The Pervasive IS Organisation - ESMT Berlin

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of The Pervasive IS Organisation - ESMT Berlin

The Pervasive IS Organization

Professor Joe Peppard

European School of Management and Technology

Schlossplatz 1

10178 Berlin

Germany

Phone: +49 30 21231-8020

e-mail: [email protected]

ABSTRACT

The fundamental premise of the discourse presented in this paper is that the inability

of many organizations to generate value from their investments in IT is primarily due

to legacy thinking and practices. In particular, it argues that positioning the IS

organization as a separate organizational unit, while valid when computers first

entered organizations, is a flawed practice today and a significant contribution to this

situation. In challenging the dominant orthodoxy of a separate IS unit, the paper

proposes the concept of the Pervasive IS Organization as a more appropriate construct

in meeting the new role of IT and its contribution to enterprise performance. This

concept is built on the premise that generating value from IT is not about managing

technical artefacts but in harnessing knowledge that is distributed across the

organization and, increasingly, in customers, suppliers and other third parties. The

elements of the pervasive IS organization are presented and its implications

developed.

Keywords: IS Organization, Value, Organization Design, Distributed Organization,

Knowledge, Knowledge Integration, IS Management

Submission to

Journal of Strategic Information Systems, September 2013

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 2 of 37

In envisioning the future we are all too often constrained by the past. This is

reasonable as the past often symbolises a place of comfort and familiarity,

characterising what has proven to work and be effective. It also represents that which

is known and predictable. It does mean, however, that progress from there will

inevitably be slow and incremental. More crucially, the past can restrict our thinking

about the future and limits the sphere of possibility.1 Henry Ford captured this

sentiment well when he is reportedly to have said that if he had asked his customers

what they wanted they would have replied “a faster horse”!

Today, how traditional established offline businesses in industries such as retail,

transport, health care, construction, manufacturing, banking, insurance and aerospace

manage their IT resources, both knowledge and the technology itself, is strongly

rooted in the past. And the implications of this are everywhere to be seen. Quite

simply, it is severely constraining the generation of business value from investment

that organizations make in information technology. Just look at the evidence: even

the more modest estimates suggest that at least 40% of investments in IT are failing

(Nelson, 2007; Procaccino et al., 2006; The Royal Academy of Engineering, 2004;

Comptroller and Auditor General, 2006; Shpilberg et al., 2007). The real figure is

probably much higher.

1 In a 1992 Editorial in MIS Quarterly, Blake Ives noted the limitations of drawing on the past for

guidance about the future. He wrote: “Industry understands that they must now re-engineer rather than

just automate outdated methods. But within the information systems research community we continue

to value an extensive trail of references that often reflect outdated assumptions and yesterday’s

economics. We are not necessarily paving the cow path, but rather extending it. It is a rare article that

explores the implications of changing economics on the central research question or that challenges the

dated assumptions upon which past works might have been based. If we are to re-engineer information

systems research we must spend less time pouring over the archives and more time soaking in

innovative organizations. It is there, rather than in the rear view mirror, that the realities of the

transformation of information management will become apparent.”

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 3 of 37

While acknowledging the great advances that have been made over the decades in

managing technologies, such as with software distribution, security, control of

computer networks, software development, automated IT service management,

virtualization and the use of commercial packaged software, the reality is that most

organisations approach the generation of business value from IT investments in much

the same way as when computers were first introduced into organizations. The

fundamental assumption is that deploy the technology successfully (on time, within

budget and meeting the technical specifications – and most projects are measured

against these metrics) and expected benefits will begin to flow. While this statement

might seem logical, the overwhelming evidence presents a more complex relationship

between technology, change and benefits realization that must be considered (Hughes

and Scott Morton, 2006; Maklan et al., 2011; Peppard et al., 2007). At a more

fundamental level it also highlights the lack of clarity around the concept and practice

of ‘IT management.’ Is it concerned with the management of the technology and IT

operations (as illustrated by the first sentence of this paragraph) or does it have a

much broader meaning that is associated with competitive differentiation, innovation

and business value realization? If it is the latter, do all employees not have a role to

play?

What is clear is that the contribution of IT to both organizational performance and

competitiveness has changed drastically since computers first entered organizations.

What organization can survive today without its IT systems? Increasingly, business

models are being defined by information and IT. Compliance is an information driven

endeavour. Many retailers and gaming companies now drive their marketing activity

from data. “Big data,” “consumerization of IT,” “social media,” “mobility” and

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 4 of 37

“cloud computing” are just some of the significant items on the agenda in many

organizations today. What our research is highlighting is that at the core of the

problem with IT is the IT function itself. Or rather, how it is conceptualized, designed

and positioned and its contribution assessed. With the consumerization of IT, for

example, with users bring their own personal devices to work and connecting to the

corporate network or using their own home broadband for work purposes, where is

the boundary of the IS organization? If usage of information is a critical determinant

of the value realized from IT investments, are not all employees part of the IT

function? The bottom line is that neither organizational structures, processes or

resource configuration have shifted to reflect the changing role of IT in organizations

today. In fact, all are now a distinct barrier to the generation of business value from

IT.

What our research suggests is that most organizations are organizing and mobilizing

their resources – people, processes and technology – in ways that almost guarantee

that they will experience severe problems with their IT investments. In short, IT is

being managed based on legacy thinking. And practices emanating from this thinking

are ground in a paradigm that focuses on deploying technology and managing

infrastructure and IT operations and service delivery rather than generating business

value; practices that emphasise managing technical artefacts rather than harnessing

distributed knowledge.

In this paper an alternative way of looking at the IS organization2 is presented that

challenges the dominant orthodoxy of the IS organization as a separate IS unit. It

2 In the article IS organisation and IS function are used interchangeably.

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 5 of 37

questions conventional conceptualisations of IT in organizations and the role and

function of the traditional IS organization. The paper argues that we cannot view the

IS organization as a separate organizational unit if the focus is to be on generating

business value; rather, it must be conceptualised as a pervasive construct. The

implications of this perspective are profound.

A short history of the IS organization

What is today generally referred to as the IS organization, IT department or IS

function represents a concept that has evolved over the last 50 years, not just in name,

but in role, function and position in an organization. Words such as “information”,

“services”, “systems”, “processing”, “management”, “data”, “technology”, and

“computer” have been combined in many permutations to refer to this organizational

sub-unit. Monikers such as Computer Department, eDP Department, DP Department,

MIS Department, Computer Services, Information Technology Department,

Information Systems Department, Information Systems and Technology Department,

Information Services, Information Management Department, and Digital Business

Department are just some that have appeared over the years.

Labels have also changed over time with any modification in name usually reflecting

a new role and focus for information systems and technology in the organization.

Early eDP Departments, for example, concentrated on just that, the processing of

corporate data. The key role of such departments was essentially to keep the

organization’s computer system up and running. Data was brought to the computer

room to be processed, using punched cards, in batch mode. At that time, technology

investments were primarily made to automate clerical tasks, where cost reduction and

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 6 of 37

improvements in efficiency were the key investment objectives. The subsequent focus

on the provision of information from data processing systems for management

decision making saw many organizations rename this unit the Management

Information Systems (MIS) or Information Services Department. More recently, in

some organizations, Digital Business Departments and Business Technology have

appeared, replacing what may once have been called IS Departments, reflecting the

emergence of the Internet and e-commerce and the increasing prevalence of IT in the

conduct of business.

While giving the appearance of change, re-labelling merely represented a change in

name. All it does is move the proverbial deckchairs on the Titanic. Compare the

structure of any IT function of the 1960’s or 70’s and it will reveal little difference

from today’s blueprints. And most IS organizations tend to look much alike.3 The

basic assumption behind this dominant design is that IT, or more correctly, the

generation of business value through IT (I am assuming that this is the reason

organizations invest in IT), can be achieved by managing within a separate unit in the

organization: just look at any organization chart. This is a fatally flawed premise.

Successfully deploying and managing the technology is a necessary but not a

sufficient condition if value objectives are to be achieved.

Yet there was a time when the notion of a separate organizational unit dedicated to

keeping the computer running was an appropriate response. Back then, IT had a

peripheral role to play in business success. The Head of IT prioritised IT spend,

decided how much was needed for computing resources, decided what the business

3 McDonald (2007) has suggested that IS organizations look much alike because they have been rapidly

standardizing to the point of reaching a dominant design.

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 7 of 37

could and could not have and put together the annual IT spending plan. He – and it

typically was a male – even prioritised processing jobs. This was the ‘priesthood’ of

IT based on technology worship. However, and this is the crucial point, the

knowledge and resources necessary for success – defined as keeping the computers

running – were located in this organizational unit under his/her direct control. The IS

organization was, by-in-large, self-sufficient. Today, this knowledge is distributed;

and not just across the organization but often into suppliers, vendors, business

partners and customers. The challenge is no longer to keep the computer systems

running – this can in fact be outsourced – but to coordinate and integrate this

knowledge to generate business value. This requirement demands a fundamentally

new paradigm and a new response. Not only have the rules of the game changed, but

we are now playing a different game!

Memo to CxOs: Pssst, IT is Different!

Of course, most CEOs and other C-level executives today remark that, yes, they do

see IT as being strategic for their business. They readily acknowledge that it is now

fundamental for operations and competitiveness. They then, rightly, proceed to

manage it like any other so-called strategic resource.4 This response is, however,

based on a view that IT is like other resources and can be “managed” in a similar

fashion. This is a misconception and lies at the heart of the problem. IT is different;

fundamentally different. Until CEOs and other C-level executives recognise this, any

expected value to be delivered through IT investment will remain as elusive as ever.5

4 From an empirical study of strategic IT alignment, Kearns and Lederer (2003) suggest a question of

interest is “Why do CEOs appear to articulate support but apparently not provide it” (p. 22). 5 For a study highlighting the poor IT savvy or digital literacy of most CEOs and CxO and the

implication this has for generating value from IT, see Peppard (2010).

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 8 of 37

To a large extent, the other functional areas, with the possible exception of HR and

Finance (which we shall come to shortly), can essentially operate within broad silos as

long as there is some level of lateral coordination, communication and learning

(Kogut and Zander, 1996). Take for example, the Manufacturing function, typically

responsible for producing a company’s products. Once it is determined what has to be

made, in what quantities and by what date, the Head of Manufacturing can essentially

get on with the task of managing the production process, assuming procurement and

on-time delivery of required raw materials (if there is a separate procurement

function). Once produced, the product can then be shipped to the customer by staff

from the Logistics area. “Value”, from the manufacturing perspective, is created by

converting raw materials input into a finished product – of course we could argue that

value is ultimately not created until purchased and paid for by the customer, a debate

that is irrelevant to our argument.

Of course, the Head of Manufacturing has no control over sales and would never be

held accountable for product sitting in inventory or lying on shelves. That is the

responsibility of the Sales and Marketing function. If input materials fail to arrive at

the factory on time, this is clearly an issue for the Head of Procurement. The

manufacturing supremo is, however, responsible for any quality issues that may arise

during production, although this concern might possibly be traced back to the original

design of the product or the raw material input used. Improving production processes

through continuous improvement initiatives also fall under his remit; essentially

producing more with less. For a global organization, distributed manufacturing sites

add an additional layer of complexity and risk. However, this does not distract from

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 9 of 37

what the Head of Manufacturing can and cannot be held accountable for. Their job

can be precisely specified and appropriate performance metrics assigned.

Of course, the big problem with this “functional” approach – a division of labour – to

organization design, where specific knowledge is corralled into a specialist

organisational unit, is the silo mentality that it entails and the lack of focus on the end

customer. The thrust of the business process reengineering movement of the early

1990s was on addressing this lack of end-to-end accountability for the customer

(Hammer, 1990). Without technology, providing this level of customer focus can be

impractical or even impossible to achieve and a functional structure is probably the

best structural arrangement to organize for work. In addition, IT enables work to be

performed in new ways; ways not possible without technology. Consider the

collaborative technologies used to support global research and development (R&D)

efforts. Processes transcend traditional organizational functional boundaries and are

typically assigned “owners” who are accountable for outcomes. For organizations

structured this way, these processes become the focus of attention. Control over

resources resides with process owners, at least in theory; execution can pose more of a

challenge.6

Thus, for each functional area of a business, executives can essentially get on with

their assigned responsibilities, as long as there is a certain level of coordination across

these business areas. Whether it is Marketing or Production or Sales or Logistics.

Indeed, to achieve this degree of coordination, executives manage around the

boundaries of their unit, particularly at the interface with other functional areas. For

6 For a recent take on organizational processes, see Hall et al. (2009).

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 10 of 37

example, if demand for products exceeds production capacity, the Head of

Manufacturing will look to the sales organisation and other areas of the business to

prioritise. Factory capacity is finite, and this can be easily demonstrated: it is

impossible to produce more than current capacity can accommodate. The time and

cost to bring new or additional facilities on stream can be calculated with some

precision.

The inappropriate notion of an IT factory

In the majority of organizations today the IT organization is treated as a factory and,

like manufacturing operations, managed in a similar way; just consider prescriptions

promoting Managing IT Like a Business (Lutchen, 2003) or Running IT Like a

Business: Accenture’s Step-by-Step Guide (Kress, 2011).7 Indeed, there are also

concepts promoted for managing IT that come directly from manufacturing industries,

such as “Lean IT” or “the industrialization of IT.” Within this context, the CIOs and

his executive team manage around the boundary of their unit – often referred to a

“boundary spanning”. They reach out to other executives by cultivating relationships.

They often establish formal liaison roles – often called “relationship managers” – to

work with business units and translate business requirements into technical

functionalities as well as present potential opportunities provided by IT. They also

appoint service delivery managers to ensure “the business”8 receives required services

at agreed service levels. However, these practices are based on a perspective that the

role of the IT function is to build systems and infrastructure as well as operate,

maintain and deliver services. Unlike with manufacturing, achieving these goals does

not guarantee that business value, in terms of contributing to operational and strategic

7 Notice that it is assumed that “IT” is referring to the IT organization.

8 A distinction between “the business” and those employees, many of them IT professionals, residing in

the IT unit is often made in contemporary discourse. The argument being developed in this paper is that

there should be no such distinction.

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 11 of 37

performance, will be achieved. All it does do is assure that systems are built, services

are delivered and infrastructure maintained.

This raises a key question as to what can and cannot be controlled by functional

heads. Unless he has a larger remit, the Head of Manufacturing only requires control

over resources associated with plant, machinery and manufacturing staff to undertake

the role effectively. In contrast, for the CIO, all the resources required to deliver

business value through IT are not under his direct control, unless value is defined in

terms of up-time, network and application availability and service levels. Generating

this value is highly dependent on others in the organization; ultimately it is a shared

partnership. Implementing a new process configuration and changing work practices

as a result of a new IT investment, for example, are not something that the CIO can

mandate (unless, of course, he has a larger remit, such as responsibility for business

operations, marketing or customer service and the investment is focused in one of

these areas).9 All the CIO can really do is ensure that any required technology is

deployed on time and too budget. For benefits to be generated it requires ownership,

engagement and active involvement. Relevant business managers, for example, need

to ensure that necessary changes to processes and work practices actually occur and

that information and IT are used (Marchand et al., 2000). The conundrum that CIOs

face today is that they are often put on the spot to generate business value from IT but

don’t have access to the necessary knowledge or resources (Peppard, 2007).

The level of engagement and involvement in the management of employees provides

an interesting counterpoint. CxOs and other executives readily acknowledge that

9 In some organisations responsibility for IT rests within a broad business area. For example, the Head

of Retail Banking at one financial institution also has responsibility for IT.

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 12 of 37

employees must be deployed effectively. They actively manage them – not leaving

this task to the HR organization. HR staff can provide certain competencies for

recruitment, selection and advising on general employee policies10

– executive

management agree them – as well as ensuring compliance to those policies. They can

also work with the business areas to ensure that the “right” candidates for particular

roles are hired, often using the services of recruitment agencies to identify potential

employees. What is a crucial point is that executives recognise and accept that they

have a central role to play if employees are to make a value-added contribution. What

CxO would not wish to be involved in hiring direct reports or members of his team?

They also manage their staff directly11

; the HR organization is not expected to do that.

They agree their performance objectives, conduct regular performance and

development reviews and generally motivate and mentor them. Why then do they not

exhibit the same behaviour or attitudes in respect of information and IT?

From managing technical artefacts to harnessing distributed knowledge

The trouble is that most executive teams see IT as a technical artefact: the desktop and

other devices, servers, cables, routers, storage and, of course, software. Implicitly,

they designate the role of the IS organization, the CIO and the IT specialists it

employs, to specify, design and maintain this equipment and ensure availability of

services as per any service level agreements (SLAs). The notion of ‘IT management’

is thus seen as managing all this technology and the design of contemporary IS

organizations mirrors this objective. Indeed, the distinction that is often made between

“demand” and “supply” in the context of IT management reflects the requirement for

10

Many of these are driven by legislation. 11

Of course, an executive may be a “bad” manager, but this is a different issue.

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 13 of 37

the business to specify requirements – demand – and the IS organization to supply

technology to meet these requirements (Mark and Rau, 2006). However, this is far too

simplistic a distinction.

How IT is managed in most organizations is based on the premise that the objective is

to get the technology deployed and to keep it functioning: a techno-centric

perspective. The assumption can only be: get the technology in, ensure it continues to

function and any expected benefits with automatically flow. Consequently, the focus

of attention is on building technological systems, maintaining legacy infrastructures,

and running data centres. This was all very fine when the requirement of the CIO (or

EDP or Computer Manager, as the incumbent was typically called in the early days)

was primarily to keep the technology systems running. Today, IT has significant

operational and competitive impact and consequently, it cannot be treated in the same

way.

By establishing an IT unit, whatever its label, the assumption can only be that all the

knowledge necessary to deliver business value through IT can be located in that

function. Yet evidence clearly concedes that knowledge from other areas of the

organization outside of the IT function is required if this value is ultimately to be

delivered. While knowledge is “owned” by the individual, the integration of this

knowledge12

takes place at a collective level: groups and other collective forums,

some of which are formal others informal (Okhuysen and Eisenhardt, 2002). Although

specialist knowledge is required to accomplish many tasks in an organization, there

12

It is not the intention to enter into the debate between “knowledge” and “knowing.” For an

elaboration on this point see Orlikowski (2002).

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 14 of 37

are also situations in which individuals with specialised knowledge must integrate

their knowledge in a group or other collective to realise its value.

For example, prescriptions around the IS strategy process demand the involvement of

executive management if it is to be effective (Broadbent & Weill, 1993; Jarvenpaa

and Ives, 1991; Kearns & Lederer, 2003; Reich & Benbasat, 2000; Ward & Peppard,

2002). Why? Because there is incomplete knowledge in the IT function, in particular

with the CIO, to successfully develop this strategy. Prioritizing IT spend requires

knowledge of business issues, priorities and strategies; knowledge that is distributed

among the senior leadership team. Project teams to implement an IT investment, such

as ERP or CRM, are typically composed of both IS specialists and managers and users

from across organisational units impact by the new IT system. Why? Because the all

knowledge to successfully implement the new IT system and deliver the benefits

articulated in the business case are not resident within the IT unit. The project team is

charged with integrating this distributed knowledge (Bhandar et al., 2007; Newell et

al., 2004; Mitchell et al., 2006).

Indeed, the technical infrastructure is the embodiment of knowledge: knowledge that

has been deployed by systems architects, developers, communications experts, etc. in

its design and construction. Maintaining this legacy also requires knowledge, and

while much of this knowledge will be primarily technical, some knowledge of

business imperatives will also be required; for example, in making the decision as to

whether to decommission an application will depend on whether it is required by the

business. Using information effectively is critically dependent on the application of

knowledge, particularly in making decisions or generating insight. Applications

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 15 of 37

themselves are the automation of organizational knowledge; sometimes embedded in

rules and workflows. Outsourcing arrangements can be similarly viewed as

knowledge based (Kotlarsky et al., 2007); indeed, many organizations argue that they

have outsourced their IT to an External Service Provider (ESP) or vendor as it will

provide them with access to knowledge that they do not themselves possess.

Yet, managing IT has never really been about technology anyway. It has always been

a knowledge oriented undertaking. Keeping complex mainframe computer systems

functioning required lots of specialised knowledge, most of it of a technical nature.

And, when this was the only requirement, this knowledge was best housed within a

separate organizational unit. Importantly, it was all under the jurisdiction and control

of a single individual.

What we are claiming is that the necessary knowledge to deliver business value from

IT is distributed throughout the organization. Crucially, it is not located solely in the

IT function and under the jurisdiction of the CIO. In fact, much of the knowledge

required is under the control of other C-level executives. This is why it has been

stressed as being of crucial importance for the CIO to build relationships with these

executives (Ward and Peppard, 1996): to ease access to knowledge resources under

their control. If not, access to this knowledge will be difficult if not impossible. Even

with access, the organization must have the capability to coordinate and integrate this

knowledge (Grant, 1996). This requires not just having a personal network providing

access to knowledge, but also demands that trust, shared understanding and

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 16 of 37

cooperation exist between parties for collective action to happen.13

If all the required

knowledge cannot be harnessed then it is then unlikely that business value from IT

will be generated.

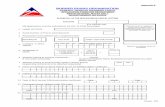

Figure 1 illustrates two scenarios for prioritizing IT spend. In scenario (a) there are

weak ties between all the executives that have relevant knowledge. In this situation,

the CIO may be left with no alternative but to “second guess” business strategy and

what business priorities are and the consequential information and systems

requirements.14

In scenario (b) ties are much stronger, facilitating greater knowledge

access.

Figure 2 illustrates a project team established to implement an enterprise system. In

scenario (a) there are weak ties both within this team as well as with those not part of

this team but whose knowledge is required for a successful implementation. It is very

likely that the project will struggle. In scenario (b) connections are much stronger,

facilitating greater knowledge access.

13

This is the basic premise of social capital. Social capital can be seen as networks of strong, personal

relationships developed over time that provide the basis for trust, cooperation and collective action. See

Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998). 14

In an as yet unpublished survey of 695 CIO, 55% reported that they are not involved in defining and

agreeing strategy.

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 17 of 37

FIGURE 1 The CIO and knowledge flows for prioritizing IT spend. Network (a)

illustrates the scenario where the connectedness of the CIO to CxO colleagues for

access to relevant knowledge to determine strategic priorities is weak. Network (b)

presents the scenario where the CIO has stronger connections with CxOs facilitating

greater knowledge access.

CIOs do attempt to facilitate access, coordination and integration of knowledge,

although they may not always recognize this as either the objective or outcome of the

initiatives they promote. For example, many have appointed relationship managers as

a conduit, facilitating knowledge flows between the IT function and rest of business.

However, while such initiatives seek to provide access to knowledge they may not

directly impact knowledge integration. In reality, they usually act as translators of

requirements or reporters of problems. Establishing governance structures, such as

committees and other cross organizational forums, bring individuals with relevant

knowledge together to debate particular issues related to IT, make specific decisions

and have oversight on decisions and outcomes. Even where people come together in

such forums, they may chose not to share their knowledge.

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 18 of 37

FIGURE 2 A project team to implement an Enterprise System investment. Network (a)

illustrates the scenario where the connectedness of the team both to each other and

colleagues across the organization is weak. Network (b) illustrates the scenario where

there are strong ties both within the team and to relevant stakeholders outside of the

team.

Some CIOs have introduced educational programmes to improve IT staffs’ knowledge

of the business. This overcomes the fact that it can be difficult to get business

engagement, i.e. access to their knowledge, with the CIO attempting to build this

knowledge inside the IT function. However, this does not overcome the requirement

for business and IT people to cooperate and work together, i.e. integrate and

coordinate their knowledge. To this end, education programmes for non-IT staff are

also instigated to create awareness of IT issues, build digital literacy and highlight

their role in delivery of the expected benefits of IT investments.15

Initiatives like

chargeback, where users are ‘charged’ based on the IT resources and services they

consume, can be used to foster communications between IT and the business units

(Ross et al., 1999). This communication can generate a rich shared understanding for

both parties of the cost and benefits of alternative IT investments and service

offerings. Indeed, research shows that high level of communication between IT and

15

For an illustration of such initiatives see Wheeler (2002).

Project teamProject team

(a) (b)

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 19 of 37

business executives is a direct predictor of alignment of business and IT strategies

(Reich and Benbasat, 2000).

To overcome legacy structures, organizations typically employ a variety of tactics

rather than change the structures themselves. We are seeing more and more decisions

that were traditionally made within the IT organization are being devolved out of the

remit of the CIO and IT function altogether and into the realm of business executives

(see Weill and Ross, 2009); although we also witness resistance of business

executives to assume these new responsibilities. IT governance mechanisms, such as

IT steering committees and other cross function forums are being established to

coordinate the consequence of devolvement as well as encourage the involvement of

relevant parties in decision making processes (Weill and Ross, 2004). These forums

are operating outside of formal structures – within the so called informal organization

– and are central to creating an environment for knowledge access and integration

(Chan, 2002; Preston and Karahanna, 2009; Tan and Gallupe, 2006). Establishing an

IT governance structure is giving tacit recognition that what are often labelled “IT

decisions” are essentially decisions that require the coordination and integration of

knowledge that can be dispersed across an organisation. Even expertise in

technologies is also migrating away from IT professionals and becoming more

embedded in those with functional responsibility; for example, social media in the

Marketing organization and analytics and business intelligence (BI) in Finance

departments. Many applications can now be delivered directly from “the cloud,” with

end users potentially bypassing corporate infrastructures and, more crucially, the IS

organization itself.

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 20 of 37

Towards the Pervasive IS Organization

Figure 3 captures the evolution that we are witnessing in how enterprises organise for

IT. It illustrates that the dominant organizing mode is shifting from hierarchy to

network structures. With this network mode, the IS organization becomes a pervasive

construct: a physical and virtual intra- and inter-organizational network of

connections. The early functional perspective focused on managing within the

boundaries of the IT unit, where hierarchy dominated, and the emphasis was

essentially on building the technology infrastructure and keeping it running and

available. In this situation, the CIO (or whoever heads the function) is an operational

manager and a functional leader. The partnership model still accepts the existence of a

separate IT unit, with the CIO and IT leadership team managing around its boundary,

focusing on building relationships with key stakeholders and seeking to influence

peers. The CIO is a boundary spanner.

The Pervasive IS Organization (PISO) acknowledges that generating value through IT

is a shared responsibility. It is built on the premise that the objective is to generate

value with IT and not to manage IT as an artefact, a subtle but profound distinction. It

also recognizes that this quest requires the harnessing of knowledge dispersed across

the organization. This requires strong connections between those with primarily

business knowledge and those with primarily IT knowledge. The CIO is an

orchestrator. Thus, the Pervasive IS Organization refers to the sum total of all

resources, activities and decisions regardless of where they are located, that are

concerned with optimizing value from IT. On occasions, this knowledge can be

located outside the organizational boundary, particularly with outsourcing.

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 21 of 37

FIGURE 3 Towards the Pervasive IS organization.

The fundamental implication from this analysis is that we cannot put neat boundaries

around an organizational unit and label it the IS organization and expect it to deliver

business value from IT. All such a unit can do is manage the technology (i.e. the

technical artefact) and deliver IT-enabled services. And if building systems and

maintaining the infrastructure was all that was required for IT to generate value,

outsourcing IT is unlikely to have such a high failure rate. Payoffs from IT are

ultimately the responsibility of the entire organization (Devaraj and Kohli, 2003;

Marchand et al., 2000).

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 22 of 37

The Pervasive IS Organization16

is built on the premise that the challenge in

generating business value through IT is to coordinate and integrate knowledge that is

distributed across the organization. Thus, it proposes that delivering value through IT

is a knowledge-based practice and must thus be centred on the marshalling,

harnessing and exploitation of knowledge. That is, the activities, tasks and practices

associated with delivering business value from IT are all knowledge oriented. For

example, as we have already noted, developing an IT strategy is a knowledge-based

task, where employees with relevant knowledge about business objectives and

priorities come together with staff with knowledge about technological capabilities.

The anatomy of the Pervasive IS Organization

In our work with senior executives and board members a recurring question that we

encounter relates to what their role and responsibilities are in relation to information

technology (Huff et al., 2006; Nolan and McFarlan, 2005; Ross and Weill, 2002;

Weill and Ross, 2009). Many recognise the contribution that IT is making to their

business both operationally and strategically but struggle carving out a defined

position for themselves (Andriole, 2009; Kearns and Lederer, 2003). What decisions

should they be responsible for? What should be the extent of their involvement in IT

projects? What can they leave to the CIO (or what can they expect their CIO to

achieve)? Many delegate, even abdicate, anything to do with IT to their CIO.17

The

16

This notion of the pervasive IS organization is not the same as pervasive computing, but does has a

similar genesis. The idea behind pervasive computing is that technology is moving beyond the personal

computer to everyday devices, from clothing to tools to appliances to cars to homes to the human body

to your coffee mug, with embedded technology and connectivity as computing devices become

progressively smaller and more powerful. Also called ubiquitous computing, pervasive computing is

the result of computer technology advancing at exponential speeds – a trend toward all man-made and

some natural products having hardware and software. The “Internet of Things” or “Industrial Internet”

is a recent manifestation of this. 17

John Thorp, author of the Information Paradox (McGraw-Hill, Ryerson, 2003) recounts a recent

conference he attended when the speaker from IBM proclaimed: “CEOs recognize that IT is strategic

and are looking to you, the CIO, to make it happen!” A similar sentiment was expressed by the CEO of

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 23 of 37

concept of the Pervasive IS Organization acknowledges that generating value from IT

is an enterprise-wide responsibility: all employees have some responsibility and a role

to play.

The Pervasive IS Organization has three inter-dependent domains: thinking, doing and

using (see Figure 4).

Thinking addresses questions as to the why, what and the how of IT.

Doing represents the execution of the what through the deployment or

provisioning of the how.

Using refers to the application of the why through the exploration and

exploitation of information.

All these domains depend on the application of knowledge.

FIGURE 4 The triumvirate of the Pervasive IS organization.

In most organizations, the primary focus around IT has tended to be on the doing

aspect: building systems, running IT operations, delivering IS services, maintaining

legacy infrastructures, making systems secure, etc. Indeed, early research focused

attention on these challenges. However, what the Pervasive IS Organization demands

a global energy company: “I know IT is critical to our business but I really don’t have the time.

Anyway, what have I got a CIO for? I just want to concentrate on my core business.”

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 24 of 37

is that it is also imperative to think about the doing (the ‘why’, ‘what’ and ‘how’) as

well as recognise that using information and IT is how value is ultimately generated.

There are also clear relationships between the three domains. The link between

thinking and doing is characterised by the deployment or provisioning of IT. Thinking

leads to the framing of the technological capabilities that will be required. The

connection between thinking and using is defined by the exploitation and exploration

of information. This requires a deep understanding as to how information and

resultant systems should be used by the organization. The link between doing and

using is delivering both change (e.g. new process designs, new ways of working, etc.)

and services to sustain these changes.

Thinking

In the early days of IT in organizations, most of the thinking around IT was done in

the IT Department by IT specialists. In this function, decisions were made as to the

computer systems to buy and the applications to be built and how they would be used

(they was generally used by IT professionals). As the primary role of the IT function

was to procure and develop computer systems and software and keep them up and

running, the thinking about IT was primarily limited to technical matters.

As the role of information and IT has become more strategic and embedded in

organizational processes and practices it is not appropriate for all this thinking to be

undertaken within the confines of an IT unit by the head of IT and his staff, not least if

investments in IT were to be aligned to the business strategy as well as shape

innovative business opportunities. Indeed, much of it must now be undertaken by

executive management (Ross and Weill, 2002

). Thinking demands that a number of key questions should be addressed:

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 25 of 37

Why are we using IT in our business? Is it to support and/or shape strategy?

Does IT underpin our business model?

What are we going to do to address the why (the using and the doing)? What

IT capabilities are required? What information and systems are needed? What

technologies are we going to deploy? What organisational processes will IT

support? What degree of standardization and integration do we require? What

are our priorities for IT? What levels of risk are we prepared to accept? What

will our IT spend be? What criteria will be used to evaluate value delivered

and success? What projects will we undertake? What will be outsourced to

third-parties?

How will the doing be organised, executed and managed? How will IT

projects be managed? How will IT services be delivered? How will

information and systems be used? How will resources be allocated and

marshalled? How will information be used and protected?

Doing

The IT function is historically seen as being concerned with doing “stuff”, essentially

building new IT-based systems, maintaining legacy infrastructures, protecting

information assets and delivering IT services. While most of this has traditionally

been done in-house, the last 25 years has seen more of this doing being outsourced to

third parties. Yet the doing must be driven by thinking, both of the ‘what’ (is to be

done) and the ‘how’ (it will be done) in order to address the ‘why’ (it is needed).

Outsourcing the doing to external providers does not mean that the thinking and using

are now not necessary; thinking and using can never be outsourced. The ‘what’

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 26 of 37

defines the requirement that the business has for information and systems, given its

strategy. The ‘how’ defines the processes and practices through which day-to-day

activities are performed, managed, coordinated and controlled. ‘Doing’ activities fall

into three areas: (IT) projects, IT operations and service delivery. Even doing is

dependent on the application of knowledge.

(IT) projects: Projects are the fundamental building blocks for the implementation of

envisioned opportunities. Ideally, they should be given the go-ahead by executive

management through a prioritisation process. Activities here are concerned with the

implementation of these projects including the planning and management of the

associated change. IT projects will have two interdependent outcomes: change and

creation of IT services for on-going execution and sustainment of new processes. The

exception is pure infrastructure projects which may not require any business change.

All projects require control and coordination. Management should additionally look

for synergies across projects, for example, in procurement or resource utilisation. It is

also important to ensure conformance to any standards and policies, for example use

of development methodologies. Organizations typically have many IT projects

running at the same time; sometimes these are logically grouped together in

programmes. To support the management of all this complexity project/programme

management offices (PMOs) are often established.

IT operations: These are the activities involved in the maintenance of the IT platform

and ensuring that the applications continue to run and are secure. The cost of

performing these activities contribute to total running costs for IT services.

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 27 of 37

Service delivery: This is concerned with the ongoing provision of information

handling services into the organization. It also includes user support and help desk,

and performance measurement and reporting (i.e. against any agreed service level

agreement). It is this capability that is provided via the technology that must be

leveraged by the organization for value to be realized.

Using

Using information and IT systems is a much neglected aspect of IT in organizations;

value is only realised through usage – “the missing link” in performance from IT

(Devaraj and Kohli, 2003). While organizations are increasingly able to gather and

process information from a variety of new sources, competitive advantage will still

belong to those who know how to use it (Ferguson et al., 2005). Without the ability to

work with information, any benefits from deploying technology are unlikely to be

forthcoming (Marchand et al., 2000).

Despite all the advances that have occurred in technology, it must be recognizeed that

IT is deployed in organizations for its ability to handle information. That is, IT

facilitates the provisioning of a range of information handling services. These include

those that enable communication and collaboration (i.e. email, desktop

videoconferencing, inter-organizational systems, instant messaging, collaborative

platforms and social media), data capture (i.e. point of sale (POS) systems, Internet-

based data entry systems, customer portals, sensors), data processing (i.e. order

processing, invoicing, customer query management, account management, resource

management), storage (i.e. data centres and databases with information about

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 28 of 37

customers, inventories, assets, etc.), access (i.e. ad hoc queries, report writing,

dashboards), and analysis (i.e. analytics, knowledge discovery, modelling and

decision support tools). One way of considering this perspective is that, if the

technology fails, it is not the loss of the technology per se that would result in

problems for the organization, but the loss of the organization’s ability to avail itself

of these information handling services enabled by the technology.

Governance as a meta structure: assimilating Thinking, Doing and Using

The domains of thinking, doing and using should be inter-woven into the fabric of an

organization. While not to labour a point, the crucial point is that thinking, doing and

using are not the sole preserve of a separate IT unit or indeed the CIO. Senior business

executives must be particularly involved with thinking and developing the overall

framework for the doing, including establishing appropriate governance structures,

mechanisms and processes. They also guide how information will be used to drive

organizational performance.

In the early days of the IS organizations, the thinking, doing and using were all

essentially undertaken by the DP Department, or whatever label referred to the group

of computer professionals. It decided what systems were required, built them after of

course, deciding how they would be built, and then used them. This was the era when

“the business” came to the IS organization with requests to process data. Gradually,

over time, some activities and decisions moved out of the IS organization. Using went

first, when terminals landed on employees’ desks. New, easy-to-use software tools

harboured the arrival of end-user computing and ultimately saw some of the doing

devolve out of the IS organization altogether (e.g. finance staff building their own

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 29 of 37

spreadsheet models). The thinking has been perhaps the slowest to follow, with

executives at all levels seemingly reluctant to actually engage with relevant IT issues

and make decisions in relation to IT, thinking about how IT should be used and

building an information strategy and establishing a management framework; they still

see the context as concerned with the technology artefact and its management and

thus the responsibility of the IS organization.

However, even this shift has gathered momentum over the last number of years and

has heralded the importance of establishing governance around information and IT

(Sambamurthy and Zmud, 1999; Schwarz and Hirschheim, 2003; Zmud, 1984). This

development has served to emphasise that many decisions, previously considered as

IT decisions, require active business involvement, sometimes accountability, and that

structures, processes and mechanisms are required to ensure coherence in decisions

made, particularly when decision-making is both devolved and distributed (Weill,

2004; Weill and Ross, 2004).

Unfortunately, governance is a much misunderstood concept today, particularly in the

context of IT. Governance is concerned with behaviour and by establishing a

governance structure an organization is attempting to influence behaviours with

respect of information and technology. Moreover, it acknowledges that those with the

appropriate knowledge should make decisions. Sometime this might be an individual;

on other occasions it can be achieved consensus among a group of people.

A governance structure clearly delineates roles, accountabilities and responsibilities. It

also facilitates the coming together of people with relevant and necessary knowledge.

Governance mechanisms include committees and other forums; policies; decision

making processes; and initiatives and practices such as charge-back and rotating

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 30 of 37

employees in and out of IT roles. Policies, for example, define decisions that have

already been made; of course, who gets to set policy must also be determined. These

are some of the levers that the organization has at its disposal to influence behaviour.

Governance is also required around information use and protection; IT projects

require governance; outsourcing requires governance.

The evolving role of the CIO

The discourse around the Pervasive IS Organization raises questions about the role of

the CIO, particularly what a CIO can be expected to achieve and held accountable for.

It also explains why the role of the CIO has been evolving. While it is not the

objective of this paper to explore this evolution, this has been eloquently done

elsewhere (e.g. Chun and Mooney, 2009; IBM, 2009; Centre for CIO Leadership,

2008; Ross and Feeny, 1999), it is giving tacit acknowledgement that the IS

organization must also evolve.

Prescriptively, the CIO role has been portrayed from evolving from a Function Head

to a Strategic Partner and is now being promoted as a Business Innovator. In this latter

role, today’s CIO is expected to be visionary, a technology opportunist and to drive

and shape strategy through the innovative use of IT. Yet even in assuming this latter

role, the CIO cannot overcome many of the constraints that are inherent with legacy

thinking. They cannot be expected to deliver on this new agenda while operating

within traditional structures, processes and mindsets.

This evolving role can additionally be seen as a surrogate for the changing

requirements for IT, reflecting the shifting focus and emphasis of investments that are

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 31 of 37

made in IT. These changing requirements reflects the fact that managing the IT

resource is getting more complex as technology becomes more ubiquitous,

applications become more sophisticated, IT deployment more pervasive, connectivity

much easier, and the role of IT in the business becomes ever more strategic. Business

expectations have also changed.

Over the years the IT leader has assumed an array of decision making responsibilities,

often by necessity, as no one else in the organization is prepared, either by choice or

otherwise, to take responsibility for but that made to be made if technology is to be

successfully deployed (note that I have not said, “value to be realised”). Examples

include, IS strategy formulation, prioritization of projects, and determining IT spend.

Yet, it is widely acknowledged today that there are many decisions that CIOs and

their staff make that they shouldn’t (Ross and Weill, 2002) but in the absence of

anyone outside the IS organization taking responsibility, it usually falls to the CIO to

make them, frequently with incomplete knowledge. How often have we heard CIOs

lament that they are often not involved in strategy discussions or that the corporate

strategy itself is unclear and thus difficult to align an IT investment portfolio to? Or

that business colleagues are reluctant to prioritize IT spend, leaving this task to the

CIO? Or that the business is unwilling to take ownership and get involved in what are

ultimately ‘IT-enabled change projects’?

As responsibilities for decisions historically made by the CIO devolve away from the

CIO – either by choice or otherwise – and into the wider organisation, the fallacy of

seeing the IS organisation as a separate organizational unit becomes all too apparent.

This quote, from the CEO of a large European telecommunications operator, perhaps

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 32 of 37

best captures this sentiment: “And maybe what companies should really be focusing

on is not the creation of a CIO role, but the infusion of IT and information through

every role, and every aspect of the business.… And I think as time passes, senior

managers will come under pressure to become more IT literate. I think we’ll see IT

elements find their way into a wide range of job descriptions and managers’ targets

and objectives. Companies will increasingly recognise that IT has to be an integrated

part of many, if not all, senior management roles. It won’t be acceptable to have a

situation in which the CEO, CFO or any other manager does not understand the ins

and outs of the company’s IT systems and strategy. I think it’s clear that digital

capabilities are becoming more important for companies across almost all industries,

and as a result, digital literacy – in the form of IT literacy – will become increasingly

important for all business leaders” (reported in Peppard et al. 2011).

As decisions are devolved away from the CIO and the traditional IS organization, they

need coordination to ensure coherence. This is achieved by establishing IT

governance structures. One CIO that I have spoken to who had recently launched a

new governance structure for information and IT, commented that if it is successful,

he will be out of a job (reported in Peppard et al. (2011))! By this he meant that he

was pushing responsibilities for making decisions concerning IT out of the IT

organization to his business colleagues. These are the decisions that he currently

makes but acknowledges that they are really decisions that business executives, who

have all the required knowledge, should make or being involved in making.

This also raises the question as to what metrics can be use then to evaluate the

performance of a CIO. With measures like network uptime and systems availability,

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 33 of 37

these only measure how well the existing technology infrastructure continues to

function. Yet, systems may be available, but not be used; if value is to be generated

they must be used effectively. Of course, they may not even be the “right” systems.

We have already argued that CIOs don’t control all the necessary knowledge for value

to be generated, so can they really be held accountable for it? But if they are just held

accountable for the technology who is going to ensure (and be responsible) that all

else that contributes to the generation of value is undertaken? This is the conundrum

that many of them face (Peppard, 2007).

Conclusion

Nearly a quarter of a century ago, Dearden (1987) predicted the demise of the IS

organization. The basic premise of his arguments were that users would soon

completely control individual systems and that systems development would be done

almost entirely by outside software specialists. However, he did not foresee the

tremendous advances in IT and the key role it would play in business and global

commerce. Yet while he was right that the IS organization would wither away he

erred by suggesting its demise based largely on arguments focused on technology

deployment. Focusing on value generation through IT presents a different conclusion.

This paper argues that executives should no longer see their IS organization as a

separate organizational unit but rather as a pervasive construction. The rationale for

this is based on the premise that the focus on generating value from IT should not be

on managing technical artefacts but on harnessing knowledge. This knowledge is not

only distributed across the organization but can also be found in vendors and other

third parties perhaps even customers. The challenge is therefore to integrate and

coordinate this knowledge. This latter objective should define the configuration of

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 34 of 37

resources. To this end, the concept of the Pervasive IS Organization was introduced

and described. Generating value through IT is increasingly concerned with thinking

and using and much less about the doing, although the doing requires no less thinking

if it is to be a success. Just as managers and executives recognise they need to manage

their staff, they must also recognise that they need to assume responsibility for

information and releasing value from it.

References

Andriole, S.J. (2009) “Boards of directors and technology governance: the surprising

state of the practice”, Communications of the Association for Information

Systems, Vol. 24, Article 22.

Bhandar, M., Pan, S.-L. and Tan, B.Y.C. (2007) “Towards understanding the roles of

social capital in knowledge integration: A case study of a collaborative

information system project,” Journal of the American Society for Information

Science and Technology, Vol. 58, No. 2, pp. 263-274.

Centre for CIO Leadership (2008) The CIO Profession: Leaders of Change, Drivers

of Innovation, Center for CIO Leadership, New York.

Chan, Y.E. (2002) “Why haven’t we mastered alignment? The importance of informal

organization structure”, MIS Quarterly Executive, Vol. 2, pp. 97-112.

Chun, M. and J. Mooney (2009) “CIO roles and responsibilities: Twenty five years of

evolution and change,” Information & Management, Vol. 45, pp. 323-334.

Dearden, J. (1987) “The withering away of the IS organization”, Sloan Management

Review, Summer, 1987, pp. 87-91.

Devaraj, S. and R. Kohli (2003) “Performance impacts of information technology: is

actual usage the missing link?” Management Science, Vol. 49, No. 3, pp. 273-

289.

Ferguson, G., S. Mathur and B. Shah (2005) “Evolving from information to insight”,

MIT Sloan Management Review, Winter, pp. 51-58.

Grant, R.M. (1996) “Prospering in dynamically competitive environments:

organizational capability as knowledge integration”, Organization Science,

Vol. 7, pp. 375-387.

Hall, J.M. and M.E. Johnson, (2009) “When should a process be art, not science?”

Harvard Business Review, March, pp. 58-65.

Hammer, M. (1990) “Reengineering work: don’t automate-obliterate,” Harvard

Business Review, July-August, 104-112.

Huff, S., P.M. Maher, M.C. Munro (2006) “Information technology and the board of

directors: Is there an IT attention deficit?” MIS Quarterly Executive, Vol. 5,

No. 2, pp. 1-14.

Hughes, A. and Scott Morton, M.S. (2006) “The transforming power of

complementary assets”, MIT Sloan Management Review, Vol. 47, No. 4, pp.

50-58.

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 35 of 37

IBM (2009) Leadership, Capability and Culture: The CIO’s Silent Revolution, IBM

Corporation, London.

Kearns, G.S. and Lederer, A.L. (2003) “A resource-based view of strategic IT

alignment: how knowledge sharing creates competitive advantage,” Decision

Science, Vol. 34, No. 1, pp. 1-29.

Kogut, B. and Zander, U. (1996) “What firms do? Coordination, identity and

learning,” Organization Science, Vol. 7, No. 5, pp. 502-518.

Kotlarsky, J, I. Oshri, J. van Hillegerberg and K. Kumar (2007) “Globally distributed

component-based software development: an exploratory study of knowledge

management and work division,” Journal of Information Technology, Vol. 22,

pp. 161-173.

Kress, R.E. (2011) Running IT Like a Business: Accenture’s Step-by-Step Guide, IT

Governance Publishing, 1st November, 201

Lutchen, M. (2003) Managing IT as a Business: A Survival Guide for CEOs, Wileys,

New York.

Macklan, S., Knox, S. and Peppard, J. (2011) “Why CRM fails – and how to fix it,”

MIT Sloan Management Review, Vol. 52, No. 4, pp. 77-85.

Marchand, D.A., W. Kettinger and J.D. Rollins (2000) “Information orientation:

people, technology and bottom line,” Sloan Management Review, Summer, pp.

69-80.

Mark, D. and D. Rau (2006) “Splitting demand from supply in IT,” McKinsey on IT,

Fall, pp. 22-19.

McDonald, M.P. (2007) “The enterprise capability organization: A future for IT”, MIS

Quarterly Executive, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 179-192.

Mitchell, V.L. (2006) “Knowledge integration and information technology project

performance”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 4, pp. 919-939.

Mitra, S., Sambamurthy, V. And Westerman, G. (2011) “Measuring IT performance

and communicating value,” MIS Quarterly Executive, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 47-

59.

Nahapiet, J. and S. Ghoshal (1998) “Social capital, intellectual capital, and the

organizational advantage”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 23, No. 2,

pp. 242-266.

National Audit Office (2006) Delivering Successful IT-enabled Business Change,

National Audit Office, Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General, HC

33-1, Session 2006-2007, London, November.

Neilson, G.L., K.L. Martin and E. Powers (2008) “The secrets to successful strategy

execution”, Harvard Business Review, June, pp. 61-70.

Nelson, R. R. (2007) “IT project management: infamous failures, classic mistakes and

best practices”, MIS Quarterly Executive, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 67-78.

Newell, S., C. Tansley and J. Huang (2004) “Social capital and knowledge integration

in an ERP project team: the importance of bridging AND bonding”, British

Journal of Management, Vol. 15, pp. S43-S57;

Nolan, R. and F.W. McFarlan (2005) “Information technology and the boards of

directors”, Harvard Business Review, October, 2005.

Okhuysen, G.A. and Eisenhardt, K. (2002) “Integrating knowledge in groups: how

formal interventions enable flexibility,” Organization Science, Vol. 13, No. 4,

pp. 370-386.

Orlikowski, W.J. (2002) “Knowing in practice: enabling a collective capability in

distributed organization,” Organization Science, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 249-273.

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 36 of 37

Peppard, J. (2007) “The conundrum of IT management”, European Journal of

Information Systems, Vol. 16, 2007, pp. 336-345.

Peppard, J. (2010) “Unlocking the performance of the Chief Information Officer

(CIO)”, California Management Review, Vol. 52, No. 4, pp. 73-99.

Peppard, J., J. Ward and E. Daniels (2007) “Managing the realization of business

benefits from IT investments,” MIS Quarterly Executive, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 1-

11.

Peppard, J., C. Edwards and R. Lambert (2011) “Clarifying the ambiguous role of the

chief information officer (CIO),” MIS Quarterly Executive, Vol. 10, pp. 197-

201.

Peppard, J. and J. Ward, Strategic Planning for Information Systems, Wiley,

Chichester, 2002.

Preston, D. and E. Karahanna (2009) “How to develop a shared vision: the key to

strategic alignment”, MIS Quarterly Executive, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2009, pp. 1-8.

Procaccino, J., J. Verner and S. Lorenzet (2006) “Defining and contributing to

software development success”, Communications of the ACM, Vol. 49, No. 8,

pp. 79-83.

Reich, B.H. and I. Benbasat, (2000) “Factors that influence the social dimension of

alignment between business and information technology objectives”, MIS

Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 81- 113.

Ross, J., M. Vitale, M. and C. Beath, (1999) “The untapped potential of IT

chargeback”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 215-23

Ross, J.W. and P. Weill (2002) “Six IT decisions your IT people shouldn’t make”,

Harvard Business Review, Vol. 80, No. 11 (November), pp. 85-91.

Ross, J.W. and D.F. Feeny (1999) The Evolving Role of the CIO, Center For

Information Systems Research, Working Paper 308, Sloan School of

Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge

Massachusetts.

Sambamurthy, V. and Zmud, R. (1999) “Arrangements for information technology

governance: a theory of multiple contingencies”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 2,

pp. 261-290.

Schwarz, A. and Hirschheim, R. (2003) “An extended platform logic perspective of

IT governance: management perceptions and activities of IT,” Journal of

Strategic Information Systems, Vol. 12, pp. 129-166.

Shpilberg, D., S. Berez, R. Puryear and S. Shah (2007) “Avoiding the alignment trap

in information technology,” MIT Sloan Management Review, Vol. 49 No. 1.

Tan, F. and R.B. Gallupe (2006) “Aligning business and information systems

thinking: a cognitive approach”, IEEE Transactions on Engineering

Management, Vol. 53, No. 2, pp. 223-237.

The Royal Academy of Engineering (2004) The Challenge of Complex IT Projects,

The Royal Academy of Engineering, London.

Ward, J and J. Peppard (1996) “Reconciling the IT/business relationship: a troubled

marriage in need of guidance”, The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, Vol. 5,

No. 1, pp. 37-65. Weill, P. (2004) “Don’t just lead, govern: how top-performing firms govern IT”, MIS

Quarterly Executive, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 1-17.

Weill, P. and J. Ross (2004) IT Governance: How Top Performers Manage IT

Decision Rights for Superior Results, Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Weill, P. and J. Ross (2009) IT Savvy: What Top Executives Must Know to Go from

Pain to Gain, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, Mass.

THE PERVASIVE IS ORGANIZATION

Page 37 of 37

Wheeler, B.C., G.M. Marakas and P. Brickley (2002) “From back office to board

room: repositioning global IT by educating the line to lead at British American

Tobacco”, MIS Quarterly Executive, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2002, pp. 47-62.

Zmud, R.W. (1984) “Design alternatives for organizing information systems

activities”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 79-93.