SURVEY OF LAND-GRANT COLLEGES - ERIC

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of SURVEY OF LAND-GRANT COLLEGES - ERIC

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIORRAY LYMAN WILI3dR, Secretary

so,

OFFICE OF EDUCATIONwmulw pail COOPER, Commissioner

o

,,....

1111111r

s

z BULLETIN, 1930, No. 94.

t.. SURVEYOF LAND-GRANT COLLEGES

8

AND UNIVERSITIES.

V. Directed by I

ARTHUR J: KLEIN, ChiefDIVISION OF COLLEGIATE AND PROFESSi6NA4. EDUCATION.

OFFICE 45F EDUCATION \*

4

fr

IN TWO VOLUMES

.Vphime Ilb'

54.

a

UNITED STATES

4

GOVERNMENTPRINTING OFFICE

WASHINGTON 1930

We by the Softristaldent of Decubssats, Vhohlistei, D. C.r`t.

la it

:11

st

, a

eo

elb

aggalmtge

al

IIP

.

5

Peke CS

V

.4 .1

"- e4;Y

.

flo

44

.. --.. 6 Mt' t - ;

3

ma. ; 0%4.4

-.

-%

4

%

%As

18.,

et

\

.11z. Ar

h

i

1

i.1,

II

'41

g41

1

1. .

111

- -au e. -a

.

. .

:

er.

441?. .0 .. . .., ::.. ' . , :.

'.:-. -

.. . -4 :

.I

., -a.... -... if .. , ... .%

.11 e '.* .' 41 " 2. *. i- ZA....:415lib 4:6*..-otAfriii

#.. 4 ; ... '4, . ' .. f .1 ,..%. V ... .. " ''

0 l' . 8 ."-1 ". -. 4.- I* t. .t ..,. ...;..:. f1- - i 4*', f . .., . ---¡ ,,,i4, .7.

i -,,. - ., E --a...-- '"- "i:-Z4-A: ''.,. -6- ,-kis-- ., 1-._,--.........--r& ,...L.AL -,..-__........_ __ ..7,...".&4.:..,'..-.1&-,....IL-. ...._3434 ,.. _ . A ,. _,.. ,-.. -- -. - -8;". 2 '24- : AZ ,4.:1'..,7-1).. rit,?,re _ , ,..i.:e i -tr.-- . . _

:

1

:

4qt.

Ir I . 1

:. %4 ,1

1 $

1 01/ O. ;it if* .1

. 71- II

*

4,% . Ili,'. . r

7. * .

4

1% 7

:

'

f.

., ... 1. --.I,;

.7 .S

4. ,.

. : 51

.%

t

0

e.

.

.

6.

a

.

go,

T 1

a.

(1639i0DEC 23 IU8

4t.r

/ '1 0+EW./

Letter of trEknsmittalPreface

CONTENTS

Part I. Historical introduction

Pagev

Part II. Control and administrative organization :Chapter I. State relationshipsChapter II. Governing bodiesChapter III. Chief executive officerChapter IV. Educational organization

Part III. Business maitagement and finance:Chapter I. Organization of business and fiscal officeChapter II. Income and receiptChapter III. Distribution of expendituresChapter IV. Business management, financial methods. and amount-ing systemsChapter V. Auxlliury enterprises and serv.ice departmentsChapter VI. Land and buildings. operation, maintenancè, and newadditions fit physical plantsChapter VII. Suultaary and conclusions

Part IV. Work of the registrarl'srt V. Alumni and former studentsPart VI. Student relatioiis and welfare:

Chapter I. Introdaetion_____ChapterChapterChapterChapterChapterChapterChapter

GM ........ amo ...... *II. Welfare äbd advisory staffIII. Personnel serviceIV. Housing and feeding studentsV. Health serviceVI. Physical welfare, including athleticsVII. Orientation of freshmenVIII. Religious organizations and convocations or as-.......

Chapter IX. Scholarships and fellowships__?!Chapter X. Student self-help and student loansChapter XI. Student social organizationsChapter XII. Social .....Chapter XIII. Student welfare organizationsPart VII. Stair

Part VIII. tip library:Chitpteri. IntroductionChapter II. Usability of libraryChapter III. Methods of facilitating .........Ohapttir Iv. Books and periodiCals

am.

Oe

Me*

Chapter V.Chapttr VI. Administrative controlChapter VII. PersonneL_____Chapter VIII. Financial

asupport and library budgets... :-Chapter I'M General

...am midi, of ow o -

. ....MM 01. .. all MD NM SD aft e

... d' dm .....

4034ori

420425'

444467

478485503517550554569

609618823649661671679

712

,

ti

1930t.

1601wew

;......

... .. ms 444 AM 44............ 4.1 '414.

4=0 MED MI 4MO DNS ONI 4 a IM4 11 41. wow GSM ap 4ND am.

-y 4441,

' wi wl

.... ...44. 4m - man 001. OW OM MIN OM

. .... ..

41. 111

WIND

wor Wow a....ww C..... own....... ems. . ..... ..... ....

conelusIpus ...

4IM 42ND 4WD i 4WD alp

"b C 41.m. OM Om inj4D

.4. ...MO

aso.. am. we um wo .w Ex. w. 4111. C w.

4.. 410 410 MINIM OD MY al 10 alb 410111111b am , ,,,0641. room

VII1

52

us

75861'

123

158198

237258263345

435

699

...

4ip

1P

. Ala

.f-4' '

:.' . *- t, '1.. -,,, oz.,.: '', -7.... ....-._. ; . ?,.. , :t...r, .....x... . - 0 - 0.:k -:;--:., w

4 .T.*. *****--t' .--rr - -i i '... ' - , - e ,-,' .*x vs .- .- . ...:, .....ftic.:94.%.*...:.t-e:

1*qt-.ett5.

C

35

634.

NM am

.....MM 41 WM& =1D .0 MI% M MIM

MwelIN_____ ..... MI

caleiular.

ee dip

IV 9ONTENTSA

Part IX. Agriculture:.Cliapter I. Introduction__,......:....... .. .......... 715Chapter II. Organization

721Chapter III. Lands owned and controlled by land-grant colltges..... 731Chapter IV.. The staff in undergraduate instruciion in agriculture.. 734Chapter V. C'ourses and Arricula 754Chapter VI. Agricultural ........ ,..... _ 770Chapter VII. Judging783Chapter VIII. Conc:usions and recommendations 786Part X. Engineering:

Chapter I. Introduction____________________________............... 789_

Chapter II. Position of engineering in land-grant institutions 796'Chapter III. Student problems ..,_ 802Chapter IV. Curricula_________...... 805chapter V Staff_ ..________..._-____ ............ --.. ___...______ ___1

817Chap ler VI. Suppoit and orga ns.. .or am am am. m Op IIM .0 am amo .....Ig

824. -Chapter VII: ervices of land-grant engineering colleges 834Chapter VIII. Conclusions and recommendations 844Lyart XI. Home economics:Chapter I. ..... ....... 847Chapter II.

855III Staff-,868Chapter IV Physical facilities890-Chapter V. FinancIng___..._901Chapter VI. Courses_910Chapter VII. Curricula923Chapter VIII. Home economics teaching ..... .965

. jWiayter IX-. Students968ChapWr X._ Conclusions and recommendatious____________L_ 980' Index 41 ...... NIP MN. CID MP MD =1 C 991

401

,

**

-

s.

.ie4.

411

6

4

a

-1

00

a

-

E.

Wm.= elmme =Wm, IMP MO

studentscontests____

.... .

_

st-t

........M mot

6

ase

..... .. . .ft,

___Chapterom ge es 1=1 so 4.1 41.. OM& ORD

MI vas mow em. M. A... me mmom,..

.. MO MOOR Offe =DIM Om .m.

s ../. imor alms Imo OW MID 'MP 0111 II ........VP

__1N gd

!M.O. ddd..M0 fliM me. ........ 11 CM

6

J...

L..

.:0

-

."1.. 6i

,.16 I'''.4- . -- .I '.

,., . I .

.1*. " V.

1..--,.4.1. ICI.. , 4* t. ..: . -.: .. .* - .. \.. ' 1 ..- r %

Firrt .1. ,71 'a . 6 . % r..) ) . I "...; .w ' ....ta . " "'.. 7 --,', %O. . . e- -t ..,..... .".. ..... .,, . ... te ? * *_ ,.......-'r #!..k' s S 4:c 1_7:_.......-1....,,,,, ....,.......: !-44.4d--c- ,JAL.-4., -*1-2. . - ,..ht .4" -1._;:ljg.' ..;-,----_ -. -.--r- _s 't;4 ..- ;*". %.-dt.A.a.. ; ,. ;

-._ ..., 4 --....Y5-. - .. -1, -,,'-r. .-191..... ---"- .c...1.--s---- "-- ---,QC,- b "

1.4

.1

..

fri-,

aim

-481.

LETTER OF TRANSMIT l'Ad

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR,OFFICE OF EDUCATION,

Washington, D. C., August 22, 1930.SIR : At the request of the Association of Land-Grant Colleges and

Universities, the Office of Education imdertook July 1, 1927, asurvey of the 69 land-grant colleges and universities, including 17institutions for negroes. The survey waA completed Sune 30, 1930.The expense of the survey was defrayed by Congress which appro-priated $117,000 for the purpose.

For more than a half century these institutions have grown inimportance as vital factors in the agricultAiral, industrial, and edu-catioRal progress of the Nation. However,. in view of the greatchanges th*Ilave come in the economic and social life of our coun-try it becanie'' highly desirable to make a critical study of iheachievements of these' schools and to realwraise on 'a scientific basistheir objectives and functions.

The survey vi ksic data and information which scan beused by e mstitutio* ttd by the States in making adjustmentsthat ay nec&sary to devAop a more effective educational program,and render increasing service to the social and economic life ofthe Nation.

In order to promote the welfare of these schools and to assistthe public in more fully understanding their contributions to society,I recomfnenct the publication of thit iurvey reliort as a bulletin ofthe Offièe of Education.

Respectfully submitted, .

The SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR.

10.4.

WILLIAM JOHN COOPER,

Comminioner.

, mot

of°

A.

o

"

rt-

1

r.

N

".it

-

e

t.

I.

715

ifA

'41

-1-

. .A

:"'"..

:

'. ...

'-,

.

-'. ...: .,?- - . , 1.1. A ' I.( I- L. ; .:1..._ ....-Z4. - - -. I..,r... -;7 Cik?..r.k(4,,,:

.0 ..;

..i r - . _- .14 .ilt -,...rr.,,,,....ft.. 4,5.,,`:%.PTVe ' : A

$ lrf'4.4. t. .1.J" ::' -C;¡:- .5,-,-. t. ...._ .'Iakier,. .......o is

HIRAI' VI I.-STAFF .s

The earnings, training, experience, age, family responsibilities,tvpe of work, rank, and scholarly affiliations of members. of the staffsof colleges and universities are intimately related. The survey oflimil-4grant institutions pr(Isented an opportunity to secure informa-tion in sufficient, (plant ity -to justify analysis of.some of these rela-tionships i n greatei detail t han sta lies have usually undertajcen.There ae now 20,988 nlen and 5,3121 wonwn members of administra-tk e and instructional !;taffs in the Jana-grant colleges and universi-ties. More Allan 12,000 members of the staffs of these institutionscooperated by furnishing in usable form information requested by anextensive gilest iolinaire.

Since limitations of ttme mill space linve made it Impossible to analyze andpresent in this report all the Information thug collected, the following list ofitems co.ered by this questionnaire nut y be of tisIst mice to studentx who desireto pursue the subject further by persoilal Investigation of the data on tile inthe United States Office ()T Education. The (I uestioinmire secured informationfor'each staff member concerning age, academic rank, title of position ; college,school, or major division Of service; department, sex, race, marital condition,birthplace, salary, perquisites, additional institutional earnings, noninstitu-*mat employment ; collt%ge, nornUtl aiul university training upon boththe undettrndunte and graduate levels; major and minor subjects studied,work in professional education ; earned and honorary degrees, degree equiva-lents ; elementary and secondary school experience in teaching, supervisory andadministrative work, and in various subject-matter fields ; business and pro-tibsqonal experience; college, normal school, and university experience withtenure, subkLt-matter field, level and nature of work in each such inNtitution ;age of attaiMig and length of 'service in each academic rank; teaching load ;percentage of time employed by institution; distribution of time among differentinst it utiona i duties ; nature and number ot_ publications ; sabbotic, and otherleaves ; membership in and attendance upon meetings of professional, scholastic,and 'scientific organizatkms; special honors attained.'

The statistical records of selected portions of the informationsecured by this questionnaire constitute the greater part of the reportthat follows. Comment has been restricted to the more obviously'interesting significant feptures of these monk.; in order that alarger portion of the data themselves might be presented. It isbelieved that the statistical tables that follow will provide data forinterpretation and study that have not usually been available tostudents and institutional administratom

ForAkeussion of- the mat fr6m the stnndpoint of the maj divisions pole rfirtos IX,X. and NI. and l'ol. II, Ill and V.

43,569

et

I

l'arti%

44.

"Alp

,

'.1

570 LAND-GRANT COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES

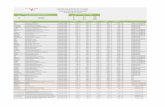

Almost every staff problem is in some way minted to the compen-sation paid staff members. The salaries Nid members of the land-grant college stalks, therefore, present a convenient point of depar-.4ture for presentation of the facts available with reference io rank,annual period of service, age, training, and otlwr factors that aresignificant in evaluating the nature of the administrative and teach-ing forces in this group of institutions.

It is usually assumed that salary varies .with rank and with thelength of the period of annual service. Table 1, presents the factsN.vith reference to these relationships for 51 of the land-grant institu-tions. Ti4 information is derived from the annual reports madeby the land-grant institutions to the United Stites Office of Educa-tion.

TABLE 1.Salaries for 1928-29 in 51 land-grant collegeR'

Salaries paid for academic yearending June 30

Up to $1,499$1,500-$1,749$1, 75041,99922,004-$2 249$a,250-$2,499$Z 500-$2,749$2,750-$2,999. _

$3,000-13,249_$3,250- $3,499$3,501)-$3,749$3,750-$3,999$4,000-$4,249 .

$4,250-$4,499. _ ........... _

$4,500-$4749. _

i,750-$4,999MOD-35,249.250-$5,499

$5,500-$5,749$6,150-$5,999$6,000-$6,249$6,250-$8,499$6,500-$6,749_$6.75046,999$7,000-$7,249$7,250-$7,499

E,500-$7,749,750-$7,999,004-$8,249

650048,749 4

000 and over

Total nuiiiber Qf cases- -

e Number of full-tinie staff

Deans Professors

9 12 9mos. mos. mos.

2

1

1

421

1

5545

. 24461

1

1

13

AIND alb

2

2

97

Median 5, 193

3

12MOS.

4 5

18 111

4 42 44 52

144 781 82

10 2359 131

34 3227 146

20 20317 6137 207

4*

13 834 10

30 981 2

18 321

12 3635 16

1

5 12

8

10 9

283 1, 847

4 071 4, 278

Associateprofcmors

9mos.

4

1

43

919

23 8316 8082 19369 149

NO 176158 &3

...245 4154 18

151 IN51 3

149 64 2

44 4

1

1

31 1

31

20 1

10

4

1, 397

4, 161

888

3, 342

Assistantprofessors

1

42578

1066 141

588842641713

12

4

1111,

664

449

1262094211 ti 1

33o96it419

91436

2

3

1

Instructors

12mos.

34

3014)

91192

174

71102387

31

1

9mos.

10

12mos.

11

118 73301 77645 122805 212279 117195 7343 3727 45

9 47 82 21 1

1

MO al M. MI,

40

1, 633

3, 207 2, 738 2, 880-

2,4331 772

Massachusetts Insiligte of Technelogy is omitted.

2, 006i

Z 134

_ ....

-

.... _

.

.; .4.

-

1

_

23

7 I'

1 I

1

L. I.

.

_

54j

.. _

i

5

. ;

1

.1

41

MOS. I Mos. I

1

27

1

85

1

1 ,1 -

a

.4

r

861

. .

_

_

_ . _ _

*

.

.

1

1

OP MI.

STAFF' 571

One striking fact brought out by this table is the curious condi-tion that exists with reference to the salaries of deals, professors,and associate professors, who serve upon the basis (if 12 monthsannually. The median salary for these staff memberm is less than themedian for stair members of similar academic rank who serve uponthe nine months' basis.

In order to detiennine whether the levels of salaries for the differ-'ent. ranks vary as between fthe different geographical regions and todiscover the relationship of salaries upon the 9 and 1 '1 mititths' buisesin the same ateas, Tables 2 to-^6 were prepared from the basic data40111 which Table 1 was derived. ,.

TABLE 2. SuIarie8 for North Atlantic Division'

Salaries paid for academic yearended June 30

1111111

Up to $1,49(,)_. .

$1,500--$1,749

$27W-$2,249....$2,2.10 $2,499$2,.r4(1- $.2,749.$2170 $2,999$3.004- $3,249$3,20 $3,499$3,!00-$3,749$3,7W-$3,994,)$4,00044,249$4,2N)-$4,490$4,500-$4,749$1,79--$4,999$.0(0- $5,219$.1,250-$5,499

$:,,750-$.5,999$6,000-$6,249...$6,250-$61499...$0,500-$4i,749$6,750-$6,999$7,000-$7,249$7,250-$7,499

_ _

.$7,750-$7,999$8,000- 04,249$8,2W-$44,499$8,509-$8,749

$9,000 and over

Ntrinber of full-titne staff

Deans

mos.12

mos.

3

1

1

... .- - . -

2

22

1 43 6

A I

3

r.,

Total number of cases..

Median

1

2

1

2

3

16

2

41

4, 781

Professors

mos.

4

Ale

22

106964

27411258

1

91

15

3

15

3

5

12mos.

227

822

21331357

1

11

15

4

15

4

4 4.

420 399

4, 195 4, 193

Associatoproktssors

2182222

712361

-

12mos.

7

AssistantIprofewirs

mos..111

8

1

27

11141043

A* IM

4

235407939

1013426

7732

5

-a

94

3,057

12MOS.

11

21

3109

3511

-r-1311

1

. 2

Instructors

1

9 12mos. I mos.

le

52 383 121

3, 339 2, 978 2, 761

4M

1, 991

11

3.5112,52623196

201

1

167,

2, 120

North Mantic Division: Maine, New Hampshire; Virmont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecti-cut, Now York, New Jersey, and PennsylVania,

it

1

........ .. _

$141716 -$1,999

2 I

..... . _

$!,500- $5,749

$7,50&-$7,749

$14,750-$8,999

9

2

1

I. 8

7, 500

9 .

5151

73 73

SI

mos.

_

9

. .1"

44')

6] 27533033

oar dB...

1

ge

I

. ..........

....._

_

....... _ .....

5

.1

11

.1/

1

1

1

572 LAND-GB1T COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES

TABLE 3.--Salurien for North Central Division' a

Salaries paid for academic yearended June 30

1

Up to $1,499$1,500-$1,74ar_$1 .750-$1,99r _

$2,000-$2,249 .

$2.2.10--$2.499P1,500-$2,749$2,750-$2,99u$3,000-&1,219...It3.2.50-$3,49tt4.500-$3,749$3,750-$3,1.0911$4.(X)0-$4,249$4,250-$4,499 .

$4.500-$4,749$4.750-$4,109$5.000-$5,349_$5,2.50-$.s,499

$5,750- $5,994.$6,001,-$6,249$6,12.410-$4, 199 . .$8,500-$6,749.$6,750-$6.999.$7,000-$7,249$7,250-$7.499.$7,500-$7,749$7,750-$7,999.$8,000-$8,249$8,250-*499

18,500-$01,749.$8,750-$8,tM).$9,000 and over .

goy,.

Deans

12

Moss mos.

Number of full-time stall'

professors ASsoeinteI irofessors

9 12

film% I rnos.

3 4 3 6

1

. _ _

1

1

1

. s. . . . .

Total number of cases..

Median

3

1

3.

... ..

11.

1

. _

1

I I

13 . Jts

Assistant

12 11

mos.

7 I s

, t 11 : 91

27 II 7,..; i so1 i 10 1,2 :10.A, ;s

#1 17 ....'11.1 515 91 10o :;11 1i , '20 175 102 141 171 :vi ..:1 39 11:i i',, 51

).... .) .tt :0 ; w ..)..9

s 4CO i 3f; I

1

. _ . _.)

1 .. )7; I13 _.. 21 1

_ 1

G S 1 1

1 . _

3 1% iti 1

1

5 2

2 1

341

3241

I;

10

49

1 ,

1

1

4

1

1234

Instructors

1 9 12HU*. I mos.

10 II

1 322 114

:NU1 4013

12#;

71 i 111

10614 _

12I.dim

)3

32

54

$7

43

37

'31

17 ?1

2 2ti 7

1

1

A. ' .i

:40 1 94 687 44ft3 i 401 268 M2 40141, 130 328_________.tow 6,1144 4. 744 4. 577 :4, 512 3, 1130 2, 858 3, OM 2, 081 i Z 187

North Central Division: Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, lowa, Missouri,North Dakota, South Dakota. Nebraska, and Kansas.

-

VT.

.

.

.

.

$5,501)-$5,749..

.

9 1!

1130S.

i2

., -

1

4

.

.

1 '

3

.

I

,

I.

.

!

:

.1

5

1

.-.

.. _ .....

. . _ ...

I

i.: .

. . . .

nids.

. .11

1

:i

g 1 i .. i I

k

.MOS.

.

- i

______i I

1 ;I , .

1

1

. . 7

4M. .

. ;

A

I

;L_. 12

1 12

w14..

06

I

.

.

-

-

lit

H4M1-

....... a 01.

_

7:p

.

1

¶.1373f;

Is

3

.2.2

41;

1 1

_ 1

.

1

......)

._ .

_ .4 - ..

..... - ..... - ....

44.

STAFF

4.---4alariex for South 4 Mud Jr Division'

Salaries paid for academic yearended June 30

Number nf ft111-tIme stitft

Deans Profest tN

I 12 12

mos. I mtgs. mos. mos.

3 .1

1-

p 10 $1,499 s4

$1.:41u--$1,74(4$1.10-$1,V99 : ;

1 .

$200-$2.249 . I

$2.2.'10-$2,494) . .,. 2 . .

V N10-$2,749 ,1 tl

$2,7:10-$2,109 1 r.13,000-$3,249 . _.. .... 1 1 , 22$3,250-ti.499 1 .1

! :4

&i.:410-$3.749. .) 49 ! 133.7.10-$3,099 .) i'l I 6

$4.01.0-$4,249 1 ... . ao ! n$4,2:1044,499 . . ..... I . )..P)

1

$400-4,749 ...i. . .' .1 17 15A4,750-$4,1419 i 4 2 ' 1

..(10)-$.1.240 3 ,

2 )1

9'1,0M-41,249 24.42.itt *4,499144.IM f41;,74. 1

14.7.-10-,41.9349$7,(100-$7,249

$,100 :ìwl ON45r

2

Assoei:ite Asmi.ittantprofes%40ts IIrofeiNors

1.1

rno,t. mos.12

6

4

20*.t%t

221:4

1

1

Total number of climbs 1.5 36 221 101 105

Median 141 4, s1:1 '4, o2 3, 750 3,14s

12

31

2721

573

- S M.

Instructors

1? q 12Tints mos. mos nine.

11I

3. *1

1

95 10 109s 2.5

411 11 712 52 8 1

3 I_1

. .

.1 ¡v.....1 _

a,

11

19 s

79

196

1

. . -

1

2, 506 2, :AX) 2, On 1, S89

IND

Ico 112 NI 266 62

Z h19

h Divkion: Maryland, Virgil, West Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Dela-ware, (;I.orgla, Florida, anti Porto Rico.

f.

4

TAinit

I

.... .

.

.

$.1,2:10-tr).499t?11u-ts.749f.I.7:104.s. 099

$7.2?0-$7,4..r.).........

.r. 1011100..

(.1

4

.

..... . . . . )

.

1

e

. . .

.)

. .

. . .

om.

9;

. . 1

1

. 2Ai

.5

.1

,

1 ;

I 1

1 I

lim

.1'

LL

t.

.

;

.........

- - .

"I,

7

i

I

.26

- 9 t

.t

000

.

._

&MI

0.MO.. OM

ID

*t it.

574 LAND-GRANT COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES

T %nix 5. Salaries for South Central Division'

Salaries paid for academic yearended June 30

1

Up to $1,499. ......$1,500-$1,749..$1,750-$1,999 .....$2 000-$2,249$2,250-$2.499 .

$2,500-$2,749.. ......... _$2.750-$2,999.$3,000-$3,249$3,250-$3,499.$3,500-$3,749$3,750-$3.999 _

$4,000-$4,249$4,250-$4,499$4,500-$4,749$4,750-$4,999 .

$5,000-26,249$5,250-$5,499$5,500-$5,749 ..... . _ ..... . .

$5,750-$5,999$6,000-$6,249$6,250-$6,499$6,500-$6,749$6,750-$6,999$7,000 and over.

Number of full-time staff

Deans

9mos.

2

2

Total number of cases. _ 27

Median ....... _

12MOS.

2 243 2

81

1

1 1

101 1

1

1

35

4, 958 5, 141

Professors

9mos.

4

32

152552264414

5

2

Associateprofmors

12 9mos. mos.

1

31

4 1028 3311 1231 IS54 1

31

5

190

3, 731

1

1

173

8013, 3, 170

12mos.

7

6195125

8

Assistant InstructorsProfessors

9mos.

8

1

34

1237321913

31

1

12 9mos. mos

a

17

11

2742158

:1

115

2, 909

135 121

2, 582 ! 2, 533

le

1233

2410321

12MOS.

11

2

21

2548

14

2

21

-

0,

2311:. 113

1, 965 %1 2,046

South Central Division: Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas,and Oklahoma.

.

.....

1

It 1

1 8

9

i

a

83

5

J

9

1

.

...... . ..... .

I

;

.

dt.*

AtIl

-

414

. _ _ _

-

....

I

66

.

STAFF

TABLE 6.----Salartes for Weitern Division

575

Salaries paid for academic yearelided June 30

1

Up to $1,499._$1.500-$1, 74SL.$1,750-$1, 999$2,000-$2.249$2,250

749$2,750-$2,999$3.000-$3,249$3,250-$3,49910,500-$3,749$3,750-$3,999$4,000-$4,249.$4.25044,499$4,500-$4,749 ................$4,750-$4,999$5,000-$5,249.$5,250-$5, 499$45,500-$5,749$5,750-$5,999$6,00&-$6,249$6,250-$6,499'4500-$6,749$4,750-$6,999$7,00G-$7,249____$7,250-$7,499$7.500-$7,749$7,750-$7,999th,000-$8,24to$8,250-1rS,499$s.509-$8,749144,750-V4,99g$9,000 and over_

Total number of cases.____.0

Median

Number of full-time staff

Deans

9M08.

3

171

1 3

2

1

1

131

8

131

1

4

2

Professors

9mos.

4

12MOS.

9

4,375

1 1

6 ; 42

203

13.2343

22 1854 1810 638 38

8 1631 22

1

20 13

21 3

7 5

.13 1

7 2

5 1

Associateprofessors

_

52614254658273

1

- .

12MOS.

7

1

5211224

4156

1811323

Assistantprofessors

8

54344

. 11818971781

Instructors

1233

1 998 100

25 M33 342029 425 3

4 1

294

a. a.

2

1

a a a a ..a. a a a aaino a

4E, aaaa

77

4,375

329 231 205

4, 248 4, 146 3,427

126

469

34291522

aa

. - -

IMP

351 II 346 102

3, 240 2677 Z925 2,073 2.235

I Western Division: Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Arkona,Utah, Nevada, Idaho, Wash-ington, Oregon, and California. Also Alaska and Hawaii.

For convenience in making comparisons, Table 7, showing mediansalaries by geographical divisions, ranks, and annual periods ofservice, was prepared from the detailed information presented byTables 1 to 6.

q.

I I

$2,499S2,500-$Z

1 P'

1

3

1

23

9mos.

2237

A

4

9mos.

I

1

12InOs.

9mos.

12mos.

.. ...MD ...

- 4. .imb -

Gm a. ono

mb a..

1:714

ft

AV,

dt-40"61°8*-.two

1.

tN,

-

IP

6

,

a. 00

9

a. a.

ao =to la

ala.

M, 4110

mt. a. .11.

2

576 LAND-GRANT COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES

TABLE 7.Iledkrn salaries 1928-49

Division

North A tNorth CentralSouth AtlanticSouth ('entralWestern

Median for enttre nited St ates 5. 193 I 5, 071 4. 278 4. 161 3. 342 3. 207

Q 1 4, 703 i 4, 131 3, 765 1 3, 705 3, 034Q ) 6, 438 6, 144 5, 074 I 5, 010 I 3, 682 ¡ 3,b12

Salaries of staff members

.A ssociat e Jiro-Deans Professors fessors

9MOS.

12mos.

9 12mos. I 11108.

2 3 4 6 6 1 7

$7. 500 $4, 7s1 $4, 195 $4. 193roo 194 4, 744 4. 577 3, 512 3,1i30

5, 141 , .1, s13 4. 102 3, 750 3, 14S I 2, s194. 95S 5, 141 3. 731 3, 801 3, 170 2, 9094, 375 , 4, 375 4. 24S 4. 146 3. 4 27 ; 3, 240

Assistant pro-fessors

9mos.

$2, 97"2. s5s

2, 5s22, 677

2, 738

12mos.

instruotors

10 11

$2,1201m7

1, toiti

2. 016233

2, MO 2, 005

411 Z35 1, 8233, 148 3, 242 I 2, 236

2,134

1,638Z 4S3

I Concerning teaching staff in 51 landgrant colleges and universities, Massachusetts Institute of Tech-nology is omitted.4ar

In addition to the regular salaries recorded by Tables 1 to 6.some staff members receive perquisites and for special service, suchas that in summer school or for extension work, are gii-en extra payby the institutions. Many supplement their institutional earningsby outside work for which pay is received. Table 8 shows for theUnited States and for each of the five geographical divisions thenumber and percentage of total staff reported that supplement theirregular institutional salaries in these ways.

TABLE 8.Total number cases with petequixiteR. earnings, andoutside earnings, by major geographiir diriftions

Major geographic divisionTotal

numberof oases

Perquisites

3

North A tlanticNorth CentralSouth AtlanticSouth (.'en URI .Western

Entire United Mates.

2, 0794, 8831, 3831, 8061, ti81

12, 032

Number Per cent

R7 4. 18247 5. os1fIS 12. 14163 10. 13122 6. 48

807 6.77

Additional earn-ings

ber Per oent

Outside tnthg

ber

483990256321324

2, 378

6

23. 2320. 27ig. 5117. 7717. 43

7

19. 76

458831132192280

1,893

Per vent

21 0217.019.34

10.6314.88

15.73

Tables 9 to 14 show the range of these perquisites, additionalinsitutional and outside earnings for the United States and eachgeographical division, and Table 15 the median in each area andin the Uiiited States for the three methods of supplementing regularsalaries. 4

ic

0.--0.111 -,11

it , 12

1 MoS4 wog.

t).57 11.3, 331j

,

i

;.+.

2, 8S4

A

I)mos.

2 50ti,

2,

12

mos.

$2. 7613, OrNS.2., boo

2. 5332, V25

$1. 9912, 00412. o211,9652, 073

fidditionat

_

.....

;Afr4

8

_

;

9

2,

2,

.,

STAFF 577

TABLE 9.-7'obil number of oases with perquimites, additional earnings, and out-side earnings

Up in $2993(X)

MOO .1409$1109-$1.1'.0$1,200 met'

Iii v2.14MOOVIM)$1-1M

$900$1,200 anti ovur

Total .

No tint.i

Up III N2°1

$604)-Poof$900-$1.1,19$1.2tX) mid over

ONInw

No (hri

I. 1) o$300-$51m._$filo0$64911

$100$1,1.1(.1$LIM and over

WHOLE UNITED STATES

Additional outsidePerquisites earnings earnings

. 11433415674

s07

11. 1r2r)

6071, 133

Gas637

451 1956.5 1M

122 302

2. 37s 1. W13

9. i'654 10, 139

NoRTII ATLANTIC DIVISION

"-OM.

143236 139102 4S

35

43

1. 596 1, 621

NORTH CENTRAL 1)IVBION,2

/SOUTH ATLANTIC DIVISION

u 2+4-ta4

71 17421

:40 4ts

247 tre00

4,636 3,

3r) 11'.1

/441 12727 4i113 5

..... _ 4 6

Total 168 256

No data

Up In $291iMO- $5109 .

$nn040499 .

VOR-$1,199..$1,200 and over

Total . .

No data..11011 o..

-

SOUTH ,CENTRAL DIVISION

1. 215

alli. ....11111MIM

1342

1, 127 1..251

27116

291021

183

1,623

no

2718

192

1,614

*1 North Atlantic Maine, No Ilampshire. Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Con.nuoient, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania.

NOrtli Central Division: Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wtsvonsin, Minnesota, luwa, Missouri,Nouti Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas.

South Atlantic Division: 11aryland, Virginia,. West Vitvinia, North Carolina, spud! Carolina, Dela-ware, Georitia, Florida. and Porto Rim.

South Central Division: Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Tow, Arkansasjseid Oklahoma.

,

..maiM .-10 -

Iange

. l

rid . : ... : 71.1

i)1:1! . .

No dal .

r

iii

'!1.199

.

&WI-$:199

..

I

73

.1111

V.

.11

.68a

j

$299. .

.p ....... ._

VI

. .

. .

.

.

1

ft4

:4;

12

15

21'

..... ...... _

- , ...... . -

....... . . .

. .,

- .. . ...

..... - .. ......

PI154(4

7

321

1, 483

58

Division:

.40.*

Total.... .

.

11111E

s31

4,052_

'

111.....

9 29

-

I

578 LAND-GRANT COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES

TABLE Total number of eases with perquisites, additional earnings, and out.. side earningsContinued

WESTERN DIVISION

Range I Perquisites

l'p to $299$:100-$M$J$600-$899 .

$900-$1, 199..$1,200 and over.

Total

No data...INIErior

Additionalearnings

95132661124

328

I, 553

Outsideearnings

Ellb

105

19

40

283

1,601

5. Western Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, Idaho,Washington, Oregon, and California. Also Alaska and Hawaii.

TABLE 10. Median amount of perquiAitcR, additional earnings, and outsideearnings by major geographic dirixions

41111a

Major geographic division

North Atlantic_North CentralSouth AtlanticSouth CentralWestern

Entire United States 1P

Perquisites Additionalearnings

$an $495589 Ssfi465 4395oi 435

54° I457

515 454

lltSideearnings

$4.85

442

486

443

461

Tables 11, 12, and 13 show perquisites, additional institutionalearnings, and outside earnings in relation to the salaries% of staffmembers who receive such supplements to their regular salaries.

TABLE .11. of staff members aceording to salaries

Salary

1

No data$1,999 and less _

$2,00042,999$3,000-113,999$4,000-34,999$5,00045,999$6,000-$6,499$6,50048, 999$7,000-37,999$8,00049,999$10,000-$12,499$12,500-$14,999$15,000 and over

Total

Totalnumber

cases

Perquisites

No data

3

149 144Z 202 2, 0564, 341 3,9753, 257 3, 0811, 323 1,265

463 441 '117 10939 3.596 8730 2410 8

4

$299 andloss

4

1

47fig3.593

$300 to$599

1Z 032 11, 225 164

1

58

663210

4231

0O0

334

$600 to3s99

217546551

1

0000

$900 to$1,199

7

....

9301261

21

222o1

$1,200 nodover

156 to

/..

_

I&

85

20 3013ls

1?2

1, 759-- .

Division:

_

_

-vrt

I

487

2

1 0

157

8

1 1

1

1

11

SS

17

4

3

1

o

33

o1

3

84

21r)0_ .... _ .

_ _ _ _ . .......... .

_ _ . ... ......

_ _

_

_ _ _ _ . _

'

o

!

'

000ooo0

_

STAFF 579

TABLE 12. Additional inRtitutional earnings of staff according to salariem

Yearly salary

1

No data. -$1,999 and lass$2,000-$2, 999$3.000-$3,999$4,000-$4,999$5.000-$5,999$6,000-$6,4 99$6,500-$6,999..$7,000-$7,999$8,000-$9,999$10,000-$12,499$12,500-$14,999$15,000 and over_

Total

..... . .

.....

Totalnumberof mses

2

Additional earnings

No data

149 1412, 202 1, 8524, 341 3, 5893, 257 2, 4981, 323 982

463 345117 9339 3596 $O

. 30_ 2510 9

1 1

4 4

12, 032 9, 654

$299 and

4

1

1622601353511

01

21

000

$300 to$599

$600 to$899

6

4 1

133 233911 61412 164155 11627 585 14o 25 91 2o 1

o ,

$900 to I $1,200and$1,199 over

7

058

181993

0

oO

O

008 1, 132 451 ; 64 I

8

TABLE 13.Out8ide earnings of staff nuthers according to galaries

227333016132oOooU.o

123

Salary

1

No _ - -$1.999 and less$2,000-$2,999$3,000-$3,999 -$4,000-$4,999..... _ _

$5,000-$5,999 . _ _ -

$6,000-$6,499....._

$7.000-$7,999 _ _ _ _

$10,000-12,4W$12,500-$14,999$15,000 and over._ _

Total ow Om

Totalnumber,of cases No data $299 $300

and less to $599

4

149 134 1 1

Z 202 1, 833 84 1424, 341 3, 846 157 1953, 257 Z 782 172 1481, 323 1, 001 134 85

463 352 29 36117 68 15 1539 28 4 296 63 5 1030 24 1 210 6 1 0

1 o o 04 3 0 1

12 032 1 10, 140 605 637

Outsidtiearnings

$600 $900 1 $1,200 I $1,800to $49 to $1,199 to $1,799 to $2,399

O

1864682214224

00

O

2is33.4434952321

00

8

225171622621

21

00o

195 153

1

197

I.131051

o

oooo

57

$2.400 1 $5,000tO $4,999 andover

111

537

8104060200

11

32424725o2oooo

102 49

The assum1)6on is sometimes made that salaries bear a definiterelationship to the training of staff members as evidenced by thede.grees that thex hold. 'Table 19 shows the frequency with whichvarious salarieAre distributed among those whose highest degreesare the bachelor's, master's, and doctor's and among those who holdno degree.

16%

.

less

I Z t

_

_

_

I

I

o O

o

. w .= l

_

-_ _ _

_ _ _

1E. M. Mir-A I

2 7

1

94

2o

.

I

_

_ ...... - - . . -

1

1

.

i

__

_ _ _ _

$6,500-$6,999..... _ _

a. a. 01. at Ow

i.3

I

'10

580

MEP

_LAND-GI:ANT COLLEGES AND UNIVEITIES

TABLE 14.llig1'e.vt degree rereired by taft MenibriIt fireOrililly to maaries- wmf

lar>

1

No data_ _

$1,999 and less .

$2,000-$2,999$3,000-$3,999.$4,000-$4,999. _

$5,000-$5,999. .

3111,500-38,999.$7,00G-$7,999 _ .....$8,000-$9,999$10,000-$12,499.$12,500-$14,999. _ _ _ _ .

$15,000 and over. _

Total _ .

......04444+4. 444.... Wialw.

Totalnumberof cases

1492, 2024, 3413.2571, 3Z3

463117

96

101

4

12, 032

MIMMMIM .0. MM. mom MIM.,,m MEW 1MM - MM...we

rlighe!it degree reeeived

No data No degree A. H.,B. S.

NI. A.. I'll. Mi%(111-1. S. Se. 1). laneous

3 4 6 7

'2013391435210

42 !

1

000

Ws!

119 1, 0321%1 1007sti 1, 10416 3719 1014 230 102

AIIP

0 40 00 1

.=nwiw

31766

I, 57I. 107

404130-27

199

Z1m4

43Ms1n4ho213

5917

63

0.-

4 542- - - w -- 1

43r. I 4. OM '2, 1.49

oo

oo

o

2

Inasmuch as staff members have in many cases pursued studywithout satisfying the conditions that lead to degrees, Table 15 was

prepared in order to show the relationship of saltiries to years of

training above high school without reference to whether sikelt train-ing did or did liot lead to a degree. This table shoal be studied in

connection with Table 14.

TABLE 15. nelationxhip of xts taries to years training abort' high. chool..,.

Years training above highschool

3

No reply ; 622 r 25None 21 01 tti 4 yews 3, Tis 3)4

5 to 6 years 4, 091 327 ears and above . I 4, (XX) 34

dOW

4

172

647

495

3 ,

;-

253 i 1185 5

1, 344 t4445titi

1, 15:1

Yearly salary

7

3K

2733b4627

le 11

10 2 3 1

1 1.10(19 22 5 20

1:18 7 11 16246 66 19 59"

12 13 14

oo1

1

2

ince tiler s been considerable discussion recently in regard tothe money value of higher eduention and of academic degrees inemployments other than those of teaching and research, Table 16"as prepared to show the relationship between degrees held bystaff members and their outside, noninsatutional earnings. Althoughthis table should be used with caution since many factors such as

age, eank, institutional salaries, and the nature of the outside em-ployment tend to render interpretation uncertain, it is at least inter-esting to note the apparent indication that of thos who have outside

or 4111.

.

-

$6,000--$6,499.. . .

_ ...

mi. .

.) Ilr * 52a..

!

:

.

:1109; :

2330 0 14

..

:

D.,

1

50

0

0000

00

I

E

"2 ;

.

eadam.

m1/4

.1

MI

;74

I, 1, 000I L. 2140

1

9

Z15

0 : 00 0 0

10 1

10 : 4 1

10 1 0

-"..-

IS

.-

. _

4. an ...a ana.al

5

aaaaltramaa

1

I

'

I

3 ' ,

_

.

LL.

5

o

-^

STAFF 581

earnings, staff members with the lower degrees frequently earn131wer ¡I I11( )I1 tlt5 Anti is the rase of those who hold the higher degrees.

TABLE 16. High4.4 &time of staff llifinbei.X with relation to otawide earnings

*side earnings

RIP

AL

No reply .... _

$299 and le6s3300-$:)99_$601Smiot)$01$1,1V9 . _

$1,200-$1.799,$1,s00-$2.399_ _ .

32,4(10-$4 .999Si!..000 and over .

Total .

Totalnumberof vases No reply

2 3

10, 131t;11617195153

9453

10649

12, 032

1

ti76

3287

51012

7x1

Highest degree received

No 41,,gree

4

3R41113

4

36

2

435

A . W.B. S.

M . A .,M . S.

3, 831 3, 4411203 222270 206

72 7855 4936 2819 1340 2917 11

Ph. D., M ¡veils-IleOUNSc. I). degrees

1, 7951NO

116333921

10187

alaNimoraamallilDa

4, 543 4, 082 2, 189 2

The relationships that salaries bear to the type of work done byst members. undergraduate instruction, graduate work, research,administration, extension, creative7work other than research, andmaintenance of public contacts are presented by Tables '21 to 27.

Attention is called to the fact that the largest groups of staffmeMbers who devote from 80 per cent to 100 per cent cif their time

,to any type of work -other than administration and public contactsare found in each c -e in the $2,000 to $2,999 range of salaries,while the largestp«íhber spending from 80 per cent to 100 per centof their time upon administrative work is found in tlie salary rangefrom ,$3,000 to $3,999. Tables 17 to 23 will repay careful, detailedstudy and analysis.

TABLE 17.Pcreentage of time staff members devote to undergraduates withreference to salary range

Salary

No data$1,999 and less.. _ to

$2,000-$2,999V,00q-$3,999$4,00044,999

svi00-$6,999.....

$10,000-$12,499..$12)A00-$14,999115,000 and over

a a. al.

'Pot&

Totalnumber

of1'3 ItieS

Percentage of time devoted to undergraduates

Nodata

No 19 Pertime lent or

leeks

20 to39 percent

2 3 4 5 1

149 52 22 4 92. 20r 687 275 65 1444, 341 981 1, 004 75 1633, 2A7 M1 K51 122 3121, 3Z3 117 XIS 117 272

463 40 78 75 120117 8 24 19 3439 7 10 13 596 16 29 13 2230 a 12 0 210 0 10 o o

1 04 1 0 04 2 2 0 0

12, 032 2, 427 2, 563 1109 1, 083

40 to59 percent

7

19301287393229

9121

210

oo0

60 to79 percent

.3(4

1118144550723742

7o

oooo

5

1,486

80 to100 percent

32549

1, 384561114

17421

30oo

Z 671

111400*---30--VOL to 394

Ask

-S--

1

1

:245

. _ _ _ .

- _ .

a

.

_ ...

.1

_ .. ____. ...

3

r...111.

7 8

2

p 0

1

_ _ .

$5,000-$5,999$41,000-K499 ........ .

$:',000-$7,999$14,000-$9,991 .

UNIMINIDCtst,_

. -..

8

. - =m.

I)

.

.

.

.

1

i

. .

_

_

6

............

.

.

--

582 LAND-GRANT -COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES

TABLE 18.Peroentage of time which staff members devote to graduates withreference to salary range

A

1

No data$1,999 or 10411$2,00042,999. . _ _

$3,000-$3, 999 . _

S4,000-44. 999SS, 000 -$5, 999$6,000-46,499S6,500-$6, 999$7,000-S7,999$8,000-$9,999$10,000-$12,499$12,500-$14,999$15,000 and over

Total

Totalnumberof cases

1492, 2024, 3413, '2571, 3Zi

4631173996:SO

101

4

12,032

I No data

3

57885

1, 03553612441

87

168o02

2, 719

Percentage of time devoted to graduates

No time

4

19 pervent or

less

761, 223 44Z 816 :1111, 77s 608

553 371151 15142 2.%

13 934 1715 68 1

1

1 0

20 to 39 40 to 59160to791sOto100per cent per cent perueut per cent

034

125243206

26

231

oo

7

1

142776542S10250o0o

8

O

1

9133301

O

oo

tS, 723 1, 555 75N 217I

3ti

9

1

1

9

22o0000oo

22

TABLE 1,9. Percentage of time which staff members derole to research withreference to salary range

SalaryTotalnum-ber ofcases

1 2

No data$1,999 or lessS2,000-$2,999$3,000-$3,999. _

t$4,000-44,999. _ ......$S,000-$5,999.. .$6,000-$0,490E500-$6,999 .,000-47,999 _

,000-S9,999$10,000-$12,499$12,500-$14,999$15,000 and over

Total _

1492, 2024, 3413, 2571, 313

46.111739963010

1

4

Percentage of time devoted to research

Nodata

0_

2

Notime

1i1 per 20 tocent or 39 per

less cent

4 a s

66A51

2, 3671, 693

(I 25

1s65016

4016

91

2

12,032 2, 640

10 I

126 158381 234452 256292 157109 8329 22

51:1 184 21 00 00 0

5, 922 1, 424 I 939

40 to59. percent

7

1451191346328

548oOoo.

60 to79 percent

8

1

346463339201

00O

O

SO to100 petcent

387

14411924

71

1

1

0ooo

513 387

I.

- - -

Salary

_

OOOOO . MI

0".

0

_

11

85

7

-*.

.

. .

3

II

56803

1, allMO12941

8

15

0

-4

207

"

\.,

4M.

A

41

1

_

.. ...

....1

_

_ __ ...... . - ......

6

1111171P11

STAFF 583

TABLE 20.Pereentage of time which. staff members devote to administrativework with refreneeo to salary range

SalaryTotal

number'of cases

2

Nt) data. ..... _ _ 149$1.999 or less_ 2, 202

_ _ . 4, 341_ 3, 257

._k000-144.999. _ _ 1, 323463

14.0oo-$6,499 _ _ _ 117

$4.500-$4. 999 39$7,004-$7,999..14+,0m-$9,s090.

.$10.(m- $12,499_ _ 101

$15,(XX) and over_ _ . . 4

Total . 12,032

Peroentage of time devoted to administrative work

No data

3

56882

1, 02952312039

8

168002

2, 690

No time

4

601, 097Z 3771, 331

294641628320o

5, 254

19 percent or

less

5

15146

681435460151286

18oO

oo

2, 440

20 to39 per-cent

928

118263245

92196

201

000

46 to59 percent

7

21950S4

* 92532210

112000

345

60 to79 percent

8

44

214046291038

2

o

173

80 to100 percent

32665816635145

15118o2

329

TAME :ILPerm/law, of time staff members devote to extension work withreference to salary range

Salary

1

No data. _ - mi

$1.999 or less$42,0(xi-$2,999$3.00(,- V3,999_ _

$4,009-$4,999.s.r),(01--$5,SM)$4;,ono-$6.419$60-$6,999 _

$7,00(1-$7 ,999.polo-$9,999$1000-$12,490.__$12,500-$14,999$15,000 and 'over__

Totaltab

.....

Totalnum-ber ofCaSeS

2

Percentage of time devoted to extension

No data

3

149 57Z 202 892,4,341 1, 0333, 257 5391, 323 128

463 42117 839 796 1630 810 0

1 04 ! 2

12,032 2, 732

No time

4

741, 1412, 2671, ,624

772307

7119

1

2

19 percent or

less

6

668

302444257

13

oO

O

6, 400 1, 187

20 to39 percent

40 to 60 to59 per 79 percent cent

80 to -

100 percent

7 8

1

19

79541331

01

200

1141118 3

23 2341 3019 13

10 01 01 00 00 00 00 0

1071

6475008091

1

31

000

219 101 70 1, 3Z1

a 0*

J.

7

11$

_

$2,000--$2,999

.... ...

4)6

4.../...1.

5

1

its, ...+0

_

_

.*

_ .

L.

02

-

84

7

51

46

0

7

.`)

$3, 0( )0 :M,999.... ,-

_

V.00q- $:), 999

7

_

1

i, .

__ !, 1

!...

801

14.4 11

_

_ -

_ __...._

22

8

111.

.AP

LAND-GRANT COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES

-s 'relax 22.--Pergentage of timo Bran' members devote to creative work other thanresearch with reference to salary range

Salary

No data$1,999 or less$2,000-$2,99912,00043,999$4,000-$4,999...$5,00045,999- - - -$6,000-$6,499,_ ...... -

$6,500-$6,999-$7,000-$7,9910$8,000-49,999$10,0(X)412,499$12,500-$14,999_____$15,000 and over__ _

Total

t.

a. ea .101. ea OW

Totalnum-ber ofcases

2

1492, 2024, 3413, 2571, 323

46111739

3010

1

4

12 032

Percentagef of time devoted to creative work

Nodata

57g92

1,041.143

1324287

168002

Z748

4

771, I M2, 7672, 097

86228585255818812

7, 439

19 peroerlt Or

less

no25,830420079

13Ir

3ooo

942

20 to39.percent

40 to59 percent

60 to79 percent

7

44197

145$O31

72

O

oO

5

413

8

10tcent

1

19 5ril 3162 323016 9

1 2)

1 11

1

031

12

1

1

000000

197 205

TABLE 23.--fercen1aifr of time staff members devote to public contacts withreference to salary range

Salary

'1

No data J .

$1,999 or less$2,000-$2,999$3,000-$3999$4,W$4,999----$5,000-$5,999.$8,000-36499---- - _ .

$6,500-$6,999____. _

$7,000-$7,999$8,000-$9,999

_912,500-$14,999. _ ... _ _ .... ....15,000 and over.

Total_ _ _ .

Totalnum-ber ofcases

2

Percentage of time devoted to public contacts

Nodata

3

149 552, 202 gM4, 341 1,0283, 257 5351, 323 126

463 4113917

796 lti304-10 0

1 04 2

12, 032 2,710

Notime

6R1, 1362,191,r15

56316343103412

1

o1

fly 188

19 percent or

less

2215.5766997MC243

rig1t4409

oo

2,911

20 to39 percent

315413232i

fi461

21

1

157

40 to59 percent

AO to79 percent

7

04

141230

o001

0O

35

oO322

SO to1(K) percent

1

7

4

1

'2

0000000

4.1

s

23

s.

_

_

.

96

I

Notime

8

1

r

-

e

5 5

5 0

.

1

oo

74

7

......

. ..

4 6

Kl39 .

...

g. . 6

-. rte.

1404,7-7

.!

.

1

10

9

.4

584

1

_

_ _

...

5

I.

0

000o

88

_ .

_

_

_

_

8

oooo

STAFF 585

Administrative officers sometimes gfiiie that salaries are adjustedsomewhat in accordance with the family responsibilities of staffmembers. 'Tables 24 and 2 5 give the yearly salaries of staff mem-bers accordiNi to their sex and marital status and With reference tothe number of their children.

TABLE 24.Yearly milary of xfafr membcrx according to their sex -and marital

;a111-11$

male11;irrielI male\I OM' erDivorred I11:iie

Married female..

Divormd female

Total _

TABLE

2

NtatuN

r-1,3

C, ??:«.

73) likvig --_

?...^-

Z-4 a'03 Sri.

3 4

14 s71: 2f; 7c7 715102 723 2, 4:10

29 1 0 1

119 4 26I, MI) I A"' In 574 981

230 3 95 ' 1055 , 11

98 0 .34 if 41

12, 032 149 2, 202 n4, 341

, u 1

Yearly

Yearl salary

- --7

¡ 1,323 4f)3

2".2,,i2-

--4.1-'.;?':4; 4

18 1 11 12 13 14 14

.C4 t:o- .4o 40*44 49 I 13

7 0 4 '2 1

1004 3S 87 . 26 100 0

2 1 4 1 00 0 0 0 0o 0 0 i n

, 0o o o 1

117 39 95 31 11 1 . 4'

salary of xtafr weinberx with referenre to vumber of children

Number of children

No .

No childrenOneTwo...ThreeFourFive or more

Total

Tot alnum-ber ofcases ;

2

297 5 9S5, 761 116 1, fIcA2, OM 16 2212, 032 i 33 1251, lOti Isi 62

485 7 is 20281 , 4 13

..1 12,032 149 2, 202

Yearly salary

7

125 49 132, 48'2 1, 099

745 I M I '279541 774 350249 413 226105 177 10674 94 -

4,341 3, 257 1,323

310782

12S7744

f.....463

2 0 0Zi 9 13

21 II 21

33 9 2327 20

4 3 127 4 7

......mg117 , 39 96

12

2

)

40

30

Is 14 15

0 00 0 11

0 0 1

5 0 Il

3 0 02 1 0

0 2

10 1 4

The economic pressures that arise from marriage and family re-sponsibilities are frequently supposed to force college and universityfaculty members to turn their energies to outside employment inorder to supplement their institutional incomes. Women are usuallysupposed to have fewer Opportunities to secure 4mtsi41e employmentthan men staff members. The facts in regard t o" annol outside

000

"50.

e%E.

Sim: le

Single 1ezni1ti .

_

W How.

,00001

alb

-I.

; !

'2.

20 0

. i

.1.42 r17 252,118 1,192 412

9 7 I. 1

44 22 13

272 37 10

245 0 , 0

21) '2 .1-

3, 257

- I L-lc31-1:28P;

N

I

eq49

0 01 4

0 0 00 -0

o 0o o

O o .0. o oo

1

25.

!

reply.

.

..

5

o

3 4

... ...=

.

. .

.; . i

295

54

8

22

itE'Eg2 '212 s§ § §

ziti9 le 11

i4

' _

4

s

0

.

ft

E

:4)x onirit

!

.

.I

-C

§

.111

1

_

§Ì*

;

'

!

0

;

1

I

.1

,

0

$

'586 LAND-GRANfl4 COLLEOES AND UNIVERSITIES

earnings of land-grant college staffs are presented by Tables 26 and27 with reference to sex and marital status and with reference tonumber of_ children.

TABLE 26.Yearly outside earnings of staff members according to their sex andmaital status

Sexmarital status

Single male. _ _ _ _ _

Married maleWiTiowerDivvrced maleSingle femaleMarried female_ _WidowDivorced female._

gUPP

. Total .

Totalnumberof cases

2

Outside earnings

No data

3

s76'7, 771 6, 263

29 ev)

2098

12, 032

$299 $300and toless ï $599

71499

1

435

5O3

132469

06

20324

618 636

$600 $900to to

$899 ! $1, 199

7

$1. 200to

$1, 799

21 1 17 11159 126 71

3 1 o5 4 1

7 5 90 0 1

0 0 1

0 0 . o

195 153 94

$1, ROOto

$2, 399

340

1

1

7

o

$2. 400to

$4, 999

19

$A000ando

11

2 299 45

1 01 1

3 1

0 00 0ol 0

53 I 106 49

TABLE 27.Yearly olitgide earnings of staff membersof children.

TotalNumber of children number

of cases

No reply _ _ 297No children 5, 761One _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Z 068Two. _ . _ _ _ _ _ _ . 2, 032Thre1/2 1, 108Four 485Five or more_ . _ _ _ _ . 281

121 032

No data

2745. 1041, 6951, 599

871370227

$299andless

11189106148884815

10, 040 605

MOOto

$599

264142128

2715

with referenre to number

altde earnings

$60110 $900.to , to

3899 $1,199

6 7

272 '47352310

737 195

242254521135

153

$1,200to

$1,799

$1,800to

$2,399

$2,400to

$4999

$5,000andover

8 9 10 11

1 1 0 136 12 31 1113 10 19 1116 14 31 lf18 10 17 48 2 3 42 4 5

94 M 106 4G

Although recent studies tend to show that there is close corre-lation between the salaries of institutional staff ,members and thequality and effectiveness of faculties, many considerations in addi-fion to that of earninp attract men to service in educational insti-tutions. Scholarly tastes, desire fer intellectual freedoml belief inthe value of education, the wish to be of service, interest in and likawing for young people,.and many other personal reasons may induce

^ men and women io accept and remairk in college and university posi-tions that are relatively unattractive from the standpoint of moneycompensation. Especially is this likelx, to be true of men whoseinterests lead them to acquiié th6 higher academic degrees.

_ .

_ .

_ _

_

_ _ _

_

. _ _

1 n17

119 9f11, 889 i8O2

23ri no17191

10, 128

8

.46

__

2

......_

.

,

.4

4

Total... _ _ .

;56

' 6

4,

.. _ ......_

...

'

do-

ottace4=?°77",....444iA" T7'

F

1

_

a -

5

_

.44o

STAFF 587

Presentation of staff qualifications arm interests solely with refer-enoe to salaries and other earnings may tend, therefore, to distortsomewhat the emphasis that should be given to evaluation of insti-tutional faculties. It is desirable to consider some of the elements oftraining and experience of staff members in the land-grant institu-tions without reference to the salaries that they receive. The follow-ing tables, therefore, are concerned solely with the preselation offacts concernini; the training, experience, affiliations, activities, and

... academic advancement of staff members.One interesting basis for study. of tile staffs a land-grant insti-

tutions is that afforded by the distribution of degrees in tb five

geographic areas and in the United States as a These dataare presented by Table 28. The western area °shows a smaller Per-centag6 of staff members with no degree than any other region,while the South Central states have Olt largest koportion, of staffmembers who have never obta!ned even the bachelor's degree. It*ill be noted also that the North Atlantic States have file smallestproportion whose highest degree is the bachelor's and the SouthAtlantic the largest percèntage with this amount of formal Oucation.The South Central and South Atlantic States also rank low Withreference to tile proportion of staff members who have doctor's de-grees. Although averages and general practices afford very unsatis-factory standards of judgment it would seem that the South Nntraland South Atlantic land-grant institutions might well give consid-erable attention to raising #e level of training for staff meinbership.

, TABLE 28. Degrees earned b Bluff membarR, accord ing to ma jor gwgraphiod iri8iuns

1.4

Major geographic division

s

North Atlantic_ _ .......North CentralSouth AtlanticSouth CentralWestern se'

Entire United States_

Totalnumberof cases

2,0794, 8831, 3831, 8081, 881

Highest degree earAl

No reply

Num-ber

109230151172121

12, 032 783

Percent

5. 244. 71

10. 929. 526. 41

6. 51

A . B., B. S. I M. A ., M. S.,or correspond- or correspond-No degree ing baccalau- ing master'sreate degree degreb

Num-ber

Peicent

damiNImEN

64 3. 08151 a 0964 4. 63

100 & 5456 2. 98

435 & 62

Num-ber

Per Num-cent ber

7

7061, 834

580723700

33. 96 71437. 58 1, 77741. 94 40840. 03 59737. 21 586

4, 543

Percent

34. 3436. 3929. 5083. 0831. 15

Ph. D. 9r Sc.1). or Arre-sponding

doctor's de-gree

N um- Perber cent

11 o

486 23. 38891 18. 25180 13. 01214 11. 85418 22. 22

37. 78 I 4.082 33. 93 2,1894111

18. 19

A few vurious and unusual degrees pre included in this classification.

whçte.

,

- - - - -

0

1

4 44

.

'

s I le

I :1°,2_ I

-11

I

4

AA.

"1dr ^-,1 -.7 0.--

-tt

Il

.4.--!;

t;;M,"--'

- -

IIww

.1.1111.1101r.

issf

4588 LAND-GBANT COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES

The ass,d,ion is omoin s milde that staff members have con-si,ieralde training Iwyond t Iiit indicated by the 'highest degrees theyhold. Table %V:1S constructed to ShOW the number of years trail:.ing above high school that haS bee* received by the land-grantcollege staffs in the five geographic areas and in the United States ata whole. It will be noted that upon this basis the South Atlanticand South Centyal Stites are high in the proportion of those whohave not had more than four years of such training and low in thepercentaire that has seven yenrs or more of training beyond the highschool.

TAW E 29. Numbe of years frainhig abort. h iyh Nrhs )(01 bY jor geographicix ion

Major geographicdivision

Totalnumber

, of cases

North Atlantic. .. 2, 079North Central _ . 4, m3South Atlantic . _ . I, 383South Central 1, 806Western 1, 881

. _

ntire United States _1 12, 032

Number years training above high school

No trainingNo reply above high 1 to 4 years 5 to 6 years

school7 years or

MOTE

Num- Per 'Num-1 Per Num- Per Num- Per Num- Petber vent ber mit ber cent , ber cent her cent

3 4

125 i.oi. 01$4 ; 3.76 i 1468

1434.917. 91 3

101 , £ 42 1

622 5.16 21/

557 211. 79 613o. l,iyO ?A. 37 1, 7s3

. 21 464 43. 55 456

.16 616 :4. 10 575

.05 471 25. 03 664

lo 11

29. 48 78436. 51 1, 71232. 97 39231. 83 46935. 03 643

37.71135 On

28.3425.911

34.18

. 17 3, 298 27. 41 4, 091 34. OU 4, 000WNW

Training of college faculty members in Professional educationsubjects is being advocated very *widely. In order to 'determine theextent of such training that the staffs of land-grant. institutionshave had, Table 30 wakconstructed upon the basis of individualquestionnaire replies. It wilt be noted that ,the South Atlantic andthe. South Central States haNg the smallest proportiori of staff mem-bers who have laid no training in professional educatioii . subjectsand that relatively large percentages have reeti4d 21,$!mester hoursor more of instruction in this field. Apparently a considerabledegree of dependence being placed upon training in education bythe land-grant institutions of these States. The q.uestion may beraised whether such training is regarded in some *sense 'as a substitutefor the usual academic degr6es.

Table 31 shows' for the entire United States the relotionship ofthe mimber of einester hours of professional education to the highestdegreetopeld by staff members.

tiJ aW4

33.2i

29

ma

2

!

;

: 3 6

;

.

.

. 1

4

, i

3

F

.

li

.

is

_

I

_

1 2:4

I

,

f

I

STAFF 589

TABLE 30.Training in professional education. by major geographic divisions

Major geographicdivision

Totalnumber

cases

NortTi Atlatitic_North CentralSouth AtlanticRouth CentralWestern

Number semester hours of professional education subjects

No reply

Num-ber

3

..M.M=.1111

No profession- 1 to 11 semes- 12 to 23 semes- 24 or moreal training ter hours1

ter hours I

Per.

NuM- Per Num- Per Num- Percent ber cent ber cent her cent

Per N um-cent I her

2, 079 1, 135 54, 594, 8K1 2, 1s3 44. 701, 383 407 58. 351, 806 878 48. 621, M65 45.

Entire UnitedStates 12, 032 I5, 868 48. 77

250 12. 03592 11 12

79139 7. 70208 I 1. 06

a

285 13. 70636 13. CO149 , 10. 78'222 11 29242 11 86

1, 268 1 54 1r)1'34 . 12. 75

197 A. 48789 16. 16145 10. 48276 15. 21;277 14. 73

11

212

203291289

1, 684 14. 00 1,678

12

10. 2013. 9914. 6816. 1 11.36

13. 94

TABLE 31. Highest debrec of staff mombers with reference to semester hours ofprofessional training in educaaon

TotalSemester hours4professIonal training number

of eases

Nd replyNone1 to 1112 to Zi

and more

Total

2

5, 8681. 26g1..r).351, 6831, 678

032

Highest &Rite received

No reply

69216222528

783

BNo degree AS:'

4

30836273133

435

Z 336395551681580

M. A., Ph. D.,M. S. Sc. D

s. 7

1, GR5

39558269172g

, 4. 543 4,082

847426353255308

2, 189

Inasmuch as teaching or administrative experience in the publicychools usually presupposes some instruction in professional educa-tion slit:leas, it is interesting to note the plationship that suchexperience on the part of land-grant college staffs bears to semesterhours of professional training. The data are presented in Tables 32and 33.

/1.TABLE 32.Secon4ary Rehool teaching expc joule of stair member* according tonumber of semester hours of professional training moeived

Semester hours of profemional training

No reply .None .I to 1112 to Zi24 mid mow

Total.. .

1116,M1.

Totalnumberof rases

Number of years spent tftehing insecondary schools

No reply None...111maillepolloMM.2..

868 1, 793 2, 7621, 288 192 i4641. 535 348 a3t)1, 375 6 4141. 678 377 1 2:04

... 12, 032 3, 085;

4. 907

1 to 2Years

114271388343

1, 701

3 Years ormore

728. 98

2f10

744

2, 346

a

1 2

_____ _

. _ .

!

4

5. 71

1

;

I

10

6K4

_ _

1

24

c 11

B.I

1

. .

. _ ......

........ _ .

I

3 a 6 $1.

A. 586. .

.

ten-- - ..ararmlbrom1- lorw-...-... i

on_

I

.

3

.. _

......._

590 LAND-GRANT COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES

TABLE 33.Number of tram, spent by staff members in a principalship or super-intendency with reference to professional training

semester hours of professional training

No replyNone1 to 1112 to 2324 and more _

Total

Totalnumberof cases

2

Number of years spent in principalshipor superintendency

No reply

5, 8681, 2681, fa 51, 6831, 678

12, 032

Z 641348723969230

4,911

None

2, 767868637417937

1 to 2years

21530

100168215

5, 62Q.. 728rts

3 years Ofmore

2452275

129

. 296

767

In connection with the teaching experience of staff members itis interesting to note the regions in which teaching of agriculturein the public schools is most frequently an plement of staff experience.Table 34 presents the data %available. It will be noted that a largerproportion of the staff in the South Atlantic States has such expe-rience than is the case in any other region.

TABI.E 34.Yeara spent teaching agriculture in secondary schools by geographiclocation

Major geographic divisionTotal

numberof cases

Years spent teaching agriculture in secondary schools

No reply

Num-ber

North A tlanticNorth CentralSouth AtlanticSouth CentralWestern

Entire ['cited States..

Z 0794, 8831, Xi1, 8061, 881

Percent

None

Nunkber

Peroent

1, 063 M. 13 918 44. 162, 391 4&99 2,083 42. 65

669 48. 37 546 39. 47669 37. 04 969 53. 66

1, 039 55. 23 691 36. 76

12, 032 5, 831

1 to 2 years 3 years or more

Num-ber

percent

7

52204909588

2. 504. 176. 535. 264. 67

Num-ber

Percent

46205

787363

11

48. 48 207 43. 27 529 4. 39 r 485

2214.195.63t 043.34

3.86

ver...111

Another method of judging the interests and activities oikuntversityand college personnel is afforded by the records of their publi-cations. Table 40 indicates for each geographic region the numberand per cwt of staff members who productd in 1928 research publi-cations only, popular publications only, .and those who produced bothresearch and popular writings. Attention is called to the pumberthat failed to furnish information in regard to publications. Itappears probable that the large proportion of these omissions weredue to the fact that staff members had no publications to report. Inthis connection it should be noted that the South Atlantic and SouthCentral Stateoshow the largest percentage of failures to furnish

-

.

3

i

4

'

____ ..

=e-

..,

4

a

.

I

.

5,

.

.

w.

3

4.r

111111111'--STAFF 591

information and that gley. also show a small percentage reportingresearch publications and an even smaller percentage reporting bothresearch and popular publictitions.

TABLE 35. Number and per eent of 8taff members who had publications duringthe year, with reference to geographic location

Major geographic divi-sion

Totalnumberof cases

North AtlanticNorth CentralSouth AtlanticSouth ('entralWestern

Entire United States.

2

Ntimber who had publications during year

No reply

Num-ber

Percent

4

079 I 1, 032 49. 644, 883 1 2, 666 54. 601, 383 904 65. 361, 806 1, 225 67. 831 881 1 025 54. 49

12, 032 6, 852 56. 95

No publi-cations

Num-ber

Percent

Researchpublications

only

Num-ber

Percent

6 s 7 8

38 1. 82 401 19. 2932 . 66 905 18. 53

7 . 51 155 11. 2115 . 83 236 13. 07

1

4 . 21 342 lg. 18

96 . 80 Z 039 16. 95

Popularpublications

only

Num- Perber cent

le

270 12. 99589 12. 06173 12.51156177 9. 41

1, 365 11. 34

Both researchand popularpublications

Num- Perber cent

11

338 18. 26691 14. 15144 10. 41174 9. 63333 17. 71

1, 680 13. 96

Another distribution of tilt publications of staff members in theland-grant institutions is shown by Table 36, which indicates thenumber of staff members holding various degrees who have pro-duced resparch publications only, popular publications only, or bothresearch and popular publications.

TABLE 36. Number of staff members who had publications during the yearwith reference to highest degree received

Highest degree received

No replyNo degreeA. B. or B. SM. A. or M. SPh. D. or Sc. 13Miscellaneous

Total

Totalnumberof cases

781435

4, 5434, 0822, 189

2

12, 032

Number who had publications during year

No reply No pub-lications

680372

3, 2701305

3932

6, 852

Researchpubli-cationsonly

273 14

39 35633 742

4 9010

96 2, 040

Popularpubli-cations

only

Bothresearch

andpopularpublica-

tions

7

4135

598552138

0

1, 384

2511 .

280820744

o

1, 880

Still another measure of staff participation in the intellectualactivities of their craft is afforded by membership in and attendanceat the meetings of professional and scientific organizations. Tables37 and 38 present information in regard to these matters. It appearsprobable in the case of these data that failure to reply indicatesfor the most part lack of membership and failure to attend meetings.

a

2,

I

K. 64

_ _____ ..... -

3 4

8

o

jb.

I.

.

Z

692 LAND-GIRANT COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES

This assumption is supported in part by the fact that the two regionsshowing the largest proportions of failure to reply show also the:mallest percentages of memberships and the smallest proportion,of attendance at meetings of professional and scientific organizations.TABLE :-37. Membership or stuff in professional and "¡entitle oryanizatiow by

yevgraphie locat

Major geographic division

6

North AtlanticNorth CentralSouth AtlanticSouth CentralWestern

Entire United States__

Totalnumberof cases

2

2,0794, 8831, 3831, 8061, 881

12, 032

Membership in organizations

isTo reply

NUM-ber

3

442NU:42

680488

Percent

21. 2624. 4539. 1937. 6525. 96

No member-ship in organ-

list ions

Num-ber

a

710491

3, 346 27. 82 31

Percent

I.

0. 33. 20. 28. 49. 05

1 to 5 organi-zations

Num-ber

7

1, 383 NC 523,048 62. 37

713 51. 55980 54. 2ti

1, 124 59. 75

organizationsor more

Num-ber

Percent

11

247 89633 12. 98124 8.98137 7. 60288 14. 24

. 25 7, 246 60. 22 1, 409 11. 71

TABLE 38. Attendance of staff at professional and scientilto organization, meet-inils by geographic location

TotalMajor geographic division

j num.ber ofcases

1

Attendance at organization meetings

No reply 1

Meetings of 1No attendanoe to 5 organiza-

tions attended

Num-ber

2

North Atlantic _____ 2,079North Central 4, 883South Atlantic 1, 3183South Central 1, 806Western 1, 881

Entire United States_ _1 12, 032

9171, 899

768988721

Peroont

Num-ber

44. 1038. 8955. 5254. 5938.33

10353379

188359

Percent

INum-

ber

7

Percent

Meetings of Rotmore organiza-tions attended

Num-ber

Percent

11

4.97 1, 012 48. 6710. 91 2, 288 46. 815. 73 503 38. 37

10. 29 603 33. 3819.08 783 41. 62

5, 291 43. 98 1, 260 10. 47 5, 187 43. 11

47165333118

294

2. 26 ;

3. 392. 381. 74

. 97

2 44

Twenty or twenty-five years ago it was sometimes the 'custom forinstitutions to grant with considerable liberality honorary degrees tostaff members who suffered from the academic handicap of not havingearned graduate degrees. This practice has fallen into disrepute dur-ing the past generation, and honorary degrees may now be regarded'as indicating the probability that those who receive them have ren-dered service .of some distinction. It is interesting to note therefore,in TaOle 39, that a larger proportion of the staff members in theNorth Atlantic States hold honorary master's and doctor's degreesthan in any other region. The obvious inference that the staffs of

i

.

# e # 0e e .....

.

4

.

'

Percent .

[

I 8 11

N1t542

.6

9

STAFF 593

land-grant institutions in the North Atlantic States contain a rela-