THE INCIPIT PAGES OF THE MACREGOL GOSPELS

Transcript of THE INCIPIT PAGES OF THE MACREGOL GOSPELS

The incipit pages of the Macregol Gospels

CAROL A. FARR

The Macregol or Rushworth Gospels (Oxford, Bodleian Library, Auct. MS D. . )offers several windows onto the Insular world: its colophon, Old English interlineargloss, massive pages of expertly inscribed Gospel text, three surviving evangelist

portraits with symbols and four decorated incipit pages. Only the colophon and the glosshave been explored to any extent. In the colophon the painter and scribe left a record of hisname, Macregol, enabling his identification with the abbot of Birr who died in . By thelate tenth century, the manuscript had travelled to England, where at a place named asHarewood two more scribes, Owun and Farman, added the gloss. While the colophongrants the Macregol Gospels membership in the exclusive club of Insular manuscripts ofdocumented date and origin, and its gloss places it next to the Lindisfarne Gospels in thestudy of Old English, no extended art historical studies of its decoration have appeared inprint. With present trimmed dimensions of x mm (text-block x mm), it hasdecoration and solid blocks of text which magnify its massiveness, but its decoration doesnot possess the finesse and variety seen in its much-studied possible contemporary, the Bookof Kells. Macregol is as individualistic as Kells in its decoration, but in a different way andperhaps for different purposes. Like the Book of Kells, it uses features of contemporarybook art alongside older forms, but it also presents Classicizing elements which have goneunnoticed. Macregol’s decorated full-page incipits are even less studied than his evangelistportrait pages, yet they too show Macregol’s awareness of contemporary as well as pastmanuscript art and his ability to incorporate antique visual language into his interpretationof Insular forms. The way in which he did this suggests he was using them to connecthimself and his Gospels with political concerns in which his monastery was enmeshed. Anattempt to understand the decoration of its incipit pages within the context of the earlyninth century as well as the specific context of Birr in Macregol’s time may help to informus further about the abilities of Insular artists to use and interpret styles and iconographyas well as to understand the Macregol Gospels.

Despite its massive dimensions, Macregol’s Gospel book shares with most of the Irishpocket Gospels a lack of prefaces and chapter lists, as well as an Irish mixed Vulgate text.McGurk has shown that avoidance of prefatory accessories is one of the archaic features ofpocket Gospels and some larger Gospel books from ‘celtic’ lands. Nonetheless, as McGurk

Fo. v: ‘Macregol dipinxit hoc Evangelium. Quicumque legerit et intellegerit istam narrationem orat pro macreguilscriptori.’; C. O’Conor, Rerum hibernicarum scriptores veteres (Buckingham, ), pp ccxxix–ccxxxvii, first identifiedMacregol as the scribe, bishop, and abbot of Birr recorded in AU : ‘Mac Riaguil nepos Magleni, scriba et episcopus,abbas Biror, periit’; AU, i, p. . A.N. Doane, in P. Pulsiano (ed.), Anglo-Saxon manuscripts in microfiche facsimile, iii:Gospels. (Binghamton, NY, ), pp –; O. Pächt and J.J.G. Alexander, Illuminated manuscripts in the Bodleian Library,Oxford (Oxford, ), iii, p. , no. . J.J.G. Alexander, Insular manuscripts th to th century (London, ), no., pp –; E.A. Lowe, Codices latini antiquiores (nd ed. Oxford, ), ii, no. , p. . TCD, MS . M.P.Brown, The Book of Cerne: prayer, patronage and power in ninth-century England (London, ), p. . P. McGurk, ‘TheIrish pocket Gospel book’, Sacris Erudiri, : (), – at –; idem, ‘The Gospel book in Celtic lands before AD: contents and arrangement’ in P. Ní Chatháin and M. Richter (eds), Ireland and Christendom: the Bible and the missions

and others have demonstrated, Insular and especially Irish scribes never slavishly followedwhat had been done before, and Macregol was no exception. He apparently was aware thatGospel books, large or small, could include accessories to suit the needs of those usingthem, just as, for instance, the scribes who created the Book of Mulling, a pocket Gospels,included some prefatory accessories.

Evangelist portraits from the Book of Mulling and some other pocket Gospels providecomparisons to show how Macregol adapted contemporary book art styles. In the pocketGospels, the blank backgrounds usually seen in earlier evangelist portraits become filledwith panels of ornament set within broad, densely ornamented borders, taking on theappearance of carpet-pages, a feature seen also in the Macregol evangelists. Macregolextended the carpet-page treatment to his incipits, creating visually impressive diptychs ofevangelist portrait and initial pages.

He and other painters of his time were aware of the possibilities offered by facingdecorated pages and text. The artists of the Book of Kells created visual references betweenfigures or decoration and the decoration or text presented on the folio opposite. Moreover,pairing visually harmonious, richly decorated pages to heighten the impact of the openingwas one of the developments of early Carolingian manuscript decoration, initiated in theframed pages of the Godescalc Evangelistary. All its pages have decorated frames, but itbegins with a series of six full-page miniatures which harmonize visually, in part because ofthe designs of their borders, which echo each other in the proportions of their panels as wellas scale and rhythm of decoration and colouring. In the book’s colophon, the scribeGodescalc recorded that it was made to celebrate Pope Hadrian’s baptism in ofCharlemagne’s son, Carloman, at the Lateran. Godescalc’s unusual verse colophon impliedthat, appropriate to its imperial context, the book consciously raised the level of opulencein book decoration, using purple-painted parchment, gold writing and decorated framesfor every page – the latter previously used only for dedication and title pages. TheGodescalc Evangelistary’s framed, opulent pages represent the form-maker in a long line ofsubsequent imperial or very high status books.

While the Macregol Gospels does not have purple pages or gold decoration, itparticipates in the contemporary phenomenon of impressive books with decorated framedpages. Moreover, its colophon page follows a pair of heavily framed pages at the end ofJohn’s Gospel, and it in turn has an extraordinary frame, dividing the page into six panelsinto the upper four of which Macregol inscribed Iuvencus’s verses on the evangelists. Heidentified himself and wrote his plea for prayers only in the lowermost pair. Nees likens thepage to Insular four symbols pages but, pointing out the exceptional nature of the decoratedframe, observes that the page takes on the appearance of a cross on a base, comparing itwith Carolingian pictures of processional crosses with kneeling donors. Macregol, then,presents himself as a supplicant before the cross surrounded by the evangelists. Suchimages of the cross and evangelist symbols have apocalyptic significance and are also

Carol A. Farr

(Stuttgart, ), pp –, at pp –. See Alexander, Insular manuscripts, nos. –, , pp –, and illus.–, –, , for St Gall, Stiftsbibl., cod. ; TCD, MS , Book of Mulling; BL, Additional MS ; Dublin, RIA,D. II. , Stowe St John; London, Lambeth Palace Library, MS , Macdurnan Gospels. Blank backgrounds in the Bookof Dimma (TCD, MS ), Koehler suggested, copy earlier portraits (ibid., p. ). Paris, Bibliothèque nationale deFrance, nouv. acq. lat. . L. Nees, ‘Imperial networks’, in Leuven, Stedelijk Museum Vander Kelen-Mertens,Medieval mastery: book illumination from Charlemagne to Charles the Bold / – (Turnhout and Leuven, ), pp– at pp –. L. Nees, ‘The colophon drawing in the Book of Mulling: a supposed Irish monastery plan and thetradition of terminal illustration in early medieval manuscripts’, Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies, (), – at –.

connected with the apertio aurium ceremony of medieval baptismal liturgy. While theGospels with their framed verse colophon may have been made on the model of theGodescalc Evangelistary to celebrate a royal baptism, Macregol more likely called upon therich semiosis – visual and verbal – of the cross with evangelist symbols to reinforce thepower of his inscription and, overall, the Gospel book.

The incipit pages of the Macregol Gospels

Brown, Book of Cerne, pp –; É. Ó Carragáin, ‘A liturgical interpretation of the Bewcastle Cross’ in M. Stokes andT.C. Burton (eds), Medieval literature and antiquities: studies in honour of Basil Cottle (Cambridge, ), pp –, at pp–.

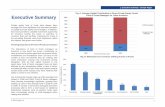

Incipit, Gospel ofMatthew, MacregolGospels, c.–,Oxford, BodleianLibrary MS Auct.D. . , fo. r(photo: BodleianLibrary, Universityof Oxford).

In other ways, Macregol appears to ignore some of the devices used in contemporarybook art to achieve effects of magnificence. For example, the calligraphic form of Tiberiusstyle display scripts, as seen in some of the incipit pages of the Barberini and St PetersburgGospels, do not appear in the initials of the Macregol Gospels. He might have beenaware of them, since calligraphic initials appear in the Book of Armagh, and a generalmutual awareness between Anglo-Saxon Tiberius style and Irish book art has been observedin several manuscripts. Macregol retained the geometric display capitals seen in the full-page incipits of the Lindisfarne Gospels. Moreover, the designs of his initials appear to bebased on the tradition which Eadfrith put into its most refined form a century earlier.

Each of Macregol’s monogram initials resembles its correspondent in the LindisfarneGospels in general shape and some details of decoration. For example, the monograms ofthe first three letters of Matthew’s Gospel (fig. ) form similar shapes with the lower strokeof the L forming a cross with the intersection of the I. The upper ends of the downstrokesof the L have pairs of facing spirals with symmetrical panels of ornament topped withsmaller spirals, and the lower end terminates in a spiral within the bow of the b. The generallayouts of panels of ornament resemble each other, despite vast differences in elegance.There are other similarities: the rubrics are in the same position within the upper rightcorner of the ornamented frames, and the frames’ upper terminals have a small animal head.

Similarities can also be seen in the incipits for the Gospel of John (fig. ). The overallshapes of the monograms resemble each other in comprising the first three letters of theincipit, written with diminuendo. Letter-forms of N and P are the same, N with angledcross-stroke and P with double bow. Furthermore, the remaining letters of principio form aunit set in a rectangular panel the height of the N and P and articulated into smaller panelsto hold the letters. Finally, the ornament at the top of the monograms’ vertical elements fansout symmetrically. The two initials’ similarities suggest a common source for both, withMacregol’s a later development. Lindisfarne’s partial border of bars and monogram edgebecomes in Macregol a substantial frame with heavy square corners, and Lindisfarne’sdotted infills of the panels holding the display capitals undergo an intensification inMacregol to become solid colours, with interlinear panels to create the carpet-page effect.The two appear quite close in design relative to other eighth- and ninth-century decoratedincipits. Macregol also used Greek letters in his incipit pages – here π for the second P ofprincipio – one of the international features of the Lindisfarne Gospels.

A second eighth-century Gospel manuscript, the Lichfield Gospels, in some wayspresents an intermediate example. The Lichfield Gospels like the Macregol Gospels and theIrish pocket Gospels has no chapter lists or prefaces, and it has a framed page of text. Itsincipit pages also have geometric display capitals arranged in bordered registers across thepage within a border on three sides, creating an effect similar to – although slighter than– that seen in Macregol. Zoomorphic ornament is incorporated into the terminal of theborder and between the panels of display capitals, a feature amplified in Macregol’s designs

Carol A. Farr

Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica, Barberini MS Lat. . St Petersburg, Public Library, cod. F. v. I. . SeeAlexander, Insular manuscripts, illus. , –, , –. TCD, MS. M.P. Brown, ‘Echoes: the Book of Kellsand southern English manuscript production’ in F. O’Mahony (ed.), The Book of Kells: proceedings of a conference at TrinityCollege Dublin – September (Dublin, ), pp –. BL, Cotton MS Nero D.iv. See M.P. Brown, TheLindisfarne Gospels: society, spirituality and the scribe (London, ), Pl. . Ibid., Pl. . See Alexander, Insularmanuscripts, illus. (Schloss-Harburg), (Barberini), (St Petersburg), (Hereford). Brown, LindisfarneGospels, pp , . Lichfield, Cathedral Library, s.n. McGurk, ‘Irish Pocket Gospel Book’, pp , ; G.Henderson, From Durrow to Kells: the Insular Gospel books, – (London, ), p. .

with panels of zoomorphic interlace. Moreover, Lichfield’s best preserved incipit initial –Luke – has clear plain borders around panels of ornament, as does Macregol’s Lucaninitial. Finally, the similarities with eighth-century Gospel books having strongNorthumbrian connections seem all the more interesting in view of Macregol’s use of thescript associated with earlier deluxe Gospels.

The incipit pages of the Macregol Gospels

See Brown, Lindisfarne Gospels, Pl. . T.J. Brown, ‘The Irish element in the Insular system of scripts to circa A.D.’ in H. Loewe (ed.), Iren und Europa im früheren Mittelalter, vols (Stuttgart, ), i, pp –; W. O’Sullivan,‘Manuscripts and palaeography’ in D. Ó Cróinín (ed.), New History of Ireland, i: Prehistoric and early Ireland (Oxford, ),–, at p. .

Incipit, Gospel ofJohn, Macregol Gospels,fo. r (photo:Bodleian Library,University of Oxford).

Macregol’s incipits have some general similarities with those of the Book of Kells. Kellstransforms its incipit pages with dense carpet-like ornament in panels, sometimes nearlyconcealing the display capitals. Nevertheless, the Matthean incipit in the Book of Kells (fo.r) has a verbal background in Insular exegeses of the descent of Christ (Matthew :–)which define these verses as the primary Gospel and a book in itself which retells Genesis,the Liber generationis, the words of its incipit. Hiberno-Latin writers interpret Matthew’sdescent of Christ, the new Adam, as an encapsulation of the story of ‘re-creation andbeginning of incorruptibility’, Liber meaning simultaneously a ‘book’, ‘freeing’ (of souls)and ‘offspring’ (Christ’s divine and human descent or ‘sonship’). In Kells the words Libergenerationis are set into nested, heavily ornamented borders and introduced by a humanfigure who holds out a book, spotlighting the multivalent first word. Opposite him on thepage layers of borders define an oblong panel bearing the word generationis in purple andred display capitals, suggesting a framed page in a book, by itself a visual pun of the firsttwo words. Above, figures of an angel and a man, who holds a book, tablet or box, emergefrom the swirls of ornament, and the figure of Matthew / Christ in the facing portrait (fo.v) holds a book bound in the same colours. Macregol’s incipit page, in contrast, doesnot isolate and emphasize the word liber nor does it present images of books. Its plain,block-text layout of the genealogy on fo. r bears no comparison at all with that in Kells(fos. v–v) where the ancestral names in columns were to be set within decoratedcruciform borders. Nevertheless the general similarity of the Lib monograms seen withLindisfarne’s continues with that in Kells. The letters of the monogram interlaceillusionistically, the lower end of the L with the b (Macregol) or the E and R (Kells).Macregol isolates the last three syllables of generationis in a small green frame on the outeredge of the border, keeping them on the same line with Liber. This has been taken asevidence of Macregol’s incompetence, but, considering the treatment of this word in theBook of Kells, one might see instead his intention to highlight the phrase which hadbecome important in the interpretation of the Gospel of Matthew in Insular Christianity.

Finally human heads, busts or figures appear in the incipit pages of both manuscripts.Incorporation of human figures into initial ornament is a well-known Insular developmentof the eighth-century, during which Anglo-Saxon artists invented the historiated initial andthe human figure becomes ever more prominent in Irish manuscripts. Among manuscriptsassociated with Ireland, the Book of Kells presents the most sophisticated examples, butthese represent a general trend of using human figures in carpet pages and full-page picturesin Irish deluxe manuscripts.

The figures in the Macregol incipit pages, however, mostly differ from those in the otherIrish examples. Instead of being frontal, clothed full- or half-length figures like the ones inthe Kells Matthean incipit they seem less integrated into the ornament, inhabiting theframe or appending to its outer edge. The closest comparisons are the interlaced humanfigures in panels of the frame of Macregol’s Marcan incipit page (fig. ) with the group ofeight small interlaced figures in the panel at the top of the Lucan page in Kells and the twosmall figures placed sideways at the top of this panel with the pair of figures tucked into thelower right corner of the frame of the Johannine incipit in Macregol. A few other humanfaces in the Book of Kells are reminiscent of those in Macregol, especially the profile head

Carol A. Farr

J. O’Reilly, ‘Gospel harmony and the names of Christ: Insular images of a patristic theme’ in J.L. Sharpe and K. vanKampen (eds), The Bible as book: the manuscript tradition (London, ), pp –, at pp –. Ibid., p. . Ibid., pp –. S. Hemphill, ‘The Gospels of MacRegol of Birr: a study in celtic illumination’, PRIA, C (),– at . See Henderson, Durrow to Kells, pp –, –.

with upraised arm which emerges from the end of the border of fo. . Its facial features,upraised arm and interlaced hair compare with those of the profile at the top of Macregol’sincipit of John. Otherwise, the Macregol figures appear unrelated to Irish examples.

The differences may be explained by looking to the increasing classicism in late eighth-and ninth-century Insular art, seen especially in the Anglo-Saxon Tiberius-group manu-scripts. Human faces appear in the incipit decoration of the Barberini Gospels, althoughtheir execution and classicizing integration into the overall design is much moreaccomplished than in the Macregol Gospels. Nevertheless, it is in the faces and figuresappended to the borders of the incipit pages that Macregol’s version of Classical decorationand iconography are to be seen.

The incipit pages of the Macregol Gospels

Incipit, Gospel ofMark, MacregolGospels, fo. r (photo:Bodleian Library,University of Oxford).

The mask and human figure are generally associated with Classical ornament, especiallywhen they are more naturalistic than abstracted, and those in the incipit pages of theMacregol Gospels can be seen to be closer to Carolingian and Late Antique examples thanto most earlier Irish ones. The frontal head with upraised arms at the top of the Mattheanincipit (fig. ) could be compared with a capital from St Benedict, Mals (Malles), made inthe early ninth century under Carolingian influences, which features a Classical personi-fication of earth or Atlas. The sources of such figures and other cosmic personifications arewell-known in post-Augustan Roman art. Several examples are carved on the late second-century Velletri sarcophagus, depicting the Labours of Hercules, a myth involving the hero’stravel to the corners of the earth and the underworld. In the lowest register, atlantes – orperhaps Hercules standing in for Atlas – hold up the lintel which takes the place of the sky.Within alternating pediments and tympana in the top register, a series of cosmographicpersonifications signify the heavenly realms. A nereid or Nyx – the night – evokes the skyby means of the conventional billowing scarf. She is flanked by horn-blowing sea centaurswho personify the winds. In the Macregol Gospels, the drawing technique of the bustseems incongruous with that of the ornament, and stylistically it is difficult to place insurviving contemporary Irish art. It is much more like some continental examples,especially a wall-painting dating about from S. Vincenzo al Voltorno. It has a similarlinear quality and simplified outlines of facial features, lacking the forward staring eyes of

Carol A. Farr

C. Stiegemann and M. Wemhoff (eds), Kunst und Kultur der Karolingerzeit: Karl der Grosse und Papst Leo III(Exhibition catalogue, Paderborn, Erzbistums Paderborn and Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe, ) (Mainz, ),ii, pp – (Catalogue VIII.b), illus. p. . The capital and another are now in Bozen, Museo Civico, Inv. Nos. D

and . See L. Nees, Early Medieval art (Oxford, ), pp –. See J. Mitchell in : Kunst und Kultur, i, pp– (Catalogue II.), illus. p. . The fragmentary wall painting (Campobasso, Soprintendenza Archeologica del Molise,Inv. No. ) from the northwest corner of the vestibule depicts a young saint.

Detail of ‘Atlas’ andconfronted heads, fo. r,

Macregol Gospels(photo: Bodleian

Library, University ofOxford).

most Insular depictions of faces. Its nose is drawn frontally, not in profile, as noses of thefigures in the Kells Matthean incipit and many other Insular examples, and lacks thecomplicated geometric abstraction seen in other faces depicted in Kells and a number ofInsular manuscripts.

The confronted heads to the right of the Atlas figure in Macregol’s Matthean incipit pagealso seem to have sources in Late Antique art. They resemble profiles of Peter and Paul inEarly Christian gold-painted glass, but they are closer to the confronted heads on coinsderiving from Late Antique types, along with Early Medieval examples from Celtic, Anglo-Saxon and continental Germanic contexts. They have been interpreted as symbolic of acooperative political relationship between church and state, personified in king and bishop,or, as Gannon suggests for Northumbrian examples, a sign of unity of two equally royal co-rulers. She points out the motif ’s appearance in devotional art, as in the gold-leaf cross fromUlm-Ermingen, mid-seventh century to first quarter eighth century, and further exampleson a brooch from Berghausen and gold bracteate from Odense.

Macregol also put human heads and figures around the border of the incipit of John. Onthe upper border, a profile, half-length figure blows a pipe, while to the right a frontal faceappears to be holding its hair with both hands uplifted, the ‘hair’ then becomes interlace(fig. ). Within the lower right corner, two cocoon-like ‘figures’, with profile heads and longbeards, are tightly enclosed in panels (fig. ). Hilary Richardson, basing her interpretationon Eriugena’s ‘Homily on the prologue to the Gospel of St John’, sees the profile at the topleft as a pipe-player and the frontal bust as female, hands behind her ears, ‘in a listeningattitude’, so that they represent the Evangelist John and the Church, according to thehomily’s opening, ‘The voice of the mystic Eagle resounds in the ears of the Church.’

While exegetical texts could have influenced the depiction of the heads, the homily doesnot account for, among other things, the other two figures at the lower right corner. It is

The incipit pages of the Macregol Gospels

A. Gannon, The iconography of early Anglo-Saxon coinage sixth to eighth centuries (Oxford, ), pp –. H.Richardson, ‘Number and symbol in early Christian Irish art’, JRSAI, (), – at –.

Detail of ‘Wind’ and‘Heavens’, fo. r,Macregol Gospels(photo: Bodleian Library,University of Oxford).

possible, however, that the heads and figuresof the incipit of John represent, like thoseof the Matthean incipit, classicizing person-ifications. The profile at the left resemblesthe personification of a wind, as seenalready in the Velletri sarcophagus and alsoin Late Antique and Early Medieval cos-mological diagrams of the four winds.

The face at the top right imitates a con-ventional Classical personification, againalready seen on the Velletri sarcophagus, ofthe sky, wind or air, who holds a billowingcloak over her head. It appears as well inthe centre of the mid-fourth-century,sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, where itsignifies the heavens upon which Christ isenthroned. Moreover, the figures at thelower right could fit into this cosmologicalprogramme. Their position at lower cornerand their enclosure within a panel suggestspersonifications of the earth, as seen innumerous Roman works, including the latefourth-century Missorium of Theodosius I(AD ). The earth personification beneath

the emperor’s feet signifies his rule over the earth, as ‘Sky’ on the sarcophagus signifiedChrist’s rule over the heavens and earth.

Macregol’s reasons for placing these cosmological images borrowed from Classical art atthe edges of his incipit designs should be understood within the context of the manuscriptas a whole. On one level, the classicism of the figures could have been meant to elevate thedecoration of the book by referring to motifs seen in the art of the contemporary Imperialmodel, Charlemagne’s empire. Macregol was clearly intent on producing an impressiveGospel book in other ways as well, by its size, the intense colour of its decorated pages andtheir lavish design. Even its undecorated pages are impressive in their conspicuously largeblocks of text liberally sprinkled with colour infills. Representations of cosmic personifi-cations are known from mid-ninth-century Carolingian manuscript art, in the VivianBible, made at least twenty-three years after the Macregol Gospels. No earlier use ofpersonifications comparable with the heads and figures in Macregol’s Gospel incipits isknown in Carolingian manuscripts. Macregol was probably using cosmic personificationsas he knew them from sources other than Carolingian ones, although he may have beeninfluenced as well by Carolingian classicizing visual art. Classical personifications and theassociations of certain Classical gods with natural elements, such as Amphitrite, Tethys,Aeolus, Phoebus and Hecate, played a role in Irish learning as early as the seventh century.

Carol A. Farr

For example, in a Visigothic prayerbook, c. (Verona Cathedral, Biblioteca Capit. cod. LXXXIX, fo. r), illustrated inJ. Williams, Early Spanish manuscript illumination (New York, ), p. . See Nees, Early Medieval art, pp –. Also called First Bible of Charles the Bald, Paris, BnF, lat. , fos. r, r; see R. Calkins, Illuminated books of the MiddleAges (Ithaca, NY, ), Pls. , .

Detail of ‘Earth’ figures,fo. r, Macregol Gospels(photo: Bodleian Library,

University of Oxford).

Poets of the Hesperica Famina used Classical mythological language to describe naturalfeatures of the heavens and the earth, and the Yellow Book of Lecan’s earliest layers of texts,dating –, refer several times to the names of Classical personifications or othermythological names associated with natural elements. Other works, such as Altus Prosator,refer to inhabitants under the earth. While no visual examples survive from seventh- oreighth-century Insular art, Harbison has recently pointed out the cosmic personifications– Gaia and Tellus, along with Sol and Luna – around the Crucifixion on the early-tenth-century Cross of Muiredach, Monasterboice, as well as Blathmac’s vision of the personifiedelements mourning the death of Christ in his poem on the Crucifixion, c..

The designs of the incipit pages probably resulted from a complex incorporation ofimagery known and significant to Macregol and the community at Birr. For example, theincipit of Mark has panels of human interlace, made up of four figures, on two sides of itsborder, which do not appear to be based on Classical personifications. They could becompared with the human interlace in the rhombus at the centre of the chi of the Mattheannomen sacrum in the Book of Kells. Werckmeister, Lewis, and O’Reilly have discussedexegetical writings on the tetragonus mundus as a sign of the cosmos within the monogramto express the earthly incarnation of Christ. The human figures cue its significance byevocation of the body, to sow within it a further sign of the Incarnation. The bodies onMacregol’s Marcan incipit serve a related significance. The four-sided page of the Gospelbook, emphasized by its heavy border and carpet-like decoration, becomes itself a sign ofthe Word within the world or tetragonus mundus, although in a less complex way than seenin the Book of Kells. Use of the figures in the incipit pages has to be seen within the broadercontext of developments of late eighth-century Insular Gospel book decoration, whichincluded incorporation of visual symbols of the Incarnation into the monogram of Christin the Book of Kells. Macregol created his incipit pages during a time in which a freer useand invention of visual forms was possible, perhaps with relationships to exegetical andother literature on the scriptures, while drawing upon the centuries of book-makingtradition in Ireland and native and earlier Christian use of abstract designs in visual art. Inthe late eighth century an intensification of relationship of visual images and textualmeaning seems to have been developing in Insular art, granting artists more possibilities toimbue human figure and face with significance arising from influences and interchangeswith Continental art, giving rise to Anglo-Saxon classicism of the Tiberius style and perhapsalso some uses of the figure in Irish manuscripts.

In a further sense, the faces and half-figures in the four-sided densely ornamented shapeof the text as Incarnate Word create a visual reminder of the place of the earth and thephysical in Christian belief, which is explained and expressed in patristic writings referringto the body and also in distinctive ways in Hiberno-Latin and Old Irish exegesis and

The incipit pages of the Macregol Gospels

M.W. Herren, ‘Literary and glossorial evidence for the study of classical mythology in Ireland AD –’ in H.Conrad O’Briain, A.M. D’Arcy and J. Scattergood (eds), Text and gloss: studies in Insular learning and literature presented toJoseph Donovan Pheifer (Dublin, ), –, at pp –, –. M. Smyth, ‘The physical world in seventh-centuryHiberno-Latin texts’, Peritia, (), – at . P. Harbison, The high crosses of Ireland: an iconographic andphotographic survey (Bonn, ), i, pp –, –; ii, figs. –; iii. figs. –. The three human heads and figure withhorn at the corners of the Second Coming page, Turin, Bibl. Nazionale, cod. O. IV. , fo. a, may be early ninth-centuryexamples. O.K. Werckmeister, Irisch-northumbrische Buchmalerei des . Jahrhunderts und monastische Spiritualität(Berlin, ), pp –; S. Lewis, ‘Sacred calligraphy: the chi rho page in the Book of Kells’, Traditio, (), –,at –; J. O’Reilly, ‘Patristic and insular traditions of the evangelists: exegesis and iconography’ in A.M. Luiselli Faddaand É. Ó Carragáin (eds), Le isole britanniche e Roma in età romanobarbarica (Rome, ), pp –, at pp –.

devotional writings. Despite sometimes viewing the body as a source of temptation, as inthe prayer ‘Patrick’s breastplate’, it was also seen in a positive sense. In Christianity thebody’s importance is implicit in the Incarnation and Resurrection. Paul and Augustine usedthe figure of the body as the Church and its history on earth and in heaven. In some of hiswritings Augustine speaks of how the soul operates through the body and uses it to makesense of the world of signs. Through the body the soul can sense the order and beauty ofthe world and from this realize the existence of the creator. The soul may obtain wisdomthrough ordering the body’s sense perceptions.

For the Irish Augustine in his De Mirabilibus sacrae scripturae, the body is instrumentalin salvation. On the Incarnation he says that ‘God put on human flesh, not the nature ofangels,’ and ‘granted forgiveness to man’, and on the baptism of Christ, ‘the person of theSon clothed in a body of human flesh’, when the Holy Spirit appropriately descended ‘inbodily form’. Some striking cosmological images of the body are proclaimed in ‘The EverNew Tongue’, a homily on Genesis : – a lection for the Vigil of Easter Sunday – originallywritten as early as the eighth century.

The creation of the world which has been accomplished by Christ’s resurrection fromthe dead on this eve of Easter. For every material and every element and every naturewhich is seen in the world, there were all brought together in the body in whichChrist rose again, that is, in the body of every human.

‘The Evernew Tongue’ then goes on to explain how the world is the body. From wind andair proceed the ‘respiration of breath in people’s bodies’, the sun and stars of heaven make‘the brightness and light in people’s eyes’, the stones and clay of earth make ‘the minglingof flesh and bones in people’, and ‘the material from the flowers and bright colours of theearth […] makes the freckling and pallor of faces, and the colour in cheeks.’ This unity ofworld and body inheres in salvation and resurrection:

With him the whole world rose again; for the nature of all creation was in the bodywhich Jesus had put on. For if the Lord had not contrived [that], and if he had notsuffered for the sake of the race of Adam, and if he had not risen again after death, thewhole world would be destroyed together with the race of Adam at the coming of theJudgment, and no creature of sea or land would be redeemed, but the heavens wouldburn up […]

Macregol might have had in mind this sort of interpretation when he put small busts andfigures of cosmic personifications into the borders of his designs for the Matthean andJohannine incipits, the two which express most forcefully the Incarnation. Moreover, havingdesigned incipit pages which could signify the world as Creation, Incarnation, Resurrectionand Last Judgment, Macregol also created a framed page on which he quoted Juvencus’sinterpretation of the four animals – symbols of the evangelists – arranged in a recognizablecosmological design and on which he asked for the prayers of ‘those who read [it] and

Carol A. Farr

M.R. Miles, Augustine on the body (Missoula, MT, ), pp –; D.B. Martin, The Corinthian body (New Haven, ). Augustinus Hibernicus, De mirabilibus sacrae scripturae, PL , –, at , ; ‘On the miracles of holy scripture’in J. Carey (ed. and trans.), King of mysteries: early Irish religious writings (Dublin, ), pp –, at , . ‘In TengaBithnua’ in Carey (ed. and trans), King of mysteries, pp –, ; see also J. Carney, ‘Language and literature to ’, NewHistory of Ireland, i, p. . Carey (trans.), King of mysteries, p. . Ibid. Ibid.

understand’. With such transformation of the pages of his Gospel book into signs of theworld and the Incarnation within it, Macregol perhaps was making a statement about hisplace – and his monastery’s place – within that world.

Birr lies just within the Munster border with Leinster, the border of Connacht (Galway),the Shannon, not far to the west. Its borderland status is often mentioned, usually as thesite of the promulgation of the Law of Adomnán in and one of monastic wars of thesecond half of the eighth century when Clonmacnoise attacked it (). Macregol wasabbot of Birr in the first decades of the ninth century, during a period when thesecularization of monasteries was bringing on ecclesiastical wars and, with the accession ofthe ecclesiastic Feidlimid mac Crimthainn to the kingship of Cashel and Munster in ,royal attacks on monasteries. Probably for most of Macregol’s years as abbot, Artrí macCathail was king of Munster (ordained , died ) before abdicating sometime before, when Feidlimid took the kingship. Neighbouring Connacht had been enjoying aperiod of unified kingship since the s, and this continued until . From , thekingship of Tara had been in the powerful grip of the Cenel nÉogain high-king, ÁedOirdnide or Áed mac Néill, until his death in . Secular and ecclesiastic warfare were on-going, while harmony was being achieved on some fronts with the promulgations of laws,the establishment of Kells in Meath and Armagh’s attainment of primacy. Macregol livedin a complex world, with ever-increasing development of international power networks, asCharlemagne’s kingdoms, the Mercian kingdom in Anglo-Saxon England and a pope,Leo III (–) who was willing to intervene in a dispute between the Mercian king,Cenwulf, and Archbishop Wulfred as well as aid Charlemagne’s authority as Christianemperor. We do not know very much about Macregol: he was a painter and scribe, nepos(descendant) Magleni, bishop and abbot of Birr, who died in , but he made his greatGospel book during a period of escalating power-plays, violence and attempts to imposeorder. In this context, he drew Classical personifications into initial pages resembling thosemade a century earlier in the Lindisfarne Gospels while synthesizing into them as well thedense ornament of contemporary books, creating huge pages with striking visual impact.Perhaps he was thus asserting his monastery’s authority and historical position as a meetingplace of secular and royal powers, and placing it within the context of the Church’sauthority under Rome. This could be why he painted at centre top of the first initial pagea pair of confronted heads, which can evoke the Church possibly as Peter and Paul and atthe same time remind of the monastery’s role as mediator between secular and ecclesiasticalpowers. In artistic brilliance, Macregol could not equal the painter who decorated theLindisfarne Gospels, but perhaps like Eadfrith and Adomnán he was trying to assert thework of God to a world in need of bridge-builders.

The incipit pages of the Macregol Gospels

‘The ancient boundaries and tribes of Meath’ in P. Walsh, Irish leaders and learning through the ages (Dublin, ), pp–; M. Ní Dhonnchadha, ‘Birr and the Law of the Innocents’ in T. O’Loughlin (ed.), Adomnán at Birr, AD : essays incommemoration of the Law of the Innocents (Dublin, ), pp –, at pp –; F.J. Byrne, Irish kings and high-kings (London,), pp , , –; T.M. Charles-Edwards, ‘Early Irish law’, New History of Ireland, i, –, at – idem, EarlyChristian Ireland (Cambridge, ), pp , , ; P. Ó Riain, ‘Pagan example and Christian practice: a reconsideration’in D. Edel (ed.), Cultural identity and cultural integration: Ireland and Europe in the early Middle Ages (Dublin, ), pp –,at pp –. Byrne, Irish kings, pp –; Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, pp , –, –, –, –;M. Herbert, Iona, Kells and Derry: the history and hagiography of the monastic familia of Columba (Oxford, ; repr. Dublin,), pp –; M.J. Enright, Iona, Tara and Soissons: the origin of the royal anointing ritual (Berlin, ), p. . N. Brooks,The early history of the Church at Canterbury (London, ), pp –, –, , . D. Ó Corráin, ‘Ireland c.: aspectsof society,’ New History of Ireland, i, –, at –, also mentions settlement of aristocratic branches of the Uí Raibne at themonastery, Birr. Brown, Lindisfarne Gospels, pp –; Herbert, Iona, pp –.