School to Work Transition and its Impact on

Transcript of School to Work Transition and its Impact on

SCHOOL TO WORK TRANSITION AND ITS IMPACT ON

CREATION OF NEETS AND FREETERS

Comparison study of contemporary issues in Japan and UK

By Honza Drobny and Shaun Bowers

AIMS Creation of NEETS and FREETERS How the policy makers reflect on social-economic changes

School to work transition for young people in UK and Japan

Influence of Economic changes on Youth labour market

DEFINITION OF TERMS The Youth Transition Model

These ideas attempt to explain the changes that may occur when an adolescent develops their independence and reaches adulthood; including the possible physical, mental, and emotional causes for such changes.

The basic understanding of transition is that it is a Examples of Transitions include: first date, boyfriend/girlfriend, getting married and leaving home, getting a job (Johnson, 2003)

Not in Education, Employment or Training (NEET)the group of young people that for some reason or other have dropped out of mainline education.

FreetersSome young people who worked as arbiters, which are a temporary job for students; after leaving school or university some of this cohort engaged in music or other activities other than these temporary jobs (Inui et al, 2005). The group labelled themselves as “free (-lanced) arbiters”

RESEARCH IN TO NEET/FREETERS:UK & EUROPE

The unemployment rate for 16- to 24-year-olds rose sharply in 2009, from 15% in 2008 to 19% in 2009. However, the rate had already been rising for a number of years before the recent recession, from 12% in 2004 to 15% in 2008. These rises have collectively more than offset the falls during the 1990s and, as a result, the unemployment rate for 16- to 24-year-olds in 2009 was actually higher than its previous peak in 1993.

RESEARCH IN TO NEET/FREETERS:UK & EUROPE

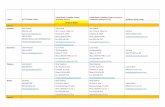

Walther and Pohl (2005 cited in Robson, 2008) divided countries into very high, high, medium, and low levels of NEET.

The UK, Poland and Spain were categorized as high, with rates between six and ten percent,

Finland, Austria, Greece, Slovakia and Italy. Were found to have medium NEET rates (between three and six percent)

Denmark and Slovenia had low rates – less than three percent.

JAPAN

The number of jobless young people, who are close to the concept of NEETs (currently Not in Education Employment or Training: economically inactive persons under the age group of 15 - 34, and who do not perform housework nor attend schools), reached up to 620,000 in 2007 which was at the same level as the previous year. The number of jobless young people aged 15 to 24 decreased by 40,000 (13.8%), compared with the peak number in 2002, while the number jobless young people aged 25 to 34 increased by 20,000 (5.7%).

ECONOMY’S INFLUENCE ON TRANSITIONS AND THE YOUTH

LABOUR MARKET an increase in unemployment caused in part by the economic recession; the majority of 16-years old leavers were spending time on government sponsored training schemes

less than one in five 13-17-year-olds (18 percent) were in full time employment more than six months after reaching the minimum school-leaving age

Policies, initiatives and services aimed at the socially excluded young people and young offenders tend to abruptly ‘end’ at aged 17 to 19

ECONOMY’S INFLUENCE ON TRANSITIONS AND THE YOUTH LABOUR MARKET: CONT

Policy makers and the media have suggested that a deficit of work ethics and a lack of motivation among young people had caused many of the problems that exist in the youth labour market (Inuit et al, 2005).

Could cause a decrease in tax revenue and endanger the social insurance system as the Freeters have low income and many do not have insurance (Inui et al, 2005).

feared that the skill level of Japanese workers would decrease because freeters transition into adulthood with no particular skills or work ethics.

COMBATING THE “PROBLEM”UK Modern apprenticeship was promoted by the government and targeted at all early school leavers

Education Maintenance Allowance (EMA)Criticism Modern Apprenticeships: Many of the young people who embarked on them did not complete it: only 40% got a vocational qualification from the apprenticeship scheme

EMA: NEETs are usually people who were disengaged from school, whether due to exclusion, bullying, learning difficulties, or disinterest

COMBATING THE “PROBLEM”Japan assigning job supporters to help new high school graduates to find jobs,

introducing probationary employment with a subsidy, establishing one-stop job placements centres

Criticism the probationary employment was just for 3 months and placed fewer than 40 thousand people in the scheme in 2004, as a comparison, The UK’s New deal provides 6 months probationary employment and placed 910, 000 young people over 4,5 years

considerable amount of finances for career education in primary and secondary school, it is mainly focused on motivation instead of knowledge and skills.

REFERENCES Bynner, J & Parsons, S (2002). Social Exclusion and the Transition from School to Work: The Case of Young People Not in Education, Employment, or Training (NEET). Journal of Vocational Behaviour. Vol 60, Pg 289-309.

Furlong, A & Cartmel, F (1997). Young People and Social Change. UK: Open University Press.

Inui, A et al (2005). Precarious Youth and its Social/Political Discourse: Freeters, NEET’s and Unemployed Youth in Japan. Social Work & Society, Vol 3, iss 2, pg 73-100.

Robson, K (2008). Becoming NEET in Europe: A Comparison of Predictors and Later-Life Outcomes. USA: Global Network on Inequality Mini-Conference.

Webter, C et al (2004). Social exclusion, young adults and extended youth transitions. UK: Joseph Rowntree Foundation by The Policy Press.

White Paper on youth 2008 in Japan. http://www8.cao.go.jp/youth/english/whitepaper/2008/pdf/1-2-3.pdf [accessed 17/03/11] translated from Japanese.

Yardley, E (2009). Teenage Mothers’ Experiences of Formal Support Services. Journal of Social Policy (2009), 38: 241-25