Sisters at the Rockface – the Van der Riet Twins and Dorothea Bleek's Rock Art Research and...

Transcript of Sisters at the Rockface – the Van der Riet Twins and Dorothea Bleek's Rock Art Research and...

This article was downloaded by: [T&F Internal Users], [kara Kilian]On: 26 July 2011, At: 03:21Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

African StudiesPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cast20

Sisters at the Rockface – the Vander Riet Twins and Dorothea Bleek'sRock Art Research and Publishing,1932–1940Jill Weintroub aa Programme on the Study of the Humanities in Africa, Universityof the Western Cape

Available online: 25 Nov 2009

To cite this article: Jill Weintroub (2009): Sisters at the Rockface – the Van der Riet Twins andDorothea Bleek's Rock Art Research and Publishing, 1932–1940, African Studies, 68:3, 402-428

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00020180903381297

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representationthat the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of anyinstructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primarysources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly orindirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Sisters at the Rockface – the Van derRiet Twins and Dorothea Bleek’s RockArt Research and Publishing,1932–1940

Jill Weintroub

Programme on the Study of the Humanities in Africa, Universityof the Western Cape

This article discusses the processes, networks and contingencies underlying the making of scientific

knowledge in the field, theorising these in relation to scholarship dealing with the field sciences

which has engaged with the dynamics of ‘the field’ as complex site and context of knowledge pro-

duction in particular disciplines. Drawing on the archive and scholarship of Dorothea Bleek, it

examines a particular field research project centred on the reproduction of rock art and contrasts

the ‘dirty’ detail of fieldwork with the sanitised texts produced later for public consumption. It

describes the creation of knowledge in the field as a contingent, interactive and haphazard

process at the rock face rather than the purposeful, coherent and methodical practice later presented

as authoritative scientific knowledge.

Through a close examination of a small-scale field research project, the article examines the per-

sonal relationships between the researcher and her assistants, and the broader social and political

networks in which the particular inquiry was located. It shows how both the researcher and her

assistants are inscribed into the outputs they produce in a variety of subtle ways and how knowledge

flows in both directions between researcher and assistants. It describes how methodology develops in

organic, pragmatic ways often in reaction to the specifics of a particular field site and how the affec-

tivities in terms of personalities and energies of the research assistants contribute to and influence

research results. In addition, it examines the ways in which local or indigenous knowledge may be

mediated through research assistants and supervisor to become part of the scientific knowledge that

emerges at the end of the process.

Key words: Dorothea Bleek, rock art, rock art reproduction, knowledge production, scientific

discourse, fieldwork, research assistants, female networks, intimacy, marginality

Dorothea Bleek’s third publication on rock art appeared in 1940. Judging from its

steady sales figures, More Rock Paintings in South Africa was received by an

interested public both in South Africa and abroad (Van der Riet and Bleek

1940).1 The Royal Quarto volume featured paintings ‘mainly copied’ by Joyce

and Mollie van der Riet, with an ‘introduction and explanatory remarks’ by

Dorothea Bleek. Inside are colour reproductions of rock art images, a number

of photographs, as well as notes related to the location and meaning of the

painted reproductions. But its handsome marbled cover and smart red binding

ISSN 0002-0184 print/ISSN 1469-2872 online/09/030402–27# 2009 Taylor & Francis Group Ltd on behalf of the University of WitwatersrandDOI: 10.1080/00020180903381297

African Studies, 68, 3, December 2009

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

fail to give any indication of the complex processes of knowledge creation and

production which are encoded within its pages. Bleek’s seamless texts, in adhering

to the demands of scientific discourse, gloss over and silence aspects of the

negotiated, faltering and haphazard ways in which field-based observation and

investigation became repackaged as cultural or scientific knowledge.

The rock art scholarship of Dorothea Bleek, of which the book cited above

represents something of a culmination, provides a useful lens through which

aspects of rock art research practices and methodologies may be examined.

While at work on my broader project, which seeks to situate the scholarship and

archive of Dorothea Bleek both in its own time and in the postcolonial present,

it occurred to me that aspects of her fieldwork could throw light on the development

of rock art research methods during the early decades of the twentieth century. The

close reading of Bleek’s rock art fieldwork that I present here contrasts the ‘dirty’

detail of fieldwork with the sanitised texts produced later for public consumption. It

reveals the creation of knowledge in the field as a contingent, interactive and

haphazard process at the rock face rather than the purposeful, coherent and meth-

odical practice later presented as authoritative scientific knowledge. It furthermore

works with notions of intimacy and social networking as essential components in

the creation of knowledge in the field, with the often-unacknowledged role of

research assistants in these processes, and with the transformation of intimate,

local or indigenous ways of knowing and understanding into authoritative scientific

knowledge (Raffles 2002; Latour 1987).

My argument focuses on a specific research interaction, looking not only at the

personal relationships between the researcher and her assistants, but also at the

broader social and political networks in which the particular episode of field

inquiry was located. For Dorothea Bleek’s research at this particular moment,

the broader framework was the emergence of rock art as a discrete field of

study located within the sciences, yet straddling archaeology and history. I offer

a close reading of a small-scale fieldwork project in which the personal and inter-

active processes, which underlie the making of knowledge in the field can be

revealed. I have had access to a set of private letters, which I have read alongside

the public record of a fieldwork project.2 I have selectively constructed a narrative

in which I examine the gap between these private and public texts based on the

same fieldwork project. In my narrative, I have on the one hand, sketched the

unfolding of rich idiosyncratic detail, spontaneity and interactivity underlying a

formally constructed fieldwork project, and on the other hand, related the

making of sanitised official texts where all subjective experiential information

has been written out. In this narration of a particular fieldwork project, I have

tried to show how both the researcher and her assistants are inscribed into the

outputs they produce in a variety of subtle ways and how knowledge flows in

both directions between researcher and assistants. I show also how methodology

develops in organic, pragmatic ways often in reaction to the specifics of a particu-

lar field site and how the affectivities in terms of personalities and energies of the

Sisters at the Rockface 403

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

research assistants contribute to and influence research results. Finally, I have tried

to give a sense of the ways in which local or indigenous knowledge may be

mediated through research assistants and supervisor to become part of the scien-

tific knowledge that emerges at the end of the process.

Intimate and Marginal

It seems useful to think of Dorothea Bleek’s research as both ‘intimate’ and ‘mar-

ginal’, remembering the notion suggested by Natalie Zemon Davis (1995:210) of

the margin as ‘a borderland between cultural deposits’, which may be reconstituted

as a locally defined centre. Resisting easy binaries, Zemon Davis examines notions

of the ‘marginal’ by exploring the autobiographical writings of three seventeenth

century women, whose lives offer an illustration of ‘the significance of writing

and language for self-discovery, moral exploration and . . . the discovery of

others’ (1995:64–5). One of the women, the Jewish merchant, wife and mother

Glikl bas Judah Leib, writes herself and her religion into the centre of a world

that was mostly constrained against her (Zemon Davis:38–45). Similarly, Dorothea

Bleek’s research project described here may be understood as being part of a

process of establishing herself as central to her own, self-constituted world,

rather than marginal to the broader mostly male-dominated work of knowledge-

making that was continuing around her. Thus, in these instances, we see how

individual projects of writing and knowledge-making may serve as a means of com-

plicating easy oppositions between centre and periphery, and instead function as a

means of accessing the fluidity inherent in notions such as centre and margin.

In using the term ‘intimacy’ as a framework for narrating the research of Dorothea

Bleek, I follow its use by Hugh Raffles (2002:325–5) as a means of expressing

‘the broad and encompassing field of affective sociality’ in which field-based

research is carried out. Dorothea Bleek did not appear to be intimidated by the

grand and much publicised rock art and archaeological expeditions in southern

Africa, which had been carried out a few years earlier by Leo Frobenius (Pager

1962:39–45), the Abbe Breuil and others. In terms of resources and output, her

project was tiny.3 In regard to their affiliations, the prehistorians circulated

securely within the accepted institutions of formal science and the academy. As

well as drawing on the informal assistance of their spouses, these male scientists

could call on state or institutional support (Shepherd 2002; Schlanger 2003;

Dubow 2003). Bleek, on the other hand, occupied a peripheral position in relation

to the work of prehistory (perhaps partly because her primary interest lay in the

study of languages), as well as to the academy. Her position as ‘honorary

reader’ of ‘bushman’ languages at the University of Cape Town (UCT) did not

include financial support.4 Her correspondence suggests that she felt that the uni-

versity considered her ‘bushman research’ to be marginal and that it therefore had

to proceed on a ‘voluntary’ basis.5 Bleek’s membership of the South African

Association for the Advancement of Science was clearly important to her, and a

source of intellectual stimulation throughout her life. Despite these institutional

404 African Studies, 68:3, December 2009

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

connections, though, her research and field trips were self-funded. I suggest that

Dorothea Bleek’s research proceeded (by her own choice) at an intimate,

private pace within the larger public and institutional context of knowledge

production within which she situated herself. For her, this was intentional, as

scale was not the issue. In keeping with all of her work, it was more a question

of family tradition and loyalty, and of salvaging samples of rock art, language

and other aspects of ‘bushman’ culture, than about making grand statements of

scientific theory. Drawing on personal networks as opposed to institutional

support, her project may be framed as a highly personal and intimate journey

motivated through familial loyalty to her father, and to her Aunt Lucy who had

taught her so much.

By the 1930s, Dorothea Bleek’s preference for working with women in the field

was well established. Her first forays into the field took place from 1905 to

1907 while she was employed at Rocklands Girls’ High at Cradock, when

Bleek ventured into the field with fellow teacher Helen Tongue. The young

women visited and copied rock paintings at sites in the Orange River Colony

and Basutoland, as well as engravings in the vicinity of the Little Karoo village

of Luckhoff (Tongue 1909). Next, the Cape Times journalist Olga Racster went

with Bleek to the Northern Cape in 1911 (Bank 2006b). Later, Maria Wilman

joined Bleek in Upington and they travelled to the Kalahari. On another occasion,

in 1913, Bleek travelled to Kakia in Botswana with a friend named Margarethe

Vollmer. On her six-month trip through Angola in 1925, Bleek travelled with

the botanist Mary Pocock. This pattern of working with female research assistants

should be seen in the context of Dorothea Bleek’s family history (Bank 2006a).

She grew up in a family of women, her father having died when she was two

years old. From her childhood years in Mowbray to her schooling in Berlin,

Bleek’s home consisted of her mother and four sisters. She attended lectures at

the School of Oriental Studies in Berlin, and at the School of Oriental and

African Studies in London. Apart from these, her major intellectual influence

was her Aunt Lucy Lloyd, who schooled her in the /Xam and !Kung languages

and mentored her in methods of recording and translating. Moreover, Aunt

Lucy passed on the precious folklore and language notebooks, as well as the

rock art copies she had purchased from George Stow’s widow, all of which

Dorothea Bleek worked on for the rest of her life. In her preface to Specimens

of Bushman Folklore, Lloyd (Bleek and Lloyd 1911:xvi) credited her niece

‘Doris’ Bleek ‘for her invaluable help in copying many of the manuscripts and

making the Index to this volume’. Her sister, Edith, was also given a mention

‘for much kind assistance’.

Field Dynamics

This study draws on the growing body of scholarship dealing with the field

sciences, which has engaged with the dynamics of ‘the field’ as complex site

and context of knowledge production in particular disciplines. In her investigation

Sisters at the Rockface 405

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

of the Rhodes Livingstone Institute and the emergence and practice of anthropol-

ogy in central Africa during the middle decades of the twentieth century, for

instance, Lyn Schumaker (2001:6) marks ‘the field’ as a constructed and nego-

tiated space for the production of knowledge rather than mere source of data.

Schumaker’s intention is to ‘tell the history of anthropology with the field as

the central context’, and to understand ‘what is African about anthropology in

Africa’. She argues that surrounding social and official networks as well as

relationships between researchers and assistants give rise to a particular culture

of research and coproduction of knowledge, which has implications for the way

in which scientific knowledge emerges in academic or public contexts (Schumaker

2001:227). Other writers have revealed the extent to which the personal and

experiential contribute to the making of scientific knowledge by offering case his-

tories of early explorer-collectors. In the field of ornithology as it emerged during

the first half of the twentieth century, Nancy Jacobs (2006:564–603) has described

the encounters in West Africa of two ornithologists Reginald Ernest Moreau and

George Latimer Bates, and the series of colonised field assistants each of them

employed at various times. In both cases, Jacobs argues, the personalities of the

researcher and his assistants, as well as the broader colonial contexts in which

they operated, influenced both the scope and nature of their work, and the

public presentation of their findings.

In the natural sciences more broadly, both Jane Camerini (1996) and Patrick

Harries (2000) have documented the activities of two early naturalists, each

working in specific and widely differing contexts with respect to the overarching

systems of thought and formalising disciplinary environments in which they cir-

culated. Both Camerini’s and Harries’s investigations clearly elucidate the

nature of fieldwork as a complex practical activity which relied on social, familial

and financial networks of support. In her investigation of the Victorian naturalist

Alfred Russell Wallace, Camerini describes the ‘collective nature’ of scientific

work as well as the administrative links and social networks which were essential

to making work in the field possible. Camerini argues that the human relationships

developed and maintained during Wallace’s fieldwork remained an inextricable

component of the scientific outcomes (specimens collected and papers written)

he produced. For Wallace, ‘affects such as trust and respect played a pervasive

. . . role in the interactions that comprised fieldwork’ (Camerini 1996:46). Wal-

lace’s positive relationship with his longstanding Malaysian field assistant, Ali

Wallace, was a crucial component in his success as a naturalist. The development

of positive human networks in the field was similarly a crucial component in the

work of the missionary-turned-naturalist-and-ethnographer Henri-Alexandre

Junod. Patrick Harries (2000:30–1) has described how Junod’s ‘experience in

the domains of entomology and botany’ led him to structure his research into

human societies along the lines of field-based natural science methodologies.

This required the ‘co-operation of two different agencies’, one who ‘collects the

materials’, and the other who ‘work[s] them out’. Thus, Junod built relationships

406 African Studies, 68:3, December 2009

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

with a series of ‘native’ assistants and ‘locally knowledgeable people’, which

enhanced his respect for local knowledge. It is just this unstated, but nevertheless

crucial role of feelings and affectivities that I hope to tease out in the case study I

present below.

Turning to South Africa, recent scholarship has pointed to the importance of the

personal in field research as it emerged in the early years of the twentieth

century, and also to the tendency to elide the contribution of field assistants in

the textual productions arising from collaborative fieldwork. Working in Pondo-

land in the early decades of the twentieth century, the young Monica Hunter

(later Wilson) relied on networks established through close family connections

in order to negotiate and traverse her field site in a fairly remote rural landscape.

As Andrew Bank (2008) argues, the ‘inside’ story of these informal and ambigu-

ous social networks was written out of Hunter’s published texts, but is mentioned

in ‘private’ contexts such as personal correspondence. In his study of archaeology

through the work of AJH Goodwin, Nick Shepherd (2003a) has commented on the

regular elision of the presence of assistants in early fieldwork where their critical

contribution and spadework was rarely acknowledged for its part in the scientific

knowledge produced. In the case under discussion here, on the other hand,

Dorothea Bleek afforded an unusual level of equality to her research assistants,

allowing them to be named as the primary authors of the book, which later

emerged from their collaborative efforts. But not only were the Van der Riet

sisters recognised as authors in the book. As this case study will show, their

creativity and inventiveness at the rock face was relied upon by Dorothea

Bleek, who appeared to welcome their ability to invent methods as they went

along on the daily research programme. Indeed this close level of collaboration

speaks of a rare level of equality between researcher and supervisor, one that

perhaps arose from the intimacy which pertained between Bleek and the young

women.

The self-reflexive turn in the human sciences has resulted in a great deal of sensi-

tive attention being paid to aspects such as the coproduction of knowledge, and to

the unstable and negotiated ways in which knowledge emerges from the field. In

this context the practice of rock art reproduction has, with some notable excep-

tions, been presented as an unquestioned mode of scientific documentation.

Pippa Skotnes (1996:236) has argued that the ‘simple technology’ of acetate

tracing ‘replaces the originals with linear, stylistically arbitrary, monochrome

copies, and has absolved the researcher of the need to address the iconographic

diversity and stylistic variety that exists in the paintings’. The translation of pic-

torial form into diagram is a process that renders ‘all paintings equal, stylistically

similar [and] visually bland’.6 Its deployment as representation for use in the

interpretation and elucidation of theories related to rock paintings, their authorship

and meaning, is often accepted without question. It is this unquestioned accep-

tance of rock art copying as seamless scientific method that the narrative presented

here hopes to dislodge.

Sisters at the Rockface 407

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

Rock Art Research

Before proceeding with a detailed narrative of Dorothea Bleek’s 1932 project, it is

necessary to sketch a brief chronology of rock art research in Southern Africa as it

developed gradually into a formal field of study during the opening decades of the

twentieth century. Generally, rock art research in South Africa tends to present its

public past in terms of an heroic story of search and salvage stretching from Joseph

Orpen and his ‘bushman’ guide Qing, through George Stow to David Lewis

Williams and the cognitive archaeology theories of the 1980s.7 Wilhelm Bleek

and the Bleek-Lloyd ethnographic texts provide a celebrated interpretative

context for the story, but Dorothea Bleek’s contribution is left out of the canon.

However, the specific genealogy of rock art documentation in the decades

immediately before and after the turn of the twentieth century is a more haphazard

story as Patricia Vinnicombe (1976:116–25) has shown in her detailed review of

the history of rock art copying in the southern Drakensberg between 1870 and

1910. Initially, this comprised the efforts of hobby collectors, among them

missionaries such as the Trappist monks Father B Huss and Brother Otto

(1925), who copied paintings in Southern Natal and later near the Kei River,

and F Christol of the French Protestant Mission at Hermon, who documented

the rock art of Southern Basutoland (now Lesotho). Also in the field were military

or police personnel, and state employees, of which the four-month trip of the

policeman Whyte is probably the most notable example (Vinnicombe

1976:123). Some collectors took it upon themselves to contribute reproductions

to institutions around the country, including the South African Museum, or to

state authorities such as the Ministry of the Interior. In some cases, painted

slabs deemed vulnerable or especially noteworthy, were chopped or blasted

from their sites and transported by road or rail to metropolitan centres.8

Accompanying this collecting activity was the growing realisation of threats to the

paintings, and the beginnings of state action to protect them (Vinnicombe

1976:120–2). Steps were taken to protect ‘bushman’ paintings from decay and

destruction and parliament published a list of sites in the Cape colony in June

and July of 1906. In Natal, action was channelled through local magistrates,

and recommendations included the erection of prohibitive notices. State control

and protection of rock paintings was eventually promulgated in the Bushman

Relics Protection Act of 1911, with further legislation enacted in 1923, 1934

and 1937. The informal collecting of rock art copies grew more professionalised

during the 1920s. Archaeologists such as Miles Burkitt and AJH Goodwin slowly

began to formalise the field (Shepherd 2002, 2003b; Schlanger 2003; Dubow

2003). For these early archaeologists, the presence of rock art was seen in relation

to the dating and categorising of the stone tools found in such abundance across

the country, occasionally but not always in direct proximity with painted sites.

The celebrity visits of the Abbe Breuil, Miles Burkitt and Leo Frobenius in the

late 1920s began to focus attention on rock art as being worthy of study in its

own right.

408 African Studies, 68:3, December 2009

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

But apart from Dorothea Bleek’s contribution, several decades would pass before

a serious attempt was made in rock art studies to address the problem of selectiv-

ity, and attend to the task of systematically documenting every single painting

within a defined region. It was not until the 1970s that Patricia Vinnicombe

(1976) published the results of her fieldwork (carried out during the 1950s),

which aimed at making a ‘thorough survey’ of a specified area, ‘to record all

the paintings within it, avoiding any element of personal preference or selection’.

Vinnicombe (1976:124–7) undertook to ‘plot the sites as accurately as possible on

available maps, and to record every recognisable painting by both tracing and

photography’. Whatever her aspirations, Vinnicombe’s field experiences clearly

demarcated the limits of empiricism that she encountered.9 Similarly, AR

Wilcox’s (1956:45) attempt to offer a methodologically defined and systematic

study of rock art argued that the subjectivity and emotional reaction of the

viewer remained one of the greatest obstacles to the scientific study of rock art.

Thus the generalised history of rock art research aspired initially to narrate itself in

scientific terms, relying for authority and credibility on the methods of high

science including the assumption of systematic and exhaustive sampling, accurate

measuring, and recourse to laboratory processes such as carbon-dating (Dowson

and Lewis-Williams 1994). In line with this emphasis on accuracy, the efforts

of early copyists such as Dorothea Bleek and George Stow were subjected to

scrutiny and found to be lacking. Contemporary scholars have dismissed their

recording efforts on the grounds of ‘selective’ or ‘eclectic’ sampling methods

and/or inaccurate tracing or copying methods (Lewis-Williams1981:15–6;

Dowson et al. 1994). In this context, a human story involving the heat, dust,

intimacy and unpredictability of the field struggled to find purchase.

Engaging Assistants

In February of 1932, Dorothea began making arrangements for the Grahamstown-

based Van der Riet sisters to try their hand at copying rock art from caves and shel-

ters in the country surrounding their home. Mollie and Joyce were the nieces of

Miss van der Riet, a friend of Dorothea Bleek’s. She would later identify them

as daughters of the ‘late Judge van der Riet’.10 Their family home, Altadore,

was in Grahamstown.11 It is likely that the two were twin sisters, most probably

schooled at Diocesan School for Girls, to this day a private school in Grahams-

town for girls from elite families.12 The fact that the sisters were studying art at

the Grahamstown art college made them ideal candidates as research assistants

(Van der Riet and Bleek 1940:xix).13 The sisters were usefully located in the

heart of Dorothea Bleek’s geographical area of interest. She would pay them

from the proceeds she derived from the sale of her earlier book, Rock-Paintings

in South Africa (Van der Riet and Bleek 1940:xix).

By this time, the excitement around Southern Africa as laboratory for prehistory

was shifting. Interest was beginning to focus on East Africa as a more interesting

Sisters at the Rockface 409

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

region for research (Shepherd 2003b:37). In the wider world, global politics had

begun to influence affairs even in cities far from the metropolitan centres of

Europe and the United States. But Dorothea Bleek was not deterred. Her aim was

to document rock art located in the hitherto overlooked swathe of country stretching

from Piquetberg in the west of the Cape Province, through Paarl, Ceres, Worcester,

Swellendam and Riversdale, to the mountains around Oudtshoorn, George and

Uniondale, as well as those in the country further to the east around the Bedford,

Albany and Graaff Reinet districts (Van der Riet and Bleek 1940:ii–xix).14 In

the space of three months, Bleek’s researchers produced 138 copies of rock art

paintings and covered miles of country stretching from Grahamstown to the area

we now know as the Garden Route. The rock art copies they collected allowed

Dorothea Bleek to present a more geographically complete survey of rock art in

the presidential address she was to deliver later that year (Bleek 1932).15

The thrust of Dorothea Bleek’s interpretations and theses around rock art were spelt

out in her 1932 lecture and affirmed in her introduction to More Rock Paintings in

1940. In terms of interpretation and meaning, she reiterated her view that the paint-

ings reflected daily life, cultural activities, and historical events (respectively

hunting, dancing and masquerade, cattle raids and battles). She conceded that

some paintings, especially group scenes, might be myth illustration, but only very

few conveyed ‘magic purpose’. The impression that most of the paintings conveyed

magic or ritual, she argued, was based on a false impression created by the copyist

who would tend to select the more interesting scenes to reproduce, over and above

those showing scenes of daily life (Van der Riet and Bleek 1940:xiii–xiv).

Bleek’s view was that the paintings were the work of ‘bushmen’, perhaps distin-

guished into different language groups, but all ‘bushmen’ who had inhabited the

country before the arrival of white settlers from the south, and other groups from

the north. She cited early travellers such as Barrow, Sparrman, Lichtenstein as her

sources. She referred to archaeological evidence to support her arguments around

authorship and date of paintings in the different areas, and in addition drew on cul-

tural embellishments depicted in some paintings, such as bow and arrow, kaross,

ostrich beads, and her own observations of ‘bushmen’ in the field. Here, Bleek

(1932) based her argument on empirical knowledge gleaned from her own rock

art fieldwork carried out during 1928, when she personally attempted to find

and check as many of Stow’s sites as possible. Where ‘Bantu’ spears appeared,

along with cattle and horses, she argued that this evidence that the ‘Bantu invasion

was beginning’ meant the most recent paintings could be dated to the second

half of the eighteenth century, ‘shortly before the Bushmen were detribalised or

exterminated’ (Van der Riet and Bleek:xvi).

Science in Practice

In the field, Bleek insisted that scientific practice be employed. She made sure that

copies were vetted by Dr John Hewitt, director of the Albany Museum. Within the

410 African Studies, 68:3, December 2009

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

matrix of the intimate, marginal and local sketched above, Hewitt may be seen as

the affirming figure of formal (institutional) science. He had been director of the

Albany Museum for at least ten years by the time Joyce van der Riet, following

Dorothea Bleek’s written instruction, called on him to find out more about the

rock art of the district.16 Hewitt (1920, 1921, 1925)’s main interest lay in the

human and cultural aspects of the prehistory of the Eastern Cape region.

He would certainly have been well known to Bleek through Association meetings,

which they both attended. Hewitt expressed his support for the project, declaring

that none of the ‘bushman’ paintings in the Albany district had yet been ‘properly

painted’.17 He singled out the ‘Wilton series’ of the district as being especially

worthy of copying.18

Joyce van der Riet provided precise details regarding the research methods

employed. ‘We actually traced the drawings off the rock and then painted them

on the spot so that they are as exactly alike the originals as it is possible to

make them,’ she wrote.19 In citing this description of methodology in connection

with her 1938 funding application to the National Research Council and Board for

support to publish the paintings, Dorothea Bleek would later write that she

‘impressed’ on her research assistants that she ‘did not want pretty pictures, but

accurate copies’.20 She also directed the sisters to tint the background of their

copies to represent the colour of the rock surface, rather than leave it blank.21

They were, where possible, to make pen and ink drawings of the sites, and take

photographs, or ‘snaps’ as Joyce called them in her letters.22

Without recourse to Bleek’s letters, I am left to speculate about her response to the

obvious enthusiasm with which her assistants embraced their task. So energetic

were they that by the middle of May both sisters had worn out their shoes and

run out of paper and paints, and needed to return home for replacements. Joyce

had to resort to letter writing in pencil, having run out of ink with no possible

way of refilling her pen.23 Bleek must surely have realised just how much the

Van der Riet sisters’ wholehearted enthusiasm contributed to the success of her

project. For the young women assistants, however, it was as much about adventure

as preserving a threatened culture. Clearly, the project was worth Mollie and

Joyce’s while financially, but more so, it spoke to their independent and adventur-

ous spirits – a fact that contributed substantially to the detail and quality of the

data they produced.

Negotiating the Field

The correspondence rather than the published book communicates the charm and

texture of negotiations that passed back and forth between the assistants and their

supervisor as the project got underway. Joyce’s letters overflow with excitement.

But although she and her sister were ready and able to traverse the country by car,

and to stomp miles through rough country armed with all the paraphernalia

required for tracing and copying, they were more reticent when it came to

Sisters at the Rockface 411

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

putting a price on their efforts. In her introductory letter, Joyce left the matter of

payment entirely up to Dorothea, asking only to be paid ‘so much a mile for the car

and then so much for each set of paintings according to the amount of work in

them’.24 A pencilled note on Joyce’s first letter indicates that Dorothea offered

to pay the sisters ‘£1 per sheet (more for difficult ones), 4s per mile, £2 for

sketch of cave painting, 5/- for photo’.25 Her offer was accepted, and Joyce

declared that both she and her sister were ‘only too willing to finish [the paintings]

round Grahamstown’, and were very keen on travelling further afield later on.26

At this early stage of the project, the sisters were discovering just how many

rock art sites existed close to their home. Through Hewitt they had been told

about sites at Alice, as well as other sites ‘only five or six miles out of town’.

But Dorothea Bleek had a clear idea which sites she wanted recorded, and

excluded the ‘extraordinarily good’ but too ‘well known’ examples of cave paint-

ings near Cala in the then Transkei which Joyce’s brother had told her about.27

This site was very likely the same as the one visited by Helen Tongue some

twenty years earlier (Tongue 1909:23).

Braving what could very likely have been a blazing hot Eastern Cape day in late

February, Joyce and Mollie travelled some seventeen miles to Broxley, the farm

owned by Mr J Currie, for their first research encounter. Once there, they

walked, climbed and scrambled the necessary distance over rough territory to

reach their target, a shelter situated some ‘5,000 feet above the New Year River’,

where they made their first set of copies.28 Hewitt vetted the paintings produced

at Broxley, corroborating these as work of ‘great fidelity’ and better than his

own.29 Thus was produced the first set of four sheets which were duly posted to

Cape Town. Joyce and Mollie earned £4.11.10 for their first copying efforts.

It seems that Dorothea Bleek regarded the sisters as equal partners in the process

of knowledge-making. No distance in terms of race, culture or gender existed to

muddy their interactions. Neither did the generation gap seem to affect their

working relationship. My sense is that Bleek was grateful to exploit the sisters’

youthful energies. Their apparent lack of knowledge and experience about rock

art did not seem to bother her at all. The correspondence shows that the young

researchers inscribed themselves into Bleek’s project in many ways. Joyce’s

letters are shot through with comments and questions which reveal the extent to

which the sisters were involved in selecting, influencing and making judgements

about the material they were representing. Through the flow of letters, nego-

tiations around methodology were ongoing, with questions related to field practice

a common theme. Early on, Joyce realised that capturing the total number of paint-

ings in some shelters was impossible. At Glencraig, for example, there were

several caves and many paintings: ‘. . . it seemed impossible to paint every one

so we left out the obviously later ones which were much inferior and even

looked as if they had been done in the last few years by the natives living on

the farm at present’.30 Here, Joyce asked outright: ‘Is this correct or do you

want a record of every distinct painting that it is possible to do?’31 Later in the

412 African Studies, 68:3, December 2009

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

same letter is revealed a moment where the researcher’s sense of the aesthetic

influenced the research: ‘Some of the pages are not as full as they might be but

we felt that often to add an odd painting would spoil the group . . .’ Then there

was the problem of representation: ‘Do you want the paintings exactly as they

are at the present day because some are so very weather worn that wouldn’t it

be better to improve them a little in colour I mean not form?’32

In the absence of Bleek’s replies, I am left without direct answers to Joyce’s

questions, but it would be safe to assume that an exact replication of the original,

faded colours notwithstanding, was exactly what Dorothea Bleek required.

However, the negotiated, interactive texture of fieldwork is clearly revealed in

the preceding exchange, and it shows that the flow of knowledge proceeded in

both directions. As much as Bleek’s expertise was sought, at certain times

Joyce’s letters revealed the extent to which the assistants weighed in with their

own interpretations related to the geographical location and siting of the rock

shelters and caves they visited. Just a month into the trip, Joyce noted that all

‘of the paintings we have done so far have been on the side of streams; that

seemed essential to the Bushmen’.33 At Glencraig, the sisters would later specu-

late that since the shelter could be easily seen from a distance, it meant that the

artist did not fear unexpected attack.34

During the coming weeks, the sisters’ dependence on informal, local or intimate

knowledge was to become another feature of their research. Throughout the

project, in each farm, town or district they visited, they would approach farmers

and townspeople and ask for information about rock art sites. In some cases, con-

nections were passed on by Dorothea Bleek, in others, contacts were initiated by

the fieldworkers themselves. This method of involving local networks in their

research had its pitfalls as well as its positive outcomes. Four weeks into the

project, Joyce remarked how their inquiries elicited either too much information,

or information that was too vague or contradictory to be of any use. As a result, she

complained, they either missed visiting particular sites, or they were ‘sent on wild

goose chases all over the veldt’ [sic].35 From the farm Doorn River near George,

Joyce reported being surprised by how little the farmers ‘know of their own

caves’.36 A month later, at ‘New Bethesda’ [sic], the sisters again confronted a

gap in local knowledge. From this village, which Joyce described as ‘a small

town thirty odd miles North West of Graaff Reinet’, three of the farmers she con-

tacted (from a list of four farms) had no knowledge of paintings on their farms.37

Joyce’s letter explained that the sisters had turned down invitations to search for

the paintings because they had heard that ‘many of the paintings in the district had

been used for target shooting’.38

They had better success at the fourth farm Africander’s Kloof, where the paintings

were ‘numerous’ and ‘seemed superior’. Time constraints prevented the sisters

from extending their search, but they took from the region a list of sites that,

Joyce wrote, ‘the garage man gave me the day we left’.39 Details such as this

Sisters at the Rockface 413

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

one, revealed in Joyce’s animated and chatty letters, evoke a sense of the wide

scope of interest the project generated in the small villages through which the

sisters travelled, and the extent to which ordinary people became involved in its

progress. On several occasions, landowners shared their knowledge related to

the location and meaning of rock paintings sited on their lands. At Mountain

Top farm twenty-seven miles north west of Grahamstown, Joyce commented on

the presence of ‘sheep which Mr Bowker [the farmer] says is an old Cape

sheep now hardly seen in South Africa’. She also saw handprints at this site

with the ‘black figures’ underlying these being judged the oldest paintings in

the shelter.40 Joyce’s sketch of the shelter later appeared in More Rock Paintings,

as did her copy of a group painting.41 Bleek (Van der Riet and Bleek 1940:Notes

to Plate 7) thought the group scene represented myth illustration involving

raindrops, a rainbow, a pool of water [tasselled bag], and a hare. The hare was

a common feature in the folklore of ‘every bushman tribe from whom folklore

has been collected to any considerable extent’ she would comment later, in an

obvious reference to the work of her father and aunt.

For the sisters at the rock face, the correspondence makes dramatically clear that

nature loomed large at times, though discussion of its vagaries rarely formed part

of the sanitised texts and images that eventually became available for public

consumption. Without Joyce’s regular and detailed letters from the field, I

would not know that the sisters fought off ticks, fleas and ants as well as the

intense late-summer heat on two visits to a site at ‘Howiespoort’, seven miles

outside of Grahamstown, where they produced four sheets of copies.42 Neither

would I realise that the extremely hot weather constrained their work at times.

Joyce wrote in mid-April that the ‘frightfully hot’ weather had been a ‘decided

handicap’ to the smooth and speedy progress of their work. At Katbosch, they

had to contend with ‘pouring rain’ and ‘frightful cold’.43 Intimate details such

as these give a picture of the contingent, stumbling progress of the fieldwork,

and demonstrate as well the embodied physical engagement and personal commit-

ment demanded from the fieldworkers.

In late April, Joyce and Mollie travelled south west of Grahamstown to Coldspring

(fourteen miles roundtrip), where they copied rock art sited alongside a stream, and

took photographs of the valley.44 Guided by Mr Hewitt, the sisters next made two

trips to ‘Salem commonage’ and braved the discomfit of the sun blazing down on

them as they worked.45 The resulting copies proved worth the effort. In early May,

Joyce despatched the eight sheets produced at Salem, among these a copy featur-

ing a ring of figures with a bigger figure in the centre, which Joyce described as an

attempt at composition ‘seldom aimed at in their work’.46 Bleek (Van der Riet and

Bleek 1940) would, after Stow, describe this as a ‘circular dance’ featuring women

dancing around a male leader in the centre.47

The pace of research had stepped up considerably by late May. Mollie and

Joyce worked hard every day, and exploited every opportunity to visit sites.

414 African Studies, 68:3, December 2009

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

The paintings at ‘Hell Poort’ near the Cradock road, for instance, were recorded

during a picnic stopover at the site on their way home from a farm dance the

previous night.48 Late in May, Joyce remarked with satisfaction: ‘Everyone

here is surprised at the amount we managed to get done but then we worked every-

day & very hard so really it is not to be wondered at at all.’49 On 30 May, Joyce

acknowledged receipt of a handsome £61 received from Bleek in return for 34

sheets dispatched previously. Ten days later, they received a further £15 in

return for another ‘roll’, which Joyce had posted off earlier. Certainly, the work

was bringing financial reward, but there was more to it than money. As they

themselves acknowledged, Joyce and Mollie were ‘becoming very interested

in the bushmen & their paintings’.50 There is evidence that the project also

brought experiential reward. At Boesman’s Kloof (see Pic C16.54.4),

we see a moment where the fieldworkers were deeply touched by the fieldwork,

as Joyce reported how she and her sister watched in wonder while previously

hidden paintings emerged as the afternoon sun lit a cave’s interior.51

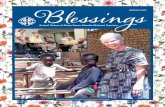

C16.54.4: Copying rock art at Boesman’s Kloof, Oudtshoorn. The inscription on the backof this photograph, found among Dorothea Bleek’s correspondence, records that it wastaken at Boesman’s Kloof, Oudtshoorn. The subject of the photograph is not named.Source: Courtesy of UCT Libraries, Manuscripts and Archives Department, C16.54.4, BC151.

Sisters at the Rockface 415

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

Chronology

Reading the letters chronologically as I have done gives a clear sense of how the

sisters gained in confidence as they traversed their ‘field’ through time and space.

I track their deepening involvement in the work, and their growing confidence

in their ability to ‘know’ the object of their study. At Misgund (see Pic C16.54.12),

where they stopped in mid-May for instance, Joyce had the confidence to proclaim

the paintings ‘quite different from any we have done before’.52 The ‘large figure,

which was about two feet high’ was both ‘indifferently drawn’ and ‘out of reach’.

They decided to photograph the figure for Dorothea so that she could decide if she

wanted a copy of it or not.53 The sisters also copied as well as photographed a

bichrome elephant at Misgund, both of which appeared in the book.54 A couple

of weeks later, while on the lookout for engravings near Graaff Reinet, they

came across paintings that Joyce described as ‘very poor’. The shelters, which

were ‘filled with spots & crude scribblings’ were situated on the farms Door-

nplaats (Doorn Plaatz in the book), Katbosch and de Erf, which Joyce described

as ‘twenty four miles South West of Graaff Reinet’.55 Two painted copies and

one photograph from this series appeared in the book.56 It was on this segment

of the trip that their settled field practice was challenged by the more complex

techniques required to record rock engravings (as opposed to paintings). At Steilk-

rantz, it was in response to a request from Bleek’s friend and colleague Maria

Wilman that the sisters in ‘great hopes’ walked miles to find rock chippings

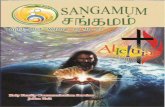

C16.54.12: Mollie van der Riet copying paintings at Misgund. This image, along withseveral ‘snaps’ of painted rock art, is filed among Dorothea Bleek’s letters to the Van derRiet sisters. The caption inscribed on its reverse records the following: Mollie van derRiet at work at Misgund about six foot above ground level, Long Kloof Gorge. Source:Courtesy of UCT Libraries, Manuscripts and Archives Department, C16.54.12, BC151

416 African Studies, 68:3, December 2009

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

which Joyce described as disappointing, but which Dorothea evidently felt were

worthwhile, as she included three in the book.57

After so many weeks and several repeat visits in particular areas, it is not surpris-

ing that the sisters were becoming regarded as local experts in the field of

‘bushman’ research. In one of her last letters, Joyce wrote that it would be easy

to continue gathering information for Bleek since people ‘seem to have heard

that we are interested & are always ready to tell us of new caves & anything

else they happen to know of the bushmen’.58 She thanked Dorothea sincerely

for the opportunity of doing the copying work since ‘. . . besides the only too

needed money, we have enjoyed doing it all most awfully as well’.59 On 17

June, Joyce despatched another set of sheets to Dorothea.60 These were copies

from Wilton cave near Alicedale, site of a dig that Mr Hewitt had been involved

in, and which had been described by Goodwin and Van Riet Lowe (1929:252–3)

just a few years earlier.61

So the weeks of intensive research came to an end. Bleek travelled to Durban

to deliver her lecture to the Association meeting from 4 to 6 July. Mollie and

Joyce went to their provincial hockey tournament in Johannesburg in ‘excellent

training’ after so much ‘climbing & walking’.62 Three loose, undated sheets of

ruled writing paper lurking among the correspondence record Bleek’s painstak-

ing calculations in which she added up her expenses related to the project.

Including amounts of £3.10 for her niece Marjorie Bright and a further

£1.05, probably for Sheila Fort, Bleek in total spent £215.9.8.63 That consider-

able sum had bought her 150 copied paintings, 138 from the Van der Riet

sisters as well as additional copies from the Porterville and Piquetberg

mountains. After that effort and expense, I imagine Bleek would have stored

her substantial collection in a very safe place while she turned her attention

to other projects.

Packaging Field Notes

It was not until around 1938 that she returned to the rock art copies. A separately

filed collection of correspondence between Dorothea Bleek in Newlands and

Methuen in London attests to two full years of negotiations around the production

and publication of More Rock Paintings in South Africa.64 It was either late in

1937 or early in 1938 that Bleek (Van der Riet and Bleek1940:xx) entrusted her

UCT colleague AJH Goodwin to approach Methuen in London with her valuable

collection.65 The correspondence begins in the middle of things. The publishers

are looking for a more affordable way to fill the brief, originally estimated at

the ‘huge’ cost of £900.66 Eventually, after months of discussion, a suitable

schedule was agreed on. It was not until two days before Christmas of 1938

that Bleek signed the formal contract with Methuen. She returned her signed

version to London along with her own contribution of £200 towards the publishing

of the book. This was followed up with the National Research Foundation’s

Sisters at the Rockface 417

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

contribution of £395 sent on 31 December, and a request for bromide copies so

that she could, in collaboration with her research assistants, complete her text

for the book.67

It was not until late in 1940 that the book eventually saw the light of day. Yet just

as the published text elides the contingent moments of field research, so too does

the finished book gloss over the ruptures and uncontrollable moments underlying

processes of production and publishing. These are only apparent to readers of the

Bleek Collection where Dorothea Bleek’s preserved papers convey detailed infor-

mation regarding the laborious and haphazard process of packaging field notes for

publication. The available correspondence does not make clear who made the final

selection of copies for the book. Astonishingly, the implication is that the publish-

ers did this, perhaps working from an original list provided by Bleek.68 This was

likely because of the complexities (and cost) of full colour printing at the time that

directly affected which and how many colours and plates could be included in a

particular estimate. It is possible, given that he was in London at the start of the

process, that Mr Goodwin was consulted. Bleek appeared to have appointed

him as her envoy and may have entrusted him to deal with more than simply

delivering the copies.69

The correspondence file makes clear how, behind the scenes, Bleek liaised with

her researchers, wrote texts and captions, checked maps and photographs, num-

bered bromides, checked proofs, and dutifully posted these to London. She was

by now resigned to the reality of having to narrow her extensive collection of

150 sheets of copies down to 34 plates, and to the less than perfect sequencing

of sites due to confusion which had arisen around pagination, layout and

geographical spread of paintings. In her published introduction, Bleek (Van der

Riet and Bleek 1940) was careful to make readers aware of two levels of selection,

‘first in copying, then in publishing’, which underpinned the final outcome, and

consequently influenced the impression created by the paintings collected in the

book.

The typed letter she addressed to ‘Mrs Ginn and Miss Mollie van der Riet’ early in

January of 1939 implied the long period of negotiation which had stretched

throughout the previous year. It expressed regret that ‘not a third of the collection’

would be included in the book.70 In keeping with her desire to show representative

sampling, Bleek regretted not being able to include at least one example from each

site visited by the sisters. She herself would write the complete text for the two

examples from Piquetberg that she had visited.71 She would also supply the

explanatory ‘Remarks’ for all illustrations, but the sisters were asked to provide

the remaining text for all of their sites. Bleek was specific about the form this

text should take. Mollie and Joyce should be as definite as possible about farm

ownership.72 Bleek was particularly concerned to give readers a feeling for the

landscape, in both general and particular geo-physical detail, in which shelters

and paintings were located:

418 African Studies, 68:3, December 2009

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

I want a general description of the physical features of each district to precede the 1st

plate from that district. Then I want the Locality . . . Site . . . and Description . . . given,

as I have done. You need not fill up Remarks . . . unless you have something you

particularly want to say. I will fill in that part. Description . . . should tell of the

general work in the cave or shelter.73

By now, Joyce was married and living in Walmer, Port Elizabeth (PE), while

Mollie was employed by the Automobile Association in Grahamstown. Neverthe-

less they were happy to help and excited at the prospect of seeing their names in

print. Joyce would travel up from PE for a few days so they could work together,

and ‘Mummie’, who had travelled with the sisters on the initial trips to Oudtshoorn

and other local sites all those years back, was also brimming with suggestions.74 In

reality, though, it turned out that in recollecting trips taken and sites recorded

seven years previously, the sisters had only a diary and their memories to go

on. ‘I only wish we had known at the time that this was in store for us, because

we would have then taken careful notes,’ Joyce wrote.75 They tried to fill in

the gaps by asking farmers on whose farms they had painted to confirm their

‘statements’.76 They asked Bleek to return the letters Joyce had written. Over

two weekends, Joyce and Mollie retraced their steps in the countryside around

Grahamstown and beyond. They wrote to municipalities and farmers to confirm

land ownership.77 Mr Hewitt, presumably still at the Albany Museum, helped

where he could.78

The sisters rounded up as much information as possible, papering over gaps

and anomalies as they went along. The seamless text of the published book

gives no clue to the places where memory failed and/or nature had intervened.

The correspondence, however, tells us that despite extensive searching on three

different occasions, Mollie was unable to find a particular group of paintings

they had copied at Glencraig.79 The area had become overgrown over the years,

and Mollie remembered the group in question being ‘quite apart from the others

in a very small shelter on a slightly lower level’. But, she admitted, ‘I cannot

be sure as we did so many that I may be mixing it up’.80 Perhaps too, as Dr

Hewitt suggested, motorcars had made a difference, sending clouds of dust

across the valley to cover the rocks and hide the paintings.81 Based on what

appeared in the book, the particular group that Bleek was after may have shown

figures embellished with different bows. Bleek’s remarks relating to the only

Glencraig group published in the book made much of the depiction of ‘length

of the bow in relation to human figure’.82 In the end, Mollie was apologetic

about the ‘little help’ they had been able to provide. But she made excellent

use of the £10 Dorothea paid her for her share of the work, putting it towards

the requirements for her ‘A’ Pilot’s Licence in time to make use of a special

government grant. ‘So you see your £10 was indeed a fortune in more ways

than one,’ she wrote.83

While Mollie completed her pilots’ training, Bleek continued to work methodi-

cally on the book. She seemed oblivious to the gathering clouds of war in

Sisters at the Rockface 419

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

Europe. Her research consumed her completely. In between working on the book,

she continued to assemble rock art samples from around the country, in line with

her desire to ‘salvage’ work representing all regions. Sometime in May, she visited

rock art sites in the mountains of the Western Cape, at Bain’s Kloof and Gouda,

perhaps in the company of her niece Marjorie, and Sheila Fort: ‘[T]here are still

paintings, but much simpler ones, not at all as beautiful as those in the Freestate

[sic] and in the Eastern Cape. The ones here are mostly in one colour. But the style

is the same,’ she wrote to Kathe Woldmann.84 The same letter contained an

oblique reference to her project involving the Van der Riet sisters: ‘From the sur-

roundings of Grahamstown I have also received copies. Also these are somewhat

simpler as those from further east. I am trying to get samples from all parts of the

country in order to assess the differences and similarities.’85

Costs of War

Dorothea’s final book text and the corrected map reached London on 20 May

1939.86 Final queries seemed to drag on forever. In the end, the publishers

pushed the publication date out to 1940, and, on account of ‘war costs’ increased

the initially agreed to cover price of 2 guineas to 45 shillings.87 If Bleek found the

endless to-ing and fro-ing frustrating, she did not mention it in her private letters.

She would need patience and strength. There was a greater test in store.

It was in the early months of 1941 that the war, up to now refracted through delays

in correspondence and increased costs, had a direct and profound impact on the

archive of Dorothea Bleek. After some debate, Bleek had, in July of the previous

year, decided to have the paintings returned to Cape Town.88 The publishers, cen-

trally situated in the Strand of London, were still holding her valuable original

copies. These were insured against risk of fire but not against ‘enemy action’.89

With the Blitz in full swing, there was a real risk of air attack. But sending

them home by sea carried as much possibility of disaster. It was a tough call for

Bleek. She was in a quandary, and even while seeing to practical arrangements

such as cover for war risk, she uncharacteristically asked the publishers to

second guess her decision: ‘If . . . circumstances should make you think it wiser

to hold the pictures a bit longer, please do so’.90 The possibility of disaster was

at the front of her mind. Full insurance cover, even if expensive, would at least

provide cash: ‘. . . in the case of their being lost, I should like to be able to have

the rock paintings copied again’.91 Privately though, she must have known it

would not be that simple. She was well aware of the difficulties associated with

retracing sites.

By 15 August 1940 the reproductions, packed in a sturdy wooden ‘case’, were

on the water aboard the City of Simla.92 Now there was a break in correspondence

of about four months. When it resumed near the end of 1940, the war in Europe

was taking its toll on intercontinental communication services. Mail was slow

and irregular. Late in January of 1941 Bleek was still awaiting news of her case

420 African Studies, 68:3, December 2009

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

of paintings.93 Her letter of 21 January to the ship chandlers in Cape Town crossed

with that of Methuen dated 17 January in which was enclosed an insurance cheque

for £222.12.6.94 The City of Simla had, due to enemy action, been lost at sea with

all her cargo – including Bleek’s precious collection of rock art reproductions.95

As shattering as the loss must have been, Dorothea Bleek did not waste time

regretting her decision to have her reproductions returned to Cape Town. No

doubt she agreed with the publisher’s comment that ‘no part of the world

[seemed] very safe’ at the time.96 Archival documents show that she did not

falter in her continuing quest to document the rock art of the country. Catalogued

separately in the Bleek Collection is a file containing royalty statements from

Bleek’s two rock art books that Methuen sent regularly to Dorothea from 1931

until 1948.97 In this file lurks a letter from James Eddie.98 Dated 7 August, it

acknowledges the receipt of a total of £189.14.5 received ‘in connection with

copies made of Bushmen Paintings in the Western Province’.99 The letters

show that Bleek had immediately set about arranging to have as many of the paint-

ings recopied as possible.100 By mid-year, James Eddie, along with NM Rowley

and MF Hart, were copying rock art in the Oudtshoorn, George and Uniondale

areas.

Royalties

As the royalty statements individually numbered and preserved in the Bleek Col-

lection show, More Rock Paintings sold steadily throughout the remaining years

of Bleek’s life.101 Apart from providing material proof of her efforts to replace

her lost reproductions, this file bears witness to Bleek’s fastidious accounting

habits, and the scrupulous attention she paid to her regular earnings over nearly

twenty years from both of the books. It provides material evidence of her commit-

ment to honouring her funding agreements with the National Research Council

and Board. By mid-1945, Dorothea’s royalty earnings topped £200, and she

immediately dispatched a cheque to the Research Council enclosing £14.13.1 –

two thirds of the earnings above the £198 she had personally contributed to the

publication of the book.102

Bleek’s meticulous record-keeping habits were sustained right till the end of her

life. Three weeks before she died, she sent £10.2.4 to the Council for Educational,

Sociological and Humanistic Research.103 Her letter, dated 8 June 1948, was sent

from a new address, The Garth, Southfield Road, Plumstead.104 It acknowledged

the receipt of royalties of £15.13.-, earned in the six months from June to Decem-

ber of 1947, an amount which included the fee of 9s6d earned from the reproduc-

tion of ‘a portion of plate 7’105 by a Mrs Drinker in her book Music and Women

(1948). The last item classified in C18 – itemised as number 86, is an undated

‘compliments’ slip from Methuen, presumably originally attached to a cheque

and a more detailed statement of account. It refers to enclosed royalties of

£20.2.5. Scribbled towards the end of this slip of paper, in Dorothea’s handwriting

Sisters at the Rockface 421

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

and traditional use of black ink, is a breakdown of the amount into one-third and

two-third amounts. After that, the archive falls silent.

Conclusion

As the foregoing pages attest, I have allowed the logic of the archive to direct

my investigation of Dorothea Bleek’s rock art research and my reconstruction

of her project involving research assistants in particular. The foregoing narrative

describing the making of scientific knowledge in the field hinges on a reflexive

reading of personal correspondence as text. It reveals a sense of the intimacy

and closeness of the private letter, and of the local scale of its circulation

between the researcher and her assistants in the field. The flow of letters and

rock art copies between Dorothea Bleek and her field assistants bridges the

spatial and geographical distance between them, as well as structured the means

and pace by which knowledge was mutually negotiated in relation to this particu-

lar field. The public texts that emerged from this set of field encounters elide the

gritty realities that the young researchers experienced at the rockface.

My argument is that Dorothea Bleek’s work in general was less about the making

of scientific knowledge than an expression of familial loyalty to the intellectual

project begun by her father and aunt. In the foregoing narrative, I have paid

attention to the particulars of a fieldwork project, to the presence of research assist-

ants, and to the implications of these informal processes, practices and relation-

ships by and through which field-based scientific knowledge is made. My

intention has been to give local materiality and texture to arguments calling for

recognition of the unstable and negotiated ways in which scientific knowledge

emerged from research practices in the field sciences. By focusing on the

private, interactive details of the research relationship described above, I call

attention to the processes by which local, indigenous ways of knowing may

become intertwined in and recast as scientific fact. I have deployed notions of inti-

macy and marginality as a means of coming to grips with the intensely social,

embodied and relational ways in which a particular body of knowledge emerges

from the field. In Dorothea Bleek’s case, I suggest these processes were essential

to sustain and support her fieldwork and the production of knowledge from beyond

the (male dominated) academy. In the larger context, the private pace and intimate

scale of her research processes and networks may have contributed to the ‘mar-

ginal’ space which her research outputs appear to occupy in the genealogy of

South African rock art studies.

Notes

1. The Programme on the Study of the Humanities in Africa (PSHA)’s support of this research

article is hereby gratefully acknowledged. Sincere thanks are due to PSHA director Premesh

Lalu, PSHA fellows, and to colleagues and friends at the Centre for Humanities Research, for

intellectual support, stimulation and friendship, as well as to my PhD supervisor Andrew Bank

for reading and commenting on the many drafts of this article. I am grateful also to Lesley Hart

422 African Studies, 68:3, December 2009

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

T&

F In

tern

al U

sers

], [

kara

Kili

an]

at 0

3:21

26

July

201

1

and her team at Manuscripts and Archives Department of University of Cape Town Libraries

for providing a welcoming research space. I thank Hannelore van Rhyneveld for translating

Dorothea Bleek’s letters to Kathe Woldmann from their original German into English, and

the Iziko South African Museum’s Pre-colonial Collections Manager Petro Keene for arran-

ging my access to documents held there.

2. The narrative presented here is drawn mainly from the correspondence of Dorothea Bleek at

C16, C17 and C18 held in the Bleek Collection (BC151) at the Manuscripts and Archives

Department at the University of Cape Town, as well as from Dorothea Bleek’s letters to

Kathe Woldmann held in the Kathe Woldmann Papers (BC210, Box 4). Other correspondence

referred to is held at the South African Museum.

3. Leo Frobenius’s project produced at least 1,000 rock art reproductions, many of them on huge

canvases. His reproductions were not traced, but rather copied free hand. The Union govern-

ment reimbursed him for the reproductions he returned to South Africa at the time. Dorothea

Bleek did not approve of his copying methods and did not feel the reproductions were worth

what the state paid for them (see SAM incoming correspondence 1925–1936). Some of

Frobenius’s rock art reproduction work is held at the Frobenius Institute in Germany. The

Iziko South African Museum also holds a collection of his work, as does the University of

the Witwatersrand (Wits).

4. My use of the term ‘bushman’ is provisional. I use the word in quotation marks to signal an

awareness of the contested and shifting meanings which have accrued to the term, not least

through the work of early ethnographers and proto-anthropologists such as Dorothea Bleek

and others whose research has contributed to the construction of ‘bushman’ as formal

object and field of study within the human sciences as they became institutionalised within

the formalising academy of late colonial South Africa.

5. Bleek to Woldmann, 11 April 1927. In answer to Kathe Woldmann’s query in regard to finding

paid research work, Bleek wrote: ‘In terms of research, and in particular Bushman research,

this takes place on a voluntary basis. As for example my work. Only twice I was given assist-

ance for a few months for research trips.’

6. But see the work of Stephen Townley Basset (2001) for a representation of contemporary rock

art reproduction as an art form in its own right.

7. The heroic story features in many texts, and most publicly perhaps in the display at the Wits

Origins Centre where a display of South Africa’s pioneering rock art scholars includes Joseph

Orpen, Qing, Wilhelm Bleek, /Hankasso, David Lewis-Williams, and Patricia Vinnicombe

among others, but not Dorothea Bleek (based on author’s visit on 10 October 2008). A

similar narrative is presented in the Origins Centre documentary film, which is available for

viewing as part of the display on contemporary present representations of rock art. The

same documentary was screened on TV3, 6pm, 14 September 2008. A comprehensive view

of Stow’s copying work and practice was the subject of an exhibition at the Iziko South

African Museum, curated by Pippa Skotnes under the title ‘unconguerable spirit, George

Stow’s History Paintings of the San (see Skotnes, 2008).