The Role of Inclusive and Exclusive Victim Consciousness in Predicting Intergroup Attitudes:...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of The Role of Inclusive and Exclusive Victim Consciousness in Predicting Intergroup Attitudes:...

The Role of Inclusive and Exclusive Victim Consciousness inPredicting Intergroup Attitudes: Findings from Rwanda,Burundi, and DRC

Johanna Ray VollhardtClark University

Rezarta BilaliNew York University

The present research examined the differential relationship between distinct construals of collectivevictimhood—specifically, inclusive and exclusive victim consciousness—and intergroup attitudes in the contextand aftermath of mass violence. Three surveys in Rwanda (N = 842), Burundi (N = 1,074), and Eastern DRC(N = 1,609) provided empirical support for the hypothesis that while exclusive victim consciousness predictsnegative intergroup attitudes, inclusive victim consciousness is associated with positive, prosocial intergroupattitudes. These findings were significant when controlling for age, gender, urban/rural residence, education,personal victimization, and ingroup superiority. Additionally, exclusive victim consciousness mediated theeffects of ingroup superiority on negative intergroup attitudes. These findings have important theoreticalimplications for research on collective victimhood as well as practical implications for intergroup relations inregions emerging from violent conflict.

KEY WORDS: collective victimhood, victim consciousness, victimization, ingroup superiority, Rwanda, Burundi, DRC

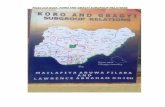

One of many areas in the world that has been plagued by cyclical violence is the Great Lakesregion in Africa. The 1994 genocide in Rwanda, the civil war in Burundi from 1993 to 2005, and theongoing violence in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) are just a few examples ofviolent outbursts in the region since its decolonization. Political scientists and historians have notedthat perceived ingroup victimization is at the core of these violent conflicts. For example, analyzingmass violence in Rwanda, Mamdani (2001) observes:

Ever since the colonial period, the cycle of violence has been fed by a victim psychologyon both sides. Every round of perpetrators has justified the use of violence as the onlyeffective guarantee against being victimized yet again. For the unreconciled victim ofyesterday’s violence, the struggle continues. The continuing tragedy of Rwanda is that eachround of violence gives us yet another set of victims-turned-perpetrators. (pp. 267–68)

Other scholars have noted a similar role of collective victimhood and resulting victim beliefs inneighboring countries, Burundi and (Eastern) DRC (e.g., Lemarchand, 2009). The aim of the present

Political Psychology, Vol. xx, No. xx, 2014doi: 10.1111/pops.12174

bs_bs_banner

10162-895X © 2014 International Society of Political Psychology

Published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc., 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ,and PO Box 378 Carlton South, 3053 Victoria, Australia

studies is to explore the relationship between group-based victim beliefs and intergroup attitudes inthe Great Lakes region in Africa and to examine whether they are inevitably linked to hostility—orwhether different construals of the ingroup’s victimization may predict more positive intergroupattitudes. Thereby, this research contributes to the emerging psychological literature on collectivevictimhood, which has focused primarily on its role in perpetuating violence (for reviews, seeBar-Tal, Chernyak-Hai, Schori, & Gundar, 2009; Noor, Shnabel, Halabi, & Nadler, 2012; Vollhardt,2012).

Collective Victimhood in the Great Lakes Region of Africa

Narratives of collective victimhood in Africa are rooted in European colonization. Colonizers inRwanda and Burundi racialized status differences between Hutus and Tutsis, which many view as thestarting point of power struggles and violence between these groups that culminated in the 1994genocide in Rwanda (Mamdani, 2001). Because borders were arbitrarily drawn by colonizers,cultural ties exist across countries, contributing to spillovers of conflicts (Lemarchand, 2009). BothRwanda and Burundi have a Hutu majority and a Tutsi minority, and Eastern DRC also has Hutu andTutsi populations, alongside other ethnic groups. In Burundi, Tutsis remained in power, while inRwanda, Hutus took over power in the 1959 uprising. This resulted in Tutsi immigration to the easternprovinces of the DRC and in violence against Hutus in Burundi, including a mass killing in 1972 thatLemarchand (2009) calls a “partial genocide.” The massacres “had a pervasive presence in thehistorical memory of a great many Hutu throughout the entire region” (Lemarchand, 2009, p. 139).In 1993, a civil war began in Burundi when the first Hutu president, Ndadaye, was assassinated. Hutuskilled Tutsis in revenge, followed by a violent repression through the Tutsi military that caused Hutusto flee to neighboring countries. This fed into anti-Tutsi sentiments in Rwanda that preceded thegenocide. In the aftermath of the genocide, the Tutsi-led Rwandan army (RPF) invaded DRC underthe pretense that Hutu genocidaires were attacking Rwanda from there. This started what Prunier(2009) refers to as “Africa’s World War.” Although this war officially ended in 2002, the violencecontinues in the eastern part of the country through rebel groups, large-scale rape, displacement ofcivilians, extortion, and other human rights abuses (Human Rights Watch, 2012).

As this brief summary indicates, civilians on all sides have suffered. In addition to collectivememories of historical massacres, all three countries have undergone recent wars (Rwanda: 1990–93; Burundi: 1993–2005; DRC: 1998–2002) that severely affected all civilians regardless of ethnic-ity. Retributive violence, following most massacres, is often silenced in official narratives(Lemarchand, 2009). Likewise, the victimization of some Hutus during the 1994 genocide inRwanda or the 1972 massacres in Burundi is not sufficiently acknowledged. These one-sidedmemories and the silencing of groups’ experiences can increase grievances and hinder reconciliation(e.g., King, 2010). Overall, a sense of collective victimhood exists among most ethnic groups in theregion and has contributed to what is perceived as legitimate defensive or preemptive violence(Bilali, Tropp, & Dasgupta, 2012).

Psychological Research on Collective Victimhood and Intergroup Relations

Political and social psychologists have only recently begun to explore beliefs regarding collec-tive victimhood—referred to as group-based victim consciousness (Vollhardt, 2012)—and its impacton intergroup relations. Most of this research has focused on its detrimental consequences (Bar-Talet al., 2009; Noor et al., 2012; Vollhardt, 2009a, 2012).

Early work on collective victimhood examined siege mentality, capturing the belief that the restof the world has negative intentions toward the ingroup (Bar-Tal & Antebi, 1992). This belief

Vollhardt and Bilali2

correlated with hawkishness among Jewish Israelis (Bar-Tal & Antebi, 1992) and predicted higherlevels of anti-Semitism among Polish students (Golec de Zavala & Cichocka, 2012). In a recentnationwide representative sample of Jewish Israelis, siege mentality (along with perceived victim-hood in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict) predicted less openness to new information about the conflictand less willingness to compromise (Halperin & Bar-Tal, 2011).

Another construct that has stimulated research on these issues is competitive victimhood,defined as a group’s claim that it has suffered more than the other group in a conflict (Noor et al.,2012). Competitive victimhood predicted less intergroup trust and forgiveness in postconflict settingsin Northern Ireland and Chile (Noor, Brown, Gonzalez, Manzi, & Lewis, 2008; Noor, Brown, &Prentice, 2008), and among Bosnian Serbs, it predicted less willingness to acknowledge ingroupharm doing during the war (Cehajic & Brown, 2010).

Finally, experimental research showed that reminding Canadian Jews of Jewish victimizationduring the Holocaust reduced collective guilt about present-day harm doing against Palestinians inthe Israeli-Palestinian conflict (Wohl & Branscombe, 2008). These findings were replicated amongAmericans reminded of 9/11 and Pearl Harbor, affecting collective guilt about harm doing in the warin Iraq.

Exclusive versus inclusive victim consciousness. While the studies summarized above addresssomewhat different aspects of collective victimhood, they all focus on the ingroup’s victimizationand imply a sense that this suffering is unique. To capture the perceived distinctiveness of ingroupvictimization that is shared across these constructs, we use the term “exclusive victim conscious-ness” (Bilali & Vollhardt, 2013; Vollhardt, 2009a, 2012). This overarching umbrella term refers todifferent ways in which collective victimhood can be construed as setting the ingroup apart fromother groups—for example, by competing with the other group in a conflict over the victim status,by pointing to the unique ways in which the ingroup has suffered in world history, or by referring tothe severity or ongoing nature of the ingroup’s victimization, without engaging in explicit compari-sons with other groups. Thus, exclusive victim consciousness can be conflict-specific, referring toperceived distinctiveness of ingroup suffering in comparison to the adversary’s experiences (e.g.,competitive victimhood), or global, referring to perceived uniqueness of the ingroup’s suffering ingeneral, without specifying a reference group (e.g., siege mentality; see Vollhardt, 2012). Exclusivevictimhood may be invoked by group members and leaders because it can have practical andpsychological advantages for the ingroup, such as maintaining a positive moral image (Shnabel,Halabi, & Noor, 2013) and being entitled to reparations or aid (Noor et al., 2012).

However, despite the literature’s focus on exclusive victimhood, ingroup victimization also canbe construed in more inclusive ways. Specifically, people may acknowledge that other groups alsohave been victimized and even perceive their suffering to be similar to the ingroup’s experiences. Werefer to this as “inclusive victim consciousness” (Vollhardt, 2009a, 2012; see also Noor et al., 2012;Shnabel et al., 2013). Inclusive victim consciousness may arise, for instance, through intergroupcontact (e.g., Andrighetto, Mari, Volpato, & Behluli, 2012), when people hear stories about others’suffering that resemble their ingroup’s experiences. For example, the “Parents’ Circle: BereavedFamilies for Peace” consists of Palestinian and Israeli parents who have lost a child in the conflictand speak out for peace from the perspective of shared grief (Landau, 2009). Such conflict-specificforms of inclusive victim consciousness are presumably much more psychologically challenging andrare than perceiving similarities with other victim groups around the world who were not involvedin the same conflict (i.e., global inclusive victim consciousness; Vollhardt, 2012; see also Klar,Schori-Eyal, & Klar, 2013). For example, a play about the Cambodian genocide that was performedby Rwandan and Cambodian actors together in Rwanda made the Rwandan audience reflect onsimilarities between the two genocides (Breaking the Silence, n.d.). Staub, Pearlman, Gubin, andHagengimana (2005) suggest that such awareness of commonalities with violence in other contextscan serve to reaffirm the victim group’s humanity and contribute to healing and reconciliation.

Victim Consciousness in Rwanda, Burundi, and DRC 3

Importantly, perceiving similarities and differences between the ingroup’s victimization andother groups’ fate is not necessarily mutually exclusive. It is possible to perceive similarities anddifferences simultaneously and to different degrees—for example, one may agree that two groupshave suffered during a conflict but recognize differences regarding the exact nature or extent ofvictimization. Similar to this rationale, the literature on superordinate identities shows more gener-ally that people can identify with a shared, superordinate category but also prefer subgroup identitiesto be acknowledged (Crisp, Stone, & Hall, 2006; Dovidio, Gaertner, & Saguy, 2009; Hornsey &Hogg, 2000). Similarly, acknowledging distinct aspects of the ingroup’s victimization may beimportant in order to avoid backlash, especially when inclusive construals are imposed in experi-mental studies or interventions (Vollhardt, 2013).

Consequences of inclusive victim consciousness for intergroup relations. Based on the effectsof perceived similarities and superordinate identities on positive, prosocial outgroup attitudes (e.g.,Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000; Levine, Prosser, Evans, & Reicher, 2005), we expect inclusive victimconsciousness to predict positive attitudes toward other victimized groups (Vollhardt, 2009a, 2012).In line with this hypothesis, an experimental study among Jewish Americans showed that when theHolocaust was described in inclusive, universal ways (while also acknowledging the ingroup’sdistinct fate), willingness to support victims in Darfur increased (Vollhardt, 2013). Similarly, Klaret al. (2013) reported several examples from the Jewish-Israeli context that illustrate how perceivedsimilarities between the Holocaust and other genocides have motivated aid for some victim groupsand how the lessons people draw from the Holocaust can include to not harm others, even adver-saries. Additionally, acknowledgment of other groups’ suffering implies and presumably requires acertain degree of universalism (Schwartz, 2007) as well as empathy towards and perspective takingwith other groups (e.g., Galinsky, Ku, & Wang, 2005; Noor et al., 2008; Noor, Brown, & Prentice,2008), all of which can promote positive intergroup outcomes.

Based on these considerations and the research reviewed above on exclusive construals ofingroup victimization and negative intergroup attitudes, we argue that inclusive and exclusive victimconsciousness will predict divergent outcomes. The idea that inclusive and exclusive victim con-sciousness could be distinct, rather than opposite ends of a unidimensional scale, predicting differentoutcomes, parallels patterns observed in other research on intergroup attitudes (Pittinsky, Rosenthal,& Montoya, 2011). These authors demonstrated that positive attitudes toward minority groups werea better predictor of positive outcomes (e.g., speaking out on behalf of these minorities), whilenegative attitudes were a better predictor of negative outcomes (e.g., supporting policies restrictingAffirmative Action). Such “functional independence” of seemingly related attitudes has also beendocumented more generally by Cacioppo and Berntson (1994), who showed that negative andpositive attitudes toward an object are often not opposite ends of bipolar scales; assessing themindependently improves our measurement and understanding of these attitudes, their distinct ante-cedents, and consequences (e.g., approach versus withdrawal responses). Similarly, several factoranalyses of data from preliminary studies on victim consciousness in different settings showed thatinclusive and exclusive victim consciousness load on separate factors and predict different outcomes(Vollhardt, 2010). While there is promising anecdotal and initial empirical evidence of these phe-nomena, however, no published research to date has shown the different consequences of thesetwo distinct types of victim consciousness—conflict-specific inclusive and exclusive victimconsciousness—when measured jointly to predict a range of positive and negative intergroupoutcomes.

The role of personal victimization. An important question to consider in this context is whetherpersonal experiences of victimization during a conflict affect intergroup relations. Some studiesshow that conflict-related personal victimization predicts less outgroup tolerance (Canetti-Nisim,Halperin, Sharvit, & Hobfoll, 2009), decreased forgiveness (Myers, Hewstone, & Cairns, 2009), andless support for legal responses to human rights violations (Elcheroth, 2006). However, these

Vollhardt and Bilali4

responses depend on other factors such as the level of violence in the community and the individual’sideological orientation (Elcheroth, 2006; Sharvit, Bar-Tal, Raviv, Raviv, & Gurevich, 2010). More-over, under some circumstances personal victimization may even motivate prosocial attitudes—depending on the specific meaning individuals attach to these experiences (Klar et al., 2013;Vollhardt, 2009b). Finally, the meaning derived from individual and collective victimization in thecontext of a conflict is often distinct, as are its consequences (Elcheroth, 2006; Ferguson, Burgess,& Hollywood, 2010). Therefore, we hypothesized that personal victimization and group-basedvictim consciousness would predict intergroup outcomes independently. We did not have predictionsabout the direction of potential effects of personal victimization on intergroup relations.

The role of ingroup superiority. Ingroup superiority (a facet of ingroup glorification: Roccas,Klar, & Liviatan, 2006; Roccas, Sagiv, Schwartz, Halevy, & Eidelson, 2008) is a specific form ofingroup identification that is particularly relevant to exclusive victim consciousness. First, ingroupsuperiority is a better predictor of negative intergroup outcomes (e.g., outgroup derogation, legiti-mization of violence) than other forms of ingroup identification such as ingroup attachment (Leidner,Castano, Zaiser, & Giner-Sorolla, 2010; Roccas et al. 2006, 2008). Moreover, ingroup superiority,just like exclusive victim consciousness and competitive victimhood, also has an “explicit compara-tive aspect” (Roccas et al., 2008, p. 297; see also Noor et al., 2012). Therefore, if inclusive andexclusive victim consciousness remain significant predictors of intergroup outcomes when control-ling for ingroup superiority, we can have more confidence that these relationships cannot merely beexplained by a general tendency to engage in intergroup comparisons. Furthermore, because ingroupsuperiority is concerned with preserving a positive image of the ingroup (e.g., Roccas et al., 2008),group members who generally perceive the ingroup as superior are presumably motivated to bolsterthe ingroup’s positive image by maintaining its moral high ground in the conflict. Thus, people whoreport high levels of ingroup superiority should be more likely to emphasize the uniqueness of theingroup’s victimization and express competitive victimhood because this may provide a positivemoral image. Consequently, we hypothesized that ingroup superiority would predict exclusive victimconsciousness, which in turn should mediate the relationship between ingroup superiority andnegative intergroup attitudes.

Overview of the Present Research

We used data from surveys conducted in Rwanda, Burundi, and Eastern DRC to test thismediation hypothesis and our main hypothesis that conflict-specific exclusive victim consciousness(focusing on competitive victimhood as one possible, exclusive construal of ingroup victimization)would predict negative intergroup attitudes, while conflict-specific inclusive victim consciousnesswould predict positive intergroup attitudes. The surveys were conducted in late 2010 and early 2011(Burundi: November 2010; Rwanda: December 2010; DRC: February–March 2011) as part of alarger study on media and conflict that is reported elsewhere (Bilali & Vollhardt, 2013). Only itemspertaining to intergroup and conflict-related attitudes were selected for the analysis.

The present studies are the first to examine conflict-specific inclusive and exclusive victimconsciousness simultaneously, looking at a range of constructive and destructive intergroup out-comes in the underresearched context of East Africa. We tested our hypotheses in three distinctnational settings marked by different conflict stages. Rwanda currently endorses strong unity andreconciliation policies (Straus & Waldorf, 2011), which emphasize commonalities between groupsand make it socially desirable to express positive intergroup attitudes. Burundi is also a postconflictsociety, but it lacks such reconciliation policies. In contrast to these two postconflict settings, theeastern provinces in the DRC are experiencing ongoing violence and lack of security, which candeteriorate intergroup relations (e.g., Canetti-Nisim et al., 2009; Sharvit et al., 2010). While theconflict in DRC cannot be clearly framed in ethnic terms as in Rwanda and Burundi (in part because

Victim Consciousness in Rwanda, Burundi, and DRC 5

there are approximately 250 ethnic groups), manipulation of ethnic tensions by leaders are anessential part of it (Autesserre, 2010). Overall, testing the hypotheses in such diverse settingsincreases the ability to generalize the findings beyond one particular national context or conflictstage.

Method

Samples

Rwanda. This sample included 842 Rwandans (53% female) from various regions in all parts ofthe country. Nearly half of the sample (47.6%) was recruited in rural areas. Participants’ age rangedfrom 16 to 70 (M = 30.06, SD = 10.4). Some participants (4.4% of the sample) did not have anyformal education; 12.7% had attended three years of school; 37.5% had six years of schooling;38.6% had some secondary education; and 4.4% had completed higher education. Information aboutparticipants’ ethnicity was not collected because it is illegal in Rwanda to refer to ethnic labels(Straus & Waldorf, 2011).

Burundi. This sample included 1074 Burundians (50.5% female) from various regions in allparts of the country. The majority of the sample (65%) lived in rural settings. Participants’ age rangedfrom 16 to 85 (M = 32.18, SD = 12.83). Almost one-fifth (16.9%) of the sample had no formaleducation; 41% had completed elementary school; 36% had completed some middle or high school;and 5.3% had an advanced degree. Because of the country’s history of group-based mass violence,asking about a person’s ethnicity is very sensitive. Therefore, to avoid upsetting participants ormaking them suspicious about the goals of the study, we did not assess ethnicity.

DRC. The sample included 1,609 participants (51.2% female) from North and South Kivu inEastern DRC. The majority of the sample (60.4%) lived in rural areas. Participants’ age ranged from16 to 73 (M = 31.32, SD = 11.93). A small percentage (5.7%) of the sample did not have any formaleducation; 14.5% had attended elementary school; 62.5% had completed at least some high school;14.6% had a high school degree; and 2.3% had attended university. Thirty different ethnic groupswere represented in the sample, the largest group being the Shi (41.2%), Hunde (12.9%), and Nande(10.7%).

Procedure

We followed the same procedure in all three countries, using an audio-delivered survey tech-nique developed by Chauchard (2013) to reduce socially desirable responses among populationswith low literacy rates. Recorded survey items are played on portable CD players over headphones,and participants mark their responses on pictorial scales (see also Bilali & Vollhardt, 2013). Localresearch assistants recruited participants in public spaces such as markets. Surveys were completedin privacy. Each item was read twice, and participants had 15 seconds to respond. They were able torepeat or stop the recording when needed. After completion of the audio-based survey, researcherscollected demographic information in face-to-face interviews.

The surveys were administered in the local languages: Kinyarwanda in Rwanda, Kirundi inBurundi, and Swahili in DRC. Items had been translated and back-translated from English byprofessional translators, and local researchers assisted to ensure the meaning of items was preserved.

Measures

All items were assessed on 4-point pictorial scales with the following scale points: big thumbdown (strongly disagree), small thumb down (slightly disagree), small thumb up (slightly agree), andbig thumb up (strongly agree) (see Bilali & Vollhardt, 2013; Chauchard, 2013).

Vollhardt and Bilali6

Predictors. Single-item measures adapted from previous research (Vollhardt, 2010) assessedinclusive victim consciousness (“The victimization other groups in Rwanda [Burundi/DRC] haveexperienced is similar to what my group has experienced”) and exclusive victim consciousness(focusing specifically on competitive victimhood: “No other group in Rwanda [Burundi/DRC] hassuffered the same way my group has”).

Ingroup superiority was assessed in Burundi and DRC (but not in Rwanda because referencesto ethnicity are illegal) with one item adapted from Roccas et al. (2008): “My ethnic group is betterthan other groups.”

Outcome variables. We assessed outcomes that have been identified as important aspects ofintergroup relations in the examined contexts. Negative, conflict-exacerbating attitudes includedmeasures of social distance (e.g., Paluck, 2009), political or economic exclusion (e.g., Lemarchand,2009), intergroup mistrust (e.g., Paluck, 2009), and intolerance (e.g., Paluck, 2010). Positive,prosocial attitudes included measures of political inclusion (e.g., Lemarchand, 2009) and activebystandership, defined as the willingness to intervene on behalf of others (Staub, 2011). All items arelisted in Table 1.

Table 1. Overview of All Items Used as Outcome Variables, with Descriptive Statistics

Rwanda Burundi DRCM (SD) M (SD) M (SD)

Negative Intergroup OutcomesSocial distanceI advise my children (or the ones I will have in the future) that they

should only marry people from the same regional, religious, or ethnicgroup as our own. (Soc. Dist. 1) (from Paluck, 2009)

1.69 (1.00) 1.89 (1.18) 1.87 (1.11)

I would prefer not to have members from the other ethnic group ascolleagues or neighbors (Soc. Dist. 2)

N/A 1.85 (1.17) N/A

Political and economic exclusionA good leader is someone who has primarily the interests of my ethnic

group in mind (Political Exclusion 1)N/A 2.33 (1.30) 2.09 (1.14)

A good leader is someone who makes sure that my ethnic group will getahead in this country (Political Exclusion2)

N/A 2.30 (1.30) 2.10 (1.12)

Some groups do not deserve access to resources and power in thiscountry. (Economic Exclusion)

1.91 (1.09) N/A N/A

Other negative intergroup attitudesIt is naive to trust members of the other ethnic group. (Mistrust) (from

Paluck, 2009)1.86 (1.07) 2.24 (1.22) N/A

If people from different ethnic or political groups get together to discussthe problems in our community, it will only makes things worse.(Intolerance)

N/A N/A 1.88 (1.08)

Positive Intergroup OutcomesActive bystandershipWhen I see that someone who is not in my group is treated unfairly, I try

to stop this (for example, by getting help or by speaking out againstit). (Active Bystander 1)

2.89 (.65) 3.36 (.99) 2.82 (.90)

It is important to teach children to help all children, even those who aremade fun of by others. (Active Bystander 2)

2.99 (.59) N/A N/A

Political inclusionA good leader is someone who has the interests of all ethnic groups in

mind. (Political Inclusion 1)N/A 3.58 (.82) 2.83 (.82)

A good leader is someone who takes care of all ethnic groups, even thoseI don’t like. (Political Inclusion 2)

N/A 3.38 (.97) 2.89 (.80)

Note. Variable labels used in subsequent regression tables are in brackets after each item.

Victim Consciousness in Rwanda, Burundi, and DRC 7

Notably, the specific items used to assess these constructs vary to some degree across the threesettings because of limited survey space and due to the varying relevance of each item to the specificsetting. Additionally, because the items captured different aspects of the constructs resulting in lowcorrelations (Spearman’s rho = .20–.24),1 as in previous research in this region (Bilali & Vollhardt,2013; Paluck, 2009, 2010) we analyzed them as single-item measures.

Control variables. Several demographic variables were assessed: age, gender, urban versus ruralresidence, and level of education. We also examined personal victimization by asking participants torespond to a checklist of traumatic events (see Table 2). These experiences were combined into a sumscore, creating a measure of cumulative trauma exposure (e.g., Brounéus, 2010).

Results

The zero-order correlations1 revealed that inclusive and exclusive victim consciousness wereeither uncorrelated (Burundi: Spearman’s rho = !.00) or the correlations were very small (Rwanda:rho = .15, DRC: rho = .08). Because the outcome variables were measured on ordinal scales, we usedordinal logit regressions to assess the effects of inclusive and exclusive victim consciousness on eachoutcome, controlling for demographic variables (age, gender, urban/rural residence, education),personal victimization, and for ingroup superiority among the Burundian and Congolese samples.The results are summarized in Tables 3–7. All models were an improvement over the baseline-intercept-only models, as indicated by the significant chi-square statistics.

Overall, the results were consistent and conceptually replicated across all three samples, for alloutcome variables: exclusive victim consciousness (but not inclusive victim consciousness) pre-dicted negative intergroup attitudes, while inclusive victim consciousness (but not exclusive victimconsciousness) predicted positive, prosocial intergroup attitudes. These effects were significantabove and beyond crucial control variables we discuss below.

Outcomes Predicted by Exclusive Victim Consciousness

Social distance. Across all three samples, the more participants believed that no other group intheir country had suffered in the same way as their ingroup had, the more likely they were to reportthat they would urge their children to marry within their own group. Similarly, in the Burundiansample exclusive victim consciousness predicted less willingness to have outgroup neighbors.

1 Correlation tables can be found in the online supplemental materials.

Table 2. Personal Victimization Events Reported by Participants

Rwanda Burundi DRC

Having been physically harmed 25.7% 21.9% 38.5%Threatened 25.8% 28.1% 56.4%Expelled 19.6% 17.3% 37.4%Restrictions in rights of movement 22.1% 17.4% 17%Displacement 14.4% 24.5% 34.1%Destruction of properties 19% 41.2% 41.7%Arbitrary arrests 10.8% 11.7% 29.6%Relatives killed 57.1% 43% 40.1%Relatives harmed 31% 45.3% 36%

Average number of traumatic events reported (M, SD) 2.18 (2.75) 2.45 (2.93) 3.01 (2.54)

Vollhardt and Bilali8

Political and economic exclusion. In Burundi and DRC, people who reported higher levels ofexclusive victim consciousness were also more likely to express support for leaders who primarilyhave the interests of participants’ ethnic group in mind and make sure that their group gets ahead.Similarly, in Rwanda, exclusive victim consciousness predicted more agreement with the idea thatsome groups do not deserve access to resources and power.

Other negative intergroup attitudes. Participants who believed that their group had suffered inunique ways were also more likely to express outgroup mistrust (in Rwanda and Burundi) and a lackof tolerance for diversity (in DRC).

Exclusive victim consciousness did not predict positive, prosocial intergroup attitudes.

Outcomes Predicted by Inclusive Victim Consciousness

Active bystandership. In all three samples, the more participants agreed that other groups in theircountry had suffered in similar ways as the ingroup, the more likely they were to report that theywould try to stop others from treating outgroup members unfairly. Additionally, in Rwanda inclusivevictim consciousness predicted a greater likelihood of agreeing that children should be taught to helpchildren who are marginalized by others.

Political inclusion. In Burundi and in DRC, inclusive victim consciousness also predictedsupport for political leaders who care for all groups and not just for the ingroup, and for leaders whohave all ethnic groups’ interests in mind.

Table 3. Ordinal Regressions Predicting Positive and Negative Intergroup Attitudes in Rwanda

SocialDistance 1

Mistrust EconomicExclusion

ActiveBystander 1

ActiveBystander 2

Beta (SE) p Beta (SE) p Beta (SE) p Beta (SE) p Beta (SE) p

Age !.01 .52 .01 .37 .003 .69 .01 .13 .001 .93(.01) (.01) (.01) (.01) (.01)

Wald .41 .79 .15 2.27 .01Gender .03 .85 .09 .51 !.05 .73 !.12 .51 .09 .64(Male = 1) (.15) (.14) (.14) (.18) (.20)Wald .03 .43 .12 .43 !.22Urban/Rural !.05 .75 !.10 .49 .01 .96 !.31 .09 .13 .51(Urban = 1) (.15) (.14) (.14) (.18) (.20)Wald .10 .47 .003 2.91 .43Education !.38 <.001 !.30 <.001 !.22 <.001 !.02 .75 !.01 .90

(.07) (.06) (.06) (.08) (.09)Wald 31.10 22.84 13.61 .10 .01Pers. Victimization !.09 .003 !.02 .51 !.06 .02 .05 1.93 .06 .09

(.03) (.03) (.03) (.03) (.04)Wald 8.56 .43 5.12 .01 2.84Incl. victim

consciousness.09 .24 .14 .051 !.01 .93 .25 .006 .37 <.001

(.08) (.07) (.07) (.09) (.10)Wald 1.40 3.80 .01 7.63 13.24Excl. victim

consciousness.27 <.001 .26 <.001 .18 .004 .15 .063 .12 .19

(.07) (.06) (.06) (.08) (.09)Wald 15.12 16.76 8.46 3.45 .17Model fit ("2) 61.35 <.001 54.66 <.001 29.34 <.001 23.75 .001 21.07 .004Nagelkerke .09 .08 .04 .04 .04

Note. Education was measured on a 6-point ordinal scale, coded from 1 = no formal education to 6 = advanced secondaryeducation. Significant effects of the main independent variables are bolded.

Victim Consciousness in Rwanda, Burundi, and DRC 9

Inclusive victim consciousness did not predict negative intergroup outcomes, with the exceptionof one item in Burundi: namely, less agreement with the idea that one would prefer not to havemembers of the other ethnic group as colleagues or neighbors. Counter to our hypotheses, it alsopredicted higher intergroup mistrust in Rwanda (a marginally significant effect).

Control Variables

Several of the control variables also predicted the outcomes. Above all, ingroup superiority wasa consistent, strong predictor of all negative intergroup attitudes in Burundi and DRC. Additionally,in Burundi (but not in DRC), ingroup superiority predicted less support for political inclusion of theoutgroup and for speaking out on behalf of outgroups.

Personal victimization was a significant predictor of only two outcomes in Rwanda and two inDRC. These results show that greater experiences of personal victimization predicted less agreementwith negative intergroup attitudes (specifically, social distance and economic exclusion of theoutgroup, in Rwanda) but more agreement with positive intergroup outcomes (specifically, socialinclusion, in DRC). Personal victimization did not predict any outcomes in the Burundian sample.

Education predicted most outcomes across all three samples. Specifically, with increasing levelsof education people were generally less likely to agree with most negative intergroup attitudes and

Table 4. Ordinal Regressions Predicting Negative Intergroup Attitudes in Burundi

SocialDistance 1

SocialDistance 2

Mistrust PoliticalExclusion 1

PoliticalExclusion 2

Beta (SE) p Beta (SE) p Beta (SE) p Beta (SE) p Beta (SE) p

Age !.001 .87 !.004 .44 !.01 .15 !.003 .56 !.001 .77(.01) (.01) (.01) (.01) (.01)

Wald .03 .60 2.03 .34 .08Gender !.10 .43 !.02 .87 !.11 .34 .05 .65 .02 .83(Male = 1) (.13) (.13) (.11) (.12) (.12)Wald .63 .03 .92 .20 .04Urban/Rural !.32 .02 .17 .26 !.23 .08 .49 <.001 .51 <.001(Urban = 1) (.14) (.15) (.13) (.13) (.14)Wald 5.04 1.28 3.00 13.58 14.09Education !.10 .05 !.14 .007 !.08 .10 !.20 <.001 !.15 .002

(.05) (.05) (.05) (.05) (.05)Wald 3.72 7.26 2.73 17.05 10.02Pers. victimization !.02 .34 !.004 .85 !.01 .56 .02 .56 .03 .20

(.02) (.02) (.02) (.02) (.02)Wald .91 .04 .34 .34 1.61Ingroup superiority .56 <.001 .56 <.001 .29 <.001 .31 <.001 .53 <.001

(.06) (.06) (.06) (.06) (.06)Wald 83.49 83.01 25.28 27.59 75.35Incl. victim

consciousness!.04 .51 !.12 .03 !.08 .11 !.02 .65 !.01 .86(.05) (.05) (.05) (.05) (.05)

Wald .44 4.75 2.5 .20 .03Excl. victim

consciousness.42 <.001 .36 <.001 .37 <.001 .19 <.001 .26 <.001

(.06) (.06) (.05) (.05) (.05)Wald 54.05 38.88 47.12 12.89 23.14Model fit ("2) 219.66 <.001 208.36 <.001 117.13 <.001 137.75 <.001 212.07 <.001Nagelkerke .21 .20 .11 .13 .20

Note. Education was measured on a 7-point ordinal scale, coded from 1 = no formal education to 7 = advanced secondaryeducation. Significant effects of the main independent variables are bolded.

Vollhardt and Bilali10

more likely to agree with most positive, prosocial intergroup attitudes. In contrast, age and gender didnot consistently predict the outcome variables (see Tables 3–7), and while urban/rural residencypredicted almost all outcomes in the Burundian sample and one in the Congolese sample, thedirection of these effects was not consistent.

Mediation Analyses

To examine whether exclusive victim consciousness mediated the relationship between ingroupsuperiority and negative intergroup outcomes, we used Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS macro to test theindirect effects of ingroup superiority on intergroup outcomes via inclusive/exclusive victim con-sciousness. Ingroup superiority was entered as the independent variable, exclusive and inclusivevictim consciousness were entered as simultaneous mediators, and demographic variables wereentered as covariates. The direct and the indirect effects are summarized in Table 8. As expected, theindirect effect of ingroup superiority on negative intergroup outcomes through exclusive victimconsciousness was significant for all items in both Burundi and DRC, while there were no significantindirect effects on any of the positive intergroup outcomes. Furthermore, as predicted, inclusivevictim consciousness did not mediate any of the relationships between ingroup superiority andintergroup outcomes.

Table 5. Ordinal Regressions Predicting Positive Intergroup Attitudes in Burundi

Political Inclusion 1 Political Inclusion 2 Active Bystander 1

Beta (SE) p Beta (SE) p Beta (SE) p

Age .01 .16 .002 .63 !.003 .56(.01) (.01) (.01)

Wald 1.99 .23 .29Gender .04 .76 !.25 .05 !.26 .04

(.14) (.13) (.13)Wald .09 3.70 4.10Urban/Rural .79 <.001 .68 <.001 .73 <.001

(.16) (.14) (.14)Wald 24.07 22.00 25.60Education .22 <.001 .09 .07 .08 .11

(.06) (.05) (.05)Wald 14.37 3.34 2.49Pers. victimization .02 .53 .01 .80 .01 .75

(.03) (.02) (.02)Wald .39 .06 .10Ingroup superiority !.29 <.001 !.26 <.001 !.21 .001

(.07) (.06) (.06)Wald 18.71 16.46 10.65Incl. victim consciousness .32 <.001 .22 <.007 .16 .004

(.06) (.05) (.05)Wald 27.34 15.58 8.13Excl. victim consciousness .01 .93 .02 .72 !.06 .31

(.07) (.06) (.06)Wald .01 .13 1.02Model fit ("2) 78.63 <.001 56.81 <.001 54.38 <.001Nagelkerke .09 .06 .06

Note. Education was measured on a 7-point ordinal scale, coded from 1 = no formal education to 7 = advanced secondaryeducation. Significant effects of the main independent variables are bolded.

Victim Consciousness in Rwanda, Burundi, and DRC 11

Discussion

The present survey studies, conducted in three different countries in the Great Lakes region ofAfrica, demonstrated that collective victimhood does not inevitably predict negative intergrouprelations. Rather, the outcomes depend on how these experiences are construed. All three surveysprovided support for our hypothesis: While exclusive construals of the ingroup’s victimizationpredicted various negative intergroup attitudes, inclusive victim consciousness predicted positive,prosocial attitudes toward outgroups. These studies are the first to test these hypotheses, assessing avariety of negative and positive outcomes and testing both inclusive and exclusive victim conscious-ness as predictors. Additionally, this is the very first study to test these constructs in the underre-searched Great Lakes region of Africa.

Across three different contexts, we found that inclusive victim consciousness predicted activebystandership on behalf of outgroups and support for leaders who promote the interests of all groups.Conversely, exclusive victim consciousness predicted social distance from outgroups, political andeconomic exclusion of other groups as well as mistrust toward them, and intolerance for diversity. Inone case, inclusive victim consciousness also predicted less negative intergroup attitudes (lowersocial distance), and in another case it marginally predicted more negative attitudes (higher mistrust).However, these two effects were inconsistent and did not occur for any other outcomes. Somefindings were directly replicated, using the same outcome measures across all three contexts (see

Table 6. Ordinal Regressions Predicting Negative Intergroup Attitudes in DRC

Social Distance 1 Intolerance Political Exclusion 1 Political Exclusion 2

Beta (SE) p Beta (SE) p Beta (SE) p Beta (SE) p

Age .01 .04 !.002 .68 !.01 .36 !.00 .79(.004) (.004) (.004) (.004)

Wald 4.17 .17 1.18 .07Gender !.25 .01 !.18 .07 !.10 .29 !.31 .002(Male = 1) (.10) (.10) (.10) (.10)Wald 6.20 3.30 1.11 9.71Urban/Rural .18 .10 .15 .18 !.08 .45 !.23 .03(Urban = 1) (.11) (.11) (.11) (.11)Wald 2.71 1.82 .56 4.82Education !.05 .16 !.15 <.001 !.11 .003 !.08 .03

(.04) (.04) (.04) (.04)Wald 2.01 15.27 9.07 4.76Pers. victimization !.01 .78 .01 .55 .02 .36 !.01 .52

(.02) (.02) (.02) (.02)Wald .08 .35 .85 .41Ingroup superiority .31 <.001 .19 <.001 .36 <.001 .34 <.001

(.04) (.04) (.04) (.04)Wald 51.67 19.97 69.09 62.23Incl. victim consciousness .06 .18 !.04 .32 .06 .23 .06 .16

(.04) (.04) (.04) (.04)Wald 1.76 .97 2.03 1.46Excl. victim consciousness .21 <.001 .17 <.001 .21 <.001 .18 <.001

(.04) (.04) (.04) (.04)Wald 21.76 14.64 24.23 17.29Model fit ("2) 108.28 <.001 69.45 <.001 137.42 <.001 131.41 <.001Nagelkerke .07 .05 .09 .09

Note. Education was measured on an 8-point ordinal scale, coded from 1 = no formal education to 8 = universityeducation. Significant effects of the main independent variables are bolded.

Vollhardt and Bilali12

Table 1). Other outcomes were conceptually replicated using different operationalizations, and newoutcomes were added in individual surveys, thereby increasing the generalizability of the findings.The replication of these findings is particularly noteworthy considering the vast differences betweencontexts—including postconflict settings and ongoing violent conflict, and ranging from a strongstate in Rwanda with a national reconciliation campaign and strict policies about commemoration ofpast violence, to a weak state in DRC without such societal control over victim narratives. Never-theless, future research will need to examine the role of the sociopolitical, cultural, and historicalcontext in shaping construals of collective victimhood, including in-depth studies of the meaning ofvictimhood in each of these distinct contexts.

The present research shows the importance of considering different construals of collectivevictimhood instead of limiting the investigation to exclusive victim beliefs. An important contribu-tion of this research is its suggestion that inclusive and exclusive victim consciousness are indepen-dent, as shown by low or null correlations between these constructs and their differential predictionof outcomes. Thus, future research on collective victimhood and intergroup relations should includemulti-item scales assessing different ways of understanding collective victimhood—not only thosestudied in the present research, but also, for example, different lessons that can be derived from theexperience of group-based victimization (Klar et al., 2013).

Importantly, inclusive and exclusive victim consciousness predicted the outcomes even whencontrolling for important demographic variables such as education, which has been shown to predict

Table 7. Ordinal Regressions Predicting Positive Intergroup Attitudes in DRC

Active Bystander 1 Political Inclusion 1 Political Inclusion 2

Beta (SE) p Beta (SE) p Beta (SE) p

Age .001 .85 !.01 .13 !.004 .38(.004) (.01) (.01)

Wald .03 2.25 .78Gender .08 .41 .02 .86 .08 .47(Male = 1) (.10) (.11) (.11)Wald .68 .03 .51Urban/Rural .15 .17 .03 .82 .10 .41(Urban = 1) (.11) .12 (.12)Wald 1.84 .05 .67Education .11 .003 .04 .33 .11 .01

(.04) (.04) (.04)Wald 8.85 .93 7.62Pers. victimization .03 .14 .06 .01 .05 .04

(.02) (.02) (.02)Wald 2.16 6.66 4.37Ingroup superiority !.02 .65 .02 .65 !.07 .17

(.05) (.05) (.05)Wald .21 .20 1.85Incl. victim consciousness .19 <.001 .11 .02 .19 <.001

(.04) (.05) (.05)Wald 17.38 5.22 16.68Excl. victim consciousness !.03 .42 !.03 .61 !.03 .49

(.05) (.05) (.05)Wald .51 .25 .49Model fit ("2) 38.52 <.001 15.94 .04 39.96 <.001Nagelkerke .03 .01 .03

Note. Education was measured on an 8-point ordinal scale, coded from 1 = no formal education to 8 = universityeducation. Significant effects of the main independent variables are bolded.

Victim Consciousness in Rwanda, Burundi, and DRC 13

intergroup attitudes in various contexts (e.g., Coenders & Scheepers, 2003). Additionally, inclusiveand exclusive victim consciousness remained significant predictors above and beyond ingroupsuperiority (Roccas et al., 2008). This finding is crucial, because it shows that the observed rela-tionships are not merely driven by the tendency to glorify the ingroup or engage in intergroupcomparisons. Moreover, the results revealed that the general perception of the ingroup as superiorwas associated with a more exclusive construal of the ingroup’s victimization, which in turn wasrelated to more negative intergroup attitudes. We reasoned that this may be because people whobelieve the ingroup is better than outgroups should also construe the ingroup’s victimization in waysthat preserves this image. Establishing the ingroup as the exclusive victim in the conflict is one wayto maintain a moral image and legitimize violence toward outgroups (Noor et al., 2012; Shnabelet al., 2013; Wohl & Branscombe, 2008). Future research will need to replicate these results in othersettings and with multi-item measures.

Interestingly, in this sample personal victimization predicted only few outcomes, but consis-tently less negative and more prosocial intergroup outcomes. This is in contrast to previous findingswe reviewed, showing negative effects of personal victimization on intergroup attitudes in othercontexts (e.g., Canetti-Nisim et al., 2009; Elcheroth, 2006). However, it is in line with other researchindicating that personal victimization can motivate prosocial attitudes and behaviors (Vollhardt,2009b). Future research should further investigate the impact of personal victimization on intergroup

Table 8. Indirect and Direct Effects (Mediation Analysis)

Outcome Direct effects Indirect effects Indirect effects

B (SE) B (SE) 95% CI B (SE) 95% CI

BurundiExclusive Victim

ConsciousnessInclusive Victim

ConsciousnessNegative Intergroup Attitudes

Soc. Dist. 1 .30 (.03)*** .085 (.010) [.055; .112] .00 (.001) [!.002; .003]Social Dist 2 .31 (.03)*** .067 (.014) [.044; .097] .00 (.001) [!.003; .003]Mistrust .17 (.04)*** .081 (.014) [.055; .112] .00 (.002) [!.005; .005]Political Exclusion1 .20 (.04)*** .046 (.014) [.023; .076] .00 (.001) [!.002; .004]Political Exclusion 2 .31 (.04)*** .060 (.014) [.034; .091] .00 (.001) [!.003; .003]

Positive Intergroup AttitudesPolitical Inclusion 1 !.09 (.02)*** !.001 (.010) [!.019; .018] !.00 (.004) [!.009; .007]Political Inclusion 2 !.11 (.03)*** .005 (.010) [!.014; .026] !.00 (.004) [!.007; .007]Active Bystander 1 !.07 (.04) !.006 (.010) [!.026; .014] !.00 (.003) [!.006; .005]

DRCExclusive Victim

ConsciousnessInclusive Victim

ConsciousnessNegative Intergroup Attitudes

Soc. Dist. 1 .18 (.02)*** .019 (.005) [.010; .032] !.00 (.001) [!.004; .001]Political Exclusion 1 .20 (.03)*** .020 (.006) [.013; .035] !.00 (.001) [!.004; .001]Political Exclusion 2 .19 (.02)*** .020 (.005) [.009; .031] !.00 (.001) [!.004; .001]Intolerance .11 (.02)*** .015 (.005) [.006; .026] .00 (.001) [!.004; .002]

Positive Intergroup AttitudesPolitical Inclusion 1 .01 (.02) !.003 (.004) [!.011; .004] !.00 (.001) [!.004; .002]Political Inclusion 2 !.04 (.02)* !.003 (.004) [!.010; .004] !.001 (.002) [!.005; .003]Active Bystander 1 !.02 (.02) !.003 (.004) [!.011; .004] !.001 (.002) [!.005; .003]

Note. Results of the indirect and direct effects analysis are shown when controlling for gender, age, education,victimization, and urban residence. An indirect effect is significant when its confidence interval does not include zero. Thesignificant indirect effects are bolded.CI = confidence interval; ***p < .001; *p < .05

Vollhardt and Bilali14

attitudes and on construals of collective victimhood, focusing in particular on contextual factors thatmay moderate these effects (see Sharvit et al., 2010).

The present findings have important implications not just for social psychological research oncollective victimhood in general, but also more specifically for intergroup relations in the GreatLakes region in Africa. Research on this region seems to suggest an almost inevitable cycle ofviolence arising, at least in part, from a psychology of victimhood (Mamdani, 2001). This creates yetanother narrative of the alleged impossibility of improving the situation in this context (seeAutesserre, 2010). The present research sheds light on a constructive response that may be associatedwith the collective experience of victimhood, thereby suggesting that this cycle is not inevitable.Moreover, the findings have implications for developing and testing strategies for interventions thatmay foster prosocial responses to ingroup victimization.

Several limitations of these studies need to be addressed in future research before definiteconclusions can be drawn. First, these findings are correlational, meaning that their causality anddirectionality is unclear. Moreover, additional control variables should be included, such as otherdimensions of ingroup identification, perspective taking, or a general prosocial orientation. Forpractical reasons, it was not feasible to include more items in the present field studies. This resultedin the use of single-item measures—another obvious limitation of these studies that, while notuncommon in research in these regions (e.g., Paluck, 2009, 2010), should be improved in futureresearch. Finally, a crucial limitation is that we were not able to assess or account for ethnic groupmembership in any of the studies: in Rwanda because it is illegal, in Burundi because it is a sensitivequestion, and in DRC because there are too many ethnic groups to include them in the analysis.Future research will need to tackle this issue. Despite the fact that all groups in this region havesuffered and the questions therefore apply to members of all groups, group differences are obviouslyimportant and may moderate these effects (for example, due to power differences and the differentstatus of acknowledgment of the ingroup’s victimization: Noor et al., 2012; Vollhardt, 2012).Similarly, because DRC is a multiethnic society with over 250 ethnic groups, we cannot know whichgroups Congolese participants had in mind when responding to the items. Therefore, some partici-pants may have thought selectively about only some ethnic outgroups as having experienced similarvictimization while perceiving sharp differences regarding the experiences of other groups, such asthe perceived enemy group. Such “selective inclusive victim consciousness” and its consequencesfor relations with the adversary in a conflict should be explored more in future research.

Another important issue that needs more investigation concerns the possible antecedents ofinclusive versus exclusive construals of the ingroup’s victimization. Although we found that ingroupsuperiority predicted exclusive victim consciousness, future research should examine predictors ofboth construals, which may include intergroup contact and perceptions of a common identity(Andrighetto et al., 2012; Shnabel et al., 2013) as well as exposure to outgroup victim narratives inthe case of inclusive victim consciousness (Klar et al., 2013; Vollhardt, 2012) and ingroup-focusedmotives to reduce guilt, improve the group’s moral image, or gain access to compensation in the caseof exclusive victim consciousness (e.g., Noor et al., 2012; Shnabel et al., 2013; Wohl & Branscombe,2008).

Despite the need for a lot more research on this topic, the findings suggest that these ideas mayeventually prove useful for interventions. For example, media and encounter groups could dissemi-nate other groups’ victim narratives, fostering perceived similarities. However, in order to avoidbacklash, it is crucial to acknowledge both similarities and differences in the groups’ experiences(Vollhardt, 2013) and to take other steps to reduce reactance that may arise when confronted with theother side’s narratives (Bilali & Vollhardt, 2013). Creating a common identity based on similarexperiences of victimization (Shnabel et al., 2013) might also avoid the pitfalls of appealing tocommon humanity, which on the one hand improves intergroup attitudes but on the other hand mayalso reduce the desire for social change (Greenaway, Quinn, & Louis, 2011). By keeping ingroup

Victim Consciousness in Rwanda, Burundi, and DRC 15

grievances salient, inclusive victim consciousness interventions may allow for both positive out-comes to occur, as suggested by the correlational findings of the present studies. This, however,remains to be tested in future experimental research.

In sum, these findings provide promising evidence of a novel and understudied phenomenon,inclusive victim consciousness, which has the potential to inform efforts aimed at promoting positiveintergroup relations in the aftermath of mass violence and intergroup conflict. Perhaps equallyimportant, this research also provides a more differentiated view of the nature of collective victim-hood, showing that cycles of violence are not inevitable and that correlates of collective victimhooddepend on the specific construal and meaning derived from these experiences (see also Klar et al.,2013). Thus, including a broader range of questions in research about collective victimhood mayprovide a more hopeful picture than the one painted so far.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Radio La Benevolencija Humanitarian Tools Foundation for their logistic andfinancial support, as well as Sara Håkansson, Hélène Helbig de Balzac, and the team of Burundian,Rwandan, and Congolese research assistants who collected the data. Correspondence concerning thisarticle should be addressed to Johanna Ray Vollhardt, Department of Psychology, Clark University,950 Main Street, Worcester, MA 01610, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

REFERENCES

Andrighetto, L., Mari, S., Volpato, C., & Behluli, B. (2012). Reducing competitive victimhood in Kosovo: The role ofextended contact and common ingroup identity. Political Psychology, 33, 513–529. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.00887.x

Autesserre, S. (2010). The trouble with the Congo. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Bar-Tal, D., & Antebi, D. (1992). Beliefs about negative intentions of the world: A study of the Israeli siege mentality.Political Psychology, 13, 633–645. doi:10.2307/3791494

Bar-Tal, D., Chernyak-Hai, L., Schori, N., & Gundar, A. (2009). A sense of self-perceived collective victimhood in intractableconflicts. International Review of the Red Cross, 91, 229–258. doi:10.1017/S1816383109990221

Bilali, R., Tropp, L., & Dasgupta, N. (2012). Attributions of responsibility and perceived harm in the aftermath of massviolence. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 18, 21–39. doi:10.1037/a0026671

Bilali, R., & Vollhardt, J. R. (2013). Priming effects of a reconciliation radio drama on historical perspective-taking in theaftermath of mass violence in Rwanda. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49, 144–151. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2012.08.011

Breaking the Silence (n.d.). Retrieved from http://rwanda-cambodia.blogspot.com/

Brounéus, K. (2010). The trauma of truth telling: Effects of witnessing in the Rwandan Gacaca courts on psychological health.Journal of Conflict Resolution, 54, 408–437. doi:10.1177/0022002709360322

Cacioppo, J., & Berntson, G. (1994). Relationship between attitudes and evaluative space: A critical review, with emphasison the separability of positive and negative substrates. Psychological Review, 115, 401–423. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.401

Canetti-Nisim, D., Halperin, E., Sharvit, K., & Hobfoll, S. (2009). A new stress-based model of political extremism: Personalexposure to terrorism, psychological distress, and exclusionist political attitudes. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 53,363–389. doi:10.1177/0022002709333296

Cehajic, S., & Brown, R. (2010). Silencing the past: Effects of intergroup contact on acknowledgment of in-group respon-sibility. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1, 190–196. doi:10.1177/1948550609359088

Chauchard, S. (2013). Using MP3 players in surveys: The impact of a low-tech self-administration mode on reporting ofsensitive attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly, 77, 220–231. doi:10.1093/poq/nfs060

Coenders, M., & Scheepers, P. (2003). The effect of education on nationalism and ethnic exclusionism: An internationalcomparison. Political Psychology, 24, 313–343. doi:10.1111/0162-895X.00330

Crisp, R., Stone, C., & Hall, N. (2006). Recategorization and subgroup identification: Predicting and preventing threats fromcommon ingroups. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 230–243. doi:10.1177/0146167205280908

Vollhardt and Bilali16

Dovidio, J., Gaertner, S., & Saguy, T. (2009). Commonality and the complexity of “we”: Social attitudes and social change.Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13, 3–20. doi:10.1177/1088868308326751

Elcheroth, G. (2006). Individual-level and community-level effects of war trauma on social representations related tohumanitarian law. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 907–930. doi:10.1002/ejsp.330

Ferguson, N., Burgess, M., & Hollywood, I. (2010). Who are the victims? Victimhood experiences in postagreement NorthernIreland. Political Psychology, 31, 857–886. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00791.x

Gaertner, S., & Dovidio, J. (2000). Reducing intergroup bias: The common ingroup identity model. Philadelphia, PA:Psychology Press.

Galinsky, A., Ku, G., & Wang, C. (2005). Perspective-taking and self-other overlap: Fostering social bonds and facilitatingsocial coordination. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 8, 109–124. doi:10.1177/1368430205051060

Golec de Zavala, A., & Cichocka, A. (2012). Collective narcissism and anti-Semitism in Poland. Group Processes andIntergroup Relations, 15, 213–229. doi:10.1177/1368430211420891

Greenaway, K., Quinn, E., & Louis, W. (2011). Appealing to common humanity increases forgiveness but reduces collectiveaction among victims of historical atrocities. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 569–573. doi:10.1002/ejsp.802

Halperin, E., & Bar-Tal, D. (2011). Socio-psychological barriers to peace making: An empirical examination within the IsraeliJewish society. Journal of Peace Research, 48, 637–651. doi:10.1177/0022343311412642

Hayes, A. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York, NY: Guilford.

Hornsey, M., & Hogg, M. (2000). Intergroup similarity and subgroup relations: Some implications for assimilation. Person-ality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 948–958. doi:10.1177/01461672002610005

Human Rights Watch (2012). World Report 2012: Democratic Republic of Congo. New York, NY: Human Rights Watch.Retrieved from http://www.hrw.org/world-report-2012/world-report-2012-democratic-republic-congo

King, E. (2010). Memory controversies in post-genocide Rwanda: Implications for peacebuilding. Genocide Studies andPrevention, 5, 293–309. doi:10.1353/gsp.2010.0013

Klar, Y., Schori-Eyal, N., & Klar, Y. (2013). The “Never Again” state of Israel: The emergence of the Holocaust as a corefeature of Israeli identity and its four incongruent voices. Journal of Social Issues, 69, 125–143. doi:10.1111/josi.12007

Landau, Y. (2009). Healing the Holy Land: Interreligious peacebuilding in Israel/Palestine. Washington, DC: United StatesInstitute of Peace.

Leidner, B., Castano, E., Zaiser, E., & Giner-Sorolla, R. (2010). Ingroup glorification, moral disengagement, and justicein the context of collective violence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 1115–1129. doi:10.1177/0146167210376391

Lemarchand, R. (2009). The dynamics of violence in central Africa. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Levine, M., Prosser, A., Evans, D., & Reicher, S. (2005). Identity and emergency intervention: How social group membershipand inclusiveness of group boundaries shape helping behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31,443–453. doi:10.1177/0146167204271651

Mamdani, M. (2001). When victims become killers: Colonialism, nativism, and the genocide in Rwanda. Princeton, NJ:Princeton University Press.

Myers, E., Hewstone, M., & Cairns, E. (2009). Impact of conflict on mental health in Northern Ireland: The mediating roleof intergroup forgiveness and collective guilt. Political Psychology, 30, 269–290. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00691.x

Noor, M., Brown, R., Gonzalez, R., Manzi, J., & Lewis, C. (2008). On positive psychological outcomes: What helps groupswith a history of conflict to forgive and reconcile with each other? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34,819–832. doi:10.1177/0146167208315555

Noor, M., Brown, R., & Prentice, G. (2008). Precursors and mediators of intergroup reconciliation in Northern Ireland: A newmodel. British Journal of Social Psychology, 47, 481–495. doi:10.1348/014466607X238751

Noor, M., Shnabel, N., Halabi, S., & Nadler, A. (2012). When suffering begets suffering: The psychology of competitivevictimhood between adversarial groups in violent conflicts. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16, 351–374.doi:10.1177/1088868312440048

Paluck, E. L. (2009). Reducing intergroup prejudice and conflict using the media: A field experiment in Rwanda. Journal ofPersonality and Social Psychology, 96, 574–587. doi:10.1037/a0011989

Paluck, E. L. (2010). Is it better not to talk? Group polarization, extended contact, and perspective taking in EasternDemocratic Republic of Congo. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 1170–1185. doi:10.1177/0146167210379868

Pittinsky, T., Rosenthal, S., & Montoya, R. (2011). Liking is not the opposite of disliking: The functional separability ofpositive and negative attitudes toward minority groups. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17,134–143. doi:10.1037/a0023806

Victim Consciousness in Rwanda, Burundi, and DRC 17

Prunier, G. (2009). Africa’s world war: Congo, the Rwandan genocide, and the making of a continental catastrophe. NewYork, NY: Oxford University Press.

Roccas, S., Klar, Y., & Liviatan, I. (2006). The paradox of group-based guilt: Modes of national identification, conflictvehemence, and reactions to the in-group’s moral violations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91,698–711. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.698

Roccas, S., Sagiv, L., Schwartz, S., Halevy, N., & Eidelson, R. (2008). Toward a unifying model of identification with groups:Integrating theoretical perspectives. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12, 280–306. doi:10.1177/1088868308319225

Schwartz, S. (2007). Universalism values and the inclusiveness of our moral universe. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology,38, 711–728. doi:10.1177/0022022107308992

Sharvit, K., Bar-Tal, D., Raviv, A., Raviv, A., & Gurevich, R. (2010). Ideological orientation and social context as moderatorsof the effect of terrorism: The case of Israeli-Jewish public opinion regarding peace. European Journal of SocialPsychology, 40, 105–121. doi:10.1002/ejsp.613

Shnabel, N., Halabi, S., & Noor, M. (2013). Overcoming competitive victimhood and facilitating forgiveness throughre-categorization into a common victim or perpetrator identity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 5, 867–877.

Staub, E. (2011). Overcoming evil. Genocide, violent conflict, and terrorism. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Staub, E., Pearlman, L., Gubin, A., & Hagengimana, A. (2005). Healing, reconciliation, forgiving and the prevention ofviolence after genocide or mass killing: An intervention and its experimental evaluation in Rwanda. Journal of Socialand Clinical Psychology, 24, 297–334. doi:10.1521/jscp.24.3.297.65617

Straus, S., & Waldorf, L. (2011). Remaking Rwanda: State building and human rights after mass violence. Madison:University of Wisconsin Press.

Vollhardt, J. R. (2009a). The role of victim beliefs in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: Risk or potential for peace? Peace andConflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 15, 135–159. doi:10.1080/10781910802544373

Vollhardt, J. R. (2009b). Altruism born of suffering and prosocial behavior following adverse life events: A review andconceptualization. Social Justice Research, 22, 53–97. doi:10.1007/s11211-009-0088-1

Vollhardt, J. R. (2010). Victim consciousness and its effects on intergroup relations—a double-edged sword? DissertationAbstracts International, 70.

Vollhardt, J. R. (2012). Collective victimization. In L. Tropp (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of intergroup conflict (pp. 136–157).Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Vollhardt, J. R. (2013). “Crime against humanity” or “crime against Jews”? Acknowledgment in construals of the Holocaustand its importance for intergroup relations. Journal of Social Issues, 69, 144–161. doi:10.1111/josi.12008

Wohl, M., & Branscombe, N. (2008). Remembering historical victimization: Collective guilt for current ingroup transgres-sions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 988–1006. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.6.988

Vollhardt and Bilali18