Overcoming the Fear of Free Falling: Monetary Policy Graduation in Emerging Markets

The prevalence and correlates of fear of falling in elderly persons living in the community

Transcript of The prevalence and correlates of fear of falling in elderly persons living in the community

The Prevalence and Correlates ofFear of Falling in Elderly PersonsLiving in the Community

Cynthia L. Arken, PhD, Helen W. Lach, MSN, Stanley J. Birge, MD,and J. Philip Miller, AB

IntroductionFalling in elderly persons can lead

to disability, hospitalizations, and prema-ture death.1'2 It may also result in apsychological trauma termed fear offalling.3'4 Such fear may lead to stayinghome or other self-restriction of activi-ties with debilitating physical conse-quences. Although fear of falling isrecognized as potentially having bothpsychological and physical consequences,few studies have examined this fear'-"IMoreover, these studies have been lim-ited by use of select samples: smallgroups of patients,5'6 elderly personsliving in housing units or retirementhomes,7-'0 or volunteers." Althoughthese studies have reported isolatedassociations with factors such as de-crease in mobility or poor balance, theassociation of fear of falling with de-creased quality of life and increasedfrailty is unknown. Likewise, the preva-lence of fear of falling in a randomsample of community-dwelling elderlypersons is unknown.

In addition to reporting associa-tions with factors such as mobility orbalance, two studies have examined theassociation of fear of falling with theprior falling experience of subjects.7'8One study examined prevalence of fearof falling in subjects with one or morefalls in the prior year,7 and the otherexamined restriction of activities after anoninjurious fall.8 However, develop-ment of fear of falling may also berelated to other measures previouslyused in research on geriatric falls:circumstances of the fall,'2'13 recurrentfalls,'1'7 or severity of resulting injury.'8

The current study was developed to

examine prevalence of fear of falling and

its association with measures of falling,quality of life, and frailty.

MethodsThe current study was added at the

1-year follow-up of a cohort study ofcommunity-dwelling elderly persons. Theprimary purpose of the parent study wasto design a simple screening tool to beused in the physician's office for predict-ing falls in elderly persons.

From the St. Louis OASIS (OlderAdult Service and Information System)membership of 16632 older adults, agender- and age-stratified randomsample of 1358 community-dwelling el-derly persons was recruited (66% partici-pation rate) to provide approximatelyequal numbers in four age groups: 65through 69 years, 70 through 74 years, 75through 79 years, and 80 years or older,with a ratio of 2 women to 1 man in eachage group. Subjects from each stratumentered the study evenly over the courseof a year with no excess of difficult-to-recruit subjects in the later months. Toavoid subjects with severe cognitiveimpairment, individuals with 12 or moreerrors on the Mini-Mental State Exami-nation'9 were excluded from the study(n = 15).

The fall surveillance procedure ini-tiated after recruitment consisted of

Cynthia L. Arfken and J. Philip Miller arewith the Division of Biostatistics, WashingtonUniversity School of Medicine, St. Louis, Mo.Helen W. Lach and Stanley J. Birge are withthe Program on Aging, Jewish Hospital, St.Louis, Mo.

Requests for reprints should be sent to

Cynthia L. Arfken, PhD, Center of HealthBehavior Research, 660 S Euclid, Box 8012,Washington University School of Medicine,St. Louis, MO 63110.

This paper was accepted July 13, 1993.

American Journal of Public Health 565

Ariken et al.

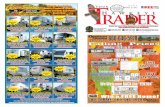

TABLE 1-The Prevalence (%) of Fear of Falling, by Gender and Age Groups

Men Women

66-70y 71-75y 76-80y 81+y 66-70y 71-75y 76-80y 81+y(n = 87) (n = 82) (n = 66) (n = 58) (n = 156) (n = 158) (n = 137) (n = 146)

No fear 86 85 86 79 79 63 60 55Moderately fearful 10 15 12 16 15 26 28 34Very fearful 3 0 2 5 6 1 1 12 1 1

subjects reporting falls to a hot lineimmediately after the fall plus monthlypostcards to document any falls they hadsustained, whether or not they hadreported the falls by phone. Each monththe investigators called all subjects whodid not return postcards to verify thatthe subject was still in the study andsolicit information about any unreportedfalls. After a report of a fall from the hotline, postcard, or phone, one of twotrained gerontological nurses conducteda brief telephone interview with thesubject to verify that a fall had occurredand the circumstances and outcome of it.12

One year after initial recruitment,890 subjects received a structured in-home reassessment. Reasons for loss tofollow-up included death (n = 30), mov-ing (n = 2), refusal (n = 125), budgetarycuts (subjects recruited in the last 2months were dropped [n = 290]), andincomplete information (incomplete in-terview [n = 33], telephone interviewonly [n = 69]). Those lost to follow-upwere, on average, older than those forwhom follow-up information was ob-tained. No other differences were foundbetween those who were followed-upand those who were lost to follow-up.The final sample was predominatelyfemale (67%), White (93%), and edu-cated (62% finished high school). Over-all, 78% rated their health as excellentor good.

The in-home reassessment was con-ducted by lay interviewers and includeddemographic characteristics, health sta-tus, activity level, satisfaction with life,depressed mood, and a brief physicalassessment. To measure the extent offear of falling, the following questionwas asked of everyone: "At the presenttime, are you very fearful, somewhatfearful or not fearful that you may fall(again)?"

Quality-of-Life MeasuresQuality-of-life measures covered

mobility and social activities, satisfaction

with life, and depressed mood. Themobility and social activities measuresconsisted of three questions on fre-quency of leaving the building or resi-dence but not the yard, frequency ofleaving the building and yard, andfrequency of participating in social activi-ties (i.e., "religious or club meeting,visiting friends or family, eating withother people, going to a social event orhaving friends in"). These three mea-sures were dichotomized before thisanalysis by using a cutpoint of threetimes per week. These cutpoints werechosen for ease of interpretation and thecriterion that at least 5% of the samplebe in one of the categories. Satisfactionwith life was dichotomized by using thecontrast of "very" to "somewhat" or"not at all" satisfied. Depressed moodwas analyzed with the Geriatric Depres-sion Scale,20 a 30-item scale where ahigher score indicates a more depressedmood. Both the total score and adichotomous score were used. The latterscore used the recommended cutoff of11 as suggestive of depression.21Frailty Measures

Frailty measures covered episode ofnear fall, inability to walk 10 blocks,requiring assistance to climb stairs, poorvision limiting ambulation, use of assis-tive device to ambulate, general healthstatus, and a balance score from thephysical assessment. The balance assess-ment consisted of maintaining parallel,semitandem, and tandem stances for 10seconds in each stance with eyes openand then with eyes closed. The balancescore was computed as the number ofstances correctly maintained (maxi-mum = 6). This variable was dichoto-mized with a score of 4 or less suggestingimpaired balance, a decision based onclinical interpretation.

Falls MeasuresMeasures of experience with falls

covered a single fall, recurrent falls (two

or more), a fall other than a trip or slipover a recognized hazard, a fall resultingin injury, a fall requiring medical treat-ment, a fall resulting in a fracture, or afall with a delay in getting up (more than1 minute). These falls must have oc-curred after recruitment and before thein-home reassessment.

AnalysisStatistical analysis consisted of first

testing for differences in quality of life,frailty, and falling by the extent of fear offalling with the chi-square test forcategorical variables and the Kruskal-Wallis Rank Test for the continuousscore on the Geriatric Depression Scale.Then the associations of the categoricalvariables with fear of falling were summa-rized as odds ratios (ORs) obtainedfrom multivariate logistic regressionswith gender, age (as a continuous vari-able), and gender and age interactionterms. The corresponding large-sample95% confidence intervals were alsocalculated.

Fear of falling in the logistic regres-sions was analyzed both as an ordinalvariable with three levels and as adichotomous variable. For the latter, weused models contrasting "moderatelyfearful" with "no fear" and modelscontrasting "very fearful" with "no fear."Logistic regression was also used to testthe association of fear of falling as anordinal variable with age and gender.Factors independently associated withfear of falling as an ordinal variable wereidentified by using logistic regressionwith stepwise selection after verifyingthat the proportional odds assumptionwas met. All analyses were conductedwith SAS.22

To assess the effect of the chosencutpoints, we used probability plots.23From these plots, the associations ofmobility and social activities with fear offalling appeared monotonic. For bal-ance, the associations would be maxi-mized at cutpoints of 3 to 4.

April 1994, Vol. 84, No. 4566 American Journal of Public Health

Fear of Falling

ResultsThe majority of the sample (71%)

expressed no fear of falling, whereas 9%reported they were very fearful offalling. Table 1 presents the fear-of-falling prevalences by gender and agegroups. Women were more likely thanmen to express some fear of falling (35%vs 15%; P < .0001). However, fear offalling increased with age for bothgenders. In women, 21% of the youngestgroup (66-70 years) reported some fearof falling. This prevalence;increased to45% in the oldest age group (81 + years).In men, 14% of the youngest groupreported some fear of falling, vs 21% ofthe oldest group.

Those who were very fearful offalling were most likely to have adecreased quality of life (Table 2).Almost half (48%) of those persons whowere very fearful of falling stated thatthey were somewhat or not at allsatisfied with life. In addition, 25% hadscores suggesting depression. The con-tinuous score on the Geriatric Depres-sion Scale also differed by the extent offear of falling: those who were very fear-ful had a mean score of 8.3 (SD = 4.8);those who were moderately fearful had amean score of 7.2 (SD = 4.6); and thosewho were not fearful had a mean scoreof 4.8 (SD = 3.6) (P < .0001).

After gender and age adjustment,those who were very fearful of fallingstill had an elevated risk for worsequality of life on every measure (Table3). This elevated risk was most pro-nounced for infrequently leaving thebuilding (OR = 6.05). In contrast, thosewho were moderately fearful of fallingdid not have elevated risks for decreasedmobility and social activities. However,they did have elevated risk for dissatisfac-tion with life (OR = 1.82) and de-pressed mood (OR = 2.20).

Those who were very fearful offalling were most likely to be frail orhave falls on all measures (Table 4).Almost all (85%) of those who were veryfearful of falling had impaired balance.The percentages of subjects with im-paired balance did not materially changeafter excluding those who refused toperform the balance assessment (47% ofsubjects who had no fear, 66% who weremoderately fearful, and 79% who were

very fearful). Although the interviewerswere instructed to stand near the subjectin case assistance was needed, subjectsfearful of falling may still have beenfearful of trying the more difficult stances.

TABLE 2-The Prevalence (%) of Decreased Quality of Life, by Subject's Level ofFear of Falling

Subject's Level of Fear

ModeratelyQuality-of-Life No Fear Fearful Very Fearful

Measure (n = 633) (n = 190) (n = 67) pa

Infrequently leave 3 3 13 <.0001building but not yardb

Infrequently leave 6 10 22 <.0001building and yardb

Infrequent social 29 27 40 .11activitiesb

Less than very satisfied 21 34 48 <.0001with lifec

Depressed moodd 8 18 25 <.0001

aChi-square test of homogeneity, df = 2.bLess than three times per week.c"Somewhat" or "not at all" vs "very" satisfied.dScore of 11 or more on Geriatric Depression Scale.

TABLE 3-Associations of Fear of Falling with Quality-of-Life Measures

Moderately Fearful: Very Fearful:Not Fearful Not Fearful

Quality-of-LifeMeasure OR 95% Cl OR 95% Cl

Infrequently leave building 1.07 0.41, 2.80 6.05 2.46,14.90but not yarda

Infrequently leave building 1.00 0.54,1.83 2.94 1.45, 5.96and yarda

Infrequent social activitiesa 0.90 0.62, 1.31 1.75 1.03, 2.97Less than very satisfied 1.82 1.26, 2.63 3.08 1.81, 5.25

with lifebDepressed moodc 2.20 1.36, 3.57 3.18 1.68, 6.04

Note. Odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals (Cis) were obtained from logistic regressionmodels including gender, age, and gender and age interaction term.

aLess than three times per week.b"Somewhat" or "not at all" vs "very" satisfied.cScore of 11 or more on Geriatric Depression Scale.

Of those subjects who were very fearfulof falling, 9% had had a fracture in theprior year compared with less than 0.5%of those with no fear and 2% of thosewith moderate fear. The reported frac-tures were ankle, hip, and leg (threesubjects with no fear); pelvis, ribs, wrist,and shoulder (four subjects with moder-ate fear); and three hips, two shoulders,and one face (six subjects who were veryfearful). Delay in getting up after a fallwas similarly uncommon but more fre-quent in those very fearful of falling.Although this variable was dichotomizedat greater than 1 minute, one subject layon the ground over 1 hour after falling.

Almost all (91%) of those who were

very fearful of falling reported at least

one of the characteristics associated withfrailty, in contrast to 59% of those withno fear of falling.

After gender and age adjustment,those who were very fearful of fallingstill had an elevated risk for both frailtyand experience with falls on everymeasure (Table 5). This risk was mostpronounced for fractures (OR = 28.16)and using an assistive device to ambulate(OR = 9.87).

To evaluate the independence ofthese associations, we conducted analy-sis using stepwise logistic regressionmodels. Five variables were independently associated with extent of fear offalling (Table 6). These factors were a

fall resulting in a fracture (OR = 6.65),

American Journal of Public Health 567April 1994, Vol. 84, No. 4

TABLE 4-The Prevalence (%) of Frailty and Recent Experience with Falls, bySublect's Level of Fear of Falling

Subject's Level of Fear

Moderately VeryNo Fear Fearful Fearful(n = 633) (n = 190) (n = 67) pa

FrailtyImpaired balanceb 51 70 85 <.0001Episode of near fall 30 52 58 <.0001Inability to walk 10 blocks 28 51 61 <.0001Requiring assistance 28 62 67 <.0001

to climb stairsVision limiting ambulation 3 5 i6 <.0001Fair or poor self-rated health 17 31 46 <.0001Use of assistive device 8 22 43 <.0001

to ambulate

Experience with fallscAtleast 1 fall 26 36 48 <.0001Recurrent falls (2 or more) 8 13 22 <.0001Fall besides trip or slip 1 1 17 34 <.0001Fall with injury 1 1 14 24 .01Fall with medical treatment 2 6 15 <.0001Fall resulting in fracture < 0.5 2 9 <.0001Delay in getting up after 3 4 15 <.0001a fall, more than 1 min

aChi-square test of homogeneity, df = 2.bBalance score of 4 or less.cin the prior 12 months.

TABLE 5-Associations of Fear of Failing with Frailty and Recent Experiencewith Falls

Moderately Fearful: Very Fearful:Not Fearful Not Fearful

OR 95% Cl OR 95% Cl

FrailtyImpaired balancea 1.75 1.21, 2.55 4.44 2.15, 9.17Episode of near fall 2.78 1.97, 3.93 3.61 2.12, 6.13Inability to walk 10 blocks 2.21 1.55, 3.15 3.48 1.99, 6.08Requiring assistance 3.65 2.54,3.65 4.66 2.62, 8.30

to climb stairsVision limiting ambulation 1.11 0.48, 2.60 4.79 2.09,11.01Fair or poor self-rated health 1.94 1.32, 2.85 3.72 2.16, 6.40Use of assistive device 2.82 1.74, 4.56 9.87 5.22, 18.68

to ambulate

Experience with fallsbAt least 1 fall 1.52 1.06, 2.17 2.49 1.48, 4.20Recurrentfalls (2 or more) 1.71 1.01, 2.89 3.12 1.6t, 6.06Fall besides trip or slip 1.47 0.92, 2.34 3.69 2.05, 6.63Fall with injury 1.21 0.74,1.98 2.26 1.20,4.26Fall with medical treatment 2.29 1.02, 5.18 6.31 2.59, 15.38Fall resulting in fracture 4.23 0.86, 20.73 28.16 5.89,134.66Delay in getting up after 1.36 0.57, 3.23 4.52 1.94, 10.52a fall, more than 1 min

Note. Odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals (Cis) were obtained from logistic regressionmodels including gender, age, and gender and age interaction term.

aBalance score of 4 or less.bin the prior 12 months.

TABLE 6-Factors IndependentlyAssociated with Fearof Falling

OR 95% Cl

Fall resulting in 6.65 2.02, 21.97fracture

Requiring 4.31 1.95, 9.54assistanceto climb stairs

Vision limiting 3.72 1.12,12.34ambulation

Fair or poor 2.89 1.32, 6.34self-rated health

Fall besides trip 2.71 1.29, 5.71or slip

Note. Odds ratios (ORs) and confidenceintervals (Cis) were obtained from step-wise logistic regression analysis.

requiring assistance to climb stairs(OR = 4.31), vision limiting ambulation(OR = 3.72), fair or poor self-ratedhealth (OR = 2.89), and a fall besides a

slip or trip (OR = 2.71).

DiscussionFear of falling was common in this

sample of relatively well community-dwelling elderly persons and compa-

rable to that reported for a retirementcenter.9 The associations of fear offalling with frailty and falls suggest a

consistent trend toward a greater degreeof association of these variables with a

greater degree of fear. Although otherunmeasured factors (such as personalityand social factors) may play a role, thefactors examined here had strong associa-tions with fear of falling even afteradjustment for gender and age. More-over, in multivariate analysis, the extentof fear of falling was independentlyassociated with experience with falls(fractures and falls not caused by a tripor slip) and frailty (problem climbingstairs, vision limiting ambulation, andpoor health).

The strong and consistent associa-tion of fear of falling with decreasedquality of life highlights the public healthrelevance. Given the design constraints,we cannot say whether the decreasedquality of life preceded, accompanied, or

followed the development of fear offalling. This caveat is also true for frailtyand experience with falls. For this

reason, we did not attempt more com-

plex analyses assuming directionality(e.g., frailty leading to falling leading to

568 American Journal of Public Health

Arfken et al.

April 1994, Vol. 84, No. 4

depressed mood leading to fear offalling). Asking about fear of falling atinitial recruitment and at the reassess-ment would have been preferable bothfor determining generalizability and forpredicting the development of fear offalling. However, the supposition thatdecreased quality of life follows a fall issupported by a case-control study8 onnoninjurious falls in retirement homesthat found greater restriction of activi-ties or death 180 days later.

Relying on the response to onequestion to determine the extent of fearof falling is a potential concern. Otherresearchers have defined fear of fallingas curtailment of activities,8 curtailmentof activities because of fear of falling,7and self-efficacy in avoiding falls whileperforming specific activities." Thesediverse definitions have advantages anddisadvantages. Curtailment of activitieshas been criticized for lack of reliabil-ity.'1 Self-efficacy, while theoreticallypromising in being sensitive to change,suffers from difficulty in administration(i.e., subjects have to understand andestimate the extent of their confidence intheir ability to avoid falls while perform-ing a select list of activities). The approachwe used is a step toward understandingthis phenomenon and has been used byothers.9"0

Three additional concerns are thelow response rate for the parent study,the reduced cohort for the present study,and the reliance on self-report for frailtymeasures. The response rate, althoughsimilar to that reported by other investi-gators in gerontological research,24 istroublesome because it is plausible thatthose who were fearful of falling mighthave been more likely than others torefuse to participate. This bias wouldhave the effect of underestimating theprevalence of fear of falling. We inter-viewed subjects in their homes to mini-mize missing those subjects who wereafraid to leave their home, but we maystill have underestimated the prevalenceof fear of falling.

Addressing the second concern, thecohort for the current study was 34%smaller than the recruited cohort, whichlimits generalizability. However, the ma-jority of this decline (62%) was initiatedby the investigators (i.e., terminatingsurveillance on those recruited in thelast 2 months of the study). Analysisconfirmed that the persons in the re-duced cohort did not differ from thosewho were not followed, except that thosewho were not followed were older. This

April 1994, Vol. 84, No.4

analysis suggests that we may haveunderestimated the prevalence of fear offalling in the original cohort and alsolimited our power to detect associationsin the older age group.

The third concern is the reliance onself-report. The resulting associationsbetween self-report of frailty and self-report of fear have competing interpreta-tions. The subjects could have a rationalfear of falling in response to their frailty.Alternatively, the subjects could befearful and view themselves as more frailthan they are. Although we included aperformance-based measure of frailty(balance), the performance may bebiased by fear of trying.'0

One of the strengths of this studywas that we used prospective documenta-tion of falling with telephone verificationfor all the falls reported.25 Therefore, weavoided biases due to potential differen-tial recall of past falls. However, we didnot assess falls occurring in the remotepast or the impact of falls experienced byothers, both ofwhich could influence thedevelopment of fear of falling. Forexample, someone hearing of a trau-matic fall leading to institutionalizationmay become fearful of falling. Thisanalysis indicated that half of those whowere very fearful of falling had not fallenin the prior 12 months. We don't knowhow long they had been fearful or howthe fear was triggered. A more extensivelook at the fear of falling should incorpo-rate these factors.

In conclusion, we found fear offalling to be common in a sample ofcommunity-dwelling elderly persons. Theextent of the fear was associated withself-reported and performance-basedmeasures of frailty and prior experiencewith falling. The observed associationsof fear of falling with decreased qualityof life and mobility confirm the need foreffective interventions to prevent andlimit the consequences of falls in elderlypersons. O

AcknowledgmentThis work was supported by grant AGP01-6815 from the National Institute onAging, National Institutes of Health.

References1. Baker SP, Harvey AH. Fall injuries in the

elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 1985;1:501-512.2. Committee on Trauma Research. Injuiy

in America. Washington, DC: NationalAcademy Press; 1985.

3. Tinetti ME, Speechley M. Prevention of

Fear of Falling

falls among the elderly. N Engl J Med.1989;320:1055-1059.

4. Hindmarsh JJ, Estes EH Jr. Falls in olderpersons. Causes and interventions. ArchIntem Med. 1989;149:2217-2222.

5. Murphy J, Isaacs B. The post-fall syn-drome. A study of 36 elderly patients.Gerontology. 1982;28:265-270.

6. Bhala RP, O'Donnell J, Thoppil E.Ptophobia. Phobic fear of falling and itsclinical management. Phys Ther. 1982;62:187-190.

7. Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF.Risk factors for falls among elderlypersons living in the community. NEngl JMed. 1988;319:1701-1707.

8. Vellas B, Cayla P, Bocquet H, de PemilleP, Albarede JL. Prospective study ofrestriction of activity in old people afterfalls.Age Ageing. 1987; 16:189-193.

9. Walker JE, Howland J. Falls and fear offalling among elderly persons living in thecommunity: occupational therapy inter-ventions. Am J Occup Ther. 1991;45:119-122.

10. Maki BE, Holliday PJ, Topper AK. Fearof falling and postural performance in theelderly. J Gerontol. 1991;46:M123-M131.

11. Tinetti ME, Richman D, Powell L. Fallsefficacy as a measure of fear of falling. JGerontol. 1990;45:P239-P243.

12. Lach HW, Reed AT, Arfken CL, et al.Falls in the elderly: reliability of aclassification system. J Am Geriatr Soc.1991;39:197-202.

13. Campbell AG, Bornie MJ, Spears GF.Risk factors for falls in a community-based prospective study of people 70years and older. J Gerontol. 1989;44:M112-M117.

14. Campbell AJ, Reinken J, Allan BC,Martinez GS. Falls in old age: a study offrequency and related clinical factors. AgeAgeing. 1981;10:264-270.

15. Nevitt MC, Cumming SR, Kidd S, BlackD. Risk factors for recurrent nonsyncopalfalls. A prospective study. JAMA4. 1989;261:2663-2668.

16. Cumming RG, Miller JP, Kelsey JL, et al.Medications and multiple falls in theelderly: the St. Louis OASIS Study. AgeAgeing. 1991;20:455-461.

17. Dunn JE, Rudberg MA, Furner SE,Cassel CK. Mortality, disability, and fallsin older persons: the role of underlyingdisease and disability.Am JPublic Health.1992;82:395-400.

18. Sattin RW, Lambert Huber DA, DeVitoCA, et al. The incidence of fall injuryevents among the elderly in a definedpopulation. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131:1028-1037.

19. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR."Mini-Mental State": a practical methodfor grading the cognitive state of patientsfor the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-198.

20. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al.Development and validation of a geriatricdepression screening scale: a preliminaryreport. JPsychiatrRes. 1983;17:37-49.

21. Brink TA, Yesavage JA, Lum 0,Heersema P, Adey M, Rose TL. Screen-ing tests for geriatric depression. ClinGerontologist. 1982;1:37-44.

22. SAS Procedures Guide, Version 6, Th1irdEdition. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1990.

American Journal of Public Health 569

Arfken et al.

23. Wartenberg D, Northridge M. Definingexposure in case-control studies: a newapproach.AmJEpidemiol. 1991;133:1058-1071.

24. Kelsey JL, O'Brien LA, Griss JA, Hoff-man S. Issues in carrying out epidemio-logic research in the elderly. Am JEpidemiol. 1989;130:857-866.

25. Cumming SR, Nevitt MC, Kidd S. Forget-ting falls. The limited accuracy of recall offalls in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc.1988;36:613-616.

570 American Journal of Public Health April 1994, Vol. 84, No. 4