Safety Factors Predictive of Job Satisfaction and Job Retention Among Home Healthcare Aides

Transcript of Safety Factors Predictive of Job Satisfaction and Job Retention Among Home Healthcare Aides

Safety Factors Predictive of Job Satisfactionand Job Retention Among HomeHealthcare Aides

Martin F. Sherman, PhDRobyn R. M. Gershon, MT, MHS, DrPHStephanie M. Samar, BAJulie M. Pearson, BAAllison N. Canton, BAMarc R. Damsky, MPH

Objectives: Although many of the well known work characteristicsassociated with job satisfaction in home health care have been docu-mented, a unique aspect of the home health care aides’ (HHA) workenvironment that might also affect job satisfaction is the fact that theirworkplace is a household. To obtain a better understanding of thepotential impact of the risks/exposures/hazards within the householdenvironment on job satisfaction and job retention in home care, werecently conducted a risk assessment study. Methods: Survey data froma convenience sample of 823 New York City HHAs were obtained andanalyzed. Results: Household/job-related risks, environmental expo-sures, transportation issues, threats/verbal and physical abuse, andpotential for violence were significantly correlated with HHA jobsatisfaction and job retention. Conclusions: Addressing the modifiablerisk factors in the home health care household may improve jobsatisfaction and reduce job turnover in this work population. (J OccupEnviron Med. 2008;50:1430–1441)

A lthough home care has historicallyreceived little public attention, rapiddemand for services and increasingrecognition of its critical role in theUS health care system is raising itsprofile.1 With over one millionworkers, home health care is a largeand fast growing sector.2 By 2016, itis projected that the number of homecare workers will grow to 1,170,935,an increase of 48.7%, making thisone of the fastest growing occupa-tions in the United States.2 Theworkforce is mainly comprised ofparaprofessionals, specifically, per-sonal and home care aides and homehealth aides (HHAs). HHAs providehealth-related care, such as adminis-tering oral medications and checkingthe patient’s vital signs, in additionto helping with such daily tasks asbathing, toileting, eating, ambulatingand transferring, as well as house-work. Home care work, typicallyphysically and emotionally demand-ing, is also low paying, with a na-tionwide average hourly wage of$9.66 and annual salary of $20,100.1

In addition, employee benefits forhome care workers may be limited;an estimated 32% lack medical in-surance.3 Combining these issues ofdemanding work and poor wages, itis not surprising that many states arenow experiencing a shortage ofhome care workers.4

Working Conditions inHome Care

Long work hours are common inhome care, as many workers com-mute long distances (frequently us-

From the Department of Psychology (Dr Sherman), Loyola College, Baltimore, MD; MailmanSchool of Public Health (Dr Gershon, Ms Samar, Ms Pearson, Ms Canton), Columbia University, NewYork, NY; and Mobile Health Management Services, Inc. (Mr Damsky), New York, NY.

Address correspondence to: Robyn R. M. Gershon, MT, MHS, DrPH, Columbia University,Mailman School of Public Health, 722 West 168th Street, Suite 1003, New York, NY 10032; E-mail:[email protected].

Copyright © 2008 by American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine

DOI: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31818a388e

1430 Safety Factors Predictive of Job Satisfaction and Retention • Sherman et al

ing mass transportation) and oftenhave second or even third jobs. Pro-viding care to patients with complexphysical and mental needs without,in some cases, easily accessible sup-port and necessary supplies can betrying for even the most seasonedworker. Although adverse workcharacteristics associated with homecare have been shown to be stronglyassociated with job satisfaction(which is highly correlated with jobretention), one aspect of home carethat has not received much attentionis the impact of various householdconditions on home care workers’job satisfaction and job retention.5–9

Because of their job duties, homecare workers may be at risk of expo-sure to the numerous occupationalhazards associated with health carein general, such as ergonomic haz-ards, blood and body fluid exposuresand workplace violence. The riskassociated with these hazards may beincreased in home care for a numberof reasons, including lack of regula-tory oversight, minimal supervisoryand peer support, limited access tohealth and safety professionals, andsuboptimal safety equipment andsupplies. In addition, since theirworkplace is also a household, homecare workers may also be exposed tohousehold related hazards, such astoxic substances exposures (eg, leadpaint), fire safety hazards and house-hold allergens, as well as interper-sonal violence and abuse, whichmight present additional risk to homecare workers.

Information about occupationalhealth hazards in the home care settinghas primarily come from anecdotaland qualitative reports that classifyhazards into two major categories: vi-olence or the threat of violence andunsanitary household conditions. Re-cent analysis by Markkanen et al, ofqualitative data collected during fo-cus groups and in-depth interviewsof home health care nurses and aidesidentified two broad areas of hazards:personal safety hazards and environ-mental contaminants.10 The authorsalso noted that unlike facility-based

nurses and aides, home health careproviders may have to contend withsudden disruptions from pets, chil-dren, and family members. Similarfindings have been reported by Ken-dra et al, who found that home healthcare administrators and staff oftencited numerous safety concerns in-cluding risk of physical and emo-tional injury, fear of contractingcommunicable diseases, loss of prop-erty, long commutes, exposure tohigh-crime areas, inappropriate pa-tient or caregiver behavior andevening assignments.11 The authorsconcluded that the home health carework environment may be both un-predictable and potentially danger-ous. Kendra et al, also explored theeffect these threats might have onpatient care.11 Sixty-eight percent ofthe home health care staff in theirstudy reported that they wouldshorten their patient visit if they feltunsafe in a home.11 These staffmembers also reported that theycompleted their visits “as soon aspossible.” Kendra et al, suggestedthat when visits were completed “assoon as possible,” patient care re-sponsibilities may be neglected.11

In light of these findings, and inconsideration of the growing prob-lems of shortages and retention ofhome care workers, a quantitativeassessment of the contribution ofhousehold/job-related risk factors tojob satisfaction and job retention wasconducted.

Materials and Methods

ProceduresA health and safety survey was

constructed following extensive de-velopmental steps, including in-depthinterviews, focus groups, cognitiveinterviews and pilot testing. The final58-item survey included items thataddressed the following: demograph-ics of the home health care worker,job-related variables (including level/type of care provided and potentialoccupational health hazards), the useof and training on safety devices,potential household health hazards,

job satisfaction and job retention. Forthis study, analyses were limited todemographics, household/job-relatedvariables, and job satisfaction andjob retention variables. The surveywas designed to be completed within30 minutes and was prepared in En-glish at a 6th grade reading level tofacilitate its rapid completion. Thesurvey responses were primarily cat-egorical, although some items had4–5 point Likert-type scale responsechoices and several items were open-ended. (Please contact the corre-sponding author for a copy of thequestionnaire and code book.)

Because of the well-establisheddifficulty in surveying home healthcare workers and the additional chal-lenges in recruitment of persons forwhom English may be a second lan-guage, as is the case for many homecare paraprofessionals, an in-personrecruitment strategy was employed.To facilitate this, a collaborative re-lationship was formed with an oc-cupational health organization thatconducts mandatory health assess-ments and screenings for home careagencies throughout New York City.In 2007, recruitment of participantstook place in the organization’s wait-ing rooms, in conveniently locatedoffices that were easily accessible tothe New York City-based researchteam. Participants could complete thestudy questionnaire in private areasadjacent to the waiting rooms. In somecases, the data collector helped to fa-cilitate the survey administration byreading the questions aloud; however,data collection was primarily self-administered. The incentive for par-ticipation was a single one-dollarscratch-off New York State lotteryticket and enrollment into a lotterydrawing for a $25 gift card prize(chance of winning: 1:100). Al-though the survey was anonymous,each participant was asked to sign aninformed consent form and all pro-cedures involving subject participa-tion had the prior approval of theColumbia University InstitutionalReview Board.

JOEM • Volume 50, Number 12, December 2008 1431

Questionnaire Constructsand Items

Demographic and Job-RelatedVariables. Gender, age, primary lan-guage, tenure as a home health careworker, union membership, hourstraveling to work each day, hoursworked per week, number of patientsserved per week, type of housingwhere patients live (apartment vsnonapartment), setting (urban vs ru-ral), age of patient (elderly, adult,child) and type of care (short-term vslong-term; definitions of short-termand long-term care were left up to theparticipants) were collected for de-scriptive purposes and as potentialcontrol variables.

Major Independent Variables.Two items specifically addressedthreats to personal safety and verbaland/or physical abuse. Participantswere asked “Have you ever feltthreatened (for your personal safety)at any time during your career inhome care (even on the way to apatient’s home)?” [Perceived Threatto Personal Safety], with a score of 0or 1, with 1 indicating the experienceof threat. Participants who indicatedfeeling threatened could also identifywho or what made them feel threat-ened (ie, client, client’s family, cli-ent’s neighbors, and client’s pet).(This second part of PerceivedThreat to Personal Safety was notused in scoring this variable; how-ever, it served to clarify the source ofthe threat.) In line with the PerceivedThreat to Personal Safety item was aquestion that asked “Have you everexperienced any of the following inhome care: 1) verbal abuse and/or 2)threat of physical harm?” [VerbalAbuse/Threat of Physical Harm],with scores ranging from 0 to 1, 0.5indicating either verbal abuse orthreat of physical harm and 1 indi-cating the experience of both. Homecare paraprofessionals’ exposures to10 environmental contaminants/irritants were assessed via a checklist(“At the clients’ homes, are you orhave you been exposed to: air pollu-tion, animal hair, bed bugs, cigarette

smoke, cockroaches, excessive dust,irritating chemicals, mice/rats, mold/dampness, peeling paint?”) and werescored 1 (checked) or 0 (not checked).Twenty-three household/job-relatedconditions that could be consideredbothersome (and potentially risky) tohome care workers were also assessedvia a checklist (“What conditions, ifany, bother you about your current job:risk of exposure to contagious dis-eases, unsanitary conditions in home,unsafe conditions in home, lack ofneeded equipment, neighborhoodcrime, patient’s family members, pa-tient’s neighbors, drug use in home,guns in the home, aggressive pets,demanding patients, heavy patient lift-ing, travel-related problems, cost oftransportation, parking/traffic prob-lems, racial discrimination, messyhome, temperature extremes, poorlighting, loud noises, dealing withRegistered Nurses, understaffing, andheavy weight of the visit bag?”). Thesewere scored 1 (checked) or 0 (notchecked).

Although all of the major indepen-dent variables were considered po-tentially independent contributors inexplaining variance of the major out-come variables, it was decided toempirically determine whether all ofthe items that were subsumed withineach scale actually “belonged” to theappropriate scale. For instance,would a total score of the household/job-related conditions be as useful inpredicting job satisfaction and jobretention as new identified subscalesor factors? In addition, it was notclear how different the environmen-tal contaminants/irritants were fromthe household/job-related conditions.Furthermore, it was not clear whetherthe Perceived Threat to PersonalSafety and the Verbal Abuse/Threatof Physical Harm items were dis-tinct; that is, would the PerceivedThreat to Personal Safety item andthe Verbal Abuse/Threat of PhysicalHarm item be correlated with oneanother and would the two itemsbehave just like other potential risk/exposure/hazard items (environmen-tal contaminants/irritants and house-

hold/job-related conditions)? In orderto determine if data reduction couldbe accomplished, a principal compo-nent analysis was undertaken. Thecriteria for determining the numberof factors to be used in the analysiswere: 1) factors needed to have eigenvalues (Kaiser criterion) over 1, and 2)factors needed to fall above the debrisline in a Scree plot. In addition, indi-vidual items had to load on a factorat a value of 0.40 or higher. Further-more, it was required that Bartlett’sTest of Sphericity be significant inorder to ensure that the correlationmatrix was not an identity matrix andthat the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Mea-sure of Sampling Adequacy wasclose to 1.0 to reflect that a principalcomponent analysis would be usefulin grouping variables into a smallerset of underlying factors.

Major Outcome Variables. JobSatisfaction and Job Retention wereassessed using two questions: 1) “Allin all, how satisfied would you sayyou are with your job?” with re-sponses ranging from “not at all sat-isfied”[0], “somewhat satisfied” [1],“satisfied” [2], to “very satisfied”[3]; 2) “For any reason, are youplanning to leave home health carewithin the next 12 months?” withthree response choices: “yes,” [0],“maybe”, [1], and “no.”[2]. Thushigher scores on both Job Satisfac-tion and Job Retention items re-flected greater satisfaction with thejob and a lower likelihood of leavingthe profession, respectively.

AnalysisAll variables were first explored

by examining the raw score fre-quency distributions. General de-scriptive statistics were computed,including the calculation of per-centages for frequency responsecategories, and means and standarddeviations for continuous responsevariables. The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient wasused to assess pair-wise relationsamong the variables. Predictor vari-ables were either continuous (eg, ageof participant) or dichotomized (eg,

1432 Safety Factors Predictive of Job Satisfaction and Retention • Sherman et al

gender). When a predictor variablewas dichotomized, the Point-biserialcorrelation coefficient was calcu-lated. The bivariate relations revealthe linear associations among thevariables in isolation from any of theother variables. Thus, if two predic-tors are correlated with one another,the bivariate assessment cannot iden-tify the separate and unique associa-tion that each variable has with theoutcome variable. In order to deter-mine the unique contribution of eachpredictor variable, a multiple regres-sion analysis, utilizing the least squaresmethod, was used. This method allowsfor the determination of the degree ofexplanatory contribution of each pre-dictor in accounting for variance of theoutcome variable. Standardized par-tial regression coefficients (�s) werecalculated. Values of � can rangefrom �1 to � 1 (when assumptionsare met) and the closer this index isto the absolute value of 1, the stron-ger the contribution of the specifiedpredictor variable. The total propor-tion of variance accounted for by allof the predictor variables in the out-come variable was assessed by themultiple correlation squared. This in-dex is the correlation squared be-tween the linear combination of thepredictor variables and the outcomevariable. Values of 0.01, 0.09, and0.25 are typically representative ofweak, moderate, and strong relations,respectively.12 All of the statisticalassumptions for conducting correla-tions and for multiple regressionanalysis (ie, normality of the residu-als, homogeneity of the residuals,linearity of the residuals, and outlierdetection) were ascertained prior tothe analysis. Level of significancewas established at an � level of 0.05,two-tailed. Analyses were conductedusing SPSS version 16.0.2.13

Results

Response RateA total of 1561 participants com-

pleted the questionnaire. Among the1561 participants, 823 indicated thatthey were home health care aides

(HHAs), 530 indicated they werepersonal care workers/home atten-dants, 142 indicated they were both,and 66 did not indicate their titles.These groups were compared on allstudy variables and were found to bedifferent on many key variables (eg,age, tenure, number of patients, unionmembership, number of environmen-tal containments/irritants, number ofhousehold/job related risks, feelingthreatened); hence, it was decided toexamine the largest group of respon-dents for this paper, the HHAs. Unfor-tunately, the overall response ratecould not be determined because itwas not exactly known how manysubjects were available for samplingand what percentage of those ap-proached volunteered.

DemographicsThe sample of HHAs (N � 823)

was comprised primarily of women(93.1%), with a mean age of 41.29years (Table 1). Over 50% of theHHAs provided care to one patientper week while working an averageof about 35 hours per week. Morethan 60% of the respondents hadworked as a HHA for 4 or moreyears. Over 58% of HHAs reportedbeing members of a union. EachHHA spent about 2 hours commut-ing per day. Close to 76% of thepatients lived within city limits and amajority (50.7%) lived in apart-ments. A majority of the patientswere elderly and over 56% of allpatients required long-term care.

Safety Risks/Exposures/HazardsViolence and threat of violence by

a patient, the patient’s family, pa-tient’s pets or by a patient’s neigh-bors was common. Approximately26.2% of the HHAs reported thatthey had experienced some form ofperceived threat to personal safety.Of those that felt personally threat-ened, 57.9% felt threatened by thepeople who lived in their client’sneighborhood, 34.7% felt threatenedby their client’s family, 30.1% by theclient, and 19% by their client’s pets.More than 20% all of the HHAs

reported verbal abuse only, 1.8% re-ported physical threats only, and6.3% reported both verbal and phys-ical threats.

In order to determine whether the35 items (Perceived Threat to Per-sonal Safety [number of items (n) �1], Verbal Abuse/Threat of PhysicalHarm [n � 1], Environmental Con-taminants/Irritants [n � 10], andHousehold/Job-Related Risks [n �23]) were assessing different types ofsafety risks/exposures/hazards, aPrincipal Component analysis wasconducted with an oblique rotation(with the assumption that the discov-ered factors would be correlated withone another). Barlett’s Test of Sphe-ricity was significant (Chi Squared �6610.36, P � 0.001) and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of SamplingAdequacy was 0.915, indicating thatthe data were satisfactory for thistype of analysis. An examination ofthe eigen values and Scree plot re-vealed that eight factors (ie, domainsof safety risks/exposures/hazards)could be identified which accountedfor 52.47% of the variance. Thisvalue would be considered “accept-able” according to Merenda whostated that “the proportion should beat least 0.50 [50%]. In that way, itcan be concluded that the factors orcomponents explain as much of thevariance as they fail to explain”.14

The internal consistency of each fac-tor was assessed using Cronbach’salpha coefficient (�). Factor I waslabeled Household/Job-Related Risks I(23.94% of the variance accountedfor and Cronbach � � 0.85 [95%CI � 0.84–0.86]) and consisted often items (scored 1 or 0 for eachitem) from the Household/Job-Related Risks Checklist. Items andtheir loadings were: unsanitary con-ditions in the home setting [0.77],unsafe conditions in the home [0.74],risk of exposure to contagious dis-eases [0.70], messy home/clutter[0.69], racial or ethnic discriminationfrom the client or client’s family[0.61], temperature extremes [0.59],demanding clients [0.59], client’sfamily [0.54], neighborhood crime

JOEM • Volume 50, Number 12, December 2008 1433

[0.48], and heavy client lifting[0.47]. Factor II was labeled Envi-ronmental Exposures (7.45% of thevariance accounted for and Cronbach

� � 0.85 [95% CI � 0.83–0.86])and consisted of all 10 items (scored1 or 0 for each item) from the Envi-ronmental Contaminants/Irritants

Checklist. Items and their loadingswere: excessive dust [0.71], mold/dampness [0.71], mice/rats [0.70],cockroaches [0.68], peeling paint[0.67], cigarette smoke [0.62], ani-mal hair [0.61], air pollution [0.57],irritating chemicals [0.53], and bedbugs 0.45]. Factor III was labeledTransportation Issues I (4.21% of thevariance accounted for and Cronbach� � 0.53 [95% CI � 0.46–0.59])and consisted of two items (scored 1or 0 for each item) from the House-hold/Job-Related Risks Checklist.Items and their loadings were: costof transportation [0.77] and travel-related problems [0.73]. Factor IVwas labeled Household/Job-RelatedRisks II (3.74% of the variance ac-counted for and Cronbach � � 0.50[95% CI � 0.43–0.55]) and con-sisted of three items (scored 1 or 0for each item) from the Household/Job-Related Risks Checklist. Itemsand their loadings were: under-staffing [0.74], heavy weight of visitbag [0.73], and loud/irritating noisein the home setting [0.58]. Factor Vwas labeled Threatened/Verbal andPhysical Abuse (4.50% of the vari-ance accounted for and Cronbach� � 0.62 [95% CI � 0.56–0.67])and consisted of two items: Per-ceived Threat to Personal Safety[loading � 0.63] and Verbal Abuse/Threat of Physical Harm [loading �0.59] and scored 1 or 0, and 1, 0.5,and 0, respectively. Factor VI con-sisted of a single item (scored 1 or 0)from the Household/Job-relatedRisks Checklist. The factor was la-beled Transportation Issue II and ac-counted for 3.28% of the variance.The item was parking/traffic prob-lems [loading � 0.77]. Factor VIIalso consisted of a single item(scored 1 or 0) from the Household/Job-related Risks Checklist. The fac-tor was labeled Client’s Neighborsand accounted for 3.23% of the vari-ance. The item that loaded on thisfactor was “Client’s Neighbors”[loading � 0.48]. The last factor,Factor VIII (3.12% of the varianceaccounted for and Cronbach � �0.60 [95% CI � 0.55–0.64]) con-

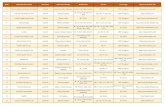

TABLE 1Description of the Sample, Home Healthcare Aides (N � 823)

Characteristics Number (%) Reporting

GenderFemale 766 (93.1)Male 39 (4.7)Missing 18 (2.2)

Age x� � 41.29 yrSD� � 11.41

Primary language spokenEnglish 716 (87.0)Spanish 145 (17.6)Russian 15 (1.8)Chinese 2 (0.2)Other 102 (12.4)

Tenure as a home healthcare aide �1 yr � 38 (4.8)1–3 yrs � 273 (34.2)4–6 yrs � 185 (23.6)7� yrs � 303 (37.9)

Hours worked in home care (per week) x� � 34.54 hrSD� � 18.42

Number of patients seen (per week) 1 � 396 (51.1)2–3 � 344 (44.4)

4� � 35 (4.5)Union affiliation

Union member 478 (58.1)Non-union member 326 (39.6)Missing 19 (2.3)

Daily commute time (hr) x� � 2.04 hrSD� � 1.32

Patient residence typeApartment building only 417 (50.7)House only 128 (15.6)House/apartment building 90 (10.9)Assisted living/nursing home 50 (6.1)Assisted living/nursing home, apartment building 26 (3.2)House, assisted living/nursing home/apartment building 30 (3.6)Other-including combinations of the above 36 (4.4)Missing 46 (5.6)

Patient residence settingUrban 621 (75.5)Suburban 50 (6.1)Rural 13 (1.6)Missing 139 (16.9)

Patient makeupElderly only 427 (51.9)Adults only 99 (12.0)Elderly and adult 86 (10.4)Children only 12 (1.5)Elderly/adult/children 24 (2.9)Some combination of the above 13 (1.6)Missing 162 (19.7)

Type of careLong term 465 (56.5)Short term 122 (14.8)Long term and short term 85 (10.3)Missing 151 (18.3)

Column numbers (and percentages) may not add to total N (or 100%) due to missingvalues or multiple responses.

1434 Safety Factors Predictive of Job Satisfaction and Retention • Sherman et al

sisted of three items (scored 1 or 0for each item) from the Household/Job-related Risks Checklist. The fac-tor was labeled Potential for Vio-lence and the items were (and theirloadings): guns in the home [0.73],drug use in the home [0.69], andaggressive pets [0.59]. There weretwo other items that loaded 0.40 onthis factor (lack of needed equipmentor supplies and poor lighting in thehome setting) but these were not

included because they did not makecomplete conceptual sense with therest of the items, therefore they wereomitted from any further analysis.One other item from the Household/Job-related Risks Checklist that didnot load on any of the eight factorswas “Dealing with RNs.”

The frequency of responses for allitems in each of the safety risks/exposures/hazards factors are pre-sented in Table 2. Environmental

Exposure was the most frequentlyreported type of safety risks/expo-sures/hazards, with cockroaches, cig-arette smoke and mice/rats the mostoften-cited sources. Reports of ver-bal, physical or both types of abuseand feeling threatened were alsocommon. In order to obtain a per-spective in regard to the absolutemean amount of the safety risks/exposures/hazards, all factors weredivided by the number of items thatwere contained within the factor, re-sulting in a mean factor score. Thisresulted in the number of items perfactor being equated so that compar-isons could be made among the fac-tors. Scores could range from 0 to 1per factor—the higher the score thehigher the number of participantswho endorsed the items that made upthe factor. A repeated measures anal-ysis of variance was conducted toexamine the differences among thefactors (a comparison of the factorsin terms of the mean amount ofendorsement). Results of the analysisindicated that the factors were statis-tically different, Hotelling’s TraceF(7, 816) � 74.96, P � 0.001 (Fig.1). Post-hoc pair-wise comparisons(utilizing the Bonferroni Correctionfor multiple comparisons) revealedthe following from the most commonto the least common safety risks/exposures/hazards: Factor V (Threat-ened/Verbal and Physical Abuse) �Fac-tor II (Environmental Exposures)�Factor III (Transportation Issues I)and Factor I (Household/Job RelatedRisks I) �Factor VIII (Potential forViolence) and Factor VII (Client’sNeighbors) �Factor VI (Transporta-tion Issue II) and Factor IV (House-hold/Job Related Risks II). It is clearthat the two factors that stand out themost were Factors V (Threatened/Verbal and Physical Abuse) and II(Environmental Exposures).

Job Satisfaction andJob Retention

For Job Satisfaction, 64% of theHHAs reported responses indicating

TABLE 2Frequencies of the Eight Major Safety Risks/Exposures/Hazards FactorsExperienced by Home Healthcare Aides (N � 823)

Health Risks and Safety HazardsNumber (%)Reporting

Number (%)Reporting at Least OneRisk/Exposure/Hazard

Factor I—Household/Job-Related Risks I 328 (39.9)Messy home 163 (19.8)Demanding clients 140 (17.0)Heavy client lifting 132 (16.0)Clients family 129 (15.7)Unsanitary conditions in the home 113 (13.7)Neighborhood crime 88 (10.7)Exposure to contagious diseases 83 (10.1)Racial discrimination from client or family 77 (9.4)Temperature extremes in client home 75 (9.1)Unsafe conditions in home 53 (6.4)

Factor II—Environmental Exposures 455 (55.3)Cockroaches 291 (35.4)Cigarette smoke 255 (31.0)Mice/rats 201 (24.4)Animal hair 183 (22.2)Excessive dust 173 (21.0)Irritating chemicals 134 (16.3)Peeling paint 125 (15.2)Mold/dampness 90 (10.9)Air pollution 81 (9.8)Bed bugs 54 (6.6)

Factor III—Transportation Issues I 174 (21.1)Travel-related problems 115 (14.0)Cost of transportation 109 (13.2)

Factor IV—Household/Job-Related Risks II 56 (6.8)Loud irritating noises in the home 33 (4.0)Under-staffing 19 (2.3)Heavy weight of visit bag 19 (2.3)

Factor V—Threatened/Verbal and PhysicalAbuse

320 (38.9)

Experience of verbal, physical or bothabuse

243 (29.5)

Ever felt threatened 216 (26.2)Factor VI—Transportation Issues II 24 (2.9)

Parking/Traffic problems 24 (2.9)Factor II—Client’s Neighbors 32 (3.9)

Client’s neighbors 32 (3.9)Factor VIII—Potential for Violence 80 (9.7)

Aggressive pets 52 (6.3)Drug use in the home 44 (5.3)Guns in the home 17 (2.1)

JOEM • Volume 50, Number 12, December 2008 1435

“very satisfied or satisfied” and 36%reported “somewhat satisfied” or“not satisfied.” With respect to JobRetention, 18% reported that theywere planning to leave their job inthe next 12 months. Twenty-five per-cent reported that they might leavetheir job and 57% reported that theywere planning to stay with their cur-rent job.

As shown in Table 3, Job Satisfac-tion was positively correlated withage (older age), tenure (greater num-ber of years worked), and unionmembership. Length of time com-muting to work per day, hoursworked per week, caseload per week,type of housing, type of community(eg, rural vs urban), patient charac-teristics and job duties performed

were not statistically related to JobSatisfaction. Moderate-sized nega-tive correlations were found betweenJob Satisfaction and Factor V(Threatened/Verbal and PhysicalAbuse), Factor II (EnvironmentalExposures), and Factor I (House-hold/Job-Related Risks I). Somewhatweaker correlations were found be-tween Job Satisfaction and Factor III(Transportation Issues I), Factor VIII(Potential for Violence), Factor IV(Household/Job-Related Risks II),and Factor VII (Client’s Neighbors).Factor VI (Transportation Issue II)was not statistically related to JobSatisfaction. Turning to Job Reten-tion, the results practically mirrorimaged the results found for JobSatisfaction. Job Retention was pos-itively correlated with age (olderage) and tenure (greater number ofyears worked). Union membership,length of time commuting to workper day, hours worked per week,caseload per week, type of housing,type of community (eg, rural vs ur-ban), patient characteristics and jobduties preformed were not statisti-cally related to Job Retention. JobRetention was negatively related tothe same seven factors as Job Satis-faction and for the most part to thesame degree (Table 3). In addition,Job Satisfaction and Job Retentionwere positively correlated, r � 0.40,P � 0.001.

In order to determine the relativeand unique contributions of variablesthat were significantly related to theoutcome measures, hierarchical mul-tiple regression analyses were con-ducted. In step one, using forcedentry (age of HHA, years worked inhome health care, and union mem-bership), only union membership re-mained significant in the equationand explained 2.3% of Job Satisfac-tion variance. Forward entry wasthen used with the seven factors thatwere found to be significantly relatedto Job Satisfaction in the bivariateanalyses. The final step (step six)revealed that five of the seven factorsentered the regression equation. Ascan be seen in Table 4, the final

Fig. 1. Factor I � Household/Job-Related Risks; Factor II � Environmental Exposures; FactorIII � Transportation Issues I; Factor IV � Household/Job-Related Risks II; Factor V �Threatened/Verbal and Physical Abuse; Factor VI � Transportation Issue II; Factor VII �Client’s Neighbors; Factor VIII � Potential for Violence.

TABLE 3Predictors of Job Satisfaction and Job Retention

Job Satisfaction Job Retention

Gender (female �) 0.04 0.06Age 0.12** 0.17***Tenure 0.09* 0.06Union membership (Yes �) 0.12** 0.11**Travel time 0.04 �0.03Hours worked �0.06 0.02Number of patients �0.07 �0.02Type of housing (apartment vs nonapartment) 0.02 0.02Setting (city vs non-city) 0.01 0.00Type of Patient (elderly vs nonelderly) 0.03 0.01Type of Care (long term vs non-long term) 0.03 0.02Factor I—Household/Job-Related Risks I �0.24*** �0.17***Factor II—Environmental Exposures �0.25*** �0.19***Factor III—Transportation Issues I �0.18*** �0.11**Factor IV—Household/Job-Related Risks II �0.11** �0.13***Factor V—Threatened/Verbal and Physical

Abuse�0.30*** �0.22***

Factor VI—Transportation Issues II–Parking 0.03 0.00Factor VII—Clients’ Neighbors �0.10** �0.07Factor VIII—Potential for Violence �0.12** �0.17***

*P � 0.05; **P � 0.01; ***P � 0.001.

1436 Safety Factors Predictive of Job Satisfaction and Retention • Sherman et al

model accounted for 14.8% of theJob Satisfaction variance. The factorthat carried the most “impact” asdetermined by the standardized �coefficient was Factor V (� ��0.188: Threatened/Verbal andPhysical Abuse), whereas Factors I,II, and III had less but statisticallysignificant “impacts” on Job Satis-faction. It is interesting to note thatFactor VI (Transportation Issue II)changed its directional relation withJob Satisfaction. This is not unusualwhen many factors are entered into aregression equation. That is, in the

bivariate analysis, Transportation Is-sue II was negatively correlated withJob Satisfaction, but when the otherfactors were controlled, Transporta-tion Issue II now became positivelycorrelated with Job Satisfaction. It isunclear why this occurred, but thisfactor may be correlated with someother unmeasured variable that actu-ally carries the relation.

In regard Job Retention, only agewas significantly related to Job Reten-tion in step one (Table 5). Forwardentry of the seven factors resulted inonly two factors entering the equation.

Again, Factor V (Threatened/Verbaland Physical Abuse) entered the re-gression and carried the most “impact”(Standardized � � �0.189) and wasfollowed by Factor VIII (Potential forViolence). No other factors entered themodel after this step. The full modelexplained 9.3% of the Job Retentionvariance.

In order to determine whether JobSatisfaction would mediate the rela-tion between Factors V and VIII andJob Retention, a third regressionanalysis was conducted (Table 6).The first step in this analysis wassimilar to the previous analysis onJob Retention (the results are slightlydifferent because of a smaller sampledue to missing values). Forward en-try of Job Satisfaction on step tworesulted in a significant relation be-tween Job Satisfaction (� � 0.377)and Job Retention and the modelaccounted for 16.8% of the variancein Job Retention. Forward entry of thefactors resulted in Factors V (Threat-ened/Verbal and Physical Abuse) andVIII (Potential for Violence) enteringthe regression equation. An examina-tion of the standardized �s indicatethat the � coefficient for Factor Vwas reduced by 50% (from �0.189to �0.092) from the previous analy-sis where Job Satisfaction was not inthe equation. This suggests that JobSatisfaction potentially was acting asa partial mediator between the rela-tion of Factor V (Threatened/Verbaland Physical Abuse) and Job Reten-tion. The standardize � coefficient forFactor VIII did not change from theprevious analysis to the current analy-sis, suggesting that Job Satisfactiondoes not mediate the relation betweenFactor VIII and Job Retention.

DiscussionThe current study revealed that

Job Satisfaction and Job Retentionwere related to a number of safetyrisks/exposures/hazards among oursample of HHAs. With respect to thedemographic variables, it was foundthat age and union membership werepositively related both to Job Satis-faction and Job Retention, whereas

TABLE 4Summary of Regression Analysis for Safety Risks/Exposures/Hazards Factorsand Demographic Variables in Predicting Job Satisfaction

Variable B SE B � P R2 Fchange P

Step One 0.023 4.79 �0.003Age 0.007 0.004 0.082 �0.057Years worked 0.006 0.008 0.034 �0.427Union membership 0.180 0.078 0.094 �0.022

Full model (Step six) 0.148 4.35 �0.04Age (�) 0.005 0.003 0.056 �0.164Years worked (�) 0.010 0.007 0.055 �0.184Union membership 0.162 0.074 0.085 �0.028Factor V �0.269 0.063 �0.188 �0.001Factor I �0.053 0.024 �0.105 �0.026Factor III �0.163 0.063 �0.104 �0.010Factor VI 0.410 0.194 0.082 �0.035Factor II �0.035 0.017 �0.095 �0.037

Full Model F (8, 616) �13.42, P � 0.001

N � 625.Factor I indicates Household/Job-Related Risks; Factor II, Environmental Exposures;

Factor III, Transportation Issues I; Factor V, Threatened/Verbal and Physical Abuse; Factor VI,Transportation Issues II (Parking).

Union membership (0 � No, and 1 � Yes).

TABLE 5Summary of Regression Analysis for Safety Risks/Exposures/Hazards Factorsand Demographic Variables in Predicting Job Retention

Variable B SE B � P R2 Fchange P

Step one 0.031 9.13 �0.001Age 0.011 0.003 0.149 �0.001Union membership 0.121 0.068 0.074 �0.076

Full Model (Step three) 0.093 8.34 �0.004Age (�) 0.009 0.003 0.128 �0.002Union Membership 0.129 0.066 0.079 �0.052Factor V �0.228 0.051 �0.189 �0.001Factor VIII �0.125 0.043 �0.121 �0.004

Full Model F (4, 566) �14.59, P � 0.001

Factor V indicates Threatened/Verbal and Physical Abuse; Factor VIII, Potential forViolence.

Union membership (0 � No and 1 � Yes).

JOEM • Volume 50, Number 12, December 2008 1437

tenure was positively related only toJob Satisfaction. These finding areconsistent with Neal’s theory ofhome health nursing practice.15,16

Neal claims that it typically takes thehome health care worker about 2years to master the logistical andclinical aspects of home care. Al-though Neal recognizes that theadaptive process is not completelylinear and most likely represents athreshold relation (unlike the currentstudy which examined only a linearrelation and which did not have ac-cess to those HHAs that left theprofession), her work suggests thatthose workers who are adaptable willsatisfactorily achieve this stage andthose workers who do not achievethe adaptive stage are the ones mostlikely to leave the home health carefield.15,16 These findings, althoughspecific to nurses, may also have va-lidity for HHAs. Importantly, once thework tasks are mastered and the homecare worker has adapted to the job,aspects related to quality of the workenvironment, in this case the pa-tient’s home, may have importantimplications for ongoing satisfactionwith the job. Much more intensivestudy, with larger and more variedsamples, will help to further eluci-

date factors related to job satisfactionand job retention in the home healthcare setting.

Regarding some of our other find-ings, unsurprisingly, union member-ship was also correlated with bothJob Satisfaction and Job Retention,with those claiming union member-ship reporting greater Job Satisfac-tion and greater likelihood of stayingwith their current job. These findingscorrespond with the notion thatunion activity within an organizationserves to protect the well-being of itsmembers, thus implying that unionmembership may positively influ-ence employees’ job satisfaction andjob retention.17–19

The fact that no significant rela-tions were found between hourscommuting per day, hours workedper week, number of patients perweek, type of housing, type of set-ting, patient characteristics and typeof patient care and job satisfactionand job retention may be a functionof the generally low workloads inour sample. Over fifty percent of theHHAs surveyed provided care to onlyone patient per week and worked anaverage of almost 35 hours per week.

The most compelling and novelfindings of this study are the strong

evidence of the potential impact ofThreatened/Verbal and PhysicalAbuse, Environmental Exposuresand Household/Job-related Risks onboth Job Satisfaction and Job Reten-tion of HHAs. To a lesser degree, butstill contributing statistically in ac-counting for job satisfaction vari-ance, were Transportation Issues,Client’s Neighbors, and Potential forViolence. These same safety risks/exposures/hazards also accounted forvariance in job retention except forClient’s Neighbors. When each ofthe eight major factors (Household/Job-related Risks I [Factor I], Environ-mental Exposures [Factor II], Trans-portation Issues I [Factor III],Household/Job-related Risks II [FactorIV], Threatened/Verbal and PhysicalAbuse [Factor V], Transportation Is-sue II [Factor VI], Client’s Neigh-bors [Factor VII], and Potential forViolence [Factor VIII]) were for-ward entered into a regressionmodel, five Factors (I, II, III, V, andVI) made sizeable contributions toHHAs’ job satisfaction. In total, thefive factors added an additional12.5% of the variance accounted forabove the 2.3% accounted for byage, tenure, and union membership.It is noteworthy that the factor thataccounted for the most uniqueamount of variance in job satisfac-tion was Threatened/Verbal andPhysical Abuse (� � �0.188). Inaddition, this factor also had thehighest mean endorsement across alleight factors (Fig. 1). That is, thisfactor was reported to be more of aconcern (on average) for the largestproportion of HHAs (although theindividual items addressing cock-roaches and cigarette smoke from theEnvironmental Exposures factor hadthe highest level of endorsement forsingle items). The other factors fol-lowing in order of mean endorsementwere: Environmental Exposures (Fac-tor II), Transportation Issues I (Fac-tor III), Household/Job-related RisksI, and Transportation Issue II (FactorVI-Directional change of � weight).Five of the seven factors that wererelated to job satisfaction in the bi-

TABLE 6Summary of Regression Analysis for Safety Risks/Exposures/Hazards Factorsand Demographic Variables in Predicting Job Retention while Controlling forJob Satisfaction

Variable B SE B � P R2 Fchange P

Step one 0.030 8.60 �0001Age 0.010 0.003 0.142 �0.001Union membership 0.128 0.070 0.078 �0.066

Step two 0.168 91.55 �0.001Age (�) 0.007 0.003 0.102 �0.010Union membership 0.057 0.065 0.035 �0.378Job satisfaction 0.322 0.034 0.377 �0.001

Full model (Step four) 0.192 4.91 �0.027Age (�) 0.007 0.003 0.092 �0.019Union membership 0.067 0.064 0.041 �0.300Job satisfaction 0.287 0.035 0.335 �0.001Factor VIII �0.114 0.042 �0.110 �0.006Factor V �0.112 0.050 �0.092 �0.027

Full Model F (5, 551) �26.24, P � 0.001

Factor V indicates Threatened/Verbal and Physical Abuse; Factor VIII, Potential forViolence.

Union membership (0 � No and 1 � Yes).

1438 Safety Factors Predictive of Job Satisfaction and Retention • Sherman et al

variate analysis maintained uniquevariance accounted for in the regres-sion model. It thus appears that jobsatisfaction is potentially multi-determined and that any type of pre-vention or intervention will requiremulti-faceted approaches.

It should also be noted that the35 items of the survey, for the mostpart, factored into well-definedeight domains which should help toorganize our thinking about and un-derstanding of the myriad character-istics of the patients’ households andneighborhoods that may adverselyimpact the worker.

These results also complement animportant body of work by Ellen-becker and Byleckie. They developedand tested a home health care nursejob satisfaction scale that was theo-retically grounded.7 Their 30-itemscale that predicts job satisfaction inhome health care nurses consists ofnine factors; five factors addressedintrinsic job characteristics (eg, au-tonomy, group cohesion) and fourfactors addressed extrinsic character-istics (eg, salary, benefits, stress andworkload).5 Together, the nine fac-tors accounted for 66% of the totalvariance.8 In a more recent publica-tion, Ellenbecker et al, have reporteda refinement of their scale whichnow contains eight subscales (rela-tionship with peers, relationship withorganization, relationship with phy-sician, salary and benefits, stress andworkload, relationship with patients,professional pride, and autonomyand control).20 Although the Ellen-becker revised scale is designed fornurses and not HHAs, these otherwell-defined characteristics of homehealth care work most likely impactHHAs. Although Ellenbecker et al’sscale is very comprehensive it doesnot include the factors that werefound to be related to job satisfactionand job retention in the current study.It may be an advantage to supple-ment Ellenbecker’s scale with thesub-scales that were reported in thecurrent study. Taken together withhousehold/job-related hazards, thispotentially could account for a much

larger proportion of the variance injob satisfaction. However, it is notclear whether the working condi-tions of the HHAs are similar inscope and in intensity to those con-ditions that confront the home healthcare nurse. Future studies that adaptEllenbecker’s scale for the HHAsworkforce may prove to be informa-tive in further delineating the variouscharacteristics of work that impactjob satisfaction among home healthcare workers.

Recognizing the impact that thesefactors may have on job satisfactionis important, but implementingchange to address some of these fac-tors may be a challenge. For instance,the experience of being threatened bya patient, the patient’s family, pa-tient’s pets or by a patient’s neigh-bors was not a rare occurrence in thisstudy. This experience can be allevi-ated to an extent by educating HHAsin terms of handling difficult patientsor family members. Self-defensetraining and use of animal controlmeasures (eg, insisting that aggres-sive pets be secured prior to theHHAs’ arrival) can also help to de-crease the potential threat associatedwith people and/or animals. Accessto cell phones that can directly con-nect to a home base agency or secu-rity force may provide the HHAswith a greater sense of security andthus lessen the perceived threat. Pro-viding HHAs with trained escortswould also serve to increase a senseof security. Environmental exposurespresent more of a challenge in termsof risk reduction. Exposure to pestssuch as cockroaches and mice/rats isdifficult to control because they aremore of a community problem thanhousehold-specific. Exposure to airpollutants and peeling paint can bereduced by implementing environmen-tal controls, but these are generallyoutside the scope of the home caresector. Something agencies could do toimprove the overall quality of the jobmight include the development of aneasy-to-use checklist on householdconditions for initial and periodic as-sessments. This could be coupled with

a list of simple solutions for at leastsome of the problems, such as the useof hand sanitizer gels when handwashing is compromised.

Although it is extremely importantto identify the factors that contributeto job satisfaction, it is also impor-tant to determine whether the samefactors contribute to job retention. Inorder to ascertain this among ourcurrent sample, the same regressiontechnique that was used with jobsatisfaction was utilized with job re-tention. After step one of the regres-sion model where age and unionmembership accounted for 3.1% ofthe variance, only two factors en-tered the regression equation. Thetwo factors which added an addi-tional 6.2% in the variance of jobretention were: Threatened/Verbaland Physical Abuse and Potential forViolence. All of the other factors thatwere related to job retention in thebivariate analyses were no longerstatistically significant. It appearsthat factors that contribute to jobsatisfaction may not contribute di-rectly to job retention. These resultssuggest that certain factors may con-tribute to job satisfaction and that jobsatisfaction may then contribute tojob retention. To test this possibility,a third regression analysis was con-ducted where job satisfaction wasentered on the second step of a re-gression analysis for job retention.This third regression analysis re-vealed that job satisfaction added anadditional 13.8% of the job retentionvariance above the 3.0% that age andunion membership accounted for onthe first step. The final step of thisanalysis had Factors V (Threatened/Verbal and Physical Abuse) and VIII(Potential for Violence) entering theequation which added an additional2.4% of the variance. An examina-tion of the � coefficients revealedthat Factor V had its � coefficientreduced by 50% from the previousanalysis where job satisfaction wasnot part of the equation. This reduc-tion in variance accounted for sug-gests that job satisfaction may beacting as a partial mediator between

JOEM • Volume 50, Number 12, December 2008 1439

the relation of Factor V and job reten-tion. That is, feeling threatened andbeing subjected to verbal and/or phys-ical abuse may contribute to job dis-satisfaction which in turn determineswhether or not an HHA decides toleave his/her current occupation. Sincethe � coefficient did not decrease tozero, Factor V appears to continue tohave not only an indirect effect(through job satisfaction) but also adirect effect on job retention. Thus,even though intervention programsmay impact job satisfaction, this wouldonly be part of the issue. The other partthat would still need to be addressed isthe direct impact of Factor V. Thesame cannot be said for Factor VIII(Potential for Violence). This factorwas not influenced by job satisfaction,and thus maintained its apparent directeffect on job retention. What appearsto be emerging is a complex set ofrelations among multifaceted vari-ables. This study opens the door forfurther investigation into the majordeterminants of job satisfaction andjob retention among HHAs.

LimitationsA number of potential study limi-

tations are acknowledged. First, aswith all cross-sectional designs, cau-sality cannot be ascertained. How-ever, this design is a cost-effectivefirst step upon which more robuststudies can be built. Second, we sam-pled HHAs who volunteered to par-ticipate from only one largely urbancity, thus these results may not begeneralizable to the nationwide pop-ulation of HHAs as a whole or tothose HHAs who do not participatein surveys. Going forward, thesetypes of studies should involve ran-dom sampling of HHAs from othergeographical locations and withmore diverse settings and work pop-ulations. Third, although our surveywas anonymous, we did ask poten-tially sensitive questions (eg, drugsand firearms in the home) and thismay have resulted in participants’providing socially desirable answers.Many of the HHAs may have beenafraid of providing forthright re-

sponses for fear of how this mightaffect their employment status. Thisis an on-going concern with all surveyinstruments that address sensitiveand possibly illegal (and thereforereportable) activities. Fourth, this studydid not examine potential moderatorvariables which may suggest thatsome of the observed relations maybe stronger or weaker for certaingroups of HHAs. Fifth, the outcomemeasures were limited to singleitems tapping job satisfaction and jobretention. It will require future re-search to incorporate multiple as-sessments of each outcome variable.Sixth, measurements of all variableswere gathered via a self-report sur-vey and thus there could be a meth-ods bias. Future research may wantto assess the patient’s perspective onthe factors that may influence thewell-being of the HHA. Obtainingdata from the HHAs’ supervisors andcolleagues would strengthen our un-derstanding of the factors influencingthe job satisfaction and job retentionamong HHAs. Seventh, since a num-ber of the survey items addressedwhether the HHAs had ever been ex-posed to various environmental con-tainments/irritants and whether theHHA had ever felt threatened for anyreason, it is not clear as to whetherthese potential past experiences werein fact influential in the prediction ofjob satisfaction and job retention.Future research should include notonly any exposure from the past butmore importantly should include cur-rent exposures. A final limitation ofthe current study involves the job re-tention variable which was assessed bythe question “For any reason, are youplanning to leave home health carewithin the next 12 months?” Withoutassessing why the HHA planned toleave, it becomes somewhat problem-atic to determine whether the actualintent to leave was in fact related to thevariables that we studied. Future re-search will need to pose questions thatdirectly ask the HHA “If you are plan-ning to leave the profession, pleaseprovide us with the reasons why youwant to leave.”

ConclusionThis study provides new evidence

on the role of the household environ-ment in HHAs’ job satisfaction andjob retention. The study also providesevidence of the close relation be-tween job satisfaction and job reten-tion and shows that job satisfactionmay be a partial mediator betweenthe relation between exposure tothreats and violence and job reten-tion. Additional study is warranted tofurther explore the impact of thehousehold environment on HHAs’health and well-being (eg, mentaland physical health), as well as theeffectiveness of the use of morecomplex models that combine bothhousehold and health care hazards.Additional studies should be con-ducted to assess both of these workcharacteristics as well as the intrinsicand extrinsic work characteristics inthe home care setting as described byEllenbecker et al.20 As noted, itwould be of interest to explore theseissues across other geographic loca-tions and in other types of commu-nities. Eventually, it might provebeneficial for the sector as a whole toconsider the development of bestpractice guidelines for agencies interms of managing adverse house-hold conditions. This might provideimportant guidance, especially tosmaller agencies. The overall effectof addressing adverse conditions,where feasible, may not only im-prove the quality of work life forHHAs but also the quality of patientcare. Additionally, it may help re-duce the burden of high turnover thatmany agencies face. Therefore, theimplementation of interventions thataddress household hazards could po-tentially improve the well-being ofthe HHAs, the care that they provideto their clients, and the stability andproductivity of the agencies that pro-vide these services.

AcknowledgmentsSupported by a grant from the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention/National In-stitute of Occupational Safety and Health (5R01 OH008215-03).

1440 Safety Factors Predictive of Job Satisfaction and Retention • Sherman et al

References1. Department of Health and Human Ser-

vices, Health Resources and Services Ad-ministration, Bureau of Health Professions.Nursing Aides, Home Health Aides, andRelated Health Care Occupations: Na-tional and Local Workforce Shortages andAssociated Data Needs. Available at: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/nursinghomeaid/nursinghome.htm. Ac-cessed February 12, 2008.

2. U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau ofLabor Statistics. Occupational OutlookHandbook, 2008–2009 Edition, Personaland Home Care Aides. December 18,2007. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/oco/ocos173.htm#outlook. AccessedFebruary 12, 2008.

3. Gerrick KJ. An inquiry into unionizinghome healthcare workers: benefits forworkers and patients. Am J Law Med.2003;29:117–138.

4. Denton MA, Zeytinoglu IU, Davies S.Working in clients’ homes: the impact onthe mental health and well-being of vis-iting home care workers. Home HealthCare Serv Q. 2002;21:1–27.

5. Ellenbecker CH. A theoretical model ofjob retention for home health care nurses.J Adv Nurs. 2004;47:303–310.

6. Ellenbecker CH, Byleckie JJ. Agenciesmake a difference in home healthcarenurses’ job satisfaction. Home HealthcNurse. 2005;23:777–784.

7. Ellenbecker CH, Byleckie JJ. HomeHealthcare Nurses’ Job SatisfactionScale: refinement and psychometric test-ing. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52:70–78.

8. Ellenbecker CH, Boylan LN, Samia L.What home healthcare nurses are sayingabout their jobs. Home Healthc Nurse.2006;24:315–324.

9. Waxman HM, Carner EA, BerkenstockG. Job turnover and job satisfactionamong nursing home aides. Gerontolo-gist. 1984;24:503–509.

10. Markkanen P, Quinn M, Galligan C,Chalupka S, Davis L, Laramie A. There’sno place like home: a qualitative study ofthe working conditions of home healthcare providers. J Occup Environ Med.2007;49:327–337.

11. Kendra MA, Weiker A, Simon S, GrantA, Shullick D. Safety concerns affectingdelivery of home health care. PublicHealth Nurs. 1996;13:83–89.

12. Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied MultipleRegression/Correlation Analysis forthe Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1975.

13. SPSS. SPSS [computer program]. Ver-sion 16. Chicago: SPSS; 2008.

14. Merenda PF. A guide to the proper use offactor analysis in the conduct and report-ing of research: pitfalls to avoid. MeasEval Counsel Dev. 1997;30:156–164.

15. Neal LJ. The Neal Model of Home HealthNursing Practice. Glenview, IL: Associ-ation of Rehabilitation Nurses; 1998.

16. Neal LJ. On Becoming a Home HealthNurse: Practice Meets Theory in HomeCare Nursing. Washington, DC: HomeCare University and Home HealthcareNurses Association; 2000.

17. United Domestic Workers. United Do-mestic Workers of America. Available at:http://www.udwa.org/index.htm. Ac-cessed February 12, 2008.

18. American Federation of State, Countyand Municipal Employees. Home Care.Available at: http://www.afscme.org/workers/7000.cfm. Accessed February17, 2008.

19. National Union of Hospital and Health-care Employees. About Us. Available at:http://www.nuhhce.org/about.html. Ac-cessed February 17, 2008.

20. Ellenbecker CH, Byleckie JJ, Samia LW.Further psychometric testing of the HomeHealthcare Nurse Job Satisfaction Scale.Res Nurs Health. 2008;31:152–164.

United States Postal Service

Statement of Ownership, Management, and Circulation1. Publication Title 2. Publication Number 3. Filing Date

Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 1 0 7 6 __ 2 7 5 2 10-01-20084. Issue Frequency 5. Number of Issues Published Annually 6. Annual Subscription Price

Monthly 12 $328.00

7. Complete Mailing Address of Known Office of Publication (Not Printer) (Street, City, County, state, and ZIP+4) Contact Person

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins16522 Hunters Green Parkway TelephoneHagerstown, MD 21740-2116

8. Complete Mailing Address of Headquarters or General Business Office of Publisher (Not printer)

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 530 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106

9. Full Names and Complete Mailing Address of Publisher, Editor, and Managing Editor (do not leave blank)

Publisher (Names and Complete mailing address)

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 530 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106

Editor (Names and Complete mailing address)

Managing editor (Names and Complete mailing address)

Marjorie Spraycar, 605 Worcester Road, Towson, MD 21286-7834

10. Owner (Do not leave blank. If the publication is owned by a corporation, give the name and address of the corporation immediately followed by the names and address of all stockholders owning or holding 1 percent or more of the total amount of stock. If not owned by a corporation, give the names and address of the individual owners. If owned by a partnership or other unincorporated firm, give its name and address as well as those of each individual owner. If the publication is published by a nonprofit organization, give its name and address

Full Name Complete Mailing Address25 Northwest Point Boulevard, Suite 700Elk Grove Village, IL 60007-1030

Attn: Barry S. Eisenberg, MA, CAEExecutive Director

11. Known Bondholders, Mortgages, and other Security Holders Owning or Holding 1 Percent or More Total Amount of Bonds, Mortgages, or Other Securities. If none, check box X None

Full Name Complete Mailing Address

12. Tax Status (For completion by nonprofit organizations authorized to mail at nonprofit rates) (Check one) The purpose, function, and nonprofit status of this organization and the exempt status for federal income tax purposes:

X Has Not Changed During Preceding 12 Months

Has Changed During Preceding 12 Months (Publisher must submit explanation of change with this statement)

(see Instructions on Reverse)

PS Form 3526, September 1998

Paul W. Brandt Rauf, MD, Office of the Dean, UIC School of Public Health, 1603 West Taylor Street, Room 1145, Chicago, IL 60612

American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine

13. Publication Title 14. Issue date for Circulation Data Below

Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine Volume 50, #815 Extent and Nature of Circulation Average No. copies Each Issue No. copies of Single issue

During Preceding 12 Months Published Nearest to Filing Date

a. Total No. copies (Net Press Run) 5,748 5,500(1) Paid/Requested Outside-County Mail Subscription Stated on

b. Paid and/or Form 3541.(Include advertiser's proof and exchange copies) 4,556 4,693Requested (2) Paid In-county Subscriptions (Include advertiser's proof

Circulation and exchange copies) 0 0

(3) Sales Through Dealers and Carriers, Street Vendors,

Counter Sales, and Other Non-USPS Paid Distribution 679 668

(4) Other Classes Mailed Through the USPS 0 0

c. Total Paid and/or requested Circulation (Sum of 15b, (1), (2), (3), and (4)) 5,235 5,361d. Free

Distribution (1) Outside-county as Stated on form 3541 123 144by Mail

(Samples, (2) In-County as Stated on Form 3541 0 0complimentary, and

other free) (3) Other Classes Mailed Through the USPS 0 0

e. Free Distribution Outside the Mail (Carriers or other means) 12 35

f. Total Free distribution (Sum of 15d and 15e) 135 179

g. Total Distribution (Sum of 15c and 15f) 5,370 5,540

h. Copies Not Distributed 378 40

I. Total (Sum of 15g, and h.) 5,748 5,500j. Percent Paid and/or Requested Circulation

(15c. Divided by 15g. Times 100) 97.00% 97.00%

16. Publication of Statement of Ownership

x Publication required. Will be printed in the Vol 50, #12 issue of this publication. Publication not required.

17. Signature and Title of Editor, Business Manager, or Owner Date

I certify that all information furnished on this form is true and complete. I understand that anyone who furnishes false or misleading information on this formor who omits material or information requested on the form may be subject to criminal sanctions (including fines and imprisonment) and/or civil sanctions

(including civil penalties).

Instructions to Publishers

1. Complete and file copy of this form with your postmaster annually on or before October 1. Keep a copy of the completed formfor your records.

2. In cases where the stockholder or security holder is a trustee, include in items 10 and 11 the name of the person or corporation forwhom the trustee is action. Also include the names and addresses of individuals who are stockholders who own or hold 1 percentor more of the total amount of bonds, mortgages, or other securities of the publishing corporation. In item 11, if none, check thebox. Use blank sheets if more space is required.

3. Be sure to furnish all circulation information called for in item 15. Free circulation must be shown in items 15d, e, f.

4. Item 15h., Copies not Distributed, must include (1) newsstand copies originally stated on Form 3541, and returned to the publisher,(2) estimated returns from news agents, and (3), copies for office use, leftovers, spoiled, and all other copies not distributed.

5. If the publication had Periodicals authorization as general or requester publication, this Statement of Ownership, Management, and Circulation must be published; it must be printed in any issue in October or, if the publication is not published during October,

the first issue printed after October.

6. In item 16, indicate the date of the issue in which this Statement of Ownership will be published.

7. Item 17 must be signed.

Failure to file or publish a statement of Ownership may lead to suspension of Periodicals authorization.

PS Forms 3526, September 1998 (Reverse )

JOEM • Volume 50, Number 12, December 2008 1441