Woodland vegetation, firewood management and woodcrafts at Neolithic Çatalhöyük

Pinus and Prostomis: a dendrochronological and palaeoentomological study of a mid-Holocene woodland...

Transcript of Pinus and Prostomis: a dendrochronological and palaeoentomological study of a mid-Holocene woodland...

The Holocene 125 (2002) pp 585ndash596

Pinus and Prostomis a dendro-chronological and palaeoentomologicalstudy of a mid-Holocene woodlandin eastern EnglandGretel Boswijk1 and Nicki J Whitehouse2

(1School of Geography and Environmental Science University of AucklandPrivate Bag 92019 Auckland New Zealand 2School of Archaeology andPalaeoecology Queens University Belfast Belfast BT7 1NN Northern Ireland)

Received 9 March 2001 revised manuscript accepted 4 December 2001

Abstract Tree-ring analysis of subfossil Pinus sylvestris L and Quercus sp and their associated subfossilinsect assemblages from tree rot-holes have been used to study a prehistoric forest buried in the basal peatsat Tyrham Hall Quarry Hat eld Moors SSSI in the Humberhead Levels eastern England The site provideda rare opportunity to examine the date composition age structure and entomological biodiversity of a mid-Holocene Pinus-dominated forest The combined approaches of dendrochronology and palaeoentomology haveenabled a detailed picture of the forest to be reconstructed within a precise time-frame The Pinus chronologyhas been precisely dated to 2921ndash2445 bc against the English Quercus master curve and represents the rstEnglish Pinus chronology to be dendrochronologically dated A suite of important xylophilous (wood-loving)beetles that are today very rare and four species that no longer live within the British Isles were also recoveredtheir disappearance associated with the decline in woodland habitats as well as possible climatic change Thesubfossil insects indicate that the characteristic species of the sitersquos modern-day fauna were already in place4000 years ago These ndings have important implications in terms of maintaining long-term invertebratebiodiversity of forest and mire sites

Key words Dendrochronology palaeoentomology Pinus Quercus subfossil insects Holocene HumberheadPeatlands Hat eld Moors eastern England

Introduction

The abundance of Quercus petraea LQuercus robur L (sessileoakpendunculate oak collectively Quercus) and Pinus sylvestrisL (Scots pine hereafter referred to as Pinus) macrofossils pre-served in lowland raised mires in Great Britain and Ireland indi-cate that both species but particularly Pinus were formerly sig-ni cant components of raised-mire habitats (Pilcher 1990 Pilcheret al 1995) Across much of Europe Scandinavia and EurasiaPinus is a common tree species occupying a wide range of differ-ent habitats from dry well-drained soils to wet acidic mires(Rodwell and Cooper 1995) In Great Britain the current naturalrange of Pinus is largely restricted to the Scottish Highlandsalthough isolated patches occur in some areas of lowland heathPinus was abundant during the early Holocene being presentwidely but locally in southern England 9000 years ago spreadingnorthwards between 9000 and 8500 years ago (Birks 1989) and

Author for correspondence (e-mail gboswijkaucklandacnz)

Oacute Arnold 2002 1011910959683602hl569rp

reaching its most extensive distribution between 7500 and 4400years ago (Bennett 1995) However around 4400 cal BP Pinusappears to have undergone a sudden and widespread decline(Bennett 1984 1995 Bridge et al 1990 Gear and Huntley1991) The most widespread view is that the decline was causedby a shift to cooler and wetter climatic conditions promoting theexpansion of peat to the detriment of Pinus (Bennett 1984 Gearand Huntley 1991 Anderson et al 1998 Lageard et al 1999)Trees growing in marginal locations may have been particularlyvulnerable to short-term acidi cation or increased soil moistureparticularly if they were already stressed by a longer-term climaticchange (Blackford et al 1992 but see Hall et al 1994)Bradshaw (1993) notes that a decreased occurrence of wild re inresponse to possible climatic change may have been a contribu-tory factor in the decline of populations

Quercus is also found widely in Europe and Great Britain By5000 years ago Quercus woodland extended into the far north ofScotland and was widely distributed elsewhere (Bennett 1989Pilcher 1990) retaining a signi cant presence to the present day

586 The Holocene 12 (2002)

Quercus woodland grows predominantly on poor infertile andacidic soils (Bennett 1989) The recovery of numerous subfossilremains from fen-peat in England and Ireland indicates that thisspecies was a component of fen woodlands sometimes precedingor overlapping with the development of raised mire and coloniz-ation of acidic peat by Pinus (Godwin and Deacon 1974 Pilcher1990 Lageard and Chambers 1993)

In this paper we present the combined results of a palaeoento-mological and dendrochronological investigation of a recentlyexposed subfossil forest from Hat eld Moors in the HumberheadLevels eastern England The forest consisted predominantly ofPinus interspersedwith Betula and isolated Quercus remains Themain focus of the investigation concentrated on the numerousPinus remains and their associated insect faunas as Quercusremains formed only a very minor component of the fossil forestwith just one tree providing material suitable for dendrochronol-ogical dating and fossil insect analysis Dendrochronology wasapplied to date precisely the span of the Pinus woodland inaddition to providing information on its history and dynamics(Boswijk 1998) The suitability of this species for tree-ring analy-sis has been demonstrated by the construction of long Pinuschronologies in Europe (Zetterberg et al 1996) and robust sitechronologies from raised bogs in Great Britain (Chambers et al1997 Boswijk 1998 2002 Lageard et al 1999) and Ireland(McNally and Doyle 1984 Pilcher et al 1995) The primary aimof the subfossil insect study was to characterize the faunal biodiv-ersity of undisturbed Pinus woodland and to examine the sitersquosdevelopment from a palaeoentomological perspective and itswider implications (Whitehouse 1998)

These two palaeoenvironmental studies when combinedcharacterized the biodiversity of undisturbed primary woodlandwithin a de ned period Other palaeoenvironmentalevidence fromHat eld Moors (cf pollen and plant macrofossil studies carriedout by Smith 1985) was also considered in the investigationAbundant charcoal was recovered from the peat samples and sur-face-charred trees were observed but consideration of the roleof re in the early mire landscape has been addressed elsewhere(Whitehouse 2000) The project formed part of a wider palaeoen-vironmental investigation of Thorne and Hat eld Moors Sites ofSpecial Scienti c Interest (SSSI) (Boswijk 1998 Whitehouse1998) and their surrounding oodplains (Whitehouse 1998)

The Humberhead Peatlands

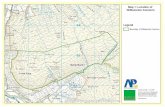

Thorne and Hat eld Moors are two adjacent but distinct raisedmires within the Humberhead Levels an extensive area of formerwetlands in south Yorkshire and Lincolnshire (Figure 1) wherepeat extraction during the mid-1990s uncovered substantial areasof subfossil Quercus and Pinus The Moors have formedimportant foci for palaeoenvironmental research with much pre-vious work largely concentrating on Thorne Moors (cf Erdtman1928 Smith 1958 Buckland and Kenward 1973 Buckland1979 Smith 1985 2002 Roper 1993 1996 Whitehouse 19931997a Dinnin 1997 Boswijk 1998 2002) Here recent den-drochronological analyses of Pinus showed that the spatial andtemporal pattern of Pinus colonization correlated with the expan-sion and contraction of the mire (Boswijk 1998 2002)

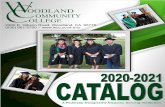

Subfossil insect analysis of material from the basal deposits ofThorne Moors has identi ed 20 beetles (Coleoptera) that are nowextinct in Great Britain (Buckland and Kenward 1973 Buckland1979 Roper 1996 Whitehouse 1997a 1977b 1998) Lessresearch has however been carried out on Hat eld Moors (Figure2) On this site south of Thorne Moors peat had formed directlyover gently undulating windblown sands (Smith 1985 2002)These were initially deposited during the Younger Dryasalthough some reworking may have occurred during the Holocene

THORNE MOORS

SOUTH

YORKSHIRE

MISTERTON CARR

Cowick

Sutton Common

Rawcliffe

Goole

Swinefleet

Adlingfleet

Eastoft

Crowle

Scunthorpe

Thorne Colliery

Thorne

Stainforth

Tudworth

Bradholme

Hatfield Sandoft

Wroot

Belton

N

5km

River Aire Old course of

Old course of

River Don

River Went

River Went

TurnbriggDike

New Junction

Canal

River Don

Dutch River

Goole Fields

River OuseHumber Estuary

RiverTrentSwinefleet

Warping Drain

Old course ofRiver Don

Stainforth and

Keadby Canal

Folly Drain

Old course ofRiver Idle

Hatfield Chase

Old course ofRiver Don

River IdleBykers Dike

30

30

30

30

Epworth

15

Isle of Axholme

15

HATFIELD MOORS

LindholmeIsland

0

Figure 1 Location map of Hat eld Moors and the Humberhead Levelseastern England (after an original by PI Buckland OacuteThorne and Hat eldMoors Conservation Forum) Hat eld Moors NGR SE 700060 lat 53deg44rsquoN long ndash0deg 57rsquoW Thorne Moors NGR SE 730160 lat 53deg 329 Nlong ndash0deg 57rsquoW

PackardsSouth

PackardsNorth (2)

PackardsNorth (1)

HAT 4

cal BC

cal BC

Tyrham HallQuarry

c2000 BC

3300-2445 BC(Pinus woodland)

LIND A

HAT 1

LIND B

HAT 3

Kilham

3350-2930cal BC

West

ISLANDLINDHOLME

HAT 2

Porters Drain

cal BC

West Ash Dump (1)

West Ash Dump (2)

0 1 2 km

form

e r course of River Torne

former course of River Idle

2900-2350

2900-2660

1520-1390 cal BC

3090-2890

N

Pollen Sites

Fossil Insect Sites(Whitehouse 1998)

(Smith 1985)

Figure 2 Map of Hat eld Moor with study sites and basal peat initiationdates (reprinted from Whitehouse et al 2001 Figure 58)

(Gaunt 1994 Bateman 1995 Bateman et al 2000) The sandsoverlie the late Devensian lacustrine clay-silts of proglacial LakeHumber (Gaunt 1994) In places sand dunes protrude throughthe milled peat A late-Devensian end-moraine outcrops in thecentre of the site on Lindholme Island (Gaunt 1994) The Mooris bounded on the north east and south by alluvium associatedwith the former courses of the Rivers Don Idle and Torne

On Hat eld Moor where peat depth is greater than at ThorneMoors Pinus trees were observed on parts of the milled bog theirstunted size and shape suggestive of growth on wet mire How-ever Tyrham Hall Quarry on the western edges of the moor wasdifferent Here an area of basal peats had been exposed prior tosand and gravel extraction revealing numerous Pinus stumps andtrunks of a size indicative of mature woodland (Urwald) Thetrees were no longer in situ making determination of the phases ofwoodland development impossible on stratigraphicgrounds alone

Gretel Boswijk and Nicki J Whitehouse Pinus and Prostomis a dendrochronological and palaeoentomological study 587

Many of the trees were rooted into the underlying sands indicat-ing that they represented either a pre-peat forest or one thatbelonged to the very early stages of mire development Inaddition it was unclear whether the trees represented a singlephase of Pinus growth or several successive episodes of growthand decline similar to the pattern observed at Thorne Moors(Boswijk 1998 2002) Peat formation began at about the sametime on both mires (around 3000 cal bc) but a detailed palaeoen-vironmental study by Smith (1985 2002) and more recently byWhitehouse (1998) suggested that the developmental history ofthe sites was different

Dendrochronology

MethodologyCross-sections were taken from the lower trunks of 25 Pinus anda single Quercus (THQ01-26) that were in a 100 3 100 m areaof the quarry that was being cleared of peat The samples wereair-dried and then sanded using progressively ner sandpaper toreveal the ring sequence clearly All the samples had over 50rings which is the minimum number of rings required to deter-mine whether a ring sequence is unique (Baillie 1982)

Baillie (1982) describes the principles and methodology of den-drochronologyThe ring sequences were measured to an accuracyof 001 mm using a binocular microscope and a travelling stageAn input program part of the Dendro for Windows suite (Tyers1999) recorded ring-widths Quercus has a consistent growth pat-tern and the measurement of a single radius is considered rep-resentative of the ring sequence (Baillie 1982) For Pinus a mini-mum of three radii per cross-section were measured allowingpotential problems such as locally absent rings to be identi edand a reliable mean ring sequence to be produced for each Pinussample (Pilcher et al 1995 Zetterberg et al 1996) The CROSprograms (Baillie and Pilcher 1973 Munro 1984) were used toaid cross-matching The CROS programs measure the correlationcoef cient between samples at every position of overlap whichare expressed statistically as a Students t-value For Quercus a t-value of 35 and over is usually indicative that one samplematches another providing the visual match is acceptable (Baillie1982) For Pinus statistical testing of Pinus data by Pilcher et al(1995) indicates that t-values of 4 or greater may be signi cantAt all stages the suggested matches were visually checked usingplotted graphs of the ring sequences Table 1 lists details of theQuercus and Pinus samples

ResultsThe Quercus sample cross-matched with Quercus from ThorneMoors and was dated to 3618ndash3418 bc by comparison withEnglish prehistoric Quercus chronologies (Whitehouse et al1997 Boswijk 1998) The outer surface of the tree as well asthe pith had rotted and the absence of bark edge means that theactual death-date is unknown but the addition of the minimumnumber of sapwood rings expected to be present (Hillam et al1987) provides a terminus post quem of 3408 bc The contempor-ary Quercus woodland at Thorne Moors continued growing until3017 bc but little is known about the extent of Quercus woodlandat Hat eld Moor or its spatial and temporal relationship with thePinus woodland

A 21-tree Pinus chronology (PISYHat eld) was established(Tables 1 and 2) Four samples could not be cross-matched dueto unresolvable problems within the ring sequences caused byvery narrow bands of rings or multiple missing rings The undatedsamples included a tree from which a rot-hole sample (K) forinsect remains was collected

The chronology cross-matched with a oating Pinus chron-ology from Thorne Moors (PISYThorne Boswijk 1998 2002)

but the absolute dating of PISYHat eld was dependent on inter-species cross-matching against the English prehistoric Quercusmaster curve (Hillam et al 1990 Brown and Baillie 1992) Thedating of Pinus against Quercus chronologies has been shown tobe successful in Ireland (Pilcher et al 1995) and proved to beequally successful in England as the chronology was dated pre-cisely to 2921ndash2445 bc (Table 3) PISYHat eld was also foundto be contemporary with a phase of Pinus from Garry Bog CoAntrim Ireland (Pilcher et al 1995) and White Moss CheshireEngland (Chambers et al 1997 Lageard et al 1999) Duringtree-ring analysis consideration was given to the possibility thatthe Pinus could contain a strong site-specic growth pattern thatmay have overridden the common climate signal on which cross-dating is dependent (Baillie 1982) inhibiting cross-matchingbetween the Quercus and Pinus chronologies Radiocarbon dateswere obtained from two Pinus samples THQ21 (4125 6 45 BPSRR-5829) and THQ23 (4105 6 45 BP SRR-5834) These treeswere included in PISYHat eld and were dated absolutely by den-drochronological cross-matching

The chronology PISYHat eld spans 477 years (Figure 3)Between 2921 and 2610 bc three cohorts of Pinus were estab-lished Almost half the trees however have start dates within a35-year period between 2921 and 2887 bc indicating that con-ditions were optimal at this time to support the germination andgrowth of new recruits The length of ring sequences ranged from73 years to over 336 years While the steady rate of die-back over400 years is probably indicative of natural woodland mortalitythe pattern of end and start dates suggests that stress events mayalso have contributed to the death of some trees creating suitablegaps in which seedlings could be established

Stress events can be indicated by narrow ring phases whichoccur when growth is restricted perhaps as a result of changesin the local or immediate environments or by events speci c toindividual trees The years 2857ndash5 bc stand out as indicating asigni cant event which appears to have affected the growth ofseveral trees (Figure 4) The sampled trees show a rapid declinein ring-width at this time with some Pinus producing locallyabsent rings for these years While most recover the growth ofat least two trees was irrevocably altered Sample THQ07 diedwithin a decade while the ring sequence for THQ11(unmeasurable after 2865 bc) became extremely narrow althoughthe tree continued to grow until at least 2812 bc This sampledisplayed lobate growth the initiation of which coincides with anearlier narrow band at 2905 bc suggesting that the tree hadslumped and was growing at an angle The combination of narrowrings on many of the samples and the occurrence of lobate growthon some trees suggests that temporarily at least the area was verywet and the underlying substrate unstable

Subfossil insect fauna

MethodologySix contexts were bulk-sampled for subfossil insect analysis Fivesamples were collected from Pinus rot-holes and one from aQuercus rot-hole The extraction of subfossil Coleoptera followedthe paraf n otation technique devised by Coope and Osborne(1968) Identi cation of insect subfossil material was carried outthrough the use of standard British and other European entomo-logical keys and by direct comparison with modern material OnlyColeoptera (beetles) were identi ed

Much of the rot-hole material was in exceptional conditionwith many of the subfossil insects still articulated suggesting alargely in situ death population particularly those invertebratesassociated with wood However there was also an allochthonouselement to the faunas such as the water beetles which presum-ably became incorporated into the rot-holes when the dead trees

588 The Holocene 12 (2002)

Table 1 Details of the dated oak and pine samples from Tyrham Hall Quarry

Sample Dimensions (mm) No of rings Pith Bark AGR Date span (bc) End dates (bc) Comments

Quercus25 577 3 350 201 ndash ndash 149 3618ndash3418 3408+ pith and outer rotted

Pinus01 300 3 235 181 +C ndash 095 2901ndash272102 197 3 170 55 +C ndash 172 ndash03 177 3 155 58 +C ndash 152 ndash04 440 3 305 177 +C +B 158 2916ndash274005 265 3 252 95 +C +B 145 2901ndash2807 lobate06 360 3 275 129 +C +B 129 2610ndash248207 269 3 234 73 +C +B 236 2921ndash284908 369 3 306 192 +C +B 114 2889ndash270809 292 3 285 120 +93h +C +B 128 2907ndash2788 2715 lobate10 353 3 285 144 +54h +C ndash 102 2787ndash2644 2590+11 245 3 205 53 +53h +C ndash 177 2917ndash2865 2812+ lobate12 226 3 195 195 +C 057 ndash insect rot-hole13 242 3 215 150 +G ndash 111 2852ndash270314 232 3 210 118 +G +B 110 2908ndash279115 170 3 165 115 +C +B 072 ndash16 288 3 252 94 +21h +C +B 138 2899ndash2806 278517 190 3 170 38h+ 70 +C ndash 095 2846ndash2777 lobate18 260 3 217 94 +F ndash 105 2915ndash282219 207 3 176 142 +C ndash 109 2784ndash264320 411 3 340 265 +C ndash 079 2793ndash252921 525 3 442 261 +75h +C ndash 084 2902ndash2642 2567+22 392 3 350 179 +C +B 108 2678ndash250123 374 3 255 182 +F ndash 132 2627ndash244624 360 3 300 207 +C +B 101 2651ndash244526 330 3 300 252 +C +B 064 2814ndash2563

THQ21 has an unresolved problem after 261 with several missing ringsNo rings ndash n = measured rings n++n = innerouter unmeasured ringsPith ndash C = pith present F = 5ndash10 rings to pith G = 10 rings to pith +n = unmeasured ringsBark ndash B = bark edge presentAGR ndash Average growth rateDate span ndash measured sequence onlyEnd dates ndash with sapwood estimate for Quercus n+ denotes tpq includes unmeasured rings for Pinus n+ denotes tpq

Table 2 t-value matrix for PISYHat eld

04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 13 14 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 26

01 896 1091 340 1429 814 555 485 1137 1005 1031 702 908 ndash 688 1324 39504 1185 402 1259 727 ndash 537 802 787 978 512 912 ndash ndash 1174 ndash05 505 1150 1134 674 809 1159 966 971 770 1039 06 541 966 760 783 39507 354 311 1127 378 ndash 569 387 08 822 508 585 1569 969 1173 998 934 ndash 735 1916 46009 518 555 1510 1232 677 1143 822 ndash10 544 488 1078 1103 ndash 106411 617 526 1060 507 13 908 1109 953 983 391 867 1649 60614 1409 772 1467 1118 ndash16 967 1315 1076 17 898 ndash 813 ndash18 962 19 739 501 ndash 63420 1029 956 1136 884 190721 ndash 81022 1232 996 90323 2425 95124 741

= overlap 15 years ndash = t-values less than 300

Gretel Boswijk and Nicki J Whitehouse Pinus and Prostomis a dendrochronological and palaeoentomological study 589

Table 3 t-value table for PISYHat eld against the English Quercus mas-ter chronology and independent site chronologies

Oak chronologies t-value

English prehistoric Quercus chronology (Hillam et al 7591990 Brown and Baillie 1992)

Independent site oak chronologiesCroston Moss Lancashire (Brown and Baillie 1992) 530Wicken Sedge Fen (Brown et al 1986) 597Holme Fen (Brown et al 1986) 517Feltwell Fen (Brown et al 1986) 426Hereford and Worceseter Palaeochannel (Hillam 1997) 418

Figure 3 Bar chart showing the dated positions of the Pinus samplesincluded in PISYHat eld Note except where otherwise indicated thetree-ring sequences begin at the pith Pithbark codes as Table 1 Widebars = measured sequence Narrow bars = unmeasured rings

1mm

1mm

1mm

1mm

1mm

1mm

2900 BC 2800 BC 2700 BC2857-50

THQ01

THQ04

THQ07

THQ08

THQ09

THQ11s

B

B

B

Figure 4 Ring-width sequences from selected samples Trees 07 and 11have narrow ring bands that relate to a stress event at 2857ndash5 bc fromwhich 07 appears not to have recovered Other samples show narrow ringsin 285655 but by 2850 growth had improved The vertical scale issemi-logarithmic

became immersed into the mire Many of the wood-dependentbeetles belong to the terminal stages of the woodland as they feedoff rotting wood rather than live wood These species would havecontinued feeding and breeding within the rot-holes as long as thehabitat remained suitable Some of the aquatic and woodlandinsects probably postdate the main phase of the Pinus chronologybut it is likely that both elements were deposited at more or less

the same time This is suggested by the excellent state of thewood which indicates a very rapid submersion its associatedinsect fauna thus probably represents a more or less co-existingpopulation

The subfossil insect data were analysed by reference to a habitatclassi cation system devised for the wider palaeoentomologicalstudy of the Humberhead Levels (Whitehouse 1998) The categ-ories utilized are summarized in Table 4 but are not discussedhere Detailed ecological information was obtained from theColeopteran habitat data base BUGS (Sadler et al 1992) Thecategories are presented graphically as they provide a useful rep-resentation of the samplersquos proportions for interpretational pur-poses although it should be emphasized that they have littlemeaning in terms of proportions of habitat represented (Figure 5)Insect nomenclature follows Lucht (1987) while plant nomencla-ture follows Stace (1991)

ResultsThe rot-holes supported abundant very rare and non-British spec-ies particularly from the wood-loving genera of the weevil andcucujid families Table 4 displays the full species list togetherwith habitat categories assigned to each species The list includesfour non-British species four RDB1 species four RDB2 speciesone RDB3 species and 11 Notable B species (The Nature Con-servancy Council published British Red Data Books 2 Insects(Shirt 1987) referred to as RDB This is a comprehensive state-ment of the most threatened insects in Great Britain The Bookcontains three major categories based upon degree of threat(RDB1 endangered RDB2 vulnerable RDB3 rare) These categ-ories were added to in the various reviews including Notable Aand B species (Hyman 1992 1994)) These are either aquatics orsaproxylics (species which are dependent for some part of theirlife cycle on wood) and their present status re ects the decline oftheir associated habitats The list today would have no matchwithin forest habitats in Great Britain or Ireland since it containsspecies that no longer live in the British Isles Within subfossilinsect contexts it is comparable in importance to mid-Holocenematerial recovered from Thorne Moors (Buckland and Kenward1973 Buckland 1979 Whitehouse 1997a) and Stileway in theSomerset Levels (Girling 1985)

Quercus assemblage c 3618ndash3418 BC

The Quercus assemblage provides an insight into the nature of thepre-peat and early peat landscape The most important categoriesrepresented by the beetles in this sample include woodland dampwoodland non-acid wetland aquatic and hygrophilouscommuni-ties (Figure 5A) There is a marked absence of species associatedwith Calluna heath and acid peatland conditions Some speciesare clearly associated with the Quercus itself such as the leafminer Rhynchaenusquercus The weevil Rhyncolus ater is usuallyassociated with Pinus in Britain (Alexander 1994) but in main-land Europe it is as common in both deciduous and coniferouswood (Palm 1951 1959) Its presence in a Quercus rot-hole indi-cates that it was associated with deciduous rather than coniferouswood and suggests that this species may have been less fussyabout its host in Britain during the mid-Holocene Several of theinsect species are typical of fen and Alnus glutinosa carrs (egPterostichus nigrita P diligens Plateumaris sericea) while thedetritus of Phragmites Carex Juncus and other vegetation areindicated by several species (eg Olophrum fuscum) Permanentpools with rich littoral vegetation were almost certainly presentin the immediate vicinity as suggestedby some of the larger Dyti-scidae such as Ilybius guttiger and Agabus unguicularis Bothbeetles are often associated with mesotrophic conditions (Nilssonand Holmen 1995)

590 The Holocene 12 (2002)

Table 4 Coleoptera list from Tyrham Hall Quarry Hat eld Moors (denotes non-British species) including assigned habitat categories

Coleoptera 1 2A 2B 3 K Oak Classif

CarabidaeDyschirius globosus (Hbst) 9 1 1 2 21Trechus obtusus Er 1 1 9T rubens (F) 1 22Bembidion quadrimaculatum (L) 1 10quadripustulatum FBembidion sp 1 1 21Bradycellus rucollis (Steph) 1 10B verbasci (Duft) 1 21B harpalinus (Serv) 1 10Bradycellus sp 1 10Pterostichus strenuus (Panz) 1 9P diligens (Strm) 8 3 1 4 4 2 14P nigrita (Payk) rhaeticus Heer 1 1 1 14P nigrita (Payk) rhaeticus 1 3 14HeerP minor (Gyll) 4 3 2 14P minor (Gyll) 2 14Pterostichus spp 2 1 1 21Agonum fuliginosum (Panz) 2 1 14Aobscurum (Hbst) 2 2 9Agonum sp 1 21Dromius quadrinotatus Zenk 1 1 amp 38Carabidae gen et sp indet 1 3 UN

DytiscidaeHygrotus decoratus (Gyll) 1 27Hydroporus scalesianus Steph 5 27H gyllenhali Schdte 3 28H umbrosus (Gyll) 1 29H tristis (Payk) 83 28H pubescens (Gyll) 13 27H melanarius (Duft) 52 28Hydroporus spp 59 52 9 9 23 20 27Agabus chalconatus (Panz) 4 27A guttatus (Payk) 8 1 32A melanarius Aube 1 32A bipustulatus (L) 2 1 1 1 26A unguicularis Thoms 2 2 29Agabus spp 4 2 1 2 2 26Ilybius aenescens Thom 2 3 28Iguttiger (Gyll) 1 27Agabus Ilybius sp 1 26Graphoderus bilineatus (Deg) 1 29

HydrophilidaeOchthebius minimus (F) 2 2 1 30Ochthebius spp 3 26Limnebius aluta Bed 1 29Cercyon convexiusculus Steph 1 16Cercyon sp 1 3 35Megasternum obscurum (Marsh) 2 2 22cf Paracymus scutellaris (Rosen) 1 3 28Hydrobius fuscipes (L) 1 1 26Anacaena globulus (Payk) 3 6 1 30Anacaena sp 2 26Laccobius sp 1 26HelocharesErnochrus sp 1 26Ernochrus sp 1 26Hydrophilidae gen et sp indet 1 26

SilphidaeSilpha tristis Ill 1 35

Table 4 Continued

Coleoptera 1 2A 2B 3 K Oak Classif

Silpha sp 1 UN

ScydmaenidaeNeuraphes elongatulus (Mull) 2 09Scydmaenidae gen et sp indet 1 UN

ClambidaeClambus sp 1 1 22

PtiliidaeAcrotrichis sp 1 35

StaphylinidaeMegathrusProteinus sp 1 1 35Olophrum piceum (Gyll) 2 2 2 1 16O fuscum (Grav) 1 2 16Eucnecosum brachypterum (Grav) 2 20Acidota crenata (F) 2 20Lesteva punctata Er 1 24L punctata Er 1 24Bledius sp 2 1 24Carpelimus sp 1 1 21Anotylus sp 1 35Stenus comma LeC 1 22Stenus spp 7 5 2 1 4 2 22Scopaeus sulcicollis (Steph) 1 21gracilis (Sperk)Lathrobium rupenne Gyll 5 1 2 20L terminatum Grav 1 1 20L fulvipenne (Grav) 1 2 22L brunnipes (F) 1 3 22Lathrobium spp 5 8 1 1 1 3 21Xantholinus linearis (Ol) 1 10X longiventris Heer 1 2 35Philonthus spp 2 UNGabrius sp 1 UNStaphylinus brunnipes F 1 22Staphylinus sp 1 UNQuedius sp 3 UNMycetoporus sp 1 1 UNAleocharinae genet sp indet 2 1 1 1 2 35Staphylinidae gen et sp indet 2 UN

PselaphidaeBryaxis bulbifer (Reich) 2 1 1 20B curtisi (Leach) 8 1 09Bryaxis sp 2 22Brachygluta fossulata (Reich) 1 1 22Pselaphus heisei (Hbst) 1 20Pselaphidae gen et sp indet 1 UN

ElateridaeAmpedus rupennis Steph 1 05Ampedus sp 1 03Agriotes sputator (L) 1 13Hypnoides riparius (F) 1 21Elateridae gen et sp indet 2 UN

ScirtidaeMicrocara testacea (L) 2 09Cypon padi (L) 8 30Cyphon spp 16 20 3 1 1 3 21

Gretel Boswijk and Nicki J Whitehouse Pinus and Prostomis a dendrochronological and palaeoentomological study 591

Table 4 Continued

1 2A 2B 3 K Oak Classif

Byrridae Curimposis nigrita (Palm) 1 18

OstomidaeOstoma ferrugineum (L) 1 04

RhizophagidaeRhizophagus ferrugineus (Payk) 1 06

CucujidaeProstomis mandibularis (F) 1 05

LathiididaeLathridius minutus (L) pseudomi- 1 36nutus StrandL anthracinus Mann 2 36Cortinicara gibbosa (Hbst) 1 1 36Corticarina sp 1 36Corticariinae indet 1 1 36Lathridiidae gen et sp indet 1 1 36

ColydiidaeBitoma crenata (F) 1 05 amp

38Cerylon histeroides (F) 1 06Colydiidae gen et sp indet 1 06

AnobidaeGrynobius planus (F) 1 06

PtinidaePtinus clavipes Panz 1 37

ScarabaeidaeAphodius sphacelatus (Panz) 1 35

ChrysomelidaePlateumaris sericea (L) 2 14Plateumaris sericea (L) 1 14P discolor (Panz) 5 19P discolor (Panz) sericea (L) 4 5 5 2 14Donaciinae indet 1 1 14Chaetocnema concinna (Marsh) 1 13C hortensis (Fourc ) 1 13Chrysomelidae Gen et Sp indet 1 UN

ScolytidaeLeperisinus varius (F) 1 02Dryocoetinus villosus (F) 2 05 amp

38Pityophthorus lichtensteini (Rantz) 1 04PityophthorusPityogenes sp 1 03Xyleborus saxeseni (Ratz) 1 1 03Ipinidae gen et sp indet 1 03Scolytidae gen et sp indet 2 1 03

CurculionidaeApion spp 1 4 13Phyllobius sp 1 UNSitona sp 1 13Dryophthorus corticalis (Payk) 21 2 06Rhyncolus elongatus (Gyll) 31 1 04

R ater (L) 10 1 04R cf ater (L) 1 04R punctulatus Bohe 1 06R sculpturatus Walt 29 04Phloeophagus lignarius (Marsh) 1 05Cossinine gen et sp indet 1 05

Table 4 Continued

Coleoptera 1 2A 2B 3 K Oak Classif

Acalles roboris Curt 1 02A ptinoides (Marsh) 1 11Micrelus ericae (Gyll) 6 1 4 10Ceutorhynchus sp 1 13Ceutorhynchus pallidactylus Marsh 1 13Anthonomus rubi (Hbst) 1 07Rhynchaenus quercus (L) 1 1 02R rusci (Hbst) 1 11Rhynchaenus spp 3 1 03Curculionidae gen et sp indet 1 1 UN

Coleoptera gen et sp indet 1 UN

Total Coleoptera individuals 482 174 38 44 85 54Total Coleoptera species 102 64 26 28 44 27

Classi cation Habitat categories (after Whitehouse 1998)Woodlandtrees (1) pinewoodsheaths (2) deciduous woodland (3)woodlands (all types) (4) dead and decaying tree habitats (coniferous)(5) dead and decaying tree habitats (deciduous) (6) dead and decayingtree habitats (all types) (7) woodland owersherbs (8) woodlandfungiand mouldy plant debris Damp woodland (9) damp woodland (egAlnus carr) Heath and grassland (10) sandy heathCalluna (11)Heathwoodlands (12) xerophilous (13) grassland herbs and owersNon-acid wetlands (14) non-acidic bogswetlands (15) fensreeds andsedges (16) non-acidplant debris (17) reedsbrackish water Acid wet-lands (18) acid bogs (19) acid bogsEriophorum and Sphagnum (20)bogsplant debris Hygrophilous (wet-loving) (21) hygrophilous (22)hygrophilousplant debris (23) water marginsriverbanks (24) watermarginsplants and mud (25) wet locationsherbs and marsh plantsAquatics (26) aquaticgeneralists (27) aquaticsbogs (28) aquaticacidbog (29) aquaticnon-acidic bog (30) aquaticvegetation and detritus-rich(31) aquaticstagnant and sometimes brackish water (32) aquaticslow-moving water (33) aquaticrunning water Decaying debris (34)exclusively dung (35) decaying animal and plant debris (36) fungiplantdebris (37) fungiwoodplant debris Others (38) re indicators (UN)unclassi ed

Pinus assemblages 2921ndash2445 BC

The Pinus samples consist of two major faunal components taxarelated to wood habitats and aquatics Figure 5B provides an over-view of the habitats represented

The range of wood-loving taxa recorded from the site isrepresentative of mixed woodland in varying states of decay Inaddition to Pinus the insects indicate that Betula Quercus Frax-inus and possibly Fagus grew locally The continued presence ofQuercus is suggested by its leaf miner Rhynchaenus quercus Thenon-British ancient woodland relic species (Urwaldrelikt) Pro-stomis mandibularis is often found in decayed red rotted Quercustypically in areas of primary woodland (Horion 1960) althoughsingly it can be found in decaying Pinus (Koch 1992) which waspresumably its habitat in this case The non-British lsquoUrwaldreliktrsquoRhyncolus punctulatus is found in hollow deciduous trees oftenin Quercus as well as in conifers (Reitter 1916 Palm 1959) Itis often associated in dry wood with the weevil Phloeophaguslignarius (Palm 1959) which was recovered from the same sam-ple Fraxinus excelsior is the host of the bark beetle Leperisinusvarius indicating the presence of this tree within the vicinity Therare RDB2 elaterid Ampedus ru pennis is commonly found inmouldy deciduous wood predominantly on Fagus (Horion 1953Palm 1959) although it can also live on Betula a tree that wascertainly represented within the woodland as its leaf miner Rhyn-chaenus rusci and its macrofossils suggest

Dryophthorus corticalis an ancient woodland inhabitant wasfeeding on the Pinus in large numbers The quantities recovered

592 The Holocene 12 (2002)

Figure 5 Proportions of wood and other habitat Coleoptera indicatorcategories (A) Tyrham Hall Quarry Quercus sample (B) Tyrham HallQuarry Pinus samples

from one of the rot-holes and their intact state of preservationsuggests they were feeding and breeding within the rot-hole InEngland this endangered species is usually only associated withQuercus (Donisthorpe 1939 Hyman 1992) although it is fre-quently recorded in coniferous wood on the Continent often inhigh numbers in both modern and subfossil contexts (Palm 1959Koponen and Nuorteva 1973) Again the recovery of this specieswithin a Pinus context would suggest a change in its preferredhost in Britain more recently As a subfossil this species is closelyassociated with the genus Rhyncolus (Whitehouse 1997a) a con-nection noted within the European literature (Palm 1959) Thisassociation is nowhere clearer than at Tyrham where other mem-bers of this genus including the non-British R elongatus and Rsculpturatus as well as the British R ater were present appear-ing to have been attracted to the rotting Pinus in great numbersMost of the species described above are those that attack woodduring the early stages of decomposition and there is no evidenceof infestation by insect pests among the wood-associate beetlesthat could have played a role in the decline of the woodland

A small group of species indicates damp woodland conditionssuch as Agonum obscurum and Trechus obtusus while Pteros-tichus strenuus is found in the drier parts of Alnus swamps andfen woodland (Lindroth 1945) There are also several speciescommonly found in Calluna and heathland including signi cantnumbers of the heather feeder Micrelus ericae and other typicalbeetles (eg Bradycellus ru collis B harpalinus Xantholinuslinearis) As the woodland declined aquatic and peatland assem-blages of beetles became incorporated within the rot-holespresumably as the trees became buried within the mire and itspools Species identi ed are those predominantly associated withwet mesotrophic and ombrotrophic conditions ndash members of thegenus Pterostichus (P nigritarhaeticus P minor P diligens) inaddition to Agonum fuliginosum are typical of mesotrophic peat-lands The recovery of one of the Humberhead Peatlandsrsquo endang-ered (RDB1) species the byrrhid Curimopsis nigrita a lowland

peatland specialist is notable as it illustrates that the particularcharacter of these lowland raised mires formed about 4000 yearsago This mixture of eutrophic and ombrotrophic conditions isalso evident among aquatic vegetation associates with the pres-ence of species such as Plateumaris sericea and P discolor ndash theformer is typical of eutrophic fens and the latter of ombrotrophicconditions living on Eriophorum Sphagnum and Carex species(Bullock 1993) The aquatic beetles also indicate a varied rangeof habitats the RDB3 fen-loving hydrophilid Limnebius aluta andRDB1 Graphoderus bilineatus can be found in deep ponds andlakes generally with dense marginal vegetation (Shirt 1987)Hydroporus scalesianus H pubescens and Agabus chalconatusall indicate vegetation-rich standing fen pools with Sphagnum(Shirt 1987 Koch 1989) There are however also many acid-loving aquatics although most originate from one sample (1)including Hydroporus tristis H melanarius and H gyllenhaliThe presence of larger water beetles indicates pools of some sizeincluding several species often associated with slowly movingwater such as Agabus guttatus and A melanarius (Friday 1988Koch 1989)

Discussion

The dendrochronological and subfossil insect evidence is indica-tive of an early Quercus-fen woodland community with a dateof 3618ndash3418 bc for the single incomplete Quercus The remainsof other undated Quercus elsewhere on Hat eld suggests thatthere may have been contemporary trees The tree overlappedtemporally with the Quercus woodland on Thorne Moors (3777ndash3017 bc) probably the relic of widespread forest growing acrossthe Humberhead Levels (Boswijk 1998 2002) Eutrophic andmesotrophic fen conditions are indicated by the insect faunawhich was probably living contemporaneously with the Quercusor soon after its demise The aquatic beetles indicate that theQuercus was submerged into a permanent deep pool perhaps anindication of a rising water table

Between 2921 and 2445 bc sandy Pinus-heath woodland grewon the western edge of Hat eld Moor By this time black well-humi ed peat had started developing elsewhere on the northernside of Hat eld well-humi ed peat had began to accumulate c3350ndash3030 cal bc at HAT 3 (4480 6 45 BP SRR-6119)(Whitehouse 1998) and on the eastern side c 3090ndash2890 cal bc(HAT 2 4335 6 75 BP CAR-254) and 2900ndash2620 cal bc (HAT1 4180 6 70 BP CAR-168) (Smith 1985 Figure 2) The rangeand variety of insect species recovered suggest that the woodlandcomprised a mix of tree species in addition to Pinus includingQuercus Betula and Alnus with Fraxinus and Fagus furthera eld This mix of trees is also indicated by the palynologicaldata from the centre of the Moor (HAT 1 Smith 1985) Themixed age structure of the Tyrham Pinus woodland with ongoingdie-back and periodic regeneration of new trees over 400 yearssuggests that the woodland was probably reasonably openenabling seedlings to become established in clearings caused bydead standing trees or fallen trees The understorey supportedinsect species typical of Calluna heathland such as those associa-ted with moss raw humus and Calluna interspersed with deepand shallow pools and slow-moving water The dominant Callunaunderstorey would have been suitable for seedling establishmentMcVean (1963) found that regeneration of Pinus in Scotland wassuccessful in woodland classed as Pinetum-Vaccineum-Callune-tum where there was a thick moss and raw humus layer intowhich the seedlings could strike and develop the essentialmychorrhizal fungal associations The presence of beetle feederson fungi indicates that there was a supply of rotting wood to sup-port such a community Thus the woodland would have includeddecaying and dead wood as well as mature trees and new growth

Gretel Boswijk and Nicki J Whitehouse Pinus and Prostomis a dendrochronological and palaeoentomological study 593

The tree-ring evidence indicates that the woodland declinedslowly as trophic conditions in the area gradually changed Thereis an increasing representation of a mesotrophic invertebrate com-munity although signi cant events accelerating the transitionfrom eutrophic to mesotrophic conditions may also have occurredSome aquatic subfossil beetle indicate moving-water and deeper-water environments and may explain a period of severe stressexperienced by some Pinus in 2857ndash5 bc perhaps representing anepisode of groundwater ooding created by a rising water tableIt is relevant to note that Smith (1985) in his analysis of plantmacrofossils from the eastern side of Hat eld Moors identi edan initial episode of ooding sometime around 2900ndash2620 calbc (4180 6 70 BP CAR-168) and 3090ndash2890 cal bc (4335 675 BP CAR-254) This is indicated by the presence of Sphagnumcuspidatum within pro les at HAT 1 and 2 (Figure 2)

Over time as ground conditions become increasingly water-logged and the nature of understorey vegetation altered thegrowth of Pinus seedlings would have been inhibited In additionstanding trees may have become unstable In mature form Pinushas a tall branchless trunk spreading crown and predominantlyshallow root system (Humphries et al 1992) They may be proneto becoming top-heavy and narrow ring episodes coinciding withthe onset of lobate growth suggest that many trees slumped butcontinued growing at an angle It is possible that these trees grewnear or alongside a pool or watercourse as the good preservationof the Pinus as well as the abundant water beetles suggests thatwhen they fell they were either submerged or rapidly buried inanaerobic deposits Many of the trees although without brancheswere intact between the trunk and root This contrasts with otherpeatland sites from which Pinus have been recovered where onlythe root system and small amount of trunk often have remainedThe slow growth of blanket peat in Rannoch Moor Scotlandresulted in many of the trees rotting in situ (Bridge et al 1990)while at Lindow Bog and White Moss Cheshire few trunks wererecovered though the root system and a small area of lower trunkwere well preserved in the peat (Lageard 1992)

The woodland at Tyrham contrasts with the contemporaneousPinus woodland growing on Thorne Moors (2916ndash2475 bc Bos-wijk 1998 2002) At the time when the PISYHat eld chron-ology begins a few dispersed pioneer trees became establishedpredominantly on the western side of Thorne Moors Tree densityincreased dramatically from 2744 bc onwards as an even-agedstand grew between the pioneers The Thorne Pinus tended todisplay rapid growth particularly in the early years suggestingthat the seedlings were established in an open environment By2570 bc the cohort had largely died back most probably inresponse to the development of wetter conditions (Boswijk 19982002) There was only limited regeneration after this date Thedecline of the Thorne woodland was swifter than at Tyrham asPISYHat eld extends for a further 100 years after the demise ofthe Thorne Pinus This suggests that the Tyrham trees did notrespond as quickly to changing conditions as those on ThorneMoors although it is important to note that the woodland wasalready in decline at this time It is likely that local edaphic con-ditions played a part in delaying the reponse of trees Eventuallya much wetter environment as indicated by the high proportion ofaquatic beetle species recovered replaced the Tyrham woodland

The structure of PISYHat eld is similar to the contemporarywoodland growing on White Moss Cheshire (Lageard et al1999) as well as the oating Pinus chronology from GlashburnIreland dated to 2500ndash2000 cal bc (McNally and Doyle 1984)The Tyrham trees were visibly rooted into the sandy substrate(ie an example of pre- and early-mire landscape) whereas theIrish and Cheshire Pinus were examples of mire-Pinus woodlandsgrowing on peat The Glashburn trees were separated from theunderlying lake marl deposit by approximately 175 m of peat(McNally and Doyle 1984) At White Moss the dendrochronol-

ogically dated Pinus were growing on peat that was on average139 m thick over the sandy substrate (Lageard et al 1999) Thusthe growth environment of these trees and their westerlylocations may have made them sensitive to shifts towards wetterconditions in their host bogs Lageard et al (1999) suggested thatthe decline of the White Moss trees supports the premise of astaged retreat in reponse to a climatic shift to wetter conditionsat about 2500 bc which had signi cant effect on the survival ofmire Pinus populations across the British Isles The end dates of2569 bc for Garry Bog Pinus (Pilcher et al 1995) and 2559 bcfor White Moss (Lageard et al 1999) as well as the declineof PISYThorne by 2475 bc (Boswijk 1998 2002) andPISYHat eld in 2445 bc may also be indicative of such a changein climate On Thorne Moors however within 200 years Pinusrecolonized the mire and was present episodically for almost1000 years until at least 1489 bc (Boswijk 1998 2002) suggest-ing that in eastern England at least periods unfavourableto Pinusgrowth were short-lived The subfossil invertebrate record fromother sites on Hat eld Moors would corroborate this idea(Whitehouse 1998) and Hat eld still supports an important mod-ern pine fauna (Skidmore 2001)

Buckland (1979) Buckland and Sadler (1985) Dinnin (1997)and more recently Buckland and Smith (2002) and Whitehouseet al (2001) have discussed the probable factors in uencing peatdevelopment of the wetlands in the Humberhead Levels Ratherthan seeing a shift to wetter climate as the primary cause of boggenesis and development and the consequent decline of theQuercus and Pinus woodlands the models stress the in uence ofa rising water table associated with an increase in runoff causedby forest clearance activities in the upriver catchments leading towidespread paludi cation In addition the general trend in sea-level rise around this time (Gaunt and Tooley 1974 Dinnin andLillie 1995 Long et al 1998) could have caused a backing-up offreshwater runoff from rivers which run into the Humber estuarycausing regional freshwater ooding as well as affecting the lev-els of the underlying water table During these periods of marinetransgression marine conditions penetrated far into the Humberestuary and its tributary valleys (Long et al 1998) Howeverthere is no palaeoecological or stratigraphic evidence for thepresence of any saline in uences indicating marine or estuarineconditions as far inland as the Humberhead Levels (Buckland1979 Buckland and Sadler 1985 Smith 1985 Whitehouse1998) This is despite the base of the peat deposits at ThorneMoors now lying over 4 m below high water at Goole

The importance of these pre- and early-mire woodlands inestablishing the faunal communities of the subsequent raised mireis clearly demonstrated by the analyses of subfossil insects fromthe basal forest deposits of Tyrham Hall Quarry as well as else-where on Thorne and Hat eld Moors There are many faunalelements from the Tyrham assemblage and other sites on Hat eldMoors that still appear on the modern Coleopteran list such asthe rare peatland specialist C nigrita However among the extinctspecies recovered many are today restricted to isolated enclaveswithin mature forests of mainland Europe The larvae or pupaeof many saproxylic invertebrates typically have long periods ofdevelopment sometimes over several years hidden within decay-ing wood of suitable quality and age Many often have shortimaginal (adult) lifespans often inhabiting only a proportion ofpotentially suitable trees representing a fraction of the total treepopulation of most forests (Warren and Key 1991 McLean andSpeight 1993) The destruction of undisturbed forest and in parti-cular the disappearance and lack of continuity of dead wood habi-tats decline in Pinus and associated re frequency and possiblythe subtle interplay of climatic change have all contributed to thenear or total loss of these species (eg Buckland 1979 Bucklandand Dinnin 1997 Whitehouse 1997b 2000 Whitehouse et al1997 Dinnin and Sadler 1999) The recovery of these species in

594 The Holocene 12 (2002)

the Tyrham and Hat eld deposits is therefore highly signi cantas they suggest a former abundance of these extinct species high-light the importance of woodland and dead wood habitats andindicate that only a portion of the former faunal communityremains to recolonize restored mires

Conclusion

Dendrochronologicaland palaeoentomologicalanalyses of subfos-sil Quercus and Pinus have provided new data concerning a mid-Holocene woodland A single Quercus was dated to 3618ndash3418bc and a 477-year Pinus chronology was established and absol-utely dated to 2921ndash2445 bc by reference to the English Quercusmaster curve The subfossil entomological fauna indicate mixedwoodland growing in the area although Pinus became the domi-nant taxon with an understorey characterized by Calluna andsedges Over the period of the Pinus chronology the woodlandbegan to die back in response to rising groundwater and changingtrophic levels It is clear that at Tyrham at least mire develop-ment on this site caused tree death rather than mire spreading asa result of the death of trees the insect samples from the Quercusrot-hole indicate the onset of fen development during this earlystage A rise in aquatic insect species and the good preservationof the trees would suggest that the area became increasingly wetand ombrotrophicSome Pinus may have fallen into pools butpeat also appears to have developed relatively quickly preservingthe woodland at the base of the bog The decline in the woodlandappears to be part of a signi cant demise of bog Pinus alsorecorded in sites from western England and Ireland at about 2500bc However the presence of Pinus on Thorne Moors until atleast 1489 bc suggests that in eastern England at least periodsunfavourable to Pinus growth were short-lived Moreover ongo-ing populations of Pinus and its associated invertebrates continuedto thrive in remote locations such as the raised mires of theHumberhead Levels potentially into the post-mediaeval period

The fossil insect evidence clearly shows that the faunal originsof the ombrotrophic mire can be traced back to events whichoccurred c 4000 years ago in a mixed Pinus-mire environmentEffectively time and history of a site appear to have a consider-able in uence on the faunal characteristics of our mires todayThis suggests that recreating raised mire with the lsquocorrectrsquo(climax) vegetation the goal of present management practicesmay not allow the longer-term restoration of faunal communitiessince the faunal characteristics of these sites were generated 4000years ago ndash something which cannot be restored or regeneratedover a short timespan The end result of any restoration work onthese sites may be a visually satisfying but a faunally depletedlandscape

Acknowledgements

Tree-ring analysis of the pines from Hat eld Moors was carriedout as a part of a PhD research project carried out by GB onThorne Moors funded by the University of Shef eld Palaeoento-mological analysis was conducted by NJW as part of a wider PhDstudy of Hat eld Moors and the Humberhead Levels funded bythe Hossein Farmy Fund (University of Shef eld) The authorswould like to thank Paul Buckland for bringing the site to theirattention and Tilcon plc for allowing access to the quarry BothPaul Buckland and Kevin Edwards are thanked for all their helpin this project and continued support and interest NERCRadiocarbon Steering Committee (Allocations 6411295 and6590896) granted 38 new dates for the Humberhead Levels aspart of these studies

GB especially thanks J Hillam C Groves and I Tyers of theShef eld Dendrochronology Laboratory for training discussionsand access to the Shef eld tree-ring data bank I Tyers cut thesamples at Tyrham Hall Quarry D Brown and J Lageard pro-vided advice NJW thanks T Roper and E Panagiotapopulou forhelp with eldwork and P Buckland C Johnson P Skidmoreand P Wagner for assistance with identi cations The authorswould also like to thank PC Buckland KJ Edwards D Hendonand V Hall for commenting on previous drafts of this paper Thepaper has also bene ted from comments by K Bennett and AHaggard

References

Alexander KNA 1994 An annotated checklist of British lignicolousand saproxylic invertebrates Cirencester National Trust EstatesAdvisorsrsquo Of ce (draft)Anderson DE Binney HA and Smith MA 1998 Evidence forabrupt climatic change in northern Scotland between 3900 and 3500 calen-dar years BP The Holocene 8 97ndash103Baillie MGL 1982 Tree-ring dating and archaeology LondonCroom HelmBaillie MGL and Pilcher JR 1973 A simple cross-dating programfor tree-ring research Tree-ring Bulletin 33 7ndash14Bateman MD 1995 Thermoluminescence dating of the British cover-sand deposits Quaternary Science Reviews 14 791ndash98Bateman MD Murton JB and Crowe W 2000 Late Devensian andHolocene depositional environments associated with the coversand aroundCaistor north Lincolnshire UK Boreas 29 1ndash15Bennett KD 1984 The post-glacial history of Pinus sylvestris in theBritish Isles Quaternary Science Reviews 3 133ndash55mdashmdash 1989 A provisional map of forest types for the British Isles 5000years ago Journal of Quaternary Science 4 141ndash44mdashmdash 1995 Post-glacial dynamics of pine (Pinus sylvestris) and pinewoodsin Scotland In Aldhous JR editor Our pinewood heritage Proceedingsof a Conference at Culloden Academy Inverness Forestry Commission22ndash39Birks HJB 1989 Holocene isochrone maps and patterns of tree-spread-ing in the British Isles Journal of Biogeography 16 503ndash40Blackford JJ Edwards KJ Dugmore AJ Cook GT andBuckland PC 1992 Icelandic volcanic ash and the mid-HoloceneScots pine (Pinus sylvestris) decline in northern Scotland The Holo-cene 2 260ndash65Boswijk G 1998 A dendrochronological study of oak and pine fromthe Humberhead Levels eastern England Unpublished PhD thesisUniversity of Shef eld (available from author)mdashmdash 2002 The buried forest of Thorne Moors Thorne and Hat eldPapers 6 in pressBradshaw R 1993 Forest response to Holocene climatic changeequilibrium or non-equilibrium In Chambers FM editor Climatechange and human impact on the landscape London Chapman andHall 57ndash65Bridge MC Haggart BA and Lowe JJ 1990 The history andpalaeoclimatic signi cance of subfossil remains of Pinus sylvestris inBlanket peats from Scotland Journal of Ecology 78 77ndash99Brown DM and Baillie MGL 1992 Construction and dating of a5000 year English bog oak tree-ring chronology In Bartholin TS Ber-glund BE Eckstein D and Schweingruber FH editors Tree-rings andenvironment Proceedings of the International Dendrochronology Sym-posium Lundqua Report 34 Lund University 72ndash5Brown DM Munro MAR Baillie MGL and Pilcher JR 1986Dendrochronology ndash the absolute Irish standard Radiocarbon 28(2A)279ndash83Buckland PC 1979 Thorne Moors a palaeoecological study of aBronze Age site a contribution to the history of the British insect faunaDepartment of Geography University of Birmingham Occasional Publi-cation Number 8Buckland PC and Dinnin M 1997 The rise and fall of a wetlandhabitat recent palaeoecological research on Thorne and Hat eld MoorsThorne and Hat eld Moors Papers 4 1ndash18

Gretel Boswijk and Nicki J Whitehouse Pinus and Prostomis a dendrochronological and palaeoentomological study 595

Buckland PC and Kenward HK 1973 Thorne Moor a palaeo-ecological study of a Bronze Age site Nature 241 405ndash7Buckland PC and Sadler J 1985 The nature of late Flandrian alluvi-ation in the Humberhead Levels East Midland Geographer 8 239ndash51Buckland PC and Smith B 2002 Equi nality conservation and theorigins of lowland raised mires The case of Thorne and Hat eld MoorsThorne and Hat eld Moors Papers 6 in pressBullock JA 1993 Host plants of British beetles a list of recordedassociations Amateur Entomologist 11a 1ndash24Chambers FM Lageard JGL Boswijk G Thomas PAEdwards KJ and Hillam J 1997 Dating prehistoric bog- re in north-ern England to calendar years by long-distance cross-matching of pinechronologies Journal of Quaternary Science 12 253ndash56Coope GR and Osborne P 1968 Report on the Coleopterous faunaof the Roman well at Barnsley Park Gloucestershire Transactions of theBristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 86 84ndash87Dinnin MH 1997 The palaeoenvironmental survey of West Thorneand Hat eld In Van de Noort R and Ellis S editors Wetland heritage ofthe Humberhead Levels Humber Wetlands Project (for English Heritage)University of Hull 157ndash90Dinnin MH and Lillie M 1995 The palaeoenvironmental survey ofSouthern Holderness and evidence for sea-level change In Van de NoortR and Ellis S editors Wetland heritage of Holderness an archaeolog-ical survey Humber Wetlands Project (for English Heritage) Universityof Hull 87ndash120Dinnin MH and Sadler JP 1999 10000 years of change the Holo-cene entomofauna of the British Isles Quaternary Proceedings 7 545ndash62Donisthorpe H St JK 1939 The Coleoptera of Windsor ForestLondon published privatelyErdtman G 1928 Studies in the post-arctic history of the forests ofnorth-western Europe I Investigations in the British Isles Geol ForenStockh Forh 50 123Friday LE 1988 A key to the adults of British water beetles FieldStudies 7 1ndash151Gaunt GD 1994 Geology of the country around Goole Doncaster andthe Isle of Axholme memoir for one-inch sheets 79 and 88 (England andWales) British Geological Survey London HMSOGaunt GD and Tooley M 1974 Evidence for Flandrian sea-levelchanges in the Humber estuary and adjacent areas Bulletin of the Geologi-cal Survey of Great Britain 48 25ndash41Gear AJ and Huntley B 1991 Rapid changes in the range limits ofScots pine 4000 years ago Science 251 544ndash47Girling MA 1985 An lsquoold forestrsquo beetle fauna from a Neolithic andBronze Age peat deposit at Stileway Somerset Levels Papers 11 80ndash85Godwin H and Deacon J 1974 Flandrian history of oak in the BritishIsles In Morris MG and Perring FH The British oak London EWBotanical Society of the British Isles EW Cassey 51ndash61Hall VA Pilcher JR and McCormac FG 1994 Icelandic volcanicash and the mid-Holocene Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) decline in the northof Ireland no correlation The Holocene 4 79ndash83Hillam J 1997 Dendrochronology In Nayling N and Caseldine AExcavations at Caldicot Gwent Bronze Age palaeochannels in the lowerNedern valley CBA Research Report 108 187ndash94Hillam J Groves CM Brown DM Baillie MGL ColesJM and Coles BJ 1990 Dendrochronology of the EnglishNeolithic Antiquity 64(243) 210ndash20Hillam J Morgan RA and Tyers I 1987 Sapwood estimates andthe dating of short ring sequences In Ward RG Applications of tree-ring studies BAR Int Ser 333 165ndash85Horion A 1953 Faunistik der Mitteleuropaischen Kafer 3 Munichmdashmdash 1960 Faunistik der Mitteleuropaischen Kafer 7 ClavicorniaSphaeritidaendashPhalacridae Uberlingen-BodenseeHumphries CJ Press JR and Sutton DA 1992 Trees of Britainand Europe London HamlynHyman PS 1992 A review of the scarce and threatened Coleoptera ofGreat Britain Part 1 (revised and updated by MS Parsons) PeterboroughUK Joint Nature Conservation Committeemdashmdash 1994 A review of the scarce and threatened Coleoptera of GreatBritain Part 2 (revised and updated by MS Parsons) Peterborough UKJoint Nature Conservation CommitteeKoch K 1989 Die Kafer Mitteleuropas Okologie 1 and 2 KrefeldGoecke and Evers

mdashmdash 1992 Die Kafer Mitteleuropas Okologie 3 Krefeld Goecke andEversKoponen M and Nuorteva M 1973 Uber subfossile Waldinsekten ausdem Moor Piilonsuo in Sud nnland Acta Entomologica Fennica 29 1ndash84Lageard JGA 1992 Vegetational history and palaeoforest reconstruc-tion at White Moss Unpublished PhD thesis Keele University (availablefrom author)Lageard JGA and Chambers FM 1993 The palaeoecological sig-ni cance of a new subfossil oak (Quercus sp) chronology from MorrisBridge Shropshire UK Dendrochronologia 11 25ndash33Lageard JGA Chambers FM and Thomas PA 1999 Climaticsigni cance of the marginalization of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L) c2500 bc at White Moss south Cheshire UK The Holocene 9 321ndash31Lindroth CH 1945 Die Fennoskandischen Carabidae IndashIII GoteborgsK Vetensk o VitterhSamh Handl(6) B 4 GoteborgLong AJ Innes JB Kirby JR Llyod JM Rutherford MMShennan I and Tooley MJ 1998 Holocene sea-level change and coas-tal evolution in the Humber estuary an assessment of rapid coastal changeThe Holocene 8 229ndash47Lucht WH 1987 Die Kafer Mitteleuropas Katalog Krefeld Goeckeand EversMcLean IFG and Speight MCD 1993 Saproxylic invertebrates ndashthe European context In Kirby KJ and Drake CM editors Dead woodmatters the ecology and conservation of saproxylic invertebrates in Bri-tain Peterborough English Nature 7 21ndash32McNally A and Doyle GJ 1984 A study of sub-fossil pine layers ina raised bog complex in the Irish Midlands ndash I Palaeowoodland extentand dynamics Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 84b 57ndash70McVean DN 1963 Growth and mineral nutrition of Scots pine seedlingson some common peat types Journal of Ecology 5 657ndash70Munro MAR 1984 An improved algorithm for cross-dating tree-ringseries Tree-ring Bulletin 44 17ndash27Nilsson AN and Holmen M 1995 The aquatic Adephaga (Coleoptera)of Fennoscandia and Denmark II Dytiscidae Fauna EntomologicaScandinavica 32 Leidden EJ BrillPalm T 1951 Die Holz und Rindenkafer der nordschwedischenLaubbaume Meddelelser Statens Skogsfors-instituten 40 no 2mdashmdash 1959 Die Holz und Rindenkafer der sud- und mittelschwedischenLaubbaume Opusc Ent Suppl 16Pilcher JR 1990 Ecology of sub-fossil oak woods on peat In DoyleGJ editor Ecology and conservation of Irish peatlands Dublin RoyalIrish Academy 41ndash7Pilcher JR Baillie MGL Brown DM McCormac FGMacSweeney PB and McLawrence AS 1995 Dendrochronology ofsub-fossil pine in the north of Ireland Journal of Ecology 83 665ndash71Reitter E 1916 Fauna Germanica Die Kafer des Deutchen ReichesStuttgartRodwell JS and Cooper EA 1995 Scottish pinewoods in a Europeancontext In Aldhous R editor Our pinewood heritage Proceedings of aconference at Culloden Academy Inverness Forestry Commission 4ndash21Roper T 1993 A lsquowastersquo of resources the origins growth and declineof Thorne Moors a palaeoentomological study MSc dissertation Univer-sity of Shef eldmdashmdash 1996 Fossil insect evidence for the development of raised mire atThorne Moors near Doncaster Biodiversity and Conservation 5 503ndash21Sadler JS Buckland PC and Raines MJ 1992 BUGS an entomo-logical database Antenna 16(4) 158ndash66Shirt DB 1987 British Red Data Books 2 Insects Peterborough Nat-ure Conservancy CouncilSkidmore P 2001 A provisional list of the insects of Hat eld MoorsDoncaster Thorne and Hat eld Moors Conservation ForumSmith AG 1958 Post-glacial deposits in south Yorkshire and northLincolnshire New Phytologist 57 19ndash49Smith BM 1985 A palaeoecological study of raised mires in the Humb-erhead Levels PhD thesis University of Walesmdashmdash 2002 A palaeoecological study of raised mires in the HumberheadLevels British Archaeological Reports Series No 336 and Thorne andHat eld Moors Monograph No 1Stace C 1991 New ora of the British Isles Cambridge CambridgeUniversity PressTyers IG 1999 Dendro for Windows program guide ARCUS Report500

596 The Holocene 12 (2002)

Warren MS and Key RS 1991 Woodlands past present and poten-tial for insects In Collins NM and Thomas JA editors The conser-vation of insects and their habitats 15th Symposium of the Royal Entomo-logical Society of London 14ndash15 September 1989 London AcademicPress 155ndash211Whitehouse NJ 1993 A mid-Holocene forested site from ThorneMoors the fossil insect evidence Unpublished MSc thesis University ofShef eld (available from author)mdashmdash 1997a Silent witnesses an lsquoUrwaldrsquo fossil insect assemblage fromThorne Moors Thorne and Hat eld Moors Papers 4 19ndash54mdashmdash 1997b Insect faunas associated with Pinus sylvestris L from themid-Holocene of the Humberhead Levels Yorkshire UK In AshworthAC Buckland PC Sadler JP editors Studies in Quaternary ento-mology an inordinate fondness for insects Quaternary Proceedings 5293ndash303mdashmdash 1998 The evolution of the Holocene wetland landscape of the Humb-erhead Levels from a fossil insect perspective Unpublished PhD thesisUniversity of Shef eld (available from author)

mdashmdash 2000 Forest res and insects palaeoentomological research from asub-fossil burnt forest Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecol-ogy 164 231ndash46Whitehouse NJW Boswijk G and Buckland PC 1997 Peatlandspast present and future some comments from the fossil record In ParkynL Stoneman RE and Ingram HAP editors Conserving PeatlandsWallingford CAP International 54ndash63Whitehouse NJ Buckland PC Boswijk G and Smith BM 2001The ontogeny of Thorne and Hat eld Moors In Bateman MD BucklandPC Frederick CD and Whitehouse NJ editors The Quaternary ofEast Yorkshire and North Lincolnshire Field guide London QuaternaryResearch Association 195ndash98Zetterberg P Eronen M and Lindholm M 1996 Construction ofa 7500 year tree-ring record for Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L) innorthern Fennoscandia and its application to growth variation andpalaeoclimatic studies In Spiecker H Mielikainen K Kohl M andSkovsgaard JP editors Growth trends in European forests EuropeanInstitute Research Report 5 Berlin Springer-Verlag 7ndash18

586 The Holocene 12 (2002)

Quercus woodland grows predominantly on poor infertile andacidic soils (Bennett 1989) The recovery of numerous subfossilremains from fen-peat in England and Ireland indicates that thisspecies was a component of fen woodlands sometimes precedingor overlapping with the development of raised mire and coloniz-ation of acidic peat by Pinus (Godwin and Deacon 1974 Pilcher1990 Lageard and Chambers 1993)

In this paper we present the combined results of a palaeoento-mological and dendrochronological investigation of a recentlyexposed subfossil forest from Hat eld Moors in the HumberheadLevels eastern England The forest consisted predominantly ofPinus interspersedwith Betula and isolated Quercus remains Themain focus of the investigation concentrated on the numerousPinus remains and their associated insect faunas as Quercusremains formed only a very minor component of the fossil forestwith just one tree providing material suitable for dendrochronol-ogical dating and fossil insect analysis Dendrochronology wasapplied to date precisely the span of the Pinus woodland inaddition to providing information on its history and dynamics(Boswijk 1998) The suitability of this species for tree-ring analy-sis has been demonstrated by the construction of long Pinuschronologies in Europe (Zetterberg et al 1996) and robust sitechronologies from raised bogs in Great Britain (Chambers et al1997 Boswijk 1998 2002 Lageard et al 1999) and Ireland(McNally and Doyle 1984 Pilcher et al 1995) The primary aimof the subfossil insect study was to characterize the faunal biodiv-ersity of undisturbed Pinus woodland and to examine the sitersquosdevelopment from a palaeoentomological perspective and itswider implications (Whitehouse 1998)

These two palaeoenvironmental studies when combinedcharacterized the biodiversity of undisturbed primary woodlandwithin a de ned period Other palaeoenvironmentalevidence fromHat eld Moors (cf pollen and plant macrofossil studies carriedout by Smith 1985) was also considered in the investigationAbundant charcoal was recovered from the peat samples and sur-face-charred trees were observed but consideration of the roleof re in the early mire landscape has been addressed elsewhere(Whitehouse 2000) The project formed part of a wider palaeoen-vironmental investigation of Thorne and Hat eld Moors Sites ofSpecial Scienti c Interest (SSSI) (Boswijk 1998 Whitehouse1998) and their surrounding oodplains (Whitehouse 1998)

The Humberhead Peatlands

Thorne and Hat eld Moors are two adjacent but distinct raisedmires within the Humberhead Levels an extensive area of formerwetlands in south Yorkshire and Lincolnshire (Figure 1) wherepeat extraction during the mid-1990s uncovered substantial areasof subfossil Quercus and Pinus The Moors have formedimportant foci for palaeoenvironmental research with much pre-vious work largely concentrating on Thorne Moors (cf Erdtman1928 Smith 1958 Buckland and Kenward 1973 Buckland1979 Smith 1985 2002 Roper 1993 1996 Whitehouse 19931997a Dinnin 1997 Boswijk 1998 2002) Here recent den-drochronological analyses of Pinus showed that the spatial andtemporal pattern of Pinus colonization correlated with the expan-sion and contraction of the mire (Boswijk 1998 2002)

Subfossil insect analysis of material from the basal deposits ofThorne Moors has identi ed 20 beetles (Coleoptera) that are nowextinct in Great Britain (Buckland and Kenward 1973 Buckland1979 Roper 1996 Whitehouse 1997a 1977b 1998) Lessresearch has however been carried out on Hat eld Moors (Figure2) On this site south of Thorne Moors peat had formed directlyover gently undulating windblown sands (Smith 1985 2002)These were initially deposited during the Younger Dryasalthough some reworking may have occurred during the Holocene

THORNE MOORS

SOUTH

YORKSHIRE

MISTERTON CARR

Cowick

Sutton Common

Rawcliffe

Goole

Swinefleet

Adlingfleet

Eastoft

Crowle

Scunthorpe

Thorne Colliery

Thorne

Stainforth

Tudworth

Bradholme

Hatfield Sandoft

Wroot

Belton

N

5km

River Aire Old course of

Old course of

River Don

River Went

River Went

TurnbriggDike

New Junction

Canal

River Don

Dutch River

Goole Fields

River OuseHumber Estuary

RiverTrentSwinefleet

Warping Drain

Old course ofRiver Don

Stainforth and

Keadby Canal

Folly Drain

Old course ofRiver Idle

Hatfield Chase

Old course ofRiver Don

River IdleBykers Dike

30

30

30

30

Epworth

15

Isle of Axholme

15

HATFIELD MOORS

LindholmeIsland

0

Figure 1 Location map of Hat eld Moors and the Humberhead Levelseastern England (after an original by PI Buckland OacuteThorne and Hat eldMoors Conservation Forum) Hat eld Moors NGR SE 700060 lat 53deg44rsquoN long ndash0deg 57rsquoW Thorne Moors NGR SE 730160 lat 53deg 329 Nlong ndash0deg 57rsquoW

PackardsSouth

PackardsNorth (2)

PackardsNorth (1)

HAT 4

cal BC

cal BC

Tyrham HallQuarry

c2000 BC

3300-2445 BC(Pinus woodland)

LIND A

HAT 1

LIND B

HAT 3

Kilham

3350-2930cal BC

West

ISLANDLINDHOLME

HAT 2

Porters Drain

cal BC

West Ash Dump (1)

West Ash Dump (2)

0 1 2 km

form

e r course of River Torne

former course of River Idle

2900-2350

2900-2660

1520-1390 cal BC

3090-2890

N

Pollen Sites

Fossil Insect Sites(Whitehouse 1998)

(Smith 1985)

Figure 2 Map of Hat eld Moor with study sites and basal peat initiationdates (reprinted from Whitehouse et al 2001 Figure 58)

(Gaunt 1994 Bateman 1995 Bateman et al 2000) The sandsoverlie the late Devensian lacustrine clay-silts of proglacial LakeHumber (Gaunt 1994) In places sand dunes protrude throughthe milled peat A late-Devensian end-moraine outcrops in thecentre of the site on Lindholme Island (Gaunt 1994) The Mooris bounded on the north east and south by alluvium associatedwith the former courses of the Rivers Don Idle and Torne

On Hat eld Moor where peat depth is greater than at ThorneMoors Pinus trees were observed on parts of the milled bog theirstunted size and shape suggestive of growth on wet mire How-ever Tyrham Hall Quarry on the western edges of the moor wasdifferent Here an area of basal peats had been exposed prior tosand and gravel extraction revealing numerous Pinus stumps andtrunks of a size indicative of mature woodland (Urwald) Thetrees were no longer in situ making determination of the phases ofwoodland development impossible on stratigraphicgrounds alone

Gretel Boswijk and Nicki J Whitehouse Pinus and Prostomis a dendrochronological and palaeoentomological study 587

Many of the trees were rooted into the underlying sands indicat-ing that they represented either a pre-peat forest or one thatbelonged to the very early stages of mire development Inaddition it was unclear whether the trees represented a singlephase of Pinus growth or several successive episodes of growthand decline similar to the pattern observed at Thorne Moors(Boswijk 1998 2002) Peat formation began at about the sametime on both mires (around 3000 cal bc) but a detailed palaeoen-vironmental study by Smith (1985 2002) and more recently byWhitehouse (1998) suggested that the developmental history ofthe sites was different

Dendrochronology

MethodologyCross-sections were taken from the lower trunks of 25 Pinus anda single Quercus (THQ01-26) that were in a 100 3 100 m areaof the quarry that was being cleared of peat The samples wereair-dried and then sanded using progressively ner sandpaper toreveal the ring sequence clearly All the samples had over 50rings which is the minimum number of rings required to deter-mine whether a ring sequence is unique (Baillie 1982)

Baillie (1982) describes the principles and methodology of den-drochronologyThe ring sequences were measured to an accuracyof 001 mm using a binocular microscope and a travelling stageAn input program part of the Dendro for Windows suite (Tyers1999) recorded ring-widths Quercus has a consistent growth pat-tern and the measurement of a single radius is considered rep-resentative of the ring sequence (Baillie 1982) For Pinus a mini-mum of three radii per cross-section were measured allowingpotential problems such as locally absent rings to be identi edand a reliable mean ring sequence to be produced for each Pinussample (Pilcher et al 1995 Zetterberg et al 1996) The CROSprograms (Baillie and Pilcher 1973 Munro 1984) were used toaid cross-matching The CROS programs measure the correlationcoef cient between samples at every position of overlap whichare expressed statistically as a Students t-value For Quercus a t-value of 35 and over is usually indicative that one samplematches another providing the visual match is acceptable (Baillie1982) For Pinus statistical testing of Pinus data by Pilcher et al(1995) indicates that t-values of 4 or greater may be signi cantAt all stages the suggested matches were visually checked usingplotted graphs of the ring sequences Table 1 lists details of theQuercus and Pinus samples

ResultsThe Quercus sample cross-matched with Quercus from ThorneMoors and was dated to 3618ndash3418 bc by comparison withEnglish prehistoric Quercus chronologies (Whitehouse et al1997 Boswijk 1998) The outer surface of the tree as well asthe pith had rotted and the absence of bark edge means that theactual death-date is unknown but the addition of the minimumnumber of sapwood rings expected to be present (Hillam et al1987) provides a terminus post quem of 3408 bc The contempor-ary Quercus woodland at Thorne Moors continued growing until3017 bc but little is known about the extent of Quercus woodlandat Hat eld Moor or its spatial and temporal relationship with thePinus woodland

A 21-tree Pinus chronology (PISYHat eld) was established(Tables 1 and 2) Four samples could not be cross-matched dueto unresolvable problems within the ring sequences caused byvery narrow bands of rings or multiple missing rings The undatedsamples included a tree from which a rot-hole sample (K) forinsect remains was collected

The chronology cross-matched with a oating Pinus chron-ology from Thorne Moors (PISYThorne Boswijk 1998 2002)

but the absolute dating of PISYHat eld was dependent on inter-species cross-matching against the English prehistoric Quercusmaster curve (Hillam et al 1990 Brown and Baillie 1992) Thedating of Pinus against Quercus chronologies has been shown tobe successful in Ireland (Pilcher et al 1995) and proved to beequally successful in England as the chronology was dated pre-cisely to 2921ndash2445 bc (Table 3) PISYHat eld was also foundto be contemporary with a phase of Pinus from Garry Bog CoAntrim Ireland (Pilcher et al 1995) and White Moss CheshireEngland (Chambers et al 1997 Lageard et al 1999) Duringtree-ring analysis consideration was given to the possibility thatthe Pinus could contain a strong site-specic growth pattern thatmay have overridden the common climate signal on which cross-dating is dependent (Baillie 1982) inhibiting cross-matchingbetween the Quercus and Pinus chronologies Radiocarbon dateswere obtained from two Pinus samples THQ21 (4125 6 45 BPSRR-5829) and THQ23 (4105 6 45 BP SRR-5834) These treeswere included in PISYHat eld and were dated absolutely by den-drochronological cross-matching

The chronology PISYHat eld spans 477 years (Figure 3)Between 2921 and 2610 bc three cohorts of Pinus were estab-lished Almost half the trees however have start dates within a35-year period between 2921 and 2887 bc indicating that con-ditions were optimal at this time to support the germination andgrowth of new recruits The length of ring sequences ranged from73 years to over 336 years While the steady rate of die-back over400 years is probably indicative of natural woodland mortalitythe pattern of end and start dates suggests that stress events mayalso have contributed to the death of some trees creating suitablegaps in which seedlings could be established