The Five Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire in Norway

Transcript of The Five Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire in Norway

Personality and Social Psychology

The Five Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire in Norway

INGRID DUNDAS,1 JON VØLLESTAD,2 PER-EINAR BINDER1 and BØRGE SIVERTSEN1,3

1Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway2Solli District Psychiatric Centre, Nesttun, Norway3Division of Mental Health, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Bergen, Norway

Dundas, I., Vøllestad, J., Binder, P.-E. & Sivertsen, B. (2013). The Five Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire in Norway. Scandinavian Journal ofPsychology 54, 250–260.

The aim of this study was to adapt the Five Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) for use in Norway. Three studies involving three different sam-ples of university students (mean age 22 years, total N = 792) were conducted. Confirmatory factor analyses showed that a five factor structure pro-vided an acceptable fit to the data. All five factors loaded significantly on the overall mindfulness factor. As expected, correlations between the FFMQtotal scores and subscales were positive and significant, ranging from 0.45 to 0.65. Correlations between FFMQ total/subscales and Mindful AttentionAwareness Scale (MAAS) were significant and negative (since low scores on the MAAS indicate high mindfulness), ranging from r = �0.17 to �0.69.The Norwegian FFMQ total score was inversely correlated with all indicators of psychological health: neuroticism (r = �0.61), ruminative tendencies(r = �0.41), self-related negative thinking (r = �0.40), emotion regulation difficulties (r = �0.66) and depression (r = �0.46 to r = �0.65). In con-trast to the other FFMQ subscales, the FFMQ Observe subscale did not have a positive relation to psychological health in our mostly non-meditatingsample. However, being able to non-judgmentally observe one’s inner life and environment is a part of the mindfulness construct that might emergemore clearly with more mindfulness training. We conclude that the Norwegian FFMQ has acceptable psychometric properties and can be recommendedfor use in Norway, especially in studies seeking to differentiate between different aspects of mindfulness and how these may change over time.

Key words: FFMQ, mindfulness, validity, emotion regulation, rumination, Norway.

Ingrid Dundas, University of Bergen, Christiesgate 12, 5015 Bergen, Norway, Tel: +47 55583184; fax: +47 55 589877; e-mail: [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

The concept and practice of mindfulness is met with increasinginterest within the health and mental health field in Norway.Derived from Buddhist meditation practice, mindfulness denotesnon-judgmental awareness of present experience (Bishop, Lau,Shapiro et al., 2004). The tendency to respond mindfully mayincrease with mindfulness practices, for example meditation.However, varying degrees of mindfulness may also occur amongindividuals who neither know nor practice mindfulness medita-tion or any other mindfulness practices. The trait-like tendencyto be aware of experience in a present-centered and acceptingmanner, regardless of whether this is due to training or not, canbe referred to as dispositional mindfulness.A number of interventions have been developed that include

the cultivation of mindfulness as a therapeutic strategy. Recentreviews indicate that mindfulness-based approaches have benefi-cial effects on a number of disorders and presenting problems(Chiesa & Serretti, 2011; Evans, Ferrando, Findler, Stowell,Smart & Haglin, 2008; Piet & Hougaard, 2011; Vøllestad,Sivertsen & Nielsen, 2011).In order to understand how mindfulness is related to mental

health and to therapeutic outcome, a reliable instrument measur-ing this concept is needed. A search of available instrumentsindicated that the Five Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire is broadand psychometrically sound (Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer& Toney, 2006; Baer, Smith, Lykins et al., 2008). Our aim wasto translate this scale into Norwegian, and examine the psycho-metric properties of this scale in 3 Norwegian samples.

The FFMQ was originally developed from an exploratory fac-tor analysis of pooled items from five other mindfulness ques-tionnaires. This analysis yielded five factors (Baer et al., 2006).In the following we describe these five factors, with the abbrevi-ations given them by Baer et al. (2006) in brackets. The factorsreflected a tendency or ability to (1) be aware of inner experi-ences as well as one’s surroundings (observe), (2) put innerexperiences into words (describe), (3) act with full awarenessand presence rather than in a distracted manner (actaware), (4)refrain from judging one’s experiences and instead relating to itwith a stance of acceptance (non-judge), and (5) not to reactexcessively to inner experience (non-react).A subsequent confirmatory factor analysis tested this model.

However, in a sample with little mindfulness experience, theFFMQ observe factor did not load on the overall mindfulnessfactor (Baer et al., 2006). Also, items of the observe subscaledid not correlate as expected with items of the non-judge sub-scale. When the items comprising the observe subscale wereremoved and the factor analysis re-run, a hierarchical four factorsolution showed a good fit to the data. Baer et al. (2006) notedthat this could be understood as reflecting that individuals with-out meditation experience may typically have more difficultieswith attending to inner experiences without evaluating or judgingthem. To test this, the factor analysis was repeated in two sam-ples of more experienced participants (Baer et al., 2006, 2008).In these more experienced samples, the observe factor loaded onthe overall mindfulness factor and a five factor structure fit thedata well. Since we expected our sample to have littlemindfulness experience, we expected that a hierarchical four

© 2013 The Authors.Scandinavian Journal of Psychology © 2013 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations. Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 9600 GarsingtonRoad, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA. ISSN 0036-5564.

Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 2013, 54, 250–260 DOI: 10.1111/sjop.12044

factor solution (with the Observe items removed) might fit thedata best.Several other models of mindfulness have also been sug-

gested. Brown and Ryan (2003) argue that mindfulness is one-dimensional, and have found support for this using their ownmindfulness measure, the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale(MAAS). Bishop et al. (2004) have offered an operational defi-nition of mindfulness that encompasses two broad dimensions:awareness and acceptance. The first dimension involves a self-regulation of attention so that present experience is held inawareness. The second dimension involves attending to presentexperience with an attitude of curiosity, openness and accep-tance. In addition to the five and four factor structure, theseother structures were also examined in the current study.As a test or convergent validity, we examined the FFMQ’s

association with another well-established measure of mindful-ness, MAAS (Brown & Ryan, 2003). Although the MAAS isone-dimensional and the FFMQ consists of five facets, both aremeasures of mindfulness and can be expected to correlate.As tests of conceptual validity, we examined the scale’s correla-

tion with other relevant constructs, which we will describe in thefollowing. First, we expected to find an inverse correlation betweenmindfulness and neuroticism as measured by the neuroticism sub-scale of the personality inventory NEO-Five Factor Inventory(NEO-FFI; Costa &McCrae, 1992). Neuroticism refers to a person-ality trait characterized by a disposition to react with negative emo-tional states such as anxiety and worry (McCrae & Costa, 1987).Neuroticism was the NEO personality trait of the “Five Factor”model, which most strongly and consistently correlated with mind-fulness in a recent meta-analysis (Giluk, 2009). In that study, thesample-size weighted mean observed correlation computed from 18samples with a total sample size of N = 3,309, was r = �0.45. Thatfinding can be interpreted as an indication that mindfulness counter-acts the tendency for worry and high-strung nervousness character-izing the personality trait neuroticism. A person with a dispositionfor reacting mindfully might instead accept with awareness andequanimity the actuality of those experiences that “are alreadythere” (Kabat-Zinn, 1990).Second, we expected to find that high scores on the FFMQ

were associated with less depressive tendencies. There are boththeoretical and empirical reasons to expect mindfulness to beinversely related to depressive tendencies. Mindfulness isassumed to constitute a form of metacognitive awareness thatreduces vulnerability to depressive relapse in formerly depressedindividuals. Teasdale et al. (2002, p. 275) define metacognitiveawareness as “a cognitive set in which negative thoughts andfeelings are experienced as mental events, rather than the self .”Mindfulness involves observing thoughts and feelings as passingevents in the mind, without judging them as good or bad or as areflection of the goodness or badness of the person. This attitudewould be expected to reduce excessive self-criticism and proba-bility of depressive relapse. Empirically, mindfulness-based inter-ventions have been consistently shown to be associated withdecreases in depressive symptoms and the prevention of depres-sive relapse in clinical samples (Kuyken, Byford, Taylor et al.,2008). Also, mindfulness has been found to be inversely relatedto depressive traits in a normal population (Zvolensky, Solomon,McLeish, Cassidy, Bernstein & Yartz, 2006).

Third, we expected mindfulness to be associated with emotionregulation skills. Emotion regulation skills refer to the ability tocope with difficult emotional states. Hayes and Feldman (2004)argue that mindfulness is incompatible with dysfunctional emo-tion regulation strategies such as emotional avoidance or emo-tional over-engagement. As mentioned above, mindfulnessencompasses an ability to observe distressing thoughts as “justthoughts,” rather than as necessarily accurate representations ofreality. Mindfulness also involves accepting emotions as “alreadythere” without trying to get rid of them or blaming oneself forhaving them. Such an attitude may reduce the likelihood thatdistressing thoughts and emotions will trigger escalating distress(Linehan, 1993; Teasdale, Segal & Williams, 1995). It has alsobeen suggested that the non-judgmental and non-reactive aware-ness that characterizes mindfulness may function in the sameway as exposure therapy to reduce excessive emotional reactivityand/or avoidance (Hayes & Feldman, 2004). Studies have foundan inverse association between mindfulness and emotion regula-tion difficulties in non-clinical samples such as the present (Baeret al., 2006; Lykins & Baer, 2009; Vujanovic, Bonn-Miller,Bernstein, McKee & Zvolensky, 2010).Finally, we expect mindfulness as measured by the FFMQ to be

inversely related to rumination and self-related negative thinking.Rumination involves repeatedly and non-productively turning amatter over in the mind. Mindfulness encompasses the ability toobserve ruminative thoughts as just thoughts, rather than ponderingupon them as if they were direct reflections of reality that needed tobe sorted out by thinking them through over and over. The samegoes for habitual self-related negative thinking. Mindfulnessinvolves not taking such thoughts as reflections of reality, or of per-sonal inadequacies. Instead, the mindfulness practitioner may betold to just watch thoughts and feelings as “something minds do.”In this manner, ruminative tendencies and negative self-relatedthoughts may be allowed to pass rather than perpetuated and esca-lated. For these reasons we expected a tendency to be mindful to beassociated with less ruminative tendencies and less habitual nega-tive self-related thinking.

METHOD

Procedure

In translating the FFMQ we followed recommendations from severalsources (i e., Bullinger, Alonso, Apolone et al., 1998; Sireci, Yang,Harter & Ehrlich, 2006; Van de Vijver & Hambleton, 1996). Thetranslation placed emphasis on conceptual rather than literal equiva-lence, included back-translation and a series of steps involving sevendifferent translators. A detailed description of the steps involved inthe translation procedure may be found in the online version of thisarticle at the publisher’s web site. After translation, the Norwegianversion of the FFMQ was tested with Norwegian psychology studentsin three studies. In all three studies, packages of questionnaires weredistributed during breaks in lectures attended by 100–400 students.These included questions of age, gender, and familiarity with mindful-ness; and questionnaires specific for each study as described in thefollowing.

In Study 1, we distributed 250 packages of questionnaires includingthe FFMQ (Baer et al., 2006) the MAAS (Brown & Ryan, 2003) andthe NEO-FFI (Costa & McCrae, 1992) to a sample of psychologystudents during a break in a lecture. Results for the NEO-FFI subscale

© 2013 The Authors.Scandinavian Journal of Psychology © 2013 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations.

FFMQ in Norway 251Scand J Psychol 54 (2013)

Neuroticism are reported in the present article. Of the 250 distributedpackages of questionnaires, 201 (80%) were returned.

In Study 2, we distributed to another sample of psychology students370 packages containing the two mindfulness measures (FFMQ andMAAS), a measure of emotion regulation difficulty: the Difficulties inEmotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004), and onemeasure of depression: either Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck,Steer & Brown, 1996) or the Symptom Checklist-90 Revised Depressionsubscale (SCL-90-R; Derogatis, 2000). As in study 1, this was done dur-ing a break in their lecture. The use of two different depression scalesenabled a check on whether correlation patterns found for one scale werealso evident with the other. To avoid overloading participants, we didnot include both depression questionnaires simultaneously in the pack-ages. Of the 300 packages containing the BDI-II, 264 (88%) werereturned (sample 1 a), of the 70 packages containing the depression sub-scale of SCL-90-R, 64 (91%) were returned (Sample 1 b).

In Study 3, we distributed to a third sample of psychology students320 packages containing the two mindfulness measures. Also includedwere the depression subscale of the SCL-90-R (Derogatis, 2000), therumination subscale of the Rumination-reflection Questionnaire (RRQ;Trapnell & Campbell, 1999) and a scale of self-related habitual negativethinking, Habit Index of Negative Thinking (HINT; Verplanken, Friborg,Wang, Trafimow & Woolf, 2007). Of the 320 distributed packages ofquestionnaires, 264 (83%) were returned.

Students were informed both orally and in writing about the purposeof the study and that participation was voluntary. They returned com-pleted questionnaires to research assistants at the end of the break orafter the lecture if they needed more time. Students who did not wish toparticipate left the questionnaires in the bench rows or did not take thequestionnaires when these were handed out. In study 1, participants wereoffered to take part in a lottery with two coupons with a value of 50 dol-lars each as the reward. No compensation was given for participation instudies 2 and 3. No identifying information was collected. The Norwe-gian Data Inspectorate was given notice of the study.

Participants

Participants were first year psychology students. Most (78% of the totalsample) were women. Average age was 21.7 years (background variablesfor each study and for the total sample are presented in Table 1).

Instruments

Familiarity with mindfulness. Familiarity with mindfulness was mea-sured with a single question developed for this study with the

response-alternatives: Not familiar with mindfulness, knows the conceptbut has no mindfulness practice, uses mindfulness monthly or more, usesmindfulness weekly or more, or uses mindfulness daily or more.

Five Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire; FFMQ

The Five Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al., 2006) mea-sures a general tendency to be mindful in daily life. As mentioned in theintroduction, it is a 39-item self-report instrument developed through factoranalysis of a combined pool of items from five other mindfulness question-naires. Respondents are asked to rate each item on a five-point Likert-typescale from “never or very rarely true” to “always or almost always true.” Asmentioned above, Baer et al.’s (2006) exploratory factor analysis of the fiveother mindfulness questionnaires suggested five facets or subscales describ-ing tendencies or abilities to respond mindfully. These were: (1) observe,which indicates the tendency or ability to observe one’s inner life and sur-roundings, for example: “When I’mwalking, I deliberately notice the sensa-tions of my body moving,” (2) describe, which indicates the ability todescribe feelings, for example: “I’m good at finding words to describe myfeelings,” (3) actaware/act with awareness, which indicates the tendency orability to act with awareness rather than distraction, for example: “When Ido things, my mind wanders off and I’m easily distracted” (reversed), (4)non-judge, which indicates the tendency or ability to refrain from judgingone’s experiences and instead relating to it with a stance of acceptance, forexample: “I criticize myself for having irrational or inappropriate emotions”(reversed) and (5) non-react, which indicates the tendency or ability not toreact excessively to inner experience, for example: “I perceive my feelingsand emotions without having to react to them.” Baer et al. (2008) reportedadequate to good internal consistency of the scales (range 0.72 to 0.92). Par-ticipants who meditated weekly or more rated themselves higher on theFFMQ subscales observe, describe, non-judge and non-react, and theseFFMQ subscales completely mediated the relationship between mindful-ness experience and well-being in Baer et al.’s (2008) study.

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale, MAAS

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale, MAAS (Brown & Ryan, 2003)was used in all three studies. This is a 15-item single factor self-reportinstrument constructed to assess individual differences in the frequencyof mindful states over time. Items indicate a lack of mindfulness, definedas a lack of awareness of what is occurring in the present, for example,“I rush through activities without being really attentive to them.” Thereis evidence that the scale is one-dimensional, and that mindfulness asmeasured by the scale is positively related to a variety of well-being con-structs, and to how many years of mindfulness practice the respondenthas (Brown & Ryan, 2003; MacKillop & Anderson, 2007). In a Swedishtranslation, high mindfulness on the MAAS was shown to correlate posi-tively with self-rated health (r = 0.31, p = 0.003) and negatively withjob-related burnout (r = �0.52, p < 0.001) in a sample of universityemployees. High MAAS mindfulness scores correlated negatively withdeliberate self-harm in a sample of adolescents (r = �0.31, p < 0.01),and negatively with trait anxiety in a military conscript sample(r = �0.35, p = 0.014; Hansen, Lundh, Homman & W�angby-Lundh,2009). We used a Norwegian translation of the scale with five-pointresponse scales that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (stronglyagree). The translated MAAS has shown good internal reliability in aNorwegian population (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76; Verplanken et al.,2007). Since the items on MAAS reflect a lack of mindfulness, lowscores indicate high mindfulness.

Neuroticism Subscale of the NEO-Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI Neuroticism)

The Neuroticism subscale of the NEO-Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI;Costa & McCrae, 1992) used in Study 1 is designed to measure prone-ness to psychological distress. The NEO-FFI has been developed from

Table 1. Background variables in the three studies

Study 1(N = 201)

Study 2(N = 328)

Study 3(N = 263)

Total(N = 792)

Age, mean (SD) 22.6 (4.3) 21.5 (4.4) 21.3 (4.1) 21.7 (4.3)Gender (percentwomen)

78 75 81 78

Knowledge ofmindfulness:None (%) 64 81 86 78Knows concept,no practice (%)

4 2 4 3

Practices monthlyor more, but lessthan weekly (%)

5 2 1 2

Practicesweekly (%)

7 5 4 6

Practices moreoften thanweekly (%)

20 10 4 11

© 2013 The Authors.Scandinavian Journal of Psychology © 2013 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations.

252 I. Dundas et al. Scand J Psychol 54 (2013)

the longer NEO-PIR. It consists of nine items, scored on a five itemLikert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree, for example: “I’mnot a worrier” (reversely scored). The NEO-FFI neuroticism subscale hasshown to correlate highly with the full NEO-PIR Neuroticism scale(r = 0.92, p < 0.001). It also correlated as expected with self-reportedtraits (on an adjective check-lists) three years earlier (r = 0.62,p < 0.01), spouse ratings on the NEO-PIR (r = 0.52, p < 0.01) and peerratings on the NEO-PIR (r = 0.36, p < 0.01)(Costa & McCrae, 1992).

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS)

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer,2004) was used in Study 2. Participants indicate how often each of 36 itemsapplies to them on a five-point Likert-type scale, from almost never to almostalways. Six subscales indicate various dimensions of emotion regulation.These are: (1) lack of acceptance of emotions (DERS non-accept, e.g.,“When I’m upset, I feel guilty for feeling that way”); (2) inability to engagein goal-directed behaviour when distressed (DERS goal, e.g., “When I’mupset, I have difficulty getting work done”); (3) impulse control difficulties(DERS impulse, e.g., “When I’m upset, I become out of control”); (4): lackof emotional awareness (DERS aware, e.g. “I am attentive to my feelings” –reversed); (5) limited access to strategies for effective regulation (DERSstrategies, e.g., “When I’m upset, I believe that there is nothing I can do tomake myself feel better”); and (6) lack of clarity of emotions (DERS clarity,e.g., “I have difficulty making sense out of my feelings”). Respondents areasked to indicate how often each statement applies to them, from almostnever to almost always. The DERS is reported to show good internal consis-tency, test-retest reliability and validity in student samples (Gratz & Roemer,2004) and also good validity in a clinical population (Gratz, Lacroce &Gunderson, 2006). We translated this scale on the basis of the original and aSwedish translation (Friberg, 2006) for use in the present study.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II)

The 21-item Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996) wasused in Study 2. Respondents are asked to choose between four state-ments increasingly indicative of depression. They are asked to choosethe statement that best describes how they have been feeling the last2 weeks. Examples of the lowest and highest response alternatives are:“have not lost interest in other people or activities” to “It’s hard to getinterested in anything.” The scale has shown good psychometric qualitiesin the original version (Beck, Steer & Garbin, 1988). The Norwegiantranslation has shown good reliability and validity in a sample of 303Norwegian university students (Aasen, 2001).

Depression subscale of the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90 Depression)

The Depression subscale of the Symptom Checklist-90 Revised (SCL-90-R Derogatis, 2000) was used in study 2 and 3. The SCL-90-R is a 90-item self-report inventory of psychiatric problems. The respondent isasked to indicate how much each problem (for example, crying easily)has bothered him/her during the last 7 days by ranging each item on afive-point Likert scale where 0 indicates not at all and 4 indicates verymuch. We used the 13-item depression subscale, which covers low affectand mood, lack of interest, lack of vitality and positive motivation, hope-lessness and helplessness. This scale has shown good psychometric prop-erties in a Norwegian translation (Vassend, Lian & Andersen, 1992).

Rumination Subscale of the Rumination-reflection Questionnaire,RRQ-Rum

The 12-item Rumination subscale of the Rumination-Reflection Ques-tionnaire (RRQ; Trapnell & Campbell, 1999) was used in Study 3. Itreflects a tendency to dwell on the possible negative and disappointingmeanings of prior personal events or experiences, for example: “I tend to

‘ruminate’ or dwell over things that happen to me for a really long timeafterward.” The scale is scored on a five-point Likert-type scale fromstrongly disagree to strongly agree. The Norwegian translation of thescale has been found to have a high internal reliability (Cronbach’salpha = 0.91), and to correlate negatively with self-esteem, habitual neg-ative thinking and mindfulness (Verplanken et al., 2007).

Habit Index of Negative Thinking (HINT)

The 12–item HINT (Verplanken et al., 2007) used in Study 3 reflects thefrequency, automaticity and habitualness of negative thinking aboutoneself. Participants are asked to indicate how much statements applyto them on a five-point Likert scale from highly disagree to highly agree,for example: “Thinking negatively about myself is something I dofrequently.” The scale has shown high internal reliability in Norwegianstudents (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94), and has been shown to predict(beyond similar constructs) concurrent self-esteem, and anxiety anddepressive symptoms 9 months later in non-clinical Norwegian respon-dents (Verplanken et al., 2007).

Analysis

Analyses were conducted with CSS/Statistica (Statsoft, Tulso, OK), andSPSS (IMB, Armonk, NY). For the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA),we used the SPSS software AMOS. We used p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 aslevels of significance in all analyses.

RESULTS

Familiarity with mindfulness

In the pooled sample, most (78%) had no familiarity with mind-fulness (Table 1). A few (3%) knew the concept of mindfulnessbut did not practice mindfulness themselves. Nineteen percentpracticed mindfulness monthly or more (Table 1).

Associations between background variables

In the pooled sample, older students rated themselves as havingmore knowledge of mindfulness (r = 0.27, p < 0.01., 95% CIs:[0.20, 0.33]) and scored themselves as more mindful on the FFMQ(r = 0.20, p < 0.01., 95% CIs [ 0.13, 0.27]), and on the MAAS(r = �0.16, p < 0.01, 95% CIs [�0.23, �0.09]). Students whoscored themselves as more knowledgeable about mindfulness, alsoscored themselves as more mindful on the FFMQ (r = 0.18,p < 0.01, [95% CIs: 0.11, 0.24]), and on the MAAS, although thecorrelation for MAAS was somewhat weak: r = �0.07, p < 0.05,95% CIs [�0.14, �0.003]). Age and knowledge of mindfulnesswere not related to other variables in the three studies, with theexception that younger students admitted to more emotion regula-tion difficulties on the DERS (study 2, r = 0.17, p < 0.01, 95% CIs[0.06, 0.28]). Consistently across studies, women rated themselvesas more emotionally reactive than men on the non-react subscale ofthe FFMQ (pooled sample: r = �0.15, p < 0.01, 95% CI [�0.22,�0.08]).

The scales

The descriptive statistics for scales used in the three studies arereported in Table 2. All Cronbach’s alphas were acceptable,ranging from 0.69 to 0.95.

© 2013 The Authors.Scandinavian Journal of Psychology © 2013 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations.

FFMQ in Norway 253Scand J Psychol 54 (2013)

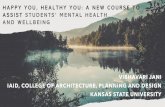

Confirmatory factor analysis of the FFMQA confirmatory factor analysis of the Norwegian version ofFFMQ was done on all three samples in sequence, and on thepooled sample. Since the results from the pooled sample closelyreflected the results from each sample, only results from thepooled sample are presented here (Table 3).We began by testing a five factor model with a higher order

mindfulness factor. On the basis of modification indexes fromthis analysis, the error terms of items 5 and 13 were allowed tocorrelate. Both item 5 and 13 belong to the FFMQ actaware sub-scale. Their wordings are quite similar: “When I do things, mymind wanders off and I’m easily distracted” and “I am easilydistracted.” The remaining items of this subscale describe beingon autopilot or not paying attention. Allowing the error terms ofitem 5 and 13 to correlate is theoretically meaningful, sincebeing distracted may be somewhat different from being on auto-pilot or not paying attention.After running the analysis with these error-terms correlated,

the modification indexes suggested that error terms of item 12and item 16 should be allowed to correlate. These items arefrom the FFMQ describe subscale, and the wordings of theseitems are: “It’s hard for me to find the words to describe whatI’m thinking” and “I have trouble thinking of the right words toexpress how I feel about things.” Allowing error terms of theseitems to correlate is theoretically and methodologically reason-able given the similarity in wording of these items. After theseadjustments were made, further adjustments were not clearlyjustified by theory and did not notably increase the fit of themodel.Model fit indexes are shown in Table 3. The five factor model

approached an acceptable fit to the data, with a CFI of 0.89.

This approaches the criteria of 0.90, which has served as a rule-of-thumb lower limit cut-point of acceptable fit according toByrne and Gavin (1996), although it does not reach the morestringent criteria of 0.95 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The RMSEAwas acceptable (RMSEA = 0.05, 90% Cls [0.045, 0.050]). Forthe RMSEA, a score less than 0.05 is considered good, while ascore less than 0.08 is considered adequate. The Chi-square(1961.48) was significant and thus did not show a good fit, butthe Chi-square is commonly overly sensitive in large samples,and the Chi-square/df (2.82) was acceptable (Kline, 1998). Allsubscales loaded significantly on the overall mindfulness factor(Fig. 1).As mentioned, Baer et al. (2006) found that for samples low

in meditation experience, a four factor solution with the observefactor removed was superior to a five factor solution. To testthis, we ran a four factor model next. This showed a fit that wasapproximately the same as a five factor model (Table 3).Baer et al. (2008) reported that a five factor model fit the data

better in samples with more mindfulness experience. We re-ranthe analysis with the 126 participants who reported that theypracticed mindfulness weekly or more often (Table 3). The fivefactor model did not fit the data better in this subsample.As a last attempt to explore whether a four factor solution

would fit the data better with mindfulness-na€ıve subjects, we ranthe confirmatory factor analysis on the subsample that reported noknowledge of mindfulness (N = 616). A four factor solutionshowed an acceptable fit in this sample with mindfulness-na€ıveparticipants (Chi square = 1055.86, Chi square/df = 2.5,CFI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.05, 90% Cls [0.045, 0.053]). For thesake of simplicity, (results for this sample are not reported in thetable). However, a five factor solution showed a similar fit in this

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for all measures

Mean [95% Confidence Intervals] Cronbach’s alpha

Study 1 N = 201 Study 2 N = 328 Study 3 N = 263 Total N = 792

Study 1

N = 201

Study 2

N = 328

Study 3

N = 263

Total

N = 792

FFMQ

total

130.50 [128.6, 132.2] 129.33 [127.9, 130.9] 126.40 [124.5, 128.3] 128.74 [127.7, 129.7] 0.86 0.84 0.86 0.86

FFMQ

observe

26.35 [25.6, 27.0] 27.77 [27.2, 28.3] 27.21 [26.6, 27.8] 27.24 [26.9, 27.6] 0.77 0.72 0.75 0.75

FFMQ

describe

29.36 [28.6, 30.0] 29.31 [28.7, 29,9] 28.78 [28.2, 29.4] 29.17 [28.8, 29.5] 0.91 0.89 0.88 0.89

FFMQ

actaware

25.74 [25.1, 26.3] 24.90 [24.4, 25.4] 24.23 [23.7, 24.8] 24.91 [24.6, 25.2] 0.84 0.82 0.84 0.83

FFMQ

non-judge

27.76 [26.9, 28.6] 26.28 [25.6, 27.0] 25.64 [24.9–26.4] 26.45 [26.0, 26.9] 0.91 0.88 0.89 0.89

FFMQ

non-react

21.28 [20.8, 21.8] 21.08 [20.7, 21.5] 20.54 [20.1, 21.0] 20.97 [20.7, 21.2] 0.76 0.69 0.73 0.72

MAAS 40.68 [39.6, 41.7] 41.44 [40.6, 42.3] 41.84 [40.7, 42.9] 41.30 [40.7, 41.9] 0.74 0.81 0.84 0.82

DERS / 86.46 [84.5, 88.7] / / / 0.93 / /

BDI–II / 7.75 [6.9, 8.6] / / / 0.88 / /

SCL–90depression

/ 19.27 [16.4, 22.2] 14.53 [13.4–15.6] / / 0.90 0.88 /

NEO–FFIneuroticism

21.59 [20.5, 22.7] / / / 0.86 / / /

Rumination / / 41.91 [40.8, 43.0] / / / 0.89 /

HINT / / 32.93 [31.3, 34.4] / / / 0.95 /

Notes: / = the measure was not used in this study. FFMQ = Five Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire, FFMQ actaware = act with awareness subscale ofthe FFMQ, MAAS = Mindful Attention Awareness Scale, DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II,SCL-90 depression = depression subscale of the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised, NEO-FFI neuroticism = neuroticism subscale of the NEO–Five FactorInventory, Rumination = rumination subscale of the Rumination–reflection Questionnaire, HINT = Habit Index of Negative Thinking.

© 2013 The Authors.Scandinavian Journal of Psychology © 2013 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations.

254 I. Dundas et al. Scand J Psychol 54 (2013)

sample of mindfulness-na€ıve participants (Chi square = 1706.21,Chi-square/df = 2.5, CFI = 0.88, RMSEA = 0.05, 90% Cls[0.046, 0.052]), so the four factor solution was no better thana five factor solution in this sample. To sum up, overall a fiveand a four factor structure were approximately similar in theirfit to the data in our samples, regardless of experience withmindfulness.A one factor model was then tested. This model was based

upon Brown and Ryan’s (2003) aforementioned suggestion thatmindfulness is one-dimensional. This model did not fit the cur-rent FFMQ data (Table 3). Finally we tested a two factor model,T

able

3.Model

fitindexesfordifferent

modelsof

theFFMQ

Five

with

higher

ordermindfulness

factor

Four

with

higher

ordermindfulness

factor

Twofactor

(Pooled

sample)

One

factor

(Pooled

sample)

Pooled

sample(N

=792)

With

mindfulness

practice

(N=126)

Pooled

sample

(N=792)

With

mindfulness

practice(N

=126)

Chi

square

1961.48

1122.98

1185.39

662.62

5442.16

6975.33

Chi

square/df

2.82

1.62

2.78

1.55

7.76

9.97

CFI

0.89

0.79

0.92

0.86

0.58

0.44

RMSE

A[90%

Cls]

0.050[0.045,0.050]

0.070[0.063,0.078]

0.47

[0.044,0.050]

0.066[0.056,0.076]

0.09290%

CIs

[0.095,0.090]

0.10690%

CIs

[0.106,0.109]

Notes:FF

MQ

=Five

Factor

Mindfulness

Questionnaire.

Fig. 1. Five factor model of Mindfulness for total sample. The coeffi-cients describing the loadings on the five facets on the broad mindfulnessconstruct are maximum likelihood estimates (standardized regressionweights). Obs = observe, Des = describe, Act = act with awareness,NJ = non-judge, NR = non-react. Each of the five facets was representedby the items of the corresponding subscale, eight items for each facetexcept non-react, which was represented by 7 items. Error terms havebeen removed for simplicity of presentation. The numbers in the boxesrefer to items of the FFMQ.

© 2013 The Authors.Scandinavian Journal of Psychology © 2013 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations.

FFMQ in Norway 255Scand J Psychol 54 (2013)

as suggested by Bishop et al. (2004) and described in theintroduction. According to this model, mindfulness consists ofan awareness dimension and an acceptance dimension. Wegrouped the FFMQ items from FFMQ sub-factors observe,describe and actaware on the awareness factor, and the FFMQitems non-judge and non-react on the accept factor. Since a twofactor model with correlated factors is identical with a two factormodel with a higher order factor, it did not make sense toinclude a higher order mindfulness factor. This two factor modeldid not fit the data either (Table 3).To sum up, a five factor model and a four factor model with

Observe items removed represented the data similarly well, andfar better than a one or two factor solution. Since all subfactorsloaded on the overall mindfulness factor in the five factor model,it did not seem appropriate to choose a four factor model abovethe five factor model. The five factor model is presented inFig. 1.

Association between the mindfulness measures

In order to test the convergent validity of the Norwegian FFMQ,the scales were correlated with the MAAS, and with each other.Correlations between the total FFMQ score, all FFMQ subscalesand MAAS are shown in Table 4. All correlations were signifi-cant and in the expected direction, with one exception: theFFMQ Observe subscale correlated negatively, rather thanpositively, with the FFMQ non-judge subscale (r = �0.15,p < 0. 01, 95% CIs [�0.22, �0.08]). For the subsample of 616mindfulness-na€ıve participants, the correlation was similar to thesample as a whole (r = �0.18, 95% Cls: [�0.20, �0.08], notshown in Table 4). This negative correlation between the FFMQsubscales observe and non-judge has been reported in the origi-nal mostly non-meditating sample (Baer et al., 2006). When werestricted the analysis to participants who reported using mind-fulness weekly or more often (N = 126) this negative correlationbetween observe and non-judge became non-significant(r = �0.04, [95% Cls �0.21, 0.14], not shown in Table 4).

Associations between the mindfulness measures and othermeasures

Table 5 shows correlations between mindfulness measures(FFMQ total and subscales, and MAAS), and other relevant psy-chological constructs. Most of the correlations were significantand in the hypothesized directions. Both the FFMQ totaland MAAS correlated significantly with neuroticism. The twomindfulness scales, total scores also correlated as expected withemotion regulation measures (DERS total and DERS subscales).Both mindfulness scales’ also correlated with the depressionmeasures (SCL-90 Depression subscale and BDI-II).With regard to the subscales of the FFMQ, there were some

unexpected correlations (Table 5). First, the FFMQ subscaledescribe did not correlate with the rumination subscale, nor didthe FFMQ subscale describe correlate with the BDI-II subscale(r = �0.12, 95% CIs [0.25, �0.00]). Second, the FFMQ non-judge subscale failed to correlate as expected with the emotionregulation subscale DERS aware. Third, the FFMQ observesubscale failed to correlate as expected with all but one of the T

able

4.Correlatio

nsbetweenthetwomindfulness

measuresandbetweenFFMQ

subscalesin

thepooled

sample(N

=792)

FFMQ

total

Observe

aDescribea

Actaw

area

Non-judge

aNon-reacta

MAAS

–0.62**[–0.67,–0.56]

–0.20**[–0.26,–013]

–0.33**[–0.39,–0.26]

–0.69**[–0.74,–0.64]

–0.36**[–0.42,–0.29]

–0.17**[–0.24,–0.10]

Observe

a0.45**

[0.38,

0.51]

0.25**

[0.20,

0.34]

0.08*[0.01,

0.15]

–0.15**[–0.22,–0.08]

0.21**

[0.14,

0.28]

Describe

a0.63**

[0.58,

0.68]

0.25**

[0.19,

0.32]

0.13**

[0.06,

0.20]

0.13**

[0.06,

0.20]

Actaw

are

a0.65**

[0.60,

0.71]

0.36**

[0.30,

0.43]

0.17**

[0.10,

0.24]

Non-judge

a0.61**

[0.55,

0.66]

0.17**

[0.11,

0.24]

Non-react

a0.51**

[0.45,

0.57]

Notes:FF

MQ

=Five

Factor

Mindfulness

Questionnaire,FF

MQ

actaware=actwith

awareness,

MAAS=Mindful

Attention

AwarenessScale,

aFF

MQ

subscale,95%

CIs

insquare

brackets,*

p<

0.05,

**p<

0.01.

© 2013 The Authors.Scandinavian Journal of Psychology © 2013 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations.

256 I. Dundas et al. Scand J Psychol 54 (2013)

Table

5.Correlatio

nsbetweenmeasuresof

mindfulness

(FFMQ,FFMQ

subscalesandMAAS)

andothermeasuresin

allthreestudies.

FFMQ

total

FFMQ

observe

FFMQ

describe

FFMQ

actaware

FFMQ

non-judge

FFMQ

non-react

MAAS

Study1

NEO–F

FINeurotism

–0.61**[–0.72,–0.50]

0.04

[–0.10,0.18]

–0.32**[–0.45,–0.18]

–0.35**[–0.48,–0.22]

–0.59**[–0.70,–0.48]

–0.49**[–0.61,–0.37]

0.36**

[0.23,

0.49]

Study2

DERS

totalscore

–0.66**[–0.74,–0.57]

–0.08[–0.19,0.03]

–0.34**[–0.45,–0.24]

–0.47**[–0.57,–0.38]

–0.53**[–0.62,–0.44]

–0.39**[–0.49,–0.29]

0.56**

[0.47,

0.65]

DERS

Non-accept

–0.48**[–0.57,–0.38]

0.07

[–0.04,0.17]

–0.18**[–0.29,–0.08]

–0.24**[–0.34,–0.13]

–0.66**[–0.74,–0.57]

–0.18**[–0.29,–0.08]

0.37**

[0.27,

0.47]

DERS

Goal

–0.38**[–0.48,–0.27]

–0.05[–0.16,0.06]

–0.15**[–0.25,–0.04]

–0.40**[–0.50,–0.30]

–0.21**[–0.31,–0.10]

–0.30**[–0.40,–0.20]

0.41**

[0.31,

0.51]

DERS

Impulse

–0.46**[–0.56,–0.37]

–0.02[–0.13,0.09]

–0.19**[–0.30,–0.08]

–0.39**[–0.49,–0.29]

–0.38**[–0.48,–0.28]

–0.31**[–0.41,–0.21]

0.42**

[0.32,

0.52]

DERS

Aware

–0.33**[–0.43,–0.23]

–0.28**[–0.38,–0.18]

–0.39**[–0.49,–0.28]

–0.20**[–0.31,–0.10]

0.04

[–0.07,0.15]

–0.17**[–0.28,–0.06]

0.21**

[0.10,

0.32]

DERS

Strategies

–0.53**[–0.62,–0.44]

–0.06[–0.17,0.05]

–0.18**[–0.29,–0.08]

–0.37**[–0.47,–0.27]

–0.48**[–0.58,–0.39]

–0.37**[–0.47,–0.27]

0.45**

[0.35,

0.54]

DERS

Clarity

–0.59**[–0.67,–0.50]

–0.10[–0.21,0.01]

–0.53**[–0.63,–0.44]

–0.39**[–0.49,–0.29]

–0.34**[–0.44,–0.24]

–0.26**[–0.36,–0.15]

0.47**

[0.37,

0.56]

SCL–90

Depression

–0.65**[–0.83,–0.45]

–0.07[–0.32,0.19]

–0.35**[–0.59,–0.11]

–0.31**[–0.56,–0.06]

–0.61**[–0.81,–0.41]

–0.37**[–0.61,–0.13]

0.45**

[0.22,

0.68]

BDI–II

–0.46**[–0.57,–0.35]

–0.05[–0.17,0.08]

–0.12[–0.25,.–0.00]

–0.42**[–0.54,–0.30]

–0.43**[–0.55,–0.32]

–0.25**[–0.37,–0.12]

0.42**

[0.31,

0.54]

Study3

Rum

ination

–0.41**[–0.52,–0.30]

0.12

[–0.01,0.26]

–0.04[–0.17,0.08]

–0.34**[–0.45,–0.22]

–0.56**[–0.66,–0.46]

–0.27**[–0.39,–0.15]

0.43**

[0.32,

0.54]

HIN

T–0.40**[–0.52,–0.29]

0.09

[–0.03,0.21]

–0.13*

[–0.25,–0.00]

–0.30**[–0.41,–0.18]

–0.55**[–0.65,–0.45]

–0.21**[–0.32,–0.09]

0.37**

[0.26,

0.48]

SCL–90

Depression

–0.47**[–0.58,–0.36]

0.03

[–0.10,0.15]

–0.17**[–0.29,–0.05]

–0.40**[–0.51,–0.28]

–0.46**[–0.57,–0.35]

–0.28**[–0.40,–0.17]

0.42**

[0.31,

0.53]

Notes:FF

MQ

=Five

Factor

Mindfulness

Questionnaire,FF

MQ

Actaw

are=Act

with

Awareness,

MAAS=Mindful

AttentionAwarenessScale,

NEO–F

FINeuroticism

=The

Neuroticism

subscale

oftheNEO–

Five

Factor

Inventory,

DERS=Difficulties

inEmotionRegulationScale,

SCL–90Depression=Depressionsubscale

oftheSy

mptom

Checklist–90–R

evised,BDI–II

=BeckDepressionInventory–

II,Rum

ina-

tion=Rum

inationSu

bscale

oftheRum

ination–Reflectio

nQuestionnaire,HIN

T=HabitIndexof

NegativeThinking,

*p<

0.05,**p<

0.01.95%

CIs

insquare

brackets.

© 2013 The Authors.Scandinavian Journal of Psychology © 2013 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations.

FFMQ in Norway 257Scand J Psychol 54 (2013)

criterion measures in Table 5. It correlated as expected only withemotion awareness as measured by the difficulties of emotion reg-ulation subscale DERS Aware (r = �0.28, p < 0.01, 95% Cls[�0.38, �0.18]). This correlation was negative, indicating that theability to observe inner experience was related to less difficultieswith emotional awareness.

DISCUSSION

All three studies converged in supporting the Norwegian FFMQas a psychometrically sound scale in these student samples. TheFFMQ and its subscales had good internal reliabilities, and theFFMQ total score and four of the subscales correlated negativelywith a range of different criterion measures: depression, neuroti-cism, rumination, negative self-related thinking and difficultieswith emotion regulation. The fifth FFMQ subscale observe,which taps the ability to observe inner and outer experience, didnot correlate negatively with our measures of psychologicalill-health. We will return to this later.Older students rated themselves as more mindful, probably

because these older students had been given more opportunity tolearn about mindfulness. Unexpectedly, gender played a consis-tent role in scores on the FFMQ non-react subscale. In all threestudies, women rated themselves lower on the non-react subscalethan men. Generally, this subscale taps an ability to pause andobserve one’s emotions, rather than being taken over by them,for example: “I watch my feelings without getting lost in them.”Gender differences would be in accordance with gender stereo-types allowing or expecting women to react emotionally morestrongly than men.The confirmatory factor analyses showed that a four and five

factor structure fit the data equally well. Thus we failed to repli-cate Baer et al.’s (2006) finding that, in a mostly non-meditatingsample a four factor solution (with the observe-items removed)fit the data better than a five-factor solution. In our sample bothfive and the four factor models were clearly superior to the oneand two factor models.In contrast to the other FFMQ subscales, the ability to observe

inner and outer experience (the FFMQ observe subscale) did notcorrelate with our criteria of psychological health, in all but oneinstance. This subscale was positively associated only with anability to be attentive and aware towards one’s emotion (theDERS aware subscale). Both the FFMQ observe subscale and theDERS Aware subscales are measures of the ability or tendency toobserve and be aware of inner experience. Interestingly, neitherof these scales correlated positively with the FFMQ non-judgesubscale. The correlations with the FFMQ non-judge subscalewere negative (r = �0.15, 95% CIs [�0.22, �0.08]) and non-significant (r = 0.04, 95% CIs [�0.05, 0.15]) for FFMQ observeand DERS aware, respectively. Perhaps observing and beingaware of inner experience does not necessarily go together with anon-judging attitude. The negative association between the FFMQsubscales observe and non-judge (r = �0.15) was no longer sig-nificant in the 126 participants who meditated weekly or more(r = �0.04, 95% Cls [�0.21, 0.14]). In agreement with thesefindings, Baer et al. (2006, 2008) reported that in their studies theFFMQ observe subscale correlated negatively with the non-judgesubscale in samples with little mindfulness practice, but this

was not the case for experienced meditators. This suggests thatmindfulness training might loosen the common but dysfunctionalassociation between observing inner experience and judging it.As mentioned, an ability to observe inner and outer experience

as measured by FFMQ Observe subscale was not associated withbetter psychological health (neuroticism, rumination, habitualnegative thinking, and depression). Neither was the ability toobserve associated with less emotion regulation difficulties, withthe exception of the DERS awareness scale mentioned earlier.Failure of the observe subscale to equivocally correlate withpsychological health has been reported earlier for samples withlittle mindfulness training. Baer et al. (2006) report that on theoriginal FFMQ, the Observe subscale correlated not only withsome expected features, but also with unexpected features such asdissociation, absent-mindedness, psychological symptoms andthought suppression in a student sample. Positive associationsbetween mindful observing and mental ill-health has also beenreported for the Observe subscales of the Kentucky Inventory ofMindfulness Skills (KIMS; Baer, Smith & Allen, 2004) in aSwedish sample (Hansen et al., 2009). As suggested by Baeret al. (2006; 2008) it might be that the observe subscale measuresa mixture of judgmental self-awareness and accepting awareness,in samples where respondents have little mindfulness experience.Watkins and Teasdale (2004) have suggested that there is adistinction between healthy self-focus and unhealthy ruminationin depression. On the basis of their own study, Hansen et al.(2009, p. 2) suggested that the KIMS observe (and describe)subscales “measure a mixture of two opposite kinds of processes:healthy self-observation (‘experiential self-focus’) and unhealthyrumination (‘analytical self-focus’)”. This might also be the casefor the FFMQ observe subscale in our study.The failure of the Norwegian FFMQ observe subscale to cor-

relate with indicators of psychological ill-health such asneuroticism or depression raises the question of whether thisscale measures the construct of mindfulness at all. However,there are at least three reasons to include the observe subscale ina scale aimed at measuring mindfulness. First, the observe sub-scale did correlate as expected with mindfulness as measured bythe MAAS and the other FFMQ subscales, suggesting that it hasat least some mindfulness features. Second, the observe subscaleloaded significantly on the overall FFMQ mindfulness factor inthe factor analysis.The third reason to include the FFMQ observe subscale in an

overall mindfulness measure is that the lack of associationsbetween the FFMQ observe factor and mental health in oursample may be related to that samples’ limited mindfulnessexperience. Patterns in the results suggested that mindfulnesstraining may increase the association between psychologicalhealth and the ability to observe, without judging, inner andouter experience. To reiterate the parts of our results that maysupport such a hypothesis: in contrast to the other subscales onDERS, the DERS awareness subscale had no association withthe FFMQ non-judge subscale in the present sample. Thissuggests that being aware of experience (DERS aware) may notbe associated with a non-judgmental attitude in a sample withlittle mindfulness experience. Second, the FFMQ observe sub-scale correlated negatively with the FFMQ non-judge subscalein the sample as a whole, but not in the subsample of 126

© 2013 The Authors.Scandinavian Journal of Psychology © 2013 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations.

258 I. Dundas et al. Scand J Psychol 54 (2013)

participants who meditated weekly or more. This may indicatethat more meditation experience may lead to a less judging atti-tude. Finally, in contrast to the negative associations betweenrumination and the other FFMQ subscales, endorsing an abilityto observe or describe feelings on the FFMQ did not correlatenegatively with the tendency to ruminate. In a sample of mostlynon-meditating participants, an ability to observe or describefeelings may not prevent judging and ruminating over thesesame feelings.Theory and clinical experience suggests that mindfulness

training may increase the ability to observe and describe subjec-tive experience without harshness and judgment. Against a back-ground of otherwise negative associations between the FFMQsubscales and indicators of ill-health (and positive associationsinternally between FFMQ subscales), the exceptions found in thepresent study are indicative that individuals with little mindful-ness experience may have difficulty observing subjective experi-ence without judgment. It also suggests that a non-judgmentalaspect of observing is necessary for observing to be associatedwith greater psychological health. The pattern is tentative ofcourse, since absence of correlations does not allow us to con-clude that they do not exist, and the design does not allow forconclusions regarding developments in the associations betweenmindfulness and psychological health over time.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Limitations of the present study were the use of self-reportinstruments only, and that the sample consisted only of students,preventing the generalization of results to broader samples. Thestudy lacked a more detailed measure of mindfulness experience,which would have needed to include length of mindfulness prac-tice as well as frequency. Also, the design of the study does notallow a testing of how scores of different subscales may changewith increasing mindfulness practice. Strengths of the presentstudy are the thorough and careful process of translating theFFMQ and that the analyses were repeated across severalsamples and instruments. The hypotheses were consistently con-firmed, and the few exceptions were theoretically meaningful.

CONCLUSION

Our conclusions are as following. First, the FFMQ seemed to bereliable, and to have good convergent and construct validity inthese Norwegian student samples. Second, the FFMQ seems toreflect five different and theoretically meaningful aspects ofmindfulness, although further research on how these facets differand how they relate to different aspects of mental health overtime is necessary to fully understand them. All subscales,including the observe subscale have an important place in anoverall measure of mindfulness. The FFMQ might be useful instudies measuring change in self-reported mindfulness over timeand after mindfulness-based interventions, since it allows a dif-ferentiation between different facets that might have changeddifferently during the intervention. The FFMQ also has a placein research with samples without mindfulness training, whenstudying how variations in different facets of mindfulness maybe associated with psychological health. We recommend the

FFMQ for use in Norway, especially in studies seeking to dif-ferentiate between different facets of mindfulness.

The authors thank Ruth Baer; PhD, Svein Folmo, Clinical Specialist,Linn Heidi Lunde, PhD; and Elisabeth Schanche, PhD for generous helpin translating the FFMQ. We also thank psychologists Trond Amundsen,Birgitte K.Gore, Janne Hammervold, Andreas R. Jensen, Ella M.Johan-sen, Simen Reigstad, Renate Scholz, Lene C. N. Steffensen and LeneUtkilen for assistance with data-collection.

REFERENCES

Aasen, H. (2001). An emprirical investigation of depression symptoms:Norms, psychometric characteristics and factor structure of the BeckDepression Inventory – II. Master Thesis, Insitute for Clinical Psy-chology, University of Bergen.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T. & Allen, K. B. (2004). Assessment of mindful-ness by self-report: The Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills.Assessment, 11, 191–206.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J. & Toney, L. R.(2006). Using Self-Report Assessment Methods to Explore Facets ofMindfulness. Assessment, 13, 27–45.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer,S., Walsh, E., Duggan, D. & Williams, J. M. G. (2008). Constructvalidity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating andnon-meditating samples. Assessment, 15, 329–342.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A. & Brown, G. K. (1996). Beck DepressionInventory – Second Edition. Manual. Norsk versjon [Norwegian ver-sion]. Oslo: NCS Pearson, Inc.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A. & Garbin, M. G. (1988). Psychometric proper-ties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evalua-tion. Clinical Psychology Review, 8, 77–100.

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D.,Carmody, J., Segal, Z. V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D. &Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition.Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 230–241.

Brown, K. W. & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present:Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Per-sonality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848.

Bullinger, M., Alonso, J., Apolone, G., Leplege, A., Sullivan, M., Wood–Dauphinee, S., Gandek, B., Wagner, A., Aaronson, N., Bech, P.,Fukuhara, S., Kaasa, S. & Ware, J. E. (1998). Translating health sta-tus questionanaires and evaluating their quality: The IQOLA Projectapproach. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51, 913–923.

Byrne, B. M. & Gavin, D. A. W. (1996). The Shavelson model revisited:Testing for the structure of academic self-concept across pre-, early,and late adolescents. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 215–228.

Chiesa, A. & Serretti, A. (2011). Mindfulness based cognitive therapyfor psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psy-chiatry Research, 187, 441–453.

Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. R. (1992). NEO-PI-R Professional manual.Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO–PI–R) and NEOFive–Factor Inventory (NEO–FFI). Lutz, FL: Psychological assess-ment resources, Inc.

Derogatis, L. R. (2000). SCL-90-R. In A. E. Kazdin (Ed.), Encyclopediaof psychology (Vol. 7, pp. 192–193). Washington, DC: AmericanPsychological Association.

Evans, S., Ferrando, S., Findler, M., Stowell, C., Smart, C. & Haglin, D.(2008). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for generalized anxietydisorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 716–721.

Friberg, �A. (2006). K€anslig f€or k€anslor? En kvantitativ studie av ettk€ansloregleringsperspektiv p�a oro och generaliserat �angestsyndrom[Sensitive to emotions? A quantitative study of worry and general-ized anxiety disorder from an emotion regulation perspective]. Psy-kologexamensarbete [Final psychology exam paper], University ofStockholm.

Giluk, T. L. (2009). Mindfulness, Big Five personality, and affect: Ameta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 805–811.

© 2013 The Authors.Scandinavian Journal of Psychology © 2013 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations.

FFMQ in Norway 259Scand J Psychol 54 (2013)

Gratz, K. L., Lacroce, D. M. & Gunderson, J. G. (2006). Measuringchanges in symptoms relevant to borderline personality disorder fol-lowing short-term treatment across partial hospital and intensive out-patient levels of care. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 12, 153–159.

Gratz, K. L. & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emo-tion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, andinitial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Jour-nal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26, 41–54.

Hansen, E., Lundh, L.-G., Homman, A. & W�angby-Lundh, M. (2009).Measuring mindfulness: Pilot studies with the Swedish versionsof the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale and the KentuckyInventory of Mindfulness Skills. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 38,2–15.

Hayes, A. M. & Feldman, G. (2004). Clarifying the construct of mindful-ness in the context of emotion regulation and the process of changein therapy. Clinical Psychology, 11, 255–262.

Hu, L. T. & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes incovariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alter-natives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe Living. New York: RandomHouse.

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation model-ing. New York: Guilford Press.

Kuyken, W., Byford, S., Taylor, R. S., Watkins, E., Holden, E., White,K. Barrett, B., Byng, R., Evans, A., Mullan, E. & Teasdale, J. D.(2008). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy to prevent relapse inrecurrent depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,76, 966–978.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline per-sonality disorder. London: Guilford Press.

Lykins, E. L. & Baer, R. A. (2009). Psychological functioning in a sam-ple of long-term practitioners of mindfulness meditation. Journal ofCognitive Psychotherapy, 23, 226–241.

MacKillop, J. & Anderson, E. J. (2007). Further psychometric validationof the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). Journal of Psy-chopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29, 289–293.

McCrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. (1987). Validation of the five-factor modelof personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personal-ity and Social Psychology, 52, 81–90.

Piet, J. & Hougaard, E. (2011). The effect of mindfulness-based cogni-tive therapy for prevention of relapse in recurrent major depressivedisorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical PsychologyReview, 31, 1032–1040.

Sireci, S. G., Yang, Y., Harter, J. & Ehrlich, E. J. (2006). Evaluatingguidelines for test adaptations: A methodological analysis of transla-tion quality. Journal of Cross–cultural Psychology, 37, 557–567.

Teasdale, J. D., Moore, R. G., Hayhurst, H., Pope, M., Williams, S. &Segal, Z. V. (2002). Metacognitive awareness and prevention ofrelapse in depression: empirical evidence. Journal of Consulting andClinical Psychology, 70, 275–287.

Teasdale, J. D., Segal, Z. V. & Williams, J. M. G. (1995). How doescognitive therapy prevent depressive relapse and why should atten-tional control (mindfulness) training help? Behaviour Research andTherapy, 33, 25–39.

Trapnell, P. D. & Campbell, J. D. (1999). Private self-consciousness andthe Five Factor Model of Personality: Distinguishing rumination fromreflection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 284–304.

Van de Vijver, F. & Hambleton, R. K. (1996). Translating tests: Somepractical guidelines. European Psychologist, 1, 89–99.

Vassend, O., Lian, L. & Andersen, H. T. (1992). Norwegian versions ofthe Neuroticism, Extraversion, and Openness (NEO) PersonalityInventory, SCL-90-Revised, and Giessen Subjective Complaints List:I. Tidsskrift for Norsk Psykologforening, 29, 1150–1160.

Verplanken, B., Friborg, O., Wang, C. E., Trafimov, D. & Woolf, K.(2007). Mental habits: Metacognitive reflection on negative self-think-ing. Journal of Personality and Social psychology. 92, 526–541.

Vujanovic, A. A., Bonn–Miller, M. O. M., Bernstein, A. A., McKee, L. G.L. & Zvolensky, M. J. M. (2010). Incremental validity of mindfulnessskills in relation to emotional dysregulation among a young adult com-munity sample. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 39, 203–213.

Vøllestad, J., Sivertsen, B. & Nielsen, G. H. (2011). Mindfulness-basedstress reduction for patients with anxiety disorders: Evaluation in arandomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49,281–288.

Watkins, E. & Teasdale, J. D. (2004). Adaptive and maladaptive self-focus in depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 82, 1–8.

Zvolensky, M. J., Solomon, S. E., McLeish, A. C., Cassidy, D., Bern-stein, A., J., B. C. & Yartz, A. R. (2006). Incremental validity ofmindfulness-based attention in relation to the concurrent prediction ofanxiety and depressive symptomatology and perceptions of health.Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 35, 148–158.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the onlineversion of this article at the publisher's web site:

File S1. The Five Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire in Norway:Supplementary information about the translation procedure

Received 10 February 2012, accepted 01 January 2013

© 2013 The Authors.Scandinavian Journal of Psychology © 2013 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations.

260 I. Dundas et al. Scand J Psychol 54 (2013)