The Effects of Language and Culture on the Achievement of Turkish-speaking Students in British...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of The Effects of Language and Culture on the Achievement of Turkish-speaking Students in British...

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

This article was downloaded by: [Baykusoglu, Serkan]On: 16 October 2009Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 915843625]Publisher RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House,37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Muslim Minority AffairsPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713433220

The Effects of Language and Culture on the Achievement of Turkish-speakingStudents in British Schools: 1990s to 2004Serkan Baykusoglu

Online Publication Date: 01 September 2009

To cite this Article Baykusoglu, Serkan(2009)'The Effects of Language and Culture on the Achievement of Turkish-speaking Studentsin British Schools: 1990s to 2004',Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs,29:3,401 — 416

To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/13602000903166655

URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13602000903166655

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial orsystematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply ordistribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contentswill be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug dosesshould be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss,actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directlyor indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

The Effects of Language and Culture on theAchievement of Turkish-speaking Students inBritish Schools: 1990s to 2004

SERKAN BAYKUSOGLU

Abstract

In this paper, the achievement of Turkish-speaking students in Britain has been

evaluated by taking various factors into consideration. The Turkish community

resident in the United Kingdom dates back to the 1930s, when the first settlers

arrived and the current population of the Turkish community is estimated to be

around 150,000. However, Turkish immigrants and settlers have never been

counted as “Turkish” in either surveys or in the national census. This made

them invisible, and their diverse needs have not been taken into consideration. In

addition, as language ability, culture, gender and schooling had a great effect on

achievement, Turkish-speaking pupils struggled in the British educational

system. Although, the data relating to the existing Turkish community and its edu-

cational history in the United Kingdom are limited, a wide range of literature and

government papers have been accessed to support relevant findings. The result of

this extensive evaluation shows that Turkish-speaking pupils when compared

with other ethnic groups under-achieve in British schools.

Introduction

This paper surveys the Turkish-speaking pupils’ achievements in English schools.

It will begin by outlining the background of the Turkish community in the United

Kingdom followed by a review of the effect of factors such as language ability, ethnicity,

culture and schools on school achievement. It will then examine diversity and the range

of educational needs and gender differences against local and national demographic

data.

Finally, the paper will conclude with analysis of findings and suggestions for change

and improvement. Qualitative research methods have been used in the paper which

includes a survey of literature and government publications and opinion surveys.

However, there are very limited data available relating to Turkish-speaking pupils in

the UK, such as their actual number within the population as a whole, their educational,

social, and cultural background are not known. This is because of the invisibility of the

Turkish community which has resulted from their classification as “others” in surveys

and the national census.

Background of the Turkish Community in the UK

The Turkish community in the UK is very diverse and comprises several communities

mainly Turkish Cypriots, Turks from mainland Turkey and Turkish Kurds. There is a

Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, Vol. 29, No. 3, September 2009

ISSN 1360-2004 print/ISSN 1469-9591 online/09/030401-16 # 2009 Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs

DOI: 10.1080/13602000903166655

Downloaded By: [Baykusoglu, Serkan] At: 12:22 16 October 2009

broad term used to describe them as “Turkish Speakers”. The history of migration to the

United Kingdom differs for each of these groups. The first settlers who came to the

country were the Turkish Cypriots between 1930 and 1950. Given that they arrived

earlier than others, they are likely to be better established in many ways than the later

immigrants. They were from a rural agricultural background with little knowledge of

English and little formal education.

The second group of settlers arrived between 1950 and 1970 and they were also

Turkish Cypriots. The majority of these people had no formal education. Their

English language skills were as low as the first immigrants from Cyprus. Thus, the

characteristics of the Turkish-speaking people who came to Britain during these four

decades remained unchanged, i.e. uneducated without proper English skills. This is

an important issue to analyse, as there is a direct correlation between the pupils’

success at schools and their parents’ educational background. It is indicated that, a

great quantity of evidence based on major national studies with huge samples shows

that there is a very strong and positive relationship between the education of parents

and the measured intelligence, academic achievement, and extracurricular participation

of children in school or college.1 This point will be elaborated further in this paper. The

majority of Turkish and Kurdish people who chose Britain as their home country arrived

beginning in 1971 and settled in the UK under asylum and refugee status. In addition,

there are small numbers of settlers who came for educational purposes but became resi-

dent in the UK. The main reasons for immigration of the Turkish people to the UK were

political and economic.

At the time of the 2001 UK Census, almost 60,000 Turkish-born people were resident

in the UK. However, the total number of Turks including those born in Cyprus and those

born in the UK with Turkish roots is unknown.2 According to the Turkish Studies

Center (Stiftung Zentrum fur Turkeistudien) in Essen, there were 70,000 Turkish

people in Britain (Table 1).3

However, according to research carried out by Ayse Onal, “it is estimated that there

are 200,000 Turkish people including all the groups mentioned above living in the

UK”.4 On the other hand, the General Consulate for Turkey in London declares that

“the estimated number of Turkish nationals living in the UK (including students, au

pairs, illegal immigrants) is around 150,000”.5

TABLE 1. Turkish Population and Naturalised Turks in the EU (in thousands), 2002

Turkish origin Turkish nationality Turks EU naturalised

Countries Total Total Total %

Austria 200 120 80 40.0

Belgium 110 67 43 39.1

Denmark 53 39 14 26.4

France 370 196 174 47.0

Germany 2,642 1,912 730 27.6

The Netherlands 270 96 174 64.4

Sweden 37 14 23 62.2

United Kingdom 70 37 33 47.1

Other EU 20 19 1 5.0

Total EU 3,772 2,500 1,272 33.7

Source: Center for Studies on Turkey, University of Essen, “The European Turks: Gross Domestic

Product, Working Population, Entrepreneurs and Household Data”, 2003, p. 8.

402 Serkan Baykusoglu

Downloaded By: [Baykusoglu, Serkan] At: 12:22 16 October 2009

English as an Additional Language (EAL)

In this paper we will first focus on the EAL issue and its effects on achievement. Many

children enter British schools speaking one or more other languages. English is for them

an additional language, making them bilingual or even multi-lingual. Bilingualism is the

ability to communicate in more than one language whether at the same or different levels

in both languages. The term “bilingual” is used in Britain for the pupils who speak two

languages at home and at school. However, it does not mean that they are fluent and/or

competent and literate in both languages. A child may speak well in the mother tongue,

but this does not give us a clear picture of their linguistic experience with the language.

This speaking skill might be a result of a surface learning, without roots, other than a

deep structured learning. In this case, it is argued that the development in the mother

tongue can easily be interrupted.6 It is further argued that “if education in a foreign

language poses a threat to the development of the mother tongue, or leads to its

neglect, then the roots of the mother tongue will not be sufficiently nourished or they

may gradually be cut off altogether”.7

Children in Britain have to learn English if they are going to achieve in the British edu-

cation system. It is also important to facilitate the continued development of the first

language alongside English, because the first language, in other words mother tongue,

supports the development of additional languages: It has a crucial role in cognitive

and academic development and supports the acquisition of English. It is easier to transfer

a concept, skill and understanding gained in the first language than in an additional

language. As Baker and Jones conclude:

Experiments in the United States, Canada and Europe with language minority

children, who are allowed to use their minority language for part or much of

their elementary schooling, show that such children do not experience retardation

in school achievement or in majority language proficiency. Through their minority

language, they develop the ability to be relatively successful in the cognitively-

demanding and context-reduced classroom environment. This ability then trans-

fers to the majority language when that language is sufficiently well developed.8

From this point of view, it is not wrong to say that the fluency in the first language is as

important as the fluency in the second one. In other words, the more literate in the first

language, the more likely be literate in the second language. “As regards the more general

cognitive and social development of minority children, it can be argued that the acqui-

sition of literacy will be facilitated when the instruction links up with the linguistic

background of the learner”.9

There are also other factors which have an impact on the development of the learners’

language skills and on their ability to use these skills in their range of learning such as

previous schooling experience and knowledge in other languages besides levels of literacy

which I have discussed above. “Students’ language and academic development,

approaches to learning, and classroom behaviour are to a great extent the result of

previous educational experience”.10

Minorities with EAL

It is very helpful to look at the statistics of EAL pupils in the UK in order to analyse

the effect of EAL on achievement in the British education system. In 1996/1997 there

were approximately half a million pupils with EAL in maintained schools in the

Achievement of Turkish-speaking Students in British Schools 403

Downloaded By: [Baykusoglu, Serkan] At: 12:22 16 October 2009

country. This was equivalent to about 7.5% of all students including compulsory age and

above.11 According to the Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) report on research

carried out in 10 selected boroughs which were representing rural and urban context

and differentiation of pupil populations in 2002, Table 1 varied in different boroughs.

The range of Table 2 was 4–66% for ethnic minority pupils and 3–45% for EAL

pupils. Whilst there was 8% EAL pupils nationally, about 43% of pupils in inner

London have English as an additional language in 2001. In a small number of schools

in inner London over 80% of pupils have EAL.12 “The minority ethnic school popu-

lation (maintained schools) has grown by an estimated fifth to a third in number since

1997; in comparison, there has been a much smaller increase of 2.3% in the total

number of pupils in maintained schools during the same period”.13

Turkish-speaking pupils make up a significant portion of the overall number of pupils

with EAL. However, their position according to their achievement amongst the other

communities is remarkably poor. The following statistics and research results with the

factors on achievement will be analyzed in the conclusion. According to the census

carried out by the Inner London Education Authority (ILEA)14 in 1989, 1,356 children,

4.4% of the school age population, whose first language was Turkish, spoke English as a

second language. Turkish, after Bengali, was the second most spoken language in homes

where English was a second language.15

Virtually all the LEAs had significant numbers of refugees and asylum-seekers

. . . In addition to the EAL support needs of developing bilingual pupils, the fol-

lowing groups were identified as needing a particular focus owing to low levels

of achievement: Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Black Caribbean and Turkish pupils,

and Travellers, refugees and asylum-seekers more generally.16

Evidence of the achievement levels of the ethnic groups in Hackney schools is shown in

Table 3.

Turkish-speaking pupils’ achievements levels are amongst the lowest as can be seen in

Table 3. In addition, when each group is compared, it is clear that the Kurdish community

is the lowest amongst all the ethnic minority groups at Key Stage 4. This is followed by the

Turkish/Turkish Cypriots who are the second lowest achievers. There is a slight difference

at Key Stage 1 in 1998 as Turkish-speaking communities do better than the lowest achiev-

ing group, the Arabs. At this stage, the Kurdish community’s position remains the same,

again the most unsuccessful. Overall, the Turkish-speaking community is the lowest

achieving community compared to other communities. This situation did not change in

2003. “Ofsted analysed test scores of people who spoke English as an additional language,

who make up a tenth of students in English schools, and found that Somali, Kurdish and

Turkish speakers performed considerably worse than others”.17

The achievement level of the Turkish-speaking students in Islington schools in

2004 was not different either. According to the report which contains examination

TABLE 2. Minorities and EAL Pupils in the Local Educational Authority (Average)

Minority Pupils (%) EAL Pupils (%)

LEAs 30 26

Source: Ofsted, “Support for Minority Ethnic Achievement: Continuing Professional Development”,

available online at http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/content/download/1316/9632/file/supportforminority

ethnicachievementcontinuingprofessionaldevelopment(PDF format).pdf: 2002, Vol. 5, p. 4.

404 Serkan Baykusoglu

Downloaded By: [Baykusoglu, Serkan] At: 12:22 16 October 2009

of many major reports published by the Department for Education and Skills (DfES),

Ofsted and so on since 2001, the Turkish-speaking students at Key Stage 1 Writing,

Reading and Maths achieved the lowest scores of all the other communities. Although

there was a slight improvement in Maths, which was about 3%, their performance in

Writing and Reading went down from 3 to over 10%. Turkish-speaking students in

these subjects were the only ethnic group with a decrease in their development

from 2003 to 2004. When we look at the GCSE, 5 A� to C, results by gender in

the same year, Turkish-speaking boys were the second poorest achievers after Black

Caribbean. In addition, Turkish-speaking girls were the lowest achieving group.18

In post-compulsory education, Turkish-speaking students’ achievements did not differ

either when it was compared with compulsory education. According to the Ofsted

Enfield area inspection, Turkish pupils with other minority groups namely Black Carib-

bean, Black African, Black other and Greek pupils achieved least well at GCE A Level.19

As a result of “. . . that 36% of British Muslims are leaving school with no qualifications,

while a fifth of 16–24-year-old Muslims in Britain are unemployed”.20 The research

carried out by Colin Alston from Hackney LEA showed that the higher number of

passes in GCSEs the pupils from ethnic minorities achieved, the higher percentage of

the pupils continued the post-16 education (Table 4).

According to Table 4, whilst 63% of Turkish-speaking students who could not achieve

any A� to C grades in GCSEs continued their studying in post-16 education, this

increased to 95% for those who achieved at least three A� to C passes in GCSEs.

When they reached the minimum seven good passes, almost all Turkish-speaking

pupils stayed on post-compulsory education.

In contrast, Turkish-speaking pupils whether they were trained or not most likely went

into employment. Table 5 shows in Hackney, the percentage of students going into employ-

ment among the trained Turkish-speaking pupils, was very low and limited to boys only.

TABLE 3. Comparison of Achievement Levels of Turkish-speaking Pupils with Other Ethnic Groups

Key (%) Key (%) Key (%)

Stage 1 Stage 1 Stage 4

Ethnic group 1997 1998 1997

African 71 77 33

Arab 89 40 43

Bangladeshi 51 63 41

Caribbean 66 73 22

Chinese 58 53 69

Eng/Scot/Welsh 65 72 30

Greek/Cypriot 33 55 33

Indian 63 60 35

Irish 60 64 47

Jewish 93 91 –

Kurdish 29 41 7

Pakistani 63 77 39

Turkish/Cypriot 39 41 17

Vietnamese 58 72 42

Other 65 73 43

Source: Map Hackney-Interactive Mapping Application (the Turkish Cypriot community living in

Hackney), 2000, p. 9.

Achievement of Turkish-speaking Students in British Schools 405

Downloaded By: [Baykusoglu, Serkan] At: 12:22 16 October 2009

The Role of Family in Student Achievement

It is generally accepted that if pupils are to raise their achievement they will need the full

support of their parents. Parental involvement takes various forms such as good parent-

ing at home, including the provision of a suitable environment for learning after school,

intellectual stimulation, discussion with the child, good models of constructive social and

educational values as well as high ambitions relating to personal performance. This list

might be extended as parents may also be in a position to have contact with schools to

share information about the development of their children. They may require further

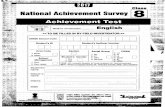

support, and become involved in the schoolwork and/or governing. Figure 1 illustrates

the key players and potential process in shaping pupil achievement. It is clear that family

and parental characteristics including family structure and income as well as other

factors have an impact on educational achievement and personal adjustment.

For example, young people whose parents were from higher professional backgrounds

were most likely to achieve 5þGCSEs A� to C (81% compared with 32% those from

routine occupational backgrounds) in the UK.21 From this point of view, in the first

part of this paper, we recognized the Turkish communities’ educational background

TABLE 4. GCSE Achievements and Post-16 Destinations of Pupils from Different Ethnic Backgrounds

(Data for Year 11, 2000)

Main ethnic groups in

Hackney

Percentages staying-on in post-16 education

No A� –C

Passes

1–2.5% A� –C

Passes

3–6.5% A� –C

Passes

7–13% A� –C

Passes

African 73 83 92 91

Bangladeshi 71 82 90 97

Caribbean 68 78 86 98

Eng/Scot/Welsh 38 53 64 90

Indian 59 55 74 100

Turkish 63 80 95 100�

� Indicates percentages based on raw numbers less than 10.

Source: Colin Alston, “Making the Connexions: New Evidence on the Links between Pupils’ GCSE

Results and Their Post-16 Destinations”, by, Hackney LEA, p. 34, available online at: http://www.

cemcentre.org/EB2003/Colin%20Alston%20COLUMNS%20WITHOUT%20SHADING.doc

TABLE 5. Pupils with Destinations in Employment (with and without Training) and Government-

Sponsored Training, Analysed By Ethnic Group and Gender

Employment with

training %

Employment with

no training %

Government

sponsored training %

Girls Boys Girls Boys Girls Boys

African 0 4� 13� 0 5� 0

Bangladeshi 5� 0 13� 0 10� 0

Caribbean 5� 9� 13� 0 35� 47�

Eng/ Scot/ Welsh 43� 52 33� 60� 20� 20�

Indian 14� 4� 0 20� 20� 7�

Turkish/Cypriot 0 4� 0 0 0 0

�Percentages based on raw numbers of pupils less than 10.

Source: Colin Alston, “Making the Connexions: New Evidence on the Links between Pupils’ GCSE

Results and Their Post-16 Destinations”, by Hackney LEA, p. 38.

406 Serkan Baykusoglu

Downloaded By: [Baykusoglu, Serkan] At: 12:22 16 October 2009

and the impact of parental support on achievement. There is no doubt that the immigra-

tion of people overwhelmingly affects the need for literacy education in the country of

settlement; and so opportunities for literacy learning should be provided to new immi-

grants. However, “the role of parents in helping children (re)discover the principles of

literacy is crucial”22 which is mainly the parents’ responsibility to help their children

acquire literacy in their mother tongue as well as in the second language at home at

an early stage of learning.

In contrast, many Turkish-speaking parents are unfamiliar with the British education

system. They therefore have little understanding of choosing schools, Key stages, exclu-

sions and special needs. Lack of English language also means that, they are unable to

keep track of their children’s progress through school reports and are unable to ade-

quately help or encourage their children with school work.23

In addition, it is argued in a report that many Turkish-speaking families cannot

provide support for their children with home work tasks. This is because of difficulties

with English and lack of understanding of the education system.24 This problem is

enlarged by adding Muslim parents’ low status in the society, limited ambition and

low income.25 According to another research carried out, one of the factors on pupils’

attainment was the ethnic background.26 The children from Turkish backgrounds

were one of the lowest achieving groups in terms of reading attainment. They obtained

the lower scores in reading than those who were of English background families. This

was same for the Maths attainment.

Influence of School and other Factors on Achievement

We have discussed the effect of lack of English fluency, of parental support and insuffi-

cient support in the mother tongue by examining the impact of ethnic background issues

on achievement in the preceding parts of this paper. One critical aspect must be

FIGURE 1. The Impact of Family and Community Resources on Student Outcome.Source: T. Nechyba, P. McEwan, and D. Older-Aguilar, “The Impact of Family and Community Resource

on Student Outcomes: An Assessment of the International Literature with Implications for New Zealand;

1999” available online at: http://www.minedu.govt.nz/index.cfm?layout¼document&documentid¼5593

&CFID¼6735490&CFTOKEN¼69775095

Achievement of Turkish-speaking Students in British Schools 407

Downloaded By: [Baykusoglu, Serkan] At: 12:22 16 October 2009

addressed however, which is the role played by the government. Is each ethnic group

classified to easily meet their specific needs? What about the schools? Do they have

any diversity goals which recognise the needs of the ethnic communities? Are there

enough qualified teachers and support staff, for example assistants, who are trained in

how to deal with EAL pupils? Are there any policies relating to teaching in the

“mother tongue”? These questions need to be asked in order to find out the effect of

schools and of their policies on achievement of ethnic groups in the UK.

EAL has been a concern for successive governments since 1966; that was the first year

in which the government began funding for specialist staff to meet the needs of EAL

pupils. The aim was to help pupils with “New Commonwealth” backgrounds.

Although, pupils from other countries, including the Turkish-speaking, had already

established their life in Britain, they were not counted as EAL pupils. Therefore,

LEAs were not given enough funding to support all ethnic minorities. It was not until

1993 that this funding was extended for all EAL pupils.27 In 1998, the Ethnic Minorities

Achievement Grant (EMAG), was introduced to provide funds to support both EAL

pupils and those from minority ethnic groups who have English as a mother tongue

but are nationally recognised as underachievers. In the academic year, 2004–2005,

social and economic austerity has been taken into account by factoring in the number

of pupils receiving free school meals. Some percentage of funding could also be used

for a centralised language service. The Department for Education and Skills developed

the “Aiming High” strategy to raise the achievement of ethnic minorities in 2003. This

was the first national strategy to tackle underachievement amongst minority ethnic

pupils. The strategy focuses mainstream programmes and targeted activity on narrowing

the achievement gaps between all pupils. The aim is to ensure that all schools meet the

needs of individual pupils by recognising and valuing their diversity and by challenging

underachievement.

Accordingly, some schools set different strategies to raise their ethnic minority pupils’

achievement. For example, some Turkish-speaking students at White Hart Lane School

in Haringey begin year 7 science lessons in Turkish. This will continue with English

teaching alongside the lessons in Turkish until the students reach year 11. Then

Science GCSEs will be taken in English. This policy is now being extended to Somali

students who will be able to study the subject in their own language, Somali.28

Plans for the “Cold Spots”

Following the Aim High strategy set by the government, an integration plan for London

North Aim Higher partnership was made for the period from 2004 to 2006. This

included almost all types of educational establishments such as schools, colleges,

higher education institutions as well as authorities like local London Skills Councils,

in order to widen the participation of disadvantaged young people in higher education.

The program has mainly focused on “hard to reach” target groups in twenty venues

named “cold spots”:

Consultation highlighted particular needs among young offenders, teenage

parents-fathers as well as mothers . . ., parents of low-achieving young people,

and particular community groups, for instance those of Turkish or African

Caribbean origin.29

However, it is generally argued that the governments’ policies for EAL pupils have not

been satisfactory. For example, there is no nationally recognised qualification in teaching

408 Serkan Baykusoglu

Downloaded By: [Baykusoglu, Serkan] At: 12:22 16 October 2009

EAL in England whilst according to DfES the great majority of teachers across the

country may now expect to work with minority ethnic pupils at some point in their

career.30 The same report indicates the finding of 2002 research that many teachers in

mainly white schools are critical of the poor quality of their initial training with regard

to teaching minority ethnic pupils, and are aware that this now needs urgent attention

in their continuing professional development. In 2001, 39 local education authorities

which have a higher proportion of ethnic minority students were inspected by

Ofsted.31 Its report concluded that many schools and LEAs among those surveyed,

were not nearly as effective as they needed to be in tackling the under-achievement of

many people from minority ethnic groups. In many LEAs there was uncertainty about

how to improve attainment. There is insufficient awareness amongst staff of principles

of good practice for helping pupils to acquire and use English as an additional language.

It is therefore the schools that have a different approach to LEA pupils; whilst one school

sets its own policy and attempts to improve attainment of the pupils, the other may have

no policy at all.

The National Association for Language Development in the Curriculum (NALDIC)

provides a voice for EAL specialists and discusses the complexity of assessing pupils

learning EAL. The English criteria are designed for monolinguals not for bilinguals.

They do not reflect the stages of language acquisition particular to EAL pupils.32

Joanna McPake from Stirling University argues that “schools do not always appreciate

the value of maintaining and developing language skills other than English”.33 Further-

more, a report found that support for more advanced learners is often inadequate and

this can lead to underachievement.34 Many schools also lack experience of EAL

pupils, and this can result in low expectations and their being put into inappropriate

ability groups. Low expectations are a major handicap: low expectations for success

leads to low motivation, resulting in poor performance. It was indicated that teachers

were greatly influenced by the social background of the child in making streaming

decisions even for children with comparable levels of general ability.35

Lack of Statistics

When it comes to discussing the Turkish-speaking pupils, it is argued that although

Turkish-speaking pupils are heavily concentrated in many London boroughs, there are

no accurate figures of their population available. Furthermore, estimates of their

numbers vary.36 Thus, the local governments failed to address these groups’ specific

needs. Because their numbers are not significant nationally and they are not classified

in the census, these groups tend to become invisible, and “. . . the invisibility of the

Turks means that their particular problems are not noticed or grasped by teaching

staff”.37 The chart below illustrates the fact that Turkish-speaking pupils are not

grouped by general background nationally: they are classified as “other” in 2001 census.

Teacher Training Agency surveys of newly qualified teachers (NQT) show that quite a

high number of NQTs believe they have not really been trained to teach pupils with

different ethnic backgrounds and those with English as an additional language

(Figure 2).38 This is a serious issue, as pupils with EAL certainly need professional edu-

cators who are specialised in dealing with ethnic minority and special educational needs

pupils. For example, all the pupils in a classroom may be Turkish speakers of some level

but it is certain that they are not all the same. Even in a community language class there is

a huge level of ethnic and linguistic diversity which needs to be approached sensitively.

On the other hand, there is an untested assumption that native-speakers are inherently

Achievement of Turkish-speaking Students in British Schools 409

Downloaded By: [Baykusoglu, Serkan] At: 12:22 16 October 2009

better teachers: so it could be argued that Turkish teachers are highly literate in Turkish

so they can easily deal with Turkish-speaking students. They may all be able to under-

stand the spoken word and teach Turkish. However, their literacy levels in Turkish

can vary from excellent to nonexistent and this is to be considered.

Impact of Socio-Economic Status

One of the factors on achievement is assessing the number of people who are eligible for

free school meals in mainstream schools in the UK. Many studies have been carried out

in order to determine the direct correlation between free school meals (FSM) and

achievement. For example, a bulletin published by National Statistics provides the stat-

istical relationship between the eligibility for FSM and academic achievement. It is

argued in the bulletin that “there is a strong link between achievement and the level

of entitlement to free school meals: as the level of FSM entitlement increases, the

level of achievement decreases”.40 The percentages of 7-year-olds eligible for free

school meals illustrates the level of deprivation in the Turkish-speaking communities

(see Table 6).

Table 6 shows that the Turkish-speaking community has the second highest percen-

tage of 7-year-olds who are eligible for free school meals. This is evidence that FSM is

TABLE 6. Percentages of Largest Ethnic Groups of 7-year-olds Eligible for Free School Meals in Hackney

Ethnic group Percent eligible

Eng/Scots/Welsh 53

African 54

Indian 56

Caribbean 64

Turkish/Turkish Cypriot 77

Bangladeshi 82

All Groups 61

Source: Map Hackney-Interactive Mapping Application (the Turkish Cypriot community living in

Hackney), 2000, p. 10.

FIGURE 2. Ethnicity in England and Wales.Source: The Guardian, Tuesday November 30, 2004.

410 Serkan Baykusoglu

Downloaded By: [Baykusoglu, Serkan] At: 12:22 16 October 2009

strongly associated with low attainment among the children of Turkish communities’.

Achievements were very low, as shown in Table 3, in the Key Stage 1 national test at

the age of 7.

Housing is another concern as regards achievement. Turkish-speaking families are

often found to be living in overcrowded conditions. This is partly due to the fact that tra-

ditionally, families from Turkey live in extended family groups. They continue to live in

the UK much the same way as they lived in Turkey. New comers also stay with their close

relatives until they are provided with their own accommodation. It appears that the chil-

dren of those families have been adversely affected by overcrowding and unsuitable

housing. The children usually shared their rooms with their younger sisters and brothers

who disturbed them. Lack of space at home with unsuitable conditions badly affected the

children’s achievement, as stated by many Turkish parents. This is because “Turkish

families are often not suitably re-housed. Many are housed in temporary accommo-

dation in which they continue to live for two or three years”41 such as hostels which

offer a single room with other facilities shared.

Gender also has an effect on achievement. In most cases boys of the same background

as girls under-perform at all Key-Stages. However, it is argued that improvement in

female achievement is not shared by girls from low socio-economic backgrounds and

it may not be apparent in some subjects.42 Attitudes towards gender at home, is an

issue for Turkish-speaking pupils. Boys are traditionally allowed more freedom than

girls who are strictly controlled by parents. This may also cause emotional problems.

On the other hand, girls are encouraged to take up jobs which are considered by their

parents to be “girls jobs” or “more suitable”; for example secretarial, hairdressing or

teaching occupations. In this case, girls have limited options to choose from for their

future career, whereas boys have more freedom.

Inclusion and Diversity

Inclusion is a process which seeks to enable pupils to participate in the life and work of

mainstream institutions to the best of their abilities, whatever their needs. Inclusive edu-

cation refers to all types of schools that should be open to all children, and means that all

children have right to learn and participate. The schools should be able to accommodate

the needs of all pupils and ensure that they are included in all aspects of school life. It also

means identifying any barriers within and around the school that affect learning and par-

ticipation and removing those barriers.

A central argument of the inclusive education idea was that students with disabilities

ought to be educated in the same way as other pupils. However, it has been realised that

not only those pupils with disabilities but also those who have various needs should par-

ticipate equally in education. Because, “inclusive education is not about identifying an

“excluded group” and fixing their situation so that they are, in appearance at least,

less excluded”.43

There are different theories on diversity but not all of them fully support an inclusive

approach in education. According to Ryan, a conservative idea is the least helpful in

inclusiveness. Conservative emphasis on cohesion, nationhood, common culture and

the market translate into the same kind of practices in schools. As an example, it is

expressed that market-conscious schools tend to devote more of their time and attention

to academically successful students, in other words talented and gifted, at the expense of

less gifted, sometimes ethnically different students.44

Achievement of Turkish-speaking Students in British Schools 411

Downloaded By: [Baykusoglu, Serkan] At: 12:22 16 October 2009

In contrast, liberal/pluralist approaches to diversity are more respected than the conser-

vative’s one. The differences in groups including non-Anglo ones as well as their cultures

in school activities are valued by the liberals. On the other hand, critical approaches defend

comprehensive types of inclusive practice. They openly campaign for inclusion that “. . .

can only be achieved when people recognise, understand and change the structures that

constrain and exclude individuals and groups from the privileges that others enjoy”.45

Although inclusion policy has been on the government’s agenda for years, a study on

schools showed that residents of disadvantaged urban areas were poorly served by the

education system. The report46 highlighting a number of key findings indicated that:

. Particularly disadvantaged children came from economically deprived com-

munities.

. Curriculum planning does not address the needs of children from disadvan-

taged backgrounds and does not focus sufficiently on raising achievement.

. Underachievement is apparent at an early stage. Many pupils never recover

from early failure in basic skills.

. Arrangements for learning support are poor. Schools lack expertise in initial

assessment.

. Atmosphere in many classrooms is good natured but neither challenges the

pupils nor secures their participation.

In addition, it was declared by the Department of Education and Science in 1991 that

children of below average ability and attainments are badly served by the educational

system. The less academically able continue to suffer disproportionately from whatever

problems affect the education system. Whilst excluding children was a normal policy of

schools until the last decade, this began to be seriously questioned as excluding pupils

from the mainstream because of disability or learning difficulty is now seen as negative

discrimination and as a major human rights issue. Although attitudes to inclusion of chil-

dren with special needs into ordinary schools with support are changing slowly in a posi-

tive way, there is still resistance in Britain to inclusion for all pupils. It is argued that the

strong relationship between educational achievement and social background is taken for

granted but is little understood and rarely discussed.47

Special educational needs have been conceptualised in terms of a dynamic interaction

between the individual child and the various environments in which the child is living

and learning. The nature and the quality of that interaction are yet to be understood

properly in order to benefit children. According to Dyson, the ways in which schools

can create or complicate learning difficulties and how schools might prevent such

difficulties is being examined. However, it has focused on the reform of schools, its cur-

riculum and organisation without considering the wider social and economic context

within which schools must operate.

Critical Findings

In this paper we have examined the relationship between low achievement and pupil

characteristics (gender, ethnic origin, free school meals, whether English is the pupil’s

first language, and whether he or she has special educational needs—that is to say ident-

ified learning difficulties). This was achieved through considering several factors namely:

“bilingualism, parenting and related factors within the educational experience which

have an impact on achievement”.

412 Serkan Baykusoglu

Downloaded By: [Baykusoglu, Serkan] At: 12:22 16 October 2009

The findings clearly indicate that Turkish-speaking pupils underachieve in British

schools when compared with other minority ethnic groups. Whilst the Turkish commu-

nity has a migration history spanning more than 70 years in the UK, it was mainly the

lack of education and skills on the part of the parents which affected their children’s

attainment in schools.

The absence of educational experience for many Turkish parents and lack of language

support (including in their mother tongue) had a considerable impact on the students

learning outcome. The learners could not find adequate opportunities to develop lit-

eracy in their mother tongue, Turkish, starting from an early age. It was true that

they were bilingual and able to communicate in both languages, but this was at a

lower level of fluency and accuracy. Therefore, Turkish-speaking pupils struggled in

learning and in developing English at an appropriate level allowing them to proceed

further in their education without a support for structured development in Turkish.

Most parents could not provide any help to their children at home and the children

were left without guidance in completing their homework. The parents neither knew

the British education system nor could involve themselves in any school work. Thus,

it was really hard to talk about the effective link between the parents and schools as

they were not even able to check their children’s school performance by contacting

the schools.

In addition to the role of family in achievement, there was no government support for

EAL pupils, except the Turkish Cypriots who were regarded as citizens of a common-

wealth country, until 1993. Although funding became available after this year,

Turkish-speaking pupils were mostly categorised as “others” in census lists. They were

counted as monolingual pupils at schools. Turkish-speaking pupils (with others from

all minority groups) were considered as natural speakers of English. Only one school

in London recognised its Turkish-speaking pupils’ needs, and so began teaching in

Turkish. Their ethnic background was not listed and their diverse needs could not be

measured properly. Though they are the highest affected ethnic group among other

minorities, their situation has not changed so far in most schools.

Conclusion

Inclusiveness means that everyone has different abilities and needs but all should be sup-

ported and given opportunities to actively participate and learn at schools. However,

until recently many schools in Britain have failed in sorting out the under-achievement

problem of ethnic minority pupils in the country. Most schools had no policy on how to

deal with them either. Furthermore, newly qualified teachers believe that they did not

acquire the skills during their teacher training programmes to teach ethnic minority

pupils; their initial training was therefore poor. Other factors also had negative affect

on Turkish-speaking pupils’ achievement, namely belonging to a different cultural back-

ground, living mostly in unsuitable housing conditions, receiving different treatment

from the parents depending on gender, and receiving free school meals, which was

also an indication of their parents’ financial circumstances.

Based on our findings, the suggestions for improving the situation for Turkish-speak-

ing pupils in the UK include the following:

. A national survey should be carried out to find out how many Turkish-speak-

ing pupils live in the UK including their educational background and

language skills.

Achievement of Turkish-speaking Students in British Schools 413

Downloaded By: [Baykusoglu, Serkan] At: 12:22 16 October 2009

. All Turkish-speaking pupils’ parents should be given appropriate literacy

training considering their language proficiency in both languages. For train-

ing in Turkish, a project should be prepared in conjunction with the Turkish

educational authorities in Turkey.

. Teachers and support staff should be trained to support pupils with English

as an Additional Language.

. The pupils from different minorities should be given bilingual language train-

ing starting from early age.

. Pupils’ diverse needs should be considered in preparing learning strategies.

. The links should be strengthened between Turkish parents and the schools,

and the parents should be encouraged to become involved in activities at

schools.

. The parents should regularly be provided with their students’ learning pro-

gress by the schools.

. All the ethnic minorities should be encouraged to get involve in the govern-

ment’s Ethnic Minority Achievement Project.

. Schools with Turkish-speaking pupils should employ more Turkish-speaking

teachers and support staff.

. Teaching in Turkish as well as in English should be encouraged at schools

where the Turkish-speaking pupils are attending in large numbers.

NOTES

1. W. B. Fetters, “National Longitudinal Study of the High School Class of 1972: Student Question-

naire and Test Results by Sex, High School Program, Ethnic Category, and Father’s Education”.

U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, National Centre for Education Statistics,

Washington, DC, 1975.

2. 2001 UK Census.

3. Center for Studies on Turkey, University of Essen, “The European Turks: Gross Domestic Product,

Working Population, Entrepreneurs and Household Data”, 2003, p. 8.

4. Ayse Onal, “Ingiltere’deki Turkiyeli Topluluk Ustune Bir Calısma” [Research about the Turkish

Community in the UK], available online at: http://www.gazetem.net/bellekyazi.asp?yaziid¼67 2

June 2003.

5. www.turkishconsulate.org.uk/en/commun.htm. Retrieved on 09/07/2007.

6. Please see Appendix A for the illustration about the importance of sustaining all the child’s language.

7. Tove Skutnabb-Kangas, Bilingualism or Not: The Education of Minorities, translated by Lars Malmberg

and David Crane, Clevendon, Avon, England: Multilingual Matters, 1981, p. 378.

8. Colin Baker and Sylvia Prys Jones, eds, Encyclopedia of Bilingualism and Bilingual Education,

Clevedon, USA: Multilingual Matters, 1988.

9. Ludo Verhoeven, “Literacy and Schooling in a Multilingual Society”, in Effective Early Education:

Cross-Cultural Prospectives, eds Lotty Eldering and Paul Leseman, New York, London: Falmer

Press, 1999, pp. 213–235. Please see also J. Cummins, Negotiating Identities: Education for Empower-

ment in a Diverse Society, Los Angles, CA: California Association for Bilingual Education, 2001;

Cummins represents bilingual learners’ ability to transfer knowledge and skills between languages

as a “dual iceberg” in which the surface features of each language, for example pronunciation, and

syntax are very different but are being processed by a single system. Therefore, content and skills

learned through one language will transfer to another.

10. Maria Estela Brisk, Bilingual Education: From Compensatory to Quality Education, Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988.

11. Please see Statistical Bulletin Number 3/99: “Ethnic Minority Pupils for Whom English is an

Additional Language”, 1996/7, p. 3, available online at: http://www.dfes.gov.uk/rsgateway/DB/

SBU/b000050/10492e.pdf

12. Ofsted, Local education authority support for schools in inner-London, available online at: http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/publications/docs/1261.pdf 2001, 21, p. 8

414 Serkan Baykusoglu

Downloaded By: [Baykusoglu, Serkan] At: 12:22 16 October 2009

13. DfES, “Ethnicity and Education: The Evidence on Minority Ethnic Peoples”, 2005. available online

at: http://www.dcsf.gov.uk/research/data/uploadfiles/RTP01-05.pdf

14. ILEA was abolished in 1990 and replaced by 13 separate local education authorities (LEAs).

15. Map Hackney-Interactive Mapping Application (The Turkish Cypriot Community Living in

Hackney), 2000, p. 3, available online at: http://www.map.hackney.gov.uk/Mapgallery/Ethnicity%

20Documents/Turkish%20Cypriot.doc

16. Ofsted, “Support for Minority Ethnic Achievement: Continuing Professional Development”,

October, HMI 459, 2002, p. 4, available online at: http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/publications/index.

cfm?fuseaction¼pubs.displayfile&id¼2838&type¼pdf

17. TES, 21 March 2003.

18. Islington children’s services, Proposal for development, moving from equalities standard 2 to 3; 2004,

available online at: http://www.islington.gov.uk/DownloadableDocuments/CommunityandLiving/

Pdf/equalitydocs/childrens_services_deap_05_06.PDF

19. OFSTED, Enfield 14 to 19 Area Inspection, available online at: http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/reports/

servicereports/536.htm, 2003.

20. Madeleine Bunting, “Young, Muslim and British”, The Guardian, Tuesday, November 30, 2004.

21. DfES, “Youth Cohort Study: The Activities and Experiences of 16 year olds: England and Wales,

2002”, p. 12, available online at: http://www.dfes.gov.uk/rsgateway/DB/SFR/s000382/SFRtemplateweb.doc

22. Ludo Verhoeven, “Literacy and Schooling in a Multilingual Society”, in Effective Early Education:

Cross-Cultural Prospectives, eds Lotty Eldering and Paul Leseman, New York, London: Falmer

Press, 1999, pp. 213–235, p. 215.

23. Map Hackney-Interactive Mapping Application, op. cit., p. 8.

24. Pinar Enneli, Tariq Modood and Harriet Bradley, Young Turks and Kurds, A Set of “invisible” disad-

vantaged groups, University of Bristol, York, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2005.

25. Humayun Ansari, The Infidel Within: The History of Muslims in Britain, 1800 to the Present, London:

Hurst and Co., 2004, p. 303.

26. P. Mortimore, P. Sammons, L. Stoll, D and R. Ecob, School Matters: The Junior Years, Somerset:

Open Books, 1988.

27. Background to EAL funding & the Ethnic Minority Achievement Grant (EMAG), available online at:

http://www.literacytrust.org.uk/Database/Section.html

28. A speech on urban education by the schools minister Stephen Twigg to Fabian Society, 9 February

2005, Guardian School News, available online at: http://education.guardian.co.uk/schools/story/0,,1409071,00.html

29. London Aim Higher, Integration Plan for London North Aim Higher Partnership 2004–2005, p. 12,

available online at: www.londonnorthaimhigher.org.uk/documents/integration/Final%20Plan%

201.6.04.pdf

30. DfES, Aiming High: Understanding the Educational Needs of Minority Ethnic Pupils in Mainly

White Schools, 2004.

31. Ofsted, Managing support for the attainment of pupils from minority ethnic groups, 2001, available

online at: http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/publications/index.cfm?fuseaction¼pubs.

displayfile&id¼3441&type¼pdf

32. The National Association for Language Development in the Curriculum (NALDIC), (26 January,

2006), available online at: http://www.naldic.org.uk/ITTSEAL2/teaching/Assessment.cfm

33. Joanna McPake, Stirling University, BBC News: “Diversity of Languages is Hailed”, 22 September

2005, available online at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/education/4272820.stm

34. Ofsted, “Islington Green School Inspection Report”, available online at: http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/reports/100/100454.pdf, 03 February 2003

35. J. W. B. Douglas, The Home and the School, London: McGibbon and Kee, 1964.

36. Aydin Mehmet, Turkish-Speaking Communities and Education: no delight, London: Fatal Publications,

2001.

37. Pinar Enneli, Tariq Modood and Harriet Bradley, Young Turks and Kurds, op. cit., p. 18.

38. See online at: http://www.multiverse.ac.uk/aboutUs.aspx?menuId¼649

39. National Statistics, Academic Achievement and Entitlement to Free School Meals, 2004, available

online at: http://www.wales.gov.uk/keypubstatisticsforwales/content/publication/schools-teach/

2005/sb15-2005/sb15-2005.pdf

40. Ibid., p. 5; and Department of Education and Science, 1991, p. 2, available online at: http://www.

ofsted.gov.uk/publications/index.cfm?fuseaction¼pubs.displayfile&id¼3441&type¼pdf

Achievement of Turkish-speaking Students in British Schools 415

Downloaded By: [Baykusoglu, Serkan] At: 12:22 16 October 2009

41. P. Murphy and J. Elwood, “Gendered experiences, Choices and Achievement: Exploring the Links”,

International Journal of Inclusive Education, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1988, pp. 95–118.

42. Felicity Armstrong and Michele Moore, Action Research for Inclusive Education: Changing Places,

Changing Practices, Changing Minds, New York: RoutledgeFalmer, 2004, pp. 11–12.

43. James Ryan, Leading Diverse Schools, Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publisher,

2003.

44. Ibid., p. 41.

45. Ofsted, “Access and Achievement in Urban Education”, London HMSO, 1993.

46. A. Dyson, “Social and educational disadvantage: reconnecting special needs education”, British

Journal of Special Education (BJSEN), Vol. 24, No. 4, 1997, pp. 152–157.

416 Serkan Baykusoglu

Downloaded By: [Baykusoglu, Serkan] At: 12:22 16 October 2009