sounding the teaching II - Academy of Singapore Teachers

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of sounding the teaching II - Academy of Singapore Teachers

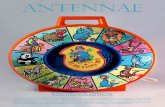

soundingthe teaching II

SUPPORTING AND EVIDENCINGMUSIC LEARNING

A PUBLICATION BY THE SINGAPORE TEACHERS’ ACADEMY FOR THE ARTS (STAR)

We would like to express our appreciation to:

Dr Leong Wei Shin, National Institute of Education, for supporting and providing advice

to the Networked Learning Community.

Principal, Staff and students of: Ang Mo Kio Primary, Canberra Primary School,

Catholic High School, Guangyang Primary School, Maha Bodhi School,

Ngee Ann Primary School, Woodgrove Secondary School, Yuhua Secondary School

ISBN: 978-981-11-6499-6Copyright @2018 by Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRtsAll parts of this publication are protected by copyright. No part of it may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts.

CONTENTS

PRELUDE

EXPOSITION

SUPPORTINGSELF-DIRECTED LEARNING

FOREWORD

06 07INTRODUCTION

16

44

37Supporting Students’ Sense of Relatedness, Competence and Autonomy Chan Hui Juan, CelineMaha Bodhi School

Empowering Students through Negotiating and Understanding Performance BenchmarksSharon Ng Wai YeeGuangyang Primary School

Facilitating Student-Student Interactions with Student Self-Assessment StrategiesKatherine FaroekAng Mo Kio Primary School

EXPOSITION

CHECKING FOR UNDERSTANDINGAND PROVIDING FEEDBACK

SETTING MEANINGFUL ASSIGNMENTS

56

92

120

73

104

Comparing Students’ Evaluation and Teacher’s Evaluation of Group PerformancesTan Keng HongCanberra Primary School

Motivating P6Students through Differentiated TasksEng Yan Chen AlvynNgee Ann Primary School

Facilitating aSong-Writing TaskLiu Jia Yuen ClaireCatholic High School (Secondary)

Improving Student-Student Feedback Using Socratic Questioning, Accountable Talk, and Co-construction of RubricsLim Hui Wen JwenWoodgrove Secondary School

Harnessing E-Portfolio and E-Platform for StudentSelf-AssessmentLee Yue ZhiYuhua Secondary School

CODA136 139REFFLECTIONS REFERENCES

6

by Rebecca Chew, Academy Principal, STAR

FOREWORD

Teachers go beyond the ordinary and make meaning of their own teaching practices to further encourage their young students. The constant need for sense-making and connecting the dots in today’s complex global world inspire teachers to reflect and reframe their own daily teaching practices. The choices we make in pedagogy become important to making relevant music content and knowledge. These choices in the teaching practice create opportunities to impact teaching and learning, and support student learning.

Sounding the Teaching II documents meaningful teaching practices in the context of our music lessons, guided by the Singapore Teaching Practice (STP), and

makes more explicit how joyful teachingand learning can be for our teacherleadership journeys.

We celebrate with all those who have thoughtfully designed these awesome student-centred projects and collaborated to make this publication possible. We hope more music teachers will be inspired in their own teacher leadership journeys, as this second volume serves as an impetus and catalyst to spark more conversations. It will help us think more creatively and critically as we go about designing the lessons that impact and influence the student learners who will create tomorrow.

7

by Chua Siew Ling, Master Teacher (Music)

INTRODUCTION

Extending from the investigations in the first issue of Sounding the Teaching, where we examined learning from the lens of the learner, Sounding the Teaching II examines what supporting and evidencing student learning means. This publication documents the critical inquiry projects of eight teacher-leaders from the Critical Inquiry Networked Learning Community (CI NLC) who embarked on this journey with us. The journey began with an exploration of assessment principles and practices, and a music study trip to the International Symposium on Assessment in Music Education (ISAME) conference in Birmingham, UK. The teachers pursued an idea inspired by the trip and conducted their respective inquiry projects to further their understanding of assessment in supporting student learning in the context of their own music classrooms. Upon their return, they also presented their projects at a mini-symposium held in October 2017.

Supporting and evidencing student learning requires us to be acutely aware of our students’ needs, their psychological environment, their social environment, their abilities, their interests and their learning

styles. As we teach, we are continually trying to understand whether our students are learning, possibly every minute of our lessons. We are learning about our students as individuals through our conversations and interactions with them. We are learning about our students when we engage in music-making with them. We are often looking out for evidences of student learning, from what they say, the way they speak, the way they make music and what they have written down. These evidences help us review our teaching and assessment strategies, so that we can bring about greater learning in our students.

As our students learn, they are continually evaluating themselves, their peers and their teachers. They consider whether they understand the instructions, the concepts and the requirements of the task. They consider where they stand in relation to their peers. These evidences also inform them whether they wish to continue to be interested in learning, whether they should continue to challenge themselves, or whether they should just give up. Our interactions with and feedback to our students can impact them in ways that we might never know.

8

The diverse practices and issues investigated in this publication reflect the plethora of perspectives and strategies about supporting and evidencing students’ music learning. The articles have been organised according to the teaching processes in the Pedagogical Practices of the Singapore Teaching Practice. In each of these processes, some questions that have intrigued members of the CI NLC are listed below. They help guide us as we reflect on our practices.

Supporting self-directed learning

• What activities and tasks can support self-directed learning? How can they engender a growth mindset in our students?

• How can activities and tasks be delivered to better support students’ psychological needs and hence empower students to be self-directed?

• How do student interactions support their own learning?

• What self-assessment strategies do students naturally create for themselves? How can teachers help them develop more self-assessment strategies?

• How can students be empowered through enhancing their understanding of performance benchmarks?

Checking for understanding andproviding feedback

• What activities and tasks and facilitation strategies help check students’ understanding?

• How do students’ evaluation of their own work compare with teachers’ evaluation of their work? Is there a common understanding of the assessment criteria and rubrics?

• What facilitation strategies improve the quality of student-student feedback?

• How do students respond to different feedback strategies such as Socratic questioning and Accountable Talk?

Setting meaningful assignments

• What types of assignments and tasks influence student motivation? How do they impact student motivation?

• How can assignments be fair and cater to different student profiles?

• How can different tools such as online platforms be harnessed to facilitate students’ self-assessment and improve their performance?

• How are the assignments experienced by students? • What contexts influence the design of

meaningful assignments? How do the contexts impact the reception of

these tasks?

9

In seeking understanding to the questions above, various inquiry projects have been conducted by members of the networked learning community. In reading these findings, one might notice that supporting student learning is about understanding the symbiotic relationship between teaching and assessing. As we consider how we could be more student-centric and teach in ways that empower the student voice and grow student identities, we also consider how we could assess in ways that support what we wish to achieve in our students.

In the spirit of inquiry, a range of methodologies has been explored in this collection, some of which might even be deemed unusual and thought-provoking. For instance, the opening number takes on a narrative approach, as the author describes her journey in supporting her students’ sense of relatedness, competence and autonomy in her music lessons. Relatedness, competence and autonomy are three psychological needs postulated in the Self-Determination Theory by Deci and Ryan, which have often been investigated using quantitative and more positivistic approaches. The analysis of data and reflection of her observations in this study, however, use a narrative approach instead and are told through a story. The intent of the narrative is to paint a more vivid picture of the actual classroom practices and experiences to provide a more nuanced understanding.

The other studies in this collection explore a range of analytical techniques such as discourse analysis (interpretation of what the conversations reveal), content analysis (interpretation of content through the coding process) and statistical analysis (interpretation of quantitative data). They take on a paradigm and an understanding that all of us wear different lenses as we examine data due to our own prior experiences. Hence, our observations, quantitative or qualitative, cannot be completely objective. Therefore, these inquiry approaches aim to explore and unleash different perspectives and subjective possibilities. And hence, more traditional, positivist approaches and the use of control groups are absent from these studies. Instead, the approaches explored in this publication illustrate myriad ways of metacognitive thinking, ways in which we could collect data and analyse them to sound out our own teaching practices. We hope that Sounding the Teaching II will inspire you to carry out your own inquiry of your classroom practices, and to see music teaching in a new light.

Self-directed learning is about initiating personally challenging activities and developing the knowledge and skills to overcome the challenges successfully (Gibbons, 2002). There are different kinds of self-directed learning, as well as many ways to facilitate and support such learning. The three articles in this section present three different ways of supporting self-directed learning.

QUESTION

Narrative Approach

ME THODOLOGY

• Be sensitive to learners’ needs and be flexible about making changes to lessons according to their needs

• Have a supportive learning environment where students can work together as a team

WHAT MIGHT BE OF INTEREST

Supporting Students’ Sense of Relatedness, Competence and Autonomy

How can students’ need for relatedness, competence and autonomy be supported?

supporting

self-directed learning

WHAT MIGHT BE OF INTEREST

Empowering Students through Negotiating and Understanding Performance Benchmarks

• Students have difficulty isolating the descriptors in the rubrics as they assess performances

• When and how the negotiation and co-construction of rubrics are conducted can determine learning efficiency and engagement

Narrative, Observation

ME THODOLOGY

How can studentsbe empowered throughnegotiating and understanding the performance standards/benchmarks?

QUESTION

WHAT MIGHT BE OF INTEREST

Facilitating Student-Student Interactions with Student Self-Assessment Strategies

• How do students interact with one another to achieve the goals of the performance task?

• What self-assessment strategies do students create for themselves to reach the goals of the weekly assessment tasks?

• Students have a variety of self-assessment strategies

• Students’ self-assessment impact how they interact in their groups

• Teacher intervention helps with student interaction

Observation

ME THODOLOGY

QUESTION

16

by Chan Hui Juan, CelineMaha Bodhi School

Supporting Students’ Sense of Relatedness,Competence and Autonomy

This study uses a narrative approach to explore how students’ need for relatedness, competence and autonomy can be supported.

Relatedness, competence and autonomy are three basic psychological needs of people postulated in the self-determination theory (SDT).

COMPETENCE

means the desire to control and master the environment and outcome. We want to know how things will turn out and what the results are ofour actions.

AUTONOMY

concerns with us having a sense of free will when doing something or acting out of our own interests and values.

RELATEDNESS

deals with the desire to “interact with, be connected to, and experience caring for other people” (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Our actions and daily activities involve other people and through this, we seek the feeling of belongingness.

17

WEEK

1Fit the lyrics of the song into the tune that they learnt in solfege

WEEK

3Practice for their assessment task: Create a group song

WEEK

2WEEK

4Scaffolded composition task to match lyrics and tune together

Final rehearsal and performance

This plan was designed and planned with the intention of finding out how students’ motivation could be increased through meeting their needs of relatedness, competence and autonomy in the assessment activities planned.

MY ACTION PLAN

MY STORY

This story is reconstructed from field notes of the entire research process, which covered four weeks of lessons. The story is based on a true account of what had taken place during the lessons. Pseudonyms are given to the characters of the story to protect the identity of the students.

18

The Start of a JourneyChapter 1:

“Ringgggg!!” The moment the bell rang, the excited children of 2A chirped, “It’s time for music lesson!”

With eagerness written all over their faces, they hurried out of the classroom to line up.

“Let’s challenge ourselves to take the shortest time possible to settle down so that we can start learning together,” I said, presenting them with their first challenge of the day.

Taking on the challenge, all 29 members of the class worked together, and in no time, they settled down quickly for the lesson. Clearly, consistent routines combined with clear and manageable expectations do wonders for the class.

We started the lesson off by revisiting solfège hand signs. My original plan was to just do a quick recap before beginning the lesson proper. However, as I observed the students, I felt that they needed a bit more time to revisit what they had learnt earlier, before I could start to build up their existing knowledge.

19

At the back of my mind, I was battling with the lack of time to complete the lesson as planned if I were to spend a little more time letting them build up their confidence in doing their solfège hand signs. It was a struggle. But I knew there was something for me to learn out of this challenge that laid before me; and so, I decided to take the plunge and set aside more time than planned to revisit the solfège hand signs through the use of a familiar song.

After much practice, the class could do their hand signs with ease and confidence when they applied it to a song they had learnt earlier on.

“Yes!! We did it!” the students cheered excitedly with their eyes opened wide, clearly amazed by what they could actually do.

It was a moment to behold, looking at their joy over their sense of achievement. For me as an educator, it had taught me the importance of being sensitive to the learners’ needs and to be flexible about making changes to my lesson according to their current needs.

Adaptability, when coupled with action, creates new opportunities for growth to take place. The deliberate effort made to build up the competence of the students led me to see an increase in their confidence level and also in their motivation to learn. Seeing the enjoyment and smiles on their faces made the extra time spent revisiting the hand signs worthwhile, even though it meant my plans for the lesson had to change. How important it is to stay committed to my decision while being flexible in my approach!

It had taught me the importance of being sensitive to the learners’ needs

and to be flexible about making changes to my lesson according to their current needs.

20

Venturing into the UnknownChapter 2:

As the lesson progressed, I taught the class a new song called Teddy Bear. The moment I flashed the solfège of the song on the screen, I was greeted with puzzled looks.

“Miss Chan, why are you not showing us the lyrics of the song first? We have always been learning it that way,” asked Athan.

The class started buzzing among themselves, trying to figure out what I had in mind. As I stepped back to observe their responses, I knew it was new ground that we were venturing into. Their expressions said it all, as they were surrounded by uncertainty and the fear of doing something that they were not familiar and comfortable with.

When challenges are planned in a structured way, the initial struggle experienced will morph into a

meaningful and beautiful learning experience for the students.

21

I revealed to the class, “We have always been learning new songs through call and response, but today, let us try learning the new song purely using solfège first.”

The class moaned, clearly upset by the change in my usual routine. Louis blurted out desperately, “It’s going to be so tough! We have never tried it before.”

The resistance and struggles that they faced were real. When we first tried it out, the class took a while to learn the song through solfège. Then, I noticed them gradually becoming more comfortable with the new approach and saw their confidence growing.

The class soon started to get the hang of it and eventually, they learnt how to sing Teddy Bear in solfège while doing their hand signs. Seeing that the class was getting familiar with the tune, I asked, “Are you ready for another little challenge?”

As I briefly scanned the room to look out for their readiness level for the next challenge, I saw different emotions written on their faces. I thought to myself, “Everyone’s readiness level is different. How can I help each of them raise their readiness level?” With that thought, I assured the class that we would take on the challenge together.

“Alright, 2A, I’ll be showing you the lyrics of the Teddy Bear song and you will work with your buddy to try and figure out the song together, using the solfège of the song that we had just learnt.”

The moment the lyrics flashed on the screen, the students immediately got started on the little challenge they were given – to fit the lyrics to the tune based on the solfège they had learnt. Some tried out the first line of the song in words while matching the solfège, while others tried singing the song in solfège before attempting to fit the words into the song. The start of a new journey is never easy, but with courage to face the challenge, they eventually started singing the song out loud in unison as a class, bursting with pride that they had figured it out.

“We actually did it!” Louis shared enthusiastically, amazed by his discovery. “I can’t believe it!”

“It’s really fun,” Athan chimed in. “And it’s actually not that difficult to sing the song after learning how to sing in solfège!”

Hearing their responses, I smiled as I watched them slowly transform through the little challenges. It seems that when challenges are planned in a structured way, the initial struggle experienced will morph into a meaningful and beautiful learning experience for the students. The turning point was when the class experienced the ‘Aha!’ moment when they overcame their own struggles and the restrictions that they had originally placed on themselves. Truly, there is no greater journey than the one we must take to discover all of the mysteries that lie within us. I wonder what other discoveries the children will make for themselves as they embark on a journey of self-discovery in their learning process.

22

Unexpected DiscoveriesChapter 3:

After I introduced the pentatonic scale to the class and guided them to sing out the Teddy Bear song, they started commenting excitedly among themselves.

“Miss Chan, this song uses the pentatonic scale,” the enthusiastic boys and girls in the class exclaimed eagerly, as their faces lit up at the discovery that they had made on their own.

The joy I observed in them was priceless. It meant a lot to me to see them being so motivated and engaged from constructing their own understanding and extending their own learning.

I posed another challenge to them – to figure out what notes I was using on the xylophone to play the bordun. Determined to find out what notes were being used, every one of them listened very attentively. After the demonstration of the open and closed bordun, I asked, “Could you hear which notes were being played?”

It is always easy to assume that young children like them are too young to learn

accountability. Clearly, this was not the case.

23

Many hands shot up high in the air as they remembered that one of our class rules is to respect one another by giving others a chance to answer.

Directing my gaze to a shy girl, Hazel, she answered meekly, “Miss Chan, you were playing on the first and fifth notes.”

The rest of the class nodded in agreement excitedly and gave her a thumbs up. When I revealed that they had got it right, the entire class broke out into wide smiles and applauded themselves for a job well done.

For the next part of the lesson, the class and I worked out the melody of the Teddy Bear song on the xylophones. Before I got them to try it out on their own, we played together as a class and they took turns to play out each line of the song. Gradually, I took a step back and allowed them to take over. The moment they were given the space to explore and experiment on their own, the music room was soon filled with the crisp and short sounds of the xylophones and the occasional sprinkle of laughter as the children made little mistakes now and then.

As I watched one member of each group try out the xylophone, a heartening sight greeted me. The other two members were engaged in helping their friend check that they were hitting the right notes. It is always easy to assume that young children like them are too young to learn accountability. Clearly, this was not the case. As I watched the class interact with one another, it amazed me how they took ownership of their own learning and also learnt to be accountable for one another.

24

Overcoming Learning PitsChapter 4:

When they were ready for the last segment planned for the lesson, I gathered them together as a class to brief them on what they would be working on for their group work. Excited murmurs broke out among them as they started their little discussions with their group members before they were sent to their respective group areas to start on their group work.

“Can we get started on our group practice now, Miss Chan? I can’t wait!” asked Louis with a sheepish grin.

The moment my instructions were given, all of them hurriedly gathered their group members. In a flash, they were off to their group areas and started on their discussion.

While the class was busy working together on their group item, I observed an initial struggle in one of the groups. Walking close to the group, I overheard Si Yuan commenting, “I don’t want to play the bordun.”

The rest of his group members tried to negotiate with Si Yuan, but he refused to give in and insisted on playing the melody. It was a struggle to stop myself from intervening. Holding myself back, I continued to observe how they interacted with one another. Eventually, another boy, Justin, offered to let Si Yuan take his place. They may have taken a bit more time than the other groups to iron things out but eventually, they settled on their roles.

25

As I continued to walk around to facilitate the class, I beamed. Seeing the shy ones being encouraged by their friends in the group to try the roles assigned and also supporting one another as they put things together, made me feel proud of how these children overcame their own struggles and came out of their own learning pits with one another’s help.

The room was filled with boisterous laughter as the class made full use of the time given to them to rehearse their group performance. It was amazing to see all 29 of these eight-year-olds so serious and focused as they worked on their parts, and the joy that radiated from within them when they were given the space and autonomy to work things out together on their own without much of my intervention.

When it was time for their group performance, all five groups were eager to showcase what they had prepared within the short time to their peers, as they knew they would have the support and attention of their friends from other groups. The learning environment is a subtle factor, yet one that is so impactful in promoting their learning and in increasing their motivation level. For 2A, they have learnt to trust one another over time, as they know that they are in a safe space to make mistakes and learn together.

As I concluded the lesson, I reminded them that we may all be at different levels of competence and readiness, but together as a team, we can help build each other up and achieve more than what we could have on our own, just like what they had done for their group work. Towards the end of the lesson, the students were excitedly singing the Teddy Bear song in solfège as they made their way out of the music room. Looking at them, I let out a wide smile as they broke out into uncontrollable laughter.

The learning environment is a subtle factor, yet one that is so impactful in promoting their learning and

in increasing their motivation level.

Together as a team, we can help build each other up and achieve more than what we

could have on our own.

26

Going Beyond Comfort ZoneChapter 5:

In the next lesson, we revisited Teddy Bear.

“Can you let us do the entire song of Teddy Bear on our own without your help?” asked Louis, wide-eyed.

The whole class nodded eagerly, desperately hoping that their nods would convince me to agree to the request that was made. I was surprised by how ready Louis and his classmates were to take on challenges, as compared to the previous lesson. It was definitely heartening to see them excited and eager to prove that they could do it. Undeniably, with increased competency in handling a task comes increased confidence to take it on and do it well.

Then, I revealed that we were going to learn another song. Athan asked cheekily, “Are you going to give us another challenge today?”

I was surprised. I had originally thought that they would resist the idea of having yet another challenge come their way. Seizing the opportunity to let them have a choice in how the lesson was structured, I asked, “What do you want the next challenge to be?”

The class was quiet for a few seconds before Si Yuan raised his hand, asking, “Can you let us figure out the song in solfège on our own today?” His classmates nodded readily.

Sensing support from his classmates, Si Yuan added, “We need a different challenge in order to be better than the last lesson.”

27

Not wanting to be a wet blanket, I agreed to let them try out the challenge that they had requested. Without any knowledge of the rhythm of the song, the class was shown the solfège of the song Ding, Dong, Digidigidong on the screen. The moment they saw the solfège flashed on the screen, they began singing the song out loud with the given solfège while exploring different rhythms. Clearly amused by the title of the song, the class started to share the different compositions that they had come up with among themselves. Though this challenge was more demanding as compared to the previous lesson, I noticed a change in the class, from being resistant to being willing to go beyond their comfort zone.

When I revealed the actual rhythm of the song, Athan exclaimed, “Mine is so different from the original song!”

Louis added, “Mine is so different in the rhythm and the tempo, too! It soundedso sad!”

The whole class roared with laughter. When their laughter subsided, Si Yuan reminded the class, “But Miss Chan, you always tell us that it doesn’t matter if we get it wrong, as long as we never stop trying and don’t give up, right?” Si Yuan’s wise words set off the rest, and they nodded their heads vigorously.

“Even if our song is different, at least we made our own song!” joked Louis.

Amidst the laughter shared by the class, I felt unspeakable joy as I witnessed the journey of discovery that the class had embarked on and the learning pits that they were learning to overcome along the way. Though their compositions were not anywhere close to the original song, the way they handled their little setbacks and managed their emotions was a far cry from the start of the journey. That, to me, became one of the defining moments of the journey.

28

A Journey of TransformationChapter 6:

Upon revealing the solfège of the song, the class learnt it within minutes and proceeded to fit the lyrics of the song into what they had learnt. I observed the amazed looks on their faces when they sang the song out loud with gusto, without me having to go through it with them.

When learning is planned intentionally with a clear structure and with proper scaffolding in place, they

make a difference in the way our students learn.

29

“Why were you able to do it?” I posed this question to the class, wanting them to take some time to reflect on their learning.

Hazel, the quietest girl in the class, raised her hand to share her thoughts. “I feel confident and ready to try on my own because I had enough practice while singing out together in solfège,” she said softly, but with a steady eye contact and an assured look.

Clearly, what Hazel said had nuggets of truth in it. Building up their competence is an important aspect of engaging students and increasing their self-determination to do things well, so as to lead them to become more confident in what they believe they can achieve. As I got the class to reflect on their journey, I found myself reflecting along with them as well. It was not just a learning journey for the class. It was one for me as well.

As I watched the class work on the new song that they had learnt on the xylophones, they made me realise that giving them a sense of autonomy to co-plan and refine the lessons with me motivated them to be self-determined and self-directed learners. From the beginning of the journey that the class had embarked on, they had taken on numerous challenges. Though there were struggles experienced along the way, these little struggles had been planned in a structured manner, which led to a meaningful and beautiful learning experience for them.

While looking at them working together, the class reminded me of the transformation of a caterpillar to a butterfly. It was a moment worth reflecting for me as an educator. When learning is planned intentionally with a clear structure and with proper scaffolding in place, they make a difference in the way our students learn. Increasing students’ motivation level and readiness to take on more challenges will transform them into individuals who are intrinsically motivated to give their best and to love what they are learning. All they need is the time, space and the right environment that caters to their individual learning needs to help them grow.

All they need is the time, space and the right environment that caters to their individual learning

needs to help them grow.

30

Taking Ownership Chapter 7:

During group work, as I was walking around the room to facilitate their group discussion and practice, I overheard some groups suggesting role rotation, so as to give others a chance to play the melody or bordun on the xylophone. It was really comforting and heartening to see such positive interaction among the members in each group, and to have the class sharing the responsibility to create a positive, safe and encouraging environment for one another to learn and make mistakes together.

During the group performance, the class volunteered themselves and were eager to show friends from the other groups their items. It surprised me to observe that the students were eager to showcase their performance, even though they didn’t have much time to work on it together. With the laughter I heard and the joy I saw, I am convinced that apart from giving them the space and autonomy to work things out together on their own without much of my intervention, creating opportunities for them to relate to one another and to build trust is pertinent in promoting their learning and increasing their motivation level.

Creating opportunities for them to relate to one another and to build trust is pertinent in promoting

their learning and increasing their motivation level.

31

At the end of this lesson, I gathered the class together as part of the usual class routine to do a quick reflection on what they had learnt. One of the more enthusiastic boys in the class, Coen, shared his observation that they were able to work faster together for this lesson. When I questioned what helped them to work faster, the class shared that they were familiar with the songs and their individual roles in the group. Just then, the bell rang to signal the end of lesson. With springs in their steps, 2A made their way out of the music room. As you would have guessed it, everyone was singing the solfège of Ding, Dong, Digidigidong in unison while bursting into fits of laughter.

32

The Need to ConnectChapter 8:

While all the children were busy practising with their group members in the following lesson, Si Yuan, who had always been very participative, started behaving strangely. He was unlike his usual self. Seated quietly at a corner away from his group members, I was puzzled to see him not joining in with the rest of his group members in the group discussion. I noticed that he looked crestfallen. As he gazed at the floor, I walked towards him to find out what was happening.

On the brink of tears, he sighed, “My group members do not like to work with me. I want to play on the xylophone, but they do not allow me to.” By now, his tears welled up in his eyes and began rolling down his cheeks. In order not to distract the rest, I asked Si Yuan to head out of the music room to share with me more about what was making him sad.

Upon finding out more from him, I asked his group members out to make some clarifications. As it turned out, Si Yuan took it to heart when the rest of his group members wanted to give another member a chance on the xylophone, as she had not had hers in the previous lessons. This genuine intention the rest had, to give everyone a fair chance, was misunderstood by Si Yuan. He had thought that they didn’t like him, and hence, they voted for the other member to have a go at the xylophone. When this was clarified and made known to Si Yuan, he told his group members apologetically, “I’m sorry for thinking that all of you do not want to work with me.”

As teachers, we often only think of the need to connect with our students, but it is also just as

important that we help our students learn to connect with their peers.

33

The next moment, the sight that I saw before my very eyes, touched me beyond words. The rest of his group members actually gathered around him to comfort him and gave him the assurance that everyone in the group plays an important role. Giving him a pat on his back and with some giving him a hug, the entire group went back into the music room after the little misunderstanding had been resolved. As they continued with their discussion and practice, the rest of the group members paid close attention to Si Yuan’s feelings and made sure that he felt included. The atmosphere of the group was instantly changed as they moved on together from the little stumbling block they encountered as a group.

As teachers, we often only think of the need to connect with our students, but it is also just as important that we help our students learn to connect with their peers.

34

EmpoweredChapter 9:

The following week, the day of their actual performance finally arrived. At the start of the lesson, the class of excited children bargained with me for more time so that they could be even better during the final performance. After I had briefed them on the assessment criteria, all five groups went on auto-pilot mode and started rehearsing the group item that they had put together in the previous lesson. While I stood at a corner to observe the children giving their all during their rehearsal, I felt a glow of pride watching them so driven and determined to give their best.

When it was finally time for them to perform their item in front of their other peers, the children amazed me with what they had within them. The past four weeks of their learning journey were made up of numerous planned challenges, but they had shown how they were able to rise up and take on so much more when they were given the autonomy to make choices, and their levels of competence increased progressively. A safe and positive environment combined with the opportunity to work with their peers allowed the students to overcome whatever challenges that were placed in their way, as they helped one another out of their own learning pits.

35

LEARNING POINTS

1 BE ADAPTABLE TO CHANGE

Just as I had intentionally placed challenges for the class, forcing them to constantly adapt to what was before them, the class had in turn challenged me to be adaptable and change accordingly based on the current needs as the lesson progressed.

2 BE INTENTIONAL

In order to grow and nurture a growth mindset in each child, I had to be very intentional in my approach to throw in challenges that would bring them to the next level. At the same time, I had to make intentional effort not to intervene so quickly, so that they could learn how to resolve issues among themselves and in turn learn to be self-motivated learners.

3 EMBRACE CHALLENGES

This journey made me realise how we often place limitations on ourselves before we even make an attempt to overcome the challenge before us. The students had initially shown so much resistance in the initial challenges that I had planned for them. However, challenges, when planned in a structured way, build up the students’ competence and allow them to embrace challenges over time. When the students start embracing challenges, they grow in confidence and are willing to take on even more challenges.

4 GIVE ROOM FOR FAILURE

Failures are always associated with negative feelings and experiences. However, when we change our perspectives towards failures, it can bring about positive learning points. Seeing how the class took on the challenges and struggled with them at the various learning pits made me realise there is a need to provide students with the space to experience failures, so that they can eventually learn to rise up and take on the challenges. Supporting their needs for relatedness, autonomy and competencies when they fall, encourages them to embrace and take on the challenges.

5 FIND THE RIGHT BALANCE

The power of self-fulfilling prophecies was evident as I observed how the expectations I had of the students in turn made them believe in what they were able to achieve. Knowing that I had the power to mould their behaviour, I realised that it is especially important that we do not undermine their potential or cause them to stumble with our overambitious expectations of them.

36

LEARNING POINTS

7 KEEP EXPECTATIONS IN CHECK

By giving the class autonomy to co-create the lessons with me and giving them a voice to share their views, they became motivated to take on the tasks, as they take on the ownership of their learning. However, giving too much autonomy has its repercussions, too. There were times when they became too engrossed in the control that they were given and they came up with challenges that are good for growth but too challenging for them. This, instead of motivating them, may end up demoralising them, should the challenge be too hard and their level of readiness and competence unmatched. Hence, we need to discern and decide when we can let go and when we need to hold back.

6 GET OUT OF COMFORT ZONE

I’ve lost count the number of times that the class and I were pushed out of our own comfort zones. It’s nice to stay in our comfort zone where everything stays the same. However, if we were to always stay within our comfort zones, we will never be able to progress beyond them and explore other areas that we could have ventured into. In order to motivate the class, the three basic psychological needs were met through the structure, activities and support put in place for them. Though students were initially reluctant and resistant, they eventually came out of their own learning pits and emerged much stronger, motivated and confident in knowing that they are able to do greater things.

37

by Katherine FaroekAng Mo Kio Primary School

Facilitating Student-Student Interactions with StudentSelf-Assessment Strategies

RESEARCH PURPOSE

LITERATURE REVIEW

To determine how student learning in playing the ukulele can be enhanced through meaningful interactions between them in a group work setting and through using student self-assessment strategies.

• Student self-assessment is regarded as vital to success at school and is “an essential component of formative assessment” (Black et al., 2003).

• Self-assessment is a valuable learning tool as well as part of an assessment process. Through the process, students can identify their own skill gaps, see where to focus their attention in learning, set realistic goals, revise their work and track their own progress. (Stanford University, n.d.)

• In an ideal situation, students will begin to improve their ability of monitoring or tracking of targets which had been set. In practice, students’ ability will be different and the teacher’s role as a facilitator will become more important for some students.

QUESTION

How do students interact with one another to achieve the goals of the performance task?

What self-assessment strategies do students create for themselves to reach the goals of the weekly assessment tasks?

INTERACTION MEANS:

SELF-ASSESSMENT INCLUDES:

• How they work with one another• How they assess themselves e.g. their own self-assessment based

on the feedback they receive from one another• How they observe others to improve

their own performance

• Individual self-assessment• Group self-assessment• Peer-assessment within the group

Through interaction with their peers, students gain knowledge from their peers and then apply it in self-assessment. Peer interaction is therefore an important step which promotes their own learning and achievements.

38

THE CURRICULUM

THE CONTEXT

30-minutemusic lessons, twice a week

Students have

no prior knowledgeof playing the ukulele

A Primary4 class of

32 students

This study reliesheavily on field notes of student-studentinteraction and recordings oftheir conversations.

ME THODOLOGY

PROCESS

Teacher gives assessment tasks

Teacher observes students’ work –how they interact and their self-assessment strategies

1

2

39

UKULELE LESSONS

Lesson Objective

Play C chord on the ukulele as they sing as a group

Assessment Task

Perform by playing and singing in groups withthe C chord

LESSON 1

Lesson Objective

Play G chord on the ukulele as they sing as a group

Assessment Task

Perform by playing and singing in the groups with the C and G chords

LESSON 2

Lesson Objective

Play F chord on the ukulele as they sing as a group

Assessment Task

Perform by playing and singing in groups with the C, G and F chords

LESSON 3

ASSESSMENT RUBRICS

Beat and Rhythm

The beat is usually erratic and seldom accurate, detracting significantly from the overall performance.

The beat is somewhat erratic with repeated errors which occasionally detract from the overall performance.

The beat is mostly secure. There are a few errors, but these do not detract from the overall performance.

The beat is secure and accurate throughout the performance.

Chord Changing Accuracy

The group is able to keep very few accurate chords.

The group is able to keep some accurate chords but there are frequent repeated fingering errors.

The group is able to keep most of the chords are accurate using correct fingering with an occasional fingering error.

The group is able to keep the chords are very accurate. There are completely no fingering errors.

Able to play and sing together in a group

The group is unable to sing and play at the same time.

The group is able to sing and play at the same time but with frequent mistakes.

The group is able to sing and play at the same time but with little mistakes.

The group is able to sing and play at the same time with no mistakes. High confidence level was also portrayed.

C G

40

CREATING OPPORTUNITIES FOR STUDENT-STUDENT INTERACTION

FACILITATING GROUP WORK

Students were put into different groups assigned by the teacher. Even though they were in the same class, some students hardly spoke with one another before. The first challenge of setting the class for group work was getting them to be comfortable with one another so that effective discussion could take place.

Teacher also gave guidelines to help students before each session. Examples are:

• Make sure all your members have correct fingering on the correct string and fret.• Don’t leave anyone behind!• Make sure every member in the group are playing to the beat together. • Can everyone change chords at the correct places?• Play one C chord, followed by one G chord and a C chord. Play the pattern continuously. • Most importantly, remember to keep on practising and never give up.• Help your friends in need achieve success!

41

CASE STUDIES

Key observations:

• Strong leadership in a group helped the group attain greater success in evaluating one another’s performance.

• Constant revision and improvement is an integral part of self-assessment and peer assessment. Some students were able to confidently assess their peer’s weaknesses and progress and find ways to coach their peers. When they were able to assess themselves and their peers, their independence and motivation improved.

CASE STUDY 1

Key observations:

• The leader of the group constantly encouraged her group members to play with confidence, with words like “sing loudly”, “let’s try again”.

• A high level of peer assessment took place as the leader heard each member play one by one and corrected them individually. The group members benefitted from her guidance and improved their own learning based on her feedback.

CASE STUDY 2

Key observations:

• One student, who has a natural flair for music, sang the loudest and overshadowed the rest of the group.

• This group did not listen to one another. Most of the time, group members devised ways to learn how to play with the right fingering by observing what one student was playing and tried to catch up on their own by looking at their own fingering.

CASE STUDY 4

Key observations:

• This group needed more teacher facilitation in ensuring that their group was doing their peer and self-assessment.

• The abilities of the group members were

similar; they lacked communication and did not observe one another at all when they were playing as a group. All of them could play the song and sing together. They played the song over and over again without checking on one another. After a while, they stopped because they did not know what else to do.

• It was apparent that they lacked self assessment and peer assessment skills. They did not even realise that one of their group members was playing the note with the wrong fingering. Therefore, in this group, the teacher had an important role in teaching them how to observe one another and constantly bring them back to the purpose of the group work.

CASE STUDY 3

42

KEY FINDINGS

The strategies which the students used to achieve the assessment task included:

• Asking each member to play one at a time while the rest of the group members listened

• Playing together as a group, stopping only when one of the group members made mistakes

• Learning from more confident peers who either modelled for the group or coached the group members

• Splitting the group further, usually into pairs

Student-student interactions:

• Strong leadership can encourage weaker students achieve greater success

# Students who possessed strong assessment capabilities were able and motivated to use information from the peer assessment and self-assessment to affirm or further their learning.

• Student interactions were richer in mixed groups (abilities, learning styles, personalities)

# When the students were actively engaged in peer assessment, they stayed involved and motivated in the learning process. This enabled them to take greater responsibilities in their own learning.

• Teacher intervention helped with student interaction e.g. quieter groups

# The teacher needed to establish clear assessment criteria and how to apply them in grading their work.

# The teacher needed to facilitate discussion among the students to improve the quality of their discussions so that the time spent in the group work benefitted their learning.

Self-assessment:

• Students have their own individual self-assessment strategies

• Students who self-assessed themselves as ‘better’ will drive the self-assessment of the group through peer assessment

• Students who self-assessed themselves as ‘weaker’ will follow a model of excellence within their group

• Group interaction may help students individually self-assess (e.g. they have models of excellence to follow)

• Not all students were able to do group self-assessment – therefore teacher intervention (e.g. questions) could get them to think about how to help themselves as a group

43

CONCLUSION

The teacher has an important role to play in students’ self-assessment. It involves:

• Helping students develop self assessment capabilities

• Recognising that self-assessment is a valuable tool in learning

# When students are in groups with mixed abilities, they are able to identify their own skill gaps, where their knowledge is weak and see where they can focus their attention in learning and track their own progress. Thus, the students experience an improvement in their learning because they come to know how they learn rather than just what they learn.

1

2

3

4

5

identifytheir own skill gaps, where their knowledge is weak

seewhere to focus their attention in learning

setrealistic goals

revise their work

tracktheir own progress

44

by Sharon Ng Wai YeeGuangyang Primary School

Empowering Students through Negotiating and Understanding Performance Benchmarks

Our school’s Annual Pupil Survey revealed a lack of confidence in singing, dancing and playing instruments amongst students. The reasons included a lack of self-awareness and a lack of language to be able to describe what their gaps are.

Hence, this project was conceived to address these concerns, so that students can be empowered to take ownership of their learning.

LITERATURE REVIEW

• ‘Teaching for understanding’ … involves iterative processes of doing and understanding, as shown in this diagram (Fautley, 2010, p. 94-95).

• Sustainable assessment is ‘assessment that meets the needs of the present and prepares students to meet their own future learning needs’ (Boud, 2000, p. 151).

• Rubrics give structure to observations. Matching your observations of a student’s work to the descriptions in the rubric averts the rush to make judgments that can occur in classroom evaluation situations. Instead of judging the performance, the rubric describes the performance (Brookhart, 2013).

QUESTION

How can students be empowered through negotiating and understanding performance standards/benchmarks, in order to bring about a deeper understanding of a musical performance?

Understanding

Understandingevidenced in achievement

Learning by doing

Doing

Empowered students – motivated, confident to perform, desire to improve, awareness of standards and able to apply them

45

A qualitative study that examines two music lessons1 through:

• Narrative research• Observation research

Data tools:

• Post-lesson field notes (personal journal)

• Focus group discussions• Videos (artefacts of

students’ performances)

Participants:

• 10 Primary 32 students with mixed abilities

ME THODOLOGY My Journey: Lesson 1

1. Using YouTube videos, I showed students two ukulele performances.

2. I asked students to notice what is required in ukulele playing:

a. how the sound is produced b. parts of a ukulele c. how to hold a ukulele d. cannot touch other strings e. strumming patterns leading to chord changes matching

the melody of the song f. importance of strumming in time g. strumming techniques (right and wrong) h. importance of changing chords in time

Introduction to ‘raw’ beginners who have never handled a ukulele

Recognising the importance of teaching for understanding through a spiral curriculum, we want learners to meet their own future learning – to ‘learn how to fish’ by understanding what is expected through rubrics and bring about a more sustainable and deeper understanding of their own performance.

1Between Lessons 1 and 2, the teaching of ukulele was done by a vendor. After Lesson 2, there was another lesson by the vendor, followed by the actual assessment.2Primary 3 is the level when students first start to learn the ukulele.

Main intent was to create an awareness of various aspects of handling the instrument. This would preempt students what to expect and what they were about to learn for the upcoming term.

46

3. I elicited responses from students on what makes a good performance.

4. They continued to watch the second clip.

5. I asked students why they had enjoyed the performance and we brainstormed what made the two performances so good:

I asked students what they thought of that performance. Many said they enjoyed it and hoped to be able to play the ukulele like the performer on YouTube.

During the interactive segment, the students were invited to sing along and they were delighted! They had the opportunity to experience singing while being accompanied by strumming on the ukulele. As educators, we know this is an important aspect in teaching and learning - a good exemplar, coupled with positive feelings invoked. The value of practising diligently was also mentioned.

Contributions from Students

Eye Contact Example cited was You are my Sunshine in which the performer maintained a steady gaze to the front

Posture was good forboth performances

Interactive Example cited was “invited the audience to sing along”

Played continuously An unexpected answer from the students but it showed us the children’s perspective

Strumming (referring to the right hand) – in time and in tune

Chord knowledge The students were not yet aware of the correct fingering to be used by the left hand

Singing along & movingalong with the music

I accepted all their answers and they were forthcoming and enthusiastic. There were answers I had not expected such as ‘playing continuously’ and the ‘interactive’ aspect. It is definitely true that a good performance must be played continuously, and these are words from children. Even at the age of nine, the children noticed the engagement level of performers.

47

6. I shared with students an example of rubrics for singing (taken from Otto Petersen Elementary):

The above set of rubrics was taken from Otto Petersen Elementary (an American School). What is so special about this set of rubrics? Yes, it is the USE OF QUESTIONS!

I specifically chose ‘SINGING’ because singing is something that the students are very familiar with, hence it allows us to teach from known to unknown, concrete to abstract. Surely, students can relate to aspects of signing such as singing in tune, singing the correct rhthym and phrasing.

Questions I ask about my work

I’m still learning how to do it. (1)

I basically get how to do it, and I’m getting better. (2)

I can do this pretty well. (3)

I perform at an advanced level. (4)

Do I sing the right notes?

Do I sing in tune?

I’m still working on singing the right notes. I sing a small range of notes and may match the shape of the melody, but my notes may not be the same ones in the song.

Most of my notes are right and I sing mostly in tune, but I make a few bigger mistakes.

My notes are right and I sing in tune, but I may make a couple of small mistakes.

All of my notes are right, and I sing in tune very well.

Do I sing the right rhythms? Is my beat steady?

I make many rhythm mistakes. I have trouble keeping a steady beat when I sing, or I start and stop often.

My rhythms are pretty close, though a few may not be accurate. I may not keep a steady beat the whole time.

My rhythms are good, and my beat is pretty steady.

My rhythms are all correct, and I maintain a steady beat the whole time.

Do I sing with a great tone quality? Do I sing the words clearly?

I am still working toward using an open and free tone. My tone is harsh, forced, pinched, or breathy. It is hard to understand many of the words I sing.

My tone is OK, but may sound a little bit harsh, forced, pinched, or breathy. Some of the words may be hard to understand.

My tone is usually open and free. My words are pretty easy to understand. Most of my vowels are pure and most consonants are clear.

I always use an open and free sound when I sing. It is easy to understand the words I sing. My vowel sounds are pure and consonant sounds are clear.

Do I sing with a good body position and posture? Do I use my breath well?

My body is not ready to sing. I may be slouching, have my mouth nearly closed, or my head down. I do not take a breath big enough to help me produce a great singing tone.

My body may not be positioned in the best way for singing. My head may be down, I may slouch, or my mouth is not open enough. I took a breath that was too small or shallow.

My head is up, my mouth is open, and I take a big breath to support my singing voice.

My body position makes it easy for me to get a great sound when I sing. My head is up, my mouth is open, and I take a big breath that supports my singing voice well.

48

7. I facilitated students to develop questions for ukulele performances:

Criteria drawn from earlier brainstorm Questions developed by Students

Posture Am I holding the ukulele correctly? Do I look up confidently?

Chord Knowledge (Left Hand Fingering)

Do I press the correct strings?Do I touch the other strings?

Strumming (Right Hand)

Are all 4 strings strummed consistently without any finger touching other strings? Do they match the tune?

Chord Changes Do I change chords at the correct time?Did this match the melody?

Singing Do I sing in tune?

8. Students worked in pairs to grade exemplars of video performances I recorded from their seniors who performed on the ukulele:

Video clip 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Posture

Chord Knowledge (Left Hand Fingering)

Strumming (Right Hand)

Chord Changes

Singing along while playing

At this stage, the descriptors have not been written/ developed yet. So, I told them that 4 stars = excellent, 3 stars = very good, 2 stars = fair, 1 star = improving. I noticed that the way students graded were rather haphazard and their judgement was affected by the other/different aspects. For example, a student gave 1 star for Posture and when I asked why, his response was “the singing was out of tune”. What about the Chord Knowledge? The response was “the chords were not together with the music...”. Hence, there were only vague ideas between chord changes and strumming.

49

Reflections on lesson 1

1. The strength of the lesson was developing the questions together with the students.

2. The awarding of stars by using ‘Excellent’, Very Good’, ‘Fair’ was

NOT a good strategy. The experience

reminded me that students do get distracted by other aspects instead of focusing on a single aspect.

3. Expecting students to write out the band descriptors would require too much use of language for the Primary 3s and I decided to make adjustments to the approach in the next lesson.

4. I would continue to empower students towards better musicianship with a better understanding of the rubrics (aka band descriptors).

My Journey: Lesson 2

1. I revisited the YouTube exemplar Row, Row, Row Your Boat. Students had had lessons on ukulele conducted by the vendor since my

last lesson.

2. I reminded students of the five criteria that contribute to a good performance:

• Posture and fingering • Knowledge of Chords • Chord Changes • Strumming in Time • Singing in Tune (depending on abilities)

3. I asked students, “Do you think rubrics are more important for the students or for the teacher?”

Students’ responses included:

• ‘They are useful for students to make improvements for the future’

• ‘Students can try harder in the next lesson’• ‘If there are no rubics, we do not know what we are weak in’• ‘Rubrics are important for teachers, so that they will know

how to advise students’• ‘Both teachers and students can work together to improve

in the playing of the ukulele, it’s useful for everyone’

4. I went through the construction of rubrics with students:

• Reminded students to focus on a single aspect and not be distracted by the singing or other criteria of assessment

• Had a whole group discussion and went through the criteria on ‘posture’ and ‘singing’ before breaking them up into groups.

• Divided students into four groups, provided each group with two video clips, and assigned each pair to look at a specific criterion (e.g. strumming, chord knowledge, chord change, singing)

• Informed them that each clip has been awarded a certain number of stars, and their task was to work out the band descriptors for the criteria.

50

Example of Template - Writing band descriptors in groups

To simplify the process, three of the four band descriptors were given in this example.

5. I went through exemplars for each descriptor to calibrate the scores with students.

Questions I ask about my work.

I perform at an advanced level. (4)

I can do thispretty well. (3)

I basically get how to do it, and I’m getting better. (2)

I’m still learning how to do it. (1)

Two Chord Knowledge(LH fingering) • Do I press the correct

strings?• Do I touch other strings?

• All the strings are correctly pressed.

• All chords are correctly played without touching other strings.

• Most of the strings are correctly pressed.

• Most chords are correctly played without touching other strings.

• Strings were correctly pressed only once or twice

• Most chords were wrongly played on wrong strings.

Write the number of the example or name of student in the various columns for 4-3-2-1 stars =>

1. Good facilitation techniques were required in helping students to understand the rubrics and arrive at a consensus on the various criteria of assessing a ukulele performance.

2. Students were engaged in the discussion and supported their responses with reasons.

3. They were able to understand why the

teacher had awarded x no. of stars for a certain criterion for a video example.

of the rubrics (aka band descriptors).

Reflections on lesson 2

DISCUSSION

TEACHERS’ PERSPECTIVE

Challenges

• Time is a challenge• Getting students to buy-in the idea of

co-construction• Students may have difficulty in

isolating descriptors when assessing e.g. posture and singing

Benefits

• Develop common language and benchmarks amongst students

• Showing exemplars provides greater clarity to benchmarks and is able to motivate the students

• Allows time for students to apply their learning

51

BENEFITS IN EMPOWERING STUDENTS THROUGH NEGOTIATING AND UNDERSTANDING PERFORMANCE BENCHMARKS

CONCLUSION

• Develop shared language – for the younger learners, this can be considered part of the language acquisition process

• Enhance quality of learning • Enhance thinking in the learning processes

What students said about their learning:

• “Know what is a good posture”• “I now know I must strum all four strings”• “I now can understand the expectations of

3 stars, 4 stars and try to work towards it”• “I can try to improve to get more stars”

How students felt:

• “It was fun and enjoyable”• “I can learn from my friends and make

improvements”• “I was surprised! I did not know that my

friend had such a good understanding of performing the ukulele! These are good opportunities to learn from one another!”

Reflection

• Students see rubrics/benchmarks as a tool towards improvement

• Students are able to learn from one another

• Students motivate and influence one another

• The key challenge is that students need reminders and opportunities to practice

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

• Operability – weighing shorter-term time constraints with longer-term benefits

• Simple process/format of calibration of rubrics to facilitate understanding

• Selecting and calibrating standards using video exemplars – simpler and more practical approach

STUDENTS’ PERSPECTIVE

Reflection

When is a good time toco-construct rubrics?

• Facilitating co-construction of rubrics at the start of the module when the students are new to an area of music provides an initial insight to the different aspects and introduces new terminology.

• Facilitating a more in-depth discussion after two to three lessons helps students better understand the expectations and work towards an improved musical performance.

• Joint negotiation of expectations using authentic assessment artefacts is meaningful as we “teach less, learn more”.

FUTURE POSSIBILITIES

• Provide adequate professional development for teachers in this area – i.e. facilitation skills and questioning techniques, or even teaming together to do the calibration

While we may think of using the shortest and most effective approach, the effort made in going through this process of negotiating and understanding performance benchmarks and rubrics will certainly reap longer-term benefits. This kind of experience will definitely remain etched in the students’ minds for a longer time.

Checking for Understanding and Providing Feedback are approaches to ascertain the gap between students’ current understanding and the desired learning outcomes, and to close this gap. This section examines two less often discussed areas that could lead to enhanced student learning outcomes.

checking for

understanding andproviding feedback

QUESTION

Comparison of Assessment Data

ME THODOLOGY

• Using rubrics in assessment does not necessarily mean there is shared language and shared understanding of assessment criteria

• Co-reviewing of rubrics and co-assessing with students

increase student understanding of assessment process and criteria

WHAT MIGHT BE OF INTEREST

Comparing Students’ Evaluation and Teacher’s Evaluation of Group Performances

How do students’ peer evaluation compare with the teacher’s evaluation of group performances through a rubric that is co-reviewed by teacher and students?

WHAT MIGHT BE OF INTEREST

Improving Student-Student Feedback Using Socratic Questioning, Accountable Talk, andCo-Construction of Rubrics

• Students’ responses may not necessarily reflect their levels of musical understanding as many factors influence their thinking

• Varied facilitation strategies help teachers look beyond the quick responses on the surface to explore deeper understanding and meanings

Qualitative Observational Study with Content Analysis and Discourse Analysis

ME THODOLOGY

How do facilitation strategies improve feedback among students in a music classroom?

How do students respond to different facilitation strategies (e.g. Socratic questioning, Accountable Talk, Co-construction of rubrics)?

QUESTION

56

by Tan Keng HongCanberra Primary School

Comparing Students’ Evaluationand Teacher’s Evaluation ofGroup Performances

In 2015, the Music teachers in my school came together to review and redesign our existing rubrics. Since then, we have used the revised rubrics faithfully. However, we could not be certain how reliable they were, and if our students really understood them. Ideally, our students should be using the rubrics to assess their peers’

and their own learning in the same way as the teacher. But in order to ascertain if that was the case, an inquiry would help shed some light.

If it turned out that my students neither understood nor used the rubrics in the same way as their teacher, I wanted to find out ifco-reviewing the rubrics with my students would help to bridge the gap towards building common musical understanding between them and me.

This research was inspired by Nancy Whitaker’s findings on ‘Instructional Change Through Rubrics Evolution’, which were presented at the 6th International Symposium on Assessment in Music Education (ISAME) in UK.

57

RESEARCH PURPOSE

To achieve a shared language for assessment of group performances within the primary General Music context.

Why students should be involved in the assessment process:

• “… it may be more helpful to think of knowledge as a continuum, … as constructed or co-constructed by the learner/s…” (E. Hargreaves, 2005, cited in Fautley, 2010, p. 54)

• The purpose of music assessment differed between the teachers’ and learners’ perspectives. Students should be involved in the decision making process for their music assessments (Mogane, 2017)

• “… individuals extend their musical understanding by engaging actively with teachers and peers … (Scott, 2012, p. 31)”

• “Our task as teachers is to help students learn and we can harness the power of assessment to achieve this end by involving them in the process (Falchikov, 2003, p. 102)”

• “… have found that devolving some responsibility to students by involving them in self and peer assessment is an excellent way of enhancing the learning process (Falchikov, 2003, p. 107)”

QUESTION

How do students’ peer evaluations compare with the teacher’s evaluations of group performances through a rubric that is co-reviewed by teacher and students?

HYPOTHESIS

Involving students in the assessment process through co-review of rubrics with their teacher improves the accuracy of their peer evaluation.

LITERATURE REVIEW

58

FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT TASK

Canberra Primary SchoolPrimary 4 Music

Music Assessment - Recorder Playing & Bass AccompanimentTerm 3

In groups, students will be able to:

Assessment Outcomes

• Compose the bass accompaniment using notes G and D (or other improvised notes)

• Notate their bass composition and letter names on Ode To Joy score.

• Play the melody and bass accompaniment of Ode To Joy

on the recorder with the correct fingering and technique, and use the Bass Xylophone for bass accompaniment.

4 Lessons, 8 periods approximately

Students have already learnt to play notes E to high D on the recorder.

Duration:

Prior Knowledge:

The formative assessment task required our Primary 4 students to perform the piece Ode to Joy by Ludwig van Beethoven in groups of five or six. They had to play the melody on the recorder and compose a suitable bass accompaniment using the notes as stated. Only one or two members of each group were to play the bass on the bass xylophone(s); the rest were to play the melody on their recorders.

59

Primary 4 Music AssessmentGroup Recorder Playing & Bass Accompaniment

Term 3 - Weeks 8 to 10

My Name: Date:

Class: Teamwork ( ) Marks: /18Group being assessed:

My Group Members Role My Group Members Role

1. Melody/Bass 4. Melody/Bass

2. Melody/Bass 5. Melody/Bass

3. Melody/Bass 6. Melody/Bass

In groups,

1. Compose the bass accompaniment using notes G and D (or as otherwise instructed) to accompany the piece, Ode To Joy.

2. Play the melody on the recorder with the correct fingering and technique. Play the bass accompaniment* on the xylophone. (*Only a maximum of 2 pupils per group can play the accompaniment)

3. ^ Demonstrate creativity. E.g. creative stage entrance and exit, changing of tempo/ dynamics, interesting bass accompaniment, etc.

4. Perform the piece for the class

For every lesson within the period of the inquiry, each group was given the peer evaluation handout for them to assess their peers’ group performances. Their responses were collected at group level. Every group

(except the performing group for that lesson) needed to discuss and decide what scores and feedback the performing group deserved. The above shows the top part of the handout.

60

Rubrics for Group Recorder Playing & Bass Accompaniment

For every lesson within the period of the inquiry, each group was given the peer evaluation handout for them to assess their peers’ group performances. Their responses were collected at group level. Every group (except the performing group for that lesson) needed to discuss and decide what scores and feedback the performing group deserved. The above shows the top part of the handout.

Description MarksAwarded

Developing Competent Exceeding

Criteria 0-1 2-3 4

Fluency Beat is inconsistent.Some rhythms are accurate. Some pitches are accurate.

Beat is somewhat consistent. Rhythm is mostly accurate. Pitch is mostly accurate.

Beat is consistent. Rhythm is accurate. Pitch is accurate.

Tone Performed with correct fingerings and a clean tone occasionally. Squeaks may occur.

Performed with correct fingerings and a clean tone most of the time. A few squeaks may occur.

Correct fingerings, performed with a clean tone and tonguing.

Ensemble Playing

Members are mostly unable to keep together throughout the performance.

Members are able to keep together in most parts of the performance.

There is a good coordination between members to present a cohesive performance.

Criteria 1 2 3

^ Creativity Musical ideas are not developed and do not connect well.

There is some exploration and development of not more than two musical ideas.

There is exploration and development of at least two musical ideas.

Attitude Self-discipline and Teamwork values during the group rehearsals & performance are seldom displayed.

Self-discipline and Teamwork values are displayed most of the time during the group rehearsals & performance.

Self-discipline and Teamwork values are displayed throughout the group rehearsals & performance.

In the bottom section of the handout, each group was provided the rubric for their reference. After the performing group had performed, each group was to discuss and finalise their marks for the performing group. The marks collected through the above form the quantitative data for the inquiry.

61

Peer Feedback

Strengths

After observing your friends’ group performance, pen down at least 1 strength and 1 area for improvement for them. Your feedback should address items from the rubrics.

Areas For Improvement (AFI)

Bass Accompaniment

Compose a bass accompaniment using notes G and D (or as otherwise instructed) and notate it on the score below.

On the next page of the handout, each group was required to write down their feedback for the performing group. As shown above, each group was to write at least one strength and one area for improvement (AFI). They should also use the terms from the rubric to express their feedback clearly for their peers. The feedback collected through the above were the qualitative data for the inquiry.

And finally, the score of the relevant part of the piece with blank bars for bass composition was provided at the bottom of the second page.

Ode To JoyMusic by Ludwig van Beethoven