Ōkyo's Skeleton not performing zazen, reflections of the iconography of the Daijōji's kyakuden

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Ōkyo's Skeleton not performing zazen, reflections of the iconography of the Daijōji's kyakuden

Background

Commissioned in 1787 for Kameisan Daijôji, a

Shingon temple close to the Sea of Japan in

Kasumi, Hyôgo Prefecture, Maruyama Ôkyo’s

kakejiku (hanging scroll) known as Hajô hakkotsu

zazen zu (Skeleton performing zazen above the waves),

is a misnomer (fig. 1). Notwithstanding its remote

location, its early fame rested as much on studio

copies1 as on the later, 19th-century appropriation

of the image as a tool for the Zen practice of

hakkotsu kan 白骨観, or contemplation of white

bones.2 This article attempts to examine Ôkyo’s

imagery, its visual and iconographical sources,

repositioning the ‘icon’ within its original Shingon

ritual context, to elucidate its layers of meaning.

The Daijôji’s kyakuden or Guest Hall, decorated by

Ôkyo (1733–1795) and his pupils in 1787 and 1795,

served as both a guest hall and as a ritual dôjô or

Buddhist training and practice hall in a shrine-

temple complex (miyadera) dedicated to Yakushi

Nyorai, Jûichimen Kannon and the local Mikawa

daigongen. The thirteen rooms of the building are

adorned with fusuma (sliding partitions) depicting

landscapes, Chinese literati themes and auspicious

animals, and with portable screens and kakejiku

designed for ritual use, some of which reproduce

famous Buddhist icons from the capital Kyoto.

Daijôji was allegedly founded by Gyoki, a

priest of the Hossô sect, in March 745, and was

under the control of the Tendai monk Ennin

(794–864), becoming Shingon at an unknown date.

By the 18th century, it was affiliated with the Ono

Shingon Zuishin-in in Kyoto, which appointed its

abbots. The commissioning abbot, Mitsuzô, a

wealthy native of Kasumi, had been an early

patron of Ôkyo in Kyoto; the building and its

paintings were financed by Mitsuzô, and by the

Andon 99 64

Ökyo’s Skeleton

not performing zazen

Reflect ions on the iconography of the Dai jöj i ’ s kyakuden

Beatrice B. Shoemaker

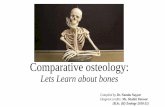

Fig. 1. Maruyama Ökyo, Hajö hakkotsu zazen zu

(Skeleton performing zazen above the waves), 1787.

Kakejiku. Ink and light colours on paper.

© Kameisan Daijö-ji, Kasumi-cho, Hyögo

faithful of seven neighbouring villages, without

assistance from the local Izushi daimyô. They were

completed under Mitsuzô’s successor, Mitsuei.3

Ôkyo’s Skeleton of 1787, painted in sumi and light

colours on paper, appears from its fold creases not

to have been originally designed as a kakejiku, and

would therefore have been only opened out on

special occasions for private contemplation and

meditation.4 The skeleton clearly floats above a

white-capped sea, its westernised frontal

perspective contrasting with a conventional high-

viewpoint over the waves. The painting’s style

combines the running-water line and wash Yuan

modes of Li Gonglin and Ren Renfa with Western

shading, generating a dislocated dual perspective.

The skeleton itself is seated in the lotus posture, its

hands united in the meditation mudra of Dainichi

Nyorai, leading to the misleading description of

“performing zazen”.5 According to the present

Head Priest, Shinnô Yamasoba, the skeleton

embodies the essence of the enlightened being

who has literally shed all fleshly desires through

long meditative practices, rising above a

fathomless sea, whose turbulent surface belies the

eternal calmness beneath.6 Visually, the image

opposes, and unites by that contrast, the

changeable skein of the water’s surface with the

purified armature of what was once perishable

flesh. In essence, the skeleton illustrates the

Shingon principle of becoming a Buddha in this

body, and this life, borne aloft by the ‘ocean

assembly’ of Buddhas, Boddhisattvas and superior

beings contained in the mandala world.7

Origin of the image

Why a skeleton? This choice, made by Ôkyo in

concert with Mitsuzô, can only be understood in

reference to what this image is not as well as to

what it is.8

Ôkyo’s Skeleton may have been the first

anatomically accurate skeleton depicted in a lotus

position, but skeletons had a long and bifurcated

history in Japanese iconology.

Ôkyo’s innovative depiction rested on shasei

(写生, drawing from nature), the realism he

adopted from rangaku, Western studies, an interest

which he shared with both his early mentor Abbot

Yûjô of Enman-in and his imperial pupil and

patron Shinnô Shinnin of the Myôhô-in.9 The first

officially authorised dissection of a human body in

Japan was performed in Kyoto in 1754 by the

physician Yamawaki Tôyô, and published as the

Zôshi (Anatomical record) in 1759. Until then,

knowledge of human anatomy had rested

exclusively on Chinese medical treatises. Another

autopsy was witnessed by the physician Sugita

Genpaku in Edo in 1771.10 Ôkyo certainly had

access to the anatomical treatises of Vesalius and

Johannes Kulm, and to Sugita Genpaku’s 1774

translation of the latter’s Tafel Anatomica, known as

the Kaitai shinsho (New writings on dissection).11

Crucially, a further autopsy was conducted by

members of Ôkyo’s circle, the rangaku scholars

Koishi Genshun and Tachibana Nankei at the

latter’s medical practice in Fushimi in 1783.12

Prior to and outside of these new medical

experiments, skeletons had been a common

currency of experience in harsh times, and a long-

time subject of Zen mirth and admonition. In the

much-reprinted Gaikotsu (Skeletons, 1457), written

by the eccentric Zen priest Ikkyû Sôjun (1394–1481),

the skeletons are shown joyfully enjoying every-

day human occupations and activities beyond the

grave (fig. 2).13

More usually, bone imagery related to the Zen

practice of kusôkan, the contemplation and

meditation on the nine stages of decomposition of

a corpse.14 On occasion, meditation could be

centred on a single aspect of the process of decay,

such as Itô Jakuchû’s Skull, painted in the

hatsuboku (splashed ink) manner of Sesshû

(1420–1506), for the Zen Muryôji temple (fig. 3).

This style, derived from the Chan “apparition

Andon 99 65

Fig. 2. Ikkyü Sojun, Ikkyü

gaikotsu, Osaka 1692

edition. Ehon.

© Waseda University Library,

Tokyo

paintings” of the Song dynasty, offers little to

distract from meditative contemplation of transience.

The ancient practice of kusôkan in, primarily,

Zen and Tendai was aimed at overcoming sensual

desire through disgust, and achieving

enlightenment through meditation on impurity

and transience.15 Its poetic elaboration (kusôkanshi)

dates back to the 6th-century Tiantai (Jap. Tendai)

master Zhiyi, with later versions attributed to the

great Song dynasty poet Su Dongpo (1036–1101),

and in Japan, to Kûkai (also known as Kôbô

Daishi, 774–835), the founder of the Shingon sect.

Illustrated versions portrayed the gradual stages

of female putrefaction with some, generally

gruesome variations; however the recumbent, but

entire skeleton was never the final stage of the

process, which would end either with the

disjointment of these bones or their final

dissolution into nothingness,16 elaborating the Zen

concept of death as non-being, a transition into the

void and future rebirth.17

Death and Buddhahood

Although Ôkyo’s skeleton is neither recumbent

nor gendered, its potential allusion to illustrations

of the Nine Stages of Decay cannot be ignored.

Whilst the original texts generally referred to an

anonymous corpse, by the 18th century, the

conflation of the Nine Stages of Decay with the

Tamatsukuri Komachishi sôsuisho (玉造小町子壮衰書,

Flourish and decay of Komachi from Tamatsukuri) had

become engrained.18 The earliest reference to a

painting of the decay of Komachi dates back to

1212, in a Tendai context. It has been considered

the prototype for ‘Nine Stages’ illustrations which

survive in medieval emaki (hand-scrolls), and in

Edo-period ehon (illustrated books) and paintings

(fig. 4).19

The 9th-century poet Ono no Komachi is listed as

the only woman member of the rokkasen (Six

immortal poets) in the Kokinwakashû (Collection of

ancient and modern poems), the first imperial

compendium of waka poetry compiled between

905 and c. 920, and as one of the sanjûrokkasen (36

immortal poets) in Fujiwara no Kintô’s anthology

of the early 11th century (fig. 5).20 Over one

hundred of her waka poems about love survive. In

addition, we have a number of late-medieval

Andon 99 66

Fig. 3. Itö Jakuchü

(1716–1800), Skull.

Kakejiku, sumi on paper.

© Muryoji, Kushimoto

legends and plays about her early life as a

celebrated beauty and court poet, and her old age

as a repentant mendicant. Komachi was reputedly

born in the Ono clan lands on which the Zuishin-

in is situated. She was also allegedly buried there

following her years of destitute secluded existence

in a brushwood hut in Ono. Her legacy within the

temple consists of a ‘letter mound’ of buried love

letters from suitors, as well as a statue of Jizô said

to be made by the poet, and composed of an

under-layer of love letters.21

The transgression for which Komachi repented

was not concupiscence, but arrogant cold-

heartedness. The karmic burden she acquired

originated from the broken hearts and suicides of

the suitors she invariably rejected, and from the

jealousy and resentment felt by the neglected

wives and children of those suitors, seeking

retribution from the gods. Her downfall was

precipitated by the death of Captain Fukakusa no

Shôshô, who had been made to brave the elements

and wait by Komachi’s door for a hundred

consecutive nights, expiring, unfulfilled, on his

way to the final night.22

As possession by angry spirits (onryô) could

lead to madness and impede the way to

enlightenment, the path to salvation was through

sange, an act of recitation and repentance before

the Buddha and before others, in order to obtain

keka, expiation leading to salvation.23 The earliest

extant text associating the poet with destitution

caused by arrogance was the Tamatsukuri

Komachishi sôsuisho mentioned above – a much

copied moral tale of worldly success, fall and

repentance, highlighting the transience of worldly

desires, which until recently was attributed to

Kûkai. In other legends Komachi’s search for

salvation continued beyond her physical death,

her sun-bleached skull speaking her sange to

passers-by on the roadside.24

In Kan’ami’s 14th-century Nô play Sotoba

Komachi (Komachi of the stupa), which draws on the

preface of Tamatsukuri, Komachi is described as

possessing hongaku or ‘innate’ Buddhahood.25

Seated on a ruined stupa which she had mistaken

for a tree-stump, the decrepit Komachi is possessed

by the spirit of the vengeful Fukakusa reliving his

hundred days. She then enters into a theological

disputation with a Shingon monk, displaying both

erudition and true repentance. The stupa or sotoba,

unrecognisably worn down yet still holy, by way

of a word play on sotoba (which also means

‘without’, ‘outside’) is equated with Komachi the

liminal figure, worn out and excluded by the

transient world, but not from salvation.26

Andon 99 67

Fig. 4. Kusözu, eighth stage.

18th century. Album leaf,

watercolour on paper.

© Wellcome Library, London

Fig. 5. Kanö Tan’yü (1602–1674), Sanjürokkasen: Ono

no Komachi, 1648. Colours on card. Konpirasan,

Shikoku.

The Tendai concept of hongaku, which posits

that every being possesses inherent, if latent

enlightenment, had its counterpart in the Shingon

notion of sokushin jôbutsu, or becoming a Buddha

in this life and this body,27 that could be attained

through initiation in esoteric knowledge (mikkyô),

and through practices including dharani

recitations, mudras (hand gestures), the repetition

of mantras, and visualisations, in order to grasp

the sanmitsu (the Three Mysteries of body, speech

and mind). Burning of shirokogi, understood as

‘white bones’, a central feature of the goma fire

ritual, involved the gathering and burning of kogi,

small firewood, and belonged to the ritualised

cycle of ten practices leading to ‘enlightenment in

this body’.28 In folk belief, Kûkai himself was

thought not to have died, but to have become a

Buddha ‘in his own body’, remaining non-

decomposed and seated in the lotus position in a

stone cave on Mount Koya, awaiting the advent of

Miroku, the Maitreya Buddha of the future.29

Keka rites and patronage

Ôkyo’s Skeleton relates to Ono no Komachi

visually and iconographically. A monk depicted as

a seated skeleton in a compendium of popular

texts on the impure (the Kusôshi genkai, volume 2,

of 1693) may have served Ôkyo as his model.30

Moreover, Mitsuzô’s Zuishin-in was the head

temple of the Ono Shingon sect, which was

founded in 991 by the monk Ningai, known as

Ame no Sôjô (the rain priest). Originally called the

Mandara-ji, Zuishin-in enshrined a dual mandala

inscribed by Ningai on the hide of a cow.31 It

became the Kujô clan’s family temple and a

monzeki (imperial temple) in 1599, eventually

overseeing both the Daijôji and Kûkai’s birthplace,

the Zentsu-ji in Shikoku.

Ôkyo’s familiarity with, and canonical

interpretation of this eschatological genre can be

seen in his early emaki Ten notions of death, known

from his sketchbook Shasei zatsuroku-jô (Album of

various sketches), and in the pair of scrolls Seven

blessings and seven tribulations, painted in 1768 for

Abbot Yûjô of the Tendai Enman-in.32

Whilst these early works follow the visual

canon of gradual degradation established in

kusôkan illustrations, the Skeleton’s naturalism in a

dematerialised context elaborates an utterly

divergent conception and intentionality. As a

secret (himitsu) icon, to be unfolded and viewed on

special occasions, the Skeleton must have served a

specific ritual function, as a meditational aid

preliminary to the rites of keka (repentance) and

kanjô (anointment or consecration), and to the

curative incantations of kaji (mutual empowerment).

The Skeleton’s allusion to Ono no Komachi

leads to the notion of repentance, and must be set

within the context of the Kujô’s Zuishin-in. The

rite of keka was a repentance ritual elaborated in

the 8th century, and designed to eliminate karmic

obstructions, placate vengeful spirits in times of

calamity, and yield practical benefits such as

health and bountiful crops. Moreover, keka prayers

for the health of the emperor assured the longevity

of the nation with which his fate was bound.33 Keka

was closely associated with the cult of Yakushi, the

healing Buddha, and it may be assumed keka

would have been practiced at the Daijôji since its

Tendai days.34

The Kujô family of courtiers served as hereditary

imperial regents from the Heian to the end of the

Edo period.35 Since the 10th century, it had

sponsored various rites for the protection of the

realm.36 Carefully preserved Kujô family

documents and ancestral diaries, such as the 10th-

century Kujôdono yûkai (Admonitions to Fujiwara no

Monosuke’s descendants), show them to have been

profoundly sinicised and well-versed adherents of

Onmyôdô, the Way of Yin and Yang, and of Daoist

divination.37 Although the kuge shohatto edict of

1613 had left the imperial court with greatly

diminished power and in straightened

circumstances, by the late 18th century, the Bakufu

had allowed, and even financed, a return to

splendour and to a revival of ancient rituals.38 Kujô

Naozane served as regent to emperor Go-

Momozono for a year from 1778, before serving

the youthful emperor Kokaku until 1787; a high-

ranking member of the Kujô family would have

served as abbot of the Zuishin-in.39 The

preponderance of Chinese literati and Daoist

elements within the Guest Hall’s decorative

scheme, demonstrate the preservation and revival,

in court circles, of Heian politico-religious

observances, well into the Edo era.

The Daijôji’s early Tendai history and later

adherence to Shingon, and the Skeleton’s semantic

Andon 99 68

associations with the Kujô and with Ono no

Komachi’s repentance, define Ôkyo’s image as a

preliminary meditation aid for the keka ritual for

the benefit of the individual, the community and

the nation embodied in the emperor. Its visual

elements lead to an alternative, complementary

reading, as preparation for the Shingon kanjô

consecration rite.

The Skeleton in situ: ritual function

and context

Ôkyo effectively uses new anatomical knowledge

to represent what is left once all that is transient

has been stripped away. The visually innovative

skeleton’s frontal perspective contrasts with the

conventional patterned rendering of waves: the

fixed and solid armature of the fleshless human

body is set against the turbulent oceanic surface

that masks the calmness and permanence beneath.

In folk belief mountains and sea were the

‘otherworld’ of ancestor spirits, gods and

demons.40 The ‘ocean assembly’ was the Buddhist

realm of non-differentiation, the pure and

‘boundless ocean of reality and truth’ lying

beyond the destructive transience of human

desires.41 In Kan’ami’s play Sotoba Komachi, Ono no

Komachi describes herself as a “strand of

waterweed”, and in one of her own poems as a

“buoyant waterweed”.42 The Skeleton floats, but,

unlike the buoyant waterweed, it is not carried by

the surface currents. Its bony armature is what

remains when all delusions and impermanence

have been stripped away.

The allusion to the Nô play may not be

fortuitous; Zuishin-in was, and remains a

Andon 99 69

Figs 6a & b. Maruyama

Ökyo, Carp ascending a

waterfall and Carp in a

pond, 1789. Diptych.

Kakejiku, sumi and light

colours on silk.

© Kameisan Daijö-ji, Kasumi-cho,

Hyögo

renowned center for Nô and gagaku performances.43

Whether Sotoba Komachi was performed there, or

even whether it was written for Zuishin-in, is

unknown; however, the theatricality of the

Skeleton, and especially the theatrical environment

created within the Guest Hall by its fusuma

paintings, cannot be ignored.

The Daijôji was one of a limited number of

branch temples empowered to ordain priests.44

Consequently the Guest Hall had a dual purpose,

as a set of secular reception rooms, and as a dôjô or

training space. The fusuma paintings constituted a

mandala, guiding the ordained through a

prescribed ritual process; all the associated scrolls

and screens have to be considered as aids to both

initiation and meditation. The force of prayer was

enhanced by imagery: in Kûkai’s own words,

“illustrations and images are none other than the

source of the ocean-like assembly”, the

visualisation of transcendent reality and non-

duality.45

The Shingon ideal of achieving satori

(enlightenment) or Buddhahood through praxis

had another iteration in a pair of kakejiku in sumi

and light colours on silk, also by Ôkyo, Carp

ascending a waterfall and Carp in a pond, painted in

the autumn of 1787 (figs 6a & b). The Chinese

theme of fish crossing the Dragon Gate46 is

transposed, as the carp does not become a dragon,

instead is shown swimming contentedly amongst

Amida’s lotus flowers. Given Ôkyo’s usual

realism, the ascending carp appears unnaturally

stiff, as if standing under the waterfall – perhaps

reflecting the waterfall austerities (taki no gyô) that

served as a purifying exercise preliminary to the

ritual practice of kaji.47

Kaji (mutual empowerment) was achieved by

‘penetrating the mandala’, which was perceived as

the “visual instantiation of Esoteric practice and

the very form of Buddhahood”.48 In esoteric

thought, the Ryôkai mandara or Mandala of the

Two Worlds, composed by the union of the

Taizokai or Womb World and the Kongokai or

Diamond World, represents “the universal form”

of all things and beings. Its systematic assembly of

deities was experienced as the visible, phenomenal

manifestation of the universe, and the representation

of the relationship between the self and the Buddha.

Visualising and circumambulating the mandara,

the disciple “forms a karmic bond with the deity

in a relationship of mutual empowerment, leading

to the realisation of his innate Buddha-mind”.49

At Daijôji, the mandara was not a scroll or a set

of statuary; instead the Guest Hall itself served as

a three-dimensional mandala. Nine halls surround

two central spaces, the Buddha Hall dedicated to

Jûichimen Kannon, and the Mountain Room

enshrining the local deity Mikawa daigongen. This

ensemble of eleven rooms forms the ritual space of

the Womb World Mandala.50 The Womb World

expresses itself as an eight-petalled lotus flower,

extending itself to the four corners and four sides

of the building, radiating outward from the central

image of Kannon, who was the emanation of the

great compassion of Dainichi Nyorai, the Great

Sun Buddha.51 Each of the eleven rooms embodies

one of the eleven faces of Kannon represented on

the fusuma paintings: for example, Lotus blossoms

by Ôkyo’s son Ôzui surround the statue of

Jûichimen Kannon in the central Buddha Hall, and

Puppies, plums and bamboo (fig. 7) by Ôkyo’s pupil

Yamamoto Shurei, facing the room from across its

paper partition, reflect the Laughing Face of

Kannon. The character for laughter 笑 contains

those for dog 犬 and bamboo 竹, and laughter is

enlightenment.52

The Guest Hall as a Womb Mandala denotes ri

理 or ultimate principle, meaning heart of

enlightenment, great compassion and skilful

Andon 99 70

Fig. 7. Yamamoto Shurei (1751-1790), Puppies, plums

and bamboo, 1795 (detail). Fusuma panel, sumi and

light colours on paper.

© Kameisan Daijö-ji, Kasumi-cho, Hyögo

means. It requires a complementary Diamond

World Mandala, representing the chi 智 or

knowledge, mind and effect, to become the Ryôkai

mandara, or complete manifestation of the

Buddha’s universe.53 The duad of Jûichimen

Kannon and Yakushi Nyorai of the Womb World

enshrined in Kameisan, Daijôji’s sacred mountain,

has its Diamond World counterpart in the shrine-

temple complex serving Mikawa daigongen,

Hachiman and Miroku at Mikawayama Mirokuji,

20 km south of Daijôji. This was Daijôji’s

pilgrimage destination, and is still known today as

a Shugendô (mountain asceticism) site and host of

an important flower festival.54

There is no record of Daijôji as an officially

sanctioned Shugendô centre in the Edo period.

However, the central location of the Mountain

Room in the Guest Hall posits the importance of

the localised cult of Mikawa daigongen, the

mountain deity served by both temples. Yakushi,

paired with Kannon, enshrined at Daijôji, assured

‘this-worldly’ benefits, preventing calamities,

protecting the health of the emperor and thus the

longevity and wellbeing of the country. Hachiman,

seen as the deified emperor Ôjin and usually

paired with Miroku, enshrined at Mikawayama,

sanctioned the divine legitimacy of the emperor,

appointments to political office, and was

particularly associated with the Fujiwara, and

therefore Kujô clan.55

It may be presumed the twinning of Kameisan

Daijôji and Mikawayama Mirokuji as a Mandala of

the Two Worlds and ritual centre pre-dated any

association with the Zuishin-in; however, this

configuration would certainly have had a certain

appeal to the Kujô family in the Edo era. Granted

the Zuishin-in as their family temple by Hideyoshi,

the Kujô may have wanted to keep a low political

profile under the Tokugawa.56 As hereditary

regents and masters of ceremonial within an

increasingly marginalised imperial court, they

may have found religious affiliations an effective

means of exercising a modicum of influence

beyond the imperial palace walls. In a time of

famine and disasters, fearful people travelled to

pray to the emperor outside his palace in Kyoto.57

Shingon rituals for the emperor, who embodied

the realm and whose fate was synonymous with

the nation’s, could offer the faithful a promise of

temporal relief.

Conclusion

The Guest Hall served as a training and ritual

centre for Shingon priests, and the rites it

conducted on behalf of its parishioners and for the

benefit of the nation, transformed the sanctuary

into a Pure Land, the locus of the divine.58 Its

images represent both the ‘sounds of the world’

and the objects of the infinite compassion flowing

from the central figure of Kannon. Within this

conception, as a meditational aid, the Skeleton may

be seen as embodying the aim of the practitioner’s

union with the Dharma Body and the perfected

body of self-enlightenment.59 As a ‘secret’

initiatory image, unfolded for special rites, its

power as icon is thereby magnified. It is not a

salvific image of human decay, nor is the skeleton

performing zazen. It is a body cleansed of all that

is transient, perishable and corrupt, reflecting the

purity of white bones; it is a being who has

realised his Buddha nature; it is the innate

Buddhahood of Ono no Komachi, selected for its

association with Daijôji’s head temple Zuishin-in.

The visually new dimension of scientific

modernity Ôkyo brought to this medieval icon,

paradoxically adds a numinous layer to the

embodiment of the Shingon concept of ‘becoming

a Buddha in this body’ through praxis, and to the

empowerment of prayer for the benefit of both self

and nation.

Acknowledgements

This paper would not have been possible without the

wealth of information contained in the temple’s website:

http://museum.daijyoji.or.jp/index.html, and the

extraordinary kindness, patience and advice extended to

me by Shinnô Yamasoba of the Daijôji, Professor

Gaynor Sekimori and Professor Timon Screech. I am

grateful to the Daijôji and the Murôji for their kind

permission to use their images, and big thanks are due

to my enthusiastic editor and my ever-tolerant family.

Andon 99 71

Notes

1. Sasaki, Jôhei & Sasaki Masako, Koga sôran: photographic archive of

Japanese paintings: Maruyama-Shijô school, vol. 1, Kokusho Kankôkai,

Tokyo 2000.

2. Sawada, Janine Anderson, ‘Political waves in the Zen sea; the

Engaku-ji circle in early Meiji Japan’, in: Japanese Journal of Religious

Studies, vol. 25, nos 1-2, 1998, p. 132. For images of variants on the

Skeleton: Sasaki & Sasaki, op. cit. 2000.

3. http://museum.daijyoji.or.jp/06story/06_05.html

4. http://museum.daijyoji.or.jp/04sakka/04_02/04_02_05.html

5. Anderson, Susanne Andrea, ‘Legends of holy men of early Japan’, in:

Monumenta Serica, vol. 28, 1969, p. 308.

6. Information provided via email by Shinnô Yamasoba, 6-12-2013.

7. Orzech, Charles, et al., Esoteric Buddhism and the tantras in East Asia,

Brill, Leiden 2011, p. 964.

8. Sasaki, Jôhei & Sasaki Masako, Daijôji – the art of Maruyama Ôkyo

and his school, Kokushokankôkai, Tokyo 2003, p. 179. Also:

http://museum.daijyoji.or.jp/06story/06_05.html.

9. Sasaki, Jôhei, Ôkyo and the Maruyama-Shijô school of Japanese painting,

The St. Louis Art Museum, St. Louis 1980, pp. 34, 47.

10. Musée Guimet (ed.), Konpira-sa, sanctuaire de la mer. Trésors de la

peinture japonaise, Kotohira-Gu, Kagawa-ken 2008, p. 17. Deal, William

E., Handbook to life in medieval and early Japan, Facts on File Library, New

York 2006, p. 235.

11. Screech, Timon, The shogun’s painted culture: fear and creativity in the

Japanese states, 1760–1829, Reaktion Books, London 2000, p. 58. Vaporis,

Constantine N., Breaking barriers; travel and the state in early modern Japan,

Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA. 1994, p. 53.

12. Beerens, Anna, Friends, acquaintances, pupils and patrons. Japanese

intellectual life in the late eighteenth century: a prosopographical approach,

Leiden University Press, Leiden 2006, pp. 95, 145. Genshun had

pursued Chinese studies with the Confucian scholar Minagawa Kien,

who belonged to Ôkyo’s circle, and Ôkyo provided the illustrations for

Nankei’s Tôyûki (Journey to the East) in 1795.

13. Steiner, Evgeny, Zen-life: Ikkyû and beyond, Cambridge Scholars

Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne 2014, p. 195.

14. Kanda, Fusae, ‘Behind the sensationalism. Images of a decaying

corpse in Japanese Buddhist art’, in: The Art Bulletin, vol. 87, no. 1, 2005,

p. 24.

15. Kanda, op. cit., p. 28.

16. Kanda, op. cit., pp. 24-27.

17. Milčinski, Maja, ‘Zen and the art of death’, in: Journal of the History of

Ideas, Vol. 60, no. 3, 1999), pp. 388-392.

18. Kanda, op. cit., p. 34.

19. Lachaud, François, La jeune fille et la mort, misogynie ascétique et

représentations macabres du corps humain dans le bouddhisme japonais,

Collège de France, Bibliothèque de l’Institut des Hautes Etudes

Japonaises, Paris 2006, p. 331.

20. http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/n/nanakomachi.htm; Chin,

Gail, ‘The gender of Buddhist truth. The female corpse in a group of

Japanese paintings’, in: Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, vol. 25, no.

3–4, 1998, p. 297.

21. Strong, Sarah M., ‘Performing the courtesan. In search of ghosts at

Zuishin-in letter mound’, in: Women & Performance, 12:1, 2008, pp. 79-95.

22. Strong, op. cit., 2008, p. 86.

23. Strong, op. cit., 2008, p. 83. Broma-Smenda, Karolina, ‘How to create

a legend? An analysis of constructed representations of Ono no

Komachi in Japanese medieval literature’, in: The IAFOR Journal of

Literature and Librarianship, 3:1, 2014, pp. 1-14, p. 12. Terasaki, Etsuko,

‘Images and symbols in Sotoba Komachi. A critical analysis of a Nô play’,

in: Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 44:1, 1984, pp. 155–184.

24. Strong, Sarah, ‘The making of a femme fatale. Ono no Komachi in

the early mediaeval commentaries’, in: Monumenta Nipponica, 49:4, 1994,

pp. 391-412, p. 400.

25. Chin, op. cit., pp. 296, 304; Kanda, op. cit., pp. 28-29; Terasaki, op. cit.,

p. 160. Broma-Smenda, op. cit., p. 10.

26. Broma-Smenda, op. cit., p.14.

27. Rambelli, Fabio, ‘True words, silence, and the adamantine dance. On

Japanese mikkyô and the formation of the Shingon discourse’, in:

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 21:4, 1994, p. 382.

28. Fabio Rambelli, lecture on the Goma fire ritual at SOAS on 7-3-2013.

Andon 99 72

29. Hori, Ichirô, ‘Self-mummified Buddhas in Japan. An aspect of the

Shugen-dô (“Mountain Asceticism”) sect’, in: History of Religions, vol. 1,

1962, p. 227.

30. Lachaud, op. cit., p. 333.

31. http://www.zuishinin.or.jp/about/index.html. Yamasaki, Taikô,

Shingon: Japanese esoteric Buddhism, Shambhala, Boston 1988, p. 55.

32. Lachaud, op. cit., p. 335. Screech, op. cit., p. 198.

33. Suzuki, Yui, Medicine Master Buddha, the iconic worship of Yakushi in

Heian Japan, Brill, Leiden 2011, pp. 23-24.

34. Suzuki, op. cit., pp. 22, 34; Bogel, Cynthea J., With a single glance.

Buddhist icons and early Mikkyô vision, University of Washington Press,

Seattle 2010, p. 263; Orzech, op. cit., p. 668.

35. Webb, Herschel, The Japanese imperial institution in the Tokugawa

period, Columbia University Press, New York 1968, pp. 113-114. During

their heyday in the Heian era, as the holders of Buddha relics identified

with the ‘wish-fulfilling jewel’ of Nyorin Kannon, the Kujō held Tendai

relic assembly rites for the imperial family in their own residence. The

Kujō had been instrumental in re-establishing the Shingon honzon

Daigo-ji , for which they were awarded the Zuishin-in by Hideyoshi in

1599, see Ruppert, Brian D., Jewel in the ashes. Buddha relics and power in

early medieval Japan, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2000,

pp. 217-219, 275, 355.

36. Ruppert, op. cit., pp. 275, 355.

37. Hino, Takuya, Creating heresy: (mis)representation, fabrication and the

Tachikawa-ryû, Columbia University, New York, PhD thesis 2012, p. 118.

38. Hall, John Whitney (ed.), The Cambridge history of Japan, vol. 4,

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1991, p. 148; Screech, op. cit.,

pp 148-156.

39. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sessh%E2%89%88%C3%A7_and

_Kampaku

40. Miyake, Hitoshi, Shugendô. Essays on the structure of Japanese folk

religion, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor 2001, p. 116.

41. Quotation from Ze’ami’s 1464 Nô play Seiganji, see Marra, Michele,

‘The Buddhist mythmaking of defilement: the sacred courtesan in

medieval Japan’, in: The Journal of Asian Studies, 52:1, 1993, pp. 49-65, p. 57.

42. Terasaki, op cit., p. 164.

43. http://www.zuishinin.or.jp/bunkazai/index.html; Strong, op. cit.,

2008, pp. 79-95.

44. Verbal communications with Shinnô Yamasoba of the Daijôji

(November 2012) and with Gomyô Seperic, priest at Yugasan Rendaiji,

formerly Yugai-ji, another ordaining temple (October 2014). The best

known ordaining temples were the Tendai Hiei, and the Shingon

Daigo-ji and Koyasan.

45. Terasaki, op. cit., p. 107. Bogel, op. cit., p.36.

46. Joly, Henry L., Legend in Japanese art, London 1908 (Amazon reprint),

p. 28.

47. Boyd, James W., The discipline of Pure Fire (Saika Gyô Ho) in Shintô-

Buddhism, The Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, N.Y. 2011, p. 13.

48. Bogel, op. cit., p. 6.

49. Yamasaki, op. cit., pp. 127-128.

50. http://museum.daijyoji.or.jp/05temple/05_03.html.

51. Ten Grotenhuis, Elizabeth, Japanese mandalas. Representations of sacred

geography, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1999, p. 59.

52. http://museum.daijyoji.or.jp/05temple/05_08.html (no.4)

53. Ten Grotenhuis, op. cit., p. 66.

54. http://www.hyogo-tourism.jp/english/fan_club/bn/2007_03.html.

55. Ruppert, op. cit., p. 52. Suzuki, op. cit., pp. 24, 92.

56. Kameda-Madar, Kazuko, Pictures of social networks. Transforming

visual representations of the Orchid Pavilion gathering in the Tokugawa Period

(1615–1868), PhD thesis, University of Hawaii, 2011, p. 113.

57. Burns, Susan L., Before the nation. Kokugaku and the imagining of

community in early modern Japan, Duke University Press, Durham 2003,

p. 26.

58. Bogel, op. cit., p. 221.

59. Yamasaki, op. cit., p. 42.

Andon 99 73