Sealed Tablets from Hattuša

Transcript of Sealed Tablets from Hattuša

STUDIA MEDITERRANEA 23 ________________________

ARCHIVI,DEPOSITI,MAGAZZINIPRESSOGLIITTITINuovimaterialienuovericerche

ARCHIVES,DEPOTSANDSTOREHOUSESINTHEHITTITEWORLD

NewEvidenceandNewResearch

ProceedingsoftheWorkshopheldatPavia,June18,2009

AcuradiM.E.Balza,M.GiorgierieC.Mora

STUDIAMEDITERRANEAcollanafondatadaOnofrioCarruba

ARCHIVI,DEPOSITI,MAGAZZINIPRESSOGLIITTITINuovimaterialienuovericerche/

ARCHIVES,DEPOTSANDSTOREHOUSESINTHEHITTITEWORLDNewEvidenceandNewResearch

ProceedingsoftheWorkshopheldatPavia,June18,2009

AcuradiM.E.Balza,M.GiorgierieC.Mora

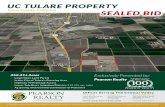

Cover:P.Neve,Büyükkale,dieBauwerke.Grabungen1954‐1966(BoHaXII),Berlin

1982,Pl.41GraphicDesign:LeonardoDavighi

PROPRIETÀLETTERARIARISERVATACopyrightmaggio2012ITALIANUNIVERSITYPRESS

ViaDante,2–PalazzoNuovaBorsa16121Genova

Tel.0382‐303878Fax0382‐303878

ISBN:978‐88‐8258‐139‐8

STUDIA MEDITERRANEA 23

ARCHIVI,DEPOSITI,MAGAZZINIPRESSOGLIITTITINuovimaterialienuovericerche

ARCHIVES,DEPOTSANDSTOREHOUSESINTHEHITTITEWORLD

NewEvidenceandNewResearch

ProceedingsoftheWorkshopheldatPavia,June18,2009

AcuradiM.E.Balza,M.GiorgierieC.Mora

ITALIAN UNIVERSITY PRESS

Sealed Tablets from Ḫattuša Maria Elena Balza, University of Limoges*

1. In 1906 Hugo Winckler and Theodor Makridi began extensive excavations on the mound near the Turkish village of Boğazköy. During these first archaeological campaigns (1906-1912), they found tablets on the west slope of the hill called Büyükkale that furnished the proof that the settlement under investigation was the center of the Hittite kingdom, the city of Ḫattuša.

Since the days of this great discovery, the excavations of Boğazköy have been carried out systematically, improving more and more our knowledge of Hittite cultural and political history.

This notwithstanding, many questions about the site remain open. The loss of much information about the original findspots of a large part of the texts, the distribution of thousands of the tablets amongst several buildings in the city and some other peculiarities make it difficult to figure out the nature of the tablet collections as well as the function of some of the buildings housing the texts.1 This topic represents a much debated and complex question that is connected to the larger problem of the comprehension of the workings of both the Hittite archival and administrative systems. For the time being, some

* This paper is part of a larger postdoctoral project on the conception of the

archival space among the Hittites that I carried out at the Freie Universität of Berlin within the framework of the Excellence Cluster 264 Topoi ‘The formation and transformation of space and knowledge in Ancient Civilizations’.

1 Observations and comments on the tablet findspots can be found in, among others: Güterbock 1940; id. 1942; id. 1991-92; Laroche 1949; Otten 1985; id. 1986; Cornil 1987; Košak 1995; Karasu 1996; Alaura 1998; ead. 2001; ead. 2004; van den Hout 2002; id. 2005; id. 2006; id. 2007; id. 2008; Klinger 2006; Torri 2008; ead. 2009.

Maria Elena Balza 78

possible solutions to this problem have been hypothesized, but a full reconstruction has not yet been achieved.2

This paper discusses, in particular, the problem of the almost complete lack of sealed tablets from Ḫattuša as well as the question of the distribution of the sealed texts in some of the city structures. First, the problem will be introduced focusing on its main features, and then the extant sealed tablets will be presented.

2. Thousands of tablets and fragments have been uncovered in the

excavations of Ḫattuša. A considerable number of texts come from the acropolis (buildings A, B, D, E, K), while other findspots are located in the Lower City (Temple 1 and the House on the Slope) as well as in the Upper City (Nişantepe complex and some city temples).3

Despite the large overall quantity of findings, only a few sealed texts – not very tantalizing and broken (Güterbock 1980: 53) – have been unearthed in the above-mentioned locations. This situation is quite surprising, especially considering the important role accorded, in some Hittite texts, to sealing practice and validation procedures. Let us consider, for instance, the words of the Great King Muwattalli II:

My father Muršili made a treaty tablet for Talmi-Šarruma king of Aleppo, but the tablet has been stolen. I, the Great King, have written another tablet [for him], have sealed it with my seal, and have given it to him. In the future no one shall alter a word of the text of this [tablet]. (Beckman 1999: 93).

Or the criminal charges presented at the trial against Ura-Tarḫunta, son of Ukkura:

(The charge is that) he regularly failed to indicate on a sealed tablet what was issued to whom. He also had no manifest (?) or receipt. (Hoffner 2002: 57).

Or the instructions to the commanders of the border garrisons:

2 On this problem see Imparati 1983; ead. 1999; Starke 1996; van den Hout

2002; id. 2005; id. 2006; id. 2008; Klengel 2003. 3 See the bibliography quoted above (n. 1).

Sealed Tablets from Ḫattuša

79

If, however, anyone brings a case (in the form of) a sealed wooden (or) clay tablets,4 the margrave must judge the case properly and make things right. (McMahon 1997: 224).

Or even the Hittite Laws: If a man who has a TUKUL-obligation disappears, and a man owing ILKU-services is assigned (in his place), the man owing ILKU-services shall say: “This is my TUKUL-obligation, and this other is my obligation for šaḫḫan services.” He shall secure for himself a sealed deed concerning the land of the man having a TUKUL-obligation, he shall both hold the TUKUL-obligation and perform the šaḫḫan-services (…) (Hoffner 1997: 48 [§ 40]).

Many other passages contained in the Hittite documentation refer to similar procedures, and in particular to the sealing of texts having a legal relevance as treaties, title deeds, and legal cases.5

It has been suggested that, within ancient near eastern societies,

the act of sealing a tablet was required “in order to authenticate it and to make it valid as an instrument of evidence” (Renger 1977: 79). In other words, on the one hand, the seal impressions, like the witness lists, played an important role in attesting the existence of a transaction or an agreement; on the other, they represent one of the instruments employed to allow the testimonial evidence and to prevent any forgery of the document.6

For these reasons, sealing a legal document had a primary importance. In fact, even though several copies of a tablet could be drawn up for archival purposes, only the original had to be sealed and

4 See however CHD, S, 16b: “But if someone brings a lawcase, (namely) a wood

tablet (taken) from a clay tablet, and sealed.” 5 On Hittite sealing practice see Güterbock 1939; id. 1980; Herbordt 2005: 25ff.;

Herbordt – Bawanypeck – Hawkins 2011: 26-30, 41; for the sealing of Hittite treaties and agreements see Wilhelm 1988: 362-364; Balza 2008 (especially Table 1 and 2) with references therein. A number of textual hints also refer to the sealing of wooden tablets. On this topic see, among others, Güterbock 1939; Symington 1991; Marazzi 1994; id. 2000; id. 2007; Herbordt 2005: 25ff.; Mora 2007: 540ff.

6 On this topic see, among others, Renger 1977; Cardascia 1995.

Maria Elena Balza 80

preserved in special locations: a private house, in the case of private transactions, or an official building, in the case of documents having an official relevance.

With regard to Ḫattuša, no private transactions, neither sealed nor unsealed, have so far been brought to light in the excavations. Therefore, the main question concerning this type of document is whether they were actually recorded, and on what kind of writing surfaces.

As for official legal documents from Ḫattuša, the situation is also quite unclear. While several copies and duplicates (= unsealed tablets) of official legal documents are distributed in some repositories around the city, only a very small number of verified (= sealed) copies have been found in the excavations. A large part of these documents is constituted by the so-called Land Grand Documents (LSU). Nevertheless, these texts will not be taken into consideration in the present survey since they represent a special text typology that should be better studied in connection with the analysis of the other archaeological items uncovered in the same findspots, namely sealed cretulae and clay lumps.7

If we exclude the LSU, only ten sealed tablets have so far been unearthed in the archaeological excavations in the Hittite capital city. This fact represents one of the most striking features of the Ḫattuša archives, especially if we compare that with the many tablets impressed with the seals of Hittite kings and high dignitaries that have been recovered in other sites under Hittite control during the 14th and 13th centuries BC.8 Furthermore, we have to consider that in Ḫattuša the paucity of sealed tablets goes hand in hand with the presence, in some local structures, of thousands of cretulae bearing the impressions of seals belonging to Hittite kings, princes and officials.

7 The association between LSU and sealed cretulae and clay lumps is attested in

the ‘Westbau’ of Nişantepe and in building D on the acropolis. Similar sealed cretulae and clay lumps have been discovered in the northern storehouses of Temple 1 and in some temples on the Upper City (Herbordt 2005: 19-21 with references therein). On this topic, see also the contribution of C. Mora in this volume.

8 Tablets sealed with the seals of Hittite kings and high officials have been recovered, for example, at Ugarit (see Schaeffer 1956) and Emar (see lastly Balza 2009: 77ff. with references therein). Cf. Herbordt 2005: 25-32; Herbordt – Bawanypeck – Hawkins 2011: 26-30, 41, with literature.

Sealed Tablets from Ḫattuša

81

The nature and function of the buildings housing these cretulae have not been fully understood yet. According to some scholars, they could have been the depots of containers of perishable goods belonging to prominent individuals or families and now no longer there. If this were the case, the containers would have been sealed in order to protect their content from any damage or violation. The contemporary presence of LSU in some of these depots seems then to suggest that they constituted some sort of ‘treasure rooms’, proper safe deposit rooms where title deeds and luxury goods were preserved together.9 According to another reconstruction, the findspots of the cretulae could represent ‘historical archives’ of previous economic transactions. In other words, they could represent the storerooms in which only the cretulae – separate from the boxes or containers to which they were originally applied – were preserved for administrative or account reasons.10

Among the different hypotheses, one in particular tries to explain the lack of sealed tablets by connecting it to the richness of sealed cretulae. According to this hypothesis, some kinds of original legal documents were inscribed on wooden writing boards and subsequently sealed by cretulae hanging from cords.11 If this were the case, the sealed cretulae unearthed in the so-called ‘Depotfund’ of building D on the acropolis, in the ‘Westbau’ of Nişantepe, in the northern storerooms of Temple 1 and in some other findspots in the capital city Ḫattuša would represent the remains of former official archives of wooden sealed tablets that have since disappeared. However, as some scholars have already noted, even though several passages in Hittite texts confirm the existence of wooden tablets,12 it seems that the use of this type of writing board was restricted to delivery notes, lists of goods stored in special warehouses, and texts drawn up for cultic purposes or employed during religious

9 On this hypothesis see Mora 2007: 544ff. with references therein. See also her

contribution in this volume. 10 See van den Hout 2007: 242 with literature. 11 On this hypothesis see in particular Güterbock 1939: 34; Bittel 1950; Marazzi

2000; Herbordt 2005: 32ff. The same practice would have been employed to seal the LSU. See among others Güterbock 1940: 47ff.; id. 1942: 4; Bittel 1950: 170 ff.; Marazzi 1994; id. 2000; id. 2007; Herbordt 2005: 26, 36, 111.

12 See Marazzi 1994; Waal 2011 with references therein.

Maria Elena Balza 82

ceremonies.13 It has been therefore suggested that the use of wooden tablets did not extend to legal documents intended to be preserved and to those having high legal status.14 In fact, both the perishable nature of wooden tablets and the ease with which they could be altered made these writing carriers, at least in some cases, less suitable than clay tablets. According to this suggestion, the reasons for the dearth of sealed tablets in Ḫattuša should be looked for elsewhere.

Recent reconstructions of the period preceding the collapse and the fire of Ḫattuša suggest that the inhabitants evacuated the city shortly before the final event.15 According to this hypothesis, when the Hittite court decided to leave the city, the scribes took with them the ‘state archives’ with the purpose of transferring them to a safer location.16 These archives most likely contained the documents that could preserve the memory of the state’s existence and its legal bases. Likewise, the members of the leading classes would have taken with them the legal documents attesting their high status, namely title deeds, testaments, adoption and marriage agreements and so forth.

If we accept this reconstruction, then we should look at the sealed tablets recovered at Ḫattuša as the remains of specialized archives of original sealed documents inscribed on clay and deliberately emptied by the Hittites.17 We should wonder now if it is possible, starting with the analysis of these few tablets, to put forward some hypotheses on the locations of the archives where the original legal documents were kept by the Hittite central administration.

3. Although the information provided by the sealed tablets from

Ḫattuša is too meager to be meaningful in itself, an in-depth survey could corroborate some existing hypotheses on the nature and function of the edifices in which the tablets were kept.

As we will see in more detail in what follows, sealed tablets have been unearthed on the acropolis,18 in or around buildings A and C,

13 See Mora 2007: 544ff. with literature; see also Waal 2011: 25-28, on references

to other kinds of documents inscribed on wooden tablets. 14 See van den Hout 2007: 341ff. with references therein. 15 See in particular Seheer 2001: 623ff. 16 Cf. van den Hout 2005: 286ff. 17 Cf. van den Hout 2007: 340-341. 18 See below, KUB 31.103; 230/f; KBo 14.45; KBo 28.65; KBo 28.82; 544/f.

Sealed Tablets from Ḫattuša

83

and in the Lower City,19 in the vicinity of the southeastern storerooms of Temple 1.

Following P. Neve in his analysis of the archaeological remains of Büyükkale, it is possible to suggest that the tablets and fragments unearthed in the general area of building C have been found in secondary context.20 According to his reconstruction, both natural phenomena and later Phrygian building activities disturbed the original condition of building C. Further, we also have to note that the large majority of the 188 entries concerning building C listed on the online ‘Korkordanz der hethitischen Texte’ (version 1.7) were unearthed in the rubble in or under the Phrygian wall. Therefore, although the tablets found in the area of building C could have been part of a text collection stored in the edifice, for the time being there is no clear evidence to confirm this. With regard to this last point, note that Hans G. Güterbock suggested that among the finds coming from building C, some should be considered as stray finds from building A.21 We could then hypothesize that at least some texts coming from the area of building C were originally placed in building A and only later removed due to building activities on the site.

Building A is located on the southwestern side of the middle courtyard of the citadel. An upper floor was probably on the level of the courtyard, whereas a lower floor, rooms one to six in the southern part of the structure, lay on the level of the lower courtyard. About four thousand tablets and fragments were excavated in these rooms and a large number of additional items were found in secondary position in and outside the building, some at a great distance from it.22 These tablets could have resided either on the upper or the lower floor of the building and consisted of texts dating from the Old Kingdom to the Late Empire period. They deal in particular with the cultic system (rituals, festivals), but also include mythological texts, historiographical texts, Sumero-Akkadian literature, and foreign compositions. It seems therefore that building A accommodated texts

19 See below KUB 25.32; KBo 28.108+. 20 Neve 1982: 113-115. 21 Güterbock 1991-92. 22 Accurate analyses on this building can be found in Otten 1986; Güterbock

1991-92; Košak 1995; Alaura 1998; ead. 2001; Klinger 2006; van den Hout 2006; id. 2008.

Maria Elena Balza 84

intended for both the creation and preservation of the Hittite cultural heritage and the transmission of this heritage to future generations of scribes and scholars. For these reasons, S. Košak identified building A with the ‘palace library’ of the Hittite capital city.23

If we hypothesize that the sealed tablets recovered in building C were originally part of the text inventory of building A, it would follow that the important text collection preserved in building A, namely in the main palace archive,24 could have included a section devoted to the keeping of sealed tablets.

This hypothesis seems however to contradict the information provided by the Hittite written sources, which indicate that the original copies of state treaties as well as some other official documents such as royal regulations and historical texts had to be written on metal writing boards and deposited in the temple in the presence of the gods, warrantors of the words recorded on the tablet.25

In Ḫattuša, the place of deposition before the gods should have been Temple 1 in the Lower City, identified with the cult-place of the Weather God of Ḫatti and the Sun Goddess of Arinna, but no (metal) sealed tablets have been found there. However, on the grounds of what we have assumed above, we have to posit that at least part of the official and verified documents preserved in the local archives were moved into a safer location when the Hittite ruling class abandoned the city, while others were perhaps subsequently melted down (in the case of metal tablets) or destroyed. Two fragmentary sealed tablets (see below) that the archaeologists found in the

23 Košak 1995. On the role and function of building A and other storage places of tablets in the city of Ḫattuša, see also van den Hout 2005; id. 2006; Klinger 2006.

24 For a definition of the term archive, we adopt that proposed by Brosius (2003: 10): “Archives are first a physical space within a public space (palace or temple complex, public archive) or within a private building or private complex of buildings, and second a collection of stored documents. The building which housed archival records was a ‘house of tablets’, while an archival room in the private sphere was a guarded place or simply a storeroom. A collection of records reflects a deliberate choice or selection of documents. These documents cover a certain period of time ranging from the number of reigning years of a king to several generations of a business family.”

25 For some examples, see Balza 2008: 340ff., with references therein. See also Roszkowska-Mutschler 2002: 296ff., who suggested that also the tablets of the Deeds of Šuppiluliuma could have been deposited in the temple.

Sealed Tablets from Ḫattuša

85

immediate vicinity of the southeastern storerooms of Temple 1 could provide additional clues to this reconstruction.

In a recent contribution on the administration at the time of Tutḫaliya IV and his successors, Th. van den Hout suggested that Temple 1, due to both its proximity to the city gates and the nature of the text collection kept in its storerooms (mainly composed of lists, inventories and registers), “emerges as a group of offices with a strong registering character” (van den Hout 2006: 95). Therefore, according to van den Hout, in the Late Empire period Temple 1 probably represented an important administrative unit where the economic administration, the cult management, and the count and check of incoming goods were performed. This notwithstanding, the tablets and fragments found in the storerooms surrounding Temple 1 also consist of hundreds of rituals, descriptions of festivals, cultic inventories, epics, myths and prayers, incantations and oracle texts, lexical lists, thirty-four letters, as well as seventy treaties and other historical documents, thus covering a large range of text genres.26 It seems therefore that the storerooms surrounding Temple 1 were one of the main text repositories of the capital city, a central administrative knot. If, as it seems, the sealed tablets found in the vicinity of Temple 1 were originally part of the text collection of the temple storerooms, we would have a testimony to the preservation of clay sealed tablets in this location. Were they verified copies on clay of original metal tablets? Or do we have to assume that only few particularly relevant documents were inscribed on metal tablets, whereas the bulk of the verified legal texts were inscribed on clay?

Let us now briefly consider the storage places of the sealed tablets.

We would have expected that the official sealed tablets, due to their high legal status, would have been kept together in a single location, a proper state archive where the most important legal agreements were preserved together. As pointed out above, some references contained in Hittite texts suggest that this location should be the temple. However, other evidence seems to suggest that, in some instances, scribes had to draw up more than one copy of legal or official

26 Neve (1969: 9-19) suggested that Temple 1 represented one of the storage areas of state treaties. Other findspots of international treaties were the House on the Slope and building A; on this topic, see Alaura 2004 with references therein.

Maria Elena Balza 86

documents. At least one of these copies, but most likely more than one, must have been sealed and verified to be preserved by the contracting parties or the central administration:

A duplicate of this tablet is deposited before the Sun-goddess of Arinna (…). And in the land of Mittanni a duplicate is deposited before the Storm-god (…) (treaty between Šuppiluliuma I and Šattiwaza of Mittanni, Beckman 1999: 46). Dieser Tafel aber (ist) als siebentes Exemplar ausgefertigt und mit dem Siegel der Sonnengöttin von Arinna und mit dem Siegel des Wettergottes vom Ḫatti gesiegelt. (Davon) ist eine Tafel vor der Sonnengöttin von Arinna, eine Tafel vor dem Wettergott von Ḫatti, eine Tafel vor Lelwani, eine Tafel vor Ḫepat von Kizzuwatni, eine Tafel vor dem Wettergott piḫaššašši, eine Tafel im Königspalast vor Zitḫarija niedergelegt; eine Tafel aber hält Kurunta, König des Landes Tarḫuntašša, in seinem Hause. (Bronze Tablet, Otten 1988: 28-29). Ora una tavoletta davanti alla dea del Sole di Arinna posero, ed una tavoletta (davanti) al dio della tempesta di Ḫatti, [ed] una ta[voletta (…) ed essa i figli di dU-manawa hanno. (‘Title-deed of Šaḫurunuwa’, Imparati 1974: 34-35).

This being the case, we could hypothesize that, in the case of Ḫattuša, in addition to the tablets deposited in the main city temple (Temple 1) and in other Hittite sanctuaries, at least one sealed copy of official agreements would have been kept within the ‘house of the king’ (as the references contained in the Bronze Tablet seem to suggest). Could we suggest that this location corresponded to the palace archive, that is, building A on the acropolis? This hypothesis would, on the one hand, corroborate the information on the drafting and keeping of some kinds of official documents contained in the texts and mentioned above; and on the other hand, it would provide new evidence as to the function of building A within the Hittite central administration.

Sealed Tablets from Ḫattuša

87

4. After these preliminary remarks, let us focus our attention on the extant sealed tablets. Some of these were drafted by the Hittite central administration, while others are letters from abroad.27

4.1. 230/f (CTH 212) (Fig. 1)

The fragment 230/f was found during the 1930s on the acropolis, in building A, north side of room 6 (excavation quadrat v/10). It has been subsequently published by H. G. Güterbock (1940: 7 = SBo I text 1). The few preserved lines of the tablet refer to cities and watch-posts and to the death of the father of the text’s author. The structure of these few lines remind us of the historical prologues of Hittite state treaties, even though the extant elements are too limited – no place nor person names have been preserved – to define the text genre more precisely.28 See however the text incipit: 230/f Vs. 5’ [ki-i]š-ša-an [ 6’ [ ]x-wa ku-it [ 7’ [a]r-ḫa ḫar-kán [ 8’ [U]RUDIDLI.ḪI.A BÀD GAL-TIM [ 9’ a-ú-ri-e-eš [ 10’ nu-wa ḫu-u-ma-an-za [ 11’ ma-aḫ-ḫa-an-ma-wa-za [ 12’ nu-wa ku-e-da-ni ku-it IŠ-TU x[ 13’ kat-ta-an ḫa-ma-an-kán nu-wa-ra-[ 14’ ma-aḫ-ḫa-an-ma-za A-BU-YA �KUR� [ 15’ nu-za A-BU-YA DINGIR-LIM-iš [29 § 16’ ma-aḫ-ḫa-an-za-kán DUTUŠI [30

27 In addition to the texts presented below, see also Dinçol – Dinçol 2008: 22, Bo 84/501 = nr. 23, Tafel 2, ‘Fundort’ M/9 – f 10, a further sealed tablet from Ḫattuša, which is too fragmentary to be taken into consideration.

28 On this topic see also Güterbock (1940: 7): “Die Urkunde bezieht sich also auf ein grösseres Gebiet und beginnt, wie die Staatsverträge, mit einer historischen Einleitung, die auf Anordnungen des Vaters des Verfassers Bezug nimmt.”

29 See the transcription of Güterbock 1940: 6 (with n. 22), l. 15: nu-za A-BU-YA DINGIR-LIM-iš [ki-ša-at].

30 See the transcription of Güterbock 1940: 6 (with n. 22), l. 16: ma-aḫ-ḫa-an-za-kán DUTUŠI [A-NA GIŠGU.ZA A-BI-YA e-eš-ḫa-at].

Maria Elena Balza 88

17’ nu �ṬUP-PUMEŠ� a-ra-x[31 Vs. 7’-16’: (...) was destroyed (...), the towns with large fortifications (...) and the watch-posts (...) and everyone (...) But as (…) and somebody [was] with (…) is bonded and (…) But as my father the Land (…) and my father [became] god (…) and as I, My Sun (…) then the tablets (…)

The tablet had been impressed, in the center of the obverse, with a

fragmentary stamp seal (SBo I 9) whose cuneiform inscription is only partially preserved (Fig. 2). Due to the reading of these two fragmentary lines and thanks to the clues they could provide as to the identification of the seal owner,32 Güterbock tentatively dated the text at the time of Šuppiluliuma I. More recently, on the basis of paleographical analysis, H. Otten and C. Rüster (Otten – Rüster 1995) suggested a dating to the first years of the reign of Muršili II, when the princess of Babylon, wife of Šuppiluliuma, mentioned in the seal legend, could have been associated with the throne of Ḫatti.

4.2. KBo 14.45 (CTH 85.3) (Fig. 3)

The text fragment KBo 14.45 was unearthed in 1959 on the acropolis in the excavation quadrats v/10 or v/11, which include part of building A, in particular rooms 5 and 6, and the area surrounding room 6. H. Otten (1962: 75-76) classified the document as some ordering or regulation of the Great King Ḫattušili III on behalf of an unknown individual, perhaps somebody who helped him when he seized the throne of Ḫatti. The remaining lines of the text recall the fight of the author against an unnamed enemy, possibly identifiable with Urḫi-Teššup (l. 3 x]-⌈še?⌉-kán? ma-ni-ia-aḫ-ḫa-uš da-[a-i l. 4 ]an-na-az? iš-pár-ru-wa-an da[a-i). Accordingly, the events mentioned in the text have been recognized as the struggles for power between uncle and nephew.33 The textual evidence is too limited (only ten

31 See the transcription of Güterbock 1940: 7, l. 17: nu ṬUP-PUMEŠ a-ra-aḫ(?)-[… 32 See the seal legend: 1 […Ḫ]a-at-ti NA-RA-AM d[x] 2 […] DUMU.MUNUS

LUGAL [KUR] KÁ.DINGIR.[RA] (1 (…) Ḫatti beloved by the god (…) 2 (…) daughter of the king of Babylon).

33 See Otten 1962: 75: “Von Ḫattušili III. stammt eine gesiegelte Tafel, 200/q, die einen historischen Bericht über sein Verhalten gegenüber Urḫi-Tešub gibt, in

Sealed Tablets from Ḫattuša

89

fragmentary lines have been preserved) to provide for a more precise definition of the tablet genre and a connected translation.

The tablet bears the fragmentary impression of a stamp seal belonging to Ḫattušili III and Puduḫepa (Fig. 3).34

4.3. 544/f (CTH 96) (Fig. 4)

The text fragment 544/f was found on the acropolis – building C, excavation quadrats q-r/16-17 – during the 1930s. On the basis of internal elements and the fragmentary seal impression, the text has been attributed to Kurunta of Tarḫuntašša. In the few remaining lines, the author of the text recounts his treatment at the hands of Ḫattušili III as well as his accession to the throne of Tarḫuntašša. The text was first edited by H. G. Güterbock (1942: 10-11 = SBo II text 1) and, more recently, by G. Beckman (1989-90: 291).

On the center of the obverse, the tablet bears the impression of the Kurunta seal (SBo II 5, see Fig. 5).

4.4. KUB 25.32 (CTH 681.1)

This tablet fragment is part of the so-called Festival of Karaḫna, (CTH 681.1 = KBo 39.154+57.202+KUB 25.32+27.70), a four-column tablet in a good state of preservation. The tablet fragments were probably unearthed in the area of Temple 1, among the debris around storeroom 12 in the excavation quadrat L/19. The text deals with the provincial festival of the tutelary deity of Karaḫna and the offerings provided on this occasion to the entire pantheon of this town. For the text edition, see A. M. Dinçol and M. Darga (Dinçol-Darga 1969-70), and G. McMahon (McMahon 1991).

The seal SBo II 92, impressed on the tablet fragment KUB 25.32, belongs to Taprammi (EUNUCHUS2 LEPUS+ra/i-mi EUNUCHUS2 SCRIBA), a well-known official active during the reign of the Great zum Teil wörtlicher Übereinstimmung zu seinem Thronbesteigungsbericht. Vielleicht handelt es sich um die Einleitung zu einer Urkunde, die einem Parteigänger Amt und Lehen zuspricht.” On this topic, see also Houwink ten Cate 1974: 148; Klengel 1999: 220 [B2], 238 [A4].

34 This seal impression has been identified with the seal Beran 1967: n. 230a (p. 42, Gruppe XIX, Tafel XI).

Maria Elena Balza 90

King Tudḫaliya IV and most probably involved with the cult administration (Fig. 6).

KUB 25.32 is a long and detailed list of actions to be performed during the ceremonies organized in honor of the tutelary deity of Karaḫna and does not constitute a legal document. Consequently, it should not have needed to be verified through the presence of seal impressions and it likely represents a special case. This text could possibly be connected to the general cult restoration undertaken at the time of Tutḫaliya IV, and Taprammi, the official who sealed the text, could be a high dignitary involved in this process.35

4.5. Bo 9364 (CTH 222?) (Fig. 7)

The small fragment Bo 9364 contains only five lines. An autography of the text was first published by H. G. Güterbock (1942: 82 = SBo II text 2). The few preserved lines contain the beginnings of some personal names. Among them, there is most likely the name Piḫamuwa (Bo 9364:3’ mpí-ḫa-m[u- ]).

The tablet fragment bears the seal SBo II 100, belonging to a person called Walwaziti (LEO-VIRzi), as the hieroglyphic legend of his seal attests (Fig. 8).

As already noted by some scholars, the Walwaziti and Piḫamuwa whose names appear on this document could be identified with two high officials of the same name active in the second half of the 13th century BC.36 Walwaziti, in particular, is mentioned in a number of texts dating to the reigns of Ḫattušili III and Tudḫaliya IV, and was probably involved in the Hittite administration. Unfortunately, the findspot of Bo 9364 is unknown.

4.6. KUB 31.103 (CTH 212) (Fig. 9)

The partially preserved tablet KUB 31.103 – uncovered in the citadel, building A, room 4 – shares some features with the Land Grand Documents (Klengel 1999: 119 [A14]) but, on the basis of the

35 On Taprammi, see Mora 2006: 139-140. 36 On Piḫamuwa, see Mora 2004: 436; on Walwaziti, see Mora 2006: 141-142

with literature therein.

Sealed Tablets from Ḫattuša

91

preserved lines, it has been interpreted as a state treaty. In particular, this document has been compared to the treaty between Arnuwanda I and the men of Išmeriga37 and its dating has been established to the Middle Hittite Kingdom (Arnuwanda I).38 The roughly forty preserved lines have been in part translated by G. Torri (2005: 391-393).

As suggested by the traces of the box inscribed on the tablet by the hand of the scribe and marking off the area in which the seal had to be impressed, the tablet originally bore a seal impression on the center of the obverse.39 Even though the seal impression is not preserved, this text represents a testimony to the keeping of sealed state treaties inscribed on clay in building A of the citadel. Another piece of evidence to the keeping of clay sealed tablets recording treaties is represented by KBo 28.108+, uncovered in the area of Temple 1.

4.7. KBo 28.108+ (CTH 29.A) (Fig. 10)

The archaeological investigations carried out in 1969 on the Lower City of Ḫattuša, in particular on the southeastern front of Temple 1 (to the east of storerooms 11 and 12), brought to light, among hundreds of other fragments, a clay fragment bearing the nearly complete seal impression Bo 69/200. This fragment originally belonged to one of the clay tablets stored in the Temple 1 archive.

The design of Bo 69/200 displays a central rosette and a two-line cuneiform inscription, and can be counted among the so-called ‘Tabarna Siegel’ (see Fig. 11):

(1) NA4KIŠIB ta-ba-ar-na Ta-ḫur-wa-i-l[i LUGA]L.GAL (2) ŠA A-WA-AT-ŠÚ UŠ-PA-AḪ-ḪU BA.ÚŠ40 (1) Seal of tabarna Taḫurwaili Great King (2) who will alter his word, will die

37 See Kempinski – Košak 1970 for the text edition. 38 See Torri 2005, with references therein. 39 For some remarks on the sealing of Hittite state treaties and comparisons

with different texts, see Wilhelm 1988: 362-363; Herbordt 2005: 28-29; Balza 2008. 40 Otten 1971: 59.

Maria Elena Balza 92

In the same excavation area (storerooms 11 and 12, excavation quadrats L/19, p-q/10-11N), the archeologists unearthed the tablet fragment KBo 28.108+ (CTH 29.A) belonging to the treaty (in Akkadian) concluded between the Middle-Hittite king Taḫurwaili and Eḫeya of Kizzuwatna. On the basis of the analysis of the items uncovered in the same findspot, H. Otten (1971: 66ff.) put forward the hypothesis that the tablet fragment bearing the seal impression Bo 69/200 and the fragment containing the treaty with Kizzuwatna belonged to one and the same text. According to this hypothesis, the tablet KBo 28.108+ would therefore represent, like KUB 31.103, the original copy on clay of an international treaty coming from the Hittite capital city. The poor state of preservation of the tablet does not allow for a connected translation of the whole text, even though a partial translation has been provided by H. Otten (1971: 66ff.). A transcription and translation of the tablet have been also provided by G. F. del Monte (1981: 210ff.).

4.8. KBo 28.65 (CTH 179) (Fig. 12)

This fragment, belonging to an Akkadian letter coming from Ḫanigalbat, was discovered in the 1930s on the acropolis, on the north side of room 6 of building A (excavation quadrat v/10). An autography and transcription of the tablet have been provided by H.G. Güterbock (1942: 37-38 = SBo II text 4). See the incipit of the text: KBo 28.65 Vs. 1 a-na mDUTUši [ 2 a-bi-ia qí-bi[-ma 3 um-ma LUGAL KUR Ḫa-ni-ga[l-bat-ma 4 ⌈a⌉-na ka-ša a-na É-ti MUNUS-t[i] 5 [ù] ⌈a-na KUR-ti⌉-k[a] ⌈lu-u⌉ [ Vs. 1-5: ‘To My Sun’ (…) my father, say (…) “Thus (speaks) the king of Ḫanigalbat (…) To you, (your) house, (your) woman [and] you[r] land [health!]” (The following lines do not allow for a connected translation).

Sealed Tablets from Ḫattuša

93

As the few preserved lines attest, the letter was sent by a king of Ḫanigalbat to a Hittite king. Both the name of the sender and the addressee are unknown. Güterbock suggested that, if the expression ‘my father’ in l. 2 could be understood in a literal sense, the sender could be identified with Šatiwazza, son-in-law of Šuppiluliuma I; if on the contrary the expression ‘my father’ has to be interpreted as a simply epistolary formula, the text would (likely) still be dated to the period of Hittite sovereignty over Mittani. In fact, the mention of Taidu in l. 5 of the reverse (KBo 28.65 Rs. 5’ [……] x URUTa-i-te i-na x […])41 can be interpreted as a reference to the military campaigns of the Assyrian king Adad-nērārī I against this city.42

According to H. Klengel the addressee of the letter should be identified either with Ḫattušili III or Tudḫaliya IV.43 In fact, the formula ‘my father’ appears also in IBoT 1.34, another letter sent by a king of Ḫanigalbat to a Hittite king, and thus drafted in the same period as KBo 28.65.44 Starting with the mention of Eḫli-Šarruma – contemporary with the Assyrian king Šalmanasser – Klengel suggested that the sender of IBoT 1.34 was Šattuara II, contemporary with both Ḫattušili III and Tutḫaliya IV.45 If this were the case, the king of Ḫanigalbat would have used the designation ‘my father’ as he was in a precarious political situation, caught between two lords, the king of Ḫatti and the king of Assyria.

On the basis of the extant elements, even though the dating of KBo 28.65 remains uncertain, the evidence at our disposal speaks in favor of a drafting of the document during the second half of the 13th century BC.

The tablet was sealed, on the reverse and on the lower edge, with the anepigraphic cylinder seal SBo II 235 (Fig. 13). The seal design follows the tradition of Mittanian glyptic. It displays a deity mounted on a lion and surrounded by pairs of antelopes, recumbent goats and

41 As for the mentions of this site in Assyrian and Hittite sources, see Wäfler 1994.

42 See also Harrak 1987: 61ff. 43 See Klengel 1999: 282 [A18]. See also Mora – Giorgieri 2004: 192 n. 46. 44 See Klengel 1963; id. 1999: 282 [A17]. 45 For the dating of this text see also Singer 1985: 115; and Harrak 1987: 78:

“the time of Šattuara I and his son Wasašatta seems reasonable. These kings have lived under two authoritarian rulers: the king of Assyria and the one of Ḫatti.” See also Mora – Giorgieri 2004: 192 n. 46.

Maria Elena Balza 94

composite demons arranged antithetically on either side of the sacred tree.46

4.9. KBo 28.82 (CTH 208) (Fig. 14)

KBo 28.82 is an Akkadian letter unearthed in building C on the acropolis (excavation quadrats q-r/16-17) that has been published by H. G. Güterbock (1942: 36-37 = SBo II text 3).47 The sender’s name is missing, whereas the names of the addressees are Bilanza and Sunailu.

Concerning the text content, Güterbock put forward that the subject matter of the letter is robberies, some of which can be placed in Kašiari (Tūr ʿAbdīn).48 He also wondered if the recipients of the letter were the commanders of a Hittite border garrison that was settled in the vicinity of the area directly concerned with the robberies.49 Similarly, B. Faist has suggested that the letter could attest to the existence of some form of collaboration between Hittites and Assyrians to ensure the security of the merchants and their caravans.50 This notwithstanding, according to C. Mora and M. Giorgieri the tablet does not seem to display typical Middle-Assyrian textual feature and should be assigned to private rather than diplomatic correspondence. If this were the case, the finding of this letter would raise some questions: why was it stored in the citadel of Ḫattuša? To which text collection did it belong?51

46 See Stein 1993-97: 298. 47 See also Hagenbuchner 1989: 414 nr. 306, with the bibliography there quoted. 48 See KBo 28.82 Rs. 6 x GAL(?) x ḫal-qù x [ ]-a 7 ù(?) URU(?)Za-bu-ú-ri x [ 8 za-ak-ki-<šu->nu te-er-šu[-nu 9 a-ga-nu KÙ.BABBAR i-na KURKa-si-a-ri 49 See Güterbock 1942: 37, “Gegenstand des Schreibens sind Räubereien, von

denen sich wenigstens eine lokalisieren lässt: im Kašiari/Gebirge (Tūr ʿAbdīn). Waren die Empfänger des Briefes demnach Grenzkommandanten in einem Gebiet, das mit dieser Gegend Beziehungen hatte?” See also Hagenbuchner 1989: 414 nr. 306.

50 See Faist 2001: 134 n. 128. 51 Consider however that the incipit of the letter seems to suggest some official

relevance or intention: KBo 28.82 Vs.

Sealed Tablets from Ḫattuša

95

On the left edge, the tablet bears the impression of the anepigraphic cylinder seal SBo II 233 (Fig. 15). The seal design is very poorly preserved. The portion of the scene that is still recognizable simply displays two (or three) quadrupeds, but the extant information is too fragmentary to allow comparisons with Middle-Assyrian or Mittanian glyptic.

5. As testified to by the above texts, the extant sealed tablets from

Ḫattuša can provide only little information on filing procedures and document management. They can however offer additional testimony to the central role of building A in the citadel and Temple 1 as repositories of documents intended for the preservation and transmission of the cultural and legal roots of Hittite heritage. The sealed texts, dating from the Middle Kingdom through to the Empire Period, cover the range of legal documents essential to manage present-day and future political relationships, testify and justify royal decisions and hand on the political and cultural identity of the Hittite ruling class.

The question as to the existence and fate of the Hittite archives of sealed tablets still remains open, but future archaeological excavations will hopefully shed new light on this fundamental problem for Hittite history.

1 a-na mBi-la-an-za 2 ù mSu-na-i-lum um-[ma -t]a?-ma 3 ul-ṭu4-ḫe-ḫí-in lu šùl-mu 4 a-na KUR-at Ḫa-at-⌈te-e⌉(?) lu šùl-mu

Maria Elena Balza 96

Bibliography

Alaura, S. 1998, “Die Identifizierung der im „Gebäude E“ von Büyükkale-

Boğazköy gefundenen Tontafelfragmente aus der Grabung von 1933”, AoF 25, 193-214.

2001, “Archive und Bibliotheken in Ḫattuša”, in: G. Wilhelm (Hrsg.), Akten des IV. Internationalen Kongresses für Hethitologie, Würzburg, 4.–8. Oktober 1999 (StBoT 45), Wiesbaden, 12-26.

2004, “Osservazioni sui luoghi di ritrovamento dei trattati internazionali a Boğazköy-Ḫattuša”, in: D. Groddek − S. Rößle (Hrsg.), Šarnikzel. Hethitologische Studien zum Gedenken an Emil Orgetorix Forrer (DBH 10), Dresden, 139-147.

Balza, M. E. 2008, “I trattati ittiti. Sigillatura, testimoni, collocazione”, in: M.

Liverani – C. Mora (edd.), I diritti del mondo cuneiforme, Pavia, 387-418.

Beckman, G. 1989-90, Review of: H. Otten, Die Bronzetafel aus Boğazköy. Ein

Staatsvertrag Tutḫalijas IV. (StBoT, Beiheft 1), Wiesbaden 1988, WO 20-21, 289-294.

1999, Hittite Diplomatic Texts. Second Edition, Atlanta. Beran, Th. 1967, Die hethitische Glyptik von Boğazköy. 1. Die Siegel und Siegelabdrücke

der vor- und althethitischen Perioden und die Siegel der hethitischen Grosskönige (WVDOG 76), Berlin.

Bittel, K. 1950, “Bemerkungen zu dem auf Büyükkale (Boğazköy) entdeckten

hethitischen Siegeldepot”, JKlF 1, 164-173.

Sealed Tablets from Ḫattuša

97

Brosius, M. 2003, “Ancient Archives and Concepts of Record-Keeping: an

Introduction”, in: M. Brosius (ed.), Ancient Archives and Archival Traditions, Oxford 2003, 1-16.

Cardascia, G. 1995, “Réflexion sur le témoignage dans les Droits du Proche-Orient

ancien”, Revue historique de droit français et étranger 73, 549-557. Cornil, P. 1987, “Textes de Boğazköy. Liste des lieux de trouvaille”, Hethitica 7,

5-72. del Monte, G. F. 1981, “Note sui trattati tra Ḫattuša et Kizuwatna”, OA 20, 203-221. Dinçol, A. M. − Darga, M. 1969-70, “Die Feste von Karaḫna”, Anatolica 3, 99-118. Dinçol, A. M. – Dinçol B. 2008, Die Prinzen- und Beamtensiegel aus der Oberstadt von Boğazköy-Ḫattuša

vom 16. Jahrhundert bis zum Ende der Grossreichszeit (BoHa XXII), Mainz.

Faist, B. 2001, Der Fernhaldel des assyrischen Reiches zwischen dem 14. und 11. Jh. vor

Chr., Münster. Güterbock, H. G. 1939, “Das Siegeln bei den Hethitern”, in: J. Friedrich et alii (Hrsg.),

Symbolae ad jura Orientis antiqui pertinentes Paulo Koschaker dedicatae, Leiden, 26-36.

1940, Siegel aus Boğazköy. 1. Teil: Die Königssiegel der Grabungen bis 1938 (AfO, Beiheft 5), Berlin.

1942, Siegel aus Boğazköy. 2. Teil: Die Königssiegel von 1939 und die übrigen Hieroglyphensiegel (AfO, Beiheft 7), Berlin.

1980, “Seals and Sealing in Hittite Land”, in: K. De Vries (ed.), From Athens to Gordion. Papers of a Memorial Symposium for Rodney S. Young, Philadelphia, 51-63.

Maria Elena Balza 98

1991-92, “Bemerkungen über die im Gebäude A auf Büyükkale gefundenen Tontafeln”, AfO 38-39, 132-137.

Hagenbuchner, A. 1989, Die Korrespondenz der Hethiter (THeth 15-16), Heildelberg. Harrak, A. 1987, Assyria and Ḫanigalbat, Hildesheim – Zürich – New York. Herbordt, S. 2005, Die Prinzen- und Beamtensiegel der hethitischen Grossreichszeit auf

Tonbullen aus dem Nişantepe-Archiv in Hattusa (BoHa XIX), Mainz. Herbordt, S. – Bawanypeck, D. – Hawkins, J. D. 2011, Die Siegel der Grosskönige und Grossköniginnen auf Tonbullen aus dem

Nişantepe-Archiv in Hattusa (BoHa XXIII), Darmstadt – Mainz. Hoffner, H. A. Jr. 1997, The Laws of the Hittites. A Critical Edition, Leiden – New York –

Köln. 2002, “Hittite Archival Documents, B. Courtcases: 1. Records of

Testimony Given in Trials of Suspected Thieves and Embezzlers of Royal Property”, in: W. W. Hallo (ed.), The Context of Scripture 3, Leiden – Boston – Köln, 57-60.

Houwink ten Cate, Ph. H. J. 1974, “The Early and Late Phases of Urhi-Tesub’s Career”, in: K.

Bittel et alii (eds.), Anatolian Studies Presented to Hans Gustav Güterbock on the Occasion of his 65th Birthday, Istanbul, 123-150.

Imparati, F. 1974, Una concessione di terre da parte di Tudḫaliya IV (= RHA 32), Paris. 1983, “Aspects de l’organisation de l’État hittite dans les documents

juridiques et administratifs”, JESHO 25, 225-267. 1999, “Die Organisation des hethitischen Staates”, in: H. Klengel

1999, 320-387.

Sealed Tablets from Ḫattuša

99

Karasu, C. 1996, “Some Remarks on Archive-Library System of Ḫattuša-

Boğazköy”, ArAn 2, 39-59. Kempinski, A. – Košak, S. 1970, “Der Išmeriga- Vertrag”, WO 5, 191-217. Klengel, H. 1963, “Zum Brief eines Königs von Ḫanigalbat (IBoT I 34)”, Or 32,

280-291. 1999, Geschichte des hethitischen Reiches (HdO I/34), Leiden – Boston –

Köln. 2003, “Einige Bemerkungen zur Struktur des Hethitischen Staates”,

AoF 30, 281-289. Klinger, J. 2006, “Der Beitrag der Textfunde zur Archäologiegeschichte der

hethitischen Hauptstadt”, in: D. P. Mielke – U.-D. Schoop – J. Seeher (Hrsg.), Strukturierung und Datierung in den Hethitischen Archäologie: Voraussetzungen, Probleme, Neue Ansätze. Internationaler Workshop, Istanbul, 26-27. November 2004 (= Byzas 4), 3-17.

Košak, S. 1995, “The Palace Library ‘Building A’ on Büyükkale”, in: Th. P. J.

van den Hout – J. de Roos (eds.), Studio Historiae Ardens. Ancient Near Eastern Studies Presented to Philo H.J. Houwink ten Cate on the Occasion of his 65th Birthday (PIHANS 74), Leiden, 173-179.

Laroche, E. 1949, “La bibliothèque de Hattuša”, ArOr 17, 7- 23. Marazzi, M. 1994, “Ma gli Hittiti scrivevano veramente su legno?”, in: P. Cipriano

– P. di Giovine – M. Mancini, (edd.), Miscellanea di studi linguistici in onore di W. Belardi, Roma, 131-160.

2000, “Sigilli e tavolette di legno: le fonti letterarie e le testimonianze sfragistiche nell’Anatolia ittita”, in: M. Perna (ed.), Administrative Documents in the Aegean and their Near Eastern Counterparts, Torino, 79-189.

Maria Elena Balza 100

2007, “Sigilli, sigillature e tavolette di legno: alcune considerazioni alla luce di nuovi dati”, in: M. Alparslan – M. Doğan-Alparslan – H. Peker (eds.), Vita. Belkıs Dinçol ve Ali Dinçol’a Armağan/Festschrift in Honor of B. Dinçol and A. Dinçol, Istanbul, 465-474.

McMahon, G. 1991, The Hittite State Cult of the Tutelary Deities, Chicago. 1997, “Hittite Canonical Compositions. 3. Instructions: Instructions

to Commanders of Border Garrisons (BĒL MADGALTI)”, in: W. W. Hallo (ed.), The Context of Scripture 1, Leiden – New York – Köln, 221-225.

Mora, C. 2004, “Sigilli e sigillature di Karkemiš in età imperiale ittita I. I re, i

dignitari, il (mio) Sole”, Or 73, 427-450. 2006, “Riscossione dei tributi e accumulo dei beni nell’impero ittita”,

in: M. Perna (ed.), Fiscality in Mycenaean and Near Eastern Archives, Napoli, 133-146.

2007, “I testi ittiti di inventario e gli ‘archivi’ di cretule. Alcune osservazioni e riflessioni”, in: D. Groddek – M. Zorman (Hrsg.), Tabularia Hethaeorum. Hethitologische Beiträge S. Košak zum 65. Geburtstag (DBH 25), Wiesbaden, 535-550.

Mora, C. – Giorgieri, M. 2004, Le lettere tra i re ittiti e i re assiri ritrovate a Ḫattuša, Padova. Neve, P. 1969, “Der große Tempel und die Magazine”, in: K. Bittel et alii,

Boğazköy IV. Funde aus den Grabungen 1967 und 1968 (AbhDOG 14), Berlin, 9-19.

1982, Büyükkale, die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954-1966 (BoHa XII), Berlin.

Otten, H. 1971, “Das Siegel des hethitischen Großkönigs Taḫurwaili”, MDOG

103, 59-68. 1985, “Blick in die altorientalische Geisteswelt. Neufund einer

hethitischen Tempelbibliothek”, Jahrbuch der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen 1984, Göttingen, 50-60.

Sealed Tablets from Ḫattuša

101

1986, “Archive und Bibliotheken in Hattuša”, in: K. R. Veenhof (ed.), Cuneiform Archives and Libraries. Papers Read at the 30e Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Leiden, 4-8 July 1983, Leiden, 184-190.

Otten, H. – Rüster, C. 1995, “Ein Siegel des hethitischen Grosskönigs Muršili II. und der

Tawananna”, in: U. Finkbeiner − R. Dittmann − H. Hauptmann (Hrsg.), Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte Vorderasiens. Festschrift für Reiner Michael Boehmer, Mainz, 507-512.

Renger, J. 1977, “Legal Aspects of Sealing in Ancient Mesopotamia”, in: McG.

Gibson – R. Biggs (eds.), Seals and Sealing in the Ancient Near East (BiMes 6), Malibu, 75-88.

Roszkowska-Mutschler, H. 2001, “Zu den Mannestaten der hethitischen Könige und ihrem Sitz

im Leben”, in: P. Taracha (ed.), Silva Anatolica. Anatolian Studies presented to M. Popko on the occasion of his 65th Birthday, Warsaw, 289-300.

Schaeffer, Cl. 1956, Recueil des sceaux et cylindres hittites imprimés sur les tablettes des

Archives Sud du palais de Ras Shamra suivi de considérations sur les pratiques sigillographiques des rois d’Ugarit, in: C. Schaeffer, Matériaux pour l’étude des Relations entre Ugarit et le Hatti (= Ugaritica III), Paris, 1-86.

Seeher, J. 2001, “Die Zerstörung der Stadt Ḫattuša”, in: G. Wilhelm (Hrsg.),

Akten des IV. Internationalen Kongresses für Hethitologie, Würzburg, 4.–8. Oktober 1999 (StBoT 45), Wiesbaden, 623-634.

Singer, I. 1985, “The Battle of Niḫriya and the End of the Hittite Empire”, ZA

75, 100-123. Starke, F. 1996, “Zur ‘Regierung’ des hethitischen Staates”, ZAR 2, 140-183.

Maria Elena Balza 102

Stein, D. 1993-1997, “Mittan(ni). B Bildkunst und Architektur”, RlA 8, 296-

299. Symington, D. 1991, “Late Bronze Age Writing-Boards and Their Uses: Textual

Evidence from Anatolia and Syria”, AnSt 41, 111-123. Torri, G. 2005, “Militärische Feldzüge nach Ostanatolien in der

mittelhethitischen Zeit”, AoF 32, 386-400. 2008, “The Scribes of the House on the Slope” in: A. Archi – R.

Francia (edd.), Atti del VI Congresso Internazionale di Ittitologia. Roma, 5-9 settembre 2005, Parte II (= SMEA 50), 771-782.

2009, “The Old Hittite Textual Tradition in the ‘Haus am Hang’”, in: F. Pecchioli Daddi – G. Torri – C. Corti (eds.), Central-North Anatolia in the Hittite Period – New Perspectives in Light of Recent Research. Acts of the International Conference Held at the University of Florence (7-9 February 2007) (Studia Asiana 5), Roma, 207-222.

van den Hout, Th. P. J. 2002, “Another View of Hittite Literature“, in: S. de Martino – F.

Pecchioli Daddi (edd.), Anatolia Antica. Studi in memoria di Fiorella Imparati (Eothen 11), Firenze, 857-878.

2005, “On the Nature of the Tablets Collections of Ḫattuša”, SMEA 47, 277-289.

2006, “Administration in the Reign of Tutḫaliya IV and the Later Years of the Hittite Empire”, in: Th. P. J. van den Hout (ed.), The Life and Times of Ḫattušili III and Tutḫaliya IV – Proceedings of a Symposium held in Honour of J. De Roos, 12-13 December 2003, Leiden (PIHANS 103), Leiden, 77-106.

2007, “Seals and Sealing Practices in Hatti-Land: Remarks à propos the Seal Impressions from the Westbau in Ḫattuša”, JAOS 127/3, 339-348.

2008, “Verwaltung und Vergangenheit. Record Management im Reich der Hethiter”, in: G. Wilhelm (Hrsg.), Ḫattuša – Boğazköy. Das Hethiterreich im Spannungsfeld des Alten Orients. 6. Internationales Colloquium der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 22.–24. März 2006, Würzburg (CDOG 6), Wiesbaden, 87-94.

Sealed Tablets from Ḫattuša

103

Waal, W. 2011, “They Wrote on Wood. The Case for a Hieroglyphic Scribal

Traditions on Wooden Writing Boards in Hittite Anatolia”, AnSt 61, 21-34.

Wäfler, M. 1994, “Taddum, Tîdu und Ta’idu(m)/Tâdum”, in: P. Calmayer et alii

(Hrsg.), Beiträge zur Altorientalischen Archäologie und Altertumskunde. Festschrift für B. Hrouda zum 65. Geburtstag, Wiesbaden, 293-302.

Wilhelm, G. 1988, “Zur ersten Zeile des Šunaššura-Vertrages”, in: E. Neu – C.

Rüster (Hrsg.), Documentum Asiae Minoris antiquae. Festschrift für H. Otten zum 75. Geburtstag, Wiesbaden, 359-370.

Sealed Tablets from Ḫattuša

105

Fig. 4: 544/f (= SBo II 1).

Fig. 5: SBo II 5. Fig. 6: SBo II 92 (hethiter.net/:PhotArchBoFN01748).

Fig. 15: SBo II 233.

Sealed Tablets from Ḫattuša

109

Fig. 11: Bo 69/200 (from K. Bittel – P. Neve, “Vorläufiger Bericht über die Ausgrabungen in Boğazköy im Jahre 1969”, MDOG 102 [1970]: 5-26, Abb. 2).

Fig. 12: KBo 28.65.