Strategic Donations: Women and Museums in New Brunswick, 1862-1930

Transcript of Strategic Donations: Women and Museums in New Brunswick, 1862-1930

lournal »/Canadian Studies • Revue d'études canadiennes

Strategic Donations:Women and Museums in New Brunswick,

1862-1930

Lianne McTavish

This essay emphasizes the contributions made by white, middle-class women to the Museumof the Natural History Society of New Brunswick, founded in 1862. Archival sources revealthat women funded the museum by organizing entertainments, bazaars, and high teas.Aifhough excluded from fuli memtwrship in the Natural History Society, they found waysto represent themselves in the museum's collections and acquisition records by employingthe gendered strategy of gift giving. Studying these women does more than add detail toexisting museum narratives. It sheds light on the shifting historical definition of museums,indicating that their economic function has changed since the nineteenth century.

Cet article met en relief les contributions apportées par des femmes blanches de ciassemoyenne au Musée de la société d'histoire naturelle du Nouveau-Brunswick, fondé en 1862.Les archives nous révèlent que ce sont des femmes qui ont fondé le musée en organisantdes spectacles, des ventes de charité et des dîners. Bien qu'elles n'aient pu être membres àpart entière de la Société d'histoire naturelle, elles trouvèrent un moyen d'être représentéesdans les collections et les registres d'acquisitions du musée par une stratégie propre au sexeféminin : le don. L'étude de ces femmes fait plus qu'ajouter des détails aux récits du musée.Bile permet de comprendre l'évolution de la définition historique des musées et indique queleur fonction économique a changé depuis le XIX'' siècle.

For the past 30 years, publications on the history and theory of museums have

focussed on the institutional representation of national identity, the politics

of display, and the ways in which various memhers of the public have been

either addressed or excluded by museum practices (Coombes 1998; Bal 1996; Dun-

can 1995; Bennett 1995; Kaplan 1994; Karp and Lavine 1991; Bourdieu and Darbel

1969). The articulation of gender within museums has at best been considered a

secondary concern. A few scholars have examined the representation of women in

particular museums, the changing role of female museum workers, and the goals of

such wealthy collectors as Isabella Stewart Gardner and Gertrude Vanderbilt Whit-

ney (Canier 2006; Porter 2004; Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum 1997; Hyde 1997;

Yablonski 1993; Duncan 1993). In a recent doctoral dissertation, Leslie Brooks-

Marsden, for example, analyzed the gendered careers of female scientists working

Volume 42 • No. 2 - (Printemps 2008 Spring) 93

Lianne McTavish

in American natural history museums during the late nineteenth century, arguingthat these women hecome visible only when museums are considered legitimatesites of scientific inquiry (2006). Other theses have considered the production ofmasculinity in early museums in both Europe and the United States, investigatinghow, for instance, American Charles Willson Peale staged his identity in displaysof his spectacular collections during the nineteenth century (Fernandez-Sacco1998; Mclsaac 1996). Comparatively little of this work has emphasized eitherwomen or gender in relation to Canadian museums, though a notable exceptionis historian Brian Young's chapter on what he calls the women's culture fosteredin the McCord Museum in Montreal from 1921 to 1975 (2000, 80-111). Accord-ing to him, white, middle-class, conservative women were able to manage thecollections witb a degree of freedom because of McGill University's continuingambivalence about the value of the museum.

In this essay, I argue that attending to both gender and the role of womenin early museums can undermine traditional definitions of these institutions.Instead of appearing as discrete spaces in which objects are amassed and arranged,museums begin to emerge as contested discursive mechanisms that enable aswell as erase gendered identities. Taking gender into consideration can further-more reshape critical museum theory by challenging contemporary dismissalsof the renewed emphasis on entertainment in museums. Scholars now regularlybemoan the increasing number of spectacular "blockbuster" exhibitions designednot to provide educational opportunities but to attract a broad public to particu-lar museums, raising funds through entrance fees and purchases made in thegift shop (M. Berger 2004, 47-80; Luke 2002, 15-16; Young 2000, 3, 123). Oncewomen's contributions to early museums are evaluated, however, the longevityof such entertaining activities becomes apparent. During the nineteenth century,women were often involved in staging various events and sales within museumsin order to fundraise for the institutions. Insisting that these activities have littleplace in contemporary museums not only overlooks the economic strategies usedto construct existing museums, hut also risks dismissing the methods employedby women In their role as early museum builders.

I make my claims in relation to the history of the Museum of the NaturalHistory Society of New Brunswick, founded in Saint John, New Brunswick, in1862. This organization was the primary precursor of the New Brunswick Museum,which was designated a provincial institution in 1929, and officially opened in animpressive new building by Prime Minister R.B. Bennett in 1934 (McTavish andDickison 2007). Unlike many early Canadian museums, a substantial number ofrecords survive to document the Museum of the Natural History Society. As Icombed through the archives now housed at the New Brunswick Museum in SaintJohn, I was nevertheless surprised by the lack of detailed references to the women

94

Journal of Canadian Studies • Revue d'études canadiennes

who had been active in the Ladies' Auxiliary of the Natural History Society,begun in 1881. For tbe most part, members of the Ladies' Auxiliary were men-tioned only briefly in the handwritten minutes of the Natural History Societymeetings held from 1862 to 1932; at the end of some entries, unnamed "ladies"were thanked for having provided refreshments. Supplying tea, cake, and icecream was apparently the principal task of the Ladies' Auxiliary, and the scantyrecords that mention the women also attest to how they formed special com-mittees to prepare food for the annual conversazioni, events to which the generalpublic as well as dignitaries were invited to hear talks given by male members ofthe society.

One frequent speaker on these occasions was George F. Matthew, long-timepresident of the Natural History Society. This amateur geologist and palaeontolo-gist gained international praise for his work on local fossils, especially the Cam-brian trilobites embedded in the slates beneath Saint John (Miller 2004, 2003). Thediscoveries made by him and other male members, including Professor FrederickHartt, were celebrated in the official seal of the Natural History Society (NHS), cre-ated in 1886, as the society's minutes record on 5 October (NHS 1862-1901). Theoldest trilobite of the Saint John group, the Paradoxides Acadiens, was shown sur-rounded by images of fossil plants and crowned with a bird, in recognition of theenergetic ornithology committee. In contrast to the official attention paid to thesemen, Katherine Matthew (Mrs. George F. Matthew), intermittently president ofthe Ladies' Auxiliary between 1881 and 1922, was remembered for having bakedcookies stamped with a mould made from one of the famed fossils. According toHarriet Holnian, the secretary treasurer of the Ladies' Auxiliary, "No social gather-ing or field day of tbe Natural History Society would be a success witbout [Mrs.Matthew's trilobite cookies]."

My initial reaction to tbis information was disappointment. By compilingreferences to the women involved in the Natural History Society, I had produceda list of baked goods and cake sales. Even in its own minutes, the Ladies' Auxiliaryappeared to be servile, with, for example, Katherine Matthew urging the womenin the December 1893 minutes to take direction from her husband in the arrange-ment and cleaning of the society's museum (Ladies' Auxiliary, 1893-1905). I even-tually realized that this response was sexist, and that I was underestimating thevalue of both cake and housekeeping skills. Additional research indicated thatthe tea rooms and bazaars organized by members of the Ladies' Auxiliary fundedthe educational and social activities of the Natural History Society, while provid-ing the public face of tbe institution. Turning to other kinds of records revealedthe more substantial presence of these women. Members of the Ladies' Auxiliarygave insects, textiles, and stuffed mammals to the Museum of the Natural HistorySociety, ensuring that their names would be recorded in the official accession

95

Lianne McTavish

records. They created an alternative archive by inscribing the names of femalemembers on furniture donated to the society, featuring selected women in por-traits meant to adorn the lecture room, and launching the Kate M. MatthewLecture course, in which women gave public talks that were advertised widely andoccasionally reprinted in local newspapers.

In her study of early American art galleries, historian Kathleen D. McCarthyargues that women had a "surprisingly limited role" in such institutions between1830 and 1930, becoming important contributors to museums only later in thetwentieth century (1991, xi). Her claims cannot be extended to the Museum ofthe Natural History Society, where women were involved almost from its incep-tion. Their participation was no doubt encouraged by the museum's emphasis onthe study of natural history, considered an acceptable pursuit for both male andfemale amateur enthusiasts throughout the nineteenth cenUiry (C. Berger 1983,17-18). The inclusiveness of the museum may have fostered female involve-ment, for it embraced a wide range of objects, from mineral specimens to plants,antique jewellery, Asian clothing, Aboriginal baskets, foreign coins, and artisticengravings; yet women were never accepted as full members within the NaturalHistory Society. Analyzing their marginal position produces a familiar story ofwomen's efforts to gain both power and authority within a male-dominatedinstitution. At the same time, the museum itself^particularly its gift economy—allowed women to assert their presence within the Natural History Society bydonating the various specimens they had collected. Historian jordanna Bailkinhas recognized the paradoxical function of the modern museum, arguing thatit acted "both as a compensatory institution for women—a cultural offering forthe denial of political rights^—and as a central force In the creation of femalepolitical identity" (2004, 261). This essay shows that her characterization ofwomen's historical relationship with museums is relevant to both nineteenthand twentieth centuries.

Women in the Natural History Society of New Brunswick

In 1862, 43 men—including business owners, customs officials, and teachers—founded the Natural History Society of New Brunswick in Saint John. Along withthe promotion of useful science, they wanted to create a museum to "illustratethe Natural History of this Province, and so far as possible, of other countries,"as they asserted in an early meeting on 29 January 1862 (NHS 1862-90). By1864, this museum contained 10,000 minerals and fossils, 2,000 marine inverte-brates, 750 insects, 500 plants, and 30 stuffed birds (Botsford 1888, 5). Accordingto members present at that January meeting, the collection and display of these

96

Journal o/Canadian Studies • Revue d'études canadiennes

objects contributed both generally to the dissemination of useful knowledge, andspecifically to the promotion of New Brunswick's natural resources, especiallythe "vast and varied deposits of mineral wealth in which our Province abounds"(NHS 1862-90). This conflation of museums and industrial expansion was com-monplace during the Victorian era, when exhibitions were meant to develop themind and the economy (Mak 1996, 36-42; Hooper-Greenhill 1992, 168; Sheets-Pyenson 1988). Early members of the Natural History Society followed a Baconianapproach by focussing on the inventory and description of nature, believing thatthe observation of a wide range of specimens could educate the average person:looking would lead to a kind of masterful knowing, and would eventually con-tribute to economic progress in the province (McTavish 2006). At the same time,they proclaimed that nature study was an appropriate social pastime. As historianCarl Berger has argued, Canadian natural history groups flourished during thenineteenth and early twentieth centuries because they provided leisure activitiesconsidered to be spiritually and physically beneficial to participants (1983, xiii,10,31-32,45).

In 1881, the mate founders invited women to join as associate members,rhe minutes of 9 May 1881 record that "On motion it was resolved that a classof Associate members be instituted for ladies whose names shall be approved bythe council, who shall be admitted to all the public business of the society uponpayment of one dollar per annum" (NHS 1862-1901). This formal admission ofwomen as associate members occurred during attempts to revive the society, whichhad become dormant in 1874. In July 1880, a number of the key early mem-bers, including George F. Matthew, began contacting previous participants whileattempting to attract new members and raise the public profile of the organization(NHS 1862-1901). For the most part, the first women to gain entry were the wivesand daughters of long-standing male members, but a number of other womeneventually joined, including Miss Belle Nugent, a Saint John teacher whose admis-sion is recorded in the minutes on 1 June 1886 (NHS 1862-1901). The associatemembers were primariiy white, middle-class, adult women of varying ages fromthe Saint John region.

The earliest female associate members of the Natural History Society hadlikely been participating informally since the group's inception, preparing foodfor its social events. In the minutes of 2 January 1865, for example, male admin-istrators thanked anonymous ladies for having provided refreshments at theannual amvfrwz/oiif (NHS 1862-90). According to the archival records, even afterbecoming associate members women continued to perform this role, with theminutes of 28 February 1882 suggesting that "the ladies who assisted in gettingup the conversazione last year be requested to do so again" (NHS 1862-1901).

97

Üanne McTavish

The minutes record that members of the Ladies' Auxiliary also accomplished awider range of other conventionally feminine tasks, mentioning decorationsfor the society's rooms for the various cotiversazioni on 15 January 1884, a com-mittee to purchase a new curtain for the lecture room on 1 March 1892, and apartnership with the female members of the Historical and Loyalist societies toarrange a picnic lunch for the Royal Society of Canada, which held its annualmeeting in Saint John in 1904 (NHS 1862-1901). The minutes indicate that asso-ciate members continually consulted with male administrators when undertak-ing these projects, asking permission to collect and spend money.

The social events organized by the associate members of the Natural HistorySociety were often designed to raise funds. A small admission fee was charged forentry to the conversazioni, but the women also organized suppers and bazaars. On6 November 1900, for example, the Scientific Supper committee of the Ladies'Auxiliary provided $30.00 to purchase a "much needed geological case" for themuseum (Ladies' Auxiliary 1893-1905). Later sales enabled the Ladies' Auxiliaryto donate funds on 2 February 1909 for the acquisition of more elaborate casesand a reflectoscope used to project images during the society's lectures (NHS1890-1911). Similar forms of fundraising were deployed by benevolent womenelsewhere, including nineteenth-century religious women in small-town Ontario,who directed their profits towards the improvement of church interiors (Marks1996, 65-67, 75). According to McCarthy, American women likewise engaged in"non-profit entrepreneurship" in relation to museums and social groups, finding arespectable outlet for their commercial ambitions (1991, 61). The events organizedby the Ladies' Auxiliary of the Natural History Society were indeed commercialventures, but were also decidedly feminine in their emphasis on food, and were inkeeping with the economic vision of the museum promoted by male members.

These successfijl fundraising events improved the public profile of the Natu-ral History Society, while increasing the visibility of the Ladies' Auxiliary withinthe organization. Women gradually began to receive more attention in the officialminutes of the society. During the 1880s, the number of women involved in theLadies' Auxiliary was modest, with, for example, only 41 female associates in 1886(NHS 1886, 39). Women continued to join the society, however, and by 1912there were 359 associate members in contrast to the 142 regular male members(NHS 1912, 481 ). Though the number of women eventually declined, during theearly twentieth century the female members consistently outnumbered the malemembers. On 30 September 1925, there were 263 associate members and 93 reg-ular members (NHS 1924-42). It is difficult to assess exactly how many of thesewomen were actively involved in the Ladies' Auxiliary, but at least some of themwere expanding their participation beyond the preparation of refreshments and

98

Journal «/"Canadian Studies • Revue d'études canadiennes

organization of fundraising events. As a group, the women were able to providea modest salary for the female librarian who kept the doors of the museum opento the public. In the minutes of 4 January 1898, the president stated that theassociate members had in view the "appointment of a lady curator and librarianwho [sic] services should be at the disposal of the Society on Tuesday, Thursday,and Saturday afternoon of each week, when the rooms would he thrown opento the Public" (NHS 1862-90).

Individual women began to be listed as members of committees devoted tothe study of natural history, especially in the groups interested in hotany andornithology. A few women were involved in less traditionally feminine pursuits,notably Caroline Heustis, an entomologist who was already presenting reports onher insect research during the summer of 1881; the society noted on 17 February1882 her provision of a catalogue of local insects (NHS 1862-90). Other womenhad joined the geology committee by the late nineteenth century, a group thathad hitherto been exclusively male, as the minutes record on 19 May 1898 (NHS1862-1901). Women also participated in the field trips, organized so that mem-bers of the society could explore selected natural history sites throughout tbeprovince. On 6 June 1893, male members were concerned to secure appropriatelodging for the ladies attending the summer camp at Lakeville (NHS 1862-1901).The increased role of women was apparently appreciated by male members, wholinked it witb the international recognition of scholarly women. According to theNatural History Society's annual report during the meeting on 15 January 1895,

We second with pleasure our hearty appreciation of the support given tothis society by the ladies. In almost every department of human activitywomen are showing that they are able and capable of taking an advancedplace. In England Miss Raisin and Miss Crane and in the United StatesMiss Rosa Engleman have done scientific work of great merit and wona recognized place in the world of science. Mrs Wm Bowden and MissGrace Murphy have done excellently in geology while Mrs Addy, Miss M.Fairweatber, Miss Eleanor Robinson, Miss Agnes Warner and others havestudied with success our local flora. May this band grow in numbers andincrease In zeal!! (NHS 1862-90)

These men did not wish to extend such praise by granting the women equalstatus within the organization, although the associate members increasinglydemanded more autonomy. From its inception, the Ladies' Auxiliary had beenpositioned as ancillary to the "regular" group, paying an entry fee of $1.00 wbenthe men paid $2.00 for their memberships. At first, the women could not select

99

Líanne McTavish

their own leaders, but on 17 January 1893 the constitution of the Natural His-tory Society was amended to indicate that the associate members "shall havepower to elect a President and Secretary of their own Branch" (NHS 1862-90).The women nevertheless lacked the right to manage their own money, and the2 March 1897 meeting records their request for permission from male adminis-trators to send out bills and collect the yearly dues from female members (NHS1862-1901). On 23 March 1908, the society's constitution was again updated,but continued to position women on the margins of the institution, reaffirmingthat they "shall have a right to take part in and vote at all meetings and gather-ings of the Society, excepting the Annual meeting" (NHS 1901-20). Tbe womenresponded to this continued exclusion from full membership by periodicallyattempting to increase their status. When male members asked the Ladies' Aux-iliary to host various events to raise money in 1925, the women countered bysuggesting that they instead be allowed to become full members, providingfunds with the increased dues they would pay (Ladies' Auxiliary 1916-26). Theidea was promptly rejected. At an earlier meeting, Emma Fiske, a long-time par-ticipant in the Ladies' Auxiliary, had proposed full membership for the women.According to Secretary-Treasurer Harriet B. Holman, Fiske "had hardly finishedreading when a man back of me in the hall jumped to bis feet in great indigna-tion, and said 'When the Women come in, the Men go out.'" The women didnot always capitulate, for when M.R. Rankine, periodically secretary-treasurer oftbe Ladies' Auxiliary, read her annual report to the male administrators of tbeNatural History Society in 1922, she defiantly noted that the women's fundraisingefforts produced "money which we spend as we choose, [and] no exception canbe taken to our reckless generosity, or our business methods, should any criticismoccur to the practical male 'members in full standing'" (Ladies' Auxiliary 1916-26).She implied that male administrators did not approve of tbe purchases made bythe Ladies' Auxiliary, which by then included various decorarions and fiarnishingsfor the rooms of the Natural History Society, as well as a piano. On 6 December1927, the women had declared tbat they formed a "separate organization withinthe society," but they did not receive full status within the Natural History Societyuntil 1943, when the group was virtually defijnct (Udies' Auxiliary 1926-32).

A contradictory view of the members of the Ladies' Auxiliary emerges fromthe written records. When the women recognized male authority, conductedbake sales, or participated in collecting and labelling natural history specimens,they were welcomed by what they sometimes called their "parent organization."When the ladies attempted, however, to become full members or to thwart malesupervision, their position on the margins of the organization was reaffirmed.On the one hand, the archival reports—particularly the minute books kept by

100

Journal w/ Canadian Studies • Revue d'études canadiennes

men—portray the associate members as modest, hardworking, and even servileparticipants in the Natural History Society. On the other hand, in their own min-utes and reports the women sometimes appear to have been impatient, ambitious,and longing to pursue goals not entirely in keeping with the original aims of theNatural History Society, a point that will become clearer below.

Gift Giving as a Gendered Strategy

Despite being denied full entry into the Natural History Society, members ofthe Ladies' Auxiliary found alternative ways to assert their presence. They regu-larly gave gifts to both the museum and the society. In his well-known study,anthropologist Marcel Mauss argues that in several non-Western societies, giftgiving is a complex ritual that helps to constitute social relationships rather thanmerely signify them. In these cultures, participation in such exchanges is obliga-tory, with the initial recipient of a gift required to offer a "return gift" in keep-ing with kinship, legal, economic, religious, and other social structures (2002,11-23). According to historian Simon Knell, the long-standing practice of donat-ing specimens to museums is a similar kind of ritual motivated by the quest foresteem and recognition rather than by selflessness (2000, 116-18, 121). Thesearguments illuminate the donations made to the Natural History Society andits museum by members of the Ladies' Auxiliary during the late nineteenth andearly twentieth centuries. By donating furnishings for the rooms of the NaturalHistory Society, the women insisted on both their material presence in and con-tributions to the organization. By giving gifts to the society's museum, they hadtheir names inscribed in the accession registers and occasionally in the minutesof the society's regular meetings, During this early period of museum building,gifts were never refused and had to be politely acknowledged as well as displayedwithin the exhibition spaces.

The minutes of 16 September 1898 indicate that "the Secretary was requestedto convey the Society's thanks to Miss Warner (the local botanist subsequentlypraised in 1925] for her valuable collection of New Brunswick plants." In 1894,another member of the Ladies' Auxiliary, Mrs. Mary Lawrence, a teacher in SaintJohn, was thanked for her donation of a caribou; considered a "fine specimen"worth about $40.00, it was immediately installed in the society's lecture hall (NHS1862-1901). The accession records show that the women continued to proffer awide range of objects, including practically all of the Aboriginal items displayedin the museum. In 1906, the museum's long time curator, William Macintosh,appealed for the donation of Native goods, noting that the collections did notinclude a single example of beadwork, basketry, or quill work (1908, 61). The

101

Lianne McTavish

women of the Ladies' Auxiliary immediately responded by offering the museumaround 40 objects, including the Aboriginal baskets, clothing, and souvenirsfrom their personal collections (NHS 1889-1912). Their enthusiasm for suchitems reinforces art historian Ruth Phillips's claim that Victorian women valuedNative souvenir objects, particularly those decorated with floral motifs, and per-formed a convenrionally feminine role by arranging them in their homes (1998,188-89). Members of the Ladies' Auxiliary were eager to convey these femininetastes into the Museum of the Natural History Society, reshaping its collecrions byhaving historically denigrated objects both displayed and preserved. While malemembers of the society also donated a range of objects to the museum, womenhad a strong presence in the accession records, matching if not surpassing the giftgiving of men. At the same time, by donating Aboriginal objects the women didmore than compete with men; they also aligned themselves with the male mem-bers in terms of both class and race (Morgan 2(X)1, 494). As middle-class whitewomen, they had the financial means to possess items produced by Aboriginalarrists and craftspeople, and furthermore claimed the right to participate in thecolonial representation of those people within the museum. Members of theLadies' Auxiliary thus paradoxically appropriated Aboriginal culture as theirown and drew attention to the skilled handiwork of anonymous Aboriginal pro-ducers, many of them likely female.

In the nineteenth century as today, the selection and delivery of gifts wasprimarily understood as women's work. Scholars who study the development ofa consumer society in the United States argue that consumption was linked withgift giving to reframe it as a morally acceptable activity. Historian Alice Taylor, forexample, claims that the organizers of the anti-slavery fairs in Boston between1834 and 1858 promoted shopping as a form of political behaviour, asking womenin pariicular to buy for the sake of the slave (2(K)7). Held annually during theChristmas season, abolitionist fairs created the concept of "holiday shopping"while portraying the purchase of material goods as a seltless action performed tobenefit an other. Historian Cecilia Morgan finds that Canadian Christian womenhosted smaller bazaars to raise funds for charity, thereby attracting media attentionto the value of women's work (1996, 203-7). The women of the Natural HistorySociety parricipated in similar kinds of fijndraising events, organizing sales to raisemoney for the society and its museum, causes they considered socially beneficial.In 1906, for instance, the minutes of the Ladies' Auxiliary record on 28 February asuccessful loan exhibition and high tea in Saint John's York Theatre; they chargedan entry fee of 25 cents for the opportunity to see sucii items as Mrs. A.L. Holman'sPeruvian mummy sheet (Ladies' Auxiliary 1906-10). Both the public's consump-tion of the goods produced hy the women and the women's participation in selling

102

journal o/"Canadian Studies • Revue d'études canadiennes

those goods were framed as charitable activities. The women linked the public dis-play of their personal items with generosity rather than egotism. They then madea point of giving the funds they raised as a gift to the Natural History Society.

On 1 May 1906, Gordon Leavitt, the long-time treasurer of the NaturalHistory Society, announced that the entry fees and food sales at the York Theatrehad produced $323.62, which was subsequently donated by the women to thefledgling building fund (NHS 1890-1911). Women's interest in improved lodg-ings was not unusual, for historian Lynne Marks has shown that between 1888and 1896 the Ladies' Mite Society in Thorold, Ontario, for example, raised fundsto help pay the mortgage on the congregation's new Presbyterian church (1996,67); yet in contrast to these women, the Ladies' Auxiliary of the Natural HistorySociety ultimately provided most of the funding for their new museum building.In 1907, a large four-storey brick house on Union Street in Saint John was pur-chased by the Natural History Society for just over $7,000. There was, however, asubstantial mortgage owing on it. The minutes of 2 February 1909 record GeorgeR Matthew's vow to donate his esteemed paleontology collection to the museumonly after this mortgage had been cleared—a method of encouraging the soci-ety to discharge its debts (NHS 1890-1911). In the end, it was a member of theLadies' Auxiliary, Catherine Murdock, who paid off the mortgage, leaving over$4,000 to the Natural History Society in her will of 1909; the society's recordsrecord her bequest on 3 January 1910 (NHS 1890-1911). Her husband, who hadpredeceased her in 1894, had been a founding member of the society with aninterest in meteorology (NHS 1862-96, 229). The annual report of 1910 brieflynoted that with her bequest Mrs. Murdock not only freed the society from debt,but also enabled the acquisition of Dr. Matthew's collection (261).

The members of the Ladies' Auxiliary apparently considered the "return gift"of recognition offered by the male members woefully inadequate. Determined toprovide a fuller acknowledgement of the contributions of their female colleague,on 17 October 1910 the women recorded the purchase of "a beautiful quarteredoak desk" for the rooms of the Natural History Society, fitting it with a brass plaqueinscribed with the words: "In living memory of Catherine Murdock, St. John, NB1910, presented by the ladies of the N.H.S." (Ladies' Auxiliary 1906-10). CatherineMurdock's various donations had already been noted in the official documentsof the society: a fifteenth-century cup and saucer recorded on 1 April 1897, anda nest of trap door spiders offered on 7 December 1905 (NHS 1889-1912). Thedonation of this inscribed lectern (called a desk during the nineteenth century)is perhaps the most blatant example of how members of the Ladies' Auxiliaryemployed the morally acceptable method of gift giving to insist on the importantstatus of women in the Natural History Society.

103

Lianne McTavish

In another gift-giving campaign, members of the Ladies' Auxiliary commis-sioned portraits of female as well as male members to display in the meetingrooms of the Natural History Society. Their interest in portraiture began in 1896,when on 5 May the society acknowledged the women's presentation of a life-sized image of George F. Matthew, honouring his international reputation as ageologist (NHS 1890-1911). On 26 October 1915, the annual report of the Ladies'Auxiliary announced that "In commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of theorganization of the Society, the ladies have secured portraits of all past presidentsof the Society, and of one or two other prominent members, and will presentthem to the Society." They pointedly included women within the category ofprominent members, attaching a hrass name plate to the portrait of Grace Leavitt(NHS 1912-20). The sister of Gordon Leavitt, she had been the secretary-treasurerof the Ladies' Auxiliary for 20 years. On 5 June 1917, the portrait of Mrs. J.V. Ellis,one of the past presidents of the Ladies' Auxiliary, was unveiled in an officialceremony that declared her an esteemed member of the society (NHS 1912-20).A similar strategy had been used much earlier by female artists admitted on anunequal basis to the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris during theeighteenth century By donating a self-portrait to the Royal Academy, Elisabeth-Sophie Chéron ensured her symbolic presence at academic events from whichshe was officially excluded (McTavish 1996). The women of the Ladies' Auxil-iary, perhaps unknowingly, employed a similar technique by commissioningportraits of female members who would be visible during the male-only annualmeetings of the Natural History Society and represented as part of the officialhistory of the institution. At the same time, by supplying portraits the mem-bers of the Ladies' Auxiiiary continued their feminine practice of decorating therooms of the society, proffering gifts that could hardly be refused. The womenthus laid claim to space in the society, employing a strategy used by other nine-teenth-century benevolent women, including those who domesticated sacredplaces by purchasing altar cloths and carpets for churches (Marks 1996, 68-69).

The women of the Natural History Society also participated in activities thatwere less traditionally feminine by giving lectures to the public. Lectures hadbeen an important part of the society from its inception. Members met everyTuesday evening to hear a lecture on hotany, geology, or zoology, among othertopics, usually given by a prominent male member of the group, such as GeorgeF. Matthew, but also by invited male guests. In 1863, a paper on microscopicalgae, by Professor Loring Woart Bailey of the University of New Brunswick inFrederieton, for example, was read to the assembled group of men and women(NHS n.d.). Records of attendance kept between 1913 and 1920 indicate thatbetween 50 and 100 listeners were typically present at these lectures (NHS 1912-20).

104

Journal »/Canadian Studies • Revue d'études canadiennes

The only reference to a female speaker appears in the minutes of 6 March 1894,describing a Saint John Daily Sun article that would appear the next day. A briefcolumn notes that a member of tbe Ladies' Auxiliary, Miss Eleanor Robinson, hadpresented at tbe regular meeting her article on Dr. Silas T. Rand, a nineteenth-century missionary who had worked among the Micmac and documented theirlanguage. The newspaper report—likely written by a member of the NaturalHistory Society as a form of promotion, a common practice at the time—notesthat Rohinson began her talk with an "entertaining account of [Rand's] earlylife" and ended it by pronouncing some Micmac words (NHS 1890-1911).

In 1899, tbe members of the Ladies' Auxiliary initiated tbeir own lecture ser-ies on Thursday afternoons, eventually naming it tbe Kate M. Matthew Lecturecourse, after tbeir president. In this series, female lecturers spoke on a range oftopics, including birds, fossils, and specific objects in the museum's collections.Many women discussed their recent travels, describing the architecture and cul-ture of Egypt, France, Spain, or Japan. On 7 February 1908, for example, Mrs.F.A. Foster's talk, entitled "My Impressions of Paris," covered cathedrals and artgalleries, while advising her listeners to visit Paris in May and stay for a monthwith a French family (Ladies' Auxiliary 1907-09). On 1 November 1927, thesociety noted that Miss Christine Matthew (Katherine and George E Matthew'sniece) gave a talk on dinosaurs, illustrating her presentation with slides as wellas a specimen of fossilized dinosaur skin recently presented to the AmericanMuseum of Natural History in New York City. It was likely supplied by WilliamDiller Matthew, Katherine and George's son, who was then a palaeontologist atthe American Museum (NHS 1924-42; Colbert 1992). In any case, the NaturalHistory Society and its collections enabled tbe women to speak publicly, poten-tially providing them "witb a back door into tbe public sphere," a phrase usedby bistorian E.A. Heaman to describe how Canadian women benefifted fromparticiparing in exhibitions during the nineteenth century (1999, 259).

The women of the Ladies' Auxiliary positioned these public lectures withintbe framework of gift giving, charging entry fees that were then donated to thesociety. The afternoon talks were well attended, according to the minutes of theLadies' Auxiliary, and about 19 were given each winter, with the last presenta-tion of each month aimed at children. In October of 1915, President KatherineMatthew addressed the women, arguing that

I need not tell you how mucb pleasure it gives me to meet you all onceagain at this opening of another winter's work for the Natural HistorySociety; or rather, may I not say, to do our part in the higher education ofthe community in which we live. We all realize, I am sure, that our educa-tion—the drawing out and developing of our higher powers, mental andspiritual—is little more tban begun when we leave school. Tbe school or

105

Lianne McTavish

college but prepares us for the discipline of life, and our object as a brancbof the Natural History Society is surely first to develop our own powersand to help others in the formation of what has been called an "all round"character, the character which will be ours for time and for eternity. We allbelieve that the lecture courses we have given here each winter for sixteenyears have been a help to this end. (NHS 1912-20)

Katherine Matthew portrayed the lecture series as a gift to the public, as well as aneducational offering in keeping with the primary mandate of the Natural HistorySociety, These lectures were clearly also social occasions, involving food consump-tion, musical interludes, and ethnically relevant costumes. The president and theother members of the Ladies' Auxiliary implied that socializing, eating, and listen-ing to lectures were complementary educational activities.

The lecture series provided members of the Ladies' Auxiliary with the chanceto pursue self-promotion, both within and outside of the organization. The authorsand titles of the lectures were listed in the annual report provided by the ladies,which in 190.3 began to be printed along with other reports in the Bulletin of theNatural History Society of New Brunswick. This journal, published on a nearly annualbasis between 1882 and 1914, was disseminated to all members of the society, aswell as to many international organizations. Such documentation of the women'swork might have compensated at least partially for the utter lack of writing bywomen in the Bulletin. Although male administrators had recommended on 6March that Eleanor Robinson's 1894 lecture on Dr. Silas T Rand be publishedin the forthcoming Bulletin, it never appeared (NHS 1890-1911). Several of thelectures given by women were instead either summarized briefly or published infull in one of the Saint John newspapers, particularly between 1904 and 1914. In1907, Katherine Matthew's presidential address was reprinted in the Saint JohnGlobe (4), while a few weeks later an article in the Saint John Daily Telegraph notedthat a substantial crowd that included men had listened intently to a lecture about"Indians" given by Mrs. H. Roberts (1907, 8). The Ladies' Auxiliary may have paidfor this kind of promotion, for later records show regular expenditures on news-paper advertising (Ladies' Auxiliary 1917-26). Despite being framed in terms ofbenevolence, these talks potentially transgressed the hierarchical structure of theNatural History Society by positioning women as authority figures and making apublic display of female autonomy.

While giving public lectures can be considered a political act, the membersof the Ladies' Auxiliary also involved themselves directly in political work aimedat improving the lives of women. The Ladies' Auxiliary was affiliated with theSaint John chapter of the Women's Council, an international organization that

106

Journal o/"Canadian Studies • Revue d'études canadiennes

promoted the protection of women workers and supported the suffrage movement(Strong-Boag 1975, 22-3.3). Membership in the Women's Council was not withoutcontroversy, however, for on 7 December 1897 the women voted on whether ornot to remain part of the council, with some arguing that such work was impor-tant, and others that it was foreign to the goals of the Natural History Society. Thevote was 4 to 8 in favour of withdrawing, and on 14 December a wider vote wascalled for, the results of which are unknown (Ladies' Auxiliary 1892-1905); yet themembers of the Ladies' Auxiliary continued to pay dues to the Women's Councilwell into the twentieth century. In this capacity, the New Brunswick womenofficially endorsed the council's activities, reporting on 30 September 1920 that"such measures, which are of interest to women, as the 'Minimum Wage Act,'and 'Mother's Pensions,' were discussed and heartily endorsed" (Ladies' Auxiliary1915-31). Sometimes the status of women in countries other than Canada wasaddressed in the lectures the women gave. In 1904, for example, Mrs. E.A. Smith,claimed that during a visit to Switzeriand slie had seen young and old womenalike carrying heavy packages on their backs, a practice that cleariy appalled her(5íií/íf John Daily Telegraph 1904, 2). The Saint John Globe reported in 1923 thatMiss M.E. Travis, of Hampton, had visited her sister, the missionary Dr. CatherineTravis, in Honan province in China, donating some valuable gifts to the NaturalHistory Society upon her return. Of particular note was a lady's shoe which "by itstiny size gives some idea of the torture the women endure in conforming to theideals of beauty of their country."

It was not unusual for benevolent women to take a wide interest in socialreform both locally and Internationally during the nineteenth century. HistorianCecilia Morgan argues that Ontario women who supported tiie creation of localmuseums were also involved in a range of other voluntary work, joining tem-perance groups, missionary societies, and the suffrage movement (2004, 241).nmma Fiske, the outspoken woman who demanded full membership during ameering of the Natural History Society, as noted above, certainly fits this descrip-tion. In addition to being a long-standing member of the Ladies' Auxiliary, shewas involved in the Saint John Art Club, the Ladies' Auxiliary of the TemperanceUnion, the Red Cross Society, and the Women's Enfranchisement Association.Among other things, Fiske both lobbied government about and spoke publicly infavour of compulsory public schooling and the need for a factory act to regulatechild labour and industrial working conditions in New Brunswick. According tohistorian Janice Cook, Fiske was most devoted, however, to expanding women'spolitical rights, serving as the president of the Women's Enfranchisement Asso-ciation from 1898 until her death in 1914. Like other participants in this suf-frage group, Fiske affirmed that a "lack of political power was the source of socialinequality and social injustice" (Cook 1990, 82).

107

Lianne McTavish

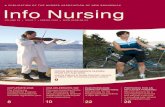

Fig. 1 Iiiifíioi View ol Hit- Oriental Exhibition, Natural History Museum, Saint ¡ohn. New

Brunswick, January 1924. Courtesy of the New Brunswick Museum.

Although few other members of the Ladies' Auxiliary of the Natural HistorySociety were as politically active as Fiske, some of their events highlighted theachievements of well-educated women. In 1924, the Ladies' Auxiliary held a suc-cessful Oriental Exhibition in the rooms of the Museum of the Natural HistorySociety, drawing on the recent gifts of Chinese porcelain and Japanese art andtextiles from, among others. Dr. Catherine Travis and Loretta Shaw. Like Dr.Travis, Shaw was a missionary, working in Japan from 1905 to 1935 as a pas-sionate advocate of women's emancipation, in addition to supporting suffragefor Canadian women (Quinn 2007). According to a newspaper report encour-aging public attendance at the exhibition, "the upper floor of the museum [was]converted into an Oriental bazaar, and tea [was] served by ladies in Orientalcostumes" (NHS 1921-1934, 3). A rare surviving photograph of the interior ofthe early Museum of the Natural History Society portrays this transformation,showing a room adorned with decorative wall hangings, and filled with Asiansculptures, vases, figurines, and at least one umbrella (ñg. 1).

The Oriental Exhibition is a particularly poignant example of the contribu-tions made by women to an early Canadian museum, for it featured female gift

108

Journal o^ '̂Canadian Studies • Revue d'études canadiennes

Fig. 2 Unidentified Women in Asian Costume, January 1924.

See www.unbf.cti/wornenandmuseum/bauxillary.htm. Courtesy of the New Brunswick

Museum.

giving and food preparation, while enabling women to reshape the museumdisplays and play the role of welcoming hostess. In this instance, the sale of foodtook place directly inside the museum, positioning it as a legitimate activity cru-cial to tbe continuing existence of the institution. At the same time, the women'sinterest in tbe exotic "Orient" could have reaffirmed rather than challenged thegendered stereotypes of the day. The white middle-class members of the Ladies'Auxiliary found pleasure in masquerading as racial others as they "played" at beingAsian. The theatrical nature of their activities recalls historian M. Alison Kibler'saccount of the ways in which white women performed black face in Americanvaudeville acts during the early twentieth century. According to her, the whiteprivilege of these actresses gave them the freedom to mimic blackness, a pursuitthat not only provided them with a certain upward mobility but also allowedthem to move towards more masculine roles (Kibler 1999, 113, 129). In keeping

109

Lianne McTavish

with their donation of Aboriginal items, tbe Asian costumes of members of theLadies' Auxiliary may have reinforced hierarchies of race and class.

Another photograph shows three unnamed women in Asian costume stand-ing within the exhibition space described above (fig. 2). This image epitomizesthe complex relarionship of New Brunswick women with museums, showing themembers of the Ladies' Auxiliary as simultaneously significant and subordinate.On the one hand, the elegant women position themselves as a crucial part ofthe museum setting; they are integral to its appearance and closely associatedwith the objects on display. The photograph attests to the authority and materialpresence of the associate members of the Natural History Society. On the otherhand, the women appear simply to be objects on display, akin to the wall ban-ners, vases, and carpets that surround them. In her analysis of nineteenth-centuryexhibitions In Canada, Heaman elaborates on the conflicted position of womenwho were supposed to be hoth modestly retiring and easily available to the malegaze (1999, 262-63). Tbe women in Asian costume embody this contradiction, fordespite the potentially assertive nature of their identity in this photograph, tbeyare also shown to be passive, unspeaking, and servile. The photograph provesthat the members of the Ladies' Auxiliary succeeded in their efforts to enter theofficial discourse of the museum. It is, after all, an important archival record of thewomen's activity. The women in this photograph nevertheless remain unidenti-fied, indicating that they are still seen more as ornaments than as individuals.

Conclusions

The Museum of the Natural History Society of New Brun.swick did not foster thekind of women's culture that Brian Young has discovered at the McCord Museum.Despite supplying substantial funds and objects to the museum, members of theLadies' Auxiliary never acquired the freedom to arrange the permanent collec-tions or even to become full-fledged members of the group wbile it was active. Tbewomen found ways, however, in whicb to represent themselves in the society'smuseum, meeting rooms, and official records, as well as in the public eye. Theirprimary strategy was gift giving, a conventionally feminine activity that seemedselfless rather tban aggressive. Tbe members of tbe Ladies' Auxiliary made littledistinction between tbe work of baking cakes, decorating rooms, giving lectures,mounting temporary exhibitions, and endorsing women's rights, undertakingthem all in relation to tbe museum. Considering the range of their activities pro-vides a fuller picture of an early museum in Canada, showing that it promotedmore than the acquisition and display of objects. It was also a site for the produc-tion of gendered identities, as well as other social and political activities.

110

Journal «/"Canadian Studies • Revue d'études canadiennes

Studying these women furthermore reveals that the nineteenth-centurymuseum was both founded on and expanded by the entertainments, promotionalbazaars, and high teas they organized. When current scholars regret that the con-temporary museum has increasingly become a site of entertainment rather thanbeing exclusively devoted to education, they overlook the long and important his-tory of social events and special fundraising exhibitions within the museum. Suchcritics unwittingly echo the male administrators of the museum of the NaturalHistory Society by reinforcing a gendered hierarchy that dismisses as secondarythe management and housekeeping skills traditionally performed by women.They may unconsciously rely on gendered assumptions, rejecting consumption asa feminine, bodily activity. Of course, in today's museums, it is often large corpora-tions rather than charitable women who benefit from commercial sales; yet criticsof contemporary museums typically make little distinction between the recipientof the funds raised—which may indeed be contrary to the public's interest—andthe commercial activities that produce those funds. Considering the historicalcontributions made by women to early museums can forestall blanket critiquesof commercial activities within museums, forcing critics to be more precise aboutthe types of commodification they oppose.

In 1996, the exhibition spaces of the New Brunswick Museum were relocatedto a downtown shopping centre, raising the spectre of commercialization. In con-trast to the free-standing neoclassical building constructed during the early 1930s,visitors now enter the Market Square centre in Saint John, walking by varioustravel and clothing stores before they arrive at a food court. There, the three-sto-rey painted façade of the New Brunswick Museum looms next to a Tim Horton'sconcession stand. Richard Oland, then president of the museum, was anxiousthat this location not be linked with a loss of heritage. He claimed that the boardof directors decided to "make the new museum look like the old one from the out-side," by having representations of sandstone blocks, pillars, and cornices paintedon the new façade inside the shopping mall. According to him, this façade would"remind visitors that this new facility is part of a museum tradition reaching allthe way back to 1842" (Saint fohn Telegraph Journal 1996).

In some ways, Oland's fears were well founded, for the relocation of the NewBrunswick Museum is keeping with what cultural theorist Alan Bryman calls thededifferentiation of consumption, when cultural practices such as shopping, view-ing exhibitions, and eating become indistinguishable (2002, 52-59). Most visibleat Disney theme parks and Las Vegas casinos, this relatively recent marketing trendwas adopted to a lesser degree in Saint John both to revitalize the harbourfrontarea, and to attract more visitors to the underfunded museum, particularly tour-ists arriving on cruise ships. All the same, developers may have overlooked the

m

Lianne McTavish

historical continuities promoted by the relocation, for as my discussion of theLadies' Auxiliary indicates, engaging in shopping and eating in close relation tomuseum exhibits is nothing new. In some ways, the relocation of the exhibirionspaces of the New Brunswick Museum marks a return to tradition, especially if thecontributions of the associate members of the Natural History Society are valuedrather than forgotten.

The crucial difference signalled by this relocation involves the perceived eco-nomic role of the museum. In the past the Museum of the Natural History Societywas designed to promote the industrial development of the province by increas-ing the public's knowledge of natural history. Today, the New Brunswick Museumis seen, at least by some, as a tool of urban development meant to enhance tour-ism. Commercialization has not been suddenly introduced into the latest ver-sion of the New Brunswick Museum; instead, the primary audience and economicresults expected from the institution have been reconceived. As this exampleshows, acknowledging women's contributions to the early museum does morethan simply add detail to existing museum narratives. Taking women seriouslycan shed light on a range of issues, including the shifting historical definition ofmuseums.

Notes

The author acknowledges the helpful comments provided by the three anonymous ref-erees. The author would also like to thank her research assistants, Joshua Dickison andShawna Quinn, as well as the helpful staff at the New Brunswick Museum. Funding for thisessay was provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Fora virtual exhibition featuring women's contributions to the New Bnmswick Museum andits precursors, see Pro,^ress and Pennanence: Women and the New Brun.swick Museum, 1880-1980, created by Shawna Quinn and Lianne McTavish, at www.unbf.ca/womenandmuseum.

References

Bailkln,Jordanna. 2004. "Picturing Feminism, Selling Liberalism: The Case of the DisappearingHolbein." In Museum Studies: An Anthology of Contexts, ed. Bettina Messia Carbonell,260-72. Oxford: Blackwell.

Bal, Mieke. 1996. Double Exposures: Tlie Subject of Cultural Analysis. New York: Routledge.Bennett, Tony. 1995. The Birth of the Museum: History, Tlieory, Politics. New York: Routledge.Berger, Carl. 1983. Science, God. and Nature in Victorian Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto

Press.

112

Journal o^ Canadian Studies • Revue d'études canadiennes

Berger, Maurice. 2004. "The 'Corporate' Museum." Museums ofTomorrow: A Virtual Discussion,ed. M. Berger, 47-80. New Yoric: Distributed Art Publishers.

Botsford, Le Baron. 1888. "Annual Address." Bulletin of the Natural History Society of NewBrunswick 7: 3-11.

Bourdieu, Pierre, and Alain Darbel. 1969. L'Amour de l'art: Les Musées européens et leur public.

Paris: Minuit.Brooks-Marsden, Lesiie. 2006. "To Study, to Control, and to Love: Women Scientists in

American Natural History Institutions, 1880-1950." PiiD diss.. University of California,Davis.

Bryman, Aian. 2002. "The Disneyization of Society." In McDonaldization: The Reader, ed.

George Ritzer, 52-59. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge.Carrier, David. 2006. Museum Skepticism: A History ofthe Display of Art in Public Galleries.

Durham: Duke University Press.Coiberf, Edwin Harris. 1992. William Diller Matthew, Paleontologist: The Splendid Drama

Observed. New York: Columbia University Press.Cook, Janice Mary. 1994. "Child Labour in Saint John, New Brunswick and the Campaign

for Factory Legislation, 1880-190S." MA thesis. University of New Brunswick.Coombes, Annie. 1998. "Museums and the Formation of National Identities." Oxford Art

Journal 11: 57-68.Duncan, Carol. 1993. Aesthetics and Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

. 1995. Civilizing Rihials: Inside Public Art Museums. London: Routledge.Fernandez-Sacco, Eiien. 1998. "Spectacular Masculinities: The Museums of Peale, Baker

and Bowen in the Early Republic." PhD diss.. University of California, Los Angeles.Heaman, E.A. 1999. The Inglorious Arts of Peace: Exhibitions in Canadian Suciet)- during the

Nineteenth Century. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.Holman, Harriet B. Fonds. CB DOC. ANBM.

Hooper-Greenhill, Eilean. 1992. Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge. New York: Roufledge.Hyde, S. 1997. Exhibiting Gender. Manchester: Manchester University Press.Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Í997. Cultural Leadership in America: Art Matronage and

Patronage. Boston: Trustees of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.Kaplan, Flora S. 1994. Museums and the Making of "Ourselves": The Role of Objects in National

Identity. London: Leicester University Press.Karp, Ivan, and Steven D. Lavine, eds. 1991. Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of

Museum Display. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.Kibler, M. Alison. 1999. Rank Ladies: Gender and Cultural Hierarchy in American Vaudeville.

Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.KnelL Simon J. 2000. The Culture of English Geology, ¡81S-I8S1: A Science Revealed through

Its Collecting. AJdershot: Ashgate.Ladies' Auxiliary of the Natural History Society of New Brunswick. 1893-1905. Minutes

of the Ladies' Auxiliary. S128A, F114. NHS fonds. Arcbives of the New BrunswickMuseum [ANBM], Saint John, NB.

. 1906-10. Minutes of fbe ladies' Auxiliary. S128A, F115. NHS fonds. ANBM.

. 1907-19Ü9. Scrapbook of the Ladies' Auxiliary. S128A, Fl 13. NHS fonds. ANBM.

113

Lianne McTavish

-. 1915-31. Various Reports and Speeches of the Ladies' Auxiliary. S128A, F105. NHSfonds. ANBM.

. 1916-26. Treasurer's Reports of the Ladies' Auxiliary. S128A, F104. NHS fonds,

ANBM.-. 1917-69. Receipt Book of the Ladies' Auxiliary. S128A, F108. NHS fonds. ANBM.. 1926-32. Minutes of the Ladies' Auxiliary. S128A, V\ 16. NHS fonds. ANBM.

Luke, Timothy. 2002. Museum Politics: Power Plays at the Exhibition. Minneapolis: Universityof Minnesota Press.

Macintosh, William. 1908. "Curator's Report." Bulletin of the Natural History Society of NewBnmswick 26; 58-62.

Mak, Eileen Diana. 1996. "Patterns of Change, Sources of Influence: An Historical Study

of the Canadian Museum and the Middle Class, 1850-1950." PhD diss.. University ofBritish Columbia.

Marks, Lyn ne. 1996. Revivals and Roller Rinks: Religion, Leisure, and Identity In Late Nineteenth-Century Small-Town Ontario. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Mauss, Marcel. 2002. The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange In Archaic Societies. Trans.W.D. Halls. New York: Routledge.

McCarthy, Kathleen D. 1991. Women's Culture: American Philanthropy and Art, 1830-1930.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Mclsaat, Peter Matthew, 1996. "Open to the Puhlic: The Creation of the Museum and the

Construction of Gender in Nineteenth-Century German Literature and Culture." PhDdiss.. Harvard University.

McTavish, Lianne. 1996. "Complicating Categories: Women, Gender and Sexuality in

Seventeenth-Century French Visual Culture." PhD diss.. University of Rochester.. 2006. "Learning to See in New Brunswick, 1862-1929." Canadian Historical Review'87(4): 553-81.

McTavish, Lianne, and Joshua Dickison. 2007. "William Macintosh, Natural History and the

Professionalization of the New Bmnswick Museum, 1898-1940," Acadiensis: foumal ofthe History of the Atlantic Region 36 (2): 72-90.

Miller, Randall K 2003. "George Frederic Matthew's Contribution to Precambrian Paleobiology."

Geoscience Canada 30 (1): 1-8.. 2004. "Matthew, George Frederic." Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online. Toronto

and Laval: University of Toronto/Université de Laval, and library and Archives Canada,wvm>.biographi.ca.

Morgan, Cecilia. 1996. Public Men and Virtuous Women: Tlie Gendered Languages of Religion

and Politics in Upper Canada, ¡791-1850. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.. 200L "History, Nation, and Empire: Gender and-Southern Ontario Historical Societies,1890-1920S," Canadian Historical Review 82 (3): 491-528.

. 2004. "Gender, Commemoration, and the Creation of Public Spheres: Ontario, 1890s-

1960s." In Les idées en movetnent: perspectives en histoire intellectuelle et culturelle du Canada,ed. Damien-Claude Bélanger, Sophie Coupai, and Michel Ducharme, 225-46. Saint-Nicolas, PQ : Les Presses de l'Université Laval.

114

journal ttf Canadian Studies • Revue d'études canadiennes

Natural History Society of New Brunswick, n.d. Members' Original Papers. S128, F84. NHSfonds. Archives of the New Brunswick Museum [ANBM], Saint John, NB.

. 1862-90. General Minutes of the Natural History Society. S127, F40. NHS fonds.

ANBM.. 1862-96. Scrapbook of the NHS. S129,1-212. NHS fonds. ANBM.. 1862-1901. Minutes of the Council of the NHS. S127, F37. NHS fonds. ANBM.. 1886. "Annual Report of the Council." Bulletin of the Natural History Society of NewBnir]swick 5: 39-42.. 1889-1912. Record Book of Artifacts Donated to the NHS. S128A, F134. NHS fonds.ANBM.

. 1890-1911. General Minutes of the NHS. S127, F41. NHS fonds. ANBM.-. 1901-20. Minutes of the Council of the NHS. S127, F:Î8. NHS fonds. ANBM.. 1910. "Annual Report of the Council." Bulletin of tbe Natural History Society of NewBninswick 2fi: 261-75.. 1912. "Annual Report of the Council." Bulletin of the Natural History Society of New

Brunswick 30: 481-93.. 1912-1920. Gênerai Minutes of the NHS. S127, F42. NHS fonds. ANBM.. 1921-34. Scrapbook of the NHS, Newspaper Clippings. S128A, F124. NHS fonds.ANBM.

. 1924-42. Minutes of the Council of the NHS. S127, F39. NHS fonds. ANBM.NHS. See Natural History Society.I'hiiiips, Ruth. 1998. Trading Identities: Tlie Souvenir in Native North American Art from the

Northeast, Í7Í)0-7900. Seattle: University of Washington Press.Porter, Gaby. 2004. "Seeing through Solidity: A Feminist Perspective on Museums." In

Museum Studies: An Anthology of Contexts, ed. Bettina Messia Carbonell, 104-16. Oxford:Black weil.

Quinn, Shawna. 2007. "Loretta Shaw." Progress and Permanence: Women and the New BrunswickMuseum, 1880-1980. University of New Brunswick,www.unbf ca/womenandmuseitm/bshaw.htm.

Quinn, Shawna, and Lianne McTavish. 2006. Progress and Permanence: Women and the NewBrunswick Museum, 1880-1980. University of New Brunswick,www.unhfca/womenandmuseutn/bshaw.htm.

Saint fobn Daily Telegraph. 1904. "A Delightful Lecture." 25 March, 2.

. 1907. "The Indians of Acadia." 31 October, 8.Saint lohn Globe. 1907. "President's Address Delivered at Annual Meeting." 14 October, 4.

. 1923. "Chinese Finery is Given N.H.S." 8 November.5ííííií John Telegraph Joumal. 1996. "From 'Diamond in the Rough' to Uptown Jewei." 24

April.Sheets-I*yenson, Susan. 1988. Cathedrals of Science: Tlie Development of Colonial Natural History

Museums during tbe Late Nineteenth Century. Kingston, ON: McGill-Queen's University

Press.

115

Lianne McTavish

Strong-Boag, Veronica. 1975, "The Roots of Modern Canadian Feminism: The NationalCouncil of Women, 1893-1929." Canada 3 (2): 22-33.

Taylor, Alice. 2007. "Trading in Abolitionism: The Commercial, Material and Social World of

the Boston Antislavery Fair, 1834-1858." PhD diss.. University of Western Ontario.Taylor, Kendall, 1994. "Pioneering Efforts of Early Museum Workers." In Gender Perspectives:

Essays on Women in Museums, ed. Jane R. Glaser and Artemis A. Zenetou, 11-27.Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Yablonski, Janice B, 1992. Museum Women: A Century' of Women's Employment in Art Museums.

New York: Columbia University.Young, Brian. 2000. The Making and Unmaking of a University Museum: TlieMcCord, 1921-1996.

Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press.

116