“The Received Hobbes,” essay in a new edition of Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, Ian Shapiro, ed....

Transcript of “The Received Hobbes,” essay in a new edition of Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, Ian Shapiro, ed....

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

1

The Received Hobbes

By Elisabeth Ellis

Three and a half centuries of commentary have not exhausted the store of insight to be drawn

from Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan. While the standard view that has accumulated over scores of

commentaries continues to offer a satisfactory starting point for understanding the text, a number

of basic interpretive issues remain controversial. Moreover, even hundreds of years after its

initial publication, Leviathan still regularly inspires new modes of understanding the world. In

addition to its fundamental place in the development of modern moral and political philosophy,

Hobbes’s work remains a vital and essential point of reference for research in the human

sciences.

Leviathan’s durability is all the more astonishing when one considers the radically alien

vision of human life on which it is based. While the later British contractarian, John Locke,

remains appealing in part due to the familiarity of his assumptions about human nature, Hobbes

enjoys continued popularity despite the strangeness of his view. In fact, much of the power of

Hobbes’s system derives from its very distance from empirical political reality. Like an

economist who presumes perfect competition in order to examine general relationships between

supply and demand, Hobbes discounts fundamental elements of reality—including especially

political solidarity—in order to investigate the conditions of stability and social cooperation.

Hobbes’s aim is to provide a comprehensive account of political order—at the end of Part

II, he compares Leviathan’s achievement favorably to that of Plato’s Republic—but he begins

with the microfoundations of human psychology in Part I (“Of Man”). As we can see from the

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

2

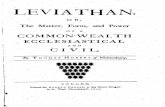

frontispiece of the Head edition, which depicts a gigantic ruler composed of separate, roughly

identical citizens, for Hobbes sovereign political authority will be constructed from its individual

components. Anyone intending to construct such an artificial being as is required for the

effective exercise of political sovereignty, Hobbes argues, must understand the nature of its

human parts. Such knowledge can only be obtained by introspection, but fortunately for

posterity, in Leviathan Hobbes provides an exhaustive account of human motives. “When I shall

have set down my own reading orderly and perspicuously, the pains left another will be only to

consider if he also find not the same in himself. For this kind of doctrine admitteth no other

demonstration.”1

What, then, does Hobbes discover? He begins with a picture of individuals as self-

propelling “engines,” whose senses and motivations may be understood mechanistically: “…life

is but a motion of limbs…. For what is the heart, but a spring; and the nerves, but so many

strings; and the joints, but so many wheels…”2 Of course Hobbesian individuals are not really

all identical to each other; he admits that the objects of people’s passions vary, and that different

passions rule people’s actions differently. However, Hobbes’s mechanistic view provides him

the basic elements out of which his account of justice will be built: human happiness does not

consist in some state of tranquility or in the achievement of any particular goal; rather, since “life

is but motion, and can never be without desire, nor without fear,” felicity is just the continual

satisfaction of a series of desires.3 Hobbesian justice requires no renunciation of this aspect of

human motivation; human beings quite naturally and appropriately try to achieve felicity and

security, and they are equipped with reason to aid them in this pursuit. Having described

1 Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (1651), Introduction, par. 4. References to Leviathan are by

chapter and paragraph number. 2 Ibid., Introduction, par. 1.

3 Ibid., vi, par. 58; see also xi, par. 1.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

3

discrete human beings as rational pursuers of the satisfaction of desires, Hobbes then sets these

individual agents in their social context.

He imagines a group in the “state of nature” (that is, with no common government),

comprised individuals in a condition of natural equality.4 Uncertainty is part of the human

condition in and out of the state of nature: no one can tell exactly what resources will satisfy the

long and unpredictable chain of desires to which all are subject. Hobbes argues, however, that

the inherent difficulties associated with uncertainty are made much worse by a lack of sovereign

authority. Individuals meeting one another in the state of nature have no way of knowing what

each others’ intentions are; the price of mistakenly presuming a fellow human being is

cooperative could be serious loss or even death, while the cost of mistakenly presuming a fellow

human being has murderous intent is the loss of the fruits of momentary cooperation. This

second loss presents no immediate disaster, but over time, the accumulated costs are severe

indeed. The result, as Hobbes memorably remarks, is a world bereft of the advantages of

cooperation: “there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain, and

consequently, no culture of the earth, no navigation, or use of the commodities that may be

imported by sea, no commodious building, no instruments of moving and removing such things

as require much force, no knowledge of the face of the earth, no account of time, no arts, no

letters, no society, and which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the

life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”5

Hobbes describes discrete, rationally motivated individuals as they would encounter each

other in the absence of sovereign judgment: a fatal combination of uncertainty and natural

4 Ibid., xiii, par. 1: “when all is reckoned together the difference between man and man is not so

considerable….For as to the strength of the body, the weakest has strength enough to kill the

strongest, either by secret machinations, or by confederacy…” 5 Ibid., xiii, par. 9.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

4

equality prevents them from enjoying the peace under which they could pursue their several

interests. Their recognition of their own interests in security, then, drive Hobbesian individuals

out of the state of nature and into the commonwealth. Natural conditions of equality and

uncertainty would prevent people from pursuing their rational interests. To overcome those

conditions, rational individuals ought willingly to contract among themselves to relinquish their

individual powers of judgment in favor of a single source of political authority strong enough to

guarantee peaceful cooperation. Thus does Hobbes defend central power as strong as the most

ardent royalist could desire, but authorized not by tradition but by the rational interest of the

subjects themselves.

This technique brings enormous potential gains, but at a substantial price. To become the

great theorist of politics in the service of life, Hobbes must banish political solidarity from his

system. Most political theorists place some value on the practice of politics itself: they celebrate

politics as self-realization, or as an expression of nobility, or as the most glorious human pursuit,

or for some other reason. Not so Hobbes, for whom political activity has only instrumental

value. He does not recognize any inherent value in political participation, not when compared

with its cost, which he believes to be the stability that underlies all the good things in life.6 Even

collective self-defense against a common enemy, one of the most important functions of

government for Hobbes and for political theory generally, is based for Hobbes on calculations of

rational self-interest rather than patriotism. Thus Hobbes’s intricate explanations of exactly

when one is obliged to transfer one’s loyalty to a new sovereign depend on identifying the real

6 I employ the phrase “good things in life” rather than the simpler “good life,” because Hobbes

insists that the word ‘good’ means different things to different people. Hobbes, Leviathan, vi,

par. 6-7.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

5

source of one’s personal security, and not on considerations of membership in any political

group, not even a national one.

One might argue against Hobbes that human beings do value and ought to value

participation in self-rule; Hobbes may be pricing stability too high and political freedom too low.

If we take Hobbes’s assumptions for granted, however, and agree for the sake of argument that

absolute security is the only reliable basis for all the good things in life, we may still find

grounds for disagreement. It is possible that mass political participation may serve life better

than subordination to absolute rule. Hobbes certainly underestimates the value of mutual

political constraint, of what John Adams called checks and balances.7 Even if we accept

Hobbes’s reduction of the scope of politics to security (broadly understood), achieving security

might in fact require much greater public participation that Hobbes anticipates. For example, the

philosopher David Gauthier accepts Hobbes’s basic evaluative, psychological, and

methodological assumptions while criticizing him for overestimating the insecurity associated

with political participation and underestimating the dangers of absolute rule.8

Such questions are open to empirical investigation. It is not in principle impossible that

the Hobbesian system could succeed in securing the good things in life. Moreover, Hobbesian

circumstances may obtain in some contexts and not in others. While there is good reason to

believe that some public accountability is in fact associated with regime stability and with a

reduction in the civil wars that so troubled Hobbes, this correlation does not seem to apply to

7 John Adams, A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America,

against the attack of m. Turgot in his letter to Dr. Price, dated the twenty-second day of March,

1778. A New Edition, vol. 1 (London, 1794) , Preface, A2. 8 David Gauthier, The Logic of Leviathan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969).

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

6

transitional states.9 We do not need the latest political science research, however, to support a

complaint that Hobbes unnecessarily insists on absolutism. George Kateb writes, for example,

that Hobbes “could have learned from Machiavelli, if he did not want to learn from history, that

the institutionalization of tension, dispersed power, enjoined collaboration, and popular

participation could conduce to the avoidance of civil war rather than to its promotion.”10

Already from these brief examples, it should be clear that there is much still to learn from

Leviathan, both interpretively and empirically. One mundane reason that the interpretive debates

over Hobbes’s meaning remain so intense is simply that he wrote a number of different works on

politics, including the Elements of Law (1640), De Cive (1642), the political-historical dialogue

Behemoth (1682), and both the Latin and English editions of Leviathan (1651 and 1688)11

, not to

mention his often very interesting letters and occasional pieces. Even with regard to the English

Leviathan alone, however, fundamental interpretive differences remain.

9 Students of domestic conflict generally rank regime type as the most important, though not the

only, predictor of civil war. Stable democracies, at least those present in data sets available

today, tend to have fewer civil conflicts than autocracies, which in turn have fewer civil conflicts

than transitional regimes. However, compared to other regime types, and holding constant other

factors like minority ethic groups and conflicts over resources, both “coherent democracies” and

“harsh authoritarian” societies are very good at preventing civil conflict. See Håvard Hegre,

“Toward a Democratic Civil Peace? Democracy, Political Change, and Civil War, 1816-1992,”

American Political Science Review 95, no. 1 (2001). 10

George Kateb, “Hobbes and the Irrationality of Politics,” Political Theory 17, no. 3 (1989):

361. 11

Though Hobbes himself wrote both versions, they are not identical, and the differences

between the two texts have been fodder for much interpretive controversy. Even the order in

which they were composed is disputed. For example, Karl Schumann cites Quentin Skinner’s

view that the Latin version is a later revision of the English text, while Edwin Curley cites

François Tricaud’s view that the Latin is mostly an early draft. Schumann, “Leviathan and De

Cive,” in Leviathan after 350 Years, ed. Tom Sorell and Luc Foisneau (Oxford: Clarendon Press,

2004. Edwin Curley, “"Purposes and Features of This Edition",” in Leviathan, with Selected

Variants from the Latin Edition of 1668, ed. Edwin Curley (Indianapolis, Indiana: Hackett,

1994).

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

7

The most important divide among present-day interpreters of Leviathan occurs between

views that emphasize the historical context in which Hobbes was writing, and those that evaluate

his abstract philosophical positions without much reference to the controversies of his day. For

example, the intellectual historian Quentin Skinner emphasizes Hobbes’s immersion in the

tradition of humanist rhetoric that would have been familiar to his contemporaries, though

unfortunately not to most of us today.12

The philosopher Bernard Gert, on the other hand, focuses

on the modern elements in Hobbes that break with tradition, such as his denial of the summum

bonum and his logic of rational choice.13

To some extent, these two views reflect fundamentally

different general assumptions about the conditions of writerly production. A caricature of this

split would have the contextual view argue that history produces ideas, while the abstract

philosophical view would argue that ideas create history (in other words, that the right argument,

rightly disseminated, moves political actors to follow its precepts).14

The two perspectives provide quite different readings of key Hobbesian arguments, as we

shall see from a comparison of historical and philosophical interpretations of Leviathan’s famous

“fool.” Interesting as these exegetical differences are, however, a focus on the differing

12

Quentin Skinner, Reason and Rhetoric in the Philosophy of Hobbes (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1996). 13

Bernard Gert, “Hobbes's Psychology,” in The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes, ed. Tom

Sorell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996). 14

For example, the historian J. G. A. Pocock writes that ideas in political thought should be

treated “strictly as historical phenomena and—since history is about things happening—even as

historical events: as things happening in a context which defines the kind of events they were.”

J. G. A. Pocock, Politics, Language, and Time: Essays on Political Thought and History, 2nd ed.

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), p. 11. Not all historians fall on Pocock’s side of

this divide, however. Jonathan Israel, for example, insists on the primacy of ideas as drivers of

history: “A revolution of fact which demolishes a monarchical courtly world…seems impossible,

or exceedingly implausible, without a prior revolution in ideas….whichever view of the

philosophical ferment one adopts, there is no scope for ignoring the universal conviction during

the revolutionary age…that it was ‘philosophy’ which had demolished the ancien régime…”

Jonathan Israel, Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity 1650-1750

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), pp. 714-715.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

8

interpretations tends to obscure the radical alienness of Hobbes’s general theory for present-day

political thought. Even as many of the contours of today’s political arguments were traced by

Hobbes and his contractarian successors, even as his theories of legitimacy and rationality

undergird the modern version of democracy, still Hobbes’s aspirations are nearly unintelligible

to present-day political theory. An anti-empiricist scientist of politics, an anti-libertarian

individualist, a political realist whose theory presumes the most fundamental transformation of

human nature of any major modern theory of politics: Hobbes confounds the attempt to

characterize his argument in terms of present-day political categories.

I. The Conventional View and its Critics

Both the philosophical and the historical schools of interpretation define themselves against the

kind of routine understanding of Hobbes that can be found in many undergraduate lectures

introducing Leviathan. This conventional view emphasizes Hobbes’s reputation (among his

fans, at least) as the Galileo of political science.15

Hobbes uses system, reason, and materialism

as modern weapons against traditionalist defenses of political authority. These include

justifications of rule according to historical precedent, divine right, convention, custom, or any

other argument that would legitimate subjection by reference to things Hobbes thought illusory

or worse. Before Hobbes can ground modern political authority in rational interest, the

conventional reconstruction says, he must demolish the traditional sources of political

legitimacy.

15

Hobbes hoped to end debate and civil strife and get on with the good things in life (arts and

sciences, commerce, the pleasures of poetry, and so forth). Hobbes’s admirer Sorbière claimed

that Hobbes “like Galileo in physics, put an end to empty quibbling on [the subject of politics].”

Cited in Sharon Lloyd, Ideals and Interests in Hobbes's Leviathan (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1992), p. 311.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

9

Some of his most successful efforts to undermine traditional legitimacy are achieved with

a combination of humor and direct argument. Consider, for example, the last of a long series of

attacks on the authority of the ancients, which comes in the final pages of Leviathan’s Review

and Conclusion. Hobbes lists reasons to ignore the Greek and Roman authorities cited so

frequently by his contemporaries, including that they contradict themselves, that after so many

intervening years we cannot be sure of what the supposed authorities in fact said, that they are

often used in bad faith to cover up weak argument, and that the ancient authorities themselves

did not cite older sources. “Lastly, though I reverence those men of ancient time that either have

written truth perspicuously, or set us in a better way to find it out ourselves, yet to the antiquity

itself I think nothing due. For if we will reverence the age, the present is the oldest. If the

antiquity of the writer, I am not sure that generally they to whom such honor is given were more

ancient when they wrote than I that am writing.”16

But while the conventional view quite rightly emphasizes Hobbes’s use of the weapons

of modern materialist philosophy against traditional forms of political legitimation, it would be a

mistake to conclude that Hobbes’s civil science has much in common with present-day political

science. In Leviathan Hobbes famously combines his geometrical method and his mechanistic

view of human psychology to produce a grandly systematic picture of political obligation. The

conventional view neglects to mention, however, that if the success of Leviathan depended upon

realizing its ambition as this kind of civil science, the book would be a failure. Against modern

social science and in tension with his own achievements in introspection, Hobbes denies that

empirical evidence can tell us anything about political right.17

Generations of students have

16

Hobbes, Leviathan, Rev. and Concl., par. 15. 17

Hobbes’s materialism should be seen as anti-supernatural, rather than experimental. He is an

empiricist insofar as Hobbesian knowledge comes from the sense-data provided by introspection,

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

10

mistakenly criticized Leviathan for presuming that human nature is evil18

; more sophisticated

versions of this criticism have been offered by scholars complaining about Hobbesian

psychological egoism. However, Hobbes is not attempting to produce an explanatory or

predictive theory of human political action. As Alan Ryan argues, Leviathan is not a description

but a “blueprint” for rational political behavior; if it had been an accurate empirical description,

it would have been superfluous.19

The appropriate characterization of Leviathan’s ambition, then, depends on one’s

analytical perspective. Quentin Skinner, for example, emphasizes Leviathan’s status as a work

of civil science, because his Reason and Rhetoric in the Philosophy of Hobbes sees Hobbes’s

text in the context of its Renaissance predecessors. As the vanquisher of traditional political

authority and as the reluctant heir to the rhetorical tradition, the author of Leviathan should be

seen primarily as the constructor of a systematic science of politics. From the forward-looking

perspective of contemporary social science, however, Hobbes’s anti-empiricist “science” is

hardly worthy of the name. If the continuing relevance of Hobbes’s theory of political obligation

depended on the validity of the philosophy of mind articulated in the first chapters of Part I, as

and he is a materialist insofar as for him, the mind is motion in the body. However, present-day

students of political science should be aware of the methodological gap between Hobbes’s civil

science and their own field of endeavor that the two languages of science tend to obscure. See

Gert, “Hobbes's Psychology,” 157ff. and Michael Oakeshott, “Introduction,” in Leviathan, ed.

Michael Oakeshott (Oxford: Blackwell, 1960), p. xxvii. 18

Commentators as different as Michael Oakeshott and David Gauthier have observed that for

Hobbes, political instability does not arise from human moral depravity. Instead, natural

insecurity is the result of the dynamics inherent in the human way of living: in groups of more or

less mutually dependent individuals, made roughly equal by the fact that each could conceivable

kill any; since our groups and their members are naturally characterized by communicative

failure, fallible judgment, and unpredictable expressions of a bewildering variety of passions,

political artifice is required to insure our mutual safety. Oakeshott, “Introduction,” p. liv.

Gauthier, Logic of Leviathan, pp. 17-20. 19

Alan Ryan, “Hobbes's Political Philosophy,” in The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes, ed.

Tom Sorell (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 213.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

11

his geometrical method implies, then Leviathan would by now have become an object of merely

antiquarian interest. The work in fact retains its vitality, because Hobbes’s incisive method of

analysis has outlived the demise of those civil-scientific ambitions that the historians rightly

identify as the culmination of a pre-modern tradition.

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of the conventional view of Leviathan is its emphasis

on the connection between the problem Hobbes is trying to solve and the civil war through which

he was living. It is certainly no accident that Hobbes refers to the death of his friend Sidney

Godolphin twice, at both the very beginning and the very end of the English edition of

Leviathan. In the latter reference, Hobbes employs the example of Godolphin to refute the

charge that he demands too much of the citizens of his ideal state (by expecting them

complacently to transfer their powers of judgment to the sovereign while remaining vigorous in

their private dealings and fierce in military defense of the state). “There is...no such

inconsistence of human nature with civil duties...I have known clearness of judgment and

largeness of fancy, strength of reason and graceful elocution, a courage for the war and a fear for

the laws, and all eminently in one man, and that was my most noble and honoured friend, Mr.

Sidney Godolphin, who, hating no man, nor hated of any, was unfortunately slain in the

beginning of the late civil war, in the public quarrel, by an undiscerned and undiscerning

hand.”20

In the conventional view, Godolphin’s death and the civil war that caused it push

Hobbes toward a theory that prizes peaceful resolution of conflict above all else.

20

Hobbes, Leviathan, Rev. and Concl, par. 4. See the fascinating discussion of this passage in

Skinner, Reason and Rhetoric in the Philosophy of Hobbes, pp. 365-67. For the different

purposes of the present essay, it is worth noting that Godolphin was a poet who was slain in the

civil war. One can read Leviathan as an effort to prevent political strife from depriving people of

the good things in life, which for Hobbes most certainly included poetry.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

12

The philosopher John Rawls describes the “need to settle the problem of order” that

arises from “divisive political conflict” as the first problem of political theory generally.21

From

this perspective, Hobbes’s contribution is his formulation of the classic problem of order in terms

that present-day philosophers call “game-theoretic.” How can rationally self-interested agents

operating under conditions of radical uncertainty about each others’ intentions achieve the level

of cooperation required for mutual security and the pursuit of the good things in life? The

conventional answer to the puzzle is this: Hobbes demonstrates that agents in the state of nature

cannot achieve cooperative security; they must leave the state of nature by submitting to an all-

powerful sovereign whose commonwealth will satisfy the agents’ interests in security against

each other and against common enemies. Thus political obligation for Hobbes springs not from

traditional sources but from individual rational interests in living as long, as safely, and as well

as possible.

As we shall see in the rest of this essay, the conventional view is open to significant

complication. Hobbes does introduce the sovereign in order to make mutual rational cooperation

possible, but beyond that simple point, interpretations diverge. At least one of Hobbes’s aims in

Leviathan is to show individual citizens that their interests lie in the mutual security provided by

the commonwealth.22

The conventional view posits a stark break between the state of nature and

the commonwealth, whose sovereign makes covenants possible (“covenants without the sword

are but words”)23

and whose authority must be absolute. The very name of the book, Leviathan,

21

John Rawls, Justice as Fairness: A Restatement, edited by Erin Kelly (Cambridge, Mass.:

Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001), p. 1. 22

See David Johnston, The Rhetoric of Leviathan (1981), p. 122 and passim. Gauthier agrees

that Hobbes is trying to get people “to change their behavior so that they may succeed in

constructing a well-grounded state.” Gauthier, Logic of Leviathan, p. 20. 23

Hobbes, Leviathan xvii, par. 2.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

13

encourages the reader to think of the sovereign in absolute terms, since Leviathan is the biblical

sea-monster unrestrainable by human power.24

However, none of these aspects of the conventional view has survived critical scrutiny

intact. For example, Hobbes’s explicit case for absolutism seems clearly to fall into an infinite

regress (that is, the sovereign in order to guarantee stability must be absolute, because if the

some other power constrains the sovereign, then stability lies with that further power, which

itself must be absolute in order to guarantee stability, and so on). Modern interpreters agree,

however, that the absolutism called for on the conventional account is not available, and in fact

Hobbes himself frequently writes as if he does not anticipate the exercise of perfect absolute

power.25

The conventional view focuses attention on the conditions under which a self-

interested agent can make a rational decision to leave the state of nature, submit to an absolute

sovereign, and enter the commonwealth. Most of Hobbes’s attention, however, is directed

toward less hypothetical, more intermediate cases, such as the question of exactly when in the

course of a military defeat a citizen ought to transfer his fealty from one sovereign overlord to

another. Hobbes advises the citizen to think about which ruler is the effective guarantor of his

security, making the story of the exit from the state of nature the relevant thought experiment for

the citizen under duress, but not the most relevant case with which to evaluate his theory itself.

As we shall see, even the psychological egoism that forms the conventional view’s

baseline assumption does not stand up under critical examination. Rawls, for example, writes

that Hobbes did not think that it was exactly true, “but he thought it was accurate enough for his

24

“The sword of him that layeth at him [Leviathan] cannot hold: the spear, the dart, nor the

habergeon./ He esteemeth iron as straw, and brass as rotten wood…..Upon earth there is not his

like, who is made without fear./ He beholdeth all high things: he is a king over all the children of

pride.” Bible, King James Version, Job 41. 25

See Jean Hampton, Hobbes and the Social Contract Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1986). See also Gauthier, Logic of Leviathan.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

14

purposes.”26

Kateb puts it more strongly than Rawls when he argues that Hobbes cannot

presume the empirical reality of the “biological instinct of self-preservation. Human history is

the record of people throwing their lives away.”27

Our next task, then, will be to use the

historical and the philosophical perspectives to disturb the conventional view of Hobbes’s

Leviathan.

Leviathan in Context: the Intellectual-Historical Approach

The conventional view provides a useful starting point from which to begin to appreciate

Hobbes’s Leviathan in its full complexity. The first mode of complication to be considered here

is the historical project of setting Leviathan into its intellectual and political contexts. The most

important difference between the conventional and the historical views can be stated quite

simply: though Leviathan indeed represents a radical break with traditional strategies of political

legitimation, there is significant continuity between Leviathan and earlier modes of political

argument. Thus the conventional and the historical views agree that after Hobbes it became

difficult to justify political obligation in terms outside the modern language of consent. What the

historians emphasize and the conventional view ignores, however, is the degree to which there is

a vibrant Renaissance humanist and proto-contractarian tradition out of which Leviathan

emerges.

There is of course a range of historical approaches to Leviathan. At what one might call

the pole of extreme local determinism, there are studies drawing connections between specific

positions taken by Hobbes and short-term changes in the always volatile world of seventeenth-

26

John Rawls, Collected Papers, Edited by Samuel Freeman (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard

University Press, 1999), p. 422. 27

Kateb, “Hobbes and the Irrationality of Politics,” p. 374.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

15

century English politics. Uncertainty about when different texts were written has made the

enterprise more difficult than it would otherwise be, but this need not concern students of the

English version of Leviathan.28

Some local details do turn out to be useful aids in textual

interpretation, however. For example, Hobbes’s well-documented ties to the faction of the royal

court attached to the queen are interesting, given that the queen’s men were more politically and

religiously pragmatic than the group more closely tied to the king. Richard Tuck notes that

Henrietta Maria’s own father (Henry IV of France) made choices that preserved the power of the

monarchy at the expense of the state’s religious establishment. The queen’s pragmatic, Scottish-

sympathizing clique tended to be willing to sacrifice Anglican interests and English pride to the

goal of securing central power. With careful attention to exactly where and when Hobbes wrote

the relevant passages, Tuck places Hobbes’s insistence on the sovereign’s role as chief pastor in

this context.29

Though one might reasonably wonder whether sovereign control of religious life

does not logically follow from Leviathan’s philosophical arguments alone, regardless of the

details of courtly politics, still Tuck’s historical information confirms our text-based inclination

to attribute this position to Hobbes.30

Other details of Hobbes’s life and political involvement provide insight into the moral

and political commitments that Hobbes makes in the text of Leviathan. It is interesting, for

example, that Hobbes personally collected one of the king’s least popular special taxes, echoing

in action his view that citizens are obliged to protect and support the source of their personal

28

Except perhaps insofar as they affect our view of the book’s Review and Conclusion; see note

73. 29

Richard Tuck, Philosophy and Government: 1572-1651 (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 1993),. p. 325. 30

On the conflict between the pro-episcopy, anti-foreign faction of Hyde, and the religiously

opportunistic, Scottish-leaning faction of Buckingham, see Johann Sommerville, “Lofty Science

and Local Politics,” in The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes, ed. Tom Sorell (Cambridge; New

York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), pp. 261ff..

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

16

security. The facts that Leviathan was burned at Oxford and had bills introduced against it in the

House of Commons throw the audacity of its argument into sharp relief.31

Hobbes’s aristocratic

social circle, his royalist obligations and connections, and his ambivalence toward both his

traditional education and the new experimentalism in science: all these details illuminate

Hobbes’s political ideals.32

One should not exaggerate the extent to which historical detail can explain Hobbes’s

philosophical views, however. To take one particularly stark example, Hobbes’s place in a

royalist milieu cannot explain the difficult position he took regarding the Engagement

Controversy. To put it briefly, during Cromwell’s rule, royalist sympathizers were required to

take oaths of loyalty to the new republic. Hobbes argued that citizens living safely under the

wing of a ruler, even one against whom they had fought, owed him obedience. He even

congratulated himself for teaching numerous royalist-leaning resisters their duty to the republic.

No argument from political happenstance or social setting can explain Hobbes’s position, which

offended many in his circle. The position is easily explained with reference to the text, however;

rational agents seeking security should make the covenants that buy them that security without

attention to commitments based on solidarity, glory, or any other passion less reliable than the

desire for self-preservation. Even if in the end we do not need attention to local detail to explain

Hobbes’s position in this case, however, we become aware of its importance thanks to historical

knowledge of the controversy itself. Moreover, attention to Hobbes’s response to the

Engagement Controversy serves as a corrective to the conventional view’s emphasis on

31

See Patricia Springborg, “Hobbes on Religion,” in The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes, ed.

Tom Sorell (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 348. 32

On these points, see Keith Thomas, “The Social Origins of Hobbes's Political Thought”; see

also Sommerville, op. cit., Skinner, op. cit., and Steven Shapin and Simon Schaffer, Leviathan

and the Air Pump (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985).

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

17

Hobbesian sovereignty by institution; as we can see in this instance, sovereignty by acquisition is

at least as interesting and historically far more relevant.

At the other end of the continuum of possible historical approaches to Leviathan is what

one might call the pole of broad intellectual-historical relevance. Unlike views that connect local

details with Hobbesian arguments, this perspective inserts Hobbes into grand theoretical

narratives on subjects of near-universal import. For example, David Johnston, Quentin Skinner,

and others have definitively shown that Hobbes participates with both gusto and equivocation in

the debate comparing eloquence and plain language.33

In Skinner’s controversial interpretation,

Hobbes in Leviathan embraces and contributes to the “Renaissance art of eloquence” that he had

so vehemently rejected in earlier works. According to Skinner, by the time he writes Leviathan,

Hobbes is convinced that “the methods of demonstrative reasoning need to be supplemented by

the moving force of eloquence.”34

To take a different example, Leo Strauss inserts Hobbes near the beginning of a grand

narrative of historical relativism that Strauss claims threatens “decent” societies whose laws are

based on natural right. Hobbes’s role in Strauss’s fairly complex argument is to posit the fear of

violent death as the universal interest grounding political obligation. This line of argument

continues for Strauss through what he calls “historicism” to the relativistic denial of universal

norms as such.35

More interesting for our purposes than any of these ways of understanding Hobbes as part

of a large historical narrative is the argument that Leviathan should be read in the context of the

33

See Skinner, op. cit., Johnston, The Rhetoric of Leviathan, and William Mathie, “Reason and

Rhetoric in Hobbes's Leviathan,” Interpretation 14 (1986). 34

Skinner, p. 5. 35

Leo Strauss, Natural Right and History (1953).

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

18

question of skepticism.36

In the conventional view, skepticism is Hobbes’s rational response to

the problem of order in an irrational world. From the historical point of view, this is true

enough, but Hobbes’s position is characterized more carefully as a response to the theoretical

positions of Hobbes’s contemporaries in the skeptical tradition. Doubt applied to political

judgment motivates Hobbes’s problem of order, on this reading: individuals overestimate their

own power of judgment, and the resulting conflict can only be resolved by transferring the right

to judge controversial matters to a designated authority. The state of nature from this perspective

is the product of fallible judgers failing to adopt appropriately fallibilistic attitudes towards

themselves. As Tuck writes, “Hobbes’s men find peace and security by denying themselves

individual judgement: by subordinating their own wills, desires and beliefs to those of their

sovereign, not because the sovereign knows better, but because the disciplining of an individual

psychology is necessary for one’s well-being...”37

Thus far we have seen the conventional view of Leviathan made more complicated with

the addition of historical insight into the controversies of Hobbes’s day. Tuck argues that the

historical and philosophical views are mutually exclusive. For the philosophers, Hobbes’s

Leviathan seeks to reconcile conflicting individual political interests. In Tuck’s historical

alternative, however, Hobbes is concerned not with reconciling individual interests but with

overcoming the clash of beliefs that threatens the peace of the commonwealth. In its broad

outlines Tuck’s characterization of the historians as interested in the clash of beliefs while the

36

Tuck, Philosophy and Government, p. 279 and passim.; Richard Flathman, Thomas Hobbes:

Skepticism, Individuality, and Chastened Politics, Modernity and Political Thought (Newberry

Park: Sage, 1993); Oakeshott, “Introduction.” 37

Tuck, Philosophy and Government, p. 346.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

19

philosophers are interested in the conflict of interests has merit;38

it remains to be seen, however,

whether the views represent exclusive alternative readings of Leviathan.

The Logic of Social Contract: the Philosophical Approach

Since the historical view focused more on competition among doctrines than among individual

political agents, it should not surprise us that challenges to the conventional wisdom about

psychological egoism emerged not from historians’ but from philosophers’ pens. At its simplest,

the presumption of psychological egoism holds that for Hobbes, agents actually are always

motivated by narrow considerations of self-interest, and primarily by fear of violent death. If

Hobbes did hold such a view, the generations of critics who have complained about its being

empirically invalid would have a strong case to make against Leviathan. As it happens,

however, Hobbes’s view is considerably more complicated and also more plausible than simple

psychological egoism.

As Bernard Gert reminds us, there are plenty of places in the text where Hobbes makes it

clear that his position is more nuanced than psychological egoism. Gert cites the darkly funny

story Hobbes recounts in chapter 8, in which a Greek magistrate is said to have been faced with

an epidemic of suicide by hanging among the girls of the town. Nothing was able to be done

about the madness while people presumed it was the devil’s work. But once someone suggested

that contempt of life was driving the suicides, and that they might retain respect for their own

honor if not for their lives, a new strategy was attempted. As soon as it became known that the

magistrate would “strip such as so hanged themselves, and let them hang out naked,” the

38

Richard Tuck, “Hobbes's Moral Philosophy,” in The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes, ed.

Tom Sorell (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 185.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

20

madness was cured.39

Of course the girls in this story do not exhibit psychological egoism with

regard to self-preservation, but, even more interesting, they demonstrate that concern for social

reputation can trump even a strongly held perceived interest.

The main differences between psychological egoism and the position that philosophers

today generally agree that Hobbes holds are two. First, the portrait of human psychology that

Hobbes derives by reasoning from the results of introspection is one in which the dominant

passion is indeed the passion for self-preservation, but the unpredictable welter of other passions

combines with fallible judgment to produce agents whose actions cannot be described as

psychologically egoistic. Where the conventional view sees a stark picture of zero-sum

competition among insatiably self-interested individuals, present-day philosophers note that the

ruthless behavior of agents in the state of nature is as much a product of their uncertain

environment as of their personal psychologies. Hobbes’s famous remark on the “restless seeking

for power after power, ceasing only in death,” for example, is not an indictment of human

character but a description of the natural response to uncertain conditions. Gert writes that

“Hobbes’s disturbing statement about power is only a claim that all people tend to be concerned

about their future; it explains pension funds and medical checkups more than it does anti-social

power grabs...”40

Even if we are unwilling to go as far as Gert in revising the standard story of

psychological egoism, we can see that, as a description of actual people’s behavior, egoism

describes not what everyone exhibits, but a sort of least common denominator of human

behavior.

The second main revision of the conventional view of Hobbesian psychology is that

Hobbesian rational self-interest describes an ideal, not an actual state of affairs. As Tuck puts it,

39

Gert, “Hobbes's Psychology,” p. 165. Hobbes, Leviathan viii, par. 25. 40

Gert, “Hobbes's Psychology,” p. 168.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

21

Hobbes never claims that “men actually avoid death,” but that they are justified in trying to do

so, and that everyone will recognize this.41

Gert prefers to call Hobbes’s position “rational

egoism,” highlighting the normative element of this part of Leviathan’s argument.42

Hobbes

argues that political agents should make their judgments according to rational self-interest, and

that were they to do so, cooperation would be easier and society more peaceful. But as any

reader of Leviathan knows, Hobbes is intensely concerned with the effects of passions unrelated

to self-preservation. His detailed advice on the training and education of citizens makes sense

only on the revised reading of his psychological premises.43

In the conventional psychological

egoism picture, self-interested agents require only an adjustment of the incentives they face in

the state of nature to behave cooperatively: the mere addition of sovereign power solves the

problem of order without any change in the citizens themselves. The more complicated

philosophical reading of Leviathan makes much better sense of Hobbes’s repeated insistence that

he is teaching individuals complacency (they will rub off their rough edges so that they fit better

into society); Hobbes’s view from the perspective of rational rather than psychological egoism is

more complicated, but it fits better with the complexities of the actual political world.

The philosophical revisions to the conventional picture of Hobbesian psychology

improve our account of the relationship between morality and psychology. On the standard

view, Hobbes simply collapses the two areas of inquiry. As we shall see in our discussion of the

fool, Hobbes does argue that justice and rational self-interest coincide. However, the revised

perspective leaves room for interesting questions that cannot even be asked from the

conventional perspective. If rational self-interest should lead us to keep our promises, then why

41

Tuck, “Hobbes's Moral Philosophy,” p. 188. 42

See also the important discussion in Gregory S. Kavka, Hobbesian Moral and Political Theory

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), pp. 35-82. 43

Gert, “Hobbes's Psychology,” p. 170.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

22

is sovereign enforcement necessary? Or if entry into civil society requires us to submit to an all-

powerful sovereign, why should programs to enhance citizens’ complacency be necessary?

Several commentators have taken up these questions in recent years. Some, like John

Plamenatz, see the state as the enforcer who ensures that wavering promisers will perform their

obligations; the sovereign, on this account, exists to adjust all calculations of rational interest

such that it is never in a citizen’s interest to violate covenants made.44

For Howard Warrender,

however, divine power underwrites worldly obligations.45

Where Plamenatz sees prudential

covenant-keeping enforced by the state, Warrender sees moral obligation to divine law. Brian

Barry criticizes both views as requiring either a gunman (Plamenatz) or a super-gunman

(Warrender), either an all-prudential or an entirely moral picture.46

On Barry’s reading of

Leviathan, moral obligation begins when a rational agent lays down a natural right. Like Gert,

Barry asks why Hobbes would pay so much attention to religious and civic education if the

sovereign sword alone can keep the peace. “It was precisely because he had seen the fragility of

régimes resting on bayonets that he wrote Leviathan.”47

In a game-theoretic interpretation of Hobbes’s work, Jean Hampton has also argued

against seeing the sovereign enforcer as the sole source of psychological incentives to keep one’s

44

John Plamenatz, “Mr Warrender’s Hobbes,” Political Studies V (3) 1957.. 45

Howard Warrender, The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: his Theory of Obligation (Oxford:

Oxford, 1957). 46

Barry also criticizes Warrender’s claim that we have a moral obligation to follow natural laws

because they are divine commands. Brian Barry, “Warrender and His Critics,” Philosophy XLIII,

no. 164 (1968): 119-20; p. 137, n. 30. Similarly, David Gauthier criticizes those who would

force Hobbes into either the moral or the prudential camp. “Of course Hobbes is trying to

convince us that we have certain moral and political obligations, and the arguments he uses are

based on considerations of prudence and self-interest....denial is absurd on the face of it, and

absurd on reflection. But it does not follow that moral—or practical—concepts employed by

Hobbes are therefore defined in terms of prudence or self-interest...” Gauthier, Logic of

Leviathan, p. 28. 47

Ibid.: 127.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

23

promises.48

Hampton shows that even outside the commonwealth, under most situations it is

rational to follow the third law of nature—to keep one’s covenants made. Hampton’s account

makes sense of Hobbes’s repeated pleas for citizens to see their interests from a long-term rather

than a short-term perspective; if we all had game-theoretic “prospective glasses,” we would be

more likely to see that rational self-interest and moral obligation coincide.

At this point in many readings of Leviathan, recent commentators take one of two tacks.

Either they identify irremediable inconsistencies in the Hobbesian account, and seek to revise the

theory itself, or they resort to pointing out Hobbes’s weaknesses as a writer in order to explain

away the inconsistency of his positions. Barry, for example, admits that Hobbes sometimes says

that the laws of nature create moral obligation, but insists on his own sharp distinction between

the moral obligation created in the laying down of right, and the prudential universe of natural

law.49

For Barry, failure to obey the laws of nature, which dictate self-preserving behavior to

individuals, is “akin to the inability to put two and two together,” while obligation has to do with

contracts among agents.50

It is possible, I shall argue below, to reconcile these two positions

without resorting to criticism of Hobbesian inconsistency. However, Barry and many others are

on firm textual ground when they complain that Hobbes enjoys exaggeration, tends to rhetorical

excess, and never concedes errors or inconsistencies. Sometimes critics attribute these

interpretive difficulties to Hobbes’s “propensity for deep irony.”51

At other times the criticisms

48

Hampton, Hobbes and the Social Contract Tradition. 49

Ibid.: 137. 50

Ibid.: 130. 51

Springborg, “Hobbes on Religion,” p. 349. See also Samuel I. Mintz, The Hunting of

Leviathan: Seventeenth-Century Reactions to the Materialism and Moral Philosophy of Thomas

Hobbes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1962), p. 34.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

24

are more serious; a position is discounted as evidence of “rhetorical exaggeration” or is described

as “characteristically immoderate.”52

Philosophic critics have gone beyond complaining about Hobbesian inconsistency to

attempts to reconstruct a coherent system on Hobbesian premises. The most important of these

recent efforts is David Gauthier’s The Logic of Leviathan. Gauthier agrees with Hobbes that the

state of nature is unstable, even without the conventional assumption of bad human character.

Taking Hobbes’s goals of security and cooperation as his own, Gauthier departs from Hobbes

with his view that absolute sovereignty, put into practice, would endanger rather than secure

social peace. Gauthier realizes that Hobbes would disagree, but he reaches the surprising

conclusion that the regime most coherently expressing Hobbesian principles would be liberal

constitutionalism.53

Like Hobbes, Gauthier argues for the necessity of both a sovereign enforcer

of contracts made and for the gradual taming of the less sociable, less complacent aspects of

human character.54

Gauthier introduces a useful interpretive distinction, between the formal and

the material aspects of Hobbesian propositions. According to Gauthier, if we read the phrase

‘this is good’ formally, for Hobbes it means ‘this is an object of desire’. If, on the other hand, we

read it materially, ‘this is good’ means ‘this enhances vital motion’. Both modes express

singularly Hobbesian approaches to the good, but as Gauthier rightly points out, they have

different implications. Using the formal/material distinction, Gauthier is able to vindicate

Hobbes’s most ambitious philosophical claims—including the unity of reason and justice—

52

Gert, “Hobbes's Psychology,” p. 169; Tuck, “Hobbes's Moral Philosophy,” p. 195. 53

Gauthier, Logic of Leviathan, pp. v, 17 and passim. 54

Ibid. 19-20.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

25

even as he departs from him on matters of regime type and on the infinite-regress argument for

sovereignty: for Gauthier, Hobbes demonstrates both that rational human beings do seek peace,

and that seeking peace is what they ought to do.

Gauthier’s revisions of Leviathan demonstrate the continued vitality of Hobbesian ideas

for present-day politics, though one wonders whether in smoothing out Hobbes’s own rough

edges, Gauthier may have distanced the theory from the complex inconsistencies that arise from

the political world itself. The nicest expression of this worry is still Michael Oakeshott’s: “the

error...lies in attributing to him a theory of political obligation in terms of self-interest; which is

an error, not because such a theory cannot be extracted from his writings, but because it gives

them a simple formality which nobody supposes them to possess.”55

It may well be necessary to improve upon Hobbes’s system if it is to be internally

consistent. However, some of the confusion that results from following Hobbes’s arguments

about moral obligation and natural law to their ultimate conclusions results not from any failure

of reason on Hobbes’s part, but rather from Leviathan’s effort at comprehending political life in

all its multifaceted and incoherent dimensions. Gauthier’s system may be more internally

consistent than Hobbes’s system, but it also depicts a flatter version of political reality. The very

fact that Hobbes scholars have been arguing for centuries about his view of the relation between

morality and prudence should make us wonder whether the question as posed is even

answerable. In pursuit of an answer to this second question, I now turn to competing

interpretations of the central venue for this debate, Hobbes’s discussion of the “fool.”

II. The Fool

55

Oakeshott, “Introduction,” lviii.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

26

Hobbes’s famous discussion of the fool who denies justice provides an ideal text to focus our

discussion of the reception of Leviathan. Not only are the major dividing lines apparent here, but

we shall also be able to see how attention to what divides schools of commentary can prevent the

reader from appreciating the audacity of Hobbes’s ideas. In chapters 14 and 15 of Part I, Hobbes

introduces the “right of nature” (roughly, a right to self-preservation), and the first three “laws of

nature” (rational obligations to seek peaceful coexistence with one’s fellows, to make

covenants—binding agreements—that promote this peaceful coexistence, and to keep the

covenants one has made). He then pauses before listing the remaining sixteen laws of nature to

respond to the fool’s counter-argument. “The fool hath said in his heart: ‘there is no such thing

as justice’; and sometimes also with his tongue, seriously alleging that: ‘every man’s

conservation and contentment being committed to his own care, there could be no reason why

every man might not do what he thought conduced thereunto, and therefore also to make or not

make, keep or not keep, covenants was not against reason, when it conduced to one’s benefit.’”56

Though he is of course referring to the biblical fool who denies the existence of God,

Hobbes excludes cases of divine retribution against covenant-breaking; he is not arguing that it is

always in one’s interest to keep covenants because God will punish covenant-breakers in this life

or the next. He also excludes cases of invalid covenants in which the maker cannot be sure that

the other party will perform. Thus in determining whether reason as self-interest and justice as

covenant-keeping always coincide, Hobbes is not interested in what would have been the easy

cases: the case in which God enforces their coincidence by divine fiat, and the case in which one

would make oneself a patsy by performing with no rational assurance of benefit. Rather, Hobbes

considers the likely ramifications of covenant-breaking from the point of view of the individual

56

Hobbes, Leviathan xv, par. 4.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

27

covenant-breaker. The foolish reasoning that would lead one to break a valid covenant made

(one made either under the umbrella of sovereign enforcement or one in which the other party

has already performed57

) is not, as the fool contends, a substitution of reason for justice. For

both Hobbes and the fool, the law of nature enjoins individuals to pursue their rational interest.

Where the fool sees a conflict between reason and covenant-keeping, however, Hobbes sees a

mistake about the nature of rational interest. For Hobbes, the fool is engaged in a mistaken effort

to exchange long-run relative certainty for short-run initial gains. To paraphrase Hobbes’s

complaint in another context, such foolish reasoners have exchanged their telescopes for

magnifying glasses.58

What looks like a case of doing injustice in the name of rational benefit turns out for

Hobbes to be no such thing, for two reasons. First, the security offered by a stable regime of

kept covenants is a sure thing, while the benefit to be gained through one-time covenant-

breaking may appear to be likely, but is never certain. In other words, we know that our only

reliable security lies in the civil condition, and thus to endanger that civil condition is always to

57

Although Hobbes sometimes speaks as if there are no valid covenants in the state of nature, as

when he declares that covenants without the sword are but words, the bulk of his writing tends to

support the view that covenants are possible in the state of nature. He considers covenants

enforced by a sovereign power to be obligatory to both parties, but also considers the obligations

of first-performers and second-performers without external enforcement other than mere social

reputation. Much of the argument against the fool is devoted to demonstrating that it is rational

to keep covenants if the other party has performed even without the threat of sovereign

punishment, given the uncertain gains to be won from not performing, and given the danger that

losing one’s reputation as a reliable confederate certainly represents. Hobbes’s realistic

distinction in chapter xv between obligation in foro interno (willing that the laws of nature are

respected) and obligation in foro externo (actually following them) makes his position more

nuanced: only a fool would act such that security becomes impossible. See Michael LeBuffe,

“Hobbes's Reply to the Fool,” Philosophy Compass 1 (2006): 12. 58

“For all men are by nature provided of notable multiplying glasses (that is their passions and

self-love), through which every little payment appeareth a great grievance, but are destitute of

those prospective glasses (namely moral and civil science), to see afar off the miseries that hang

over them, and cannot without such payments be avoided.” Hobbes, Leviathan xviii, par. 20.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

28

promote our own insecurity in violation of the laws of nature. Hobbes admits that temporary

advantage may be gained by a one-time breaking of covenant, but argues that this gain is

fundamentally uncertain, while the advantages of security admit of no doubt.

Second, Hobbes reminds us that the conditions of the state of nature are such that no

individual can hope for security without entry into a confederacy of mutual trust. By declaring

oneself willing to break covenants, one effectively isolates oneself in such a way that security

depends wholly upon one’s own power, which is always insufficient. As in his first argument

against the fool, Hobbes distinguishes between the reliable if indistinct benefits of the civil

condition and the uncertain if visible temptations of foolish covenant-breaking. In this second

argument he recognizes that in some cases potential confederates may be stupid enough to

provide security to a covenant-breaker, and thus it seems that sometimes individual benefit may

accrue from unjust covenant-breaking, but declares this apparent gap between reason and justice

to be illusory. We may count on the benefits of a mutual security under a regime of kept

covenants, but we cannot be sure that our confederates will overlook our injustice long enough to

keep us safely enjoying any unjust benefits.

What if the rational benefit to be gained unjustly is so great that it would itself provide

security to the individual who takes it? This may be the fool’s strongest objection to Hobbes’s

position, and Hobbes is eager to answer it. Even when the benefit is a kingdom itself, he argues,

its acquisition by means of covenant breaking exposes the individual to uncertainty and

insecurity: as for “attaining sovereignty by rebellion, it is manifest that, though the event follow,

yet because it cannot reasonably be expected (but rather the contrary), and because (by gaining it

so) others are taught to gain the same in like manner, the attempt thereof is against reason.

Justice, therefore, that is to say, the keeping of covenant, is a rule of reason by which we are

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

29

forbidden to do anything destructive of our life, and consequently a law of nature.”59

The would-

be usurper ought to consider two things. First, he is unlikely to succeed in achieving

sovereignty; the event of such a failed attempt to secure himself by breaking his vow of

obedience to the established ruler would undoubtedly reduce his security. Second, even in the

unlikely event that he does successfully usurp sovereign authority, the very success of his

example will undermine the security he achieves, since in his new role as sovereign he relies on

everyone else’s coventented passivity. A rational agent, considering the radical uncertainty of

the political world and his overwhelming need for personal security, should see that justice as

covenant-keeping coincides with individual rational interest.

Before entering into the detailed discussions of sovereignty and political obligation of

Part II of Leviathan, then, Hobbes argues for his central contention that justice and reason

coincide. His response to the fool contains enough argument and enough ambiguity to supply

centuries of critics with diverging interpretations to defend. The two main interpretations today,

the historical and the philosophical, pick out different aspects of Hobbes’s discussion of the fool

in order to emphasize the conclusions that matter most to each of them. Thus Tuck, for example,

sees the fool primarily as a representative of the skeptical point of view. Tuck’s fool is a foolish

theorist who erroneously equates Hobbes’s supposed destruction of traditional authority with the

absence of authority itself; as such he is a dangerous relativist whom Hobbes rightly refutes.

Hobbesian skepticism about traditional authority is only politically safe when it is accompanied

by self-directed skepticism regarding one’s own judgment. As Tuck writes, “only a ‘Foole’

would suppose that he should take back his right to private judgement in contestable cases, since

59

Ibid.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

30

the whole point of wisdom consists in the recognition of one’s own fallibility in such

situations.”60

The philosophers are more willing than the historians to consider the fool’s point of view,

since they tend to interpret him not as a representative of a philosophical school, but as an

exemplar of the game-playing agent in a hypothetical bargaining situation. In such a context,

Hobbes’s contention that justice and reason coincide is not a commitment to be defended against

skeptics, but a hypothesis to be tested across different bargaining games.61

Like Hobbes,

philosophical game theorists admit that in some cases, individuals could at least temporarily

benefit from breaking their covenants made. For Hobbes’s position to make sense as game

theory, the fool’s having not only decided to break covenant but also declared his willingness to

do so is particularly important. The philosopher’s fool is foolish because he provides a poor

model for rational interaction. Over the series of games/interactions that comprise the Hobbesian

political world, the fool pursuing an unjust benefit will instead reap exclusion and the insecurity

that comes with it.

To read the commentary, one would think that Hobbes’s fool is either a player of games

who gives too much away with his tongue, or a theorist who directs too much skepticism to the

world, and too little toward his own fallible judgment. The philosophers’ fool errs by

exemplifying the wrong kind of game-playing agent: he is a foolish model for rational

interaction. The intellectual historians’ fool errs by taking a particularly foolish theoretical point

of view: he represents a foolish belief. These two fools don’t map neatly onto the categories of

ordinary and elite, or citizen and philosopher, or subject and sovereign, however. The point is

not that Hobbes has an esoteric agenda or hidden messages to different factions. Instead, the two

60

Tuck, “Hobbes's Moral Philosophy,” pp. 194-95. 61

Kavka, Hobbesian Moral and Political Theory, 137-156.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

31

fools represent two types of danger to the state: first, the danger of immoderate citizens

(Gauthier’s “rubbing off of rough edges”), and second, the danger of immoderate philosophy

(Tuck’s “clash of beliefs”). Much of the failure of philosophers to speak to intellectual historians

and vice versa comes from not recognizing these two different enterprises as part of Hobbes’s

general project to secure the state and thus everyone’s welfare by taming the dangerous excesses

of individual judgment among philosophers, citizens, organized doctrinal groups, and everyone

else.

III. Lessons of Leviathan

If, as we have just seen, rational individual interest coincides with political justice for

Hobbes, then why should Leviathan’s project entail what I have just called the taming of

dangerous excesses of individual judgment? One would think that only political theories that

presuppose a divergence of individual interest and political justice would require the

psychological or social transformation of individuals in the interest of the state. (I address the

contents of Hobbes’s recommended transformation towards the end of this essay; for now, I am

simply considering the fact that any transformation at all is required.) Rawls, for example,

employs a distinction between a “Hobbesian” view in which rationality rightly understood

exhausts political morality and a “Kantian” view Rawls would like associated with his own

work, in which the “reasonable” principles that reflect abstract collective agreement always take

precedence over mere rational interest.62

From our revisions of the conventional picture, we can now appreciate the audacity of

Hobbes’s view of moral obligation and natural law. Hobbes denies the existence of moral

62

Rawls, Justice as Fairness: A Restatement, p. 82, n. 2.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

32

obligations that do not contribute to individual self-interest. Sometimes individuals, with their

fallible judgment and unpredictable passions, fail to identify the appropriate courses of action.

But under ideal conditions, one should never be obligated to act against one’s own best interests;

that is, ideally, there is no conflict between duties to the state and duty to oneself. Of course, no

single interpretation of Leviathan has settled the details of when exactly these ideal conditions

obtain. Where are genuine obligations possible? Only in the commonwealth? Only in covenants

where the first party has performed? There is textual evidence for both of these positions and

others, too.

More than three hundred years after its publication, Leviathan is still able to make

important and audacious claims: security underlies everything good about collective life; we

ought to be willing to subordinate dangerous aspects of our will and potentially subversive

groups and doctrines in order to achieve security; we should do these things not for some abstract

ideal, but for our own welfare. The next step in assessing the reception of Leviathan, then, will

deal with questions of the circumstances under which reason and justice coincide, which aspects

of our personalities and societies represent dangerous threats to the commonwealth, and how

these lessons about paying the costs of security and cooperation can be applied over a variety of

political contexts.

The Politics of Rational Individuals

The most ironic moment in the irony-riddled history of the reception of Leviathan comes as part

of the late-twentieth-century movement to interpret the work through the laws of game theory.

As we have seen, game-theoretic interpretations have contributed significant precision to the

formulation of some problems in Hobbes scholarship, most notably to the questions of the

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

33

reasonableness of entry into the commonwealth (Hampton), the limits of absolute rule

(Gauthier), and the nature of Hobbesian moral obligation (Kavka). Game-theoretic

interpretations of Hobbes aim for rigorous philosophical and scientific accuracy in their

descriptions of the human moral and political condition. They eschew the ambitions of less

minimalist, more morally demanding, potentially socially transformative political theories, such

as those of Kant, Rousseau and Marx. Ironically, Hobbes’s radical political vision would require

vastly more extensive social and psychological transformation than Kant’s, Rousseau’s, or

Marx’s systems would. Hobbes’s Leviathan represents not merely a turn toward modernity and

away from tradition, as Strauss would have it. Instead, Hobbes seeks to make humanity safe for

society by paring away community ties and encouraging individuals to act according to rational

motives.63

He writes that though no country can be made permanently safe from its external

enemies, threats to domestic peace are in principle eradicable. Imagining society as a building

made of citizen-lumber, Hobbes suggests that having the “rude and cumbersome points of their

present greatness” shaved off might make the whole society-building fit together well. 64

Though there is no present agreement on these matters, not even within either school of

interpretation, it is possible, as we saw above, to overcome Tuck’s divide--between the “clash of

individuals” reading and one that emphasizes the “clash of beliefs”--by looking for Hobbesian

efforts to pacify a variety of threats to the state. Hobbes does seem to offer a two-tiered strategy

for reaching the peaceful politics that might succeed in the service of life: in the first tier, the

institution of absolute sovereignty provides incentives that might provide some security even for

people with irrational group loyalties and motivating if insubstantiable beliefs; Hobbes’s second

63

Adding new irony to old, the very game-theoretic perspective associated with Hobbes could be

used to demonstrate the resilience of political solidarity as a mode of human interaction: groups

with high solidarity might well out-compete groups without it. 64

Hobbes, Leviathan, xxix, par. 1.

For a new edition of Leviathan and Behemoth (forthcoming, Yale University Press)

34

tier, however, offers the greatest promise for lasting security, according to his own assessment,

and the implementation of this program requires unprecedented changes in the sociology and

psychology of human beings.

Group loyalty, religiosity, and other motives that confounded Hobbes have not faded

away in the centuries since Leviathan appeared. Much of humanity today inhabits commercial

society, accepts the scientific method, and uses technology; many are even residents of systems

whose legitimacy owes a significant debt to the Hobbesian concepts of consent, natural equality,

and contractarian right. Despite all this, people continue to evaluate their interests in terms of

group membership, fighting and sometimes dying for values that Hobbes and modern-day

Hobbesians readily expose as imaginary or at least insubstantial.