Policing The Text: Structuralism’s Stranglehold on Australian Language and Literacy Pedagogy

-

Upload

westernsydney -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of Policing The Text: Structuralism’s Stranglehold on Australian Language and Literacy Pedagogy

This article was downloaded by: [University of Western SydneyWard]On: 14 August 2011, At: 18:19Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number:1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 MortimerStreet, London W1T 3JH, UK

Language and EducationPublication details, including instructionsfor authors and subscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rlae20

Policing the Text:Structuralism'sStranglehold onAustralian Language andLiteracy PedagogyMegan Watkins

Available online: 29 Mar 2010

To cite this article: Megan Watkins (1999): Policing the Text: Structuralism'sStranglehold on Australian Language and Literacy Pedagogy, Language andEducation, 13:2, 118-132

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09500789908666763

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching and privatestudy purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply ordistribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied ormake any representation that the contents will be complete oraccurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae

and drug doses should be independently verified with primarysources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions,claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with orarising out of the use of this material.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f W

este

rn S

ydne

y W

ard]

at 1

8:19

14

Aug

ust 2

011

Policing the Text: Structuralism’sStranglehold on Australian Language andLiteracy Pedagogy

Megan WatkinsSchool of Teaching and Educational Studies, University of WesternSydney-Nepean, NSW 2747, Australia

Language and literacy pedagogy is a hotly contested site. Various theoretical perspec-tives jostle for dominance with the needs of teachers and students very often givenlittle consideration within the debate. In Australia, ‘structuralist’ approaches to text, inparticular those based on systemic functional theory, are clearly in the ascendancy.Their dominance is evident in syllabus documents and curriculum material acrossAustralia. While this move has led to a more explicit teaching of literacy than was thecase during the 1970s and 1980s when more naturalistic methodologies prevailed, thestructuralist notion of text which frames these approaches is having a marked effect onclassroom practice. Text is generally understood as type, a taxonomic conglomerate offormulaic stages. In teaching text as such teachers problematically assume the role of‘textual police’ ensuring students understand and reproduce these textual ‘rules’. Thispaper is based upon a recent study of the implementation of such an approach to textin primary school classrooms. It examines the pedagogic practice of one teacher,highlighting the impact of a restrictive and reductive approach to text on her teachingmethodology.

IntroductionStructuralism ¼ spring[s] from the ironic act of shutting out the materialworld in order the better to illuminate our consciousness of it. For anyonewho believes that consciousness is in an important sense practical,inseparably bound up with the ways we act in and on reality, any such moveis bound to be self-defeating. It is rather like killing a person in order toexamine, more conveniently, the circulation of the blood.

(Eagleton, 1983: 109)

Structuralism has had a major impact on Western thought. While it can takemany forms it is understood here as a theoretical perspective on the study ofhuman culture aimed at identifying constraining patterns or structures andwhich accounts for individual phenomena only in terms of their relation to otherphenomena within a systematic structure (Milner, 1991: 61). Its modus operandi isthe objectification of practice to allow for the identification of rules, and so theformulation of a system. While Eagleton refers to this as a ‘self-defeating’ activity,such a strategy can be beneficial. It is necessary to recognise the existence ofstructural constraints, but the issue is how they are conceptualised and to whatextent they are seen as constraining. If structures are viewed as all determiningthis produces only rigid formulaic analyses of the social: no allowance is madefor change and individual practice is ignored. The system is then a closed

118

0950-0782/99/02 0118-15 $10.00/0 ©1999 M. WatkinsLANGUAGE AND EDUCATION Vol. 13, No. 2, 1999

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f W

este

rn S

ydne

y W

ard]

at 1

8:19

14

Aug

ust 2

011

construct, an entelechy that reduces agents to mere automata, in a senseproducing the lifeless result suggested by Eagleton.

Such a critique of structuralism is hardly news. The pervasiveness ofpost-structuralist thought would seem to negate any need to articulate thisstructuralist problematic, yet in Australia, structuralism seems to have gainedsomething of a stranglehold in the field of language and literacy education.1 Thiscomment, however, needs some explanation. In actuality classroom practice isvaried and complex. A range of theoretical perspectives and contingent factorsinfluence what teachers do but in the realm of syllabus formulation andcurriculum design structuralist approaches to text based upon systemic func-tional theory clearly dominate.2 This use of the term ‘structuralist’ to refer tosystemic functional theory, however, could appear as something of a misnomerwithin the discipline of linguistics. A clear distinction is often drawn betweenstructural and functional schools, primarily in terms of the emphasis each placeson the role of system and text, form and meaning, structure and discourse, andthe particular modes of analysis these differences engender (Halliday, 1985). Theterm ‘structuralism’ as it is applied in this paper is not specific to a particularlinguistic school, or reducible to structural linguistics, but pertains to a broaderorientation in social theory. From this perspective, system functional theory, andin particular its application to the global analysis of textual form, as evident inMartin’s theory of genre (Martin, 1986a, 1992), falls within the paradigm ofstructuralism as outlined. While Halliday (1985: xxvii) distances himself fromstructural linguistics to articulate a systemic functional grammar which focuseson language as a resource for meaning, he nevertheless demonstrates an implicittendency to collapse meaning back into form, or to see a direct correlationbetween the two. More importantly for the purposes of this paper, when systemicfunctional theory has been applied in the field of language and literacy pedagogythis slippage is most clear. In Martin’s theory of genre — the most sophisticatedattempt to apply systemic functional theory to literacy education — ‘text’ isredefined as text type and the theoretical emphasis on language as resource formeaning becomes translated in practice into the mastery of dominant textualforms and their attendant rules. This paper demonstrates how this process takesplace within the classroom.

The primary function of systemic functional linguistics is textual analysis.What is interesting within education is its transformation into a pedagogy. Thereis an assumption that teaching the ability to analyse text directly translates intostudents acquiring the ability to produce it. However, the orientation is quitedissimilar. Bourdieu (1990: 31) identifies this in his comment that ‘¼ thegrammarian has nothing to do with language except to study it in order to codifyit. By the very treatment he applies to it taking it as an object of analysis insteadof using it to think and speak, he constitutes it as a logos opposed to praxis’.Recently Corson (1997: 168) has made a similar point in relation to the generalarea of applied linguistics when he considers there is a need for ‘workers inapplied linguistics [to] become a little clearer in theorising the point ofintersection between it and the real world of human social interaction’.

Moreover, the structuralist concern with analysing the patterns and stabilitiesof language — a legitimate task in itself — translates into a teaching practice

Policing the Text 119D

ownl

oade

d by

[U

nive

rsity

of

Wes

tern

Syd

ney

War

d] a

t 18:

19 1

4 A

ugus

t 201

1

which fetishes dominant textual forms. By its very nature, then, a structuralistapproach to literacy pedagogy tends towards the reproduction of these forms,rather than enabling a creative — indeed subversive — manipulation of languageresources. As teachers implement the approaches to writing based on systemicfunctional theory mandated in Australian syllabus documents this incongruentrelationship between ‘logos’ and ‘praxis’ is permeating their pedagogic practice.By examining an example of the implementation of the 1994 New South WalesK-6 English Syllabus, this paper will demonstrate how structuralist methodologyin relation to textual analysis has been reborn as a language and literacypedagogy in Australian schools.

Background to the SyllabusThroughout the 1990s many state education systems have adopted approaches

to teaching language based upon systemic functional theory. They draw uponHalliday’s functional grammar (Halliday, 1985) and Martin’s theory of genre(Martin, 1986a, 1992) and are generally referred to as functional approaches. Thismove has resulted in a more explicit teaching of textual form than existed duringthe 1970s and 1980s; a period dominated by progressivist teaching ideals whichfavoured more naturalistic, psychologically-based approaches to teaching lan-guage. Such a radical shift in language theory and pedagogic practice, however,was bound to create shockwaves. This was particularly the case in New SouthWales (NSW). Within a couple of months of the release of the State’s K-6 EnglishSyllabus in late 1994, a document based on a functional approach to grammarand text, negative teacher reaction was enough to prompt a new government toplace the syllabus under review. Due to the withdrawal of grammar fromlanguage curriculum in the early 1970s (NSW Department of Education, 1974),it seemed inevitable that the reintroduction of grammar would meet someresistance. Functional grammar, however, created a furore. It was viewed as fartoo technical; an academic grammar with little pedagogic application (NSWDepartment of Training and Education Coordination, 1995: 47). In contrast, theSyllabus’ approach to text based on Martin’s notion of genre, appeared to be wellreceived by teachers (NSW Board of Studies, 1996). As in the earlier NSWMetropolitan East Disadvantaged School Program (DSP) publications (Cal-laghan & Rothery, 1988; Knapp, 1989a, b), influenced by the work of Martin andRothery (1980, 1981), the Syllabus adopted a schematic, product-based view oftext, whereby what were considered the key text types in the primary years ofschooling were identified with their social purpose, structural and grammaticalfeatures itemised for teachers (NSW Board of Studies, 1994: 101–52). There is alsomention in the document of text forms which have taxonomic links to the ninetext types, yet these are merely cited, the links implicit and no generic descriptionof each is provided. Emphasis is clearly on the nine text types, these being:narrative, drama, poetry (classified as literary texts), and discussion, explanation,exposition, information report, procedure and recount (classified as factual texts).This is a rather clumsy division in itself; a point recognised even in the Syllabusbut persisted with anyway. Here and elsewhere throughout the document themessiness which is the reality of language use receives token mention but is

120 Language and EducationD

ownl

oade

d by

[U

nive

rsity

of

Wes

tern

Syd

ney

War

d] a

t 18:

19 1

4 A

ugus

t 201

1

overwhelmingly downplayed for the structuralist precision of neat taxonomies(see Figure 1).

Categories of Texts

Literary Texts Factual Texts

(including media texts) (including media texts)

Text Types

Literary Texts Factual Texts

(including media texts) (including media texts)

Narrative Discussion

Drama Explanation

Poetry Exposition

Information Report

Procedure

Recount

Text Forms

Literary Texts Factual Texts

(including media texts) (induding media texts)

Aboriginal Dreaming Stories Advertisements

Ballads Announcements

Cautionary Tales Conversations

Fables and Parables Current Affairs Programs

FairyTales Debates

Fantasy Directions

Folk Tales Documentaries

Historical Narrative Editorials

Improvisations Essays

Legends Instructions

Limericks Instruction Manuals

Lyrics Interviews

Mimes Lectures/Presentations

Myths Letters

Odes Newspaper Articles

Playscripts Public Speaking

Radio Drama Recipes

Science Fiction Reference Articles

Sonnets School Reports

Figure 1 NSW Board of Studies 1994: 101–2

Policing the Text 121

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f W

este

rn S

ydne

y W

ard]

at 1

8:19

14

Aug

ust 2

011

This scientific approach to text, however, appealed to teachers. It provided alanguage to talk about textual form but, unlike functional grammar, itstechnicality was limited. It was relatively easy to grasp and proved effective inthe classroom. The structural features of the text types provided a scaffold forstudents’ writing, a much needed development in literacy pedagogy which,during the 1970s and 1980s, had offered teachers few tools to assist students withtheir writing. Yet while there is some benefit in this structuralist inspiredapproach, the fact that functional grammar has been rejected by many teachers(NSW Department of Training and Education Coordination, 1995: 47) suggeststhat the necessary link between the structural labels and grammar has beenbroken. Instead of learning about the relationship between grammar and textualform, the approach has been reduced to learning the structural characteristics ofa set number of text types. With the grammatical foundations removed thepedagogic effectiveness of this simplified structuralism is highly questionable.

But it is not only this schism between structure and grammar, evident in muchof the application of this approach, which is problematic; there are inherenttheoretical problems in the notion of text on which it is based. Its drawcard is theconcrete nature of the approach. Writing is considered a craft, moving literacyand language pedagogy away from a purely inspirational individualism,characteristic of progressivist approaches (Gilbert, 1990), to one grounded in thesocial constructedness of language. Its theorising of the social, however, bearsthe hallmark of structuralism; namely it is conceptualised as an objectifiedphenomenon whose lifeforce has been sapped. None of the dynamism of socialreality is accounted for within this theoretical perspective and so textualformulations of the social are similarly constrained. This is clearly evident whenthe focus is on text as type. Generic schemas are presented as sets of rules andvariation beyond these normative structures are rarely, if ever, considered withinthe classroom context. Of course there is a need to identify textual patterns forthe purposes of study, however, the dilemma of structuralism is the degree towhich structure and system are privileged over agency and use. To emphasiseagency and use is not to reassert some romantic individualism, but to recognisethat, since media, form, context, content and intent are all volatile elements inlanguage practices, the ability to self-reflexively manipulate language — at thelevel of grammar and text — is a necessary part of equipping students at thishistorical moment. There is a fine line between regularity and rule. Structuralismemphasises the latter and in so doing leaves little room for the textual practice ofstudents to move outside the confines of restrictive formulae.

It was this prescriptive tendency of a functional approach based on a productnotion of text which was one of the key concerns of a study of the teaching ofgrammar and text in NSW primary schools in 1995/1996 (Watkins, 1996). Thestudy focused on four teachers differing in age, experience and educationalphilosophy, in three quite different schools with four different classes spanningthe Years 2 to 5. Despite this diversity in the sample there was an amazingsimilarity in the teachers’ approaches to text which is discussed in the largerstudy. This paper provides an account of one of these teachers who exemplifiesthe approach to text demonstrated in the study overall. Each of the teachers choseto examine a range of text types identified in the NSW Syllabus in the units of

122 Language and EducationD

ownl

oade

d by

[U

nive

rsity

of

Wes

tern

Syd

ney

War

d] a

t 18:

19 1

4 A

ugus

t 201

1

work they were teaching at the time, as did the teacher discussed in this paper.However, the textual form of particular concern here is narrative. While a simplenarrative has distinctive structural features, itemised in the NSW Syllabus as:orientation, complication, sequence of events, resolution and then comment orcoda (NSW Board of Studies, 1994: 105), it does in fact possess the potentiality tobe quite an open and fluid form. For this reason it is interesting to see how it fareswithin a functional approach as interpreted by this particular teacher.

Background to the StudyThe teacher in question, referred to as Liz, had been teaching for eight years

at the time the study commenced. She had worked at this particular school forsix and a half years. During this time she had mainly taught junior primary classesof students aged between eight to ten years. Liz was an executive teacher at theschool and with the release of the new English Syllabus was given theresponsibility for coordinating the rewriting of the school’s English policy. Shealso coordinated staff professional development in the implementation of thenew curriculum.

Liz’s school is located in an outer western suburb of Sydney. The studentpopulation is 482 of which 18% are from a Non-English Speaking Background(NESB). The majority of students are from low socioeconomic status (SES)families and so the school has had a DSP classification for a number of years. Themajority of the staff has less than five years’ teaching experience; Liz is one of themost experienced staff members. There is quite a turnover of staff and highabsenteeism among staff and students. At the time of the study Liz was teachinga Year 3/4 composite class which had two NESB students. Despite difficulties atthe school Liz worked tirelessly to implement the new curriculum. The problemsevident in her classroom practice are symptomatic of the syllabus she isimplementing rather than a result of her own capabilities as a teacher.

To investigate the teacher’s practice two lessons were observed: one at thecommencement of a unit of work and the other towards its end. A detailedinterview with Liz regarding her teaching practice and overall educationalphilosophy was also conducted following the observation lessons. Both thelessons and interview were audiotaped. While it is the classroom discourse whichis of concern to this paper, it is important to summarise the teacher’s responsesto questions around grammar and text to provide some background to herpractice. In the interview Liz explained what she understood the term text tomean. She referred to text as being ‘spoken or written’ but it was always discussedin terms of type, such as procedures and narratives. When questioned abouttextual variation, she remarked, ‘there’s a lot of overlap, one piece of text mayshow elements of two’, but she was not clear about how to identify thesedifferences. Her criteria for determining a label for a text was largely based on atext’s content rather than linguistic factors; for example, she referred to a reportas ‘anything non-fiction and a narrative is fiction’. It was not apparent to Liz thatreports and narratives could be either fiction or non-fiction, and that thelanguage, which could be used in texts, assigned these labels varied. Texts withlabels such as report and narrative were viewed simply in terms identical to thegeneric schemas outlined in the Syllabus. However, she did not fully understand

Policing the Text 123D

ownl

oade

d by

[U

nive

rsity

of

Wes

tern

Syd

ney

War

d] a

t 18:

19 1

4 A

ugus

t 201

1

the grammatical patterning of texts or how the structural labels assigned togeneric stages were determined. From questioning during the interview, itappeared Liz was unable to differentiate between texts which had beeninappropriately assigned the same label by textbook publishers but weregrammatically quite different. She also explained how she had difficulty withfunctional grammar, despite attending departmental inservicing, and so avoidedusing functional grammatical terms with her class and opted instead fortraditional terminology. It was clear, however, that her understanding oftraditional grammar was limited to the parts of speech. In terms of hereducational philosophy Liz believed she used a ‘child-centred approach’ whichshe interpreted as providing ‘good demonstrations, but giving them skills to findout themselves’. She aimed ‘to cater for the individual needs of her students’ andhoped ‘kids enjoy their work’. Her comments demonstrated an affinity withprogressivist ideals yet her practice proved a mix of progressivist and traditionalteaching methodologies, the latter in response to classroom managementdemands and a by-product of the structuralist approach to text she was utilising.

At the time the research was conducted, Liz and her class were in the thirdweek of a unit entitled ‘Our Exciting Environment’ which had been co-writtenwith a group of other teachers at the school. It was an integrated unit, which drewupon outcomes from the English, Science and Technology, and Creative Arts KeyLearning Areas (KLAs). Despite the factual slant to the unit a range of types oftexts were read and/or written by students, such as reports, recounts, explana-tions, procedures, fictional narratives and poems. The term ‘integrated’ seemedto suggest a ‘mish-mash’ of related topics with the theme the only unifying factor.The treatment of grammar and text was unrelated to any disciplinary knowledge.A focus was not given to a particular text or related texts and no grammar wasreferred to in the pre-programmed unit. The text and treatment of language ingeneral, appeared essentially a vehicle for examining the theme-related content.The unit did not make connections between language and disciplinary know-ledge and so there tended to be either an incongruence between the languageused to process subject matter or an uneasy juxtaposition within the unit betweencontent and linguistic forms, each of which is evident in the practice observed inLiz’s lessons.

AnalysisThis is the first segment of the second observation lesson, which is treated in

detail in this paper. An account of the remaining work on Liz’s class is providedin the larger study (Watkins, 1996). At the time of the second observation lessonLiz was into the fifth week of her work on ‘Our Exciting Environment’. In thefirst lesson she had used a poem about bugs as stimulus for a grammar, spellingand punctuation editing activity and had also completed a text reconstructionexercise using an information report before asking the class to write their own.In this lesson the focus was on narrative. The class was examining the popularpicture book, Lester and Clyde, which is a useful text for introducing a unit on theenvironment; but the reasons for using a literary/fictional text in a generallyfactual domain, particularly at this stage of the unit, were not explored by Liz.The book was used with the class because it had a theme relevant to the unit of

124 Language and EducationD

ownl

oade

d by

[U

nive

rsity

of

Wes

tern

Syd

ney

War

d] a

t 18:

19 1

4 A

ugus

t 201

1

work the class was studying, but it was not contextualised from either a linguisticor disciplinary perspective. To commence the lesson Liz discussed the text withher class. While the story was familiar to her students, it is only later in the lessonthat she reads the text to the class. The initial discussion does not deal with thisspecific text but with narrative as a reified type. She starts by asking the class toclassify the text as either fiction or non-fiction.

1 T: We have been looking at the environment and this is a story about a¼ the environment. Who knows ¼ heard this story before?(Students raise hands)Who can tell me what sort of text is it? Is it a fiction or is it a non-fiction?Who thinks it’s non-fiction?(No students raise their hands)Who thinks it’s fiction?(Students raise hands)Why is it fiction? ¼ Craig?

2 C: Cos the frogs are alive.3 T: Aren’t all frogs alive?4 Ss: Yeah, yes.5 S: They talk.6 T: They talk, yes. Yeah ¼ OK7 S: It’s not a true story.8 T: It’s not a true story, yeah, so it’s fiction.

After determining that the text is fiction Liz then seeks a further classificationin terms of text type.9 T: If you think we can write narrative and we can write poems and we

can write a report and a procedure, which one is this? We know it’sfiction rather than non-fiction but what type of text is it? It can be eitherfiction or non-fiction, now we’ve decided it’s fiction. Now is it a report,is it a procedure, is it a poem, is it a song, is it a play, is it a narrative?What sort is it? Some people think they know but they’re not 100%sure. Why don’t you just put up your hand and just have a good guess.(Inaudible) OK then, hands down. OK who thinks it’s a song? ¼ Whothinks it’s a play? ¼ Who thinks it’s a procedure? ¼ Who thinks it’sa narrative? Yes, it’s a narrative.

Liz’s comments reflect an approach which is really about asking ‘which pigeonhole does this text fit into?’. The classification is not based on what is happeningin this particular text either linguistically or visually, it is based on a knowledgeof a predetermined type. The rigidity of her notion of textual form is also evidentin her explanation of the structural features of a narrative.

10 T: So what are the parts of a narrative? Who can remember the parts ofa narrative? There’s three parts — the beginning, the middle and theend — but we don’t call them that.

11 S: An introduction.12 T: An introduction. Yes and then there’s a ¼13 S: A body.

Policing the Text 125D

ownl

oade

d by

[U

nive

rsity

of

Wes

tern

Syd

ney

War

d] a

t 18:

19 1

4 A

ugus

t 201

1

14 T: A body, yes and then there’s a ¼15 S: A ¼ um ¼ conclusion.

Liz explains that narrative texts have three parts. This is narrative per se notsimply the story Lester and Clyde which had not been read to the class at this stage.Initially, she makes use of the labels of introduction, body and conclusion. In lines16–46, however, the content of these stages is discussed in greater detail with thebody and conclusion renamed as plot and resolution.

16 T: Yep. OK Narratives have something special. They have a certain,starts with ‘c’¼ ch¼ They have to have?

17 S: (inaudible)18 T: No, these are the things that are in a narrative. They have to have

what?¼ When we did the Haunted House a few weeks ago we chosetwo what?

19 S: OHH, ohh (inaudible)20 T: Yes, but then what were they?21 S: Characters.22 T: Characters. Yes. OK, so we have to have characters. OK what else does

a narrative have to have? It has to be? ¼23 S: A story?24 T: Yes, we know it’s got to be a story. It’s gotta have characters. It’s also

gotta have as ¼25 S: Setting.26 T: Setting. Good Girl. What’s a setting?27 S: Where it’s set.28 T: Yes, where it’s set or ¼29 S: Or where it takes place?30 T: Thank-you Scott. It’s so nice to see your hand up. OK, so it’s gotta have

characters, it’s gotta have a setting and what else has to happen in it?Put your hand up, Brett. Yep.

31 S: Something’s gotta happen.32 T: OK. Something’s gotta happen. OK, so what do we call that?33 S: Plot34 T: Plot. Good Boy. OK, so it’s called the plot. So we ¼ in the introduction

we have a setting and we introduce the character, then in the bodysomething happens and then in the conclusion what happens towardsthe end, it has to ¼

35 S: It has to end.36 T: It has to end but what happens to the plot? Sort of something happens

and then it has to ¼37 S: They tell you like, how it stops.38 T: Not in the end they don’t, how it stops, or that would be sort of a ¼,

not like a comment, but ¼39 S: An end.40 T: An end, yeah with, um ¼ Fairy tales, how do they usually end?41 S: Um, they lived happily ever after.

126 Language and EducationD

ownl

oade

d by

[U

nive

rsity

of

Wes

tern

Syd

ney

War

d] a

t 18:

19 1

4 A

ugus

t 201

1

42 T: And they lived happily ever after. OK, so that could be like a ¼ It’s abig long word, a reso ¼

43 Ss: Revolution.44 T: No.45 Ss: Resolution.46 T: Resolution. Yes. The resolution is that the plot, something happens

and the resolution is it gets concluded or it gets finished or it getsworked out. OK. At the end of this story we’re going to be looking atwho are the characters, what was the plot, what was the setting. OK.

While Liz does not make use of the structural terms, ‘orientation’ and‘complication’, or the optional elements of ‘comment’ or ‘coda’, as annotated inthe NSW Syllabus, her explanation to the class demonstrates how she hasinterpreted the functional approach to teaching text as outlined in the document.To Liz text clearly occurs as type, identifiable by a set formula of stages; anequation to be learnt and applied. The relatively closed questioning, simplyseeking standard responses, is equally suggestive of a formulaic understandingof text. It seems ironic that the strategy Liz uses here, that is the identification ofstructural stages of a text, is referred to in curriculum material based on theSyllabus as ‘deconstruction’. In this structuralist treatment of text Derrida’s term(1976), denoting the pushing of textual meaning to its limits, has beenreconfigured as the imposition of textual boundaries. What is interesting is howLiz’s adoption of this approach to text has shaped her pedagogy. Far from theopen progressivist methodology with which she identifies, Liz, instead, isdemonstrating a didacticism limiting rather than promoting student under-standing. While this shows the influence of ‘logos’ on ‘praxis’ it also reveals theinherent problems of mistaking one for the other.

Following this discussion Liz finally reads the story to the class. Lester and Clydedoes conform to the narrative structure she outlines, yet, it also does a lot morethan what Liz, and the Syllabus for that matter, indicate about this textual form(NSW Board Of Studies, 1994: 104–9). In discussing the problems of linguisticclassification, Halliday (1985: xxxiii) writes ‘There is a general principle inlanguage, that the easier a thing is to recognise, the more trivial it is likely to be;the outward sign of a semantically significant category is usually not simple orclearcut, and many factors may have to be taken into account in identifying it’.While Halliday is referring to classification at a grammatical level, this commentalso has particular poignancy for the application of generic structural categoriesas utilised by many functional approaches to language; that is, there is thepotential to obscure other factors which may be valuable for the interpretationand production of text and to instead simply focus on what is merely trivial.

This is certainly the case with Liz’s examination of Lester and Clyde. In additionto possessing the structural features characteristic of many simple narratives italso makes use of the rhythms and rhymes of poetry, which are evident in itsopening lines:

Far away from the cityin green countryside,live two fat, green frogs

Policing the Text 127D

ownl

oade

d by

[U

nive

rsity

of

Wes

tern

Syd

ney

War

d] a

t 18:

19 1

4 A

ugus

t 201

1

known as Lester and Clyde.Their home is a pondthat is sparkling and bright,surrounded by flowers-oh a beautiful sight!

(Reece, 1976: 2)

Lester and Clyde would have been a useful text to exemplify play with textualform and the use of poetic devices in narrative, but by using a model with a focuson type and a schematic notion of text such insights did not occur to Liz. It isexamined instead from the narrow, or trivial, perspective of narrative asintroduction, plot and resolution. While these structural categories can have auseful heuristic value in the analysis of narrative texts, the way they are treatedhere establishes them as rules rather than tools. Reid (1992) challenges thisflattening of narrative into a mandatory linear sequence as found in Martin andRothery (1980, 1981) and borrowed by the NSW Syllabus. Following Labov, Reidpoints out that the so-called stages of orientation, complication and resolution canoccur in different orders or may not even exist as distinct sections. Given thatstudents are well acquainted with narrative as a text type by this stage of theirschooling, having discussed it from kindergarten, texts such as Lester and Clydecould form the basis for discussion of textual variation rather than being used tosimply exemplify a predetermined model.

This approach to text is also prohibitive in the sense that a focus on thesestructural features can mask other organisational principles governing a text,such as theme. This is evident at the end of this segment of the lesson where Lizdiscusses the resolution of the story with the class.

47 T: ¼ so the resolution to the problem OK was what? What was theresolution. What happened at the end of the story? The resolution wasthey ¼

48 S: Um ¼ Lester came back to Clyde.49 T: So, Lester came back to Clyde. OK, so the plot was that Lester was

playing tricks so they decided they couldn’t live together any more,so Lester went away. Lester found a polluted pond which he didn’tlike very much so he thought ‘I don’t like this, I’ll have to go back and¼’ Has the problem been solved? Is Lester still going to play tricks?

50 Ss: No.51 T: No. OK, so the playing tricks part is important because he then at the

end says ‘he’s not going to play tricks on you anymore because I likethis pond and this is where I want to stay’.

52 S: Yeah, and then at the end the man comes (inaudible).53 T: Well, that doesn’t happen in our story. OK, so don’t write more into

it.54 S: But Miss then the tractor comes and ¼55 T: Yeah, but you don’t know that ¼

In line 52 a student clearly challenges Liz’s interpretation of the text’sresolution. The student points out, ‘Yeah, and then at the end the man comes’.

128 Language and EducationD

ownl

oade

d by

[U

nive

rsity

of

Wes

tern

Syd

ney

War

d] a

t 18:

19 1

4 A

ugus

t 201

1

Liz, feeling she has already discussed the resolution, is quick to correct thestudent by saying, ‘Well, that doesn’t happen in our story, OK, so don’t writemore into it’. Another student, however, agrees with this student’s comment andprotests with, ‘But Miss then the tractor comes and ¼’. Liz’s response is ‘Yeah,but you don’t know that’. What the two students are referring to is the last doublepage of the story.

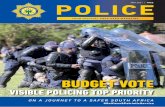

Figure 2 shows the two frogs sitting in their pond making the comment ‘Untilman comes along ¼’ with a bulldozer in the background. It is obvious what thestudents are suggesting. There is clearly not a nice neat resolution to the story asLiz presents. The end is open. There is not the sense of closure as presented inthe schema she adopts from the Syllabus. The two students pick up on this pointand demonstrate a far more sophisticated reading of the text than their teacher.They have moved beyond a view of narrative as simply orientation, complicationand resolution, they’ve actually made the connection between the theme of theunit — the environment — and one of the themes of Lester and Clyde — caring forthe environment. Lester and Clyde is a story about two frogs who have adisagreement etc., etc., as Liz says, but that is all it is if narrative is simply viewedas orientation, complication, resolution. Theme is a crucial organising element ofnarrative, which in this case would link the narrative to the unit topic. Incritiquing structuralist approaches to narrative Chambers (1984: 8) argues that‘meaningfulness is not exhausted (and indeed it may be completely missed) by

Figure 2 From Reece, 1976 (author and illustrator)

Policing the Text 129D

ownl

oade

d by

[U

nive

rsity

of

Wes

tern

Syd

ney

War

d] a

t 18:

19 1

4 A

ugus

t 201

1

analysis of narratives in terms of their supposed internal relationships alone’.This stranglehold on meaning is also evident, in that, to Liz, signification is thesole preserve of the written elements of the text. The visuals, which are sopowerful and often provide the springboard for the open-endedness of narrativeare ignored. She only allows a singular reading of the story, which matches thestructural constraints that have already been determined and which she ‘polices’vigorously. The restrictive parameters placed on textual meaning are alsoindicative of the constraints placed upon her pedagogic practice.

ConclusionThe point of the preceding analysis is not to highlight problems with Liz’s

teaching, she is simply implementing the approach to text as outlined in the NSWSyllabus as she sees it. This type of rigid application is not unique. The otherteachers in the larger study, teaching in very different schools, used a similarapproach to teaching text as displayed by Liz, which was equally restrictive.While these examples are drawn from a small study, and do not suggest a practicegeneralisable across the entire teaching population, the results do at least raisequestions about the structuralist approach to text, which dominates literacy andlanguage curriculum across Australia. It is possible to examine textual structurein a less restrictive manner but to do so the notion of text on which this model isbased needs to be rethought. In most mainstream curriculum material text isviewed as type, as a homogeneous, unproblematic phenomenon. Teaching it assuch curtails understanding and, as demonstrated here, tends towards a didacticpedagogy. Such tendencies were foreseen by Kress (1993: 35) when he voiced theconcern that ‘The Martin/Rothery account necessarily tends towards a firmerview of generic structure, a greater tendency towards reification of types, and anemphasis on the linguistic system as an inventory of types. With such a tendencygoes the corresponding tendency pedagogically towards an emphasis on thematter of form, and a tendency towards authoritarian modes of transmission’.

Kress and other theorists such as Threadgold (1988) and Freadman (1994)emphasise the fluidity of text. They recognise the shortcomings of structuralistapproaches, especially their pedagogic limitations, and have drawn uponpost-structuralist theory in their own work, which can account for the heteroge-neity which is the reality of textual form. It is time those responsible formainstream language and literacy curricula acted similarly and kept abreast ofcurrent theory: not in a faddish sense discarding the benefits of structuralism butto ensure curricula appropriately reflects the diversity of textual form rather thanoperating as a theoretical straitjacket which inhibits practice. At present,however, this uncritical application of approaches to text based upon systemicfunctional theory in Australian classrooms results in the killing of textual formin order to examine, more conveniently, its structural features. In many states ofAustralia it has attained the position of an orthodoxy in determining languageand literacy curricula. To challenge structuralism’s stranglehold it is useful,therefore to keep Halliday’s own words in mind: ‘It is unlikely that any oneaccount of a language will be appropriate for all purposes. A theory is a meansof action, and there are many very different kinds of action one may want to takeinvolving language’ (Halliday, 1985: xxix).

130 Language and EducationD

ownl

oade

d by

[U

nive

rsity

of

Wes

tern

Syd

ney

War

d] a

t 18:

19 1

4 A

ugus

t 201

1

CorrespondenceAny correspondence should be directed to Dr Megan Watkins, School of

Teaching and Educational Studies, University of Western Sydney-Nepean, NSW2747, Australia ([email protected]).

Notes1. Structuralist approaches to text characterised by a text type model have been adopted

in all state English syllabus documents in Australia. It is also evident in the 1998National Literacy Benchmarks for Years 3 and 5 which state education systems arerequired to report on in return for federal funding. These approaches to text vary,particularly in relation to the form of grammar that underpins them. WhileQueensland places emphasis on functional grammar the remaining states usetraditional grammar in various forms and to varying degrees.

2. Within systemic functional linguistics there are quite different theoretical perspectiveson the relationship between text and context as evident in Halliday’s register theory(1978) and Martin’s theory of genre (1992). It is the latter, however, with the moredeterminist notion of context/text relations, that has been overwhelmingly adoptedin the field of language and literacy education.

ReferencesBourdieu, P. (1990) The Logic of Practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.Callaghan, M. and Rothery, J. (1988) Teaching factual writing — A genre-based approach

— language and social power. Report of the DSP Literacy Project. Erskineville:Metropolitan East DSP.

Chambers, R. (1984) Story and Situation-Narrative Seduction and the Power of Fiction.Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Corson, D. (1997) Critical realism: An emancipatory philosophy for applied linguistics?Applied Linguistics 18 (2).

Derrida, J. (1976) Of Grammatology. G.C. Spivak (trans.). Baltimore: John HopkinsUniversity Press.

Eagleton, T. (1983) Literary Theory — An Introduction. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.Freadman, A. (1994) Models of genre for language teaching. Sonia Marks Memorial

Lecture. Sydney University, 13 October.Gilbert, P. (1990) Authorizing disadvantage: Authorship and creativity in the language

classroom. In F. Christie (ed.) Literacy for a Changing World. Hawthorn, Victoria: ACER.Halliday, M.A.K. (1978) Language as Social Semiotic: The Social Interpretation of Language and

Meaning. London: Edward Arnold.Halliday, M.A.K. (1985) An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Edward Arnold.Knapp, P. (1989a) The Report Genre. Erskineville: Metropolitan East Disadvantaged

Schools Program.Knapp, P. (1989b) The Discussion Genre. Erskineville: Metropolitan East Disadvantaged

Schools Program.Kress, G.R. (1993) Genre as social process. In B. Cope and M. Kalantzis (eds) The Powers

of Literacy — A Genre Approach to Teaching Writing. London: The Falmer Press.Kress, G.R. and Threadgold, T. (1988) Towards a social theory of genre. Southern Review

21 (3), 215–43.Martin, J.R. (1986a) Systemic functional linguistics and an understanding of written text.

Writing Project — Report 1986, Working Papers in Linguistics 4. Department of Linguistics,University of Sydney.

Martin, J.R. (1986b) Intervening in the process of writing development. Writing to Mean:Teaching Genres Across the Curriculum. Occasional Papers Number 9. Sydney: AppliedLinguistics Association of Australia.

Martin, J.R. (1992) English Text — System and Structure. Philadelphia: John Benjamin.Martin, J.R. and Rothery, J. (1980, 1981) Writing Project Report. Nos 1 & 2. Sydney:

Department of Linguistics, University of Sydney.

Policing the Text 131D

ownl

oade

d by

[U

nive

rsity

of

Wes

tern

Syd

ney

War

d] a

t 18:

19 1

4 A

ugus

t 201

1

Milner, A. (1991) Contemporary Cultural Theory — An Introduction. St Leonards, Australia:Allen and Unwin.

NSW Board of Studies (1996) English K-6 Review Report Part A. North Sydney: NSW Boardof Studies.

NSW Board of Studies (1994) English K-6 Syllabus and Support Document. North Sydney:NSW Board of Studies.

NSW Department of Education (1974) Curriculum for Primary Schools — Language. Sydney:NSW Department of Education.

NSW Department of Training and Education Coordination (1995) Focusing on Learning:Report of the Review of Outcomes and Profiles in New South Wales Schools. Sydney: NSWDepartment of Training and Education Coordination.

Reece, J.H. (1976) Lester and Clyde. Sydney: Ashton Scholastic.Reid, I. (1992) Narrative Exchanges. London: Routledge.Threadgold, T. (1988) The genre debate. Southern Review 21 (3), 315–30.Watkins, M. (1996) Grappling with grammar: A study of grammar, text and pedagogy in

primary school classrooms. Unpublished dissertation, Macquarie University.

132 Language and EducationD

ownl

oade

d by

[U

nive

rsity

of

Wes

tern

Syd

ney

War

d] a

t 18:

19 1

4 A

ugus

t 201

1