Multicriterion issues in energy policymaking

Transcript of Multicriterion issues in energy policymaking

30 European Journal of Operational Research 56 (1992) 30-40

North-Holland

Case Study

Multicriterion issues in energy policymaking

Reuven Karni, Paul Feigin and Avishai Breiner The Samuel Neaman Institute for Aduanced Studies in Science and Technology, Technion, Haifa, Israel

Received June 1988; revised October 1990

Abstract: A unique opportunity has been provided, enabling us to be able to study policy problems actually faced by decisionmakers in the area of energy resources, and to develop a framework to help them to formulate policy alternatives, express preferences and obtain feedback on the outcomes of these preferences. Several MCDM methods were used to examine whether policies and their outcomes were clear-cut, or whether certain risks would be involved when preferring one policy over another. When decisionmakers were asked to express preferences by direct and indirect approaches, different rankings were obtained, probably as a result of their uncertainty about actually being able to achieve desired goals, and their implicit tradeoff between the desirability of the policy alternative and the likelihood that it could be implemented. A picture of this tradeoff provided a realistic basis upon which policy decisions could be made.

Keywords: Multiple criteria, policymaking energy, electricity

I. Introduction

Worldwide dislocations caused by the energy crisis of 1973 and its aftermath have accentuated our awareness of the importance of natural re- sources, the way they are controlled, and by whom. We have been made vulnerable to irregu- larities in supply and price. Because of the way in which energy, minerals, water, soil, and other resources are created, developed, produced, dis- tributed, marketed and utilized, any policy deci- sion tends to bear fruit across an extended pas- sage of time; so that any policy will have both short and long term ramifications.

Many resource-related studies and analyses have been spawned in response to the energy crisis (see reviews by Samornilidis and Mitropou- los, 1982; Samouilidis and Berahas, 1983; also Siskos and Hubert, 1983; Schultz and Stehfest, 1984; Kok and Lootsma, 1985; Kok, 1986). Most of these reflect policy analysts' attitudes to re-

source issues, and prescriptions for solution, rather than problems actually faced by decision- makers and their ability to propose and imple- ment solutions. Kok (1986) specifically empha- sizes the lack of decisionmaker participation in these studies. Schultz and Stehfest (1984) devel- oped an aggregate utility function based on inter- views with regional energy policy decisionmakers. Although several goals were difficult to define and measure, they felt that the exercise "[can] help the decisionmaker identify what he should strive for in the political process. In addition, it may help him to justify his conclusions to others and to rationalize the discussion". Walker (1982) stresses "that, in order to make the analysis rele- vant, useful and implementable, the analyst must interact more closely with the policymaker and his staff and must obtain a much better under- standing of the way policy decisions are actually made .. . there are usually multiple, and often conflicting, objectives in public-sector planning

0377-2217/92/$05.00 © 1992 - Elsevier Science Publishers B.V. All rights reserved

R. Karni et al. / Multicriterion issues in energy policymaking 31

problems" so that an interdisciplinary approach is necessary for formulating integral and compre- hensive strategies.

Initially, a large quantitative energy-economy model was created to study the Israeli energy system (see Breiner and Karni, 1982). However, as Greenberger, et al. (1976) have pointed out, decisionmakers are not usually interested in mod- els, but in the reliability of the policy analyst, who uses the model as one of his tools; and that "models are used to test policy, as opposed to identification of policy problems and the inven- tion of policy options". This was found to defi- nitely be the case regarding Israeli policymakers, and thus a totally different approach was adopted. The research described in this paper is part of a novel qualitati~'e modelling approach to formulat- ing national resource policies, applied to the en- ergy issue. The framework and methodology are described in Aronofsky, et al. (1981) and Avriel, et al. (1984, 1987). They presume that effective policy formulation requires both the close partici- pation of decisionmakers, experts and analysts, and the incorporation of decisionmakers' value judgements and priorities. Involving all these 'stakeholders' in all stages of the research en- sures the widest exposure of the formulation methodology, of decisions to be taken, and of alternatives available to policymakers.

This led to the organization and implementa- tion of the research in a unique and highly effec- tive fashion:

(a) A central research team (policy analysts) directed and coordinated the research, developed the methodology and architecture, and defined the energy system, energy goals, and policy areas in which decisions needed to be taken.

(b) Specialized groups (experts) developed the information base for the various policy areas, suggested various policy alternatives, and esti- mated their likely impacts on energy goals.

(c) Workshops were held every six to eight weeks, each dedicated to a specific policy area. They were attended by officials of the Ministry of Energy, representatives of the energy industry and representatives of other bodies concerned with energy and its impacts (stakeholders).

(d) Special presentations were made before decisionmakers: the Knesset Energy Sub-Commit- tee; officials of the Ministry of Energy in the presence of the Minister; and directors of various Ministries and energy industry corporations.

The aim of this paper is to describe one of these sessions in detail, illustrate how policies were formulated and evaluated, and discuss some methodological issues arising out of interactions with decisionmakers.

2. Quantitative modelling and multicriterion de- cisionmaking

At one of the workshops, a special extended session was carried out in order to understand

Table 1 Energy coal indicators relevant to pricing policy

1. Create a reliable supply of energy 1.1. Contribution of the policy or theme towards expand-

ing the use of noncommercial energy (such as conser- vation, passive energy, household solar energy).

1.2. Contribution of the policy or theme towards increasing potential energy service supplies.

2. Reduce the cost of energy supplied 2.1. Contribution of the policy or theme towards reducing

the unit cost of energy supplied to users. 2.2. Contribution of the policy or theme towards reducing

the intensity of energy use.

3. Allocate energy as efficiently as possible 3.1. Contribution of the policy or theme towards equating

energy prices to the marginal cost of supply in the short term.

3.2. Contribution of the policy or theme towards equating energy prices of energy to the marginal cost of supply in the long term.

3.3. Contribution of the policy or theme towards prevent- ing subsidization of one energy product by another, or one energy consumer by another.

4. Reduce the inflationary effects of energy costs 4.1. Contribution of the policy or theme towards the re-

duction of inflationary effects in the short term. 4.2. Contribution of the policy or theme towards the re-

duction of inflationary effects in the long term.

5. Maintain social equity when setting energy prices 5.1. Contribution of the policy or theme towards reducing

the gap between social strata. 5.2. Contribution of the policy or theme towards the con-

sideration of residents of areas with difficult climates or geography.

6. Contribute to the goals of other polieymaking areas 6.1. Contribution of the policy or theme towards develop-

ing the industrial infrastructure. 6.2. Degree of acceptance of the policy or theme within

the energy system. 6.3. Degree of acceptance of the policy or theme outside

the energy system. 6.4. Contribution of the policy or theme to reducing the

burden on the national budget.

32 R. Karni et al. / Multicriterion issues in energy policymaking

and examine issues raised by utilizing qualitative modelling and MCDM methodologies to formu- late policy, determine preferences and obtain agreement. The policy area chosen was the pric- ing of electricity, as this subject was easier to define than other issues, a large amount of con- troversy existed as to how to handle the problem, and the range of stakeholders (crude oil and coal supply, electricity generation and distribution, in- dustrial and private consumers, Finance and En- ergy Ministries) was quite extensive.

The session was structured as follows: (1) The decisionmaking framework for the pol-

icy area was presented by the relevant expert group. This framework was made up of the fol- lowing components:

(a) Energy goals impacted by the policy area Any policy must be goal oriented. Thus, as a

first step, energy goals were formulated. This was the topic of a previous workshop. Here, the group presented those goals felt relevant to the issue (Table 1).

(b) Indicators for measuring goal achievement Goals are usually expressed in generalized

terms. Sub-goals or indicators were developed to

Table 2 Electricity pricing actions and alternatives

Action No. 1. Cost of electricity for pricing purposes 1.1. Based on total expenses (operational, financing). 1.2. Based on short-term (3-5 years) marginal expenses. 1.3. Based on long-term (over 5 years) marginal expenses.

Action No. 2. Depreciation factor in electricity costs 2.1. According to historical values. 2.2. According to current values.

Action No. 3. Financing factor in electricity costs 3.1. Based on all operational and investment financing costs. 3.2. Based only on operational costs. 3.3. Based on internal rate of return on total investment. 3.4. Determined by government directives.

Action No. 4. Fuel factor in electricity costs 4.1. Based upon actual fuel prices paid. 4.2. Based upon real market value of fuel purchased.

Action No. 5. Relationship between electricity costs and prices 5.1. Prices to cover costs (all consumers). 5.2. Prices less than costs (for selected consumers). 5.3. Prices greater than costs (for selected consumers).

Action No. 6. Basis for setting prices 6.1. Prices set according to industrial sectors. 6.2. Prices set according to demand pattern. 6.3. Prices set according to time of day pricing.

Table 3 Electricity pricing policy themes and actions

Theme No. 1. 'Balancing the accounts' (financial) (FIN) 1.1. De facto expenditures and costs. 2.2. According to current values. 3.1. All costs to be included in financing factor. 4.1. According to economic sectors. 5.1. Prices to cover costs. 6.2. Prices set according to demand pattern.

Theme No. 2. Short term economic (STE) 1.2. Short term marginal costs. 2.2. Real cost to the economy. 3.2. Prices lower than costs. 4.2. According to demand pattern. 5.1. Prices to cover costs. 6.3. Prices set according to time-of-day pricing.

Theme No. 3. Long term economic (LTE) 1.3. Long term marginal costs. 2.2. Real cost to the economy. 3.3. Prices higher than costs. 4.2. According to demand pattern. 5.1. Prices to cover costs. 6.3. Prices set according to time-of-day pricing.

Theme No. 4. Conservationist (CON) 1.2. Short term marginal costs. 2.2. Real cost to the economy. 3.4. Determined by government directives. 4.2. According to demand pattern. 5.3. Prices greather than costs (for selected consumers). 6.3. Prices set according to time-of-day pricing.

Theme No. 5. Current policy (CUR) 1.1. De facto expenditures and costs. 2.1. De facto outlays. 3.1. Prices to cover costs. 4.1. According to economic sectors. 5.2. Prices less than costs (for selected consumers). 6.1. Prices set according to sectors.

help concretize how goals could be evaluated (Table 1).

(c) Policy decisions and possible alternatives Policymaking is operationally defined as pro-

viding a set of decisions, within the purview of the decisionmaker, which serve as guidelines for implementation. The group thus sat with the de- cisionmakers in the specific policy area, and for- mulated the decisions that they were required to make. They then proposed several possible alter- natives for each decision (Table 2).

(d) Overall policies or policy 'themes' The qualitative model of an overall policy is

composed of a set of consistent actions for each decision to be made. Consistency is obtained by

R. Karni et al. / Multicriterion issues in energy policymaking 33

associating a theme with each policy. For exam- ple, if emphasis is to be placed on energy conser- vation, then the relevant supportive decision al- ternatives will make up this policy. From an anal- ysis of policymaking attitudes the group pre- sented several policies that could be adopted (Table 3).

(2) The impacts resulting from the adoption any of the proposed policies form the body of the model, by relating policy decisions to level of goal achievement. They provide a connection between evidence obtained from expertise, experience or quantitative models, and its incorporation into a qualitative framework. A five-point scale ex- presses the level of achievement for each goal indicator: '1' implying little or no goal achieve- ment through '5' implying significant goal achievement (Table 4). The impact scores were worked up by the group, and presented to the workshop forum.

This completed the presentation of the policy- making environment. The next stage was to ob- tain opinions and value judgements from the par- ticipants, in order to clarify their preferences regarding the various policy alternatives.

(3) Preferences can be obtained in two ways: solution-directed, by directly indicating the de- gree of preference for each alternative; or goal- directed, by indicating the relative importance of the various goals to be achieved, from which the aggregate impact of each alternative can be eval- uated:

(a) The forum was asked to rank the policy themes directly (Table 6; a priori rankings).

(b) The workshop participants were asked to indicate goal importance in two ways: (i) by allo- cating weights directly; and (ii) by allocating weights indirectly by means of the analytical hier- archy process (AHP) technique (Saaty, 1980; 1982) (Table 5). In order to facilitate computations, the

Table 4 Electricity pricing theme scores

Indicator Weight FIN STE LTE CON C U R

(a) Theme scores, by indicator

1. Reliability 25% 1.1. Non-commercial energy 3% 3 1.2. Potential service 22% 3

2. Energy services cost 32% 2.1. Energy cost 29% 3 2.2. Energy intensity 3% 3

3. Energy allocation 19% 3.1. Short term pricing 13% 3 3.2. Long term pricing 5% 3 3.3. Internal subsidies 1% 5

4. Inflationary effects 9% 4.1. Short term reduction 8% 3 4.2. Long term reduction 1% 3

5. Social equity 8% 5.1. Social gap 6% 3 5.2. Sector discrimination 2% 4

6. External goals 7% 6.1. Infrastructure 4% 3 6.2. Internal acceptance 1% 4 6.3. External acceptance 1% 3 6.4. National budget 1% 3

(b) Aggregate theme scores Aggregate score (direct weights) 3.1 Aggregate score (synthetic) 3.0 Ranking (direct weighting) 4 Ranking (synthetic) 4

4 3 4 2 4 3 4 2

4 4 3 3 4 3 5 2

5 3 3 2 3 4 3 2 5 5 5 3

3 3 2 4 3 4 3 3

3 3 3 4 5 5 5 2

2 4 1 4 3 3 2 2 2 3 1 4 4 3 5 2

3.9 3.5 3.2 2.7 3.8 3.5 3.2 2.7 1 2 3 5 1 2 3 5

34

Table 5 Weighting

R. Karni et al. / Multicriterion issues in energy policymaking

goals relevant to electricity pricing policy

Parti- Direct weights (%) cipant Goal no.

1 2 3 4 5 6

Paired weights (%) Goal no.

1 2 3 4 5 6

r Direct Paired (%) entropy entropy

1 45 25 15 3 10 2 2 25 20 20 15 l0 10 3 35 25 10 10 5 15 4 30 70 0 0 0 0 5 35 45 20 0 0 0 6 24 33 24 9 5 5 7 30 35 35 0 0 0 8 20 30 30 4 1 15 9 30 25 10 15 15 5

10 30 30 40 0 0 0 11 13 41 8 0 17 21 12 20 30 10 30 10 0 13 30 45 5 0 20 0 14 15 24 8 8 15 30 15 10 40 30 5 10 5 16 20 30 15 15 10 10 17 30 30 15 15 5 5 18 20 25 30 10 10 5 19 30 19 31 10 5 5

Average 25 32 19 9 8 7 Rank 2 1 3 4 5 6

49 23 13 8 5 3 45 27 11 5 5 3 43 27 10 10 3 7 16 36 5 3 2 39 28 44 16 3 2 7 25 34 28 6 4 4 22 34 32 4 4 4 14 37 37 3 2 7 42 29 6 8 11 4 20 28 41 7 2 3

9 32 5 5 6 44 13 25 7 48 4 2 27 48 5 5 12 4

8 17 4 4 9 59 11 36 38 3 9 3 19 28 13 4 2 34 28 48 9 4 4 8 15 45 28 4 7 2 44 15 19 3 8 11

25 32 18 7 5 13 2 1 3 5 6 4

1 1.40 1.41 15 1.74 1.36 3 1.61 1.47

33 0.61 1.36 2 1.05 1.39 1 1.57 1.50 2 1.10 1.45 4 1.50 1.38 5 1.65 1.47 3 1.09 1.41

14 1.46 1.41 8 1.51 1.36 2 1.19 1.39

17 1.68 1.29 2 1.49 1.41

17 1.71 1.51 9 1.59 1.39 9 1.64 1.39

14 1.49 1.51

Table 6 Electricity pricing a priori and synthetic rankings

Parti- A priori ranking

cipant FIN STE LTE CON

Synthetic ranking

C U R FIN STE LTE CON

Spearman Kendall

C U R correl, correl.

1 5 3.5 3.5 2 2 4 2 3 5 3 5 1 3 2 4 3 2 5 4 5 4 5 3 1 6 3 5 4 2 7 2 3 5 4 8 3 5 4 2 9 2 4 5 3

10 3 4.5 4.5 1.5 11 2 3.5 3.5 5 12 2 4 5 3 13 2 5 3 4 14 2 3 5 4 15 3 4 5 2 16 5 2.5 4 2.5 17 2 1 5 4 18 3 5 4 2 19 2.5 4 5 2.5

Average 3.1 3.6 4.2 2.9 Rank 3 2 1 4

1 3.2 4.0 3.4 3.9 1 3.2 3.8 3.7 3.6 4 3.1 3.7 3.5 3.4 1 3.0 4.0 3.1 4.4 2 3.1 4.0 3.7 3.4 1 3.1 4.0 3.3 3.8 1 3.0 4.0 3.6 3.5 1 3.1 3.6 3.9 3.1 1 3.1 3.8 3.5 3.7 1.5 3.0 3.8 3.8 3.7 1 3.1 3.6 3.4 3.5 1 3.0 3.6 3.5 3.4 1 3.1 3.8 3.3 3.8 1 3.1 3.4 3.2 3.4 1 3.1 3.9 3.7 3.4 1 3.1 3.7 3.7 3.3 3 3.1 3.8 3.6 3.5 1 3.4 4.0 3.8 3.6 1 3.3 3.9 3.7 3.6

1.3 3.1 3.8 3.6 3.5 5 4 1 2 3

2.3 0.225 0.100 2.6 0.100 0.000 2.6 - 0.800 - 0.600 2.1 0.500 0.400 2.5 0.500 0.400 2.3 0.700 0.600 2.3 0.700 0.600 2.6 0.875 0.700 2.6 0.700 0.600 2.1 0.825 0.600 2.7 0.825 0.700 2.8 0.900 0.800 2.7 0.975 0.900 2.8 0.675 0.500 2.6 0.800 0.600 2.7 0.225 0.100 2.6 - 0.100 0.000 2.7 0.900 0.800 2.4 0.875 0.700

2.5 0.547 0.447 5

R. Karni et al. / Multicriterion issues in ener~,,y policymaking 35

logarithmic least squares approach (Belton, 1986; Fichtner, 1986) for estimating the weights was used. Other well-known approaches such as ELECTRE (Siskos and Hubert, 1983) were not used at this time as forum members were unfamiliar with the concepts underlying these methods.

(4) Using the direct goal weights provided by each participant, and indicator weights and theme scores provided by the experts, synthetic policy theme rankings were computed, based upon goal-weighted aggregate impact scores (Table 6).

3. Issues arising from qualitative/MCDM mod- elling

During the ensuing discussion at the work- shop, and further discussions within the policy analysis team, several methodological issues were raised: (1) How 'true' or reliable are the goal weights assigned by each participant? Are the two ranking methodologies consistent? (2) How definite and reliable are the policy theme rank- ings derived for each participant? Are the two approaches consistent? (3) In the face of exter- nally imposed constraints and restrictions, what is the likelihood that any policy theme can be im- plemented?

4. Case Study: Electricity pricing policy

The Israel Electric Corporation holds a state monopoly on the generation and distribution of electricity in Israel, with prices controlled by the government. Current pricing policy is guided by several principles: total income should cover total expenditures; prices must reflect the cost of elec- tricity production, so that the cost of providing power at all levels and times of demand should be charged to customers in accordance with their actual demand patterns (hence the introduction of time-of-use tariffs for large industrial cus- tomers, and an average tariff for other con- sumers); the cost of investment in this sector is based upon historical values; and government concern over inflation has led to some subsidizing of electricity prices. A group of experts was set up to prepare the framework for policymaking in this area.

On reviewing current policy, the group real- ized that three aspects were involved - the supply side: the real cost of fuel and investments, and the real cost of meeting all demand; the demand side: the consumption patterns of various indus- trial sectors and their importance to the econ- omy; and the balance side: the necessity to cover costs without unduly exacerbating the inflationary spiral.

In order to determine directions that policy should take, six energy goals, from a list provided by the policy analysis team, were considered as being relevant to electricity pricing: (1) reliability of supply; (2) cost of supply; (3) efficiency of allocation; (4) impact on inflation; (5) regard for social equity; and (6) support for other national systems (Table 1). In order to be able to express these goals more realistically, and evaluate the impacts of the various policy alternatives, indica- tors for these goals were developed as detailed in Table 1. These goals and indicators may be com- pared to those put forward by Siskos and Hubert (1983) (environmental risk, energy efficiency, en- ergy cost, balance of payments, availability of resources, security of supply, technological feasi- bility and generation of jobs); and by Schultz and Stehfest (1984) (environmental risk, environmen- tal impact, energy efficiency, energy cost, diver- sity of sources and security of supply).

Considering the nature of current policy, and the goals to be achieved, it was felt that six decisions were required at the national level - how to calculate (1) costs of supplying electricity, (2) depreciation on capital investment, (3) financ- ing costs involved in development and operation, (4) actual costs of fuel consumed, (5) the relation- ship between prices and costs; and (6) whether tariffs should be uniform or discriminatory. On the basis of their experience, the team members discussed possible alternative decisions or policy actions that could be taken, over and above those constituting current policy. These policies and proposed action alternatives are given in Table 2.

The group then considered possible courses of action, and suggested five policy themes:

(1) Setting prices such that total costs are balanced by total income, with costs calculated in conventional financial terms ('financial' - FIN).

(2) Setting prices to reflect short term marginal costs such that efficiency is achieved in the short term (up to 5 years) (STE).

36 R. Karni et a L / Multicriterion issues in energy policymaking

(3) Setting prices to reflect long term marginal costs such that efficiency is achieved in the long term (over 5 years) (LTE).

(4) Setting prices such that consumers will conserve energy (CON).

(5) Setting prices in accordance with current policy (CUR).

These five themes and the related actions are set out in Table 3. The expert group then evalu- ated the impact of each action against each goal indicator, giving each a score between '1' and '5'. The resultant impact matrix is presented in Table 4.

After completing the policymaking back- ground, the analysis team then brought the issue before a forum of nineteen participants. About half were drawn from the Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure, and the rest were experts in the various areas researched. Each participant was requested to rank the five themes a priori (Table 6), and, on the other hand, to express preferences for the goals and indicators by assigning weights to them (Table 5). Aggregate theme scores were computed from allocation of these weights across the relevant indicators (Table 4). Thus two sets of rankings were obtained: an a priori ranking based upon internalized preferences, and a ranking syn- thesized from goal and indicator preferences. These policy theme rankings (and average values) are presented in Table 6.

5. Reliability of the goal weights

The method used to express priorities and preferences, using goal weights, relies on the 'cor- rectness' of these weights. In order to study this, the analysis team requested the participants to provide these weights in two ways: directly and indirectly.

Assuming that each subject (policymaker) has some 'true' set of relative weights, the problem at hand is to extract a set of weights which corre- spond as closely as possible to that 'truth'. We also assume that this 'truth' is temporally con- stant, at least with respect to the time scale of the analysis, although it may differ from individal to individual. Let w and v denote the weighting vectors for a subject determined by the pairwise

comparison method and by the direct method, respectively. We have

0< IIw-vll2~< Ilwrl2+ Ilvll 2, with the upper bound being attained when v and w weight different goals altogether. We may therefore measure the proportion (r) of this max- imal value attained by the squared deviation:

r= IIw-vll2/{llwll2+ Ilv[I 2}

and use it to measure the degree of divergence between the two methods of weighting for each of the subjects. Large values of this statistic (say above 15%) indicate a relatively large difference between the methods and point to the need to analyze the actual priorities of the policymaker more closely.

A second point to be studied is the criticism of methods such as Saaty's in that they tend to produce a more even allocation of weights than that which the individual feels reflects his true priorities (see, for example, Figure 4 in Belton, 1986). This effect may be investigated using the entropy of the vector w, namely:

H ( w ) = - ~ w(i) log(w(/)). i=1

The evenness of weight allocation can be com- pared using H(w) and H(v) for each subject. If H(w) is consistently larger than H(v) then this criticism may be valid.

The r statistic and the two entropies (H(w) and H(v)) have been computed for each partici- pant (Table 5). Looking at the column of r values we see, for example, that participant number 4 has a large (33%) discrepancy between the resul- tant weights from the two methods, as is also clear when looking at the actual weights. If this person were the policymaker we would need to go over his/her pairwise comparisons in order to isolate the source of the contradiction and discuss with him/her how it should be resolved. Like- wise, participants 4, 11, 14 and 16 have indicated a strong preference for goal 13 (external goals) via the pairwise comparison method, although this is not reflected in the weights allocated di- rectly. The resultant discrepancy in weights should also be investigated. We see then how this simple analytic tool can provide a useful diagnostic for the reliability of the weights.

R. Karni et al. / Multicriterion issues in energy policymaking 37

Contrary to the spirit of the earlier criticism of the Saaty method, in the present illustration only in four out of the nineteen cases did pairwise comparisons produce significantly more even weights (larger entropy) than the direct weight allocation.

tion, the policymaker includes latent factors, such as implementability, which are not part of the synthetic evaluation.

7. Implementability

6. Reliability of the theme rankings

Ranking of policy themes results from synthe- sis of the experts' evalulation of the impact of each theme on goals and indicators together with weights that reflect the policymaker's relative pri- orities. The result is an aggregate score for each theme such that the theme with the highest score is the preferred one as far as the individual policymaker is concerned. Two approaches were studied: solution-directed ranking and goal-di- rected ranking. In other words, we wish to com- pare the direct theme ranking (an intuitive per- ception) to that obtained by the synthetic method (built up from expert evaluation and policymaker goal preferences). A measure of rank correlation can be used to quantify the level of agreement between the two approaches, using the Spearman or Kendall rank correlation coefficients (Siegel, 1956). Results are presented in Table 6.

The negative correlation for subject 3 indicates that the two rankings are virtually inversions of each other. If this subject were the policymaker, a closer analysis of the weights and scores would be called for in order to determine the source of the discrepancy. Other low values of the correlation (subjects 2, 4, 5, 16, 17) indicate that the synthetic approach does have an appreciable effect in re- ordering the themes. It thus appears that the subject's a priori ranking does not necessarily correspond to the ordering dictated by his priori- ties as expressed in his goal weights. The average correlation (about 0.5) also indicates that, al- though positively correlated, there is some re- ordering of themes for the synthetic approach vis-?~-vis the a priori ordering.

We may postulate several reasons for this: (a) the expert and the policymaker differ on how well each theme meets each energy goal, as expressed by the impact scores; (b) there is a basic inconsis- tency on the part of the policymaker when implic- itly and explicitly defining the relative importance of the goals; and (c) when making a direct evalua-

The energy system exists alongside other sys- tems, and within a national system. Thus energy policy must be coordinated with these systems before it can be realized. The implementability of

Table 7 Implementability criterion and indicators

"The degree to which externally imposed constraints can be overcome, and required resources obtained, in order to imple- ment the policy"

1. Resources l . l . The level of government budgets required in the

short-term [1] requires significant short-term budgeting; [5] Contributes significantly to income in the short-

term. 1.2. The level of government budgets required in the long-

term. [1] requires significant long-term budgeting; [5] contributes significantly to income in the long-term.

2. Acceptability 2.1. General public acceptance.

[1] Significant opposition. [5] Significant support.

2.2. Political (government) acceptance. [t] Significant opposition. [5] Significant support.

2.3. Internal (energy sector) acceptance. [1] Significant oppositon. [5] Significant support.

3. Change factors 3.1. Commitment and flexibility.

[1] Long-term commitment, no flexibility. [5] Short-term commitment, flexible.

3.2. Incrementability. [1] Radical departure from current policy. [5] No change in current policy.

3.3. Change management (execution). [1] Significant legal and institutional changes re-

quired. [5] No legal or institutional changes required.

4. Viability 4.1. Technological viability

[1] based on untried processes; [5] based on established technologies.

4.2 Economic viability [1] uneconomic in all circumstances; [5] proven viability and competitiveness.

38 R. Karni et al. / Multicriterion issues in energy policymaking

a policy alternative is the degree to which exter- nally imposed constraints and restrictions can be removed, and required resources obtained, in or- der to implement the policy with respect to the energy system. The analysis team recognized that energy-related producing and consuming habits were highly ingrained, and that the political clout of the energy sector was unrelated to its eco- nomic and strategic importance. Further, realistic energy solutions required effective planning and execution measures and 'comprehensive re- sources, which were not easily obtained. From these considerations, an implementability crite- rion was built up in a manner similar to that of the goals, with indicators scored on a 1-5 scale, and weighted by the policymaker in order to obtain an aggregate implementability measure (Table 7).

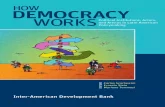

For each of the five alternatives, scores and weights have been given for each implementablity indicator. The resulting weighted scores for goal achievement and implementability are given in Table 8, and plotted in Figure 1. We see that

5 . 0

4 .0

A C 3 .0 W l ][

V I[ 2 . 0 H I[ N T

1 . 0

0 . 0

i

* LTg

* Fill

0 .0 1.0 2.0 3.0 4 .0

~ Z M L ' T T

Figure 1. Achievement versus implementability

5 . 0

CON and CUR are dominated by the other alter- natives, and that LTE indicates a trade-off be- tween higher achievement (STE) and higher im- plementability (FIN). It is our opinion that the policymaker should choose between the three

Table 8 Achievement and implementability scores

Indicator Weight FIN STE LTE CON C U R

(a) Achievement scores Non-trade 0.03 2 4 2 5 1 Reserve capacity 0.24 3 4 3 5 1 Energy cost 0.32 3 4 4 4 2 Demand intensity 0.03 4 4 4 5 1 ST equalization 0.15 2 5 3 2 4 LT equalization 0.05 2 3 5 3 2 Subsidization 0.01 5 5 5 5 3 ST inflation 0.09 3 3 4 2 4 LT inflation 0.01 3 3 4 3 3 Social gap 0.06 3 3 3 3 4 Sectoral gap 0.01 4 5 5 5 2

Weighted score 1.00 2.83 3.96 3.56 3.72 2.32

(b) Implementabi l i ty scores ST budgeting 0.15 3 4 3 4 1 LT budgeting 0.10 3 3 4 4 2 Public acceptance 0.10 4 3 4 1 5 Governmant acceptance 0.15 3 2 3 1 4 Energy acceptance 0.10 4 3 3 2 2 Commitment 0.10 4 2 3 2 4 Incrementability 0.10 5 3 4 2 5 Change management 0.10 4 3 3 3 5 Technical viability 0.05 5 3 3 3 5 Economic viability 0.05 4 3 4 3 3

Weighted score 1.00 3.75 2.90 3.35 2.45 3.45

R. Karni et al. / Multicriterion issues in energy policymaking 39

non-dominated alternatives (STE, LTE, FIN) in accordance with his preferences for achievement or implementability.

8. Discussion

A unique opportunity has been afforded to a research team to be able to study policy problems actually faced by decisionmakers in the area of energy resources, and to develop a framework with which they could formulate policy alterna- tives, express preferences and obtain feedback on the outcomes of these preferences. The explicit foundation upon which the research was based, and cooperation achieved, was that no 'best' pol- icy would be developed or recommended by ex- perts or the research team; but rather that ex- perts would demonstrate various decision alterna- tives that could be taken, and their likely effec- tiveness in achieving the policymaker's goals. Ex- posing proposals to various policmaking bodies ensured that these alternatives were relevant to them.

Conventional MCDM weighting and ranking methods were then applied to see whether a clear-cut policy was preferred; or, if necessary, to signal to the decisionmaker that certain risks would be involved when preferring one policy over another. The method for determining pref- erences explored the relationship between ex- plicit (direct) expressions of policy preference, and those based upon a statement of goal (indi- rect) preferences and expert evaluation of the effectiveness of policy alternatives vis-a-vis these goals. It was found that the two approaches re- sulted in different rankings of policy alternatives. Possible reasons were postulated: disagreement and uncertainty about actually being able to achieve the desired goals, and an implicit tradeoff between the desirability of the policy and the likelihood that it could be implemented.

The tradeoff between achievement and imple- mentability (Figure 1) seems to bear out this observation. The three dominant policies (LTE, STE, FIN) have been ranked highest using the a priori approach; and LTE, which seems to achieve the best tradeoff, has been ranked first. The synthetic method does not produce such consis- tent results. Thus, providing the decisionmaker with a picture of this tradeoff and a measure of

implementability provides a realistic basis upon which policy decisions may be made.

Other issues raised as a result of interaction with policymakers, and further studies such as a comparison of ELEcrRE and the additive weight- ing method described in this article, are de- scribed in Avriel et al. (1987).

References

Aronofsky J., Karni R., and Marcuse W. (1981), "A methol- ogy for the formulation and evaluation of energy goals and policy alternatives for Israel", in: R. Amit, and M. Avriel (eds.). Perspectives in Resource Policy Modeling: Energy and Minerals, Ballinger Publishing Company, Boston, MA.

Avriel, M.A., Arad, N., Karni, R., and Breiner, A. (1984), "A rational decisionmaking approach to resource policymak- ing', in: T. Bayar (ed.), Dynamic Modeling and Control of National Economies, Washington, DC 135-141.

Avriel, M.A., Karni, R., Breiner, A., Feigin, P., and Arad, N. (1987), "'Formulating National Resource Policies", The Samuel Neaman Institute for Advanced Research in Sci- ence and Technology, Haifa, Israel.

Belton, V. (1986), "Comparison of AHP and a simple multi- attribute value function", European Journal of Operational Research 26, 7-21.

Breiner, A., and Karni, R. (1982), "Energy and the Israel economy", European Journal of Operational Research 13, 74-87.

Fichtner, J. (1986), "On deriving priority vectors from matri- ces of pairwise comparisons", Socioeconomic Planning Sci- ences 20 (6), 341-345.

Greenberger, M., Crenson. M.A., and Crissey, B.L. (1976), Models in the Poliey Process, Russell Sage Foundation, New York.

Kok, M. (1986), "The interface with decision makers and some experimental results in interactive multiple objective programming methods", European Journal of Operational Research 26, 96-107.

Kok, M., and Lootsma, F.A. (1985), "Pairwise comparison methods in multiple objective programming, with applica- tions in a long-term energy planning model", European Journal of Operational Research 22, 44-55.

Saaty T.L. (1980), The analytic hierarchy process in planning, priority setting, and resource allocation, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Saaty T.L. (1982), Decision making for leaders, Lifetime Learning Institute, Belmont, CA.

Saaty, T.L., and Vargas, L.G. (1987), "Uncertainty and rank order in the analytic hierarchy process", European Journal of Operational Research 32, 107-117.

Samouilidis, J-E., and Mitropoulos, C.S. (1982), "Energy- economy models: a survey", European Journal of Opera- tional Research 11,222-232.

Samouilidis, J-E., and Berahas, S.A. (1983), "Energy policy modelling in developing and industrializing countries", European Journal of Operational Research 13, 2-11.

Schultz, V., and Stehlfest, H. (1984), "Regional energy supply

40 R. Karni et a L / Multicriterion issues in energy policymaking

optimization with multiple objectives", European Journal of Operational Research 17, 302-312.

Siegel, S. (1956), Non-Parametric Statistics, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Siskos J., and Hubert P. (1983), "Multi-criteria analysis of the

impacts of energy alternatives: A survey and a new com- parative approach", European Journal of Operational Re- search 13, 278-299.

Walker, W.E. (1982), "Models in the policy process: past, present and future", Interfaces 12(5), 91-100.