Osteopathic medical students' beliefs about osteopathic manipulative treatment at 4 colleges of...

Transcript of Osteopathic medical students' beliefs about osteopathic manipulative treatment at 4 colleges of...

JAOA • Vol 111 • No 11 • November 2011 • 615Draper et al • Medical Education

Context:Osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) is a dis-tinctive and foundational aspect of osteopathic medicine. Sev-eral studies have reported a decline in the use of OMT bypracticing osteopathic physicians, but the reasons for thisdecline have not been fully investigated.

Objective: To investigate osteopathic medical students’ atti-tudes and beliefs regarding osteopathic philosophy, includingOMT.

Methods: A self-administered, 21-item, electronic question-naire developed specifically for the current study was dis-tributed to first- and second-year osteopathic medical stu-dents at 4 colleges of osteopathic medicine. The questionnairecontained items addressing student attitudes toward osteo-pathic philosophy, including OMT; perceptions of osteopathicpredoctoral education; and plans for integrating OMT intofuture practice.

Results:Of 1478 questionnaires sent, 491 students completedthe questionnaire for an overall response rate of 33%. Analysisof student responses revealed that a majority of first- andsecond-year osteopathic medical students (95%-76%,depending on the question asked) expressed agreement withosteopathic philosophy. Students who reported prior exposure

to OMT had higher levels of agreement with osteopathic phi-losophy statements (P<.04) and with the intention to useOMT (P<.02) than students with no prior exposure. However,students who were drawn to an osteopathic medical schoolby the desire to become a physician regardless of degreereported lower levels of agreement with osteopathic philos-ophy and the intention to use OMT. Students’ levels of agree-ment with osteopathic philosophy and intention to use OMTvaried significantly based on the school that they attended,their current year of study, and whether or not they wereparticipating in clinical rotations.

Conclusion: The reason why a student decided to studyosteopathic medicine was strongly associated with the levelof agreement with osteopathic philosophy and the intentionto use OMT in future practice. Prior experience receivingOMT, the medical school that a student attends, and the cur-rent year of study appear to be related to the students’ levelsof agreement with osteopathic philosophy and intention to useOMT. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2011;111(11):615-630

The 4 tenets of osteopathic philosophy have often beencited as the factors that make osteopathic medicine dis-

tinctive.1 These tenets, as stated by the American OsteopathicAssociation,2 are as follows:

1. The body is a unit; the person is a unit of body, mind, andspirit.

2. The body is capable of self-regulation, self-healing, andhealth maintenance.

3. Structure and function are reciprocally interrelated. 4. Rational treatment is based upon an understanding of the

basic principles of body unity, self-regulation, and the inter-relationship of structure and function.

The interactions between the structure and the function of thebody have encouraged the development and continued imple-mentation of treatments unique to osteopathic medicine. Osteo-pathic manipulative treatment (OMT) is 1 aspect of osteo-pathic philosophy that has been used to demonstrate howosteopathic medicine produces a distinctive physician.

A number of articles have examined the associationbetween the perceived lack of distinctiveness between osteo-

Osteopathic Medical Students’ Beliefs About Osteopathic Manipulative Treatmentat 4 Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine

Brian B. Draper, DO; Jane C. Johnson, MA; Christian Fossum, DO (Norway); and Neal R. Chamberlain, PhD

From Des Peres Hospital in St Louis, Missouri (Dr Draper); from the A.T. StillResearch Institute at A.T. Still University in Kirksville, Missouri (Ms Johnson andMr Fossum); and from the Department of Microbiology/Immunology at A.T.Still University-Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine (ATSU-KCOM), alsoin Missouri (Dr Chamberlain). Dr Draper was an osteopathic medical studentat ATSU-KCOM when this study was conducted. Mr Fossum is also affiliatedwith the Department of Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine at ATSU-KCOM.

Financial Disclosures: Funding for this study was provided in whole by amedical education mini-grant from the American Association of Colleges ofOsteopathic Medicine. The funding was used to purchase and distribute giftcards to students who were selected as winners of the prize drawing. Allauthors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Address correspondence to Brian B. Draper, DO, 735 Country Stone Ct,Manchester, MO 63021-7069.

E-mail: [email protected]

Submitted September 1, 2009; final revision received September 13, 2011;accepted September 15, 2011.

MEDICAL EDUCATION

616 • JAOA • Vol 111 • No 11 • November 2011

pathic and allopathic medicine and a decline in the belief in thetenets of osteopathic medicine.3-9 Miller7 has suggested that theosteopathic medical profession has come to resemble the pro-fession it originally revolted against. A study published in19819 reported only 48% of second-year osteopathic medicalstudents believed that the difference between an osteopathicphysician (ie, DO) and an allopathic physician (ie, MD) was suf-ficient to justify the existence of 2 separate medical profes-sions. In a survey of osteopathic interns published in 1991,Shlapentokh et al10 reported that differences in beliefs about andattitudes toward OMT were present before students appliedto medical school and persisted throughout the students’ edu-cation. In a prospective study reported in 2003, Chamberlainand Yates11 demonstrated that as students progressed throughosteopathic medical education, they became less likely to useOMT when treating their patients. In a retrospective studypublished the same year, Nichols12 indicated that osteopathicmedical students viewed themselves as becoming progres-sively “more osteopathic” as they approached graduation.However, because the students were asked to think back towhen they entered medical school rather than provide theirthoughts at the time of matriculation, recall bias may haveaffected the results of the study. Thus, these studies9-12 suggesta need to assess the attitudes and beliefs of students enteringosteopathic medical school.

However, in a study published in 2009, Bates et al13 indi-cated that teaching medical students the differences betweenosteopathic and allopathic medicine resulted in students whowere less likely to support a change in their degrees from DOto MD. Bates et al13 also encouraged osteopathic physicians tomentor students by demonstrating the osteopathic differencein their practice.

With the recent increase in the number of colleges ofosteopathic medicine (COMs)—currently, there are 26 COMsoperating in 34 locations—it is important to address howosteopathic medical students are being taught and mentoredin osteopathic principles and practice and to assess the factorsthat influence student attitudes and beliefs about OMT beforeentering medical school. Some of the factors that could beassessed include prior exposure to OMT, preference to attendan osteopathic or allopathic medical school, undergraduatemajor, and whether the student is related to a physician.

In the current study, we hypothesized that among first-and second-year osteopathic medical students, attitudes aboutosteopathic philosophy, perception of osteopathic medicaleducation, and plans for integrating OMT into future prac-tice would vary according to the COM that the studentattended, their current year of study, and the factors that drewthem to osteopathic medicine. We tested this hypothesis at 4COMs using an electronic questionnaire that was developedspecifically for the current study. After the data collection wascompleted, we conducted focus groups to refine further thequestionnaire for use in future studies.

MethodsThe institutional review board at A.T. Still University of HealthSciences-Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine (ATSU-KCOM) in Missouri reviewed and approved the current study.Four COMs were selected to participate based on the authors’associations with the schools and the schools’ geographic loca-tions: ATSU-KCOM, A.T. Still University of Health Sciences-School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona (ATSU-SOMA) inMesa, Des Moines University College of Osteopathic Medicine(DMU-COM) in Iowa, and Kansas City University of Medicineand Biosciences’ College of Osteopathic Medicine (KCUMB-COM) in Missouri. The dean of each school was contacted forapproval, and all 4 schools agreed to participate.

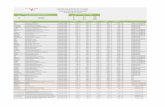

QuestionnaireA questionnaire was developed specifically for the currentstudy and was used to survey first- and second-year osteo-pathic medical students in 3 areas: attitudes about osteopathicphilosophy, perception of osteopathic predoctoral education,and plans to integrate OMT into future practice (Figure). Thequestionnaire items were on the basis of the authors’ knowl-edge of the existing literature in this area and included ques-tions similar to those in the literature that had face validity.Response options for questions in the 3 areas were based onthe Likert scale (ie, strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, orstrongly disagree). In addition, the questionnaire includedquestions concerning the student’s relationship to variousmedical professions and 1 open-ended question regardingwhat drew the student to osteopathic medicine (Appendix).The questionnaire also included questions regarding whichCOM the student attended and the student’s current year ofstudy.

An electronic version of the questionnaire was createdusing Zoomerang software (Zoomerang, San Francisco, Cal-ifornia) for online surveys.14 The questionnaire was set upthrough the Research Support office at A.T. Still University.

An e-mail explaining the study was sent in March 2009to every first- and second-year student at the 4 COMs par-ticipating in the study. The students were informed of the pur-pose of the study and the identity of the investigators, and thattheir participation in the study was optional, their responseswould be kept confidential, they could end their participationat any time, and they were not required to respond to state-ments that they did not want to answer. To encourage par-ticipation, students who completed the questionnaire weregiven the chance to enter into a raffle to win a $10 gift cardredeemable at a retail store. A link providing access to thequestionnaire on a Web site was included in the e-mail. Stu-dents were informed that by clicking on the link they weregiving their consent to participate in the study. The ques-tionnaire was open to student access for 4 weeks. A follow-up e-mail was sent 2 weeks later to encourage further par-ticipation.

Draper et al • Medical Education

MEDICAL EDUCATION

JAOA • Vol 111 • No 11 • November 2011 • 617

Significance level was set at P⩽.05. Statistical tests wereconducted using SAS software (version 9.2; SAS Institute Inc,Cary, North Carolina).

Focus GroupsAfter the data were collected, 4 focus groups were conductedat ATSU-KCOM. The purpose of the focus groups was to gaininsight into how the questionnaire was perceived and wasthe first step in validating the questionnaire for use in futurestudies. First- and second-year medical students were con-tacted by e-mail and were asked to join a focus group regard-less of whether they had completed the study questionnaire.Two of the focus groups included first-year students, and theother 2 groups included second-year students. The focusgroups discussed the questionnaire, addressing the layout,length, gift card incentive, and wording of each question. Twoof 3 of the authors (B.B.D., J.C.J., C.F.) conducted each of thefocus groups, made independent notes during the focus groupsessions, and collaborated to analyze the feedback.

ResultsOf 1478 students at the 4 COMs, 491 students completed thequestionnaire, for an overall response rate of 33% (Table 1).There were 257 first-year students (52%) and 234 second-year students (48%) who participated in the study. Thirtyrespondents did not indicate which medical school theyattended. The response rates for the individual COMs ranged

Statistical AnalysisAll questionnaire data were collected in a confidential mannerto ensure that the researchers did not have access to any iden-tifiable student information. All responses to each questionwere included in statistical analysis, even when the entirequestionnaire was not completed. Undergraduate major wascategorized as science, health, or other. Reasons for attendinga COM (in response to the question “What drew you toosteopathy?”) were qualitatively analyzed by 2 members of theresearch team (B.B.D. and N.R.C.). χ2 tests were used to deter-mine whether the reason for choosing to attend a COM wasrelated to the specific school, their current year of study, rela-tionship to a physician (a DO, an MD, neither, or both), priorexperience receiving OMT, and whether the student appliedto both osteopathic and allopathic medical schools.

The responses to individual questions were analyzed usingKruskal-Wallis tests15 to determine whether the responses wererelated to the school attended, their current year of study, rela-tionship to a physician, prior experience receiving OMT,whether the student applied to both osteopathic and allopathicmedical schools, and reasons for choosing to attend a COM.These comparisons were made to test the hypothesis that first-and second-year osteopathic medical student attitudes aboutosteopathic philosophy, perceptions of osteopathic medicaleducation, and plans for integrating OMT into future practicewould vary based on the school attended, the current year ofstudy, and the reason they were drawn to osteopathic medicine.

Draper et al • Medical Education

MEDICAL EDUCATION

Construct Description Survey Questions

Attitudes toward Osteopathic philosophy represents Labeled “Attitudes,” questions osteopathic philosophy those principles unique to osteopathic assess how strongly student

medicine. They represent the attitudes agree with osteopathic fundamentals of osteopathic medicine. principles and to what degree

osteopathic medical studentsagree or disagree with thoseprinciples unique to osteopathicmedicine.

Educational perspective Osteopathic medical education Labeled “Education,” questions on OMT keeps osteopathic medicine growing assess how osteopathic medical

and being applied in practice. students perceive their own educational experience with regard to OMT.

Plans for integrating OMT OMT is a fundamental principle of Labeled “Future Practice,” into future practice osteopathic medicine. questions assess the intentions of

students to use OMT in their future practice and whether osteopathic medical students intend to use OMTin the future or whether OMT is justa mandated part of the curriculum.

Figure. Description of constructs and survey questions used to assess osteopathic medical students’ beliefs about osteo-pathic manipulative treatment. Abbreviation: OMT, osteopathic manipulative treatment.

618 • JAOA • Vol 111 • No 11 • November 2011

Attitudes Toward Osteopathic PhilosophyStudents at ATSU-KCOM more strongly agreed that OMT isa legitimate means of treatment compared to students atKCUMB-COM (50% strongly agreed vs 29%; P=.04) (Table 4).Overall, first-year students agreed that OMT is a major dis-tinguishing factor between a DO and an MD more stronglythan second-year students (44% strongly agreed vs 38%; P=.03)(Table 5). First-year students at ATSU-KCOM, DMU-COM,and ATSU-SOMA were in more agreement with this state-ment than second-year students at DMU-COM and first-yearstudents at KCUMB-COM (P=.03) (Table 6). Students who hadreceived OMT previously more strongly agreed with state-ments regarding attitudes toward osteopathic philosophythan did students who had not (P<.04) (Table 7), as did studentswho were drawn to osteopathic medicine by osteopathic phi-

Draper et al • Medical Education

MEDICAL EDUCATION

from 15% to 49%.Table 2 summarizes demographic infor-

mation about the relationship of the studentsto various types of healthcare professionals,whether the respondents had previouslyreceived OMT or chiropractic treatment, andthe types of medical schools (ie, osteopathicor allopathic) to which the respondents applied.Regarding being related to a physician, 20%of respondents were related to an MD only,5% to a DO only, 4% to both, and 71% to nei-ther. Of 449 students who responded to thequestion “What was your undergraduatemajor?” 311 (69%) were science majors, 68(15%) were health majors, 21 (5%) were dualscience and health majors, and 49 (11%)majored in other fields.

Responses to the open-ended question“What drew you to osteopathy?” from 443 stu-dents were categorized into 6 themes, listed in order of preva-lence: osteopathic philosophy (included interest in a holisticapproach to medicine and the concept of body, mind, andspirit; 259 respondents [53%]), OMT (included interest inOMT as an additional healthcare tool; 132 [27%]), factors asso-ciated with a specific school (included location and curriculum;78 [16%]), other influences (included encouragement fromrelatives, friends, or other mentors; 52 [11%]), desire to becomea physician regardless of degree (included acceptance only ata COM; 47 [10%]), and service (included desire to help theunderserved; 14 [3%]).

The percentage of students who stated that osteopathicphilosophy was what drew them to osteopathic medicinewas significantly different based on school (P=.05), with stu-dents from KCUMB-COM (63%) and ATSU-SOMA (61%)stating this reason more frequently than students from ATSU-KCOM (51%) and DMU-COM (46%). First-year students weremore likely than second-year students to cite osteopathic phi-losophy as a reason for attending osteopathic medical school(58% vs 47%; P=.009). Students who had previously receivedOMT were less likely than those who had not received OMTto cite the desire to become a physician regardless of degreeas the reason for attending osteopathic medical school (7% vs14%; P=.01). Also, students who applied only to COMs wereless likely to cite the desire to become a physician regardlessof degree as the reason for attending osteopathic medicalschool than were students who applied to both osteopathic andallopathic medical schools (2% vs 12%; P=.0007).

Table 3 summarizes responses to statements concerningstudent attitudes toward osteopathic philosophy, beliefs aboutosteopathic predoctoral education, and intentions to use OMTin future practice.

Table 1.Study Participants Among First- and Second-Year Students at Each COM

No. of First- and No. of and Second-Year Participants Response

COM Students (n=491)* Rate, % Participant

ATSU-KCOM 340 165 49 36ATSU-SOMA 204 70 34 15DMU-COM 425 151 36 33KCUMB-COM 509 75 15 16

* Thirty respondents did not indicate which college of osteopathic medicine (COM) theyattended.

† The overall response rate was 33%.

Abbreviations: DMU-COM, Des Moines University College of Osteopathic Medicine in Iowa; ATSU-KCOM, A.T. Still University of Health Sciences-Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine inMissouri; KCUMB-COM, Kansas City University of Medicine and Biosciences College of OsteopathicMedicine in Missouri; ATSU-SOMA, A.T. Still University of Health Sciences-School of OsteopathicMedicine in Arizona in Mesa.

Table 2.Respondents’ Relationships to Various Medical Professionals, Previous Exposure to Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment,

and Application to Osteopathic and Allopathic Medical Schools (N=491)

Survey Question No. (%)

Are you related to an osteopathic physician (DO)? 42 (9)Are you related to an allopathic physician (MD)? 116 (24)Are you related to or are you a chiropractor (DC)? 22 (4)Are you related to or are you a physical therapist? 31 (6)Have you received an OMT? 327 (67)Have you received a chiropractic treatment? 189 (39)Have you applied to both osteopathic 356 (73)and allopathic medical schools?

Abbreviation: OMT, osteopathic manipulative treatment.

JAOA • Vol 111 • No 11 • November 2011 • 619

with the statement regarding the legitimacy of OMT than didstudents who were related to a DO only (P=.05) (Table 10).

Perception of Osteopathic Predoctoral EducationWith the exception of the statement “Learning OMT will pro-vide an additional tool I will use to treat patients,” there weresignificant differences (P<.03) between the schools in agree-ment with all statements assessing beliefs about osteopathicpredoctoral education (Table 4). Students at ATSU-KCOMmost strongly agreed with these statements and KCUMB-COM students agreed least. First-year students responded

losophy or OMT (P<.03 for all except 1 statement) (Table 8). Stu-dents who said that the desire to become a physician regard-less of degree is what drew them to osteopathic medicine lessstrongly agreed with statements regarding osteopathic phi-losophy (P<.02) (Table 8). Additionally, students who appliedonly to COMs were more strongly in agreement with state-ments regarding the legitimacy (59% strongly agreed vs 38%;P<.0001) and effectiveness (47% strongly agreed vs 34%;P=.002) of OMT than students who applied to both osteo-pathic and allopathic medical schools (Table 9). Students whowere related to both a DO and an MD more strongly agreed

Draper et al • Medical Education

MEDICAL EDUCATION

Table 3.Responses to Study Questionnaire (No. [%])* Assessing Attitudes, Beliefs, and Intentions

Regarding Osteopathic Medicine

Strongly StronglyArea Assessed and Statement Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Disagree

◾ Attitudes Toward Osteopathic Philosophy

◽ I believe the person is made up 390 (79) 81 (17) 11 (2) 3 (1) 6 (1)of body, mind, and spirit.

◽ I believe OMT is a legitimate means 215 (44) 199 (41) 50 (10) 17 (3) 10 (2)of treatment for patients.

◽ I believe OMT is an effective 185 (38) 212 (43) 63 (13) 20 (4) 11 (2)treatment method.

◽ OMT is a major distinguishing factor 202 (41) 170 (35) 63 (13) 37 (8) 19 (4)between a DO and an MD.

◾ Perception of Osteopathic Predoctoral Education

◽ OMT was a major factor in deciding 107 (22) 124 (25) 102 (21) 103 (21) 55 (11)to attend an osteopathic medical school.

◽ Learning OMT will provide an 203 (41) 164 (33) 69 (14) 37 (8) 18 (4)additional tool I will use to treat patients.

◽ I want to learn OMT as part of 207 (42) 156 (32) 68 (14) 38 (8) 22 (4)medical school curriculum.

◽ I will learn enough OMT in medical 104 (21) 201 (41) 95 (19) 62 (13) 29 (6)school to be proficient to begin treating patients at the start of postgraduate training.

◽ I feel that OMT will be sufficiently 119 (24) 191 (39) 107 (22) 49 (10) 24 (5)integrated throughout the medical school curriculum.†

◾ Intentions to Use OMT in Medical Practice

◽ As an osteopathic physician, I plan 67 (14) 146 (30) 128 (26) 96 (20) 53 (11)on using OMT to treat a majority of my patients when indicated.†

◽ As an osteopathic physician, I do not 46 (9) 53 (11) 84 (17) 142 (29) 165 (34)plan on using OMT.†

* Some percentages do not total 100 because of rounding.† One participant did not respond to this statement.

Abbreviations: DO, osteopathic physician; MD, allopathic physician; OMT, osteopathic manipulative treatment.

620 • JAOA • Vol 111 • No 11 • November 2011

more in agreement than second-year students that OMT wouldbe sufficiently integrated throughout the medical school cur-riculum (28% strongly agreed vs 20%; P<.0001) (Table 5). First-and second-year students at ATSU-KCOM and DMU-COMand first-year students at ATSU-SOMA had higher agreementwith the statements regarding learning enough OMT in med-ical school (P=.0004) and believing that there would be suffi-cient integration of OMT throughout the medical school cur-

riculum (P<.0001), while second-year students at ATSU-SOMA and KCUMB-COM had lower agreement with thesestatements (Table 6). Students who said they had receivedOMT previously were more strongly in agreement with state-ments regarding osteopathic predoctoral education than stu-dents who had not received OMT (P⩽.03) (Table 7).

Students who were drawn to osteopathic medicine byosteopathic philosophy or OMT more strongly agreed with the

Draper et al • Medical Education

MEDICAL EDUCATION

Table 4. Comparison of Responses of Students Who Strongly Agreed

With Questionnaire Statements (No. [%]), by College of Osteopathic Medicine

ATSU- ATSU- DMU- KCUMB- KCOM SOMA COM COM

Area Assessed and Statement (n=165) (n=70) (n=151) (n=75) P Value*

◾ Attitudes Toward Osteopathic Philosophy

◽ I believe the person is made up 139 (84) 56 (80) 111 (74) 61 (81) .10of body, mind, and spirit.

◽ I believe OMT is a legitimate means 83 (50) 26 (37) 68 (45) 22 (29) .04of treatment for patients.

◽ I believe OMT is an effective 69 (42) 25 (36) 58 (38) 18 (24) .20treatment method.

◽ OMT is a major distinguishing factor 75 (45) 29 (41) 61 (40) 22 (29) .18between a DO and an MD.

◾ Perception of Osteopathic Predoctoral Education

◽ OMT was a major factor in deciding 46 (28) 17 (24) 23 (15) 12 (16) .02to attend an osteopathic medical school.

◽ Learning OMT will provide an 76 (46) 29 (41) 50 (33) 30 (40) .08additional tool I will use to treat patients.

◽ I want to learn OMT as part of 80 (48) 31 (44) 52 (34) 27 (36) .02medical school curriculum.

◽ I will learn enough OMT in medical 43 (26) 19 (27) 27 (18) 4 (5) .0003school to be proficient to begin treating patients at the start of postgraduate training.

◽ I feel that OMT will be sufficiently 54 (33) 4 (6) 40 (27) 10 (13) <.0001integrated throughout the medical school curriculum.†

◾ Intentions to Use OMT in Medical Practice

◽ As an osteopathic physician, I plan 30 (18) 11 (16) 14 (9) 8 (11) .02on using OMT to treat a majority of my patients when indicated.†

◽ As an osteopathic physician, I do not 15 (9) 4 (6) 15 (10) 10 (13) .63plan on using OMT.†

* P value based on Kruskal-Wallis test. P⩽.05 denotes statistical significance.† One participant did not respond to this statement.

Abbreviations: ATSU-KCOM, A.T. Still University of Health Sciences-Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine in Missouri; ATSU-SOMA, A.T. Still University of Health Sciences-School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona in Mesa; DMU-COM, Des Moines University College of Osteopathic Medicine in Iowa; DO, osteopathic physician; KCUMB-COM, Kansas CityUniversity of Medicine and Biosciences’ College of Osteopathic Medicine in Missouri; MD, allopathic physician; OMT, osteopathic manipulative treatment.

JAOA • Vol 111 • No 11 • November 2011 • 621

school curriculum (59% strongly agreed vs 36%; P<.0001)(Table 9). Students who were related to both a DO and an MDmore strongly agreed that OMT will provide an additionaltreatment tool and that it will be integrated throughout themedical school curriculum than students who were relatedto a DO only, to an MD only, or to neither (P⩽.04) (Table 10).

Intentions to Use OMT in Medical PracticeCompared with students at KCUMB-COM and DMU-COM,students at ATSU-KCOM more strongly agreed that they planto use OMT to treat a majority of patients when indicated(P=.02) (Table 4), and first-year students responded more inagreement with this statement than second-year students (14%strongly agreed vs 13%; P=.04) (Table 5). First- and second-year students at ATSU-KCOM and first-year students at ATSU-SOMA most strongly agreed with the statement that they planto use OMT to treat a majority of patients (P=.01) (Table 6).Students who indicated that they had previously receivedOMT were more favorable toward using OMT to treat amajority of patients than students who had not received OMT(17% strongly agreed vs 6%; P=.01) (Table 7), as were studentswho were drawn to osteopathic medicine by osteopathic phi-losophy or OMT (P<.003 and P<.0001, respectively) (Table 8)

statements regarding OMT being a major factor in decidingwhich COM to attend, that OMT will provide an additional toolstudents will use to treat patients, and that they want to learnOMT than students who did not cite these factors (P⩽.0001)(Table 8). Students who were drawn to osteopathic medicalschool by OMT more strongly agreed that they will learnenough OMT to be proficient in treating patients at the start ofpostgraduate training compared with students not drawn toosteopathic medicine by OMT (30% strongly agreed vs 18%;P=.002) (Table 8). Students who said that the desire to becomea physician regardless of degree is what drew them to osteo-pathic medicine less strongly agreed with all the statementsregarding perceptions of osteopathic predoctoral education(P<.03) (Table 8). Students who said that they were drawn toa specific school less strongly agreed with the statement thatOMT was a major factor in deciding which COM to attend (8%strongly agreed vs 24%; P<.0001).

Students who applied only to COMs were more stronglyin agreement with statements regarding OMT being a majorfactor in deciding which COM to attend (39% strongly agreedvs 15%; P<.0001), that OMT would provide an additional toolfor treating patients (53% strongly agreed vs 37%; P=.002),and that they wanted to learn OMT as part of the medical

Draper et al • Medical Education

MEDICAL EDUCATION

Table 5.Comparison of Responses of Study Participants Who Strongly Agreed

With Questionnaire Statements (No. [%]), by Year in School

First Year Second YearArea Assessed and Statement (n=257) (n=234) P Value*

◾ Attitudes Toward OMT◽ I believe the person is made up of body, mind, and spirit. 204 (79) 186 (79) .90◽ I believe OMT is a legitimate means of treatment for patients. 107 (42) 108 (46) .91◽ I believe OMT is an effective treatment method. 90 (35) 95 (41) .96◽ OMT is a major distinguishing factor between a DO and an MD. 113 (44) 89 (38) .03◾ Perception of Osteopathic Predoctoral Education◽ OMT was a major factor in deciding to attend an osteopathic 58 (23) 49 (21) .30medical school.

◽ Learning OMT will provide an additional tool I will use to 109 (42) 94 (40) .29treat patients.

◽ I want to learn OMT as part of medical school curriculum. 115 (45) 92 (39) .23◽ I will learn enough OMT in medical school to be proficient to 52 (20) 52 (22) .61begin treating patients at the start of postgraduate training.

◽ I feel that OMT will be sufficiently integrated throughout the 72 (28) 47 (20) �.0001medical school curriculum.†

◾ Intentions to Use OMT in Medical Practice◽ As an osteopathic physician, I plan on using OMT to treat a 36 (14) 31 (13) .04majority of my patients when indicated.†

◽ As an osteopathic physician, I do not plan on using OMT.† 20 (8) 26 (11) .44

* P value based on Kruskal-Wallis test. P⩽.05 denotes statistical significance.† One participant did not respond to this statement.

Abbreviations: DO, osteopathic physician; MD, allopathic physician; OMT, osteopathic manipulative treatment.

622 • JAOA • Vol 111 • No 11 • November 2011 Draper et al • Medical Education

MEDICAL EDUCATION

Table 6.Comparison of Responses of Study Participants Who Strongly Agreed With Questionnaire Statements

(No. [%]), by Year in School and Institution

ATSU- ATSU- DMU- KCUMB-Area Assessed, Statement, KCOM SOMA COM COMand Year in School (n=165) (n=70) (n=151) (n=75) P Value*

◾ Attitudes Toward Osteopathic Philosophy

◽ I believe the person is made up of .39body, mind, and spirit.– First year 58 (87) 28 (82) 59 (71) 47 (81)– Second year 81 (83) 28 (78) 52 (76) 14 (82)

◽ I believe OMT is a legitimate means .08of treatment for patients.– First year 37 (55) 12 (35) 35 (42) 15 (26)– Second year 46 (47) 14 (39) 33 (49) 7 (41)

◽ I believe OMT is an effective treatment .46method.– First year 29 (43) 13 (38) 30 (36) 11 (19)– Second year 40 (41) 12 (33) 28 (41) 7 (41)

◽ OMT is a major distinguishing factor .03between a DO and an MD.– First year 35 (52) 15 (44) 39 (47) 15 (26)– Second year 40 (41) 14 (39) 22 (32) 7 (41)

◾ Perception of Osteopathic PredoctoralEducation

◽ OMT was a major factor in deciding to .05attend an osteopathic medical school.– First year 18 (27) 8 (24) 14 (17) 12 (21)– Second year 28 (29) 9 (25) 9 (13) 0

◽ Learning OMT will provide an additional .15tool I will use to treat patients.– First year 35 (52) 15 (44) 26 (31) 23 (40)– Second year 41 (42) 14 (39) 24 (35) 7 (41)

◽ I want to learn OMT as part of medical .04school curriculum.– First year 37 (55) 15 (44) 32 (39) 21 (36)– Second year 43 (44) 16 (44) 20 (29) 6 (35)

◽ I will learn enough OMT in medical .0004school to be proficient to begin treatingpatients at the start of postgraduatetraining.– First year 21 (31) 12 (35) 12 (14) 3 (5)– Second year 22 (22) 7 (19) 15 (22) 1 (6)

◽ I feel that OMT will be sufficiently <.0001integrated throughout the medical school curriculum.†

– First year 32 (48) 3 (9) 22 (27) 9 (16)– Second year 22 (22) 1 (3) 18 (26) 1 (6)

(continued)* P value based on Kruskal-Wallis test. P⩽.05 denotes statistical significance.† One participant did not respond to this statement.

Abbreviations: ATSU-KCOM, A.T. Still University of Health Sciences-Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine in Missouri;ATSU-SOMA, A.T. Still University of Health Sciences-School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona in Mesa; DMU-COM, DesMoines University College of Osteopathic Medicine in Iowa; DO, osteopathic physician; KCUMB-COM, Kansas City Universityof Medicine and Biosciences’ College of Osteopathic Medicine in Missouri; MD, allopathic physician; OMT, osteopathicmanipulative treatment.

JAOA • Vol 111 • No 11 • November 2011 • 623

osteopathic medicine. The statement “I will learn enoughOMT in medical school to be proficient to begin treatingpatients at the start of post-graduate training” was reported tobe confusing and too long. On the basis of feedback from thestudents, 5 questions were added to the questionnaire, andother questions were modified for clarity. These changes willbe included in future studies.

CommentThe main objective of the current study was to assess thebeliefs and attitudes of first- and second-year osteopathic med-ical students regarding osteopathic philosophy in order todetermine whether there were any differences in their atti-tudes based on various factors (eg, the COM they attended andtheir current year of study). The analysis of responses by cer-tain subgroups of students revealed a number of statisticallysignificant differences in agreement with osteopathic philos-ophy and intention to use OMT in future practice. Specifi-cally, prior experience receiving OMT, reasons for attendingosteopathic medical school, the medical school that a studentchose to attend, and the student’s current year of study wererelated to student attitudes about osteopathic philosophy. Stu-dents who had previously received OMT, students whoapplied only to COMs, and first-year students overall morestrongly agreed with the questionnaire’s statements aboutosteopathic philosophy and intention to use OMT than didthose students’ counterparts.

Using a similar study design, Miller16 surveyed osteo-

and students who applied only to osteopathic schools (25%strongly agreed vs 10%; P=.0002) (Table 9). Students who weredrawn to osteopathic medicine by the desire to become aphysician regardless of degree were less favorable about usingOMT for a majority of patients in future practice compared withstudents who were not drawn to osteopathic medicine by thedesire to become a physician regardless of degree (0% stronglyagreed vs 15%; P<.0001) (Table 8).

Focus GroupsFourteen first-year students and 14 second-year students par-ticipated in the 4 focus groups at ATSU-KCOM. In general,their comments were positive regarding the clarity of the ques-tions and the time needed to complete the questionnaire. Thestudents thought the length of the questionnaire was man-ageable, and that they needed, on average, less than 5 minutesto complete the questionnaire. The majority of the studentsthought that the opportunity to win a gift card was adequateincentive to increase their likelihood of completing the ques-tionnaire. Many students stated that knowing the researcherswas a reason for participating. On the basis of these results, theauthors concluded that the best way to distribute the ques-tionnaire would be to have a contact person from each schooldistribute the e-mail to the students.

The statement “OMT is a major distinguishing factorbetween a DO and an MD” evoked a large amount of discus-sion and resulted in the addition of 2 statements to include infuture questionnaires regarding other distinguishing factors of

Draper et al • Medical Education

MEDICAL EDUCATION

Table 6 (continued).Comparison of Responses of Study Participants Who Strongly Agreed With Questionnaire Statements

(No. [%]), by Year in School and Institution

ATSU- ATSU- DMU- KCUMB-Area Assessed, Statement, KCOM SOMA COM COMand Year in School (n=165) (n=70) (n=151) (n=75) P Value*

◾ Intentions to Use OMT in Medical Practice◽ As an osteopathic physician, I plan .01on using OMT to treat a majority of my patients when indicated.†

– First year 13 (19) 6 (18) 8 (10) 7 (12)– Second year 17 (17) 5 (14) 6 (9) 1 (6)

◽ As an osteopathic physician, I do not .58plan on using OMT.†

– First year 2 (3) 2 (6) 8 (10) 7 (12)– Second year 13 (13) 2 (6) 7 (10) 3 (18)

* P value based on Kruskal-Wallis test. P⩽.05 denotes statistical significance.† One participant did not respond to this statement.

Abbreviations: ATSU-KCOM, A.T. Still University of Health Sciences-Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine in Missouri;ATSU-SOMA, A.T. Still University of Health Sciences-School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona in Mesa; DMU-COM, DesMoines University College of Osteopathic Medicine in Iowa; DO, osteopathic physician; KCUMB-COM, Kansas City Universityof Medicine and Biosciences’ College of Osteopathic Medicine in Missouri; MD, allopathic physician; OMT, osteopathicmanipulative treatment.

624 • JAOA • Vol 111 • No 11 • November 2011

pathic medical students and found that undergraduate major,preference to attend an osteopathic or allopathic medicalschool, and level of previous osteopathic knowledge predicteda student’s level of commitment to OMT. The current study didnot show any differences among students in their agreementwith the use of OMT based on their undergraduate major.However, students who stated they were drawn to osteo-pathic medicine by the desire to become a physician regard-less of degree and students who applied to both osteopathicand allopathic medical schools were in less agreement withstatements about osteopathic beliefs, OMT, and predictedOMT use in future practice. Multiple other studies3,5,8,9,17,18

have identified students whose main desire is to become aphysician regardless of degree. In the current study, studentswho stated that osteopathic philosophy or OMT drew them toosteopathic medicine expressed more agreement with osteo-pathic beliefs, OMT, and predicted OMT use in future practicethan did those who did not indicate that osteopathic philos-ophy or OMT drew them to osteopathic medicine.

Also in the current study, students with prior exposure toOMT showed more agreement with osteopathic beliefs, OMT,and predicted OMT use in future practice than students

without prior exposure, showing statistically significant dif-ferences in responses to every statement in the first 3 sections(Attitudes, Education, and Future Practice) of the question-naire. Teitelbaum et al19 found that a higher percentage ofosteopathic medical students were convinced to follow theosteopathic approach after the first year of medical schoolcompared to the percentage of students who were convincedbefore matriculation. This finding may explain why studentsin the current study who were related to both a DO and an MDwere more in agreement with the statements that OMT pro-vides an additional treatment tool and OMT would be suffi-ciently integrated throughout their medical education. Per-haps these students are better able to compare the differencesbetween osteopathic and allopathic medicine while also beingmore in agreement with osteopathic philosophy and the uti-lization of OMT. However, students in the current study whowere related to physicians from both professions may have self-selected before attending medical school, based on the phi-losophy of medicine with which they most agreed. Furtherresearch is needed to assess this association before any definitecausal relationship can be declared.

According to the findings of the current study, beliefs

Draper et al • Medical Education

MEDICAL EDUCATION

Table 7.Comparison of Responses of Study Participants Who Strongly Agreed

With Questionnaire Statements (No. [%]), by Prior Experience With OMT

No PriorPrior OMT OMT

Area Assessed and Statement (n=327) (n=161) P Value*

◾ Attitudes Toward Osteopathic Philosophy◽ I believe the person is made up of body, mind, and spirit. 269 (82) 119 (74) .03◽ I believe OMT is a legitimate means of treatment for patients. 160 (49) 55 (34) .003◽ I believe OMT is an effective treatment method. 140 (43) 45 (28) .0006◽ OMT is a major distinguishing factor between a DO and an MD. 148 (45) 53 (33) .03◾ Perception of Osteopathic Predoctoral Education◽ OMT was a major factor in deciding to attend an osteopathic 90 (28) 16 (10) <.0001medical school.

◽ Learning OMT will provide an additional tool I will use to treat 146 (45) 57 (35) .01patients.

◽ I want to learn OMT as part of medical school curriculum. 148 (45) 58 (36) .005◽ I will learn enough OMT in medical school to be proficient to 79 (24) 24 (15) .003begin treating patients at the start of postgraduate training.

◽ I feel that OMT will be sufficiently integrated throughout the 91 (28) 28 (17) .03medical school curriculum.†

◾ Intentions to Use OMT in Medical Practice◽ As an osteopathic physician, I plan on using OMT to treat a 57 (17) 10 (6) .01majority of my patients when indicated.†

◽ As an osteopathic physician, I do not plan on using OMT.† 32 (10) 14 (9) .0006

* P value based on Kruskal-Wallis test. P⩽.05 denotes statistical significance.† One participant did not respond to this statement.

Abbreviations: DO, osteopathic physician; MD, allopathic physician; OMT, osteopathic manipulative treatment.

JAOA • Vol 111 • No 11 • November 2011 • 625

of students who stated that osteopathic philosophy was thereason they were drawn to osteopathic medical school. Theseresults suggest that students agree with osteopathic philos-ophy but are not planning to use OMT in their medical prac-tice. Possible reasons for these results may be that the schoolshave different styles of teaching OMT and place a different

about OMT being a major distinguishing factor between aDO and an MD, wanting to learn OMT, and planning to useOMT in future practice differed among students attendingthe 4 COMS. In general, students at ATSU-KCOM were morein agreement with the utilization of OMT than students fromthe other schools. KCUMB-COM had the highest percentage

Draper et al • Medical Education

MEDICAL EDUCATION

Table 8.Comparison of Responses of Study Participants (%) Who Strongly Agreed With Questionnaire Statements,

by Reason for Attending a College of Osteopathic Medicine*

Desire to BecomeOsteopathic Philosophy OMT a Physican

Study Study StudyParticipants, % P Value‡ Participants, % P Value‡ Participants, % P Value‡

◾ Attitudes Toward Osteopathic Philosophy

◽ I believe the person is made 87 vs 71 <.0001 87 vs 77 .02 66 vs 81 .01up of body, mind, and spirit.

◽ I believe OMT is a legitimate 50 vs 37 .0001 58 vs 39 <.0001 26 vs 46 <.0001means of treatment for patients.

◽ I believe OMT is an effective 43 vs 31 .0007 52 vs 33 <.0001 11 vs 41 <.0001 treatment method.

◽ OMT is a major distinguishing 43 vs 39 .09 60 vs 34 <.0001 17 vs 44 <.0001factor between a DO and an MD.

◾ Perception of Osteopathic Predoctoral Education

◽ OMT was a major factor in 25 vs 19 <.0001 45 vs 13 <.0001 2 vs 24 <.0001deciding to attend an osteopathic medical school.

◽ Learning OMT will provide an 47 vs 35 .0001 59 vs 35 <.0001 17 vs 44 <.0001additional tool I will use to treat patients.

◽ I want to learn OMT as part 51 vs 32 <.0001 59 vs 36 <.0001 13 vs 45 <.0001of medical school curriculum.

◽ I will learn enough OMT in 20 vs 22 .44 30 vs 18 .002 17 vs 22 .02medical school to be proficient to begin treating patients at thestart of postgraduate training.

◽ I feel that OMT will be sufficiently 25 vs 24 .09 30 vs 22 .36 15 vs 25 .003integrated throughout the medical school curriculum.‡

◾ Intentions to Use OMT in Medical Practice◽ As an osteopathic physician, 15 vs 13 .002 23 vs 10 <.0001 0 vs 15 <.0001I plan on using OMT to treat a majority of my patients whenindicated.‡

◽ As an osteopathic physician, 4 vs 15 .002 2 vs 12 <.0001 30 vs 7 <.0001I do not plan on using OMT.‡

* Data are presented as the percentage of study participants who were influenced by the reason for attending a college of osteopathic medicine vs the percentage of study participants who were not influenced by the reason, except where otherwise specified.

† P value based on Kruskal-Wallis test. P⩽.05 denotes statistical significance.‡ One participant did not respond to this statement.

Abbreviations: DO, osteopathic physician; MD, allopathic physician; OMT, osteopathic manipulative treatment.

626 • JAOA • Vol 111 • No 11 • November 2011

emphasis on osteopathic philosophy, and that students whoare more favorable toward OMT choose to attend certainschools. Further research is needed to assess how OMT andosteopathic philosophy are taught at each school before anydefinite conclusions can be drawn about these differences.

The current study did show differences among the COMs,with students at certain COMs agreeing more strongly withosteopathic philosophy and intended use of OMT. This infor-mation may be an important tool in the assessment of osteo-pathic medical education regarding osteopathic philosophy andOMT. It may also help undergraduate students who areapplying to COMs decide which schools are more appropriateto help them achieve their goals. For example, students whoare more interested in learning and using OMT may want toapply to a school that emphasizes and teaches more OMT.

In a study by Miller,16 no differences among schools werefound regarding commitment to OMT. However, there were

differences among the schools regarding behavioral inten-tions. Chamberlain and Yates20 also demonstrated that stu-dents with adequate osteopathic knowledge and skills do notalways use OMT when they are placed in a standardizedpatient encounter. Bates et al14 suggested that although teachingosteopathic philosophy is helpful in showing medical stu-dents the osteopathic difference, mentoring students in a clin-ical situation may better demonstrate the use of OMT in clin-ical practice.

Studies21-23 have shown that student attitudes towardOMT decline during clinical rotations and that students havemore favorable attitudes toward OMT if they complete anOMT rotation. One study showed that standardized OMTinstruction during the clinical years increased OMT use inhospitalized patients.24 However, further research is needed toassess student attitudes during clinical training and to deter-mine what instruction is provided to those students during

Draper et al • Medical Education

MEDICAL EDUCATION

Table 9.Comparison of Responses of Study Participants Who Strongly Agreed

With Questionnaire Statements (No. [%]), by Application to Medical Schools

Osteopathic Osteopathicand Allopathic Only

Area Assessed and Statement (n=356) (n=133) P Value*

◾ Attitudes Toward Osteopathic Philosophy◽ I believe the person is made up of body, mind, 278 (78) 111 (83) .21and spirit.

◽ I believe OMT is a legitimate means of treatment 136 (38) 79 (59) <.0001for patients.

◽ I believe OMT is an effective treatment method. 122 (34) 63 (47) .002◽ OMT is a major distinguishing factor between 139 (39) 63 (47) .09a DO and an MD.

◾ Perception of Osteopathic Predoctoral Education◽ OMT was a major factor in deciding to attend an 55 (15) 52 (39) <.0001osteopathic medical school.

◽ Learning OMT will provide an additional tool I will 133 (37) 70 (53) .002use to treat patients.

◽ I want to learn OMT as part of medical school 128 (36) 79 (59) <.0001curriculum.

◽ I will learn enough OMT in medical school to be 73 (21) 31 (23) .40proficient to begin treating patients at the start of postgraduate training.

◽ I feel that OMT will be sufficiently integrated 82 (23) 37 (28) .37throughout the medical school curriculum.†

◾ Intentions to Use OMT in Medical Practice◽ As an osteopathic physician, I plan on using OMT 34 (10) 33 (25) .0002to treat a majority of my patients when indicated.†

◽ As an osteopathic physician, I do not plan on 38 (11) 8 (6) .0001using OMT.†

* P value based on Kruskal-Wallis test. P⩽.05 denotes statistical significance.† One participant did not respond to this statement.

Abbreviations: DO, osteopathic physician; MD, allopathic physician; OMT, osteopathic manipulative treatment.

JAOA • Vol 111 • No 11 • November 2011 • 627

dinal study to assess student attitudes from matriculation tograduation. The study is designed to determine how studentattitudes change during each year of osteopathic predoctoraleducation and to further establish the differences betweenCOMs seen in the current study.

Many studies8,9,11,16,17,18-23 have been conducted assessingvarious beliefs and attitudes held by students at various timesduring their education. However, we found no studies that sur-veyed students at matriculation. Miller16 conducted a surveyof osteopathic medical students and suggested that resultscould be explained by the predispositions and attitudes ofstudents before entering osteopathic medical school. How-ever, students in Miller’s study were evaluated after they hadattended a COM for at least 6 months, so further examina-tion is required to determine the validity of this finding. Stu-dents should be evaluated before they begin their osteopathicmedical education to establish a baseline of attitudes and

their 4 years of medical education.In the current study, first-year students agreed more

strongly with the use of OMT than did second-year students.First-year students at ATSU-KCOM expressed the strongestdesire to learn OMT and believed that OMT would be inte-grated throughout their medical education curriculum. Second-year students at ATSU-SOMA reported less agreement withlearning OMT and with using it in future practice; however,these students were the only ones who had begun clinicalrotations. These results may be due to first-year studentshaving little information on subsequent years of medical schooland second-year students learning more about those subse-quent years through discussions with third- and fourth-yearstudents, on- and off-campus faculty, and administrators. Per-haps future studies could address this issue by integratingOMT into clinical rotations and demonstrating the use of OMTin clinical practice. We are currently conducting a longitu-

Draper et al • Medical Education

MEDICAL EDUCATION

Table 10.Comparison of Responses of Study Participants Who Strongly Agreed With Questionnaire Statements (No. [%]), by Relationship to Physicians

Related to…DO Only MD Only Both Neither

Area Assessed and Statement (n=25) (n=99) (n=17) (n=350) P Value*

◾ Attitudes Toward Osteopathic Philosophy◽ I believe the person is made up of body, mind, 16 (64) 76 (77) 12 (71) 282 (82) .15and spirit.

◽ I believe OMT is a legitimate means of treatment 7 (28) 38 (38) 10 (59) 160 (46) .05for patients.

◽ I believe OMT is an effective treatment method. 7 (28) 34 (34) 8 (47) 136 (39) .13◽ OMT is a major distinguishing factor between 9 (36) 41 (41) 9 (53) 143 (41) .60a DO and an MD.

◾ Perception of Osteopathic Predoctoral Education◽ OMT was a major factor in deciding to attend 5 (20) 14 (14) 4 (24) 84 (24) .18an osteopathic medical school.

◽ Learning OMT will provide an additional tool 9 (36) 32 (32) 11 (65) 151 (43) .04I will use to treat patients.

◽ I want to learn OMT as part of medical school 10 (40) 36 (36) 10 (59) 151 (43) .21curriculum.

◽ I will learn enough OMT in medical school 6 (24) 17 (17) 7 (41) 74 (21) .23to be proficient to begin treating patients at the start of postgraduate training.

◽ I feel that OMT will be sufficiently integrated 6 (25) 21 (21) 10 (59) 82 (23) .02throughout the medical school curriculum.†

◾ Intentions to Use OMT in Medical Practice◽ As an osteopathic physician, I plan on using OMT 1 (4) 12 (12) 12 (18) 51 (15) .39to treat a majority of my patients when indicated.†

◽ As an osteopathic physician, I do not plan on 2 (8) 10 (10) 1 (6) 33 (9) .61using OMT.†

* P value based on Kruskal-Wallis test. P⩽.05 denotes statistical significance.† One participant did not respond to this statement.

Abbreviations: DO, osteopathic physician; MD, allopathic physician; OMT, osteopathic manipulative treatment.

628 • JAOA • Vol 111 • No 11 • November 2011

beliefs. After establishing that baseline, students can bereassessed throughout their medical education to determinehow their attitudes and beliefs progress.

As an osteopathic medical student, Nemon8 surveyedsecond-, third-, and fourth-year medical students at the NewYork College of Osteopathic Medicine of the New York Insti-tute of Technology regarding their beliefs about and percep-tions of osteopathic medicine, their osteopathic predoctoraleducation, and their future graduate medical education. Asurprising number of students indicated that they felt disso-ciated from A.T. Still and 49% indicated they did not wantosteopathic medicine to be more distinctive from allopathicmedicine. Yet in Nemon’s study, published in 1998, 54% of stu-dents believed that OMT and osteopathic principles should bemore positively reinforced, and 79% of students said theywould like to be more competent in using OMT.8 These resultssuggest a strong belief in OMT, but there seems to be a dis-connection with some aspect of osteopathic medical education.However, more evaluation is necessary. Our ongoing longi-tudinal study follows students throughout their osteopathicmedical training to assess how their attitudes are changedand influenced during training.

In a study of second-year osteopathic medical students,Teitelbaum et al19 found that after the first year of osteopathicmedical school, 43% more of the students were convinced ofthe validity of osteopathic medicine compared to their beliefsabout its validity before they began school. The study by Teit-elbaum et al19 also stressed the need for both a longitudinalstudy and a concurrent study of all COMs.

A prospective investigation of all COMs may be instruc-tive in determining if trends are consistent among all osteo-pathic medical students from matriculation to graduation. Abaseline evaluation of the attitudes and beliefs of osteopathicmedical students toward osteopathic philosophy and OMTwould be instructive. Further, a longitudinal prospective studycould provide valuable insight into when and how the attitudesof medical students change as they progress through theireducation. Such a study would also help to identify specific fac-tors that either promote or discourage learning and the even-tual use of OMT. An assessment of the current state of osteo-pathic predoctoral education regarding osteopathic philosophyand OMT could be used by COMs to change the curriculumand learning environment and to enhance the willingness ofstudents to maintain the distinctiveness of the osteopathicmedical profession.

LimitationsThe current study has several limitations. One limitation is aself-selection bias. Data on demographic information for pop-ulation comparison were not collected. Thus, a comparisonbetween students who participated in the study and thosewho did not could not be made. At 3 of the COMs, however,a relatively large percentage of the student body responded,

making self-selection bias less likely. Questions about demo-graphic characteristics should be included in future studiesto control for the effects of self-selection.

Another limitation of the current study is general bias. Stu-dent responses may have been influenced by the language ofthe questionnaire, which specifically addressed osteopathicphilosophy and OMT. This bias may not hold for all studentswho responded, though, because for most of the statements,very few students responded that they strongly disagreed,and when asked what drew them to osteopathic medicine,this minority stated that their desire was to become a physicianregardless of the degree. The data used to compare schoolswere limited by the small response rate at KCUMB-COM.The 3 other schools (ATSU-KCOM, ATSU-SOMA, and DMU-COM) had a response rate greater of 34% or greater, whileKCUMB-COM had a response rate of 15%. Therefore, studyresults should be interpreted with caution because of theincreased uncertainty arising from the limited responses fromstudents at KCUMB-COM.

Finally, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the use ofOMT in practice on the basis of student projections of futureOMT use. At this point in their medical training, studentshave not been sufficiently exposed to actual patient care. There-fore, the conclusions of the current study are limited to the pro-jected future use of OMT and not the actual use of OMT inpractice.

ConclusionOsteopathic medical students who stated that osteopathic phi-losophy or OMT drew them to attend osteopathic medicalschool and osteopathic medical students who had previouslyreceived OMT had higher levels of agreement with osteo-pathic philosophy and reflected a greater intention to useOMT in future practice than did students who applied to bothosteopathic and allopathic medical schools or students whochose osteopathic medical school only as a means to becomea physician regardless of the degree. The attitudes of the stu-dents varied based on the COM that they attended and theiryear of study. Specifically, students at ATSU-KCOM morestrongly agreed with the legitimacy of OMT and positive state-ments regarding OMT as part of their osteopathic predoctoraleducation than did students from KCUMB-COM. Studentsat ATSU-KCOM and DMU-COM had stronger agreementwith statements about OMT being integrated throughout themedical school curriculum than did students at KCUMB-COM and ATSU-SOMA.

Student agreement with osteopathic philosophy and theuse of OMT appeared to be higher in first-year medical stu-dents. The level of agreement with statements regarding thesufficient integration of OMT throughout the curriculum andthe intention to use OMT in clinical practice decreased after stu-dents started their clinical rotations. Because the osteopathicmedical students of today will define and shape the osteo-

Draper et al • Medical Education

MEDICAL EDUCATION

JAOA • Vol 111 • No 11 • November 2011 • 629

11. Chamberlain NR, Yates HA. A prospective study of osteopathic medical stu-dents’ attitudes toward use of osteopathic manipulative treatment in caringfor patients. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2003;103(10):470-478.

12.Nichols KJ. Results of a survey of inaugural class graduates of a college ofosteopathic medicine. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2003;103(1):9-15.

13. Bates BR, Mazer JP, Ledbetter AM, Norander S. The DO difference: an anal-ysis of causal relationships affecting the degree-change debate. J AmOsteopath Assoc. 2009;109(7):359-369.

14. Zoomerang Online Surveys & Polls. Available at http://www.zoomerang.com. Accessed October 12, 2011.

15. Daniel WW. Applied Nonparametric Statistics. 2nd ed. Boston, MA:Duxbury Press; 2000.

16.Miller K. The Use of Osteopathic Principles and Practice: A Study of Osteo-pathic Medical Students. Final Report. Grant S90-03, September 1992; ArizonaState University.

17.McNamee KP, Magarian K, Phillips RB, Greenman PE. Osteopathic vs. chi-ropractic education: a student perspective. J Manipulative Physiol Ther.1991;14(7):422-427.

18. New PK. The osteopathic students: a study in dilemma. In: Jaco EG, ed.Patients, Physicians, and Illness. Glencoe, IL: Free Press; 1958:413-421.

19. Teitelbaum HS, Bunn WE II, Brown SA, Burchett AW. Osteopathic medicaleducation: renaissance or rhetoric? J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2003;103(10):489-490.

20. Chamberlain NR, Yates HA. Use of a computer-assisted clinical case (CACC)SOAP note exercise to assess students’ application of osteopathic principlesand practice. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2000;100(7):437-440.

21.Aguwa MI, Liechty DK. Professional identification and affiliation of the 1992graduate class of the colleges of osteopathic medicine. J Am OsteopathAssoc. 1999;99(8):408-420.

22. Gamber RG, Gish EE, Herron KM. Student perceptions of osteopathicmanipulative treatment after completing a manipulative medicine rotation.J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2001;101(7):395-400.

23.Magnus WW, Gamber RG. Osteopathic manipulative treatment: studentattitudes before and after intensive clinical exposure. J Am Osteopath Assoc.1997;97(2):109-113.

24. Shubrook JH, Jr, Dooley J. Effects of a structured curriculum in osteo-pathic manipulative treatment (OMT) on osteopathic structural examina-tions and use of OMT for hospitalized patients. J Am Osteopath Assoc.2000;100(9):554-558.

Appendix follows on the next page.

pathic medical profession of tomorrow, administration of arefined questionnaire to students from a variety of COMs asthey progress through their education should provide insightinto how COMs can help the profession maintain its distinc-tiveness.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank the deans of the 4 COMs at the time of this study for theirsupport: Philip C. Slocum, DO, at ATSU-KCOM; Douglas L. Wood,DO, PhD, at ATSU-SOMA; Kendall Reed, DO, at DMU-COM;and Darin L. Haug, DO, at KCUMB-COM. We also thank LisaSmall, research assistant at ATSU, for administering the question-naire, and Deborah Goggin, MA, scientific writer at ATSU, for edi-torial assistance.

References 1. Tenets of osteopathic medicine. American Osteopathic Association Web site.http://www.osteopathic.org/inside-aoa/about/leadership/Pages/tenets-of-osteopathic-medicine.aspx. Accessed October 17, 2011.

2. Stark J. Basic principles of osteopathy. Osteopath Today. 2006;13:14-15.

3. Eckberg DL. The dilemma of osteopathic physicians and the rationalizationof medical practice. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25(10):1111-1120.

4. Johnson SM, Bordinat D. Professional identity: key to the future of the osteo-pathic medical profession in the United States. J Am Osteopath Assoc.1998;98(6):325-331.

5. Johnson SM, Kurtz ME. Diminished use of osteopathic manipulative treat-ment and its impact on the uniqueness of the osteopathic profession. AcadMed. 2001;76(8):821-828.

6. Leahy J. Manipulation: a survey of how DOs feel about it. Osteopath Physi-cian. 1972;38:31-38.

7. Miller K. The evolution of professional identity: the case of osteopathicmedicine. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(11):1739-1748.

8.Nemon BM. Osteopathic medical profession: who are we & where are wegoing? a student’s perspective. Am Acad Osteopath J. 1997;7(1):10-15,30-34.

9. Radis C. Osteopathic education: a student perspective. Osteopath Ann.1981;9:32-37.

10. Shlapentokh V, O’Donnell N, Grey MB. Osteopathic interns’ attitudestoward their education and training. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1991;91(8):786-796,801-782.

Draper et al • Medical Education

MEDICAL EDUCATION

630 • JAOA • Vol 111 • No 11 • November 2011 Draper et al • Medical Education

MEDICAL EDUCATION

Strongly StronglyAgree Agree Neutral Disagree Disagree

◾ Attitudes◽ I believe the person is made up of body, mind, and spirit.

◽ I believe OMT is a legitimate means of treatment for patients.

◽ I believe OMT is an effective treatment method.◽ OMT is a major distinguishing factor between an osteopathic physician (DO) and an allopathic physician (MD).

◾ Education◽ OMT was a major factor in deciding which osteopathic medical school to attend.

◽ Learning OMT will provide an additional tool I will use to treat patients.

◽ I want to learn OMT as part of medical school curriculum.

◽ I will learn enough OMT in medical school to be proficient to begin treating patients at the start of post-graduate training.

◽ I feel that OMT will be sufficiently integrated throughout the medical school curriculum.

◾ Future Practice◽ As an osteopathic physician I plan on using OMT to treat a majority of my patients when indicated.

◽ As an osteopathic physician I do not plan on using OMT.

Yes No◾ Demographics◽ Are you related to an osteopathic physician (DO)?◽ Are you related to an allopathic physician (MD)?◽ Are you related to or are you a chiropractor (DC)?◽ Are you related to or are you a physical therapist?◽ Have you ever received an osteopathic medical treatment?◽ Have you ever received a chiropractic treatment?◽ Did you apply to both osteopathic and allopathic medical schools?

◽ Where are you from (City, State)?

◽ What was your undergraduate college major?

◽ What drew you to osteopathic medicine?

AppendixQuestionnaire distributed to students at 4 colleges of osteopathic medicine to assess osteopathic medical students beliefs aboutosteopathic manipulative treatment.