Migrants’ Skills and Productivity: A European Perspective

Transcript of Migrants’ Skills and Productivity: A European Perspective

R20 NATIONAL INSTITUTE ECONOMIC REVIEW No. 213 JULY 2010

MIGRANTS’ SKILLS AND PRODUCTIVITY: A EUROPEANPERSPECTIVE

Peter Huber,* Michael Landesmann, ** Catherine Robinson *** andRobert Stehrer**

The freedom of movement of persons is one of the core tenets of the European Union. Immigration however is often seenas a cause for concern amongst native workers, as rising labour supply may threaten jobs and create downward pressureon wages. National politicians are increasingly under pressure to guard against it – in times of recession particularly.Despite this, there is evidence that highly-skilled migrant labour has the potential to raise competitiveness significantly andin theory this may feed into productivity. In this paper, we explore first the composition of inward migration to the EU andwithin the EU, concentrating specifically on the role of the highly-skilled and the extent to which migrants are overqualifiedwithin their jobs. We then analyse whether migrant workers affect productivity at the sectoral level. We find under-utilisation of skilled foreign labour and there is little evidence in general to suggest that migrants have raised productivitywhich may in part be attributable to over-qualification. However, we find robust evidence that migrants – particularlyhighly-skilled migrants – play a positive role in productivity developments in industries which are classified as ‘skillintensive’.

Keywords: Migration; skills; productivity; European Union

JEL Classifications: F22; J61; O15; O52

*Austrian Institute of Economic Research (WIFO); **The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw); ***WISERD and School ofBusiness and Economics, Swansea University, e-mail: [email protected]. This work is based on research carried out for the Commissionproject of CR2009. It was financed under the Competitiveness and Innovation Framework Programme (CIP) which aims to encourage thecompetitiveness of European enterprises. The authors would like to thank Stephen Drinkwater for his advice and guidance in the preparation ofthis paper. Any errors remain the responsibility of the authors alone.

1. IntroductionNext to R&D and education policies, the extent andstructure of migration into the European Union is likelyto be one of the major determinants of thecompetitiveness of the European economy in futureyears. In particular, highly-skilled migrants canpotentially have a substantial impact. Hunt andGauthier-Loiselle (2010) draw attention to the fact thatthe foreign-born in the US account for about 26 per centof the US Nobel Prize recipients, 25 per cent of foundersof venture-backed US companies (Anderson and Platzer,2006), 25 per cent of new high-tech companies withmore than one million US dollars of sales and 24 percent of international patent applications (Wadhwa et al.,2007), whilst accounting for only 12 per cent of theresidents. In addition, shifting the structure of migrationto the more highly-skilled may also have a positiveimpact on social security and transfer systems due totheir better integration into the labour markets of thereceiving countries (see Chiswick, 2005).

These potential advantages of high-skilled migration arealso reflected in the policy arena. In the face of ageingEuropean societies and growing needs for highly-skilledlabour, the developed market economies of the EUmember states are facing increased competition forhighly-skilled migrants, to support national innovationsystems, provide entrepreneurial activity and supportwelfare systems, and a number of member states haveimplemented migration policies to attract increasingshares of highly-skilled migrants. Furthermore, theEuropean Commission (as evidenced for instance by therecent green paper on the European Research Area, EC,2007) has also acknowledged that “It is ... essential toestablish a single European labour market for researchers,ensuring effective ‘brain circulation’ within Europe andwith partner countries and attracting young talent andwomen into research careers” (EC, 2007, p. 11).

However, increased migration brings with it new

at COMMERCE LIB E on July 10, 2015ner.sagepub.comDownloaded from

HUBER, LANDESMANN, ROBINSON AND STEHRER MIGRANTS’ SKILLS AND PRODUCTIVITY: A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE R21

demands on economic policy. In particular, there may be aneed to develop appropriate integration policies andinstitutional arrangements to guarantee that highly-skilledmigrants can transfer skills across borders and apply theirknowledge in the host economies. Furthermore, highly-skilled migration – aside from its positive effects – mayalso have negative impacts on natives. In particular, ifhighly-skilled migration is a substitute for native highly-skilled labour and has no additional growth inducingeffects (such as generating innovation, increasedinternational trade or entrepreneurship), this may reducewages for highly-skilled native workers and may alsoreduce incentives for training of the native population. Theincentive to migrate for the highly-skilled may differ fromthat of the less skilled. The highly-skilled are likely to putmore emphasis on career aspects in their decision tomigrate (see for instance Ackers, 2005) and the migrationof the highly-skilled “has additional and complex aspectsrelating to research opportunities, work conditions andaccess to infrastructure” (OECD, 2007, p. 23). Forinstance, for students, the quality of training facilities andmobility grants may be important determinants in theirdecision to become mobile (Tremblay, 2002), while for thehighly-skilled already in the workforce, additional factorssuch as intra-firm arrangements allowing for internationalmobility may be more important for migration decisions(see Hunt, 2004). Despite the substantial academic andpolicy interest in issues associated with highly-skilledmigration, there is to date only a comparatively smallliterature which focuses exclusively on highly-skilledmobility.1

In this paper we discuss the potential positive andnegative effects of highly-skilled migration, before goingon to present evidence for the EU. In section 4, weconsider the role of migration in determiningproductivity growth, separately accounting for thehighly-skilled migrant impact. Section 5 provides adiscussion of the policy implications from our findings.

2. Migration, skills and performanceThere is, as yet, no consensus on how highly-skilledmigration should be measured. International migrantsshould preferably be counted according to the concept offoreign-born rather than by nationality in order to avoiddistortions arising from nation-specific differences innaturalisation of foreign citizens (see for instance EU,2008), but no agreement has yet been reached withrespect to the measurement of the skill content ofinternational migration. A number of authors (e.g. Belotand Hatton, 2008) have suggested that the skill content

of migration is best measured through the human capitalmigrants have acquired in their past (to which we referas education-based measures of migrant skills). Here thehighest completed education of migrants is used tomeasure highly-skilled migration. According to thisdefinition, highly-skilled migrants are usuallyconsidered to be migrants that have completeduniversity education (i.e. ISCED levels 5 and 6).

Given the different determinants of highly-skilledmigration, a large literature has also focused on theimpact of migration on the receiving country, inparticular on the labour market outcomes of natives.Early contributions to this literature (e.g. Freeman andKatz, 1991) start from a baseline labour market model,in which native and foreign labour are perfect substitutesand use the regional or sectoral variation in the share offoreign-born (or its change over time) to identify theeffects of migration on natives. In this simple staticsupply-demand framework, an increase in labour supplyunambiguously reduces wages and employment ofnatives, with the relative size of these effects dependingon the (relative) wage elasticities of labour demand andsupply. This model’s predictions hinge on a number ofassumptions that are often hard to justify empirically.

A first important assumption is that foreign and nativelabour are homogeneous and thus perfect substitutes. If,by contrast, it were assumed that labour isheterogeneous and that natives and foreigners (even withthe same skill levels) were imperfect substitutes or evencomplements, predictions regarding the labour marketeffects of migration could change dramatically,depending on the size of the elasticity of substitutionbetween different kinds of labour. In the context of thelabour market and with regard to more generaleconomic effects of highly-skilled immigration to thehost country, an important question therefore is whetherhighly-skilled migrants are substitutes or complementsto natives. Depending on the extent to which foreignerssubstitute or complement natives, migration will havedifferent effects on wages and employment, respectively.Second, the identification strategy followed in much ofthe early work on the labour market effects of migrationimplicitly assumes that native workers are immobileacross regions, sectors and/or occupations. In reality,however, native workers have a number of possibilitiesto ‘escape’ from increased competition in a certainlabour market segment through mobility. For instance ifa particular region experiences a large inflow ofmigrants, natives may choose to move to another, lessaffected region. Similarly, if a certain sector or

at COMMERCE LIB E on July 10, 2015ner.sagepub.comDownloaded from

R22 NATIONAL INSTITUTE ECONOMIC REVIEW No. 213 JULY 2010

occupation is strongly affected then the movement ofemployment across sectors and occupations may result.Thus a second important question concerning theimpacts of migration on native labour markets is howand whether, aside from wage and employment changes,native workers react to increased migration throughregional, sectoral and occupational mobility.

Finally, a third central assumption of the classicalanalysis is that migrants do not bring capital with them.If one is willing to take a wide view of capital, whichincludes human (and potentially also social andentrepreneurial) capital, this assumption seemsparticularly implausible in the context of highly-skilledmigration. Indeed, given the recent theoretical andempirical literature on endogenous growth, whichhighlights the importance of human capital externalitiesand networks on growth, it is easy to constructtheoretical models in which increased highly-skilledmigration has a positive impact on innovation, trade,FDI, entrepreneurship and potentially also onproductivity and value added growth. Thus a thirdcentral empirical question related to the effects ofhighly-skilled migrants on the receiving economy iswhether these migrants, through increasing the humancapital stock of the receiving economy, contribute toincreased innovation, trade, FDI, entrepreneurship andproductivity and GVA growth. The small effects of(highly-skilled) foreign migrants on the wage andemployment levels of (highly-skilled) natives has led anumber of authors to look at other potential adjustmentmechanisms through which native workers adjust toincreased migration from abroad. While again thisliterature in general does not consider the highly-skilledas a particular group of interest to a great extent, a recentcontribution by Peri and Sparber (2008) looks at theoperation of the labour market for highly-skilled in detail.

Peri and Sparber (2008) consider three possible ways inwhich highly-skilled native workers can potentially escapefrom increased competition caused by foreign workers.They argue that such adjustment could either occurthrough increased regional mobility, increasedunemployment or through increased specialisation ofhighly-skilled natives on tasks (and occupations) thatcannot so easily be fulfilled by migrants (such as tasks thatrequire high linguistic capabilities). Among these potentialmechanisms Peri and Sparber (2008) find this lastmechanism (i.e. increased specialisation of natives oncertain tasks) to be the most important. They report that thecoefficient for the change in highly-skilled foreigners’ shareon the probability of non-employment remains

insignificant (and has an ambiguous sign in differentspecifications). Equally, when regressing the same variableon an indicator for regional mobility it remainsinsignificant. The only variable on which the change in theshare of highly-skilled foreigners is found to have asignificant impact is the tasks performed by highly-skillednatives. Highly-skilled natives faced with increased labourmarket competition from highly-skilled migrants aresignificantly more likely to move to occupations thatrequire more interactive or communication skills. Similarresults are also provided in a recent study on occupationalchoices of highly-skilled migrants and natives by Chiswickand Taengnoi (2007). According to their results, highly-skilled migrants with a lower English language proficiencychoose occupations that require fewer communicationskills, and specialise in particular in computer andengineering skills. The only exceptions to this are highly-skilled migrants with little English language proficiencyworking in services occupations, where they are likely tooffer services for fellow migrants (Chiswick and Taengnoi,2007).

These results seem to indicate that the primary adjustmentby which highly-skilled native workers escape fromincreased competition from foreign workers seems to bethrough occupational mobility. Other means of marketadjustment to the increased labour supply may bemanifested in terms of improved productivity, if the qualityof migrant labour enables employees to improve thequality of their workforce. This can, however, often befrustrated by problems of language and assimilation. Onthe other hand, the nature of the different skills that migrantlabour may have has the potential to enhance technologyadoption and adaptation, either by directly contributing toinnovation (Mattoo et al., 2005), or by facilitatingknowledge spillovers (Moen, 2005).

Quispe-Agnoli and Zavodny (2002) consider the impactof immigrant labour on capital investment and labourproductivity in the US manufacturing sector. They findthat labour productivity is likely to be lower in both highand low-skilled industries as a result of immigration.They attribute this slowdown to problems ofassimilation and argue that this may in fact be a short-run effect, which could disappear as migrants acquirethe necessary language and social skills. Studies thatestimate production functions taking account ofimmigration are few in number. In a comparison ofSpain and the UK, Kangasniemi et al. (2008) use bothgrowth accounting and econometric estimationtechniques to explore the impact of migrants ondomestic performance. Their industry level analysis

at COMMERCE LIB E on July 10, 2015ner.sagepub.comDownloaded from

HUBER, LANDESMANN, ROBINSON AND STEHRER MIGRANTS’ SKILLS AND PRODUCTIVITY: A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE R23

compares two EU countries, where the experience withmigration is quite different. The UK has historicallybeen the recipient of migrant labour, whereas, until themid-1990s, Spain had experienced very little migration.Their findings suggest that the Spanish workforce hasbeen significantly affected by the influx of migrants,whereas the UK has seen little change, and little effect.Taking account of the quality of labour, Kangasniemi etal. (2008) find a small but barely significant positiveimpact of immigrants in the UK, but a significantlynegative impact in Spain. In addition, it is clear from theindustry analysis undertaken in their paper that migrantlabour is significantly industrially concentrated. Thus,skills and industry seem to be specific factors that needto be taken into consideration in any future analyses.

Interesting evidence is also presented in Paserman (2008)who takes a firm-level perspective to consider the impactof an unprecedented increase in the labour force in Israelon firm performance in manufacturing. Following themigration of a substantial number of people from theSoviet Union in the 1990s, not only were absolutenumbers large, in excess of one million migrants, but theskills content of this component of the newly expandedworkforce was exceptionally high. With this in mind,she considers a number of questions, not only whetherproductivity is enhanced by the use of migrant labourbut also how migrants interact with technology andwhether the technology intensity of the industry mattersin determining the productivity impact from migrantlabour. Paserman (2008) employs a two stage approach,where TFP estimates generated by growth accountingare regressed on migration terms. She finds that themigrant share of the workforce is negatively associatedwith productivity in low-tech sectors, but there is someindication of a positive effect in high-tech manufacturingsectors. In addition, analysis indicates that there is anegative relationship between migrant scientists andproductivity in low-tech sectors.

Moreover, the relationship that immigration has withtechnology is a complex one. Lewis (2005) looks at the USmanufacturing sector using firm-level data to explore therelationship between the skills mix of migrant labour andfirms’ choice of technology adoption. In modellingtechnology use, he argues that the Acemoglu (1998) modelof innovation and technology choice is particularlypertinent. Lewis (2005) also argues that the low-skill laboursupply from foreign sources may potentially have anadditional negative effect, over and above the skills mix ofthe indigenous workforce, because of the degree of pathdependence in immigration waves that firms will take into

account in their choice of technology use. The idea is thatmigrants are likely to enter into areas, industries andprofessions where previous waves of migrants havelocated. Lewis’ chief finding is that automation and low-skilled labour are substitutes for each other. This, heargues, is a possible way through which firms can adjust asan alternative mechanism to wages.

Other avenues of business performance that migrant labourmay have affected have been considered. Lach (2007)examines the impact of migrant labour on prices in Israel.Cortes (2008) considers the importance of migrant labourin affecting price levels in the US. Cortes concludes that thelargest effect is in low skill intensive products but estimatesthat the effects are unlikely to be negligible; a 10 per centincrease in immigration is estimated to affect the pricelevels of such products by 1 per cent.

A variety of recent studies also cover the topic of migrationand innovation more generally, which is an importantprerequisite for competitiveness. One strand of thetheoretical literature postulates a positive connectionbetween the ethnic diversity of the labour force andeconomic performance based on the hypothesis that theskills of individuals with diverse ethnic backgrounds arecomplementary in the production process (Fujita andWeber, 2004; Alesina and La Ferrara, 2005). Thishypothesis was supported empirically by Ottaviano andPeri’s (2006) study for US cities. Even after controlling forendogeneity bias, these authors found a positive effect ofethnic diversity on the earnings and productivity of natives.Other studies have explored the connection between ethnicdiversity and innovation and R&D activities. For the US,Florida and Gates (2001) present some evidence of apositive correlation between the concentration of foreign-born individuals and the region’s rank as a high-techgrowth centre, which cannot be interpreted as a causalrelationship. Based on data for German regions, Niebuhr(2006) found a strongly positive effect of ethnic diversity(especially among highly-skilled employees with universitydegrees) on innovation, even when possible endogeneitywas controlled for.

3. Highly-skilled migrant workers in the EUBefore modelling the impact of migrant workers onproductivity in the EU, it is worth spending some timeconsidering the overall picture of EU migration. Thedata we use here are taken from the European UnionLabour Force Survey (EU-LFS) for the years 2006 and2007. These data were the most recent available to us atthe time of writing. The EU-LFS relates to a

at COMMERCE LIB E on July 10, 2015ner.sagepub.comDownloaded from

R24 NATIONAL INSTITUTE ECONOMIC REVIEW No. 213 JULY 2010

representative sample of households in all 27 countriesof the EU. Respondents are interviewed on a number ofdemographic and workplace characteristics (such asoccupation and branch of employment, age, gender andhighest completed education) as well as place of birth.From these questions it is possible to estimate both thetotal number and the structure of the foreign-bornresiding in the EU. We focus primarily on the concept of‘foreign-born’ as a definition of a migrant since thisprovides a complete picture of migration by alsoincluding naturalized citizens and (of particularimportance for international comparisons) avoids thedistortion arising from differences in naturalisationpolicies and autochthonous minorities across countries.

We consider only the population aged fifteen and older,analysed by place of birth and the receiving nation (bycountry of residence). Due to differences in the nationalLabour Force Surveys, no information is supplied on thecountry of birth of residents in Germany or Ireland,making it impossible to identify non-EU-born nationalsin these countries. We thus exclude these two countriesfrom our analysis. Furthermore, we acknowledge that,due to its sampling structure, the EU-LFS (which focuseson permanent residents) is likely to under-representshort-term and seasonal migration.

Another caveat applies to missing data and non-response. In our data, 0.09 per cent of the residents in theEuropean Union did not respond to the question on placeof birth, 1.87 per cent of the foreign-born did not answerthe question on year of arrival, and 4.04 per cent of theresidents did not answer the question on their highesteducation level. While these figures seem sufficientlysmall to allow representative analysis, non-responserates are substantially higher in certain countries. Inparticular in the UK the non-response rate for highestcompleted education is 22 per cent, and in Denmarkalmost 27 per cent of the foreign-born do not answer thequestion on years of residence. Thus data for analysingthe educational structure for the UK may be distorted tosome extent, as well as data with respect to the durationof stay for Denmark.2

We deal with these non-response problems as follows:First, we exclude from our analysis all persons who didnot answer the question on the highest completededucation. Thus our estimates of the EU population andworkforce will not match official statistics on account ofthese exclusions. In addition, we include non-respondents with respect to the question on place of birthas a separate category when analysing our data from the

sending country perspective, but exclude them whenanalysing from a receiving country perspective. Thusthere may be some differences with respect to theaggregate data for EU residents depending on whetherthe receiving country or the sending country perspectiveis analysed. Finally, we exclude foreign-born personswith missing data on the duration of stay in the countryof residence only when considering data on the durationof stay.

A third drawback to our data is that it is taken from asurvey, which is subject to sampling error. We minimisethe problem of high variability of the data for individualyears by using averages across two years (2006 and2007). We divide the total population resident in the EUinto three groups:

1. Native-born – persons that reside in the country inwhich they were born.

2. Other EU-born – persons born in one EU member stateand residing in another.

3. Non-EU-born – persons that were born outside the EU,but reside in an EU country.

Table 1 reports absolute levels and shares of migrants inthe EU, split by country of birth and skill group. It isnoticeable that the share of highly-skilled from outsidethe EU is large since it is double the EU share. Note alsothe importance of Africa and Asia, Central and SouthAmerica and Other Europe. Looking at the split bygender, table 2 reveals that highly-skilled femalemigrants often represent a larger share than for males.This suggests that female migrants are (slightly) morehighly educated, certainly within Europe.

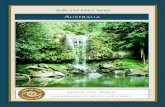

Figure 1 shows the share of migrants in the EU bycountry and by region of origin, averaged over twoperiods, for 2000–2 and 2005–7. We note that in themajority of countries, the share of migrants increases inthe latter half of the 2000s, particularly in Spain. Datafor Ireland were only available for the earlier period,whilst for Italy, data were only available for the laterperiod. France appears to be the only country whichexperiences a fall in shares of migrants between the twoperiods. The decline appears to be a fall in migrantsfrom other Western European countries. The EU12, andthe Rest of the World (medium and poorer incomecountries) are the groups of migrants which appear toshow the fastest growth.

at COMMERCE LIB E on July 10, 2015ner.sagepub.comDownloaded from

HUBER, LANDESMANN, ROBINSON AND STEHRER MIGRANTS’ SKILLS AND PRODUCTIVITY: A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE R25

Table 1. EU-LFS based data on population aged by place of birth

Numbers in thousands Share of total (%)

High Medium Low Total High Medium Low Totalskilled skilled skilled skilled skilled skilled

Native-born 52,759 120,518 122,116 295,393 90.3 92.4 92.0 91.9EU-born (non-natives) 1,844 3,259 2,917 8,020 3.2 2.5 2.2 2.5

From EU 12 to EU 15 434 1,239 628 2,301 0.7 1.0 0.5 0.7From EU 15 to EU 15 1,321 1,781 2,136 5,238 2.3 1.4 1.6 1.6From EU 27 to EU 12 89 239 153 481 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.1

Non-EU-born 3,833 6,604 7,719 18,156 6.6 5.1 5.8 5.6Other Europe 632 1,475 1,340 3,446 1.1 1.1 1.0 1.1Turkey 45 193 456 694 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2North Africa 569 959 2,246 3,774 1.0 0.7 1.7 1.2Other Africa 635 920 961 2,516 1.1 0.7 0.7 0.8South & Central America & Caribbean 758 1,385 1,299 3,442 1.3 1.1 1.0 1.1

East Asia 127 147 168 441 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.1Near and middle East 244 312 234 789 0.4 0.2 0.2 0.2South and southeast Asia 555 939 907 2,401 0.9 0.7 0.7 0.7North America, Australia 269 275 109 653 0.5 0.2 0.1 0.2 and Oceania (incl. other)

No answer 63 78 145 286 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1Total 58,435 130,381 132,752 321,569 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

Source: EU-LFS.Notes: Base population aged 15+; excludes Germany and Ireland, excludes unknown highest completed education; Low-skilled = ISCED 0–2,medium skilled = ISCED 3–4, highly-skilled = ISCED 5–6; EU 12 countries acceding the EU in 2004 and 2007; EU 15 = EU member states before2004; averages 2006–7.

Table 2. Share of EU population (%) aged 15+ by place of birth, gender and highest completed education

Male Female

Low skill Medium skill High skill Low skill Medium skill High skill

Native Born 38.9 43.4 17.7 43.7 38.3 18.0EU-born 35.4 42.0 22.6 37.2 39.5 23.3

From EU 12 to EU 15 26.0 57.2 16.8 28.4 51.2 20.5From EU 15 to EU 15 25.4 46.8 27.8 41.9 39.3 18.7From EU 27 to EU 12 25.4 54.9 19.7 37.2 45.4 17.3

Non-EU-born 41.6 36.8 21.5 43.3 35.9 20.7Other Europe (including CEEC) 39.1 44.2 16.7 38.7 41.6 19.7Turkey 61.0 32.0 7.0 70.9 23.2 5.9North Africa 56.5 26.6 16.9 62.9 24.0 13.0Other Africa 35.1 36.5 28.4 41.3 36.7 22.0South & Central America Caribbean 39.7 40.1 20.2 36.2 40.4 23.4East Asia 38.2 34.6 27.2 38.0 32.1 29.9Near and middle East 29.3 38.9 31.7 30.0 40.2 29.8South and southeast Asia 34.9 39.8 25.3 40.6 38.4 21.0North America, Australia (Oceania) 16.3 44.6 39.1 17.2 39.9 42.9No answer 47.9 30.0 22.1 53.5 24.5 22.0

Source: EU-LFS.Notes: Base population aged 15+; excludes Germany and Ireland, excludes unknown highest completed education; Low-skilled = ISCED 0–2,medium-skilled = ISCED 3–4, highly-skilled = ISCED 5–6; EU 12 countries acceding the EU in 2004 and 2007; EU 15 = EU member states before2004; averages 2006–7.

at COMMERCE LIB E on July 10, 2015ner.sagepub.comDownloaded from

R26 NATIONAL INSTITUTE ECONOMIC REVIEW No. 213 JULY 2010

4. Productivity and migrant labourThe previous section demonstrates that the source ofmigrant labour varies considerably by country, sectorand over time. As discussed above, migrant labour mayhave a positive or a negative effect on productivity,dependent on the attributes of the migrants, institutionalarrangements and native labour market responses. Inthis section we first estimate a full production function,incorporating measures of migrants generally and alsohighly-skilled migrants directly into the specification.We estimate the model over the full economy, sectors Ato P (see figure 2). This one-step estimator is similar tothat used in Kangasniemi et al. (2008). Our secondapproach is to use the TFP growth variable generated inEU KLEMS Productivity Accounts Database using growthaccounting techniques (inclusive of labour and capitalcomposition) and in a second stage to regress TFP growthon a number of migrant terms. In the latter approach, wesplit the estimation over three industry groups – those withhigh, medium and low educational needs.

The primary data source for productivity analysis is the EUKLEMS, March 2008 release. This contains a harmonisedtime series of sectoral information on value added,employment, hours worked and capital services for 1995–2005. Detailed information on the share of migrants ineach sector is available from the EU-LFS for the period1995–2004 and is used to augment the EU KLEMS data. Itwas not possible to use the more recent EU-LFS since thetime series did not match to the EU KLEMS database.3Countries included in the estimation dataset are: Austria,

Belgium, Denmark, Spain, Finland, France, Ireland, Italy,Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden and the UK. EU KLEMSdata for Luxembourg were also available, but data onmigrants for this country were thought to be misleadingand so Luxembourg is excluded from our analysis.

Data from the EU-LFS have been used to identify workerswhose country of origin differs from the nation in whichthey work. Our migrant variable is split into non-nativeworkers from elsewhere within the EU and those workerswho originate from outside the EU (hereafter non-EU). Thisclassification is consistent over the period we areconsidering but, in 2005 and again in 2007, the EU isredefined to take account of its enlarged membership.Migration data are available for a restricted number ofEuropean countries. Data are similar to that used inKangasniemi et al. (2008); however, labour qualityadjustments are not explicitly taken into account becausethe wage data for natives and migrants by sector, skillgroup and country were not of sufficiently good quality forincorporation. Thus, our specification differs somewhatfrom those used in that paper.

There are two ways in which productivity may bemeasured: the growth accounting approach and theproduction function approach. There are advantages andlimitations to both methods, since some of the underlyingassumptions differ – most notably, the functional form isdefined at the outset when estimating the productionfunction, and here we adopt a Cobb Douglas specification.If the functional form chosen is not appropriate, then thismay alter the findings significantly. Harris et al. (2006)

02468

10121416

00-0

2

05-0

7

00-0

2

05-0

7

00-0

2

05-0

7

00-0

2

05-0

7

00-0

2

05-0

7

00-0

2

05-0

7

00-0

2

05-0

7

00-0

2

05-0

7

00-0

2

05-0

7

00-0

2

05-0

7

00-0

2

05-0

7

00-0

2

05-0

7

00-0

2

05-0

7

Western Europe EU12 Europe Rest Rest of World Rich Rest of World Medium + Poor

Figure 1. Migrant shares by origin (%)

Source: EU-LFS, 2000–2 and 2005–7.

AT BE DK ES FI FR GR IE IT NL PT SE UK

at COMMERCE LIB E on July 10, 2015ner.sagepub.comDownloaded from

HUBER, LANDESMANN, ROBINSON AND STEHRER MIGRANTS’ SKILLS AND PRODUCTIVITY: A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE R27

argue that in order to analyse the causes of TFP, aproduction function approach is best suited. This does notimpose the constraints of constant returns to scale or perfectcompetition. Harris et al. (2006) also suggest that cross-country comparisons of TFP may be better served by usinggrowth accounting. In this paper, we adopt a pragmaticapproach and estimate firstly the impact of migrationdirectly through econometric estimation of the productionfunction and then explore whether we detect any impact onTFP growth derived using growth acounting. The latterapproach allows us flexibility in the nature of therelationship between inputs, allowing us to relax theassumptions that the Cobb Douglas specification imposes.

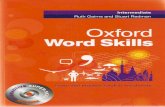

Figure 2 provides further descriptive information on theskill structure of migrants in 2004. Note that sectors forwhich migrant labour is particularly important includethe private household sector (NACE Rev. 1.1 Section P),which is relatively small in terms of overall share of theEuropean economy. Hotels (H), Construction (F) and

Business services (NACE Rev. 1.1 Groups 71 to 74),however, are much more substantial overall and havesignificant shares of foreign workers. In terms of theskills distribution, highly-skilled migrants areparticularly prevalent in the Business Services and inHealth and social work (N) sectors. Low-skilled workersmake up a large proportion of those in Privatehouseholds and in Construction. What is clear fromthese figures is the variation across countries, sectorsand in terms of skills distributions.

We estimate the following production function (with VArepresenting value added) across all countries (excludingLuxembourg) for which data are available.4 We assumea standard Cobb Douglas production function, in whichlabour is measured as total hours worked (Hrs) and thecapital services term is split into ICT (KIT) and non-ICTcapital (KNIT). We also include country (C), time (T)and industry (I) dummy variables in all specificationsand country*time dummy variables to net out business

Source: EU LFS.Notes: mighi=highly-skilled migrants, ISCED 5–6; migmed=ISCED 3–4; miglow=ISCED 0–2. NACE Rev. 1.1 sector definitions: A=Agriculture,hunting and forestry, B=Fishing, C=Mining and quarrying, 15t16=food, drink and tobacco, 17t19=textiles and leather goods, 21t22=Paper andprinting, 23=Coke and refined petroleum, 24=Chemicals and chemical products, 25=Rubber and plastics, 26=Other non-metallic mineralproducts, 27t28=Basic and fabricated metal products, 29=Machinery nec, 30t33=Electrical and optical equipment, 34t35=Transport equipment,36t37=Manufacturing NEC, recycling, E=Electricity, gas and water supply, F=Construction, G=Wholesale and retail trade, H=Hotels andRestaurants, 60t63=Transport and storage, 64=Post and telecommunications, J=Financial intermediation, 70=Real estate, 71t74=Renting ofmachinery and equipment and other business services, L=Public administration, N=Health and social work, O=Other community, social andpersonal services, P=Private households with employed persons. EU total comprises 13 countries, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Spain, Finland,France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden, and the UK.

Figure 2. Migrant share (%) of employment by NACE Rev 1.1 sector and skill group, 2004 (‘EU total’)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

AtB C

15t1

6

17t1

9 20

21-2

2 23 24 25 26

27t2

8 29

30t3

3

34t3

5

36t3

7 D E F G H

60t6

3 64

J

70

71t7

4 L N O P

%miglow %migmed %mighi

at COMMERCE LIB E on July 10, 2015ner.sagepub.comDownloaded from

R28 NATIONAL INSTITUTE ECONOMIC REVIEW No. 213 JULY 2010

Table 3. Value added (levels) production functions including migrant workers, 1995–2004, EU countries, all sectors

Pooled OLS Fixed effects (unweighted) Random effects (unweighted)(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12)

Log (hours) 0.524*** 0.524*** 0.514*** 0.460*** 0.361*** 0.373*** 0.374***0.366*** 0.470*** 0.463*** 0.466*** 0.461***(0.027) (0.027) (0.027) (0.026) (0.026) (0.025) (0.025) (0.026) (0.021) (0.021) (0.021) (0.021)

Log (non–IT –0.039***–0.039***–0.033***–0.112***0.005 0.001 0.001 –0.001 0.013* 0.010 0.010 0.007 capital) (0.012) (0.012) (0.012) (0.013) (0.008) (0.008) (0.008) (0.008) (0.008) (0.008) (0.008) (0.008)Log (IT capital) 0.360*** 0.359*** 0.361*** 0.456*** 0.264*** 0.250*** 0.250***0.257*** 0.360*** 0.356*** 0.358*** 0.363***

(0.020) (0.020) (0.020) (0.021) (0.023) (0.023) (0.023) (0.023) (0.020) (0.020) (0.020) (0.020)High skilled 0.407*** 0.407*** 0.026* 0.025* 0.003 0.037** 0.035** 0.016 migrants’ share (0.057) (0.057) (0.014) (0.014) (0.017) (0.015) (0.015) (0.017)EU migrant share –0.702 –0.906* –1.135** 0.004 0.004 0.002 0.002

(0.512) (0.511) (0.501) (0.025) (0.025) (0.026) (0.026)Non-EU –0.446 –0.559* –0.733** –0.029 –0.029 –0.166 –0.166 migrant share (0.325) (0.324) (0.317) (0.112) (0.112) (0.115) (0.115)Migrant share –0.525** 0.008 –0.001

(0.255) (0.025) (0.026)HS migrant 23.638*** 2.250** 1.985** share*IT capital (1.779) (0.949) (0.976)

R2 0.937 0.937 0.935 0.939 0.422 0.449 0.449 0.450Observations 2,992 2,992 3,108 2,992 3,108 2,992 2,992 2,992 3,108 2,992 2,992 2,992

Source: Own calculations based on EUKLEMS and EU-LFS data.Note: Standard errors in parentheses;***denotes significance at the 1 per cent level, ** 5 per cent and * 10 per cent; Luxembourg excluded; allspecifications include country (c), industry (I) and business cycle (c*y) dummy variables

cycle effects. Our data are weighted by sector shares, toaccount for the fact that some sectors are larger than others.

ln ln ln

ln

VA Hrs KIT

KNIT X C Tcti cti cti

cti cti ti ci

= + ++ + + + +

α β ββ

1 1 2

3 II ect cti+

The production function is augmented by Xcti whichrepresents a vector of migrant indicators which variesover specifications, but can include the share of EUmigrants, the share of non-EU migrants and the share ofhighly-skilled migrants. We also include an interactionterm between the share of highly-skilled migrants andICT capital in some specifications.

In addition to our levels estimation, if, as Paserman(2008) suggests, highly-skilled migrants are likely tobring with them technological knowhow and innovativelabour input, one might expect that the share of migrantlabour will have a greater impact on the rate at whichproductivity increases and therefore we estimate theimpact of migrant labour on the change in value added:

Δ Δ ΔΔ

ln ln ln

ln

VA Hrs KIT

KNIT X Ccti cti cti

cti cti ti

= + ++ + + +

α β ββ

1 1 2

3 TT I eci ct cti+ +

This specification will also reduce any bias that may becaused by a correlation between unobserved

heterogeneity and the error term in the levels equation.First, we estimate a pooled OLS model, followed byrandom effects and fixed effects estimators. Given thatour panel is operating across a number of dimensions(country, sector and time), we set country-industry as thepanel dimension. All estimates include country, time andindustry dummies. Our findings are presented in tables 3and 4 for levels and growth equations, respectively.

Looking at the impact of migrant labour on value addedlevels, the OLS estimates show that the share of highly-skilled migrants has a significant and positive impact onvalue added, which is still evident in the fixed effects andrandom effects estimates, although the coefficients aremuch smaller. Results for specification (1) show that,when the share of highly-skilled migrants is includedwith the overall migrant share, the migrant share isnegative and significant at the 5 per cent level. Inspecifications (2)–(4), the share of migrants is splitbetween those originating from EU and non-EUcountries. Potentially, this could be a significantdistinction to make for a number of reasons – culturaldistance may be thought to be greater and also,institutional arrangements for EU workers are verydifferent for non-EU workers. In general, we see that theeffect is negative in relation to value added, butnoticeably more so for the EU share of migrants.

at COMMERCE LIB E on July 10, 2015ner.sagepub.comDownloaded from

HUBER, LANDESMANN, ROBINSON AND STEHRER MIGRANTS’ SKILLS AND PRODUCTIVITY: A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE R29

However, when we consider the fixed and random effectsestimates, the coefficients are not significantly differentfrom zero, thus we cannot rule out no effect on valueadded from general shares of migrant labour. Inspecification (4), an interactive term is included,whereby highly-skilled migrants are interacted with ITcapital. Here we do see a highly significant and positivecoefficient in the OLS specification. This suggests thathighly-skilled migrants and high-tech capital aresignificantly complementary. This result remains in thepanel estimates (fixed and random effects), although it ismuch weaker.

Adopting the Cobb Douglas specification implies aconstant returns to scale such that βn sum to 1. It can beseen that in both tables 3 and 4 this can be rejected, withcapital and labour alone summing to around 0.85 onaverage in the OLS models and around 0.6 in the panelestimates. In the case of the growth equations presentedin table 4, our first result is that migrant labour has apositive and statistically significant contribution tomake to value added growth (specification (1)). Thisdisappears when different estimation procedures areused (specifications (5) and (8)). Evidence of an impactfor highly-skilled labour is less clear-cut than in thelevels equation, with only one specification (10) yieldinga significantly positive coefficient. There is, however, anindication that the share of EU migrants and non-EUmigrants do contribute to value added growth, since

both coefficients are positive and significant whenestimated using OLS. This effect disappears for the EUmigrants in the fixed and random effects estimators, butremains positive and significant for the non-EU migrantsin the fixed effects specification (column 7).

Overall, our initial results are not particularly clear onwhether migrant labour has a positive or negativeimpact on productivity. This is not surprising, given themixed findings in other similar studies. However, thisapproach does offer something that previous work hasnot. By using EU KLEMS and the EU-LFS, we havetaken a sectoral approach over a period of ten yearsthroughout a wide range of EU countries to explore theproductivity impact of migrant labour. Our findingsindicate that in terms of value added levels, migrantlabour has a mixed impact depending on thespecification used, which is in part mitigated by thepositive impact of the highly-skilled migrant labourforce, which also appears to interact positively with ITcapital. Thus, the quality of the migrants does appear tobe an important consideration. Our findings also suggesta positive impact of migrant labour on value addedgrowth in the EU, particularly from non-EU countries,with weaker findings with respect to higher skillscompared to the levels analysis. One might tentativelyconclude therefore that in the case of productivitygrowth, migrant labour positively contributes,regardless of skills levels.

Table 4. Value added growth production functions including migrant workers, 1995–2004, EU countries, all sectors

Pooled OLS Fixed effects (unweighted) Random effects (unweighted)(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12)

Log (hours) 0.327*** 0.355*** 0.331*** 0.326*** 0.288*** 0.299*** 0.304***0.304*** 0.315*** 0.322*** 0.325*** 0.322***(0.028) (0.027) (0.027) (0.028) (0.037) (0.036) (0.036) (0.036) (0.033) (0.033) (0.033) (0.033)

Log (non–IT 0.134*** 0.133*** 0.131*** 0.000 0.018 0.017 0.020 0.111*** 0.108*** 0.111*** 0.111*** capital) (0.030) (0.030) (0.030) (0.044) (0.042) (0.042) (0.042) (0.035) (0.035) (0.035) (0.035)Log (IT capital) 0.044*** 0.050*** 0.044*** 0.043*** 0.017 0.016 0.016 0.015 0.014 0.011 0.011 0.010

(0.010) (0.010) (0.010) (0.010) (0.011) (0.010) (0.010) (0.010) (0.010) (0.010) (0.010) (0.010)High-skilled 0.131*** 0.008 0.009 0.001 0.011 0.013* –0.000 migrants’ share (0.033) (0.008) (0.008) (0.010) (0.007) (0.007) (0.008)EU migrant share 0.008 0.007 –0.011 –0.011 –0.002 –0.004

(0.008) (0.008) (0.014) (0.014) (0.014) (0.014)Non–EU 0.138** 0.143** 0.137** 0.142** 0.143** 0.059 0.053 migrant share (0.067) (0.066) (0.066) (0.067) (0.067) (0.039) (0.038)Migrant share 0.130*** 0.118*** 0.116***–0.000 0.009

(0.042) (0.041) (0.042) (0.015) (0.013)HS migrant 0.363* 0.817 1.061*** share*IT capital (0.203) (0.564) (0.351)

R2 0.332 0.327 0.330 0.333 0.062 0.076 0.078 0.079Observations 2,732 2,732 2,816 2,732 2,816 2,732 2,732 2,732 2,816 2,732 2,732 2,732

See note to table 3.

at COMMERCE LIB E on July 10, 2015ner.sagepub.comDownloaded from

R30 NATIONAL INSTITUTE ECONOMIC REVIEW No. 213 JULY 2010

Table 5. Impact of migrants on TFP growth: cross-section results for low-educational intensive industries

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12)

Share of migrants 0.076 0.055 0.079 0.063 –0.061 –0.082* –0.021 –0.007(0.059) (0.086) (0.062) (0.096) (0.041) (0.047) (0.052) (0.073)

Highly-skilled migrants/highly skilled work- –0.139***–0.119* –0.130***–0.080 –0.096***–0.085**–0.094**–0.051 force (0.044) (0.062) (0.048) (0.071) (0.030) (0.034) (0.039) (0.054)Highly-skilled migrants/total 0.054* 0.045 0.046 0.025 0.026 0.013 0.026 0.003 0.039 0.036 0.028 0.012 migrants (0.030) (0.037) (0.031) (0.039) (0.030) (0.034) (0.031) (0.034) (0.028) (0.034) (0.028) (0.034)

R2 (0.128) (0.337) (0.247) (0.462) (0.038) (0.309) (0.182) (0.453) (0.113) (0.334) (0.233) (0.459)Observations 99 99 99 99 99 99 99 99 99 99 99 99Country dummies No Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No YesIndustry dummies No No Yes Yes No No Yes Yes No No Yes Yes

See note to table 3.

Productivity effects on sub-groups of industriesWhilst we include sector dummies in our whole economyregressions above to take some account of differences,there may be groups of industries that behave distinctlydifferently in their use of migrant labour. Indeed, section3 here and earlier work by Kangasniemi et al. (2008)points to wide variation across sectors. Thus, weestimate the impact of migrants on productivity directly,using industry-level TFP growth derived in the EUKLEMS database as dependent variable. By taking atwo-step approach (deriving TFP using growthaccounting and then regressing our augmentingvariables on TFP), overall labour composition and thecomposition of capital have already been factored intothe calculation. In this specification, we incorporate ahighly-skilled migrants measure, but also incorporatethe share of highly-skilled migrant workers, as aproportion of total employment: shares of migrants intotal persons employed (shM), the shares of highly-educated migrants in total highly-educated people(shM3) and the share of high-educated migrants in totalmigrants (stM3)5. The estimated equations take thegeneral form:

ΔTFP shM shM

stM D Dci ci ci

ci i c ict

= + ++ + + +

α β ββ ε

1 2

1

3

3

in case of the cross-section regressions and for the (fixedeffects) panel specification:

ΔTFP shM shM

stM D D Dcit cit cit

cit i c t ict

= + ++ + + + +

α β ββ ε

1 2

1

3

3

We include a set of country and/or industry and timedummies (in case of fixed effects panel regression)denoted by Di , Dc , and Dt , respectively; ε denotes theusual error term.

In tables 5–8 we report the results for sub-samples ofindustries where the industries have been ranked by skillintensities and we checked for different effects of themigrant share variables for the lower and upper tier ofindustries, which include both manufacturing andservices industries. For further details, see Landesmann,Stehrer, and Liebensteiner (2010).6

For the low skills intensive industries shown in table 5,when all three migration measures are included, theshare of highly-skilled migrants in the total high-skilledworkforce has a negative and significant impact on TFPgrowth in our initial specification. However, theinclusion of industry dummies weakens the significanceand the addition of country specific dummy variablesthat net out country differences result in the coefficientbecoming insignificant. Thus, even this effect in thecross-sectional specification appears to be driven bycountry differences. Comparing the specifications thatexclude highly-skilled migrants in the highly-skilledworkforce (columns 5–8, table 5) there is a negative andsignificant coefficient on total migrants only whenindustry-specific effects are not controlled for. Finally for

at COMMERCE LIB E on July 10, 2015ner.sagepub.comDownloaded from

HUBER, LANDESMANN, ROBINSON AND STEHRER MIGRANTS’ SKILLS AND PRODUCTIVITY: A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE R31

Table 6. Impact of migrants on TFP growth: cross-section results for high-educational intensive industries

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12)

Share of migrants –0.336 –0.486 –0.137 –0.261 0.185 0.124 0.279** 0.358(0.246) (0.303) (0.275) (0.375) (0.123) (0.191) (0.126) (0.259)

Highly-skilled migrants/highly skilled work- 0.508** 0.691** 0.382* 0.669** 0.257** 0.345** 0.282*** 0.514** force (0.210) (0.272) (0.226) (0.301) (0.102) (0.168) (0.101) (0.201)Highly-skilled migrants/total –0.014 –0.025 0.041 0.049 –0.006 –0.028 0.066 0.094 –0.007 –0.022 0.049 0.059 migrants (0.028) (0.033) (0.042) (0.069) (0.029) (0.034) (0.040) (0.068) (0.028) (0.033) (0.039) (0.067)

R2 (0.091) (0.217) (0.301) (0.424) (0.028) (0.149) (0.275) (0.382) (0.071) (0.190) (0.299) (0.420)Observations 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88Country dummies No Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No YesIndustry dummies No No Yes Yes No No Yes Yes No No Yes Yes

See note to table 3.

Table 7. Impact of migrants on TFP growth: panel (fixed effects) regression results for low-educational intensiveindustries

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12)

Share of migrants 0.063 0.046 0.106 0.097 –0.040 –0.041 0.052 0.047(0.048) (0.062) (0.073) (0.075) (0.035) (0.043) (0.061) (0.062)

Highly-skilled migrants/highly skilled work- –0.099***–0.073* –0.052 –0.047 –0.071***–0.053**–0.020 –0.019 force (0.031) (0.037) (0.039) (0.039) (0.023) (0.026) (0.032) (0.032)Highly-skilled migrants/total 0.054*** 0.044* 0.035 0.030 0.025 0.020 0.017 0.014 0.043** 0.037* 0.021 0.017 migrants (0.021) (0.023) (0.024) (0.024) (0.019) (0.020) (0.020) (0.020) (0.019) (0.021) (0.022) (0.022)

R2 0.028 0.080 0.115 0.132 0.008 0.072 0.111 0.129 0.025 0.079 0.111 0.129Observations 481 481 481 481 481 481 481 481 481 481 481 481Country dummies No Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes YesIndustry dummies No No Yes Yes No No Yes Yes No No Yes YesYear dummies No No No Yes No No No Yes No No No Yes

See note to table 3.

low-skills sectors, we see that when only highly-skilledmigrants are included (firstly as a share of the highly-skilled and also as a share of the total migrantworkforce), we see that the effect on TFP remainsnegative and significant if industry and/or countrydummies are not included. Thus for the low skillintensive industries, our findings are sensitive to theinclusion of industry and country controls.

Turning to the high skill intensive sectors in table 6, it canbe seen (columns 1 to 4) that the share of highly-skilledmigrants as a proportion of all highly-skilled workers is

positive and significant regardless of the inclusion ofcountry and industry effects. Its magnitude appears more orless robust across the various specifications. In columns 5–8 of table 6 this positive effect is split between the generalmeasure of migrant presence in the total workforce and theshare of highly-skilled migrants in the migrant workforce,although the impact of the latter is only significant with theinclusion of industry dummy variables. Finally we notethat excluding the general migrant share term from themodel (columns 9 to 12) tends to reduce the magnitude ofthe significant coefficients on the share of highly-skilledmigrants in all high-skilled labour.

at COMMERCE LIB E on July 10, 2015ner.sagepub.comDownloaded from

R32 NATIONAL INSTITUTE ECONOMIC REVIEW No. 213 JULY 2010

Table 8. Impact of migrants on TFP growth: panel (fixed effects) regression results for high-educational intensiveindustries

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12)

Share of migrants –0.058 –0.106 0.149 0.063 0.171** 0.119 0.274** 0.219*(0.116) (0.133) (0.160) (0.164) (0.069) (0.098) (0.123) (0.127)

Highly-skilled migrants/highly skilled work- 0.218** 0.248** 0.133 0.162 0.182*** 0.195***0.198** 0.189** force (0.089) (0.099) (0.109) (0.109) (0.053) (0.073) (0.084) (0.084)Highly-skilled migrants/total –0.004 –0.018 0.041 0.033 0.006 –0.008 0.056** 0.053**–0.002 –0.015 0.032 0.029 migrants (0.016) (0.017) (0.028) (0.029) (0.015) (0.017) (0.025) (0.025) (0.015) (0.017) (0.027) (0.027)

R2 0.027 0.082 0.189 0.202 0.014 0.068 0.186 0.197 0.027 0.080 0.187 0.201Observations 432 432 432 432 432 432 432 432 432 432 432 432Country dummies No Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes YesIndustry dummies No No Yes Yes No No Yes Yes No No Yes YesYear dummies No No No Yes No No No Yes No No No Yes

See note to table 3.

Exploiting the panel dimension of the data, our resultsshow a more mixed picture in table 7 for the low-skilledsectors. When industry or year effects are excluded(columns 1 and 2), the share of highly-skilled migrantsin high-skilled employment is negative. At the sametime, the share of highly-skilled migrants as aproportion of total migrants is positive but notsignificant in these specifications. There is nodiscernable migrant impact on TFP growth whenindustry, country and time dummies are included for thelow-skilled sectors. In relation to the highly-skilledindustries in the panel results contained in table 8, ourresults are similar to the cross-sectional findings,although the coefficients are somewhat smaller. Incolumns 3 and 4, we find that there is no significantimpact of the share of highly-skilled migration on TFPgrowth. However, this is positive and highly significantin all other specifications. The share of migrants is alsopositive and significant in columns (5), (7) and (8).

Overall, when splitting the economy into industrygroupings that have high or low skill intensities, we findthat highly-skilled migrants (as a proportion of thehighly-skilled workforce) have a positive and significantrole to play in increasing TFP growth. This is aconsistent finding from our economy-wide productionfunction estimations (column 10, tables 3 and 4) andoffers a better understanding of where more precisely theimpacts lie. The results in the panel regressions are alsorobust when the explanatory variables are included witha lag. Hence this part of our analysis points to some firmfindings with regard to the impact of migrants – and

particularly to the share of highly-skilled migrants – ontotal factor productivity developments in industrieswhich require in general a higher share of highly-skilledemployees. These results are in line with those found inPaserman (2008).

5. ConclusionsThe impact of migration on productivity has been anunder-researched area, particularly in view of the increasedmobility of labour in recent years. The findings in thispaper are mixed but are in line with other studies on theproductivity impact of migrant labour (Kangasniemi et al.,2008; Paserman, 2008). Overall we find a significant effectof migrant labour at the industry level across Europe andthis differs for non-EU and EU migrants, with the formerdisplaying some evidence of a positive effect. For EUmigrants, if anything there is a negative impact onproductivity and its growth. However, this largelydisappears when we take into account potentialendogeneity within the production function estimates.Thus, caution should be exercised when drawing firmpolicy recommendations from this exploratory researchacross such a diverse collection of experiences. With this inmind, however, there is some evidence to suggest that themore selective immigration policies that have beenimplemented in relation to non-EU migrants have alsoyielded a positive effect, in contrast with the mixed findingsin relation to EU migrants. There is some evidence thattechnology and the share of highly-skilled migrants have apositive impact on productivity. We find in particular thatthere are robust positive effects of migrant shares

at COMMERCE LIB E on July 10, 2015ner.sagepub.comDownloaded from

HUBER, LANDESMANN, ROBINSON AND STEHRER MIGRANTS’ SKILLS AND PRODUCTIVITY: A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE R33

(particularly in the shares of highly-skilled migrants) onTFP growth in the group of industries which in generalrequire higher levels of educational attainment.

In general, studies on the impact of migration have tendedto focus on migrants as an aggregate and have found littleimpact on wages and employment probabilities for natives.Here we focus specifically on highly-skilled migrants,examining the extent to which migrant workers affectproductivity in the EU. There is some evidence to suggestthat the skills of migrants are important for productivitylevels, but this becomes weaker when we considerproductivity growth. In the case of productivity growth,migrant labour does appear to have a significantcontribution to make, however. Our findings reflect the factthat non-EU migrants are likely to be subject to selection onthe basis of their skills including points-based types ofimmigration systems. The freedom of movement granted toEU citizens means that their entry cannot be restricted byskill group and, as a result, EU migrants include asubstantial proportion working in low-skilled jobs. This islikely to result in a great deal of skills mismatch in thelabour market. Indeed work by Huber et al. (2009) finds a29.6 percentage point higher probability of highly-skilledmigrant workers from the EU12 being overqualifiedcompared with native workers. This is higher than workersfrom other parts of the world. Our analysis also highlightsthe diversity of findings across sectors, with high skillintensive sectors more likely to see a positive effect frommigrants than industries with lower skill requirements.

NOTES1 This applies in particular to research on highly-skilled

migration in the EU countries, with most research to datefocusing on the US.

2 For the UK, this is thought to be largely due to migrants’educational attainment not being coded correctly, rather it isgenerally coded as ‘other’. UK researchers have used years ofeducation to circumvent this problem. However, we are notable to do this because we do not have years of schooling inour data.

3 On-going research and data collection mean that the EU KLEMSproductivity database is regularly updated. For the latest datavisit http://www.euklems.net.

4 A number of outlying observations were excluded, based onextremely high levels of value added.

5 As the shares of migrants in total persons employed (ShM)and the shares of high-educated migrants in total high-educatedpeople (ShM3) correlate to some extent (the coefficient ofcorrelation being about 0.6 for the pooled cross-sectionsample for instance) we also show results when includingonly one of them to circumvent problems withmulticollinearity.

6 Low education intensive sectors=AtB, 15t16, 17t19, 20, 26,27t28, F, 50, H, Q; Medium education intensive sectors=C,21t22, 23, 24, 25, 29, 36t37, E, 51, 52, 60t63, 64, 70, P; Higheducational intensive sectors=30t33, 34t35, J, 71t74, L, M, N,O. See footnote to figure 2 for full definitions of sectors, orLandesmann, Stehrer and Liebensteiner (2010).

REFERENCESAcemoglu, D. (1998), ‘Why do new technologies complement

skills? Directed technical change and wage inequality’, QuarterlyJournal of Economics, 113(4), pp. 1055–89.

Ackers L. (2005), ‘Moving people and knowledge: scientificmobility in the European Union’, International Migration, 43(5),pp. 99–131.

Alesina, A. and La Ferrara, E. (2005), ‘Ethnic diversity and economicperformance’, Journal of Economic Literature 43, pp. 762–800.

Anderson, S. and Platzer, M. (2006), American Made: The Impact ofImmigrant Entrepreneurs and Professionals on US Competitiveness,National Venture Capital Association.

Belot, M. and Hatton, T. (2008), ‘Immigrant selection in theOECD’, CEPR Discussion Paper 6675.

Chiswick, B.R. (2005), ‘Highly-skilled immigration in theinternational arena’, IZA Discussion Paper 1782.

Chiswick, B.R. and Taengnoi, S. (2007), ‘Occupational choice ofhighly-skilled immigrants in the United States’, IZA DiscussionPaper 2969.

Cortes P. (2008), ‘The effect of low-skilled immigration on USprices: evidence from CPI panel data’, Journal of Political Economy,116(3), pp. 381–422.

European Commission (2007), Green Paper: The EuropeanResearch Area: New Perspectives, Brussels, COM(2007)161final, http://ec.europa.eu/research/era/pdf/era_gp_final_en.pdf

—(2008), Employment in Europe 2008, Directorate-General forEmployment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities, http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=113&newsId=415&furtherNews=yes.

Florida, R. and Gates, G. (2001), ‘Technology and tolerance: theimportance of diversity to high technology growth’,Washington, DC, The Brookings Institution.

Fujita, M. and Weber, S. (2004), ‘Strategic immigration policiesand welfare in heterogeneous countries’, Nota di Lavoro 2.04,Milan, Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei.

Freeman, R.B. and Katz, L.F. (1991), ‘Industrial wage andemployment determination in an open economy’, in Abowd,J.M. and Freeman, R.B.(eds), Immigration, Trade and the LabourMarket, NBER Conference Proceedings, Chapter 8, pp. 235–60, available at http://www.nber.org/books/abow91-1.

Harris, R.I.D., O’Mahony, M. and Robinson, C. (2006), ‘Researchon Scottish productivity’, Final Report to the Scottish ExecutiveOffice of the Chief Economic Advisor, November.

Huber, P., M. Landesmann, M., Robinson, C., Stehrer, R. andNovotny, K. (2009), ‘Migration, skills and productivity’, Studycarried out under the Framework Service Contract B2/ENTR/05/091-FC; Background Study to the DG EnterpriseCompetitiveness Report 2009, Vienna 2009.

Hunt, J. (2004), ‘Are migrants more skilled than non-migrants?Repeat, return and same employer migrants’, DIW DiscussionPaper 422.

Hunt, J. and Gauthier-Loiselle, M. (2010), ‘How much doesimmigration boost innovation?’ American Economic Journal:Macroeconomics, 2(2), pp. 31–56.

at COMMERCE LIB E on July 10, 2015ner.sagepub.comDownloaded from

R34 NATIONAL INSTITUTE ECONOMIC REVIEW No. 213 JULY 2010

Kangasniemi, M., Mas, M., Robinson, C. and Serrano, L. (2008),‘The economic impact of migration – productivity analysis forSpain and the UK’, EU KLEMS Working Paper Series, WorkingPaper 30.

Landesmann, M., Stehrer, R. and Liebensteiner, M. (2010), ‘Migrantsand economic performance in the EU15’, FIW ResearchReport, FIW, Vienna, available at http://www.fiw.ac.at/.

Lach, S. (2007), ‘Immigration and prices’, Journal of Political Economy115, pp. 548–87.

Lewis, E. (2005), ‘Immigration, skill mix and the choice oftechnique’, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia WorkingPaper 05–8.

Mattoo, A., Maskus, K.E. and Chellaraj, G. (2005), ‘Thecontribution of skilled immigration and international graduatestudents to U.S. innovation’, The World Bank, Policy ResearchWorking Paper 3588.

Moen, J. (2005), ‘Is mobility of technical personnel a source ofR&D spillovers?’, Journal of Labor Economics, 23(1), pp. 81–114.

Niebuhr, A. (2006), ‘Migration and innovation: does culturaldiversity matter for regional R&D activity?’, IAB DiscussionPaper 14/2006, Nuremberg, Institute for Employment research(IAB)

OECD (2007), SOPEMI Report – International Migration Outlook2007, Paris, OECD.

Ottaviano, G. and Peri, G. (2006), ‘The economic value of culturaldiversity: evidence from US cities’, Journal of Economic Geography6, pp. 9–44.

Paserman, M.D. (2008), ‘Do high-skill immigrants raiseproductivity? Evidence from Israeli manufacturing firms, 1990–1999’, IZA Discussion Paper 3572.

Peri, G. and Sparber, C. (2008), ‘Highly educated immigrants andnative occupational choice’, CREAM Working Paper 13/08.

Quispe-Agnoli, M. and Zavodny, M. (2002), ‘The effect ofimmigration on output mix, capital, and productivity’, FederalReserve Bank of Atlanta Economic Review, First Quarter, pp. 1–11.

Tremblay, K. (2002), ‘Student mobility between and towardsOECD countries: a comparative analysis’, in OECD,International Mobility of the Highly-skilled, Paris, Chapter 2, pp.39–67.

Wadhwa, V., Saxenian, A.L., Rissing, B. and Gereffi, G. (2007),‘America’s new immigrant entrepreneurs’, Duke ScienceTechnology and Innovation Paper 23.

at COMMERCE LIB E on July 10, 2015ner.sagepub.comDownloaded from