A Game For The Throne: fortresses and social landscape in Urartu

Pasztor, E. - Roslund, C. 2001. Orientations of Danish Viking Geometrical Fortresses

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of Pasztor, E. - Roslund, C. 2001. Orientations of Danish Viking Geometrical Fortresses

I

OXFORD VI AND SEAC 99 «Astronomy and cultural diversity»

Cesar Esteban

Juan Ant onio Belmonte

Editors/ Editores

i\

l

Proceedingsof the International Conference «OXFORDVI & SEAC 99» held in Museo de la Ciencia y el Cosmos,

La Laguna, June 1999

Memoriasdel Congreso Internacional «OXFORDVI y SEAC 99» celebrado en el Museo de la Ciencia y el Cosmos,

La Laguna, Junio de 1999

© OACIMC Organismo Aut6nomo de Museos del Cabildo de Tenerife

ISBN: 84-88594-24-0

DEPOSITO LEGAL: TF - 1480/2000

MAQUETACION Miriam Cruz (Museo de la Ciencia y el Cosmos)

PREIMPRESION: Contacto

IMPRESION: Producciones Graficas

DEDICADO A LA MEMORIA DE

DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF

CARLOS JASCHEK

2 3

INDEX

FOREWORD 9

PREFACIO 11

CARLOS JASCHEK, II\J MEMORIAM

Arnold LeBeuf 13

INVITED PAPERS

INTRODUCCION A LA MITOLOGiA DE LOS CANARIOS PREHISpAf\IICOS

Antonio Tejera Gaspar 17

TOMBS, TEMPLES AND ORIENTATIONS IN THE WESTERN MEDITERRANEAI\J

Michael Hoskin 27

ARCHAEOASTRONOMY: NEW RESULTS AND METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES

THE STONE ROWS OFTHE WEST OF IRELAf\ID: A PRELIMINARY ARCHAEOASTROI\JOMICAL ANALYSIS Frank T. Prendergast. 35

GAZING AT THE HORIZON: SUB-CULTURAL DIFFERENCES IN WESTERN SCOTLAND?

Gail Higginbottom, Andrew Smith, Ken Simpson, and RogerClay 43

ARCHAEOASTRONOMY STUDY ON THE DISPOSITION OFSARDIf\IIAN NURAGHES IN THE BRABACIERA VALLEY

Mauro Peppi no Zedda and Paolo Pili .51

ORIENTATIONS OF THE PHOENICIAN AND PUf\IIC SHAFT TOMBS IN MALTA

Frank Ventura .59

ORIENTATION OF DANISH GEOMETRICAL VIKING FORTRESSES

Emilia Pasztor andCurt Roslund 65

ARCHAEOASTRONOMICAL OBJECT OF THE Ef\IEOLITHIC EPOCH IN RUSSIA

Tamila Potyomkina 71

01\J ANCIENT ASTRONOMY IN ARMENIA

Elma S. Parsamian 77

CONSIDERATIONS CONCERNING POSSIBLE MODALITIES TO ESTABLISH THE ASTRONOMICAL DIRECTIONS IN DACIAN SANCTUARIES

Florin Stanescu 83

"MUSTACHED" BARROWS ASTHE HORIZON SOLAR CALENDARS OFEARLY NOMADSOFKAZAKHSTAI\J

Nyssanbai M. Bekbassar 91

5

•

SACRED LANDSCAPES AND COSMIC GEOMETRIES: A STUDY OF HOLY PLACES OF NORTH INDIA

RanaPB. SinghandJ. McKimMalville 99

ARCHITEG URALALIGNMENTS AND OBSERVATIONALCALENDARS IN PREHISPANIC CENTRAL MEXICO

IvanSprajc. ..... .. .............. 107

PROMISING ARCHAEOASTRONOMY INVESTIGATIONS IN CHILE

MaximeBoccas, PatricioBustamanteDiaz,CarlosGonzalezVargas, and CarlosMonsalveRodriguez 115

POTENTIAL ASTRONOMICAL CALEf\IDARS AND A CULTURAL INTERPRETATION THEREOF ALONG THE PALAT' KWAPI TRAIL OF NORTH CENTRAL ARIZONA

Bryan C. Bates and LeahCoffman 125

ROCK ART AND ASTRONOMY IN BAJA CALIFORNIA

Ed C. Krupp....... 133

HALEETS, THE AGATE POINT PETROG LYPH STONE

John H.Rudolph.. ......... 141

ISSUES IN ARCHAEOASTRONOMY METHODOLOGY

Bryan C. BatesandTodd Bostwick 147

EXPERIMENTAL ARCHAEOASTRONOMY: A LABORATORY FO R STUDY OF INTERAG ION OF LI GHT SHADOW AND SYMBOLIC IMAGERY ,

AngelaM. Richman, Von Del Chamberlain, and Joe Pachak 157

ASTRONOMY IN HISTORY AND HUMAN THINKING

BABYLONIAN ASTRONOMICAL RECORDS AND THE ABSOLUTE CHRONOLOGY OF THE NEAR EAST CIVILIZATIONS

V G.Gurzadyan,and H.Gasche 165

THEWHOLE COSMOSTURNS AROUND THE POLAR POINT: ONE·LEGGED POLAR BEINGSAND THEIR MEANING

MichaelRappenqluck 169

FINDING THE DIREGION TO MECCA WITH FOLK ASTRONOMICAL METHODS: QIBLA SCHEM ES IN A YEM EN I TEXT BY AL-FARIST

PetraG. Schmid!. 177

ASTRONOMY AND BASQUE LANGUAGE

HenrikeKnorr 183

THE CALENDAR IN MEDIEVAL BULGARIA

VesselinaKoleva ................................... .. ........ ... .................. .............. ...................................................195

COPE Rf\I ICAN ICONOGRAPHY IN MICHELANGELO'S LAST JUDGMENT: THE IDEA OF THE CENTRE OF THEUNIVERSE

ValerieShrimplin 203

THE SUBARTIC HORIZON AS A SUNDIAL

Thorsteinn vilhjatrnsson 211

PRE-COLUMBIAN ASTRONOMY IN CENTRAL AREA OF THE PERU

Elena OrtizGarda .. .... ..............................217

UNE POSSIBILITE DE DATATION HISTORIQUE ABSOLUE DE LA TABLE DES ECLIPSES DU CODEX DE DRE SDE PAR LE PASSAGE DES LEONIDES

Arnold Le Beuf. 225

STARBORN : ANALYS IS OF ASTRONOMICAL SYMBOLI SM IN A NATIVE AMERICAN LEGEND

Von Del Chamberlain 233

HISTORICAL LEXICOGRAPHY AND THE ASTRONOMICAL LEXICON

TerryMahoney 239

CALENDARS: CYCLES OF TIME AT THE END OF THE MILLENNIUM

THE BABYLONIAN CIVIL CALENDAR 731-626 B.C. EVIDENCE FOR PRE-"M ETONIC PERIODIC INTERCALATION PATTERNS

ManuelGerber 245

LUNAR SEASONAL CALENDARS FROM THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST

DuaneW. Eichholz 249

DOMESTICATING THE LANDSCAPE - THE PROBLEM OF THE 17-DEGRE E FAMILY ORIENTATION IN MESOAMERICA

HzbietaSiarkiewicz 255

CALENDRICAL INFORMATION ON MAPUCHE CERAMICS

CarlosGonzalezVargas 263

AGR I~~'LTURA[(.AtlNDARS -AND CALENDAR FORECASTING PREDIGI ONS AN INTERPRETATION OF <,

CANARY ABORIGINAL CALENDARS "

Jose Manuel GonzalezRodrfg uez ~. ,< 269

THE AGE OF AQUARIUS : A MODERN CONSTELL ~TION MYTH

NicholasCampion.............. . . 277

7 6

THE ORIGIN OF CONSTELLATIONS

DATE AND PLACE OF ORIGIN OF THE ASIAN LUNAR LODGE SYSTEM

Brad leyE.Schaefer 283

ADAPA, ETANA AND GILGAMES THREE SUMERIAN RULERSAMONG THE CONSTELLATIONS

ArkadiuszSoltysiak 289

HUNTING THE EUROPEAN SKY BEARS: HERCULES MEETS HARZKUME

RoslynM. Frank 295

NEWARGUMENTS FORTHE MINOAN ORIGIN OFTHESTELLAR POSITIONSIN ARATOS' PHAINOMENA

G6ran Henrikssonand MaryBlomberg 303

AN ASTRONOMICAL INTERPRETATION OF FINDS FROM MINOAN CRETE

Peter E.Blomberg 311

DID THERE EXIST THE BALTIC ZODIAC?

JonasVaiskl1nas .319

ETHNOASTRONOMY: THE SKY OF LIVING PEOPLE

BULGARIAN TRADITIONAL COSMOGONICAL AND COSMOLOGICAL BELI EFS (AFTER ETHNOGRAPHIC DATA FROM AD 19th TO 20 th )

Dimiter Kolev .327

METEORITES OFCAMPO DEL C1 ELO: IMPACT ON THE INDIAN CULTURE

Sixto R. Gimenez Benitez, Alejandro M. Lopez, and LuisA. Mammana 335

CULTURAL CONCE PTS OFTHE MILKY WAY

PhyllisBurton Pitluga 343

ASTRONOMICAL REFERENCE AND SPIRITUALITIES IN EMPIRICAL ABORIGINAL NIGHT SKY

Hugh Cairns 349

8

ORIENTATION OF DANISH GEOMETRICAL VIKING FORTRESSES

Emilia Pcisztor Planetarium, H-6000 Kecskernet, Hungary

Curt Roslund Section of Astronomy, Gothenburg University,

5-41296 Gothenburg, Sweden

ABSTRACT

Three geometrical Viking ring-fortresses in Denmark have generally been taken to be orientated closely towards the four cardinal points. Bymeasuring the orientations of their main axes with a precisiontheodolite, it was found that the fortresses differ considerablyfrom eachother in orientation, in spite of their similargeometric~ _ and from the cardinal points. Alternative suggestions for the deviation in orientation-are-r:>~~

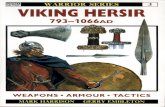

In Denmark four impressivecircular fortressesbuilt around 980 at the end of the Viking Age havecome to light. Theyare known for their preciselayout. Their ground plans are dominated by a perfectly circular ring-rampart divided into four segments of equal length by the gates for two straight roadsthat meet at right angles in the centre of the ramparts. The construction isenhanced by the fact that the roads seemto be aligned with the cardinal points of the compass.

DESCRIPTION OFTHE SITES

The best known of the ring-fortresses is Trelleborg situated at the confluence of the Tude and Varby rivers on a flat tongue of land four kilometres from the shore of the Great Belt on the island of Zealand. The site was excavated by Paul Norlund between 1934 and 1942 (Nerlund 1948) and the rampart reconstructed and the outlines of the roads and houses within the rampart marked on the ground. The interior diameter of the rampart is 134 metres which is also the length of the two roads. In each quadrant formed by the two roads, four houses were built along the sides of a square aligned with the roads. All houses had the same ground plan and measured about 30 metres in length.

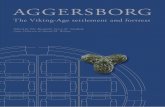

Aggersborg was the second site to be recognised as a ring-fortress. It is situated on the Jutland peninsula on the northern shore of the Limfjord at its narrowest point at Aggersound. It was partly excavated in the late 1940s (Roesdahl 1981). The ground plan is similar to that of Trelleborg but Aggersborg is built on a much larger scale with a diameter of 240 metres with 48 long-houses in twelve square blocks.

The Fyrkat ring-fortress also lies on the Jutland peninsula on a low ridge above the Onsild river four kilometres from its outlet in the Mariager Fjord 35 kilometres from the sea. It was excavated in the 1950s (Olsen et a/. 1977). It has exactly the same layout as Trelleborg but is somewhat smaller or 120 metres in diameter.

The last site to be identified as a ring-fortress in Denmark was Nonnebakken on the island of Funen (Thrane et al. 1982: 109) located on a hill overlooking the Odense river seven kilometres from its outlet in the Odense Fjord thirteen kilometres from the sea. Few traces of the fortress remain above ground. The rampart was removed in 1905 but the fortress seems to have been of the same size as Fyrkat.

65

As recently as 1989, a ring-fortress was discovered in the Swedish town of Trelleborg in the province of Scania, belonging to Denmark at the end of the Viking Age (Jacobsson 1995). It is located some hundred metres from the open shore of the Baltic. It was of the same size as the Danish Trelleborg but it lacked the strict geometry and symmetry of the latter. There might also be signs of another ring-fortress in Scania at Borgeby on the Kavlinqe river five kilometres from its

oulet into the Sound between presentday Denmark and Sweden.

HISTORY

A prototype for the Danish ring-fortresses has been searched for. No immediate forerunner has so !ar been identified in Denmark. The closest analogy in design comes from a series of fortifications in Flanders and Zeeland. [he best researched fortress is at Oost-Souburg in the presentday Netherlands. Although its construction date probably is so~ewhat earlier than its Danish counterparts, both its size and layout are the same as those of Trelleborg. Two roads at right angles cut through its circular rampart in four places, dividing the rampart into four equal segments, the differences being that the roads deviate significantly from the cardinal points and that the houses in each quadrant do not conform to a

regular pattern (Trimpe Burger 1975).

The high degree of conformity of the ground plans and their sophisticated geometrical design, coupled with the great demand for manpower and material for the execution of the massive fortresses, prove that there must have been an incontestable centralised authority behind their planning and construction. The dating of Trelleborg and Fyrkat IS based on dendrochronology and corroborated by traditional archaeological dating of artifacts. All the available evidence points to a construction date around 980 for Trelleborg (Bonde et al. 1984) which is also a plausible date for the other three fortresses. This was a time when king Harald Bluetooth had united all Denmark which added to his prestige and responsibilities. His building activities did not end with the ring-fortresses. He is remembered for building the 700 metre long bridge over the Vejle river at Ravning (Ramskou 1980), for erecting the famous Jelling monuments (~ro~h 198~) an.d for reconstructing the border rampart of Danevirke (Andersen 1977). His works are characterised as being Impressive, inno

vative and prestigious.

On the basis of the archaeological evidence, there is no clear answer to what purpose the ring-fortresses would have served. A function as military strongholds is indicated by their huge ramparts and their strategical position in secluded spots well away from the open sea lanes. On the other hand, their location near trade routes both by overland and by sea, points at defended commercial centres. Although located some distance away from the sea, they could all be reached by ship. Finally, their orderly design could be seen as an expression of a romanticised concept of an ideal city.

SYMBOLISM

The ground plan of the fortresses in the form of a circle with two perpendicular diameters could have been a geometrically graceful way of dividing a circular area into four quadrants that would have appealed to military engineers. However, the figure of a circle with four spokes might have had a deeper meaning. It is a well-known symbol in Scandinavian rock carvings and archaeological finds, especially from the Bronze Age (Maimer 1981: 66-75). The famous Trundholm sun chariot like many others has wheels with such impractical divisions for carrying a heavy load (Gelling et al. 1969: 14-15; Green 1991: 66). It is generally assumed to have been a sun symbol (Green 1991) but it could also very well have been a

symbol of cosmos with its four cardinal directions.

Sometimes, the quadrants in rock carvings are filled with squares or dots like the square blocks of houses in the ring-fortresses. This more elaborate design also becomes more frequent with time in northern Europe. It is found on the rim of a shield from the migration period (Fettich 1930: 223). It was carved on the cross-guard of a sword from the ninth century (Posta 1930: 293) and on the top of a weight from the Viking Age (Reinerth 1941: 1354). The same motif can be seen on an iron ring to an entrance gate to a church in Sweden (Paulsen 1939: Fig. 123). The symbol has been wide-spread to the present time in other parts of Europe as well. It appears on objects as diverse as embroidered textiles and coloured eggs. From having been a unique solar symbol, it has been transformed into a magical sign with protective and averting

properties (Saqi 1951).

ORIENTATIONS

The ground plans of the ring-fortresses demonstrate that those who were responsible for their construction were able to solve a number of problems of geometrical and metrological nature. They knew how to set out accurate circles and to draw lines at right angles to each other in order to fit the houses, ramparts and moats into a preconceived pattern. The attention they paid to detail is clearly shown by the fact that the houses in the quadrants at Trelleborg deviated only 0.2 metres from an average length of 29.42 metres. It would have been natural enough to expect these master builders to ensure that the grid system of roads within the ramparts comformed to certain principles. It has been taken for granted that the fortresses were orientated towards the four cardinal directions.

The south direction might have been important for the Norsemen. At this northern latitude of the fortresses, the sun barely comes above the horizon in winter. At Trelleborg it reaches a maximum height of only eleven degrees in the south at local noon at the winter solstice. The south was also the direction in which Valhalla according to Norse mythology was located. The three famous ship burials at Oseberg, Gokstad and Tune had their prows pointing towards the south. At Ladby on the Danish island of Funen, the interred ship was also facing south (Brondsted 1965).

The east direction could have had a relation with the sunrise. The sun rises exactly due east on two occasions in the year, at the equinoxes. In summer the sun rises north of east and in winter south of east. On a certain date, the sun rises every year in the same direction. It was the rule during the Middle Ages that churches should preferably be orientated towards the east. By studying the orientation of medieval churches in the Carpathian Basin, it was proved that the date of the vernal equinox in the Julian calendar had been used more often than the proper establishment of true east. It was also found that a good deal of the churches had been orientated towards the sunrise on the saint's day to whom the church had been devoted (Guzsik 1986).

SUGGESTIONS FOR ORIENTATIONS

In order to find how closely the road grid corresponds with the cardinal points, the azimuth of the east-west axis was measured with a precision theodolite with reference to the sun. The result is shown in Table 1 for the three existing Danish ring-fortresses and is surprising. The fortresses differ considerably from each other in orientation and from the cardinal directions. The usual picture of comparison of the ground plans for the fortresses aligned with the cardinal directions is misleading - upper part of Figure 1 - and should be replaced with one showing the true orientations of the fortresses - lower part of Figure 1.

TABLE 1. Julian dates for sunrises and sunsets through gates to Danish geometrical Viking fortresses.

FORTRESSES TRELLEBORG

Azimuth of east gate 100° 58'

Elevation of horizon 1° 16'

Declination of the Sun -5° 41 '

Date of sunrise (first light) Mar 01

Oct 02

Azimuth of west gate 280° 58'

Elevation of horizon 0° 18' Declination of the sun +5° 49' Date of sunset (last night)

Mar 30

Sep 03

AGGERSBORG -t' FYRKAT_

83° 09' 86° 47'

0° 00' 2° 00'

+3° 01' +2° 58'

Mar 23 Mar 23

Sep 10 Sep 10

263° 09' 266° 47'

0° 00' 0° 45'

-4° 26' -1° 44'

Mar 03 Mar 10

Sep 29 Sep 22

The disparity in orientation could be the effect of a random scatter around the cardinal points due to the builders lack of concern in making the orientations precise. The mean deviation is no more than eight degrees. This explanation goes contrary to the care with which the ground plans were laid out.

66 67

One reason fo r the observed deviatio n from the cardinal points could have been that the bui lders never intend ed to include these in their plans. Instead of di recting the east-west axis towards the sunri se or sunset at the eqinoxes, they might for one reason or other have decided on oth er dates. The sunrise on March 23 ,in Table 1 seen th rough the east gate at bot h Aggersborg and Fyrkat is interesting as this date is close to both the ecclesiast ical date In the Juhan calendar for the vernal eqinox on March 21 and to the feast of t he Annunciation of th e Virgin Mary on March 25 . The latter date commenc ed the official year in England until much later (Hutton 1996: 8). The date for the sunrise at Trelleborg throu gh its east gate on March 1 does not agree with those at Agg ersborg and Fyrkat, but IS still mterestmq because March 1 was

counted as th e form al beginning of the year by the Franks.

The Easter ful l moon could also have played a role in the newly christianised Denmark. Table 2 shows the rise of thi s moon through th e east gat e at Trellebo rg for four years prior to th e w inter 980-81 w hen th e last trees for the construction of the fortress were cut down. There is a close agreement in orientati on for the year 977 w hen the Easter full moon appeared on Good Friday. The agreement could be coincid ental, as long as we have no knowledge of the exact year

w hen the plan was laid out.

TABLE 2 . Azimuths of the rising points o f the Easter full moon (upper limb) through the east gate at Trelleborg.

Year AD 977 97 8 979 980

Azimuth of east gate

Rising point of ful l moon

Julian date of full moon

100° 58 '

101° 03 '

Apr 06

100° 58 '

98° 21 '

Mar 27

100° 58 '

113° 47'

Apr 15

100° 58 '

104° 57'

Apr 03

Julian date of Easter Sunday Apr 08 Mar 31 Apr 20 Apr 11

CONCLUSIONS

There is no doubt that the Danish ring-fort resses were bui lt in accordance with advanced geomet rical and metrological rules. However, thi s does not at first had seem to apply to the orientations, although it is conceivable that the orientations could have been set out after formulas we do not know about .

RE FEREN CES

H. H. AN DERSEN, Jyl/ands voId (Arhus, 1977).

N. BO NDE and K. KRISTENSEN, "The Age of Trelleborg. Dendrochronological Dating", Aarb0ger for Nordisk Oldkyndighed og Historie 1982 (1984), 139 -152 .

J. BR0 NDSTED, The Vikings (Hormondsworth, 1965).

N. FETTICH, "De r Schildbuckel von Herpoly" , Acto Archaeologico 1 (Copenhagen, 1930).

P. GELLING, and H. E. DAVIDSON, The Chariot of the Sun ond other Rites and Symbols of the Nortner« Bronze Age (London, 1969).

M . GREEN , The Sun-Gods of Ancient Europe (Londo n, 199 1).

T. GUZSIK, "Sol Aquinoetiolis - zur Froge der cquinoktiolen O stung in Mittelalter", Periodico Pofitechnica 22 (Budapest 198 7') 3 -4 1912 13. r r

R. HUTTO N, The Stations of the Sun (O xford, 199 6).

B. JACO BSSO N, " Den arkeologiska undersakningen av Trelleborg ", in Trellebargen by B. Jacobson, E. Aren and K. A. Blom (Lund, 1995).

K. J. KROGH, "The Royal Vikinq-Aqe Monuments at Jelling in the light of recent archaeological excavations", Acta Archoeotoqico 53 (1982), 183-2 16.

M. P. MALMER, A Cbotoioq ico! Study of Norlh European Rock Art (Stockholm, 198 1).

P. NelRLUND, "Trelleborg", Nordiske Fortidsminder 4:1 (1948) .

O . OLSEN, H. SCHMIDT, and E. ROESDAHL, Fyrkat. En iysk vikingeborg I-II (Copenhagen, 19 77).

P. PAULSEN, Ax! und Kreuz bei den Nordgermanen (Berlin, 1939).

B. POSTA, Regeszeti tanulmonyok Oroszfb/d6n III (Budapest, 1930 ).

T. RAMSKOU, "Vikingetidsbroen over Vejle /I-dal" . Nationo/museets Arbejdsmark 1980 (1980), 25-32.

H. RE INERTH, Vorgeschichte der Deutschen Stamme III (Berlin, 1941) .

E. ROESDAHL, "Aggersborg in the Viking Age", in Proceedings of the Eighth Viking Congress, ed. by H Bekker-N ielsen et 0/. (O dense, 1981).

K. SAG I, "Arpodkor i vor6zs1 6s regeszeti emlekel" , Veszprem Megyei Muzeumok Kbz/emenyei (Veszprem, 1965), 57 -8 1.

H. THRANE, T. NYBERG, f GRANDT-NIELS EN, and H. VENGE, Fro bop/ads til bispeby. Oden se til )55 9 (Odense, 1982) .

J. A. TRIMPE BURGER, "The geometrical fortress of Oos t-Souburg (Zeeland)" , Chateau Gaillard 7 (1975) .

Fyrkat Trelleborg

Figure 1. The upper row shows how the

ground plans o f Danish ring

fortresses generally are depicted and

the lower row how they should be

shown to include their true

orientati ons .

69 68