Taiwan Coming of Age

Transcript of Taiwan Coming of Age

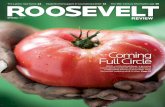

A tearful Chinese civil war veteran holds a portrait of Chiang Ching-kuo upon hearing the news of the president’s death, 13th January 1988. (Photography by Hsia San)

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 2 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:24

3

Taiwan Coming of Age

David Blundell

All serious daring starts from within. Joan Baez

History is often elusive, reliant as it is on the vagaries of documentation and fickle memory. It is not what it seems—and new evidence changes out the old. Events of the ‘conjectured past’ are the matrix of the social consciousness and heritage that create the present. The time frame and happenings of this chapter derive from vignettes of my experiences in Taiwan from the end of martial law to its current democracy. I will introduce a political debate, the rise of environmental action, conceptualization of local world heritage sites based on international guidelines, and eco-cultural traveling seminar interac-tions for developing a perception of Taiwan with its sense of place.

The people of Taiwan have chosen democratization from the mid-20th century. Public mobilization incubated within a climate of social frustration with abbreviated civil liberties, environmental degradation, and a govern-ment working officially toward the goal of saving China. By the 1960s and 1970s, a grassroots ‘consciousness of polity’ emerged agitating through the folksong movement (minge yundong 民歌運動)1 of university campuses and

1 Minge yundong is the gloss for the ‘campus folk song movement’ in Taiwan from the 1970s to 1980s. Its inspiration in part came from the songs of Woody and Arlo Guthrie, Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and Janis Joplin. In 1967 at Tamkang University in Tamsui,

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 3 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:24

4 Taiwan Coming of Age

freedom rallies in Kaohsiung,2 cumulating in the 1980s with popular rallies at the Presidential Office and National Assembly in Taipei.

In this emerging quest for liberties, the government of Taiwan came to honor the people’s will. This was recently discussed by Ho Ming-sho (2010) who divides the past 65 years in Taiwan into three phases: (1) the 15 year period of authoritarian repression of the population to ensure rule of the Republic of China (ROC) government from the end of the Second World War in 1945 to 1960, (2) the United States aid period that sustained economic development and industrialization through the 1960s and 1970s, and (3) the popular social movements for political liberalization that led to democrati zation giving Taiwan a heartfelt sense of local identity from the 1970s–1980s to the present (also see Hsiao 1990; Reardon-Anderson 1993; Gold 1994; Hsieh 1994; Tang and Tang 1997; Fell 2010). In 1987, a rapid shift from martial law began honor-ing the people’s right to govern themselves and decide their future. Taiwan transformed itself from military rule to a vibrant democracy. As the people of Taiwan have continued their democratization, their review of the island’s heritage became a guide for current determination.

Underlying some of the social, economic, and political disagree ments that separate people in planning for the future are differing assumptions about the extent to which “free will” and “determinism” shape the unfolding of human affairs (North 1976: 81).

In Taipei during the 1980s, I witnessed the unfolding of democratization. The first public debate between the established Nationalist Party (Kuomin-tang, KMT) and the newly formed Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)

Li Shaun-je (李雙澤) asked, “Where are our own songs?” With such inspiration Hu De-fu (胡德夫) also known as Kimbo, along with Hong Xiao-qiao (洪小喬) and Yang Guo-xiang (楊國祥) in the mid-1970s set a trend of poetic lyrics with meaning for the people of Taiwan. At first the music was suppressed under martial law, yet the popu-larity of these Mandarin and local language songs gained momentum among univer-sity students and a newly developing middle class which the government could not ignore.

2 The Meilidao Incident (美麗島事件) occurred on 10th December 1979 when a pro-democracy rally clashed with the police in Kaohsiung on Human Rights Day.

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 4 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:24

David Blundell 5

was held at the Bankers Club, Taipei, in the early 1990s. Michael Jaliman,3 among others, organized the event as an information session for the Taiwan international community. It was agreed upon in advance that the debate be conducted in English so that the international resident community could better understand the contending political views. The choice of language was a debate condition of the KMT for publicly communicating with its newly legalized political rival. During the debate, each party insisted that it alone was the better choice for the people of Taiwan. The DPP accused the KMT of seizing control of the island and ruling as an authoritarian mainland-Chinese party for the eventual benefit of China, not Taiwan. In response, the KMT contended to have preserved Taiwan as an independent entity since 1949, safe from the takeover of Communist China. Both sides positioned themselves to convince the audience that they alone were working to ensure public safety and economic growth of Taiwan. This event was broadcast by cable televi-sion (illegal at the time) and reported in a few newspapers in second, or third page columns, the following day. Then historically the debate evaporated—remaining only in the memories of those in attendance.

As I was attending, it was refreshing for me to observe the debaters of the KMT defending their position on Taiwan. At the time, for the Nationalists to localize Taiwan politics as championed by the DPP was a betrayal to Chinese people. Now with an opposition party to contend with, KMT debaters cir-cumvented the DPP by boldly stating that it had secured independence for the island since 1949. This trump over the DPP ‘independence platform’ was astonishing—a momentary breathlessness of the audience. Suddenly the DPP panelist himself became wide-eyed in disbelief—becoming anxious, unable to speak. How could the KMT make the claim of originating an ‘independent Taiwan’? Of course this statement did not circultate among the general public. Indeed, the KMT management of government represented the defense and security of the people in terms of pursuing their economic growth and mod-ernization safe from the destructive Cultural Revolution in China. The KMT positioned itself as a national custodian and guardian of cultural heritage—

3 Mr Jaliman was living in Taipei as a representative of the Swiss-based company KPMG —an international professional network of firms that offer audit, tax and advisory services. Website, https://www.kpmg.com

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 5 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:24

6 Taiwan Coming of Age

giving the impression that DPP politicians were radical firebrands, untested, and lacking the administrative skills to lead the country.

In 1911, the revolutionary Chinese Nationalist Party of Dr Sun Yat-sen ushered in the republic to end the Qing dynasty. After the Second World War, the Nationalists persisted in defending their right to implement a modern democracy with their 25th December 1946 Nanjing ROC Constitution for civil administration as the bona fide guiding instrument of the people. The government relocated from Nanjing to Taipei in 1949 as the legitimate authority of China, not in exile—as it remained on its claimed territory. By the 1980s, to remain current with the times, the ruling party had to review its policy of governance.

After reaching for support among local Taiwan grassroots groups for its political constituency, along with its greater China future goals, the KMT had to work at balancing diverse viewpoints. At the time, the government’s emergency laws for national security were considered outdated. These laws included prohibitions such as coastal no-entry zones, public bridges not to be photographed, and military police jeeps on street patrol starting from 10:00 pm to guard against assemblies without permission. Martial law was becoming wearisome to people who viewed the government as an oppressive authority working for the salvation of ‘Free China’. Recognizing their Chinese heritage as worth upholding and preserving, the Taiwan people were not against China per se. Many people in Taiwan were proud they served as the bastion and savior of Chinese culture, which was undergoing traumatic change in China. However the Taiwanese did not want to be politically subor-dinated for the sake of historical linkages.

During for the years since martial law, a Taiwan heritage movement has been underway as the people search for their own identity. It has been at the forefront of public attention with the building of museums, cultural centers, and staged art events reminding us that ‘where people live’ is the basis of our political consciousness. Cultural institutions have developed that offer venues set in localities that communicate landscape character-istics and styles of ethnic groups who live there (Blundell 2009: 411–416).

For example in 2010, the Lanyang Museum of Yilan County opened its doors to the public featuring massive slanted stone and glass walls mirroring

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 6 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:24

7

Lanyang Museum initiated by Lu Li-cheng4 and completed after 19 years of preparation in 2010, Yilan County. Its theme of ‘symbiosis with nature and architecture’ was conceived by Kris Ren-xi Yao. Website, http://www.lym.gov.tw (Photography courtesy of David Blundell)

the appearance of the Northeast Coast’s tectonic plate uplift of cuesta layered rock. It was built on the edge of wetlands and a fishing-boat harbor along the Beiguan Coast. It integrates the local environment with living society—con-ceptually designed for niche heritage embraced in world-class architecture.

[Our] planet has become an intricate convergence—of acid rains and rain forests burning, of ideas and Reeboks and stock markets that ripple through time zones, of satellite signals and worldwide television, of advance-purchase airfares, fax machines, the mini-aturization of the universe by computer, of T-shirts and mutual destinies … the village has indeed become global—Marshall McLuhan was right.

No island is an island anymore: the earth itself is decisively the island now (Morrow 1989: 41).

4 Lu Li-cheng is the director of the National Museum of Taiwan History, Tainan. It opened in Tainan after 12 years of preparation, 29th October 2011.

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 7 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:25

8 Taiwan Coming of Age

McLuhan (1964) envisioned a world becoming an interlinked village spanning multiple time zones. The transmission of societal, political, and eco-nomic information was envisioned to become practically instantaneous, as it is today. For example during the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, the Olympic theme song featured the Taiwan indigenous voices of the Amis elders. They were not invited to attend, nor acknowledged. Yet the local Taiwan people heard their indigenous song resound worldwide in Enigma’s “Return to Innocence” at the top of the music charts. It was a sign of the internationaliza-tion of their unacknowledged local heritage from the village to the world (see Anderson 2009). Once the song was celebrated globally, the vocalists and the culture that had produced it became instantaneously valued back home.

As the Internet becomes part of how people conduct themselves, heri-tage revitalization is likewise placing its demands on this medium. Just as archaeologists are facing the challenge of linking prehistory with living indigenous peoples, new ways of looking at connections are becoming necessary. Buckland (2004) suggests that it is useful to distinguish between heritage and the past. History is the inscribed record of the past that pro-vides event markers to be referred to; and heritage is those parts of the past that affect us in the present. The past is knowable only indirectly through histories.

Buckland draws his concepts from Fentress and Wickham (1992), who assert that historical narratives come to be (1) selected, (2) adopted, (3) rehearsed and (4) adapted. These narratives will become the accepted mythic or legendary account as opposed to other accounts for a variety of reasons we don’t know or don’t accept. For every aspect of the past, there could be many narratives, or none. As many factors influence histories, they are always multiple, appropriated, and fragmented (ibid.: 39).

Following this premise, I hold that the sociopolitical orientations people develop are based on their shared perceptual legacies guiding a series of deci-sions with new consequences which are adopted and implemented. Politics is the means by which the network of human society is organized. It requires cajoling, convincing, and campaigning to influence a population regarding their betterment, encouraging them to support and follow an existing govern-ment or in selecting a new political force.

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 8 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:25

David Blundell 9

In Taiwan, the Chinese presence has been a matter of immigration over the past 400 years developing from a minority to become a majority appro-priating eatlier cultures. This process of migration and settlement has created social formations and linkages that have expanded to include shared mutual heritage dating back to prehistory. Current politics, strategies, and govenance are blossoming to connect with an expanding Pacific minded5 regional sense of place (Blundell 2011).

Reflections from the 1980s

From 1984 to 1987, I participated in grassroots associations of citizens inter-ested in the environment of Taiwan. One such organization was Eco-Watch—initiated by Robert Jones, a graduate student in archaeology at National Taiwan University. From the early 1980s, before the Environmental Protection Administration (EPA) was established, Jones organized consciousness-raising meetings with the goal of educating and mobilizing the Taipei community to protect the environment. He employed California’s Sierra Club model. People were invited to take family hikes and picnic in the local mountains to enjoy nature on weekends. While on the trail, we were given “a naturalist’s lecture” about the local flora—and asked to casually pick up strewn bits of trash on the way. Later mid-week evenings were scheduled to share pictures of the outing with the participants and discuss the next hike.

Our group developed itineraries for the trails and we printed gray cotton T-shirts with Eco-Watch stenciled in green. With our sense of solidarity growing, our purpose quickly focused on mountainside cleanup. Families organized by the tens, from children to elders, carrying large black trash

5 Ninian Smart offering the ‘Pacific mind’ concept in the 1970s from the University of California at Santa Barbara, stated “Perhaps the Pacific Ocean is a symbol of a worldview that may take an increasing grip upon the human imagination; ... there is the rim of Asia, and there are, in the American West, new forms of science and experiments in living that have left their imprints beyond the narrower worlds of Silicon Valley and San Francisco. In the new Pacific these forces can work together: Buddhism, Christianity, science, the search for lost identities, the pursuit of happiness, the wonders of technology” (Smart 1991).

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 9 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:25

10

bags issued at the trailheads, and climbing up steep paths, bagging the litter of plastic materials and other rubbish left by earlier hikers near the trails. Mountain trail cleanups were held for several years and our numbers grew.

The popular environmental consciousness we sought became reality. My participation was a thread in a social fabric woven around the mountains sur-rounding Taipei. Then in 1985 the people of the town of Lukang responded with protests against the Taiwan government for awarding the transnational chemical company Dupont permission to build a titanium dioxide processing facility close to the old town and historic port in western-central Taiwan, near the Chang-pin Industrial Park. The local outcry focused on concern for chil-dren’s safety and galvanized the general populace. The movement—not led by political rights activists, but by local rural families seeking a clean and safe environment—arrived on the field to slay the beast, even if it was a powerful employer (see Reardon-Anderson 1993; Tang and Tang 2010).

Residents of Lukang protesting against the Taiwan government for awarding Dupont permission to build a titanium dioxide facility near the old town. (Source: China Times)

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 10 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:26

11

Taiwan Heritage Coming of Age

If the place is not recognized —It is from where the whole land is seen. The Gesar Saga6

The idea of world heritage is linked to ‘classical’ and antiquarian interests from the European Enlightenment and the Age of Reason. According to Dario Gamboni, however, our current attitude about world heritage is more recent, stemming from the 20th century. Gamboni cites André Malraux who wrote in 1957, “for a long time the worlds of art were as mutually exclusive as were humanity’s different religions,” drawing our attention to civilizations having their own ‘sacred sites’ listed for humanity (Gamboni 2001, see Blundell 2003: 2–3).

Objects from ancient Greece and Rome and religious artifacts of the ‘Holy Land’ became sought after as treasures, trophies to enhance the capitals and grand estates of Europe. With the advent of classical archaeology from the 18th century, and ethnology appearing a century later during the colonial period, unique objects and sites became intriguing to antiquarian collectors and scholars. Scholarship began when the context of origin (provenance) became important. Museums were established as institutes to conserve, protect, and study the historiography of materials. The concept of museums originated from the Greek muse, to entertain and learn from. Museums worldwide began as antiquarian and eclectic collections by individuals, families, and dynasties. From the 19th century, museums have become public institutions following the initiative of libraries, where texts and paper documents were collected. Yet, Gamboni admits that our contemporary idea of heritage is built upon notions of historic monuments and cultural properties transcending boundaries and ownership with symbolic messages and a collective interest in their conserva-tion for humanity:

The concepts of monuments and heritage originated in cultic objects and practices crucial to the identity and continuity of collective

6 Helena Norberg-Hodge (1992: 9).

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 11 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:26

12 Taiwan Coming of Age

entities such as family, dynasty, city, state, and, most important, nation. The idea of a historic monument implied an awareness of a break with the past and the need for a rational reappropriation (or a retrospective construction) of tradition. Its artistic dimension further required the autonomy of aesthetic values that had appeared in the Renaissance. The crisis of the French Revolution—which made a historical and artistic interpretation of the material legacy of the ancien régime indispensable to its survival—accelerated this evolution. The term vandalism, with its reference to the devastation of the Roman Empire by “barbarians,” condemned attacks against this legacy by excluding their perpetrators from the civilized community (ibid.).

As the past becomes a more precious resource (Appadurai 1981), society at large has come to value its meaning and to recognize the need to protect it. Documented sites of prehistory and history are becoming important to today’s population in search of meaningful identity, and in terms of archaeo-logical and ethnological literacy.

Because Taiwan has not participated in the United Nations since 1971, it is difficult to have sites in Taiwan listed by the World Heritage Committee in the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). In 2000, when referring to Taiwan, UNESCO adopted the name Taiwan (China)—a formulation not acceptable to the island’s people. UNESCO has classified world heritage in (1) cultural sites, and (2) natural sites, basing their selection on their unique value and appreciated worth to humanity.

Now agencies in Taiwan are listing cultural, ecological, and historical sites as a source of local pride to include on the UNESCO list of World Heri- tage sites. According to local thought, this should be a process connecting them with international organizations corresponding to World Heritage membership. The UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage sites was established in 1972, with the under-standing that war, natural disaster, environmental degradation, and industri-alization threaten our world’s heritage.7

7 In April 2012, sites numbering 936 have been listed worldwide. Representatives from 21 states compose the World Heritage Committee and they scrutinize candidates,

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 12 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:26

David Blundell 13

The ROC cabinet-level Council for Cultural Affairs (CCA)8 has pro-ceeded to establish heritage site possibilities for consideration. In 2001 the council launched World Heritage Days to stimulate public support, as has been the case in France since 1984. In 2002 the council initiated the Cultural Environment Year to celebrate world heritage. A local committee of histo-rians, cultural experts, architects, and local governments recommended 12 sites for observation. The CCA has produced a Cultural Forum Series (2002) of lectures given by people in Taiwan who are considered authorities on heritage sites. Then in October 2002 Yukio Nishimura, vice president of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS)9 arrived in Taiwan to assist with the selection of key sites according to international guidelines.

The ICOMOS Venice Charter described monuments accordingly:

Article 1. The concept of a historic monument embraces not only the single architectural work but also the urban or rural setting in which is found the evidence of a particular civilization, a significant development or a historic event. This applies not only to great works of art but also to more modest works of the past which have acquired cultural significance with the passing of time.

In the second article, there is mention of conservation:

Article 2. The conservation and restoration of monuments must have recourse to all the sciences and techniques which can contribute to the study and safeguarding of the architectural heritage.

In March 2003 the CCA appointed an operations committee to manage and oversee the maintenance and preservation of potential world heritage sites in Taiwan. Tchen [also spelt Chen] Yu-chiou (陳郁秀), CCA chairperson,

from well-established sites to obscure ones, based on criteria stated in the UNESCO Operational Guidelines. Website, http://whc.unesco.org

8 The Council for Cultural Affairs was founded on 11th November 1981 by the Executive Yuan to plan and administrate the nation’s culture in terms of policy making. Website, http://english.cca.gov.tw/mp.asp

9 ICOMOS is a non-governmental non-political organization of professional scholars and curators who advise World Heritage UNESCO regarding cultural heritage standards. Website, http://www.icomos.org

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 13 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:26

14 Taiwan Coming of Age

stated “We should focus on what we can do, and be ready … at a moment’s notice” in case a proposed Taiwan world heritage list is directed to UNESCO (see Chang 2003). The possibility of 12 sites, feasible or not, include (1) Yangmingshan National Park, (2) Tamsui Historic Foreign Customs Houses and San Domingo (‘Red-haired Fort’), (3) The Old Mining Township of Chinkuashih in Taipei, (4) Kinmen Island, (5) Old Mountain Line Railway in Miaoli, (6) Alishan Forest and Railway, (7) Basaltic Columns of Penghu, (8) Chilan Cypress Grove, (9) Taroko National Park, (10) Peinan Archaeological Site at Nanwang Village, and (11) Orchid Island (Lan-yu)—where the local residents are not willing to have their lands appropriated again by the govern-ment or other agencies (see Hu 2012), and (12) the loftiest mountain in eastern Asia, Yushan.

The same year, the CCA set up an operations committee to oversee those potential world heritage sites. The procedure for designating a World Heritage site takes up to five years or more and involves an inspection by consulting ICOMOS and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). These consulting agencies recommend sites to the United Nations World Heritage Committee for a decision.

Jungshe Village Fujian-style sites at Wangan, Penghu, entered the 2004 World Monuments Watch10 which lists hundreds of cultural sites worldwide -designating treasured and endangered sites every two years since 1996. The project’s judges do not come under international political pressure when considering the sites, as is often the case with UNESCO. The difficult politi-cal maneuvering within UNESCO11 at Paris caused governments in Australia and Norway to establish their own affiliated commissions. Since 1996 the Norwegian National Commission for UNESCO functioned with its own agenda under the Nordic World Heritage Office. Amund Sinding-Larsen, a senior advisor for International Affairs at the Norweigian Directorate for Cultural Heritage, based in Oslo, stated that an early project was to set up a

10 World Monuments Watch—a division of the World Monument Fund (WMF) is a project of the American Express Foundation. See Taiwan selection, Jungshe Village. Website, http://www.wmf.org/project/jungshe-village

11 China blocks Taiwan from applying directly to World Heritage UNESCO in Paris (see Blundell 2003).

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 14 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:26

15

Jungshe Village, heritage architecture at Wangan, Penghu (above and below). This site has been selected by the World Monuments Watch and the Council for Cultural Affairs for its historical value. (Source: Government Information Office)

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 15 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:27

16 Taiwan Coming of Age

Tibetan community library in Lhasa, without consulting authorities in Beijing (Singing-Larsen 1996 per. comm.).12

As heritage is a legacy from the past that we incorporate in our present life and offer to the future as a referent for local identity, it is also a marker for global appreciation. For the 172 signatory member countries of the World Heritage Convention, protection is a duty of the international community and sites should be regarded as belonging to

all the peoples of the world, irrespective of the territory on which they are located … without prejudice to national sovereignty or ownership (World Heritage Convention).

Without supportive international recognition, some sites with important cultural or natural value and diversity would deteriorate, or perhaps even disappear, often because of insufficient resources and skills to maintain them. The international community shares in the responsibilities of site designa-tion by agreeing to contribute monetary and intellectual support necessary to preserve and recognize sites of unique and outstanding universal value.

Sites selected for World Heritage listings are approved on the basis of their merits as the best examples of cultural and natural heritage. Gathering data in ways that advance contemporary archaeological and historical research goals are helped by constructing digital archival databases with geographic infor-mation systems (GIS) technology. This includes (1) constructing databases for informed cultural site management and site interpretation, (2) preparing plans for sustainable site management, (3) designing tourism programs that generate revenue required for effective site management, and (4) archiving

12 Also in Oslo, the Nordic World Heritage Foundation (NWHF), a pilot project started in 1996, works as a Category Centre under the auspices of UNESCO. NWHF is a private foundation with broad membership of the Nordic States, an observer representative from the Norwegian Ministry of Environment, and a representative of the Director General of UNESCO. Activities complement the overall work of the World Heritage Convention of UNESCO by facilitating technical expertise, disseminating information, and contributing to innovative projects, all in support of the Convention and the World Heritage Committee on Global Strategy (ref. Sandra Bruku at NWHF). Website, http://www.nwhf.no

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 16 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:27

17

Renderings of Neolithic ‘Peinan Culture’ at Nanwang Village. Above: Panorama of village with the sacred Dulan Mountain in view. Right: Detail of house with storage pit. (Courtesy of Peinan Cultural Park, Taitung. Website, http://nmp.gov.tw)

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 17 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:29

18

inventories of archaeological and historical sites.13 Landscape and architec-tural design information from archaeological research is integrated with this technical orientation as required for the site registration and maintenance (see Comer 1994).

The Peinan Neolithic archaeological site at Nanwang Village, in Taitung, has a cultural park and site museum illustrating its excavated prehistory to the public.14 The remains of Neolithic cultures extend from Taitung to Hualien, revealing a wealth of multi-dimensional research data supplying evidence for understanding the vicissitudes of the society from 5000 to 2000 years ago. The importance of the site resulted in the construction of the National Museum of Prehistory, also in Taitung, and other institutions for Austronesian studies.15 These institutions are examples of producing displays communicat-

13 Hsiang (1998); Blundell and Hsiang (1999). See also Heritage (2007). 14 Peinan Cultural Site at Nanwang Village, Taitung, dates to 5,000–2,000 B. P. (Lien 1991,

1993, 2002; Sung 1995). 15 This refers to studies linked to the Austronesian family of languages that is dis-

persed across the Pacific and Indian oceans. Its major sub-divisions are the Malayo-Polynesian languages and Formosan languages. The Formosan branch is considered to be the earliest of the languages from Neolithic origins in Taiwan (Bellwood 1997, 1999, 2009; Blust 1985, 1996; Diamond 1999: 334–353, 2000; Tsai 1999; Rolett et al. 2000).

Excavation revealing Neolithic ‘Peinan Culture’ at Nanwang Village. Left: house floor and walls. Right: Beneath floor, slate coffins. (Photography courtesy of David Blundell)

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 18 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:31

David Blundell 19

ing cultural sensitivities utilizing advanced electronic multimedia for contin-ued studies into prehistory and ethnology and their linkages with the greater heritage of the Asia-Pacific region.

The importance of heritage evaluation generates better understanding of connections to the neighboring regional network. Taiwan is taking a leader-ship role in setting trends for cultural and ecological conservation and man-agement, for educational tourism, and attending to cross-cultural engagement with indigenous people in natural settings. Following heritage recognition, what is the responsibility for site management at the local level? This is an important question since once a place is deemed to be heritage for the entire world, the locality will become subject to new demands. For me, this is a sign of accomplishment and awareness of legacies traced to the distant past, now being respected by current populations (Faure 2009). It is this local apprecia-tion for artifacts and sites that is providing a basis for heritage conservation in Taiwan. A good way to approach the local cultures, museums, and events is through the Taiwan Culture Portal: http://www.culture.tw

Eco-Cultural Sense of Place

The people of Taiwan have been taking responsibility for their society in terms of sustainability and civil function aims. Since the late 1980s, Taiwanese authorities have reviewed restricted spaces, converting them into scenic areas and national parks. In 1992, I participated in developing an anthropological method of tourism, in which the participants of traveling seminars visited places in Taiwan to exchange and share contextual knowledge.16 The people on these educational tours reflected on the culture and nature they experi-enced through interaction with local people and expert guidance. Participants interactively experienced traveling as a learning process, with respect for dif-ferences, sharing, and conversing in their own languages with the assistance of translators. They acted as both hosts and guests and got to know each other while traveling in dialogue. The seminar members exchanged ideas with one another en route and at destinations. These traveling seminars are organized

16 See Blundell (2005).

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 19 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:31

20 Taiwan Coming of Age

on a participant egalitarian basis in order to (1) explore, (2) learn, (3) interact, (4) respect, (5) share feedback, and (6) enjoy the process. Members of the trav-eling seminars are encouraged to speak in their own languages and to share their thoughts on the topic of discussion. Visiting participants—and those visited—interacted among themselves and with one another in order to share for learning. The outcome was a touring ‘classroom without walls’ (Blundell 2005).

The Institute of Cultural Affairs, a non-governmental organization based in Taiwan, sponsored these initial seminar tours. Meetings were held in Taipei with a group of like-minded people who were interested in visiting selected places with academics and local inhabitants. Seminar participants expected the traveling seminar to provide learning from different physical localities considered relatively inaccessible and separate from their daily life. When participants visited such places, they often wondered why they had not visited them earlier on their own. They considered for having an “out of daily routine experience,” their effort in creating a logistical network was necessary before they would be willing to enter unfamilar places.

This was similar to the earlier Eco-Watch activities. Local experiential interest in the public communing with various ‘natural’ and ‘ethnic’ aspects of an environment as a group led to the phrase “eco-cultural traveling seminar” (ibid.). Guides who were bio-naturalists, geologists, ethnologists, anthropolo-gists—including linguists—and professional recreational specialists offered their services. Each traveling seminar focused on a topic to explore: mountain regions of southern Taiwan, where the Rukai people have almost completely abandoned their stone houses on high ridges above 2,000 meters, or eastern Amis people, at Malan Village, Taitung, where elders sang their internation-ally renowned music. It was about learning and getting a sense of each locality while traveling and experiencing overnight home stays. Group seminar goals were set based on an appreciation of cultures and eco-cultural conservation. This understanding provided a way of getting to know the inhabitants of an ecosystem in places where cultural and environmental conservation were open to be shared.

The ethos for this type of traveling seminar rests in a ‘charter’ of mutual-ization through interaction that inspires participatory commitment. Through

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 20 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:31

David Blundell 21

immersion in the local people’s way of life, participants come to have an eco-logical understanding. Interactive events in daily life encourage the attendees to share their own experiences and interests while learning from one another and the experts on the tour. This combination of activities tends to build a sense of respect for diverse lifestyles. Seminars also involve many accepted experts on local societies and cultures as well as geography, linguistics, ecology and other arenas of academic exploration. Volunteers gave their own expertise and time to bring a new understanding of the locations to the group participants.

Sustainability of the tour encounters was our mutual goal for a common future. We cannot fully grasp other realities quickly, but accepting sustain-ability of life cycles as a guideline for environmental and cultural interac- tion and as a managing principle for the continuance of relationships be- came the ethos of the program. The seminar process became the impetus for reciprocation through reunions of hosts and guests on an individual basis. This caring aspect worked for achieving cross-cultural and ecological sen-sibilities. The most important keys of success for these activities are to have aware, responsible, and interested people who will share and articulate their personal and cultural observations as traveling seminar participants, hosts, and guests, in an ethos of living and interrelated friendship. The centerpiece of eco-cultural travel is this vital dialogue, which builds lasting, cross-cul-tural friendships.

Conclusion

Our ‘conjectured past’ gives us a present-day social consciousness. Beneath the cultural, political, and economic aspects, the compilation of a society is layered up from a perceived heritage. People in Taiwan are encountering their own sense of place as a valuable life-supporting resource that will be appreciated and conserved by future generations to come. The island with its surrounding islets is a mosaic of cultures and eco-niches-research and docu-mentation of its heritages weave together a single entity. Buckland’s heritage, “which is those parts of the past that affect us in the present” makes for its own narrative—not knowing all the pieces, yet complete as it is a totality that is made from selected fragments.

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 21 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:31

22 Taiwan Coming of Age

The problem is self-defining: “Who are we?”—we salvage the past, and edit our gathered history in ways that are inconclusive. Being Taiwanese has always meant self reliance as a group and on the island's environment that has endured abusive development, old-fashioned pollution, and waste manage-ment problems, especially from nuclear facilities. Evolving from local ecologi-cal degradation concerns, the Taiwan people have articulated their desire for democratization and the increased ability to rule for their own well-being, regardless of political affiliation. The Taiwanese are appreciating their own history seriously, and are beginning to analyze it as a basis for taking the next step in their governance. This proactive electorate is moving its destiny ahead with a sense of its own island-ness.17

Acknowledgements

Appreciation is given to Frank Tedesco, Emilie Nguyen, Michael Buckland, Wang Hui-ji, Bo Tedards, Dean Karalekas, Stefani Pfeiffer, and Christian Rowe for their instructive critique.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, Christian A. 2009 The new Austronesian voyaging: Cultivating Amis folk songs for the

international stage. Austronesian Taiwan: Linguistics, History, Ethnology, Prehistory. Revised Edition. David Blundell, ed. Taipei: Shung Ye Museum, and Berkeley: Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California. Pp. 282–318.

Appadurai, Arjun. 1981 The past as a scarce resource. Man, 16(2): 201–219.Bellwood, Peter 1997 The Austronesian dispersal. Newsletter of Chinese Ethnology, 35: 1–26. 1999 5000 years of Austronesian history and culture: East coast Taiwan to Easter

Island. Festival of Austronesian Cultures, Taitung, 27th June.

17 Tariq Jazeel (2009) has conceptualized ‘island-ness’ in an article related Sri Lanka for giving a sense of place from ‘colonial repetitions’ and present-day identity.

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 22 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:31

David Blundell 23

2009 Formosan prehistory and Austronesian dispersal. Austronesian Taiwan: Linguistics, History, Ethnology, Prehistory. Revised Edition. David Blundell, ed. Taipei: Shung Ye Museum, and Berkeley: Phoebe A. Hearst Museum, University of California. Pp. 336–364.

Blundell, David 2003 Designating world heritage sites in Taiwan. New Research on Taiwan

Prehistory and Ethnology: Celebrating the Eightieth Birth Anniversary of Emeritus Professor Sung Wen-hsun. Taipei: Department of Anthropology, National Taiwan University. Section 12. Pp. 1–12.

2005 The traveling seminar: An experiment in cross-cultural tourism and education in Taiwan. National Association for Practicing Anthropology (NAPA) Bulletin, 23: 234–251.

2009 Languages connecting the world. Austronesian Taiwan: Linguistics, History, Ethnology, Prehistory. Revised Edition. David Blundell, ed. Taipei: Shung Ye Museum, and Berkeley: Phoebe A. Hearst Museum, University of California. Pp. 401–458.

2011 Taiwan Austronesian language heritage connecting Pacific island peoples: Diplomacy and values. David Blundell, ed. International Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies (IJAPS), January: 75–91. Website, http://web.usm.my/ijaps/default.asp?tag=2&vol=13

Blundell, David, and Jieh Hsiang 1999 Taiwan Austronesian electronic cultural atlas of the Pacific. Pacific

Neighborhood Consortium (PNC) Joint Meetings Proceedings. Taipei: Computing Centre, Academia Sinica. Pp. 525–540.

Blust, Robert 1985 The Austronesian homeland: A linguistic perspective. Asian Perspectives,

26: 45–67. 1996 Austronesian culture history: The window of language. Prehistoric

Settlement of the Pacific. Ward H. Goodenough, ed. Philadelphia: Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 86(5): 28–35.

Buckland, Michael K. 2004 Histories, heritages, and the past: The case of Emanuel Goldberg. The

History and Heritage of Scientific and Technical Information Systems. W. B. Rayward and M. E. Bowden, eds. Medford, NJ: Information Today. Pp. 39–45.

Chang, Yun-ping 2003 Five scenic areas nominated as possible UN world heritage sites. Taipei

Times, Friday, 31st January. P. 1.

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 23 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:31

24 Taiwan Coming of Age

Comer, Douglas. 1994 The SPAFA Unified Cultural Management Guidelines for Southeast Asia.

Volume 1: Material Culture. SEAMEO Regional Centre for Archaeology and Fine Arts, Bangkok.

Diamond, Jared 1999 Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York: W. W.

Norton & Co. 2000 Taiwan’s gift to the world. Nature, 17th February, 403: 709–710. Faure, David 2009 Recreating the indigenous identity in Taiwan: Cultural aspirations in their

social and economic environment. Austronesian Taiwan: Linguistics, History, Ethnology, Prehistory. Revised Edition. David Blundell, ed. Taipei: Shung Ye Museum, and Berkeley: Phoebe A. Hearst Museum, University of California. Pp. 101–133.

Fell, Dafydd. J. 2010 Taiwan’s democracy: Towards a liberal democracy or authoritarianism?

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 39(2): 187–201.Fentress, James, and Chris Wickham 1992 Social Memory. Oxford: Blackwell.Gamboni, Dario 2001 World heritage: Shield or target? Conservation: The Getty Conservation

Institute Newsletter, (Summer) 16(2). Website http://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications/newsletters/16_2/feature.html

Gold, Thomas B. 1994 Civil society and Taiwan’s quest for identity. Cultural Change in Postwar

Taiwan. Stevan Harrell and Chun-chieh Huang, eds. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Taipei: SMC Publishing Inc. Pp. 47–68.

Heritage 2007 Will UNESCO register Taiwan as the origin of Austronesian peoples? 5th

August.Website, http://www.nowpublic.com/will_unesco_register_ taiwan_origin_austronesian_peoples

Ho, Ming-sho 2010 Understanding the trajectory of social movements in Taiwan (1980–2010).

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 39(3): 3–22.Hsiao, Hsin-huang Michael 1990 Emerging social movements and the rise of a demanding civil society in

Taiwan. Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs, 24: 163–179.

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 24 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:31

David Blundell 25

Hsiang, Jieh 1998 Digitizing Taiwan’s historical archives—The NTU Digital Library/Museum

Project. National Science Council Monthly, 20(12): 1516–1519. (Chinese) Hsieh, Shih-chung 1994 From shanbao to yuanzhumin: Taiwan aborigines in transition. The Other

Taiwan: 1945 to the Present. Murray A. Rubinstein, ed. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe. Pp. 404–419.

Hu, Jackson 2012 Retreiving ancestral power from landscape: Cultural struggle within Yami

ecological memory on Orchid Island. Taiwan Since Martial Law: Society, Culture, Politics, Economy. David Blundell, ed. Berkeley: University of California and Taipei: National Taiwan University Press. Pp. 183–210.

Jazeel, Tariq 2009 Reading the geography of Sri Lankan island-ness: Colonial repetitions,

postcolonial possibilities. Contemporary South Asia, 17(4): 399–414.Lien, Chao-mei 1991 The Neolithic archaeology of Taiwan and the Peinan excavations. Indo-

Pacific Prehistory Association Bulletin, 11: 339–352. 1993 Peinan: A Neolithic village. Stone Age Farmers in Southern and Eastern

Asia. Illustrated History of Humankind, People of the Stone Age, Hunter-Gatherers and Early Farmers. American Museum of Natural History, Harper San Francisco: Weldon Owen Pty. Limited/Bra Bocker AB. Pp. 132–133.

2002 The significance of the jade industry in neolithic Taiwan. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, 22: 55–62.

McLuhan, Marshall 1964 Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw Hill.Morrow, Lance 1989 Welcome to the global village. Time Magazine, 29th May. P. 41. Norberg-Hodge, Helena 1992 Ancient Futures: Learning from Ladakh. San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club

Books.North, Robert C. 1976 The World that Could Be. Stanford, CA: The Portable Stanford.Reardon-Anderson, James 1993 Pollution, Politics, and Foreign Investment in Taiwan: The Lukang Rebellion.

Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 25 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:31

26 Taiwan Coming of Age

Richards, Martin 2008 New research forces u-turn in population migration theory. University of

Leeds, 23rd May. Website, http://www.leeds.ac.uk/news/article/350/newRolett, Barry V., Wei-chun Chen, and John M. Sinton 2000 Taiwan, Neolithic seafaring and Austronesian origins. Antiquity, 74: 54–61.Smart, Ninian 1991 The Pacific Mind. Article 19787, Section: Modern Thought. Website, http://

www.worldandi.com/specialreport%20/1991/March/Sa19787.htmSung, Wen-hsun 1995 Peinan excavation. Proceedings of the International Conference on

Anthropology and the Museum. Tsong-yuan Lin, ed. Taipei: Taiwan Museum. Pp. 365–368.

Tang, Shui-yan, and Ching-ping Tang 1997 Democratization and environmental politics in Taiwan. Asian Survey, 37(3):

281–294.Tsai, Pai-chuan 1999 Towards a greater Austronesian cultural sphere. Paper presented for the

European Society of Oceanists. 26th June, Leiden, Netherlands.World Monuments Watch 2010 Jungshe Village, Wangan, Taiwan. World Monuments Fund (WMF) project

of the American Express Foundation. Website, http://www.wmf.org/project/jungshe-village

taiwan book 5.14 內文CH1-10.indd 26 2012/6/5 上午 11:47:31