Wal-

umbwa F. (2005) Can you se the real me? A self-based model

of authentic leaders and follower development. The Leader-

ship Quarterly 16, 343–372.

Gifford W., Davies B., Edwards N., Griffin P. & Lybanon V.

(2007) Managerial leadership for nurses’ use of research evi-

dence: an integrative review of the literature. Worldviews on

Evidence-based Nursing 4 (3), 126–145.

Graneheim U.H. & Lundman B. (2004) Qualitative content

analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and mea-

sures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today

24, 105–112.

Harvath T.A., Swafford K., Smith K., et al. (2008) Enhancing

nursing leadership in long-term care. A review of the litera-

ture. Research in Gerontological Nursing 1, 187–196.

Hersey P. & Blanchard K.H. (1993) Management of Organiza-

tional Behavior: Utilizing Human Resources, 6th edn. Pre-

ntice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Hsieh H.F. & Shannon S.E. (2005) Three approaches to

qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15,

1277–1288.

Jeon Y.H., Merylin T. & Chenoweth L. (2010) Leadership and

management in the aged care sector: a narrative synthesis.

Australian Journal on Ageing 29 (2), 54–60.

Kane-Urrabazo C. (2006) Management’s role in shaping organi-

zational culture. Journal of Nursing Management 14, 188–194.

Kanter R.M. (1993) Men and Women of the Corporation. Basic

Books, New York, NY.

Kitwood T. (1997) Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes

First. Open University Press, Buckingham.

Krueger R. & Casey M. (2009) Focus Groups: A Practical

Guide for Applied Research. Sage, Los Angeles, CA.

Kvale S. & Brinkmann S. (2009) Interviews: Learning the Craft

of Qualitative Research Interviewing. Sage, Los Angeles, CA.

Laschinger H.K. & Finegan J. (2005) Using empowerment to

build trust and respect in the workplace: a strategy for

addressing the nursing shortage. Nursing Economic$ 23 (1),

6–13.

Laschinger H.K., Finegan J. & Shamian J. (2001) The impact of

workplace empowerment, organizational trust on staff nurses’

work satisfaction and organizational commitment. Health

Care Management Review 26 (3), 7–23.

Laschinger H.K., Finegan J., Shamian J. & Wilk P. (2003)

Workplace empowerment as apredictor of nurse burnout in

restructured health care settings. Longwoods Review 1 (3),

2–11.

Laschinger H.K.S., Finegan J., Shamian J. & Wilk P. (2004) A

longitudinal analysis of the impact of workplace empower-

ment on work satisfaction. Journal of Organizational Behav-

iour 25, 527–545.

Laschinger H.K., Purdy N. & Almost J. (2007) The impact of

leader-member exchange quality, empowerment, and core

self-evaluation on nurse manager’s job satisfaction. Journal of

Nursing Administration 37 (5), 221–229.

Laschinger H.K., Finegan J. & Wilk P. (2009) Context matters.

The impact of unit leadership and empowerment on nurses’

organizational commitment. Journal of Nursing Administra-

tion 39 (5), 228–235.

Lynch B.M., McCormack B. & McCance T. (2011) Develop-

ment of a model of situational leadership in residential care

for older people. Journal of Nursing Management 19 (8),

1058–1069.

Manojlovich M. & Spence Laschinger H.K. (2002) The rela-

tionship of empowerment and selected personality characteris-

tics to nursing job satisfaction. Journal of Nursing

Administration 32 (11), 586–595.

McCormack B. & McCance T.V. (2006) Development of a

framework for person-centred nursing. Journal of Advanced

Nursing 56, 472–479.

McCormack B., Karlson B., Dwing J. & Lerdal A. (2010) Explor-

ing person-centredness: a qualitative meta-synthesis of four

studies. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 24, 620–634.

Morgan D.G., Stewart N.J., D’Arcy C. & Cammer A.L. (2005)

Creating and sustaining dementia special care units in rural

nursing homes: the critical role of nursing leadership. Nursing

Leadership 18, 74–99.

ª 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Journal of Nursing Management 11

Implementation of PCC in nursing homes using DCM

Northouse P.G. (2004) Leadership: Theory and Practice. Sage,

Thousand Oaks, CA.

Polit D. & Beck C. (2008) Nursing Research Generating and

Assessing evidence for Nursing Practice. Lippincott Williams

& Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

Pronovost P.J., Berenholtz S.M. & Needham D.M. (2008)

Translating evidence into practice: a model for large scale

knowledge translation. BMJ 337, a1714.

Rabin B.A., Browson R.C., Haire-Joshu D., Kreuter M.W. &

Weaver N.L. (2008) A glossary for dissemination in imple-

mentation research in health. Journal of Public Health Man-

agement and Practice 14, 117–123.

Rycroft-Malone J., Harvey G., Seers K., Kitson A., McCormack

B. & Titchen A. (2004) An exploration of the factors that

influence the implementation of evidence into practice. Jour-

nal of Clinical Nursing 13, 913–924.

Scalzi C.C., Evans L.K., Barstow A. & Hostvedt K. (2006) Bar-

riers and enablers to changing organizational culture in nurs-

ing homes. Nursing Administration Quarterly 30, 368–372.

Scott-Cawiezell J., Jones K., Moore L. & Vojir C. (2005) Nurs-

ing home culture: a critical component in sustained improve-

ment. Journal of Nursing Care Quality 20, 341–348.

Smith S.L., Manfredi T., Hagos O., Drummon-Huth B. &

Moore P.D. (2006) Application of the clinical nurse leader

role in an acute care delivery model. Journal of Nursing

Administration 36 (1), 29–33.

Spence Laschinger H.K. (2008) Effect of empowerment on profes-

sional practic environments, work satisfaction, and patient care

quality. Journal of Nursing Care Quality 23 (4), 322–330.

Spence Laschinger H.K., Leiter M., Day A. & Gilin D.

(2009a) Workplace empowerment, incivility, and burnout:

impact on staff nurse recruitment and retention outcomes.

Journal of Nursing Management 17, 302–311.

Spence Laschinger H.K., Wilk P., Cho J. & Greco P. (2009b)

Empowerment, engagement and perceived effectiveness in

nursing work environments: does experience matter? Journal

of Nursing Management 17 (5), 636–646.

Stolee P., Esbaugh J., Aylward S., et al. (2005) Factors

associated with the effectiveness of continuing education in

long-term care. Gerontologist 45, 399–409.

Tomey A.M. (2009) Nursing leadership and management effects

work environments. Journal of Nursing Management 17,

15–25.

Walumbwa F.O., Avolio B.J., Gardner W.L., William L., Wern-

sing T.S. & Peterson S.J. (2008) Authentic leadership: devel-

opment and validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of

Management 34 (1), 89–126.

Wong C.A. & Cummings G.G. (2007) The relationship between

nursing leadership and patient outcomes: a systematic review.

Journal of Nursing Management 15 (5), 508–521.

Wong C.A., Spence Laschinger H.K. & Cummings G.G. (2010)

Authentic leadership and nurses’ voice behaviour and perceptions

of care quality. Journal of Nursing Management 18 (8),

889–900.

Zhang Y. & Wildemuth B.M. (2009) Qualitative Analysis of

Content. In Applications of Social Research Methods to

Questions in Information and Library (B.M. Wildemuth ed),

pp. 308–319. Libraries unlimited, Westport, CT.

ª 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

12 Journal of Nursing Management

A. M. Mork Rokstad et al.