Ram Kinkar Exhibition Catalogue

Transcript of Ram Kinkar Exhibition Catalogue

8 - 29 october 2007

the school of the arts & aesthetics jnu new delhi

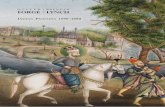

RAMKINKAR THROUGH THE

EYES OF DEVI PRASAD

NAMAN P. AHUJA

Mithuna B (detail)Cement, 1931, h. 44 cmCollection: National Gallery of Modern Art, Delhi

Inside front cover Female form, abstractWatercolour on paper, 27.5 x 17.5cmCollection: Devi Prasad

PHOTOGRAPHSAll black and white photographs are by Devi Prasad, and published in Ramkinkar Vaij: Sculptures, Tulika Books, New Delhi 2007.All colour photographs: Naman AhujaPortrait of Devi Prasad: Kristine Michael

GRAPHIC DESIGNIncarnations

EXHIBITION HANDLING & CONDITION REPORTSSeher Agarwal, Rahul Dev, A.P.Rajaram, Nidhi Khurana

EXHIBITION DESIGNPainters - Dhyaneshwar & his helpersCarpenters - Jagdish & his helpersPlans and preparatory drawings - Tony Gaochuan Audio-Visual installation - Rohit , Malavika VenugopalInstallation - Md. Ahmad Sabih, Eesha Phanse, Neha Berlia, Vibhuti Sharma, Jyothi Jayaprakash

MOUNTING AND FRAMINGMurti Ahuja

EDITORIAL Dr. Ira Bhaskar, Shruti Parthasarthy, Md. Ahmad Sabih, Jyothi Jayaprakash, Soumick De

PUBLICITYPoonam Kudaisiya & the office of the P R O, JNUAmbar Sahil Chatterjee, Premjish Nil, Elizabeth Ike, Moumita Sen, Ankush Gupta

EDUCATIONAL OUTREACHKiran Pawar, Jyothi Jayaprakash, Agastya Thapa, Nidhi Khurana

Security arrangements supervised by M.S. Cheema, Chief Security Officer, JNU.

“Tradition- whose? For what purpose?

Tradition is for human subsistence, for humanness.

There are differences in humanness in every era. This

means that apart from food, clothes and reproduction,

there is another purpose, whose name is creativity.

Something that is beyond the necessary. There is no

profit motive involved in this, only a play of joy of

the mind. This doesn’t involve doing harm to others.

There is only absorption of bliss in the process of

worshipping the sun and the moon.”

– Ramkinkar Baij

“Tradition- whose? For what purpose?

Tradition is for human subsistence, for humanness.

There are differences in humanness in every era. This

means that apart from food, clothes and reproduction,

there is another purpose, whose name is creativity.

Something that is beyond the necessary. There is no

profit motive involved in this, only a play of joy of

the mind. This doesn’t involve doing harm to others.

There is only absorption of bliss in the process of

worshipping the sun and the moon.”

– Ramkinkar Baij

“Tradition”: translated from the original hand-written jottings of Ramkinkar in a private collection, published by Das Gupta, Anshuman. Ramkinkar Baij Centenary Exhibition Catalogue, Nandan, Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan, 15 – 25 January, 2007. p. 12

him in Santiniketan. The latterly collected paintings are invariably signed and dated, something Ramkinkar was not fastidious about in his earlier works. These works re mostly dated 18.7.1971 or 18.7.1972; the date is obviously untrue. Stacks of old paintings would lie uncared for in his simple home. Ramkinkar even used them to lug a hole in his leaking roof. In his last few years however, friends and well-wishers implored him to collect and sign his old works. The 1971 and 1972 dates thus do not reflect when the work was made.

I thank my colleagues Parul Dave Mukherji, Shukla Sawant, Ira Bhaskar, Kavita Singh and Ranjani Mazumdar, comrades in arms, who have each compromised their schedules for this exhibition as I do my University, JNU, for affording us the creative space to teach our disciplines, for the trust they have reposed in us to build a unique centre for the arts. In particular I should like to mention the active support this project has received from Prof B B Bhattacharya, the Vice Chancellor and Prof Rajendra Prasad, the Rector, JNU. Prof. Thorat’s (Chairman of the University Grants Commission) launching of Devi Prasad’s book and inauguration of this exhibition has encouraged us to persevere with our work.

Mamta and Inca, who have both happily given of them-selves far beyond the call of duty, I have had the greatest joy in working with you – thank you.

And finally, our students, who have enjoyed this experience with me at every stage. This is their show. I thank you for giving me the opportunity of sharing something of what keeps me enthralled as a student of art history.

Naman P. Ahuja9.October.2007

Devi bhai’s depth of knowledge and experience have been a beacon to me for long. After seventeen years as my teacher even today he energises me to learn and express myself. The opportunity to study and handle his collection inti-mately has been an invaluable experience for me and my students. My debt of gratitude to him is profound.

This catalogue serves as a supplement to Devi Prasad’s book, Ramkinkar Vaij: Sculptures, published by Tulika Books. Its photographs and insights along with the index of Ramkinkar’s sculptural output, measurements and chronol-ogy make it a comprehensive compendium of Ramkinkar’s sculptures and I shall thus refrain from duplicating what is already available there.

This is therefore not a complete catalogue of the works in his collection, nor does it reproduce all the photographs in the exhibition. Instead I have tried to document a few origi-nal artworks by Ramkinkar, and the curatorial and design considerations of the exhibition.

Scholars involved in collating a corpus of Ramkinkar’s work have faced a most difficult task. Ramkinkar gave many works away to his students and friends. He never sought canonization. To the contrary, he was, by all accounts, completely disinterested in preserving his works. I hope this catalogue will serve of use to those interested in building an archive of the artist’s paintings. Devi received many of the works in his collection as spontaneous gifts from Ramkinkar during his days as a student at Kala Bhavan. Many of them were painted in Devi’s presence or as gifts for him. In 1978 he was able to acquire several more from

Preface and Acknowledgements

Nude study Pencil drawing on paper 25 x 36.75 cmInitialed ‘R.K.’ on bottom right and dated 18.7.1971 (in Bangla) although executed earlier. The reverse, 4b. also bears a nude study.Collection: Devi Prasad

the visitor at every level so as to communicate something of their grandeur which is impossible when they are seen from afar at their present position at the entrance to the bank.

The visitor then enters the main gallery space, which is separated into four main quadrants divided along thematic lines. It was of course possible to select very different themes, many of which were deliberated. I have chosen to present Ramkinkar as faithfully as Devi Prasad has seen him. The areas explored thus reflect how the artist engaged with / interpreted certain universal feelings at different points in his life. In contrast to the grey entrance, the min gallery space is in shades f white and the walls are treated with a textured layering of plaster-of-Paris, the more personal medium the artist used for his studies.

These are best seen clockwise. Leaving the gargantuan public sculptures behind, we enter his immediate world through his quick sketches, paintings of the world outside his studio window, and photographs by Devi of Ramkinkar’s sculptures of close friends and mentors at Santiniketan.

This takes us into the second unit which explores the human body: both idealized / mythical and based on real life studies. Ramkinkar’s models, life-drawings, sculptures of his contempo-raries and inspirations are explored here in further detail. An addi-tional gallery, appended to this, expands on this theme. It focuses more particularly on his preparatory works for the Yaksha and Yakshini where he distilled the essential features of these mythi-cal beings from every epoch in Indian history. Here we see his interpretations of famous ancient Indian sculptures permitting a rare understanding of how Ramkinkar viewed his work in a 2500 year history of sculpting.

The third section takes us more clearly into an exploration of his intimate world. His capturing of feelings of love between a fam-ily, a mother and child, child and animal and physical intimacy expose a core of humanism that underlies much of his work.

In the following section we enter from the private / personal to the public, to the extreme circumstances that personal joy is sub-jected to. His responses to the devastating anguish of drought and famine are expressive both of a deep felt pathos and horror as they are of that indomitable human spirit, as powerful as the circumstances that seek to dwarf it.

The majority of works in the exhibition form a selection from Devi’s photographic study of Ramkinkar. It also con-tains Ramkinkar’s original paintings, his bronzes, draw-ings and pages from his sketch books from Devi Prasad’s collection. The exhibition is not simply one that looks at a sophisticated collector of Ramkinkar, but of one artist’s active participation in his master’s work by both helping him make the sculptures as a student and then photo-graph them exquisitely 40 odd years later.

Thus, the exhibition presents for the curator, a curi-ous stereoscopic focus: Ramkinkar and Devi Prasad. Ramkinkar’s sculptures and works are being seen literally refracted through the lens of Devi Prasad. His sculptures are also thus being curated in absentia, a predicament that would be faced by anyone interested in drawing at-tention to the large outdoor sculptures that were created to form an integral part of the Santiniketan landscape.

It is thus as much about the archiving of Ramkinkar as it is about Ramkinkar. It is about both artists’ works: Devi Prasad’s and Ramkinkar’s. It is about the relationship be-tween a master and a student. It is also about a collection and a collector. And finally it is also about seeing the com-mon sensibilities in sculpture and painting that underlie Ramkinkar’s work.

The entrance to the galleries is designed as the gently falling cement fondue that Ramkinkar is most known for. It thus takes the visitor right into the medium he used for his sculptures. A weakened cement slurry has thus been applied to the walls of the exhibition space, textured and built up to simulate as closely as possible a feeling of the medium of Ramkinkar’s work in public spaces. Situated in his medium on the concrete walls are paragraphs of text that introduce Ramkinkar, his role in Santiniketan and Devi Prasad.

It is also within this context that his largest sculptures, the Yaksha and Yakshini from the Reserve Bank of India are presented. Made of stone, they demonstrate his facility with a completely different medium, thus creating a dia-logue in grey between cement and stone. At 20 feet each, I have blown up Devi bhai’s photographs of the sculp-tures to nearly life-size. By hanging them in the stairwell of the gallery space, they can be appreciated closely by O

N T

HE

EX

HIB

ITIO

N’S

DE

SIG

N

The last gallery is devoted to a changing audio-visual installation, in which screenings of footage of interviews with the artist, scenes of him actually making some of the works, and of how other great masters such as Ritwik Ghatak, his or his contemporaries and students have viewed him. Interviews with them, or films they have made of his works are interspersed with stills of Ramkinkar’s many other sculptures not framed and shown in the curatorial selection in the other galleries. Also included in this section are personal photographs by Devi Prasad of his student days in Santiniketan between 1938 and 1944.

The ends of the partitions between the four main quadrants of the exhibition are conceived as pages. These are actually made up of sheets from Ramkinkar’s sketch books, or drawings that are palimpsest. Framed in glass on both sides, and suspended at the corners of the partitions, they are like loose pages that the reader turns into the next chapter of the Ramkinkar archive.

At every stage of the display, original works carefully collected by Devi, or those made in his presence or those gifted to him at important, private moments of a bond shared between a teacher and his disciple are inter-spersed with Devi’s photographs that literally show how he has chosen to archive and honour his mentor. It also privileges us with curatorial intervention to see painting and sculpture together which opens up in-sights into the artist’s work that the usually segregated displays prohibit.

At different stages of the exhibition, Ramkinkar’s words are quoted from published interviews he gave to his students or other writers. They reveal much about his personality and the spirit that guided the production of his works. They too, form a part of the archiving of Ramkinkar.

At various points in his life, but particularly from 1946 to 1948 Ramkinkar dabbled in theatre, trying his hand at set designing, make up and art direction. During this period he worked with eminent personalities like Balraj Sahni in plays like Shatranj ke Khiladi, and directed Rabindranath’s Banshori. In 1947 he provided art direction and even worked as a makeup artist for Rajshekhar Basu’s Bhushun-dir Mandir, and an adaptation of “Othello”.

Around the same period of time, Ramkinkar was invited by the Nepal government to sculpt a Nepal War Memo-rial. His work was exhibited along with Benodbehari’s, and two of his paintings were sent to Salon des Mere in Paris. In 1950, three of his works were exhibited at the Salon des Réalité Nouvelle at Paris. On account of the success of these works, Ramkinkar was made a member of the Lalit Kala Akademi in 1954, and soon after in 1955, he was invited by the Government of India to install the Yaksha - Yakshini in front of the Reserve Bank of India, New Delhi.

Ramkinkar Baij is one of the most important voices in the discourse on modernism in India. The National Gallery of Modern Art’s records state that he was born in 1910, this is probably not true. Although there is debate about the exact date, most sources indicate that he was born on the 25th of May 1906. Born in a poor family to Chandicharan Paramanik and Sampurna Devi in Jugipara village (Bankura District), he began making toys and drawings and sculptures of religious figures at a young age. His prolific talent was spotted by Ramananda Chattopadhyay who referred him to the Kala Bhavan in Santiniketan in 1925. There, nurtured by its spirit of creative freedom, he grew to becoming one of the triumvirate of visionary artists and art teachers, along with Nandlal Bose and Benodebehari Mukherjee.

In his work, he adapted and absorbed varied influ-ences and forms from all over the world, making them uniquely his own. Ramkinkar’s works are marked, on the one hand, by their spontaneity and careless abandon, and on the other, with rigorous intellectual practice. A recurring theme in his eclectic body of work spanning many styles and decades, is the simple and hardworking Santhals near Santiniketan, whose “infi-nite capacity for happiness” captivated him.

Perhaps his best known work, the Santhal Family (1938), is lauded by most art critics both for its aes-thetic quality of the dignified larger-than-life forms built out of common concrete, as well as for its treatment of socio-economic issues such as displacement, gender, urban migration, caste etc. His supreme genius as an artist was exceeded only by his profound humility as a human being. His contribution to art has helped define the nature of modernism in India; it has influenced and inspired the lives of many. Today, Ramkinkar Baij is regarded as valued national heritage. R

AM

KIN

KA

R B

AIJ

Santhal Family (outdoor sculpture) Cement fondue, 427 cm. Courtyard of Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan.

On the Way to Kankalitola (right view)Three men dragging a sheep to be sacrificed.Cement, 56 cm, year (?)Collection: Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan

It was also during this period that the famous sculpture the Mill Call was conceived and erected – milestones in the artist’s life, of no less import than the Santhal Family. How-ever, there are also notable absences in our attempts to archive the life of Ramkinkar. The latter five years he spent working on the Yaksha and Yakshini were, as far as one can gather from his friends and students, testing and exhaust-ing for him in every way. They had reduced him to penury and located him away from his habitat in Santiniketan. Lat-terly, he was made Professor and Head of the Department of Sculpture at Santiniketan.

The Government of India recognized his contribution to Indian art, and awarded him the “Padma Bhushan” in 1970. Following his retirement from Santiniketan in 1971, Ram-kinkar continued to work and was honoured and felicitated on several occasions by institutions like the Lalit Kala Akademi, Kala Bhavan, Visva Bharati and Karmi Mandali. These years also saw a great number of solo exhibitions of the artist arranged mostly by Kala Bhavan.

In 1978, Ramkinkar Baij became seriously ill and was un-able to walk. However, much of his paintings and sculp-tures traveled abroad. Having been hospitalized for well over two months, Ramkinkar created his final work, a clay idol of Durga on 25th July 1980. On August 2nd 1980, Ram-kinkar Baij was cremated at Santiniketan.

[‘Ramkinkar Vaij’ the English spelling he settled on in the end, was preceded for years, by his first name spelled as ‘Ramkinker’. He seldom conformed to the European custom of surnames. ‘Vaij’, is strictly speaking correct; however, it is generally written as it was colloquially pronounced, ‘Baij’. This catalogue uses ‘Ramkinkar Baij’.]

AbstractWatercolour on paperSigned and dated 18.7.1971 (in Bangla) although executed earlier. Collection: Devi Prasad Speed (outdoor sculpture)Reinforced cement concrete, h. 140 cm, 1954still incomplete till 1978 when photographedSantiniketan

A transformation in the artist’s status, the mechanical reproduction of art and the introduction of formal art schools and exhibitions had been initiated in India at the end of the nineteenth century. Early in the 20th century, when India was trying to navigate its way to find its own expression of modernity and national-ism, an educational establishment was set up in the rural locales of Bengal by Rabindranath Tagore. Conceptualised on an alternative mode of education, and inspired by a quest for identity in modern Indian art, Santiniketan’s idealistic artistic worldview was not limited to an art education derived from the Royal Academy as espoused by India’s colonial masters. In finding a cosmopolitan, modern and Indian voice, this institution explored an art language that engaged with India’s mythical, poetic, historical and contemporary milieu in a globally informed, ‘modernist’ language.

It is no doubt true that in the intellectual battle with colonialism, Santiniketan’s teachers and visionaries found allies among the Western avant-garde critics of urban industrial capitalism. However, for Tagore, the lineament for a discourse on an aesthetics of cosmopolitanism, were already strengthened by his interactions with Okakura Tenshin, the Japanese art historian and curator, in Calcutta in 1902. In the 20s and 30s, a shift in the Santiniketan aesthetic sited rural India as the antithesis to colonialism.

This ‘abode of peace’ was set up as a space for learn-ing, where students could learn under trees, beneath the open sky, away from the confines of closed classrooms, a learning process that laid emphasis on a revived ‘Guru-Shishya Parampara’. It was this milieu into which Ram Kinkar made his entry in a revolution-ary way, subverting various pre-existing established norms as student and teacher.

For the art-historian, in the disparate negotiations of modernity in the Indian context, the life and work of Ramkinkar are vital. He was not the only Santiniketan artist to be inspired by the sculpting of ‘labouring R

AM

KIN

KA

R, S

AN

TIN

IKE

TAN

AN

D M

OD

ER

NIS

M

Rabindranath Tagore(right view) Bronze, 1941,

His personal life, inspirations and varied influences are those of an Indian modernist who epitomises his age. He forms the bridge between local – global – local; he never once travelled abroad (save Nepal) although he assimilated the art traditions of the world albeit mediated via Santinik-etan. He never deviated from expressing his own ‘subaltern’ reality and was always cognizant of, and well versed in his history. His dynamic of play with styles, with medium and language refuse a singular categorization or any one high aesthetic definition. He called his attitude toward his art practice, a ‘sadhana’; he eschewed signing the majority of his works, freely distributed them to his well-wishers in an age when he was overwhelmingly aware of the gravity of authenticated authorship and the importance laid by modern artists and art historians on constructing hagio-graphical corpuses. And yet, there remains a fascinating set of anecdotal references, stray jottings and a prolific artistic output that testify to his humility, unconventionality, respect for and ease with the means he had chosen to live a life by. In these respects, he will always stand apart.

classes’ in Edouard Lanteri’s Modelling, or by a post-Bourdelle lyricism and yet, perhaps because of his character and background, his ‘Westernisation’ will remain the least criticized. While ‘primitivism’ (with its many qualifiers and variations) has been one of the cornerstones of early modernism, in Ramkinkar’s work, it is regarded as the honest portrayal of his reality. While equally engaged with the secularizing objectivity of modern art, Ramkinkar remained an active carver and painter of the religious.

The early twentieth century Vorticists’ claim ‘to es-tablish what we consider to be characteristic in the consciousness and form content of our time; then to dig to the durable simplicity by which that can be most grandly and distinctly expressed’, impacted various artists around the First World War. For Ramkinkar, like Brancussi, his peasant roots defined the nature of his modernism. And Ramkinkar was certainly aware of Brancussi’s belief that, ‘they are imbeciles who call my work Abstract; that which they call Abstract is the most realist, because what is real is not the exterior form, but the idea, the essence of things.’ Brancussi had been commissioned by the Maharaja of Indore to build a Temple of Meditation which fell through when he visited India in 1937.

In 1925 the Bauhaus had published Piet Mondrian’s views on neo-plasticism that elaborated how abstract art need not even begin from the representational. And the Bauhaus exhibition organized in Calcutta in 1922 by Tagore had, as is all too well known, a significant influ-ence in shaping the modernist sensibility in that region. The pathways opened up against much opposition in the early decades of the twentieth century by Jacob Ep-stein undoubtedly affected several important sculptors including Henry Moore and Ramkinkar. Like other post World War I modernists, Ramkinkar is celebrated for his use of cement, the common medium of our time. How-ever unlike them Ramkinkar saw no conflict in engaging with the traditional, historical or religious. His subject matter always remains rooted within his environment.

Potter, educationist, peace activist, photographer, painter, Devi Prasad graduated from Kala Bhavan, Rabindranath Tagore’s art school in Santiniketan in 1944 where he had the fortune of being a student of three great master artists: Nandlal Bose, Benodebehari Mukherjee and Ramkinkar Baij. He worked with Mahatma Gandhi from 1942 to 1947 and participated in various non-violent social reform movements such as the Quit India movement and Vinoba Bhave’s gramdaan amongst others, both before and after inde-pendence.

In 1944, he joined Gandhiji’s ashram, Sevagram, where he worked on child art and edu-cation and also edited ‘Nayee Taleem’ till 1962. He was Secretary General and later Chair-man of the War Resister’s International, London, from 1962 to 1975. Devi Prasad has published widely on peace studies, child education, Rabindranath and Gandhi. He has authored the history of the War Resister’s International, practical manuals for potters in the Indian environment and translations of seminal works in English, Hindi and Bangla.

In 1978, as Visiting Professor at Santiniketan he made a photographic study of Ram-kinkar’s sculptures. Ramkinkar was delighted with these photographs and personally inaugurated their first unveiling in Santiniketan in 1978 / 79. The majority of Devi’s pho-tographs were taken by artificial light in the dead of night to eliminate the noise around them and see them, unusually, just for their purity of form and strength. Many of the outdoor sculptures have since been covered to preserve them. These photographs are thus an invaluable documentation. But they are more than that: they are photographs taken by an artist of sculptures he saw being created before him by his teacher forty years earlier. These photographs were processed and rich emulsion prints were created in the darkroom at Santiniketan. They form the core of this exhibition.

Devi was awarded the Lalit Kala Ratna in 2007. DE

VI

PR

AS

AD

Yakshini A1953 – 56, Plaster of Paris maquette, h. 93 cmCollection: National Gallery of Modern Art, Delhi

Yakshini A(detail, front left close up)

Yakshini ECollection: National Gallery of Modern Art, Delhi

Yaksha C (front left view)1953 – 56, Plaster of paris maquette, 95 cmCollection: National Gallery of Modern Art, Delhi

Yakshini ECollection: National Gallery of Modern Art, Delhi

In 1954 Ramkinkar was selected over nine other sculp-tors to create two sculptures for the entrance of the independent nation’s new Reserve Bank of India (RBI). It was his most expensive and significant commis-sioned work that took ten years to complete rather than the stipulated five, reduced him to bankruptcy, cost double the original sum sanctioned and even raised some controversies in parliament.

The iconography of Yaksha and Yakshini harks back to the most ancient of Indian nature spirits, guardians, protectors and harbingers of fertility and prosperity. Ramkinkar’s assimilation of Indian sculptural history ranged over practically every kind of classical Indian sculpture. His early years had been spent making mythological figures in clay and with paint for the bazaar. His extensive travels around India in the late 20s had further enriched his art historical knowledge. He carved a relief of Sarasvati at the Modern School in Delhi in 1932, and made Sujata, known in Buddhist my-thology as the lady who brought the Buddha rice during his meditation, in 1934 – 35. For the first five years of his time after he received the commission to make the RBI’s Yaksha and Yakshini, he spent his time relentlessly creating exploratory studies and scrutinized them until he was saturated with their meaning. As Ramkinkar explained, “There was a different humanness in every era”, a different language of creative expression which kept changing.

Ramkinkar’s Yaksha looks leaner than traditional ones and holds a symbol of industry in one hand (a gear / spoked wheel) and a bag of money (like Kubera) in the other. His Yakshini holds a flower and grain. Yakshas T

HE

HU

MA

N F

OR

M

Yaksha B (after Parkham)1953 – 56, Plaster of paris maquette, 49 cmCollection: National Gallery of Modern Art, Delhi

Yakshini C1953 – 56, Plaster of paris maquette, 62 cmCollection: National Gallery of Modern Art, Delhi

and Yakshinis are non-sectarian, and were worshipped in myriad forms in ancient India by every cult. The bank being the very emblem of the necessary tool of the monetized modern world was thus flanked by non-sectarian, democratic images that embodied a popular belief system. A semiotics was thus cre-ated of modernism gesturing toward the public via a shared ancient mythology; an appropriate choice, in every way, for Ramkinkar’s interpretation for the new Bank. The two with primal strength and grace safe-guard India’s economic plans for industry, wealth and agriculture. At 24 feet each, they remain amongst the tallest and grandest sculptures in history.

While Yaksha and Yakshini demonstrate Ramkinkar’s assimilation of the mythical, the historical and the idealized body, this was in fact founded on a rigor-ous discipline of expressive life drawing, portraits and sculptures. The exhibition explores the muses, inspirations and contemporaries of Ramkinkar. Some of these are anonymous and offer an opportunity to speculate on who they may be.

His drawings bear a visceral strength of line, exact and uncompromising. As the artist Somenath Hore noted of Ramkinkar’s drawings of the nude, “They are incomparable… Like in a tiger’s paw, page after page they are strung together by an indefinable power… Ramkinkar has repeatedly incised his desired shape in a quick gesture.”It is a similar power that infuses his

Female figureClay, undated, h. 24 cmCollection National Gallery of Modern Art, Delhi

Nude (profile)Pen and ink on rice paper, 30.5 x 36 cmSigned and dated 18.7.1971 (in Bangla) although probably executed earlier. Collection: Devi Prasad

Nude studyPen and ink on paper, 17 x 26 cmUndated, initialed ‘R.K.’ on bottom right.Collection: Devi Prasad

Nude (frontal)Pen and ink on rice paper, 30.5 x 36 cmSigned and dated 18.7.1971 (in Bangla) although probably executed earlier. Collection: Devi Prasad

portraits. There is not a single work which is life-less or still. Seemingly static models are infused with energy rising up from their perches, moving not just outwardly but expressing a feeling.

He had already been making portraits of Indian national leaders during the Non-Cooperation Movement in the 1920s. In the mid 30s he be-gan making a series of other portraits. He made a portrait of the maestro, Baba Alauddin Khan when he stayed with him for fifteen days in 1935. Sculptures of Jaya Appaswami and Ganguly Moshai followed the year after and the bust of Tagore in 1938 (a subject he reverted to in 1941). Gandhi was commemorated after his assassina-tion in 1947. Paintings of Binodini, a student at Kala Bhavan are dated to 1948, while Radharani became his model from 1950 onwards.

Poet’s Head (Rabindranath Tagore)Bronze, h. 46 cm, 1938Collection National Gallery of Modern Art, Delhi

Kiran BaruaPlaster-of-paris, 40 cm, 1948–49Collection:National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Head of a Young Woman (Daniya Dalani?)Cement, 50 cm, 1948Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Jaya AppaswamiCement, 33 cm, 1936 Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Head StudyPlaster-of-paris, 32 cm, 1957Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Abanindranath TagoreBronze,25 cm,1944Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New DelhiRamkinkar made this portrait when Abanindranath came to Santiniketan as Vice-Chancellor after Rabindranath’s death.

Preeti PandeCement, 52.6 cm, 1939.Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Madhura SinghBronze,53 cm, 1949Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Portrait of Shankho Choudhuri’s MotherCement, size (?), year (?)Collection: Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan

A Head StudyCement, size (?), year (?)Collection: Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan

Dandi March BBronze, 48 cm, 1972Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi(a few casts of this sculpture were sold through Lalit Kala Akademi, including one in the collection of Devi Prasad)

Subhas Chandra Bose B (right view)Plaster-of-Paris, 1961 – 62, h. 104 cmCollection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Subhas Chandra Bose B (detail)Plaster-of-Paris, 1961 – 62, h. 104 cmCollection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Subhas Chandra Bose B (left view)Plaster-of-Paris, 1961 – 62, h. 104 cmCollection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi(Subhas Chandra Bose A, also in the same collection, on a horse and of similar size, shows him proud with his arms akimbo, rather than the victorious gesture of this version.)

Taking the narrative from the worldview, context, landscape and people in the previous sections, this section of the ex-hibition explores the personal: Mother and child, child and animal, family, love in innocence and purity.

There was jubilation for all the members of the Kala Bhavan family at the birth of Nandalal Bose’s grandson. The in-fant’s mother, the tall and beautiful Nivedita Bose brought the baby out for his first walk, and inspired Kinkar-da to create the Perambulator. A mother leans over the pram to see her baby who meets her gaze with his little feet raised. There is joyousness, and as ever, there is the subtlest cap-turing of mood. This most tender and human of qualities characterises much of Ramkinkar’s works.

Devi Prasad’s photographs of the Santhal Family focus our attention on the grittiness of the pebble infused cement fondue that was built up in his presence at Kala Bhavan in 1938. This was his first exposure to the scale of Ramkinkar’s imagination. It was instrumental in exposing him to the joy shared between the students and teacher in the process of building an artwork together. He recalls how this was all they focused on at the time rather than romanticising the work or theorising its place in or expression of modernist developments in India.

The monumental structure of Santhal Family, depicts strength and equilibrium, displacement and immigration of labour, and the family as the most consolidated unit even at the lowest unrecognized rung of the social ladder. The H

UM

AN

ISM

Boy with DogOil of canvas, Late 1930s, 60 x 85 cmSigned in Bangla on top leftCollection: Devi Prasad

PerambulatorBronze, h. 38 cm, early 1970sCollection: National gallery of Modern Art, Delhi(a few casts of this sculpture were sold through Lalit Kala Akademi, including one in the collection of Devi Prasad)

family marches forth seeking pastures anew, the husband balancing the weight of a child with their worldly possessions as he reaches toward his wife. The tall and dignified woman to balances their possessions in a basket on her head with a child at her hip; she assumes an untainted strength, proud in her stance and unaffected by her nudity. The Santhals are said to be like birds with invisible wings. In this singular concrete sculpture, Ramkinkar emblazoned with unique dynamism the Santhals as the representatives of earthy rural Bengal in the wake of urbanisa-tion and industrialisation. In addition to issues of case and gender, the sculpture stages the contradictions of modernism on the bodes of the Santhals not through dispossession (and never, in Ramkinkar’s case, through an anthropological gaze); but as a site of plenitude, fullness and purposefulness.

The exhibition juxtaposes the sculpture with an oil painting of a Santhal couple made in 1944. When Devi announced that the time had come to leave Santiniketan, Kinkar-da asked him to bring him some materials. On a square board, he painted the orange Santhal couple still united, the woman still holding up a basket, but the couple now in the midst of a blue grey urban context.

This section also focuses on four other paintings. The highly expres-sionistic painting of the Boy with Dog, shows a white boy striding in a mustard landscape breaking in portions to a grassy verdigris. The paint-ing immediately begs comparison with Ramkinkar’s first oil painting of 1938 titled Girl with dog, (NGMA collection, Acc. No. 4406). There too the protagonist is shown with a blue dog, except the girl is carefully con-textualised, enclosed within a garden a journal in which she would have been composing her jottings lies open beside her. Shorn of any context, the boy seems timeless and purposeful; the bond with his dog assum-ing centrality. The deftness with which the dog is painted enhance his volume, apart of course from showing the confident hand of a master.

Ramkinkar often showed the most erotic through abstraction. This can be seen in the photographs of his sculptures titled Mithuna A and Mit-huna B. The theme can also be seen in three watercolours of the same subject: Bee over Flower, which grow progressively abstract.

Horse and Its KeepersPlaster-of-Paris, 37 cm, late 1920s. Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Boy with Dog (detail)Oil on canvas

“In the garden of life I roam. What I see

– laughter, crying, small babies, flowers or

whatever, I paint. At the dark of night when

a child lies embracing my chest and when

I hold him tight, I give that strength to my

sculptures. What I see in the garden of life I

paint by the light of the day, what I touch in

darkness, I turn it into sculpture.”

– Ramkinkar

“I am a person with limitations, yet I am

an artist treading a great path which it

is impossible to walk without the spirit of

sadhana…mine is the imagination of a poor

young artist. There is one road open to me

and that is not to enter the worldly life.

There was no question of marriage although

I am not ungrateful to my parents. I remain

a bad boy in this respect”

– RamkinkarMother and Child (left view)Plaster -of-Paris, 25 cm, late 1920s. Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi.

Mother and Child (right view) Plaster -of-Paris, 25 cm, late 1920s. Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Santhal Couple in LandscapeOil on canvas board, March 1944, 30.5 x 35.5 cmCollection: Devi Prasad

“I am a person with limitations, yet I am an artist treading a great path which it is” – Prakash Das, 1991: p. 25 and Devi Prasad, 2007: 176

‘in the garden of life I roam…’drawn from the recollections of Benode-behari Mukherjee on Ramkinkar,, and first published by Prakash Das: 1989: pp. 167 – 73 and later in Devi Prasad, 2007: 187 – 192.

Santhal Family (outdoor sculpture) Cement fondue, 427 cm. Courtyard of Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan Santhal Family (detail)

Fruit Gatherers (front view)Cement, 93 cm, 1950Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Fruit Gatherers (back view) Cement, 93 cm, 1950Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Fruit Gatherers (detail) Cement, 93 cm, 1950Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Fruit Gatherers (detail) Cement, 93 cm, 1950Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Abstract, bee over flowerWatercolour on paper, painted on both sides of page, 13.5 x 18.25 cm, undatedCollection: Devi Prasad

Bee over flowerWatercolour on paper, 13.5 x 18.25 cm Signed and dated 18.7.1971 (in Bangla) although probably executed earlierCollection: Devi Prasad

Mithuna–ACement, 30 cm, 1931Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi. Mithuna–CBronze, 66.5 cm, 1949Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi or Santiniketan (?)

(obverse) Abstract, couplewatercolour on paper, dated 195427 x 37.5 cmCollection: Devi Prasad

(reverse) rural landscapeink drawing, 27 x 37.5 cmCollection: Devi Prasad

A Woman’s Torso (front left view)Cement, 79 cm (?), 1943Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi(made in response to the Bengal famine)

The famine of 1942 – 43 was devastating and prompted him to make poignant and har-rowing images of human suffering: skeletal corpses, forlorn starving mothers with children and begging bowls. The bas-relief Famine is also known by some as Highway, Kingsway and Rajpath.

Three watercolours with predominantly blue trees are included in this section. They were painted when Devi accompanied Ramkinkar to the Sal forest after a storm, a place where they had painted several times before. Broken trees occupy the main field of the landscape. These were painted early in the 1940s.

In 1944, Ramkinkar erected the Harvester (or Thresher), a triumphant cry of the power of human spirit over circumstance. A power as forceful as that of nature.

The Harvester evokes the powerfully rising human spirit conquering the great famine. Conflicting the reality of death, the woman threshing embodies an idea of plenitude. Ramkinkar’s Harvester is an image of woman’s strength as well as revolution. The ambiva-lence is clearly visible in the master sculptor’s approach, with this sculpture proposing an alternative vision of a return to nature as the only way out of the reigning barrenness. Like other works, a recurring subtext is the pure joy of being immersed in one’s work.

This attitude to work is most celebrated in Mill Call or Siren. The original, nearly three metres high, captures the vivacity of Santhal women as they go on their way to work. A gambolling boy follows, the wind caught in the woman’s cloth held over her head give the sculpture its finishing exuberance. The sculpture induces one to be view it in the round, and this feeling perfectly captured by Devi Prasad’s photo-graphs. SP

IRIT

AND

CIR

CUM

STA

NCE

On the Way to Kankalitola shows a reluctant crying sheep being led to sacrifice at Kali’s shrine by ear-nest devotees betrothed to their cause, unmindful of the anguish they cause. It was a preparatory work for a much larger sculpture that was to be placed before Department of Education at Visva Bharati, to serve as a reminder of the fallacy of dogma and unthinking ritualism. It was, as Devi Prasad says, “a witheringly sardonic comment on the humanity of the ‘devout’.”

The ink on rice-paper drawing of a strong Santhal woman leading a cow and her calf is expressive of the same energy he has imparted to many of his painted depictions of Santhal women. Preparatory pencil marks are to be found all over the page.

Famine (back view)Cement, 91 cm, 1943Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Famine (front close-up)

Famine / Rajpath (Kingsway)Cement bas-relief, size (?), 1943Collection: Santiniketan

Famine – girl with a dog (view from one side)Collection: Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan

Famine – starving beggarCement, 25 cm (?), 1943Collection: Santiniketan

Coolie MotherCement, 77 cm, 1942–43Collection: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Burden of the World (outdoor sculpture)Iron rods and cement fondue, 100 cm approxCollection: Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan

‘Death…’ – Derived from an interview given to Prakash Das, cited in devi Prasad, 2007: pp. 182

On the Way to Kankalitola (right view)On the Way to Kankalitola (detail: close-up of the men)

Three men dragging a sheep to be sacrificed.Cement, 56 cm, year (?)Collection: Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan

“I kept myself totally engrossed

in my work. I have always been

indifferent towards death; in

fact I have never thought of

death. Death can in no way

come near an artist as long as

he is completely involved in

creativity.”

– Ramkinkar

On the Way to Kankalitola (back view)On the Way to Kankalitola (left view)

Three men dragging a sheep to be sacrificed Cement, 56 cm, year (?)Collection: Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan

The Harvester Bronze cast (above)after the Cement fondue outdoor sculpture(a few casts of this sculpture were sold through Lalit Kala Akademi, including one in the collection of Devi Prasad)

The Harvester Cement fondue outdoor sculpture (right), 274 cm, 1943Collection: Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan

‘making sculptures under the open sky’ – Drawn from Prokash Das, ed. 1991: pp. 25 and 70 – 76, and in Devi Prasad, 2007: pp. 176, 178.

Woman leading a cow and calfInk and pencil on paper, 21 x 33 cmCollection: Devi Prasad

“Art is a matter of eternal dissatisfaction; it

is purposeless. Its function is not to propa-

gate anything. I make sculptures under the

open sky; but whose sculptures and of what?

Under whose order?! That is determined by

nature and the artist’s encounters with pain

and counter pain. Purposeless creativity is a

great financial burden. Artists by their very

nature remain poor, their purposeless work

keeps them in poverty. Hence they have to

depend on patrons and connoisseurs. That

happens on the mutual understanding

between the two. I was blessed by meeting a

great sage of purposeless creativity at San-

tiniketan…. I do what I like. One cannot go

on explaining and defining everything”

– Ramkinkar

Mill Call (front view, outdoor sculpture)Mill Call (left view)Mill Call (detail: close-up of top section)

Cement fondue, 292 cm, 1956.The sculpture stands in the Kala Bhavan courtyard.

The modernist quest for a utopia took on its own special character at Santiniketan. The Bengal School’s communion with their pastoral idyll was a powerful ideal guided by the philosophy of Tagore; it was also one that found resonance with Gandhi. The homestead, red earth, the Sal, Palash and Shimul trees, the storms that raged over them and their constant seasonal changes were the subject matter of the largest body of Ramkinkar’s works. It was that Santiniketan habitat in which he had blossomed; which in his day was still unspoiled, where he would go on picnics and painting trips with his students in the forest, swim in the river that went through the eroded red earth of the Khoai. It’s ideal of personal realisation through empathy with nature had widely impacted Rabindranath and Nandlal Bose.

Like the other artists at Santiniketan, Ramkinkar absorbed with felicity the Far Eastern styles of wash and gouache. Within a year and a half of his arrival at the Kala Bhavan, he was excelling in wash techniques with a superb command over line and finishes. Like Benodebehari, he was an avid reader of Rabindranath’s works. Both were trained by Nand-lal Bose who often asked them to sing Rabindranath’s songs on nature, and many have noted the quality of the poet in their paintings. Nandlal led them through multiple art styles, Eastern and Western, apart of course, from the many Indian traditions.

Thus his views of nature are on the one hand Far Eastern (The painting of butterflies over blossom and bamboo demonstrates this and is close to the work of his friend and colleague Benodebehari Mukherjee), at another, strongly reminiscent of Cezanne (as in the Nepal landscape) and many other formal English watercolourists (as in the many washes included herein). In his adoption of different styles – he defies a single classification of any one aesthetic. He adopted whichever style he needed, spontaneously respond-ing to whatever inspired him in his immediate environment. The core, or crux of the life-force in things is what he aimed to represent. This he accomplished with spontaneity and exactness, and therein lay his genius.

A PA

ST

OR

AL

UT

OPIA

Verdant Sal forestWatercolour on paper, 1942 – 44, 18 x 25.5 cmCollection: Devi Prasad

Storm over Sal forest Watercolour on paper, 1942 – 4418 x 25.5 cmCollection: Devi Prasad

Sal forest after the storm Watercolour on paper, 1942 – 4418 x 25.5 cmCollection: Devi Prasad (this is one of three similar paintings in the collection)

Landscape 2Watercolour on paper, erroneously dated 1929?26.5 x 37 cmCollection: Devi Prasad

Landscape 1Watercolour on paper, Dated 1972, although probably painted earlier27 x 37.5 cmCollection: Devi Prasad

Blossom after the stormWatercolour on paper, 1942 – 44, 38 x 27 cmsigned in Bangla on bottom rightCollection: Devi Prasad

Sal ForestWatercolour on paper, 1942 – 44, 18 x 25.25 cmCollection: Devi Prasad

Nepal landscapeWatercolour on paper, 17 x 23.75 cmCollection: Devi Prasad

LandscapeWatercolour on paper, Signed and dated 1972 on bottom right, although probably painted earlierCollection: Devi Prasad

Landscape drawingPen and ink on paper, 16 x 24 cmundated, initalled ‘R.K.’ on bottom rightCollection: Devi Prasad

LandscapeWatercolour on paperSigned and dated 1972 on bottom right, although probably painted earlierCollection: Devi Prasad

AbstractWatercolour on paperSigned and dated 1972 on bottom right, although probably painted earlierCollection: Devi Prasad

213.

Koushik, Dinker. Ramkinkar, Exhibition of Sculptures, Paintings & Sketches. Calcutta: BAAC, 1972.

Krishnan, S. A. Ramkinkar Vaij, Lalit Kala Journal, no. 1 and 2, April ’55 – March ‘56

The Man and the Artist - An Annual on Art and Aesthetics. Santiniketan: Department of History of Art, Kala Bhavan, Visva Bharati, 1990. Mitter, Partha Art and Nationalism in Colonial India 1850 – 1922, Occidental Orientations. Cam-bridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

The Triumph of Modernism: India’s Artists and the Avant Garde,1922-47. London: Reaktion Books, 2007.

Mukherjee, Benodbehari. Ramkinkar. Exhibition Catalogue. Santiniketan: Visva-Bharati Chattra Sammilani, 1960.

Chitra Katha. ed. by Kanchan Chakraverti. Kolkata: Aruna Prakashani, Ben-gali year 1390.

Prasad, Devi. Ramkinkar Vaij: Sculptures. New Delhi: Tulika Books & Kotak Mahindra, 2007.

Rabindranath Tagore: Philosophy of Education and Painting. New Delhi: National Book Trust, 2001.

“ Ramkinkar, A Tribute.” Art Heritage 9. New Delhi: Triveni Kala Sangam, 1989-90, 62.

“Ramkinkar and Santiniketan.” Visva Bharati Quarterly, Vol. 46, no. 1- 4, 1980-1981.

Ramkinkar Smaran. Special Issue, Visva Bharati News, September -October 1980.

Santosh, S. “Some Notes on Ramkinker.” Searching Lines: A Collection of writings around art, Vol. 3. Shantiniketan: Nandan Mela, Department of History of Arts, Kala Bhavan, 2004.

Sivakumar, R and Ghulam Mohammad Sheikh Benodbehari Mukherjee: Life, Context, and Work. Exhibition Catalogue for A Centenary Retrospective Exhibition. New Delhi: NGMA and Vadhera Art Gallery, 2006, 65- 133.

Sivakumar, R. Santiniketan: the Making of a Contextual Modernism. Exhibition Catalogue. New Delhi: NGMA, 1997.

“Remembering Ramkinker”: K.G.Subramanyam interviewed by R. Sivakumar. Art Heritage 9. New Delhi: Triveni Kala Sangam, 1989-90, 66.

Tagore, Rabindranath. My School. Shantiniketan: Visva Bharati Publication

Anand, Mulk Raj. Indian Contemporaries: Ramkinkar . Marg, Vol. XVI No I, December 1962, 36-38.

Appasamy, Jaya. Ramkinkar. Contemporary Indian Art Series. New Delhi: Lalit Kala Academy, 1961. Appasamy, Jaya. Ramkinkar: His contribution to Contemporary Art. LKC, No 22, September 1976, 25-27.

Appasamy, Jaya. Ramkinkar and Santiniketan. Santiniketan: VBQ Vol 46, Nos 1-4, May 1980-April 1981.

Appasamy, Jaya. Ramkinkar as a pathfinder. Bivbab, Special issue of Indian Sculpture, Oct.- Dec, 1983.

Baij, Ramkinkar: Self Portrait (translated from Bangla by Sudipto Chakraborty). Calcutta: Monchasa Publishing Project, 2005.

Bandyopadhyay, Somendranath Ramkinkar: Alapchari Silpi. (Conversations with Artist Ramkinkar). Calcutta: Dey’s Publishing, 1994.

Bharucha, Rustom. Another Asia, Rabindranath Tagore and Okakura Tenshin. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Bose, Nirmal Kumar. The Art of Ramkinkar Vaij. Hindustan Standard, October 1940.

CIMA Art of Bengal: Past and Present. Calcutta: Centre for International and Modern Art, 2000.

Das, Prokash.(ed) Ramkinker.(Bengali) Burdwan/Calcutta: A. Mukherjee & Co.Pvt.Ltd, 1991.

Ramkinker: Drawings. Calcutta, 1996.

Das Gupta, Anshuman Ramkinker Baij. Centenary Exhibition Catalogue for Exhibition at Nandan, Kala Bhavan, 15 – 25 January. Santiniketan, 2007.

Mathur, K S. Exhibition Catalogue for Exhibition of Sculptures Paintings and Sketches by Ramkinker, March 25-April 16, 1972, Birla Academy of Art & Culture, Calcutta. Also articles by Dinkar Kowshik; K. G. Subramanian; Prabhash Sen; Pronab Ranjan Roy; Jaya Appaswami and others.

Foucault, Michel. “Of other spaces”, Diacritics No.16, Spring 1986.

Guha-Thakurta, Tapati Monuments, Objects, Histories: Institutions of Art in Colonial and Post colonial India. New Delhi: Permanent Black, 2004

The Making of a New ‘Indian’ Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Kapur, Geeta. When Was Modernism? Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India. New Delhi: Tulika Books, 2000, 2007.

Katt, Balbir Singh. “Lyrical Dynamism in Ramkinkar’s Sculpture.” Rooplekha, Vol XVIII Nos 1-2, 210-

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cat and miceWatercolour on paper15.5 x 19.5 cmCollection: Devi Prasad

AbstractWatercolour and ink on paperInitialled ‘R.K.’ on bottom leftCollection: Devi Prasad