Memory and History in Francophone Africa

Transcript of Memory and History in Francophone Africa

91University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

Memory and history in Francophone Africa

Dieunedort Wandji

This article explores the intricate interplay between history and memory against thebackdrop of contemporary historical developments in French-speaking Africancountries, by taking the view that history and memory are both human attempts torecapture the past, resulting in more or less intellectual re-constructions. Throughvarious occurrences across the changing socio-political context in Francophone Africa,it offers an interpretation of how changing social frames of reference shape memory andinfluence historical knowledge, bequeathing a ‘presentist’ perspective on both. Thearticle ultimately demonstrates that the divergent and conflicting ways in which historyand memory either feed off or mutually manipulate each other, are also part and parcelof political processes in Francophone Africa.

The literature pertaining to the relationship between history and memory

generally either considers history as a disciplinary field of objective

intellectual endeavour with “its own exacting methodological disciplines”

and memory as the engagement of a larger public with the past; or views

history and memory as two related ways of exploring and preserving the

past (Cubitt, 2007, pp. 27–38). Whatever the case, scrutinizing the

relationship between memory and history can be hardly carried out outside

the broader context of analysing how human societies relate, or are

expected to relate, present to past. Whether we consider that the reality we

live in today is the linear product of past events or we take the

poststructuralist view that the past stems—figuratively—from the present,

“a reconstruction of the past in the light of the present” as suggested by

Coser in the tradition of Halbwachs (1992, p. 34), we are operating on the

basic structure of the complex conceptual and theoretical interplay

between history and memory.

Much of the debate regarding the (non)existence of a difference

between history and memory has focused mainly around attempts to

ascertain the distinct nature of these two forms of past-related knowledge.

Efforts to assign specific roles respectively to history and memory has

Memory and history in Francophone Africa

92 University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

resulted in fractious debate, with most authors nevertheless agreeing that

the recent “turn to memory” (Cubitt, 2007, p. 4) has been triggered largely

by what Pierre Nora (1989, pp. 7–10) termed “the acceleration of history”.

Rapid development of political events and the emergence of

“multinationalism” that have allowed popular forms of historicizing to

question the prerogatives of mainstream historicity, while “social and

economic patterns evolving at a slower pace and almost immobile

geographical factors” (Higashi, 2001, pp. 218–219) are prompting different

approaches to memorialization. Hence, reflecting upon the nature of

history and memory has uncovered a dense and intricate relationship.

Indeed contemporary African historiography abounds in illustrative

examples of this relationship between history and memory (Landy, 2001, p.

10). Although somewhat “Eurocentric”, especially in its periodization as

rightly noted by Kansteiner (2002, p. 183), Pierre Nora’s concept of

“acceleration of history” finds relative resonance in post-colonial Africa,

where access to independence came with all the ingredients that have

brought the history–memory debate to the fore, such as “problematized”

identity (Kansteiner, 2002, p. 184), creation of counter-history (Landy, 2001,

p. 10) and agency in history (Eze, 2010), just to name a few. For the purpose

of this article, we shall refer to Francophone Africa to assess how the

process of post-colonial appropriation of history provides insights into

various aspects of the history–memory debate.

This article will firstly address the importance of the present context

in both the production of historical knowledge and the shaping ofmemory.

Secondly, we shall focus on the symbiotic, but tense relationship between

memory and history. A final point of discussion will be the inherent

specificities to history and memory that precludes them from achieving

absolute synonymy at theoretical, conceptual and operational levels. All the

countries referred to in this article were either part of France’s African

empire or Belgian colonial possessions. In any case, they do share French as

a common language and the problematic of history and memory is largely

structured around their colonial history and the relationships between these

countries and their former French-speaking colonial masters.

Dieunedort Wandji

93University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

Memory and history: conditions ofproduction andpower relations

The most obvious commonality between history and memory is that both

revolve around the past. Beyond this unmistakable resemblance, reflecting

upon the individual nature of history and memory offers an interesting

parallel. There is first and foremost a clear difference between history “as

lived” and history “as written” or “as told”. Pierre Nora (1989, p. 8) for

instance, clearly distinguishes between “lived history and the intellectual

operation that renders it intelligible”. Apart from articulating the existence

of a physical divide between the present and the past, this theoretical

distinction also raises the question of “how the modern professional

discourse of history bridges the cognitive gap that otherwise separates past

and present” (Cubitt, 2007, p. 28).

Similarly, individual and collective memory, or more precisely in

Halbwachs’s sense, autobiographical and historical memory (Coser, 1992,

pp. 23–24) do grapple with the same defects; we cannot remember in the

sense of “reliving” a past experience even if we were personally involved in

it, anymore than collective, social or popular memory implies the ability for

a group to “fuse with the past”. Halbwachs (1992, pp. 42–53) insists that

neither an individual nor a social group would be able to construct a

discourse on the past or remember it without being “connected with the

thoughts that come to us from the social milieu”.

Hence, both memory and history are intellectual reconstructions of

the past, evidently because at the time of production of either history or

memory, the past is gone. Reconstructing ‘past events’ or ‘past reality’

almost naturally requires an interpretation. Writing on the historical origins

of fighting in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), described by

some as Africa’s First World War because of its 5.4 million deaths and

complex reasons (Shah, 2010), Justin Bisanswa (2010, p. 78) concludes that

“facts in themselves are not conclusive. They are ambiguous and need

interpretation”. It is commonly agreed that, long before Belgian

colonization of territories in the Great Lakes region in Africa, different

peoples known as the Hutu, the Tutsi and the Munyamulenge migrated

around in this geographical area that is now divided into three countries

Memory and history in Francophone Africa

94 University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

known as DRC, Rwanda and Burundi. The three countries are now involved

in this fighting for more or less murky reasons, against the backdrop of the

1994 genocide in Rwanda when over 800,000 mainly Tutsi were killed. The

perpetrators, mostly Hutu, escaped reprisals and fled to neighbouring

Congo in the eastern region of the DRC after Tutsi fighters took over the

country. From eastern DRC, Hutu often launched attacks into their home

country, bringing about a Rwandan invasion. “As a result, Rwanda has

justified its role in the four-year war by saying it wanted to secure its border,

while critics accused it of using the Interahamwe attacks as an excuse to

deploy 20,000 troops to take control of Congolese diamond mines and

other mineral resources” (Shah, 2010). However, today’s audience is less

concerned about the ethnic origins of the victims than they are about the

appended causes of conflicts in Eastern DRC.

Figure 1: “Voyage du Général de Gaulle en AEF-AOF” (General De Gaulle’s trip to AEF-AOF—French-speaking Africa)

Dieunedort Wandji

95University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

Apart from the fact that most literatures today do not trace the

ethnic aspects of this conflict beyond the 1994 Rwandan genocide to

mention previous massacres in 1963 for example (Kapuscinski, 2001, pp.

171–173), the memory of the 1994 genocide carries the imprint of France’s

abstinence to intervene. Suffice it to say that the early 1990s had ushered in

a new era in world politics and France’s controversial role in Africa was

under intense scrutiny. This interpretation bequeaths a presentist

perspective both on memory and history discourses. Without this

perspective, the reconstruction will bear no relevance to its intended

audience. For instance, gazing at a picture of General Charles de Gaulle

amidst a visibly cheering African populace (figure 1) does not reveal much,

of the historic moment trapped in that image.

Even the caption “Voyage du Général de Gaulle en AEF-AOF” (General

De Gaulle’s trip to AEF-AOF) onto the photo is not enough to mirror back

to us this long-gone event. Without an interpretation carried out against

the backdrop of present concerns and factoring in the opinions of today’s

audience, all the ordinary beholder could see in this photo is that which

“the people in the photos .. . could not see: that their clothing and

automobiles were old-fashioned, that their landscape lacked skyscrapers …

their world was black and white” (Rosenstone, 2001, p. 52). This suggests

that even with this interpretation of historical evidence, we can never

“relive” what the people in this picture experienced. The discourse is not

oriented to the past, but to the contemporaneous actors of the times at

which the discourse is produced. This also suggests that although abiding by

the exacting rules of the discipline, the professional historian nonetheless

belongs to a “social milieu” and imposes his/her frames of reference on the

reconstruction of the past; that history and memory produced within

specific social and political contexts correspond to the ideological and

philosophical pursuits as well as the power relations shaping the context

(Said, 1985, pp. 91–103). For example, African historiographies of the

colonial and postcolonial periods in sub-Saharan African countries are often

an explicit attempt to ‘reclaim’ history from colonial humanities and social

sciences. As a result, a quarter of a century after the end of European

colonial rule, Nora (1989, p. 7) observed that, “independence has swept into

Memory and history in Francophone Africa

96 University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

history societies newly awakened from their ethnological slumber”. In fact,

the process of claiming independence, and indeed the granting of official

independence, are reflected in the ways in which memory and history are

reconstructed in the 1950s ,1960s and afterwards.

Earlier in 1910, a renowned British historian, Athol Joyce had

described Africa as:

a continent practically without a history, and possessing norecords from which such a history might be reconstructed …the Negro is essentially the child of the moment; and hismemory, both tribal and individual, is very short.” (Eze, 2010,p. 21)

Until the early twentieth century, the history of sub-Saharan Africa

and Africans was mainly written by European conquerors through the lenses

of the Hegelian paradigm, which normally excluded the African past from

the Judeo–Christian historicity, seen as universal. Constructed from this

angle, which was the predominant framework for professional historians

and academics during colonial occupation, the African past did not exist

because it had no written record and had purportedly failed to inscribe itself

onto historical time (Jewsiewicki & Mudimbe, 1993, pp. 1–5). In the same

context therefore, history and memory tend to espouse these dominant

views. Bargueño (2011) evokes Freud and Proust to reject the view that

memories are more transparent, devoid of ideological or political biases that

riddle historical analysis, but he acknowledges that history too suffers a

terrible reputation. He suggests that “from its origin the discipline has often

masqueraded under a banner of ‘objective truth’ and historians have

supported myths that have once sidelined, if not attacked, the oppressed

and legitimated the oppressor”.

However, during the 1950s and 1960s, as power relations between the

colonizers and the colonized gradually shifted, the same classical historical

criticism was adapted by African historians to create what Marcia Landy

(2001, p. 11) has described as “a counterhistory of colonialism and

imperialism”.

Starting with Cheikh Anta Diop—who perhaps significantly, now

lends his name to Senegal’s University of Dakar, and whose controversial

Dieunedort Wandji

97University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

“Nations Nègres et Cultures” was published in 1954—the Afrocentric

perspective gradually replaced the Eurocentric views in the sub-Saharan

African historiography. To address the lack of written records of African

history, Africanists carried out studies to demonstrate that the oral mode of

conserving information guarantees its transmission and can just be as

reliable to facts as its written equivalent (Jewsiewicki & Mudimbe, 1993, p.

3). Moreover, it was argued that the fact that written records ofAfrican past

did not exist in Greek or Latin for instance, did not imply that they did not

exist at all. As an example, Paul Stoller (1994) exhibits two documents to

support his claim that alongside their oral history, the Songhay

people—whose empire covered today’s Mali and Niger between 1463 and

1591—had a “long textual tradition”. In fact, two historical documents in

Arabic—es-Sadi’s Tarikh es-Soudan and Kati’s Tarikh al Fattach—offer an

“Islamized” version of the Songhay Empire. In line with the political

context of post-colonial appropriation of African history, Francis Bebey

criticized the unhistorical presence of “Nos ancêtres les Gaulois” (Our

ancestors the Gauls) in history schoolbooks for African students in French

colonies (Gross, 2005, pp. 950–953).

With regards to the reconstruction of African memory, Mbye Cham

(2001, p. 262) recalls that:

some African poets and novelists developed Negritude andother cognates rallying cries and ideologies as a framework fordelving into the African past in order to intervene in and alterEurocentric versions ofAfrica.

While this was intended mainly at a European audience and an

educated African elite, other popular forms of historicizing, like historical

films, participated in construction an African collective memory, which

dissented from the version previously propagated by the colonial masters.

For example, in Sembene Ousmane’s film Ceddo which was released in 1976,

he contests, revises and rejects the Western as well as Arabic versions of

Senegalese past (Cham, 2001, pp. 264–265). This fiction is set in seventeenth

century West Africa, as Islam and Christianity made their way into the

continent. Both religions are portrayed in the film as using and abusing all

means to recruit followers, bribing their way into hearts by offering

Memory and history in Francophone Africa

98 University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

firearms, alcohol and other cheap goods. After successfully converting the

royal family, the Iman is faced with the resistance of the ‘Ceddo’ people,

who opposed renouncing their African spirituality for the sake of a

foreigner’s religion. By thus presenting even Islam in Ceddo as only one of

those ‘forces’ that denatured Senegalese authenticity, Sembene Ousmane is

clearly instilling into popular memory a reconstruction of past-related

awareness that bears the hallmark of the socio-political context of counter-

memory against colonial official version of the African past. As

emancipation movements in Africa gathered momentum and gradually

gained the upper hand in the power relations between the colonized and the

colonizers, at least at a moral level, constructed collective memory is held

up as an intellectual and political weapon against ‘colonial history’—as a

reproduction of power relations. At the same time this collective memory is

seen as a new form of producing history for African societies and new

nations. So, history and memory are both reconstructed under the prism of

the dominant ideology.

History andmemory: intersections, symbiosis andtension

Apart from both reflecting dominant ideologies at the time of their

production, history and memories also appears as two parallel ways of

engaging with the past, whose methods and motives diverge, converge and

sometimes confront one another on many points.

Studying an absent past implies constructing a discourse on its relics,

rather than on the past itself. The professional historian’s systematic

engagement with citable evidence in the production of past-related

knowledge means that they cannot avoid using historical sources that are

essentially products of the memory. Cubitts (2007) warns that historical

sources are not just evidential objects that passively await the historian’s

critical scrutiny. He argues that the ways in which these sources are

produced and the reasons why they survive depend on earlier efforts to

maintain elements of a past to present consciousness (Cubitts, 2007, p. 29).

For example, in the case of the Songhay Empire—Niger and

Mali—mentioned above, the documentary sources that exist are clearly not

Dieunedort Wandji

99University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

objective, as it is well known that they convey a “sanitized (Islamized)

version of the Songhay past” (Stoller, 1994, p. 641). Although the

disciplinary rules of history would require the application of critical

methods to interrogate these traces of the past, the historian studying these

documents will have to be drawn into the frames of reference of the

producers of these historical sources. Cubitt (2007, p. 29) therefore rightly

points that “memory operates on numerous levels in the transmission both

of the information that ends up by being encapsulated in historical source

materials and of the ideas that shape the ways these materials are

interpreted”.

In the absence of documentary sources, history has increasingly

relied on oral sources and records. Notwithstanding the absence of written

records, the greater part of sub-Saharan African historiography that argued

in favour of the existence of an African past rely heavily on oral history.

Amadou Hampâté Bâ (1972, pp. 22–26) for instance—an African elder and

renowned intellectual from Mali—defends the “inherited knowledge that is

transmitted from the mouth of one generation to the ear of the next”.

Similarly, historian Tony Chafer (2002, p. 8; p. 159) used interviews of “key

political actors” as a valid historical source to establish objective facts about

the decolonization process in French West Africa. Despite the difference

between orality—history transmitted across generations without

literacy—and oral history—interviews conducted with people who

participated in or observed past events and whose memories and

perceptions of these are transcribed for future generations—both brands

rely on memory and recollection. The professional historian who conducts

interviews hopes that the recollection of participants in, or observers of,

past events will help reconstruct past reality. Granted that the professional

historian does not take oral sources at face-value and/or will seek to

contextualize and cross reference, it is impossible to say that these sources

are devoid of the social or collective memory within which they were

fleshed out. Here is therefore another instance where history refers to

memory to make sense of the past. History is influenced by memory in the

process, as the mnemonic elements from which historical knowledge is

sourced necessarily carry the fingerprints of their creators, or their

Memory and history in Francophone Africa

100 University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

contextual frameworks, which the historian un-consciously cascades down

to his contemporaries. Even if these sources are certainly cross-referenced,

the possibility of total objectivity, absolute truth and exhaustive veracity is

compromised. In this understanding, memory and history make their

respective truths relative.

Conversely, memory also uses history—selectively—to adjust and

transform itself when politically necessary. A case in point is the place in

the Congolese public memory of Patrice Lumumba, the defiant nationalist

leader who became prime minister, the country’s first elected head of state

when the Congo—today’s DRC—achieved political independence in June

1960, just to be overthrown and assassinated seven months later. On 17

January 1961, the Journal du Katanga’s édition spéciale headlined, “Lumumba et

ses complices massacrés par les villageois” (Lumumba and his accomplices

massacrated by villagers). Belgian sociologist Ludo De Witte (2000) uses

evidence found in Belgian official archives to conclude that the Congolese

independence hero’s assassination was masterminded mainly by the US and

Belgium and carried out by local accomplices and Belgian execution squad,

as the UN turned a blind eye to what the author describes as the “the most

important assassination of the 20th century”. Colonel Mobutu Seseko, who

had overthrown prime minister Lumumba in a military coup with the

blessings of western powers, presented Lumumba’s death as the elimination

of a communist threat. Needless to lay emphasis on what such a threat

meant in the context ofCold War in the 1960s.

Figure 2: Last photo taken ofPatrice Lumumba, 1960.

Dieunedort Wandji

101University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

However, five years only after Lumumba’s elimination, on June 30,

1966, Mobutu, who had branded him an “enemy of the nation”, declared

him a “National hero” in a pompous ceremony. While this had actually not

altered the hard historical fact that the popular Congolese prime minister

had been arrested and subsequently assassinated, it seemed to matter to the

powers that be which side of the good–bad dichotomy was prevailing and

how Lumumba was represented in public consciousness. This cold political

cynicism on the part of the Mobutu regime was an attempt to recuperate

the popular legitimacy of Lumumba. Earlier attempts to dismiss him and

belittle his deeds in Congolese history proved counterproductive; his

permanent presence in popular consciousness could have provided a focus

for oppositional memory. Instead the regime selectively recuperated the

memory of Lumumba, seeking to instrumentalize him for the ends of

official national history. This therefore suggests that official history has to

have some basis in a lived reality or it will be meaningless, and therefore,

ineffective. More precisely, the construction of official history cannot be

done without taking into account popular memory.

Similarly, former Central African Republic (CAR) self-named

emperor Jean Bedel Bokassa, sentenced to death after various accusations of

embezzlement, cannibalism and feeding opponents to lions and crocodiles

in his personal zoo, was rehabilitated by presidential decree in 2010 (BBC,

2010), just as CAR current president Francois Bozize prepared for

presidential elections. Incidentally, there had been resurgence of nostalgia

for the Bokassa era amongst Centrafricans a sentiment that undoubtedly

inspired the rehabilitation decree (Wer, Verlay & Kuchaski, 2011). This

further demonstrates the role played by grassroots remembering in the

shaping of official history, which often cannot contradict collective

memory.

A different example of the complex interplay between ‘collective

memory’ and history as discipline can be found in the controversies

surrounding Gorée Island in Senegal. A controversy sparked by an article in

Le Monde (De Roux, 1996) challenging the veracity of the historical role

attributed to the Senegalese island of Gorée in the transatlantic slave trade

is a useful illustration of how memory can also feed on history. The author

Memory and history in Francophone Africa

102 University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

of the article “Le mythe de la Maison des esclaves qui résiste à la réalité” (The

myth of the house-of-slaves that stands the test of reality) (De Roux, 1996)

questioned the largely accepted historic credence bestowed upon the

Senegalese island as the “door of non-return”, the departing point from

which slaves were taken from the coast ofAfrica to the Americas. This case

highlights three striking points. Firstly, Emmanuel de Roux, the journalist

who wrote this controversial article does not have the status of a

professional historian whose statement could have normally justified “la

vigueur et la promptitude des reactions” (the vigour and promptness of

reactions) (Thioub, 2009, p. 15) that was witnessed. Secondly and more

interestingly, Ibrahima Thioub (2009, p. 15) of the Department of History

at the Université Cheik Antar Diop de Dakar (UCAD) adopts a more

balanced position on the issue in his article, nevertheless does not fail to

acknowledge that the Institut Fondamental d’Afrique Noire – Cheik Anta

Diop was “appuyée par l’autorité politique sénégalaise [pour] réaffirmer la validité

actuelle et la valeur symbolique de Gorée” (supported by the Senegalese political

authority [in order] to reassert the actual validity and symbolic value of

Gorée). Thirdly, Ibrahima Thioub (2009, p. 17) contends that:

L’examen de l’historiographie africaine sur ces processus historiquesmet en évidence un contraste. La faiblesse relative du nombre desétudes consacrées à l’esclavage domestique par les historiens africainscontraste fortement avec l’ancienneté du phénomène, sa généralisationà l’échelle du continent

The examination of African historiography on these historicalprocesses highlights a contrast. The relatively low proportionof studies dedicated to domestic slavery by African historiansgreatly contrast with the age and generalization of thephenomenon at the continental scale.

Coming from an African historian, this is a refreshing perspective on

slavery and the question could be asked that why is it only now that African

historians are more objective on the domestic aspect of slave trade in

Africa, by seeking to place European enslavement of Africans within a

broader context and challenge some of the sharp dichotomies at play?

The uproar caused by the Le Monde article is most likely justified only

Dieunedort Wandji

103University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

by the fact that since this contestation of a widely accepted historical fact

was not made in the restricted space of academic circles, Senegalese and by

extension African collective memory—or communicative memory (for

example Kansteiner, 2002)—on slavery was being called into question

directly in the popular realm. So the more politicized the question, the

greater difficulty in untangling history and memory? Paradoxically, in a

socio-political context such as Senegal, where the state does not and cannot

exert absolute control over historical narrative, when this collective memory

is challenged as has been the case, the state calls upon other historians to

defend its position.

The relatively balanced position of many Senegalese historians on

this issue now, rather than earlier in the 1960s and 1950s when research on

African oral history reigned sovereign, demonstrates how history as a

discipline is torn between the quest of absolute truth and the subtle

memory agenda of dominant ideologies. The core historical fact, which is

the slave trade itself, has absolutely not been contested, but controversies

arise on who the participants were and how it took place (Thioub, 2009, p.

23). This leads to the realization that memory does not only use history, but

indeed, history becomes manipulated by memory and “facts of history are

mostly transferrals of actual historic events into cultural memory which

transforms the events of the past into copies of themselves that are used in

order to describe and define the present” (Cubitt, 2007, p. 122). This tense

aspect of the memory–history relationship proves that it would be a mistake

to completely see history and memory as one and the same thing, which

now leads to an examination of some ways in which memory and history are

dissimilar to each other.

History andmemory: irreconcilable differences

Memory’s most salient feature is its relation to the wider public; its

sentimental and social component. Memory ultimately portrays the past in

terms of ‘bad’ and ‘good’; of ‘heroes’ and ‘villains’. History on the contrary,

has pretension to ‘scientific’ status and lays its claim to ‘objectivity’ on

having “a distinctive object of study – the past .. . which is separate from the

minds of those who study it” (Cubitt, 2007, p. 39). As professional and non-

Memory and history in Francophone Africa

104 University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

professional representations of the past, the divide between history and

memory is therefore primarily epistemological. While the former is

considered factual and stable in its methodologies, the latter is viewed as

prone to mental lapses, ideological twists and unconscious turns

(Halbwachs, 1992, p. 182).

In contrast to memory, history as an academic discipline is bound by

its rules, especially the requirement of citable evidence. The building of

historical knowledge sometimes means an over-reliance on physical proof,

which Raphael Samuel (1994, pp. 3–6) even criticizes as a compulsive,

fetishist attachment to archives, turning the academic historical profession

into an insular tribe. Defenders of history as a discipline argue that the

investigative methods of the professional historian are guided by regular and

repeated application of critical approaches in analysing surviving indications

of the past and eliciting what is worth knowing as history. Normally, history

stops short ofmaking value judgements on the object of its study.

The differences between history and memory are not just related to

their precise respective characteristics as forms or approaches to knowledge

of the past, but also to their significance for society. According to

Halbwachs (1992, p. 188), while memory ensures that a symbolic connecting

thread is running between past and present consciousness, history thrives

on the objective break between them, by keeping a written record. Indeed,

it is the divergent ways in which history and memory structure knowledge

about the past that assign them different functions within society. History

cannot replace memory in postmodern Africa for instance, where collective

memory was predominantly group-specific and oral. The breaking down of

traditional tribal social organisation due to increasing urbanisation and

modern migrations leaves a gap that the present written history cannot fill.

Cubitt (2007, p. 43), points that history “seeks to repair the effects of

memory’s breakdown, but can never reproduce the kind of connection to

the past that memory itself embodies”.

History bears a detached view of the social group, while memory is

part and parcel of the group. History ensures that past is vivid and memory,

that the past is alive. History represents the past that could be accessed

through studying and understanding chronology, special landmarks; it also

Dieunedort Wandji

105University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

assumes discontinuity between past and present. Memory, on the other

hand, offers itself as a symbolic continuity of life flowing from the past to

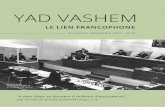

the future. For example, Bogumil Jewsiewicki (2010, pp. 57–59), analysing a

piece of urban culture from the industrial Katanga, the rich mining province

of DRC, a painting (see figure 3) portraying a man holding his chained arms

in the air, explains that “the slave figure breaking his chains is as vital as the

actualization of past experience (slavery, colonization, postcolonial

oppression, etc.) and as the promise of a future”.

Figure 3: I am not a free man, Dessin Lascas, Lubumbashi (Congo), around 1972.

This painting features side by side the collective experience of late-

nineteenth-century raids by slave hunters, forced labour by colonisers who

had come to free from slavery and the citizen’s condition under oppressive

postcolonial rule. History certainly keeps dates and names for these events,

but not this insight on the connection between them, that belongs solely to

the realm of memory. Memory goes as far as playing a role of social

catharsis, through this type of powerful symbolism that uses the past to

Memory and history in Francophone Africa

106 University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

substantiate social identity. Frantz Fanon is often credited with removing

the chains of mentally-ill Arab patients at the hospital he worked at in

Blida, Algeria in the 1950s. This is only a mythologized version of Fanon’s

deeds, but its symbolic nature carries a significant weight for the past,

present and future of Algerians (Cherki, 2006). With regards to the

painting from the former Zaire (DRC) referred to above (figure 3),

Jewsiewicki (2010, p. 59) comments on the memory’s powerful ability to

symbolically achieve continuity in social consciousness, in the following

terms:

A man in underwear, called singlet in Belgian French,represents the ordinary Congolese. Like Lumumba (a politicalChrist who died for the redemption of his people), who is alsoportrayed wearing these same garments [see figure 3], thisfigure is a witness who represents his people.

This description can as well aptly apply to Laurent Gbagbo, the

former Ivorian president who was brutally arrested in his presidential palace

in the country’s capital Abidjan by former rebel soldiers and elements of the

French army following a deadly electoral dispute in 2011 (CBS News, 2011).

Appearing on major news channels around the world on the day he was

arrested wearing the same garments, the ‘singlet’, as described by the

Jewsiewicki above, the character of Laurent Gbagbo bears a striking

resemblance to that of Patrice Lumumba on one of his last photos that

toured the world, and that piece of garments, the singlet seems to

transmute into the symbol of dehumanization for Francophone African

leaders who dare to defy their former colonial masters.

Figure 4: President Laurent Gbagbo arrested, in Belgian Singlet.

Dieunedort Wandji

107University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

Apart from the sheer custumal coincidence, Gbagbo’s political

attitude towards former colonial master, France, the circumstances of his

arrest as well as the actors involved in it—namely French soldiers and the

UN—are in many points mere re-enactments of the Lumumba scenario (De

Witte, 2000). While he is now in jail in the Hague facing amongst others,

charges of crimes against humanity allegedly committed during the post-

electoral dispute, no less than half of the Ivorian electorate who had voted

for his party in the disputed elections (Vampouille & Jamet, 2010) and

hundreds of young people turned human shield who died protecting him,

consider Gbagbo as no other than their “political Christ” who was prepared

to surrender his life so as to free his people from the yoke of neo-

colonialism. This symbolic resemblance between mnemonic

figures—Lumumba-Gabgbo—across generations and locations simply

portrays the fluidity of collective consciousness and the consistent patterns

with which the memorialization process taps into the lived experience of

human societies. This also further underlines memory’s potency of

transcending chronology, space and even discourse.

Conclusion

The diversity of peoples in Francophone Africa and the rich historical

processes developed in today’s French-speaking African countries, from

slavery through coloniZation to present day post-independence era offer an

excellent theatre where history and memory both reveal themselves as

efforts by humans to keep track of their past. It has been observed that

history and memory depend very much on discourse to bridge the gap that

separate the present from the past. This discourse is influenced by the

frames of references of their producers; history and memory are therefore

both reconstructed realities. Context is a key element in the construction of

discourse. History and memory therefore consistently reflect the social and

political concerns of the era and place in which they are produced. As

constructed knowledge, memory and history are also influenced by each

other, and sometimes simply mutually manipulate themselves. The

difference between history and memory can nevertheless be seen in the

nature and social roles of these two approaches to knowing the past. Also,

Memory and history in Francophone Africa

108 University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

their methodologies vary. While history operates on scientific principles,

memory openly disregards the exigency for proof.

The distinction between history and memory remains a highly

debated topic and most authors consistently found arguments for both sides

of the debate. Kansteiner (2002, p. 184) who argues that “most academics

still maintain that in its demand for proof, history stands in sharp

opposition to memory”, also hastens to mitigate, that “perhaps history

should be more appropriately defined as a particular type of cultural

memory”.

References

Bâ, A. H. (1972). Aspects de la civilisation Africaine. Paris: Présence Africaine.

Bargueño, D. (2011, December 2). Contested pasts: Memory's selective, misleading andemotional history. Mail & Guardian Online. Retrieved from http://mg.co.za/article/2011-12-02-contested-pasts-memorys-selective-misleading-and-emotional-history/.

BBC. (2010). Ex-President Jean-Bedel Bokassa rehabilitated by CAR. Retrieved fromhttp://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-11890278.

Bisanswa, J. (2010). Memory, History and Historiography of Congo-Zaire. In M.Diawara, B. Lategan & J. Rusen (Eds.), Historical Memory in Africa (pp. 67–87). NewYork: Berghahn Books.

CBS News. (2011, April 11). Ivory Coast strongman Laurent Gbagbo arrested. Retrieved fromhttp://www.cbsnews.com/2100-202_162-20052728.html.

Cham M. (2001). Reconfiguration of the Past in the Films ofOusmane Sembene. In M.Landy (Ed.), The Historical Film. History andMemory in Media (pp. 261–266). New Jersey:Rutgers University Press.

Cherki, A. (2006). Frantz Fanon: a portrait. New York: Cornell University Press.

Coser, L. A. (1992). On Collective Memory. Chicago: The University ofChicago Press.

Cubitt, G. (2007). History andmemory. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

De Roux, E. (1996, December 27). Le mythe de la Maison des esclaves qui résiste à laréalité. Le Monde.

De Witte, L. (2000). L’assassinat De Lumumba. Paris: Karthala.

Eze, M. O. (2010). The Politics ofHistory in Contemporary Africa. New York: PalgraveMacmillan.

Gross, J. (2005). Revisiting «nos ancêtres les Gaulois»: Scripting and PostscriptingFrancophone Identity. The French Review, 78(5), 948–959.

Halbwachs, M. (1992). The social frameworks ofmemory (L.A. Coser, Trans.). Chicago: TheUniversity ofChicago Press.

Dieunedort Wandji

109University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

Higashi, S. (2001) Walker and Mississipi Burning: Postmodernism versus IllusionistNarrative. In M. Landy (Ed.), The Historical Film: History and Memory in Media (pp.218–231). New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Jewsiewicki, B. & Mudimbe V. Y. (1993). Africans’ Memories and ContemporaryHistory ofAfrica. History andTheory, 32(4), 1–11.

Jewsiewicki, B. (2010). Memory, History and Historiography of Congo-Zaire. In M.Diawara, B. Lategan & J. Rusen (Eds.), Historical Memory in Africa (pp. 53–66). NewYork: Berghahn Books.

Kansteiner, W. (2002). Finding Meaning in Memory: A Methodological Critique ofCollective Memory Studies. History andTheory, 41(2), 179–197.

Kapuscinski, N. (2001). The Shadow ofthe African Sun (K. Glowczewska, Trans.). London:The Penguin Press.

Landy, M. (2001). Introduction. In M. Landy (Ed.), The Historical Film: History andMemory in Media (pp. 218–231). New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Nora, P. (1989). Between Memory andHistory: Les lieux de memoire (M. Roudebush, Trans.).California: The University ofCalfornia.

Rosenstone, R. A. (2001). Looking at the Past in a Postliterate Age. In M. Landy (Ed.),The Historical Film: History and Memory in Media (pp. 218–231). New Jersey: RutgersUniversity Press.

Said, E. W. (1985). Orientalism Reconsidered. CulturalCritique, 1, 89–107.

Samuel, R. (1994). Theatres of Memory Vol 1: Past and Present in Contemporary Culture.London: Verso.

Shah, A. (2010, August 21). The Democratic Republic of Congo. Global Issues. Retrievedfrom http://www.globalissues.org/article/87/the-democratic-republic-of-congo.

Stoller, P. (1994). Embodying Colonial Memories. American Anthropologist, New Series,96(3), 634–648.

Thioub, I. (2009). L’esclavage et ses traites en Afrique, discours mémoriels et savoirsinterdits. Historiens Géographes du Sénégal, 8, 1–27.

Vampouille, T. & Jamet, C. (2010, December 3). Côte d'Ivoire: les résultats de laprésidentielle invalidés. Le Figaro. Retrieved fromhttp://www.lefigaro.fr/international/2010/12/02/01003-20101202ARTFIG00609-alassane-ouattara-remporte-la-presidentielle-en-cote-d-ivoire.php.

Wer, N., Verlay, R. & Kuchaski, S. (Producers), La (Presenter not named). (2011).Complément d’enquête [Television series episode]. Nostagie Bokassa. Paris: France 2.Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n0O9edQrgSI&feature=related.

Figures

Figure 1: “Voyage du Général de Gaulle en AEF-AOF” (General De Gaulle’s trip to AEF-AOF—French-speaking Africa). Retrieved from:

Memory and history in Francophone Africa

110 University ofPortsmouth Postgraduate Review: Issue 3

http://www.metrofrance.com/info/general-de-gaulle-une-vie-en-photos/mjki!wzHQ3mFKkHs/.

Figure 2: Last photo taken of Patrice Lumumba, 1960. Retrieved from:http://sfbayview.com/2012/lumumba-is-an-idea/.

Figure 3: Jewsiewicki, B. (2010). Memory, History and Historiography of Congo-Zaire.In M. Diawara, B. Lategan & J. Rusen (Eds.), Historical Memory in Africa (pp. 53–66).New York: Berghahn Books.

Figure 4: President Laurent Gbagbo arrested. Retrieved fromhttp://www.guardian.co.uk/world/blog/2011/apr/11/ivory-coast-gbagbo-arrested-live-updates.