Medium and Message in Vespasian's Templum Pacis

Transcript of Medium and Message in Vespasian's Templum Pacis

Medium and Message in Vespasian's Templum PacisAuthor(s): Carlos F. NoreñaSource: Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, Vol. 48 (2003), pp. 25-43Published by: University of Michigan Press for the American Academy in RomeStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4238803Accessed: 27/05/2010 17:47

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available athttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unlessyou have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and youmay use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained athttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aarome.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printedpage of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

American Academy in Rome and University of Michigan Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,preserve and extend access to Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome.

http://www.jstor.org

MEDIUM AND MESSAGE IN VESPASIAN'S TEMPLUM PACIS

Carlos F Norefia, Yale University

R ecent large-scale excavations in the area of the imperial fora in Rome have already pro- duced important discoveries and promise to transform our understanding of Rome's

monumental city center.' In the area of the Templum Pacis ("Precinct of Peace") these exca- vations have provided unexpected insights-we now know, for example, that the central square was not paved-and have given new impetus to long-standing questions about the function(s) of the complex and its ideological significance.2 It is the ideological aspect of the Templum Pacis that I would like to examine in this article. For in addition to the new evidence brought to light by the latest discoveries, some of which is discussed below, there is also some other, older evidence, mainly numismatic and epigraphic, that has been overlooked or not exploited in full in connection with the Templum Pacis. This evidence, which reveals the centrality of pax for Vespasian's public image and makes clear the triumphal and imperialist essence of the Templum Pacis, not only helps to contextualize the contemporary message of this ideo- logically charged imperial monument but also sheds some new light on the organization of state media and the nature of official communications in early imperial Rome.

The Templum Pacis was a large, multifunction monumental complex, erected in the cen- ter of Rome on the site, it is normally thought, of the Republican Macellum, which was prob- ably destroyed in the Neronian fire of 64.3 It was begun by Vespasian in 71 and completed and inaugurated in 75.4 The complex was known by many different names: templum (e.g.,

I would like to thank Bill Metcalf, Tony Corbeill, and the referees for MAAR for their perceptive and useful comments on an earlier draft of this article. All remain- ing errors are my own.

1 The most comprehensive recent overview of the new excavations in the imperial fora is La Rocca 2001.

2 La Rocca 2001, 195-207. See also the brief notice by Santangeli Valenzani 1999, summarizing work through April 1999 and promising a forthcoming supplement on the Templum Pacis in the Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica del Comune di Roma.

I The following account is intended simply as a brief overview of the Templum Pacis and its main features. Most of the archaeological evidence on which modern studies of the Templum Pacis are based is presented in Colini 1937; for photographs of the surviving portions of the structure, see Nash 1968, 2:440-445. Until the recent excavations in the area of the imperial fora, how- ever, most of the plan of the Templum Pacis was known

only from fragments 15a-c of the Severan Marble Plan; see Carettoni et al. 1960, pl. 20, and Rodriguez Almeida 1981, pl. 12. For some recent treatments of the Templum Pacis, with bibliography, see Anderson 1984, 101-119; Richardson 1992, 286-287; Darwall-Smith 1996, 55-68; Coarelli 1999; Packer 2003, 170-172. On the history of the site prior to the construction of the Templum Pacis, see De Ruyt 1983, 160-163.

4 The date for the initiation of the project is inferred from Josephus, who writes that Vespasian decided to build a temenos to Peace after the triumph over Judaea in 71 (BJ 7.158). Dio is the only source that provides a date for the inauguration of the Templum Pacis (T6 Tfl

EtpAvrs TEj1EVo0 KaOLEp9L0T), assigning it to the year of Vespasian's sixth consulship and Titus's fourth consul- ship, i.e., 75 (65.15.1); see the tables in Buttrey 1980, 6- 7, 18-19 for the chronology of Vespasian's and Titus's consulships. Neither Suetonius (Vesp. 9.1) nor Aurelius Victor (Caes. 9.7, epit. 9.8) provides an exact date for the completion of the complex. A passage in Statius could be interpreted to mean that Domitian completed the

MAAR 48, 2003

26 CARLOS F. NORENA

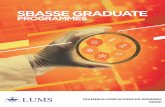

Fig. 1. Hypothetical reconstruction of the Il l Il ll I l- 1 II-1T original design of the Templum Pacis, before T I

the construction of the Forum Transitorium .

(after Anderson 1982, 104 ill. 3).

~TEMPLUM

ARGI LETUM

FORUM AUGUSTUM XFORUM JULIUM

Suet. Vesp. 9.1; Plin. HN 34.84), forum (Amm. Marc. 16.10; Symmachus Ep. 10.78, where it is called Forum Vespasiani) and aedes (Aur. Vict. Caes. 9.7) in Latin authors; TE[LEVOs (e.g., Joseph. BJ 7.158; Dio Cass. 65.15.1; Herod. 1.14.2), LEpOv (Paus. 6.9.3), and ELppvatiov (Dio Cass. 73.24.1) in Greek authors.5 This multiplicity of names bears on the ideological signifi- cance of the Templum Pacis and is a point to which we will return. In architectural terms, the complex as a whole consisted of two main elements: (1) a large, colonnaded square (c. 134 x 137 m), and (2) a set of rectangular rooms along the southeastern end of the square (fig. 1). The central square, from which four rectangular exedras with two columns in antis receded (two along each of the lateral walls), was probably an expansive garden, containing both an altar and a series of six longitudinal strips, as depicted on the Marble Plan, once interpreted as flower beds or hedges but now thought to be water canals or basins connected to foun- tains.6 The rooms along the southeastern end of the square consisted of a large central hall- screened from the main square by six columns and fitted with an apse and a statue base, possibly for the cult statue of Pax-and two smaller rectangular rooms on either side. In design and appearance, the Templum Pacis was less like the imperial fora with which it is often associated and more like the grand Hellenistic peristyles and their Roman counter- parts, the large porticoed squares that began to proliferate in the city in the second century

Templum Pacis (Silv. 4.3.17: et Pacem propria domo reponit: "and he [sc. Domitian] restores Peace to her own home"), but this line probably refers to Domitian's ex- tensive reworking of the northwest wall of the Templum Pacis, a necessary alteration for the construction of the Forum Transitorium (this is the conclusion of Anderson 1982, who nevertheless thinks that Statius is correct to credit Domitian with the "completion" of the complex); this line could also refer to the dedication of the cult statue of Pax (so Richardson 1992, 286 and Coarelli 1999, 69).

5 It is sometimes stated that templum was the "official" name of the complex (cf. Castagnoli 1981, 271; Coarelli 1999, 67), but this is not certain; note that the surviving

fragments of the Severan Marble Plan only preserve the word [P]ACIS. "Templum Pacis" was, nevertheless, the most common designation for the complex, and so the most accurate English designation is "Precinct of Peace" and not, as it is often rendered, "Temple of Peace," es- pecially since the existence of a temple proper (aedes) is not really supported by the archaeological evidence; see discussion in La Rocca 2001, 202-203.

6 Canals: La Rocca 2001, 195-196; basins: Coarelli 1999, 68, citing the Piazza d'Oro at the Villa of Hadrian as a possible analogy; cf. La Rocca 2001, 201. La Rocca also proposes that the garden was planted with "Gallic roses" (2001, 195).

MEDIUM AND MESSAGE IN VESPASIAN'S TEMPLUM PACIS 27

B.C.7 In terms of its contents, the Templum Pacis was exceptionally rich. It housed, in the first place, a number of the most famous artworks from the Greek world, mainly paintings and sculp- tures, as well as the spoils taken from Jerusalem in 71.8 In view of these holdings one scholar has recently characterized the complex as an "open-air museum."9 The Templum Pacis under Vespasian also seems to have displayed a Marble Plan of the city of Rome, a Flavian predeces- sor of the more famous Severan version.10 Finally, the Templum Pacis at one point contained a library, the Bibliotheca Pacis, but this is not attested until the middle of the second century, and it is unclear whether such a facility existed in the Vespasianic phase of the complex.'1

The precise functions of the Templum Pacis are not known. J. C. Anderson and F. Coarelli have suggested that the Templum Pacis played some role in the urban administra- tion of Rome and that the complex may even have served, already under Vespasian, as one of the headquarters of the praefectus Urbi (Urban Prefect).'2 We also know that the Templum Pacis came to be employed in part as a sort of private bank where deposits could be safe- guarded (Herod. 1.14.2). Beyond these utilitarian uses, the Templum Pacis served an im- portant cultural function. The garden design and extensive artistic holdings of the com- plex indicate that it was intended primarily as a space in the heart of the city for the dis- play of priceless works of Greek art in a pleasant setting, a classic example of what P. Zanker has referred to as imperial Volksbauten ("buildings for the people"), places where the ur- ban populace could engage with the ideals of Greek culture through the liberalitas ("per- sonal generosity") and "cultural patronage" of the emperor.'3 The Templum Pacis was a place, in other words, for a specific kind of otium ("leisure"), one with a pronounced cul- tural and indeed educational thrust.14

Discussion of the ideological significance of the Templum Pacis tends to focus on this I La Rocca 2001, 203-205 compares the overall design of the Templum Pacis to the so-called north market (mercato settentrionale) at Miletus (late third/early sec- ond century B.C.), to the sanctuary of Zeus Soter at Mega- lopolis (mid-fourth century B.C.), and to the sanctuary of Zeus at Dodona (rebuilt at the end of the third cen- tury B.C.). He also suggests that the structure recently identified by De Caprariis as the Porticus Vipsania (late first century B.C.) offers the most immediate Roman pre- cedent to the Templum Pacis, but the identification of this structure as the Porticus Vipsania is disputed (see La Rocca 2001, 205 n. 173 for the references and atten- dant debates). Anderson 1984, 111 and Darwall-Smith 1996, 65 compare the Templum Pacis to the Porticus Liviae. In addition, the Templum Pacis is often cited as the model for the Library of Hadrian in Athens; see Coarelli 1999, 69-70. One major problem that current excavations might solve is that of communications be- tween the Templum Pacis and the complexes that sur- rounded it to the south (Basilica Paulli) and, after Domitian's ambitious building program in the area, to the west (Forum Transitorium). For some preliminary remarks on the problem of communications between the various imperial fora, see La Rocca 2001, 211.

8 See, e.g., Joseph. BJ 7.159-162; Plin. HN 12.94, 34.84, 35.102-103, 35.109, 36.27, 36.58; Paus. 6.9.3; Juv. 9.23; Proc. BG 4.21. For a full list of known works housed in the Templum Pacis, see Coarelli 1999, 68; see also Darwall-

Smith 1996, 58-65. How exactly the artworks in the Templum Pacis were installed and displayed is still unclear.

9 Darwall-Smith 1996, 65, citing the Porticus Octaviae as an earlier example.

10 Evidence for the Flavian Marble Plan is meager; see discussion, with references, in Castagnoli 1981, 263-264; Darwall-Smith 1996, 64-65.

" Bibliotheca Pacis: Gell. 5.21.9, 16.8.2.

12 Anderson 1984, 116-117; Coarelli 1999, 70; cf. Richardson 1992, 287.

13 Zanker 1997, esp. 17-18 on the Templum Pacis, 19 and 42 on the "pedagogical urgency to connect with clas- sical culture," and 5-6 on the notion of "cultural pa- tronage" (Kulturforderung). See also Kuttner 1999 on Pompey's "Garden Museum" (the Porticus of Pompey), another site where Romans could engage with Greek culture in an ornamental, garden setting.

14 This cultural function of the Templum Pacis is also stressed by Darwall-Smith 1996, 65, though he may go too far when he claims that "The Temple of Peace was solely designed for otium, not negotium," as there is some evidence, admittedly slight, of an administrative func- tion already under Vespasian (see above n. 12).

28 CARLOS F. NORENA

last aspect of the complex, especially the public display of famous works of art there.'5 A frequently cited comment by Pliny the Elder serves as the basis for interpretation along these lines (HN 34.84):

atque ex omnibus, quae rettuli, clarissima quaeque in urbe iam sunt dicata a Vespasiano principe in templo Pacis aliisque eius operibus, violentia Neronis in urbem convecta et in sellariis domus aureae disposita.

The most famous of all the works I have discussed are now in Rome, dedicated by the emperor Vespasian in the Templum Pacis and in his other buildings. They were carted into the city by the impetuosity of Nero and placed in the sitting rooms of the Domus Aurea.

The key to Pliny's statement, of course, is the obvious polarity between the generosity of one emperor and the rapacity of the other. In striking contrast to Nero, Vespasian "gave" to the public what his predecessor had sequestered in the privacy of his Domus Aurea, an action that recalled Agrippa's appeal a century earlier for the public display of privately held artworks."6 The permanent exhibition in the Templum Pacis of artwork that had been appropriated by Nero is normally related to Vespasian's much bolder decision to raze the Domus Aurea entirely and construct the new Amphitheatrum Flavium on part of its site.'7 Again, by converting imperial land to land for public use, Vespasian was symbolically turn- ing over to the populus Romanus what had been monopolized by a "bad" emperor. Scholars have also seen the Templum Pacis as a useful vehicle for Vespasian to connect himself to the model of the "good" emperor, Augustus. A major imperial monument of this sort dedicated to pax cannot have failed to remind contemporaries of Augustus's Ara Pacis.18 In addition, the Templum Pacis faced the Forum Augustum directly and was clearly meant to be pendant to it.'9 The Templum Pacis made double reference, therefore, in theme and location, to Augustus, an important component of Vespasian's larger policy of establishing a notional connection with the founder of Rome's first dynasty.20 Recent findings add to this picture. Among the items discovered in the latest excavations of the Templum Pacis area were three statue bases that once carried works by the Athenian sculptors Praxiteles, Kephisodos, and Parthenokles.2' Together with the one statue base found in earlier excavations, bearing the

15 E.g., Castagnoli 1981, 273; Isager 1991, 103, 183, 224- 229; Darwall-Smith 1996, 65-67; Griffin 2000, 20. On the problem of Greek art in Rome in general, see Pollitt 1978, esp. 168-169 on the Templum Pacis.

16 Agrippa's plea: Plin. HN 35.26.

17 As Martial writes (Spect. 2.5-6), "Here, where the re- markable structure of the honorable Amphitheater is raised up, Nero's artificial lakes used to lie" (hic ubi conspicui venerabilis amphitheatri / erigitur moles, sta- gna Neronis erant); see briefly Griffin 2000, 20.

18 Weinstock (1960, 51) argued from Vespasian's build- ing of the Templum Pacis that "we can infer . .. that the Augustan Ara Pacis no longer existed." I do not see the logic of this claim. On the connection between the Ara Pacis and the Templum Pacis, see Castagnoli 1981, 271- 272; Levick 1999, 70.

19 On the relation of the Templum Pacis to the Forum Augustum (and to the Forum Iulium), see briefly Castagnoli 1981, 271. It is important to consider the spa- tial relation between the Templum Pacis and the Forum Augustum before the building of the Forum Transi- torium; see figure 1.

20 This policy is also reflected in the Lex de imperio Vespasiani, which figured Vespasian as Augustus's po- litical heir, and in Vespasian's decision to style him- self "Imperator Caesar Augustus Vespasianus" (note the absence of the nomen Flavius), a formula that con- spicuously recalled the founder of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. On Vespasian's legitimite augusteenne, see Hurlet 1993.

21 See La Rocca 2001, 197-201 for these finds, with line drawings of the three stones on 199.

MEDIUM AND MESSAGE IN VESPASIAN'S TEMPLUM PACIS 29

Pythokles of Polikletos, another Athenian sculptor, these four sculptures suggest a strong Athenian presence in the holdings of the Templum Pacis, an artistic and political choice that may well reflect an attempt on Vespasian's part to mimic Augustus's marked preference for Attic classicism in the arts.22 Through the Templum Pacis, then, in ways both obvious and subtle, Vespasian could simultaneously align himself with the "good" Augustus and distance himself from the "bad" Nero.

This more or less standard interpretation of the ideological resonance of the Templum Pacis is both plausible and convincing, especially in light of the most recent discoveries, but it is also incomplete. To relate the Templum Pacis to the public display of Nero's art collec- tion and the destruction of the Domus Aurea on the one hand, and to the Augustan proto- types of the Ara Pacis and Forum Augustum on the other, is correct, but what these readings do not emphasize sufficiently is the importance of the personification to which this monu- mental complex was dedicated. Pax was a core ideal in the official construction of Vespasian's public image and one of the central claims upon which the legitimacy of his principate was based. It is, therefore, only through a careful examination of the public advertisement of pax under Vespasian-and of the particular meanings with which Vespasian's pax was invested- that we can recover the contemporary message of the Templum Pacis.

Perhaps the most important vehicle for the official commemoration of pax under Vespasian was the imperial coinage. Pax was a regular coin type under Vespasian, as has long been rec- ognized, but the iconographic evidence for pax on Vespasian's coinage has not been treated adequately.23 In particular, what has been overlooked is the relative commonness or rarity of the different reverse types on Vespasian's coinage, including those representing pax. When scholars write that "Pax is a dominant theme," for example, or that "Pax is frequent on [Vespasian's] coins," they do not normally indicate how "dominant" or "frequent" these Pax types were, nor do they provide any evidence for their claims.24 In order to make useful state- ments about the role played by pax in the visual language of Vespasian's coinage-in order, that is, to understand whether Vespasian's Pax types were produced in large or small num- bers relative to other reverse types-it is necessary to measure the relative frequency of all the different reverse types on Vespasian's coinage and to base this measurement on empirical evidence. And the best method to assess the relative frequency of reverse types, as I have argued elsewhere, is to tabulate the number of specimens found in published hoards.25 Be- cause the circulation of imperial coins was not local but empire-wide, and because there is no reason to suspect any correlation between hoarding and reverse types, the number of speci- mens found in hoards should be a good indicator of the relative frequency with which these types were produced. On the basis of the hoard evidence, therefore, it is possible to deter- mine the significance, in quantitative terms, of Pax types on Vespasian's coinage.

For the purposes of this study I have limited my investigation to denarii minted in Rome

22 For Attic classicism under Augustus, see Zanker 1988, esp. 57-65 on the politics of style in triumviral Rome.

23 The best introduction to the iconography of Ves- pasian's coinage is still, remarkably, Mattingly's introduc- tion to Vespasian in the second volume of BMC (1930); see also Bianco 1968, Buttrey 1972, and Pera 1981. Note that the Pax type was one of the few reverse types on Vespasian's coinage that did not revive a pre-Flavian type; see discussion in Buttrey 1972.

24 The quotations are from Ramage 1983, 211 and Weinstock 1960, 52; cf. Darwall-Smith: "[Pax] appears frequently on coins of 69-79" (1996, 61).

25 Norefia 2001, 147-152. The argument for the value of this method is also stated briefly by Carradice 1998, 97- 99. Note that Carradice is currently preparing a revised edition of RIC II that will provide new frequency esti- mates for Flavian coin types.

30 CARLOS F. NORENA

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

2 K _ _ I _ * _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

A.D. 69-70 70-71 72-73 73 74 *Pax 75 76 77-78 78-79 A.D. 79

Fig. 2. Relative frequency of Pax types on denari4, expressed as a percentage of all reverse types, A.D. 69-79 (N 6, 665). Note: It was not possible in every case to date the coins to a single calendar year.

For the chronology of Vespasian's titulature, see Buttrey 1980, 8-17, with table 1.

between 69 and 79 and have drawn on the same hoard evidence that I employed in my study of imperial virtues.26 Pax types also appeared on aurei of 69-71, 72, 73, and 75, and on vari- ous aes denominations throughout Vespasian's reign, but the silver coinage is much better suited to an investigation of this sort since the denarius was the most heavily minted denomination of the imperial coinage and had the widest dissemination.27 In what follows, then, I will focus on the denarius, but it is important to bear in mind that the Pax type was also minted, with varying degrees of frequency, on other denominations during Vespasian's reign.

As a first step toward a better understanding of the Pax type on Vespasian's coinage, I have measured on a year-by-year basis the relative frequency of the Pax type on denarii minted between 69 and 79 (fig. 2). The results show that the relative frequency of the type fluctuated sharply from year to year, a pattern that is consistent with T. V. Buttrey's observation that coin types under Vespasian tended to change on an annual basis.28 The next step, of course, is to explain the shape of these fluctuations. That the fluctuations in the relative frequency of the Pax type are neither random nor meaningless, but instead reflect shifting degrees of offi- cial emphasis on the ideal of pax, becomes clear when these data are situated in a historical and topical context. It is to that larger context that we now turn.

26 For a full list of hoards consulted, with references, see Norefia 2001, 165-168.

27 For Pax types under Vespasian, see indices to BMC and RIC, On the volume of production of the denarius,

see Duncan-Jones 1994, ch. 11, esp. 167, table 11.1.

28 Buttrey 1972, 95: "There was a strong tendency in the Rome mint under Vespasian to employ a reverse type for a limited period, apparently one year."

MEDIUM AND MESSAGE IN VESPASIAN'S TEMPLUM PACIS 31

The prominence of the Pax type in the year 69-70 in particular, and for the period 69-71 as a whole, is a direct result of the immediate conditions in which the type was produced. The revolt of Vindex, the fall of Nero, and the struggles for the throne in 68-69 caused the worst violence in Italy since the civil wars of the triumviral period.29 The armed conflicts between the various contenders will have brought in their wake unsettled conditions in the countryside (at least in northern Italy), the disruption of commerce, and the ominous threat of property loss and bloody reprisals. The disorder to which the sudden end of the Julio- Claudian dynasty had given rise manifested itself even in the city of Rome, culminating in the Vitellian burning of the Capitol, an episode that made such an impression on Tacitus that he could call it the "most sorrowful and abominable crime" the Roman state had suffered since its foundation.30 That judgment is perhaps exaggerated, but beneath the rhetoric one can discern the fear and anger felt by those who had experienced firsthand the violence of the civil war. For the victor in this civil war it was imperative first to establish, and then to adver- tise, a firm and lasting peace. The strong quantitative emphasis on pax that characterizes Vespasian's silver from 69 to 71 reflects the importance attached to establishing a notional connection between the new emperor and the peace that his rule had bestowed on the Ro- man world. Pax, in other words, had an unambiguous, topical significance at the beginning of Vespasian's reign, and this is illustrated clearly in the high relative frequency with which the Pax type was minted at that time.

After 70-71, the Pax type disappeared from Vespasian's silver and was not minted again until 75, when it reached its highest relative frequency among reverse types (81 percent).31 Following a small issue in 76 (just 4 percent of all reverse types), the Pax type was not pro- duced again on denarii for the remainder of Vespasian's reign. The sudden and dramatic peak in the relative frequency of the Pax type on denarii of 75, higher even than the peak in 69- 70, calls for an explanation but one different from that offered for the prominence of the type in the period 69-71, since the extinction of the civil wars of 68-69 would not have had quite the same resonance in the middle years of Vespasian's reign. Pax was also a topical theme in 75, of course, as this was the year in which the Templum Pacis, Vespasian's first large-scale monument in Rome, was inaugurated (see above n. 4). Additional numismatic and epigraphic evidence will show that this correspondence between the inauguration of an im- perial monument and the proliferation of a specific coin type was not merely coincidental and that the massive Pax issue of 75 should be seen as part of a coordinated campaign to articulate a core imperial ideal across a range of official media. We will return to this corre- spondence in our conclusions. First, however, it is necessary to examine the other evidence for the public prominence of pax under Vespasian.

Two symbolic actions on the part of Vespasian himself are illuminating for the ideologi- cal significance of pax during his reign. The first was the closing of the Temple of Janus fol- lowing the conquest of Judaea in 70, the traditional sign that peace reigned throughout the Roman world, terra marique ("on land and at sea").32 Nero, too, had closed the Temple of

29 Wellesley 2000 provides a useful account of this tu- multuous period.

30 Tac. Hist. 3.72: id facinus post conditam urbem luctuosissimum foedissimumque rei publicae populi Romani accidit.

31 BMC 161-164 = RIC 90; see figure 2. Note that Pax

did appear on aurei of 72 and 73.

32 For the closing of the Temple of Janus after the con- quest of Judaea in 70 we depend on the testimony of Orosius, a late (early fifth century) but presumably reli- able source for this sort of datum: Oros. 7.3.8 (credit for the closure given to Titus), 7.9.9, 7.19.4.

32 CARLOS F. NORENA

Janus and had advertised this closure with an unambiguous coin legend, "Because peace had been established for the Roman people on land and at sea he [Nero] closed the Temple of Janus," but we may suspect that if Vespasian hoped through his closure of the Temple of Janus to recall any of his predecessors, it was not Nero but Augustus, who had also closed the temple, not once but three times, and had devoted an entire rubric of his Res Gestae to this accomplishment.33 The second symbolic action taken by Vespasian to commemorate pax was the naming of a colonia in Thrace after the personification, the colonia Flavia Pacis Deultensium-an action that again recalled Augustus, who had also named a colony after pax.34 We also know of a vicus Pacis at Divodorum in the province of Belgica that might have been created by Vespasian, as S. Weinstock has suggested.3" These actions underline Vespasian's insistence both on making pax one of the core ideals of his principate and, closely related to this, on following an Augustan model in his public actions.

Scattered evidence from Vespasian's reign indicates a degree of popular response to the contemporary celebration of pax. It is in the epigraphic record that we can trace some of the impact of this official program. Two inscriptions erected in Rome during Vespasian's reign commemorate pax. The first was set up by the iuniores of the Tribus Sucusana, on the emperor's birthday in 70, to the pax aeterna of the imperial house (CIL 6.200 = ILS 6049; Rome, A.D. 70):

Paci aeternae / domus Imp(eratoris) / Vespasiani Caesaris / Aug(usti) / liberorumque eius / sacrum / trib(ui) Suc(usanae) iunior(es) / dedic(atum) XV k(alendas) Dec(embris) / L. Annio Basso / C. Caecina Paeto co(n)s(ulibus).

To the Eternal Peace of the house of the Imperator Vespasian Caesar Augustus and his chil- dren, [this memorial is] sacred, [set up by] the iuniores of the Tribus Sucusana, dedicated on November 17th during the consulships of Lucius Annius Bassus and Gaius Caecina Paetus.

Since we know almost nothing about the manner in which subjects chose to honor their em- peror, it is impossible to prove a causal connection between, on the one hand, the closing of the Temple of Janus in 70 and the relatively heavy minting of the Pax type throughout the year 70, both official actions, and, on the other hand, the spontaneous and private dedication in that same year by an urban tribe in Rome to the Eternal Peace of the imperial house. The chronological correspondence between these official and unofficial commemorations of the ideal of pax is nevertheless suggestive.

The second inscription, commemorating not just pax in general but specifically pax Augusta-and therefore reinforcing the link to Augustus-was set up by the curatores of the same Tribus Sucusana at some point during Vespasian's reign (CIL 6.199 = ILS 6050; Rome, A.D. 75?):

33 The full Neronian coin legend is Pace p(opulo) R(omano) terra mariq(ue) parta Ianum clusit (cf. RIC F2 50, 58, 263-27 1, etc.). Augustus's closure of the Temple of Janus: RG 13; Livy 1.19.2-3; Suet. Aug. 22.

34 Colonia Flavia Pacis Deultensium: CIL 6.3828 = ILS 6105 (Rome, A.D. 82). The colony was a settlement at Deultum of veterans from the Legio VIII Augusta (mod- ern Debelt in Bulgaria); cf. Plin. HN 4.9; Ptol. 3.11.11. Augustus's colony Pax Augusta, in Gaul, is known from

Strabo 3.2.15: i TE EV TOt; KEXTLKO?; naUavTyo15Ta. It seems that Caesar had also named colonies after Pax, in Lusitania (CIL 2.47 = ILS 6899) and in Gallia Nar- bonensis (CIL 12.3203 = ILS 6984); as always, there is some debate over whether these were Caesarian or Au- gustan colonies. See discussion in Weinstock 1960, 46 (with nn. 25-26), 48 (with n. 44).

35 CIL 13.4304 = ILS 4818; for the suggestion that the vicus Pacis was Vespasianic, see Weinstock 1960, 51 n. 92.

MEDIUM AND MESSAGE IN VESPASIAN'S TEMPLUM PACIS 33

Paci August(ae) / sacrum.... curatores trib(ui) Suc(usanae) iunior(um) s(ua) p(ecunia) d(ono) d(ederunt) / permissu M. Arricini Clementis.

To Pax Augusta, [this memorial is] sacred. . .. The curatores of the iuniores of the Tribus Sucusana gave [it] as a gift with their own money, with the authorization of Marcus Arricinus Clemens.

In setting up this memorial, the curatores are careful to record the authorization of M. Arricinus Clemens, whose career may provide a clue to the date of the dedication. Clemens was installed by Vespasian as praetorian prefect in 70 (Tac. Hist. 4.68), was presumably removed from this post when Titus assumed it in 71, later held two suffect consulships, the first in 73 (CIL 6.2016) and the second probably in the reign of Domitian, and served at some point in Vespasian's reign as urban prefect.36 It is as urban prefect that Clemens would have been in a position to authorize a dedication like that offered by the Tribus Sucusana, and since the urban prefecture was a consular post, Clemens must have held it sometime after his suffect consulship in 73 and before Vespasian's death in 79. The inscription, therefore, should also be dated to between 74 and 79. Because the year 75 witnessed both the dedication of the Templum Pacis, recalling Augustus's Ara Pacis, and the proliferation of the Pax type on denarii, it is tempting to date this dedication to Pax Augusta to 75 and to interpret it as a sort of echo of the official celebra- tion of Pax during that year. Such a close dating is not, however, necessary for the argument about the symbolic significance of Pax. What really matters is the general association of Vespasian with the ideal of pax, an association to which these various dedications contributed.

Finally, there was at least one contemporary commemoration of pax Augusta outside of Rome. During Vespasian's reign an inscription set up to Titus in Valentia, in the province of Hispania Tarraconensis, apparently on a statue base, honors the heir apparent as conservator pacis Augustae (CIL 22/14.1.13 = CIL 2.3732 = ILS 259; Valentia, A.D. 69-79):

[Ca]es(ari) T(ito) Imp(eratori) / Vespasiano Aug(usto) / [V]espasiani f(ilio) conser/[v]atori pacis Aug(ustae).

To Caesar Titus Imperator Vespasian Augustus, son of Vespasian, Preserver of the Au- gustan Peace.

This honorific title was, as far as we know, unprecedented, and it never again appeared in the epigraphic record. The odd arrangement of Titus's titulature-he would normally be styled as "Imperator Titus Caesar Vespasian Augustus"-suggests strongly that the dedicator of this memorial was a provincial and not a Roman official.37 What this dedication to the "Preserver of the Augustan Peace" reveals is a quite remarkable correspondence between center and periphery in the expression of a current and fashionable imperial ideal. It should also be noted that another dedication from Spain, set up to pax Augusta by a sevir Augustalis in the Flavian municipium of Arva, in the province of Baetica, may also be Vespasianic.38 These

36 For the details of Clemens's career, including the evi- dence for the urban praetorship, see PIR2 A 1072.

37 The most comprehensive treatment of Titus's titulature is Pick 1885 (though his conclusions on the constitutional significance of variations in Titus's titulature cannot al- ways be trusted); see also Buttrey 1980, 18-25 for the

chronology of Titus's titulature under Vespasian.

3 CIL 2.1061 (Arva, A.D. 69-79?): Paci Aug(ustae) / sacrum / L. Licinius / Crescentis / lib(ertus) Hermes / IIIIII VirAug(ustalis) / d(e) s(ua) p(ecunia) d(ono) d(edit). For the suggestion that the dedication might have been made under Vespasian, see Weinstock 1960, 51 n. 92.

34 CARLOS F. NORENA

examples show that there was indeed a popular association between pax and Vespasian's re- gime and that this association could be acknowledged and publicized even in the provinces.

So the cumulative evidence from Vespasian's reign points to the importance of pax for the emperor's public image. This is the specific ideological context in which we should see the inauguration of the Templum Pacis in 75. But these numerous commemorations and ex- pressions of Peace in Vespasianic Rome also raise the problem of the precise nature of the pax being celebrated by the templum in its honor. This is an especially important question because there were two basic and discrete senses of pax in the Roman lexicon, and neither the intentions of the regime in building this monumental complex nor the popular reception of it can be understood without a clear sense of the type of pax memorialized by the Templum Pacis.

In very broad terms, the concept of pax for the Romans had both a domestic and civilian aspect as well as a foreign and military one.39 The domestic and civilian pax, often identified as pax civilis ("civic peace"), denoted above all the absence of civil war. This was the sort of pax that, following civil conflict, "brought back cultivation to the fields, respect for religion and safety to men," as Velleius Paterculus put it, the sort of pax that could be grouped to- gether with other civic ideals such as otium ("leisure, repose"), iustitia ("justice"), and tranquillitas ("quietness").40 The close connection between this civilian pax and domestic con- cord is most explicit in the writings of Cicero, in which pax is routinely collocated with concordia ("harmony, concord").4" As he writes, "When there is lack of concordia, there is no pax civilis at all."42 Pax in this domestic and civilian sense-essentially the absence of civil conflict-must not be confused with the sort of pax that the Romans imposed upon con- quered peoples. This other, military pax, which originally referred to a "pact" concluding a war but which came to take on the more general meaning of capitulation to Rome, depended on Roman virtus. In the Res Gestae, for example, in the same rubric in which his closures of the Temple of Janus are recorded (RG 13), Augustus highlights the foundation of military might upon which the pax Romana rested, as pax is unambiguously made the product of mili- tary victory: "peace gained through military victories" (parta victoriis pax).43 Similarly, the Ara Pacis was a monument not to domestic concord but to imperialism and the military paci- fication of the Roman world. Voted to Augustus by the Senate in response to the subjugation of Gaul and Spain (RG 12.2) and depicting on prominent panels both Mars and Roma (the latter seated on weapons), the Ara Pacis memorialized a pacified imperium created and pre- served by Roman military force.44 This was precisely the sort of pax to which Tacitus was

39 For these two senses of pax, see discussion in Weinstock 1960, 45-46; Woolf 1993, 176-179; Kuttner 1995, 105. For the full lexical and semantic range of pax, see TLL 10.1:6.863-878 (U. Keudel).

40 Vell. Pat. 2.89.3: finita . . . bella civilia, . . . revocata pax, . . . rediit cultus agris, sacris honos, securitas hominibus. Pax and otium: Cic. Agr. 1.8.23, Mur. 1.1, 37.78, Att. 9.11A.1. Pax and iustitia: Sen. Clem. 1.19.8 (in this passage pax is also grouped together with pudicitia ["modesty"], securitas, and dignitas ["honor, rank"]). Pax and tranquillitas: Cic. Mur. 1.1.

41 See Jal 1961, with ample references. Later writers also associated pax with concordia; see, e.g., Sall. Hist. 1.55.24M, 1.77.5M, 1.77.1OM; Livy 4.10.8, 9.19.17; Curt.

10.8.23; Tac. Hist. 1.56.6, 2.20.4, 3.70.6, 3.80.4.

42 Cic. Phil. 7.8.23: in discordia autem pax civilis nullo pacto est.

43 The military aspects of pax are examined in Gruen 1985, a study of pax in Augustus's public image; for a more general treatment of this theme, see also Gruen 1996, 188-194; cf. Woolf 1993 on the imperialist ideol- ogy encapsulated by the notion of pax Romana.

44 So Gruen 1985, 61-62; 1996, 193-194. See also Kuttner 1995, 104-106, who argues that the children depicted on the procession friezes represent barbarian youths-the pacati themselves (i.e., "those having been pacified").

MEDIUM AND MESSAGE IN VESPASIAN'S TEMPLUM PACIS 35

referring when he assigns to the Caledonian chieftain Calgacus the famous phrase, "they make a wasteland and call it peace" (solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant).4

These two types of pax, then, the "civilian" and the "military," are quite distinct from each other in sense and usage. Which pax did the Templum Pacis proclaim? What, in other words, was the contemporary message of this monumental complex? A number of indications point to the proclamation and celebration of military pax. The Templum Pacis was begun after the conquest of Jerusalem in 71 (Joseph. BJ 7.158). It celebrated the victory over Judaea and, even more revealing, housed the spoils taken from Jerusalem and displayed in the triumph of Vespasian and Titus in 71 (Joseph. BJ 7.162). The Forum of Trajan also housed the spoils of a defeated foreign enemy, the Dacians, and the military character of that complex is beyond question.46 A prominent announcement of foreign conquest-for that is how the Romans chose to represent the suppression of provincial rebellions against Roman rule-was also useful to Vespasian for publicizing the military credentials of the upstart dynasty, an important step in establishing the political legitimacy of the new regime.47 Finally, we may speculate that Vespasian would not have chosen to memorialize the domestic peace that followed the civil war of 68-69, since this would only serve as a permanent reminder of the civil violence that had enabled his ascent to the throne. It was not until the construction of the Arch of Constantine, in fact, more than 240 years later, that a victory in a civil war was openly com- memorated on a public monument in Rome.48 A civil war monument had no place in Vespasianic Rome. Contemporary observers of the new Templum Pacis might well have re- flected on the domestic harmony that obtained under the principate of Vespasian, but that cannot have been the principal message the regime intended to send in erecting a monument to pax.49 The Templum Pacis was instead a monument celebrating the pacification of foreign peoples and the power of the Roman war machine under the guidance of the new Flavian dynasty.50

This is by no means the conventional interpretation of the pax commemorated by the Templum Pacis. In the most recent study of Flavian public building in Rome, for example, J. Packer, within the space of a single chapter, suggests in one place that the Templum Pacis celebrated the victory over Judaea and in another that it proclaimed the restoration of public order after the events of 68-69.5' It is unlikely that the Templum Pacis memorialized both

45 Tac. Agr. 30.4. For Tacitus the pax Romana can be an object of fear: "those who fear our peace" (Ann. 12.33: quipacem nostram metuebant; cf. Tac. Agr. 20.1).

46 For the military character of Trajan's Forum, see, most recently, Gros 2000.

47 Rosenberger 1992 discusses the different terms for warfare in the Roman lexicon and demonstrates (esp. 150-160) that provincial revolts and Rome's military re- sponse to them were categorized not as civil wars but as foreign wars.

48 For the relief frieze on the Arch of Constantine de- picting Constantine's victory in the civil war, see Ruysschaert 1962-1963 (I would like to thank Elizabeth Marlowe for this reference). Augustus's Actian arch could also be seen as a commemoration of victory in a civil war, but the naval victory at Actium was presented as a victory over eastern decadence and despotism (see Wallace-Hadrill 1993, ch. 1; cf. Dio Cass. 51.19.1-5 on

Augustus's triumph over Cleopatra, not Antony), and in any case the Actian arch-if it was ever built in the first place-was soon replaced by Augustus's Parthian arch; see discussion in Gurval 1995, 36-47, arguing that a spe- cifically "Actian" arch never existed. On the Roman dis- taste for celebration of victory in civil war, see Rosenberger 1992, 156-158; Mattern 1999, 170 n. 32.

49 The intended message of an imperial monument did not necessarily correspond perfectly to its popular re- ception. As Woolf (1993, 177) writes, "Both Augustus and Vespasian were careful to make victories over for- eign opponents the ostensible occasions for promoting the cult of pax, as for closing the doors of the temple of Janus, but the evocation of civil harmony seems an ines- capable sub-text."

50 Rightly emphasized by Griffin 2000, 15 and by Beard 2003, 555 and 557; see also Mattem 1999, 193 with n. 105.

51 Packer 2003, 170, 197.

36 CARLOS F. NORENA

types of pax,52 however, since they were so different from each other, and nothing in the ar- chitectural or artistic program of this complex suggests that it was meant to proclaim the peace following the civil war of 68-69. There is also a hint of confusion in R. H. Darwall- Smith's observation that the "symbolic nature" of the name Templum Pacis distinguished it from the porticoes to which it was architecturally similar, "as Peace was truly restored to the Romans."53 This formulation is not necessarily incorrect, but its emphasis is misplaced. What the Templum Pacis really commemorated was not the fact that Peace had been "restored to the Romans" but rather that it had been imposed, forcibly and as the result of military conquest, on the population of Judaea. Like the Ara Pacis, the Templum Pacis expressed martial ideals.

In addition to the evidence of the Templum Pacis itself and the testimony of authors like Josephus, there is also a significant quantity of indirect evidence for Vespasianic Rome that points to what P. Gros, writing about Rome under one of Vespasian's successors, Trajan, has called the "militarization of urbanism."" This "militarization" of the urban image of Rome already under Vespasian bears directly on our interpretation of the Templum Pacis. The first, and perhaps the most important, item of evidence for our purposes is one of the original dedicatory inscriptions of the Amphitheatrum Flavium, a text we can now read on the basis of A. Alfoldi's brilliant and universally accepted reconstruction." The reconstructed text, with Alfoldi's proposed restorations, reads:

J[mp(erator)] Caes(ar) Vespasi[anus Aug(ustus)] / amphitheatru[m novum (?)] / [ex] manubis (vac.) [fieri iussit (?)].

Imperator Caesar Vespasian Augustus ordered the New Amphitheater to be built, . [paid for] by the proceeds of war spoils.

This dedication tells us something we would not otherwise have known: the Flavian Amphi- theater was a victory monument.56 Looming in the center of the city as a "core nodal point" in Rome's urban fabric,'7 the Flavian Amphitheater was Vespasian's most prominent stamp on the city (even though unfinished at the time of his death), and this dedicatory inscrip- tion-and the many others like it-would have reminded the amphitheater's first visitors that this enormous urban amenity was not simply the product of Vespasian's liberalitas but was

52 Pace Levick 1999, 70.

53 Darwall-Smith 1996, 67. For similar statements on the Templum Pacis, emphasizing the commemoration of domestic concord, see, e.g., Castagnoli 1981, 271; Gunderson 2003, 642: "A temple of Peace sends an ob- vious message: with Vespasian peace has returned to the state. "

54 Gros 2000, on "la 'militarisation' de l'urbanisme trajanien. "

55 Alf6ldi 1995. The restored texts also appear in a fas- cicle of CIL 6 as CIL 6.8.2 40454a. For one reviewer's appreciation of Alfoldi's "spectacular reconstruction," see the comments of F. Millar in the Journal of Roman Archaeology 11 (1998) 434. Alf6ldi observes that this text is not the dedicatory inscription of the Amphi-

theatrum Flavium but rather an abbreviated version of what must have been a much longer inscription, located perhaps on a podium in the arena itself (1995, 223, with n. 70).

56 The spoils cited in the dedication (manubis) can only refer to those taken from Jerusalem; see discussion in Alf6ldi 1995, 217-219.

57 I borrow the term "core nodal point" from Lynch 1960, who defines nodes as "strategic spots in a city into which an observer can enter, and which are the intensive foci to and from which he is traveling" (47), noting also that "Some of these concentration nodes are the focus and epitome of a district, over which their influence radiates and of which they stand as symbol. They may be called cores" (47-48). The Flavian Amphitheater would also qualify as a "landmark" in Lynch's typology (1960,78-83).

MEDIUM AND MESSAGE IN VESPASIAN'S TEMPLUM PACIS 37

more specifically the monumental result of the Flavian conquest of Judaea.i8 The Flavian Amphitheater stood in a long line of "manubial" monuments at Rome, but its grandeur and topographical centrality assured that it would never be eclipsed as the most conspicuous ar- chitectural expression of Roman military victory.59

Also relevant to our interpretation of the Templum Pacis is the extension of the pomerium, Rome's religious and civic boundary, a symbolic act of the highest importance carried out by Vespasian and Titus as censors in 75 on authority formally granted to Vespasian by the lex de Imperio Vespasiani (CIL 6.930 = ILS 244, 11. 14-16). The pomerial extension under Vespasian is known to us from four Vespasianic boundary stones (cippi) found in sitU.60 The text of the most recently discovered of these boundary stones reads:

[I]mp(erator) Cae[sar / Vepasianu[s (sic)] / Aug(ustus) pont(ifex) ma[x(imus)] / trib(unicia) pot(estas) VI imp(erator) XI[V] / p(ater) p(atriae) censor / co(n)s(ul) VI desig(natus) VII / T(itus) Caesar Aug(usti) [f(ilius)] / Vespasianus imp(erator) VI / pont(ifex) trib(unicia) pot(estas) IV / censor co(n)s(ul) IV desig(natus) V / auctis p(opuli) R(omani) finibus / pomerium ampliaverunt / terminaveruntque.

Imperator Caesar Vespasian Augustus ... and Titus Caesar Vespasian, son of Augustus, . . . because the territory of the Roman people had been increased, enlarged and marked the boundaries of the pomerium.

As the text of the boundary stones themselves makes explicit, the extension of the city's pomerium was the direct result of the extension of the Romans' empire.61 A pomerial exten- sion, in other words, was a fundamentally imperialistic statement, and the fact that Vespasian extended the pomerium in precisely the same year in which he dedicated the Templum Pacis can hardly be coincidental (see below).

That is not all. Among the honors voted to Vespasian and Titus after the capture of Jerusa- lem, according to Dio, were triumphal arches (65.7.2: cLt6Es TpoTraLo4opoL). Though Dio neither specifies the exact number of these triumphal arches nor confirms that they were in fact built, there is no reason to doubt their existence.62 The triumphal arch, after all, was for

58 This dedicatory inscription confirms the statement by Suetonius that Vespasian "built" (fecit, not "begun," as it is often translated) the amphitheater (Vesp. 9.1), but the archaeological evidence indicates that the structure was unfinished at the time of Vespasian's death; see Packer 2003, 169 n. 15. Note that Augustus, too, according to Suetonius (Vesp. 9.1), wanted to build an amphitheater in the center of the city; Vespasian's construction of a per- manent amphitheater is therefore one more case in which he followed a putative "Augustan" model in his public actions. It should also be noted that Titus later altered the dedicatory inscription to read "Imperator Titus Cae- sar Vespasian Augustus ordered . . . ," thereby appropri- ating credit for the entire structure, which was, to be fair, dedicated during his principate. For the altered text, see Alfoldi 1995, 210 and 212, fig. 4; for the dedication un- der Titus, see Darwall-Smith 1996, 82-89.

59 Alfoldi 1995, 219-222 discusses the tradition of "manubial" monuments under the emperors, including the Templum Pacis (222, with n. 66).

60 CIL 6.31538a-c; Romanelli 1933, 241.

61 Tacitus also makes clear the connection between pomerial and imperial enlargement (Ann. 12.23): "And Claudius enlarged the pomerium of the city, according to the ancient custom whereby those who had expanded the empire were permitted to extend the boundaries of the city" (et pomerium urbis auxit Caesar, more prisco, quo iis qui protulere imperium etiam terminos urbis propagare datur). Prior to Vespasian, the pomerium had been enlarged at least three (or perhaps four) times, by Sulla (Tac. Ann. 12.23; Gell. 13.14.4), by Caesar (Cic. Att. 13.20; Gell. 13.14.4; Dio Cass. 43.50.1), perhaps by Augustus (so Tac. Ann. 12.23, though the silence in the Res Gestae on this matter militates strongly against Tacitus's testimony), and by Claudius (Tac. Ann. 12.23; Gell. 13.14.7; CIL 6.31537a-d, 37023-37024; Pasqui 1909, 45; Mancini 1913, 68).

62 Kleiner 1990 identifies three arches depicted in Flavian artworks as the arches referred to by Dio: the

38 CARLOS F. NORENA

the Romans the consummate monumental expression of military victory and as such would have conformed well to the Flavian commemoration of the Judaean conquest. In addition, as noted above, Vespasian closed the Temple of Janus, an action that Orosius associates not with the extinction of civil war but with the conquest of Jerusalem in 70. Finally, we know from a casual reference in Pliny the Elder that Vespasian restored the Temple of Honos and Virtus near the Porta Capena (Plin. HN 35.120). That Vespasian chose to restore a joint monument to official honor and the military valor upon which that honor was based was an especially fitting gesture for an emperor whose own imperial rank depended upon martial accomplishments.

From all of this disparate evidence a picture begins to emerge of a Vespasianic Rome that was largely defined, at least in topographical and monumental terms, by the public celebra- tion of empire. That this celebration depended not on the conquest of new territory, but rather on the suppression of a provincial revolt, made little difference. The military ideology underpinning this celebration found topographical expression in the pomerial extension of 75, a deeply symbolic modification of Rome's urban landscape that represented in spatial terms the "enlargement" of the Roman empire under Flavian stewardship. The Flavian Am- phitheater was an even more emphatic assertion of military ideals, advertising in its dedica- tory inscriptions, which must have been numerous, that the massive structure had been built ex manubiis. The Temple of Janus in the Forum, closed in order to symbolize that the Roman world was everywhere pacified, was a constant reminder of the Flavians' military exploits. No less visible were the triumphal arches that surely towered above several key spots in the city. The Templum Pacis did not stand in opposition to all of these symbols of military suc- cess as an exhortation of "peace" in the modern, moral sense of the term. That would have struck a discordant note in Vespasian's Rome. Nor did it advertise the end of civil conflict through a commemoration of Vespasian's victory in the civil war of 68-69. This victory will have lost much of its resonance by the time the Templum Pacis was dedicated in 75, and in any case the slaughter of fellow Romans was not a suitable subject for memorialization. The contemporary message of the Templum Pacis was more traditional. Like the Flavian Amphi- theater, Vespasian's other major structure in the center of Rome, the Templum Pacis was a victory monument, a large-scale memorial to Roman imperialism in general and to the Flavian conquest of Judaea in particular.

We return, in conclusion, to the correspondence between the inauguration of the Templum Pacis in 75 (Dio Cass. 65.15. 1) and the proliferation of the Pax denarius issued that year (fig. 2). This correspondence between imperial monument and imperial coin type provides some further insights into the Templum Pacis itself and is also illuminating for the operation of imperial communications in first-century Rome.

The prominence of the Pax type in 75, I argue, represents an intentional, numismatic commemoration of the inauguration of the Templum Pacis. Earlier attempts to find such com- memoration have not been convincing. E. Bianco and P. V. Hill, for example, have both sug- gested that a reverse type depicting a heifer that appeared in 74 and 76 was intended, through its allusion to Myron's heifer, one of the most famous statues in the Templum Pacis, to cel- ebrate the completion and dedication of the complex in 75.63 But neither of these coins was

arch depicted on the spoils relief of the Arch of Titus; the arch labeled arcus ad Isis on the Haterii relief; and an arch shown on a sestertius of 71 (BMC 576). Kleiner's arguments have not found much support. The LTUR, for example, does not include a separate entry for an arch of

Vespasian. See discussion in Darwall-Smith 1996, 69-70.

63 Bianco 1968, 177; Hill 1989, 73. Heifer type: BMC 132, 176-178, 185-189. Myron's heifer: Plin. HN34.57; Proc. BG 4.2 1.

MEDIUM AND MESSAGE IN VESPASIAN'S TEMPLUM PACIS 39

minted in the year in which the Templum Pacis was inaugurated, and in any case to posit the representation of a single sculpture, however famous, as an adequate commemoration of an entire monumental complex is simply untenable. The more straightforward connection that I am proposing here between the Pax type and the Templum Pacis has recently been disputed by Darwall-Smith. He claims that the frequent representation of Pax on Vespasian's coinage "need not be connected with her temple,"64 but to discuss indiscriminately all of the Pax types minted between 69 and 79 is not helpful. Our focus, of course, should be on the Pax type of 75 (BMC 161-164 = RIC 90). On the relationship between this type and the Templum Pacis, Darwall-Smith writes, "she is one of several seated types, and the only reason for iden- tifying her, rather than any other type, is the date."65 But the quantitative analysis of Vespasian's coinage does give another reason for identifying this particular Pax with the Templum Pacis, and a strong one, for it is precisely the marked prominence of the type in 75-in strictly numerical terms-that establishes the connection. Nor should the heavy minting of the Pax denarius in 75 be seen as merely coincidental with the inauguration of the Templum Pacis. There is in fact additional evidence from Vespasian's aes coinage that provides a strong hint that the Pax type in 75 was specifically intended to commemorate that inauguration.

In his die study of sestertii from the extraordinary output of aes coinage in 71, C. M. Kraay identified three successive phases of output, each distinguished by emphasis on a dif- ferent theme.66 Kraay's study revealed that the Iudaea Capta type was the principal theme during the second phase of output, which fell in the period between May and July of 71. Outside of this phase, the type hardly appears. According to Kraay, this particular distribu- tion of output "creates the strong presumption that it was closely connected with the tri- umph of Vespasian and Titus celebrated at the end of June" in 71.67 This is an important finding. The joint triumph of Vespasian and Titus, recorded in such detail by the contemporary observer Josephus (BJ 7.123-157), and represented for posterity on the interior panels of the Arch of Titus, marked the definitive announcement of the new dynasty in Rome and was there- fore a pivotal moment in Vespasian's claim to legitimacy.68 If Kraay's chronology for the sestertii of 71 is correct, then what we have in the Iudaea Capta type of 71 is not only another example of an unambiguously topical reference on Vespasian's coinage but also a well-documented case of a specific type being issued in close conjunction with the very event it was meant to com- memorate. There appears to be a precedent on Vespasian's own coinage, then, for the targeted production of a specific type, and in light of this function of the Iudaea Capta type of 71 we may reasonably conclude that the Pax type of 75 was also intended to commemorate a key imperial ceremony, in this case the inauguration of the Templum Pacis. Indeed, the specific fluctuations in the relative frequency of the type make this connection a near certainty.69

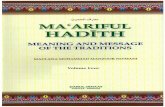

The reverse type of the coin in question depicts Pax, bare to the waist, seated and facing to the left, holding an olive branch extended in her right hand (fig. 3). It is the attribute of the olive branch that secures the identification of the figure as Pax. The fact that the numismatic commemoration of the Templum Pacis took the form of a representation of Pax, and not of

64 Darwall-Smith 1996, 61.

65 Darwall-Smith 1996, 63.

66 Kraay 1978. To establish a chronology Kraay (1978, 50) relied on the obverse legends of Vespasian's coins, of which he identified three main varieties.

67 Kraay 1978, 50.

68 Josephus on the triumph of 71: Beard 2003. Interior panels of the Arch of Titus: Pfanner 1983, 44-76.

69 It is perhaps worth recalling here that this observation pertains only to denarii and not to the other (less com- mon) denominations of the imperial coinage.

40 CARLOS F. NORENA

Fig. 3. Pax, bare to the waist, seated and facing to the left, holding a branch extended in her right hand (denarius, A.D. 75), RIC 90

(reverse) (reproduced courtesy of the a American Numismatic Society, New York,

accession number 1944.100.39932).

the monumental complex itself-an artistic option that was certainly available to the die en- gravers of the Roman mint-is also significant.70 Coarelli has identified this type as a repre- sentation of the cult statue of Pax, which was perhaps displayed in the central hall along the southeastern end of the central square (see fig. 1), but this identification is not guaranteed by the appearance of the type in 75, especially if one interprets a vague line in Statius, as Coarelli himself does, to mean that it was Domitian and not Vespasian who dedicated the cult statue.7' It is more likely that this representation of Pax, like so many reverse types on the imperial coinage, was a personified abstraction.72 In view of this, I would like to suggest that for the numismatic commemoration of the Templum Pacis, it was not the complex itself or even the goddess to whom it was dedicated that mattered but rather the very idea of pax. That was the central message of the Templum Pacis.73 It is in this context that the multiplicity of names for the complex becomes relevant. As we have seen, different authors could refer to the complex using different terms-templum, forum, and aedes in Latin and, in Greek, temenos and hieron- but what unified all of these designations and identified the complex was the subjective genitive Pacis, or Etplvls.74 Note that Pliny the Elder can even refer to the artistic holdings of the Templum Pacis simply as Pacis opera, "the artworks of Peace" (HN 36.27). As these testimo- nia suggest, it was really the concept of pax/E Lprvfl, and not the class of structure in which Peace was honored (on which ancient authors do not seem to agree), that captured the imagi- nation of both contemporaries and later observers. And so it was with the coin type issued in conjunction with the inauguration of the Templum Pacis. Eschewing an image of the monu- mental complex as a whole, or of a part of the complex, or even of the cult statue, the mint- ing authorities chose to commemorate the new Templum Pacis by disseminating coins bear- ing a personification of pax itself, the core ideal of Vespasian's contribution to Rome's impe- rial Volksbauten.75

70 See the plates in Hill 1989 for the numismatic repre- sentation of Roman buildings.

71 Coarelli 1999, 69. For the line from Statius (Silv. 4.3.17), see above n. 4.

72 In an earlier study I estimated that 55 percent of all reverse types on imperial denarii minted between 69 and 235 were personifications (Noreiia 2001, 153-155, with table 2).

73 The numismatic representation of an abstraction as a vehicle to commemorate an imperial monument was not common, but a coin type produced under Tiberius could be interpreted as a precedent for this sort of commemo- ration. A dupondius issued in A.D. 22 (RIC 12 43) depicts on the obverse a bust of the personified abstraction Pietas, a very rare obverse type that is probably best ex-

plained as a means to publicize the vowing of the Ara Pietatis in that year (CIL 6.526 = ILS 202; cf. Tac. Ann. 3.64). Note also an obverse type depicting a bust of Apollo minted at some point between 29 and 27 B.C. (RIC J2 271-272), perhaps intended to celebrate the dedica- tion of the Palatine temple of Apollo in 28 (Dio Cass. 53.1.3).

74 Symmachus, by contrast, calls the complex Forum Vespasiani (Ep. 10.78). Dio can also refer to the entire complex with a single name, EpTivalov (73.24.1).

75 The fact that the coin type commemorating the inau- guration of the Templum Pacis did not represent a temple proper (aedes) should not necessarily be taken as indi- rect evidence that no such temple ever existed (as im- plied by La Rocca 2001, 202-203); it simply reflects the importance attached to the abstract idea of pax.

MEDIUM AND MESSAGE IN VESPASIAN'S TEMPLUM PACIS 41

Finally, the correspondence for which I am arguing here between the prominence of the Pax type on denarii and the dedication of the Templum Pacis in 75, to which should be added the enlargement of the pomerium in the same year, has additional implications for our under- standing of Roman imperial media and communications. In particular, the heavy minting of a specific coin type, the formal inauguration of an imperial monument, and the extension of Rome's religious and civic boundary in 75-all of which, in their own ways, commemorated the pacification of Judaea-together point to an unusually high degree of coordination among distinct public actions and across different media of imperial publicity. And if these actions were indeed coordinated, as they must have been, then they must also have been intentional and the result of a series of conscious decisions. It should also be clear that complex coordi- nation of this sort, involving separate "departments" of the imperial bureaucracy, could only be brought about if the decisions that led to it were highly centralized. Centralized decision- making is not surprising in an absolute monarchy, of course, but is perhaps unexpected in this context: did those in the highest circles of Roman imperial government, including the emperor himself, really care about coin types and buildings and religious ceremonies?

The evidence presented in this paper supports the proposition that coin types could be topical and chosen with a view to strengthening the impact and increasing the dissemination of messages communicated in other imperial media.76 It also indicates that, in certain cases at least, the relative frequency with which specific types were minted was the result of a con- scious decision. In the absence of mint records and written testimony on the operation of the Roman mint, we cannot know for certain whether decisions on coin design and decisions on mint output were separate or linked, but the evidence discussed here suggests that these de- cisions could indeed be linked.77 In this particular case, in fact, it seems that the decisions (1) to depict Pax on denarii of 75 and (2) to issue this type in very large numbers were made in unison with (3) the decision to dedicate the Templum Pacis and perhaps in unison with (4) the decision to extend the pomerium.78 It is reasonable to conclude that the Roman mint was not an autonomous branch of imperial government operating in isolation.

The unity of decision-making implied by the coordinated public pronouncements of the regime in 75 provides an important insight into the essence of imperial power. It demon- strates that different organs of imperial government could work in harmony to produce a single, coherent program of positive publicity for the reigning emperor. And positive public- ity was a necessary component of political stability. For Vespasian, founder of an upstart dy- nasty in serious need of legitimating credentials, the "enlargement" of the Roman empire stood as an unimpeachable claim to legitimacy, and the successful coordination of imperial media in 75 assured that the core message of the Templum Pacis, the Flavian conquest of Judaea, would be loud and clear.

76 The mechanics behind the selection of coin types, their intent, and their overall impact on users are all complex questions that continue to excite debate. For a recent and thorough overview of these (and related) debates, see Wolters 1999, 255-399.

77 A well-known reference in Statius implies that the a rationibus ("secretary for accounts") was responsible for the supply of bullion to the mint and the volume of coin-

age produced (Silv. 3.104-105), but this is not the same thing as responsibility for the selection of types. In other words, there is no explicit literary evidence that deci- sions on output and on design were linked.

78 A similar unity of decision-making would have been necessary for the issuing of the Iudaea Capta coin type in conjunction with the triumph of 71.

42 CARLOS F. NORENA

Bibliography

ABBREVIATIONS

BMC Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum (London 1923-1962). CIL Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, 17 vols. (Berlin 1863-). ILS Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae (Berlin 1892-1916). LTUR Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae, 6 vols., ed. E. M. Steinby (Rome 1993-2000). PIR2 Prosopographia Imperii Romani, 2nd ed., ed. E. Groag et al. (Berlin 1933-). RIC Roman Imperial Coinage (London 1923-). TLL Thesaurus Linguae Latinae (Leipzig 1900-).

WORKS CITED

Alf6ldi, A., "Eine Bauinschrift aus dem Colosseum," Zeitschrift fur Papyrologie und Epigraphik 109 (1995) 195-226.

Anderson, J. C., "Domitian, the Argiletum and the Temple of Peace," American Journal of Archaeology 86 (1982) 101-110. -, The Historical Topography of the Imperial Fora (Brussels 1984). Collection Latomus 182.

Beard, M., "The Triumph of Flavius Josephus," in Boyle and Dominik 2003, 543-558. Bianco, E., "Indirizzi programmatici e propagandistici nella monetazione di Vespasiano," Rivista italiana

di numismatica 70 (1968) 145-224. Boyle, A. J., and W Dominik, eds., Flavian Rome: Culture, Image, Text (Leiden 2003). Buttrey, T. V., "Vespasian as Moneyer," Numismatic Chronicle 12 (1972) 89-109.

, Documentary Evidencefor the Chronology of the Flavian Titulature (Meisenheim am Glan 1980). Carradice, I., "Towards a New Introduction to the Flavian Coinage," in Modus Operandi: Essays in

Honour of Geoffrey Rickman, ed. M. Austin et al. (London 1998) 93-117. Carettoni, G., A. M. Colini, L. Cozza, and G. Gatti, La pianta marmorea di Roma antica (Forma Urbis

Romae) (Rome 1960). Castagnoli, F., "Politica urbanistica di Vespasiano in Roma," in Atti del congresso internazionale di

studi vespasianei, ed. B. Riposati (Rieti 1981) 261-275. Coarelli, F., "Pax, Templum," LTUR 4 (1999) 67-70. Colini, A. M., "Forum Pacis," Bullettino della CommissioneArcheologica del Comune diRoma 65 (1937)

7-40. Darwall-Smith, R. H., Emperors and Architecture: A Study of Flavian Rome (Brussels 1996). Collection

Latomus 23 1. Duncan-Jones, R., Money and Government in the Roman Empire (Cambridge 1994). Griffin, M., "The Flavians," in Cambridge Ancient History, 2nd ed., ed. A. K. Bowman et al., vol. 11

(Cambridge 2000) 1-83. Gros, P., "La 'militarisation' de l'urbanisme trajanien ' la lumiere des recherches recentes sur le Forum

Traiani," in Trajano emperador de Roma, ed. J. Gonzalez (Rome 2000) 227-249. Gruen, E., "Augustus and the Ideology of War and Peace, " in The Age ofAugustus: An Interdisciplinary

Conference Held at Brown University April 30-May 2, 1982, ed. R. Winkes (Louvain 1985) 51-72. ,"The Foreign Policy of Augustus," in Cambridge Ancient History, 2nd ed., ed. A. K. Bowman et

al., vol. 10 (Cambridge 1996) 148-197. Gunderson, E., "The Flavian Amphitheatre: All the World as Stage," in Boyle and Dominik 2003, 637-

658. Gurval, R., Actium and Augustus: The Politics and Emotions of Civil War (Ann Arbor 1995). Hill, P. V., The Monuments of Ancient Rome as Coin Types (London 1989). Hurlet, F., "La Lex de imperio Vespasiani et la legitimite augusteenne," Latomus 52 (1993) 261-280. Isager, J., Pliny on Art and Society: The Elder Pliny's Chapters on the History of Art (Odense 1991).

MEDIUM AND MESSAGE IN VESPASIAN'S TEMPLUM PACIS 43

Jal, P., "Pax civilis-Concordia," Revue des etudes latines 39 (1961) 210-231. Kleiner, F. S., "The Arches of Vespasian in Rome," Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archdologischen Instituts,

Romische Abteilung 97 (1990) 127-136. Kraay, C. M., "The Bronze Coinage of Vespasian: Classification and Attribution," in Scripta Nummaria

Romana: Essays Presented to Humphrey Sutherland, ed. R. A. G. Carson and C. M. Kraay (London 1978) 47-57.

Kuttner, A., Dynasty and Empire in the Age of Augustus: The Case of the Boscoreale Cups (Berkeley 1995).

,"Culture and History at Pompey's Museum," Transactions of the American PhilologicalAssocia- tion 129 (1999) 343-373.

La Rocca, E., "La nuova immagine dei fori Imperiali: Appunti in margine agli scavi," Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archdologischen Instituts, Romische Abteilung 108 (2001) 171-213.

Levick, B., Vespasian (New York 1999). Lynch, K., The Image of the City (Cambridge, Mass. 1960). Mancini, G., "II. Roma," Notizie degli scavi (1913) 67-71. Mattern, S., Rome and the Enemy: Imperial Strategy in the Principate (Berkeley 1999). Nash, E., Pictorial Dictionary of Ancient Rome, 2nd ed., 2 vols. (London 1968). Norenia, C. F., "The Communication of the Emperor's Virtues," Journal of Roman Studies 91 (2001)

146-168. Packer, J., "Plurima et Amplissima Opera: Parsing Flavian Rome," in Boyle and Dominik 2003, 167-

198. Pasqui, A., "II. Roma," Notizie degli scavi (1909) 37-46. Pera, R., "Cultura e politica di Vespasiano riflesse nelle sue monete, " in Atti del congresso internazionale

di studi vespasianei, ed. B. Riposati (Rieti 1981) 505-514. Pick, B., "Zur Titulatur der Flavier I: Der Imperatortitel des Titus," Zeitschrift fur Numismatik 13

(1885) 190-238. Pfanner, M., Der Titusbogen (Mainz 1983). Pollitt, J. J., "The Impact of Greek Art on Rome," Transactions of the American Philological Association

108 (1978) 155-174. Ramage, E., "Denigration of Predecessor under Claudius, Galba and Vespasian," Historia 32 (1983)

200-214. Richardson, jr., L., A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (Baltimore 1992). Rodriguez Almeida, E., Forma urbis marmorea: aggiornamento generale 1980 (Rome 1981). Romanelli, P., "II. Roma," Notizie degli scavi (1933) 240-251. Rosenberger, V., Bella et expeditiones. Die antike Terminologie der Kriege Roms (Stuttgart 1992). Ruysschaert, J., "Essai d'interpretation synthetique de l'arc de Constantin," Atti della Pontificia

Accademia Romana di Archeologia: Rendiconti 35 (1962-1963) 79-100. Ruyt, C. De, Macellum: Marche' alimentaire des Romains (Louvain 1983). Santangeli Valenzani, R., "Pax, Templum," LTUR 5 (1999) 285. Wallace-Hadrill, A., Augustan Rome (London 1993). Weinstock, S., "Pax and the 'Ara Pacis'," Journal of Roman Studies 50 (1960) 44-58. Wellesley, K., The Year of the Four Emperors, 3rd ed. (New York 2000); originally published as The

Long Year A.D. 69 (Boulder, Col. 1976). Wolters, R., Nummi Signati: Untersuchungen zur romischen Miinzprigung und Geldwirtschaft (Munich

1999). Woolf, G., "Roman Peace," in War and Society in the Roman World, ed. J. Rich and G. Shipley (New

York 1993) 171-194. Zanker, P., The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus, trans. A. Shapiro (Ann Arbor 1988; German

orig. 1987). , Der Kaiser haut furs Volk (Dusseldorf 1997).