The Lost Wheel Map of Ambrogio Lorenzetti

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of The Lost Wheel Map of Ambrogio Lorenzetti

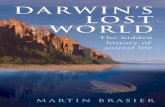

The Lost Wheel Map of Ambrogio LorenzettiAuthor(s): Marcia KupferSource: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 78, No. 2 (Jun., 1996), pp. 286-310Published by: College Art AssociationStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3046176 .

Accessed: 23/05/2013 19:17

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

College Art Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The ArtBulletin.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The world map that Ambrogio Lorenzetti painted in 1345 for the communal palace of Siena has long since vanished, but not without leaving spectacular traces of its unique design (Figs. 1, 2) A rotating wheel, the work scratched a series of great concentric rings into the surface of the wall on which it hung, thereby damaging a prior layer of painting concealed beneath. These rings and other aspects of its installation were discovered in 1980-81 when the fresco of Guidoriccio da Folignano was subjected to technical exami- nation. In the middle register of the wall just below the image of the war captain, conservators exposed to view a previously unknown trecento fresco of the highest quality. The newly revealed scene, two men in the act of surrendering a town (hereafter referred to as the "New Town"), bears the imprint of the revolving map that superseded it. A fresco border painted in black around the circumference of the wheel, and serving to integrate it into a system of monumental mural decoration, was also partially recovered. As far as the carto- graphic image itself is concerned, a scarred patch of earlier painting admittedly amounts to an empty cipher. Yet the visible signs of the work's display and use, exceptional in the fragmentary history of medieval cartography, mitigate the absence of the monument that gave to the council hall its popular name, the Sala del Mappamondo.

To date, study of Lorenzetti's map has focused on recon- structing its intriguing pictorial content. Several generations of scholars have sought to visualize the lost image by mining archival sources, glossing apparently conflicting descrip- tions, and identiting later works for which it may have served as model.l Since the recent restoration campaign, attention has been given to how physical evidence of the map's installation may bear upon the superposition, and hence relative dating, of the paintings on the Guidoriccio wall. In what follows, I shall attempt to open the discussion to broader issues raised by the map's enigmatic relation to

An outsider to the field of Italian trecento painting, I could never have begun to navigate the unfamiliar not to say treacherous waters of the Sienese canon were it not for the kindness and assistance of two colleagues at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., David Brown and Gretchen Hirschauer. Thanks to Dr. Brown's intervention, Sr. Alessandro Bagnoli of the Sopraintendenza per i Beni Artistici e Storici di Siena made possible my study of Lorenzetti's Mappamondo. Professor Hayden Maginnis generously furnished me with copies of articles pertaining to the Guidoriccio debate from the Notizie d'arte, which proved otherwise impossible to obtain, at least from research libraries in this hemisphere. Because Peter Barber, Jerome Baschet, Paul Binski, Evelyn Edson, and Patrick Gautier Dalche shared their insights with me, this article is far richer than it would otherwise have been. Finally, I owe a deep debt of gratitude to the Art Bulletin's anonymous reviewers for their incisive comments on an earlier draft. Translations are mine unless otherwise noted; Bibllcal texts are cited in Latin from the Vulgate and in English translation from the Douay-Rheims version.

1. Bargagli Petrucci; W. Braunfels, Mittelalterliche Stadtbautunst in der Toskana (1953), 4th ed., Bcrlin, 1979, 197; G. Rowley, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, 2 vols., Princeton, N.J., 1958, 1, 98; C. Ragghiante, "Mappamundus volubilis,"

known cartographic traditions, its location in the Palazzo Pubblico, and its rotary operation.

The first part of the study reviews the documentation concerning the map in order to clarit its physical nature. Here, the tradition of medieval display maps puts into new perspective the minimal clues about the Lorenzetti with which we are now sadly left. With regard to the cartographic image itself, the second part considers the crucial problem, not heretofore adequately addressed, of how the wheel's rotation would have been implicated in the formal depiction of the world.2 For the revolving map to have worked visually, its pictorial composition, including any writing, must have met the demands of a shifting orientation. With this in mind, it may be possible to single out a specific class of maps as Lorenzetti's most likely point of departure. The develop- ment of a particular cartographic genre, I am proposing, underlay the very possibility of the commission. We cannot hope, nor perhaps should we try, to reconstruct the "look" of Lorenzetti's painting. But the artistic context that enabled the con(re)ception of such an extraordinary work can be interrogated.

Parts three and four explore the work's production of meaning as a function of its place within a constellation of framing images. Surrounding pictorial material activated the signiting potential of both the cartographic image and its performance as a wheel. On these two levels also, Loren- zetti's painting reciprocally engaged earlier decoration in the hall to new ends. Just as the wheel map revised or expanded on ideas previously articulated in the Sala del Consiglio, so also it was in turn incorporated into a continu- ously evolving ensemble. Recalling the role of mappaemundi both in ecclesiastical and royal settings, the Sienese treat- ment of the theme displaced age-old traditions to further the secular ideology of the commune. Lorenzetti's map contrib- uted to the elaboration of a civic agenda by appropriating competing discursive "regimes."3 Finally, I suggest in part

Critica d'Arte, XLVI, 1961, 46-49; M. Testi, "Ambrogio Lorenzetti et San Miniato," Critica d'Arte, XLVI, 1961, 37-45; A. Cairola and E. Carli, 11 Palazzo Pubblico di Siena, Rome, 1963, 139-40; E. Carli, "Luoghi ed opere d'arte senesi nelle prediche di Bernardino del 1427," in Bernardino predicatore nella societa del suo tempo, Convegni del Centro di Studi sulla spiritualita medievale XVI, Todi, 1976, 153-82, esp. 172-74; C. Sterling, "Le Mappemonde deJan van Eyck," Revue de l'art, XXXIII, 1976, 69-82, esp. 82, n. 174; Southard, 237-41; Feldges, 65-68; G. Borghini, in Brandi et al., 223-24; and Strehlke, no.32a, 193-97, esp. 196.

2. How to pursue this avenue of investigation became apparent to me only after stimulating conversations with Paul Binski, who deserves much of the credit for clarifying the formal problems posed by Lorenzetti's revolving map and none of the blame for any errors in the solution I propose.

3. I am here borrowing a concept articulated by R. Starn, "The Republican Regime of the 'Room of Peace' in Siena, 1338-40," Representations, XVIII,

1987,1-32, esp.3, and further developed in R. Starn and L. Partridge, Arts of Power: Three Halls of State in Italy, 1300-1600, Berkeley,1992,9-80,261-66, esp.14.

The Lost Wheel Map of Ambrogio Lorenzetti

Marcia Kupfer

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LOST WHEEL MAP OF AMBROGIO LORENZETTI 287

1 Siena, Palazzo Pubblico, Sala del Mappamondo, west wall: upper register, Guidoriccio da Folignano; lower register, the "New Town" damaged by the lost Mappamondo of Ambrogio Lorenzetti, 1345, flanked by Sodoma, SaintAnsanus (left) and Saint Victor (right), 1529 (photo: Soprintendenza B.A.S.-Siena)

2 Detail of Fig. 1 (photo: Soprintendenza B.A.S.- Siena)

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

288 ART BULLETIN JUNE 1996 VOLUME LXXVIII NUMBER 2

five that the Mappamondo may have been part of a program-

matic transformation of the Sala del Consiglio itself.

The Cartographic Artifact Scholars agree on some basic features of Lorenzetti's map.

The great majority of specialists visualize it as a rotating disk

located on the Guidoriccio wall below the equestrian figure,

where the scoring is now visible. Predictably, Gordon Moran

and Michael Mallory, who deny the authenticity of the

Guidoriccio, arglle a different view. But holding the Map-

pamondo hostage to the Guidoriccio, as Moran and Mallory do,

will not help advance understanding of either work.4

The written evidence may be easily summarized. The date

of the commission and its attribution to Ambrogio are first

recorded in the chronicle of Agnolo di Tura del Grasso at the

end of a series of miscellaneous entries for the year 1345: "E1

Napamondo, che e in palazo de' segnori di Siena fu fatto in

questo anno; fecelo maestro Ambruogio Lorenzetti dipen-

tore da Siena."5 The Concistoro authorized the restoration

of the Mappamondo in 1393.6 The substantial sum paid then

to three painters for their colors, including azure, suggests a

pictorial surface of monumental proportions.7 A glass win-

dow was ordered to be made "iuxta mappamundum" in

1413.8 When preaching in the Campo in 1427, Saint Bernar-

dino of Siena reminded his audience of the image of Italy

"nel Lappamondo."9 Ghiberti called Lorenzetti's work in the

Palazzo Pubblico a cosmografia a term he used both as a

synonym for a map of the inhabited world and as the title for

Ptolemy's Geography. lO Remarking on what could only be the

same work, the Sienese antiquarian Sigismondo Tizio (1455-

1528) retained the term mappamundi entrenched in local

tradition,ll whereas later in the sixteenth century Vasari

followed Ghiberti in referring to the Lorenzetti as a

cosmograf a. 12

So far as I am aware, Tizio, writing in the mid-1520s,

provides the earliest description of the map's rotation and

location: "Hoc vero anno [1344] mappamundum volubilem

rotundumque in aula secunda balistarum publici palatii ille

Vir [Ambrosius Laurentii] fecit. Pinxerat quoque aulam

primam in scalarum primarum vertice, quae aula pacis

4. On the controversy over the Guidoriccio, see the following (in chronologi-

cal order): G. Moran, "An Investigation regarding the Equestrian Portrait of

Guidoriccio da Fogliano in the Sienese Palazzo Pubblico," Paragone, XXVIII,

no.333, 1977, 81-88; M. Mallory and G. Moran, "Guido Riccio da Fogliano: A

Challenge to the Famous Fresco Long Ascribed to Simone Martini and the

Discovery of a New One in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena," Studies in

Iconography, VII-VIII, 1981-82, 1-13; G. Moran, "Guido Riccio da Fogliano: A

Controversy Unfolds in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena," Studies in Iconography,

VII-VIII, 1981-82, 14-20; Seidel; J. Polzer, "Simone Martini's Guidoriccio da

Folignano: A New Appraisal," Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen, xxv, 1983,

103-41; News from RILA, II, Feb. 1984, 1, 3-5; Polzer, 1985; C. Frugoni and

O. Redon, "Accuse Guido Riccio de Fogliano, defendez-vous!" Me'die'vales, IX,

1985, 119-31; M. Mallory and G. Moran, "New Evidence Concerning

'Guidoriccio,' " Burlington Magazine, CXXVIII, no. 997, 1986, 250-59; Martin-

dale, 1986; Polzer, 1987; P. Toritti, letter, Burlington Magazine, CXXXI, no.

1036, 1987, 485-86; C. B. Strehlke, "Niccolo di Giovanni di Francesco

Ventura e il 'Guidoriccio,' " Prospettiva, L, 1987, 4548; L. Bellosi, "Ancora

sul 'Guidoriccio,' " Prospettiva, L, 1987, 49-55; Martindale, 1988, ?09-1 1; P

Torriti, "La parete del 'Guidoriccio,' " in Simone Martini: Atti del convegno

Siena, 27, 28, 29 marzo 1985, ed. L. Bellosi, Florence, 1988, 87-97; and

Maginnis. Additional bibliography is cited in n. 25 below.

5. Cronache Senesi, ed. A. Lisini and F. Iacometti, in Rerum Italicarum

scriptores, ed. L. A. Muratori, n.s. 15, VI, Bologna, 1935, 547. On problems

concerning the date of the chronicle's compilation, see Martindale, 1986,

nuncupatur" (In the year 1344 Ambrogio Lorenzetti made a

turning, circular map of the world in the second hall of

armaments in the Palazzo Pubblico. He also painted the first

room [of armaments] at the top of the stairs, which is called

the hall of peace). 13 Two chambers on the second floor of the

Palazzo Pubblico displayed armaments: the Sala del Con-

siglio and the adjoining Sala dei Nove, or meeting room of

the ruling oligarchy, which had come to be called the Sala

della Pace after Lorenzetti's famous Good Government. Both

rooms were sometimes alternatively designated "Sala delle

Balestre.''l4 Tizio distinguishes them in the order of their

proximity to the stairs and further indicates that it is the

second such room, i.e., the Sala del Consiglio, as opposed

to the first or Sala della Pace, which contains the mappa-

mundus volubilis.l5 In a volume of addenda to his history,

Tizio moreover specifies that the Mappamondo hung on the

Guidoriccio wall below the equestrian image: "Hic ille [Guido

Riccius] est, qui in aula Dominorum Senensium pictus est in

Capite Mappe Mundi rotunde, ubi Montis Massici picta est

obsidio" (Here is Guidoriccio, who is painted in the hall of

the Sienese lords above the circular world map, where the

siege of Montemassi is painted).lfi The placement of the

Mappamondo below the Guidoriccio is reiterated in an early

seventeenth-century source.l7 Where Tizio saw the Map-

pamondo, we now see the pattern of concentric rings scored

into the wall. The Mappamondo so dominated its spatial setting that it

eventually dictated the name of the hall. Although I have

been unable to find the appellation "Sala del Mappamondo"

in official records before 1534,l8 it may have become a

popular term of reference at an earlier date. The object now

silhouetted on the Guidoriccio wall, measuring about 15 feet

10 inches (4.83 m) in diameter, l9 was sufficiently imposing in

size to have been the Mappamondo. By Tizio's day, the

Mappamondo may have already been cut down to make way

for the current doorway between the Sala del Mappamondo

and Sala dei Nove. Certainly by 1529 it was reduced in size to

accommodate Sodoma's fresco of Saint Victor at right.20

Eighteenth-centuly descriptions introduce new elements,

but the discontinuity is not strong enough to warrant the

261-62; Mallory and Moran, 1986 (as in n. 4), 251 n. 11 with bibliography;

and Maginnis, 141. 6. G. Milanesi, Documenti per la storia dell'arte senesi, 3 vols. (Siena, 1854),

rpr. Soest, 1969, II, 37, citing the Libro del Camarlingo of the Biccherna, chap.

56, for Dec. 11, 1393: "Deliberaverunt, quod Bartalus magistri Fredi,

Cristofanus magistri Bindocci et Meus Petri, pictores, habeant ab operario

Camere Comunis Sen: quatuor flor: auri in auro pro eorum salario et labore,

eo quod pinxerunt et reactaverunt Mappamundum Item det et solvat eis

quas spenderunt (sic) in azuro et aliis coloribus in dicto aconcimine dicti

Mappamundi: in totum libras duodecim." The vernacular summary of this

authorization is cited by U. Morandi, in Brandi et al.,423, no.231.

7. Polzer, 1985, 147 n. 17; and Polzer, 1987, 25 n.55.

8. For Dec. 31, 1413, as cited in Bargagli Petrucci, 14: "Camerarius

Consistorii qui habet de den. Comunis circa XLVII lib. deponat dictos den.

penes Bartholomeum Iohannis Cecchi, et quod de dictis den. debeat fieri una

finestra del vetro que est iuxta mappamundum cum salario alias declarato."

Reference to the archival source is cited in full by Feldges, 124 n.221.

9. Le prediche volgari de San Bernardino da Stena, ed. L. Banchi, 3 vols.,

Siena, 1880-88, III, 259, glossing Ps. 57 (58): "Erraverunt ab utero: Eglino

hanno errato dal ventre,-dice David ai Taliani. Doh, dimmi: hai tu veduta

Italia come ella sta nel Lappamondo? Or ponvi mente: ella sta propio propio

come uno ventre. Eglino hanno errato tutt'i Taliani."

10. I commentarii, ed. J. von Schlosser, 2 vols., Berlin, 1912, I, 41 (with notes

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LOST WHEEL MAP OF AMBROGIO LORENZETTI 289

conclusion that they refer to a different work. G. A. Pecci, G. Faluschi, and G. della Valle, it is true, depart from the vocabulary used by earlier witnesses: they speak of a "carta topografica nella quale appariva delineato tutto lo Stato di Siena.''2l I shall address the import of their description in the following section. My point here is that their similar accounts of the object's rotation confirm they were looking at the same mappamundus volubilis as Tizio. Using slightly varying phrases, all three writers compare the map to a turning wheel: "si vede un' avanzo molto lacero di carta topografica . . . fatta a guisa di ruota da potersi muovere e girare."22

The 1980-81 restoration campaign provided incontrovert- ible physical evidence that the circle imprinted on the Guidoriccio wall was occupied by a revolving disk.23 As specified in the eighteenth-century sources, it indeed turned on a single pivot, or stylus, by which it was affixed to the wall. The height at which the disk was installed suggests that its rotation could be effected manually from the floor. In his Lettere Senese of 1785, della Valle echoes Pecci (1730, 1752) and Faluschi (1784) in reporting "un awanzo molto lacero di carta topografica," but adds that it was painted "in tela, di cui ora non resta che qualche piccolo cencio."24 Evidently eighteenth-century witnesses had before them merely a scrap of the map. The topographic depiction of the Sienese state then visible could thus have been but a small fragment of the whole.

The cumulative evidence leads to the conclusion that the rotating disk beneath the Guidoriccio was Lorenzetti's Map- pamondo. In contrast, the argument put forward by Moran and Mallory is rather weak. They believe that the rings scratched into the intonaco of the "New Town" and circular border in fresco correspond not to the Lorenzetti work of 1345, but rather to a representation of the Sienese state commissioned in 1424. Based on his reading of a mid- fifteenth-century inventory of mobile objects in the Palazzo, Moran situates the Lorenzetti instead in the Sala dei Nove.25 This double proposition strikes me as a desperate attempt at obfuscation for the sake of sustaining an attack on the traditional attribution of the Guidorzccio.

A commission for the representation of the Sienese state was contemplated in December 1424, but its terms could

II, 144): "Evi una Cosmogrofia cioe tutta la terra abitabile. Non c'era allora notitia della Cosmogrofia di Tolomeo, non e da maraviglare se'lla sua non e perfetta." On Ghiberti's visits to Siena in 1416 and 1417, see Strehlke,35.

11. "Historiarum senensium," 10 vols., Siena, Biblioteca Communale MSS B.III. 15. The two passages concerning the map (vols. II, fol. l 82 and x, fol. 99) are quoted in full in Maginnis, 140-41, esp. nos. l 6, 17.

12. Le vite de' piu eccellente pittori, scultori e architettori, texts of 1550 and 1568, ed. R. Bettarini, commentary P. Barocchi, Florence, 1966, II, 180-81.

13. The Latin text is cited by Maginnis, 140. 14. On the names for the Sala del Consiglio and the Sala della Pace, see

Southard, esp. 213, 271; and idem, "Ambrogio Lorenzetti's Frescoes in the Sala della Pace: A Change of Names," Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz, xxrv, no.3, 1980,361-65.

15. Maginnis, 142. 16. The Latin is cited by Maginnis, 140-41, no. l 7. 17. A 16th-century Sienese history, G. Tommasi's Dell'historie di Siena,

which was published posthumously in 1625-26, similarly indicates the location of the Mappamondo; see Martindale, 1986, 261 and n. l 6.

18. Morandi, in Brandi et al.,428, no.406. 19. Seidel, 22. 20. Ibid. The doorway between the two rooms was ordered to be remade in

1466; see Morandi, in Brandi et al., 428, no. 379. 21. G. A. Pecci, "Raccolta universale di tutta l'inscrizioni, arme, e monu-

menti antiche esistente in Siena," 3 vols., 1730, Siena, Biblioteca Communale

suggest a series of topographic views as easily as a map, and the place of display is unclear: "Deliberatum etiam quod pingantur sive designentur ad bazeum omnes terre acquisite et recuperate tempore presentis regiminis in sala balistarum, sive in sala magna Consilii, prout alias per eos deliberabitur" (It was also deliberated that all lands acquired and retaken at the time of the present government be painted or repre- sented at/on [?] in the Sala delle Balestre, or the great hall of the Council, accordingly others [other lands] as it will be deliberated by them).2fi

Was this image of the Sienese state executed? In any event, it could not have replaced the Mappamondo om which Saint Bernardino recalled an image of Italy, a work still visible in 1427. Moreover, the inventory of mobile objects cited by Moran merely places the Mappamondo in a "sala delle balestre" of which there were two on the second floor. Given the explicit distinction Tizio makes between the room of the map's location and the Sala della Pace, Moran's interpreta- tion of the ambiguously worded inventory seems gratuitous. Thus, despite Moran's and Mallory's objections, the schol- arly consensus concerning the installation of the Map- pamondo is not seriously challenged.

However, the material of the work's support has remained a matter of confusion.27 Many scholars have assumed that Lorenzetti's work of 1345 was painted either on panel or vellum.28 As a result, some have brushed aside della Valle's statement that the map was painted on cloth; others have pointed to his remark as an indication that the Lorenzetti was eventually replaced with a later work. Yet there is no good reason to doubt della Valle.

Given the size of Lorenzetti's map and the manner of its installation, a wood panel would have been impractical; a tondo of just under 16 feet (4.83 m) in diameter would have been far too heavy to rotate on a single pivot. Vellum, on the other hand, is nearly as light and perhaps even more durable than cloth, but would hardly have provided an elegant solution. To yield a surface the size and shape of Lorenzetti's map, numerous skins would have had to be stitched together and cut into a circle. Easily nine deer hides, about the size of the late thirteenth-century Hereford and Duchy of Cornwall maps (respectively 5 ft. 2 in. x 4 ft. 4 in. [1.58 x 1.30 m] and 5

MS C. III. 9, II, fol. 140v, cited by Southard, 238; idem, Relazione delle cose piu notabili della citta di Siena, Siena,1752, 75-76; G. Faluschi, Breve relazione della cose notabili della Citta di Siena, Siena, 1784 (rev. ed. of Pecci, 1752), 109; and G. della Valle, Lettere Senesi, 3 vols., Rome, 1782-86, facsimile, Ann Arbor, 1975, II, 222.

22. Pecci,1730 (as in n. 21), cited by Southard, 238. 23. Seidel,21-22. 24. DellaValle (as in n.21), 222; for Pecci and Faluschi, see n. 21. 25. G. Moran, "Studi sul Mappamondo," Notizie d'arte, x, Feb. 1982, 6-7;

M. Mallory and G. Moran, "Aggiornamenti sulla controversia su Guido Riccio ed il ciclo di castelli dipinti nel Palazzo Pubblico di Siena," Notizie d'Arte, XI, May-June 1983, 50-54, esp.52; eidem, "The Border of the 'Guido Riccio,77' letter, Burlington Magazine, CXXIX, no. 1008, 1987, 187; Polzer, 1985, 147; and Polzer, 1987, 25.

26. The Latin is published by Morandi, in Brandi et al., 425, no. 289. 27. Seidel, 22, speaks of a "disco di legno," which probably led Polzer,

1987, 24, to think of the map as "painted on wood." Polzer, 1983 (as in n. 4), 104, however, rightly envisaged a cloth "mounted on a wooden frame," as does Borghini, in Brandi et al., 224. Rowley (as in n. 1), I, 98, had already deduced that scratches visible on the wall were "caused by the stretchers of the circular wooden frame."

28. Bargagli Petrucci, 6; Cairola and Carli (as in n. 1), 139-40; Carli (as in n. 1), 173; and Moran, 1982 (as in n. 25), 6.

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

290 ART BULLETIN JUNE 1996 VOLUME LXXVIII NUMBER 2

ft. 5 in. [1.64 m] square), would have been required.29

Indeed, the giant Ebstorf map of around 1300 (11 ft. 9 in.

[3.57 m] square) was painted on thirty goatskin panels sewn

together.30 The necessarily patchwork quality of the result-

ing pictorial surface seems unlikely to have appealed aestheti-

cally to Lorenzetti or his patrons. Moreover, how would

vellum have been mounted on a rotating frame? Cloth, not

vellum, could have been stretched over an open wooden

framework necessary to minimize the weight of the artifact.

The concentric rings scratched into the fresco beneath the

map would seem logically to reflect either the construction of

such a stretcher or perhaps a series of spaced rollers attached

to the back of the framework. Rollers may have served to

hold the frame parallel to the wall; otherwise, the wheel map,

handled from below, could have been prone to tilting.3l

Furthermore, the use of cloth as the support of choice for

display maps is well documented. Around 1299-1300, a

mappamundi painted on cloth was inventoried in the posses-

sion of King Edward I of England; of this lost object, nothing

else is known.32 Fabric appears to have become an increas-

ingly common support for cartographic images in the fif-

teenth century, and Rene of Anjou (1409-1480), king of

Hungary, Jerusalem, Naples, and Sicily, had many such

items.33 In 1493, the Sienese cardinal Francesco Todeschini

Piccolomini gave to Siena Cathedral a circular map of the

world painted on cloth ("Cosmographiam Ptolomei, quam

Mappam Mundi appellant, lintea tela depictam . . . in forma

rotunda"); it had originally been made in the early 1460s for

Piccolomini's uncle Pope Pius II by the Venetian Antonio

Leonardi.34 Might this commission have on some level

played offthe Mappamondo in the Palazzo Pubblico?

The disk silhouetted on the Guidoriccio wall conforms to

the expected shape for the genre of image, a mappamundi or

mappamondo, specified in the earliest references to Loren-

zetti's work. Yet this structural coincidence between physical

artifact and cartographic image already begins to reveal the

remarkable character of the commission. In the medieval

period, the representation of the world as circular rarely

extended to the shape of the support. Such a correspon-

dence between circular map image and an artifact's physical

form occurs, for example, with metalwork tables recorded in

the treasuries of secular rulers,35 but not usually in the case of

wall maps. The few large vellum mappaemundi that survive

from the thirteenth centuly, indicative of a widely dissemi-

nated tradition, adopt a quadrilateral format (the Hereford

29. N. Morgan, Early Gothic Manuscripts: II. 1250-1285, London, 1988, no.

188, 195-200 (with bibliography); G. Haslam, "The Duchy of Cornwall Map

Fragment," in Getographie du Monde au moyen age et a la Renaissance, ed. M.

Pelletier, Comite des travaux historiques et scientifiques, Memoires de la

section de geographie xv, Paris, 1989, 33-44; and Kupfer, 271-76.

30. For a description and reproductions of the Ebstorf map, see B.

Hahn-Woernle, Die Ebstorfer Welttarte, Stuttgart, 1986, 7-12. Additional

bibliography accompanies my discussion of the monument; see Kupfer,

27 1-72. 31. The use of rollers is the ingenious idea of one of the anonymous

reviewers for the Art Bulletin, who generously shared an explanation of how

such a device would work. In incorporating this reader's valuable insight into

my essay, I bear responsibility for any misconceptions in the proposed

reconstruction of the cartographic artifact.

32. O. Lehmann-Brockhaus, Lateinische Schriffquellen zur Kunst im England,

Wales und Schottland vomJahre 901 bis zumJahre 1307, III, Munich, 1956, 302,

no. 6201 (from Liber quotidianus contrarotulatoris garderobae anno regni regis

Edwardi Primi vegisimo octavo, A.D. 1299-1300, London, 1787): "Unus

retains the neck of the hide) in which the circular image of

the world is inscribed. One possible exception that springs to

mind, however, is significant for what it suggests about the

aims of the Lorenzetti commission. The lost mappamundi

painted in 1239 for the great hall of Winchester Castle could

well have been a circular object, for it was conceived in all

likelihood as a pendant to a Wheel of Fortune installed three

years earlier on the wall above the royal dais.3fi The Loren-

zetti map more than eliminated the structural distinction

between cartographic image and artifact. Its rotaty mo-

tion to my knowledge unprecedented in the histoty of

medieval cartography actually, and not merely metaphori-

cally, assimilated the image of the world to a wheel.

At this point, some discussion of the physical relationship

between the Mappamondo and the Guidoriccio proves unavoid-

able. Two different types of circular markings, which are not

concentric, have been observed on the wall below the war

captain. An incised outermost arc, traced over with sinopia,

intersects the inscription of the date in the lower border of

the Guidoriccio; the incision cuts into the intonaco. All the

other circles are grooves gouged into the fresco of the "New

Town"; they are centered on a point 6 inches (15 cm) to the

right and 10 inches (25 cm) lower down on the wall.37

Needless to say, the interpretation of the marks is a matter of

dispute between Malloty and Moran on the one hand and

those responsible for the restoration on the other.38 Malloty

and Moran date the upper set of marks the incised arc and

the sinopia tracing to 1912-14 (i.e., when F. Bargagli

Petrucci proposed unsuccessfully to "reconstruct" the lost

Lorenzetti by reproducing on the wall a copy of the map-

pamundi by Pietro de Pucci da Orvieto in the Camposanto,

Pisa). In addition, they claim that the lower set of furrows

extended beneath a narrow red band in the border of the

Guidoriccio that was wrongfully removed during the restora-

tion. This would mean that the Guidoriccio was painted after

the installation of the rotating object, whether it was Loren-

zetti's Mappamondo or, as they prefer, a 1424 representation

of the Sienese state.39 Piero Torriti has vigorously refuted

their assertions.40 He has identified the narrow red band as a

mid-nineteenth-centuly restoration painted after yet an-

other layer of whitewash was applied to hide the damaged

middle zone of the wall. The grooves do not otherwise

interfere with the border of the Guidoriccio. Obviously, the

compasslike incision and sinopia brush line cannot date from

pannus regi datus ad modum mappe mundi."

33. F de Dainville, "Cartes et contestations au XVe siecle," Imago Mundi,

XXIV, 1970, 99-121, esp. 102 and n. 7 for a description of the process by

which a local painter was hired in 1423 to make a map on cloth of the

counties of the Valentinois and Diois for the dauphin; C. de Merindol, Le Roi

Rene et la seconde maison d'Anjou, Paris, 1987, 185-87; and A. Lecoy de la

Marche, Extraits des comptes et metmoriaux du Roi Rene', Paris, 1873,270.

34. Cited by R. Gallo, "Le mappe geografiche del Palazzo Ducale di

Venezia, Archivio veneto, LXXIII (ser.5, XXXII-XXXIII), 1943,47-89,50.

35. Most notably the silver tables of Charlemagne and Roger II; see

Kupfer, 268, 283 nn.51,52. 36. Ibid.,279 (with bibliography). 37. Seidel,21-22. 38. Maginnis, 139.

39. Bargagli Petrucci, 13. Mallory and Moran, 1987 (as in n.25), 187.

40. Torriti, 1987 (as in n.4), 485-86.

41. Bellosi, 1987 (as in n.4), 51-52,55 n. 7.

42. Seidel,22.

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LOST WHF.EL MAP OF AMBROGIO LORENZETTI 291

1912-14 if they appeared only after the removal of nine- teenth-century repainting.4l

As I accept Torriti's explanation, I am prepared to consider Max Seidel's argument that the two sets of circular markings correspond to different installations of the revolv- ing disk. Two points of insertion for the pivot were recovered during the 1980-81 campaign.42 In Seidel's view, the inci- sion traced in sinopia indicates the object's experimental first position at 5 feet 7 inches (1.70 m) from the lowest point of the disk to the pavement; once the map was seen to cover the inscription, it was then moved to its second and definitive position 4 feet 9 inches (1.45 m) from the lowest point of the disk to the pavement. Seidel's hypothesis, although not unbiased (he champions the traditional attribution and dating of the Guidoriccio), is at the very least plausible. This reading of the physical data would make the 1345 map the terminus ante quem for the Guidoriccio, to which I have no objections on other grounds. Attribution and a more specific dating are not my concerns. True, nagging ambiguities surround the relationship of the Guidoriccio intonaco to that of the fresco of about 1364 by Lippo Vanni on the adjacent wall.43 Nevertheless, I am satisfied that the physical record as it now stands supports the following relative chronology of frescoes on the Guidoriccio wall: (1) the "New Town"; (2) Guidoriccio; (3) the Mappamondo; (4) a quattrocento repaint- ing of Montemassi; (5) Sodoma's paintings of Saints Victor and Ansanus.

My interpretation of the role of Lorenzetti's work in the Sala del Mappamondo depends only to a limited extent on the strong presumption that the equestrian image was already in place by 1345 when the Mappamondo was installed. Should the Guidoriccio eventually prove to postdate the Mappamondo or even the Lippo Vanni, aspects of my argu- ment may be modified without substantially altering what I consider its main points. In any case, I am convinced that the fresco of the horseman is trecento; frankly, I do not see what else it could be.

The Cartographic Image Theories concerning the map's representational scheme hinge on differing interpretations of mappamundi and cosmografia and on how these terms can be reconciled with eighteenth-century descriptions of a carta topografica showing the Sienese state. If these theories are scrutinized in relation to medieval traditions of cartographic representation, specu-

43. Maginnis, 142. See, however, Martindale, 1986, 266; Polzer, 1987, 25-26; and Torriti, 1988 (as in n. 4), 87-88. On the Battle of the Val di Chiana, see S. Dale, "Lippo Vanni: Style and Iconography," Ph.D. diss., Rutgers University, 1984, 13644.

44. For an extensive discussion of the medieval evolution of the term mappamundi, see D. Woodward, "Medieval Mappaemundi," in The History of Cartography, 286-370, esp. 287-88; and P. Gautier Dalche, La 'Descriptio mappae mundi' de Hugues de Saint-Victor, Paris, 1988, 89-95. K. Lippincott, "Giovanni di Paolo's 'Creation of the World' and the Tradition of the 'Thema Mundi' in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art," Burlington Magazine, CXXXII,

no. 1048, 1990, 460-68, esp. 464, holds to a narrow definition of the term in order to distinguish (quite rightly in my view, see n 51 below) between the particular iconography of the Creation panel and world maps per se.

45. Libellus de formatione arche, ed. P. Sicard, Corpus christianorum continuatio medievalis CLXI, Turnhout, forthcoming. On Hugh's drawing see P. Sicard, Diagrammes me'die'vaux et exe'gese visuelle: Le Libellus de formatione arche de Hugues de Saint-Victor, Paris/Turnhout, 1993, esp. 34-85.

46. Chronica Maiora, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 26, fol. vii

lation on the content of Lorenzetti's painting may receive new focus.

Ordinary usage of the Latin mappamundi and its vernacular derivates throughout the Middle Ages discloses just how semantically unstable the term was. It had evolved to desig- nate a geographic representation of the earth's surface either in the form of a planimetric depiction or in that of textual description; other terms were used as well.44 Yet mundus also means "universe," and mappaemundi were frequently embed- ded in (or implied) cosmological schemes. These brought the immobile earth into harmony with the revolution of the heavens which determined the annual round of months and seasons. In describing his own cosmological diagram, Hugh of St.-Victor distinguished the mappamundi from the surround- ing macchina universitatis.45 But it is unclear whether casual viewers, when referring to images of the geocentric universe, would have systematically drawn the technical distinction between the geographic image of the orbis terrae and its

* n

cosmlc tramlng.

At the same time, the term mappamundi was applied to quite different types of maps of the terrestrial world. Mat- thew Paris used it in what seems to be a caption for a sketch of the European continent extracted from a world map.46 When the earliest textual references to nautical, or portolan, charts appear in the late twelfth and the thirteenth century, these maps of the Mediterranean coastline are called mappae- mundi, an appellation which continued in use along with others.47 In the early fifteenth century, the term accompa- nied by a qualifying phrase could indicate topographic maps of particular regions or locales: "unam figuram ad modum mappaemondi" describes the commission for a map of two counties in the Dauphine in 1423 ("plan ou mapemonde des comtes de Valentinois et Diois" also appears in an account of the expenses incurred).48 A long-familiar expression was thereby adapted to novel attempts at chorography, or the large-scale representation of small areas.

F. Bargagli Petrucci first advanced the proposition, taken up by some later scholars, that Lorenzetti's map represented the entire geocentric cosmos.49 Observing incised rings through successive coats of whitewash, he believed that the work comprised a stationary central disk representing the terraqueous earth and, surrounding this, separable moving rings representing air, fire, and the planetary spheres. The

verso; this point is made by S. Lewis, The Art of Matthew Paris in the Chronica Majora, Berkeley, 1987,372-74, fig.222, and 509 nn. 117, 119.

47. P. Gautier Dalche, "D'une technique a une culture: Carte nautique et portulan au XIIe et au XIIIe siecle," in L'uomo e il mare nella civilta occidentale: Da Ulisee a Cristoforo Colombo, Atti del Convegno, Genoa, 1992, 285-312, esp. 298-99, 307; and idem, Carte marine et portulan au XIIe siecle: Le Liber de existencia riveriarum etforma maris nostri Mediterranei, Rome, 1995, 23-30, 116. See also more generally, T. Campbell, "Portolan Charts from the Late Thirteenth Century to 1500," in The History of Cartography, 371-463, esp. 375,439 on terminology.

48. De Dainville (as in n. 33), 102. Among the possessions of King Rene in 1473 was "a mappemonde on cloth of Tours" "une mapemonde en toille du tour." On this item, see Lecoy de la Marche (as in n. 33), 270; and F. de Dainville, "Cartographie historique occidentale," Annuaire de l'e'cole pratique des hautes e'tudes, sciences historiques et philologiques, CI, 1968-69, 397-403, esp. 403. Whether the inventory entry refers to a world map on cloth showing an image of Tours or rather a world map on cloth from Tours is unclear.

49. Bargagli Petrucci, 7-13; Braunfels (as in n. 1), 197; and Strehlke, 196.

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

292 ART BULLETIN JUNE 1996 VOLUME LXXVIII NUMBER 2

manual rotation.5l As the map was cut back over time, this component would have no longer been visible in the eigh- teenth century. Alternatively, the painting could originally have portrayed the terrestrial world alone. The blue em- ployed in the 1393 restoration could, after all, just as easily have gone for the depiction of ocean and seas.

With or without some iconographic allusion to the cosmos, Lorenzetti's map presented an image of the earthly world that was immediately familiar to its viewers. Saint Bernardino spoke of Italy, Ghiberti of la terra abitabile. Eighteenth- century writers saw on the extant fragment of the cloth disk the topography of the Sienese state. If the city and its contado could still be seen on the remaining interior portion of the disk surrounding the pivot, then the republic must have been positioned toward, though not necessarily exactly at, the center of the map. It is occasionally assumed that map- pamondo and carta topografica are incompatible, indeed mutu- ally exclusive, terms; the eighteenth-century description is then either taken to refer to a later replacement, judged the more reliable guide to the nature of the lost image, or discounted altogether.52 However, the initial premise under- lying these conclusions is by no means valid. All the elements gleaned from the written sources could have been integrated in a single, and what is more, revolving map.

Some scholars have suggested that Lorenzetti's Map- pamondo may have served as the model for schematic world maps by quattrocento artists known to be dependent on the trecento master.53 Examples abound in the Palazzo Pubblico itself. Taddeo di Bartolo painted mappaemundi as attributes of Justice in the Cappella (1406-7) and of Justice and Religion in the Antecappella ( 1414) (Figs. 3-7).54 Two terrestrial globes and a cosmological diagram containing a world map illustrate the Creed in Domenico di Niccolo's intarsia choir stalls ( 1415-28) in the Cappella.55 Later painters placed a world map beneath the feet of Saint Bernardino in portrait icons of the saint in glory (e.g., Fig. 8), a convention adopted by Sano di Pietro for his fresco in the Sala del Mappamondo (Fig. 9).56

When limited to showing the world as a collection of towns, such schematized representations of the earth ultimately belong to an ideographic tradition of medieval origin. In this respect, fifteenth-century Sienese variants recall mappae- mundi illustrating the poem De rebus siculis composed about 1 196 by Peter of Eboli in honor of Emperor Henry VI (Bern,

52. Schlosser (as in n. 10), II, 144; Bargagli Petrucci, 5-6; Cairola and Carli (as in n. 1), 139; and Southard, 239-40.

53. Southard, 239; Feldges, 67; and Seidel, 22. 54. On the cycle in the Antecappella, see D. Hansen, "Antike Helden als

'causae': Ein gemaltes Programm im Palazzo Pubblico von Siena," in Belting and Blume,133-48. Her remarks, l 37, on the world map as symbol of Justice are especially pertinent to the interpretation I develop below.

55. On the intarsia panels, see Southard, 341, 345-46; M. Cordero, in Brandi et al., 83, 89-91, esp. figs. 102, 105; and Strehlke, 194-96. The best reproductions are to be found in F. Boespflug, Le Credo de Siena, Paris, 1985, pls. 2, 3, 7

56. R. L. Mode, "San Bernardino in Glory," Art Bulletin, LV, no. l, 1973, 58-76, esp. 72-73; P. Torriti, La pinacoteca nazionale di Siena: I dipinti dal XII al XVsecolo, Genoa, 1977, 268, no. 253, 300-1, no. 203.

57. Petrus Ansolini de Ebulo, De rebus siculis carmen, ed. E. Rota, Rerum italicarum scriptores XXXI, no. 1, Citta di Castello, 1904. On cartographic

3 Taddeo di Bartolo,Justice, 1406-7. Siena, Palazzo Pubblico, Cappella (photo: Soprintendenza B.A.S.-Siena)

Mappamondo could then have functioned as an astrological/ calendrical device. At least part of this ingenious theory, however, has to be scuttled on account of the technical evidence. Even if it is assumed that such a device could have been constructed as an open framework (although this is hard to imagine), how could the single pivot by which the map was affixed to the wall have anchored a central disk in place while allowing multiple separable rings to revolve around it?50

A modified version of Bargagli Petrucci's idea, involving the representation of the universe on a single disk, could nevertheless still be contemplated. Inclusion of cosmological material at the outer rim of the map may gain support from the restoration document of 1393. The use of blue, for which the painters were reimbursed a considerable sum, could be taken to indicate that the heavens were depicted on the portion of the disk most susceptible early on to damage from

50. As Feldges, 67 and 124 n. 234, has moreover observed, the spacing of the marks scored into the mural surface suggests the whole rotated of a piece; her point remains valid whether the marks were caused directly by the stretcher itself or by rollers attached to the back of it.

51. Borghini, in Brandi et al., 223. Cosmological diagrams that appear in scenes of the world's creation are sometimes cited as possible reflections of the Lorenzetti: e.g., frescoes by Bartolo di Fredi in the Chiesa della Collegiata, S. Gimignano (1367), Giusto da Menabuoi in the Baptistery of the Padua Duomo (1376-78) and Pietro de Pucci da Orvieto in the Camposanto of Pisa (1380-90); an intarsia panel of the choir stalls in the Cappella of the Palazzo Pubblico by Domenico di Niccolo (1415-28; see Strehlke, 194-96, fig. 2); the predella panel by Giovanni di Paolo now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (ca. 1445; see Strehlke, 193-97). In my view, however, the iconographic specifity of such images Creation scenes with particular doctrinal implications (see Lippincott, as in n. 44) and the greater importance given to their heavenly as opposed to their terrestrial components argue against a direct link to the Lorenzetti Mappamondo.

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LOST WHEEL MAP OF AMBROGIO LORENZETTI 293

4 Taddeo di Bartolo, Justice, 1414. Siena, Palazzo Pubblico, Antecappella (photo: author)

Burgerbibliothek MS 120, fols. 140r, 147r; Figs. 10, 11).57 Early district maps of leading city-states, produced in North- ern Italy by the late thirteenth century,58 may also epitomize geographic space in a comparable manner. A map of the region around Asti was twice included in a book of statutes pertaining to the city and its subject territories. The manu- script produced in 1292 (Codex Alfieri, Turin, Bibl. Nazion- ale Universitaria MS F.II.9) was copied around 1353 (Codex Malabayla or Astensis, Asti, Archivio Storico del Comune).59 Both versions of the map (Figs. 12, 13) show slightly irregular rows of conventionalized faSades of fortresses distributed over a plane surface subdivided by rivers. Sienese artists sometimes conflated the abstract type of mappamundi with a map of the state, as in a panel painting by Sano di Pietro now in the Museo del Opera del Duomo (Figs. 14, 15). Unlike the mappaemundi by Taddeo di Bartolo, Domenico di Niccolo, or Sano di Pietro in the Palazzo Pubblico, here a miniature architectural portrait of Siena (left of center) down to the marble stripes of the Duomo particularizes the disk as a representation of the city and its satellite towns.60 If the lost Lorenzetti were the source of map imagery in Sienese quattrocento painting, then it would have shown a terraque- ous disk comprising irregularly shaped patches or islandlike masses dotted with fortresses and trees. Certainly Siena, and possibly also its subject territories and other privileged sites such as Rome or Jerusalem, could have been differentiated

imagery in this work, see H. Georgen, Das Carmen de rebus siculis (Bern, Burgerbibliothek, ms. 120): Studien zu den Bildquellen und zum Erzahlstil eines illustrierten Lobgedichts des Peter von Eboli, Ph.D. diss., Vienna, 1975, 123-40.

58. P. D. A. Harvey, "Local and Regional Cartography in Medieval Europe," in The History of Cartography, 478-82; and idem, The History of Topographical Maps: Symbols, Pictures and Surveys, London, 1980, 58-65. See also V. Lazzarini, "Di una carta diJacopo Dondi e di altre carte del Padovano nel quattrocento," in Scritte di paleografia e diplomatica, 2d ed., Padua, 1969, 117-22; and the remarks on this material by P. Gautier Dalche, "De la liste a la carte: Limite et frontiere dans la geographie et la cartographie de l'occident medievale," in Frontiere et peuplement dans le monde me'diterrane'en au moyenage, specialissue, Castrum, IV, 1992, 19-31, esp. 28-29.

59. Codex Astensis qui de Malabayla communiter nuncupatur, ed. Q. Sella, Atti della Reale Accademia dei Lincei, Anno CCLXXIII, 1875-76, ser. 2, IV-VII, 4 vols., Rome, 1880-87; R. Almagia, "Un antica carta del territorio di Asti," Rivista geografica italiana, LVIII, 1951, 43-44; and Gli antichi chronisti astesi: Ogerio Alfieri, Guglielmo Ventura e secondino Ventura, trans. N. Ferro et al.,

by particularized bird's-eye views.6l Dominating the center, recognizable topographic detail would then have stood out among numerous conventionalized symbols of towns at the periphee, 62

Other scholars have conjectured that Lorenzetti's map may, on the contrary, have presented a more or less continu- ous landscape filled with realistic details in a manner similar to his famous panoramas in the adjoining room.63 Thus departing from the tradition of highly schematized mappae- mundi to which Italian painters of the quattrocento adhered, the Lorenzetti would have instead presaged the fifteenth- century treatment of the theme north of the Alps.64

In either case, the pictorial formulation would have had to respond to the rotation of the wheel. As the disk turned, images and inscriptions in the portion brought to eye level i.e., closer to the viewer on the floor would presum- ably always be correctly oriented. The nature of the artifact, in other words, would presuppose a radial configuration in which the "tops" of things depicted and of letters face toward the center, the "bases" toward the circumference: when features in one half of the disk would appear right side up, those in the other would be turned upside down. Although art historians have tended to favor these two hypotheses, a third possibility should not be overlooked. The elements mentioned in accounts of the Lorenzetti may be found combined in contemporary cartographic materials that,

Alessandria, 1990. The original compilation, or Liber vetus, from which the Codex Alfieri was transcribed no longer survives.

60. See also Strehlke, no. 46, 268-69. 61. Southard, 240-41, suggests Rome or Jerusalem may have been

indicated on Lorenzetti's map. 62. Carli (as in n. 1), 173. 63. Rowley (as in n. 1), I, 98; and Sterling (as in n. 1), 82 n. 174. 64. Sterling, 72. (It is worth pointing out that Sterling's analysis of the

mappemonde commonly attributed to Jan van Eyck must now be abandoned; see J. Paviot, "La Mappemonde attribuee a Jan van Eyck par Facio: Une Piece a retirer du catalogue de son oeuvre," Revue des arche'ologues et historiens d'art de Louvain, xxtv, 1991, 57-62, with references to recent literature. I thank Patrick Gautier Dalche for this reference.) For 15th-century examples of the "landscape" type of mappamundi in Northern art, see The History of Cartography, pl. 12; and P. Whitfield, The Image of the World: Twenty Centuries of World Maps, London, 1994, 15.

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

294 ART BULLETIN JUNE 1996 VOLUME LXXVIII NUMBER 2

5 Detail of Fig. 4 (photo: author)

6 Taddeo di Bartolo, Religion, 1414. Antecappella (photo: author)

7 ;: lS s

8 Pietro di Giovanni d'Ambrogio, Saint Bernardino in Glory, shortly after 1444. Siena, Pinacoteca (photo: Fabio Lensini, Siena)

7 Detail of Fig. 6 (photo: author)

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LOST WHEEL MAP OF AMBROGIO LORENZETTI 295

10 Peter of Eboli, De rebus siculis carmen: "Wisdom Contains All," ca. 1 196. Bern, Burgerbibliothek MS 120, fol. 140r (photo: Burgerbibl.)

9 Sano di Pietro, Saint Bernardino, ca. 1450. Sala del Mappamondo (photo: author)

11 De rebus siculis carmen: Henry VI Enthroned, fol. 147r (photo: Burgerbibl.)

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

296 ART BULLETIN JUNE 1996 VOLUME LXXVIII NUMBER 2

familiar by the portolan charts had already been adapted for

world maps in Venice in the 1320s, and exploited in the

1330s by the Pavian Opicinus de Canistris for his anthropo-

morphized geographic allegories.65 The circulation of por-

tolan charts as likely to be found in the possession of

merchants as of mariners, in libraries as on board ships-

extended well beyond a strictly maritime sphere. Consider-

ing the wide range in levels of production from austere to

ornate, and of functions from humble navigational tool to

luxury display object, Tony Campbell has aptly characterized

the portolan chart as the cartographic equivalent of the

ubiquitous book of hours.66 On complete mappaemundi that integrated the tradition of

the charts, Europe is too eccentrically positioned for Italy to

fall near the center. The world maps of Pietro Vesconte, the

Catalan Atlas of 1375 owned by Charles V (Paris, Bibl. Nat.

MS esp. 30), the mid-fifteenth-century Catalan world map

(Modena, Bibl. Estense, C.G.A. 1), and the Genoese of 1457

(Florence, Bibl. Nazionale Centrale, Port. 1) make it difficult

to see how Lorenzetti could have satisfied this condition,

inferred from eighteenth-century testimony, and at the same

time represented the entire world.67 His work more likely

depended on portolan charts themselves, for focused on the

Mediterranean, they placed Italy at the heart of the inhabited

world. And Siena is, after all, roughly at the center of Italy.

To a precise, centralized depiction of the Mediterranean,

Lorenzetti could have added more generalized, partial repre-

sentations of Africa and Asia, a procedure followed in charts

in the Catalan manner. Elaborately embellished with sym-

bols and figures marking the continental interiors, such

works tend to cover the known world between the Atlantic off

the west coast of Ireland and the Persian Gulf, between the

Baltic and the Sahara. The charts of 1325-30 by Angelino de

Dalorto, 1339 by Angelino Dulcert (possibly the same indi-

vidual; Fig. 16), about - 1385 by Guillelmus Soleri, 1413 by

Mecia de Viladestes, or 1439 and 1447 by Gabriel de

Vallsecha (Fig. 17) exemplify a genre primarily associated

with Majorca. Eventually, however, Catalan-style charts, rich

in decorative enhancements, were produced also in Italian

shops, as those of 1367 by the Venetian Pizigani brothers and

of 1482 by Grazioso Benincasa of Ancona demonstrate.68

Inscriptions and, on charts in the Catalan vein, images

were typically arranged to compensate for the absence of a

fixed orientation. To quote from Campbell's discussion of

the standard graphic conventions used on the earliest charts:

So that there should be no interference with the detailing

of the coast or its offshore hazards, the place-names were

written inland at right angles to the shore. This practice

meant that the names have no constant orientation but

follow one another in a neat unbroken sequence around

the entire continental coastlines.... On the basis of north

orientation, the west coasts of Italy and Dalmatia, for

example, are the "right way" around, whereas Italy's

(as in n. 64), 26-27, 40-41. 68. For the locations of these works, see Campbell, in The History of

Cartography, 449-56. The bibliography in Campbell's chapter, now the basic

general text on this material, can be supplemented with M. Pelletier, "Le

Portuland'AngelinoDuclert,1339,"CartographicaHelvetica,Ix,1994,23-31. For reproductions, see Y. Kamal, Monumenta Cartographica Africae et Aegypti, 5

12 Codex Alfieri, preserved fragment of the map of the region

around Asti, 1292. Turin, Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria MS

F.II.9, fol. 6 (photo: Bibl. Naz. Univ.)

while not wheels, were meant to be rotated and thus

dispensed with the principle of a fixed orientation.

The geographic basis of Lorenzetti's map could have been

derived from portolan charts, which by 1345 had created,

certainly for Italians, the normative notional image of the

world. The delineation of the continental coastlines made

65. See B. Degenhart and A. Schmitt, "Marino Sanudo und Paolino

Veneto," RomischesJahrbuchfurKunstgeschichte, xrv, 1973, 1-137, esp. 60-73.

66. T. Campbell, in The History of Cartography, 435-36.

67. For reproductions, see Degenhart and Schmitt (as in n. 65), figs. 144,

145; P. D. A. Harvey, Medieval Maps, Toronto, 1991, 35, fig. 27; G. Grosjean,

Mappa Mundi: The Catalan Atlas of the Year 1375, Zurich, 1978; and Whitfield

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LOST WHEEL MAP OF AMBROGIO LORENZETTI 297

13 Codex Malabayla, map of the region around Asti, ca. 1353. Asti, Archivio Storico del Comune (from Codex Astensis qui de Malabayla communiter nuncupatur, ed. Q. Sella, Rome, 1880-87, IV, pl. 7; photo: Library of Congress)

Adriatic coastline is "upside down." The quotation marks warn against twentieth-century attitudes. Intended to be rotated, portolan charts have no top or bottom. It is only when there are nonhydrographic details designed to be viewed from one particular direction that we can ascribe any definite orientation to the chart concerned. Examples would be the corner portraits of saints on some of Vesconte's atlases.... For most of the early charts, how- ever and this includes the Carte Pisane [ca. 1290]- there is no way of telling which, if any, of the four main directions they were primarily intended to be viewed from.69

On Catalan-style charts and on complete mappaemundi that absorbed this tradition, the pictorial notation of inland features (mountain ranges, rivers, towns) and of rulers or peoples complements the rotatable writing of coastal place- names. When north is at the top, images in the southern sector are, as a rule, the right way around, and vice versa. Far less consistently, images may also be positioned so that some will appear the right way around when east or west points upward. The principle of rotation was so crucial to this cartographic tradition that symbols for selected towns (vari- ously, on different maps, Venice, Paris, Toulouse, Fez, Baghdad, and on the Catalan Atlas, Beijing) were frequently doubled, thereby allowing them to appear right side up however the map was turned.70 Thus, Italy with Naples at top and Milan at bottom (though disorienting to us) was merely

vols. in 16 pts, Cairo, 1926-51, tV, pt. 2, 1197-98, 1222, 1285-86; A. R. Hinks, Portolan Chart of Angellino de Dalorto 1325 in the Collection of Prince Corsini at Florence, with a Note on the Surviving Charts and Atlases of the Fourteenth Century, London, 1929; M. de la Ronciere and M. Mollat du Jourdin, Les Portulans, Freiburg, 1984, pls. 7, 9, 12, 16; and The History of Cartography, pls. 24, 27.

the logical extension of the boot-shaped peninsula viewed the other way around; neither position was cartographically privileged. Rather the "direction of honor" from which place-names and images would appear correctly oriented at any one time depended on the eye of the viewer. Portolan charts had accustomed Lorenzetti's patrons and audience to picture maps that needed to be rotated to be fully read, and hence to the concomitant inversion of geographic forms, epigraphy, and imagery.7l In sum, this body of cartographic material could well have functioned as an intermediary between the long-familiar tradition of the stationary wall map on which the circle of the world was inscribed and the novelty of an actually revolving wheel.

A map adapted from the tradition of portolan charts would allow for a centralized placement of Italy, hence of Siena, as deduced from eighteenth-century descriptions of the vestige of the disk. Can observers' use of the term carta topografica also be reconciled with a portolan-based map? I believe so, provided that the question turns on the recogniz- ability of selected features rather than on the quantity and pictorial elaboration of chorographic detail.

Superimposed over the geographic delineation of the continental coastlines, particularized vignettes of certain major sites on Lorenzetti's map could have replaced conven- tionalized town symbols. Italian chart makers were the first to incorporate recognizable portraits of major architectural monuments: with a representation of the church and campa-

69. Campbell, in The History of Cartography, 377-78. 70. Grosjean (as in n. 67), 26. 71. The principle of multidirectionality was extended from portolan charts

not only to mappaemundi but also to local maps that integrated the delinea- tion of coastlines, e.g., a mid- 1 5th century map of Italy in the British Library (Cotton Roll XIII.44); see Harvey, 1991 (as in n. 67), fig. 60.

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

298 ART BULLETIN JUNE 1996 VOLUME LXXVIII NUMBER 2

15 Detail of Fig. 14 (photo: Soprintendenza B.A.S.-Siena)

nile of St. Mark's the Pizigani brothers indicated their native

city on their 1367 chart; Francesco Pizigano similarly epito-

mized Venice and, by depicting cathedral and lighthouse,

Genoa in the calendar of his 1373 Atlas.72 Not surprisingly,

though, architectural portraits were at times more evocative

than rooted in observation: on the 1367 chart, for instance, a

cathedral similar to that marking Santiago de Compostela

also appears at St. Catherine's in the Sinai, and the interior

rotunda of a mosque recalling the Dome of the Rock is

transposed to Mecca. By substituting for standard picto-

graphic notation real or imagined likenesses of buildings

with which places were identified, Italian cartographers

modified the Catalan tradition in the direction of greater

local specificity. Conceivably, then, a miniature view of Siena

as in Figure 15, though perhaps larger than other towns,

could have been accommodated within the format of a map

based on the portolan tradition (see, e.g., Fig. 17) as it could

have been within the two sorts of radial composition (the

schematic terraqueous disk or continuous landscape) dis-

cussed above. Although in the end the particular solution adopted by

Lorenzetti remains an open question, the hypothesis of an

artistic link to portolan charts allows his Mappamondo to be

more easily situated within a horizon of expectations defined

by the prehumanist and merchant culture then flourishing in

Italian cities. Rather than insist on the precise geographiccov-

erage of the lost work, perhaps it is best to visualize

Lorenzetti's map as belonging somewhere between two

benchmarks: at one end, the totality of geographical knowl-

14 Sano di Pietro, Saint Bernardino in Glory, ca. 1450. Siena,

Museo del Opera del Duomo (photo: Soprintendenza B.A.S.-

Siena)

72. Campbell, in The History of Cartography, 397, 398 fig. 19.8, and

Degenhart and Schmitt (as in n. 65), 69, 110 fig. 147. Kamal (as in n. 68), tv

pt. 2j 1286, provides a good-size reproduction of a 19th-centuty copy of the

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LOST WHEEL MAP OF AMBROGIO LORENZETTI 299

16 Angelino Dulcert, Portolan chart, 1339. Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale, Res. Ge. B696 (photo: Bibl. Nat.)

17 Gabriel de Vallsecha, Portolan chart, 1447. Paris, Bibl. Nat., Res. Ge. C4607 (photo: Bibl. Nat.)

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

300 ART BULLETIN JUNE 1996 VOLUME LXXVIII NUMBER 2

18 Simone Martini, Maesta, 1315. Sala del Mappamondo, east wall (photo: Fabio Lensini, Siena)

19 Sala del Mappamondo, east and north walls (photo: Fabio Lensini, Siena)

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LOST WHEEL MAP OF AMBROGIO LORENZETTI 301

1. Guidoriccio wall with the lost Mappamondo

2. Maesta

3. Battle of Val di Chiana

4. Battle of Poggio Imperiale

5. Panorama of ideal city and countryside

20 Siena, Palazzo Pubblico, second floor, plan (courtesy: Reena Racki, A.I.A.)

edge that Brunetto Latini evoked when he treated the subject of the mappamundi in his popular encyclopedia LiLivres dou Tresor (early 1260s);73 at the other, the picture teeming with figures, ships, and banners that the Florentine merchant Baldassare degli Ubriachi desired when he commis- sioned four mappaemundi from a Majorcan cartographer and Genoese artist in Barcelona in 1399.74 "Cioe tutta la terra abitabile" was perhaps all that Ghiberti could, or needed to, say. Paradoxically, a portolan-based map may have had special appeal in the communal palace of land-locked Siena. The panoramic sweep of the Sienese contado that Lorenzetti painted in the Sala dei Nove reached the sea at Talamone, a town duly inscribed, by the way, on portolan charts.75 A portolan-based map on the other side of the same wall would have translated this dream-vision into cartographic terms.

The Pictorial Environment If the Mappamondo represented Italy and Siena near the middle of the world, its framing environment in the Palazzo

73. Li Livres dou Tresor, 1.121-24, ed. F. O. Carmody, University of California Publications in Modern Philosophy 22, Berkeley,1948,109-21; or The Book of the Treasure, trans. P. Barrette and S. Baldwin, Garland Library of Medieval Literature, ser. B., xc, New York, 1993, 85-98. On Latini's use of the term mapamunde, see P. A. Messelaer, Le Vocabulaire des idees dans le 'Tresor' de Brunetto Latini, Assen, 1963, 96, 225, 333, 366. See also Latini's II tesoretto, 11. 927-1098, ed. and trans. J. Bolton Holloway, Garland Library of Medieval Literature, ser. A, II, New York, 1981, 49-57. On the prehumanist culture of professional rhetoricians, and Brunetto Latini in particular, as an interpre- tive framework with which to approach Lorenzetti's paintings in the Sala dei Nove, see Q. Skinner, "Ambrogio Lorenzetti: The Artist as Political Philoso- pher," Proceedings of the British Academy, LXXII, 1986,1-56; and Starn, 1992 (as in n. 3), esp. 35-38,4045.

Pubblico suggested the converse, that the world was encom- passed by Siena. The surrounding pictorial decoration in the Sala del Consiglio glorified the city by celebrating its spiritual and earthly power. Since the completion of the building in 1310, the artistic embellishment of the hall proceeded by accretion.76 From the great Maesta to the depiction of subject towns and military triumphs, images added seriatim over time were loosely associated by their shared purpose to exalt the commune.77 Though an ad hoc intervention, the Map- pamondo of 1345 thematically refocused already existing material, and in so doing, created a framework into which subsequent commissions could be integrated. Even if neither the cartographic form nor the geographic content of the map is known for certain, this dynamic process can be explored.

Confronting Simone Martini's Maesta (ca. 1315) on the opposite wall (Figs. 18-20), the Mappamondo took on mean- ing in relation to an inscription in the earlier work. The scroll held by Simone's Christ Child is inscribed with the impera-

74. R. A. Skelton, "A Contract forWorld Maps at Barcelona, 1399-1400," Imago Mundi, xxIIs 1 968, 1 07-1 3; and J. Schulz, "Jacopo de' Barbari's View of Venice: Map Making, City Views, and Moralized Geography before the Year 1500,"ArtBulletin, LX, no.3, 1978, 425-74, esp. 452.

75. With the acquisition in 1303 of the coastal town of Talamone, Siena hoped to win access to the sea. On efforts to make Talamone into a genuine port, derided by Dante (Purg. 13.151-53), see W. Bowsky, A Medieval Italian Commune: Siena under the Nine, 1287-1355, Berkeley, 1981, esp. 175-76, 194,216-17. A plan of Talamone harbor exists from 1306; see Harvey, in The History of Cartography, 46F501, esp.488, 491, fig.20.27.

76. Surveyed in Southard, 213-70. 77. Martindale,1988, 14-15.

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

302 ART BULLETIN JUNE 1996 VOLUME LXXVIII NUMBER 2

The way in which the Mappamondo entered into relation with the Maesta echoes the linkage in religious art between the geographic representation of the earth and the theme of divine justice. Where maps, other geographical images, or rotae symbolic of the earthly world (such as wheels of fortune and labyrinths) were included in church decoration, they were customarily subordinated along a hierarchical axis, longitudinal or vertical, to the supreme action of divine grace.80 Conversely, references to divine justice may appear in maps. The Hereford map (Fig. 21), for example, crowns the disk of the world with a scene of the LastJudgment; later art inverts this formula by incorporating diminutive mappae- mundi into scenes of the Last Judgment.8l The pictorial image of the earth splayed out in the form of a map at the moment of the Last Judgment resonates with biblical meta- phor as found, for example, in Psalms 97:7-8:

let the sea be moved and the fulness thereof: the world and they that dwell therein. The rivers shall clap their hands, the mountains shall rejoice together at the pres- ence of the Lord: because he cometh to judge the earth. He shall judge the world with justice, and the people with equity.

While reminiscent of ecclesiastical programs, the arrange- ment in the Sala del Mappamondo has closer parallels in secular contexts, where the mappamundi symbolizes the power and knowledge of the ruler. The scheme at Siena and two thirteenth-century English examples are mutually illumi- nating.82 The world map that adorned the painted chamber in Westminster Palace was most likely displayed on the short west wall across from the royal bed in the far northeast corner of the room. As the focus of the sovereign's gaze, the world was thereby offered up to his domination, his execution of judicial kingship. Similarly in the great hall of Winchester Castle, the map was probably located on the west wall opposite the point of highest status at east. The king seated on the royal dais therefore held the world in thrall in his direct line of sight. In Siena, the Virgin took the place of the monarch. Thus the city-republic expressly acknowledged as ruler only the Queen of Heaven, to whom it had commended itselfbefore the Battle of Montaperti in 1260.83 The cosmological-eschatological framework that struc- tured church architecture and its decoration was, in the secular world, the prerogative exclusively of kings. The de'tournement of this structure in a communal palace went to legitimize a republican form of government whose de jure

carved throne at the apex of the east-oriented oval; the throne frames a scene of the Fall. See "Die Evesham Weltkarte von 1392: Eine mittelalterliche Weltkarte im College of Arms in London: Von der Universalitat zum Anglozentrismus," Cartographica Helvetica, IX, 1994, 17-22; and idem, "The Evesham World Map: A Late Medieval English View of God and the World," Imago Mundi, XLVII, 1995, 13-33. The map is reproduced in color in Whitfield 82. I have treated both monuments (with bibliography) at greater length in 83. A. Perrig, "Formen der politischen propaganda der Kommune von Siena in der ersten trecento-halfte," in Bauwerk und Bildwerk im Hochmittelal- ter: Anschauliche Beitrage zur Kultur-und Sozialgeschichte, ed. K. Clausberg et al., Giessen, 1981, 213-34, esp. 222-27.

(as in n. 64), 25.

21 Mappamundi, Hereford Cathedral, begun 1277-83 and completed ca. 1289, facsimile (photo: by permission Dean and Chapter of Hereford Cathedral)

tive that opens the Book of Wisdom: "Diligite iustitiam, qui iudicatis terram" "Love justice, you that are the judges of the earth." Christ, quoting Solomon's words, addressed those who governed; the map showed the earthly world to which justice, human and divine, pertains. Insofar as the Mappamondo realized the last word of Christ's utterance, its symbolic function exceeded its geographic boundaries. The two short ends of the hall thereby established a cosmic frame for those who occupied the space between. At east, the Queen of Heaven appears accompanied by the court of saints, the perfect just, among whom four intercede on behalf of the Sienese commune;78 at west, Siena appeared at the heart of the created world submitted to judgment. The Virgin, sternly admonishing would-be traitors, bestows her favor on those who follow Wisdom's counsel: who eschew self-interest, practice virtue, uphold the law, and enforce it equitably. From Wisdom, justice emanates. And justice is the principle of order in the world.79

78. Ibid., 15, 204-9. 79. To the extent that I propose the inscription on the Christ Child's scroll as one of the connecting links between the Mappamondo and the Maesta, I am greatly indebted to Chiara Frugoni's discussion of the Wisdom text in the Sala della Pace frescoes: "The Book of Wisdom and Lorenzetti's Fresco in the Palazzo Pubblico at Siena," Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, xxxv, 1972, 145-62; and eadem, A Distant City, trans. W. McCuaig, Princeton, NJ ., 1991, 118-88. 80. I develop this point somewhat more fully in Kupfer, 275-76.

Kupfer, 277-79.

81. Sterling (as in n. 1), 72-76 with ills. Peter Barber suggests that a little-known, Higden-type mappamundi produced ca. 1392 at Evesham Abbey (London, College of Arms, Muniment Room 18/19) incorporates the theme of the world's submission to divine judgment by representing an elaborately

This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Thu, 23 May 2013 19:17:47 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LOST WHEEL MAP OF AMBROGIO LORENZETTI 303

foundation was strenuously debated and whose de facto existence was precarious. Brought tightly into relation by Lorenzetti's Mappamondo, the two ends of the hall delimited a space that made republican government when guided by wisdom and practiced with justice the guarantor of order in the world.

Whereas the confrontation of signs across space bound the world to a higher, transcendent authority, theirjuxtaposition on the west and north walls spoke to the bonds of earthly authority. The map's display amidst images of civic subjec- tion and military victory exploited hierarchical principles, particularly in its subordination to the mounted warrior. Yet the lateral framing of the map in its broadest sense also allowed for a more diffuse play of ideas.

So far as has been determined, it seems that the Map- pamondo superseded one of the seven or more subject towns painted on the walls of the Sala del Consiglio. Three castra, if not more, were on view by 13 14 (Giuncarico plus at least two earlier ones); four more were added in 1330 (Montemassi, Sassoforte) and 1331 (Arcidosso, Castel del Piano).84 The identity of the town in the recently discovered fresco below the Guidoriccio is much debated; whether the scene repre- sents the surrender of Giuncarico,85 or that of Arcidosso,86 is not relevant to my argument, however, and may therefore be left open. A portrait of Montemassi (repainted in the quat- trocento) was incorporated into a scene showing it under siege by Guidoriccio. Whether this scene corresponds to the image of Montemassi for which Simone Martini was paid in 1330, or whether it replaced that commission along with other towns in the series can also be left aside. In any event, it seems likely that some of the towns possibly occupying the area now covered by Sodoma's frescoes,87 possibly filling the adjacent lateral wall now taken up with frescoes of the battles of Val di Chiana (ca. 1364) and Poggio Imperiale (1480)88- were still visible in 1345, and thus constituted part of the decoration when the map was first displayed.