Who's in charge here?" communicating across unequal computer platforms

Multiple Regimes of Value: Unequal Exchange and the Circulation of Urarina Palm-Fiber Wealth

Transcript of Multiple Regimes of Value: Unequal Exchange and the Circulation of Urarina Palm-Fiber Wealth

Seediscussions,stats,andauthorprofilesforthispublicationat:https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236895951

MultipleRegimesofValue:UnequalExchangeandtheCirculationofUrarinaPalm-FiberWealth

ArticleinMuseumAnthropology·February1994

DOI:10.1525/mua.1994.18.1.3

CITATIONS

7

READS

104

1author:

BartholomewDean

UniversityofKansas

65PUBLICATIONS117CITATIONS

SEEPROFILE

Availablefrom:BartholomewDean

Retrievedon:13May2016

Multiple Regimes of Value: Unequal Exchange andthe Circulation of Urarina Palm-Fiber Wealth

Bartholomew Dean

This article examines the creation, circula-tion, and consumption of palm-fiberwealth among the Urarina, a semi-

nomadic hunting and horticultural society ofPeruvian Amazonia.1 Aguaje palm bast (Mauritiaminor, also known as swamp palm) and the frondspears of the Chambira palm (Astrocaryum cham-bira, A. munbaca, A. tucuma, also known asCumare or Tucum) have been used for centuries bythe Urarina to make cordage and to weave fabric(ejla), net-bags (siirad), and hammocks (amad).2

In Urarina society, women are the producersand primary regulators of palm-fiber cloth,3 orwhat Weiner has appositely called "a currency ofsorts" (1992:3). This essay demonstrates howUrarina cloth currency accrues value through itscirculation within multiple spheres of exchangeranging from the transmission of inalienable pos-sessions to the quotidian flow of commodities. Icontend that the production, circulation, and con-sumption of palm-bast goods is essential to thereproduction of Urarina society. Circulation ofpalm-fiber wealth perpetuates the past, organizesthe present, and facilitates an imagined future.

Like Thomas' account of "entangled objects" inthe Pacific (1991), this essay highlights the waysin which palm-fiber goods are socially consequen-tial. This involves an exploration of the ways inwhich palm-fiber goods, "can, must, or cannot becirculated. This is a matter not just of singularityor uniqueness," Thomas argues, "but of contextand narrative" (1991:100). Urarina palm-fiberwealth is assessed not simply in terms of idealtypes (e.g., commodity versus inalienable posses-sion) but rather as exchangeable valuables withinspecific historical and social milieux.

The knowledge surrounding the production ofwoven palm-fiber goods, and their place within thecosmos, forms an integral part of the Urarina'sstock of inalienable wealth. Drawing from Mauss'characterization of specific objects as immeubles(e.g., Maori cloaks, Samoan fine mats, and North-west Coast coppers), Weiner has proposed the

category of inalienable wealth to include thosesacred objects which condense historicity intostatements about present circumstances. Such ob-jects are infused with affective attributes symbol-izing the value of keeping them circulating withinthe family or descent group (1985:224; 1992; cf.Thomas 1991:22-27,65; Strathern 1988:161).

Inalienability, as Thomas notes, is an importantnotion, "because it incorporates the sense of singu-lar relations between people and things—in effectbetween people with respect to things" (1991:36).Urarina palm-fiber goods are important for theaffirmation of personal and collective histories;they serve as the objectified means for conveyingthe events of the past into the present time. Theimmobile value of palm-fiber fabric enhances thesignificance of the Urarina's past. This can per-haps be seen most clearly in Urarina mortuarypractices, a topic which I will subsequently explorein some detail.

But palm-fiber goods are more than inalienablewealth items: they have also been used strategi-cally to expand networks of exchange that extendbeyond Urarina society. Palm-fiber goods havelong been an important item of exchange betweendifferent local Urarina longhouse groups (kaj lait-jira), as well as between linguistic or ethnicgroups—such as the neighboring Omurana, Can-doshi, Jivaroan and Tupian peoples (see Requena1991:29-30). Moreover, since at least the seven-teenth-century establishment of the Jesuit mis-sions of Maynas, palm-fiber goods have beensignificant objects of exchange between theUrarina and the region's European and mestizo(anazairi) populations. The circulation of wovenpalm-fiber goods, such as cloth (cachibanco orcachihuango* fr. Loretano Spanish), net bags (shi-gra fr. Pastaza Quechua) and hammocks (hamacafr. Taino), has facilitated the importation of tradegoods into the Upper Amazon for at least threehundred years.

Conditioned by the exigencies of the region'sextractive economies, Urarina palm-bast goods

Museum Anthropology 18(1):3-20. Copyright C 1994, American Anthropological Association.

MUSEUM ANTHROPOLOGY VOLUME 18 NUMBER 1

1. Ajted f platting palm-fronds for temporary shelter thatching, 1992. (Photo Richard Witzig).

have become commodities—objects whose sociallyrelevant feature is their condition of exchangeabil-ity. For the Urarina, the commodity context drawstogether persons with often quite divergent con-ceptual understandings regarding the nature ofexchange, as well as the value of what is beingtransacted. This discrepancy is arguably most ap-parent in the context of what I deem relations ofunequal exchange or debt-peonage. Appadurai'sphrase—regimes of value—is useful here becauseit suggests that the exchange of palm-fiber goodsdoes not depend on a total sharing of culturalassumptions or interests between transactors(1986:15, 57). Thus, from the Urarina s perspec-tive, bast net-bags are infused with deep cosmo-logical import, while from the mestizo trader'spoint of view, the object's utilitarian potential isforegrounded.

Urarina men and women have traditionallyexpressed desires for cultural equivalents in returnfor their woven goods. One of the most importanttrade items introduced by missionaries andintrepid traders over the centuries has been im-ported cloth (kqjiune). Textiles—both indigenous

and imported—have long served as forms of "pay-ment" or "credit" in the various systems of debt-peonage characteristic of the Upper Amazon. Inthis regard, debt-peonage and Urarina handicraftproduction are examined here not as separatespheres of activity, but rather as inextricablylinked domains.

This essay shows how women's production ofpalm-fiber goods supplements the Urarina s bartereconomy. But my interest is not to assess women'shandicraft production as a cottage industry or asa secondary activity which is subordinate to themain activities of cultivation, production, and con-sumption in an overwhelmingly subsistence econ-omy. Rather, my concern is to map the voyage ofpalm-wealth goods as they pass through variousfrontiers of bestowal, barter, and commodificationwithin the context of unequal exchange relations.The notion of multiple regimes of value is helpfulin this regard because it yields insights into theflow of palm-fiber goods as commodities cross cul-tural boundaries (Appadurai 1986:15).

In this essay, I contend that Urarina women'slabor and the commoditization of their produce

MULTIPLE REGIMES OF VALUE 5

cannot be seen as economic isolates: the wealthitems which they produce move strategically be-tween persons and come to represent or embodythe claims and relationships which link them(Strathern 1987:4). I show how women's controlover the production and dispensation of palm-fiberwealth provides them with a certain degree ofautonomy. However, the essay concludes bydemonstrating that Urarina women's autonomy isultimately restricted by their total reliance on menwho are involved in exchange and barter relationswith non-Urarina groups and individuals (seeSeymour-Smith 1991:639; 1988).

The commoditization of women's handicraft pro-duction has reinforced Urarina patterns of in-equality, particularly with regard to gerontocraticinclinations and male dominance. Reliance on ma-ture men to manage the commercial exchange ofpalm-fiber wealth restricts spheres of autonomousaction among both women and junior men. Pat-terns of social inequality—both internally and ex-ternally generated—are mutually replicatedthrough the circulation of handicrafts within thecontext of unequal exchange.

Urarina society and unequal exchangeThe Urarina inhabit the Chambira-Urituyacu

water shed, a widely dispersed tract of humidlowland tropical rainforest.9 The native peoples ofthis area north of the Maranon river call them-selves Kachd. While total Urarina population fig-ures are unknown, I estimate their number torange between 4,000 and 6,000.

Urarina local longhouse groups or kaj laitjira,are distinguished by their lack of formalized rela-tions of power. Longhouse groups are structuredby intense factionalism, characterized by shiftingcoalitions among rival "big men" (kurana) andtheir "followers." Like their Jivaroan neighbors(Seymour-Smith 1991:641), relations betweenlocalized Urarina groups or bands are publiclyidentified with affinal ties and with competitivebig-man political relationships mediated primarilyby males. Group associations are informed bygender and age hierarchies that are reinforced bya discourse in which women (particularly whenyoung or widowed) and youths are portrayed asobjects to be exchanged.1|J Within the context ofpolitical factionalism, confrontation both betweenand within kaj laitjira frequently leads to fissionof the local settlement. Urarina factionalism andfrequent relocation are consistent with theirstrategy of political autonomy through disengage-ment.

The Urarina continue to be linked to the "out-side world" primarily through their exchange rela-

2. Ajeneu shaman with jaguar-tooth necklace, shell andtooth breast-bands, and parrot feather diadem, 1969.

(Photo: Bartholomew Dean)

tions with labor-bosses called patrones, and withriver-traders, known colloquially in the region asregatones. Some Urarina are occasionally involvedin the commercial extraction of lumber or in satis-fying obligations to provide bushmeats and fish(mitayo)*' to local patrones or to their mestizocompadres (fictive kin). Nevertheless manyUrarina communities have managed to achieve adegree of relative isolation from recurrent epidem-ics and the exploitation of their labor-power bycontinuing to rely on a ?trategy of flight and seclu-sion. '2 But the structure of the local labor market,coupled with the Urarina's own demand for indus-trial commodities, means that there is ultimatelyno escape: Urarina individuals, often acting onbehalf of their longhouse group, eventually enterinto unequal exchange relationships with labor-bosses and river-trader-

Debt-peonage and extractive economiesIn the Upper Amazon, extractive entrepreneurs,

including rubber barons, timber contractors, and

6 MUSEUM ANTHROPOLOGY VOLUME 18 NUMBER 1

itinerant traders have mobilized local labor-powerby relying on authoritarian patron-client relationsmediated through the perduring system of debt-peonage. Peonage, or what Gibson has called "theclassic Spanish-American labor device,' had nohistoric precedents in the Americas; labor was notin short supply until at least a century followingEuropean conquest (1966:158). In the heartlandsof the Spanish American empire, peonage lasteduntil the end of the eighteenth century, but at the"frontiers" it remained an entrenched technique oflabor recruitment with a veritable life and force ofits own. Indeed, for the past one hundred and fiftyyears, bonded-labor has flourished in those areas

area's principal form of commercial exchange sinceat least the mid-nineteenth century. The systeminvolves advancing capital or goods from one indi-vidual to another to enable the receiver to performextractive or productive activities. One of the mostsalient features of this system is that all produc-tive activity takes the shape of debt-cancellation(Gow 1991:96).

During the rubber boom (1870-1920), local rep-resentatives of international capital were providedwith funds or merchandise which was distributedto faithful suppliers {aviados).J River-traders andlabor-bosses with access to credit were soon ableto dominate regional commerce. In addition to

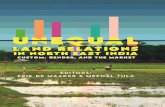

3. Infant hammock (amaa) with nut rattles from Chambira Urarina, 1993. Reproduced by permissionof the Peabody Museum, Harvard University. (Photo: Hillel Burger)

of Latin America which have been devoid of astrong state presence, such as the Upper Amazon,the Gran Chaco and the Yucatan peninsula (seeDean 1990; Langer 1986; Taussig 1986; Katz1990).13

The Upper Amazon's extractive economies arepredicated on vast series of exchanges linkingpetty commodity extractors to middlemen throughthe system of debt-peonage. Items provided oncredit to indigenous laborers have ensured thesteady flow of goods and people through regionaland international markets.14 Historically, UpperAmazonian commodities have been varied: includ-ing inter alia, slaves,1f sarsaparilla, barbasco (ro-tenone), coca, gold, lumber, and indigenouslabor-power to provide services like hunting andfarming. The practice of indebtedness, known inPeruvian Amazonia as habilitacion, has been the

transporting merchandise, traders facilitated thecommunication of people, news, gossip, and dis-ease over vast, sparsely populated territories.

In imagining the significance of debt-peonage inthe minds of Amazonian peoples during the rubberbonanza, Taussig is perhaps justified in suspect-ing, "that it was not the rivers that bound theAmazon basin into a unit but these countlessbonds of credit and debit [which] wound roundpeople like the vines of the forest around the greatrubber trees themselves" (1986:68). In the absenceof an effective juridical regime, owners of bonded-labor resorted to coercive terror to enforce compli-ance. Those who fled, risked violentretribution—as was clearly the case in the notori-ous Putumayo atrocities (Hardenburg 1913).

By the close of the nineteenth century, a smallnumber of families from frontier towns like Nauta

MULTIPLE REGIMES OF VALUE

and Iquitos had established control over the flowof goods and people in and out of the ChambiraBasin (see Wiener 1884:108; Castillo 1958;Quintana 1948; Kramer 1979:129). Urarina com-munities from the lower Chambira River werepreyed upon by slavers for rubber tapping. Theyresponded by disbanding and escaping to the farreaches of the Chambira headwaters. Those whowere captured became virtual slaves on "feudalis-tic" estates or fundos situated along the Maranonriver (Kramer 1979:15, 52-53).

During the first half of this century, the Patronfundo continued to thrive in the Chambira basinas the dominant mode of commercial production.However, within the past generation or so, thisauthoritarian mode of forest extraction, or patro-nazgo, has begun to decline. Increasingly, smallscale river-traders, or what might be called thepetty patron, have begun competing with theChambira basin's established patron families. Thesystem of advancing goods against debts(rijkigiiele rukurcha) remained largely intact onthe Chambira until at least the 1960s when factorslike the liberalization of rural credit, increasedrural literacy, and the proliferation of gas-poweredboat motors, gradually began transformingregional commerce.

Moreover, the introduction of petroleum explo-ration into the zone in 1974 has increased thedemand for Urarina products and labor-power.Though the presence of petroleum explorationteams has been sporadic, they tend to offer theUrarina better terms of trade for their produce andlabor than do the patrones or river-traders. The oil

exploration teams and petty patrones have contin-ued the tradition of trade in cloth and other indus-trial items, such as salt and shot-gun shells.

While the system oipatronazgo has been under-mined, it has by no means been destroyed. Atpresent, the Urarina are forced to produce a levelof surplus of trade goods to meet the demands ofthe itinerant labor and extractive economies.Urarina surplus goods typically include poultry,pelts, agricultural produce, and woven palm-fibergoods. Woven palm-fiber goods are of interest here,because of their proclivity to straddle various cir-cuits of exchange—Urarina palm-Fiber wealth iscapable of migrating through multiple regimes ofvalue.

Women and the production of palm-fiber wealthWeaving is a sine qua non of Urarina female

identity: the authority of elder women, orene bina,is legitimated through the control of palm-fibercloth and the technical knowledge necessary for itsproduction. Knowledge of weaving is transmittedmatrilineally Skill in aesthetic elaboration distin-guishes women's palm-fiber cloth production. Mas-tery of this productive activity is critical indiscourse about rights and obligations among andbetween women.

During their rite of menarche {na latua), pubes-cent females are taught the process of harvesting,preparing, and weaving {j is in ad) palm-fibers.Menarche among Urarina girls includes ritualseparation from society, achieved through cloister-ing the novitiate in a menstruation hut (jatd),

4. Ludrai-kujtiri twirling palm-bastcordage, 1993. (Photo: RichardWitzig)

8 MUSEUM ANTHROPOLOGY VOLUME 18 NUMBER 1

through depilation (latua), and through dietarystr ictures (see Guss 1990:228; Chevalier1982:294n). Acquisition of weaving knowledge isan essential part of female social maturation. Theskillful weaver is celebrated in Urarina society asone who fashions objects which not only bind theliving to one another and to the dead, but objectswhich can also be bartered for trade-goods.

As commodities, Urarina woven palm-fibergoods become valuable through the labor that they"congeal" (Marx 1978:307, 316). As with anyartisanal enterprise, the production of palm-bastgoods demands extraordinary investments ofmaterials and labor-power within each femaleproductive unit. Once harvested, the palm frond'ssoft fibers must be detached from the woodyportion of the frond and then dried in the sun. Thedesiccated strands are painstakingly twisted intofine cordage. Using vegetable dyes (roots, leaves,bark, seeds and fruits) the strands are either dyedshades of genipa-black (kuti), indigo/era-red(hidne, Bixa orellana) or left their natural creamcolor (Kramer 1979:102-103; Castillo 1958:14).

Woven on back-strap looms, palm-bast clothconsists of unbalanced warp-faced plain weaves.17

This fabric is woven with dyed palm-fiber warpfilled with un-dyed palm-fiber weft disposed inalternately colored bands or stripes (dar-dardrkuaka). Over a period of a month or two, awoman will spend a few hours at a time weavinga bolt of palm-bast fabric known in Urarina as ejld.This occurs in conjunction with ongoing productionof other woven goods, cultivation of the gardens,caring for children and other household tasks suchas cooking or making cassava beer (bardigue). Twomonths or more may be devoted to the wholeprocess of making a single ejld. The actual timespent weaving has been estimated betweentwenty-four and thirty-six hours (Kramer1979:103).18

The Urarina have used palm-bast fabric to makesleeping mats, cushion covers, women's skirts(sayd), men's trousers (lebdri), capes and mosquitonets (irigari, or hetegdti, which refers to cottonmosquito net) (Tessmann 1930:487, 442-443;Villarejo 1988:215; 1959:168; Steward 1963:520;Steward and Metraux 1963:575). Contemporaryuse of palm-fiber is restricted to fabric, net bags,hammocks and pillows (binjdu). Urarina beddingconsists of two widths of palm-fiber cloth sewntogether. Women also make fire-fans (inarii) androof thatching (ejlele tukunujui, banau).19 Apartfrom ligatures, clothing is now made fromimported fabric (kajiu) or obtained ready-made,often in the form of cast-off or second-handclothing.

Encoding value: The cosmos and the circulationof palm-fiber wealth

Urarina palm-fiber wealth items attain theirsacred attributes through cosmological referents,as well as through the special conditions surround-ing their production, which include the observanceof taboos during its manufacture. Menstruatingand pregnant women are precluded from collectingaguaje bast (ajld) and chambira fiber (disihe) inthe spiritually charged palm-swamps (ajldca). Thecosmological veracity of Urarina palm-fiber wealthdepends in part on color schema and geometricpatterning. The colors used are based on the tri-partite color contrast between black (ijchudi), red(lanajdi) and white (sumajdi), colors which play animportant role in Urarina beliefs and practice.20Atpresent, the relationship between the Urarina rit-ual clan system and transmission of patterns andcolor schemes is unclear.

Urarina palm-fiber goods employ patterningwhich relies on juxtaposing parallel bands of op-posed colors. This "parallelism" contrasts with theserpentine or geodesic designs of Urarina ritualceramic-ware (mirde) used to ingest hallucinogens(Banisteriopsis caapi or inunii, and Brugmansiasuaueolens or qjcad). Symbolic parallelism is evi-dent in other aesthetic realms, such as in women'sattire (opposition between red blouses and dark orblack wrap-around skirts), in the parallel layout ofthe longhouse's domestic platforms, and in men'sritual arm-scarification which leaves stratifiedbands of scar-tissue encircling the forearm.21

For the Urarina, the value of their woven palm-fiber goods is enhanced by these objects' ability to"encode kinship and political histories, making thepast valid for successive generations" (Schneiderand Weiner 1986:179). The production of wovenpalm-fiber goods is imbued with varying degreesof an aesthetic attitude which draws its authenti-cation from referencing the Urarina's primordialpast. Urarina mythology attests to the centralityof weaving and its role in engendering Urarinasociety. The myth of post-diluvial creation accordswomen's weaving knowledge a pivotal role inUrarina social reproduction (see Dean 1992).22 Butpalm-fiber wealth is not only valuable as a markerof the Urarina's sacred past—it is also an impor-tant medium for socially relevant exchanges.

The role of exchange in fostering sociality inAmazonia has long been recognized.23 Among theUrarina, the circulation and bestowal of palm-fibergoods is integral to the fulfillment of social obliga-tions and duties attendant to the salient lifeevents: birth, menarche, marriage and death. Cer-tain Urarina rituals which reaffirm individual andcollective continuities with the sacred past neces-

MULTIPLE REGIMES OF VALUE 9

liUntttiiM*

5. Woven palm-bast cord net-bags {si'trazi) from Chambira Urarina. The smaller one is made by women for men'sexclusive use in carrying hunting accoutrements: ammunition, batteries, and hunting talismans (herbals), 1993.

Reproduced by permission of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University. (Photo: Hillel Burger)

sit ate the exchange of indigenous, rather thanimported fabrics. Palm-bast goods accentuate so-ciality, particularly at times of life crises: theyauthenticate cosmological beginnings, expresscommon ancestry and heritage, and index socialhistories. Inter and intra generational transmis-sion of palm-fiber wealth further reproducesUrarina collective identity.

Palm-bast goods are signifiers of social identity:they are emblematic of age, status and gender. Forinstance, hammock use is limited to infants(kananedma), and to mature, married men(kijchdma). Women do not customarily use ham-mocks nor do they carry hunting pouches. Thesesmall, finely woven bast-bags are an importantaccoutrement of hunting and a symbol of mascu-linity for "established" men. Made by one's "wife"(or significant female partner), this bag is wornaround the neck to carry hunting talismans (tallaor puisanga) and the occasional shotgun-cartridge(see Farabee 1922:83; Lowie 1963:21; Steward and

Metraux 1963:603). The gendered production andconsumption of palm-fiber goods distinguishesmen and women's social identities. As such, palm-fiber wealth plays an important part in Urarinamatrimonial exchange.

Bridewealth transactions are common in thisuxorilocal, "brideservice society' (Dean 1993).Items exchanged between the groom and his wife^parents stress circuits of transaction that spanbeyond Urarina society. These items include: im-ported fabric; needles, clothes, chickens and alco-hol. Women's matrimonial exchanges involveobjects that stress continuities to the sacred pa^t.The bride is expected to weave or provide thenewlyweds palm-bast fabric bedding, as well asher husband's hunting-magic purse and eventuallya hammock. Women are also responsible for mak-ing cordage for shamanic garb—ehell necklacesand headdresses—as well as items indispensableto the hunt—blow-dart quiver straps and the ubiq-uitous woven net-bag.

10 MUSEUM ANTHROPOLOGY VOLUME 18 NUMBER 1

Large net-bags are at once supremely functionaland intimately associated with sustenance. Thisassociation is affirmed in Urarina popular mythol-ogy which alludes to the transmogrification of thenet-bag into Kirde, the two-toed sloth (Choloepusdidactylus)—a reliable source of meat for theUrarina. Perhaps the most valued palm-fiber goodamong the Urarina is ejld fabric which is employedto swaddle the young, to blanket lovers, and toshroud the dead. By adumbrating the centrality ofpalm-fiber cloth in one particular aspect of social-ity—death—I will now examine the specific rolewhich bestowal of palm-fiber goods plays in demar-cating social relationships and privileges amongthe Urarina.

Death and immobile palm-fiber valuablesUrarina women have symbolic power over the

spheres of the dead and the collectivity's mythicalbeginnings. However, by no means does this dero-gate from women's power or agency in determiningtheir present, nor does it undermine the controlwhich they exert over contemporary processes ofproduction and consumption. On the contrary,their control over the mortuary process accentu-ates their power.

In general, dispensation of a deceased woman'sestate, including most importantly her palm-fiberfabrics and bead necklaces, are administered alongmatri-lines, though secondary (non-sororal) co-wives may also inherit fabrics. Disputes mayemerge over counter claims to the deceasedwoman's ejld fabrics. However, certain posses-sions, such as personal sleeping mats and fire-fans(iharu), are so constitutive of the deceased's per-sonhood and identity that they are ultimately in-alienable (see Radin 1982:959ff.). These objects arethought to be so intimately bound up with thedeceased that they are removed from the sphere ofexchange and inheritance and rest permanently inthe ceremonial longhouse of the dead (qjtdn-abana).

In addition to being swathed in palm-fiber cloth,corpses are placed in a coffin fashioned from adiscarded canoe. The canoe-coffin is then buried ina shallow grave inside a longhouse cemetery lo-cated in the forest, itself a miniature replication ofthe luderi (communal longhouse). Above each bur-ial mound (ajtane kubai), a small platform iserected, modeled after the sleeping platforms ofthe longhouse. The deceased's sleeping mat isplaced over the mortuary platform, along withgender specific objects: ceramic cooking vessels(darue senjua) and firewood for women, and ritualgarb including parrot-feather headdresses (ku-maai), harpy eagle fans (tajaiji), shell chest bands

(rijkigui) and wooden ceremonial staves (ujtiya)for men.

This interment symbolizes the final leg in thevoyage of palm-fiber fabric through the possibletrajectories of inalienability or commodification.Interment of what can be deemed "personal" ejldfabric defies utilitarian notions of consumptionand commodification. However, at death, certainitems of ejld fabric are distributed within the de-ceased's immediate network, affirming notions ofutilitarian and collective consumption, and thus,solidifying the social bonds which continue to linkthe living.

The preceding analysis stresses how palm-fibergoods circulate according to traditional patterns ofdomestic consumption. But this is only part of thestory: palm-fiber goods have also found their wayinto networks of exchange which extend well be-yond the local longhouse group, and for that mat-ter, beyond Urarina society. Ejld cloth, along withother items of palm-fiber wealth, are still regularlyproduced for trade in quotidian goods necessary fordomestic consumption. It is in this regard thatUrarina palm-fiber wealth can be seen as migrat-ing through multiple regimes of value—from inal-ienability to commodification. Tb understand howpalm-fiber wealth items have migrated throughcommoditized circuits of exchange, I will now re-view the role which fabric has played historicallyin mobilizing indigenous labor-power.

Fabric and unfree labor in AmazoniaIn small-scale Amazonian societies, artistic and

ritualized production and exchange of woven palm-bast goods can be assessed as enclaved economiczones, "where the spirit of the commodity entersonly under conditions of massive cultural change"(Appadurai 1986:22). While it is true that in someregions of Amazonia the "spirit" of the commodityplays a primary role in the exchange of wovengoods, the commodification of palm-fiber wealthamong the Urarina has been considerably lesspronounced. In fact, the economic importance ofpalm-bast woven goods has gradually declinedamong the Urarina (Kramer 1979:102). Undoubt-edly, this has been a result of the commodificationof cloth which has rendered imported fabric a ma-jor substitute for palm-fiber clothing and mosquitonets.

The inalienability of Urarina palm-fiber wealthhas never been total: these items have compriseda significant part of the Urarina's stock of alien-able wealth for hundreds of years. As recently asthe 1940s, Catholic Priests visiting the Urarinawere presented with "heaps" of palm-fiber cloth.The surplus production of palm-fiber cloth

MULTIPLE REGIMES OF VALUE 11

probably antecedes the Spanish conquest when anelaborate trade network circulated fine cotton andpalm-fiber fabrics, ceramics, blowguns, venom,and sal t throughout Amazonia (Kramer1979:102).26

In the Maynas missions (1636-1767), locallyproduced goods, such as palm-bast mosquito netswere used by the Jesuits (Golob 1982:42).27 Indige-nous items, including lona cloth, were regularlysent to Quito in exchange for religious parapher-nalia (paintings and communion vessels).28 UpperAmazonian missions such as San Joaquin de Oma-guas, served as distribution points for trade-goodslike cloth, hammocks, icthyotoxins, tobacco, sugar,tools, curare, and salt29 from Moyobamba, Lamasand Quito (Martin Rubio 1991:XCI; Golob1982:232; Uriarte 1952 1:100, 184, 213, 217,11:161). At the missions, palm-fiber fabric fetcheddifferent prices according to its provenance.30

Throughout the nineteenth century, explorers ofAmazonia reported that cloth was regularly circu-lated by traders in return for indigenous labor-power and produce (see Muratorio 1991:33,156;Scazzocchio 1978:42; Oberem 1974:353; Weiner1884:98; Simson 1878:507-8; Orton 1870:176;Herndon 1853:160-61; Castelnau 1850:458; Smythand Lowe 1836:149; Maw 1829:157). Tocuyo(coarse cotton cloth)31 served as a general equiva-lent or medium of barter transactions betweenAmazonian peoples and traders until the introduc-tion of steam navigation (1850s) and the rubberboom further diversified commercial exchanges inthe region. Once in the hands of local consumers,tocuyo was used to make garments (the customaryuse of which had been forced upon many by themissions and by the old system of forced transferof goods orrepartosf2 and as a medium of exchangefor other transactions.33

Historical reliance on imported cloth, like othercommodities, such as metal tools and guns, has leftindigenous Amazonian societies in a quandary.Acceptance of imported cloth leads to a decline indomestic production of palm-fiber fabric for quo-tidian use as mosquito netting and clothing, as wesee among the Shuar, Quijo and Canelo (Harner1972:208; Oberem 1974:352-53; Broseghini1983:93-95). This in turn has reinforced local de-mand for manufactured cloth, thus increasing in-digenous reliance on mestizo intermediaries whoadvance cloth (and other goods) against debts.

For the Urarina, the exchange of woven palm-goods is a mark of sociality, and as such, figures asa strategic point of engagement with the region'ssupra-local extractive economies predicated on pe-onage. Moreover, differential access to importedcloth has exacerbated hierarchical tendencies

within Urarina society. In some instances, (par-ticularly those circumstances involving interac-tion with non-natives), the Urarina esteemimported fabric for its capacity to convey a lan-guage of prestige that relies on symbolic associa-tions which connote urbane worldliness, ratherthan native provincialism. Indeed, civility and thepossession of clothes are intimately associated inUrarina thought. A person without adequate cloth-ing is likened to one who eats un-salted food: bothindicate "savagery" in the minds of the Urarina. Inlocal parlance, this state of being is referred to withthe highly derisive ethnonym—Shimaco.34

The acquisition of new clothing is an essentialaspect of Urarina hierarchy. Procurement ofclothes reinforces their dependence on unequalrelations of exchange with mestizo traders. Oncein the hands of the Urarina, clothes are distributedaccording to gerontocratic criteria which favorsenior men and women. Most Urarina do not havemore than one or two "sets" or changes of clothes.Young Urarina children have very limited clothing.Given both the symbolic import and overallscarcity of imported garments, it is not surprisingthat clothes are donned until they are literallyspent (nasejtegd kajiune)—worn until they are nomore than threadbare rags. Tattered rags are thenrecycled forbeddingand patchwork. A concomitantof the trade in fabric is the circulation of needles,thread and scissors. For many households, scissorsare life-time purchases and thus very important tothose women who wield control over them.

Palm-fiber wealth, labor recruitment, andcommodity flows

The Urarina are active economic participants inthe chain of debt-peonage: they frequently pursuerelationships with patrones for the acquisition oftrade-items (rikele). In the Chambira, the virtualabsence of cash means that the Urarina vigorouslyseek out relations with traders because it providesthem with access to commodities of unsure supply,and because it suits their patterns of barter (Hugh-Jones 1992:69; see also Muratorio 1991:151;Siskind 1977:170-171).

The Urarina's reliance on trade-goods has foundhistorical expression in a sartorial idiom. The lureof cloth has drawn Urarina men, women and chil-dren into exchange relations with outsiders whosebehavior is animated by entrepreneurial desires toprofit from indigenous surplus production and for-est extraction. Inevitably, this has modified localrelations of production and patterns of consump-tion. Urarina consumption of industrial commodi-ties, such as cane alcohol (birinti), cloth, kerosene,batteries and shot-gun shells, has increased

12 MUSEUM ANTHROPOLOGY VOLUME 18 NUMBER 1

demands on male labor-power in the form of fellingtrees for the timber market, hunting game forexchange (mitayo) or producing "debt" crops, suchas rice. This in turn has increased women andchildren's workload to compensate for the periodicscarcity of male labor-power in the subsistencerealm.

The patron or trader will negotiate the recruit-ment of labor-power with the longhouse s head-man, typically electing the eldest male in residence(or if he has entered dotage, his most savvy son-in-law). The focal male or kurana represents thelonghouse in its negotiations with those interestedin the fruits of Urarina productive efforts: agricul-tural crops, gathered forest resources; timber;bushmeat and woven palm-fiber goods (net-bags,hammocks and palm-bast cloth). In addition toagricultural produce and poultry, handicrafts area reliable source of surplus production whichwomen can count on for the acquisition of trade-goods.'15 Moreover, compared with swidden agricul-ture, weaving affords women greater autonomysince it is a productive activity which is consider-ably less reliant on male labor inputs. But despitethe control women enjoy over handicraft produc-tion, they are nonetheless largely dependent onmen when it comes to the negotiation of commer-cial exchanges.

Each longhouse and its dependent householdstends to operate with traders or labor bossesthrough only one male kurana or "headman'' De-viations from this pattern do occur. A headman'ssons will often negotiate for themselves or on thebehalf of their unmarried sisters. In the absence

of a brother or father, a widow will turn to her sonsto manage the commercial exchange of her surplusproduction.

In collaborating with the singular kurana, thepatron is able to manage the labor of the long-house's co-residents, a management which isrealized through the periodic allocation ofmerchandise, and on rare occasions, cash. Theknowledgeable and adept patron will employ thediscontent within the longhouse and capitalize oncommunal disputes by playing one faction offagainst another. The most direct way to do this isto establish separate exchange relationshipsamong rival individuals or groups. While theirbargaining position is more restricted, the Urarinaemploy similar tactics when negotiating the mostfavorable rates of exchange offered by competingriver-traders.

Notwithstanding the fact that trade goods areearned through collective efforts, they are appor-tioned to various members of the longhouse by thekurana. Headmen use their trading relationshipwith non-Urarina to forge relationships of patron-age among their own people, especially their sons-in-laws or dependent un-married females.Merchandise is employed to establish additionalobligations, or debts within Urarina society itself.As Hugh-Jones notes, failure to acknowledge thisfact, "has led to an underestimation of the role andsignificance of Indian 'chiefs'and other brokers ormiddlemen in alliance with White traders"(1992:44; see also Levi-Strauss 1978:296;Goldman 1963:768-9; Gow 1991:100). On theChambira, the trader's principal clients become

6. Palm-fiber cloth (ey'/a) andpillow {binjau) from PangayacuUrarina, 1993. Reproduced bypermission of the PeabodyMuseum, Harvard University.(Photo: Hillel Burger)

MULTIPLE REGIMES OF VALUE 13

creditors in their own right to other Urarina indi-viduals within their immediate sphere of influ-ence. As such, the debt (rebeukon)—symbolized bythe exchange of trade-goods—assumes a life of itsown. "Debt-servicing" is reproduced internallyaccording to the confines of Urarina local politicalalliances.

Women's palm-fiber handicrafts are objectswhich figure prominently in the barter for trade-goods. While women do not enter into the negotia-tion publicly with patrones, their interests areactively represented by the male kurana. If thekurana were to arrange for the exchange of palm-fiber wealth with a trader, and only receive "male"goods (i.e., alcohol, or male clothing) or purelydomestic goods (matches, batteries, salt, etc.)when women's goods were predominant in the cal-culus of exchange, the kurana would do so at hisown peril. How much the kurana can conceal theterms of the negotiation is an open question, sincethe trade negotiations occur within a relativelypublic space in the longhouse.

Private arrangements undoubtedly do occur,especially between younger men seeking to widenthe constraints of their subordinate relations asjunior males and free themselves of debt-servicingto the elder males. It may be here, with a youngercouple that women's interests are under-represented, since it is up to their significantmales to make covert negotiations. These youngerwomen's labor-power may also be harnessed foragricultural production and consequently, theyreceive collective "remuneration" in the form ofdomestic consumption goods. Individual femalegoods (cloth, beads, mirrors, combs, etc.) may takea longer time to "trickle down" to them.

Viewed externally, patrones are labor contrac-tors. Nevertheless, the Urarina conceive of theirrelations with patrones essentially in terms of ex-change. In their discourse about working for thepatrones, Urarina men rely on images of exchangerather than labor control. In fact, the Urarina termnejkurijtuya, is synonymous with trader (regatori)and denotes the act of exchange or trade.36 This isnot to imply that the Urarina are unaware of thecoercion and inequality in their relations withpa-trones and river traders, nor is it to suggest thatthe Urarina do not employ as much cunning andvice in their dealings with traders. It does mean,however, that honoring debts is constantly de-ferred on both sides and "settlement" is oftenachieved through violence, flight or inter-genera-tional debt transmission. The surety of repaymentfor goods advanced lies in the generalized under-standing that credit can, like the rivers of theChambira, dry-up.

Urarina resistance to unequal exchangerelations commonly takes the form of heel-drag-ging, and occasional outbursts of violence. TheUrarina have also resorted sporadically to de-nouncing unequal exchange with patrones andtraders by relying on pr ies ts , radio an-nouncements and legal declarations. Seldom hasthis led to the resolution of debts. More commonly,it has simply prevented particularly abusive trad-ers from "doing business" in Urarina territory fora limited period.

The Urarina are fully cognizant of the fact thattheir inalienable possessions, such as palm-fibergoods and bushmeats are systematically being al-ienated. This provokes ambivalence, and in someinstances, profound apprehension. Urarina aware-ness of unequal relations of production and ex-change customarily finds expression in their vividmythology about the circulation of commodities.Given the immense divide between the production,circulation, and consumption of commodities onthe Chambira, and their manufacture and dis-semination in supra-local economies, it is not sur-prising that Urarina narratives accounting for theorigin and circulation of trade-goods are particu-larly extraordinary. Fantastic mythologies are in-evitably generated by Urarina laborers who inmany cases are totally alienated from the circula-tion and consumption logics of the goods they pro-duce and consume (Appadurai 1986:48; see alsoGuss 1986: 419-22; Brown and Fernandez 1991:53;Muratorio 1991:43; Hugh-Jones 1988:143-45;1992:72 fn. 18)

For the Urarina, the mythological domain pro-vides the intellectual space for the expression ofcountervailing impulses: the ineluctable pull ofimmobile valuables on the one hand, and the forcesof impersonal chattelization on the other. The lat-ter pull, which threatens to break the ties whichbind the living to both the past and an imaginedfuture, is neutralized in the arena of myth whichprivileges the reciprocity of gifting over that ofcommercial exchange.

Conclusion: The circulation of Urarinapalm-fiber wealth

This essay has suggested that the concept ofmultiple regimes of value is worthwhile because itprovides insights into the circulation of commodi-ties across diverse cultural frontiers. Drawing onrecent elaborations of Simmel's work on the natureof economic value, I have explored the multipleways, "in which desire and demand, reciprocalsacrifice and power interact to create economicvalue in specific social situations" (Appadurai1986:4). In this regard, I have argued that Urarina

14 MUSEUM ANTHROPOLOGY VOLUME 18 NUMBER 1

woven palm-fiber goods are significant because oftheir propensity to migrate through various orbitsof exchange. In particular, this essay demon-strated how women's woven palm-fiber goods caninhabit both spheres of commodification andinalienability.

As a class of objects, palm-bast goods mediatebetween overlapping spheres of exchange. Attimes, palm-fiber wealth can profitably be seen asinalienable possessions: there are specific socialcontexts when its circulation is restricted toexchange within Urarina descent groups. Themost extreme form of restricted transmission ofpalm-fiber wealth is apparent in Urarina mortu-ary practices. Interment of "personal" palm-bastfabric resists utilitarian conceptions of consump-tion and commodification. Nevertheless, at death,particular items of palm-fiber fabric are in factredistributed within the departed's immediatenetwork, thus validating notions of both utilitar-ian and collective consumption, while also solidi-fying the social ties which continue to bind theliving.

As exchange valuables, palm-fiber wealth itemsalso occupy the other end of the spectrum ofexchangeability: the commodity state. Thecommodification of woven palm-fiber goods is aresponse to the introduction of alternative rela-tions of exchange, namely debt-peonage. Palm-fiber goods are a dependable source of surplusproduction which women can rely on for theprocurement of barter-goods. The Urarinaexchange palm-fiber goods with traders for indus-trial products needed for domestic consumption(cloth, scissors, metal-pots, fish-hooks and line,etc.) or for purely "female" consumption (e.g.,beads).

The very embeddedness of Urarina woven palm-fiber goods in the cosmological and the practicalspheres of social life, coupled with the exigentdemands of debt peonage, have led to the diversi-fication of Urarina property rights and commodityproduction. By their very nature, articles whichdepict aesthetic or sacred qualities are usually notallowed to inhabit the commodity state for verylong. Although palm-fiber cloth is regularlyremoved from circulation through mortuary rites,Urarina palm-fiber wealth is neither completelyinalienable nor fungible, but rather is a mediumfor the expression of labor and exchange withinUrarina society. Indeed, the circulation of palm-fiber wealth stabilizes a host of social relation-ships, ranging from marriage and fictive kinship(compadrazgOj spiritual compeership) to per-petuating relationships with the deceased andwith extractive entrepreneurs. In exploring the

interstices of labor and exchange relations throughthe mediation of palm-fiber goods, I have illus-trated the ways in which cloth (indigenous andimported) migrates through multiple regimes ofvalue. Finally, by focusing on woven palm-fiber,the article has elucidated important aspects of thesocial production of female wealth. •

Acknowledgements

This essay was first presented at a panel entitled "Studiesin Commodification" at the joint meeting of the American Eth-nological Society and the Council for Museum Anthropologyheld in Santa Fe in April 1993 on the theme of "Arts and Goods:Possession, Commoditization, Representation." The research onwhich this paper is based was conducted over a twenty-threemonth period from 1988 to 1993. While in Peru, I was affiliatedwith the Centro de Investigacion Antropologica de la AmazoniaPeruana, Universidad Nacional de la Amazonia Peruana, Iqui-tos. I would like to acknowledge the financial support of thefollowing institutions: Department of Anthropology, HarvardUniversity; Sheldon Travelling Fellowship, Harvard Univer-sity; Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology; HE-Ful-bright Fellowship; Fulbright-Hays Fellowship; Wenner-GrenFoundation; Emslie Hornimam Scholarship, Royal Anthropo-logical Institute; Tinker Foundation; the Sigma Xi ResearchSociety; and the MAPFRE America Fundacion. In addition togiving me the time to write this paper, a Mellon Dissertationaward has enabled me to begin writing up the results of thefieldwork.

The development of my thinking on social inequality andexchange has benefitted from discussions with many people,including: Michelle A. McKinley, Paul Gelles, Ken George, Eve-lyn Hu-Dehart, Jay Levi, Herminio Martins, David Maybury-Lewis, Sally Falk Moore, Silvia Pedraza, Peter Riviere, ChrisSteiner, and Nur Yalman. In South America, I warmly acknow-ledge the intellectual guidance and friendship of Mauro Arirua,Frederica Barclay, Alejandro Herrera, Jorge Timoteo, and Fer-nando Santos. Dr. Richard Witzig kindly donated his medicaland photographic expertise to the project. My thanks for assis-tance in the analysis of the materials to Monni Adams, T. RoseHoldcraft, and Kathy Skelly of the Peabody Museum of Archae-ology and Ethnology, Harvard University. I appreciate the as-sistance given by Martha Labell of the Peabody Museum's PhotoArchives, and the efforts of Hillel Burger who photographed theUrarina artifacts now in the Peabody Museum's permanentpossession. This paper would not exist if it were not for my wife,Michelle A. McKinley, and Maxwell, as well as our many friendsin the Chambira Basin . . nadiara kumazai . nadiara ninakujkudicha.

Notes

l . The Urarina have received exceptionally little atten-tion in the ethnographic literature and only sporadicreferences in the encyclopedic "genre" of PeruvianAmazonia (see Raimondi 1863; Farabee 1922; Espi-nosa Perez 1955; Girard 1958; Chirif and Mora 1977).Accounts of the Urarina are limited to the data re-ported by Castillo (1958, 1961), by Tessmann (1930)in his magnum opus Die Indianer Nordost-Peru, andto the erratic and idiosyncratic observations of mis-sionaries (Gibal 1925; Izaguirre 1925; Quintana 1948;Villarejo 1988). Recent works on the Urarina provideuseful survey information (see Kramer 1977, 1979-Ferrua Carrasco, Linares Cruz andRojas Perez 1980)To date, spoken Urarina or kachd eye, remains one of

MULTIPLE REGIMES OF VALUE 15

the last unclassified languages of Amazonia (see Cajaset.al. 1987; Wise 1985). Urarina words appearingherein rely on a phonetic system closely approximat-ing spoken Spanish which Timoteo, McKinley and Ideveloped over the course of our fieldwork.

2. The use of cotton for weaving was also prevalent inAmazonia. Cotton weaving predominated among theT\ipian, Cahuapanan and Panoan peoples of the upperMaranon, and middle Huallaga regions. TheArawakan-speaking Piro and Machiguenga, as wellas the Panoan-speaking Conibo and Shipibo collectedwild cotton for weaving their cushmas (gowns). Alongthe upper Amazon and its tributaries, cotton was lessfrequently used, while along the Rio Negro, it wasvirtually absent. Cotton was utilized sparingly amongthe Western Tlicanoans (Lowie 1963:24; Steward1963:522; Steward and Metraux 1963:544, 568; Fara-bee 1922:9, 57, 82, 97). Maw found that cotton, thoughpresent throughout the montana, was most plentifulat Lamas, Tarapoto, and Sapo. It was routinely usedfor making sackcloth, or lienzo. According to Maw, thefinest and most expensive cotton came from the Ucay-ali, and was "as soft as silk" (1829:98).

3. My use of the term cloth follows Weiner's definitionand consists of all objects made from fibers, threads,bark and leaves (1992:157). Thus, in Amazonia indige-nous cloth includes items as diverse as: TAikano bark-cloth; Yagua cord hammocks; and Urarina palm-fiberfabric and palm-leaf mats. Weiner has examined howvaluables, such as soft goods like cloth, and "hard"objects like bones, can augment the influence andprestige of elites (1985). She illustrates how textilescan serve as a medium of exchange, replacing "hard"valuables like precious metal coinage, iron bars orshells. For the Andes, Murra has underscored theimportance of cloth in securing Inca state formation(1991:275-302; see also Moore 1958:52, 54, 56, 92).However, little is currently known about the pre-Columbian importance of cloth in lowland Amazonia.Research needs to be done on the role of cloth infacilitating political hierarchy among the pre-Conquest fluvial chiefdoms of Amazonia, such as theTVipi-Guarani speaking Omagua and Cocama. Earlycolonial accounts offer some tantalizing leads. Forexample, writing of his expedition to the Ucayali(1557), Salinas de Loyola described the attire of thelocal inhabitants by saying that, "in the ornament oftheir persons they represent themselves to be lords"(Myers 1974:140; see also Figueroa 1904:150-51). Likethe Maina and Zaparo, the ancient Cocama andOmaguas also made palm-fiber cloth. Men previouslydonned long cotton tunics (cushmas), adorned withpainted or woven colored designs. Women's attire con-sisted of knee-length cotton skirts and on occasion,small capes. As with other Tupian peoples, theCocama and Omagua feather-work were their mostconspicuous body adornments. Ligatures, such aswaistbands, bracelets, armlets and anklets were madeof cordage or braided hair. The items which theCocama exchanged with their neighbors includedpalm-fiber cloth, tunics, and cloaks (Steward andMetraux 1963:694, 697).

I suspect that a comparative analysis of Amazonianexchange of palm-fiber cordage will reveal how it is an"elementary form of cloth wealth" whose value is linkedto the production and circulation of ritual vestments. Thecirculation of palm-bast cordage is widespread. Along the

upper Tiquie river, balls of tough cordage were made andexchanged with other indigenous groupe for curare (Lowie1963:24). Balls of bast cordage were also an importantitem of exchange in the Vaupes-Caqueta area (Goldman1963:779). On Nambiquara ritual exchange of bast (seeLevi-Strauss 1978:303).

4. According to Maroni (1988:163), "cachibanco" is "hilode achua", or Aguaje (Mauritia minor) thread.

5. On exchange in the Upper Amazon, see Santos 1992:5-31; Oberem 1974; Lathrap 1973.

6. On this point, see Kopytoff's (1986) "biographical ap-proach" which advocates viewing commodities as hav-ing "life histories." The commodity state is neverterminal: objects are capable of moving in and out ofthe commodity condition (Kopytoff 1986:64-91; seealsoLevi 1992:20-21).

7. On the structure and history of peonage in Amazonia,see Rumrill and Zutter 1976:7lff; Chevalier1982:198ff; Stocks 1983:87; Taussig 1986; Reeve1988:23-24; Gow 1991;Muratorio 1991. For the Cham-bira-Urituyacu region, see Domville-Fife 1924:201.For a list of early twentieth-century patrones andtraders of the region to west of the Chambira (Pas-taza), see Jauregui 1943:481.

8. Urarina barter economy refers to the swapping ofgoods without reference to money, established rates ofexchange, or formal partnerships. As Hugh-Jonesnotes, barter occurs primarily between individualsliving near one another and who are united by kin ties.Barter is not only a result but also a mark of sociabil-ity. Moreover, the bartered objects are often simulta-neously both commodity and gift (1992:63; see alsoAppadurai 1986:9).

9. The Chambira-Urituyacu watershed falls largelywithin the geo-political boundaries of the Province ofLoreto. To the north it extends to the border withEcuador, while to the south it is bounded by theMaranon river. The Urituyacu river basin extends tothe Province of Alto Amazonas and the Pastaza andNucuray. To the east, the Chambira basin borders theProvince of Maynas and extends to the Capirona river,an affluent of the Tigre (Corrientes). The eastern,western and northern portions of the Chambira-Urituyacu watershed are the least known ethnologi-cally as well as geographically.

10. The idiom of debt-peonage {habilitacion) is used tospeak about marital responsibility. A man may say,"mi mujer ya se queda a mi cuenta" However, theessentialist position that marriage is equivalent to theexchange of women by men who dominate them, isintimately linked to the belief "that gender is consti-tuted before issues of exchange or control are mobi-lized" (Gow 1991:120; see also Collier and Yanagisako1987:7; Strathern 1987; McCallum 1988).

11. Mitayo refers to "bushmeat" (mammal, fish, or bird).The word derives from the Quechua term mitayoqwhich denotes the practice of providing the missionswith forest game (Gow 1991:323).

12. Urarina groups discontented with their patron willflee, either by river or along an intricate network offorest trails (beru, barairu) linking rivers and commu-nities. By way of extensive overland forest trails, onecan move between the region's primary waterways:Urituyacu, Tigrillo, Chambira, and Corrientes Rivers.

13. The emergence of professional traders in the UpperAmazon dates to the last decades of the eighteenthcentury. Merchants began traveling between the

16 MUSEUM ANTHROPOLOGY VOLUME 18 NUMBER 1

Pacific coast and the montana or high-jungle. Fromthe montana, traders made their way down to thelowlands, or selua baja. In the North-western flanksof the Upper Amazon, peddlers were primarilymigrants from Quito and Moyobamba. During thenineteenth century, a hierarchy of traders was estab-lished according to preferential access to local mar-kets and credit. This network included peddlers(recatistas-alcanzadores), boatmen (regatones), localshop-keepers and finally merchants who dealt directlywith national and international business concerns(Scazzochio 1978:40; Cipolletti 1988:534).

14. During the first half of the nineteenth century, theprincipal exports from the Upper Amazon were bees-wax, salted fish, and sarsaparilla. Regional commerceincluded trade in balsa, copal, tortoise fat and palm-fiber goods such as hammocks (San Roman 1975:101).Maw found that the extractive economy of theUrarinas district was devoted to the trade of balsa,white-beeswax, sarsaparilla, tobacco and foodstuffs(such as cassava and plantains). These products even-tually made their way to distant markets in Moyo-bamba and the Brazilian settlement of Tabatinga. Inreturn, local producers were poorly recompensed inthe form of knives, cotton goods and crockery (Maw1829:170).

15. In the horrific networks of exchange which accompa-nied the rubber boom, humans were also commodified.For instance, Simson reports that among the Zaparo,children were abducted and sold to peddlers in ex-change for an axe, a cutlass, some fish-hooks, needlesand thread, or a few yards of coarse, tocuyo fabric(1878:505; see also Clark 1953:49-62; Taussig1986:60-63; Brown and Fernandez 1991:59, 71-2).

16. Fuentes (1908:27) divides rubber-collectors into threeinter-related categories: Caucheros; aviados and rega-tones. The aviados were responsible for traveling toremote forest encampments in order to obtain therubber in exchange for industrial goods. The locallabor boss or 'patron* (also called cauchero) wasdirectly in charge of controlling the labor-power ofindebted peons.

17. The length of ejld fabric varies between four and tenfeet. The width of each section is usually about twoand one-half feet. Most palm-bast cloth I collectedvaried between 10-12 warps per centimeter and fourwefts per centimeter. Fine palm-fiber fabric may haveas many as 22-24 warps and 6-8 wefts per centimeter.As such, the colored warps are accentuated giving thecloth a variegated appearance. To make net-bags, theweaver will use a "loop and twist" variation of looping(often referred to as knotless netting). The first tworows of the bast-bag employ a type of cross-knit loop-ing.

18. Seiler-Baldinger's study of Yagua weaving found thatbetween 43-46 hours of labor is needed to make ahammock. This includes preparing some 1500m ofcordage, requiring thirteen hours of work. The Yaguareport that it takes them five six-hour working daysto fabricate a hammock (1988:287).

19. Men's weaving includes hats {asiyuu) from tamishi(jijchu) and a variety of baskets (afudi, amadi) suchas the palm frond basket (afuai) used for transportinggarden produce (kiraurl or capillejo in Spanish,afuailafuldi or panero in Spanish).

20. On color symbolism in lowland South America, seeMaybury-Lewis 1967:251-2; Turner 1969:70; Reichel-

Dolmatoff 1971:122-3. On the importance of the colorred as a dye, see Schneider 1987:427.

21. To improve the aim of their fishing spears, adolescentboys and young men undergo arm scarification (bijijyuru&ra) using strips of ninahuasca bark wrappedtightly around their forearms. The bark stripe are leftin contact with the skin for about thirty minutes. Asa result, blistering skin wounds appear which areprone to permanent scarification.

22. The myth of the origin of palm-fiber cloth involves awidowed woman whose son-in-law severs her fingerdue to her ignorance of weaving. The bloody stump isrejuvenated when the widow places her mutilatedhand in an Aguaje tree trunk and a worm exits as herfinger. The woman makes bands of cloth by strikingthe Aguaje palm with the weaving sword. A numberof other myths revolve around a widowed weaver'ssexual relations with Ajkaguiho—the water boa—animportant underworld figure in Urarina cosmology.The widow uses her weaving sword to call Ajkaguihoby striking it against the water. In another myth, theweaving sword is transformed into an electric eel, acosmological analogue of the men's ceremonial stave.

23. Echoing Mauss' claim that to trade, "man must firstlay down the spear" (1967:80), Levi-Strauss suggeststhat, "when a meeting between two [Nambikwara]groups is conducted peacefully, it leads to reciprocalexchange of gifts; strife is replaced by barter"(1978:303; see also Riviere 1984:81-82).

24. Men store their inalienable possessions in a ritualchest or "maleta" (Sp. for suitcase) called kameld.Made from shebon palm, this box houses shamanicappurtenances: bird feather diadem (ajleirjlkumaai),jaguar (januladi kajti) and peccary teeth (ubana kajti)necklaces, shell, nut and claw breast-bands; harpy-eagle fan and sacred ceramics used to consume hallu-cinogens. In addition to ejld, women's inalienablewealth includes beads (didid) bracelets (bijilera) andnecklaces.

25. Handicraft production for external markets is com-mon among indigenous societies of lowland SouthAmerica. An important item of regional trade in theUpper Amazon has traditionally been the chambirahammocks from the Napo River. Hammocks have beenexchanged for a number of centuries among indige-nous, ribereho and national networks of exchange. In1870, Orton reported that the Zaparo were makingtheir living by marketing hammocks for twenty-fivecents each (1870:171). The Zaparo received ironknives for the hammocks which were swapped withmore geographically isolated peoples (Steward andMetraux 1963:644; see also Figueroa 1904:151).

Yagua and Tukuna hammock trade with Europeansbegan in the eighteenth century during the Jesuit's pres-ence in the region. Following independence from Spainand the mid- nineteenth-century "internationalization" ofAmazonia, the commerce in hammocks increased. Ham-mocks were sent from the ports of Loreto, Pebas andTabatinga downriver to Manaus and Para and upriver toMoyobamba. In 1851, a standard hammock fetched $1.50(US) at the Peruvian-Brazilian frontier, an elaborate onewaa worth $4.00, and hammocks with feather fringes werebeing sold for as much as $30.00 (Seiler-Baldinger1988:290; Ave-Lallemant I860 1:114; Hemdon 1853:226).The trade in hammocks was dispersed throughout low-land South America. For example, among the Wapisianas,an Arawakan people of Northern Brazil and southern

MULTIPLE REGIMES OF VALUE 17

British Guiana, cotton thread was used in fabricatinghammocks, which at one time were the most importantitem exchanged with "whites" (Farabee 1918:28).

In Central Brazil, plaitwork is marketed among theKaraja, Xavante, Xerente, Timbira and Kayapo. In theNorthern Amazon, the lukuna sell painted bark-cloth, aswell aa hammocks and purses made of tucum. Basketryis marketed by the Yanomami, Waiwai, Wayana-Aparai,Waiapi and the Upper Negro River groups. In the UpperNegro region, there are two indigenous cooperatives whichmarket handicrafts. Increasingly, indigenous goods maketheir way to the tourist market (Ribeiro 1989).

26. Upper Amazonian trade was important among boththe fluvial and inter-fluvial societies. The Cocamaexchanged palm-bast cloth, tunics, and capes. TheOmagua traded painted pottery, ornate calabashes,and cotton cloth with neighboring groups. Both theCocama and the Omagua obtained their blowgunvenom through barter with the Ticuna and the Peba(Metraux 1963:697; Cipolletti 1988:527-40).

27. Diffusion of weaving knowledge and technology inpost-contact Amazonia requires further investigation,particularly the role of groups such as the Jesuits whotaught spinning and weaving to mission "indians"(Golob 1982:235). On this note, Steward and Metrauxsuggest that the Mayoruna may have learned how toweave hammocks and bags of Astrocaryum or of wildcotton from the mission of San Joaquin de Omaguas(1963:553).

28. Locally produced woven goods in the Maynas missionsduring the eighteenth century included the following:Santo de Tbmas in Andoas—palm-bast net bags; LaLimpia Concepcion de Cahuapanas—woven and dyedfabric; Santiago de la Laguna—various woven goods;San Pablo de Napeanos—hammocks; San Joaquin delos Omaguas—painted cloaks; San Joseph dePinches—palm-bast cloth and sleeping mats;Roamainas—palm-bast cloth; San Xavier deUrarines—palm-bast cloth and hammocks; UpperMaranon—woven, painted mantles, sold for four pesoseach, and clothes; and the Napo river—hammocks,valued at one peso each (Golob 1982:304; Magnin1988:481).

29. On the salt-trade in the Upper Amazon, see Raimondi1942:98f.; Orton 1870:196; Tibesar 1950; Steward andMetraux 1963:644, 654; Santos 1992:23-26.

30. For instance, a yard {yard) of palm-bast cloth madeby the Maynas was worth two reales, Roamainas clothwas valued at three reales while palm-bast cloth madeelsewhere was valued at only one-half real (Golob1982:233; Jouanen 1943:395).

31. Lamista Quechua spun cotton thread which waswoven in "white-owned" obrajes in Tarapoto andMoyobamba (Scazzocchio 1978:41) Cloth was alsomade by indigenous weavers in Quito, and eventuallymade its way to the Napo peoples (Chibchan-Quijo)who dyed this coarse cotton fabric {lienzo) brown withachiote for their clothes (Orton 1870:168).

32. In the Upper Amazon, the system of repartos contin-ued throughout the nineteenth century. Repartos in-volved the forced transfer of goods to indigenouspeoples who were then required to return a fixedquantity of their produce within a stipulated timeperiod (see Oberem 1974:356; Orton 1870:195; Mura-torio 1991:72-3).

33. Herndon's report of the sinking of a Lagunas river-boat, filled with salt and cotton cloth, as it passed the

Tigre river is an indication of the importance of clothand salt in the commerce of Amazonia during themid-nineteenth century (1853:195).

34. In common ribereno parlance, the Urarina are re-ferred to derogatorily as Shimaco: a term whose ety-mological derivation appears to come from the wordcimarron, which originally signified escaped ferallivestock, and later designated runaway Indian slaves(Wolf 1982:156). It seems to have been conferred uponthe Urarina with reference to their perceived indo-lence and the fact that they often fled into the forest,originally because they resisted either working in thecolonial encomiendas or living in the Jesuit Missions.This form of resistance, whose history spans morethan four centuries, has structured contemporary re-lations between those who are Urarina and those whoare not. Patrones and river-traders frequently com-plained to me about the Urarina's shifting patterns ofresidence. Seasonal fishing and gathering expedi-tions, a tradition of "big-man," factional politicking,epidemics, and the requirements of labor migrationhave all promoted frequent population resettlementsamong the Urarina.

35. Siskind reports that Sharanahua have sexual rela-tions with traders for goods like cloth and kerosene(1977:179). However, as far as I could determine,exchange of sexual favors for trade goods seems to bea relatively rare occurrence among Urarina women.

36. In Urarina, to sell is nejkurtiaka, and to buy iskuretenecha. In negotiating a barter transaction witha patron or regaton the Urarina will say uJatakanareke kureitdche"—"let's do business" or"hacemos negocio" On this point, see Gow 1991:106.It is within this context that the Urarina speak of theregatones' "trading hooks" (kuritdi rujkue): e.g., gifts,such as alcohol or hard-bread, which are more thanpaid for in subsequent transactions.

37. The Urarina speak of having one "supreme" god:Kuanra or Kane Kuainidia. Before the arrival ofKuanra, the Urarina say there was no food in theirtraditional territory-the Chambira basin. Kuanragave the Urarina: cassava; plantain; corn; peanuts;sugar cane; and forest animals such as tapir andmonkeys. If these game animals are exchanged withAnazairi {mestizos), Kuanra will punish the Urarinaat death by burning their "souls" or shungos (in Pas-taza Quechua this means liver). God reprimandsthose who have committed evil on earth by subjectingthem at death to thunder and lightening in the celes-tial realm {dede) where a bonfire burns their shungos.The Urarina say a shungo is being burned wheneverthere is thunder. After the shungo is burned, the ashesare transformed into another creature (into a personor into an electric eel, according to various inform-ants).

The Mestizos also have their own god (Anazairikuanra) who created possessions for them: swine, bovine,and rice. According to my informants, the Anazairi stoleall the manufactured trade-goods from Kuanra, theUrarina creator god. Those who stole the goods are todaythe regatones or traders. The Urarina explain that this iswhy they suffer—because their ancestors never stole fromthe Mestizo's god. Communication between Kuanra andthe living is possible through hallucinogenic trance anddreaming. If a person sells Urarina bush-meat tomestizos,Kuanra reprimands the miscreant's deed in their dreams{sinltua) or while they are in trance. The Urarina say that

18 MUSEUM ANTHROPOLOGY VOLUME 18 NUMBER 1

forest game was created for Urarina subsistence, not forcommerce.

References

Appadurai, Arjun1986 Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of

Value. In The Social Life of Things: Commodities inCultural Perspective. Arjun Appadurai, ed. Pp. 3-63.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ave-Lallemant, Robert1860 Reise du'rch Nord-Brasilien im Jahre 1859.

Leipzig. 2 vols.Brosegbini, Silvio

1983 Cuatro Siglos de Misiones entre los Shuar Quito:Mundo Shuar.

Brown, Michael, and Eduardo Fernandez1991 War of Shadows: The Struggle for Utopia in the

Peruvian Amazon. Berkeley: University of CaliforniaPress.

Cajas, J., et. al.1987 Bibliografta Etnolinguistica Urarina. Instituto de

Linguistics Aplicada (CILA), Documento de Trabajo (54)Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

Castelnau, Francis De1850-59 Expedition dans les parties centrales de I'Ameri-

que du Sud, de Rio de Janeiro a Lima, et de Lima au Para.Paris: Bertrand. 16 vols.

Castillo, Gabriel1958 Los Shimacos. Peru Indigena 16/17:23-28.1961 La medicina primitiva entre los Shimacos. Peru

Indigena 20/21:83-94.Chevalier, Jacques

1982 Civilization and the Stolen Gift: Capital, Kin, andCult in Eastern Peru. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Chirif, Alberto, and Carlos Mora1977 Atlas de comunidades nativas. Lima: Ministerio

de Guerra (SINAMOS).Cipolletti, Maria Susana

1988 El trafico de curare en la cuenca amazonica (siglosXVIII y XIX). Anthropos 83:527-40.

Clark, Leonard1953 The Rivers Ran East. New York: Funk and

Wagnalls.Collier, Jane, and Sylvia Yanagisako

1987 Introduction. In Gender and Kinship. Jane Collierand Sylvia Yanagisako, eds. Pp. 1-13. Stanford: StanfordUniversity Press.

Dean, Bartholomew1990 The State and the Aguaruna: Frontier Expansion

in the Upper Amazon, 1541-1990. M.A. thesis in the An-thropology of Social Change and Development. HarvardUniversity.

1992 The Poetics of Creation: Urarina Cosmogony andHistorical Consciousness. Paper Presented at 11th AnnualNortheast Regional Meetings on Andean and AmazonianArchaeology and Ethnobistory. Colgate University. Nov.22.

1993 Forbidden Fruit: Infidelity, Affinity, and Bride-service among the Urarina of Peruvian Amazonia. PaperPresented at the ASA IV Decennial Conference, OxfordUniversity. July 28.

Domville-Fife, Charles William1924 Among Wild Tribes Of The Amazons. London:

Seeley, Service & Co. Limited.Espinosa Perez, Lucas

1955 Contribuciones linguisticas y etnogrdficas sobre

alguno8 pueblos indlgenas del Amazonas Peruano. TomoI.. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Inveotigaciones Cientifi-cas. Instituto Bernardino de Sahagun.

Farabee, William Curtis1918 The Central Arawaks. The University Museum

Anthropological Publications vol. 9. Philadelphia: TheUniversity Museum.

1922 Indian Tribes of Eastern Peru. Papers of thePeabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, HarvardUniversity, vol. 10. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum.

Ferrua Carrasco, F., J. Linares Cruz, and O. Rojas Perez1980 La sociedad Urarina. Iquitos: Organismo

Regional de Desarrollo de Loreto.Figueroa, Francisco de

1904 Relacion de las misiones de la Companla de Jesusen el pals de los Maynas. Madrid: Libreria General DeVictoriano Suarez. [also 1986 Iquitos: CETA-IIAP]. Firstedition 1661.

Fuentes, Hildebrando1908 Loreto: Apuntes geogrdficos, historicos, estadtsti-

cos, politicos y sociales. Lima: Imprenta de la Revista. 2vols.

Gibal y Barcele, Nacisco1925 Diario del viaje hice por famosos rios Mar anon

y Ucayali. In Historia de las misiones Franciscanas. B.Izaguirre, ed. Vol. 8, Pp. 106-7. Lima: Talleres Tipograficosde la Penitenciaria. First edition 1790.

Gibson, Charles1966 Spain in America. New York: Harper and Row.

Girard, Rafael1958 Indios selvaticos de la Amazonia Peruana.

Mexico: Libro Mex.Goldman, Irving

1963 Tribes of the Uaupes-Caqueta Region. In Hand-book of South American Indians. Vol. 3, part 4. Pp. 763-98.Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. Firstedition 1948.

Golob, Ann1982 The Upper Amazon in Historical Perspective.

Ph.D. dissertation, City University of New York.Gow, Peter

1991 Of Mixed Blood: Kinship and History in PeruvianAmazonia. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Guss, David1986 Keeping it Oral: A Yekuana Ethnology. American

Ethnologist 13(3):413-29.1990 To Weave and Sing: Art, Symbol and Narrative in

the South American Rain Forest. Berkeley: University ofCalifornia Press. First edition 1989.

Hardenburg, Walter Ernest1913 The Putumayo: The Devil's Paradise. London:

T. Fisher Unwin.Harner, Michael

1972 The Jivaro: People of the Sacred Waterfalls.Garden City, NY: Anchor Press, Doubleday Books.

Herndon, William Lewis1853 Exploration of the Valley of the Amazon, made

under direction of Navy Department. Washington, DC:Robert Armstrong, Public Printer. Vol. 1.

Hugh-Jones, Stephen1988 The Gun and the Bow: Myths of White Men and

Indians. L'Homrne 106/7:138-56.1992 Yesterday's Luxuries, Tomorrow's Necessities:

Business and Barter in Northwest Amazonia. In Barter,Exchange, and Value. Caroline Humphrey and StephenHugh-Jones, eds. Pp. 42-74. Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press.

MULTIPLE REGIMES OF VALUE 19

Izaguirre, Bernardino1926 Hi8toria de las misiones Franciscanasy narracidn

de los progresos de la geografta en el Oriente del Peru.Lima: Talleree Tipograficos de la Penitenciaria. 14 vols.

Jauregui, Atanasio1943 Cueotionario Censal de la Poblacion Salvaje. In

Misiones pasionistas del Oriente Peruano. Pp. 480-81.Lima: Empresa Granca T. Scheuch S.A.

Jouanen, Jose1941-43 Hi8toria de la Compania de Jesus en la Antigua

Provincia de Quito, 1670-1773. Quito: Editorial Ecuatori-ana. 2 vols.

Katz, Fredrich1990 Debt Peonage in Tulancingo. In Circumpacifica.

Band I: Mittel-und Sudamerika. B. Illius and M.Laubehcer, eds. Pp. 239-48. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Kopytoff, Igor1986 The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditiza-

tion as Process. In The Social Life of Things: Commoditiesin Cultural Perspective. Arjun Appadurai, ed. Pp. 69-91.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kramer, Betty-Jo1977 Las implicaciones ecologicas de la agricultura de

los Urarina. Amazonia Peruana. l(2):75-86.1979 Urarina Economy and Society: Tradition and

Change. Ph.D. dissertation, Political Science Department,Columbia University.

Langer, Erick1986 Debt Peonage and Paternalism in Latin America.

Peasant Studies 13(2):121-27.Lathrap, Donald

1973 The Antiquity and Importance of Long-DistanceTrade Relationships in the Moist Tropics of Pre-Columbian South America. World Archaeology 5:170-85.

Levi, Jerome M.1992 Commoditizing the Vessels of Identity: Trans-

national Trade and the Reconstruction of RaramuriEthnicity. Museum Anthropology 16(3):7-24.

Levi-Strauas, Claude1978 Tristes Tropiques. Translated by J. and D. Weight-

man. New York: Atheneum. First edition 1955.Lowie, Robert H.

1963 The Tropical Fores ts : An Introduction. InHandbook of South American Indians. Vol. 3. Pp. 1-56.Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Magnin, Juan1988 Breve descripcion de la Provincia de Quito, en

la America Meridional In Noticias Autenticas delfamoso rio Marahon. J. P. Chaumeil, ed. MonumentaAmazonica (B4). Iquitos: IIAP and CETA. First edition1740.

Maroni, Pablo1988 Noticias autenticas del famoso rio Maranon, y

misidn apostdlica de la Compania de Jesus en los dilatadosbosques de dicho rio. J.P. Chaumeil, ed. Iquitos: IIAP-CETA. First edition 1738.

Martin Rubio, Maria del Carmen1991 Historia de Maynas, un paraiso perdido en el

Amazonas; Descripciones de Francisco Requena. Madrid:Ediciones Atlas.

Marx, Karl1978 Capital, Vol. 1. In The Marx-Engels Reader.

R. Tucker, ed. Pp. 294-438. New York: W.W. Norton. Firstpublished 1867.

Maw, Henry lister1829 Journal of a Passage from the Pacific to the

Atlantic, Crossing the Andes in the Northern Provinces of

Peru, and Descending the River Maranon, or Amazon.London: John Murray.

Mausa, Marcel1967 The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in

Archaic Society. Translated by I. Cunnison. New York:W W Norton. First edition 1925.

Maybury-Lewis, David1967 Akwt-Shavante Society. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

McCallum, Cecilia1988 The Ventriloquist's Dummy? Man 23:560-61.

Metraux, Alfred1963 Tribes of the Middle and Upper Amazon River. In

Handbook of South American Indians. Vol. 3, part 4. Pp.687-712. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.First edition 1948.

Moore, Sally Falk1958 Power and Property in Inca Peru. New York:

Columbia University Press.Muratorio, Blanca

1991 The Life and Times of Grandfather Alonso:Culture and History in the Upper Amazon. New Bruns-wick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Murra, John1991 Cloth and its Function in the Inka State. In Cloth

and Human Experience. Annette Weiner and JaneSchneider, eds. Pp. 275-302. Washington, DC: Smith-sonian Institution Press. First published in 1962.

Myere, Thomas1974 Spanish Contacts and Social Change on the Ucay-

ali River, Peru. Ethnohistory 2l(2):135-57.Oberem, Udo

1974 Trade and Trade Goods in the Ecuadorian Mon-tana. In Native South Americans, Ethnology of the LeastKnown Continent. P. Lyon, ed. Pp. 346-57. Boston: Little,Brown.

Orton, James1870 The Andes and the Amazon. New York: Harper &