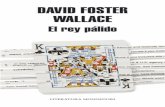

The Mythic Character of the Mundane in the Later Fiction of David Foster Wallace

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of The Mythic Character of the Mundane in the Later Fiction of David Foster Wallace

1

James ShapiroFinal Paper

ENG 187 IrrNovember 27, 2012

The Mythic Character of the Mundane in the Later Fiction of David Foster Wallace

Biographer D.T. Max has characterized David Foster Wallace as a practitioner of fictional

realism in an “increasingly unreal world.” Though it’s not entirely clear what Max means by this phrase,1

I think it must have a lot to do with Wallace’s insistent focus on basic human anxieties and emotions in

the face of gigantic cultural systems that threaten to swallow the individual. This concern is

communicated in his late works Oblivion and The Pale King through a kind of mythological treatment

of the mundane a hyperdramatic depiction of unremarkable characters doing mostly unremarkable

things, largely revolving around the experience of their professional lives. Though Wallace was a noted

critic of the contemporary pervasiveness of irony, which he deemed “relentlessly... corrosive to the

soul,” I propose that this dramatic treatment of mundane subject matter results in the creation of a2

unique brand of darkly comic satire (if only ‘satire’ for lack of a better word; it applies much more

accurately to “The Suffering Channel,” which clearly has elements of absurd humor, than it does to

“Good Old Neon,” for example). In this study I will be exploring this technique of Wallace’s which I

will be referring to repeatedly in some form or another as ‘the mythic treatment of the mundane’

specifically with regard to the frequently repeated theme of the essential meaninglessness and tedium of

present day, white collar labor (which Wallace focuses on extensively, perhaps to reflect the enormity of

its role in the definition of many middle/upper class lives in the absence of meaning found in the

1 Max, speaking at Harvard University, December 10, 2012.(Similar phrasing here: http://untitledbooks.com/features/features/ameaningfullifebydtmax/)2 Interview with NPR’s Steve Paulson, June 17, 2004.

2

traditional sources, such as religion and community). Finally, I will argue that Wallace wrote of an

intense white collar suffering due to what he perceived as that group’s inability to reconcile their lofty

professional and personal ambitions (egoideal) with the reality of the labor experience of contemporary

life.

That (at least white collar) labor in the ephemeral, service/informationbased economy of our

time is, more often than not, both meaningless and tedious seems to be presented as a necessary fact of

life in Wallace’s fiction (it seems obligatory to mention, if only in passing, that any discussion of the

experience of labor seems to be rooted in Marx’s idea of ‘alienated labor.’ This idea, which was

developed in the context of extremely poor factory workers, makes an interesting juxtaposition with the

fierce brand of white collar suffering found in Wallace’s writing, and in the concept of “bourgeois

problems” generally). In his 1961 work Growing Up Absurd, Paul Goodman posited that a rise in

gang violence was brought on by the increasing lack of the possibility for finding what he termed as

“man’s work,” which is to be understood as work that is intrinsically valuable both to the laborer

performing it and to others who consume or benefit from said labor. Goodman rightly pointed out that

the shift to a servicebased economy resulted in the disappearance of what is referred to in cliche as

‘good, honest work.’ Looking back on it now in the midst of a recession, the problem which Goodman

described was, ironically, largely one of abundance:

It’s hard to grow up when there isn’t enough man’s work. There is ‘nearly full employment’...but there get to be fewer jobs that are necessary or unquestionably useful... To producenecessary food and shelter is man’s work. During most of economic history most men havedone this grudging work, secure that it was justified and worthy of a man to do it.3

Though Wallace also wrote in a time of prosperity, he wrote about a different socioeconomic class than

3 Goodman, Paul. Growing Up Absurd. New York: Vintage, 1961. p. 8.

3

the one which Goodman was analyzing. Whereas Goodman was offering an explanation for the

rejection of mainstream values by poorer youths on society’s fringes, Wallace’s characters are, for the

most part, children of privilege. Rather than falling victim to ‘underemployment,’ the representative

problem of the welleducated in today’s recession,Wallace’s characters have largely achieved their

ambitions, yet are either acutely aware that their labor experience is not what they imagined, or are

essentially lying to themselves by creating a meaning where there is none.

An explanation proposed in “Mister Squishy” is that the world is simply too big, the systems too

complex, the competition too fierce and many. That story’s main character, T.E. Schmidt, looks back

on his youthful ambition to “make a difference” in his field cringingly, observing that the phrase itself is

now reduced to an advertising slogan (ironically, the field that he works in/with) and not possible in

reality. The narration tells us that Schmidt fantasizes about being close enough to someone to “[sob] in

each other’s arms late at night and [pour] out the most ghastly private fears and thoughts of failure and

impotence and thoroughgoing smallness within a grinding professional machine you can’t believe you

once had the temerity to think you could help or change or make a difference or ever be more than a

faceless cog in” (32). The tedium and repetition of Schmidt’s occupation as Targeted Focus Group

Facilitator for a wellregarded marketing research firm is communicated in the very first line of the story:

“The Focus Group was then reconvened in another of Reesemeyer Shannon Belt Advertising’s

nineteenthfloor conference rooms” (3, emphasis mine). The use of the words ‘then’ and ‘another,’ and

the fact that the story seems to pick up in medias res as if this is a perpetually repeated cycle

communicate a monotony and spiritual barrenness in Schmidt’s work.

In “Good Old Neon,” Neal searches for a way out of his “fraud paradox” in some traditionally

4

comforting/meaningful institutions: the capitalist labor force (like Schmidt, he works in the marketing

industry, which is of particular significance as not just a part of the corporatedriven consumer culture,

but an engine of it) Christianity (a charismatic church), psychotherapy, and a commercialized form of

Eastern meditation. One by one, these potential narratives of salvation are eliminated. Similarly, in “The

Suffering Channel,” Skip Atwater’s serious dedication to his work in human interest journalism which

is largely considered nothing more than a punchline dramatizes his continued struggle to find meaning

and fulfill his potential. We learn that when, early in his career, Atwater was told by an editor that he

didn’t have what it takes, “[he] had literally run for the privacy of the men’s room and there had struck

his own chest with his fist several times because he knew that at heart it was true...” (270). The editor’s

pronouncements about Atwater are satirical in tone, because we might expect a journalist judged that

way to be relegated only to human interest stories rather than, say, international relations. Yet Atwater

is told that “[he] had no innate sense of tragedy or preterition or complex binds or any of the things that

made human beings’ misfortunes significant to one another... Atwater could write a sweet commercial

line... [and] had compassion, of a certain frothy sort, and drive” (270). The very nature of human

interest reporting is, in fact, finding the mythic aspect of the mundane (turning everyday, ‘ordinary’

people into headlines), as we can see from the titles of Atwater’s pieces: “He Delivers 81 year old

obstetrician welcomes the grandchild of his own first patient... Today’s forest ranger: He doesn’t just sit

in a tower,” etc. (299).

The main subject of “The Suffering Channel” that is, a man whose bowel movements are

intricate reproductions of well known works of art and images from popular culture, as well as many

side conversations about feces is hard to make sense of. On one hand, it seems like the same

5

celebration of the most basic elements being human as seen in Rabelais; on the other, a multifaceted

indictment of contemporary culture: that a journalist would so enthusiastically pursue a story about a

man’s excrement, and also that that man’s ‘occupation,’ if we can call it that, is more real and

meaningful than the journalist’s. Parallel to Moltke’s storyline is Wallace’s relation of reality television’s

logical conclusion: celebrities on the toilet, celebrity autopsies, and footage of unspeakable horrors. In a

sense, the concept of The Suffering Channel is an attempt at the same type of empathy which Wallace’s

characters and his stories themselves seek to achieve, but an attempt that is ultimately misguided and

terribly degrading to humanity.

What I have dubbed Wallace’s endowment of mundane aspects of life with a mythic character

seems to be most essential to The Pale King, a novel about IRS accountants who become so bored

that they imagine seeing the ghosts of past employees. Wallace was an outspoken critic of irony as a

mode of expression; an oftquoted line from his essay “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction”

reads:

And make no mistake: irony tyrannizes us. The reason why our pervasive cultural irony is atonce so powerful and so unsatisfying is that an ironist is impossible to pin down. All U.S. ironyis based on an implicit "I don’t really mean what I’m saying." So what does irony as a culturalnorm mean to say? That it’s impossible to mean what you say? That maybe it’s too bad it’simpossible, but wake up and smell the coffee already? Most likely, I think, today’s irony endsup saying: “How totally banal of you to ask what I really mean.”4

I’m really not sure how statements like this one gel with what Wallace did in The Pale King, much of

which seems to be characterized by a certain brand of darkly comic satire. For example, one character

recalls the epiphanous moment when he knew that he wanted to work for the IRS. After mistakenly

4 Wallace, David Foster, E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction , Review ofContemporary Fiction, 13:2 (1993:Summer) p.151 http://jsomers.net/DFW_TV.pdf

6

stumbling into an “Advanced Tax” class in college, he stays initially because he is too embarrassed to

leave, but soon becomes enthralled by the material, and thoroughly impressed by the precise and careful

demeanor of the students and especially the professor. It happens to be the last class of the semester,

and the professor delivers powerful closing remarks at the end of the period:

I wish to inform you that the accounting profession to which you aspire is, in fact, heroic...Enduring tedium over real time in a confined space is what real courage is... True heroism isyou, alone, in a designated workspace. True heroism is minutes, hours, weeks, year upon yearof the quiet, precise, judicious exercise of probity and care – with no one there to see or cheer.This is the world... You have wondered, perhaps, why all real accountants wear hats? They aretoday’s cowboys. As you will be. Riding the American range. Riding herd on the unendingtorrent of financial data... Gentlemen, you are called to account (228233).

I don’t doubt that Wallace really did believe in a kind of heroism of the bureaucrat, and by calling The

Pale King satirical I don’t mean to say that he was in some way mocking office workers. As I

suggested previously, the function of the satire here seems to be a reflection of the absurdity of

contemporary labor and the ways in which people cope with essentially empty lives. The IRS workers

depicted have no choice but to embrace “soullevel boredom” and rote tedium, which for some allows

for the attainment of a sort of transcendent consciousness. One character, Lane Dean, Jr., is visited by

the ghost of a former return handler who gives him a minilecture on the history and etymology of the

word ‘boredom’: “In fact the first three appearances of bored in English conjoin it with the adjective

French, that French bore, that boring Frenchman, yes? The French of course had malaise, ennui...”

(383). Another character is described as being able to physically levitate and hover over his chair when

he is able to concentrate particularly intensely on his daily tasks.

Stylistically, Wallace makes use of intentionally tedious prose to communicate the experience of

the IRS workers. I want to go slightly beyond the obvious fact that Wallace wrote these stories to read

7

tediously in order to reflect the tedium inherent in the kind of labor (and lives) he was describing, to

assert that Wallace forces the reader to engage in a sort of empathetic performance in the act of

reading. We don’t merely relate to characters through an understanding of the boredom they face day in

and day out, but we experience it along with them. Maybe the distinction isn’t as dramatic as I’m

imagining, but the performative aspect seems to me important to stress. I have in mind here instances

like the sequence in The Pale King when, for several pages, all that Wallace gives us are descriptions

of different characters in the office turning pages of the documents they are reading. Of course, as one

might imagine, the use of technical tax jargon is also a large part of how this tedium is cultivated in The

Pale King.

On the same token, “Oblivion,” while not directly dealing with labor per se, is written in prose

that is reflective of a professional and bureaucratic sensibility. The story’s multitude of Latin phrases and

its extremely meticulous, investigative reportage of minute details make it read at times like a legal brief,

at times like a medical report (the latter being perhaps a stylistic echo of the ‘somnology’ study in which

Hope and Randall engage at the clinic in Hope’s dream). One might initially think while reading the story

that this narrative style is reflective of the language which Randall uses in his work as some sort of

systems analyst (it’s not entirely clear), and the types of technical reports he might write in that capacity.

This interpretation is not entirely undercut when the story’s climax reveals that it is in fact Hope

inhabiting, in some way, Randall’s consciousness, or more accurately, what she dreams Randall’s

consciousness to be like. Then, the technical language of the narration becomes Hope’s imagining of

Randall’s workwarped way of thinking; as Paul Giles notes, Randall “compares [the sleep pattern

charts the somnologists give him] to the cash flow graphs he scrutinizes by day” (Giles, 339).

8

A professional sensibility and (in this case marketing industry) jargon characterize the style of

“Mr. Squishy,” as well. Specialized nomenclature such as ‘Targeted Focus Group,’ ‘Unintroduced

Assistant Facilitators,’ and their corresponding abbreviations and acronyms (as well as other acronyms

which are never explained), indicate that we are seeing the world on terms wholly constructed by a

corporate entity. Even time itself is experienced on the terms of the capitalist machine; past events are

marked not by months or years but by earnings periods: “Darlene Lilley... had, three fiscal quarters past,

been subjected to unwelcome sexual advances...” (15), and “Robert Awad himself... had performed

this little trick in one of his orientation presentations for new field team researchers 27 fiscal quarters

past” (22). Relatedly, the story seems to contain an implicit threat of the corporate coming to define all

people in one of those ‘there are kinds of people in this world’ dichotomies: either as reduction to

consumer demographic information (“Precisely 50% of the room’s men wore coats and ties or had

suitcoats or blazers hanging from the back of their chairs... another three men wore combinations of knit

shirts, slacks, and various crew and turtleneck sweaters classifiable as Business Casual... All three of

these youngest members[’] faces [were] arranged in the mildly sullen expressions of consumers who had

never once questioned their entitlement to satisfaction or meaning.” [910]) or as agents of the

corporate capitalist machine itself. We are told that Schmidt feels “as if merely being employed ... in the

great grinding US marketing machine had somehow colored his whole being” in the eyes of others (25).

He sees himself this way in his own eyes as well literally:

Sometimes... [Schmidt] would look at his face and at the faint lines and pouches that seemed togrow a little more pronounced each quarter and would call himself. directly to his mirrored face,Mister Squishy, the name would come unbidden into his mind, and despite his attempts toignore or resist it the large subsidiary’s name and logo had become the dark part of him’s latesttaunt, so that when he thought of himself now it was as something he called Mister Squishy, andhis own face and the plump and wholly innocuous icon’s face tended to bleed in his mind intoone face, crude and linedrawn and clever in a small way, a design that someone might find

9

some small selfish use for but could never love or hate or ever care to truly even know (3334).

“Mr. Squishy’s” Darlene Lilley has been vaguely alluded to, but what, we should ask, do we

make of Wallace’s female characters generally? Paul Goodman’s terminology (“man’s work”) reflects

the fact that he was speaking specifically to the condition of alienated young men, but of course women

in today’s workforce face the same challenge. “Man’s work,” though, seems an interestingly

appropriate term in the context of Wallace’s fiction the women in his stories seem to be more

welladjusted and content with the labor roles in which they find themselves than their male

counterparts. Though not without their anxieties and problems, the Style interns in “The Suffering

Channel”, all of whom are female, come off as more functional and comfortable (evidenced largely by

their sense of humor) than seemingly all notable male characters in the collection, Yet however

successful these young women are in their chosen field, there seems to be a subtle but powerful sense in

which the narration laments the fact that such highly intelligent and motivated people are working in such

a relatively pointless pursuit (along with being another manifestation of Wallace’s affinity for using very

specific local places and names, this seems to be a plausible explanation for the several references to

Swarthmore and Wellesley).

Ironically, though, being more welladjusted to labor which is characterized as meaningless and

oppressive seems to indicate weakness or simplemindedness on the part of the women. Having said

that, I don’t think Wallace is necessarily making this value judgment, but rather seems to echo an idea

like Goodman’s, in which men seem somehow more dependent on their labor roles for the construction

of their identity, or for a kind of validation of self as ‘man’ perhaps as provider; agent of influence and

change. Maybe I’m being too generous in imagining minimal sexism on Wallace’s part here, but this

10

subscription (by both sexes) to an antiquated and obsolete picture of gender roles could be an

explanation of why Wallace’s men often appear to suffer so much more acutely than do his women.

Perhaps, also, the gender playing field is somehow leveled by the imminent spectre of death: the setting

of 1 World Trade Center Plaza, just before the September 11 attacks, and Wallace’s explicit

mentioning of their coming (“the tragedy by which Style would enter history two months hence” [245];

“[Ellen Bactrian] had ten weeks to live” [326]) makes the reader wonder if these characters would be

doing what what they’re doing, working where they’re working, if they knew their time was so short.

Paul Giles writes that this “lends Wallace’s narrative, albeit in an oblique and understated way, a

structure of overarching dramatic irony, where the reader gradually becomes aware of the characters

being caught up in labyrinthine systems of which they necessarily remain largely unaware” (Giles,

3389).

It is striking that several of the stories in question are narrated in some form of fictional

autobiography. Wallace’s extensive use of this technique seems to be an exploration of the extents and

limits of empathy in a world in which we are essentially solipsistic and deeply lonely. Wallace was

interested in a very simple and basic yet utterly important idea: something like an ‘ineluctable modality’

of the centrality of self in everyone’s consciousness::

... everything in my own immediate experience supports my deep belief that I am the absolutecenter of the universe; the realest, most vivid and important person in existence. We rarely thinkabout this sort of natural, basic selfcenteredness because it's so socially repulsive. But it's prettymuch the same for all of us. It is our default setting, hardwired into our boards at birth. Thinkabout it: there is no experience you have had that you are not the absolute center of. The worldas you experience it is there in front of YOU or behind YOU, to the left or right of YOU, onYOUR TV or YOUR monitor. And so on. Other people's thoughts and feelings have to becommunicated to you somehow, but your own are so immediate, urgent, real.5

5 Wallace, speaking at Kenyon College, May 21, 2005.http://moreintelligentlife.com/story/davidfosterwallaceinhisownwords

11

It is precisely the tension between this fact of our experience of the world and our being thrust into vast

systems in which we are “faceless cogs” that creates the kind of existential suffering which Wallace

relates. No matter how pervasive and important to our lives these systems of labor, corporate

capitalism, media, and technology become, the immediacy of ourselves consciousness never fades. This,

I would argue, explains Wallace’s reverent treatment of the mundane biographical details of his

characters and the creation of a kind of personal lore (things like Chris Fogle’s deciding whether or not

to study or drink based on which way a spinning sign for a nearby podiatrist’s office stops at closing

during college in The Pale King, or Neal’s “getting to second” with “[the second or third] most

desirable [girl] in middle school that year” in “Good Old Neon” [142]). Paul Giles, who refers to

Wallace’s practice of maintaining the primacy of the individual as “Sentimental Posthumanism,”

describes the idea this way:

... rather than allowing his characters to simply to become swamped by mass culture, Wallace’sfiction seeks to construct a more affective version of posthumanism, where the kind of flattenedpostmodern vistas familiar from the works of say, Don Delillo are crossed with a moretraditional investment in human emotion and sentiment.6

Giles might have had Underworld, a novel which jumps back and forth between dozens of characters

without ever really offering any insight into their inner lives (especially compared to the degree which

Wallace does), in mind. Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, which focuses on a surreal hyperconnection

of people and systems rather than individuality, may also be a useful contrast. But at any rate, I wish

now to explore the implications of this primacy of the self on empathy through a look at Wallace’s

6 Giles, Paul: Sentimental Posthumanism: David Foster Wallace. p. 330.Twentieth Century Literature. Vol. 53, No. 3, After Postmodernism: Form and History in ContemporaryAmerican Fiction (Fall, 2007), pp. 327344 Published by: Hofstra University.Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20479816

12

interesting narrators and narratorial devices.

In the case of both “Good Old Neon” and “Oblivion,” there are two layers of fictional

autobiography; that is to say, what we think is one character’s autobiographical expression is in fact

revealed to be only another person’s attempt at imagining said character’s interior life. “Good Old

Neon” is putatively told from beyond the grave by the main character Neal, who has committed suicide,

but it is revealed at the end of story that a fictional David Wallace, Neal’s high school classmate, has

imagined the entire narrative (the explanation of which also sheds light on the problem of empathy):

... in other words David Wallace trying, if only in the second his lids are down, to somehowreconcile what this luminous guy had seemed like from the outside with whatever on the interiormust have driven him to kill himself in such a dramatic and doubtlessly painful way—with DavidWallace also fully aware that the cliché that you can't ever truly know what’s going on insidesomebody else is hoary and insipid and yet at the same time trying very consciously to prohibitthat awareness from mocking the attempt or sending the whole line of thought into the sort ofinbent spiral that keeps you from ever getting anywhere” (181).

Similarly, in “Oblivion,” as alluded previously, goes from the apparent narrative of a husband talking

about his wife to the revelation that the narrative was actually a dream of the wife’s explaining the

interjections of words like “Up!” as the husband’s attempts to wake Hope seeping into her dreaming

consciousness. This frame through which the preceding story was told may provide an explanation for

the nearconstant use of singlequotes around words, indicating that they are parrotings of the phrasings

of others, or attempts to convey the thoughts of others perhaps subtly foreshadowing the fact that the

entire narration is Hope’s subconscious attempt to reproduce Randall’s point of view (echoing the

inability to understand the inner lives of others as put forth in “The Soul is not a Smithy”). Another

interesting implication of the story being Hope’s dream is that the repeated mention of “voluptuousness”

that Hope had lost hers, that Audrey’s friends were more voluptuous than she, etc. become not

13

Randall’s lamentations but rather the manifestations of Hope’s own insecurities.

“Mr. Squishy” falls into a similar but distinct category. Although the narration seems at first to

emanate from an omniscient thirdperson, it is revealed that the narrator is in fact a character within the

story: “I was one of the men in this room, the only one wearing a wristwatch who never once glanced at

it” (14). Also at this same moment an instance of ‘the mythic in the mundane’ emerges, in the (newly

revealed to be present within the story) narrator’s description of his purpose, or role, in the conference

room:

What looked just like glasses were not. I was wired from stem to stern. A small LCD at thebottom of my right scope ran both Real Time and Mission Time. My brief script for the GRDScaucus had been memorized in toto but there was a backup copy on a laminated car just insidemy sweater’s sleeve, held in place with small tabs I could release by depressing one of thebuttons on my wristwatch, which was not really a watch at all. There was also the emeticprosthesis. The cakes, of which I had already made a show of eating three, were so sweet theyhurt your teeth (14).

This mystery around the narrator helps create an intensely paranoid vision of corporate culture: though

it’s up for debate, my best guess is that the narrator is sent to spy on Schmidt, either by a rival research

firm or corporation (in order to learn Schmidt’s trade secrets), or that he is another employee of Team

y, (in this case in order to ensure that Schmidt’s performance is up to snuff). Presumably, this

surveillance extends past work hours, or at least such is a plausible explanation of the narrator’s intimate

knowledge of Schmidt’s life and seeming insight into his thoughts. It may not, however, provide any

explanation for why the narrator is also aware of all the goings on outside, the reaction of the crowds,

etc. It has been speculated that the narrator is working in concert with the ominous figure scaling the

building to commit some act of terror. While there is certainly a threatening aspect to the climber, who is

said to have what looks like an automatic rifle or a “flamethrower,” I don’t think it’s out of the question

14

that he is yet another corporate spy, either also gathering data on Schmidt, or observing the narrator.

Either of these explanations would add to the labyrinthine (to borrow Giles’s term) sense of the

corporate system. Whether this is the case or the scaling figure’s equipment is actually weaponry,

Wallace is again bringing the everyday into the realm of the absurd, or sensational. In the terrorist

scenario, it seems something like the dramatic irony of the 9/11 spectre in “The Suffering Channel” is

achieved, whereas the spy scenario casts the corporate world in terms of cold war espionage. An

author named Blake Butler suggests an interesting possible wrinkle: that the climbing figure who is

said in the text to inflate parts of his suit, creating strange effects of deformity in fact turns himself into

a giant Mister Squishy. This fits with one of the interpretations that’s actually offered within the text; that7

the climber is part of an elaborate marketing campaign. Alternatively, this would also be a powerful

ironic twist to a protest or violent terrorist act, and in case would underscore the sense of dread of

commercially defined consciousness.

Although a more traditional narrative, “The Soul is not a Smithy” is also not without elements of

empathetic exploration. In it, the unnamed narrator juxtaposes the intense boredom he felt as a

schoolchild with that of the white collar work which his father performed for decades. The story mostly

consists of the narrator imagining other lives, both imaginary (as a schoolchild he was unable to pay

attention in class, and instead stared out the grated classroom window, in different segments of which he

imagined extremely elaborate and dramatic narratives playing out) and real (his childhood classmates

and, as said, his father). The narrator is aware, though, of the limits of his ability to empathize, lamenting

the fact that he didn’t understand even his own father: “...the truth is that I have no idea what he thought

7 Butler, Blakehttp://htmlgiant.com/feature/themythofthehumanwrtdavidfosterwallacesmistersquishy

15

about, what his internal life might have been like” (107). The narrator “had begun having nightmares

about the reality of adult life as early as perhaps age seven” (103). These nightmares feature office

environments possessing a sterility, uniformity and ominous sense of scale that, while seeming surreally

dystopian, are perhaps not all that unrealistic. In the same NPR interview cited previously, Wallace says

“I think... in a country in which we have it as easy as we do, one of our big dread vectors is boredom...

and I think... that little edges of despair and soullevel boredom appear in things like homework, or

particularly dry classroom stuff.” This phrase, ‘soullevel boredom,’ appears as well in “The Soul is not

a Smithy”:

There was something about this routine that cast shadows deep down in parts of me I could notaccess on my own. I knew something of boredom by then, of course, at Hayes, and Riverside[schools], or on Sunday afternoons when there was nothing to do the fidgety type ofchildhood boredom that is more like worry than despair. But I do not believe I consciouslyconnected the way my father looked at night with the far different and deeper, soullevelboredom of his job... (105)

It’s tempting to dismiss the bourgeois problems Wallace’s characters face as just that

anxieties of the privileged which these characters’ socioeconomic status affords them the ‘luxury’ of

having. At times, Wallace’s own humor (i.e. Schmidt’s masturbation and Neal’s foolish antics) lends this

interpretation some credence. But these are serious problems. I believe that Wallace does more than

just point to something like the platitude that ‘money doesn’t buy happiness,’ but rather gets at the

fundamental lack of meaning in the increasingly complex world we now inhabit. But there is certainly

room for debate about the extent to which he is ‘right’ about our present condition. At no point do any

of these characters entertain the idea of leaving an unsatisfying occupation, or attempting to disengage

from the systems which trouble them; it seems to simply not be a possibility for them. Granted, perhaps

a problem like that of Neal in “Good Old Neon” is too deeply rooted for these possible solutions, but

16

they could have been options for Lane Dean, Jr. when the tedium of his IRS job almost drives him to

suicide. A friend of mine has observed that Wallace’s fiction, and specifically The Pale King “had zero

of the pioneering American spirit” by which I think he meant that kind of spirit of people who make a life

for themselves, on their own. Perhaps that’s the point, though that our economy, our country, is

dominated by vast and soulsucking commercial systems which trap us in soulsucking labor. Perhaps

the type of high ambition and extravagant egoideal displayed by T.E. Schmidt (or just, of course, the

need to make as much money as possible; we are told, in fact, that Dean stays because he has a wife

and child to support) can imprison people in careers they hate. But maybe not everyone experiences the

boredom and despair that we might expect them to. As I think was demonstrated here, Wallace was

acutely aware of our limited abilities to understand what others go through, how they experience their

own lives. I think it’s reductive to imagine that all people in a seemingly boring or painful job are as

profoundly unhappy as Wallace might have you believe. His communication of the difficulties of the

human struggle within the overwhelming networks that define our lives, though, are profound and

insightful.