Plant Food in the Late Natufian: The Oblong Conic Mortar as a Case Study

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Plant Food in the Late Natufian: The Oblong Conic Mortar as a Case Study

PLANT FOOD IN THE LATE NATUFIAN 133

Plant Food in the Late Natufian:The Oblong Conical Mortar as a Case Study

DAVID EITAM1

1 Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem 91905, Israel

INTRODUCTION

This paper focuses on a Late Epipalaeolithic rock-cut installation, the oblong conical mortar,

better known when breached as a “stone pipe” (Fig. 2: 1) and examines the ways in which it

relates to subsistence strategies during the Natufian. Preliminary reports of a detailed survey

of the final Natufian site of Hruk Musa in the lower Jordan Valley and the late Natufian site of

Rosh Zin in the Negev highlands are presented as specific examples in order to evaluate the

probable role of wild barley in the Natufian diet and other implications of changes in Natufian

subsistence strategies.

The problem of the study of rock-cut installations, deriving from long neglect (as compared

to many related studies of groundstone tools), is the lack of a comprehensive and agreed-upon

methodology, as well as discontinuity and disunity of research (Wright 1991, 1992). This

study of the oblong conical mortar is part of ongoing research work on Late Epipalaeolithic

rock-cut installations in the southern Levant, which is based and founded upon observations

of about a thousand rock-cut installations, a hundred ground stone tools and thousands of

installations from prehistoric and historic periods. An easy-to-use classification system for

prehistoric and historic rock-cut installations and ground stone tools, suitable for analyzing

large amounts of data, is proposed in order to deal with these problems (see Fig. 1, Tabs. 1,

2, and Appendix A). The basic assumption of our work is that ground stone tools, probably

since the end of the Epipalaeolithic, were pre-planned and designed devices that served as a

means of processing, producing, preparing and storing subsistence resources – whether food,

water, or other materials. The use of these devices in ceremonial/cultic, hierarchic or gender

Journal of The Israel Prehistoric Society 38 (2008), 133-151

133

DAVID EITAM134

Figure 1. Legend with design Sign, usewear and natural phenomena of rock-cut installations and ground

stone tools; Hruk Musa: 1. Cylindrical bipolar pestle/ handstone (Tab. 1: 37); 2. Pestle/ handstone /anvil

/grooved stone (Tab. 1: 54); 3. Wide conical mortar with stones at bottom (Tab. 1: 62); 4. Large quern

with small cupmark (Tab. 1: 32).

PLANT FOOD IN THE LATE NATUFIAN 135

Figure 2: 1. Nahal Oren, oblong conical mortar cut in boulder, pierced at bottom – “pipe stone” (The

Israel Museum); Hruk Musa: 2. Oblong conical mortar with shaft at bottom (Tab. 1: 5); 3: Oblong

conical mortar with pierced or eroded bottom (Tab. 1: 12); 4. Oblong conical mortar with funnel rim

(Tab. 1:14); 5. Oblong conical mortar with shaft at bottom, eroded by Karstic activity.

DAVID EITAM136

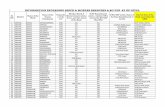

Table 1: selection of rock-cut installations and ground stone tools from Huzuk Musa.

No Type,

subtype

Upper/

lower

diameter/

depth *

Shape Face Location Preservation Note

5 Oblong

conical

mortar

26.5-(30)/

3/60

Funnel rim;

wide M;

pointed shaft

at bottom

Pec &

course Gr

of Breccia

rock; on

low M &

shaft: fine

Gr

Com I; on

wide rock

surface;

beside no. 68

Curved line

cut on N edges

of rock face

Similar

curved line

surrounded

no. 68

12 Oblong

conical

mortar

21/10(5)/

/33(39)

surrounded

by cut edge

60 L; funnel

rim; wide M

M sides Pec

& Gr till

end

Com IV; on

top of rock;

in Str Q

Shaft & end;

missing

– pierced

Crumbling

rock;

eroded end

14 Oblong

conical

mortar

24-25/7/49 Funnel rim;

M cylindrical:

9/5/24; round

end

Pec

& course

Gr on rim

& upper M;

fine Gr on

sides & end

Com IV;

on top of

a boulder;

beside no. 74

Rim and upper

M eroded

High

& narrow

boulder

31 Small

cupmark

10/8/2 Shallow Sl

concave

Smooth:

fine Gr

Com III;

beside no. 24

Good

33 Oblong

conical

mortar

19-20/5/43 Funnel rim:

14 L; M: 12/

8/15; shaft:

8/2/11

Rim: Pec

& Gr; M &

shaft: fine

Gr & Pol

Com IV; on

small rock

surface

Good

60 Threshing

floor?

2800X1800 Semi half

circle rock

surface

Nature

flat rock

surface

Com VI; on

top of the S

cliff; Inst 69

cut in it

Good Debatable;

view to N,

E & S

61 Small

threshing

floor?

500X400 Oblong & flat

rock surface

bordered

on the N by

crack

Nature

flat rock

surface

Com VI;

within large

surface: Inst

60; Inst 59 is

cut in the E

Good

62 Wide

& oblong

conical

mortar

33/10/41 Sharp funnel

rim: 22 L; M:

20/12 /15;

broken step;

end: hard

stones - Car,

Fl, Pec & Gr

Edge: Pec &

Gr; lower

rim: course

Gr; M: fine

Gr; hard

stone: Pol

by use

Com VI; N to

Inst 63

Erosion: holes,

cracks & Exo-

karst

stages –

step pierce

by use

63 Threshing

floor

250X250 Irregular

square rock

surface

Flat natural

rock

surface

Com VI;

lower rock

shelf

Part eroded On edge of

S cliff

PLANT FOOD IN THE LATE NATUFIAN 137

No Type,

subtype

Length/

width/

thickness *

Shape Face Longitudinal/

transverse

sections of

work face

Preservation Raw

material

32 Large quern 90x65x15 Cut in slab;

edges 6-10

wide, 3 height

Flat/flat

& small

cupmark,

both

smooth

Beside Str C Broken in half Limestone

37 Pestle/hand

stone/anvil/

grooved

stone

(4.2), (2.9),

2.1 (2.9)

Multipile

tool; conic;

bipolar;

second use as

anvil

F Gr on

polar

& body;

Fl around

1 polar; Bat

on anvil;

streria

Fl/

Sl Conc

Olmost

complete

Grey

feldspar

basalt

54 Bipolar

pestle

6.8 (7), (3.3),

(3.1)

Cylindrical Gr & steria;

F gr

Sl Conv/

Fl

Olmost

complete

Feldspar

basalt

Table 2: Selection of Rock-cut installations from Rosh Zin.

No Type,

subtype

Upper/

lower

diameter/

depth *

Shape Face Location Preservation Note

3 Oblong

conical

mortar

14-15/3-4

/37

Funnel rim;

1/3 narrow

at lower part:

diameter 6

Rim: Gr;

smooth in upper &

lower parts

Com I;

beside no.

30

Eroded rim;

end:

8 Oblong

conical

mortar

19/5.5/42 Funnel rim;

conic-round M

Rim: Pec & Gr;

side: F Gr till end

Com II; on

a rock with

Inst 16,10

2 cracks; at

bottom

Probably

sealed Inst &

finds

11 Oblong

conical

mortar

16-16.5

/4/31

Conic-round Smooth-F Gr on

rim and sides

Com III;

beside Inst

12; on small

rock surface

Eroded just

above bottom

Beside and

to the E of

monolith

12 Small

cupmark

10-10.5/?/2 Oval; shallow

Sl concave

Bottom:F Gr &

some Pec

Com III;

beside no.

11

Beside

monolith

15 Conical

cupmark

11/8 Designed by

hard stone on

one side

Gr on side; Pec

at bottom

Com II;

beside Inst 7

1 side open

- broken

16 RCI

stopped

by hard

stone

10-11.5/9

/19

Flaked rim of

OCM stopped

by hard stone

at 12 L (was

not in use)

Rim: Pec & Gr;

Gr; smooth sides

till bottom; hard

stone: Fl, Pec

& F Gr

Com II;

beside

mortar Inst

20;

Erosion on

rim& upper

part

F Gr

Ð abrading

around

Hard stone

DAVID EITAM138

contexts is a consequence of their primary vocation, to convert raw material into a substantial

commodity.1

THE OBLONG CONICAL MORTAR

This installation is a round mortar with a narrow, oblong, conical cross-section of + 20

degrees and a pointed base. The oblong conical mortar, with an average diameter of 20 cm

and maximum depth of 70 cm, is cut in bedrock and in boulders or designed as a stone vessel

(like some mortars in Hayonim Cave, Bar-Yosef and Goren 1973: Fig. 9). The 139 oblong

conical mortars that have been documented until now were divided into three types: oblong

conical mortar with conical-round sections (a small type found in Harifian sites), oblong

conical mortar with funnel rims and oblong conical mortar with shafts at the bottom (Fig. 2:

1, 2; Appendix A: IA.3, IA.3a-3c).

The mortars were fabricated and designed by carving, intensive pecking and coarse

grinding or abrading. Use-wear is demonstrated by fine grinding in the lower part of the

17 Oblong

conical

mortar

17.5-18.5/

6/36

Funnel rim;

conic-round

M; hard stone

at bottom

Rim & sides:

F Gr; hard stone:

Car, Fl, Pec & Gr

Com II,

beside no.

18, 21

Rim & upper

part eroded

18 Oblong

conical

mortar

16-17/4/54 Long & narrow

M: 6/4/21

Smooth -F Gr at

sides & bottom

Com II;

beside Inst

17,

21

Eroded rim;

pierced at

bottom

21 Round

cupmark

6.5-7/4/5 Deep concave Smoothed sides

& rim; radial

striations

Com II;

beside Inst

17

Eroded

& cracked on

1 side

30 Oblong

surface?

28X14 Flat Smooth Patina Com I;

beside no. 3

Thick Patina

Exo-karst

around

Debatable

* measurements in cm; (4) – estimated dimensions of complete tool; Com – Complex; Str- structure

A-Y; Inst – installation/s; RCI – rock-cut installation; M – mortar; OCM – oblong conical mortar;

m. – meter; L – Length; Sec – section/s; N – north; S – south; W – west; E – East; M – mortar; Car

– carving; Fl – flaked; Pec – pecked; Bat – battered; Gr – ground; Pol – polished; C – coarse; F – fine;

Arch-bot – archaeo-botanic; Conv – convex; Conc – concave; Sl – slightly.

1 This conclusion does not contradict the possibility that other stone implements were pre-planned

and designed for other purposes, such as coffins (van den Brink 2005: 180), cultic or offering

devices (see for example the small shallow cupmark beside oblong conical mortar, Tab. 2: 11; Fig.

3: 3), nor does it preclude the reuse of out-of-order/use oblong conical mortar for other purposes.

PLANT FOOD IN THE LATE NATUFIAN 139

mortar, by the formation of the shaft at the bottom and by a pierced bottom (both as the

result of intensive and long usage), infrequently by an oval shape and fine grinding of the

rim and rarely by radial striations in the upper part of the mortar (Figs. 1-3). Occasionally

a hard stone or stones were found in the lower part of the mortar; a phenomenon that also

occurred in other Natufian installations like cupmarks and basins. Traces of flaking, pecking

and intensive abrading on the stone and around it indicate the efforts to reduce and remove

it. Apparently the stone is part of the bedrock breccia and in some cases, when exposed

on the surface, the fabrication of the disused mortar was halted (Figs. 1: 3, 3: 1, 2). The

phenomenon, interpreted as a kind of symbolic or ceremonial activity by intentionally

inserting stones in the mortar - “… in some cases a stone was firmly jabbed in the shaft…this

Natufian phenomenon should be viewed also within a social and symbolic context…”[and]

“as an observable communication apparatus on the community level”, (Nadel and Rosenberg

2008), was also observed in rock-cut installations from historic periods.

The distribution of Natufian conical mortars coincides with the densest modern natural

stands of wild barley in the southern Levant, as documented at 22 sites, along the Rift Valley

from Jebel Sa’ide II in the north, by way of Eynan to Jericho in the south, in the Galilee

and Carmel at Hayonim Terrace and Raqefet Cave, in the Negev highlands at Saflulim and

possibly in southern Transjordan at Wadi Mataha. The bottom of a regular, ancient or modern mortar is usually flat or concave, suitable for

crushing or mashing with a pestle, while the pointed end of the conical mortar reduces the

pounding efficiency the narrower the cone becomes. Wide, conical mortars first appeared in

small numbers in the southern Levant during the Kebaran and the Geometric Kebaran at Ein

Gev I and Hefziba (Bar-Yosef 1990; Kaufman 1976). Large, wide conical mortars and small,

narrow mortars both occur in considerable numbers in the early Natufian. The oblong conical

mortar is exclusive to the Natufian culture, becoming most common in the late Natufian and

continuing until the end of the final Natufian, including the Harifian (see Appendix A for

a detailed description of different types of conic mortars). No oblong conical mortar has

been found in PPNA contexts. A narrow, conical mortar, much smaller than the Natufian

one, and dating to the late Iron Age, was found in sites in eastern Samaria, displaying similar

phenomena such as the cylindrical shaft and hard stone, which stopped the carving of the

mortar (Eitam 1996: Fig. 555).

THE OBLONG CONICAL MORTAR – A PROCESSING DEVICE FOR BARLEY

It is hypothesized that oblong conical mortars were used to remove the chaff from threshed,

barley seeds (as husk of barely and glume wheats are not peeled-of by threshing, Hillman

1984, 1985). Barley was selected among the wild cereals, as it was and still is the most

DAVID EITAM140

Figure 3. Rosh Zin 1. Oblong conical mortar stopped by hard stone which were reduced by flaking,

pecking, abrading of stone and sides around it (Table 2: 16); 2. Oblong conical mortar with conical-

round cross-section and flaked grinded hard stone at bottom, beside it oblong conical mortar with long

and narrow mortar and shaft and concave cupmark (Tab. 2: 17, 18, 21); 3. Oblong conical mortar,

eroded near bottom, and small shallow cupmark beside (Tab. 2: 11, 12); 4. Oblong conical mortar

with funnel rim, striae and eroded bottom (Tab. 2: 8); 5. Oblong conical mortar with shallow, oblong

surface(?) beside (Tab. 2: 3, 30).

PLANT FOOD IN THE LATE NATUFIAN 141

common wild cereal in the Levant (Harlan and Zohary 1966). This supposition will be

examined here by analyzing the morphological and technological features of the oblong

conical mortar, investigating historical evidence and ethnographic parallels, as well as by

experimental studies.

The historical evidence is sparse and scattered. The ancient Egyptians illustrated the use

of crushing implements in models and relief scenes of bakeries and breweries, where mortars

and pestles are regularly part of the scenes (Tooley 1995). Classical works on agriculture

(e.g. Cato: 10:4, 11:4) make it clear that de-husking of cereals and the removal of bran was

commonly performed in the ancient Near East and the Mediterranean region mainly by

mortar and pestle.

The ethnographic parallels focusing on the processing of glume wheats are quite general.

Hillman (1984) is the only scholar who describes in detail traditional, domestic processing of

barley in eastern Turkey, performed with two kinds of wooden mortars. Initially, the remains

of the chaff were removed from the threshed grains by pounding the spikelets in a conical

mortar with a pestle. Next, the unbroken, cleaned grains were placed in a mortar with a flat

bottom, after being separated from the broken bits of chaff, and crushed into groats with the

aid of a wooden mallet. Hillman clarified the need for the conical shape in preventing the

breakage of the grain by describing the cleaning of rice grains from their husks and bran

through use of a conical basalt mortar with two kinds of mallets, without damage to the

perfectly whole grain.

Among experimental research, the most relevant to this issue was conducted by Samuel,

who successfully de-husked Emmer spikelets by pounding them in a small, concave mortar

from 14th century BC El Amarna and a replica of a long, thick wooden pestle (Nesbitt and

Samuel 1995; and references). The process of de-husking carried out in the experimental

operation is probably also depicted in the Egyptian relief from the tomb chapel of Hetpherakht

(rather than the crushing of the wheat into groats as suggested by Wilson 1988). This was

accomplished by direct, vertical strokes in a mortar with pestles held by two persons,

identical to the ones used in Samuel’s experiment. The grains, separated from the glumes by

sieving, were eventually milled by handstone on a grinding slab (ibid. Fig. 8). In the baking

and brewing scene from the tomb of Intef-inker at Thebes, dating to the 20th century BC, the

same procedure of cereal processing is represented, but with different pounding devices: an

oblong wooden(?) mortar (unfortunately, its cross-section is invisible, unlike the stone mortar

illustrated in the Hetpherakht relief) and two long, thin pestles (Davies and Gardiner 1920:

Pl. XI). It seems that here the scene depicts barley processing. It is worth mentioning that the

material dropping under the sieve looks finer than that illustrated in the Hetpherakht relief,

and possibly portrays the small bits of chaff, as opposed to the relatively large spikelet forks

and broken glumes of Emmer wheat.

DAVID EITAM142

It seems that the chaff was removed either by rubbing the grains against each other, or by

rubbing them against the sides of the mortar; the narrower the cone was, the more efficient

was the de-husking, hence resulting in fewer broken grains. While the installation is indeed

tapered, our experience in cleaning dozens of oblong conical mortars filled with earth and

stones, indicates that the contents can easily be removed by hand and using a wooden stick.

THE OBLONG CONICAL MORTARS AT HRUK MUSA AND ROSH ZIN

Hruk Musa (holes of Musa, Arabic) is located in the northern part of the lower Jordan Valley,

about 20 km north of Gilgal and Netiv Hagdud, at the base of the Samarian hills, at an

elevation of 238-246 m below sea level.2 The 5.2 dunam size site is situated on an east facing

slope. Some 20 structures are visible on the surface and the surface finds indicate that it likely

represents a single-period occupation dating to the final Natufian. The site is framed by wide

bedrock outcrops, on the west, and by large boulders on the north and on the south. The well

preserved architectural surface-remains include: a. Terrace walls built along its east side. b. A

large structure, constructed of large stones and boulders (measuring 11x10 m), located in the

center of the site. c. Eight oval-shaped house walls (average measurements 2.4x3.6 m) and

similar-sized oval structures, marked by different recent flora (likely indicating more houses),

occupy most of the site area. e. Nine, small, circular house walls, measured in average 2x3.2 m

(some with rectangular built-in installations measuring 1.2x0.7 m), constructed on the north

side of the site (Fig. 5).

Sixty-five rock-cut installations, among them 31 oblong conical mortars, were identified

on the surface of the site area and its surroundings, the majority cut in bedrock, and others

chiseled in rocks in and around the structures (Table 1, Figs. 1, 2). The distribution of the

installations was determined by the location of projecting rocks in the immediate vicinity

of the settlement, but it seems that they also had social significance. Of special interest are

an open space, located beyond the immediate site expanse, and the place of the installations

of Complex VI, positioned ca 200 m south of the site. Flat and defined bedrock outcrops,

perhaps threshing floors (where straw and awns were separated from the spikelets prior to

3 The site (mistakenly named Huzuk Musa) was discovered in February 1989 by the Manasseh Hill

Country Survey and briefly described and dated by Winter and Eitam (in Zertal 2005: see Fig.

467). The site surface was surveyed in greater detail by the author in 2007/8, the results of which

are summarized herein. The chronological assignment of the site (Winter 2005: 576-567) was

based on surface finds of about 2500 flint artifacts including a high number of sickle blades. Arrow

heads were not found and generally the collection resembled the assemblage of Nahal Ein Gev II,

located in the Upper Jordan Valley in setting, attributed to the end of the Late Epipalaeolithic (Bar-

Yosef and Belfer-Cohen 2000; Winter pers. comm..).

PLANT FOOD IN THE LATE NATUFIAN 143

Figure 4. Hruk Musa, selection of lithic finds: 1-8: Borers; 9-12: Sickle blades; 13-15: Microlithes; 16:

Micro-end scraper; 17: End scraper; 18. Burin (Winter 2005, Figs. 118-120).

DAVID EITAM144

Figure 5. Map of Hruk Musa: wide bedrock outcrops and boulders at the north, west and south; parallel

terrace walls in the east X1-X, Y1, Y, and one line terrace walls combined with boulders Z, W, U; house

walls A-J and N-T; large structure K, L, rock-cut installations (in grey dots) gathered on bedrock I, II or

cut in boulders and chiseled in rock in and around the structures; complexes V with 9 cupmarks and VI

with threshing floors and accompanying rock-cut installations.

PLANT FOOD IN THE LATE NATUFIAN 145

de-husking) accompanying other installations, were located on the top of a high cliff for easy

winnowing and hygienic reasons, but their placement emphasizes the broad expanse of the

settlement. It seems likely that a considerable number of the rock-cut installations were in

use simultaneously, bearing in mind the relevant short duration of the settlement..

The late Natufian site of Rosh Zin is located in the Negev Highlands near the springs of

Ein Avdat at an elevation of 500 m above sea level (Henry 1973a, 1973b, 1976). The site,

extending over an area of ca. 800 m2 on a small exposed hill, included four small circular

structures, in one of which a large monolith was placed. Three stratigraphic phases, all

relating to the late Natufian, were noted. The site is bordered on the north and south sides

by oblong, narrow bedrock exposures where 17 rock-cut installations were described by

Henry. In a more recent (2005) surface survey of the site we identified a total of 34 rock-

cut installations, of which 14 were oblong conical mortars (Table 2, Fig. 6). As most of the

installations were unstratified (excluding rock-cut installations nos. 11, 12 near the monolith,

Fig. 3:3), it seems plausible to assume that some of the rock-cut installations were in use

throughout much of the settlement’s duration.

The stone monolith probably relates to some sort of ceremonial or ritual activity that took

place on the site (Henry 1976). Are we confronted with a phenomenon that contradicts our

assumption, and are the oblong conical mortars indeed cultic devices? Apparently not, for

three reasons: 1. 95% of the 139 oblong conical mortars recorded to date have been found

in non-cultic contexts, 2. in most of its years Rosh Zin was a campsite and, 3. even people

occupied with cultic activity had to eat to survive. Maybe a few de-husked grains or groats of

wild barley were added to the presumed offering of groundstone tools and blade cores (Henry

1973a: 208) at the foot of the monolith.

SUMMARY

We plan to conduct experiments in the near future using three archaeological rock-cut

installation (out of many dozens) in order to test our hypothesis. Starting by threshing the

spikelets by beating them on threshing floor rock surface with a stick, separating the straw

and awns, followed by removing the remained awns by vertical strokes with a long wooden

pestle in the near-by rock-cut wide conical mortar. The de-husking will be done with the

wooden pestle, peeling the chaff (the lemma and palea, Charles 1984), in oblong conical

mortar, while sorting the chaff from the grain with sieves.

The development and sporadic use of the wide conic mortar in the Kebaran and Geometric

Kebaran, and more frequently in the early Natufian, support the generally accepted view

that sees drastic changes in subsistence strategies during this period of time (Flannery 1969,

1996). The efficiency and “mass production” of de-husking and probably of groat making,

DAVID EITAM146

Figure 6. Revised map of Rosh Zin (after Henry 1973): structures and monolith; complex I with rock-

cut installations (in black dots): oblong conical mortars 1-3, 32 and cupmarks 26-30 on northern oblong

bedrocks (with a line of stones), and on small rocks; complex II with oblong conical mortars 6, 8, 16-

18, 20, 22, 24 and cupmarks 5, 9, 10, 15, 19, 21, 23, 25, 32, 36 on southern oblong bedrock and 2 rock

faces; complex III with oblong conical mortar 11 and cupmark 12, installations cut in block stones 13,

14, 33-35.

and eventually the preparation of barley meals, whether roasted, stewed, etc. (Postgate

1984), indicate a shift towards processed vegetable food consumption that occurred during

the late Natufian. This shift was most likely associated with the construction of sealed storage

facilities and with the cultivation of wild barley (Bar-Yosef 1998; Willcox 2005; Tanno and

Willcox 2006), matters which stand in contradiction to the generally accepted return to

foraging during the late Natufian (e.g. Goring-Morris and Belfer-Cohen 2003). On the other

hand, the placing of an impressive (but out-of-order) device essential for the preparation

of barley meals with the dead ancestors in graves at Nahal Oren (five specimens; Fig. 2: 1)

and at Raqefet cave (one specimen, pers. obse., 14.8.2006) emphasizes the importance of

barley in the life of the late Natufian people and the shift toward a pre-agricultural stage.

The disappearance of oblong conical mortars in the Neolithic hints towards the appearance

PLANT FOOD IN THE LATE NATUFIAN 147

of a cultural changes that are visible at Hruk Musa. The size of the settlement, with about 30

domestic structures resembles the scale of PPNA village communities, although the surface

lithic finds and the numerous oblong conical mortars, as opposed to very few cupmarks at the

site, indicate that it belongs to the Late Epipalaeolithic world.

During the PPNA wild barley probably became the staple food (Kislev 1997), but its

methods of preparation changed. Complexes of oblong conical mortars and other installations

in bedrock, which reflect preparation and most likely eating, of quantities of food together by

a group of people, were replaced by cupmarks cut in stone slabs within domestic structures.

All these point toward a new technique of de-husking and preparation of barley meal in small

quantities, implying a shift from the communal domain to the domestic-private one.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This paper is part of my Ph.D. thesis at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Thanks go to

Prof. Anna Belfer-Cohen and Prof. Nigel Goring Morris, my advisors, and to Lure Dubreuil

for reading the paper and for their useful criticisms and comments. I am also grateful to

Haim Winter for his advice and providing Fig. 4. Needless to say, I alone am responsible

for any errors in this paper. The field work in Hruk Musa during 2003/4 was done as part of

the Manasseh Hill Country Survey and in 2007 as part of the Archaeo-Industry Survey on

behalf of the Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Field research at

Rosh Zin in 2005 was conducted on behalf of The Institute of Archaeology, Haifa University.

Thanks to Moshe Einav, Gill and Ziva Cooper, Shraga Hashman, Oren Cohen from the

Manasseh Hill Country Survey team for assisting in the field research, to Anna Yamim

(surveyor) for drawing the plan of Hruk Musa, Ruhama Piperno-Beer for drawing the Rosh

Zin map, and Marina Shuisky for drawing the artifacts.

REFERENCES Bar-Yosef O. 1990. The Last Glacial Maximum in the Mediterranean Levant. In: C. Gemble and O.

Soffer (eds.), The World at 18000 BP (2). Unwin Hyman, London: 58-77.

Bar-Yosef O. 1998. The Natufian Culture in the Levant, Threshold to the Origins of Agriculture.

Evolutionary Anthropology 6 (5): 159-177.

Bar-Yosef O. and Goren N. 1973. Natufian Remains in Hayonim Cave. Paléorient 1: 49-68.

Bar-Yosef, O. and Belfer-Cohen, A. 2000. Nahal Ein Gev II - A Late Epi-Paleolithic Site in the Jordan

Valley. Mitekufat Haeven, Journal of the Israel Prehistoric Society 30: 49-71.

Brink, E.C.M. van den. 2005. Chalcolithic Burial Caves in Costal and Inland Israel. In: Brink, E.C.M.

van den and Gophna, R. (eds.) Shoham (North), Late Chalcolithic Burial Caves in the Lod Valley,

Israel. IAA Reports 27. Jerusalem: 175-190.

Cato, M.P. 1936. On Agriculture. The Loeb Classical Library. New York

DAVID EITAM148

Davies N.G. and Gardiner A.H. 1920. The tomb of Antefoker, Vizier of Sesostris I, and of his wife,

Senet (No. 60). The Theban Tombs Series Second Memoir. George Allen & Unwin, London.

Eitam D. 1996. Survey of Agricultural Installations. In: A. Zertal. The Menasseh Hill Country Survey,

The Eastern Valleys and the Fringes of the Desert Vol. II. Tel Aviv (Hebrew): 681-738.

Eitam D. 2005. The Installations and the Ground Stone Tools. In: A. Zertal The Manasseh Hill Country

Survey, from Nahal Bezek to the Sartaba. Vol. IV. Haifa and Tel Aviv (Hebrew).

Flannery K.V. 1969. Origins and Ecological Effects of Early Domestication in Iran and the Near East.

In: P.J. Ucko and G.W. Dimbleby (eds.), The Domestication and Exploitation of Plants and Animals.

Gerald Duckworth and Co., London: 73-100.

Flannery K.V. 1995. Prehistoric Social Evolution. In: EMBER C.R. and EMBER M. (eds.) Prehistoric

Social Evolution: 1- 26. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs.

Goring-Morris A.N. and Belfer-Cohen A. 2003. Structures and Dwellings in the Upper and Epi-

Palaeolithic (ca. 42-10K BP) Levant: Profane and Symbolic Uses. In: O. Soffer, S. Vasil’ev and J.

Kozlowski (eds.), Perceived Landscapes and Built Environments. Oxford, BAR International Series

1122: 65-81.

Harlan J.R. and Zohary D. 1966. Distribution of Wild Wheats and Barley. Science 153: 1074-1080.

Henry D.O. 1973a. The Natufian of Palestine: Its Material Culture and Ecology. University Microfilms.,

Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Henry D.O. 1973b. The Natufian Site of Rosh Zin: A Preliminary Report. Palestine Exploration

Quarterly 105:129-140.

Henry D.O. 1976. Rosh Zin: A Natufian Settlement near Avdat. In: A.E. Marks (ed.), Prehistory and

Paleoenvironments in the Central Negev, Israel. SMU Press, Dallas: 317-347.

Hillman G.C. 1984. Traditional Husbandry and Processing of Archaic Cereals in Recent Times, Part I:

The Free-Threshing Cereals. Bulletin on Sumerian Agriculture I: 129-130.

Hillman G.C. 1985. Traditional Husbandry and Processing of Archaic Cereals in Recent Times, Part II:

The Glume-Wheats. Bulletin on Sumerian Agriculture II: 1-31.

Kaufman D. 1976. Typological and Technological Comparison of Two Epi-Paleolithic Assemblages

from the Coastal Plain of Israel. Unpublished M. A. Thesis. Tel Aviv University.

Kislev M.E. 1997. Early Agriculture and Paleoecology of Netiv Hagdud. In: O. Bar-Yosef and A.

Gopher (eds.), An Early Neolithic Village in the Jordan Valley, Part I: The Archaeology of Netiv

Hagdud. Harvard University, Cambridge: 209-236.

Nadel D. and Rosenberg D. 2008. Unpublished Abstract of a paper at The Symposium on Direct and

Indirect Evidences of Natufian Plant Exploitation Strategies. 73rd SAA, Vancouver.

Nesbitt M. and Samuel D. 1995. From Staple Crop to Extinction? The Archaeology and History of the

Hulled Wheats. In: S. Padulosi, K. Hammer and J. Heller (eds.), Hulled Wheat, Proceedings of the

First International Workshop on Hulled Wheats, 21-22 July 1995, Castelvecchio: 2 - 41.

Postgate J.N. 1984. Processing of Cereals in the Cuneiform Record. Bulletin on Sumerian Agriculture

I: 103-113.

Tanno K-i. and Willcox G. 2006. How Fast was Wild Wheat Domesticated? Science (Brevia) 311:

1886.

Tooley A.M.J. 1995. Egyptian Models and Scenes, Shire Egyptology, Merlins Bridge.

Willcox G. 2005. The Distribution, Natural Habitats and Availability of Wild Cereals in Relation to

their Domestication in the Near East: Multiple Events, Multiple Centers. Vegetation History and

Archaeobotany 14: 534-541.

PLANT FOOD IN THE LATE NATUFIAN 149

Wilson H. 1988. Egyptian Food and Drink, Shire Egyptology, Bucks.

Winter H. 2005. The Lithic Findings. In: A. Zertal, The Manasseh Hill Country Survey, from Nahal

Bezek to the Sartaba, Vol. IV. Haifa and Tel Aviv (Hebrew).

Wright K.I. 1991. The Origins and Development of Ground Stone Assemblages in Late Pleistocene

Southwest Asia. Paléorient 17 (1): 19-45.

Wright K.I. 1992. A Classification System for Ground Stone Tools from Prehistoric Levant. Paléorient

18 (2): 53-81.

Zertal, A. 2005. The Manasseh Hill Country Survey, from Nahal Bezek to the Sartaba. Vol. IV. Haifa

and Tel Aviv. (Hebrew).

DAVID EITAM150

Appendix A: Typology List of types and subtypes of Conical Mortars

I. Rock-cut installations

A. Mortars

1. Small, narrow cone mortar. SHAPE: round or oval, with cone of + 30 degrees, sometimes

with funnel rim, pointed or concave end or pointed shaft. FACE: sides & bottom – pecking &

grinding or fine grinding, sometimes radial striae on sides.

1a. Small, narrow truncated mortar. SHAPE: like IA.1, but with flat or slightly concave

bottom. FACE: smooth at low sides & bottom.

2. Small to large, wide cone mortar. SHAPE: round with cone of +50 degrees, short,

pointed or cylindrical shaft at bottom. STYLE: sometimes exact circle with slightly bulging,

smoothed ring or sharply cut rim. FACE: sides – coarse or fine grinding, sometimes with

radial striae on lower part; shaft – smooth.

3. Large to medium oblong conical mortar. SHAPE: round or oval mortar, with oblong,

narrow cone of + 20 degrees & pointed end. FACE: on sides & bottom – coarse grinding or

fine grinding.

3a. Oblong conical mortar with conical-round section. SHAPE: like IA.3 with slightly

curved or almost parallel sides & conical bottom. FACE: rim – pecking & fine grinding;

sides – grinding on pecking, or coarse grinding on upper sides & fine grinding on lower

sides.

3b. Oblong conical mortar with funnel rim. SHAPE: like IA.3 with long or short funnel

rim. STYLE: rim – round or sharp edged. FACE: along funnel rim – pecking & coarse or fine

grinding. Seldom – oval shape and wear, probably due to diagonal motion of pestle; always

fine grinding along cone.

3c. Oblong conical mortar with shaft at bottom. SHAPE: like IA.3 with small, cylindrical

or pointed shaft at bottom. FACE: sides – fine grinding on upper sides, sometimes fine

grinding or with pecking, all along sides; always fine grinding on shaft.

B. Stone vessels. Vessels with well-defined, uniform rim & base, continuous external &

internal finished surfaces & consistent thickness of walls (Wright 1992, 75).

1. Large mortar with wide conical section. Like IA.2, but round cone of + 60 degrees with

external finished surface. SHAPE: external – round vase (Wright 1992, 77) with flat base.

1a. Large, goblet mortar with wide conical section. Interior: round cone of + 55 degrees.

External – high prominent base, with or without wavy engraving, simple or square rim with

or without decorations.

2. Large mortar with conical-round section. Like IA.3a with cone of + 35 degrees.

SHAPE: external – varied from ovate to rhombus-like section, vase with convex sides with

flat or round base, to oblong conical-round vessel.

PLANT FOOD IN THE LATE NATUFIAN 151

C. Stone block tools

1. Oblong conical mortar cut in boulder. Round boulder with flat top & irregular-round

bottom or square boulder with curved corners & sides. Seldom the boulder has cylindrical

shape & pointed-round bottom. SHAPE: internal – oblong conical mortar (like IA.3, IA.3a-

3c) section with narrow cone of + 17 degrees. External surface of boulder: rough flaking and

course pecking on sides and bottom. Top – intensive fine pecking & fine grinding; intensive

pecking on upper part of one side.

II. Mobile tools – Ground stone tools

A. Mortars. Lower stationary stones, in a pair of tools, used for processing & preparing

foodstuff or other materials. Small to medium, round or elliptic hewn depression with

concave or conical section cut in stone block.

1. Small, conical mortar. Small to medium, conical bowl cut in irregular, flaked or pecked

stone block.

B. Stone vessels

1. Small vessel with wide conical section. SHAPE & FACE: internal – like IA.2; external

finished surface of concave section.