Music in computer games. Potential for marketing, utilization and effect

-

Upload

uni-giessen -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Music in computer games. Potential for marketing, utilization and effect

1

Music in computer games. Potential for marketing, utilization and effect

Claudia Bullerjahn

1. Problem approach and circumscription as regards content

Computer games1 are a significant phenomenon of the current popular culture. In the United States of America computer games are played in 75 percent of all households with almost equal division in sex (slightly maledominance) and rising mean age. Parents share their games with their children and vice versa. Still there are differ-ences in the utilization according to computer game genre and platforms (cf. Collins 2008b, p. 9). In 2003 computer games were played 75 hours per year more often than TV or rented DVDs were watched and accordingly radio was listened to (cf. Tessler 2008, p. 14).

Since every computer game utilizes music in some way, computer games are a significant socializing phenomenon that initiates an encounter with music. The mu-sic in computer games is nowadays almost as popular as certain TV show tunes, both are fixed in the cultural memory of society and mark golden childhood memo-ries. Certain points can be traced for the outlasting cultural presence: • The repetitive occurrence of the same melodies while restarting the game or

repeated gaming situations (e.g. level up) is characteristic of computer game music.

• Computer games are often played repeatedly over a longer period of time and through this connection with motor processes the music can fix in the memory perfectly.

• In diverse forms of popular music old gaming sounds are embedded. Therefore people who were not musically socialized by this kind of sound (chip music) can also get in touch with this early form of appearance of computer game mu-sic.2

The cross-promotion using synergies and the increasing media convergence have led to a respectable position of computer game music in the music business. The huge commercialization capabilities of computer game music are due to the fact that it is possible to tie in with the previous forms of media, such as movies and their music and music videos. Most important is that in the present day society the public has the 1 In the article on hand, the term ‘computer game’ will be used synonymously for any kind of

video game including console games and personal computer games. 2 Pac-Man (1992) by Power-Pill (alias Richard David James alias Aphex Twin) and Return of

the Ninja Droids (2005) by Desert Planet are examples for successfully embedding older gaming sounds in music.

2

possibility to act out a superior momentum by new communicational technologies. This shows in the social concomitants of globalization, diversification and individu-alization.

Up to the present day (2011), only little academic research has been done on computer game music. The existing studies are quite centered on the comparison to film music and the few empirical are mainly studies related to racing games. The term ‘computer game music’ in the article on hand will be used in its broadest mean-ing and includes besides music in the narrow sense every kind of atmospheric sound and sound effects, as well as sounds caused by non-player characters as long as it is no human language. So the topic incorporates fields that are normally called ‘sound design’, which can be seen as ‘composing with sounds’ (cf. Hug 2009).

At first, the above mentioned aspects of marketing and secondary usage will be in focus, while afterwards an overview on the use of music in narration based or plot centered computer games will be given. The special role of songs shall be consid-ered, as well as the popular orchestral computer game music. According to film music similar functions of computer game music, interactive game related functions shall be compiled. These functions arise from the adaptability of music to certain gaming situations which are caused by the player. Subsequent thoughts on the adap-tive computer game music and the utilization of rather repetitive stamped computer game music will be made. Basis for the considerations on possible effects of com-puter game music will be my model on the effect of music in audio-visual formats (p. 13), which is based on several empirical findings by various researchers (discussed in Bullerjahn 2001, 2010) and will be complemented by the results of already exist-ing empirical studies on music in computer games and an insight in a current pilot-study.

2. Marketing capabilities of music in computer games

Media convergence and cross-promotion

Music is gaining everyday importance in audiovisual media contexts, which can be led back to the increasing media convergence (cf. Münch/Schuegraf 2009): Techno-logically this is realized in the adding up of several single media into a multimedia capable end device (e.g. using digital audio and video data on mobile phones and playing computer games) or the mix-up of different transmission channels (e.g. availability of computer games or computer game soundtracks on the internet). Eco-nomically and organizationally the media convergence shows in the fusion of for-merly separated lines of business to globally acting businesses (e.g. computer game industry and music industry). Content-related media convergence reveals in related offers of different media platforms (e.g. media combinations: movie DVD-bundle with computer game attached), mutual quotation (e.g. visual or acoustic quotes of movie classics in computer games) or the reference to complement offers (e.g. commercial for computer game series Final Fantasy during the broadcast of the

3

same named movie, which is again based on the above mentioned computer game). A use-oriented media convergence is represented in the parallel use of several media or a single medium (e.g. listening to music and surfing the internet at the same time or playing a computer game respectively).

The secondary usage of computer game soundtracks has already reached un-thought-of forms: Newly composed computer game soundtracks are released on CD (e.g. Prince of Persia-game series) and get awarded with Grammys and MTV-Awards (e.g. Marc Eckō’s Getting Up: Contents Under Pressure3 and Darkwatch: Curse of the West4). The often orchestral instrumented computer game music and its composers meanwhile enjoy the same popularity as some film composers, while their music is performed in big concert halls by symphony orchestras (e.g. Final Fantasy VIII by Nobuo Uematsu with the choir intro Liberi Fatali and pop song Eyes on Me).

Synergies present themselves by the increasing cooperation between various fields of industries, like the computer game producers, record labels und music tele-vision: Nintendo combines its yearly Fusion Tour-Live-Performances of new and established rock stars with the possibility of testing brand-new computer games (cf. Tessler 2008, p. 18). In 2005, MTV founded its subsidiary MTV Games first releas-ing LA Rush. In the computer game Pimp My Ride, based on the same named MTV lifestyle show, MTV cooperated with Midway Games (cf. Tessler 2008, p. 24). As a consistent consequence in 2006 MTV bought the computer game development com-pany Harmonix, developer of Guitar Hero and RockBand amongst others.

Moreover typical examples for cross-promotion are several computer games that promote music celebrities as digitalized alter ego: As an example in 50 Cent: Bullet-proof, a semi-biographical computer game adaption of the rapper’s life, makes the player empathize the life of 50 Cent including fights, shooting and whippings (cf. Tessler 2008, p. 18).

Secondary usage of popular songs

Already at the beginning of the electronic media age, there have been several at-tempts to combine popular music genres and especially popular songs with other, especially visual media contents for reasons of consumer promotion and intensifica-tion of effects (cf. Bullerjahn 2009). Quite new is the combination of records with music related computer game series, as occurred in the simultaneous release of the album Death Magnetic by Metallica and various tracks out of this on the Xbox Live and the PlayStation Network for Guitar Hero (cf. Münch/Schuegraf 2009, S. 596). By means of the specific gaming controller in brand typical guitar shape the user is able to ‘re-enact’ the (partly simplified or extended) guitar part as quasi-contributor of the band. This is visualized by a self-designed Avatar and set to music by a si- 3 Music produced by Hip-hop-artist RJD2. 4 This computer game contains horror and western elements und uses amongst others Ennio

Morricones theme of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

4

lenced guitar track that is only activated if the key combination is correct. By press-ing the right colored button on the exact point of time as shown on a guitar neck on the screen, the player can gain points, while the difficulty rises from level to level. Practicing provided, the player may raise his or her expertise (cf. Svec 2008). The RockBand-series simulates the complete experience of making music in a rock band, made possible by a drum set, two guitar-controllers and a microphone like in SingStar. After unlocking all songs, which are ordered by increasing difficulty, more tracks or records can be purchased, downloaded and pasted in the own version of the game. Possibly in this way new consumers can be recruited, which are not socialized by this music but long for the games challenge and so get to know new music tracks intensely. Under these circumstances, the wish to learn to play a real electric guitar might arise to some adolescents, because the similarities are larger than the first impression may suppose (cf. Arsenault 2008).

Popular songs are sometimes also integrated in narration based and plot centered computer games, for example in the popular action-race-game-series Grand Theft Auto. In pure race games like Need for Speed the music can also be chosen freely by the player, but it is only used in the form of product placement and not game sup-portive. However, in Grand Theft Auto music is used in typical everyday situation like car rides through a virtual reality city, shopping in malls or while visiting friends, and can be chosen freely from several radio stations. Caused by the special compilation of the radio stations it is possible to deepen the specific attitude to life of the visualized age. On the other hand music, the radio anchorman’s comments and the commercials have the function of a reflexive comment on the gaming world and a satirical comment on the American culture and its consumption-oriented and violence affirmative attitude. Since Grand Theft Auto 4, a corporation with ama-zon.com makes it possible to purchase the songs as mp3s via the cell phone of the avatar.

Also the computer game series The Sims is exemplary for the secondary usage of music: On one hand the music was largely composed specially for the game und uses typical background music for the menus (exception: menu Firth of fifth with the song Selling England by the Pound (1973) by Genesis), on the other hand intimate sounds can be heard from the radio of the virtual reality world. Used are popular musical genres like pop, latin, heavy metal, but also piano pieces by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Special about the pre-existent songs is that the lyrics are changed to ‘Simlish’, the invented language of the Sims. Several popular bands produced version of their songs in Simlish, e.g. 2006 Depeche Mode for the song Suffer Well, and from that take advantage of secondary usage. Moreover the game contains the possibility to let the Sims make music by playing and practicing instruments, which are part of the furniture (e.g. piano).

5

Computer games as first release place of popular music

Nowadays popular music is sometimes first published within computer games, be-fore it is released as sound recording, if at all published this way: Such as 2004 the game Transformers, basing on the popular same-named toy, was released by ATARI in cooperation with Motown. Game-players that finished the game successfully received as a reward access to the debut single Wisbone by Dropbox, which is at the same time the main title of Transformers. The music video also contains pictures from the computer game (cf. Tessler 2008, p. 18). In how far a computer game can contribute to the marketing of unknown independent band’s song shows the surpris-ing case of the first person shooter Max Payne 2: The Fall of Max Payne (cf. Kärjä 2008): Released in October 2003, the game contains cut outs of the song The Late Goodbye by the Finnish group Poets of the Fall. The song was composed especially for the game and is partly presented by non-player-characters (NPCs). Only in the end credits is the song played in full length. In June 2004 Poets of the Fall released The Late Goodbye as their first single on their own record label. Although still with-out a record contract in January 2005, the first album Signs of Life reached number one in the Finnish pop charts. Apparently in this case the appearance of this song in a computer game strongly contributed to the fame and popularity of the band and also did not hinder their commercial success. Still it should be kept in mind that musicians normally only once receive a fixed amount of money for the utilization for their songs in a computer game (cf. Tessler 2008, p. 23). Although the ownership of the music for non-interactive usage remains with the musician, this does not al-ways this turns out in a record release or a commercial success. A sellout of prospec-tive musicians that contribute considerably to the entertainment of a probably com-mercially very successful computer game with their music cannot be excluded.

Often it is hard to tell, if computer games exist to promote popular music or if popular music is used to promote the computer games. It is becoming more and more uncertain, who is dependent on whom and who increases whose value. Addi-tionally it is remarkable that the amount of music videos on the music TV channel MTV decreased drastically in the last years and YouTube became their main plat-form. Anyway music videos are no longer the main means of advertising for music (cf. Tessler 2008, pp. 14–16).

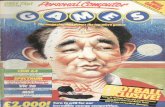

“The Atari can be considered the gramophone of our culture. […] The themes from ‘Pac-Man’, ‘Donkey Kong’, ‘Super Mario’ and ‘Zelda’ are as crucial to our consciousness as the riffs from ‘Johnny B. Goode’ or ‘Satisfaction’. […] Today, games can be our Beatles, our Sex Pistols, our Nirvana […] Videogames are the new rock‘n‘roll […,] the new hip-hop […,] the new house, heavy metal, R&B and punk. They are our culture. […] Videogames will become the new radio [… and] the new MTV.” (Steve Schnur, cited by Tessler 2008, p. 14)

This quote from Steve Schnur, leader of the music department and responsible per-son for computer game soundtracks at Electronic Arts (EA)5 and former part of the foundation team of MTV, shows the seamless integration of the computer game 5 Electronic Arts (EA) is one of the most important international developers, market creators,

publishers and sellers of computer games.

6

producers into the infrastructure of the music industry: computer game publishers operate via subsidiaries like A&R managers for new exclusive music from major and independent labels to back, for example, the menu screens of the FIFA-computer game series. Also a quantitative fact should be mentioned: globally seen, songs in computer games are heard more often than a number one radio hit which makes the utilization in computer games highly attractive (cf. Tessler 2008, pp. 15–17).

3. Overview of the utilization of music and sounds in narration based and plot centered computer games

Computer game genres and their auditory layers

Sean Zehnder and Scott Lipscomb (2006, pp. 246–248) examined a sample of 159 computer games across a variety of platforms and genres from the years 1985–2005 for their utilization of auditory elements. They wondered, if the loudness of music, sounds and speech could be chosen freely by the player, if surrounding sounds could be turned off completely, if a change from mono- to stereo-sound was possible, if popular songs where used and if the player could choose the music from a playlist. Problematical with this research method is, apart from the quite various seeming game choice, that classification of games into certain genres always is a quite sub-jective matter. The boundaries of a genre on one hand are differently definable, on the other hand many games cannot be assigned into the main game genres by Zehnder & Lipscomb (2006). Racing-games for example can both mark a form of sports game (actually it is called ‘motorsports’) and a form of simulation (simulating the driving of a car). Also it is not enough to assign games like the Grand Theft Auto-series to racing games, since the player is not forced to race against the police, he can also decide to cross the city while listening to music. The well-presented category of action- and adventure games, however, contains quite various games, as for example next to first-person-shooters also games, in which the killing of enemies does not play a leading role as rather the solving of tasks and riddles is important. It is not clear, in how far a boundary to the category ‘role play-games’ is justified, since the players of the action- and adventure games also interact in a world that is created by the game’s narration. Considering these limitations, the results of the multivariate variance analysis are remarkable: a significant main effect for the gen-res could be proofed. A comparison in pairs showed that a significantly higher por-tion of racing games and simulation games approves the possibility to adjust the loudness of music and sounds, compared to role play-games and action- and adven-ture games. Also the examined action- and adventure games did not use familiar popular music, which was used in about 40 percent of the racing and sports games, which additionally contain a playlist more often than other game genres (cf. Fig. 1).

7

Fig. 1: Options of the usage of music, sounds and speech in different computer game genres in comparison (cf. Zehnder/Lipscomb 2006, p. 247)

Film music-like and interactive game-related functions

Many authors emphasize the similarity between todays computer game music and film music (e.g. Zehnder/Lipscomb 2006). This is because computer game music, mainly in narration based and plot centered computer games, shall fulfill similar functions as film music does in the frame of the dramaturgy of a movie and its mar-keting. Functions of film music, as described in my model of functions as “intended effects” and differentiated in “meta-functions” and “functions in narrowed sense” (cf. Bullerjahn 2001, pp. 64–74), can be transferred to the functions of computer game music:

• Music can fulfill meta-functions according to the perception of nearly all computer games. They are time-, culture- and society-bonded. − perceptual-psychological: support of entertainment value and perceptu-

al motivation, general increase of activation level and delimitation from the ordinary.

− economical: addressing of a specific target audience by adjusting to its musical taste, all-over marketing of pop-icons and their musical prod-ucts.

• Functions in a narrowed sense always relate to a concrete computer game and its genre.

8

− dramaturgical: illustration of mood and atmosphere, strengthening of scenic expression, clarification of mental happenings, symbolization of feelings and passion, dimensioning of non-player-characters and avatars for their dramaturgical emphasis, clarification of personal constellation with leitmotifs, support and development of tension, clarification of a dramaturgical climax, rounding of scenes by musical end effects.

− epic/narrative: production of connections between strands of action, clarification of sense connections and coherences, bridging, unification, and strengthening of narration-tempo-manipulation, characterization of changes in the narrative level during flashbacks, anticipations, parallel actions or contrasting stories, evoking of associations to historical, geo-graphical and social aspects.

− structural: formal integration of the computer game, segmentation in different topics and levels, stress on motion sequences.

− persuasive: helping or rather stimulating empathy and identification processes, reduction of distance to the action, directing attention, per-petuation of concentration, easing of absorption and memorization of visual stimuli, emotional labeling of content or persons for building up preferences and desired behavior.

However, the main difference between movies and computer games is the fact that computer games are played actively rather than comprehended thoughtfully. In many action and adventure games music is used like conventional symphonic film music, still the music has to be modified and adapted to the ever changing action of the player and the virtual world (cf. Jünger 2008). The player may react to a musi-cally announced danger for his/her avatar by seeking shelter or getting ready for a fight. In plenty of games winning or losing situations (e.g. solving a riddle or death of the avatar) are backed with certain musical signals like in TV-game shows. So the main difference feature is the interactivity, because the player is actively involved in the game narration, if still within certain limitations. Consequently interactive game-play-related functions of computer game music must be considered. Roy Munday (2007) suggests a differentiation into three function areas: • perception of the game world (“environmental”): implication of space through

music and sounds to ease the navigation in the game’s space, increasing the degree of reality and credibility through sampled sounds, supplying functional references and feedback by any sound.

• “immersion” into the game world: − cognitive: music as sounding protective area that focuses attention on the

graphics and the game itself to forget interruptions and loose oneself in the game.

− mythic: utilization of leitmotifs and full orchestra scores (like in Wagner’s operas and Star Wars-movies) in role-play, action and adventure games to heighten reality of the cinematic experience and mystification to make the player loose his inhibition. Different to the movie’s perception the player is not placed within the movie’s story but in the world of the movie itself with all conventions like non-diegetic film music (cf. Munday 2007, S. 58f.).

9

• narration of the game world (“diegetic”): music and sounds help confirming visual messages or dissolving ambiguities in unclear messages. Games with − simple, non-cinematic narration normally use pop music soundtracks,

which often can be chosen from a playlist (e.g. in the racing game Gran Turismo 4). The music’s task is the maintenance of the player’s motivation as well as the focusing of the player’s attention which in the best case leads to an increase of performance.

− complex narration in reality-simulating environments like The Sims and Grand Theft Auto often use realistic sound and diegetic everyday-music (in particular popular songs), which are played by the radio. With this the closeness to reality and ordinariness shall be supported, in the game none-theless actions can be performed which are forbidden in reality, to danger-ous or physically and socially impossible.

− complex, cinematic narration (often in adaption to a movie) mostly use pre-composed soundtracks (e.g. the Lord of the Rings-series) in the sense of non-diegetic film music. Typical for the music of these games is the desig-nation of the change between safety and danger state (cf. Whalen 2004).

Beyond that, computer game music also shows some unique features according to Zach Whalen (2007, pp. 72–78): freeze frames, cut-scenes, starting menus, menu overviews and loading screens are next to the game-play typical points of use for computer game music, the last one is quite innovative in its interactivity. The suc-cession of interactions between player and game and not the rules of interaction construct the content of the game and therefore the sequential sound production during the game can be seen as a sort of aleatoric composition. Just when the player interacts with the game the musical product, the ‘computer game composition’, arises. Although the music is not directly connected to the player (exception: music based games with strongly pre-defined musical end products, which partly allow the playing of own songs). Games like the survival-horror game Silent Hill allow a con-nection between diegesis and player, which cannot be given within a movie: A bro-ken radio, carried by the avatar, shows by specific sounds the presence, type and nearness of monsters.

Composition of adaptive computer game music und its utilization

Game composers nowadays increasingly receive attention for their work. This may be caused by the fact that their music is not only derived from beeping sounds and unisonous artificial sounding melodies. Also, the first background medleys frequent-ly were derived from familiar melodies like Yankee Doodle, Steven Foster’s Camp Town Races and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Alla Turca, and for this matter were not original compositions. Today, composers take the challenge, which lies in ad-justing the music and sound effects to the dynamic request of the game and the needs of the player and thus in creating the computer game music interactively (cf. e.g. Hoover 2010). Reasons for the coining repetitions were originally the limited

10

memory sizes of floppy discs, cartridges and other memory media. Also, only a limited time budget for the composition was available and compositions were creat-ed by non-musicians but rather by software engineers who kept their focus on the game’s devolution and graphics (cf. Collins 2008b, pp. 1–6; also Collins 2008a).

According to Karen Collins (2008a, p. 8), the dynamic aspects of gaming sounds can be differentiated into interactive and adaptive audio: Interactive audio is defined as “sound events that occur in reaction to a player’s input”, for example a shot as a result of the pressing of a button. Adaptive audio describes sound events as a reac-tion to the game-play in dependence on a parameter (e.g. timing). This is “set by the game’s engine, rather than directly in response to the player” (e.g. increase of speed when the time of the level is nearly over).

The term dynamic music can describe every kind of music that is in a certain way capable to react to the game-play or that is composed in real time by the computer. Dynamic computer game music requires according to Jesper Kaae (2008, p. 75) in addition to traditional techniques of composing (1) “technical considerations regard-ing computer power/technology”, (2) “composing of tools and implementations”, (3) “functional considerations regarding aesthetics and user experience” as well as (4) special “compositional requirements of dynamic music, which often require a com-pletely new way of thinking about music”. Linear music is normally unfit for dy-namic computer game music because it is marked by a cause-consequence relation-ship and normally consists of a sequence of parts that must not be changed, short-ened or extended. Non-linear music is in the ideal case suitable since it is static and does not contain progression. This music just starts, normally has no beginning or end, the rhythm is monotone and the melodies (if existent) are sparse (cf. Kaae 2008, pp. 79–83).

Technologically seen music can be dynamic in two different ways, namely by variability (e.g. mobiles or generated music) and by adaptability. Adaptive music reacts on the game-play via the sending of events of the game engine to the music engine. On this occasion it needs to be veiled that the music sets in delayed because the music may, in the case of not fitting the picture, draw disapproving attention to itself (cf. Kaae 2008, pp. 83f.). The linearity of music can be softened by vertical changes within the music (e.g. changes in the instrumentation, amount of simultane-ous resounding tones) since they are more independent in time as horizontal changes (e.g. changes in the melody). Also possible is a constant change in the measure since the player cannot find any fixed points within the music (e.g. repeated accentua-tions) which is why the music never seems interrupted within shortenings. Discreet changes in the music can be achieved by actions and routines, continual changes by runtime parameter controls (RPC). The latter is quite simple in the combination with MIDI since the parameters pitch, timbre and volume can be controlled directly while melody, harmony and rhythm are not affected. A Shepard Scale (hearing illusion of a constant rising scale) can be helpful to keep the tension up as long as it is needed. Also useful is the consideration of intermodal analogies, especially related to bright-ness and size (cf. Kaae 2008, p. 87–90).

Tim van Geelen (2008, pp. 94f.) is convinced that adaptive music gains its partic-ular persuasiveness by the synchronism with the game-play rhythm (e.g. rhythm in

11

which the avatar is running, or speed the player is pressing icons) and in form of diegetic computer game music. This kind of music is played within the game world. A typical example is Grand Theft Auto (GTA) where different cars can be stolen. Every car has according to its type a fitting format radio station played. From GTA 3 onward these radio stations also contain commercials and comments of the radio presenter. Effective adaptive music techniques are in his opinion (cf. van Geelen 2008, pp. 96f.): • layering while separating the piece of music into several layers (e.g. percussion,

bass line, harmonies and melody) which are added up depending on the degree of tension. A disadvantage within this is that the effect is worn out quite fast and becomes predictable.

• branching while the starting point still remains the separation into layers, the selective combination of the layers on behalf of the gaming situation is im-portant. Unfortunately this technique is very time-consuming in the production and requires a lot of memory.

• transitions where several single pieces of music can be connected arbitrarily by small transition pieces. A disadvantage is that this is also very time-consuming since a multiplicity of transitions has to be composed.

• generative music, so to say an algorithmic composition. The computer is ‘taught’ to create and play certain variations of specific themes at random (e.g. via Markov-chains). Unfortunately only few composers master this program-ming and it requires a lot of memory.

• parallel composing which means that the composer writes two or three tracks in parallel and let them start at the same time (all are set on mute except one). Ad-ditionally it is planned to switch between the tracks at certain points of time. Advantages of this procedure are the small amount of memory required, quite good adaptability without fades and transitions and the portability to every mu-sical style. Still a great amount of music has to be composed, best one for every required emotion.

Unfortunately such thoughtfully composed adaptive music is still an exception. Although with the DVD there is a medium with comfortable memory space, the change from MIDI-sounds to game soundtracks played by expensive orchestras curiously enough leads to repetitions caused by money reasons. Nerved by repeated musical structures and longing for concentration several game-players turn off the music. Also it cannot be debarred that music, repeated over again in certain situa-tions, does not achieve its purpose sometime. If a monster never turns around the corner during dangerous sounding music, the music is superfluous and will surely be turned off (cf. van Geelen 2008, p. 93). Also, the present day consoles like Microsoft Xbox 360 Elite (2007) allow the changing of the game’s preset music to an own personalized soundtrack or the direct interaction of speaking or singing via headset.

In Scotland, Gianna Cassidy and Raymond MacDonald (2008, p. 763) asked 130 adolescents with an average age of 17 (return of questionnaires: 57,8%) and 206 young adults with an average age of 23 (return of the questionnaires: 91,5%) on their uses of music in computer games. Almost 33 percent of the participants named playing computer games as an everyday activity und the listening to self-selected

12

music during that was considered most important by 81 percent. However even 94 percent said that this is dependent on the game’s genre: Within sports games self-selected music was most important, during role-play the game’s preset soundtrack was more important. Self-selected music is considered less distracting and the game-play is enjoyed more. In the opinion of the respondents music has the function of creating images, altering moods and relieving tensions.

4. Effects of computer game music

Model on the effect of music in audio-visual media

If we deal with the effect of music in audio-visual media, it gets clear that next to the special qualities of music, contextual variables and characteristics of the recipient have to be considered for the valuation of these effects (see Fig. 2). Effects of the utilization of music in audio-visual contexts can develop automatically and precon-sciously regardless of the motives of utilization. If a blending of the music with the context is desired, a best possible fit is strived for, if not (asynchronous, divergent, contrasting), the deviation requires attention. Music that complies with the expecta-tions of the recipient concerning movie conventions promotes empathy and stays in the background; music that can retrieve emotionally charged memories (indexicality) however comes to the fore (cf. Bullerjahn 2010, p. 12).

The cooperation between eye and ear is ordinary and the strict separation between auditory and visual perception consequently an abstract construct. On higher pro-cessing levels, most probably in the mid- and interbrain, audio-visual impulses are integrated into a single occurrence because the organism tries to perceive infor-mation as a coherent and unambiguous unit. Due to fundamental perception qualities like size, volume, intensity, roughness, duration and density, both modalities can complete or replace each other by associative co-sensations and corresponding memory contents of the cortex. Also, the spatial order and the temporal sequence of stimuli are processed centrally. Here with the meaningfulness and the individual previous knowledge plays a major role: Although even in everyday life stimuli of different modalities constantly stream in, the dealing with visual two-dimensional, audio-visual media and their special historically changing conventions have to be learned first. In case of spatial divergence the visual sense normally dominates, in case of temporal however the auditory sense dominates, which is why speed and movement impressions normally are determined by auditory influences (cf. Buller-jahn 2010, p. 11f.).

Only via the complex interaction between large neural networks in different areas of the brain, music in audio-visual media can be attached to attention, structure, emotion, meaning, sense, evaluation, behavior and performance. Basic emotions like anger, sadness, pleasure and fear can be communicated pretty well by the acoustic parameters (e.g. tempo, volume, pitch, timbre) that influence the musical expression. Because of this, music normally is successful in the intensification of empathic pro-

cesseprotationatigatiambiaudiofavorbly hstylescognoccup(genrmemrent pand 2

I

es: if emotionagonist are sual reaction likeions show thaivalent/neutralo-visual produrs the cognitivhas an influencs, which are sitive schematpied music ore) expectatio

mory. Somethinpopular musi2008).

ndexicality

nal fitting mupported and t

e tears sometimat the musicall visualizationuct. Recent, fve availabilityce on the noticeldom heard,a is not exister music-pictu

ons and can bng similar coucal styles. (cf

recipiendemography

social rolepersonalityexperienceprejudicesattitudes

predisposition

usic is playedtherefore idenmes cannot bel expression ens determine frequent and

y and thereforced distance aare harder to

ent or hard to ure-relations abe processed unts for familf. Bullerjahn

muexprpara

collativecompprod

perfoassociati

t

effattestruemmea

seevalbeh

perfo

d, the felt simntification proe held back. Mespecially witthe emotionallively contex

e the generaliand closeness access than oactivate. This

are chosen. Thwithout grea

liar music like2010, p. 12f.;

usicressionametere variablespositionductionrmanceve content

fectentionuctureotionaning

enseuation

haviorrmance r

r

milarities accoomoted. This iMoreover, numth static, thin l overall imprxtualized musizations, what of musical styften played ons also explainhey promise ater load for e every day li; cf. also Bul

contextrelation to picturrelation to speecrelation to produ

fieldrelation to artist

imageelation to situatio

13

ording to the is why emo-

merous inves-n on plot and ression of an sic cognition t most proba-yles: musical nes, since the ns why cliché stereotypical the working

istenable cur-llerjahn 2001

trechuct

t's

on

fit

14

Fig. 2: Model on the effect of music in audio visual Media (revised according to Bullerjahn 2010, p. 12)

Disturbing, supporting or irrelevant? Music in racing and driving games

The connection between music and performance in racing and driving games is up to now the best-explored field. However, the starting points of these studies are quite different. The study by Adrian North and David Hargreaves (1999) examines both the effect of music on the driving performance and the contextual influence of musi-cal preferences. 96 British psychology freshmen from the age of 18 to 25 were ran-domly assigned to one of four experimental conditions. After seven minutes of prac-ticing, they had to complete five laps of a racing game backed with music of high or low arousal potential (140 bpm, 80dBA vs. 80bpm, 60dBA). The authors employed especially composed instrumental pop music which was adapted concerning its arousal potential with regard to tempo and sound level. Also in half of the cases a complex concurrent task (backward-counting) had to be fulfilled. It could be shown that the laps in the presence of the concurrent task always took longer than the laps in the absence of this task, while the ones with highly arousing music took the long-est. This also had an effect on the estimation of the game’s difficulty which seemed the most difficult with highly arousing music and concurrent task. Also, the better the subjects played, the more they like the music. North and Hargreaves explain their results with the limited processing capacity of the human being: both, the con-current task and the highly arousing music, require extra processing capacities, which leads to a deterioration of the driving performance. Problematic with this study is the fact that the investigator directly led the attention of the test subjects to the music and in everyday life people do not complete a complex additional task during a computer game. The ecological validity of the study’s results must there-fore be doubted.

For Masashi Yamada (2002) (cf. also Yamada/Fujisawa/Komori 2001) both the driving performance and the impression of the game are focused. Ten Japanese students from the age of 20 to 22 trained their driving skills in the game Ridge Racer V (time-attack-mode) with engine/tire sounds only for 2-3 months. Also, they were allowed to practice the game up to 30 minutes without music before the actual test started. The subjects were then asked to complete three laps under each of ten differ-ent experimental audio-conditions: In addition to the driving sounds, either one of nine musical excerpts (e.g. classical music, film music as well as the preset music of the game) or no music was played. Following each condition, the impression of the game-play had to be evaluated using a semantic differential with 15 bipolar scales and at the end of the whole test session the impressions of the musical excerpts us-ing a semantic differential with 18 bipolar scales. It could be shown that the lap times without music were the shortest compared to almost all other conditions. This is not surprising, since the training was performed without music at all. Astonishing on the other hand is the fact that current popular music and New Age music – even

15

if statistically not significant – adduces the best results, while the preset game music significantly has the most negative effect on driving performance. A principal com-ponent analysis was carried out and the factor loadings were plotted in a three-dimensional space, which revealed further results: music considered as neat had a less negative influence on the driving performance than disordered music. “Light” music results in a “bright” and “neat” impression of the game, “calm” music howev-er had a slightly “heavy” and “powerless” but still “neat” impression. Problematic with this study is the low number of test subjects and in hand with this the lack of possible generalization. Also, every person participated in every condition (even if in different order), what makes judgments on the impression of the game and the music strongly dependent on each other.

Study 2 Study 3

Audio condi-tions

Number of colli-

sions

Lap Time (s)

Lap Speed (mph)

Audio condi-tions

Number of colli-

sions

Lap Time (s)

Lap Speed (mph)

Self-Selected

3,0 (1,9)

99,2(7,4)

43,5(4,5)

Self-Selected

7,0(1,7)

100,2 (6.6)

47,5 (4,1)

High-Arousal (70 bpm)

15,4 (2,6)

101,6(5,0)

40,5(4,3)

High-Arousal (Vocal)

22,8(2,4)

99,8 (6,6)

47,6 (4,4)

High-Arousal (130 bpm)

18,7 (2,9)

98,8(6,5)

43,6(4,4)

High-Arousal (Instru-mental)

19,4(2,6)

102,8 (5,0)

44,3 (3,7)

Low-Arousal (70 bpm)

7,3 (1,9)

124,1(5,5)

25,1(4,4)

Low-Arousal (Vocal)

11,3(2,4)

121,5 (5,2)

31,5 (3,3)

Low-Arousal (130 bpm)

7,4 (1,9)

121,5(5,6)

27,5(3,9)

Low-Arousal (Instru-mental)

11,4(1,7)

120,1 (5,0)

29,1 (4,4)

Car Sounds

3,5 (2,1)

111,5(6,5)

32,1(3,0)

Car Sounds

7,5(2,7)

112,4 (6,1)

36,1 (3,2)

Silence 6,5 (2,2)

112,7(6,1)

31,9(3,4)

Silence 10,5(2,4)

113,7 (5,7)

35,7 (3,1)

Tab. 1: Arithmetic averages (standard deviations) of the performance parameters number of collisions, lap time and lap speed for the studies 2 and 3 (cf. Cassi-dy/MacDonald 2008, p. 766)

Gianna Cassidy and Raymond MacDonald (2008) searched for proof that, compared to preset music, self-selected music is more efficient both at increasing the game performance and deepening the game-play experience. In a first study, 125 Scottish participants from the age of 18 to 25 had to complete three laps of the game Gotham Project Racing 2 within one of five experimental audio conditions, namely: self-

16

selected music, High-Arousal music, Low-Arousal music (all backed with the car sounds), car sounds alone and complete silence. The experimenter-selected High- or Low-Arousal music was unfamiliar vocal popular music. The self-selected music also contained popular songs without exception that were of course familiar for the participants and preferred by them. For the evaluation of the driving game perfor-mance, number of collisions, lap time and speed were measured, while for the eval-uation of the game-play experience perceived distraction by music, enjoyment, ap-propriateness of music, liking and tension-anxiety were measured. The results of the study corresponded to the expectations: performance and experience were optimal when exposed to self-selected music. This music caused the highest enjoyment and the lowest distraction, suited the situation the most and lead to the least strain. The poorest effect was seen with the experimenter-selected music, especially High-Arousal music. Cassidy and MacDonald supposed as well that the detrimental ef-fects of this music were due to the competition for limited processing resources. In their second and third study they used the same setting, but additionally the special role of tempo and lyrics was considered. 70 Scottish participants from the age of 18-27 years had to complete (after a practice lap) three laps of the game Project Go-tham 3 under one of seven experimental audio-conditions: in study 2, additionally to the car sounds, fast or slow High-Arousal music, fast or slow Low-Arousal music, self-selected music, only car sounds or silence were employed; in study 3, addition-ally to the car sounds, vocal or instrumental High-Arousal music, vocal or instru-mental Low-Arousal music or rather self-selected music, only car sounds or silence. The experimenter-selected music was the same as in study 1, only re-arranged. The self-selected music was once again exclusively vocal and mostly from the field of pop music, but also classical music, Jazz, Folk, Metal and Dance. Here the results also corresponded to the expectations (cf. Tab. 1): An increase in tempo leads to faster performance, but also results in a higher number of collisions, especially for High-Arousal music. However, there was no significant effect of tempo manipula-tion on game-play experience, but the self-selected music led to the best perfor-mance and to the best game-play experience. Partially vocal music distracts more than instrumental music: The presence of vocals led to faster performance for both High-Arousal and Low-Arousal music and in addition participants caused more collisions while listening to High-Arousal music6. Interesting is the fact that self-selected music had no detrimental effects, although it was vocal music too without exception. The difference most probably is that the song lyrics were known before and for that reason caused no additional need of working memory. Also the music preferences and the sensation of ‘fit’ are strongly person-related variables:

„It appears that music is employed as a tool to achieve desired, goal-related changes in psy-chological and physiological state in the gameplay context.“ (Cassidy/MacDonald 2008, p. 766)

6 Remarkable is the circumstance that these studies replicate almost every result of the driving-

simulator-studies in the anthology Musikhören beim Autofahren, which Helga de la Motte-Haber and Günther Rötter already published in 1990. Unfortunately Cassidy and MacDonald forgot to mention this.

Funcperfo

Effec

The emethZehnfar mstudyers, amuchrandocondnal mgon hthe in54 anquestmovimusi

Abb.exhibp. 33betw

ctional game sormance either

cts of music in

existing studihodical wide rnder (2004) (cmusic contribuy were three sall about twoh woman) tooomly assigned

ditions the testmusic but backhad to be conn-game musicnd 85 secondtions placed iing a button cal or the visu

3: Graphic rbited a signifi9). The ratingeen 0 and 100

sounds, in thisr.

n action and ad

es on the efferange with emcf. also Zehndutes to the aessegments of tho minutes longok part, first fid to one of thrt subjects had ked with the g

ntrolled. In thecal soundtrackds depending in randomly oon a scrollbaual componen

epresentation icant main efgs via scrollba0.

s case car soun

dventure gam

ects of music motional effecder/Lipscomb sthetic experiehe computer gg. 89 high sc

filling out a deree different eto play the se

game sounds. e third conditik without the non the scene

order had to bar and five opnts were asked

of the mean ffect of groupar were conver

nds, seem to b

mes

in action andcts in focus. S2006, pp. 25

ence of a comgame The Lorchool and uniemographical experimental cections either In each cond

ion the test sunon-musical s

e. Directly folbe answered bpen questionsd.

scores for alp assignment rted by a com

be essential fo

d adventure gaScott Lipscom1–254) exami

mputer game. Brd of Ring: Thversity studenquestionnaire

conditions: in with or withoition the chara

ubjets only hasounds what tllowing each by an estimati

on the perce

l verbal ratin(Lipscomb/Ze

mputer interfac

17

or an optimal

ames show a mb und Sean

mined, in how Basis of their he Two Tow-nts (twice as e. They were

n the first two out the origi-racter of Ara-ad to listen to took between segment, 21

tion scale via eption of the

ng scales that ehnder 2004, ce into values

18

A repeated measure analysis of variance revealed significant differences in the inde-pendent variables ‘experimental condition’, ‘gender’ and ‘age’ and in their interac-tions, which verifies the influence of music. Especially within the scales ‘colorful‘, ‚dangerous‘, ‚relaxed’ and ‘simple‘, significant effects could be shown (cf. Fig. 3). The computer game looked more colorful with music than without or with music alone, and more over the addition of music led to a higher feeling of strain. While the computer game without music and the music alone both appeared quite simple, the combination of the two increased the perception of complexity. The perception of dangerousness was equally high for the computer game backed with music and the music alone, but lower without music. Though the qualified statement has to be made, that above all, this result goes for male participants. Female participants – possibly due to poor game-play expertise – perceived each stimulus equally danger-ous. The results prove the expected intensification of the aesthetic and emotional experience through the custom-made and adequately felt orchestral music of the film composer Howard Shore7. Unfortunately the experimental design does not allow the examination of immersion which was actually promised by the essay’s title. A real immersion may be hardly possible, if the test subjects are to play for only two minutes. Therefore the results would not be ecologically valid. In particular, the role-play and the passing of time are not taken into account.

In his study, Masashi Yamada (2008) especially investigated the effect of music on the triggering of fear, which is central in many survival-horror-computer games. Eight male and two female Japanese students from the age of 20–24 were asked to watch recorded game evolutions of two fighting scenes gathered from the computer game Biohazard 4 (alias Resident Evil 4), which normally do not contain any music, only sounds (gunshots, footsteps). Each scene was backed with each of eight musi-cal excerpts from the Biohazard 4 series and presented to the students. Moreover, every test subject had to evaluate the impression of every musical excerpt using a semantic differential, containing 18 seven-step bipolar scales. Following, the stu-dents were required to rate their fear for every shown game evolution by a seven-step scale and subsequent to this they were asked to evaluate it using a semantic differential, containing 15 seven-step bipolar scales. Principal component analyses were run for the impression of every musical excerpt, as well as that of combina-tions of game evolutions and musical excerpts. Afterwards, the factor loadings were plotted in semantic spaces. Since the differences between the impressions of the fighting scenes alone were quite low, but the scenes with different musical accom-paniments showed significant differences, Yamada interpreted this as a proof that impressions in survival-horror-games are first determined by music and not by visu-al information. Especially the “heavy” rated music provides “potency” and “dark-ness” for the impression of the fighting scenes and as a result causes the most fear.

7 Similar results were proved in many empirical studies from the area of film music and com-

mercial music research. Also these studies used similar methods (for an overview see Buller-jahn 2001, pp. 200–208). Unfortunately Lipscomb and Zehnder (2004) only mention the newer studies.

19

The very low number of participants and the fact that everyone attended all experi-mental conditions has to be criticized. However, it is even more aggravating that the test subjects did not play themselves but in a way only watched short-movies ac-companied by music. Especially with role-play implicating third-person-shooters this is relevant, since the player increasingly feels threatened personally and can develop concrete fear of certain monsters. In how far this can be affected by music could only be examined within other experimental settings.

In her qualitative study, Kristine Jørgensen (2008) examined the question, if the removal of implemented sound has consequences for the player’s orientation and awareness in the game world. Her starting point was the assumption that game audio is one of two channels, through which the computer system can communicate with its users. This would mean that turning off the sound would cause a lack of infor-mation concerning the user’s status. Jørgensen observed 13 experienced computer game players while playing the real-time strategy game Warcraft III and the stealth game Hitman Contracts. After about 20 minutes under normal conditions the sound was turned off and the players had to continue playing for an additional 10-15 minutes. The game evolution was recorded by video capture software. As a general result it can be said that without sound a loss of control was felt: the player felt left in the dark, helpless, amputated, disoriented, distanced and less engaged in the game, which means the sense of presence in the game world vanished. Although many believed beforehand that sound in a strategy game was less important than in a stealth game, they were taught better while playing without sound. Because the sense of spatiality disappears, enemies are harder to locate. In Hitman Contracts even the understanding of events within the game was restricted, since a feedback about the surroundings and the enemy’s status was missing. In Warcraft III the sound normally informs about the events taking place at the military basis and re-minds the player of started processes. Therefore sound is most beneficial in alarm or danger situations. The sound moreover enables listener to pick up a higher amount of information and simultaneously relieves the visual system. This may have an effect on reaction times and performances of the player. However, certain distrac-tions concerning the game experience were dropped and tasks could be worked off more systematically. Here personality related differences seem to be important. Maybe a low level of expertise or rather a low familiarity with the respective game goes along with great difficulties when playing without sound.

Richard von Georgi, Jasmin Lerm and Claudia Bullerjahn (2010) examined in a pilot study, in how far music affects or even reinforces the active game-play and the emotional-cognitive sense. Especially the question on the effect of music concerning fear and aggression in the genre of first-person-shooters was focused. In an experi-mental design with a pre-test, 29 students were tested while playing the first-person-shooter Unreal Tournament 3 in death match-mode and in three conditions (hard music, soft music, no music)8, all backed with the game’s own sounds. The heart rate was continuously measured by a pulse analyzer. As a starting point, data on the 8 The Industrial Metal-piece N.W.O by Ministry functions as hard music, the Smooth Jazz-

piece Nights Interlude by Nightmares on Wax was chosen as soft music.

demoaskedand tafter musiactuadata (basea tenaggrechangsituatthe omusiof theffecsupprexplaarous

Abb.tive-nmusi 9

ography and d. The equallythe anger andthat, and the gc over a five

al test lasting was analyzed

eline) for possndency effect cessive, anxietyge in directiotionally inadeoverall experic increases lee game. The g

cts could be sression or rathained by an esing music (=

4: Arithmeticnegative) meac conditions ( Bots are compumodus.

the personaly at the begin

d aggression (Sgame perform

e minute perioten minutes t

d by a repeatesible differencconcerning vay or anger tenn towards a n

equate music lience of the gess the negativgame performeen. Within ther a higher nemotional ovehard music) a

c averages anasured by the(von Georgi/L

ter controlled fig

lity (PANASnning recordeSTAI-state, S

mance (deaths,od of time (mtook place (med measure ances took placealence (p=0,06ndencies of thenegative emotled to an emogame-play. Hve affect and

mance was notthe condition negative affecerload that ovand impaired g

nd standard dee Self-AssessmLerm/Bullerjah

gures which can

, SKI, STAIed valence, aroSTAXI-state) w, kills) was nomap: Sanctua

map: Rising Sunalysis of vare. It could be s68): aggressive player. Moretional feeling otional conflic

Hard and therestabilizes mo

t influenced, bof hard musit reached less

vertaxed the pgame perform

eviations of thment Manikinhn 2010)

n be played by hu

-trait, STAXousal and potwere repeatedted. After trai

ary, 5 opposinun, 5 opponenriance after a shown that muve music did neover slow mu(see Fig. 4).

ct situation thaefore situationre the positiv

but gender andc, people withs kills. Perhapplayer in con

mance.

he variable van (SAM) with

uman beings in t

20

XI-trait) were tency (SAM) dly measured ining without ng bots9) the nt bots). The

a pre-analysis usic only had not increased usic caused a Possibly the

at influenced nal adequate

ve experience d personality th high anger ps this can be nnection with

alence (posi-hin the three

the multiplayer

21

5. Summary and prospect

The limitations of an article unfortunately only allow touching on limited themes and the closer inspection of a few examples. It is interesting to see that the develop-ments as seen in film music and music videos seem to repeat itself with view on functions and marketing. Here also music- and video-compilations were released, product placements were integrated in the products and the computer game music gained an overlapping everyday relevance (cf. Tessler 2008, p. 20). The researcher is faced with the same problem of getting internal data as it is with music in com-mercials, since the game producers probably carry out internal examination that are never published. Therefore marketing successes regarding popular music or rather computer games are hardly checkable. As mentioned above, the carried out effect studies are not ecologically valid because of their designs. Here multiple researches would be desirable. In various games, a soundtrack without music in a narrow sense would be more suitable. This is already the case with some first-person-shooters, however in some racing games preset-music seems to be completely unnecessary, since the player personalizes his music anyway and selects it situation-specific. Worthwhile would be an examination of the historical und ethnical effects. To sum up, one can say that the expounded findings can lead to the following theses, which of course should be covered by future analyses of computer game music and empiri-cal studies: • The current musical life increasingly takes place in computer games: computer

game music (along with film music) does not only constitute the current ‘classi-cal music’; computer games are also the new ‘MTV’ for the presentation of cur-rent popular songs.

• Depending on genre, music and sounds in computer games are employed both to simulate and to eliminate reality.

• Preset-soundtrack music in action- or narration-centered computer games tends to get boring with increasing expertise in game-play, whereas the interest in mu-sic and its production may be enhanced with increasing expertise in playing mu-sic-based computer games.

• Computer games with simple, non-cinematic narration do not need pre-selected music and players will chose their own personalized soundtrack for best perfor-mance. However, computer games with complex, cinematic narration are com-parable with feature films. In this case, a pre-composed adaptive music is indis-pensable for mythic immersion, spatial sense, feedback about game environment and an enemy’s status.

6. List of references

Arsenault, Dominic (2008): Guitar Hero: “’Not like playing guitar at all’?” Loading… 2, 2. URL: http://journals.sfu.ca/loading/index.php/loading/article/viewArticle/32 [10.11.09].

Bullerjahn, Claudia (2001): Grundlagen der Wirkung von Filmmusik. Augsburg.

22

Bullerjahn, Claudia (2008): „Musik und Bild“. In: Bruhn, H./Kopiez, R./Lehmann, A.C. (eds.): Musikpsychologie. Das neue Handbuch. Reinbek. pp. 205–222.

Bullerjahn, Claudia (2009): „Der Song als durchgängig bedeutender Bestandteil der Filmmusikge-schichte“. In: Jost, Chr./Neumann-Braun, Kl./Klug, D./Schmidt, A. (eds.): Die Bedeutung popu-lärer Musik in audiovisuellen Formaten. Baden-Baden. pp. 103–125.

Bullerjahn, Claudia (2010): „Nicht Subtext, sondern Hauptdarsteller: Musik im audiovisuellen Medienkontext und die Auswirkungen auf Jugendliche“. merz. medien + erziehung 54, 1, 10–15.

Cassidy, Gianna/MacDonald, Raymond (2008): ”The Role of Music in Videogames: The Effects of Self-Selected and Experimenter-Selected Music on Driving Game Performance and Experi-ence”. In: Miyazaki, K./Hiraga, Y./Adachi, M./Nakajima, Y./Tsuzaki, M. (eds.): Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Music Perception and Cognition. Sapporo. pp. 762–767.

Collins, Karen (2008a): Game Sound: An Introduction to the History, Theory and Practice of Video Game Music and Sound Design. Cambridge and London.

Collins, Karen (2008b): “Introduction”. In: Collins, K. (ed.) From Pac-Man to Pop Music. Interac-tive Audio in Games and New Media. Aldershot and Burlington. pp. 1–10.

Hoover, Tom (2010): Keeping Score. Interviews with Today’s Top Film, Television, and Game Music Composers. Boston.

Hug, Daniel (2009): „Ton ab, und Action! Narrative Klanggestaltung interaktiver Objekte“. In: Spehr, G. (ed.): Funktionale Klänge. Hörbare Daten, klingende Geräte und gestaltete Hörerfah-rungen. Bielefeld. pp. 145–169.

Jørgensen, Kristine (2008): “Left in the dark: playing computer games with the sound turned off”. In: Collins, K. (ed.): From Pac-Man to Pop Music. Interactive Audio in Games and New Media. Aldershot and Burlington. pp. 163–176.

Jünger, Ellen (2009): „When Music comes into Play – Überlegungen zur Bedeutung von Musik in Computerspielen“. In: Mosel, M. (ed.): Gefangen im Flow? Ästhetik und dispositive Strukturen von Computerspielen. Boizenburg. pp. 13–28.

Kaae, Jesper (2008): “Theoretical approaches to composing dynamic music for video games”. In: Collins, K. (ed.): From Pac-Man to Pop Music. Interactive Audio in Games and New Media. Aldershot and Burlington. pp. 75–91.

Kärjä, Antti-Ville (2008): “Marketing music through computer games: the case of Poets of the Fall and Max Payne 2”. In: Collins, K. (ed.): From Pac-Man to Pop Music. Interactive Audio in Games and New Media. Aldershot and Burlington. pp. 27–44.

la Motte-Haber, Helga de/Rötter, Günther (eds.) (1990): Musikhören beim Autofahren. Acht For-schungsberichte. Frankfurt am Main.

Lipscomb, Scott D./Zehnder, Sean M. (2004): “Immersion in the Virtual Environment: The Effect of a Musical Score on the Video Gaming Experience”. Journal of Physiological Anthropology and Applied Human Science 23, 337–343.

Münch, Thomas/Schuegraf, Martina (2009): „Medienkonvergente und intermediale Perspektiven auf Musik“. In: Schramm, H. (ed.): Handbuch Musik und Medien. Konstanz. pp. 575–604.

Munday, Rod (2007): „Music in Video Games“. In: Sexton, J. (ed.): Music, Sound and Multimedia. From the Live to the Virtual. Edinburgh. pp. 51–67.

North, Adrian C./Hargreaves, David J. (1999): “Music and driving game performance”. Scandina-vian Journal of Psychology 40, 285–292.

Svec, Henry Adam (2008): “Becoming Machinic Virtuosos: Guitar Hero, Rez, and Multitudinous Aesthetics”. Loading… 2, H. 2. URL: http://journals.sfu.ca/loading/index.php/loading/article/view/30 [10.11.09].

23

Tessler, Holly (2008): “The new MTV? Electronic Arts and ‘playing’ music”. In: Collins, K. (ed.): From Pac-Man to Pop Music. Interactive Audio in Games and New Media. Aldershot and Bur-lington. pp. 13–25.

van Geelen, Tim (2008): “Realizing groundbreaking adaptive music”. In: Collins, K. (Hg.): From Pac-Man to Pop Music. Interactive Audio in Games and New Media. Aldershot and Burlington. p. 93–102.

von Georgi, Richard/Lerm, Jasmin/Bullerjahn, Claudia (2010): Der Einfluss von Musik in Egoshoo-tern auf das Angst- und Aggressionsverhalten – Eine Pilotstudie. Poster presented at the Annual Conference of the German Society for Music Psychology „Creativity – Structure and Emotion“ at the Academy for Music in Würzburg from 7.–10. October 2010.

Whalen, Zach (2004): “Play Along: An Approach to Videogame Music”. Game Studies: The Inter-national Journal of Computer Game Research 4, 1. URL: http://www.gamestudies.org/0401/whalen [04.03.10]

Whalen, Zach (2007): „Case Study: Film Music vs. Video-Game Music: The Case of Silent Hill“. In: Sexton, J. (ed.): Music, Sound and Multimedia. From the Live to the Virtual. Edinburgh. pp. 68–81.

Yamada, Masashi (2002): “The effect of music on the performance and impression in a video race game”. In: Stevens, C./Burnham, D./McPherson, G./Schubert, E./Renwick, J. (eds.), Proceed-ings of the 7th International Conference on Music Perception & Cognition. Sydney. pp. 340–343.

Yamada, Masashi (2008): “The Effect of Music on the Fear Emotion in the Context of a Survival-Horror Video Game”. In: Miyazaki, K./Hiraga, Y./Adachi, M./Nakajima, Y./Tsuzaki, M. (eds.): Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Music Perception and Cognition. Sapporo. pp. 594–597.

Yamada, Masashi/Fujisawa, Nozomu/Komori, Shigenobu (2001): “The effect of music on the performance and impression in a video racing game”. Journal of Music Perception and Cogni-tion 7, 65–76.

Zehnder, Sean M./Lipscomb, Scott D. (2006): “The Role of Music in Video Games”. In: Vorderer, P./Bryant, J. (eds.): Playing Video Games: Motives, Responses, and Consequences. Mahwah NJ and London. pp. 282–303.