The Challenge of Cultural Diversity in Europe: (Re)designing Cultural Heritages through...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

5 -

download

0

Transcript of The Challenge of Cultural Diversity in Europe: (Re)designing Cultural Heritages through...

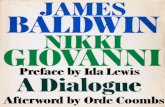

Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-KnowledgeVolume 9Issue 4 Contesting Memory: Museumizations ofMigration in Comparative Global Context

Article 6

1-1-2011

The Challenge of Cultural Diversity in Europe:(Re)designing Cultural Heritages throughIntercultural DialogueEstela Rodríguez GarcíaUniversitat Ramon Llull, [email protected]

Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/humanarchitecturePart of the Cultural History Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the Social History

Commons

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Human Architecture:Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please [email protected].

Recommended CitationGarcía, Estela Rodríguez (2011) "The Challenge of Cultural Diversity in Europe: (Re)designing Cultural Heritages throughIntercultural Dialogue," Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge: Vol. 9: Iss. 4, Article 6.Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/humanarchitecture/vol9/iss4/6

49 H

UMAN

A

RCHITECTURE

: J

OURNAL

OF

THE

S

OCIOLOGY

OF

S

ELF

-K

NOWLEDGE

, IX, 4, F

ALL

2011, 49-60

I. I

NTRODUCTION

: M

ULTICULTURAL

S

OCIETIES

AND

C

OLLECTIVE

I

MAGINARIES

“

Ponte en su piel”

(“Put Yourself in HerSkin”) was part of a sensitivity campaignpromoted by the city of Tarragona in 2006that puts into context many elements of thedebate we aim to expose in this article. Atfirst glance, it speaks to us of the so-called“new immigration” of people from coun-

tries outside the European Union who havearrived in Catalonia in the past few decadesand who now live in our cities, creatingnew realities and bringing to the fore newchallenges and defining society’s newneeds in the early years of the 21

st

century(Pajares 2005; García y Barañano 2003). Butit also speaks to us of our anxieties andobsessions, our fears and our way ofperceiving “others.” Western societies haveconstructed their collective imaginaries

Estela Rodriguez García is a Senior Researcher in the Communication Department at the Ramon Llull Univer-sity (Barcelona, Spain). She is Director of the Center of Study and Investigation for Global Dialogues. And, incollaboration with Ramon Grosfoguel, she is Professor and coordinator of the International annual SUMMERSCHOOL "Interculturality, International Migration and the Dialogue between Civilizations Before and After 9/11" co-sponsored by the University of California at Berkeley and the Foundation of the Universidad Autonomade Barcelona. She is also a member of the Sociedade Cientifica de Estudos da Arte, Universidade de Sao Paulo,Escola de Comunicaçoes e Artes.

The Challenge of Cultural Diversity in Europe(Re)designing Cultural Heritages through

Intercultural Dialogue

Estela Rodríguez García

Centro de Estudios Diálogo Global, Spain––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Abstract: Western societies have constructed their collective imaginaries through the recupera-tion of objects and traditions that define them best. Europe mythically shaped its self-definitionby “whitening” it, denying any recognition whatsoever of the cultural diversity of the peoplewho inhabited the region for centuries. Since the 15th and 16th centuries, with the Renaissance,the invention of a common past involved emphasizing the Greek and Latin past, disconnectedfrom any type of relationship with other cultures, religions or skin colors. The white marble ofRoman sculptures, which many farmers found while tilling their land, became the desired color,the symbol of a Europe that nullified any presence of cultural and religious difference. Withinthis chosen definition, the chromatic spectrum of the others and their everyday objects were firstdefined as the war booty of dominant aristocracies, and later, as objects fit for ethnological muse-ums. Today we have diversity in our streets and not just in our museums. When we walkthrough our cities, new strokes, colors and styles of clothing take us by surprise–those of foreign-ers from outside the European community, those who remain outside the Europe of their dreamsand do not enjoy the citizenship rights of inhabitants of the European Union’s member states.

H

UMAN

A

RCHITECTURE

: J

OURNAL

OF

THE

S

OCIOLOGY

OF

S

ELF

-K

NOWLEDGE

ISSN: 1540-5699. © Copyright by Ahead Publishing House (imprint: Okcir Press) and authors. All Rights Reserved.

HUMAN ARCHITECTURE

Journal of the Sociology of Self-

A Publication of OKCIR: The Omar Khayyam Center for Integrative Research in Utopia, Mysticism, and Science (Utopystics)

50 E

STELA

R

ODRÍGUEZ

G

ARCÍA

H

UMAN

A

RCHITECTURE

: J

OURNAL

OF

THE

S

OCIOLOGY

OF

S

ELF

-K

NOWLEDGE

, IX, 4, F

ALL

2011

through the recuperation of objects andtraditions that define them best (Anderson1993). At the time of the birth of nation-states, in the colonial and post-colonialeras, and in the current period of globaliza-tion, the icons and symbols that are a partof this community have been abstractedfrom their original locations and broughtinto those great storage areas we call muse-ums. As a product of the era of the birth ofnationalisms, museums clearly define,through the selection of cultural artifacts,who has belonged to a community andwho has not, who “we” are and who are the“others.”

Europe mythically shaped its self-defi-nition by “whitening” it, denying anyrecognition whatsoever of the culturaldiversity of the people who inhabited theregion for centuries (Shohat and Stam1994). Since the 15

th

and 16

th

centuries,with the Renaissance, the invention of acommon past involved emphasizing theGreek and Latin past, disconnected fromany type of relationship with othercultures, religions or skin colors (Mignolo2003). The white marble of Roman sculp-tures, which many farmers found while till-ing their land, became the

desired color

, thesymbol of a Europe that nullified any pres-ence of cultural and religious difference.Within this chosen definition, the chromaticspectrum of

the others

and their everydayobjects were first defined as the war bootyof dominant aristocracies, and later, asobjects fit for ethnological museums(Chakrabarty 2000).

Today we have diversity in our streetsand not just in our museums. When wewalk through our cities, new strokes, colorsand styles of clothing take us by surprise(Barkan and Denise 1998)—those offoreigners from outside the Europeancommunity, those who remain outside theEurope of their dreams and do not enjoythe citizenship rights of inhabitants of theEuropean Union’s member states. As wehave stressed in other studies, the defini-

tion of European identity has been linkedwith the idea of a cultural homogenization,but above all, as the philosopher RosiBraidotti has written,

1

“this myth continuesto be crucial for the legend of Europeannationalism.” For this author, the reasonEuropean unification has taken 50 years tobring questions of culture and education tothe agenda, above and beyond economicand military questions, has to do with thecomplexity of the definition of theseconcepts for each and every member coun-try. Various identities—or

figurations

asBraidotti calls them—“remain outside thisEurope: the migrant, the exile, the refugeeor asylum-seeker, the undocumentedforeigner, the homeless and the uprooted,the Filipina nanny who has replaced themore familiar figure of the “

chica canguro

”[babysitter] or

au pair

girl….” These immi-grants, who have lived among us fordecades, receive scant attention from themedia, which often associate them withsituations of criminality, underdevelop-ment or subalternity, reinforcing thecultural imaginaries that negatively affectour perception of other cultures (Rodríguez2005). The same does not go for Euro-American globalized cultures, such as theHollywood culture industry, consumermodes and products, music or fast food.These cultural products or products ofconsumption have become globalized tosuch an extent that it is difficult to knowwhich country we are travelling in and thiscomplicates our task of figuring out what totake pictures of in order to show to ourfriends after our trip. Néstor GarcíaCanclini, the Argentinian anthropologistliving in Mexico, pays close attention tothese new cultural mappings in his work

1

Braidotti warns that the European Union’sproject may be subject to the “Fortress Europe”syndrome, that is, a Europe that protects itselfagainst the “invasion” of foreigner and foreigncustoms and traditions. See Braidotti (1999: 27-46). These questions are also addressed by au-thors such as Floya Anthias, Philomena Essed,Helma Lutz, Nira Yuval Davis or Avtar Brah.

T

HE

C

HALLENGE

OF

C

ULTURAL

D

IVERSITY

IN

E

UROPE

51

H

UMAN

A

RCHITECTURE

: J

OURNAL

OF

THE

S

OCIOLOGY

OF

S

ELF

-K

NOWLEDGE

, IX, 4, F

ALL

2011

“Diferentes, desiguales y desconectados.Mapas de la interculturalidad” [“Different,Unequal and Unconnected: Maps of Inter-culturality”], noting that

…the identities of subjects areformed today in inter-ethnic andinternational processes, throughflows produced by technologiesand multinational corporations,globalized financial exchanges,repertoires of images and informa-tion created in order to be distrib-uted throughout the planet by thecultural industries. Today weimagine what it means to be sub-jects not only from the standpointof the culture into which we wereborn but also from the standpointof an enormous variety of symbolicrepertoires and models of behaviorthat we can cross-breed and com-bine. (García Canclini 2004:161)

A billboard slogan that greeted stroll-ers along the Rambla Nova of Tarragona

2

carried the following warning: “May thecolor you desire for your skin not becomeyour cross to bear.” It made evident a newreality that went beyond the canons ofbeauty. Today we wish to have tanned skinby lying on the beaches of the CostaDorada; we no longer need the hats andwide sunhats

worn earlier by the women ofthe aristocracy and the bourgeoisie. In spiteof this, the golden skin of the Muslim girl(with the icon of religious affiliation, the

hijab

or headscarf) is seen as a representa-

tion of her cultural difference and serveshere as a reason to refuse discourses basedon xenophobia and cultural racism (MartínMuñoz 2005).

The presence of immigration fromoutside Europe, and Muslim communitiesin particular, makes evident this symbolicnegation that continues to operate in ourcollective imaginary, whether we defineourselves as coming from a certain reli-gious culture or as being secular or agnos-tic. It provokes us to redefine ourhistoriography in order to see others inorder to know ourselves better. As GarcíaCanclini has written:

In times of globalization, the mostrevealing object of study and theone which most questions ethno-centric or disciplinary pseudo-cer-tainties, is interculturality. Thesocial scientist, through empiricalinvestigation of intercultural rela-tions and the self-reflective critiqueof disciplinary fortresses, attemptsto think from the position of exile.To study culture thus requiresturning oneself into a specialist ofintersections. (García Canclini2004:101)

II. I

NTERCULTURAL

D

IALOGUE

AND

C

ULTURAL

P

OLICIES

IN

E

UROPE

As a reflection of this situation, andfrom a perspective of seeking new attitudesand confronting new challenges, UNESCOdedicated the year 2008 to the defense ofcultural diversity and interculturaldialogue. Emphasis was placed on imple-menting the Convention on the Protectionand Promotion of the Diversity of CulturalExpressions, which was approved in Parison October 20, 2005, and came into effect onMarch 18, 2007. As the UNESCO websitestates:

2

The “Rambla Nova” is the main street ofthe city of Tarragona. According to indices of thenumber of immigrants as of January 1, 2006 inthe province of Tarragona, there were 105,211persons of foreign nationality in the province ofTarragona, or roughly 14.3% of the total popula-tion. This percentage is higher than the overallpercentage for Catalonia—13.1%—and for theprovince of Barcelona, 12.4%. See Gregorio Viz-caíno,

La población extranjera en Tarragona. Presen-te y evolución histórica

, Fundación Bofill, 2007.

52 E

STELA

R

ODRÍGUEZ

G

ARCÍA

H

UMAN

A

RCHITECTURE

: J

OURNAL

OF

THE

S

OCIOLOGY

OF

S

ELF

-K

NOWLEDGE

, IX, 4, F

ALL

2011

the main objective of the conven-tion consists of creating an evermore interconnected world, an en-vironment that allows all culturalexpressions to manifest themselvesin their creative richness, to reno-vate themselves through exchangeand cooperation, and to be accessi-ble to all for the benefit of all hu-manity. (http://www.unesco.org)

Our interconnected world of the begin-ning of the 21

st

century is also a discon-certed world

.

Economic and culturalglobalization requires us to face new chal-lenges which make visible the fragility ofcertain societies in the face of the rapidity ofcommunications. Among the studies thatclarify these issues the most is the work bycommunication specialist Armand Matte-lart,

Diversité culturelle et mondialisation

.Mattelart points out the difficulty of formu-lating stable definitions of terms in an era ofglobalization, especially in the area ofculture

(2006:93). He reminds us that theUNESCO convention is the fruit of a longprocess that began in 1982 with the WorldConference on Cultural Policies in Mexico,during which the basic terms of a culturalpolicy based on the recognition of diversitywere formulated:

A policy which, by defining as itsobjective the development of cre-ative faculties, both individual andcollective, no longer limits itself tothe area of the arts but is extendedto other forms of invention (…).Nonetheless, 20 years had to go bybefore a new configuration of ac-tors tried to convert this abstractprinciple into a practical juridicalinstrument capable of removing“cultural expressions” from theuniform logic of commodities.

Economic rules and cultural onesevolve at different rhythms. The rhythm of

artistic and cultural expressions of minori-ties not included in the hegemonic forms ofcultural production and reproduction isone that manifests itself outside thesecultural circuits and creates others. JoostSmiers stresses this idea in his excellent andprovocative study

Un mundo sin copyright.Artes y medios en la globalización

[“A worldwithout copyrights: Art and media in acontext of globalization”] (Smiers2006:257), in which he speaks of a democ-racy that prospers when the viewpoints ofminorities too are able to play a key role insocial and cultural life. He writes: “Manyartistic expressions are not taken intoaccount in public debates over taste,language, design, musical genres, theatre,and the narrative structure of films or tele-vision programs. And this represents a lossfor democracy.”

The “European Year of InterculturalDialogue” was proclaimed with the objec-tive of calling attention to the dialogueamong cultures as a matter of priority inEurope, given the challenges of globaliza-tion, and seeking the joint participation ofgovernmental actors and civil society. Inthe aim of adapting this dialogue to theenvironment of the Spanish state, RoyalDecree 367/2007 of March 16, 2007 createdthe “National Commission for the Encour-agement and Promotion of InterculturalDialogue,” charged with reflecting on

… the cultural diversity that de-rived from the successive enlarge-ments of the European Union, themobility resulting from the singlemarket, migratory flows and ex-changes with the rest of the world.Today it is a reality of our societies,which require adequate decision-making for Europe and for Spain.Since culture is a factor of social in-tegration and the development ofcitizen identities, promoting andfacilitating intercultural dialogueas a declared priority contributes

T

HE

C

HALLENGE

OF

C

ULTURAL

D

IVERSITY

IN

E

UROPE

53

H

UMAN

A

RCHITECTURE

: J

OURNAL

OF

THE

S

OCIOLOGY

OF

S

ELF

-K

NOWLEDGE

, IX, 4, F

ALL

2011

to social cohesion and the accep-tance of different cultural identitiesand beliefs within European citi-zenship. From this perspective, in-tercultural dialogue is a factor ofgrowth and quality of life and wemust invite European citizens andall those who live in the EuropeanUnion to take part in the manage-ment of this cultural diversity.

3

In this spirit, many other authorsadvise us of the ever more important role ofconcept of culture and its necessary conver-gence with that of diversity. The Frenchsociologist Alain Touraine stresses that thenew century is defined by the rise of whathe calls the new “cultural paradigm”(Touraine 2006). Other approaches, such asthat of the anthropologist Arjun Appadu-rai, bring to light the fact that these newchallenges require some profound changesin perception in order to allow for culturalpluralism that is sustainable over time,dynamic and without preconceived limits:

The term cultural diversity speaksof the coexistence of groups of dif-ferent cultural identities. This coex-istence must have sufficientlongevity, security and sustainabil-ity to allow the identities in ques-tion to produce themselves. For acultural identity to be more than aslogan, it must evolve over time ina creative way and, given that therelations among groups are alwaysevolving, the challenge is how toguide this evolution in a creativeand sustainable way. (Appaduraiand Stenou 2000:111-123)

With these words we enter discussionsthat are gaining more and more ground. Inrecent years terms such as “cultural rights”

and “cultural citizenship” have gainedmore strength. From this perspective, acultural right is defined as “the right to takepart in the cultural life of a city.”

4

ArjunAppadurai encourages us to reclaim theradical character of this concept (Appadu-rai y Stenou 2000:111-123):

The very idea of

cultural rights

rep-resents a radicalization of liberalsocial theory and goes significantlybeyond the ideas of tolerance andrecognition. It recognizes that theright to culture in daily life is fun-damentally political and requires asignificant level of autonomy, legal,juridical and spatial. It imposes onthe states the obligation to providespaces of cultural expression. Themost radical form of this concep-tion gives rise to

cultural citizenship

,which requires, in reality, the vol-untary sharing of state power re-garding law, language andterritory.

To give autonomy to cultural and artis-tic expressions of immigrant communitiesand ethnic minorities of a given statewould involve a great Copernican changein the new century: the creation of acultural citizenship. I think this wouldcause cultural minorities and the state to besituated in a common cultural space, inwhich citizenship would have to be re-signified through the concept of difference.Other voices in Europe have echoed this

3

Real Decreto [Royal Decree] 367/2007. Seehttp://www.mcu.es

4

Article 27 of the Universal Declaration ofHuman Rights. The Interarts Foundation, in col-laboration with UNESCO and the AECI, organ-ized the

Diálogo sobre Derechos Culturales yDesarrollo Humano

[Dialogue on Cultural Rightsand Human Development] in the framework ofthe

Forum de las Culturas

of Barcelona in2004. They developed an interesting question-naire on the subject, with the aim of gaining aclearer vision of perceptions, at the regional, lo-cal and individual level, of cultural rights andthe role of culture in development. See http://www.interarts.net

54 E

STELA

R

ODRÍGUEZ

G

ARCÍA

H

UMAN

A

RCHITECTURE

: JOURNAL OF THE SOCIOLOGY OF SELF-KNOWLEDGE, IX, 4, FALL 2011

idea. Among them is the journal Eurozine,5

whose web page contains a text that readsas follows:

The concept of cultural citizenshipresponds to the development of thecentrality of cultural productionand consumption as necessary ele-ments for benefiting from therights of citizenship. Cultural citi-zenship is thus not assimilable tothe concept of nationality, assimila-tion or tolerance but, rather, moreclosely related to the notions of rec-ognition and empowerment. Thisconcept is a vital instrument for therethinking of identity and differ-ence, and more specifically for con-ceptualising a Europe in whichattention to political and socialrights includes a full recognition ofminority groups and cultural di-versity.

This new Europe would not onlyrecognize the cultural diversity that existsin its states (that is, their internal diversityand that which originates from immigra-tion) but would also promote dialoguewith the countries around it, in particularthose of the Mediterranean. The attempthas been made to maintain such a climateof debate in Catalonia since the signature in1995 of the so-called “Process of Barce-lona,” dedicated to developing differentinternational discourses on these new atti-tudes toward the phenomena of immigra-tion and cultural globalization.

The debates on cultural diversity in oursocieties will necessarily become a resourcein the early part of this century, defined asit is by fragmentations, fissures and a senseof the ephemeral, and interested as it is inmaterial and immaterial heritages—thatwhich is fleeting and fragile and must be

preserved and protected. The culturalecosystem needs attention and spaces ofexpression, just as if it were a naturalresource. As Smiers has stated (2006:17),cultural diversity and biodiversity will betwo major social movements in the 21st

century, since “economic globalization ofthe contemporary world does not guaran-tee the persistence of the cultural legacies towhich we are heirs.” The delicate balance ofthe cultural ecosystem needs a movementin which culture becomes conscious of itsprecarious state in the face of the laws ofeconomics and consumption and developsnetworks that create alliances in local,regional and global settings.

III. CITIES THAT EDUCATE: BREAKING DOWN THE WALLS OF EDUCATIONAL POLICY AND CULTURAL AGENDAS

In the international context we havejust described, cities take on a renewedimportance in many cultural and educa-tional discourses (Mascarell 2005). Theytake on a new role in nascent societies, inthe midst of a full-scale crisis of hegemonicnation-states. The society emerging fromthe new social and technological transfor-mations of globalization becomes volatile,permeable and changing—or, as Baumansays, “liquid” (Bauman 1999). GarcíaCanclini situates this phenomenon whenhe speaks of places and identities thatchange quickly in times of globalization:

What is a place in globalization?Who speaks, and from where?What is the meaning of these con-tradictions between games and ac-tors, military triumphs andpolitical-cultural failures, world-wide dissemination and creativeprojects? The fascination of beingin all places and the unease of notbeing with certainty in any, of be-

5 Eurozine (http://www.eurozine.com),June 30, 2007.

THE CHALLENGE OF CULTURAL DIVERSITY IN EUROPE 55

HUMAN ARCHITECTURE: JOURNAL OF THE SOCIOLOGY OF SELF-KNOWLEDGE, IX, 4, FALL 2011

ing many and none—all thischanges the terms of the debateabout the possibility of being sub-jects. (García Canclini 2005:25)

An example of this new role of munici-pal policies was the creation of the“Agenda 21 de la Cultura,” promoted bythe Ayuntamiento [city government] ofBarcelona in the framework of the ForumUniversal de las Culturas [UniversalForum of Cultures] of 2004, and approvedon May 8, 2004, with the celebration of theIV Foro Autoridades Locales [4th Forum ofLocal Authorities]. The intention of thisdocument was to promote the commonefforts of cities and local governments on aworld scale that were committed to humanrights, cultural diversity, sustainability,participatory democracy and the creationof conditions for peace. It sought indeed tobe the first document with a worldwidevocation seeking to establish the bases of acommitment of cities and local govern-ments to cultural development. In order toassume this ambition, it proposed that May21st of each year be celebrated as the World-wide Day of Cultural Diversity. As it stressedon its website:

In many parts of the world it maybe observed that many problems ofcities have to do with the relation-ship between culture and humandevelopment: linguistic and cultur-al rights of (so-called) minorities,struggles against poverty, migra-tions… In this context, many solu-tions call for giving cultural policya more central role in local govern-ment (…). Concepts that belong tothe world of cultural policy, such asmemory, creativity, rituality or di-versity, are now more essential thanever, in order to define local policiesthat are in the service of democracyand a freer form of citizenship.(http://www.agenda21culture.net)

The importance of local administrationis also recognized in the area of education,shifting the outlook from the start towardways of transmitting knowledge in a globalworld. The network of municipalities of theDiputación [provincial council] of Barcelonadedicated its most recent symposium onlocal educational policies to reaffirming therole of cities in all aspects and stages ofknowledge. “Ciudad.edu: nuevos retos,nuevos compromisos” [“City.edu: new chal-lenges, new commitments”], celebrated inOctober 2006, sought to concentrate onevaluating the adaptation of educationalmodels to social change and makingservices adequate to emerging needs andrealities—among them, making culturaldiversity a serious and visible priority. Therole of local administration in addressingthis objective was underlined:

Municipalities are one of the mainactors in education policy, since itis on a territory that all agents ofthe educational system come intocontact and that proximity takes onall its value (…). We begin with thestrong conviction that territory isan actor of education which, whentightly enmeshed with the schoolsystem, causes the borders be-tween formal and informal educa-tion to fade and fulfils its potentialthereby. In this sense, the [local] en-vironment must facilitate the car-rying out of strategies and beendowed with resources for thefulfilling of its educational func-tion, taking into account as wellthat community space is one of theelements that best helps to definetheir own identity.6

6 Dossier of the convention “Ciudad.edu:nuevos retos, nuevos compromisos,” World Tra-de Center, Barcelona, October 9-11, 2006. Specialnote should be taken of the session dedicated tothe revision 10 years later of the Delors Report,at which Federico Mayor Zaragoza was present.

56 ESTELA RODRÍGUEZ GARCÍA

HUMAN ARCHITECTURE: JOURNAL OF THE SOCIOLOGY OF SELF-KNOWLEDGE, IX, 4, FALL 2011

From now on, schools and cities mustbe permeable and must cooperate in devel-oping the cognitive processes of pupilsfrom the beginning and understand thatcontemporary knowledge society ispreparing a world that is ever more inter-connected, in which cultural and commu-nity referents take on more importance. Therelationship between school and familycomes into new relief in the context of thisnew attention paid to social cohesion andthe relation between school and environ-ment, between education in a given territo-rial space which is no longer simply aphysical territory but also symbolic andexpanded through connections with themedia such as internet or television.Schools break down walls by recognizingthat they are not the only way in whichpupils form a consciousness of their identi-ties. The old school walls are now paintedwith new graffiti which speak to us of theimportance of youth and urban culture,and which claim their space for theconstruction of identities that are shaped inmultiple ways, via a broad spectrum ofsymbolic, visual and virtual resources.They manifest themselves rapidly and inchanging ways, since the hybridization ofcultural identities is imperceptible or, asAppadurai has written:

In an era when cultural groupsmay change their styles, when newgroups arrive suddenly and disap-pear unpredictably, when youngpeople revise their identities at diz-zying speed, when cultural identi-ties may change or realign, bothexternally and internally (…), theconception of cultural pluralismmust be strictly directed towardthe present. This will require theimagination of ordinary people tobe agile and thus open to new re-gimes of diversity. (Appadurai andStenou 2000:111-123)

The approach to cultural diversity andto the different cosmologies of the culturesthat make up immigration from outside theEuropean Community, present today in ourclassrooms, implies that we must take intoaccount the inclusion of these practices as atool of intercultural communicationbetween immigrant pupils and native ones.The Basque educator Imanol Agirrementions this idea in his work on “Teoríasy prácticas en educación artística” [Theo-ries and practices of artistic education]:

The new times are characterized bya growing tendency toward a re-spect of difference, indeed a cult ofdifference, which should not con-stitute an obstacle to human rela-tions. In education above all,attention to diversity (be it cultur-al, social or biological) is one of themain principles of politically cor-rect and democratic education. In-deed, no one doubts that humanity,far from being a homogeneouswhole, is a broad mosaic of ethosand world views, a plurality ofmanners of seeing the world thatcorresponds to a great variety ofmodels of social configurations,systems of values, habits and cus-toms and cultural productions(Agirre 2005:293).

IV. CLASSROOMS AND MUSEUMS FACING CULTURAL DIVERSITY: THE MUSEUM OF THE HISTORY OF IMMIGRATION OF CATALONIA

From the standpoint of the responsibil-ity of informal education toward culturaldiversity, museums too are raising ques-tions about their collections, asking whatversion of history they are transmitting viatheir educational workshops which nowinclude pupils from different cultural heri-tages and traditions (Calaf 2007). As we

THE CHALLENGE OF CULTURAL DIVERSITY IN EUROPE 57

HUMAN ARCHITECTURE: JOURNAL OF THE SOCIOLOGY OF SELF-KNOWLEDGE, IX, 4, FALL 2011

have seen, this discussion has little by littletaken on more importance at the local,national and international level.7 Referenceis often made to an issue of the UNESCOjournal Museum International dedicated tothe cultural heritage of immigrants.8 Theissue speaks of the creation of new muse-ums of immigration and the attentioncurrently given to migratory processes. Itintroduces the debate on the necessity ofdeconstructing negative perceptions aboutthe role of immigrants in contemporarysocieties and of implementing cultural andeducational policies that interact constantlywith society, aimed at promoting a non-stereotypical vision of their culturalresources in order to stake out the path of acommon history in today’s world. In itspages the issue further points out thatattention to the cultural heritages of immi-grants demonstrates the specific role ofculture in processes of development—a keytheme in UNESCO’s work in recentdecades. The ultimate goal would be torecreate a cultural heritage that includesthe artistic practices of immigrant commu-nities in order that these too may becomecultural referents for the entire society.

For this very purpose we organized in2006 the exhibit, commissioned by theMuseum of Immigration of Catalonia9 andthe Museum of Hospitalet, a suburb ofBarcelona, on the associations of immigrant

women in Catalonia. In search of a title forthe exhibit, we chose the following one:“Viajando vidas, creando mundos. La experien-cia y la obra de las mujeres migradas en Cata-luña” [“Traveling lives, creating worlds.The Experience and the Works of Immi-grant Women in Catalonia”], whichemphasized the agency of these womenand the magnitude of their experiences.10

The exhibit had the support of theDiputación of Barcelona and it travelled tovarious museums belonging to the networkof local museums of the metropolitan areaof Barcelona. The museographic projectwas centered on bringing out the historicalaspect of the diasporic migrations and theirgeographical and cultural origins, but itstressed in particular the processes ofconstruction of new identities in the desti-nation cities and the agency and empower-ment of these women through theirmanagement a diverse array of associa-tions. In the effort to express the culturalquestions that each woman carries with herwhen she travels, as if they were a suitcase,special importance was given to the prac-tices of cultural and artistic production, tothe symbolic production that becomes re-signified in the destination city. As we haveemphasized in this article, the processes ofcreation in exile or in diaspora manifestthemselves as a series of values of differentcharacter: the transit, the voyage, thediaspora, needs new forms of expressionand new creative impulses—new workswith new languages for new spaces with adifferent public, new contexts and newpretexts for artistic creation which does notstop because of these conditions. The artistsinvited to expose their work in the exhibitshowed how this symbolic productionbecomes an enriching contribution that ishardly visible in the media and barelypresent in the city’s museums of contempo-

7 This debate is still incipient but ever morepresent in museological contexts. See, for exam-ple, the “IV Jornadas de Pedagogía del Arte yMuseos” [Days of Art and Museum Pedagogy]organized by the Museo de Arte Moderno(Modern Art Museum) of Tarragona and dedi-cated to the theme of “museums and educationfor cultural diversity from the arts,” April 18-25,2007, Tarragona.

8 Museum International no. 233-4, May 2007. 9 This museum was founded in 2004 in Sant

Adrián del Besós, Barcelona and is dedicated tothe expression of the historical memory of inter-nal migration (that is, originating from other re-gions of Spain) as well as extra-Europeanmigration. It seeks to contextualize discourseson migrations and what these represent in theconstruction of new common identities.

10 The exhibit was commissioned by theGuinean Remei Sipi, president of the associationE’waiso Ipola, an association of women of Equa-torial Guinea.

58 ESTELA RODRÍGUEZ GARCÍA

HUMAN ARCHITECTURE: JOURNAL OF THE SOCIOLOGY OF SELF-KNOWLEDGE, IX, 4, FALL 2011

rary art. Their works used the most variedmediums of expression—such as contem-porary dance, theatre, audiovisual media,painting, sculpture, literature, photogra-phy—and turned themselves into surpris-ing instruments of communication andsocial cohesion.11 They constitute materialsof great worth that open new and positivemeanings, far from stereotyped images,and show us very compelling life storiesand professional paths. They speak of theneed to visualize one’s cultural heritage,present in all societies although it is oftenunrecognized. But they further placed onthe table the need to transform these collec-tive imaginaries into a common andrenewed heritage, in a Europe that recog-nizes both its internal diversity and thatwhich comes from extra-European migra-tion, providing it with places of expressionin its cities, its classrooms and its museums.

V. IN CONCLUSION: BRUSHSTROKES FOR A DEBATE WITHOUT LIMITS

The cluster of concepts in circulation inthis early part of the century mobilizes allour attention and capacity for understand-ing: diversity, citizenship, democracy,rights and law, tourism, cooperation, theecosystem—all these need to be morecultural than ever. Cultural and liquid, inthe sense of permeable and flexible, for theconstruction of a sustainable pluralism thatgoes beyond consensual discourse, pleas-ant words and images, which too often turninto sand that slips through our fingers.The consciousness of cultural diversity inour cities, regions and countries tells us as

well, as we have seen, of our genealogiesand heritages—cultural, social, family andpersonal. We always project a potential forutopia on the coming generations and thatis why we attribute great importance toeducation, but the rapidity of the changeswe are living through must now lead us torethink these heritages starting from thepresent moment, from the very second weare consuming.

REFERENCES

AGIRRE, Imanol. Teorías y prácticas en EducaciónArtística. Barcelona: Octaedro/EUB, 2005.

ANDERSON, B. Comunidades imaginadas, Reflex-iones sobre el origen y la difusión del naciona-lismo. México: Fondo de CulturaEconómica, 1993 [original English ver-sion published in 1983].

APPADURAI, Arjun; STENOU, Katerina. “Elpluralismo sostenible y el futuro de lapertenencia,” in Informe Mundial de laCultura. Diversidad cultural, conflicto y plu-ralismo, Madrid: Ediciones Mundi/Prensa/Ediciones UNESCO, 2000.

ARAYA, Mariel; RODRÍGUEZ, Estela. “Bus-cando habitar la ciudad. El reto de lavivienda para las mujeres inmigradas enMadrid y Barcelona,” in Scripta Nova.Revista electrónica de geografía y cienciassociales. Barcelona: Universidad de Barce-lona, August 1, 2003, Vol. VII, no.146(062). http://www.ub.es/geocrit/sn/sn-146(062).htm

BARKAN, Elazar; DENISE, Marie; Borders,exiles, diasporas. Stanford, California:Stanford University Press, 1998.

BAUMAN, Zygmunt. Modernidad líquida. Bue-nos Aires: Fondo de cultura económica,1999.

BRAIDOTTI, Rosi. “Figuraciones de nomad-ismo. Identidad europea en una perspec-tiva crítica” in DE VILLOTA, Paloma(eds.). Globalización y género. Madrid: Sín-tesis, 1999.

CALAF, Roser; FONTAL, Olaia; VALLE, Rosa(coords.). Museos de arte y educación. Con-struir patrimonios desde la diversidad. Gijón: Trea, 2007.

CARBONELL, F i AJA, E., Educació i immigració:els reptes educatius de la diversitat. Barce-lona: Ed. Mediterránea, 2000.

11 Name of the immigrant women’s artistsin Catalonia: Margarita Pineda y Consuelo Bau-tista (Colombia); Samira Badrán (Palestine); XiaHang (China); Motoko Araki (Japan); NiloufarMirhadi (Iran); Jéssica Leung (United States);Natividad Oma, Montse Kondo, Paquita Belobe(Equatorial Guinea); Luz Cassino, Guigui Ko-hon, Paula Mariani (Argentina); Karel Mena(Venezuela).

THE CHALLENGE OF CULTURAL DIVERSITY IN EUROPE 59

HUMAN ARCHITECTURE: JOURNAL OF THE SOCIOLOGY OF SELF-KNOWLEDGE, IX, 4, FALL 2011

CHAKRABARTY, Dipesh. ProvincializingEurope. Postcolonial Thought and HistoricalDifference. Princeton and Oxford: Prince-ton University Press, 2000.

CHALMERS, F. G. Arte, educación y diversidadcultural. Barcelona: Paidós, 2003.

Colectivo IOE. Inmigración, género y escuela.Exploración de los discursos del profesorado yel alumnado. Madrid: CIDE Ministerio deEducación y Ciencia, 2007.

ESSOMBA, M.A. SANDUK. Guia per a la for-mació dels educadors i educadores en inter-culturalitat i immigració. ProgramaCalidoscopi. Barcelona: Secretaria Generalde Joventut-Fundació Jaume Bofill, 2001.

ESSOMBA, M.A. Construir la escuela intercul-tural. Reflexiones y propuestas para trabajarla diversidad étnica y cultural. Barcelona:Editorial Grao, 1999.

GARCÍA CANCLINI, Néstor. Diferentes,desiguales, desconectados. Mapas de la inter-culturalidad. Barcelona: Gedisa Editorial,2004.

GARCIA, José Luis; BARAÑANO, Ascensión(coord.) Culturas en contacto. Encuentros ydesencuentros. Madrid: Museo Nacionalde Antropología-Universidad Com-plutense-Ministerio de Educación, Cul-tura y Deporte, 2003.

HERNÁNDEZ, Fernando. Educación y culturavisual. Barcelona: Octaedro-EUB, 2003.

MARTÍN MUÑOZ, Gema. “Mujeres musulma-nas: entre el mito y la realidad” inCHECA, F. (eds.), Mujeres en el camino. Lapresencia de la migración femenina enEspaña. Barcelona: Icaria, 2005.

MASCARELL, Ferran. La Cultura en l'Era de laIncertesa. Societat, Cultura i Ciutat. Barce-lona: Roca Editorial, 2005.

MATTELART, Armand. Diversidad cultural ymundialización. Barcelona: Paidós Comu-nicación, 2006.

MIGNOLO, Walter. Historias locales/diseños glo-bales. Colonialidad, conocimientos subalter-nos y pensamiento fronterizo. Madrid: Akal,2003.

MUSEU D’ART MODERN DE TARRAGONA(MAMT). El museu i l’educació per a ladiversitat cultural de les arts. Tarragona:Diputació de Tarragona, 2008.

PAJARES, Miguel. La integración ciudadana. Unaperspectiva para la inmigración. Barcelona:Icaria, 2005.

RODRIGUEZ, Estela, “Ciudades intercul-turales: una ventana a la diversidad cul-tural a través de las artes y la culturavisual” in Migraciones y mutaciones cul-turales en España. Sociedades, artes y liter-aturas. Ed. MIAMPIKA, Landry-Wilfrid;

VINUESA, Maya G.; LABRA, Ana &CAÑERO, Julio. Alcalá de Henares: Pub-licaciones de la UAH, 2007.

RODRÍGUEZ, Estela. “Mujeres inmigradas ymedios de comunicación. Movimientossociales en búsqueda de una represent-ación propia” in CHECA, F. (eds.),Mujeres en el camino. La presencia de lamigración femenina en España. Barcelona:Icaria, 2005

RODRÍGUEZ, Estela. “Políticas (inter)cul-turales en Barcelona. El teatro lati-noamericano en la ciudad,” pubished inRevista de Arte y Cultura en América Latina,CESA- Sociedade Científica de Estudosda Arte, Brasil (Volume XII, no. 1, 2004)

SHOHAT, Ella; STAM, Robert. Unthinking Euro-centrism. Multiculturalism and the Media.London: Routledge, 1994.

SMIERS, Joost. Un mundo sin copyright. Artes ymedios en la globalización. Barcelona:Ed.Gedisa, 2006.

TOURAINE, Alain. Un nuevo paradigma para elmundo de hoy. Barcelona: Paidós, 2006.

VIZCAINO, Gregorio. La població estrangera aTarragona. Present i evolució històrica. Fun-dació Bofill, 2007.

WALKER, John A.; CHAPLIN, Sarah. Una intro-ducción a la cultura visual. Barcelona:Octaedro-EUB, 2002.