The organisation of markets as a key factor in the rise of Holland from the fourteenth to the...

Transcript of The organisation of markets as a key factor in the rise of Holland from the fourteenth to the...

Continuity and Changehttp://journals.cambridge.org/CON

Additional services for Continuity and Change:

Email alerts: Click hereSubscriptions: Click hereCommercial reprints: Click hereTerms of use : Click here

The organisation of markets as a key factor in the rise of Holland from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century: a test case for an institutional approach

BAS VAN BAVEL, JESSICA DIJKMAN, ERIKA KUIJPERS and JACO ZUIJDERDUIJN

Continuity and Change / Volume 27 / Issue 03 / December 2012, pp 347 378DOI: 10.1017/S0268416012000239, Published online: 05 December 2012

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0268416012000239

How to cite this article:BAS VAN BAVEL, JESSICA DIJKMAN, ERIKA KUIJPERS and JACO ZUIJDERDUIJN (2012). The organisation of markets as a key factor in the rise of Holland from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century: a test case for an institutional approach. Continuity and Change, 27, pp 347378 doi:10.1017/S0268416012000239

Request Permissions : Click here

Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/CON, IP address: 131.211.206.98 on 04 Jan 2013

The organisation of markets as akey factor in the rise of Holland fromthe fourteenth to the sixteenth century:a test case for an institutional approach

BAS VAN BAVEL*, JESSICA DIJKMAN*,ERIKA KUIJPERS# AND JACO ZUIJDERDUIJN*

ABSTRACT. Although the importance of New Institutional Economics and theinstitutional approach for understanding pre-industrial economic development andthe early growth of markets are widely accepted, it has proven to be difficult to assess

more directly the effects of institutions on the functioning of markets. This paper usesempirical research on the rise of markets in late medieval Holland to illuminate someof the factors behind the development of the specific institutional framework of

markets for land, labour, capital and goods, and some effects of these institutions onthe actual functioning of the markets. The findings are corroborated by a tentativecomparison with the functioning of markets in Flanders and eastern England.

1. INTRODUCT ION: THE THEORET ICAL BACKGROUND

The crucial importance of institutional arrangements for marketperformance has become widely accepted. Following the publication ofThe rise of the western world by Douglass North and Robert Thomas in1973,1 it has become almost commonplace to assert that the ‘rules of thegame’ of economy and society, and more specifically those of the market,limit, encourage and channel market incentives, and thus determine, to alarge extent, the efficiency of market exchange.

It has, however, proven to be difficult to assess the effects of institutionson the functioning of the market. First, the functioning of markets is, of

* Utrecht University.

# Leiden University.

Continuity and Change 27 (3), 2012, 347–378. f Cambridge University Press 2012

doi:10.1017/S0268416012000239

347

course, determined by more factors than institutions alone. Second, evenif we accept that institutions play a large part, difficulties in measuringtheir effect remain great. A single institution may have many effects, someof them beneficial and others damaging to the functioning of markets:how to weigh the advantages against the disadvantages? Moreover, in-stitutions interact : frequently a combination of institutions contributed toa single effect.2

Not only the effects, but also the origins, of institutions have been, andstill are, the subject of discussion. The notion that institutions developmore or less spontaneously because they provide a good answer to econ-omic needs is popular, but it is also problematic. It suggests that efficientinstitutions – with ‘efficient’ defined as contributing most, in a given set ofcircumstances, to the welfare of society – will automatically prevail overless efficient alternatives. Unfortunately, reality is different. Many socie-ties end up with obviously inefficient institutions simply because powerfulgroups or individuals create and sustain institutional arrangements thatsupport their own interests, if necessary at the expense of aggregate wel-fare. A more credible way to account for the development of institutions isthe notion that institutions are the effect of a confrontation betweenvarious social groups. The resulting institutional framework is not auto-matically the most efficient one for society as a whole; it is merely bestsuited to the interests of the elites in power.3

While explaining the development of institutions and assessing theirimpact are difficult even for the modern era, the task is even moredaunting for the pre-modern period because of the scarcity of reliable anddetailed data. Yet, in western Europe, a number of important market-regulating institutions, such as laws on the contracting involved in selling,buying, hiring and borrowing, notaries, regular verification of weightsand measures, public weigh houses, and banks, date back to the lateMiddle Ages. Because these fundamental market institutions emergedthen, this period also offers the best opportunity to study their origins andeffects.

Although we are well aware of all the difficulties, this paper is an at-tempt to explore possibilities for a more systematic reconstruction andanalysis of pre-modern institutional change and its effects, with the fur-ther purpose of inviting discussion of these crucial issues in the field ofeconomic history. By focusing on the rise and organisation of markets inlate medieval Holland we will try to illuminate, first, the factors behind thedevelopment of the specific institutional framework of markets and, se-cond, the effects of institutions on the functioning of the market. To thisend, we have not merely focused on commodity markets, but also onfactor markets, that is, the markets for land, capital and labour. Since the

BAS VAN BAVEL ET AL .

348

exchange and allocation of land, labour and capital are intimately con-nected to social positions and religious and cultural norms, their organ-isation substantially differs by region and period, and these markets arethus probably more important than the more similarly organised com-modity markets in explaining differences in economic development.4 Also,this broad scope has allowed us to study the vital ways in which themarkets for land, capital, labour and commodities have interacted.

The county of Holland, in what is now the Netherlands, but thenformed part of the patchwork of principalities in the Low Countries,offers a relevant test case for the effects of institutions on the developmentof markets. In a process that started in the eleventh and twelfth centuries,this region grew from a peripheral, backward corner of western Europeinto an economic, political and cultural world power, in the course ofwhich the economy and society underwent a profound transformation.The apogee of this development was in the seventeenth century, theGolden Age of the Dutch Republic, but it seems to have already been wellon its way more than a century before. An inquiry into the economicsituation of the county in 1514 shows that, already at that time, about45 per cent of the population of Holland was living in cities, dependingon grain imports for sustenance. In exchange, the region’s agriculturaland industrial sectors produced many export commodities. A substantialpart of the population earned an income from trade or transport.5 Withrespect to the labour market, about half of the labour performed in thecountryside in sixteenth-century Holland consisted of wage labour.6 Thestart of these developments can be dated back even further. The secondhalf of the fourteenth century, in particular, witnessed massive urbanisa-tion and a rise of the secondary and tertiary sectors, labelled the ‘ jump-start ’ of Holland’s economy.7

The idea that a key role in this development could be attributed to theorganisation and institutional framework of markets is not new. Actually,in their pioneering book North and Thomas used the Dutch case todemonstrate the value of their institutional approach.8 They did so byconcentrating on market institutions in the period 1500–1700, althoughcursorily pointing to some medieval precursors. The same applies to thestudy by Jan de Vries and Ad van der Woude on the economy of theNetherlands in the early modern era.9 They posited that in the sixteenthcentury Holland already possessed a highly developed market economy,characterised by a large degree of market freedom, efficient markets andlow transaction costs which they tentatively explain as due to the largedegree of freedom and the absence of a feudal legacy in Holland.Although these authors barely touch upon the causes and pre-history ofthis situation, it is obvious that the origins of the market structures of this

THE ORGANISATION OF MARKETS AND THE RISE OF HOLLAND

349

relatively modern economy must be sought in the Middle Ages. Thisassumption is broadly accepted in the historiography, but hardly tested,especially not in a quantitative sense.

A close historical examination of the development of market institu-tions in medieval Holland results in a number of observations that allowus to analyse the effects of the institutional framework that was in place by1500. In order to do so, we will combine insights from recent in-vestigations by the present authors and largely based on new archivalresearch,10 complemented by a re-evaluation of the secondary literatureand an investigation of relevant documents. In order to corroborate ourfindings, we use a comparative approach. The simultaneous developmentof similar institutions and the growth or integration of markets observedin other regions is not yet a proof of a causal relationship between the two,but such a comparison will nonetheless bring us closer to understandingthe effect of institutional arrangements. In our tentative comparisons wefocus mainly on the institutional framework and functioning of marketsin Flanders and the English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk in EastAnglia (hereafter referred to simply as East Anglia), which were, next toHolland, the parts of northwest Europe where population densities in thisperiod were highest and economic development was most precocious. Thethree areas are of roughly similar size. Holland (that is, the former countyof Holland) measures 6,000 square kilometres including lakes, Flanders(the former county of Flanders, without French Flanders, which lies in thewest of present-day Belgium) 7,000 square kilometres, and East Anglia9,000 square kilometres. All three are examples of pre-industrialflorescence, but the exact chronologies of growth and decline differ.Flanders and East Anglia displayed great dynamism in the eleventh tothirteenth centuries but struggled after the mid-fourteenth century, whichis exactly when the process of commercialisation accelerated in Holland.

Some caveats are in order, however. First, this paper does not claim tofully explain the different timing and pace of economic growth in the threeareas. Its aims are much more modest. It compares the nature of theinstitutions and their direct effects on the functioning of markets, not oneconomic growth at large. Second, not all relevant indicators for theperformance of markets are available for all three areas, so comparisonswill at times be incomplete. Also, we would ideally start this investigationbefore 1300, but quantitative material for Flanders and especially forHolland is far too scarce, and we have therefore limited ourselves to theperiod after 1300. This omits the rapid market developments that hadtaken place in East Anglia during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries,11

reducing the scope of the comparison. Third, comparisons are particularlydifficult for capital markets. In line with common definitions, these are

BAS VAN BAVEL ET AL .

350

defined here as markets where savings are exchanged with titles to futurepayments, which usually run for at least one year. The capital marketshould be distinguished from the money market, where short-term loansare traded, and from the extension of trade credit, which was very com-mon everywhere in late medieval Europe. The long-term debts that aretraded in capital markets allow for the reallocation of relatively largesavings, and thus enabled large investments. The financial instruments weare looking at, in particular the annuity, allowed for the creation of long-term debt that was repaid at the initiative of the debtor, and couldtherefore run for at least several years. Annuities were very common innorthwest Europe, but not so in England, and in this respect direct com-parisons with developments in East Anglia are problematic. Nevertheless,to get an impression of differences and similarities, we will discuss thosefinancial instruments that come closest to the annuity.

We refrain from trying to measure the impact of individual institutions,since it would be impossible to isolate their effect from that of other in-stitutions. Instead we use two indicators that – at least in part – reflect thefunctioning of the whole of the markets for goods, land, labour andcapital : the volume of the market and the integration of markets. Theseindicators are chosen because they can, albeit indirectly, be linked to thequality of the institutional framework. Since other elements and the de-velopment of the real economy also influence these indicators, interpret-ation is not always straightforward, but this is at least a first step. It is alsoa necessary step, since the effects of institutions are often suggested orassumed, but much more seldom quantitatively analysed, and especiallyso for markets for land, labour and capital in the pre-industrial period.Before we embark on this step, we will briefly introduce the main studyarea, Holland, and explain how this paper will proceed.

2. THE CASE: HOLLAND IN A COMPARAT IVE PERSPECT IVE

Holland is the westernmost part of the present-day Netherlands, border-ing on the North Sea. The south of Holland is traversed by the riversMeuse and Rhine. This coastal region remained under the princely rule ofthe Counts of Holland until it was integrated in 1433 into the Burgundianand in 1506 into the Habsburg Empire, together with a host of otherprincipalities in the Low Countries. By that time, it had become one of themost densely populated parts of Europe and by far the most urbanisedone. The region possessed one of the most vibrant economies in Europe,setting the stage for its Golden Age in the seventeenth century, when theDutch Republic dominated world trade, with the town of Amsterdam inHolland forming the main centre.

THE ORGANISATION OF MARKETS AND THE RISE OF HOLLAND

351

In the eleventh century, there was nothing to suggest this futureprominence of Holland’s economy. The region was largely a wilderness,consisting of scarcely inhabited, inhospitable, peat bogs, Compared withneighbouring regions, such as Flanders, Brabant and the Rhineland, thiswas a marginal area. It was only reclaimed in the eleventh to thirteenthcenturies, when the Count of Holland attracted settlers to do the hardclearing work by offering them freedom and well-defined property rightsto the land. A society of free peasants emerged in which ecclesiastical andsecular lords had little influence. The area had become densely populatedwhen, in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, it was faced with anecological crisis : the subsidence of the reclaimed peat soils, a process thatultimately made arable agriculture and the cultivation of bread grainsnearly impossible. Despite these ecological difficulties, Holland recoveredremarkably quickly from the effects of the Black Death: populationdeclined in the region during the first decades after the epidemic, but theeconomy continued to develop and demographic recovery took just afew generations. Meanwhile, urbanisation continued apace during thefourteenth century. While only 14 per cent of the population lived intowns in 1300, their share increased to a quarter around 1350 and a thirdin 1400. About 44 per cent of the c. 260,000 inhabitants of the region livedin towns by 1500. The increase in the urbanisation rate was pre-dominantly caused by the absolute growth of towns, which more thandoubled in size between 1348 and the beginning of the sixteenth century,and not by a decline of the rural population.12 While other Europeanregions experienced a ‘ late medieval crisis ’, Holland displayed dynamism,characterised by thriving export industries and the strong developmentof trade and services.13 This economic development and growth weresustained up to the seventeenth century, when stagnation set in.

These economic and demographic developments set Holland apartfrom the many parts of western Europe that were characterised by stag-nation or crisis. The developments in Holland even contrast with dy-namic, neighbouring regions such as Flanders and East Anglia. The lattertwo regions had been progressive in their economic development in thehigh Middle Ages, but after the middle of the fourteenth century popu-lation numbers stagnated or even declined, and urban growth came to ahalt. In Flanders, the urbanisation rate declined from about 33–36 percent in the fourteenth century to about 25 per cent in the fifteenth centuryand after.14 In East Anglia the urbanisation rate actually increased duringthe fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Around 1300, about 15 per centof the population of Suffolk lived in towns, while 200 years later thisproportion had doubled to about 30 per cent.15 However, this growingurbanisation rate was not the result of urban population growth in

BAS VAN BAVEL ET AL .

352

absolute terms but rather of a severe decline of the rural population. Inthe fourteenth century, the population fell by more than half and did notbegin to grow again until the early sixteenth century.16 At the same time,markets contracted or were deserted.17

The contrast with Holland can hardly be explained by geographicalfactors. Holland, Flanders and East Anglia were all located on thesouthern shores of the North Sea, had similar climatic conditions, andenjoyed similar advantages of location near waterways. There weredifferences in soil conditions, but these rather disadvantaged Holland,since the region was virtually sinking into the water. This paper cancontribute to understanding this issue, by investigating to what extent theorganisation of markets formed a main difference. All three regions wit-nessed an early rise of market exchange of goods, in the highMiddle Ages,and later also of land, labour and capital. It can therefore be hypothe-sised, in line with the above, that the specific institutional organisation ofthese markets decided to what extent regions were able to cope with theecological, economic and demographic challenges of the period from themid-fourteenth century onwards. This leads to the following centralquestions: did markets in Holland function better than elsewhere,especially compared with neighbouring Flanders and East Anglia? If so,what were the underlying causes of their favourable functioning?

Our analysis of the institutional arrangement of markets in late med-ieval Holland starts with a reconstruction of the main institutions ofmarket exchange and their specific characteristics (section 3). Next, weattempt to assess qualitatively and, when possible, also quantitativelywhat the effects of these institutions were on the growth of the volume ofthe market and on the integration of markets in Holland, compared withthe other two cases (section 4). This will be followed by a tentative ex-planation of the contribution of socio-political elements to the emergenceof specific institutions in Holland. We will look particularly at theelements standing out most clearly in the medieval history of Holland: theecological situation, the occupational history and the structure of society(section 5). Conclusions follow in section 6.

3. THE DEVELOPMENT OF MARKET INST I TUT IONS IN

HOLLAND 1100–1500

3.1 Property rights and personal freedom

In Holland, virtually absolute and exclusive property rights to land de-veloped in the high Middle Ages, allowing a dynamic land market todevelop which was exceptional in the context of western Europe,18 where,

THE ORGANISATION OF MARKETS AND THE RISE OF HOLLAND

353

in most regions, transfers of land did not involve market transactions:they remained firmly embedded in all kinds of social frameworks such asthe extended family, the village community, the commons, or the manor.Even in Norfolk and other areas of eastern England – where manorialismwas relatively weak in comparison with other parts of England, freeholdland was substantial and the land market was lively – lords and manorialcourts had a clear influence on property rights to land and their transfer.19

In Holland, however, and to an almost equal extent in Flanders, these andthe other non-market frameworks had lost their strength at an early date,or never held that position. In the early phase of settlement, most peasantsin Holland acquired free ownership of the land that they reclaimed fromthe peatlands. In the fourteenth century, all peasants in Holland were freeand the vast majority were owners of the lands they cultivated, thusopening the way for exchange of land by way of the market.

This development was accelerated by the role of local and centralauthorities. In Holland, and in adjacent parts of northwest Europe, localauthorities in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries had already startedto register property rights to land and land transfers, mainly for fiscalreasons.20 This increased the security of land transfers. Levies on transferswere quite low, or even completely absent, in contrast to the situationelsewhere in Europe where lords were able to extract high levies on landtransfers. The latter was also true for Flanders, where seigniorial leviesamounted to 8 to 16 per cent of the sale price ; in East Anglia fealty paidwith the transfer of free land and especially the entry fines paid with theinheritance or sale of customary land in the fifteenth and sixteenth cen-turies – although low in an English context – were often even higher thanthis.

It has to be added that in contrast to the solid legislation on landtransfers and property rights, the lease market in Holland was less regu-lated. Rights with respect to leased land remained unclear. Peasants inHolland claimed all kinds of permanent rights to the land, even when thelease was formally for a fixed term. This situation provoked conflicts andinsecurity with respect to investments in leaseholds. Only in the sixteenthcentury, under the legal and social pressure from the growing group ofurban landowners in Holland, did lease rights become clarified – muchlater than in most of northwest Europe.21

The emergence of a capital market was closely connected to the devel-opment of property rights to land. Long-term loans required debtors touse mortgages as securities, and therefore clear titles to property were ofutmost importance. In Holland, and in the rest of the Low Countries,registration of real estate transactions with the local court played a vitalpart. The vast majority of transactions in the markets for land, and

BAS VAN BAVEL ET AL .

354

subsequently also for capital, were concluded in the presence of two ormore aldermen, or other local officials, who were witnesses and attachedtheir seals to the contract. Only a few people opted for contracts ratifiedby lords, clerics or even notaries, which were not fully recognised by civillaw and provided little security.22 Whereas these property rights regimesallowed for the early emergence of capital markets from the thirteenthand fourteenth centuries, in England divided rights to land and the frag-mented registration of these rights among several jurisdictions hinderedthe emergence of a mortgage system.23 Several seventeenth-centurypamphleteers also noticed this situation and pressed for a reorganisationof registration systems in England.24

In Holland, moreover, clear property rights were distributed among allsocial groups, including women, who were allowed to participate in landmarkets and capital markets. Access to these markets provided womenwith a comparatively independent position and allowed the majorityof widows in Holland to run their own households.25 In this respect, dif-ferences with East Anglia appear to have been small, but in Flandersproperty rights of widows declined in the fourteenth and fifteenth cen-turies.26

Likewise, the history of labour in Holland is characterised by earlypersonal freedom. In the highly commercialised regions of Holland,Flanders, Norfolk and Suffolk, the burdens of serfdom and villeinage hadbeen reduced at an early date, either because the legal obligations of serfsand tenants were no longer enforced or because aristocratic manorscomprised only a very small segment of total landholdings. Nearly 80 percent of all peasants in Suffolk were free by 1300.27 In Flanders serfdomfrom the thirteenth century became rare except in the imperial Land ofAalst, where all peasants were direct subjects of the count and still for-mally considered serfs.28 In Holland the nobility and church only exploi-ted a few domains, mainly in the sandy area behind the dunes. Labourservice was limited to these domains and was completely replaced bymonetary rents by the late Middle Ages.29 In practice, there must havebeen a considerable degree of labour mobility in all three areas, yet, unlikeHolland and Flanders, England had developed labour legislation after theBlack Death that remained in place and that could be called upon when-ever a need was felt by employers.30 The aim of the fourteenth-centurystatutes on labour was to restrict the mobility of the landless populationand to keep wages at pre-epidemic levels. They proclaimed service to becompulsory for every single man or woman without visible means ofsupport. The breaking of contracts before the end of the usual term of oneyear was punishable by fines, imprisonment and corporal punishment.31

In Flanders similar laws could be found but focused on servants.

THE ORGANISATION OF MARKETS AND THE RISE OF HOLLAND

355

The breaking of contracts by labourers and servants was a criminaloffence for which the ordinances prescribed corporal punishment.32

In Holland labour legislation could only be found in some urban by-lawsand concerned wage labourers in commercial urban industries and wasmainly aimed at the prevention of strikes.33 Labour legislation for agri-cultural workers and servants was virtually non-existent and remained soafter 1350. Wage earners could move freely from one place to another.The Count of Holland and the Estates (the representative body of nobilityand commoners increasingly dominated by the towns) never set wages,nor did they issue penal laws on wage payments above customary levels.Labourers and servants were supposed to serve the usual terms, but in alleconomic sectors they seem to have had more contractual freedom andtherefore a stronger bargaining position as to the terms of contract than inneighbouring regions.34

In Suffolk both the prosecution of workers who accepted higher wagesand the continuing high burdens of villeinage resulted in frustration andviolent uprisings of the labouring class against landlords and authoritiesin the late fourteenth century.35 All over England, labour legislation led tothe foundation of specialised courts and in many parts of the country tointensive prosecution.36 In fourteenth-century Norfolk, these laws were allenforced through different types of courts. Justices enforced the estab-lished wage levels while contracting was regulated in the so-called quartersessions.37 Although records are lacking for the fifteenth century, JaneWhittle supposes that enforcement continued during this period becausethis structure was still in operation after 1532.38 In the sixteenth century,new statutes renewed both the obligation to work and the obligation toserve long terms.39

The development of elaborate labour legislation in England cannot beentirely related to post-1350 demographic decline. Samuel Cohn showsthat labour shortages occurred in many parts of Europe in the secondhalf of the fourteenth century; yet, the reactions of legislators differed;sometimes there was no reaction.40 One of the factors influencing thesituation in England was that the landholding gentry enjoyed importantpolitical power as they had access to parliament personally or viapetitions. The legislation of the mid-fourteenth century predictably re-presented their interests in an attempt to strengthen the employers’ con-trol over labour.41 This situation did not change during the subsequentcenturies.

One could argue that Holland was less severely hit by the Black Deathand employers there were not confronted with labour shortages to thesame extent as employers in England. However, the cause may be morestructural. The agricultural labour market had already been subjected to

BAS VAN BAVEL ET AL .

356

the forces of the market before 1350 and a legal tradition by which a classof agricultural employers exercised power over workers had never devel-oped in Holland. In the by-laws of the towns there are signs of labourshortages in the early fifteenth century. In Leiden (Leyden) in 1406, forexample, a by-law states that anyone, wherever he came from, would beallowed to work in Leiden (Leyden) for a servant’s or journeyman’s wage.However, compulsory labour was not the solution chosen by the auth-orities. Instead, they typically chose to open the market to immigrants.42

There are, of course, close connections between the protection ofproperty rights and the judicial system. In all three regions under studyguarantees of greater legal security developed in the course of the MiddleAges. In East Anglia, the main driving agent behind this development wasthe English Crown. The legal reforms of the Angevin kings, for instance,introduced new procedures, such as the Assize of Novel Disseisin, whichallowed dispossessed freeholders to take their case to a royal court andprovided speedy adjudication. Although royal justice put a check on thepower of the lords and clerics who dominated the local courts, it did not,however, abolish these courts : multiple jurisdictions continued to exist.Even if customary rights were not necessarily insecure, and manor courtsmay often have worked effectively, this system gave rise to a fragmentedregistration of property rights. Moreover, access to royal justice was notopen to everybody. Villeins who held their land from a manorial lordcould not seek redress against their lord in the king’s court ; they had toplead their case in the manorial court, in which that same lord held aprominent position.43

In Holland, justice, and the responsibility for the protection of propertyrights that came with adjudication, were shared from the beginning be-tween the state, represented by the Count of Holland and his governmentapparatus, and groups of subjects active in local administration. Thecornerstone of the judiciary system was a homogeneous layer of localcourts. In towns and villages representatives of local communities pre-sided over disputes involving criminal and civil law. Their sentences overtransactions involving land, capital, commodities and labour were exe-cuted by sheriffs and other government agents. As a result, disputes werehardly ever settled by other authorities, such as manorial and feudal lords,bishops and abbots.

The check on local judiciaries, that in England was achieved throughroyal justice, was in Holland realised through the possibility of appeal atregional courts, which were organised by bailiffs, and supreme courts inThe Hague and, from the fifteenth century on, also in Malines. Combinedwith occasional investigations into the functioning of the governmentapparatus, this system of appeal put a check on nepotism and corruption.

THE ORGANISATION OF MARKETS AND THE RISE OF HOLLAND

357

Supreme courts showed great concern for the costs of legal proceedings,and assisted people with modest means by having them represented bygovernment agents working free of charge.44 Some institutions specialisedin the quick resolution of disputes, their procedures not costing the liti-gants very much. An example in the capital market is the summary ex-ecution, whereby creditors could seek compensation for default withoutgoing through formal proceedings.45 Since similar capital markets, i.e.markets where long-term annuities were traded, did not exist in England,comparison is difficult. Still, it is our impression that institutions thathelped secure the investments of creditors also existed in England, butthat these seem to have been so rigorous that they discouraged debtorsfrom contracting mortgages. This was a major element that prevented theemergence of mortgage markets in England.46

Princely power certainly helped to create a relatively favourable situ-ation not only in Holland but also in several parts of the Low Countries.47

The legal framework in Holland stood out in one respect, though:whereas in other highly urbanised areas such as Flanders large parts of thecountryside were gradually subjected to urban jurisdictions, in Hollandrural courts managed to remain independent.48 Together with the insig-nificance of feudal authorities this contributed to the transparency ofthe juridical system and thus helped to keep the costs of civil proceedingslow.

3.2 The absence of extraction by force

The state could provide some vital economic institutions, but at the sametime it could well be a major threat to property rights. The purveyances ofvictuals that took place in late thirteenth- and early fourteenth-centuryEngland provide a good example. Peasants were forced to sell grain,livestock and other products to the king’s purveyors at prices that wereoften below market rates ; payment was, moreover, frequently deferredendlessly or even entirely. In peacetime the effects were limited, as pur-veyances mainly served to supply the royal household. However, thegeographical scope and the quantities requisitioned expanded signifi-cantly when military campaigns had to be prepared. Because of their richgrain fields and conveniently situated ports, the burden fell most heavilyon the eastern counties, including Norfolk and Suffolk. Lords and eccle-siastical institutions were often able to acquire an exemption; usuallypeasants were not, and suffered badly. Sources repeatedly refer to pea-sants being left impoverished and deprived of the corn needed for theirown sustenance, and they also mention forced sales of land after the oxenrequired for ploughing had been taken.49

BAS VAN BAVEL ET AL .

358

Even though the Counts of Holland frequently waged war, as with theconquest of the areas controlled by the high nobility and the regionof Westfriesland, they were not in a position to act in the same way.They lacked the power to impose similar exactions, either in the townsor in the countryside. Army provisions therefore had to be bought atregular market rates. The accounts of the preparations for the wars withthe Frisians around 1400 show that purveyors sent out by the count fre-quented urban markets in Holland, Utrecht and Guelders in order topurchase cattle and grain. The purveyors, well-to-do high-ranking offi-cials, were often expected to advance part of the expenses from their ownmeans for lengthy periods. Sometimes the sellers also had to wait for theirmoney. However, there is no evidence that compulsion was used to forcethem to sell.50

In the same vein, the English king frequently levied forced loans frommunicipalities and wealthier individuals throughout England, whereas theCounts of Holland seem to have lacked the necessary power to do this.Of course, the relative unimportance of forced loans also reflects thestrength of market structures ; particularly when the main towns under-wrote the debts, the Counts of Holland had little trouble in borrowing inthe capital market, and attracted credit not only from Holland, but alsofrom Brabant and Flanders. Therefore, on a local and central level there islittle evidence of this type of extra-economic pressure.51

Likewise, labour services to local lords and central authorities haddisappeared from Holland at an early stage. In medieval Europe, states orauthorities could commandeer labour not only for military purposes butalso for public works or other non-public goals.52 In Holland, however,the occurrence of corvee (forced labour) was rare and from the late four-teenth century onwards was restricted to exceptional occasions when waror severe flooding threatened.53

With respect to property rights to land, and the possible threat of ex-propriation, the situation in Holland was also favourable. Expropriationby the state was very rare. The reverse, that is, the state protecting peasantproperty rights and land, and disallowing their transfer to non-peasants,did not occur in Holland either, in contrast to Germany and France, forinstance.54 In these latter areas this policy was mainly dictated by the fiscalneeds of the state, since only peasant landownership could be taxed, whilethe land owned by religious institutions, noblemen and patricians wasoften exempted from taxes. In Holland, in contrast, these exemptions hadbeen abolished from the fourteenth century. After that, fiscal extractionno longer prompted authorities to intervene in the land market.

Similarly favourable conditions, with a near absence of non-economiccoercion, applied to the relationship between town and countryside.

THE ORGANISATION OF MARKETS AND THE RISE OF HOLLAND

359

In other regions, the accessibility of commodity markets was often severelyrestricted by trade monopolies. The effect is clearly visible in attitudestowards rural trade. In Flanders, for example, both the large cities and thesmaller towns claimed regional trade monopolies ; they required peasantsto bring grain and other victuals, but also the products of specialisedagriculture, such as dairy products, or those of rural industries, such aslinen cloth, to the urban market. Although not all towns were equallysuccessful in enforcing such regional monopolies, they were widespread.55

In Holland, there is little evidence of such monopolies. Some – but notall – of the small towns in the few grain-producing regions claimed amonopoly on the grain trade in their district.56 In addition, the countssometimes granted monopoly rights for strategic reasons to towns situ-ated near the border ; this was a way to gain the support of the urbanpopulation, establish their authority in a contested area, and prevent thetransfer of commercial activities and fiscal gains to neighbouring rulers.Geertruidenberg, on the Brabant border, is a good example. The earlythirteenth-century charter of liberties of this town, situated on the over-land trade route from Holland to the southern Low Countries, declaredit to be the compulsory cattle market for the entire rural region of Zuid-Holland.57 Still, such examples relate to a limited number of towns withspecific characteristics. Most towns simply did not possess the politicalpower needed for this kind of coercion.

The absence of coercive power of towns over the countryside inHolland also contributed, at the end of the fourteenth and the beginningof the fifteenth century, to the rise of a new type of rural trade venue,highly specialised in nature. On the North Sea coast informal beachmarkets for sea fish developed, and in the northern part of the countypublic weighing scales for dairy products emerged in several villages. Tomerchants these small-scale trade venues were convenient places for thepurchase of fish and dairy produce intended for urban markets inHolland, but also in the southern Low Countries, the eastern Netherlandsand the German Rhineland. Thus, fish markets and dairy scales providedfishermen and farmers with easy access to markets abroad.58

Just like their counterparts in Holland, English towns had, at most,very limited legal or political control over their hinterlands,59 but althoughurban domination of the countryside by way of non-economic means wasas rare in England as in Holland, informal trade venues in the Englishcountryside did not acquire the same strong position, probably becauselords maintained at least part of their traditional grip on commercial ac-tivities in the countryside.60

Moreover, urban markets in Holland were usually relatively open tooutsiders. In Flanders, and also in England, burghers or guild members

BAS VAN BAVEL ET AL .

360

who wanted to operate as traders in the local market were frequentlygiven priority over others. Downright exclusion was rare, but traders fromother towns or from the countryside usually had to pay more for access,or were forced to accept restrictions as to when, where and what theycould sell. In Holland limitations of this kind were uncommon.61

Coercive extraction by private persons or feudal powers was even moreconspicuously absent in Holland than extraction by central authoritiesand towns. From the reclamation and occupation in the eleventh to thir-teenth centuries onwards, Holland was populated by free peasants andburghers. Nobles and religious institutions were few and weak, and didnot possess the coercive power to extract surpluses. Further, manoriallords with a right to labour services and other types of extraction hadnever been prominent in Holland and had disappeared at an early stage.Freedom could also be obtained in the large reclamation areas. Thelatter also applied to Flanders, where the early rise of towns offeredan additional prospect of freedom. In England, however, and even in lessmanorialised Norfolk, many of the owners of large estates still used atleast some servile labour to cultivate their lands until the end of thefourteenth century. Villeins could use the manor court to protect theirproperty, and rights to customary land were generally secure,62 but villeinswere subject to manorial jurisdictions, could not defend their claims toland tenancy in royal courts and had to pay fees when they wished tomarry or to move away. Manorial lords could enforce their right to servilelabour at local and higher courts63 and although we should be careful notto paint too gloomy a picture, the long history of serfdom still may beassumed to have left its traces in social relations.64

4. EFFECT S OF INST ITUT IONAL DEVELOPMENT

Markets can be considered efficient when transaction costs are low. Lowtransaction costs reflect well-respected property rights and a high degreeof trust between parties, elements that reduce search and informationcosts, as well as the costs of protecting property rights and contracting.It is almost impossible to measure these transaction costs directly, exceptto some extent perhaps using interest rates as a direct indicator of theefficiency of the capital market.65 However, international comparisonsof interest rates for the medieval era are difficult to make because thefinancial instruments used to contract long-term loans differed markedly.Therefore we have opted for more indirect ways to test the quality andefficiency of markets. One approach is to focus on the relative size of thesemarkets; this is based on the assumption that greater dependency onmarkets can only exist where markets function adequately and are easily

THE ORGANISATION OF MARKETS AND THE RISE OF HOLLAND

361

accessible to large groups. Another is to investigate the integration ofmarkets, since this reflects the absence or presence of possible barriers.As mentioned earlier, interpretation is complex, because each of theseindicators may also be influenced by factors other than the quality of theinstitutional framework alone. Further, data are non-homogeneous anddispersed, making any advanced quantitative tests very difficult. Still, wethink the importance of the issue justifies taking this first step, that is,assembling the quantitative material and placing this in a comparativeperspective.

4.1 Volume

In Holland, the volume of capital, labour and commodity markets wasalready growing enormously in the late Middle Ages. There was, forinstance, a marked increase in long-term debt contracted by towns andvillages. Initially this type of funding was limited, since it was the privilegeof the Counts of Holland and some of the largest towns. However, fromthe end of the fourteenth century, other public bodies also began to par-ticipate in capital markets, and at the beginning of the sixteenth centuryall towns of Holland and 60 per cent of the villages had created long-termdebt, usually at interest rates just above 6 per cent.66 Towns elsewhere incontinental northwest Europe turned to capital markets as well.67 In EastAnglia, however, towns did not create similar long-term debt: the firstEnglish town to do so was London, at the end of the fifteenth century.68

The towns of Holland also managed to service a geographically highlydispersed public debt: they found creditors all over the Low Countries.Obviously, for foreign creditors to invest in public debt, and for Hollandtowns to contract and service it, efficient markets were a prerequisite.69

Since the fourteenth century private parties also contracted largenumbers of annuities. Many of these have survived, or are referred to inother sources.70 There is ample evidence suggesting that capital markets inHolland were accessible to large parts of the population. For instance, thetax registers of Edam show that a considerable proportion of the house-holds in this small town were either creditors or debtors for long termdebt: more than 30 per cent in 1462, a little over 20 per cent in 1514, andmore than 50 per cent in 1563. In the surrounding countryside figures werelower, but still significant, at 18, 5 and 23 per cent, respectively, in thesame three years. Due to some shortcomings of the source, these areminimum figures. Remarkably, we encounter many women among thecreditors and debtors.71 Broad access to capital markets for women is alsovisible elsewhere in the Low Countries.72 In England, access to capitalmarkets was poor in the countryside,73 for women and more generally, not

BAS VAN BAVEL ET AL .

362

least because of the low proportion of peasant landownership there andthe resulting impossibility of using land as collateral.

An estimate of the size of the rural labour market has been attemptedfor the sixteenth century.74 Around mid-century, almost half of all rurallabour in central Holland was performed for wages, most of it in proto-industrial activities. This is a very high share, compared for instance withinland Flanders where the figure was about 25 per cent. It is also far morethan the share of wage workers in the total rural population in variousEnglish regions, which amounted to between a quarter and a third in thesixteenth century. In Norfolk around 1525, for example, 20–35 per cent ofthe rural population consisted of wage labourers, a proportion which re-mained more or less constant throughout the sixteenth century.75

The significance of wage labour in the countryside and the high level ofurbanisation discussed earlier suggest that commodity markets were alsovoluminous. Moreover, agriculture was also highly market-oriented innature. While both in Flanders and in Suffolk subsistence farming con-tinued to exist side by side with commercial farming, in fifteenth-centuryHolland grain cultivation almost entirely made way for market-orientedcattle and dairy farming and the production of cash crops such as hempand hops.76 By the end of the Middle Ages a large share of Holland’slabour input – an estimated 90 per cent around 1500 – must have beendevoted to producing goods for the market,77 and by implication a largeshare of the population must have depended on the market for food andother basic necessities. Admittedly, this situation was affected by morethan just institutional factors. After about 1400, Holland had to importalmost all of its bread grains : wheat and rye could no longer be cultivatedon the subsiding peat soils. Nevertheless, the high level of commerciali-sation reached by 1500 would not have been possible without an efficientorganisation of markets to support it.

4.2 Integration

Judging by the interest rates, it seems that capital markets in Holland werewell integrated. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, large towns,small towns and villages paid about the same interest on long-term debtson average: 6.3, 6.4 and 6.5 per cent, respectively.78 Some regions withinHolland also show signs of integration, although interest rates in thenorth of Holland show a greater variation.79 In the small town of Edam,we can observe some other signs of market integration: the spread aroundthe mean for interest rates was remarkably small. In 1514, 61 per cent oflong-term loans carried an average interest rate of 5.6 per cent and in 1563this share was as high as 81 per cent of all loans.80 Variations between

THE ORGANISATION OF MARKETS AND THE RISE OF HOLLAND

363

town and countryside were also modest : in 1514 the average interest rateencountered in the town of Edam was 5.7 per cent and in the surround-ing areas 5.3 per cent; in 1564 the figures were 5.6 and 5.8 per cent,respectively.81

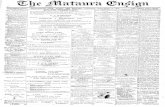

Commodity markets were also well integrated. Admittedly, on aregional level it is not surprising to find that grain prices in the lateMiddle Ages moved in concert ; this was common enough.82 However,an analysis of grain price movements in the early fifteenth centurysuggests that Holland stood out compared with commodity marketsabroad. Figure 1 relates the correlations between wheat prices inNoordwijkerhout, near Leiden, and prices in eight locations in thesouthern Low Countries, the eastern Low Countries, and England to thedistance from Noordwijkerhout to each of these locations. It does thesame for wheat prices in Bruges, in Flanders. Extending the comparisonwith East Anglia is unfortunately not possible. Reliable fifteenth-centurygrain price series for this region are not available and the well-knownLondon grain price series may not be representative, since – in contrastto some of the ports in Suffolk and especially to King’s Lynn inNorfolk – London did not have a significant grain trade with thecontinent in normal years.83

The analysis of grain prices in Bruges and Noordwijkerhout in Figure 1indicates the trend line for Noordwijkerhout lay at a higher level,

0.000

0.100

0.200

0.300

0.400

0.500

0.600

0.700

0.800

0.900

1.000

0

Distance (km)

Co

rrel

atio

n c

oef

fici

ent

NoordwijkerhoutBrugesTrendline NoordwijkerhoutTrendline Bruges

700100 200 300 400 500 600

F IGURE 1. Correlation coefficients of logs of annual average wheat prices in

Noordwijkerhout (in grams of silver per hectolitre) with prices in Bruges, Ghent, Brussels,

Louvain, Utrecht, Maastricht, London and Exeter, related to the distance from

Noordwijkerhout to each of these locations, 1410/1411–1439/1440, compared with identi-

cally calculated correlation coefficients of wheat prices in Bruges with prices in the eight other

locations. (Based on: Jessica Dijkman, Shaping medieval markets. The organisation of com-

modity markets in Holland, C. 1200 – C. 1450 (Leiden, 2011), 108–58.)

BAS VAN BAVEL ET AL .

364

suggesting that wheat markets in Holland were relatively well connectedto markets abroad. The flatness of the line indicates that these marketswere not only well integrated with foreign markets nearby, but also withothers further away. The links with these foreign markets can, moreover,not only be observed in times of dearth, but also in normal years.84

The driving force behind Holland’s international grain trade was nodoubt the demand for grains. However, if market structures had been lessfavourable, it is doubtful if it would have been possible to build up thesame robust and far-flung international trade network.

In Holland wage differentials between town and countryside weresmall. In inland Flanders, nominal wages in the countryside were stillclose to the urban rates in the early fourteenth century. However, in thelate fourteenth and fifteenth centuries urban wages were on average some50–70 per cent higher than the rural ones, perhaps because it was in thisperiod that urban and guild restrictions on immigration and entry intourban occupations became tighter, thus shielding off the urban labourmarket.85 In Norfolk, too, urban–rural wage differentials were quitenoticeable. In the late fifteenth century, wages were some 40 per centhigher for skilled and 60 per cent higher for unskilled labourers in urbanareas compared with rural, and around the middle of the sixteenth centurythe latter differential had risen to 60–90 per cent.86 In Holland, on theother hand, the urban–rural wage differences at the time were, and re-mained, very small, or were even absent altogether.87 For the fourteenthcentury, this can still be attributed to the small size of the towns, but afterthe dramatic growth of Holland’s towns in the fifteenth and sixteenthcenturies, this was no longer the case, suggesting that the absence ofinstitutional barriers was more important. Moreover, agricultural wageshad to compete with the many other wage-earning opportunities for themobile rural population, both in the countryside and in the towns. By1500, Holland seems to have had a highly integrated labour marketinvolving substantial seasonal migration of the rural work force in par-ticular.88

Furthermore, newcomers found the urban labour market highly ac-cessible. Guilds developed very late in Holland and did not acquire thepolitical role in urban government that their counterparts in Flandershad. Important towns such as Delft, Leiden, Haarlem, Alkmaar andHoorn did not acquire guilds until the first half of the sixteenth century, inreaction to the competition of crafts and proto-industries from thecountryside.89 Even then, guild ordinances only mildly limited the right toset up rural crafts and sell on the urban market, and did not attempt toregulate the availability or the price of labour. Guild ordinances thatcontain rules for the employment of live-in apprentices and journeymen,

THE ORGANISATION OF MARKETS AND THE RISE OF HOLLAND

365

let alone setting wages, are very rare before the late seventeenth century.Immigration was encouraged when labour ran short.

Theory predicts that favourable institutions reduce transaction costs.The indications of the impact of the institutional framework on marketperformance in Holland around 1500 show different results for the vari-ous types of markets. The performance of the lease market was probablyless than in the other areas. On the other hand, at the end of the MiddleAges grain markets in Holland were well integrated with markets abroad,and market orientation in Holland was very high. Further, the labourmarket was much more mobile and flexible than in the other regions, andthe capital market in Holland performed better than that in East Anglia,although differences between Holland and Flanders were probably muchsmaller. Of course, market performance was not exclusively determinedby institutions, but these differences point to differences in the institu-tional framework. We can surmise, therefore, that in Holland markets forgoods, and even more those for capital and labour, possessed a morefavourable institutional framework than the other parts of westernEurope. In trying to explain this, we will focus especially on the situationin Holland, leaving comparison with the other regions to future research.

5. A TENTAT IVE EXPLANAT ION OF FAVOURABLE AND

UNFAVOURABLE IN ST I TUT IONS

We suggest that the relatively favourable organisation of markets inHolland can be understood mainly from the absence of a feudal past andthe social structures that developed during the medieval period. This,as has been suggested by other authors, was vital to the economic devel-opment of Holland,90 but so far the implications for the institutionalframework have remained intuitive at best. Our research now shows howin this social context the foundations were laid for institutions whichfavoured market efficiency, thus providing a basis for acceleratedspecialisation and commercialisation when, at the end of the fourteenthcentury, a drastic economic transformation became necessary as a resultof ecological crisis.

5.1 Social developments

In the words of de Vries and van der Woude, Holland in the Middle Ageswas no ‘society of orders, where each member held a legally fixed positionassigned by birth’ ; barriers against social mobility were absent, encour-aging innovation and initiative.91 The origins of Holland’s weak feudalstructures are to be found in the process of land reclamation in the high

BAS VAN BAVEL ET AL .

366

Middle Ages. When settlers started to reclaim the extensive peatlandscovering most of Holland, from the tenth century onwards, the countsallowed them to create a society based on direct relations between rulerand subjects. The settler communities were incorporated into the fabric ofthe state. The settlers recognised the count’s supreme authority, paid taxesand served in the count’s army at his command, but were otherwise lar-gely free to run their own affairs. They organised themselves in publicbodies that took responsibility for taxation, public debt and public works.At the local level the count’s authority was represented by an appointedfunctionary, the sheriff. Thus a layer of local public bodies was created,characterised by broad participation but also by a balance of power : re-presentatives of the local elite had to collaborate with governmentagents.92

Towns only gradually developed, especially in the thirteenth and four-teenth centuries. This was later than in neighbouring areas such asFlanders and the Rhineland, and when village communities and princelyrule were already firmly established. The towns were numerous but small-or medium-sized; no large, dominant metropolis emerged. As a conse-quence, the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century counts were strong enoughto prevent the towns from extending their jurisdiction over the country-side. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries resistance by local lordsand village communities, and the competition between towns, helped tokeep urban greed in check.93 Moreover, rural organisations protectedvillages against urban ambitions, for instance by taking sides with locallords and filing legal procedures. As a result, unlike elsewhere, villagesmanaged to at least retain their level of public services and their self-organisation.94

5.2 Ecology

The process of land reclamation mentioned above had another crucialeffect in the long run. As the reclaimed peatland in Holland slowly startedto sink and became ever wetter, some of the peasants gave up agricultureand migrated to the towns, causing urbanisation to increase and urbanindustries to expand. The remaining peasants adapted to the new condi-tions: they gave up the cultivation of bread grains, which grew duringwinter when water tables were highest, and switched to summer grainsand livestock farming. They sold their output on the market ; growingurban markets no doubt contributed to the success of this agriculturaltransition.95 This favourable turn of events is certainly not self-evident : anecological disaster on this scale could easily have led to a general de-population. That this did not happen – in fact by the year 1400 the

THE ORGANISATION OF MARKETS AND THE RISE OF HOLLAND

367

population of Holland was almost back to pre-Plague levels – demon-strates the influence of pre-existing institutional arrangements: clearproperty rights and open and transparent factor and commodity marketsdiscouraged squeezing, stimulated a positive interaction between townand countryside and allowed Holland’s economy to adapt swiftly to thechanging circumstances.

A combination of ecological crisis, ample transport opportunitiesoffered by the many waterways, and favourable market organisation, allsuited the commercialisation and specialisation of the economy and theemergence of proto-industrial activities in Holland’s countryside.96 Thus,in the second half of the fourteenth century Holland witnessed a transitionto a heavily commercialised economy, with little to no subsistence farmingleft. Its population had to market butter, cheese, peat, bricks andother proto-industrial products to earn the money they required to buygrain that was imported from northern France and later from theBaltic. The switch to labour-extensive livestock farming also providedan impetus for labour markets: a large part of the rural population hadto look for additional employment, either in towns or as day labourersin rural proto-industries. Finally, capital markets may have receiveda boost when entrepreneurs started to seek funding to set up proto-industries.97

It is important to note that in both the urban and rural areas of Hollandthe tertiary sector developed rapidly. In 1514, only 25 per cent of labour inHolland was active in agriculture, supplying less than 20 per cent of grossdomestic product (GDP). If fishing and peat digging are included, theprimary sector still involved no more than 39 per cent of labour, gener-ating only 31 per cent of GDP. Industry accounted for 38 per cent of thelabour force and 39 per cent of GDP, and services for 22 per cent and 30per cent, respectively.98 A very large share of the region’s population wasactive in shipping and other transport services, retail, wholesale trade,measurement, or administration, whether in town or countryside. Theexceptional importance of the service sector in Holland was in part forcedby the ecological disaster, but it was also enabled by the flexible organis-ation of the labour and capital markets, and in its turn further stimulatedthese markets. This positive feedback cycle perhaps explains exactly whythese markets developed so favourably in Holland. It perhaps alsoexplains why the lease market in Holland lagged behind. Since this marketwas related to the relatively unimportant agricultural sector, and not tothe services sector, it was not part of this positive interaction betweeneconomy, market development and institutions. Moreover, the society offree peasants that emerged during this period was hostile to limited rightsto the land and remained so up to the sixteenth century. Only then, as

BAS VAN BAVEL ET AL .

368

peasant landownership was bought up by wealthy urban investors, didthis start to change. The absence of feudal power, the strength of hori-zontal associations and communities, the broad participation and thefragmentation of power all went back to the high Middle Ages and madetheir impact felt during the following centuries. As a result, except for thelease market, no social group in late medieval Holland was able to bendinstitutions to their own interests, not even in reaction to the catastrophesof the Black Death and the subsidence of the soil.

This situation did not last, however. From the end of the sixteenthcentury, this social balance was eroded in Holland. In the townsboth income and wealth inequality increased markedly between the mid-dle of the sixteenth and the middle of the seventeenth century.99 Thisprocess was even more pronounced in the metropolis of Amsterdam.100

Simultaneously urban governments and patriciates became increasinglyclosed, and barriers to citizenship were raised.101 Social polarisationwas also found in landownership. In the sixteenth and seventeenth cen-turies the small-scale peasant properties, so characteristic of Holland’scountryside, were consolidated into larger holdings by wealthy bur-gher–investors.102 The newly reclaimed polders, in particular, became theexclusive domain of patricians from the large towns and both materialand political inequality thus increased.

It can be speculated that the elite of merchant–entrepreneurs in theHolland towns, and especially in Amsterdam, used this economic andpolitical power to freeze or adapt market institutions to their own inter-ests. This can be observed in commodity market regimes. In the sixteenthcentury urban resistance to rural trade increased. For example, in 1515,the towns began pressuring the Habsburg government into banning ruraltrades and industries ; 16 years later, in 1531, Charles V issued an ordi-nance to this effect. To be sure, existing activities were usually left inpeace, so the towns’ victory was far from complete. Still, there can be nodoubt that urban policy towards rural commerce became increasinglyrestrictive.103 Further research is necessary in order to assess whether thisis representative of a more general development, and if the institutionalframework in Holland did indeed become less favourable in the latesixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

6. F INAL OBSERVAT IONS

Explaining the development of institutions and assessing their effects arenever easy tasks. The limited number of indicators for market efficiencyon which we focus does not solve all methodological problems, but webelieve that this approach allows institutional theory and empirical data

THE ORGANISATION OF MARKETS AND THE RISE OF HOLLAND

369

to be better linked, contributing to a better understanding of pre-moderneconomic development.

Our research shows, first, that in the late Middle Ages Holland didpossess a favourable institutional organisation of markets for labour andcapital, even compared with other advanced regions such as Flanders andEast Anglia: labour and capital markets in Holland were secure, open andflexible. Differences with respect to the commodity market were smaller,since this market had highly adaptive institutions that were introduced inall three regions. Holland’s lease market does not compare favourablywith those in the surrounding regions.

Second, our findings confirm that the organisation of markets is not theautomatic expression of a natural human drive to trade or make a profit.On the contrary, it is the result of very specific social conditions.Differences in these conditions result in markedly different organisationalarrangements, even between regions situated close to each other.Holland’s favourable institutional framework was rooted in the period ofland reclamation and occupation. In the high Middle Ages Holland wascolonised by free peasants under a territorial lord, creating a situation ofexceptional freedom and a near-absence of non-economic force, with thenobility gaining only a weak position, in contrast to most other parts ofwestern Europe. This allowed various other groups to organise themselvesand acquire a role in political decision-making. The resulting balance ofpower precluded dominance by way of non-economic power, provided acheck on rent-seeking, and ensured a positive role of the authorities in theshaping of market institutions.

Finally, the research shows that, in agreement with North’s theories,institutions did indeed contribute to Holland’s rapid commercialisation inthe late Middle Ages. It should be added that the institutional frameworkwas not the only cause; non-institutional factors, such as ecologicalproblems that made the cultivation of bread grain almost impossible, andthe favourable geographical location of Holland, played a part as well.However, favourable institutions facilitated an adequate response to op-portunities, ecological threats and external changes, thus allowing for astrong rise of markets and excellent market performance. The effect wasreinforced by the strong interaction between the various markets. Inparticular, the emergence of a well-functioning capital market enabledand reinforced the rise of land and labour markets. The resulting feedbackcycle in Holland was positive, speeding up the growth of markets. In itsturn this situation interacted with the real economy, and especially withthe rise of the tertiary sector, which benefited from the favourable capitaland labour markets, and probably stimulated their further development.By demonstrating the important role of institutions, this research thus

BAS VAN BAVEL ET AL .

370

reveals, at least in part, the roots of the Golden Age of Holland and thepath-dependent process that preceded it. However, we cannot rule out thepossibility that the favourable development of the organisation of mar-kets was in part the result of growth of markets and the economy, insteadof the cause. The debate about the causality is largely unresolved as yet ;at present the best guess is that the two processes interacted in a positiveway. However, such a positive interaction between institutional organis-ation and economic growth did not persist forever, as shown by thenegative changes in Holland from the late sixteenth century on. Perhaps inan earlier period the same applied to East Anglia, where positive devel-opments in the twelfth and thirteenth century were not fully sustained inthe following period. The present investigation was not able to clarifythese issues, as it was hampered by its limitation to the period after 1300,but future research perhaps will.

However limited this investigation may have been, it has illuminated atleast some institutional mechanisms in long-term development. In manyeconomies the institutional organisation of exchange played, and stillplays, a negative role, limiting or blocking economic growth. This re-search shows how difficult it is to break or change this institutional or-ganisation, since these institutions are hardly the result of rationaleconomic or social decision-making, but rather of existing social relations,the balance of power, custom and vested interests. The case of Hollandalso suggests that even in instances where market institutions hadfavoured economic growth these tend to petrify and become detrimentalif too much economic and political power is concentrated in the handsof a single group in society. This insight is important today, both fordevelopment economics and in the western world.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Bruce Campbell, Phil Hoffman, Maarten Prak, Jean-Laurent Rosenthal and the

participants at the Economic and Social History seminar at Utrecht University for their

comments on an earlier version of this paper.

ENDNOTES

1 D. C. North and R. Thomas, The rise of the western world. A new economic history

(New York, 1973).

2 Sheilagh Ogilvie, ‘Whatever is, is right? Economic institutions in pre-industrial

Europe’, Economic History Review 60 (2007), 649–84, here 668–71.

3 A notion more often found in work on political economy, and recently made again by

Ogilvie, ‘Whatever is, is right?’, 649–84.

4 Bas van Bavel, Tine de Moor and Jan Luiten van Zanden, ‘Introduction: factor mar-

kets in global economic history’, Continuity and Change 24, 1 (2009), 9–21.

THE ORGANISATION OF MARKETS AND THE RISE OF HOLLAND

371

5 Jan Luiten van Zanden estimates the tertiary sector at 22 per cent in 1514. J. L. van

Zanden, ‘Taking the measure of the early modern economy. Historical national ac-

counts for Holland in 1510/1514’, European Review of Economic History 6 (2002),

131–63, especially 138; see also B. J. P. van Bavel, ‘Early proto-industrialization in

the Low Countries? The importance and nature of market-oriented non-agricultural

activities in the countryside in Flanders and Holland, c. 1250–1570’, Revue Belge de

philologie et d’histoire 81 (2003), 1109–187, especially 1143.

6 B. J. P. van Bavel, ‘Rural wage labour in the in the sixteenth-century Low Countries.

An assessment of the importance and nature of wage labour in the countryside of

Holland, Guelders and Flanders’, Continuity and Change 21, 1 (2006), 37–72, especially

62–3.

7 B. J. P. van Bavel and J. L. van Zanden, ‘The jump-start of the Holland economy

during the late-medieval crisis, c. 1350–c. 1500’, Economic History Review 57, 3 (2004),

503–32.

8 North and Thomas, The rise of the western world, 132–45.

9 J. de Vries and A. M. van der Woude, The first modern economy: success, failure and

perseverance of the Dutch economy, 1500–1815 (Cambridge, 1997), 159–65.

10 These investigations were part of the research project ‘Power, markets and economic

development: the rise, organisation and institutional framework of markets in Holland,

eleventh–sixteenth centuries’. The project was carried out at Utrecht University,

2001–2007 (funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO),

directed by Bas van Bavel).

11 B. M. S. Campbell, ‘Factor markets in England before the Black Death’, Continuity

and Change 24, 1 (2009), 79–106.

12 For an overview, see Van Bavel and Van Zanden, ‘The jump-start’, 505; and P. C. M.

Hoppenbrouwers, ‘Van waterland tot stedenland. De Hollandse economie ca. 975–ca.

1570’, in T. de Nijs and E. Beukers, Geschiedenis van Holland, I, Tot 1572 (Hilversum,

2002), 103–48, especially 136.

13 Van Bavel and Van Zanden, ‘The jump-start’.

14 W. P. Blockmans, G. Pieters and W. Prevenier, ‘Het sociaal-economische leven

1300–1482. Tussen crisis en welvaart. Sociale veranderingen 1300–1500’, in D. P. Blok,

W. Prevenier and D. J. Roorda eds., Algemene Geschiedenis der Nederlanden IV

(Haarlem, 1982), 42–86, here 43–6.

15 M. Bailey, Medieval Suffolk. An economic and social history, 1200–1500 (Woodbridge,

2007), 129, 149–51. Chris Dyer gives the slightly lower figures of 14 and 27 per cent,

respectively; see C. Dyer, ‘How urbanized was medieval England?’, in J.-M.

Duvosquel and E. Thoen eds., Peasants and townsmen in medieval Europe. Studia in

honorem Adriaan Verhulst (Ghent, 1995), 169–83. No similar calculations are available

for Norfolk.

16 Bailey, Medieval Suffolk, 67 and 183–4. Population developments in Norfolk display a

similar trend. See Jane Whittle, The development of agrarian capitalism. Land and labour

in Norfolk, 1440–1580 (Oxford, 2000), 175–6.

17 Bailey, Medieval Suffolk, 265–6.

18 Campbell, ‘Factor markets in England’; and B. J. P. van Bavel, ‘The land market in the

North Sea area in a comparative perspective, 13th–18th centuries’, in S. Cavaciocchi

ed., Il mercato della terra secc. XIII–XVIII. Atti delle ‘‘Settimane di Studi ’’ e altri con-

vegni 35 (Prato, 2003), 119–45.

19 Whittle, The development, 93 and 99. See also below pp. 355–359.

20 Van Bavel, ‘The land market’, 129–32; also for the following, and for Norfolk, see

Whittle, The development, 31 and 76–82.

BAS VAN BAVEL ET AL .

372

21 B. J. P. van Bavel, ‘The emergence and growth of short-term leasing in the Netherlands

and other parts of northwestern Europe (11th–16th centuries). A tentative investigation

into its chronology and causes’, in B. J. P. van Bavel and P. Schofield eds., The rise of

leasing. CORN Publication series 10 (Turnhout, 2009), 179–213.

22 C. J. Zuijderduijn, Medieval capital markets. Markets for renten, state formation and

private investment in Holland (1300–1550) (Leiden/Boston, 2009), 184–90.

23 P. R. Schofield, ‘Access to credit in the early fourteenth-century English countryside’,

in P. R. Schofield and N. J. Mayhew eds.,Credit and debt in medieval England c. 1180–c.

1350 (Oxford, 2002), 106–26, especially 119.

24 Many of these pamphleteers pressed for the adoption of registration systems found in

Holland and elsewhere in the Dutch Republic. An overview of this literature is given in

‘Publications on registering deeds of land’, The Legal Observer or Journal of

Jurisprudence 1 (1831), 234; and ‘The registry question in former times’, The Jurist or

Quarterly Journal of Jurisprudence and Legislation 4 (1833), 26–43.

25 T. de Moor, J. L. van Zanden and J. Zuijderduijn, ‘Micro-credit in late medieval

Waterland. Households and the efficiency of capital markets in Edam en De Zeevang

(1462–1563)’, in S. Cavaciocchi ed., The economic role of the family in the European

economy from the 13th to 18th centuries (Florence, 2009), 651–68.

26 Martha C. Howell, The marriage exchange: property, social place, and gender in cities of

the Low Countries, 1300–1550 (Chicago, 1998), 202–3; Jane Whittle, ‘Inheritance,

marriage, widowhood and remarriage: a comparative perspective on women and

landholding in north-east Norfolk, 1440–1580’, Continuity and Change 13, 1 (1998),

33–72.

27 M. Bailey, ‘Villeinage in England: a regional case study, c. 1250–c. 1349’, Economic

History Review 62, 2 (2009), 430–57, here 433–5.

28 David Nicholas, Medieval Flanders (London, 1992), 106.

29 Hoppenbrouwers, ‘Van waterland tot stedenland’, 137.

30 Bailey, Medieval Suffolk, 197, 199.

31 J. Hatcher, ‘England in the aftermath of the Black Death’, Past and Present 144 (Aug.

1994), 3–35; Elaine Clark, ‘Medieval labor law and English local courts’, American

Journal of Legal History 27 (1983), 330–53; and on sixteenth-century legislation, see

D. Woodward, ‘The background to the statute of artificers: the genesis of labour pol-

icy, 1558–63’, Economic History Review 33, 1 (1980), 32–44.

32 In Flanders run-aways could count on a whipping, see the ordinances of

Hulsterambacht 1440 and 1546, Bosch, ‘Rechtshistorische aanteekeningen’, 384, Also

a Brabant by-law from 1587 states that a servant that breaks his contract will be sub-

mitted to criminal law: Ibid., 382.

33 J. W. Bosch, ‘Rechtshistorische aanteekeningen betreffende de overeenkomst tot het

huren van dienstpersoneel ’, Themis: regtskundig tijdschrift 92 (1931), 355–418 and 93

(1932), 23–92 and 215–77.

34 Bosch, Themis 92, 355–418.

35 Bailey, Medieval Suffolk, 184–93; Whittle describes the enforcement of labour laws in

Norfolk: see The development, 287–96.

36 J. L. Bolton, The Medieval English economy, 1150–1500 (London, 1980), 213; see

also Samuel Cohn, ‘After the Black Death: labour legislation and attitudes towards

labour in late-medieval western Europe’, Economic History Review 60, 3 (2007),

457–85; L. R. Poos, ‘The social context of the Statute of Labourers Enforcement’, Law

and History Review 1 (1983), 27–52, here 34–7; Clark, ‘Medieval labor law’, 330–53.

37 Whittle, The development, 294.

38 Ibid., 295.

THE ORGANISATION OF MARKETS AND THE RISE OF HOLLAND

373

39 Woodward, ‘The background to the Statute of Artificers’.

40 Cohn, ‘After the Black Death’.