The king's animals and the king's books: the illustrations for the Paris Academy's Histoire des...

-

Upload

oregonstate -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of The king's animals and the king's books: the illustrations for the Paris Academy's Histoire des...

This article was downloaded by: [Oregon State University]On: 24 August 2014, At: 18:35Publisher: Taylor & FrancisInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Annals of SciencePublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tasc20

The king's animals and the king's books:the illustrations for the Paris Academy'sHistoire des animauxAnita Guerrini aa Oregon State University , USAPublished online: 15 Jul 2010.

To cite this article: Anita Guerrini (2010) The king's animals and the king's books: theillustrations for the Paris Academy's Histoire des animaux , Annals of Science, 67:3, 383-404, DOI:10.1080/00033790.2010.488154

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00033790.2010.488154

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoeveror howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to orarising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

The king’s animals and the king’s books: the illustrations for the ParisAcademy’s Histoire des animaux

ANITA GUERRINI

Oregon State University, USA

Summary

This essay explores the place of natural philosophy among the patronage projectsof Louis XIV, focusing on the Memoires pour servir a l’histoire naturelle desanimaux (or Histoire des animaux) of the 1670s, one of a number of works ofnatural philosophy to issue from Louis XIV’s printing house. Questions particularto the Histoire des animaux include the interaction between text and image, thecredibility and authority of images of exotic animals, and the relationship betweencomparative anatomy and natural history, and between human and animalanatomy. At the same time that the Histoire des animaux contributed to Jean-Baptiste Colbert’s management of patronage and of Louis’s image, it was a workof natural philosophy, representing the collaborative efforts of the new ParisAcademy of Sciences. It examined natural history and comparative anatomy innew ways, and its illustrations broke new ground in their depiction of animals in anatural setting. However, the lavishly formatted books were presentation volumesand did not gain wide circulation until their republication in 1733. Sourcesconsulted include Colbert’s manuscript memoires on the royal printers andengravers.

Contents

1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3832. The Paris Academy and its publication projects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 384

3. The Histoire des animaux . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 385

4. The animals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 386

5. The book and its illustrations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 388

6. Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 403

1. Introduction

In the 1670s, the French royal printing office published six illustrated folio

volumes of aspects of the work of the Paris Academy of Sciences. Five of them were

elephant folios, 55 cm long. These included two editions of the Memoires pour servir a

l’histoire naturelle des animaux (which I will henceforth refer to as the Histoire des

animaux), published in 1671 and 1676; Jean Picard’s Mesure de la terre, on the

circumference of the earth, also published in 1671 and often bound with the Histoire

des animaux; and the Memoires pour servir a l’histoire des plantes, first published in

1676 and reissued in 1679. Another large folio (58 cm) from 1676 was the collected

pamphlets in the Recueil des plusieurs traitez de mathematique. In addition, a

description of Christian Huygens’s pendulum clock, Horologium oscillatorium,

appeared as a regular folio in 1673.

Annals of Science ISSN 0003-3790 print/ISSN 1464-505X online # 2010 Taylor & Francishttp://www.tandf.co.uk/journals

DOI: 10.1080/00033790.2010.488154

ANNALS OF SCIENCE,

Vol. 67, No. 3, July 2010, 383�404

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

All of these books were illustrated with detailed, full-page engravings by some of the

best-known artists of the time. This essay focuses on the Histoire des animaux and its

place among the artistic and publishing projects of the crown. In addition, I will explore

questions that are particular to its subject matter: the interaction between text and image,

the credibility and authority of its images of exotic animals, and the relationship between

comparative anatomy and natural history, and between human and animal anatomy.

2. The Paris Academy and its publication projectsThe Paris Academy of Sciences was founded in 1666 at the instigation of Louis

XIV’s chief minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, who convinced the king of the utility and

the prestige that such an academy would bring, as part of his plan to consolidate

cultural patronage under the crown. Following the trial and condemnation of the

former royal minister Nicolas Fouquet in 1661, a patronage vacuum existed in French

society, which Louis and Colbert endeavoured to fill during the 1660s.1 Unlike the

Royal Society in London, the Paris Academy was not a voluntary body of dues-paying

members who elected each other and held essentially equal status, but a small

appointed body of between 19 and 34 members who received royal pensions of varying

amounts based on their reputations. Colbert recruited some of the top names in

European science, including the Dutch natural philosopher Christiaan Huygens, the

Italian astronomer Gian Domenico (soon to become Jean-Dominique) Cassini, and

the Danish astronomer Ole Rømer, providing them with housing as well as generous

pensions. The Academy’s sections on ‘physique’ (which included anatomy, botany, and

chemistry) and ‘mathematique’ (which encompassed mechanics and astronomy) met

on different days, initially in rooms at the Bibliotheque du roi on the rue Vivienne, near

the present Bibliotheque Nationale-Richelieu, and later at the Louvre.2

Although, unlike the Royal Society, the Academy did not have an official journal

until 1699, publication was nonetheless part of its mission from the outset. Members

published articles in the newly-founded Journal des scavans as well as in the

Philosophical Transactions and other journals. In addition, the Academy began to

issue pamphlets on its work, beginning only a few months after its initial meetings early

in 1667. From Huygens appeared a short Relation d’une observation faite a la

Bibliotheque du Roy, a Paris, le 12. may 1667. sur les neuf heures du matin, d’un halo ou

couronne a l’entour du Soleil; avec un discours de la cause de ces meteores, & de celle des

parelies. Later that year, Claude Perrault, who dominated the ‘physique’ section,

described dissections of a thresher shark and a lion in an illustrated pamphlet

addressed to his fellow academician Marin Cureau de la Chambre. Another pamphlet,

with five further descriptions, appeared in 1669. This quarto pamphlet was illustrated

with fold-out engravings and printed by Frederic Leonard, ‘imprimeur ordinaire’ to

the king.3

1 Peter Burke, The Fabrication of Louis XIV (New Haven, 1992), 49�50.2 Roger Hahn, The Anatomy of a Scientific Institution: The Paris Academy of Sciences, 1666�1803

(Berkeley, 1971), 4�5, 16�7.3 [Claude Perrault], Extrait d’une lettre ecrite a Monsieur de La Chambre, qui contient les observations qui

ont este faites sur un grand poisson disseque dans la Bibliotheque du Roy, le 24e juin 1667.*Observations quiont este faites sur un lion disseque dans la Bibliotheque du Roy, le 28e juin 1667, tirees d’une lettre ecrite a M.de La Chambre (Paris, 1667). This pamphlet was also a quarto, but the illustrations were page-sized, notfold-out. The 1669 publication was: [Claude Perrault], Description anatomique d’vn cameleon, d’vn castor,d’vn dromadaire, d’vn ours, et d’vn gazelle (Paris, 1669).

384 A. Guerrini

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

However, plans were already unfolding for a much bigger publication project. The

Bibliotheque du roi had moved to its new quarters in the rue Vivienne in 1666, a

building which soon also housed the Imprimerie du roi, the royal printing house

which had been founded by Richelieu in 1640 and had formerly been located in the

Louvre.4 The printing house employed a battery of artists and engravers, including

Louis Chatillon, Sebastien LeClerc, Abraham Bosse, Jacques Bailly, and Israel

Sylvestre. At the end of 1667, a ruling of the Council of State allowed Colbert to

centralise control of engraving under his domain, and only engravers of his choosing

could depict the king’s objects. Included among these were ‘les figures des plantes et

animaux de toutes especes et autres choses rares et singulieres’.5 Already busily

producing engravings of Louis’s chateaux, his artworks, views of the towns of France,

and images of Versailles, these artists now turned to drawing and engraving plants,

animals, and astronomical observations. Among these, LeClerc, Bailly, and Bosse

particularly worked on the animal studies. Two years after the second pamphlet

appeared, a much different publication emerged from the Imprimerie du roi.

3. The Histoire des animauxBy 1670, the atelier on the rue Vivienne had produced hundreds of engravings. A

memoire from February 1670 from Colbert to Charles Perrault, brother of Claude

and secretary of the ‘petite academie’ of Belles-Lettres, and Pierre Carcavi, head of

the Bibliotheque du roi, discussed the publication of these engravings.6 Colbert’s

memoire is speculative and proposes several ideas for publication, but it reveals the

place of the Academy’s work among the other artistic and scientific projects of the

crown. One plan proposed to publish groups of engravings on various topics in

annual volumes which would display the work of the past year. So, for example, at the

end of 1670, the king would receive a volume composed of 10 or 12 engravings of

animals and 12 to 15 of plants, along with a variety of other images to round out a

volume of 40 or 50 plates, including ancient medals from the royal cabinet, the King’s

busts and statues, carousels, tapestries, royal houses, ‘and all other things of the same

genre’. At the end of 10 or 12 years, several of these volumes would compose an

entire history ‘de toute sorte de science’.

This plan was soon abandoned in favour of composing separate volumes on each

topic. But it is clear that Colbert viewed the images that eventually appeared in the

Histoire des animaux as prior to any text. The composer of the volumes should be ‘a

clever man’ who can get all the plates in the right order and in a uniform size and

quality. As if as an afterthought, the memoire adds, ‘choose someone else to make the

text and the descriptions’. That the seven engravings of animals listed had already been

published in the pamphlets of 1667 and 1669 is not mentioned, although it is

acknowledged that two of the engravings are in quarto format (presumably those from

1667, which were not fold-outs) and would need to be enlarged for a uniform folio.

4 Simone Balaye, La Bibliotheque Nationale des origines a 1800 (Geneva, 1988), 80�1.5 Marianne Grivel, ‘Le Cabinet du Roi’, Revue de la Bibliotheque nationale, 18 (1985), 36�57, at 38. On

the status of the graveurs du roi, see Merilyn Savill, ‘The Triple Portrait of Pierre Bernard. Gerard Edelinckand Nicolas de Largilliere and the Debate in the French Academy in 1686 over the Status of Engravers’,Melbourne Art Journal, 5 (2001), 41�52.

6 The memoire, which is unpaginated, is ‘Memoire que Monseigneur a dresse touchant la publicationdes ouvrages ou Il y a des Planches gravees’, Archives nationales, Paris, MS O1 19642, Cotte 2, dated 22 feb.1670.

385The king’s animals and the king’s books

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

Colbert also suggested that if the number of engravings of animals and plants

were insufficient to make two volumes, they could be joined in one, consisting of 15

or 20 animals and 20 or 30 plants. But the 1671 volume contained only animals, with

17 descriptions of 16 different species. By 1670, most of these animals had already

been dissected. In the 1669 pamphlet, Perrault indicated as much, noting that the five

descriptions he included were those for which he had illustrations: ‘I hope to give

others when the engravers provide the plates’. 7

In Colbert’s memoire, however, the images retained their priority: ‘As far as the

anatomical dissections Mr Perrault physician who has done the seven which are

printed can continue to do them more easily than another because he did or saw done

the dissections of the animals or drew the whole and the parts . . . He also [will take]

so much care to make understood the observations he has made’. Perrault’s

anatomical skill, then, was valuable mainly because he could produce the product

of the dissection which led to better engravings, and belatedly, because he could

explain the meaning of the images.

The Memoires pour servir a l’histoire naturelle des animaux was the first of several

presentation volumes derived from the work of the Paris Academy. It served a

number of functions: it was a work of art, printed on fine paper, with full-page

illustrations of each of the animals described, and bound in red morocco with the

fleur-de-lis of the crown embossed in gold.8 The engravings alone cost over 4000

livres.9 It was a patronage object, too rare and expensive for the open market; the 200

copies of the book were given away to select individuals, including the members of

the Paris Academy.10 A very public example of Louis XIV’s patronage of that

Academy, it was, in addition, a contribution to the new natural philosophy that the

Academy pursued, based on collective witnessing and repeated observations.11 This

volume was reissued in a revised and expanded form, with 31 descriptions of 29

different species, in 1676. A third volume was planned but did not appear, for various

reasons, until 1733.

4. The animals

In the Histoire des animaux, Claude Perrault and other members of the Paris

Academy of Sciences described a number of exotic animals that came from Louis

XIV’s menageries at Versailles and Vincennes. These animals had come to France as

gifts from foreign rulers, as the spoils of trade and exploration, and by purchase.12

7 [Claude Perrault], Description anatomique d’vn cameleon, (note 3), Preface: ‘Ces cinq Descriptions quej’ay mise dans ce Recueil, sont celles des animaux dont j’ay trouve les figures gravees. I’espere de donner lesautres a mesure que les Graveurs fourniront les planches’.

8 The four copies I have seen of the two editions have all had similar binding. Grivel (note 5) givesdetails of the paper and binding.

9 For the sake of comparison, the Academie’s chief anatomist in 1680, Joseph-Guichard Duverney,earned a yearly pension of 1500 livres.

10 Two hundred copies were ordered of the 1676 edition: ‘Memoire de toutes les Planches qui ont estegravees pour le Roy, depuis l’annee 1670 jusqu’au 15 may 1675’, Archives nationales, MS O1 19642, Cotte 2.

11 [Claude Perrault], Memoires pour servir a l’histoire naturelle des animaux (Paris, 1676), ‘Preface’, notpaginated. Henceforth cited as Histoire des animaux.

12 E.T. Hamy, ‘The Royal Menagerie of France and the National Menagerie established on the 14th ofBrumaire of the Year II (November 4, 1793)’, Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the SmithsonianInstitution (Washington, DC, 1898), 507�17, at 511.

386 A. Guerrini

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

Exotic animals as a form of diplomatic exchange dated back to antiquity, and the

Histoire des animaux certainly partook of the seventeenth century interest in the

unusual and rare, what Perrault called ‘singularitez’. Although the economic value of

plants made them more common objects of early modern naturalists’ regard, animals

provided more visible evidence of royal and colonial power when they were brought

back to Europe. Aristocrats and monarchs had long collected rare animals for

display and for combat, and early modern monarchs believed they recreated imperial

Roman practices.13 In 1661, at the beginning of his personal rule following the death

of Cardinal Mazarin, Louis XIV renovated Mazarin’s menagerie near the Chateau de

Vincennes from a quasi-farm to a staging ground for ferocious animals who were

intended for displays of combat. Some of the animals, including the lion that was

dissected in 1667, were brought to Vincennes from an older menagerie at the Tuileries

garden, near the Louvre.14 When the king began to build the palace of Versailles in

the 1660s, he specified that the plans should include a menagerie, and the first

animals arrived in 1664. The animals that came to these menageries were difficult and

expensive to obtain, transport and maintain, making them even more desirable.

They included a wide variety of species: not only the large fierce animals popular in

earlier times, but other animals celebrated for their rarity and beauty, particularly

birds.15

In the menagerie, the animals existed torn from their natural habitats. Inevitably,

they died, particularly over the course of the Paris winters.16 The Paris Academy was

founded a few years after the Versailles menagerie opened. Claude Perrault, a man of

the court, recognised the multiple values these exotic animals possessed, and

conceived of the notion of dissecting them when they died and therefore gaining

new knowledge from them; the first dissections, of the shark and the lion, took place

within a few days of each other in June of 1667.17 From then onward, when an

animal died in one of the menageries, its body could be conveyed for dissection to the

Academy’s quarters at the Bibliotheque du roi or more often to the private quarters

of the Academy’s anatomists. Rare or unusual animals found elsewhere also made

their way to the rue Vivienne. But the elephant that died at Versailles in 1681

underwent dissection on site, witnessed by the King himself.

The animals in the Histoire des animaux were therefore not ordinary animals, and

they held a variety of roles in Louis’s universe. In representing the gift economy of

diplomatic exchanges and indicating the reach of the French imperium, they

displayed Louis’s power. In addition, animals played important roles in establishing

13 Wilma George, ‘Sources and Background to Discoveries of New Animals in the Sixteenth andSeventeenth Centuries’, History of Science, 18 (1980), 79�104; Eric Baratay and Elisabeth Hardouin-Fugier, Zoo: A History of Zoological Gardens in the West, trans. Oliver Welsh (London, 2002), 17�28.

14 Gustave Loisel, Histoire des menageries, de l’Antiquite de nos jours, 3 vol. (Paris, 1912), 2, 96�7.15 Loisel (note 14), 103 and ch. 7, passim; Baratay and Hardouin-Fugier (note 12), 35�6, 39. On the gift

economy and early modern science, see Paula Findlen, ‘The Economy of Scientific Exchange in EarlyModern Italy’, and William Eamon, ‘Court, Academy, and Printing House: Patronage and ScientificCareers in Late Renaissance Italy’, in Patronage and Institutions, edited by Bruce T. Moran (Woodbridge,Suffolk, 1991), 5�24 and 25�50. It is to be noted, however, that both these articles refer to sixteenth-centuryItaly, whose circumstances do not directly map onto seventeenth-century France; see also RolandMousnier, L’age d’or du mecenat (1598�1661) (Paris, 1985).

16 Histoire des animaux (note 11), ‘Avertissement’ (not paginated).17 [Perrault], Extrait d’une lettre (note 2); oddly, Fontenelle’s Histoire of the Academy ignores these,

claiming the first dissection was of a beaver in 1668: Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle, Histoire de l’AcademieRoyale des Sciences, 1666�1699, vol. 1 (Paris, 1733), 52.

387The king’s animals and the king’s books

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

the public image of the king. The taming of powerful wild animals in the menageries

paralleled the regulation of the aristocracy by the civilising process of the court. The

menageries and the Academy also brought prestige to the court, and animal

symbolism entered into many aspects of Louis’s image-making apparatus, ‘le roi

machine’.18

Publication of the new knowledge gained from the Academy’s dissections would

benefit the Academy and the wider republic of letters, and also fulfil scientific and

symbolic functions. Perrault was well aware of the patronage value of the resulting

work. The existence of the Academy and its work asserted Louis’s control of natural

philosophy while at the same time it declared the high status of natural philosophy as

an activity that the court supported. Moreover, the paper zoo that comprised the

Histoire des animaux functioned as a virtual menagerie that could extend the reach of

Louis’s glory beyond those few who could actually visit Versailles or Vincennes and

see the animals themselves.19 Images of animals from a number of publication

projects, including the Histoire des animaux, also appeared in works of art that

celebrated Louis’s reign. Indeed, animals were everywhere at Versailles, outdoors in

fountains and statues, and indoors in paintings and tapestries. They also played roles

in the spectacles that displayed the king’s glory.20

5. The book and its illustrations

While the pamphlets from the 1660s were strictly descriptive, the volumes from

the 1670s acknowledged this symbolic role. Perrault’s preface to the 1671 Histoire

des animaux effusively praises Louis, employing a much-used comparison to

Alexander the Great. This theme had been established in a series of paintings

(and later tapestries) by the court artist Charles LeBrun, beginning in the early

1660s.21 No detail was too small for ‘le roi-machine’, and the order of presentation

in the Histoire des animaux played further on the Alexander theme. The order was

not the order of the pamphlets, or the order of dissection. Instead, the lion came

first, introduced with a headpiece which coupled it with royal symbols. Louis, like

Alexander, often used lion imagery. Perrault introduced the comparison to

Alexander toward the end of the preface, and the reader would then turn the

page to the magnificent full-page image of the lion, followed by the symbolic

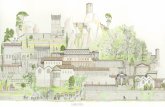

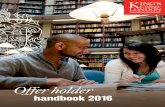

headpiece (Figures 1 and 2).

Perrault also claimed in the same preface that this work was one of natural

philosophy, although it was a natural philosophy based on observation and

experiments rather than causal theories.22 Indeed the animal project contributed to

the larger anatomy program of the Academy, which included the dissection of

18 On the making of the image of Louis, see Burke, Fabrication (note 1); Jean-Marie Apostolides, Le roi-machine. Spectacle et politique au temps de Louis XIV (Paris, 1981).

19 See Anita Guerrini, ‘The ‘‘Virtual Menagerie’’: The Histoire des animaux project’, Configurations, 14(2006), 29�41.

20 Aurelia Gaillard, ‘Bestiaire reel, bestiaire enchante: les animaux a Versailles sous Louis XIV’, inL’animal au XVII e siecle, edited by Charles Mazouer (Tubingen, 2003), 185�98.

21 Burke (note 1), 3, 28, 35; K. Corey Keeble, ‘The sincerest form of flattery. 17th-century Frenchetchings of the battles of Alexander the Great’, Rotunda. The Bulletin of the Royal Ontario MuseumToronto, 16 (1983), 30�5.

22 For further discussion of Perrault’s method, see Anita Guerrini, The Courtiers’ Anatomists: Animalsand Humans in Louis XIV’s Paris, chapter 1 (forthcoming).

388 A. Guerrini

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

humans and a variety of other animals. But the distribution of the volume, as well as

its lavish format, militated against an ideal of the public distribution of ideas that the

new journals of natural philosophy promoted. The print run of 200 copies was small

even by seventeenth-century standards, where average print runs were more like 1000

(under 800 copies were considered uneconomical by the London Stationers’

Figure 1. Lion [Claude Perrault], Memoires pour servir a l’histoire naturelle des animaux(Paris, 1676). Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering & Technology.

389The king’s animals and the king’s books

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

Company).23 The famous Hortus Eystettensis, published in 1613 and even bigger, at

57 by 46 cm, than the Histoire des animaux, ran to 300 copies, with hand-coloured

plates*and all were sold, at the then-outrageous price of 500 florins a copy.24 We still

do not know enough about the role played by books in the gift economy of early

modern Europe. More attention has been paid to objects, including the animals in

the royal collections.

None of the copies of the Histoire des animaux were sold. The Philosophical

Transactions reviewed the 1669 pamphlet soon after it appeared, but its review of

the 1671 Histoire des animaux only appeared in 1676, an indication perhaps of the

difficulty in obtaining a copy of the volume. Alexander Pitfeild, who translated the

1671 volume into English in 1687, echoed this difficulty: ‘so Magnificently [were

they] set forth . . . as . . . not to be designed for common sale . . . they became

presents only from the King, or the Academy, to persons of the greatest quality,

and were hereby rendered unattainable by the ordinary Methods for other Books’.

Pitfeild intended his translation, which appeared in a smaller folio volume with re-

engraved copies of the illustrations, to make the work more accessible to natural

philosophers, since, as he noted, it contained ‘very Pertinent, as well as Curious

Observations’.25 The Paris Academy seems to have recognised the problem of

accessibility when it reissued the 1669 pamphlet in 1682, again as a quarto with fold-

out illustrations, accompanied by an essay on vision by academician Edme

Figure 2. Headpiece to ‘Lion’ [Claude Perrault], Memoires pour servir a l’histoire naturelledes animaux (Paris, 1676). Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering &Technology.

23 John Jowett, ‘For many of your companies: Middleton’s early readers’, in Thomas Middleton: TheCollected Works, edited by Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino (New York, 2007) 286�327, at 290.

24 British Library Online Gallery, ‘Hortus Eystettensis’ http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/landprint/hortus/index.html, accessed 10 September 2009. There was also a black-and-white versionwhich sold originally for 35 florins. For an overview of the role of images in the era of the ScientificRevolution, see Renzo Baldasso, ‘The Role of Visual Representation in the Scientific Revolution: aHistoriographic Inquiry’, Centaurus, 48 (2006), 69�88.

25 [Claude Perrault], Memoir’s [sic] for a Natural History of Animals. Containing the AnatomicalDescriptions of Several Creatures dissected by the Royal Academy of Sciences at Paris. Englished byAlexander Pitfeild (London, 1688). See also Roger Chartier, The Order of Books, trans. Lydia G. Cochrane(Stanford, 2004), 14�7.

390 A. Guerrini

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

Mariotte. However, a ‘popular’ edition of the volumes from the 1670s did not

materialise for many years.

As well as situating the Histoire des animaux within the royal universe, Perrault’s

introduction argued for the credibility and legitimacy of the Paris Academy as a

scientific institution. It established several important principles for animal observa-

tion, description, and anatomy, blurring the boundaries between descriptive natural

history and analytical natural philosophy by establishing observational data as

sufficient in itself to make knowledge, without an overarching causal theory.26 These

principles were distinctly anti-Cartesian, perhaps in keeping with the Paris

Academy’s ban on Cartesians or other system-builders.27 Perrault refused to

speculate about causes or to generalise from particulars or indeed to state any

general principles at all. He was less concerned with animal mechanism than

with animal structure and behaviour, the objects of natural history rather than

natural philosophy. Nonetheless, Perrault characterised the work as one of natural

philosophy. Each animal he described was unique, and the duty of the natural

philosopher, he said, was first simply to describe. Any attempt at generalisation was

premature. While the exotic animals in the Histoire des animaux were indeed unique,

Perrault based his assertion on more than circumstance.

Perrault had several predecessors in his inquiries into animal anatomy, but the

Histoire des animaux differed from contemporary accounts either of natural history

or of comparative anatomy.28 Unlike most naturalists, Perrault paid much more

attention to anatomy than to classification, carefully describing the internal structure

of each specimen. He refused to attempt a classification of the motley assortment of

animals he chronicled or to endorse any of the current systems of taxonomy. Indeed,

in the ‘Avertissement’ to the 1676 edition, he noted that as more animals of the same

species were made available, their descriptions had been rewritten ‘because it is

important to note as much as possible the differences and the similarities that one

often encounters in animals of the same species’.29 The order of presentation, with

the exception of the lion, followed no discernable order or system of classification.30

Unlike most comparative anatomists, however, Perrault and company described a

wide variety of different animals rather than focusing on a single kind or a single

organ or system*reflecting his sources in Louis’s menageries*and discussed habitat

and behaviour as well as anatomy.31

Perrault noted the particular care he and his collaborators at the Academy took

with the verbal descriptions of exotic animals, ‘marking the size and proportion of all

26 On these issues see Guerrini, Courtiers’ Anatomists (note 22) and Gianna Pomata, ‘Praxis Historialis:The Uses of Historia in Early Modern Medicine’, in Historia: Empiricism and Erudition in Early ModernEurope, edited by Gianna Pomata and Nancy G. Siraisi (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2005), 105�46.

27 Hahn (note 2), 15.28 On the definition of comparative anatomy, see F.J. Cole, A History of Comparative Anatomy from

Aristotle to the Eighteenth Century (1949, rpt. New York, 1975).29 Histoire des animaux (note 15), ‘Avertissement’: ‘qu’il etoit important de marquer autant qu’il seroit

possible les differences & les convenances qui se rencontrent souvent dans les Animaux d’une mesmeespece’.

30 Histoire des animaux (note 15), ‘Preface’, not paginated. The preface in the 1671 and 1676 editions areidentical. The order of dissection can be discerned via the manuscript Proces verbaux of the Paris Academy,contained in the Archives, Academie des sciences, Paris.

31 Accounts of comparative anatomy include Cole, History of Comparative Anatomy (note 28); HowardAdelmann, Marcello Malpighi and the Evolution of Embryology, 5 vol. (Ithaca, NY, 1966); M.D. Grmek, Lapremiere revolution biologique (Paris, 1990); Luigi Belloni, ‘Severino als Vorlaufer Malpighis’, Nova actaLeopoldina, n.s. 27 (1963), 213�24.

391The king’s animals and the king’s books

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

the parts which are seen without dissection, because these are as little known as all that

is enclosed within’.32 The credibility of these descriptions hinged on the collaborative

ideal of the Paris Academy, according to which all of its members contributed to all of

its projects. The 1671 edition of the Histoire des animaux listed no author on the title

page. The 1676 edition was ‘Dressez par M. Perrault’, a term that could mean ‘to draw

up’ but also had the connotation of putting together or compiling. Manuscript

evidence provides compelling proof that Perrault in fact wrote much if not all of the

text.33 ‘What is most significant about these memoires’, wrote Perrault in his preface,

‘is this irreproachable witness to a certain and recognised truth’. While a single

individual’s observations might be clouded by opinion or fixed ideas, the Histoire des

animaux only contained facts that had been verified by ‘an entire Company, composed

of those who have eyes to see these sorts of things, otherwise than most people, and

they also have hands to look for [these things] with more dexterity and more success’.

Thus collective verification guaranteed the credibility of the descriptions in the

Histoire des animaux. In addition, the members of the Academy were not ordinary

‘merchants and soldiers’ who might make observations by chance, but individuals who

have the ‘esprit de Philosophie’ as well as the patience to observe all the ‘particularitez’

of each animal. 34

Perrault’s insistence on precision and direct observation complicates Lorraine

Daston and Peter Galison’s account of the development of objectivity in their recent

book Objectivity. Daston and Galison argue that what they call ‘truth-to-nature’, an

emphasis on sustained observation with the result of picturing an exemplar of a type,

developed in the early eighteenth century in reaction to the emphasis of seventeenth-

century naturalists on singularity and anomaly.35 Perrault’s emphasis on the singular

individual and his hesitation to describe a general type seem to fit Daston and

Galison’s characterisation of the pre-eighteenth century naturalist, but Perrault may

be more fruitfully seen as a transitional figure who sought to find regularity by

sustained observation of multiple examples of the singular, to go beyond natural

history to the new knowledge that characterised natural philosophy. Perrault’s

epistemological modesty was shared by Buffon, who in the early volumes of the

Histoire naturelle similarly forswore any attempts to classify. Only individuals carried

ontological meaning.36

32 Histoire des animaux (note 11), ‘Preface’: ‘Dans la Description des Animaux rares, & qui viennent desPaıs estrangers, nous avons apporte vn grand soin a bien depeindre leur forme exterieure, & a marquer lagrandeur & la proportion de toutes les parties qui se voient sans dissection; parce que ce sont des chosespresque aussi peu connues que tout ce qui est enferme au dedans’.

33 Dictionnaire de l’Academie francaise (Paris, 1694), s.v. dresser. Dossiers for Perrault and for theHistoire des animaux in Archives, Academie des sciences include drafts in Perrault’s hand. On theAcademy’s collaborative ideal, see particularly Alice Stroup, A Company of Scientists (Berkeley, 1990).

34 Histoire des animaux (note 11), ‘Preface’: ‘Ce que nos Memoires ont de plus considerable, est cetemoignage irreprochable dvne verite certaine & reconnue . . . nos Memoires, qui ne contiennent point defaits qui n’aient este verifies par toute vne Compagnie, compose de gens qui ont des yeux pour voir cessortes de choses, autrement que la plupart du reste du monde, de mesme qu’ils ont des mains pour leschercher avec plus de dexterite & de succes’.

35 Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, Objectivity (New York, 2007), ch. 2, passim. Daston made asimilar argument in Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park, Wonders and the Order of Nature (New York,1998), chapter 9, passim. See also Nancy Anderson, ‘Eye and Image: Looking at a Visual Studies ofScience’, Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences, 39 (2009), 115�25.

36 Georges-Louis leClerc, Comte de Buffon, Histoire naturelle, generale et particuliere, avec la descriptiondu Cabinet du Roy, vol. 1 (Paris, 1749), ‘Premier discours’, 1�62.

392 A. Guerrini

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

The illustrations demonstrated this intersection of natural history and natural

philosophy in a number of ways: in their format, in their style, and in their

relationship to the text. A full-page illustration accompanied each of the animals

discussed, displaying the animal in life as well as some of its dissected parts, which are

presented in trompe l’oeil fashion as another sheet pinned to the underlying image.

Perrault also employed this format in his translation of the work of the Roman

architect Vitruvius, similarly to show the interior and exterior simultaneously.37

While illustrations were, in Brian Ogilvie’s words, ‘practically ubiquitous among

naturalists’, they were much less common among anatomists, to whom verbal

description was at least as important.38 A majority of texts on human anatomy in

this period had few or no illustrations. The best-known work of comparative

anatomy of the era, Marco Aurelio Severino’s Zootomia democritaea (1645)

illustrated only isolated dissected parts.

Perrault’s inclusion of anatomical details therefore was a conscious attempt to

reach beyond natural history to natural philosophy and its discussion of causes. The

dissected parts on view in the Histoire des animaux consisted of individual organs

and structures which demonstrated particular questions; so the digestive system

of the chameleon was shown to disprove the notion that the animal did not eat

(Figure 3). The trompe l’oeil format was lost in later reprints such as the 1733�1734

quarto reprint which separated the two images, but it was retained, though in a

somewhat smaller size, in the 1688 English translation.39 Severino’s work had no

images of entire animals, but the Histoire des animaux showed both the whole and the

parts. Like the cabinet, where one might view both a whole specimen and various

parts, the illustrations in the Histoire des animaux revealed more than the animal in

the menagerie, or a single dissected specimen, could do.

Unlike the cabinet, however, the illustrations in the Histoire des animaux also

depicted the live animal in a natural setting. This style departed from most previous

works of natural history. Illustrations in such Renaissance works such as Conrad

Gessner’s Historia animalium were flat and without depth or context, and not

separated from the text (Figure 4). The image in no way supplants the text, although

William West has argued that the concrete, demythologised image served as a

counterpoint to Gessner’s heterogeneous verbal descriptions.40 Sachiko Kusukawa

notes in her essay in this volume that Gessner claimed that his images were ‘ad

vivum’, but in fact many of them were not original to his book. This flat and non-

contextual style*and the re-use of images*continued in most works of natural

history throughout the seventeenth century. Although Matthaus Merian’s engravings

for Jon Jonston’s natural history of 1657 gave a little more context, the arrangement

on the page of the illustrations for Francis Willughby’s Ornithologia from 1676 could

have been made in the previous century (Figures 5 and 6). Similarly, the style of

37 [Claude Perrault], Les dix livres d’architecture de Vitruve, Corrigez et traduits nouvellement enFrancois, avec des notes et des figures (Paris, 1673), 12�3. On the trompe l’oeil technique, see Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, The Mastery of Nature. Aspects of Art, Science, and Humanism in the Renaissance(Princeton, 1991), ch. 1, pp. 11�48.

38 Brian W. Ogilvie, The Science of Describing (Chicago, 2006), 175; Nancy G. Siraisi, ‘Vesalius andHuman Diversity in De humani corporis fabrica’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 57 (1994),60�88, at 60 n.3.

39 The English edition (above n. 25) was a folio, but not an elephant folio.40 William West, Theatres and Encyclopedias in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge, 2002), 102�7.

393The king’s animals and the king’s books

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

cabinets in this era was based more on aesthetics than on nature, although it had its

own rules of similarity and dissimilarity.

Perrault and his collaborators in the Histoire des animaux borrowed from natural

history, comparative anatomy, and human anatomy in compiling the book, but they

also self-consciously aspired to make and display new knowledge of these new

Figure 3. Cameleon [Claude Perrault], Memoires pour servir a l’histoire naturelle des animaux(Paris, 1676). Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering & Technology.

394 A. Guerrini

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

animals. The image of the live animal often derived from sketches made while it still

lived in the menagerie, although it is likely that some of the images were from death

rather than from life.41 Perrault claimed a parallel precision between the text and the

image. The company carefully examined the whole animal and its dissected parts,

sometimes with the aid of a microscope. Then the person whom the company had

designated to write the description was charged with drawing the animal ‘sur le

champ’. This drawing did not serve as the basis for engraving until all those who had

been present at the dissection offered further confirmation. Although many members

of the Academy, including Perrault, were skilled draughtsmen, artistic skill was not

the first requirement, ‘because what was important was not to represent well what

one sees, but to see well what one wishes to represent’.42 Perrault minimised the

extent of the collaboration between the artist and the scientist to privilege the eye of

the natural philosopher above all others and privilege the Paris Academy above all

the other tenants at the rue Vivienne.

Nonetheless, the relationship between natural philosopher and artist was key to

this relationship between observation, epistemology, and picturing. While Perrault’s

preface elevated the status of the natural philosopher above the artist in order to

establish the position of the Paris Academy in the hierarchy of royal patronage of the

arts and sciences, his assertion appears to be more of an ideal than an account of

Figure 4. Lion, Conrad Gessner, Historia animalium (Zurich, 1551), Book 1. Linda HallLibrary of Science, Engineering & Technology.

41 Madeleine Pinault Sørensen, ‘Les animaux du roi: De Pieter Boel aux dessinateurs de l’AcademieRoyale des Sciences’, in L’animal au XVIIe siecle, edited by Charles Mazouer (Tubingen, 2003), 159�83.

42 Histoire des animaux (note 11), ‘Preface’: ‘parce que l’importance en ceci n’est pas tant de bienrepresenter ce que l’on voit, que de bien voir comme il faut ce que l’on veut representer’.

395The king’s animals and the king’s books

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

Figure 5. Wolf and hyenas, Joannes Jonstonus, Historiae naturalis de quadripedibus (Frankfurtam Main, 1650). Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering & Technology.

396 A. Guerrini

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

Figure 6. Tab. XXIV, Francis Willughby, Ornithologiae libri tres (London, 1676). Linda HallLibrary of Science, Engineering & Technology.

397The king’s animals and the king’s books

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

what actually took place. Manuscript evidence indicates lengthy and sustained

collaboration among artists, engravers, and naturalists, who occupied the same

building for many years. A number of artists regularly drew animals in the

menageries, and their observations, as well as those of the academicians, entered

into the illustrations. For example, Perrault noted differences between the published

image of the live coati mundi and his own observation of the animal on the dissection

table. The plain implication is that he never saw the animal alive, and that he

depended on the observation of the artist to depict the live animal.43

Even if the images were indeed drawn from life (or death), their iconographic

presentation at times drew upon older illustrations. In the case of the chameleon, the

pose closely resembles the image in Pierre Belon’s De aquatilibus of 1553, an image

subsequently used by Gessner (Figure 7).44 However, there are also important

differences between the two images, particularly the eye and mouth, and the later

image more closely resembles the actual animal.

In any case, the emphasis on direct observation, of the naturalist or of the artist,

extended only to the figures of the animals. The settings for the images of live animals

were largely imaginary. Unusually, this setting was a natural landscape, albeit a

landscape that bore little correspondence to the native habitat of these animals. The

1676 text identified the tortoise, for example, as originating in the East Indies, but its

image occupied a temperate rather than a tropical landscape, with a classical temple,

obelisk, and bridge (Figure 8). The Sardinian and Canadian deer are depicted

Figure 7. Chamaeleon, Pierre Belon, De aquatilibus (Paris, 1553). Linda Hall Library ofScience, Engineering & Technology.

43 Histoire des animaux (note 11), 88.44 William B. Ashworth jr., ‘Marcus Gheeraerts and the Aesopic Connection in Seventeenth-Century

Scientific Illustration’, Art Journal, 44 (1984), 132�8, at 133�7. Ashworth does not mention the Histoire desanimaux.

398 A. Guerrini

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

Figure 8. Grande Tortue des Indes, [Claude Perrault], Memoires pour servir a l’histoirenaturelle des animaux (Paris, 1676). Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering &Technology.

399The king’s animals and the king’s books

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

together as they would have lived in the Versailles menagerie, with the further

embellishment of a forest of what appear to be chestnut trees (Figure 9). Other

illustrations similarly show generic landscapes of the sort that were common

backgrounds in human anatomical illustration. There is also some correspondence

to the style of contemporary landscape painters such as Claude Lorrain and Nicolas

Poussin, who mingled classical architectural elements with natural landscapes.45 Not

all of the illustrations show ruins or tombs, commonly inserted in human anatomical

illustration as a memento mori, but some do, making, perhaps inadvertently, a

statement about parallels between human and animal souls, while following artistic

convention. Even if human figures are absent, the buildings in the background

reinforce the human presence in the image. These landscapes, then, do not

acknowledge habitat but ownership: although they are depicted outside the

enclosures of the menageries, these animals nonetheless reside in domesticated

landscapes for de-natured animals, human settings rather than animal settings.

The monkeys are depicted in the most humanised setting of all, the palace of

Versailles, where the geometrically perfect formal garden in the background and the

potted plant in the foreground portray a nature completely subsumed to human

desires (Figure 10). As with the deer, two different but similar species from opposite

sides of the world are pictured together: the ‘sapajou’ or capuchin monkey from

South America, and the ‘guenon’ or cercopithecus from Africa. The buildings are not

in the background but constitute the habitation for the animals. The anatomical

descriptions establish a close comparison between the monkeys and humans but

conclude in every instance that the differences between them are in fact profound.

The text details the morphological similarities between the monkeys and the human

form, with particular emphasis on the ‘hands’ (‘mains’ rather than ‘pattes’) and the

human-like larynx. Galen had argued that hands are uniquely human, ‘the

instruments most suitable for an intelligent animal’.46 Perrault’s caption points out

‘how the hands and feet of the monkey are different from the hands and feet of man’

and he explains in the text that the morphological similarities are superficial.

Descartes had famously argued in the Discourse on Method that speech distinguished

humans from beasts, and Perrault details the close anatomical similarities between

the organs of speech in humans and monkeys: ‘they are entirely similar to those of

Man, much more than the hand . . . according to the Philosophers monkeys ought to

speak, since they have the instruments necessary for speech’. But in this case

morphology is deceptive, because monkeys do not speak, affirming the status as

brutes that their hands demonstrated.47 Among all of the animals, they are the only

ones shown under restraint, with balls and chains.

In his text, Perrault displayed his awareness of the philological tradition while he

also situated the animals in their natural, exotic environments and acknowledged the

45 On the relationship between artistic genre and scientific illustration see James Elkins, ‘Art History andImages that are not Art’, Art Bulletin, 77 (1995), 553�71.

46 Galen, On the Usefulness of the Parts of the Body, trans. Margaret Tallmadge May, 2 vols (Ithaca, NY,1968), vol. 1, 69. Galen devotes the entire first book of this work to the hand.

47 Histoire des animaux (note 11), 120 : ‘La fig. d’en bas fait voir comment les Mains & les Pieds duSinge sont different des Pieds & des Mains de l’Homme’; 126 : ‘Les Muscles de l’Os Hyoıde, de la Langue,du Larynx, & du Pharynx, qui servent la plupart a articuler la parole, estoit entierement semblables a ceuxde l’Homme, & beaucoup plus de ceux de la Main . . . selon ces Philosophes les Singes devroient parler, puisqu’ils ont les instruments necessaires a la parole’. The ‘philosophes’ include Anaxagoras, Aristotle, andGalen; Perrault does not mention Descartes.

400 A. Guerrini

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

Figure 9. Cerf du Canada et Biche de Sardaigne, [Claude Perrault], Memoires pour servir al’histoire naturelle des animaux (Paris, 1676) Linda Hall Library of Science,Engineering & Technology.

401The king’s animals and the king’s books

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

importance of place as part of the animal’s identity. His narrative descriptions

followed humanist practice in including etymologies, classical references, and*despite his claims that he would not seek to classify*detailed attempts at

classification, at placing the animal he discussed into some more general category.

Figure 10. Sapajous et Guenon, [Claude Perrault], Memoires pour servir a l’histoire naturelledes animaux (Paris, 1676) Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering &Technology.

402 A. Guerrini

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

But unlike encyclopaedists such as Gessner who sought to gather all known

information about an animal, or earlier naturalists who sought out the anomalous,

Perrault aimed to sift through this information to find the single true fact.

Discovering the proper, original name for an animal, therefore, not only established

ownership (following the Renaissance tradition) but also established its identity as an

animal, its place among other animals.

The account of the ‘dromadaire’ spends the first page discussing the name

‘dromadaire’ and whether it applies to a camel with one hump or two. Pliny and

Aristotle said a ‘dromadaire’ had one hump, but common usage in his time, said

Perrault, referred to the two-humped variety as a dromadaire. ‘We call a dromedary

the animal which is here described’, the one-humped version, declared Perrault,

citing an Arab who was present at the dissection for corroboration.48 He placed the

hedgehog and the porcupine together, he said, because the ancients classified them

together, but then he proceeded to take apart any notion of similarity. On the other

hand, he placed the Sardinian and Canadian deer together because of their physical

similarities, despite the geographical separation.49 Yet when in the text he acknowl-

edged geographical specificity, he went beyond his customary humanist textual

references in seeking new empirical knowledge of places. In addition, this acknowl-

edgment of varied origins implicitly demonstrated the monarch’s power and the

extent of France’s colonial empire, which ranged from the ‘cerf du Canada’ to the

‘grande Tortue des Indes’ taken on the Coast of Coromandel.

6. ConclusionThe Histoire des animaux can be described as a boundary object par excellence,

displaying multiple meanings to multiple audiences.50 To the king and his minister

Colbert, the volumes, and particularly their illustrations, contributed to the royal

propaganda machine that conveyed prestige to the king and his office by means of

their size, expense, beauty, and symbolism. The Paris Academy gained prestige as the

recipient of royal favour but also as an intellectual body. The size and accuracy of the

images far surpassed those of any predecessors in natural history, natural philosophy,

or comparative anatomy. The volumes bridged the gap between comparative

anatomy and natural history, and between natural history and natural philosophy,

as no other works had done, and represented an unprecedented depth of

collaboration between naturalists and artists. The unusual format of the illustrations,

displaying both the entire live animal and its dissected parts, highlighted the process

of investigation which included dissections and experiments that explained specific

aspects of animal form and function.

Yet the impact of the Histoire des animaux was less significant than it might have

been. The expense and size of the volumes, as well as their status as patronage

objects, made them less well known to the broader community of natural

philosophers than less elaborate volumes. Far more copies existed of Alexander

48 Histoire des animaux (note 11), 29.49 Histoire des animaux (note 11), 112�3, 131.50 S.L. Star and J.R. Griesemer, ‘Institutional Ecology, ‘‘Translations’’, and Boundary Objects:

Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907�1939’, Social Studies ofScience, 19 (1989), 387�420; Roger Chartier, The Cultural Uses of Print in Early Modern France, trans.Lydia G. Cochrane (Princeton, 1987).

403The king’s animals and the king’s books

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4

Pitfeild’s English translation (reprinted in 1702) than of the 1670s originals. Not until

1733 did the volumes appear in a quarto French edition, and then mainly in response

to a pirated Dutch edition of 1731.51 By then, the impact of the books on natural

history and natural philosophy was muted, even though the editors, Jacques-BenigneWinslow and Antoine Petit, heavily edited the text and added several new

descriptions and illustrations from the store that remained among the papers of

Perrault, who died in 1688, and the anatomist Joseph-Guichard Duverney, who died

in 1730. These included additional examples of animals that had already been

included; so rather than the two lions of 1671 or the three of 1676, now seven lions

were described. Buffon’s Histoire naturelle, the first volume of which appeared only

16 years later, displayed obvious influences of the Histoire des animaux in its text, its

illustrations, and its scepticism about systems. The republication in 1733 made theHistoire des animaux at long last accessible, and therefore may have turned a work of

art into a work of natural philosophy.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Nico Bertoloni Meli and the other participants at the Indianaworkshop for their comments. Thanks also to my research assistant Tina Schweickert

and to Bruce Bradley and his staff at the Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering

& Technology for assistance with illustrations. My research for the larger project of

which this is part has been supported by a University of California President’s

Research Fellowship in the Humanities, a Franklin Grant from the American

Philosophical Society, and the Horning Endowment in the Humanities at Oregon

State University.

51 Memoires de l’Academie Royale des Sciences, depuis 1666 jusqu’a 1699. Tome III Premiere partie(Paris, 1733), ‘Avertissement des Libraires’, not paginated; Troisieme partie (Paris, 1734), ‘Avertissement’,(not paginated). The Dutch edition is : Memoires pour servir a l’histoire naturelle des animaux et des plantesper Messieurs de L’Academie Roiale des Sciences (La Haye, 1731), 2 vol. (of 5).

404 A. Guerrini

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ore

gon

Stat

e U

nive

rsity

] at

18:

35 2

4 A

ugus

t 201

4