Overcoming technical and musical challenges for the oboe ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Overcoming technical and musical challenges for the oboe ...

-

Overcoming technical and musical challenges forthe oboe using excerpts from orchestral and solorepertoireEernisse, Elliot Adamhttps://iro.uiowa.edu/discovery/delivery/01IOWA_INST:ResearchRepository/12730590750002771?l#13730786190002771

Eernisse. (2016). Overcoming technical and musical challenges for the oboe using excerpts fromorchestral and solo repertoire [University of Iowa]. https://doi.org/10.17077/etd.dgcwkot3

Downloaded on 2022/07/10 07:12:22 -0500Copyright 2016 Elliot Adam EernisseFree to read and downloadhttps://iro.uiowa.edu

-

A GUIDE TO OVERCOMING TECHNICAL AND MUSICAL CHALLENGES FOR

THE OBOE USING EXCERPTS FROM ORCHESTRAL AND SOLO REPERTOIRE

by

Elliot Adam Eernisse

An essay submitted in partial fulfillment

of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts

degree in Music in the

Graduate College of

The University of Iowa

August 2016

Essay Supervisor: Professor Kristin Thelander

Graduate College

The University of Iowa

Iowa City, Iowa

CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL

____________________________

D.M.A. ESSAY

_________________

This is to certify that the D.M.A. essay of

Elliot Adam Eernisse

has been approved by the Examining Committee for

the essay requirement for the Doctor of Musical Arts degree

in Music at the August 2016 graduation.

Essay Committee: ____________________________________________

Kristin Thelander, Essay Supervisor

____________________________________________

Courtney Miller

____________________________________________

William LaRue Jones

____________________________________________

Benjamin Coelho

____________________________________________

Christine Getz

ii

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my outstanding committee members Dr. Kristin Thelander, Dr.

Courtney Miller, Dr. Christine Getz, Dr. William LaRue Jones and Professor Benjamin Coelho for

their invaluable wisdom and guidance during the time I spent at the University of Iowa. I would

also like to thank my wonderful husband Jacob for his unwavering support through the ups and

downs of completing this degree.

iii

Public Abstract

This document serves as a guide for college oboists who wish to improve their playing by targeting

technical and musical challenges with annotated excerpts from orchestral and solo oboe repertoire.

The contents of this essay are categorized by eighteen different performance challenges such as

intonation, little-finger agility, dynamic contrast through the full range of the oboe, half-hole technique,

phrasing, and rapid tonguing. Each chapter begins by identifying technical or musical difficulties and

provides advice on how to overcome it using excerpts from the oboe repertoire. Each chapter presents

two annotated orchestral excerpts and one solo oboe excerpt that targets the technical or musical

difficulty. The orchestral excerpts are selected from standard orchestral repertoire from the eighteenth

to the twentieth century. The oboe solo excerpts are selected from repertoire that is widely taught in

most universities. In conjunction with professional instruction, this guide may aid in improving an oboe

student’s performance abilities.

My goal in writing this guide is two-fold: to give aspiring oboists a task-specific tool to use as they

struggle with musical and technical impediments, and, at the same time, to familiarize them with

orchestral and solo oboe repertoire.

iv

Table of Contents

List of Tables .................................................................................................................................... v

List of Examples .............................................................................................................................. vi

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1

Chapter I : Reinforcing Basic Oboe Techniques ............................................................................... 7

Chapter II : Intonation .................................................................................................................... 10

Chapter III : Half-Hole Technique ................................................................................................... 16

Chapter IV : Rapid Tonguing .......................................................................................................... 20

Chapter V : Dynamic Shaping Over Long Phrases .......................................................................... 24

Chapter VI : Endurance .................................................................................................................. 30

Chapter VII : Mastering Left F ........................................................................................................ 37

Chapter VIII : Voicing Intervals Throughout the Range ................................................................. 41

Chapter IX : Gaining Proficiency in the Extreme High Register...................................................... 46

Chapter X : Gaining Proficiency in the Low Register ...................................................................... 52

Chapter XI : Smooth Descending Slurs ........................................................................................... 56

Chapter XII : Developing an Awareness of Contextual Playing ...................................................... 60

Chapter XIII : Ornamentation ......................................................................................................... 66

Chapter XIV : Playing Extremely Softly........................................................................................... 72

Chapter XV : Care of Note and Phrase Endings ............................................................................. 77

Chapter XVI : Developing Technical Proficiency ............................................................................ 82

Chapter XVII : Rubato ..................................................................................................................... 86

Chapter XVIII : Little Finger Technique .......................................................................................... 90

Chapter XIX : Dotted Rhythm Precision ......................................................................................... 95

Bibliography ................................................................................................................................... 99

Appendix : Reproduction Permissions ......................................................................................... 102

v

List of Tables

Table 1 Oboe range in listed examples ..........................................................................................xiii

Table 2 Illustration of the parts of an oboe reed ............................................................................ ix

Table 3 Oboe Keys ............................................................................................................................ x

vi

List of Examples

EX. II.1 Samuel Barber, Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, movement 2, mm. 1-14. .................. 12

EX. II.2 Ludwig Van Beethoven, Symphony no. 7 in A Major, op. 92, movement 1, mm. 1-22. .... 13

EX. II.3 Vincenzo Bellini, Concerto in E-Flat Major, movement 1, mm. 1-38. ................................ 14

EX. III.1 Maurice Ravel, Le Tombeau de Couperin, movement 1, mm. 1-22. ................................. 17

EX. III.2 Johannes Brahms, Symphony no. 1 in C Minor, op. 68, movement 2, mm. 35-49........... 18

EX. III.3 Camille Saint-Saëns, Sonata for Oboe and Piano, op. 166, movement 3, mm. 57-73. ..... 19

EX. IV.1 Gioacchino Rossini, Overture to La Scala di Seta, mm. 22-56. ......................................... 21

EX. IV.2 Johann Sebastian Bach, Brandenburg Concerto no. 2 in F Major, BWV 1047, movement

3, mm. 79-101. ....................................................................................................................... 22

EX. IV.3 Benjamin Britten, Six Metamorphoses after Ovid, op. 49, movement 2, “Phaeton,” mm.

26-38. ..................................................................................................................................... 23

EX. V.1 Long tone exercise ............................................................................................................. 24

EX. V.2 Richard Strauss, Don Juan, mm. 232-314. ......................................................................... 26

EX. V.3 Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony no. 3 in E-Flat Major, op. 55, “Eroica,” movement

4, mm. 339-382. ..................................................................................................................... 27

EX. V.4 Tomaso Albinoni, Concerto for Oboe in D-Minor, op. 9, no. 2, movement 2, mm.

17-34. ..................................................................................................................................... 28

EX. VI.1 Johannes Brahms, Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, op. 77, movement 2, mm 1-45. .. 31

EX. VI.2 Johann Sebastian Bach, Cantata no. 82, Ich Habe Genug, BWV 82, movement 1, mm.

1-37. ....................................................................................................................................... 33

EX. VI.3 Richard Strauss, Concerto for Oboe and Small Orchestra, movement 1, mm. 1-73. ....... 35

EX. VII.1 Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky, Symphony no. 4 in F Minor, op. 36, movement 2, mm.

1-46. ....................................................................................................................................... 38

EX. VII.2 Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony no. 3 in E-Flat Major, op. 55, “Eroica,” movement

3, mm. 203-258. ..................................................................................................................... 39

EX. VII.3 Benedetto Marcello, Concerto for Oboe in C Minor, movement 2, mm. 1-14. .............. 40

EX. VIII.1 Reed alone exercise ........................................................................................................ 42

vii

EX. VIII.2 Johannes Brahms, Symphony no. 1 in C Minor, op. 68, movement 1, mm. 15-39. ....... 43

EX. VIII.3 Igor Stravinsky, Pulcinella Suite, “Serenata,” mm. 1-10. ................................................ 44

EX. VIII.4 Robert Schumann, Three Romances for Oboe and Piano, op. 94, movement 1, mm.

25-54. ..................................................................................................................................... 45

EX. IX.1 Igor Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring, Second Part “Introduction,” rehearsal number

“80” to “85.” .......................................................................................................................... 47

EX. IX.2 Maurice Ravel, Le Tombeau de Couperin, movement 3, mm. 65-128. ............................. 49

EX. IX.3 Gilles Silvestrini, Six Etudes for Oboe, movement 4, “Sentier dans les Bois de Auguste

Renoir,” Final phrase after second fermata to the end. ........................................................ 51

EX. X.1 Serge Prokofiev, Classical Symphony in D Major, op. 25, movement 4, 1 measure before

rehearsal no. “53” to the 4th measure of rehearsal no. “54.”................................................ 53

EX. X.2 Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Scheherazade, movement 3, mm. 1-51. ................................... 54

EX. X.3 Francis Poulenc, Sonata for Oboe and Piano, “Deploration,” mm. 15-27. ........................ 55

EX. XI.1 Camille Saint-Saëns, Samson and Delilah, opening cadenza, m.1. ................................... 57

EX. XI.2 Johannes Brahms, Symphony no. 2 in D Major, op. 73, movement 3, measures

218-240. ................................................................................................................................. 58

EX. XI.3 Carl Nielsen, Fantasy Pieces for Oboe and Piano, op. 2, movement 1, mm. 1-18............ 59

EX. XII.1 Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony no. 3 in E-Flat Major, “Eroica,” movement 2, mm.

1-68. ....................................................................................................................................... 62

EX. XII.2 Gioacchino Rossini, Overture to La Scala di Seta, mm. 1-21. .......................................... 63

EX. XII.3 Carl Reinecke, Trio in A Minor for Oboe, Horn and Piano, op. 188, Movement 1, mm.

40-78. ..................................................................................................................................... 64

EX. XIII.1 Maurice Ravel, Le Tombeau de Couperin, movement 2, mm. 35-47. ............................. 67

EX. XIII.2 Claude Debussy, La Mer, movement 2, mm. 1-30. ......................................................... 69

EX. XIII.3 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Concerto for Oboe in C Major, K. 314, movement 3,

mm. 1-18. ............................................................................................................................... 70

EX. XIV.1 Dimitri Shostakovich, Symphony no. 5 in D Minor, op. 47, movement 3, 1 measure

before rehearsal no. “84” through rehearsal no. “85.” ......................................................... 73

viii

EX. XIV.2 Claude Debussy, La Mer, movement 3, 4 measures before rehearsal no. “54”

through the 16th measure of rehearsal no. “55.” ................................................................. 74

EX. XIV.3 Ralph Vaughan Williams, Concerto for Oboe and Strings, movement 1, mm.

87-104. ................................................................................................................................... 75

EX. XV.1 Maurice Ravel, Le Tombeau de Couperin, movement 3, mm 1-28……………………………….78

EX. XV.2 Igor Stravinsky, Pulcinella Suite, movement 4, Variation 1a, mm. 1-32………………………..79

EX. XV.3 Camille Saint-Saëns, Sonata for Oboe and Piano op. 166, movement 2, mm.

62-70..................................................................................................................................….81

EX. XVI.1 Johannes Brahms, Variations on a Theme by Haydn, op. 56, Variation 3, mm.

127-145. ................................................................................................................................. 83

EX. XVI.2 Franz Schubert, Symphony no. 8 in B-Minor “The Unfinished,” movement 2, mm.

98-126. ................................................................................................................................... 84

EX. XVI.3 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Oboe Quartet in F Major, K. 370, movement 3, mm.

103-115. ................................................................................................................................. 85

EX. XVII.1 Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Scheherazade, movement 2, mm. 1-76. ............................... 87

EX. XVII.2 Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Scheherazade, movement 3, mm. 119-141. ......................... 88

EX. XVII.3 Johann Wenzel Kalliwoda, Morceau de Salon, op. 228, mm. 81-106. .......................... 89

EX. XVIII.1 Sergei Prokofiev, Classical Symphony in D, op. 25, movement 2, 1 measure before

rehearsal no. “39” through the 7th measure of rehearsal no. “41.” ...................................... 91

EX. XVIII.2 Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Scheherazade, movement 4, mm. 280-337. ........................ 92

EX. XVIII.3 Vincenzo Bellini, Concerto in E-Flat Major, movement 2, mm. 153-169. .................... 93

EX. XIX.1 Felix Mendelssohn, Symphony no. 3 in A Major “Scottish,” movement 2, mm.

1-88. ....................................................................................................................................... 96

EX. XIX.2 Franz Schubert, Symphony no. 9 in C-Major “The Great,” movement, 2, mm.

1-36. ....................................................................................................................................... 97

EX. XIX.3 Tomaso Albinoni, Concerto for Oboe in D-Minor op. 9, movement 1, mm.

42-80. ..................................................................................................................................... 98

ix

Table 1

Oboe range in listed examples

Pitch names are labeled according to the American Standard Pitch Notation System (also known

as Scientific Pitch Notation).1 The oboe’s range in the following excerpts encompasses B♭3 to

G#6.

1 Robert W. Young, “Terminology for Logarithmic Frequency Units,” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 11, no. 1 (July 1939): 134-139.

xi

2nd Octave Key

Half-hole Plate

1st Octave Key (on reverse)

A♭/G# Key

Low B Key

Low B♭/A# Key

Key Left F Key

E Key

Right F Key

D Key

D♭/C# Key

/

B Key

A Key

G Key

Left E♭/D# Key

Right A♭/G# Key

F# Key

Low C Key

Right E♭/D# Key

Table 3

Oboe keys

1

Introduction

Oboists spend their entire careers developing ways to overcome the technical and musical

challenges the instrument presents. This ongoing process is never completely realized. New students of

the oboe must surmount a myriad of hurdles in order to become successful musicians. Although etude

and method books can help students learn fundamentals, they do not always provide guidance on how

to overcome specific challenges. For example, a student wishing to improve voicing into the high

register of the instrument must scour etude books to find a relevant passage. Even if the student finds

such a passage or etude, it may not be annotated with practical advice for overcoming the difficulty.

Many oboists can only turn to their teacher for a solution, or resort to or inventing one on their own.

For a young musician, inventing solutions can often lead to incorrect habits in practicing.

Consequently, I have created a guide for aspiring oboists. It promises to help them find their way

through this difficult terrain. The guide consists of excerpts from orchestral and solo oboe repertoire

which target specific playing issues. I have personally tested a number of excerpts that can be utilized to

provide effective working solutions to technical and musical problems. The excerpts are annotated with

strategies which address specific playing difficulties. This guide offers a valuable tool for college oboists

and their teachers to use to help them with the plethora of trials they are likely to encounter. By

practicing these excerpts, students are able to confront musical challenges one at a time. The chapters

include playing challenges such as intonation, little-finger agility, dynamic contrast through the full range

of the oboe, slurring downward, half-hole technique, phrasing, and rapid tonguing. At the same time,

each chapter introduces students to a range of solo and orchestral oboe repertoire.

While this guide uses excerpts to target specific playing issues, its aim is not to prepare students for

orchestral auditions. Nevertheless, many of the examples can indeed improve the player’s musical

sophistication and give the oboist the opportunity to be more competitive in an audition setting. This

2

guide, however, has a different primary goal. In conjunction with professional instruction, it can be used

to improve an oboist’s abilities during the learning phase. The excerpts have been selected from solo

oboe repertoire widely taught in most universities. Most college level oboists will encounter many of

these pieces sometime in their academic careers. Orchestral excerpts have been selected from standard

orchestral repertoire from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. Many of them appear on audition

lists for major symphony orchestras. Exposure to these pieces during the learning process makes

students aware of the oboe’s magnificent possibilities, and can inspire a deeper commitment to the

instrument.

This guide does not address reed making fundamentals, but it does offer some practical advice.

Furthermore, it does not include extended oboe techniques, as there is already a body of literature on

this particular subject. In short, the intention of this guide is to augment the current instructional

literature for oboe players at the college level. Its unique systematic presentation enables them to

concentrate their energies upon each problem they are likely to encounter in the course of their study.

Related Literature

There are several well-known books of musical excerpts that oboists regularly consult. Excerpt books

are commonly utilized as a way to prepare for orchestral auditions or studio classes. Among them are

the Vade-Mecum of the Oboist, by Albert J. Andraud,1 the Orchestral Excerpts for Oboe with Piano

Accompaniment, by John Ferrillo,2 Orchestral Studies, 990 Difficult Passages from the Symphonic

Repertoire, by Evelyn Rothwell,3 and 20th Century Orchestral Studies, by John De Lancie.4 Only the Ferrillo

1 Albert J. Andraud, Vade-Mecum of the Oboist: 230 Selected Technical and Orchestral Studies for Oboe and English Horn, 9th ed. (San Antonio, Texas: Southern Music Company, 1958). 2 John Ferrillo, Orchestral Studies for Oboe with Piano Accompaniment (King of Prussia, PA: Theodore Presser Co., 2006). 3 Evelyn Rothwell, 990 Difficult Passages from the Symphonic Repertoire for Oboe and Cor Anglais (London: Hawkes & Son Ltd., 1953). 4 John De Lancie, 20th Century Orchestral Studies for Oboe and English Horn (New York: Schirmer Inc., 1973).

3

and De Lancie books are annotated with suggestions for working on particular excerpts. Ferrillo’s book

provides strategies with the stated goal of winning an audition. It presents practical advice, along with

useful tempo markings, and it contains simplified exercises for some of the ornamented and

rhythmically challenging excerpts. John De Lancie’s book is limited to excerpts from the twentieth

century. The annotations he provides are brief, and many excerpts contain no annotations at all. The

renowned American oboist John Mack released an audio recording that teaches oboe orchestral

excerpts.5 This is a valuable resource for any oboist and provides practical advice on how to approach

excerpts that often appear on oboe audition lists.

There are several dissertations concerning the use of excerpts for technical and musical practice.

Travis Andrew Bennett wrote his dissertation as a complete guide for horn. It addresses twenty-four

playing challenges. They include changing time signatures, breathing, endurance, technique, phrasing,

slurring into the low register, and intonation, among others.6 His guide is organized by technical and

musical challenges, and uses etudes, solo horn works, and orchestral excerpts chosen to demonstrate

problems inherent in each issue. It was inspired in part by Kristin Thelander’s 1994 article in The Horn

Call.7 This article offered practical solutions to playing challenges using excerpts from horn repertoire. In

Bennett’s dissertation, every chapter begins with remarks about an individual challenge. The chapter is

then structured around selected excerpts. Bennett’s dissertation has been a great inspiration for my

guide. I have utilized some of his insights where they apply to both the horn and oboe, and I am much

indebted to him for his overall concept of systematic instruction.

5 John Mack, Orchestral Excerpts for Oboe with Spoken Commentary, Summit Records DCD 160, 1994, CD. 6 Travis Andrew Bennett, “A Horn Player’s Guide: Using Etudes, Solos and Orchestral Excerpts to Address Specific Technical and Musical Challenges” (D.M.A. diss., University of Alabama, 2003). 7 Kristin Thelander, “Selected Etudes and Exercises for Specialized Practice,” The Horn Call XXIV, no. 3 (May, 1994): 53-59.

4

Shen Wang’s dissertation focuses on basic preparation for oboe auditions using selected excerpts.8

Like Ferrillo, Wang addresses excerpt preparation with the intention of winning an oboe audition. It

points to several specific impediments oboists commonly face, and suggests excerpts to use for

overcoming them. Wang’s dissertation is comprised of four parts. Part one addresses the purpose of the

study, methodology, and review of literature. Part two focuses on technical preparation for fast-moving

passages, rapid tonguing, note releases, and melodic passages. Part three addresses performance

internalization for melodic and fast-moving passages. The final part focuses on reed preparation for an

audition. Although there are several useful exercises for mastering fast-moving and melodic passages,

the document does not supply a comprehensive list of playing challenges. It presents useful solutions to

only five musical problems. This guide, on the other hand, presents several excerpts and solutions for

eighteen technical and musical challenges.

Addressing performance difficulties through excerpts and solo repertoire is valuable to both oboe

students and their teachers. Young oboists can utilize this approach, which exposes them to orchestral

excerpts and solo literature while they are actually working on specific playing challenges. It also

provides appropriate excerpts for teachers to suggest to their students when they are targeting areas

that need improvement. As Travis Bennett’s dissertation has provided horn players with a useful

pedagogical resource, I hope this guide will be equally valuable to oboists.

Methodology and Limitations

This document substantially follows a methodology similar to that outlined in Travis Andrew

Bennett’s dissertation. I first identified specific playing difficulties that I wanted to include in this

document. Some of the playing challenges were selected from Bennett’s dissertation. I also included

8 Shen Wang. “Basic Preparation for Oboe Auditions by Using Selected Oboe Excerpts” (D.M.A. diss., University of Miami, 2009).

5

several of the oboe challenges that Shen Wang wrote about in his dissertation (rapid tonguing, extreme

register, melodic passage phrasing). In order to develop a more comprehensive list, I consulted books

like The Art of Oboe Playing9 and Oboe Secrets: 75 Performance Strategies for the Advanced Oboist and

English Horn Player.10 I also consulted my primary oboe teacher, Dr. Andrew Parker, and other expert

oboists to see what performance problems they suggest that I include. Although there are countless

playing challenges for musicians, I have limited my document to those most commonly confronted by

college oboists. My comprehensive list addresses a variety of technical and musical difficulties, including

the following:

I. Reinforcing Basic Oboe Techniques II. Intonation

III. Half-Hole Technique IV. Rapid Tonguing V. Dynamic Shaping Over Long Phrases

VI. Endurance VII. Mastering Left F

VIII. Voicing Intervals Throughout the Range IX. Gaining Proficiency in the Extreme High Register X. Gaining Proficiency in the Low Register

XI. Smooth Descending Slurs XII. Developing an Awareness of Contextual Playing

XIII. Ornamentation XIV. Playing Extremely Softly XV. Care of Note and Phrase Endings

XVI. Developing Technical Proficiency XVII. Rubato

XVIII. Little Finger Technique XIX. Dotted Rhythm Precision

For each technical and performance issue, I selected excerpts from standard solo and orchestral

repertoire. I used the oboe excerpt books by John Ferrillo, Evelyn Rothwell, John De Lancie and Albert J.

Andraud (cited above) to find excerpts that particularly apply to each challenge. In addition, I chose

relevant portions from standard solo oboe literature. Many of the solo excerpts are ones with which I

9 Robert Sprenkle and David Ledet, The Art of Oboe Playing (Evanston, IL: Summy-Birchard Company, 1961). 10 Jacqueline LeClaire, Oboe Secrets: 75 Performance Strategies for the Advanced Oboist and English Horn Player (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press Inc., 2013).

6

have struggled in the course of my studies. I have chosen each excerpt to target clearly the playing

challenge indicated in the chapter heading.

Two orchestral excerpts and one passage from solo oboe literature were selected for each chapter.

They are annotated with instructions geared to specific technical and musical difficulties. Occasionally,

these instructions are supplemented with references to other oboe works, which can be used by the

student for further study. Each chapter supplies excerpts of varying difficulty, to accommodate different

playing levels. This guide deliberately limits its scope to the solo and orchestral passages that present

technical and musical challenges commonly encountered by oboists at the college level, but it also

provides more challenging excerpts to students at the graduate level. However, it does not include

etudes, although in some chapters I have suggested the benefit of certain etudes for confronting a

particular problem. My goal in writing this guide is twofold: to give aspiring oboists a task-specific tool to

use as they struggle with musical and technical impediments, and, at the same time, to familiarize them

with orchestral and solo oboe repertoire.

7

Chapter I : Reinforcing Basic Oboe Techniques

This guide is intended for students with a general understanding of oboe techniques. The student

should already have proficiency with oboe tone production, fingerings, and reed adjustment.

Periodically reinforcing oboe fundamentals can correct bad playing habits that may have manifested

without the student realizing it. This guide is not a substitute for training with a master oboist. A private

teacher is required for introducing the student to the fundamentals of oboe reed making and

adjustment.

“Crowing” the Reed

The reed is the voice box of the oboe. “Crowing” the reed alone can reveal information on how the

oboe will sound after the reed is inserted. To “crow” the reed, position the lips just above the string and

gently increase the air speed until the reed makes a noise. With a little more air pressure, a balanced

reed should simultaneously produce another pitch an octave lower. At least two distinct pitches in

octaves should be audible, C5 and C6 or C#5 and C#6.1 A tuner will determine what pitch is being

sounded. An ideal reed will crow Cs that are at least five cents sharp (in balanced octaves), or C#s. A

reed that crows flat Cs or Bs will not be in tune throughout the full range of the instrument. Although

the student can adjust the embouchure on flat reeds to force the pitch up, it invariably leads to bad

habits such as biting and overexertion, especially in the upper range of the instrument (above A5). Many

young students “peep” their reeds (produce a high pitched sound on the tip of the reed) before inserting

it into the instrument, which should not be confused with “crowing.” Playing at the tip of the reed alone

may reveal if the reed is responsive but does not exhibit if the reed is balanced or if will play with proper

intonation.

1 Pitch notation and the full octave range of the oboe is provided in Table 1, on page ix.

8

The Embouchure

The oboe embouchure must remain round (with the teeth apart) for good tone production. To form

the embouchure, the lower blade of the reed is placed on the lower lip (in the general area where the

upper lip touches the lower lip when the mouth is closed). The lower lip is then rolled over the lower

teeth, causing the tip of the reed to be gathered into the mouth. The upper lip is simultaneously

stretched over the upper teeth, providing a cushion for the top blade of the reed. The corners of the

mouth (where the upper lips meet the lower lips) should also be gathered inward toward the reed.

Forming the lips to say the first syllable in the word “O-boe” demonstrates the proper embouchure

shape. A round embouchure keeps the teeth apart within the oral cavity, preventing biting. The lips

should surround the reed, providing an airtight seal. Each oboist’s physiology is different. Slight

adjustments must be made by the individual to facilitate a comfortable playing position. Embouchure

muscles require exercise through regular practice to maintain their strength. If the embouchure muscles

are not in good physical shape the student may unconsciously rely on biting the reed to maintain

control, which will lead to bad intonation and tone production. Biting the reed also interferes with the

strengthening of the muscles surrounding the corners of the mouth, preventing a round embouchure.

Supporting the Air Stream

The oboe also requires a fast and focused air stream to produce a good tone and proper intonation.

The air must be supported lower in the body with the “core” or abdominal muscles. These are the same

muscles that contract when coughing. When taking a breath, the lungs and the core muscles below the

ribs should expand. This gives the appearance of the stomach expanding outward. One exercise the

student can employ to perceive which muscles should support the air stream is to take a deep inhalation

through the nostrils with the mouth closed. With both hands placed near the navel, the oboist should

feel the stomach expand outward. With the stomach expanded the student should then cough, thereby

9

contracting the correct muscle group that will be engaged when supporting the air stream during oboe

playing. The core muscles remain solid and contracted while playing to achieve a well-supported air

stream. By relegating all support to the core of the body, the neck, shoulders and arms can remain free

of tension.

Adjusting the Embouchure from the Low to High Range

Playing the oboe requires some flexibility of reed placement within the embouchure to achieve

proper intonation when moving throughout the range of the instrument. If the student remains fixed

without adjusting the reed position while moving throughout the oboe’s range, the intonation and tone

quality will be poor. The famous twentieth century oboist Leon Goossens stressed that a variation in

“lip-pressure”2 was necessary for dynamic variation and to play in the oboe’s different registers. In

describing “lip-pressure” he said: “I do not mean biting the lip, but simply increasing the firmness of the

lips against the reed according to the dynamics and register which create extremes of response from the

instrument; i.e. the lowest notes require the least lip pressure, while the highest require the most.”3 The

oboe’s lower range (A#3 to D#4) requires less reed in the mouth and less “lip-pressure” on the reed. The

middle range (E4 to G#5) requires slightly more reed in the mouth with increased embouchure firmness.

The highest range (A5 and above) requires the reed to move even further into the mouth and for the

speed of the air stream to be increased to achieve good intonation. One exercise to improve intonation

in the upper register is to play A4 into a tuner while slurring up to A5 (without biting). The air speed and

embouchure firmness should be increased when slurring up the octave, and slightly more reed should

enter the mouth to ensure the A5 is in tune.

2 Leon Goossens and Edwin Roxburgh, Yehudi Menuhin Music Guides: Oboe (New York: Schirmer Books, 1977), 57. 3 Goossens, Oboe, 57.

10

Chapter II : Intonation

Intonation is arguably one of the most important aspects of oboe playing. To achieve good

intonation an oboist must be flexible and know the intonation tendencies of the instrument. Flexibility

in the embouchure is needed to slightly roll more reed into the mouth as the player ascends into the

upper register. If no adjustment is made by rolling in, the oboe’s upper register will be flat. Conversely,

as the oboist goes from high to low, the reed should be slightly withdrawn from the oral cavity to

achieve proper intonation. Being in tune is also contextual, depending on the note’s place within a chord

and the pitch center of the surrounding musicians. Since the oboist is responsible for providing the

tuning pitch for most American orchestras at A=440 Hz., it is important to develop practice habits that

maintain intonation at that pitch.

The first factor to consider in successfully playing in tune is to have a working instrument and a

responsive reed that is up to pitch. One can objectively deduce whether the reed will play in tune

without even trying it in the instrument by “crowing” it.1 Playing on reeds that crow flat will force the

oboist to bite to force the pitch up. This can lead to bad embouchure habits that can potentially

interfere with the ability to play with good intonation throughout the oboe’s range. This habit can also

result in a restrictive tone that actually causes the student to play sharp on many notes. Squeezing the

reed closed with the embouchure can force the pitch to rise above the A=440 Hz. level. Many young

students are so accustomed to playing on flat reeds that they become accustomed to playing certain

notes on the oboe sharp. The notes on the oboe that are notoriously sharp are half-hole C#, half-hole D,

E and F# (C#5, D5, E5 and F#5).2 Flat notes on the oboe include the second octave A and low C# (A5 and

C#4).3

1 For instructions on “crowing” the reed see Chapter 1. 2 Leon Goossens and Edwin Roxburgh, Yehudi Menuhin Music Guides: Oboe (New York: Schirmer Books, 1977), 89. 3 Robert Sprenkle, and David Ledet, The Art of Oboe Playing (Evanston, IL: Summy-Birchard Company, 1961), 17.

11

When playing with other musicians, it is also important to have an awareness of the key in which the

ensemble is playing in order to play contextually and with “just intonation.” Just intonation is defined as

“A system of intonation and tuning in which all the intervals are derived from the natural (pure) fifth and

the natural (pure) third.”4 For example, if the oboist is playing the third of a major chord it is necessary

to play that note somewhat flat to sound in tune to the human ear. It has been shown that major thirds

should be lowered by thirteen cents (thirteen percent of a half step) to achieve just intonation.5

Conversely, if the oboist has the fifth of the chord they may have to play slightly sharp. The root of the

chord should be as close to correct equal temperament as possible, but one must always defer to the

pitch center of the surrounding musicians. Thus, musicians who play into a tuner for every pitch during

rehearsals are often out of tune with the ensemble because they are not considering their place in the

chord or the intonation of other musicians.

When practicing alone, it is advisable to develop good intonation habits by using a tuner and learn

how to keep the pitch consistent with A=440 Hz. A good test for intonation is to practice a phrase that

ends on a half-hole D (D5). Have a tuner on, but don’t look at it right away. Play through the phrase to

the final D5, and glance at the tuner. Many students find that they are at least ten cents sharp on this

note. Another useful exercise is to play D minor arpeggios slowly with a tuner. Pay particular attention

to keeping the D5 low enough, and the A5 high enough.

4 Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music, s.v. “Just intonation.” 5 Christopher Leuba, A Study of Musical Intonation (Vancouver, Canada: Prospect Publications, 1962), 8-10.

12

[Andante ♩ = 84]

EX. II.1 Samuel Barber, Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, movement 2, mm. 1-14.

Copyright © 1942 (Renewed) by G. Schirmer, Inc. (ASCAP) International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission.

This first excerpt from the second movement of Samuel Barber’s Concerto for Violin targets the

exceptionally sharp notes E5, F#5, and the flat A5. This excerpt also tests the player’s endurance.

Although the score marks the tempo at quarter note=84, John Ferrillo suggests the more comfortable

tempo of quarter note=92.6 As oboists tire, the tendency will be to go sharp. Keep the embouchure

open and round when practicing this excerpt especially on the E5, F#5 and G#5. Open the embouchure

by dropping the jaw and stretching the upper lip over the upper teeth, which will cause the nostrils to

stretch into ovals, rather than circles. This will indicate that the teeth are separated to prevent biting,

which can cause the pitch to be sharp. To keep the tone from sagging or spreading, increase the air

speed, focusing the air stream by raising the tongue to allow the embouchure to stay round while

playing with good intonation and focused air. Pay special attention to measure ten. Decrescendo on the

F#5, but be sure to avoid going sharp. Try to decrescendo by gently pushing the reed against the upper

6 Ferrillo, Orchestral Excerpts for Oboe, 26.

13

lip, while still maintaining an open embouchure and focused air. This will help the B5 that follows from

sounding too low. This excerpt can also be used as a good exercise in pacing long phrases dynamically.

EX. II.2 Ludwig Van Beethoven, Symphony no. 7 in A Major, op. 92, movement 1, mm. 1-22.7

This excerpt from the first movement of Beethoven’s Symphony no. 7 begins on an A5, which

requires fast and focused air on a reed that is up to pitch. Use the embouchure to roll a little more reed

into the mouth on second octave notes, and slightly roll a little reed out of the mouth when descending

to the E5 and C#5 that follow. Be sure to keep the pitch down on the half-hole D (D5) in measure 7. This

will ensure the A5 in measure 9 is not flat. A significant challenge in this excerpt lies in the forte-pianos

in measures 1, 3, 5, and 7. The note must be accented with fast air and then the diminuendo must be

executed suddenly, without letting the pitch rise. To achieve a pianissimo dynamic without biting the

reed or lessening the air stream, try to keep the air moving fast, and slightly push the reed against the

upper lip as a dampener to the sound. This leaves the bottom blade free to vibrate, but keeps the pitch

stable and allows for a soft dynamic. To practice playing softly and in tune, try to engage more of the

upper lip of the embouchure for volume control.

7 Ludwig Van Beethoven, Symphony no. 7 in A Major, op. 92, (New York: Edwin F. Kalmus, 1933), Petrucci Music Library, International Music Score Library Project. Accessed March 7, 2016, http://conquest.imslp.info/files/imglnks/usimg/9/94/IMSLP36607-PMLP01600-Beethoven-Op092.Oboe.pdf

14

[Larghetto ♩ = 76-80]

EX. II.3 Vincenzo Bellini, Concerto in E-Flat Major, movement 1, mm. 1-38.8

This excerpt from Bellini’s Concerto in E-flat Major requires oboists to keep their pitch down as

they tire. Special attention should be paid to the E-flat major triad in the first measure. If the excerpt

8 Vincenzo Bellini, Concerto in E-Flat Major, (Alexander Gagarinov: Creative Commons, 2011) Petrucci Music Library, International Music Score Library Project. Accessed March 7, 2016, http://burrito.whatbox.ca:15263/imglnks/usimg/5/5c/IMSLP90841-PMLP85653-Bellini_-_Oboe_Concerto_Big_Orchestra_-_Oboe_Solo_-_2011-01-21_1343.pdf

15

does not begin with good intonation the rest of the movement will continue with poor intonation. Much

of the first movement is in the higher range of the instrument, causing us to play with more reed in the

mouth. It is important to be flexible and pull more reed out of the mouth while descending; otherwise,

the lower notes will have a tendency to be sharp. An example of this can be found in measures 31-33.

Pay particular attention to the half-hole D (D5) to C5 in measure 29. The D5 will have a tendency to be

sharp as a result of fatigue. The C5 may sound too flat if the D5 is sharp.

16

Chapter III : Half-Hole Technique

Half-hole notes on the oboe can present difficulties when playing highly technical passages. The

half-hole notes on the oboe include C#5, D5 and D#5. As Mark Weiger wrote in Teaching Woodwinds,

“The half-hole is the first technical difficulty the young oboists encounter and, unfortunately, usually the

last thing they learn to do well.”1 Difficulties with the half-hole are not limited to beginning oboists.

Many advanced players continue to struggle with clean half-hole technique. Scales and arpeggios may

aid in developing half-hole technique, but a critical ear is mandatory. Half-hole technique is easy to gloss

over and difficulties may not be addressed for years. The main problem with the half-hole is that the

player does not uncover the hole in time, thereby sounding the lower octave, or sounding an unclear

pitch. The pitch of the note may sound in the correct octave, but the clarity of the note is not achieved.

This can fool the player into believing that success has been achieved, but it rarely fools an audition

committee. A critical ear is essential to distinguish whether clarity has been achieved on the half-hole

notes when practicing the following excerpts.

A useful exercise for strengthening half-hole technique was written by Jacqueline LeClaire in her

book Oboe Secrets: 75 Performance Strategies for the Advanced Oboist and English Horn Player. She

suggests writing an etude in quarter notes that alternates between a half-hole high D to non-half-hole

notes throughout the range. With a metronome set to 52, she suggests pivoting the left index finger off

the half-hole one sixteenth note before the other fingers move.2 Moving the left index finger early

affords the advantage of not moving late when returning to playing the half-hole notes in time.

1 Mark Weiger, Jerry Kirkbride, Hal Ott, and Craig Whittacker, Teaching Woodwinds: A Method and Resource for Music Educators, ed. William Dietz (Boston: Schirmer Books, 1998), 271. 2 LeClaire, Oboe Secrets, 40.

17

[Vif ♩. = 92]

EX. III.1 Maurice Ravel, Le Tombeau de Couperin, movement 1, mm. 1-22.3

The opening of Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin challenges the player to exhibit proficient half-hole

technique, particularly in measures 5-9. This excerpt is also useful for developing fluidity in the low

register and rhythmic accuracy when incorporating ornamentation. Use a well-supported air stream to

reinforce the dynamic swell of the phrases. Begin playing this excerpt extremely slowly, paying particular

attention to the alternation between half-hole notes and non-half-hole notes in measures 5-9. Try

playing these measures as slow quarter notes, implementing LeClaire’s strategy of moving off the half-

3 Maurice Ravel, Le Tombeau de Couperin, (Paris: Durand, 1919), Petrucci Music Library, International Music Score Library Project. Accessed March 7, 2016, http://hz.imslp.info/files/imglnks/usimg/8/88/IMSLP48031-PMLP80671-Ravel-Tombeau.Oboe.pdf

18

hole notes one sixteenth note early. After mastering this technique, increase the tempo. Students

should keep their attention focused on maintaining fluid finger movements with no tension.

[Andante sostenuto ♩ = 58-60]

EX. III.2 Johannes Brahms, Symphony no. 1 in C Minor, op. 68, movement 2, mm. 35-49.4

This excerpt from Brahms’ Symphony no. 1 is particularly useful since its slower tempo facilitates

careful listening for the fluidity of half-hole note alternations. This excerpt can also be utilized for

developing control of the left hand little finger. As in the Ravel excerpt above, use a focused air stream

to retain intensity through the whole phrase. Focus on achieving a smooth alternation between the B#4

and D#5. Keep the fingers close to the instrument when playing the B#4s. Pay particular attention to

moving the left hand index finger a fraction of a second before bringing the rest of the fingers smoothly

down for the half-hole notes in the excerpt. No sixteenth note should stand out from the texture. Work

on smooth and even phrasing, concentrating on uniformity of sound between more open notes and

covered notes.

4 Johannes Brahms, Symphony no. 1 in C Minor, op. 68, (New York: Edwin F. Kalmus, 1933), Petrucci Music Library, International Music Score Library Project. Accessed March 7, 2016, http://burrito.whatbox.ca:15263/imglnks/usimg/7/7d/IMSLP37946-PMLP01662-Brahms-Op068.Oboe.pdf

19

[Molto allegro ♩ = 138-144]

EX. III.3 Camille Saint-Saëns, Sonata for Oboe and Piano, op. 166, movement 3, mm. 57-73.5

The third movement of the Saint-Saëns Sonata for Oboe and Piano contains a rather difficult phrase

that tests the clarity of the oboist’s half-hole technique. In addition to providing an opportunity to

develop half-hole technique, this excerpt challenges the player to develop technical proficiency with the

left F key. Practice this excerpt slowly. It is beneficial to invent various rhythms to develop technical

proficiency. For example, play the first note in each group of four sixteenth notes as an eighth note

followed by three sixteenths. Next play a sixteenth-eighth-sixteenth-sixteenth for each group of four

sixteenths notes. Then play a sixteenth-sixteenth-eighth-sixteenth, and so on. This will give oboists a

chance to carefully listen for the clarity of the half-hole notes within the passage. As in excerpts III.1 and

III.2, pay particular attention to the left hand index finger. Do not allow the finger to be sluggish; it

should feel as if the left index finger is anticipating movement before the other fingers.

5 Camille Saint-Saëns, Sonata for Oboe and Piano, op. 166, (Paris: Durand, 1921), Petrucci Music Library, International Music Score Library Project. Accessed March 7, 2016, http://burrito.whatbox.ca:15263/imglnks/usimg/7/74/IMSLP71557-PMLP14974-Saint-Saens_Sonate_Op_166_Durand_Oboe_scan.pdf

20

Chapter IV : Rapid Tonguing

A flexible reed is vital to articulating fast passages. If the reed is unresponsive, playing will take more

physical effort and the tongue will slow down. If the reed is unresponsive, check to see if the very tip

(the last 1/2mm) is as thin as possible. After inserting a plaque in the reed, the knife should not make a

clicking sound as it glides over the very tip of the reed onto the plaque. Excessive wood in the “corners”

of the reed (the sides of the reed where the tip is separated from the heart), will also create difficulties

with articulation.1 Assuming the reed is free enough and in good working order, rapid passages are an

exercise in coordination.

Difficulties in playing an excerpt such as Rossini’s La Scala di Seta (EX. IV.1) often result from a lack

of coordination between the fingers and tongue. The remedy for this is extremely slow practice.

Maintain a well-supported air stream. Relax and use a smooth legato articulation. Play with expressive

dynamics over the phrases. This will ensure that when the tempo is increased, the phrasing will be built

into the excerpt.

Instead of conceptualizing the following excerpts as rapid tongue exercises, think of them as rapid

releases. To “tongue” the reed implies that the tongue is aggressively thudding against the reed. In

actuality, the tongue should gently lift from the reed, allowing the supported air to flow freely through

the reed. The tongue should be in position on the reed with the air support already flowing to make the

reed sound. Gently lift the tongue from the tip of the reed and lightly replace it to interrupt the air

stream. Try not to block the whole aperture of the reed. Focus on lightly replacing the tongue on the

very edge of the lower blade of the reed.

1 For an illustration of the different parts of an oboe reed refer to Table 2 on page x.

21

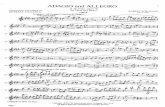

[Allegro = 120-126]

EX. IV.1 Gioacchino Rossini, Overture to La Scala di Seta, mm. 22-56.2

This excerpt is on nearly every orchestral audition because it clearly displays whether the candidate

can articulate swiftly and cleanly throughout the oboe’s range. John Ferrillo suggests learning to double

tongue if the oboist is unable to play the excerpt cleanly at half note=120. He also warns of the tendency

for oboists to rush the repeated notes in measures 39, 40, 48, and 49.3 With a balanced reed, it is

possible to play this excerpt with a single tongue, if it is worked up to tempo slowly. Work on evenness

and not straying from the pulse. Shen Wang suggests singing the last two measures of the violin tutti in

one’s head before beginning the excerpt. This will ensure that the player enters in tempo, and will help

to keep the pulse consistent.4 In measure 44, play the ascending passage with a legato articulation.

When the excerpt is up to tempo it will sound clear and even. There may be a tendency when playing

this excerpt for tension to creep into the upper body. A low, grounded and supported air stream should

be ever present. When descending in the final scale, keep the embouchure round and supported. While

2 Gioacchino Rossini, Overture to La Scala di Seta, (New York: Edwin F. Kalmus, 1937), Petrucci Music Library, International Music Score Library Project. Accessed March 7, 2016, http://petrucci.mus.auth.gr/imglnks/usimg/f/f2/IMSLP50258-PMLP48518-Rossini-La_Scala_di_Seta_oboe-1.pdf 3 Ferrillo, Orchestral Excerpts for Oboe, 73. 4Shen Wang. “Basic Preparation for Oboe Auditions by Using Selected Oboe Excerpts” (D.M.A. essay, University of Miami, 2009), 57.

22

descending, slide the reed out of the embouchure slightly, thereby playing on the tip of the blades with

an open embouchure. This will ensure that the low notes are in tune and speak freely.

[Allegro assai ♩ = 108]

EX. IV.2 Johann Sebastian Bach, Brandenburg Concerto no. 2 in F Major, BWV 1047, movement 3, mm. 79-101.5

Bach’s second Brandenburg Concerto tests the oboist’s ability to articulate at a fast tempo. Instead

of articulated notes that move in stepwise motion as in the previous excerpt, skips of thirds are

scattered throughout. The quarter note should equal about 108, but may be played slightly faster or

slower depending on the conductor's preference. Using the forked F fingering in measures 81 and 82 is

also practical, and will aid in keeping the focus on tongue and finger coordination. Preparation for this

excerpt should also start slow and legato, as with the previous excerpt. The slightest leaning on the

downbeats of measure 81 and 83 will aid in stabilizing the articulated descending fifths. No dynamics are

indicated, but I suggest following the contour of the sequential phrases to add in a steady dynamic

increase to the A5 in measure 87. Think of using the tongue to lightly release the reed throughout this

excerpt, instead of “tonguing it.”

5 Johann Sebastian Bach, Brandenburg Concerto no. 2 in F Major, BWV 1047, (Boca Raton: Edwin F. Kalmus, 1987), Petrucci Music Library, International Music Score Library Project. Accessed March 7, 2016, http://ks.imslp.info/files/imglnks/usimg/8/83/IMSLP37610-PMLP82078-Bach-BWV1047.Oboe.pdf

23

[Agitato ♩. = 152]

EX. IV.3 Benjamin Britten, Six Metamorphoses after Ovid, op. 49, movement 2, “Phaeton,” mm. 26-38.

Six Metamorphoses after Ovid, Op. 49 by Benjamin Britten © Copyright 1952 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission.

The second movement from Britten’s Six Metamorphoses after Ovid is an exercise in rapidly

tonguing a technical passage. Any deviation from a consistent tempo is immediately audible. When

practicing this excerpt, oboists must keep his ear trained on even execution. Start this excerpt extremely

slow and legato, gradually increasing the speed with a metronome. When the tempo of dotted-

quarter=120 is achieved, it is advisable to articulate with a bit more of an aggressive tongue. Always

keep the triplets subdivided when performing this excerpt. Whereas the previous two excerpts call for a

light staccato, this excerpt requires a more aggressive articulation.

24

Chapter V : Dynamic Shaping Over Long Phrases

The ability to pace dynamic levels from soft to loud (or loud to soft) over long phrases is an

invaluable musical skill to develop. Proper phrasing keeps the listener engaged and reinforces the

concept that music is never static but always in motion. Long tone practice is essential for developing

this skill, as are dynamic exercises. One exercise for developing the pacing of dynamics is to set the

metronome to quarter note = 60. Choose a comfortable note such as the tuning A (A4). Play six legato

quarter notes starting pianissimo, piano, mezzo-piano, mezzo-forte, forte and arriving at a true

fortissimo (without the sound spreading) on the sixth count. Re-articulate the fortissimo sixth count, and

count backward, decreasing the volume for each successive note. Next, remove the articulation and

gradually increase the volume over six counts using long tones. After becoming adept with the tuning A

(A4), incorporate other notes throughout the range of the instrument. Pay particular attention to which

notes on the oboe need more work to achieve varied dynamics. This exercise will offer students an

honest assessment of their ability to produce dynamic variation throughout the oboe’s range.

EX. V.1 Long tone exercise

25

Another way to enhance the effect of playing louder or softer lies in the intensity of the vibrato. A

more active vibrato can give the impression that a loud passage is even louder. Conversely, a

nonexistent vibrato can give the impression that a soft passage is even softer. Intensifying vibrato while

getting louder on long tones can aid in expanding the limits of the oboist’s dynamic range. This can be

particularly helpful within the second and third octaves of the oboe.

Each musical phrase is a sentence. It can either be inquisitive or declarative, an antecedent or a

consequent. In every musical sentence there is a peak, or a particular note that is emphasized. The notes

leading to the peak of a phrase should gradually intensify toward the peak, becoming louder or softer,

depending on what the composer has written. Sequential notes in a phrase should rarely be played at

only one dynamic level. The peak of a phrase can be expressed dynamically, with an accent, or with a

variation in the vibrato speed. When looking at an excerpt or solo passage it is important to identify

where the phrases are and where they peak. As in the exercise above, there should be a minute

difference in dynamics and tone color between each sequential note. The following excerpts are useful

for pacing the dynamics of a phrase, arriving at a peak, and then gradually tapering to the phrase’s end.

26

[Tranquillo = 76]

EX. V.2 Richard Strauss, Don Juan, mm. 232-314.

Copyright © 1889 by Josef Albi Musikverlag. Copyright © 1932 by C.F. Peters Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by permission.

This excerpt clearly illustrates where to incorporate dynamic variation over long phrases. Some

possible pitfalls of this excerpt include peaking dynamically too early, and dragging the tempo. When

attempting to play more expressively, guard against unconsciously slowing the tempo. Begin practicing

this excerpt with a metronome to keep the pulse consistent. The first phrase of the excerpt (from

rehearsal letter “L” to four measures before rehearsal letter “M”) should be played softer than the

second (one measure before rehearsal letter “M” to the eighth measure of rehearsal letter “M”). One

way to illustrate a softer tone color on the oboe is to use a less active vibrato. Ferrillo suggests to not

“push your luck” with too quiet an entrance on the initial D4.1 Keep enough reed out of the embouchure

1 Ferrillo, Orchestral Excerpts for Oboe,78.

27

and avoid biting the aperture of the reed while attempting a softer dynamic. It is acceptable to begin the

excerpt at a mezzo-piano dynamic. Disguise the volume of the initial mezzo-piano D4 with a less active

vibrato. The first phrase should climax to a healthy mezzo-forte dynamic level on the downbeat of the

fifteenth measure of rehearsal letter “L.” In order to get the climactic B5 to project more (in the

fifteenth measure of rehearsal letter “M”), increase the speed of the vibrato gradually. A useful fingering

to achieve a more projective B5 is to add the low C-key and the low B-key to the standard B5 fingering.

Avoid allowing the phrase to peak dynamically before the B5 in the fifteenth measure of rehearsal letter

“M.”

[Poco Andante ♪ = 108]

EX. V.3 Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony no. 3 in E-Flat Major, op. 55, “Eroica,” movement 4, mm. 339-382.2

Beethoven offered clear dynamic markings to illustrate how to phrase this excerpt. The downbeat of

measure 356 is the peak of the phrase and should be set up by a gradual crescendo and an increase in

vibrato on the two B♭5s that precede it. The entire excerpt should be executed in one breath to keep

the phrase uninterrupted. It was John Mack’s view that if a breath were to be taken in measure 356, it

2 Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No.3 in E-Flat Major, op. 55, “Eroica,” (New York: Edwin F. Kalmus, 1933), Petrucci Music Library, International Music Score Library Project. Accessed March 7, 2016, http://burrito.whatbox.ca:15263/imglnks/usimg/5/5b/IMSLP35366-PMLP02581-Beethoven-Op055.Oboe.pdf

28

would ruin the effect of the phrase’s diminuendo to measure 357. Mack also advised that the crescendo-

decrescendo in measure 358 is typical of Beethoven, and should reach its dynamic peak by the second

eighth-note pulse.3

[Adagio ♩ = 58-60]

EX. V.4 Tomaso Albinoni, Concerto for Oboe in D-Minor, op. 9, no. 2, movement 2, mm. 17-34.

The first portion of this excerpt can be broken into two separate five measure phrases (measures

17-21 and the anacrusis to measure 22-26). Each phrase increases in volume and intensity of vibrato and

peaks in the third measure. After the peak of each phrase in the third measure, gradually decrescendo to

the fifth measure, ending each phrase at a pianissimo dynamic. To pace each phrase, it may be helpful

to subdivide into eighth notes. Gradually increase (or decrease) the volume with each eighth-note pulse.

Beginning with the anacrusis to measure 27, there are two separate four measure phrases (the anacrusis

to measure 27-30, and measures 31-34). Measure 27-30 is an antecedent (or question) phrase, and

3 John Mack, Orchestral Excerpts for Oboe with Spoken Commentary, Summit Records DCD 160, 1994, CD.

29

measure 31-34 is a consequent (or answer) phrase. The antecedent phrase should be played at a softer

dynamic level, and the consequent phrase should be played more assertively.

30

Chapter VI : Endurance

Endurance issues can be overcome with a combination of muscle training through daily practice and

breathing strategies. The following orchestral excerpts can be incorporated into a daily practice regimen

to strengthen the embouchure. When targeting endurance issues, select a reed that is stable and

flexible. Playing on reeds that are too resistant often results in difficulties with endurance. When

practicing the following excerpts, students should stop immediately if they find they are biting the reed

as a result of tiring. Biting the reed leads to bad embouchure habits that will interfere with other aspects

of oboe playing. If students are unable to play through the following orchestral excerpts, they should

wait until they have adequately strengthened their embouchure through daily practice before

attempting the Strauss Oboe Concerto excerpt (VI.3.) Jacqueline LeClaire called oboe playing an “athletic

endeavor.” She explained that muscles in the embouchure are very small, thus they can gain in strength

rather quickly. Conversely, embouchure muscles also lose strength rapidly without regular practice.1

Playing long, taxing phrases will bring some embouchure discomfort, and this is not something that

necessarily needs “fixing.” LeClaire advises that ignoring embouchure discomfort and focusing on the

music will help oboists play well.2

Awareness of how the air is supported within the body must also be cultivated. As oboists tire,

muscle tension can manifest in the arms and shoulders in an attempt to maintain control. Keep the air

supported lower in the body by the “core” or abdominal muscles. These are the same muscles that

contract when coughing. By relegating all tension to one’s core, the upper body may remain free from

tension. Guard against any tension that is creeping into the chest, shoulders or neck during practice. If

students begin to feel this sensation, they should stop, take a deep relaxing breath, and take a break for

1 LeClaire, Oboe Secrets, 80. 2 Ibid., 81.

31

a few minutes before returning to the oboe. Extraneous tension in the body exacerbates difficulties with

endurance.

As a result of the small aperture of the reed, oboists often have lungs full of stale air by the time

they reach a place to take a breath. An exhalation of old air is therefore required before an inhalation of

new air. In the following excerpts, there are places where a breath is used for an exhalation only. At first

it may feel unusual to use the breathing place to exhale only, but there will still be enough old air in the

lungs to perform until the next breathing place to inhale. By alternating breathing places with

exhalations and inhalations, endurance can be extended for longer durations.

[♩ = 69-80]

EX. VI.1 Johannes Brahms, Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, op. 77, movement 2, mm 1-45.3

3 Johannes Brahms, Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, op. 77, (New York: Edwin F. Kalmus, 1956), Petrucci Music

Library, International Music Score Library Project. Accessed March 7, 2016, http://ks.imslp.info/files/imglnks/usimg/a/a0/IMSLP43064-PMLP06518-Brahms-Op077.Oboe.pdf

32

This excerpt from the second movement of the Brahms Violin Concerto tests the oboist’s endurance

and intonation. Do not allow the tempo of this excerpt to gradually slow, as this can lead to tiring. One

way to prevent dragging is to set the metronome to sound once per measure (half-note = 35-40). Ferrillo

suggests keeping the tempo moving to preserve the basic architecture of the excerpt.4 This facilitates

the use of rubato at the ends of phrases, which will aid in endurance.

In devising a breathing strategy, Ferrillo suggests, “Exhale on the downbeat of measure 9 and inhale

on the sixteenth rest after it, or exhale on the sixteenth rest and inhale just before the down beat of

measure 11. There are comparable points for breathing after the first eighth note in measure 24 and on

the following downbeat.5 Keep the embouchure round for the C6 in measure 11 to prevent biting. Biting

may give a false sense of endurance, but it does not strengthen the embouchure muscles and leads to

other performance problems.

4 Ferrillo, Orchestral Excerpts for Oboe, 43. 5 Ibid., 43.

33

[Aria ♪= 80-88]

EX. VI.2 Johann Sebastian Bach, Cantata no. 82, Ich Habe Genug, BWV 82, movement 1, mm. 1-37.6

This famous cantata by Bach presents long phrases without indicated rests for breathing. It tests the

oboist’s ability to maintain embouchure control. Breaths may be taken after tied notes as needed (such

as the downbeat of measure 19). Alternating inhalations and exhalations will aid in endurance by ridding

the lungs of old air. A deep inhalation can be taken in measure 7. Use the downbeat of measure 15 to

exhale some of the old air. Another inhalation can then be taken on the down beat of measure 19. Take

full advantage of the two eighth rests in measure 24. Exhale during the first eighth rest and inhale a

breath during the second. This should allow the oboist to complete the excerpt with enough endurance.

6 Johann Sebastian Bach, Cantata no. 82, Ich Habe Genug, BWV 82, (Markus Müller: Creative Commons, 2014), Petrucci Music Library, International Music Score Library Project. Accessed March 7, 2016, http://burrito.whatbox.ca:15263/imglnks/usimg/4/44/IMSLP315137-PMLP149584-BWV82Oboe.pdf

35

EX. VI.3 Richard Strauss, Concerto for Oboe and Small Orchestra, movement 1, mm. 1-73.

Oboe Concerto by Richard Strauss © Copyright 1947, 1948 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. U.S. Copyright Renewed. Reprinted by permission.

The exposition of the Strauss Oboe Concerto is a challenging test of endurance. Maintaining enough

energy to complete the exposition requires that the embouchure muscles are in excellent shape. When

first attempting this excerpt, break it into smaller sections to aid in strengthening endurance and

technique. Be on guard for elevated tension in the hands and shoulders. Once each section is played

with relaxed control, the entire excerpt can be reassembled. As with the previous excerpts, devise a

breathing strategy of inhalations and exhalations. As in Bach’s Ich Habe Genug (EX. VI.2), breathing may

occur after tied notes, as needed.

33

36

39

43

47

50

55

36

Oboists should beware of expending all of their stamina on the more resistant notes of the second

and third octaves, such as in measures 6, 8, 16 and 43. The first crescendo is not indicated until measure

24, so play the opening of the solo at a softer dynamic to conserve energy. The first breath can be taken

in measure 10. If needed, another breath can also be taken in measure 14 after the F5. Place a slight

ritardando in measure 22, to allow time for an exhalation and inhalation at the end of the measure.

Begin the next phrase in measure 23 a tempo. A quick exhalation and inhalation can occur at the end of

measure 26 to set up the subito piano in measure 27. Breaths can then be taken in measure 30 and 33

after each first quarter note. Use measure 33 to exhale and measure 34 to inhale after the quarter

notes. This will ensure the oboist has enough energy for the leap to the D6 in measure 35. An exhalation

can occur on the third beat of measure 37, with an inhalation on the second beat of measure 38. Take

full advantage of the eighth rests in measure 40. Use the first eighth rest to exhale and the second to

inhale. Utilize measure 43 to exhale after the dotted half note, with two deep inhalations in measure 44.

In measures 47 to 50, break the ties before triplets when necessary for breaths. From measure 51 to 59,

delay the crescendo to the C#6 in measure 56 to conserve energy. Take full advantage of the sustained

B♭5 in measure 54 to take a final breath.

37

Chapter VII : Mastering Left F

A full conservatory model oboe has three separate fingerings for F (F4 or F5). They are the “right F,”

the “forked F,” and the “left F.” Many young oboists begin playing on instruments that do not include a

left F key. This may present later technical challenges when upgrading to a professional oboe. Without

the aid of a left F key the student often learns to rely on the forked F fingering. The forked F generally

has a “stuffier” tone color when compared to the right F or left F fingering.1 The left F was designed to

offer a more uniform tone color whenever a player is approaching from the half-hole notes to F (or visa-

versa). There are oboists who use the left F to an excessive degree, and completely reject the use of

forked F under any circumstance. Jaqueline LeClaire observed that if oboists are struggling to play

cleanly because of an avoidance to forked F, where the use of the forked F would not be detrimental to

a performance, then forked F is acceptable.2

The tone color of forked F can sound out of context in melodic passages where a right F was

sounded shortly before the forked F. An example of this can be seen in the following excerpt from

Tchaikovsky’s Symphony no. 4. The beginning of the excerpt starts with two right Fs in measure 2. In

measure 6, it is extremely awkward to slide from D♭ to a right F fingering. A player unused to left F

might be tempted to play the easier forked F. The problem with this approach is that on most oboes

there will be an audible tone color change between the forked F and the Fs played in measure 2.

In addition to regular practice of the following excerpts, one way to overcome the avoidance of left

F is to create an etude for daily practice. Alternate from the half-hole notes C#, D, and D# to left F,

rearticulate the left F and then play the reverse. Try the same exercise an octave lower starting with C#4

below the staff. With daily practice, left F technique can be mastered rather quickly.

1 LeClaire, Oboe Secrets, 94. 2 Ibid., 94.

38

[♩ = 58-63]

EX. VII.1 Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky, Symphony no. 4 in F Minor, op. 36, movement 2, mm. 1-46.3

The excerpt from Tchaikovsky’s fourth symphony can be used to gain mastery of alternating

between the right F and left F fingerings. John Mack observed that F4 to F5 encompasses the range of

this solo.4 The left F key should be used for the F5s in measures 6, 15, and 20. This will ensure that they

match the right F keys that are used in measures 2, 5, 10, 13 and 14. Take special note of measures 14

and 15 in which two successive right Fs must be followed with a left F. This is mirrored by the two

successive right E♭5s followed by a left E♭5 in measures 16 and 17. In measure 15, after moving from

the left F5 to the right E♭5, replace the right E♭ fingering with the left E♭ fingering. This will free the right

little finger to sound the following D♭5. Try to make the E♭ fingering alternation as inaudible as possible.

This same E♭5 fingering switch occurs in measures 19 and 20.

3 Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky, Symphony no. 4 in F-Minor, op. 36, (New York: Edwin F. Kalmus, 1960), Petrucci Music Library, International Music Score Library Project. Accessed March 7, 2016, http://ks.imslp.info/files/imglnks/usimg/f/f6/IMSLP38504-PMLP02735-Tchaikovsky-Op36.Oboe.pdf 4 John Mack, Orchestral Excerpts for Oboe with Spoken Commentary, Summit Records DCD 160, 1994, CD.

39

[Scherzo = 116]

EX. VII.2 Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony no. 3 in E-Flat Major, op. 55, “Eroica,” movement 3, mm. 203-258.5

This passage from the third movement of Beethoven’s Symphony no. 3 begins with the left F5

fingering (measure 211) to facilitate the following D5, a half hole note. All of the Fs in this excerpt should

be played with the left F fingering since they are followed by half-hole notes. This excerpt must be

played smoothly, without any particular note projecting out of the texture. F5 is a note on the oboe that

can project more when compared to the surrounding notes in this passage. Adjust the volume of the left

F5s to sound in correct dynamic context with the notes that surround them. To facilitate this, John Mack

emphasized using good support, not by “blowing hard,” but by firmly holding the air so that the varying

degrees of resistance of the notes in the passage do not create technical issues.6 For instruction on

supporting the air stream see Chapter 1.

5 Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No.3 in E-Flat Major, op. 55, “Eroica,” (New York: Edwin F. Kalmus, 1933), Petrucci Music Library, International Music Score Library Project. Accessed March 7, 2016, http://burrito.whatbox.ca:15263/imglnks/usimg/5/5b/IMSLP35366-PMLP02581-Beethoven-Op055.Oboe.pdf 6 John Mack, Orchestral Excerpts for Oboe with Spoken Commentary, Summit Records DCD 160, 1994, CD.

40

EX. VII.3 Benedetto Marcello, Concerto for Oboe in C Minor, movement 2, mm. 1-14.

The excerpt from the second movement of Marcello’s Oboe Concerto in C Minor incorporates the

use of left F, right F and forked F. The slow tempo requires the use of left F on the longer melodic notes

following the half-hole notes. In measure 6, after playing the D5, the left F should be used. In the faster

moving florid passages it is acceptable to use the forked F fingering to facilitate ease of technique, such

as in measure 10. However, the final F5 in measure 10 should be played with the left F fingering because

it is sustained. Measure 11 contains three F5s. The first should be played forked for ease of technique,