"Recording and Identifying European Frontier Deaths"

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of "Recording and Identifying European Frontier Deaths"

© Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2011 DOI: 10.1163/157181611X571259

European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156 brill.nl/emil

Recording and Identifying European Frontier Deaths

Stefanie Grant*Senior Visiting Research Fellow, University of Sussex, UK

AbstractMigrant deaths at EU maritime borders have more often been seen in the context of national border control, than in terms of migrant protection and human rights. The 2009 Stockholm Programme accepted the need for action to avoid tragedies at sea, and to ‘record’ and ‘identify’ migrants trying to reach the EU. But it did not specify how this should be done. There are parallels between these migrant deaths, and deaths which occur in conflict and humanitarian disaster. The principles of human rights and humanitarian law which apply in these situations should be developed to create legal and policy frame-works for use in the case of migrants who are missing or who die on EU sea frontiers. The purpose would be to enable evidence of identity to be preserved, to protect the rights of families to know the fate of their relatives, and to create common national and international procedures.

Keywordsmigrant deaths, maritime frontier deaths, missing persons, EU 2009 Stockholm Programme, migrant rights, recording migrant deaths

Migrant frontier deaths and violations of migrants’ rights at frontiers have tended to be seen as a ‘tragic by-product’ and as ‘unintended side effects’1 of state action to control national borders, prevent irregular migration, and combat interna-tional crime. Too little attention has been given to the migrants themselves, to their protection, or to developing rights-based policies to prevent these deaths. Perhaps as a result, the issue has been seen largely in isolation from other situa-tions involving significant loss of life, whether as a result of serious human rights violations, in humanitarian disasters, or in situations of conflict.

*) This article draws on publications by the author, including: ‘Migration and frontier deaths: a right to identity’, in Marie Bénédicte-Dembour and Tobias Kelly (eds.), Are Human Rights for Migrants?: Critical Reflections on the Status of Irregular Migrants in Europe and the United States, Abingdon, Routledge, 2011 [in press]; ‘The Legal Protection of Stranded Migrants’, in Ryszard Cholewinski, Richard Perruchoud and Euan Macdonald (eds.), International Migration Law: Developing Paradigms and Key Challenges, The Hague, T.M.C. Asser Press, 2007, pp. 29–48; and ‘International Migration and Human Rights’; expert paper for the Global Commission on International Migration (GCIM), 2005.1) The terms have been used, respectively, by Doris Meissner [former Commissioner of the US Immigra-tion and Naturalization Service], and the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants. See Doris Meissner and Donald Kerwin, DHS and Immigration: taking stock and correcting course, Washing-ton, D.C., Migration Policy Institute (MPI), 2009, p. 15; and Report on the Human Rights of Migrants to the UN Human Rights Council, UN doc. HRC/7/12 (25 February 2008), para. 21.

136 S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156

The number of migrants who have died at the sea frontiers of the European Union, and of other states, is high but unknown, as are the identities of many – perhaps most – of those who have died. The deaths are frequently an outcome of irregular movement on unsafe routes in response to tightened border control, and specifically of the criminal or negligent actions of smugglers and traffickers, as well as the result of accident, shipwreck, and extreme weather.

In the course of the last decade, high numbers of arrivals have tested the capac-ity of states at southern EU frontiers – especially islands such as Malta, Lampe-dusa, and the Canaries – to respond at an operational level. Response at a policy level has been criticized for its failure to address the human costs of strict border control.2 But in their December 2009 Stockholm Programme, EU Member states agreed as an ‘important objective’ to ‘avoid the recurrence of tragedies at sea. When tragic situations unfortunately happen, ways should be explored to better record and . . . identify migrants trying to reach the EU’.3

This article considers some issues which arise from the Stockholm commit-ment insofar as it concerns migrant deaths at European sea borders. It first exam-ines the dimensions of irregular migration, some of the factors underlying its growth in the last decade, and the specific need to record and identify the missing and dead. It considers the anonymity of many migrant deaths, and the lack of information for their families. It argues that states should take into account not only their duties under international human rights law, criminal law and mari-time law, but also principles which derive from international humanitarian law and protect the rights of the missing and the dead, and respect the right of fami-lies to know the fate of missing relatives. It proposes some steps by EU Member states to record and identify fatalities at maritime borders.

1. The Dimensions of Frontier Deaths

Over the last two decades, irregular migration has steadily grown. This is not only a European phenomenon: migratory ‘fault lines’4 are to be found between poor or insecure states and wealthier and more secure states in different regions of the world.5 Increased emigration is ‘pushed’ across these fault lines by poverty, perse-

2) See Thomas Spijkerboer, “The Human Costs of Border Control”, European Journal of Migration and Law (2007) 9, 127–139.3) The Stockholm Programme – an open and secure Europe serving and protecting the citizen, doc. 17024/09, adopted by the European Council, 10–11 December 2009, Part 6. 4) The term ‘migratory fault lines’ is a useful way of thinking about the wider asymmetries in human development, human security and human rights which drive irregular migration. UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants, Report to UN General Assembly, UN doc. A/59/377, para. 7.5) Rising per capita income differences help to explain why so many migrants from low and middle-income countries take big risks to enter high-income countries. In 2000, the world’s GDP was USD 30 trillion, making average per capita income USD 5,000 a year, but the range was from USD 100 per person per year in Ethiopia to USD 38,000 in Switzerland, a 380 to 1 gap. “Migrants in the

S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156 137

cution, insecurity and conflict, and immigration is ‘pulled’ by labour demand, economic opportunity, and the need for protection and personal security.6 ILO research found that one cause of high levels of irregular migration was the grow-ing disjuncture between migratory pressures, economic opportunities and closed borders in a globalised world economy.7 The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) recently noted that although traditional forms of displacement owing to conflict, persecution and human rights violations are still prevalent, present-day migration is also driven by ‘population growth, urbanization, governance failures, food and energy insecurity, water scarcity, nat-ural disasters, climate change and the impact of the international economic crisis and recession’.8

High levels of border-crossing deaths are recorded on migratory fault lines: along the land border between Mexico and the US, and at the maritime borders between north Africa and southern Europe, and between the Horn of Africa and Yemen. While migration across these frontiers is not a new phenomenon,9 in the last two decades the number of migrants moving irregularly has increased as des-tination countries have tightened, extended and externalised their border controls.

Migration control has been integrated into policies to address terrorism, national security and international crime. In Europe, NATO’s counter-terrorism operations in the Mediterranean have involved it in monitoring ships carrying irregular immigrants and asylum-seekers.10 On the US land border with Mexico, hundreds of sensors scattered through the desert alert aerial drones to movements of migrants or drug smugglers. These militarised operations are increasingly an integral part of immigration control policies.11 Mauricio Albahari records a 2002 request for assistance made by the Italian Government to the EU ‘on whose behalf it was fighting a ‘war against clandestine immigration’. At that time about one quarter of the Italian Military Navy’s total hours of navigation were exclusively devoted to immigration control.12

Global Labour Market”, Philip Martin, Expert Paper, Global Commission on International Migration, September 2005. 6) See, e.g., interviews with arriving migrants and asylum seekers from Somalia and Ethiopia, who spoke of the different reasons why they had left their homes. No Choice: Somali and Ethiopian Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Migrants Crossing the Sea of Aden, Médécins Sans Frontiers, June 2008. 7) ‘Smuggling occurs because borders have become barriers between job seekers and job offers’. Towards a Fair Deal for Migrant Workers in the Global Economy, Geneva, ILO, 2004, para. 202. 8) 2010 High Commissioner’s Dialogue on Protection Challenges, Background Paper, December 2010, p. 2. 9) Hein de Haas, “The Myth of Invasion: the inconvenient realities of African migration to Europe”, Third World Quarterly (2008), 29(7), 1305–1322.10) See, e.g., “Active Endeavour ships assist Greece in illegal immigration operation”, NATO Press Release, 30 March 2006.11) See Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, UN doc. A/62/263, November 2007; “Birds on Patrol: cracking down on illegals”, Economist, 5 June 2010.12) Maurizio Albahari, Death and the Modern State: Making Borders and Sovereignty at the Southern Edge

138 S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156

These controls are not confined to northern ‘receiving’ countries, and have been ‘externalised’ to transit countries. In sub-Saharan Africa, EU funding is providing Mauritania with new border posts, equipped with advanced informa-tion technology, and a database of foreign nationals.13 Noting that the country was ‘on the route taken by illegal immigration, drug and arms trafficking’, the Minister of Defence told a journalist, ‘(w)e are prepared to sacrifice everything else for the sake of security. It is our number one priority, ahead of development and democracy’.14

The total number of migrants and refugees who have tried to cross sea borders in the last decade is unknown,15 as are the numbers who died on the journey. One estimate suggests that as many as one out of four persons attempting to reach Europe by sea had perished during the trip.16 The International Centre for Migra-tion Policy Development (ICMPD) estimated that at least 10,000 died in the Mediterranean trying to cross to Europe in the decade 1993–2003.17 Fortress Europe, an NGO which maintains records taken from media reports, lists 10,925 deaths on European maritime frontiers between 1988 and 2008.18

Although deaths continued to be reported, figures for 2010 indicated a reduc-tion in numbers. Until 2007, most irregular migrants had arrived at Greek, Ital-ian and Spanish borders; bilateral deals, such as Italy’s with Libya and Spain’s with Senegal and Mauritania, then ‘largely closed down’ the western and central Med-

of Europe, Working Paper 137, Centre for Comparative Immigration Studies, University of California, May 2006, p. 9. Albahari also refers to a statement in 2003 by an Italian government minister calling for ‘clandestine immigrants . . . to be kicked out’. ‘There comes a moment when the use of force is necessary. Marina Militare and Finanza must line up to defend our shores and use their cannons’. Ibid., citing a report in Il Corriere della Sera, 16 June 2003.13) “Mauritania: new measures to combat illegal immigration towards the EU”, IP/06/967, 10 July 2006.14) Isabelle Mandraud, “Mauritania tries to close its Borders”, Le Monde/Guardian Weekly, 11 June 2010.15) UNHCR figures suggest that some 50,000 people crossed the Gulf of Aden in smugglers’ boats in 2008 ‘to seek safety or a better life’, a 70% increase on the previous year. In 2008, some 35,000 asylum-seekers and migrants arrived in Italy irregularly by sea; they were of 61 nationalities. Refugee Protection and International Migration: a review of UNHCR’s operational role in southern Italy, UNHCR, September 2009.16) Interview with Robert Strondl of Frontex, cited in EU Agency for Fundamental Rights, EU Call for Tender: Treatment of Third Country Nationals at EU Borders, Ref. 2010/S 148–227850, D/SE/10/06, Annex A.1 – Technical Specifications, p. 5.17) ICMPD, Irregular Transit Migration in the Mediterranean – Some facts, futures and insights, Vienna: ICMPD 2004.18) Fortresseurope.blogspot.com (as at 29 August 2010). ‘In the Sicily channel 4,183 people died along the routes from Libya, Egypt and Tunisia to Malta and Italy, including 3,059 missing; 138 other people drowned sailing from Algeria to Sardinia. Along the routes from Mauritania, Morocco and Algeria towards Spain, through the Gibraltar strait or off Canary islands, at least 4,475 people died, including 2,275 who were missing. Then 1,323 people died in the Aegean, between Turkey and Greece – but also between Egypt and Greece – including 823 missing, and 603 people died in the Adriatic sea, between Albania, Montenegro and Italy, including 220 missing. And at least 624 people were drowned trying to reach French island of Mayotte, in the Indian Ocean. But the sea is not only crossed aboard makeshift boats. Sailing hidden inside registered ferries and cargo vessels 153 men died asphyxiated or drowned.’ (as at 4 November 2009).

S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156 139

iterranean routes into the EU;19 Frontex recorded drops of some 90 per cent in the detection of irregular migration on the Central Mediterranean route to Malta and on the West African route to the Canary Islands.20 NGOs also reported steep reductions in the number of reported deaths at EU sea borders.21 But it was uncertain whether this reflected a reduction in irregular journeys, or only a change of routes; Fortress Europe warned that it was unclear whether deaths had decreased overall, or whether more occurred on the high seas, where ships were wrecked further away from ‘the gaze of our cameras’.22 Nor was it known the degree to which interception at sea, and externalized controls, had displaced irregular sea migration to dangerous land and desert routes in north Africa.23 Political develop-ments in north Africa in early 2011, notably in Libya, and increased deaths at sea were evidence of the essential fragility of externalized border controls.

But information on fatalities is ‘scarce and inconsistent’,24 and the figures should be treated with caution, because estimates tend to be based on media reports, on detection levels,25 or on the accounts of survivors of a particular inci-dent. It is in the nature of frontier deaths that often no precise statistical account-ing is possible. This is especially true of deaths at sea where bodies may never be found.26 Caution suggests that the real figures may be higher.

2. Avoiding Tragedies at Sea

The Stockholm Programme recognised that action by EU Member states is needed to prevent tragedies at sea. In considering how to avoid deaths at sea, states face a number of difficult challenges. These range from clarifying the links between tighter border controls and increased deaths, to implementing legal duties to prosecute smugglers and traffickers.

Over the last decade, evidence from different regions of the world has indi-cated that tighter border controls have led to the displacement of irregular migra-tion to more dangerous sea and land crossings. The ‘most serious effect’ of tighter

19) A Friendship, Partnership and Co-operation Treaty came into effect between Italy and Libya in 2009. See ‘Border Burden’, Economist, 21 August 2010. 20) Current Situation at the External Borders of the EU (January–September 2010), map on the Frontex website at http://www.frontex.europa.eu/situation_at_the_external_border/art18.html.21) United records list over 1,000 deaths for the period December 2008–April 2009, and less than 100 for the same months in 2009 and 2010. “List of 14037 documented refugee deaths through Fortress Europe”, 20 January 2011, http://www.unitedagainstracism.org/pages/underframeFatalReali tiesFortressEurope.htm.22) Fortress Europe, “The Massacre Continues: 459 deaths in the first 6 months of 2009”, 2 July 2009.23) See European Borders: controls, detention and deportations, Migreurop, 2009/10 Report, pp. 18–26.24) Spijkerboer, supra note 2, p. 139.25) Ibid. See also the discussion of irregular migration statistics in “Organised Crime and Irregular Migra-tion from Africa to Europe”, UN Office on Drugs and Crime Control, July 2006, pp. 4–5.26) See generally Jorgen Carlin, “Unauthorized Migration from Africa to Spain”, International Migration (2007), 45(4), 3–35; Leanne Weber, “Knowing-and-yet-not-knowing about European border deaths”, Australian Journal of Human Rights (2010), 15(2), 35–58.

140 S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156

US-Mexico border controls has been the increasing number of deaths of people trying to cross.27 A 2006 briefing to the European Parliament concluded that efforts to curb the number of migrants trying to reach Europe had not led to a decrease in the number of irregular migrants; instead, they have had the effect of displacing migration from one place to another and were accompanied by an increasing number of fatalities at the EU’s external borders.28

Official efforts to examine the link between border controls and fatalities have been more systematic in the US than in Europe. At the request of the US Senate, the Federal Government Accountability Office (GAO) examined the evidence of deaths on the US border with Mexico, and found that tighter border control had not deterred illegal entry, but rather diverted routes to more dangerous terrain, with many non-nationals risking death and injury ‘by trying to cross mountains, deserts and rivers’29 In 2009, soon after she stepped down as US Immigration Commissioner, Doris Meissner described the rising number of frontier deaths as ‘a tragic by-product of border enforcement’.30 US officials working at the Mexican border have confirmed the lethal effects of tougher enforcement.31

In Europe, there has been less official willingness to examine the evidence, and institute systematic data collection. In an academic and influential review of evi-dence in 2007, Thomas Spijkerboer considered the ‘human costs’ of EU maritime border control. He called for more and more reliable data,32 and concluded that available data did not suggest that intensified border controls had led to a decrease in the number of irregular migrants: rather than abandoning their plans to travel to Europe, these migrants had simply chosen more dangerous migration routes, which exposed them to even greater risks. ‘As matters stand now, it seems . . . likely that . . . border deaths increase as a consequence of intensified border control’.33

27) ‘The strict border controls near urban areas in California and Texas have meant that those who try to cross the border do so in uninhabited and relatively un-patrolled areas in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. As a result, more and more people have died due to asphyxia, hypothermia, dehydration, accidents or drowning, when trying to cross the inaccessible and un-patrolled areas such as deserts, . . . rivers, canyons, streams and mountainous zones’. Inter-American Commission of Human Rights, Annual Report 2003, paras. 117–118.28) Trends in the Different Legislations of the Member States concerning Asylum in the EU: The Human Costs of Border Control, Briefing Paper, doc. IPOC/C/LIBE/FNC/2005–23-SC1, July 2006.29) Illegal Immigration: Border-Crossing Deaths have Doubled since 1995; Border Patrol’s Efforts to Prevent Deaths have not been Fully Evaluated, Report to the Honorable Bill Frist, Majority Leader, U.S. Senate, doc. GAO-06–770, August 2006, p. 2.30) Meissner and Kerwin, supra note 2.31) ‘As we gain more control, the smugglers are taking people out to even more remote areas. . . . They have further to walk, and they are less prepared for the journey, and they don’t make it’. Omar Candelaria, Special Operations Supervisor for the Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector; “An Arizona Morgue Grows Crowded”, New York Times, 29 July 2010.32) See, also, recommendations for research and reporting made to the European Parliament in The Human Costs of Border Control, supra note 28.33) Spijkerboer, supra note 2, pp. 131 and 139.

S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156 141

Spijkerboer argued that states whose policies increase the loss of lives of irregu-lar migrants are ‘obliged to exercise their border controls in such a way that the loss of life is minimised’.

In other policy fields, measures aimed at increasing safety, such as measures related to traffic, health care and labour relations, are taken . . . because human lives deserve protection by the state. The same reasoning should apply to migration policy.34

Frontex claims that improved maritime border co-operation has had ‘measur-able results’ in reducing people smuggling and preventing the loss of lives at sea.35 But UNHCR has criticized state policies which lead to ‘boat people’ being ‘inter-dicted, intercepted, turned around, ignored by passing ships, shot at, or denied landing’; tough sea policies have not solved, just changed, and complicated the dynamic of irregular movement.36 Resolving the tension between preventing arrivals and protecting migrants and refugees on their journeys is essential if future tragedies are to be avoided.

Action is also needed to protect migrants against death and injury at the hands of smugglers and traffickers.37 Serious human rights violations, including viola-tions of the right to life, and the infliction of cruel, inhuman and degrading treat-ment, appear to be endemic on many irregular journeys to Europe.38

Where migrant deaths are the result of criminal acts, there is a legal obligation on states to investigate and prosecute. States have duties under both international criminal law and international human rights law to protect individuals against abuses committed by state officials and by private ‘actors’, including smugglers.39 But the practical obstacles to discharging these duties may be substantial.

34) Ibid.35) Eurasylum interview with General Brigadier Ilkka Laitinen, Executive Director of Frontex, September 2010.36) Erika Feller, Assistant High Commissioner for Protection, speaking to the UNHCR’s Executive Com-mittee, 6 October 2010.37) Examples include: No Choice: Somali and Ethiopian Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Migrants Crossing the Sea of Aden, Médécins Sans Frontiers, June 2008; Human Rights Watch, Pushed Back, Pushed Around: Italy’s forced return of boat migrants and asylum seekers, Libya’s mistreatment of Migrants and Asylum Seekers, 2009; Organized Crime and Irregular Migration from Africa to Europe, UN Office on Drugs and Crime, July 2006. See, also, Maurizio Albahari’s description of smuggling operations between Albania and Italy, and the complex interplay between politics and legal enforcement, in “Death and the Modern State: Making Borders and Sovereignty at the Southern Edge of Europe”, supra note 12, and “Flood of African Migrants Risking Perilous Journey at New Heights”, Guardian Weekly, 18 July 2008.38) Afghan boys aged between the years of 9 and 18 described how they saw fellow travellers injured or suffocated locked in the backs of lorries, or drowned at sea – sometimes through the deliberate sinking of their boats. Christine Mougne, Trees only move in the wind, a study of unaccompanied Afghan children in Europe, UNHCR, June 2010.39) Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organised Crime, 2000, Art. 16; Human Rights Committee, General Comment No. 31: The Nature of the General Legal Obligation Imposed on States Parties to the Cove-nant, UN doc. CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add. 13 (26 May 2004), para. 8.

142 S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156

One obstacle is the transnational character of the offences. In 2005, Spanish police opened an investigation into the deaths of around 50 migrants, after the bodies of 11 young men were found on board an unmarked and drifting boat in the Caribbean. They were from Guinea Bissau, Senegal and Gambia, and had paid a Spanish national to take them to the Canary Island.40

Other obstacles arise in situations where both migrants and their smugglers or traffickers deliberately avoid any contact with the state, or where the state has few investigative resources, or where the state’s own officials are implicated in smuggling operations which generate considerable proceeds.41

3. Developing a Response to Migrant Frontier Deaths

International law provides a broad framework within which state policies to pre-vent and respond to migrant frontier deaths can be developed. Deaths in the course of irregular migration journeys share some characteristics with other large-scale and violent deaths – whether in major accidents, in armed violence, in vio-lent displacement, in conflict or in humanitarian disasters – and give rise to some broadly equivalent protection issues.

While international human rights law is the starting point, over the last decade international criminal law and international maritime law have been developed in ways which provide protection to smuggled and trafficked migrants. There are also arguments for integrating humanitarian law principles into rules to deal with situations of migrant frontier deaths; originally designed to deal with deaths in situations of international conflict more than a century ago, humanitarian law now influences state practice in other areas such as political disappearance and deaths in humanitarian disasters.

3.1. International Human Rights Law

States have a general obligation to respect and ensure fundamental rights, includ-ing the rights of all migrants. To this end, states must take affirmative action, and

40) ‘For €1,300 each, they were promised a trip to the Canary Islands by a . . . Spaniard. Their boat was to be a motorised yacht, . . . bearing no name and no flag. They paid to make the voyage, assuming that the Spaniard – a mechanic based in the Canaries – would be skippering the boat. At the last moment . . . a Senegalese man took over and the Spaniard disappeared. . . . Somewhere near the Mauritanian port of Nouadhibou the yacht ran into trouble. Another boat was sent to its aid . . . The yacht was towed but, at some stage, the line was severed. El Pais reported that it had been hacked with a machete. ‘With no fuel left and food and water running out . . . (t)he yacht drifted into the stormy Atlantic and, it is assumed, people were tossed or washed overboard as they died’. Daily Nation, 29 May 2006.41) See Organized Crime and Irregular Migration from Africa to Europe, supra note 37, p. 17. Human Rights Watch has documented linkages between smugglers and security and law enforcement officers in its report on Libya, supra note 37, pp. 53–57. See also Carlin, supra note 27, p. 23. Maurizio Albahari, “Death and the Modern State: Making Borders and Sovereignty at the Southern Edge of Europe”, supra note 13, pp. 21–24, speaks of ‘various scales of corruption and connivance involving local authorities, the police, and larger national frameworks’. See also Human Rights Watch, supra note 37, p. 54.

S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156 143

avoid taking measures that limit or infringe on a fundamental right. The obliga-tion extends to acting with due diligence to prevent and punish abuses against migrants, whether the perpetrator is a state agent or a private individual; there is a duty to prevent avoidable loss of life.

Rights which are most at risk in the context of irregular frontier crossings include the right to life, protection from inhuman and degrading treatment and from refoulement, the right to food and drinking water, to emergency health care, and access to legal remedies.

In the case of those missing through enforced disappearance, the right to know the fate of a missing relative as well as the correlative obligation of public author-ities to carry out an effective investigation are recognised in international human rights law, notably through the protection of the right to life, the prohibition of cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, and the right to family life.42 In a recent decision on the use of forensic genetics for identification, the UN Human Rights Council emphasised the ‘importance of restoring identity to those persons who were separated from their families of origin . . . in situations of serious violations of human rights . . .’.43

Migrant deaths and loss raise very specific issues in relation to the right to fam-ily life, and both the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child and the case law of the European Court of Human Rights interpret the right to family life in ways which have a clear relevance to situations where – for example – a father has died in the course of irregular migration.44

Although the situation of the missing and dead has historically been a matter for international humanitarian law, human rights norms are now addressing these issues and integrating humanitarian law principles. The UN Human Rights Council, at the request of the UN General Assembly, is identifying the human rights of missing persons in situations of conflict. This rights-based approach focuses on principles which are well established in humanitarian law: prevention, the restoration of family links, clarification of the fate of missing persons, the right of families to know, prosecution of human rights’ violations, the legal status of missing persons, and the ‘management’ of the dead and identification of their remains. Victims include not only missing persons, but also their families.45

One example of the practical application of human rights norms to the missing and dead can be found in the Operational Guidelines on Human Rights and Natu-ral Disasters of the UN’s Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC). These set out steps to be taken to establish the fate of missing family members, to collect,

42) See International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, UN General Assembly resolution A/RES/61/177 (20 December 2006). The Convention entered into force on 23 December 2010, and has now been ratified by 23 States parties.43) Human Rights Council, Resolution 10/26, Forensic Genetics and Human Rights, 27 March 2009.44) See Stefanie Grant, “Migration and Frontier Deaths: a right to identity”, supra note *. 45) Human Rights Council, Advisory Committee, 6th Session, Report on Best Practices in the Matter of Missing Persons, UN doc. A/HRC/AC/6/2 (22 December 2010).

144 S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156

identify and return mortal remains to families, and to deal with unidentified bodies. The Guidelines state – inter alia – that family members should have information and access to gravesites, and should be ‘given the opportunity to erect memorials’.46

3.2. International Criminal Law

Human rights principles concerning the prosecution of migrant smugglers and traffickers, and the protection of vulnerable migrants, are contained in interna-tional criminal law, and specifically in two protocols to the UN Convention against Transnational Organised Crime. The Trafficking Protocol requires states to make trafficking in persons a criminal offence, and provides important human rights protection to victims of trafficking.47 Similarly, the Smuggling Protocol criminalizes migrant smuggling, requiring states to prosecute the smuggler, but not the migrant, and to protect migrants’ rights, ‘in particular the right to life and the right not to be subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment’.48

3.3. International Maritime Law

In response to the high migrant and refugee death toll arising from the use of unseaworthy and overcrowded vessels, the increasing rescue of migrants and refugees in distress, and the reluctance of some states to allow ships which had rescued survivors to disembark them, international maritime law was strength-ened in 2004.

A shipmaster’s obligation to render assistance at sea is both a longstanding maritime tradition, and an obligation in international law. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 [‘UNCLOS’] obliges states to ‘require the master of a ship flying its flag. . . . to render assistance to any person found at sea in danger of being lost’.49 The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea 1974 [‘SOLAS’] provides that a ship master who is able to provide assistance ‘is bound to proceed with all speed’ to rescue persons in distress at sea.50

But ships masters were increasingly finding themselves in situations where, even after rescue had taken place, states would not allow undocumented migrants

46) Protecting Persons Affected by Natural Disasters, IASC Operational Guidelines on Human Rights and Natural Disasters, June 2006, guidelines D.3.4–D.3.9.47) Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organised Crime, 2000, Part II.48) Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air, supra note 39. See, also, Irregular Migration, Migrant Smuggling and Human Rights: Towards Coherence, International Council on Human Rights Policy, Geneva, 2010.49) UN Convention on the Law of the Sea [‘UNCLOS’], 10 December 1982, Art. 98(1).50) International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea [‘SOLAS’], 1 November 1974, Chapter V, Regulation 33(1).

S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156 145

and refugees to land. Amendments were therefore made to SOLAS,51 and to the International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue 1979 [‘SAR’].52 States are now required – inter alia – to arrange disembarkation as soon as reasonably practicable, and ships masters have a duty to treat those they have rescued with humanity, within the capabilities of the ship.53

3.4. International Humanitarian Law

The principles of international humanitarian law which apply to deaths in situa-tions of armed conflict are increasingly informing states’ action in other situations of loss and death. They usefully integrate three perspectives: that of the state, the individual, and the family.

The 2009 Guiding Principles on the Missing 54 of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) offer practical guidance. They have the dual task of preventing persons from going missing, and of protecting the rights of the miss-ing and their families. The rights they protect have clear relevance to migrants: the right not to be arbitrarily deprived of life; the right to respect for family life; the right to know the fate of the missing; and the right to be recognized every-where as a person before the law. Thus

everyone has the right to know about the fate of his/her missing relatives, including their where-abouts or, if dead, the circumstances of their death and place of burial if known, and to receive mortal remains. The authorities must keep relatives informed about the progress of investigations.55

Like the IASC Operational Guidelines on Human Rights and Natural Disasters, the Guiding Principles identify a number of duties which are relevant to migrant fron-tier deaths: to search for and collect the dead; to take measures to identify and dispose of the dead in a respectful manner and respect their graves; to give indi-vidual burials where remains cannot be handed over to their family, with collec-tive graves as the exception; and to mark all graves.56

The link to human rights law is clearly made in the Commentary to Article 7 of the Guiding Principles – the right of relatives to know the fate of missing persons – which stipulates that the right to know the fate of a missing relative is

51) SOLAS, ibid.52) International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue [‘SAR’], 27 April 1979, Chapter 3.1.9.53) UNHCR and International Maritime Organization (IMO), Rescue at Sea. A guide to principles and practice as applied to migrants and refugees, September 2006, available at http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/45b8d1e54.html; Guidelines for the Treatment of Persons Rescued at Sea, Maritime Safety Com-mittee of IMO, Resolution MSC 167(78) adopted May 2004.54) Guiding Principles/Model Law on the Missing, principles for legislating the situation of persons missing as a result of armed conflict or internal violence: measures to prevent persons from going missing and to protect the rights and interests of the missing and their families, ICRC, 2009.55) Guiding Principles, ibid., Art. 7.56) The missing and their families, action to resolve the problem of people unaccounted for as a result of armed conflict or internal violence and to assist their families, ICRC, December 2003.

146 S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156

‘recognised under international human rights law’, notably through the protec-tion of the right to life, the prohibition of torture and other forms of cruel, inhu-man and degrading treatment or the right to family life’.57

These principles are increasingly reflected in international human rights law, notably in relation to protection against enforced disappearance.58 The issue of the missing is currently on the agendas of the UN General Assembly, the UN Human Rights Council59 and the Organization of American States (OAS).60 These intergovernmental bodies are setting standards ‘to prevent the disappearance of persons, to ascertain the fate of those who have disappeared, and to respond to the needs of members of their families, both in situations of armed conflict or other situations of armed violence and in cases of forced disappearances’.61

While it is unlikely that EU Member states of the UN Human Rights Council see the development of normative standards for the missing as having any rele-vance to irregular migrants, the standards nonetheless offer useful points of depar-ture for considering how states should approach situations of migrant deaths and loss at European frontiers.

3.5. Council of Europe

The Council of Europe’s Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings 2005 focuses on the protection of victims of trafficking and the safeguard of their rights. It also aims at preventing trafficking as well as prosecuting traffickers. The Convention provides for the setting up of an independent monitoring mech-anism guaranteeing parties’ compliance with its provisions.62

Norms concerning missing persons were adopted in 2009 by the Council of Europe to deal with situations in which persons are missing but death is not cer-tain. A missing person is defined as someone who ‘has disappeared without trace and there are no signs that he or she is alive’. These Principles Concerning Missing Persons and the Presumption of Death have clear relevance to situations of migrant maritime deaths where families have no information and need to establish death, including for purposes of inheritance or remarriage. They provide for a declara-tion of presumed death to be issued by the state of nationality or habitual resi-

57) Guiding Principles, supra note 54, Commentary to Article 7.58) International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, supra note 42.59) See, e.g., United Nations General Assembly resolution 61/155, Missing persons, 19 December 2006; Report of the UN Secretary-General on missing persons, doc. A/63/299; UN Human Rights Council resolution 7/28, Missing persons, 28 March 2008.60) OAS, Thirty-ninth Regular Session, AG/RES. 2513 (XXXIX-O/09), Persons who have disappeared and assistance to members of their families, 4 June 2009.61) Ibid.62) Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings, 16 May 2005, European Treaty Series No. 197.

S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156 147

dence, where the person was reported missing either in the state’s territory or during a voyage of a vessel registered in that state.63

4. Loss of Identity and the Need for Recording

Many migrants travel long distances, and – especially in the case of deaths at sea – the places where they go missing or die, the countries to which their bodies are carried, and the countries where they are eventually found, may be far away from the home country. Identification is often difficult, many deaths remain anonymous, and families who try to establish what happened to missing relatives may face insuperable obstacles.

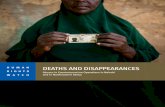

Symbolic acknowledgement of these complex tragedies is to be found in a memorial which was dedicated in 2008 to the thousands of migrants who had died or gone missing at sea trying to reach Italy. Built on the island of Lampedusa, it is in the shape of a door facing the sea, and represents the gateway to Europe. It commemorates the women, men and children who lost their lives ‘in search of a better life’. The memorial does not, because it cannot, list the names, or even the nationalities, of those who died.64

One frequent consequence of irregular migration is a loss of personal identity – name, nationality, religion, home country, and family. For irregular migrants, the loss may be the result of voluntary abandonment, or it may be involuntary. Loss, or abandonment, of identity is a common characteristic of irregular travel, where migrants move without identity documents. This is one reason why the identities of very many frontier deaths are unknown. The NGO United Against Racism listed 1,859 deaths on the European sea borders for the 12-month period between April 2007 and March 2008; in all but six cases, the entry is marked ‘NN’ – no name.65

For refugees seeking international protection, the only means of leaving their home country and accessing another state to seek protection is often through the use of fraudulent travel documents and resort to the assistance of smugglers. Some asylum-seekers lack identity papers because they were unable to obtain valid passports and visas from national authorities before leaving, or it was only through the use of misleading entry visas – i.e. issued for a purpose other than asylum – that they were able to escape the country of persecution. Others may have used false passports provided by smuggling or trafficking operators. For

63) Recommendation CM/Rec(2009)12 of the Council of Ministers to Member States, on principles concerning missing persons and the presumption of death, 9 December 2009. See Principle 2.64) The project was initiated by the Italian NGOs Alternativa Giovani Onlus, Arnoldo Mosca Mondadori and Associazione Amani, and supported by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the Italian Ministry of the Interior, the regions of Sicily and Puglia, the municipality of Milan and UNHCR.65) See http://www.unitedagainstracism.org.

148 S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156

many smuggled and trafficked migrants, the loss of identity is involuntary, because their documents are stolen or destroyed by their smugglers and traffickers.

But for others it is a response to the fear of detection. Caroline Moorehead has described the refusal of West African migrants, rescued from the sea off the Sicilian coast, to tell even the villagers who had welcomed and supported them who they were or where they came from. ‘It was as if word had reached them that they should give away absolutely nothing about themselves, not even their names’.66

Asylum-seekers and migrants may deliberately destroy their identity docu-ments in order to avoid removal if they are apprehended. Some even mutilate themselves to erase their fingerprints, and prevent identification. One group of Afghan asylum-seekers, waiting to be removed by French police from a camp outside Calais, showed a journalist their scarred hands where they had ‘tried to sear and burn off the pads of their finger tips’.67

Researchers who interviewed migrants in Rome reported that individuals ‘who showed us their hands felt they were driven to this extreme as a desperate measure to escape what they consider as unliveable circumstances’. One young man described how he used a lit cigarette to burn the fingerprints off his ten fingers. He was caught and detained until his fingers were completely healed, and his prints could be checked. His motive had been to prevent his prints being checked against migration databases, such as EURODAC, and to avoid return to a coun-try of feared persecution.68

Where irregular migrants die on the journey, the death is thus often anony-mous, and the result is a total loss of identity. Identification is made the more difficult because these deaths are in a real sense transnational deaths: death may have occurred not only away from the individual’s country of nationality, but also in territory or waters far outside the ‘finding’ state’s jurisdiction, so the individu-als have no links with the countries where their bodies are found, or the beaches on which they are washed up.

Unlike ships and registered ferries, the small boats and pateras used by smug-glers have no passenger lists. So identification of those who die must usually rely on the testimony of fellow migrants, if they are willing to speak with officials, or

66) Caroline Moorehead, Human Cargo, a journey among refugees, London: Chatto & Windus 2005, p. 59.67) “Hope Dims in Calais ‘Jungle’ ”, Emma Jane Kirby, BBC News, 19 September 2009.68) ‘There are three ways commonly used to remove fingerprints. A refugee will burn his/her fingerprints and palm prints with a lit cigarette. This . . . process can take several hours. It leaves a person with fingers and hands in constant pain and unable to use their hands . . . Another method . . . is to place their hands directly over a gas, charcoal or electric stove or immerse them in scalding water to remove their finger prints and palm prints. This is no less painful, than using a lit cigarette. The third process requires a per-son to run sandpaper against his/her skin. This may seem comparatively less painful, but not so. It takes two or three days of rubbing fingers and palms with sand paper to entirely remove the top skin, leaving raw, blood exposed skin’. Nunu Kidane and Gerald Lenoir, Blog #2: “African Immigrants and Refugees in Europe: A PAN and BAJI investigation”, 3 November 2009. http://blackallianceblog.blogspot.com/2009/11/blog-2-african-immigrants-and-refugees.html.

S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156 149

on whatever papers and possessions are found on the bodies, or on the forensic findings of any criminal investigation by national police.

When the boat from Guinea Bissau was found off the shores of Bermuda in 2005, none of the eleven bodies had identity papers, and only one could be identified. Nothing was known about their 40 companions who had drowned, even whether Christian or Muslim religious rites should be used in the funerals. The Barbadian press reported that

(w)hen Barbadian coastguard officers boarded . . ., they found the . . . bodies of 11 young men, dressed in shorts and colourful jerseys, who had been partially petrified by the salt water, sun and sea breezes of the Atlantic Ocean . . .An air ticket from Senegal Airlines and a tragic note written by one of the men as he was preparing to die . . . helped investigators from several countries set about unravelling the mystery. (A)lthough the floating coffin appeared off the coast of the Americas, those on board had set off four months earlier from the Cape Verde islands, off the African coast, and had been head-ing for the European soil of the Canary Islands. The evidence . . . points to them having been cut adrift in the Atlantic and left to drift . . . the cause of the deaths was starvation and dehydration.

“I would like to send to my family in Bassada [a town in the interior of Senegal] a sum of money. Please excuse me and goodbye. This is the end of my life . . .,” the note left by the only man to be identified said.69

There are also disincentives to reporting deaths at sea, as Alabahari’s research illustrates. Italian fishermen who found bodies from a shipwreck in their nets, tossed them back into the sea, and did not alert the authorities. This practice started after a fisherman had found a corpse, taken it on board, and brought it to the attention of the local coast guard and police forces. Police enquiries blocked the fishing boat and its owner for weeks, causing financial loss for the fisherman, whose only source of income was fishing. So afterwards, when fishermen found corpses, ‘we all knew that if we announced our findings, the whole fleet would be forced to stop. We just couldn’t afford it’.70

Anonymity is evident in the growing number of burial places – in southern Europe, in north Africa, in Yemen, in the US, in the Caribbean – in which the bodies of unknown migrants are interred. These are the new migrant ‘potters fields’, places where the bodies of unknown people have traditionally been buried.

In Tripoli, the Libyan capital, bodies of migrants who drowned in the Mediter-ranean have been buried without formality and in complete anonymity. The graves were marked only ‘identity unknown: of African origin’, and are tended by migrants who were themselves waiting to leave. Some bodies – regardless of what may have been the individual’s faith – are buried in the Christian cemetery, along-side the tombs of Italian and British soldiers who died in the Second World War.71

69) Jamaica Gleaner, 25 August 2006; Barbados Free Press, 2 February 2007.70) Albahari, “Death and the Modern State: Making Borders and Sovereignty at the Southern Edge of Europe”, supra note 12, p. 14 et seq.71) “En Libye, ces émigrés qui vivent dans la clandestinité et meurent dans l’anonymat”, Agence France Presse, 2 April 2009.

150 S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156

Those who died crossing the Sahara desert are ‘buried in the sand, nothing to mark their graves, just a mound of sand’.72

In Italy, the cemetery in Otranto marks the graves of migrants who drowned in the Straits of Otranto simply as ‘Ignoto’ [‘Unknown’]. In southern Sicily, five Liberians are buried in the cemetery at Canicatti; two graves carry names, and the other three are marked only ‘Cittadino Liberiano’ [Citizen of Liberia], with a single letter of the alphabet to distinguish one from the others, because no one among the survivors was able or willing to give the bodies names.73

In the United States, in Texas:

(t)hose who are never identified are registered by the US. Under their new government-bestowed number, they are interred in the potter’s field at the Fort Lowell cemetery in Tucson. They each get a small marker with metal serial numbers. These Juan Doe burials cost Pima County $760 each.74

But the wish for anonymity and invisibility on the part of some irregular migrants does not reflect a wish to break family ties. Researchers who interviewed young Eritreans about the dangers of irregular Mediterranean crossings were told that each young man leaves word behind with trusted friends at different points in their journey in case they do not make it to their destination. They said leaving word behind gives them ‘comfort knowing that should they not make it, their families will at least know of their demise.’75 In Yemen, one of the first things that newly arrived migrants ask is for help to call their families back home.

5. The Challenge of Record Keeping and Identification

The ICRC Guiding Principles on the Missing address particular problems which also arise in the case of migrant deaths in the course of complex international journeys, and offer a common standard. They require ‘preventive measures of identification’ for persons at particular risk in situations of violence. Individual data is to be registered for the purpose of establishing identity, location, condi-tions and the fate of persons reported missing, of establishing the identity of unidentified human remains, and of providing information to families concern-ing a missing or deceased relative.76

The Guiding Principles build on traditional methods used to protect the identi-ties of missing and dead sailors and soldiers by a combination of identity discs

72) Kidane and Lenoir, supra note 68.73) Moorehead, supra note 66, p. 70.74) Luis Alberto Urrea, The Devil’s Highway: A True Story, Little, Brown and Company, 2004, p. 35.75) Kidane and Lenoir, supra note 68.76) Data which has ‘served the purpose for which it was collected’, should be destroyed to prevent inappropriate or improper future use. ICRC, Guiding Principles/Model Law on the Missing, supra note 57, Art. 11.

S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156 151

(‘dog tags’) and procedures for the preservation of personal possessions and for notification. Thus, in the case of deaths at sea, the early laws of war prohibited burial until all articles ‘which may serve to fix . . . identity . . . shall have been col-lected’, and required that documents of ‘identity, personal descriptions, objects of personal use, valuables, letters, etc.’, should be sent to national authorities.77 Originally intended as reciprocal rules to apply to deaths of a state’s own, or its enemy’s, soldiers and sailors in situations of international armed conflict, these rules have since formed the basis for principles which are applied where individuals – including enemy combatants and civilians – die or go missing in internal armed conflict, internal violence, and serious human rights violations. The Guiding Principles note the ‘paramount importance’ of identification as a method of protection, to prevent disappearance and to facilitate tracing.78

But there is as yet no common practice for correlating information about migrant deaths between different states, or often even between different jurisdic-tions in the same country. The technical skills needed for identification exist, but there is not yet an international framework establishing what information should be collected, and how it should be shared.

Deaths are typically dealt with under national procedures. In the absence of any international standard for record keeping or an international database, each state and agency will use its own practices to investigate and record unidentified deaths. In the United Kingdom, for example, a coroner’s jurisdiction to establish the cause of an unexplained death arises from the physical presence of a body, rather than where the death may have occurred.79

In 2004, Mexico established a database which contains information from reports by families filed with Mexican local, state and federal authorities, includ-ing photographs, fingerprints, and signatures from Mexican consular voting, military and consular registries. Forensic information provided by Mexican and US medical examiners is incorporated and linked to a DNA bank.80

A joint study by the American Civil Liberties Union and the Mexican Com-mission of Human Rights has drawn attention to the need for bi-national stan-dards for identifying those who die on the US-Mexican border. There are no standardised US reporting procedures for identifying the dead among different state jurisdictions, and no centralised databases for locating missing persons or unidentified migrant dead stored in morgues or buried in pauper graves.81

77) The Laws of War on Land, Manual published by the Institute of International Law (Oxford Manual), Oxford, 9 September 1880, Art. 6; Adaptation to Maritime War of the Principles of the Geneva Conven-tion: 18 October 1907, Art. 17.78) Guiding Principles, supra note 54, Commentary to Art. 11.79) See generally Jervis on the Office and Duties of Coroners, Sweet and Maxwell 2002.80) Marie Jiminez, Humanitarian Crisis: Migrant Deaths at the US – Mexican Border, American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of San Diego and Imperial Counties, and Mexican National Commission of Human Rights 2009, p. 51.81) Ibid., p. 49.

152 S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156

Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office in Arizona has an unusually high level of identification of undocumented migrants’ bodies. Investigators sift through Mexican voter registration cards, telephone numbers scrawled on scraps of paper, jewellery, rosaries, family photographs.82 The geographical location where the body is found is recorded, as are the clothing, backpacks, love letters, pictures and reli-gious scapulars commonly found on bodies. These objects help determine if body is of a US citizen or an undocumented migrant. Personal effects are photographed and put online so family and friends can see them and help in identification.

We use them as leads; we use them as clues . . . It is my job to figure out, usually from bones, what this person really looked like in life. . . . I think everybody . . . realises that we’re brothers, we’re sisters, we’re husbands or wives, we’re children, we’re fathers. If this were to happen to us, God forbid, we’d want every jurisdiction possible doing everything they could to try to identify the person.83

In Yemen, before it buries them UNHCR partner agencies photograph the bodies of those who die crossing the Gulf of Aden. Other national and interna-tional organizations have their own procedures, but there is as yet no interna-tional standard.

Identification can also draw on the very considerable progress which has been made in the identification of the dead and in the preservation of records in other situations; these are as different in character and time as the civil wars in Spain and Cyprus in the 1930s and in the 1960s, the Asian tsunami of 2004, and Argentina and Chile after the ‘dirty war’ and the political disappearances of the 1970s. In Europe, since the Bosnian war in the 1990s, sophisticated methods of genetic identification have been developed to identify individuals and establish family connections. Internationally, the Red Cross’s tracing activities have a long and distinguished history of finding missing persons, and reuniting families; wars in the former Yugoslavia, the Middle East and in many African states have gener-ated more recent flows of people searching for missing relatives and for the burial places of those presumed dead.84

Identification over time, and with certainty, is now possible through DNA. If a DNA sample is taken, relatives may then establish the fact and perhaps the circumstances of death. The International Commission on Missing Persons has identified the bodies of 5,000 of the 8,000 or so Bosnian Muslim men and boys who are thought to have died at Srebrenica in 1995.85 In a criminal investigation

82) “An Arizona Morgue Grows Crowded”, New York Times, 29 July 2010.83) Bruce Anderson, Professor of Anthropology, University of Arizona, and Forensic Anthro pologist for the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office. See Cody Calamaio, “Identifying the Unidentified”, Border-beat.net, 29 April 2009.84) See Stefan Wagstyl, “Lost and Found”, Financial Times Magazine, 31 October 2009.85) At a technical level, the biggest ‘school’ for the genetic identification of human bodies is undoubtedly Bosnia, where an International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP) was set up in 1996. ‘By match-ing DNA from exhumed bones . . . blood samples offered by relatives, the ICMP . . . [has] identified the bodies of 14,000 people who went missing in the wars that ravaged Bosnia, Croatia and Kosovo. These

S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156 153

into the deaths of 21 irregular migrants who drowned in Morecambe Bay in 2004, United Kingdom police cooperation with Chinese police led to their iden-tification by DNA matches between the bodies and relatives in China.86

6. Information for Families

The ICRC’s Guiding Principles recognise the right of relatives to know the fate of missing persons, ‘or, if dead, the circumstances of their death, and the place of burial if known, and to receive the mortal remains’. The authorities must keep the relatives informed about the progress and results of investigations.87

The deaths of irregular migrants who ‘live in clandestinity and die in anonymity’88 are clearly different from persons who go missing as a result of political disappear-ances, and from deaths in the course of conflict. The Chilean National Commis-sion on Truth and Reconciliation drew a sharp distinction between missing persons who ‘disappeared’, and persons ‘whose fate or whereabouts are simply unknown’.89

While missing migrants do not fit into either of these two categories, they are part of a more complex but not entirely different continuum.

Thus, the Chilean National Commission spoke of the ‘unresolved mourning’ of families who did not know if a relative was alive or dead.90 This points to one of the parallels between the families of the disappeared and migrant families, which was recognized in the comment of an African diplomat: referring to unmarked migrant graves in Tripoli he said that the suffering of families was ‘without any limits’, because what had happened to their relatives would always be unknown, and never resolved.91

Without any comprehensive database to which they can turn, relatives have no way of finding a missing relative who was lost in the course of irregular migra-tion across countries or even continents. In the US, for example, families of the missing

include more than 5,000 of the 8,000 or so Bosnian Muslim men and boys who are thought to have died at Srebrenica in 1995. Speed and value for money of identification by DNA has risen sharply. It now takes only a few weeks to train a police officer to use a ‘bone sample collection kit’ which costs just a few dol-lars’. “What the Dead have to Say”, Economist, 19 April 2008.86) Press Association, 24 April 2006.87) Guiding Principles, supra note 55, Art. 7.88) “En Libye, ces émigrés qui vivent dans la clandestinité et meurent dans l’anonymat”, supra note 71.89) They “may involve suicide, a common crime, some other kind of misfortune or someone’s free deci-sion to move away . . . and break ties with relatives and friends”. See Jose Zalaquett “Introduction”, in Report of the Chilean National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation, Notre Dame, IN, University of Notre Dame Press 1993.90) Ibid.91) “Le calvaire des familles est dans tous les cas sans limites et le sort des leurs restera toujours inconnu”, supra note 71.

154 S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156

wend their way through a web of law enforcement agencies, databases, states, counties, coroners, forensic specialists, consular officials, as well as non profit and volunteer organisations to locate relatives who may have died in unauthorised border crossings, been detained by immigration authorities, or kidnapped by smugglers. . . . They bounce from source to source. They painfully per-sist, sometimes for years, until the missing person is found, the dead are laid to rest, . . . or the search becomes a lifelong endeavour.92

In some cases, identities may be known to national authorities, but the families may never know of the deaths because it was impossible to trace them.

Many dead . . . come from places with no phones, homes with no addresses. The best the [Mexican] consulate can do is to call the village phone booth and hope a passerby will answer. Or they track down the mayor of the nearest town, and he then either does or does not find the widows . . . .93

Confronted by the acute emotional distress of families whose relatives had died in a collision between two ships, an English judge implicitly acknowledged the rights of families – although he only made a passing reference to international law. He recommended that the ‘principal lesson to be learned’ was ‘the impor-tance of respecting the dead and their relatives, of acting with sensitivity through-out and of ensuring that . . . full and honest information is given to relatives at every stage’.94

In the aftermath of the 2010 Haiti earthquake, international health experts warned against mass burials, and urged that efforts be made to identify bodies and respect the human rights of families. Failure to do so ‘not only goes against cultural norms and religious beliefs, but also has social, psychological, emotional, economic and legal consequences that add to the suffering directly caused by the disaster’.95

Where families, and local communities, are informed of deaths, this may play a role in prevention. There is anecdotal evidence that where a community knows that one of its members has died in the course of irregular migration, this knowl-edge deters others from leaving. In November 2010, a journalist at France 24 told the story of a Spanish undertaker who regularly takes the bodies of dead migrants back to their families in Morocco. Interviews with the friends of Bouchaid, a young man who died on the journey from Tangiers to Algeciras, suggest that his death had made them change their minds about leaving. One said that now this had happened, ‘we don’t want to do it any more’. Knowledge of the death had made Europe no longer a symbol of a better life.96

92) Jiminez, Humanitarian Crisis: Migrant Deaths at the US – Mexican Border, supra note 81, p. 48.93) Urrea, The Devil’s Highway, supra note 74, p. 35.94) Public Enquiry into the Identification of Victims following Major Transport Accidents, report by Lord Justice Clarke, Cm 5012, Her Majesty’s Stationary Office (HMSO), 2001, para. 36.4.95) Dr Jon Andrus, Deputy Director, Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), reported in The Med-ical News, 19 January 2010, “PAHO/WHO Assesses the Impact of Earthquake on Haiti’s Health Facili-ties”; “The End of Humanity in Haiti’s Mass Graves”, Earth Times, 16 January 2010.96) France 24, “Spain: the illegal aliens’ undertaker”, 2 November 2010, http:// www.france24.com/en/20101102-reporters-spain-illegal-aliens-undertaker-immigration-europe-mo rocco-remains-burial-families?ns_

S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156 155

7. Some Points of Departure

The EU’s Stockholm Programme has set Member states the practical objective of exploring how to record and identify migrants who die trying to reach the EU. It calls for dialogue and partnership between the EU, third countries and organisa-tions.97 It reinforces the view expressed by the Council of Europe’s Human Rights Commissioner two years earlier that identifying and accounting for the thousands of undocumented migrants who disappear on the journey was ‘imperative’.98

Action by EU Member states should start with a public discussion between migrant communities, the families of missing and dead migrants, their states of origin, and civil society and official institutions in the ‘destination’ states. The purpose should be to develop human rights-based policies to document deaths, preserve evidence of identity, and assist families – wherever they may be – in their search for information about their missing relatives.

Principles developed for death and loss in other situations of violence and con-flict embody many of the same ethical and rights norms which should inform discussion of migrant death and loss: prevention, identification, recognition of the rights of the family, a duty to treat the dead with respect and dignity, and – where possible – return of bodies to families. The right of families to know the fate of missing relatives includes – so far as is possible – access to information on the place of burial, the return of the body and any personal effects, and the issue of a death certificate to establish death, and clarify remarriage and inheritance rights.

A useful first step would be for states to agree common standards in three areas:

– Identification and the preservation of evidence, which will assist families to obtain information about the deaths of their relatives. This will include steps to preserve records – photographs, fingerprints, possessions, clothing – so that family members can establish if a relative has died.

– Creation of an international database, which relatives could access. – Burial: the dead should be ‘searched, collected and identified without

distinction’,99 treated with respect and dignity, and when identified, returned to their families or buried in individually marked graves.

But it is also important to consider whether this is what migrants would wish. Many have taken extreme steps to avoid any official identification, and have deliberately destroyed any form of identification. They may fear that a database,

campaign=editorial&ns_mchannel=reseaux_sociaux&ns_source=twitter&ns_linkname=20101102_reporters_spain_illegal_aliens_undertaker_immigration&ns_fee=0.97) Stockholm Programme, supra note 4, Part 6.98) The Human Rights of Irregular Migrants in Europe, Strasbourg, 17 December 2007, CommDH/Issue Paper (2007) 1.99) Report on Best Practices in the Matter of Missing Persons, supra note 45, para. 81.

156 S. Grant / European Journal of Migration and Law 13 (2011) 135–156

even with safeguards, would also be made available for security purposes and to restrict migration.100

There are today other options involving the use of web technology. One exam-ple is Refugees United, which has created an online database to reunite refugees and migrants who have lost touch with families in the course of displacement. It is anonymous, and families may use their own language, providing only the infor-mation they wish to share. To meet the need to trace missing relatives after the 2010 Haiti earthquake, websites were created not only by the ICRC but also by private commercial enterprises such as Google.101

There may also be ways in which migrant communities can adapt and update the old military practice of identity tags.

8. Concluding Comments

While states’ control of their borders is a legitimate exercise of national sover-eignty, international law requires that the manner in which they do so should also respect the rights of individual migrants. Where states ‘reject . . . migrants and leave them to face hardship and peril, if not death, as though they were turning away ships laden with dangerous waste’,102 they are in breach of their duties under international human rights law.

The loss of identity and the challenges of identification which have been described in this article demonstrate the need for international procedures to establish and protect identity in the case of migrant loss and death. Technologies now exist which can solve many of the practical challenges of recording migrant deaths: it is impor-tant that European states and civil society begin a discussion with countries of ori-gin, to consider how to use them in the case of migrant frontier deaths.

In taking forward commitments made in Stockholm, EU Member states should follow both the normative frameworks offered by international human rights, crim-inal and maritime law, and also the more practical principles for dealing with the dead and missing which have been distilled from international humanitarian law.

While these arguments may be objected to on the ground that they are difficult to realize and – even – quixotic, defining such a framework for action in this context is no more ambitious than the duties which states generally accept in the case of large-scale conflicts. Nor is it inherently more difficult than protecting human rights in other complex areas such as violence against women or the pro-hibition of torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment.

100) The issue of data is particularly sensitive because relatives who seek visas to visit burial places might thereby find themselves entered on a migration control database. See Elspeth Guild’s description of the astonishing reach and human consequences of these databases, in Elspeth Guild, Security and Migration in the 21st Century, Cambridge, Polity Press, p. 110.101) See http://haiticrisis.appspot.com/, The Guardian, 16 January 2010.102) Statement by Navanethem Pillay, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, 14 September 2009.