The determinants of the choice between public and private production of a publicly funded service

Transcript of The determinants of the choice between public and private production of a publicly funded service

Public Choice 54:211-230 (1987) © Martinus NijhoffPublishers, Dordrecht - Printed in the Netherlands

The determinants of the choice between public and private production of a publicly funded service*

ROBERT A. McGUIRE Crown College, University o f California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064 and Department o f Economics, Ball State University, Muncie, I N 47306

ROBERT L. O H S F E L D T Center f o r Health Services Administration, Arizona State University, Tempe, A Z 85287

T. N O R M A N VAN COTT Department o f Economics, Ball State University, Muncie, IN47306

Abstract

The public choice literature contains little formal analysis of the bureaucratic choice of production modes - public or private - of publicly funded services. An important question

to be addressed is why some governmental bodies choose to provide a publicly funded service

with publicly owned and operated production units whereas other governmental bodies con-

tract with private firms to provide the same publicly funded service. This paper is the first formal attempt to remedy this gap in the literature. We develop a theoretical explanation of the government decision maker's choice between public and private production modes based on utility maximizing behavior. We then examine empirically this choice employing logit

analysis. The empirical results, which include several tests for robustness, confirm our theoretical explanation. The results are significant and suggest that non-monetary constraints are an important factor affecting this choice of production modes and that monetary constraints are less influential.

A large literature has developed over the last two decades comparing the performance of public sector (or more generally, not-for-profit) economic activity with that of the private sector. Industries investigated in this literature include airline service, electric and water utilities, railroads, refuse collection, and school bus transportation. The hypothesis underlying these investigations is that private firms are more efficient by market standards because the rewards and costs of operation reside with the owners of resources involved in production to a greater degree than is the case for

*The authors would like especially to acknowledge the comments and suggestions of Louis De Alessi. Additional comments were provided by Cecil E. Bohanon, Thomas E. Borcherding, James S. Cunningham, Philip R.P. Coelho~ James V. Koch, Walker A. Pollard, and George J. Stigler. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the 1983 Western Economic Associa- tion Meeting in Seattle and the 1985 Public Choice Society Meeting in New Orleans.

212

public firms. The empirical results generally confirm the hypothesis that pri- vate economic activity is less costly than public economic activity, although the differential narrows when public firms are subject to market competi- tion or when property rights within private firms are attenuated.1

Curiously, this literature only recently has begun to offer conjectures con- cerning the determinants of the choice between public productio~ of ser- vices and provision of the same services via government contracting with private firms. Failing to explain the persistence of public production (rather than government contracting with private firms) in the face of extensive evi- dence about the superiority of private sector performance is an important omission in the literature. Note that the issue raised is not the same as ex- plaining the level of public expenditures, because the services in this case are publicly funded regardless of who produces them. Rather, the question is why some governmental bodies choose to provide a publicly funded service with publicly owned and operated production units; whereas other govern- mental bodies choose to provide the same service through contracts with pri- vate firms. To our knowledge, there is no commonly accepted theoretical explanation of this question. And no one has empirically investigated the issue. The only previous comments on this issue have occured in a broader context. 2

To fill the gap, this paper presents a theoretical explanation of a govern- ment decision maker's choice between public production and private con- tracting. It then examines the hypothesis empirically, employing regression analysis, within the context of school bus transportation in the United States. Because the choice of the production mode for school transportation is in large measure a discretionary decision of the educational bureaucracy, the theoretical construct for the investigation is the emerging theory of bureaucratic behavior. 3 This theory views bureaucratic decisions as ema- nating from personal utility maximization on the part of individual bureau- crats. For the time period studied, the 1979-80 academic year, approxima- tely 70 percent of the school buses in the country were publicly owned and operated and the remaining 30 percent were owned and operated by private contractors - all bus transportation was publicly funded. 4

The econometric results of this study suggest that nonmonetary con- straints on the choices of education bureaucrats are not only an important determinant of the production mode, but that they dominate monetary con- straints. The findings provide evidence that these nonmonetary constraints operate through input markets and constituent preferences for particular production modes. Specifically, our regression coefficients of virtually all proxies for different nonmonetary costs of bureaucrats' choices are highly significant and in the right direction; whereas the coefficient of monetary costs is only sometimes significant. The results offer support for the hypo- thesis that the bureacrats behave as utility maximizers.

213

1. Analytical framework

It was not until recently that economists sought to explain why one observes both private and public production of publicly provided goods and services (Baumol, 1983; Borcherding, 1982; and De Alessi, 1982). This limited litera- ture has offered several hypotheses concerning the phenomenon without providing any empirical verification beyond the anecdotal level. Borcher- ding (1982) and De Alessi (1982) argue along similar lines, asserting that public production is more likely to be observed across a spectrum of indus- tries where the costs of monitoring the performance of private contractors are greater and also where public production can be more easily used to satisfy political - that is, redistribution - objectives. By way of contrast, Baumol (1983) conjectures that the inefficiency of public production makes it an attractive alternative to private production when the profit motive creates a 'supply-side' moral hazard that may drive private firms to act counter to the public interest.

Despite the fact that the present investigation fits within the general scope of this recent literature, these hypotheses are not well-suited for this study. The problem is that they are designed to explain variation in production modes across industries, while our study examines variation in production modes for a single industry across states. We suggest that the criteria rele- vant for a comparison across industries are not necessarily relevant for a single-industry comparison across states. For example, although the relative costs associated with monitoring privately produced output in one industry may certainly differ from the corresponding costs for another industry, there is no a priori reason to expect these costs to differ when the identical service is being produced. For monitoring costs to differ across states for the same industry, the costs of resources used in monitoring activities, the nature of monitoring technology, or the capability of bureaucrats must differ across states. Given the similarities in bus transportation technology across states and the mobility of resources, any pronounced difference in relative monitoring costs for this industry across states seems unlikely. Similar arguments apply to redistribution activity and private profit seeking activity yielding supply-side moral hazard. It follows that we do not base our study on these hypotheses. We begin by outlining our theoretical expla- nation of the determinants of the variation in production mode for a single industry.

Because the choice of production mode for the output investigated in this paper is a decision of public bureaucrats, our theoretical model is derived from the economics of property rights developed initially by Armen Alchian (1965) and the bureaucratic utility maximization paradigm formalized by William Niskanen (1971). Given that the foundations of our model are found in the existing literature on property rights and bureaucratic behav-

214

ior, this paper claims no revolutionary theoretical advances. At the same time, the paper does represent the first time the paradigm has been utilized to analyze the production mode decision of public bureaucrats in detail.

To the extent that economic decisions are made in the public sector, management (that is, public bureaucrat) rights to any residual resulting from their decisions can be taken to be nontransferable. Owner (that is, tax- payer) rights to any residual also are nontransferable. As is well known, physical relocation into or out of political jurisdictions is the only way ownership to residual rights can be altered. Consequently, taxpayers have a reduced incentive to detect bureaucratic behavior inconsistent with their own interests. As a result, the remuneration to the public sector bureaucrat associated with provision of bus services is not as strongly tied to economic performance as it would be for a private sector decision maker. This means that the cost to bureaucrats in terms of forgone monetary income of engag- ing in suboptimal behavior in terms of production efficiency or output quality is lower than it would be if residual rights were transferable. For si- milar reasons, the monetary penalties public sector bureaucrats incur by in- corporating various nonmonetary amenities into the production process are lower than for their private sector counterparts. With the trade-off between nonmonetary amenities and monetary returns more limited with public (notfor-profit) behavior than with private (for-profit) behavior, one should expect to observe more of these amenities in the public sector.

To place the bureaucratic decision about the production mode for school transportation in terms of this utility maximization perspective, we begin by assuming there are no systematic differences in preferences on the part of bureaucrats for one production mode as opposed to the other. In selecting a production mode, each bureaucrat is assumed to maximize a utility function which includes as arguments a variety of monetary and nonmonetary aspects of the choice, subject to various constraints on his or her behavior. The assumed lack of any systematic differences in preferences for a particular production mode means that the choice of a production mode reflects only differences in the cost to the bureaucrat of one mode relative to the other. The inclusion of various nonmonetary aspects of the choice in the analysis serves to broaden the concept of costs. Our hypothesis is that where private production is relatively more (less) costly to the bureaucratic decision maker personally, less (more) of it will be observed.

Being more specific, in selecting a production mode for school transpor- tation, the bureaucrat is assumed to have a utility function of the following form:

U = u(Z, J, S, G, Ti, Tk), (1)

215

where

Z = consumption of market goods, J = consumption of employment-related 'perks',

p p c c S = ot L u + ot L u, the total amount of labor strike activity of both

public and contract labor associated with providing trans- portation,

p p c c G = ~ L u + ~ L u, the total amount of nonstrike job actions of both

public and contract labor associated with providing transpor- tation,

T 1 = tl(LO/LC), the level of constituent preferences for using public rather than private labor inputs to produce publicly funded services,

p c T k = tk(K /K ), the level of constituent preferences for using public

rather than private capital inputs to produce publicly funded services.

The o~'s and ~'s represent exogenously determined probabilities of strikes and nonstrike job actions, respectively, by units of unionized labor, L u. Nonunionized labor, Ln, is assumed not to be involved in strikes or non- strike job actions and does not enter into the utility function. The super- scripts p and c which accompany the o~'s, ~'s and L u denote whether we are referring to public employees (p) or private contract labor (c), respectively. The terms t 1 and t k are constituent preference parameters representing pre- ferences for public rather than private labor (L p versus L c) and public rather than private capital (K ° versus Kc). Utility is assumed to vary positi- vely with the first two arguments in the utility function and negatively with the latter four.

The rationale for including the first two arguments in the utility function is straightforward. They are included to make the function complete. The latter four arguments deserve detailed explanation. The distinction between public and private production relates directly to the ownership of the resour- ces used in the production process. Pure private production is characterized by the use of privately owned capital (all nonlabor inputs) and private con- tract labor services; whereas pure public production uses publicly owned capital (all nonlabor inputs) and public employees in the production pro- cess. It follows that the choice of the production mode (public or private) is equivalent to the choice of public or private inputs. This choice, therefore, must be dependent on differences in the characteristics of public sector and private sector inputs and input markets. These characteristics include the costs of obtaining inputs and monitoring their performance, the physical and quality attributes of inputs, their durability and reliability, preferences for particular types of inputs, and the costs of retaining them. Specifically,

216

the choice of production mode is based on the choice of inputs and input characteristics that minimize the personal cost to the decision maker of providing the publicly funded service.

One particular input market characteristic is labor market turmoil. Labor market turmoil, whether it be strikes or nonstrike job actions, is here viewed as an indicator of quality and reliability problems with labor inputs. These problems impose personal costs on public bureaucrats, making the decision makers' lives 'difficult.' Other things equal, bureaucrats are expected to take action to avoid such turmoil, even though they have no explicit claim on any monetary profits which result from the production mode decision. Obviously, all labor market turmoil - whether from public or contract labor - is personally costly to the decision maker. However, the influence on the production mode decision exerted by this labor turmoil is assumed to operate via the relative amounts of turmoil in the public and private sectors. For example, the more labor turmoil in public production relative to private production, the more likely is the bureaucrat to opt for private production assuming other things equal. By selecting units of labor from the labor market with less turmoil, the bureaucrat reduces the disutility asso- ciated with total labor turmoil.

Constituent preferences for the utilization of public sector or private sector inputs are regarded as another type of input market characteristic. The decision maker faces a more constrained choice of inputs as constituent preferences increase. Constituents may impose costs on decision makers who select input utilization patterns contrary to their preferences. These costs may result from protest activities or other actions designed to remove the decision maker from power. It is assumed these costs increase as the level of constituent preferences (T 1 or Tk) increases, holding input utilization patterns constant. Although these costs may or may not have an explicit monetary dimension, they nevertheless contribute to the quality of bureau- cratic life. Consequently, the bureaucrat is likely to prefer less of these costs rather than more.

All nonlabor inputs (capital) are assumed to be incapable of striking or participating in nonstrike job actions once they have been purchased. These inputs are not capable of creating input market turmoil. It follows that there would be no nonmonetary costs due to input market turmoil to the bureau- crat of using publicly owned versus privately owned capital. Utilization dif- ficulties with capital, therefore, do not enter the utility function.

The nontransferability of ownership claims partially distances the bu- reaucratic decision maker from taxpayer-owners. Given this attenuated re- lationship, the bureaucratic decision on production mode in a public sector setting is fundamentally different than in the private sector. Of course, no decision maker prefers, for example, more labor market turmoil to less, holding other things constant. Public sector decision makers, however, are

217

less willing to act to reduce monetary costs by increasing nonmonetary costs than in the private sector, because they receive little personal benefit from such actions. It follows that nonmonetary factors are expected to play a more prominent role in the production mode choice than monetary factors in a public sector setting due to this difference in the structure of in- centives.

The public bureaucrat maximizes this utility function (equation 1) subject to the following constraints:

p p c c F _> WuL u (1 -aP) + WuL u ( 1 - c)

+ reK c + pjJ;

X o < X = X p + XC;and

p p c c rPK p + WnL n + WnL n +

(2)

(3)

Z _ I = 6X o + Y. (4)

Rather than going through a detailed explanation of each term in the constraints, all terms in equations (2) through (4) are defined in Table 1 for the reader's convenience.

The constraint on the decision maker which equation (2) represents is the notion of a fixed public budget (F) for transportation. In facing this constraint, the bureaucrat is confronted with: (1) market determined prices of labor and capital inputs (w's and r's); (2) exogenously determined prob- abilities of labor strikes and nonstrike job actions (a's and/Ts); and (3) a market determined price of employment-related 'perks' (pj). To the ex- tent that the relative monetary cost of the two production modes influences the bureaucrat's choice, this influence is captured in equation (2). Equa- tion (3) indicates that decision makers must provide a minimally acceptable level of transportation services to retain decision-making authority. Final- ly, equation (4) notes that decision makers cannot spend more on market goods than is earned in total income. As in most models of not-for-profit behavior, the portion of the decision maker's income derived from the pro- vision of bus services is assumed to be unaffected by levels of production in excess of the minimally acceptable level (I - Y = ~X o if X _> Xo). There is no direct incentive for the decision maker to choose the least costly method of production or to minimize the amount of services provided for a particular level of cost, because there is little gain associated with such actions.

The solution to this utility maximization problem implies a choice of par- p c p c K c ticular levels of Z, J, Lu, Lu, Ln, Ln, K p, and by the decision maker. As

in the standard theory of consumer behavior, the decision maker's choice for each of these variables is a function of the exogenous variables in the

218

Table 1. List of theoretical variables

Z =

J =

L p = L cu =

L ~ = L n =

L ~ = L c =

K p = K c =

c

~3 p = Bc =

t I =

t k = F =

X =

X p = X c =

x(.) = X o =

I =

Y = 6 =

W p =

W =

w ~ =

W = n

r p =

r c =

pj =

P z =

units of market goods consumed,

units of 'perks ' consumed,

units of unionized public labor,

units of unionized contract labor,

units of nonunion public labor,

units of nonunion contract labor,

units of public labor (Lu ° + Ln°),

units o f contract labor (L c + LC),

units of publicly-owned capital,

units of contract capital,

probability of strike by a unit o f unionized public labor,

probability o f strike by a unit of unionized contract labor,

probability of a nonstrike job action by a unit of unionized public labor,

probability of a nonstrike job action by a unit of unionized contract labor,

communi ty taste parameter for public versus private labor,

communi ty taste parameter for public versus private capital,

public funds available for bus expenditure,

amount of bus services produced,

X(Lu p (1 - aP) + Ln p, KP), the amount of publicly produced bus services,

x(LC(1 -txC)+LC n' Kc)' the amount of privately (contract) produced bus services,

production function for bus services,

min imum acceptable amount o f bus services,

decision maker ' s employment income,

income from satisfactory performance of duties other than bus service provision,

decision maker ' s income per unit o f bus service produced, where I - Y = /~X °

i f X -> X o a n d I - Y = O i f X < Xo,

wage rate of unionized public labor,

wage rate of unionized contract labor,

wage rate of nonunion public labor,

wage rate of nonunion contract labor,

unit cost of publicly-owned capital,

unit cost of contract capital,

price per unit of 'perks, ' and

price per unit of market goods (Pz = 1).

p c p c constrained utility maximization problem. The choice of L u, L n, L n, L n, K p, and K c determines the level of public and private production of bus

services - X p and X c. It follows that the decision maker ' s choice of pub-

lic versus private production is implicitly a function of the same set of

exogenous variables affecting the pr imary choice variables. More formally, the choice of public versus private production is deter-

mined by

219

p c p c p c x C / x p = f(otP/ot c, tiP/•, tl, tk,Wu/Wu, Wn/Wn, r / r , pj, Pz, I), (5)

where

fl, f2, fs, f6, f7 -> 0, f3, f4 -< 0, and f8, f9, flo ~ 0.

The definitions of the terms in equation (5) also can be found in Table 1. The fi's are the partial derivatives of f(-) with respect to the ith argument. For example, if the likelihood of strike activity in the public sector labor force relative to that in the private sector increases (that is, if c~P/oz c increa- ses), the decision maker will be more likely to choose contract (private) production of bus services, ceterisparibus, to avoid increased labor turmoil. Similarly, if the wage rate of public sector labor relative to private sector

p c p c labor increases (that is, if Wu/W u and/or Wn/W n increase), the decision maker may be more likely to select private production, ceteris paribus, because of the increased expense of producing the minimally acceptable level of service employing public labor.

2. Data and estimation procedure

The choice of public versus private production of school bus transportation is analyzed empirically to demonstrate the relative importance of nonmone- tary versus monetary constraints on bureaucratic decision makers' beha- vior. Although decisions concerning the production of school transporta- tion usually are made by the local school district bureaucracy in conjunction with the local school board, the data necessary to estimate the model are not available at the school district or county level. State-level data for each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia for the 1979-80 school year are employed in our empirical analysis. The specific empirical variables used are listed in Table 2. More detailed descriptions of these variables along with their sources are presented in the Appendix.

To estimate the model, proxy variables are used for several of the factors in the theoretical model discussed in the previous section. In the empirical counterpart to equation (5), the dependent variable (PRIBUS) is the propor- tion of public school buses in each state that is privately owned and opera- ted. This variable corresponds to x C / x (where X = X c + X p) in the theoretical model. Strike activity in the local public sector relative to the private sector (RELSTRIKE) is used as a proxy for uP/or c in the model. With respect to other types of labor difficulties, if the probability of a nonstrike job action increases as the degree of unionization increases, then ~P will be positively correlated with LuP/L p, and ~c will be positively correla-

c c ted with L u / L . Under this assumption, relative unionization (REL- UNION) may be used as a proxy for ~P /S in the model. 5

220

Table 2. List of empirical variables

PRIBUS =

RELUNION =

RELSTRIKE =

SPENDPRO =

TAXPRO =

ADA =

RELWAGE =

POP =

APOP =

POPDEN =

METRO =

PERSINC =

Proportion of Buses Privately Owned

Relative Unionization (Public/All)

Relative Strike Activity (Public/All)

Local Government Spending Proclivity

Local Government Taxation Proclivity

Average United States House of Representatives rating for 1979 by Amer-

icans for Democratic Action for each state.

Relative Wage Rate (Public/Private)

Total Population

Change in Population (1970-1980)

Population Density

Percent Metropolitan Population

Personal Income per Capita

Ideally, these variables should measure the relative strike activity and re- lative unionization within the labor market in which the decision maker operates. Unfortunately, data on strike activity and unionization rates of local public sector employees are not available for school transportation workers only, or the broader occupational classification of transportation workers. Our variables RELSTRIKE and RELUNION measure strike activ- ity and unionization for all local public sector employees relative to all non- agricultural workers. Although these are not perfect proxies for the relevant variables, it is reasonable to assume that, given the existing labor market institutions within a particular state, strike activity and unionization are correlated across industries. We also argue that changes in strike activity or unionization in nearby areas or related industries are likely to affect the decision maker 's expectations regarding potential labor relations difficul- ties in his own setting. If these assumptions are accurate, then RELSTRIKE and RELUNION should be reasonable proxies for aP/t~ c and BPI~ c, respectively.

The average wage rate of local public sector employees relative to the average wage rate of nonagricultural workers (RELWAGE) is used as a

p c p c . proxy for Wu/W u and Wn/W n. Again, data for a more precise measure of the relevant relative wage rates are not readily available. Constituent prefer- ences for public production (t I and tk) are proxied by three alternative vari- ables - public spending proclivities (SPENDPRO), taxing proclivities (TAXPRO), and political ideology of elected officials (ADA). To some degree, the propensity of citizens within states to place a larger share of expenditures under local public control is probably related to a taste on their part for greater public rather than private production of publicly funded services. The variable SPENDPRO - local public spending as a share of personal income - is likely to be positively correlated with t I and t k. A similar argument holds for citizens within states giving local government

221

greater control over income through higher taxes. The variable TAXPRO, a substitute for SPENDPRO, is local taxes as a share of personal income. More specifically, we assume that with high levels of local public spending, or local taxation, a greater share of these public expenditures or taxes is allo- cated to publicly produced goods and services rather than to privately pro- duced (contract) goods and services. The average ADA rating of states' Congressional delegations represents another (albeit imperfect) measure of the political ideology of bureaucrats' constituents. If 'liberals' prefer public production to private production, the variable ADA (another substitute for SPENDPRO) is positively correlated with constituent preferences for public production.

In addition, several state demographic characteristics (POP, APOP, POPDEN, and METRO) and per capita income (PERSINC) are included in several specifications. Because of their widespread use in public expendi- ture studies, these variables are included here to determine their possible re- levance to the public/private choice. The price of 'perks' (pj) and the price of market goods (Pz) are assumed constant in our sample and, therefore, are excluded from the specification. Because there are no good measures of capital costs (r's) for all 50 states, no proxies for rP and r c are included in the specification. 6 The decision maker's income also is excluded because it is unknown.

The empirical relationship to be estimated has the general form:

PRIBUS = g(N, M, D), (6)

where N is a set of nonmonetary factors, M is a set of monetary factors, and D is a set of demographic characteristics. Different specifications are exami- ned to determine the robustness of the coefficient estimates. Because the range of the dependent variable is restricted between 0 and 1, the error term of the general linear regression model is not homoscedastic. Consequently, estimates obtained using OLS are inefficient, rendering statistical inferences from the standard errors of the coefficients imprecise. To obtain more pre- cise estimates, logit analysis is used. 7

3. Results

The test results from the first set of specifications are presented in Table 3. In addition to the primary variables which reflect relative labor difficulties (RELSTRIKE and RELUNION), community preferences (SPENDPRO, TAXPRO, or ADA), and relative costs (RELWAGE), several demographic characteristics (POP, APOP, POPDEN, and METRO), and per capita in- come (PERSINC) are included. The signs of the coefficients of nearly all

222

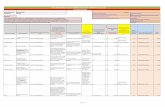

Table 3. Logit results (Dependent variable = PRIBUS)

Independent Alternative specifications variables

3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6

RELSTRIKE .981"** .944*** .973*** 1.15"** 1.19"** 1.23"** (6.21) (6.50) (7.21) (7.89) (7.95) (8.11)

RELUNION .477*** .468*** .481"** .365*** .377*** .395*** (6.86) (5.90) (6.34) (5.73) (5.21) (6.65)

SPENDPRO -2 .06" - - - 3 .80" - - ( -2 .17 ) - - ( -2 .03 ) - -

TAXPRO - 3.78 - - 6.35 -

- ( . 6 2 ) - - ( 1 . 9 2 ) -

A D A - - - .266 - - .401 - - ( - . 7 4 ) - - ( . 6 2 )

RELWAGE 1.33"* 1.45** 1.35"* 1.25"* 1.47* 1.53" (2.90) (3.07) (3.28) (2.94) (2.20) (2.43)

POP - .574** - .613"** - .330* - .288 - .365 - .350 ( - 2 .83 ) ( - 3 . 91 ) ( - 2 . 07 ) ( - 1.72) ( - 1.53) ( - 1.46)

APOP - 3.30*** - 3.32*** - 2.79*** - - - ( - 4.62) ( - 4.57) ( - 3.82) - - -

POPDEN - .0813'* - .0821"* - .0325 - .0350** - .0422"** - .0310 ( -2 .89) ( -2 .90 ) ( - 1.77) ( - 2 . 82 ) ( -3 .60 ) ( - 1.82)

METRO .553 .878* - .0347 .0593 .501 - .0275 (1.35) (2.18) ( - 1.64) (.24) (1.13) ( - 1.20)

PERSINC .384 .317 .292 .558 .276 .305 (.86) (.61) (1.13) (.86) (.81) (1.04)

Constant - 3.15'** - 3.06*** - 2.87*** - 2.97*** - 3.20*** - 3.29*** ( - 5.77) ( - 5.93) ( - 4.29) ( - 4.35) ( - 5.62) ( - 5.78)

x 2 307.8*** 306.5*** 283.4*** 241.2"** 246.0*** 234.1'**

* Significant at the .05 level (two-tailed test). ** Significant at the .01 level (two-tailed test).

*** Significant at the .001 level (two-tailed test).

Note: t-statistics in parentheses; n = 51.

Source: See Appendix.

p r i m a r y v a r i a b l e s a r e a s e x p e c t e d . T h e e s t i m a t e d c o e f f i c i e n t s o f t h e t w o

v a r i a b l e s t h a t m e a s u r e r e l a t i v e l a b o r d i f f i c u l t i e s , t h e c o e f f i c i e n t s f o r s p e n d -

i n g p r o c l i v i t i e s , a n d t h e c o e f f i c i e n t s f o r r e l a t i v e c o s t s a r e al l a s e x p e c t e d .

T h e e s t i m a t e d c o e f f i c i e n t s o f t h e p r i m a r y v a r i a b l e s w i t h s i g n s c o n t r a r y t o

e x p e c t a t i o n s - T A X P R O a n d A D A - a r e n o t s i g n i f i c a n t .

T h e e m p i r i c a l e v i d e n c e f r o m T a b l e 3 s u g g e s t s t h a t a s t h e d e g r e e o f

l a b o r u n i o n i z a t i o n in t h e p u b l i c s e c t o r i n c r e a s e s r e l a t i v e t o t h e p r i v a t e s e c t o r

( t h a t is , a s R E L U N I O N i n c r e a s e s ) , p u b l i c d e c i s i o n m a k e r s a r e m o r e i n c l i n e d

t o s e l e c t p r i v a t e c o n t r a c t i n g , ceteris paribus . L i k e w i s e , as s t r i k e a c t i v i t y in

t h e p u b l i c s e c t o r r e l a t i v e t o t h e p r i v a t e s e c t o r i n c r e a s e s ( t h a t is , as

R E L S T R I K E i n c r e a s e s ) , t h e p u b l i c d e c i s i o n m a k e r is m o r e l i k e l y t o c h o o s e

p r i v a t e p r o d u c t i o n . I n a c o m m u n i t y w i t h g r e a t e r p r e f e r e n c e f o r p u b l i c

Table 4. L o g i t r e su l t s ( D e p e n d e n t v a r i a b l e = P R I B U S )

I n d e p e n d e n t A l t e r n a t i v e s p e c i f i c a t i o n s

v a r i a b l e s

4 .1 4 . 2 4 .3 4 . 4 4 .5 4 . 6

223

R E L S T R I K E .994*** 1.12"** 1.04"** .973*** 1 .06"** .964***

(7.71) (7.91) (6.77) (7.52) (8.41) (7.64)

R E L U N I O N .485*** .438*** .513"** .570*** .404*** .571"**

(7.86) (7.30) (7.49) (9.14) (6.22) (8.93)

S P E N D P R O - 7 .12"** - 5 .25** - 8 .42*** - - -

( - 6 . 2 2 ) ( - 3 . 1 4 ) ( - 6 . 3 0 ) - - -

T A X P R O . . . . 1 3 . 7 ' * * 5.48 - 14 .5"**

- - - ( - 5 .46) (1.67) ( - 4 .72)

R E L W A G E .703 .875* .603 .572 .690* .406

(1.77) (2.31) (1.82) (1.55) (2.38) (.92)

P O P ( - .21 I) - - - .374* - -

( - . 8 5 ) - - ( - 2 . 1 6 ) - -

A P O P - 2 . 2 4 * * * - - 1 .95"** - 2 . 7 5 * * * - - 2 . 4 4 * * *

( - 4 . 2 3 ) - ( - 4 . 6 1 ) ( - 4 . 7 8 ) - ( - 4 . 6 4 )

P O P D E N - - .0311"* - - - .0513"** -

- ( - 2 . 4 3 ) - - ( - 5 . 3 1 ) -

C o n s t a n t - 1 .46"** - 2 . 3 1 " * * - 1 .61"** - 1 .73"** - 2 .97*** - 1 .59"**

( - 4 .07) ( - 4.87) ( - 4 .33) ( - 4 .62) ( - 7 .37) ( - 5.61) 2 X 2 5 8 . 7 * * * 2 5 7 . 0 * * * 2 5 1 . 3 " * * 2 3 8 . 7 * * * 2 3 7 . 5 * * * 2 0 6 . 0 * * *

* S i g n i f i c a n t a t t h e .05 leve l ( t w o - t a i l e d t e s t ) .

** S i g n i f i c a n t a t t h e .01 leve l ( t w o - t a i l e d tes t ) .

*** S i g n i f i c a n t a t t h e .001 leve l ( t w o - t a i l e d tes t ) .

Note: t - s t a t i s t i c s in p a r e n t h e s e s ; n = 51.

S o u r c e : See A p p e n d i x .

production relative to private production (as indicated by a larger SPEND- PRO), private contracting will be less likely. Finally, private production of school transportation may be more attractive to educational decision makers as public-sector wage rates increase relative to private-sector wage rates (that is, as RELWAGE increases).

The results for the demographic and income variables are mixed. In all but one specification, both METRO and PERSINC are not significant, POP is significant in three of six specifications, POPDEN in four of six specifications, and APOP is always significant when included. All coeffi- cients of the three population variables have negative signs. As POP, APOP, or POPDEN increase, public decision makers are less likely to choose private contractors. Even though there are no strong theoretical rea- sons to include these demographic variables, they were included to maintain continuity with the public expenditure literature. 8 A plausible explanation for the negative coefficients of the population variables is that they capture the influence of labor market institutions. Specifically, the more densely populated and populous a state, the more highly developed and organized

224

Table 5. Logit results (Dependent variable = PRIBUS)

Independent Alternative specifications variables

5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4

RELSTRIKE 1.13"** 1.11"** 1.24*** 1.29"** (8.51) (8.77) (8.73) (9.02)

RELUNION .452*** .495*** .513"** .525*** (7.30) (7.82) (8.24) (8.57)

SPENDPRO - 8.03*** - - 7.90*** - ( - 5.92) - ( - 5.41) -

TAXPRO - - 11.3"* - - 10.6'* - ( - 2.92) - ( - 3.14)

RELWAGE .538* .437 - - (2.16) (1.93) - -

Constant - 2.07*** - 2.44*** - 1.73"** - 2.29*** ( - 5.81) ( - 6.15) ( - 8.45) ( - 10.4)

X 2 234.0*** 212.2"** 230.4*** 187.2"**

* Significant at the .05 level (two-tailed test). ** Significant at the .01 level (two-tailed test).

*** Significant at the .001 level (two-tailed test).

Note: t-statistics in parentheses; n = 51.

Source: See Appendix.

are l a b o r marke t s . Less l a b o r supp ly f lexibi l i ty and se l f - employment o p p o r -

tuni tes might exist in such a set t ing. 9 Due to the na ture o f pr iva te con t rac -

t ing for school t r a n s p o r t a t i o n - m a n y pr iva te con t rac to r s are

se l f -employed pa r t - t ime workers - the t r ansac t ion costs o f employ ing pri- vate con t rac to r s in this sett ing m a y be higher . Pa r t - t ime l a b o r is l ikely to be

less readi ly avai lab le in more o rgan ized l abo r marke t s .

A d d i t i o n a l speci f ica t ions are r epor t ed in Table 4 for the pu rpose o f exam- ining the robus tness o f all es t imates . Three var iables inc luded ear l ier ( A D A ,

M E T R O , and P E R S I N C ) have been exc luded f rom Table 4 because o f evi-

dence tha t they are super f luous var iables . 1° In all cases, inc luding those re-

po r t ed ear l ier in Table 3, the chi -square test s tat is t ic al lows re jec t ion o f the null hypothes is tha t all coeff ic ients are zero at be t te r t han the .001 level o f

s ignif icance. W i t h respect to specific var iables in bo th tables (Tables 3 and 4), the es t imated coeff ic ients o f R E L S T R I K E and R E L U N I O N are always posi t ive and s ignif icant at be t te r t han the .001 level, while the es t imated coef- f icient o f S P E N D P R O is always negat ive and s ignif icant . The coeff ic ient o f T A X P R O is negat ive and s ignif icant in two o f five speci f ica t ions . The three

posi t ive coeff ic ients are not s ignif icant . F o r R E L W A G E , while the es t imated

coeff ic ient is posi t ive in all 12 speci f ica t ions , the coeff ic ient is s igni f icant in only 8 o f the 12. I m p o r t a n t l y , the es t imated coeff ic ients o f R E L S T R I K E , R E L U N I O N , and S P E N D P R O are very robus t with respect to changes in speci f ica t ion. The coeff ic ient o f R E L W A G E is fa i r ly robus t wi th respect to

speci f ica t ion changes.a 1

225

The final specifications, reported in Table 5, exclude all demographic variables, because the theoretical justification for including them in the model is questionable. The variable RELWAGE also is excluded from two of the four specifications in Table 5 because monetary costs may not be as important to public-sector decision makers as they are to private-sector de- cision makers. This is due to public decision makers' attenuated claims on explicit monetary profits. The econometric results for these four specifica- tions are even more striking than those reported in Tables 3 and 4. All varia- bles have the correct signs and all but the wage variable (RELWAGE) are highly significant at the .01 level or better.

To determine the relative importance of the variables, the elasticities of the decision makers' responses to changes in the variables for each specifica- tion included in Table 5 are reported in Table 6. The "response elasticity" is the percentage change in the proportion of private buses given a percent- age change in a particular independent variable, ceteris paribus. 12 For example, the average of the response elasticities for all specifications for RELSTRIKE is .59, which indicates that a 10 percent increase in relative strike activity generates a 5.9 percent increase in the proportion of private buses. Relative unionization, as measured by RELUNION, has a similar impact on the public/private choice (see Table 6). Conversely, the one sta- tistically significant elasticity estimate for RELWAGE is approximately half the size of the RELSTRIKE and RELUNION elasticities. Decision makers appear substantially more responsive to changes in nonmonetary constraints than to changes in monetary constraints.

The impact of these nonmonetary constraints is made even more striking by comparing the predicted fraction of private buses in states in extremely different circumstances. For example, in an otherwise average state with no public unions (that is, RELUNION is zero), the predicted fraction of private buses from specification 5.1 in Table 5 is. 16; whereas the predicted fraction is .54 if public employees are four times as unionized as private sector work- ers (that is, RELUNION is four) - a difference of 238 percent.13 Similar- ly, the predicted fraction of private buses for a state with no strikes by public employees (that is, RELSTRIKE is zero) is. 16 compared with .55 for a state where, per worker, public employees miss 65 percent more days due to strike activity than private sector workers (that is, RESTRIKE is 1.65) - a 243 percent difference. The predicted fraction of private buses in an otherwise average state with the lowest spending proclivity (that is, SPENDPRO is .05) is .43 and the predicted fraction of private buses in the state with the highest spending proclivity (that is, SPENDRO is .35) is .06. The difference between these two predicted fractions is over 600 percent. 14

Overall, the empirical evidence presented in this paper is exceptionally strong. Although some of the data employed are not ideal, the very strong statistical results, at the very least, must be viewed as highly suggestive of the factors that determine the choice of public or private bus services.

226

Table 6. Elasticity estimates

Independent Alternative specifications from Table 5 variables

6,1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Averages

RELSTRIKE .563* .553* .618" .643* .594* RELUNION .561" .614" .636* .651" .616" SPENDPRO - .658* - - .647* - - .653* TAXPRO - - .367* - - .286* - .327* RELWAGE .379" .308 - - .344

* Significant at the .05 level.

Note: Elasticities computed at the sample means of the independent variables.

Source: See text.

5 . C o n c l u s i o n s

The generalization of the findings of this study to other industries depends

on similarities in the institutional, legal, and production characteristics. It is

hard to conceive that school bus transportation is so unique that its study

should not yield conclusions with more general applications. It is important

to note that school bus transportation entails a relatively simple production

process. Moreover, where private contracting is utilized, the assignment of

individual bus routes is typically based on open, competitive bidding. Market

entry by private firms is not difficult; legal constraints are largely limited to

possessing a chauffeur 's license and passing a physical exam. Capital costs

of entry can be as low as a few hundred dollars - the cost of a used school

bus. The overall simplicity of this industry enhances the general applicability

of our results. This simplicity makes it more likely that our results indicate

only the factors influencing the choice of ownership form and are not measu-

ring other influences on the ownership choice of school officials.

Going beyond the technical results of the study, the importance of non-

monetary considerations suggests that it is unreasonable to expect public sec-

tor choices to be affected by further evidence on the cost inefficiency of public production. Because factors such as labor market institutions and similar constraints are outside the purview of local government, it should not

be surprising that public and private production of publicly funded services

will continue side by side in spite of cost differences. It would seem that a fun- damental restructuring of the property rights in the public sector - a move-

ment toward a private property rights structure - would be necessary to alter public sector choices in the direction of selecting more cost effective produc-

tion modes.

227

NOTES

1. There are several excellent review articles dealing with this literature. See Bennett and Johnson (1980), Borcherding, Pommerehne, and Schneider (1982), De Alessi (1980), and Spann (1977). Two recent studies, which concern railroad transportation and school bus transportation, present empirical evidence supporting the conclusion concerning market competition. See Caves and Christensen (1980) and McGuire and Van Cott (1984)

2. See Baumol (1983), Borcherding (1983), and De Alessi 0982). Becker (1983), Borcherding, Pommerehne, and Schneider (1982), and Breton and Wintrobe (1982) also address this issue tangentially. The often-cited paper on how government assigns rights to private taxi- cab firms (Eckert, 1973) investigates how differences in the composition of regulatory agencies affected the number of licensed private firms in different cities. Similarly, another often-cited paper (Pashigan, 1976) investigates the conversion of privately funded urban transit services to publicly funded urban transit services. Neither of these studies is con- cerned with the situation in which governmental agencies were deciding between public and private production of a publicly funded service.

3. See Niskanen (1971) for one bf the first contributions. 4. Data relating to the public/private split on bus ownership and funding are obtained from

the National Association of State Directors of Public Transportation Services (1982). The public/private split is not evenly distributed across the country. For example, during the 1979-80 academic year the percent of school buses owned and operated by private contrac- tors was zero in North Carolina, Ohio, and Texas; 98 percent in Hawaii; 79 percent in Massachusetts; and 72 percent in Wisconsin.

5. The variable RELUNION is (LuP/LP)/(Lu/L), where L u is all union labor, Lu p + L c, and L is total labor, L p + L c.

6. The interest rate on municipal bonds and corporate bonds in each state could be used as proxies for r p and r c, respectively. These interest rates are unlikely to be strongly cor- related with the actual user cost of capital. Obtaining information necessary to calculate the actual cost of public and private capital in each state would be prohibitively costly - if such information even exists.

7. See Goldberger (1964). Logit has another advantage over OLS in this instance. The func- tional form implied by the logit specification is more realistic than a linear probability model, given the limited nature of the dependent variable (Hanushek and Jackson, 1977: Ch. 7). Of course, the model can be estimated in log-odds form - where the dependent variable is log (P/I-P) - if observations with limit values (0 or 1) are assigned some value arbitrarily close to the limit (for example, .01 or .99). Coefficient estimates we obtained by OLS using this dependent variable (log-odds form) and the same set of independent variables are similar to those we obtained by logit in terms of signs. In most cases standard error estimates are higher for OLS than for logit. It also should be noted that the R-square for most of the OLS regressions range between .35 and .50. All OLS results are available from the authors on request.

8. In a similar context concerning public expenditure models, Borcherding and Deacon (1972) argue that the arbitrary use of sociodemographic variables is not well founded in theory.

9. For a discussion of the development and organization of labor markets and organized labor's impact on labor supply, see Marshall, Cartter, and King (1976): Chs. 2 and 8).

10. The exclusion or inclusion of these variables changes neither the other coefficient values nor their standard errors "significantly" (compare the respective columns of Tables 3 and 4). See Rao and Miller (1971: 35-40) for a discussion of superfluous variables.

11. The importance of determining robustness of coefficient estimates with respect to changes in specification is demonstrated in Learner (1983).

12. The response elasticity with respect to variable X i is e i --- (0P/0Xi)(Xi/P), where P is the fraction of private buses. The elasticities reported in Table 6 are calculated at the sample means of the independent variables.

228

13. The predicted fraction of private buses is determined by

15 = i/(1 + e-~x~i) , where hi is the estimated coefficient of an independent variable Xi, and X~ is a particular value of X i. In this particular example, the coefficient estimates from specification 5.1 (Table 5), along with mean values for RELSTRIKE, RELWAGE, and SPENDPRO are used to compute f' for the actual minimum and maximum values of RELUNION contained in our sample (0 and 4 respectively).

14. In these latter two examples, the coefficient estimates from specification 5.1, along with the mean values of the other variables, also are used to compute P for the actual minimum and maximum values of RELSTRIKE (0 and 1.65, respectively) and SPENDPRO (.05 and .35, respectively) contained in our sample.

REFERENCES

Alchian, A.A. (1965). Some economics of property rights. II Politico 30: 816-829. Baumol, W.J. (1983). Toward a theory of public enterprise. Working paper, New York

University, August. Becker, G.S. (1983). A theory of competition among pressure groups for political influence.

Quarterly Journal o f Economics 98: 371-400. Bennett, J.T., and Johnson, M.H. (1980). Tax reduction without sacrifice: Private sector pro-

duction of public services. Public Finance Quarterly 8" 363-396. Borcherding, T.E. (1983). Toward a positive theory of public sector supply arrangements. In

J. R. S. Prichard (Ed.), Crown corporations in Canada: The calculus o f instrument choice. Toronto: Butterworths.

Borcherding, T.E., and Deacon, R. (1972). The demand for the services of non-federal govern- ments. American Economic Review 62:891-901.

Borcherding, T.E., Pommerehne, W.W., and Schneider, F. (198:2). Comparing the efficiency of private and public production: The evidence from five countries. Zeitschrift far Na- tional6konomie, Supplement 2: 127-156.

Breton, A., and Wintrobe, R. (1982). The logic o f bureaucratic conduct. New York: Cam- bridge University Press.

Caves, D.W., and C hristensen, L.R. (1980). T he relative efficiency of public and private firms in a competitive environment: The case of Canadian railroads. Journal o f Political Econo- my 88: 958-976.

Congressional Quarterly Weekly Report (1980). How special-interest groups rate representa- tives. 38: 1118-1119.

De Alessi, L. (1980). The economics of property rights: A review of the evidence. Research in

Law and Economics 2: 1-47. De Alessi, L. (1982). On the nature of consequences of private and public enterprises. Min-

nesota Law Review 67:191-209. Eckert, R.D. (1973). On the incentives of regulators: The case of taxicabs. Public Choice 14:

83-100. Goldberger, A.S. (1964). Econometric Theory. New York: John Wiley. Hanushek, E., and Jackson, J.E. (1977). StatisticalMethodsfor Social Scientists. New York:

Academic Press. Leamer, E. (1983). Let's take the con out of econometrics. American Economic Review 73:

31-43. McGuire, R.A., and Van Cott, T.N. (1984). Public versus private economic activity: A new

look at school bus transportation. Public Choice 43: 25-43. Marshall, R.F., Cartter, A.M., and King, A.G. (1976)Laboreconomics: Wages, employment,

and trade unionism. New York: Richard D. Irwin. National Association of State Directors of Pupil Transportation Services (1982). Statistics on

school transportation 1979-1980. School Bus Fleet 26: 60-61.

229

Niskanen, W.A. (1971). Bureaucracy and representative government. Chicago: Aldine- Atherton.

Pashigan, P.B. (1976). Consequences and causes of public ownership of urban transit facilities. Journal o f Political Economy 84: 1239-1259.

Rao, P.M.. and Miller, R.L. (1971). Applied econometrics. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. Spann, R.M. (1977). Public versus private provision of governmental services. In T.E. Bor-

cherding (Ed.), Budgets and bureaucrats: The sources o f government growth. Durham, NC: Duke University Press: 71-89.

APPENDIX

Sources and computation of data

Nonmonetary considerations A. Relative Strike Activity - local public employee days idle due to work stoppages as

a fraction of local public employment relative to nonagricultural days idle as a fraction of nonagricultural employment. To present a more accurate proxy for the probability of relative strike activity in the two sectors, the statistic is an average for the six years between October 1974 and October 1979. Data related to local public employees were obtained from Table 7 and Table 3, respectively, of the 1974 through 1979 issues of Labor-Management Relations in State and Local Governments, a joint publication of the United States Department of Commerce and United States Department of Labor. Data related to nonagricultural employees between 1974 and 1979 were obtained from various issues of the Statistical Abstract o f the United States.

B. Relative Unionization - percent of local public employees in bargaining units relative to percent of nonagricultural employees in unions. Local public employees in "employee associations" (rather than "bargaining units") were not treated as union workers, because "associations" usually do not negotiate over economic issues. The data are for 1978. Data for local public employees were obtained from Table 4 of Labor-Management Relations in State and Local Governments: I978, a joint publica- tion of the United States Department of Commerce and United States Department of Labor. Data concerning unionized nonagricultural employment were obtained from the Directory o f National Unions and Employee Associations, I979, published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor.

C. Local Government Spending Proclivity - total local government expenditures for the 1978-79 fiscal year as a fraction of 1979 state personal income. Local expenditure data were obtained from Table 12 of Government Finances in 1978-79, published by the Bu- reau of Census, United States Department of Commerce. State personal income data were obtained from the 1980 edition of the Statistical Abstract o f the United States.

D. Local Governmdnt Taxation Proclivity - total local government taxes for the 1978-79 fiscal year as a fraction of 1979 state personal income. Local tax revenue data were ob- tained from Table 5 of Government Finances in 1978-79, published by Bureau of Cen- sus, United States Department of Commerce. State personal income data were obtained from the 1980 edition of the Statistical Abstract o f the United States.

E. ADA Ratings - Average of ratings of voting records by Americans for Democratic Action among each state's delegation to the United States House of Representatives. Data were obtained from the Congressional Quarterly. Because the data for the District of Columbia were not available and the D.C. representative is a well-known liberal, D.C. was assigned the highest possible rating. (The logit analysis also was performed with D.C. assigned the average possible rating. No differences in the results were found.)

230

II Monetary considerations A. Relative Wage Rate - full time (173.2 hours per month) equivalent wages of local

public employees as a fraction of full time equivalent wages of nonagricultural produc- tion workers for each state. The data are for the year 1978. The data for local public employees were obtained in the 1979 edition of the Statistical Abstract o f the United States, while the data for nonagricultural production workers were obtained from the 1980 edition of the Statistical Abstract o f the United States.

I I I. Demographic factors A. All demographic data are available in various issues of the Statistical Abstract o f the

United States.

IV. Dependent variable A. Proportion of Buses Privately Owned - total number of school buses owned and

operated by private contractors (privately owned) relative to the total number of all school buses - both privately and publicly owned (owned and operated by local school districts). The data on school bus ownership are provided by the National Association of State Directors of Pupil Transportation Services contained in School Bus Fleet, December-January, 1982.