Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms, Intrusive Thoughts, Loss, and Immune Function After Hurricane Andrew

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms, Intrusive Thoughts, Loss, and Immune Function After Hurricane Andrew

Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms, Intrusive Thoughts, Loss, and Immune FunctionAfter Hurricane Andrew

GAIL IRONSON, MD, P H D , CHRISTINA WYNINGS, P H D , NEIL SCHNEIDERMAN, P H D , ANDREW BAUM, P H D ,

MARIO RODRIGUEZ, P H D , DEBRA GREENWOOD, RN, P H D , CHARLES BENIGHT, P H D , MICHAEL ANTONI, P H D ,

ARTHUR LAPERRIERE, P H D , HUI-SHENG HUANG, MD, NANCY KLIMAS, MD, AND MARY ANN FLETCHER, P H D

Objective: To examine the impact of and relationship between exposure to Hurricane Andrew, a severestressor, posttraumatic stress symptoms and immune measures.Methods: Blood draws and questionnaires were taken from community volunteer subjects living in thedamaged neighborhoods between 1 and 4 months after the Hurricane.Results: The sample exhibited high levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms by questionnaire (33% overall; 76%with at least one symptom cluster), and 44% scored in the high impact range on the Impact of Events (IES) scale.A substantial proportion of variance in posttraumatic stress symptoms could be accounted for by four hurricaneexperience variables (damage, loss, life threat, and injury), with perceived loss being the highest correlate. Of thefive immune measures studied Natural Killer Cell Cytotoxicity (NKCC) was the only measure that was meaning-fully related (negatively) to both damage and psychological variables (loss, intrusive thoughts, and posttraumaticstress disorder (PTSD). White blood cell counts (WBCs) were significantly positively related with the degree of lossand PTSD experienced. Both NKCC (lower) and WBC were significantly related to retrospective self-reportedincrease of somatic symptoms after the hurricane. Overall, the community sample was significantly lower inNKCC, CD4 and CD8 number, and higher in NK cell number compared to laboratory controls. Finally, evidencewas found for new onset of sleep problems as a mediator of the posttraumatic symptom - NKCC relationship.Conclusions: Several immune measures differed from controls after Hurricane Andrew. Negative (intrusive)thoughts and PTSD were related to lower NKCC. Loss was a key correlate of both posttraumatic symptoms andimmune (NKCC, WBC) measures.Key words: stress, disaster, hurricane, posttraumatic stress disorder, immunity, anxiety.

INTRODUCTION

On August 24,1992, Hurricane Andrew (a class IVhurricane with sustained wind speeds of 140 mph.)struck South Florida, causing more damage than anyother previous storm in the history of the UnitedStates. In the aftermath, an estimated $20 billion inproperty was lost (costing another $10 billion inclean-up), over 175,000 people were left homeless,and 120,300 jobs were affected (1). Thousands werewithout phone or electricity for several weeks orsometimes months. In the early aftermath, travelingwas nearly impossible because of downed trees andpower lines, the absence of street signs and trafficsignals, as well as copious broken glass and otherdebris. Constant vigilance ensued requiring protection

From the Departments of Psychology (G.I., C.W., N.S., M.R.,D.G., C.B., M.A., N.K., M.A.F.), Psychiatry (G.I., N.S., D.G., M.A.,A.L.), and Medicine (N.S., H-S.H., N.K., M.A.F.), University ofMiami, Coral Gables, Florida, and the University of PittsburghCancer Center (A.B., M.R.), Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Address reprint requests to: Gail H. Ironson, MD, PhD, Depart-ment of Psychology, P.O. Box 248185, University of Miami, CoralGables, FL 33124.

Received for publication December 20, 1994; revision receivedMay 8, 1996.

of property from looters, contacting and negotiatingwith insurance companies, finding contractors for re-building (who one hoped did not abscond with thedown payment), and having strange people in one'shouse (rebuilding) whose trustworthiness was uncer-tain. The area looked like a war zone, and the presenceof the 22,000 federal troops reinforced this image.

Damage and devastation of this magnitude may behypothesized to have a negative impact on mentalhealth, physiological indicators of stress includingimmune measures, and physical symptoms. Al-though there is a large literature on the mental healthsequelae of disasters (reviewed below), there is littleon their impact on the immune system. The presentstudy attempts to narrow this gap in the disasterliterature. In addition, we had the opportunity tostudy factors related to adjustment in a relativelyshort time frame (months) after the disaster.

REVIEW OF RELEVANT LITERATURE

Impact of Disasters on Mental Health/Distress

Several researchers have described stress responsesyndromes and the attendant sequelae of naturaldisasters. Horowitz (2) and Horowitz et al.. (3) notethat stress response syndromes most commonly in-

128 Psychosomatic Medicine 59:128-141 (1997)

0033-3174/97/5902-0128$03.00/0Copyright © 1997 by the American Psychosomatic Society

HURRICANE STRESS AND IMMUNITY

elude posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symp-toms, depressive states, and anxiety disorders. Mc-Farlane and Papay (4), in a study of firefighters 4,11,and 29 months after they had combatted bushfires,found PTSD symptoms, depression, and anxiety tobe sequelae in descending order, as did Shore et al.(5) in a study of Mt. St. Helens' victims. McFarlaneand Papay (4) found that the diagnosis of PTSD wasassociated with greater property loss, whereas affec-tive disorders were more associated with adversityin the aftermath of the disaster. Freedy et al. (6)found that loss of resources among victims of Hurri-cane Hugo was strongly associated with elevatedSCL-90 and PTSD scores. Horowitz et al. (3) alsodescribed both intrusive thinking and overwhelmingemotional flooding, and an inclination toward mal-adaptive denial and numbing of emotions in peopleadapting to traumatic events. Laube (7) pointed outthat victims of disaster typically experience recur-ring and distressing thoughts about the disaster andattempts to avoid thoughts and behaviors associatedwith the event. Baum (8) noted that these intrusiveimages or uncontrollable thoughts may play a role inmaintaining the stress and its effects long after thestressor is gone. Peterson et al. (9) noted that thesymptoms and course vary over time. Whereas in-tense initial reactions are likely to occur during theacute phase, psychological recovery often occurswith the passage of time (9, 10).

Impact of Stressors/Disasters on ImmuneMeasuresA number of stressors have been associated with

decrements in immune function: bereavement (11-13); being an Alzheimer's caregiver (14); divorce(15); being in a poor-quality marriage (15); and, ofmost direct relevance to the current study, thechronic stress associated with the Three Mile Islanddisaster (16) or the Northridge earthquake (17). Af-fective states often associated with stress, such asdepression (18), anxiety(12), and loneliness (19),have also been associated with decrements in im-mune function.

Immune decrements most often found in the abovestudies of stress effects have been functional mea-sures associated with cellular immunity. These in-clude, but are not limited to, decrements in mitogenresponsivity [blastogenic response to phytohemaglu-tinin (PHA) and pokeweed mitogen (PWM)], (11,12,15, 17), decreased Natural Killer (NK) cell activity(13, 15, 17, 18, 20), and increased titers to EpsteinBarr virus (EBV) (21). In addition, several studies

have noted decrements in cell phenotypes-T helper(CD4), and helper/suppressor cell ratios (15), T sup-pressor/cytotoxic (CD8) lymphocytes (16, 17), andNK cells (15, 16). Finally, Herbert and Cohen(21)noted an increase in WBCs in a meta-analyticreview of the literature on stress and immunity.

Proposed mechanisms for the impact of stress onthe immune system (reviewed in Ref. 22) includesympathetic nervous system products such as cat-echolamines which may impact the immune systemvia j3 receptors on lymphocytes (23), direct sympa-thetic noradrenergic innervation of lymphoid tissue(23), and hypothalamic pituitary adrenal productssuch as cortisol (24).

Immunologic Correlates of Posttraumatic StressSymptoms

Little work has focused on posttraumatic stresssymptoms or the cognitive and process variablesinvolved in recovery from traumas as they relate tochanges in the immune system. These may be par-ticularly important since they represent potentialtargets of therapeutic interventions. Workman andLaVia (25) found that intrusive thoughts related to animpending medical school examination were associ-ated with poorer blastogenic responses to PHAamong young, healthy medical students. Lutgendorfet al. (26) found, among college students participat-ing in a disclosure experiment, that a decrease in anavoidant style of cognitive processing over time aswell as higher levels of experiential involvement inthe disclosure process predicted decrements in EBVantibody titers (suggestive of better control of latentviruses). However, except for the McKinnon et al.(16) study, there is virtually no literature on theeffects or correlates of a natural disaster on theimmune system.

PurposeThe purpose of this study is to determine the

short-term impact of a major stressor, an overwhelm-ing natural disaster, on posttraumatic stress symp-toms and on the immune system. The relationshipamong three sets of variables is explored: a) hurri-cane experience variables (damage, loss, etc), b)post-traumatic stress symptoms, and c) immune mea-sures. Putative mediators of significant relationshipsfound are then considered. Finally, the relationshipbetween immune measures and self-report of so-matic symptoms is reported.

Psychosomatic Medicine 59:128-141 (1997) 129

G. IRONSON et al.

METHOD

Subjects

During 1 to 4 months after the acute event we interviewed andgathered data from 180 subjects living in the communities af-fected by the hurricane (specifically south of Kendall Drive inMiami). Subjects were recruited from a variety of source—wehanded out fliers about the study at neighborhood food stores,recruited staff from places of employment [such as Ryder, theUniversity of Miami, Florida International University), and wherewe knew someone in the neighborhood, our research team wouldknock on doors (or trailers). Thus this was a volunteer sample andnot a random sample. Although there would be benefits fromhaving a random sample, it was not feasible at the time. Manypeople were not living in their homes, phone service was out formonths in many affected areas, and since looting was present wethought residents might be alarmed or irritated by unknownresearchers knocking on doors. We did seek diversity by attempt-ing to get representation of different ethnic and socioeconomic(SES) groups and people who represented a wide range of damage.

Exclusion Criteria. Subjects were excluded if they had achronic disease directly impacting on the immune system (lupus,acquired immune disease syndrome (AIDS), etc.), if they werepregnant, or if they were taking a drug known to affect theimmune, sympathetic, or neuroendocrine systems (eg, pred-nisone, (3 blocker, etc.). Because excluding alcohol users mighthave biased the sample, we instead asked questions about alcoholuse to be used as a possible control variable in analyses (seemeasures section on substance use) If subjects had cold-relatedsymptoms at the time of the interview, collection of blood wasdelayed until the person was symptom-free (usually 1 week).

ProceduresParticipation in this study included: a) an interview lasting

approximately 1 hour; b) questionnaires taking approximately 2hours to complete; and c) a blood draw. Each subject was given achoice of being interviewed in the home, provided there was aplace where privacy was possible, or at the university. Thesession began by explaining the informed consent form, thenature of the study, confidentiality, and obtaining the subject'ssignature. Interview questions included demographics, the dam-age sustained to the home, injury to self and others, and questionsabout their experience of the hurricane. The subject was given thequestionnaire packet as well as instructions for completing it. Ata return visit, within a few days, the questionnaire was collected.At this visit, each subject's questionnaire was checked to makesure it was properly filled out and the participant was askedwhether they had any questions or difficulty with the question-naires. Blood was drawn for immune measures (55 ml.) after 10minutes of rest. The participant was then given a check for $60.00and thanked for participating.

AssessmentsHurricane Experience Variables. Damage. Questions were

asked in the initial assessment about specific damage to roof,windows, possessions, carpeting, car, and other damage. Eachquestion was asked on a 4-point likert scale ranging from nodamage (0) to complete damage (3). Cronbach's a was .78.

Loss of Resources. The initial assessment also included mea-

surement of loss of resources, in line with Hobfoll's (27) model ofstress. Hobfoll's conceptualization of resources is a very broad oneincluding four categories: material possessions, social roles (em-ployment, marriage, membership in organizations), self and worldviews (sense of meaning, purpose, feeling independent), andenergy resources (time, money, information). We began with thelist of 52 resources used by Freedy et al. (6) in their study ofresponses to Hurricane Hugo. We omitted all items that mightreadily be criticized as representing symptoms (of distress) ratherthan resources (eg, "feeling that my life is peaceful," "feeling thatI have control over my life"), and we added a few relativelyobvious items not on the original list (eg, car, boat). The resultinglist consisted of material resources and a few experiential re-sources (eg, time to spend in various ways, understanding fromone's employer, feelings of intimacy with family members), noneof which was transparently related to a posttraumatic stressmeasure, a was .94 for the scale.

Injury. Four questions were asked relevant to injury. Were youinjured? Did you see someone else get injured? Did you knowsomeone who was injured? Did any of your friends or family getinjured? Each question was answered yes or no. The total injuryscore was one if subjects answered yes to any of the above, or zerootherwise.

Life Threat. This question was intended to tap threat or fearduring the hurricane. On a one to seven likert scale, subjects wereasked to indicate the extent to which they felt they might dieduring the hurricane, with " 1 " representing "not at all" and highernumbers indicating greater perception of the threat of death (7 =absolutely).

Posttraumatic Stress Symptom Variables. Two measures ofposttraumatic stress symptoms were used: A posttraumatic stressdisorder (PTSD) scale and the Impact of Events (IES) scale(described below).

PTSD. The measure used for PTSD symptoms consisted of aseries of questions referring to how often each of the symptomstaken from the DSM III-R diagnostic criteria have occurred overthe past week. Our continuous measure of PTSD was the sum ofhow often (on a 0 to 4 scale, 0 = not at all, 1 = once only, 2 = 2-3times, 3 = 4—6 times, and 4 = every day) each symptom occurredin the last week [a for the continuous measure was .91). Totranslate the PTSD measure into categories we did the following:A symptom was scored as present if it happened at least once inthe past week (to define PTSD1) or at least twice in the past week(for calculating PTSD2). To consider a high level of symptoms ofPTSD as present, we then followed the DSM-III R (28) symptomcriteria for PTSD, ie, having at least one of four reexperiencingsymptoms, three of seven numbing/avoidance symptoms, andtwo of six heightened arousal symptoms ("high level of symp-toms" used the PTSD2 scoring). It should be noted that althoughwe used the DSM-IIIR symptoms, the DSM-IIIR allows a longertime frame (present in the last month) than we did (present in thelast week).

Impact of Event Scale IES. Intrusive and avoidant thoughtswere measured by the Impact of Events Scale (IES; 29) a 15-itemself-report instrument which has been employed to assesschanges in cognitive processing of stressful events in prior work(30). It includes an Intrusion subscale that taps the extent towhich rumination regarding the stressor has broken throughinto consciousness over the past week, while an Avoidancesubscale assesses the degree to which the subject avoidedthoughts and actions reminiscent of the stressful event over asimilar period.

Immunologic Measures. Immunologic measures included Nat-ural Killer Cell Cytotoxicity (NKCC), total white blood cell (WBC)

130 Psychosomatic Medicine 59:128-141 (1997)

HURRICANE STRESS AND IMMUNITY

counts, differential for calculation of lymphocyte counts, andenumeration of peripheral blood lymphocyte phenotypes (CD4,CD8, CD56). All blood draws occurred between 7 and 11 AM, inorder to control for diurnal variation. Blood was maintained atroom temperature before assay. Flow cytometry and NKCC assayswere begun the same day as the draw, while serum was stored forlater assay of neopterin.

Flow Cytometry (used to quantify CD4, CDS, and CD56 pheno-types). A single laser flow cytometer (EPICS Elite, Coulter Instru-ments Laboratories, Hialeah, FL) was used with a whole blood,two-color analysis procedure as previously described to deter-mine the distribution of lymphocyte phenotypes (31-33). Thefollowing pairs of fluorescence isothiocyanate (FITC) or phyco-erythrin (PE) conjugated monoclonal antibodies (Coulter Immu-nology) were selected: T4-PE combined with T3-FITC to measureCD4 expressing cells which also express the T cell marker CD3,for CD4+ or helper/inducer cells (34); T8-FITC (CD8) combinedwith T3-FITC or suppressor/cytotoxic T cells (35); Mo2-PE forCD14+ or monocytes (36) combined with KC56-FITC (CD45) todetermine leukocytes and proper settings for lymphocyte gates;T3- FITC recognizing CD3, a marker of mature T cells andNKH.l-PE (CD56) which defines the entire pool of mononuclearcells with NK activity (37) and for defining the CD3+ and CD3-CD56+ cells. Isotypic controls are mouse IgGl, IgG2, or IgM(Coulter Immunology, Hialeah, FL).

Whole blood, 100 ml, is incubated with the antibodies for 10minutes at 23"C after shaking. Erythrocytes were lysed andwashed using the Quick Prep System from Coulter Epics. Stainedspecimens were run on the Epics Elite flow cytometer using the488 nm laser line for quantification of percent positive cells bydirect immunofluorescence. For the lymphocyte markers of Tcells and subsets, bit maps were set on the lymphocyte populationof the forward angle light scatter versus 90° light scatter histo-gram. The NKH.1+ (or CD56) cells were measured in a large bitmap encompassing the lymphocyte and monocyte area of theforward angle light scatter vs. 90° light scatter histogram. Thegranulocyte area was excluded. Percent positively stained cellsfor each marker pair, as well as doubly stained cells weredetermined using the QuadStat software (Coulter Epics).

Peripheral lymphocyte counts were calculated by multiplyingthe total white blood cell count and percentage of lymphocytesas determined from a Coulter MaxM automated hematology in-strument. Estimates of absolute numbers of the lymphocyte ormononuclear cell populations positive for the respective surfacemarkers were determined by multiplying peripheral lymphocyteor mononuclear cell counts by percentage positive cells for eachsurface marker (31).

NK Cell Cytotoxicity (NKCC). Natural killer (NK) cell functionwas evaluated by determining cytotoxicity using the whole bloodchromium release assay as outlined in detail in Refs. 30, 37).The target cell line utilized is the NK sensitive erythroleukemicK562 coil-line. The assay was done in triplicate, at four effector totarget cell ratios with a 4 hour incubation. The percent cytotox-icity at the four effector to target ratios and the number of CD56 +cells per unit of blood was used to express the results as percentcytotoxicity at a target to effector cell ratio of 1:1 as previouslydescribed (31). Kinetic Lytic Units/NK cell (KLU/NK) were alsocalculated as previously indicated (31) in order to estimate themaximum number of targets lysed by each NK cell during the4-hour assay.

Neopterin. Neopterin, a major product of immune activation,was measured by a radioimmunoassay (INCSTAR). Abnormallyhigh levels of this substance have been found in autoimmunediseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease and early

onset autoimmune diabetes mellitis, in viral infections associatedwith organ transplants and HIV-1 disease (39). Neopterin levelsappear to be associated with disease severity, with the highestlevels occurring during the acute phase of these diseases. Neop-terin was measured as a control variable in order to excludesubjects with the above diseases or acute infection. (In our sampleneopterin mean = 2.52, SD =1.35, and was significantly corre-lated with self-report of aching and swollen joints; r = .20).

Somatic Symptom Report. Subjects were asked to indicatewhich of 38 somatic symptoms (eg, respiratory, gastrointestinal,infectious, pain, fever, etc.) they had experienced in the monthbefore the questionnaire (after the hurricane) as well as before thehurricane, a was .83. Subjects were also asked whether theirgeneral health was better, the same, or worse post- vs. pre-hurricane.

Preliminary Analysis and Consideration ofControl VariablesA number of variables were considered as possible covariates

representing potential confounds needing statistical control: theyare noted in the respective regression sections. Before data anal-ysis, distributions were examined for nonnormality and outliers.Outliers were individually checked. Several subjects were elimi-nated from analyses because their values may be indicative of anundetected underlying chronic illness (eg, CD4/CD8 ratio < 1,neopterin > 8). One subject was eliminated after a check ofoutliers revealed she could not read English.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics.

Our sample ranged in age, schooling, income,ethnic composition, and gender as indicated in Ta-ble 1. Participants in the study averaged 21.4 dayswithout phone (SD.= 25.5, range = 0-90 days) and24.0 days without electricity (SD = 18.0, range =0-90 days). Although we interviewed 180 people,we collected completed questionnaires from 173subjects, and blood draws from 167. Dates for theassessments ranged from 1 to 4 months posthurri-cane (Sept. 29, 1992 through Dec. 21, 1992). How-ever, because of technical reasons, NKCC was onlyobtained beginning Oct. 20. (Samples sizes are givenin tables.) Those who had complete data were com-pared to those with missing physiological data for allvariables including demographics. No systematicbias was present (1/20 comparisons significant).

Hurricane Related Variables.Hurricane Experience Variables. Damage. As

noted in Table 1, the range of damage representedwas wide (mean = 10.1, SD = 3.6). Three subjectsreported no damage at all. About one third of the

Psychosomatic Medicine 59:128-141 (1997) 131

G. IRONSON et al.

TABLE 1. Description of SampleDemographics

GenderMaleFemale

Age (yr)18-2425-3940-5455-71

EthnicityWhiteBlackHispanicOther

EducationSome high schoolHigh school graduateSome college/advanced vocational trainingCollege degreeGraduate degree

Annual Household Income ($)< 10,00010,000-20,00020,000-30,00030,000-40,000>40,000

Home OwnershipRentOwnOther

Living Situation (at first interview)Same as beforeMoved elsewhere

Hurricane-Related VariablesDamage

0-5 low6-910-1314-18 high

Other (mean ± SD)Days since hurricaneDays without electricityDays without phoneWeeks to insurance (rebuilding check)

InjuryTo selfSaw injuryKnow someone injuredFriends/family injuredAny of above

Thought would dieNoYes (some extent)

PTSD2 Symptoms (£2/wk)PTSD DSM-IIIRReexperiencing ClusterNumbing ClusterArousal ClusterNo Cluster

Impact of Events ScaleLow (<8.5)Medium (8.6-19.0)High (>19.0)

35%65%

16%40%30%14%

44%34%18%4%

5%14%37%26%18%

8%17%18%22%35%

33%62%

5%

60%40%

13%18%42%27%

82 (24)24(18)21 (26)

8.8 (7.5)

28%7%

32%10%53%

46%54%

33%58%42%70%24%

31%25%44%

sample had mild damage or less, a little less than onethird had major damage, and the rest had moderateto major damage.1 In addition, at the time of theinterview, 40% of the sample were living some-where other than the place of residence at the time ofthe storm. For those who had damage and insurance,mean time to the first big insurance check for re-building was 8.82 weeks (SD = 7.46).

Loss. As noted in the assessment section, wemodified the list of 52 resources used by Freedy et al.(6) in their study of responses to Hurricane Hugo, sothat it would not be confounded with our outcomemeasures. However, because this is a modified in-strument, it cannot be directly compared with otherstudies. The mean and standard deviation of ourmeasure, composed of 42 items scored on a zero tofour scale was 44.1 (29.6).

Injury. As noted on Table 1, 53% of the sampleanswered yes to one or more of the four injuryquestions. Most of the injuries were minor (22 wentto the doctor, 1 was hospitalized).

Life threat. As noted, this question was intendedto tap threat or fear during the hurricane. A highpercentage responded yes (54%), to some extent (<0) they thought they might die.

Distress/Posttmumatic Stress Symptoms. Meansand standard deviations for the two measures usedto describe posttraumatic stress symptoms (ie, PTSDsymptoms; IES) are given in Table 2. Each of themeasures may be summarized by categories as well.

PTSD Symptoms. Using the PTSD2 categorization,one third of our sample had a high level of PTSDsymptoms (ie, met the DSM-III-R criteria by ques-tionnaire but with the 1-week time frame).2 Even

1 A damage score of 5 represents mild damage (eg, part of roofover one room gone and one or two windows broken, no loss offurniture or carpet, some possessions damaged, car still driveablewith one window broken and slight body damage). A score of 10,representing moderate damage, reflected having a portion of one'sroof gone (some rooms not habitable, but home is still habitable),half of one's windows broken, loss of some furniture or carpet(less than half of the house), lost possessions, and car needingbody repair with two or more windows broken. A score of 15,representing major damage included major roof damage (homenot habitable), more than half of windows broken, more than halfof furniture or carpet ruined, more than half of possessions lost,and a cai that was not driveable due to hurricane damage.

2 The PTSD2 categorization requires that for a symptom to bepresent it must occur two or more times in the past week. Wethink this most closely approximates the DSM IIIR intent of"persistent" symptoms. However, we also calculated PTSD1,which requires a symptom to occur at least once in the pastweek to be counted as present. Using this more liberal criteria48% of the sample has PTSD, 75% have the reexperiencing

132 Psychosomatic Medicine 59:128-141 (1997)

HURRICANE STRESS AND IMMUNITY

TABLE 2. Descriptive Statistics for Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms for Entire Sample and High Damage Group

Measure

PTSD

NIES total

NIES avoidant thoughts

IES intrusive thoughts

M

15.7"(14.9)b

6013.3a

(14.4)57

6.0"(7.3)7.3a

(8.9)

Entire Sample

F

21.6(14.1)11223.9

(16.2)110

11.2(9.4)

12.7(8.6)

Total

19.6(14.5)172

20.2(16.3)167

9.4(9.1)10.8(9.0)

M

19.0(16.4)3116.8a

(16.3)30

7.7a

(7.9)9.1a

(10.5)

High Damage

F

23.3(14.6)6925.2

(15.8)6611.9(9.1)

13.4(8.5)

Total

22.0(15.2)100

22.4(16.4)9610.4(8.9)11.9(9.3)

' Male and female means are significantly different.1 Numbers in paretheses are standard deviations.

TABLE 3. Associations Between Hurricane Experience Variables and Mental Health/Posttraumatic Stress Outcomes

HurricaneExperience

DamageLossLife threatInjury

ControlsMultiple R/R2

Fdf

P

Posttraumatic StressDisorder

r1

.24**

.65**

.29**

. 29 "

None.67/.44

29.94150.0000

-.20**.65**.09.11

All".69A48

16.508143.0000

Avoidance

r1

.17*

.43**

.28**

.08

None.46/.219.854146.0000

-.09.39**.13

- .07

Allb

.55/307.448139.0000

Impact of Event Scale

Intrusion

f

.22**

.51**

.36**

.24**

None.56/32

16.924146.0000

-.10.46**.18**.06

All".61/38

10.488139.0000

f

.22**

.52**

.36**

.18**

None.57/32

17.234146.0000

Total

/3"

- .10.48**.17*.00

All".64/.41

11.918139.0000

11 Zero order correlation.b Controlling for age, gender, and SES (education, income).* p < .05; ** p < .01.

morenoticeable is the high percentage of subjectswho had at least one symptom cluster (76%). Themost prevalent cluster was heightened arousal, fol-

(continued from previous page)

cluster, 52% have numbing, and 82% have arousal. Only 12%have no cluster.

In a separate validation study (with the Hurricane Andrewpopulation at a later time point (N = 45) we compared SCIDdiagnosis by trained interviewer to the PTSD questionnaire diag-nosis (with T. Mellman, MD, and D. David, MD). Using the moreconservative questionnaire criteria (PTSD2) there was 84% agree-ment (K=.62, sensitivity=.60, specificity = .97); with the liberalquestionnaire criteria scoring (PTSDl) there was 80% agreement(K = .57, sensitivity = .80, specificity = .80). The number ofsubjects in that study identified as meeting SCID criteria for PTSDwas 15, which was between the number identified with PTSDusing the conservative questionnaire criteria [N = 10) or theliberal questionnaire criteria [N = 18). Therefore in the currentsample 33% with PTSD by questionnaire (PTSD2 scoring) islikely conservative and using interpolation the best estimateappears to be approximately 42%. Finally, the high specificity of

lowed by reexperiencing, and lastly numbing. Alsoof interest is the gender difference in prevalence;36% of women and only 25% of men fell in the highlevel of PTSD symptoms category. This finding iscorroborated by a comparison of means for men andwomen on the continuous PTSD measure, whichshows that women had higher scores than men,(£(168)= -2.56, p = .01). The gender difference re-mained significant even when controlling for dam-age (partial r = .16, t=2.12, p - .04), although adirect comparison of male and female PTSD scoresrestricted to the high damage group (above the mean)was not significant.

IES. As noted, the IES scale measures both intru-sive and avoidant thoughts. Using cutoffs suggestedby Horowitz (40), 44% of our sample had a high

the conservative questionnaire scoring (.97) suggests that mosteveryone identified by the PTSD2 scoring would have PTSD bythe SCID.

Psychosomatic Medicine 59:128-141 (1997) 133

G. IRONSON et al.

symptom level, 25% had a medium symptom level,and 31% had a low symptom level. As with thePTSD measure, women scored significantly higherthan men in this sample on both the total IES score(£(163) = -4.14, p = .01), the avoidant thoughts (AV)subscale (£=3.64, p = .01), and the intrusivethoughts (INTR) subscale (£=3.73, p = .01). Thesedifferences remained significant in the high damagegroup, and when damage was controlled for in aregression equation.

Overview of regression strategy. In the regressionanalyses that follow we wanted to determinewhether there was a meaningful relationship amongthree subsets of variables: the hurricane experiencevariables (damage, loss, etc.), posttraumatic stresssymptoms and immune measures. The model entersthe hurricane experience variables as a block into theregressions with each outcome variable (PTSD, IES,the five immune measures) as a dependent variable.It was done this way to control for type I error.Correlations between any two of the subsets aregiven in Tables 3 and 5 and in the next sections.

Associations Between Hurricane Experience Vari-ables and Distress/Posttraumatic Symptoms. As canbe seen in Table 3, all of the hurricane experiencevariables (damage, loss, life threat, injury) correlatesignificantly with both PTSD and IES (except thatinjury was not significantly correlated with IESavoidance). Perceived loss was the strongest corre-late in all cases. j3 weights (shown in Table 3 formodels predicting distress from the hurricane expe-rience variables controlling for demographic vari-ables age, gender, and SES (41); time since hurricanewas virtually uncorrelated with either PTSD (.04) orIES (.03) in this narrow time frame and thus was notcovaried) suggest that only gender, damage, and lossadd uniquely to the other variables in the model forpredicting PTSD, and only gender, loss and lifethreat add uniquely to the other variables in themodel for predicting IES total and IES intrusion.Regression results show that between 32% and 44%of the variance in mental health outcomes (IES andPTSD respectively) can be explained by knowing thefour hurricane experience variables, and that thispercent of variance explained increases to 41% and48% for IES and PTSD, respectively, when age,gender, and SES are controlled for in the model.

Immune FindingsImmune Outcome Measures Compared With Lab-

oratory Controls. Table 4 compares our sample to

TABLE 4. Comparison of Hurricane Andrew Sample WithPrehurricane Laboratory Normal Controls

ImmuneMeasure

Hurricane LaboratoryAndrew Sample Controls

WBC/mm3

NKCC%b

CD56/mm3

CD4/mm3

CD8/mm3

156

129

129

156

156

6,231(2,573)a

29.9(13.9)332(215)865(288)427(184)

6,780(1,700)

38.4(14.7)236

(131)1,150(415)688(275)

70

71

72

70

70

NSC

<.001

<.001

<.001

<-001

a Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations.b Calculated at an effector to target cell ratio of 1:1.c NS, not significant.

laboratory controls3 on NKCC and phenotypic im-mune measures. The hurricane sample was signifi-cantly lower on NKCC (£[198] = 4.15, p < .001)compared with the laboratory controls. Natural Killercell (NKHl = CD56) number was significantly higherposthurricane (£[199] = -3.45, p < .001), whereas bothCD4 number (£[224] = 5.96, p < .001) and CD8 (£[224]= 8.39, p < .001) number were significantly lower inthe community posthurricane sample compared withthe laboratory controls. Finally, there was no signifi-cant difference between the hurricane sample and thelaboratory controls on WBCs.

Associations Between Hurricane Experience Vari-ables and Immune Measures. For each immunemeasure a regression model was performed withdamage, loss, life threat and injury (entered as ablock in order to control the Type I error rate) asvariables representing the hurricane experience. Ofthe five immune measures only NKCC showed asignificant relationship to the four hurricane ex-perience variables [F(4,103) = 3.60, p < .01]; theyexplained 12% of the variance in NKCC (r = .35).Damage and Loss were both significantly correlatedwith NKCC (r = -.27, p < .01; r = -.20, p < .05,

3 As noted in Table 4, there were 72 laboratory control subjects.These subjects were screened to be healthy (no chronic illnesses)and free of medication that might affect the immune system. Onlycontrols assessed before the hurricane were included, to be surethis sample was not affected by the hurricane; laboratory proce-dures were identical (ie, NKCC was run on the day of the blooddraw). Although there were 36 men and 36 women, laboratorycontrols were proportionately weighted by gender for the analy-ses; two-thirds female, one-third male, to match the hurricanecommunity sample.

134 Psychosomatic Medicine 59:128-141 (1997)

HURRICANE STRESS AND IMMUNITY

respectively).4 Life threat was marginally significant[r = -.17, p < .10). Damage had the highest standard-ized j8 (= -.19, NS) although no variable addedunique variance to the other three.

Two groups of immune control variables wereconsidered. The first were those that could not beaffected by the disaster (time since hurricane, age,gender, and race): none were related to the immunemeasures. The second were those that could bealtered by the hurricane, and thus could be consid-ered as controls or mediators (substance use-alcohol,caffeine, tobacco; sleep problems, exercise, timewithout food, time without electricity). These weresignificantly associated with immune measures: to-bacco was associated with higher WBCs (r = .39, p <.01) and higher CD4 number (r = .23, p < .01), andsleep change (new onset sleep problems) was asso-ciated with lower NKCC (r = -.25, p < .01). Analysisof sleep change as a mediator of the relationshipbetween damage or post traumatic stress symptomsand NKCC is presented in a section below.

Immune Correlates of Posttraumatic Stress Symp-toms. Finally the correlations between the two dis-tress measures and immune measures were calcu-lated and tested for significance. Of the five immunemeasures and two distress measures (PTSD and IES)only the distress correlations with NKCC and WBCswere significant. These are shown in Table 5. BothPTSD and IES were correlated negatively with NKCCin the entire sample. It is interesting to note thatwhile both PTSD and IES were significantly corre-lated with NKCC in the entire sample, the relation-ships between posttraumatic stress symptoms andNKCC were stronger in the high damage subsample.We then examined which symptom cluster of PTSD(reexperiencing, numbing, or arousal) might be con-tributing most to the lowered NKCC. No consistentpattern emerged. In fact the pattern was not consis-tent between the entire sample and the high damagegroup. With regard to the IES subscales, however,intrusive thoughts appeared to be more stronglyrelated to lower NKCC than avoidance. Only PTSDwas significantly positively related to higher WBCsin the entire sample, although in the high damagegroup both PTSD and IES symptoms were strongly

TABLE 5. Correlations Between Posttraumatic StressSymptoms, Natural Killer Cell Cytotoxicity (NKCC}, and WBCs

4 For subjects with damage and insurance we also correlatedtime to first big check from the insurance company and found it tobe significantly correlated with lower NKCC (r = -.27, p = .05,N = 54). This variable was not incorporated into the main analysisbecause it was only relevant for the subset of participants who hadboth damage and insurance, but is nonetheless of relevance in thisstudy.

Stress Symptom

PTSDReexperiencingNumbingArousal

IES TotalAvoidanceIntrusion

* p < .05; ** p <

Correlations with NKCC and WBC

NKCC

EntireSample

( N = 129)

- .20*; - .18*

- .16- .19*- .23*- .15- .26**

.01.

HighDamage(N = 75)

- .36**- .40**- .36**- .23- .32*- .26*- .32**

WBC

EntireSample

(N = 156)

.22**

.15

.19*

.24**

.09

.11

.04

HighDamage(N = 88)

.28**

.22*

.20

.33**

.24*

.22*

.21*

positively related. The arousal symptom cluster con-tributed the most to the PTSD-WBC relationship,and follow-up regressions in both the entire sampleand the high damage group indicated that reexperi-encing and numbing did not add significantly abovearousal.

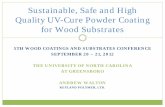

Group Comparisons. In order to better interpretthe potential importance of the significant correla-tions found between damage, the psychological vari-ables and NKCC, (and to better estimate how muchNKCC could possibly be impacted by damage andpsychological factors) mean differences were calcu-lated between contrasting groups: Subjects were di-vided by thirds on damage or the psychologicalvariables into high, medium, or low groups. NKCCvalues for the top third and bottom third are picturedin Figure 1. NKCC for the high damage group (X =27.7,) was significantly lower than NKCC for the lowdamage group (X = 36.0^ £(80) = 2.86, p < .01). NKCClevels for low impact (X = 36.0), and high impact(X = 27.5) groups on the IES scale (using Horowitzclassification) were also significantly different (£(87)= 2.75, p < .01). NKCC levels for low intrusivethoughts (X = 37.9), and high intrusive thoughts(X = 26.6) groups on the IES subscale, were alsosignificantly different_(£(78) = 3.70, p < .01). NKCClevels for low PTSD (X = 33.8), and high PTSD (X =26.1) were also significantly different (£(76) = 2^77,p < .01). High and low loss groups (X = 28.5, X =31.9) were not significantly different (£(86) = 1.28,p = .21). It is interesting to note that the highdamage, high IES, high intrusive thought, highPTSD, and high loss groups are all significantlydifferent from the laboratory control group (damagef(116) = 4.18, p < .001, IES £(126) = 4.31, p < .001,intrusive thoughts £(116) = 4.33, p < .001, PTSDt(115) = 4.70, p < .001, loss £(117) = 3.87, p < .001),whereas the low damage, low IES, low intrusive

Psychosomatic Medicine 59:128-141 (1997) 135

G. 1RONSON et al.

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

1 1

1 1

1 1

1 1

Up

1Lab Andrew Low High Low High Low High

Normals Sample Damage PTSD IntrusiveAndrew Sample Andrew Sample Thoughts

Andrew Sample

Fig. 1. Natural killer cell cytotoxicity in community sample after Hurricane Andrew compared with laboratory normals.

thoughts low PTSD groups are not (damage t(104) =.81NS, IES t (101) = .77NS, intrusive thoughts r(102)= .17NS, PTSD f(101) = 1.55NS). This suggests thatthere are groups of people within the affected areawhose NKCC was relatively protected from the ef-fects of the hurricane.

Regression Predicting NKCC From Hurricane Ex-perience Variables and Posttraumatic Stress Symp-toms. We then combined our two sets of variables(hurricane experience variables and post traumaticstress symptoms) in a regression model to determinewhat proportion of variance in NKCC could beaccounted for with this full model. With all of thevariables in the model, 14% of the variance in NKCCcould be explained (12% from the hurricane experi-ence block entered first and an additional 2% fromadding PTSD and IES), F(6,101) = 2.84, p = .014.The highest £ was for damage (= -.23, t = - 2.02, p =.05). Repeating this analysis in the high damagegroup indicated the full model explained 18% of thevariance in NKCC, F(6,59) = 2.18, p = .05. Thehurricane experience block contributed 10% of thevariance (which is likely less than in the full samplebecause damage is restricted in range to the highdamage group), and the posttraumatic distress blockcontributed an additional 8%.

Exploration of Mediators of NKCC Relationships.Finally, we wanted to explore possible mediators ofthe significant relationships between NKCC and thehurricane experience and the posttraumatic distressvariables. We first focused on the damage - NKCCrelationship as that was the strongest of the hurri-cane experience variables. Possible mediators that

were considered were posttraumatic stress symp-toms, the immune controls (previous section, Asso-ciations Between Hurricane Experience Variablesand Immune Responses) that could be affected bythe hurricane, and loss, since it could be conceptu-alized as resulting from damage. Only four possiblemediators (PTSD, IES intrusion, sleep change, andloss) met our first criteria which was that all threevariables (predictor, outcome, and mediator), shouldhave significant correlations with each other. Themediator effect was then tested by path analysisutilizing regression (42). First a regression analysiswith the outcome variable (NKCC) as the dependentvariable and the predictor as the independent vari-able (damage) was performed. Second, the depen-dent or outcome variable (NKCC) is regressed onboth the predictor (damage) variable and the media-tor. A variable is a mediator if the )3 weight for themediator in the second regression is significant, andthe /3 weight for the previously significant predictoris not significant in the second regression equation,ie, the predictor is a significant one until the medi-ator is added in. The four possible mediators (PTSD,IES, loss, and sleep change) were tested and nonesatisfied the criteria for a mediator.

Two other relationships which were found in thisstudy (PTSD-NKCC) and (IES thoughts-NKCC) weretested for mediators. Since sleep change was a cor-relate of NKCC we therefore explored whether it mayhave been a mediator of the relationship betweenPTSD and NKCC or between IES thoughts andNKCC. The path diagrams are presented in Figure 2.Since all sleep changes posthurricane had a negative

136 Psychosomatic Medicine 59:128-141 (1997)

HURRICANE STRESS AND IMMUNITY

(-.20*)-.12 nsPTSD • • NKCC

(-.25") -.22*

IES TOTAL

Sleep Change

(-.23*)-.18 nsNKCC

(-.25**) -.19*

Sleep Change

Fig. 2. Path diagram model for testing direct and indirect effectsof posttraumatic stress symptoms on NK cytotoxicity:Exploration of possible mediators. (Numbers in paren-theses are correlations; numbers outside parentheses arestandardized /3 coefficients in models with NKCC as thedependent variable PTST or IESTOTAL and sleepchange as independent variables.)

impact, the findings indicate that new onset of sleepproblems had some mediating effect in explainingthe relationship between both PTSD and IESthoughts on the one hand and lowered NKCC on theother. Sleep change was measured by three itemstaken from the SCL-90 (a=.8O; trouble falling asleep,awakening in the early morning, sleep that is restlessor disturbed). Although significant, the effects arenot particularly strong as is indicated by the smallsize of the correlation coefficients.

Immune-Somatic Symptom Relationships. Fi-nally, in order to explore the possible clinical signif-icance of immune measures, self-report of the so-matic symptom count (after minus retrospectivereport of before the hurricane) was correlated withimmune measures: a greater increase in symptomsafter the hurricane was associated with lower NKCC(r = -.18, p< .05, N = 129), higher WBCs (r = .17,p < .05, JV = 156), and higher CD56 number (r = .18,p < .05, JV = 129). Similarly, reported health changefor the worse was significantly associated with lowerNKCC (r = -.21, p < .05) and higher WBCs (r = .24,p < .05, JV = 149). Overall, more of our samplereported feeling worse after the hurricane (20%),then better (6%), while 74% reported feeling thesame. Subjects reported almost twice as many symp-toms after the hurricane (mean = 6.90, SD. =5.90) asbefore with a mean increase of 2.92 symptoms (SD.= 5.69).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this paper was to determine theimpact of an overwhelming natural disaster, Hurri-cane Andrew, on posttraumatic stress symptoms(PTSD and IES thoughts), and on the immune sys-tem. The impact on this sample of hurricane victimsincluded a much greater prevalence of PTSD symp-tomatology than the general population (43-45), andan elevation of intrusive and avoidant thoughts asindicated by scores on the subscales of the IES. Ourfirst major finding relates the hurricane experiencevariables to the severity of posttraumatic stresssymptoms, and emphasizes the importance of per-ceived loss. Our second major finding relates greaterhurricane experience and the posttraumatic stresssymptoms to immune measures, in particular lowerNKCC.

Psychological Findings

Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms. Our posthurri-cane sample exhibited a high level of posttraumaticstress symptoms (33% met DSM IIIR PTSD criteriaby conservative questionnaire scoring, but with a 1week time frame) and an elevation of intrusive andavoidant thoughts as indicated by scores on thesubscales of the IES measure (44% in the highimpact range). It is important to note that heightenedsymptom reports are to be expected shortly after atrauma, usually abate with time and do not neces-sarily indicate pathology. Our high damage grouphad IES scores similar to those in the acute phase (<6 months) of other traumas—those with high damagein the Parsons flood 4 months postdisaster (49% inthe high impact range(10)) and HIV positive menafter they have had 5 weeks to adjust to their diag-nosis (30). Norris (46), however, notes the occur-rence of PTSD symptoms varies depending on thespecific trauma. The volunteer nature of our samplelimits the inference about the percent of the generalexposed community that truly had PTSD symptoms.A related study using a quota sampling strategy 6months after Hurricane Andrew estimated 24% metcriteria for PTSD using the Mississippi Scale (57).

Correlates of Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms. Re-gression results show that between 32% and 44% ofthe variance in mental health outcomes (IES andPTSD, respectively) could be explained by knowingthe four hurricane experience variables (damage,loss, life threat, and injury) and that this percent ofvariance explained increases to 41% and 48% forIES and PTSD, respectively, when age, gender, andSES are controlled for in the model.

Psychosomatic Medicine 59:128-141 (1997) 137

G. IRONSON et al.

Of the hurricane experience variables considered(damage, loss, life threat, and injury), perceived losswas the most strongly related to posttraumatic stresssymptoms (the PTSD measure and IES), corroborat-ing previous findings by Freedy (6, 47) in studies ofHurricane Hugo and the Sierra Madre earthquake. Itis particularly interesting that perceived loss was astronger correlate than actual damage. This variablewas derived from Hobfoll's (27, 58) theory that linksthe experience of stress to the loss or threatened lossof resources. Recall that resources are conceptual-ized broadly, including psychological qualities suchas a sense of mastery or self-esteem, social roles(work, home, etc.), and physical entities such as ahome, car, clothing, and money. This finding, how-ever, must be interpreted with caution, becausealthough we attempted to make sure the measure ofperceived loss (modified from Freedy) did not havethe same items as our posttraumatic stress outcomemeasures, more distressed subjects may report bothmore psychological symptoms and more loss. Thusloss report may be influenced by both actual loss anddistress. Future studies might attempt to measureloss more objectively (such as number of neighborswho moved out, etc.) to avoid this potential con-found. (The self-report bias is shared by the otherquestionnaires as well, so the suggestion to attemptto measure other constructs objectively also applies).On the other hand, to the extent that loss may beviewed conceptually as involving appraisal, onemight want to include the self-report bias. In addi-tion, future studies might measure rumination overloss, as Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow (48) havefound rumination to be related to stress symptomsafter the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Finally, notall studies have found loss to be the strongest corre-late of distress; Thompson et al. (49) found that lifethreat and injury were more highly correlated withdepression, anxiety, and somatization than personalor financial loss after Hurricane Hugo.

It is also interesting to note that experience (dam-age) was a more important variable for PTSD symp-toms, but fear (life threat) was a more importantvariable for disturbing thoughts (IES intrusion andavoidance). Finally, the low correlation betweeninjury and the posttraumatic stress outcomes may bebecause most injuries in our sample were minor.

Of the demographic variables, gender was a signif-icant correlate of both PTSD and IES symptoms, withwomen reporting more symptoms than men. Al-though other studies have noted this finding inepidemiologic samples (43, 45), the current findingmust be interpreted with caution because the samplewas a volunteer sample. In addition, although

women reported more distress in this sample, therewere no gender differences in immune measures.

Immune Findings. NKCC. The finding that NKCCis lower in the hurricane sample compared to labo-ratory normals is consistent with a growing body ofliterature on stress and immunity (21) showing thatnaturalistic stressors such as bereavement (13), mar-ital disruption (15), and the Northridge earthquakeover time (17) have been associated with lowerNKCC. In our sample, damage was the variable moststrongly related to lowered NKCC, with the highdamage group exhibiting significantly lower NKCCas compared with the low damage group. Interest-ingly, lowered NKCC was also meaningfully relatedto a number of psychological variables—greater re-ported loss of resources, greater PTSD symptoms,and greater intrusive thoughts. The latter may beimportant due to the potential modifiability ofthoughts through therapy. It is also interesting tonote that these correlations were stronger whenconsidered in the high damage group only.

Several variables were explored as possible medi-ators of the relationship between post-traumaticstress symptoms and NKCC. Some support wasfound for the notion that new onset of sleep prob-lems, a symptom often associated with PTSD andintrusive thoughts, could act in this manner. Thesefindings are in agreement with the Irwin et al. (50)study, where partial sleep deprivation in humansreduced NKCC. However, there remained much un-explained variance in NKCC in the present study so,at best, sleep problems are explaining only part ofthe picture. It is interesting to note that the associa-tion between the more objective measure of hurri-cane experience (damage) and NKCC was slightlystronger (r = —.27), than between a self-report mea-sure (PTSD) and NKCC (r = -.20), which is veryconsistent with the Herbert and Cohen's (21) meta-analytic review where they found the NKCC associ-ation to be -.36 and -.23 with objective and self-report measures, respectively. Finally, it is interestingto note that the NKCC difference between high andlow damage groups (5.8%) was very similar to thedecrease pre- to postserostatus notification for HIV-positive men (6%; 30) suggesting some consistencyin the stress response in very different situations(NKCC was lowered approximately 25% in both).

Although stress clearly is related to loweredNKCC, determining the implications for disease isdifficult, particularly in a healthy population such asthe present one. Although we did find an associationof lower NKCC with self-report symptom increasepost-hurricane, this must be interpreted with cau-tion, since objective measures of actual symptoms

138 Psychosomatic Medicine 59:128-141 (1997)

HURRICANE STRESS AND IMMUNITY

were not taken. NKCC may be important in somediseases, including progression of cancer, chronicviral infections, autoimmune diseases (51), andChronic Fatigue Syndrome(CFS; 52). Most of theevidence for the importance of NKCC in disease islinked with cancer (53) and, in fact, a higher cancermortality rate has been found in victims of naturaldisasters(54). Finally, a related study found CFSsymptom exacerbations after Hurricane Andrew(55).

Other immune findings. The observed positivecorrelation of PTSD and loss of resources with in-creased WBCs is consistent with Herbert and Co-hen's meta-analytic review (21), indicating an asso-ciation of stress with increased WBCs, although wedid not find mean differences between the hurricanegroup and the normal controls.

The observed greater numbers of NK cells in thehurricane group as compared with the normal con-trols may possibly serve as a compensatory mecha-nism for the lowered NKCC. The results differ fromthose of McKinnon et al. (16), who reported lowerNK cells after the TMI accident, compared to acontrol group. However, they defined NK cells usingthe Leu 7 marker (CD57) surface marker, which isnot recommended for enumeration of NK cells (56).It should also be noted that their study took place 6years after the accident, and the sample size wassmall [N = 12 in the TMI group, N - 8 in the controlgroup). The Herbert and Cohen meta-analytic reviewfound a nonsignificant association between stressand NK cell number (effect size = -.07).

Our finding of lower T suppressor/cytotoxic cellsin the hurricane sample vs. normal controls is con-sistent with the meta-analytic review (21), the McK-innon et al. paper (16), and the Northridge earth-quake over time(17). In fact, Herbert and Cohenfound a large effect size for this measure (-.39 for allstress combined). Our sample also showed signifi-cantly lower T helper cells, which is consistent withthe meta-analytic review, but not with the McKin-non et al. study (16) which found no differences witha small sample and thus limited power.

Implications. Implications for disaster relief in-clude the targeting of resource loss (includingmoney, supplies, etc.), the provision of advice forresource replacement, education regarding normal-ization of symptoms that are expected to occur posttrauma, the maintenance of social roles as a resource(work, family, community), and the normalization ofsleep. The finding both that negative (intrusive)thoughts and an anxiety disorder (PTSD) are relatedto altered immune function including lower NKCC isof particular relevance for mental health profession-

als because of the potential modifiability ofthoughts. Reduction in intrusive thoughts can be oneof the targets of treatment paradigms not only fordistress considerations but also for their potentialimportance due to the linkage with immune functionand reported health.

Finally, the course of long-term psychological re-covery and adjustment and its relationship to im-mune recovery remain for future longitudinal stud-ies. A longitudinal study also allows for theinvestigation of direction of causality which was notpossible in the current cross-sectional study.

This work was supported by Grants MH40106 andT32 MH18917 from the National Institute of MentalHealth. The authors wish to thank Elizabeth La-Torre, Kathy Gamber, Ron Gamber, and Jovier Evansfor their help in the conduct of the study, and T.Mellman and D. David for sharing and Dean Cruessfor analyzing the validity data presented in footnote3.

REFERENCES

1. The Miami Herald: The Big One: Hurricane Andrew. KnightRidder, 1992

2. Horowitz MJ: Stress response syndromes, 2nd edition. North-vale, NJ: Jason Aronson Press, 1986

3. Horowitz MJ, Stinson C, Field N: Natural disasters and stressresponse syndromes. Psychiatric Ann 21(9):556-562, 1991

4. McFarlane AC, Papay P: Multiple diagnoses in post traumaticstress disorder in the victims of a natural disaster. J Nerv MentDis 180(8):498-504, 1992

5. Shore JH, Tatum EL, Vollmer WM1 Psychiatric reactions todisaster: The Mount St. Helens experience. Am J Psychiatry143(5):590-595, 1986

6. Freedy JR, Shaw DL, Jarrell MP, Masters CR: Towards anunderstanding of the psychological impact of natural disas-ters: An application of the conservation of resources stressmodel. J Trauma Stress 5:441-454, 1992

7. Laube MJ: The professional's psychological response in disas-ter: Implications for practice. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment HealthServ 30(2):17-22, 1992

8. Baum A: Stress, intrusive imagery, and chronic distress.Health Psychol 9(6):653-675, 1990

9. Peterson K, Prout M, Schwarz R: Posttraumatic stress disor-der: A clinician's guide. Plenum, NY, 1991. (Chapter titled:Subtypes and course of the disorder, 43-60)

10. Steinglass P, Gerrity E: Natural disasters and posttraumaticstress disorder: Short-term versus long term recovery in twodisaster-affected communities. J Appl Soc Psychol 20:1746-1765, 1990

11. Bartrop R, Lazarus L, Luckhurst E, Kiloh L, Penny R: De-pressed lymphocyte function after bereavement. Lanceti:834-836, 1977

12. Linn BS, Linn MW, Jensen J: Anxiety and immune respon-siveness. Psych Reports 49:969-970, 1981

13. Irwin M, Daniels M, Smith TL, Bloom E, Werner H: Impaired

Psychosomatic Medicine 59:128-141 (1997) 139

G. IRONSON et al.

natural killer cell activity during bereavement. Brain BehavImmun 1:98-104, 1987

14. Kiecolt-Glaser J, Glaser R, Dyer C, Shuttleworth E, Ogrocki P,Speicher C: Chronic stress and immunity in family caregiversof Alzheimer's disease victims. Psychosom Med 49:523-535,1987

15. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Fisher LD, Ogrocki P, Stout JC, SpeicherCE, Glaser R: Marital quality, marital disruption, and immunefunction. Psychosom Med 49:13-34, 1987

16. McKinnon W, Weisse CS, Reynolds CP, Bowles CA, Baum A:Chronic stress, leukocyte subpopulations, and humoral re-sponse to latent viruses. Health Psychol 8:389-402, 1989

17. Solomon G, Segcrstrom S, Grohr P, et al: Shaking up immu-nity: Psychological and immunologic changes following anatural disaster. Psychosom Med, 59:000-000,1997

18. Irwin M, Caldwell C, Smith T, Brown S, Schuckit M, GillinC: Major depressive disorder, alcoholism, and reduced natu-ral killer cell cytotoxicity. Arch Gen Psychol 47:713-719,1990

19. Kiecolt-Glaser J, Ricker D, George J, Messicak G, Speicher C,Garner W, Glaser R: Urinary cortisol levels, cellular immuno-competency, and loneliness in psychiatric inpatients. Psycho-som Med 46:15-23, 1984

20. Levy S, Herberman R, Lippman M, d'Angelo T: Correlation ofstress factors with sustained depression of natural killer cellactivity and predicted prognosis in patients with breast can-cer. J Clin Oncol 5:348-352, 1987

21. Herbert TB, Cohen S: Stress and immunity in humans: Amota-analytic review. Psychosom Med 55:364-379, 1993

22. Antoni M, Schneiderman N, Fletcher MA, et al.: Psychoneu-roimmunology and HIV-1. J. Consult Clin Psychol 58(1),38-49, 1990

23. Felten D, Felten S, Carlson S, Olschawka J, Livnat S: Norad-renergic and peptidergic innervation of lymphoid tissue.J Immunol 135(Suppl 2):755s-765s, 1985

24. Cupps T, Fauci A: Corticosteroid-mediated immunoregula-tion in man. Immunol Rev 65:133-155, 1982

25. Workman EA, La Via MF: T-lymphocyte polyclonal prolifer-ation: Effects of stress and stress response style on medicalstudents taking national board examinations. Clin Immunoland Immunopathol 43:308-313, 1987

26. Lutgendorf S, Antoni M, Kumar M, Schneiderman N: Changesin cognitive coping strategies predict EBV-antibody titrechange following a stressor disclosure induction. J Psycho-som Res 38(l):63-78, 1994

27. Hobfoll, SE: Conservation of resources: A new attempt atconceptualizing stress. Am Psychol 44:513-524, 1989

28. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, ThirdEdition-Revised. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric As-sociation, 1987

29. Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W: Impact of event scale: Ameasure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 4l(3):209-218,1979

30. Ironson G, LaPerriere A, Antoni MH, Klimas N, Schneider-man N, Fletcher MA: Changes in immune and psychologi-cal measures as a function of anticipation and reaction tonews of HIV-1 antibody status. Psychosom Med 52:247-270,1990

31. Fletcher MA, Baron G, Ashman M, Fischel M, Klimas N: Useof whole blood methods in assessment of immune parametersin immunodeficiency states. Diagn Clin Immunol 5:69-81,1987

32. Fletcher MA, Azen S, Adelsberg B, et al.: The TransfusionSafety Study Group: Immunophenotyping in a nulticenter

study: The Transfusion Safety Study experience. Clin Immu-nol Immunopathol 52:38-47, 1989

33. Parker JW, Adelsberg B, Azen, SP, Boone D, Fletcher MA,et al.: The Transfusion Safety Study Group: Leukocyte immu-nophenotyping by flow cytometry in a multisite study: stan-dardization, quality control and normal values in the Trans-fusion Safety Study. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 55:187-220, 1990

34. Reinhertz EL, Kung PC, Goldstein G, Schlossman SF: Separa-tion of functional subsets of human T cells by a monoclonalantibody. Proc Ntl Acd Sci USA 76:4061-4065, 1979

35. Reinhertz EL, Kung PC, Goldstein G. Schlossman SF: Amonoclonal antibody reactive with the human cytotoxic/suppressor T cell subset previously defined by a heteroantiserum TH2. J Immunol 134:1301-1307, 1980

36. Todd RE, Agthoven AV, Schlossman SF, Terhorst C: Struc-tural analysis of differentiation antigens MO1 and MO2 onhuman monocytes. Hybridoma 1:329-337, 1982

37. Hercend T, Griffin JD, Benussan A, et al.: Characterization oftwo natural killer cell associated antigens, NKHla and NK2,expressed on subsets of large granular lymphocytes. J ClinInvest 75:932-943, 1985

38. Deleted in proof.39. Fuchs D, Hausen A, Reibnergger G, Werner ER, Dierich MP,

Wachter H: Neopterin as a marker for activated cell mediatedimmunity: Application in HIV infection. Immunol Today9(5):150-155, 1988

40. Horowitz MJ: Stress response syndromes and their treatment.In L. Goldberger & S. Breznitz (Eds.) Handbook of stress:Theoretical and clinical aspects. New York Free Press, 1982

41. Gibbs MS: Factors in the victim that mediate between disasterand psychopathology: A review. J Traum Stress 2(4):489-514,1989

42. Baron R, Kenny D: The moderator-mediator variable distinc-tion in social psychological research: Conceptual strategicand statistical considerations. I Pers Soc Psychol 51(6):1173-1182, 1986

43. Helzer JE, Robins LM, McEvoy L: Post traumatic stressdisorder in the general population: Findings of the Epidemi-ologic Catchment area survey. N Engl J Med 371:1630-1634,1987

44. Davidson JRT, Hughes D, Blazer DG, George LK: Post trau-matic stress disorder in the community: An epidemiologicalstudy. Psychol Med 21:713-721, 1991

45. Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E: Traumaticevents & posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban populationof young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48:218-222, 1991

46. Norris FH: Epidemiology of trauma: Frequency and impactof different potentially traumatic events on different demo-graphic groups. J Consult Clin Psychol 60(3):409-418,1992

47. Freedy JR, Saladin ME, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, SaundersBE: Understanding acute psychological distress followingnatural disaster. I Traum Stress 7(2):257-273, 1994

48. Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J: A prospective study of depres-sion and post traumatic stress symptoms after a naturaldisaster: the Loma Prieta earthquake. ] Pers Soc Psychol61:115-121, 1991

49. Thompson N, Norris F, Hanacek B: Age differences in psy-chological consequences of Hurricane Hugo. Psychol Aging606-616, 1993

50. Irwin M, Mascovich A, Gillin J, Willoughby R, Pike J, Smith T:Partial sleep deprivation reduces natural killer cell activity inhumans. Psychsom Med 56(6):493-498, 1994

140 Psychosomatic Medicine 59:128-141 (1997)

HURRICANE STRESS AND IMMUNITY

51. Whiteside TL, Bryant J, Day R, et al.: Natural killer cytotox- chronic fatigue syndrome are exacerbated by the stress oficity in the diagnosis of immune dysfunction: Criteria for a Hurricane Andrew. Psychom Med 57(4):310-323reproducible assay. J Clin Lab Anal 4:102-114, 1990 56. Whiteside TL, Rinaldo CR, Herberman RB: Cytolytic cell

52. Klimas N, Salvato F, Morgan R, Fletcher MA: Immunologic functions, hi Ross NR, DeMacario EC, Fahey JL et al.: (Eds),abnormalities in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Clin Microbiol Manual of Clinical Laboratory Immunology, 4th ed American28:1403-1401, 1990 Society for Microbiology.. Washington, DC, 1992

53. Whiteside TL, Herberman RB: The role of natural killer cells 57. Thompson MP, Perilla JL, Norris F: PTSD in a multi-culturalin human disease. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 53:1-23, 1989 community 6 months following Hurricane Andrew. Poster pre-

54. Bennett G: Bristol floods. Controlled survey of effects on sented at the 9th annual meeting of the International Society forhealth of local community disaster. BMJ 3:454-458, 1970 Traumatic Stress Studies. San Antonio TX, Oct. 1993

55. Lutgendorf S, Antoni MH, Ironson G, Fletcher MA, Penedo F, 58. Hobfoll SE: Traumatic stress: A theory based on rapid loss ofBaum A, Schneiderman N, Klimas N: Physical symptoms of resources. Anx Res 4:187-197, 1991

Psychosomatic Medicine 59:128-141 (1997) 141