Medical and psychosocial predictors of mechanical circulatory support device implantation and...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Medical and psychosocial predictors of mechanical circulatory support device implantation and...

Medical and psychosocial predictors of mechanicalcirculatory support device implantation and competingoutcomes in the Waiting for a New Heart Study

Heike Spaderna, PhD,a Gerdi Weidner, PhD,b Karl-Christian Koch, MD,c

Ingo Kaczmarek, MD,d Florian M. Wagner, MD,e and Jacqueline M.A. Smits, MD, PhD,f

for the Waiting for a New Heart Study Group

From the aDepartment of Psychology, Johannes Gutenberg-University, Mainz, Germany; the bDepartment of Biology, San Francisco StateUniversity, San Francisco, California; the cDepartment of Cardiology, University Hospital Aachen, Aachen, Germany; the dDepartment ofCardiac Surgery, University Hospital Munich-Großhadern, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Munich, Germany; the eUniversity HeartCenter at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany; and fEurotransplant International Foundation,Leiden, The Netherlands.

BACKGROUND: Medical and psychosocial factors are related to 1-year outcomes in the Waiting for a NewHeart Study. With increased use of mechanical circulatory support devices (MCSD) over the course of thestudy, we can now evaluate these variables as predictors of MCSD in an extended follow-up.METHODS: Analyses focused on 313 MCSD-free patients (82% men; aged 53 ! 11 years) newly listed forheart transplantation (HTx). Variables assessed at time of listing included psychosocial risk (depression, socialisolation), quality of life, waiting list stress, and medical risk (Heart Failure Survival Score, pulmonary capillarywedge pressure). Cumulative incidence functions and cause-specific Cox models examined the association ofmedical and psychosocial risk (low: non-depressed and socially integrated; medium: depressed or sociallyisolated; high: depressed and socially isolated) with time until MCSD, considering covariates and competingoutcomes (death, high-urgency transplantation [HU-HTx], elective HTx, and delisting due to clinicalimprovement or deterioration).RESULTS: Psychosocial risk groups were comparable regarding demographics, medical parameters,and quality of life, but differed in waiting list-related stressors. During follow-up (median, 326; range,5–1,849 days), 26 patients received MCSD, 53 died, 144 underwent HTx (103 in HU status), and 53were delisted (15 deteriorated, 31 improved). Non-depressed and socially integrated patients did notrequire MCSD. Controlling for medical risk, psychosocial risk significantly contributed to MCSD,HU-HTx, and improvement; medical risk and female gender predicted death (p " 0.05).CONCLUSIONS: Psychosocial risk at time of listing affects the prognosis of HTx candidates beyondmedical risk. Psychosocial interventions may help to stabilize patients’ health.J Heart Lung Transplant 2012;31:16–26© 2012 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. All rights reserved.

KEY WORDS:heart failure;mechanical circulatorysupport;Heart Failure SurvivalScore;psychosocial risk;waiting list

Donor heart shortage remains a major problem in hearttransplantation (HTx) medicine. Mechanical circulatory sup-port devices (MCSDs) have become an important life-savingoption. According to the Interagency Registry for Mechani-cally Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) report,bridge to transplant constitutes the most common device strat-egy (43.3%),1 with progressive decline (INTERMACS level 2)being the most prevalent indication.2

Reprint requests: Heike Spaderna, PhD, Psychologisches Institut, Jo-hannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Binger Str. 14-16, 55099 Mainz,Germany. Telephone: 0049-6131-39-39166. Fax: 0049-6131-39-39154.

E-mail address: [email protected]

http://www.jhltonline.org

1053-2498/$ -see front matter © 2012 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.healun.2011.07.018

Information on medical and psychosocial patient character-istics associated with need for MCSD implantation is scarce.We previously showed that the presence of psychosocial risk(depression, social isolation) at time of listing reduced chancesfor clinical improvement in the following 12 months.3,4

Although MCSD implantations were uncommon in Europein 2005, when the Waiting for a New Heart Study started,5 thenumber of patients having received an MCSD during thefollow-up has increased, allowing us to evaluate MSCD as anadditional outcome. The aims of the present report were to:

1. compare demographic and medical characteristics, waitinglist–related stressors, and quality of life among 3 psychos-ocial risk groups (low: low depression and socially inte-grated; medium: depressed or socially isolated; high: de-pressed and socially isolated) at time of listing; and

2. evaluate the association of medical and psychosocial riskwith time until MCSD implantation and the competingwaiting list outcomes of death on the waiting list, del-isting due to clinical deterioration, high urgency (HU)HTx, elective HTx, and delisting due to improvementduring an extended follow-up.

Methods

The study was approved by local ethics committees and conductedin accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Procedure and participants

The Waiting for a New Heart Study is an ongoing, prospective,multi-site observational study of patients newly listed for HTx in17 hospitals (16 in Germany, 1 in Austria; Appendix). The primaryaim is to identify psychosocial and behavioral predictors of pre-transplant outcomes. For the present report, MCSD implantationsand competing waiting list outcomes were considered until March31, 2010. The study procedures have been described previ-ously.3,6,7

Briefly, between April 2005 and December 2006, written in-formed consent was obtained from consecutive patients who werenewly registered on the waiting list. Exclusion criteria were age "18 years, listing for combined heart-lung Tx, re-Tx, not beingfluent in German, and being too severely ill to participate, asdetermined by the local physician. Of 479 newly listed patients380 met inclusion criteria and were invited to participate.6 Ques-tionnaires were mailed to 340 patients who consented and com-pleted by 318 patients (2 died and 2 underwent Tx before com-pleting the questionnaire, 8 withdrew participation, and 10 did notreturn the questionnaire and could not be contacted). Comparisonsof non-participants with participating patients have been reportedpreviously.6,7

Measures

Eurotransplant provided medical information at time of listing(Table 1). This included anthropometric variables, medications,creatinine, cardiac index, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure(PCWP), and parameters to calculate the Heart Failure SurvivalScore (HFSS; Table 1),8 which has acceptable prognostic perfor-mance in the era of !-blockers,4,9 implantable cardioverter defi-

brillators (ICD), and resynchronization therapy.10 Demographicvariables and in/outpatient status were assessed via questionnaire.

Psychosocial risk was based on assessments of depressivesymptoms measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale(HADS-D), with scores "9 suggesting clinical depression,11 andsocial isolation as indicated by low network size, defined as con-tact with " 4 persons/month.12 Thus, high risk was defined bydepression and social isolation, medium risk by depression orsocial isolation, and low risk by neither.3

Heart failure and waiting list–related stressors were assessed in4 domains using a modified version6 of the German pre-HTxquestionnaire (Jaeger, 1997, unpublished manuscript, based onJalowiec et al13): bodily/medical stressors, 16 items (eg, “breath-lessness,” “limitation of fluid intake”); family/social stressors, 13items; work/finances, 5 items; and emotional stressors, 16 items(for individual items see Figure 1). Patients were asked how muchthey felt burdened by each stressor. Response options ranged from0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“very much”). The additional option “notapplicable” (if the patient did not experience the respective stressorduring the past month) was recoded with 0.6

Quality of life was measured by the Minnesota Living withHeart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ), which yields 3 summedscores: total, physical, and emotional quality of life.14

Outcomes included MCSD implantation as bridge to transplantand waiting list outcomes without prior MCSD implantation (Fig-ure 2). Date of MCSD implantations and type of device wereobtained from hospitals. Other changes in waiting list outcomeswere provided by Eurotransplant, and defined as death on thewaiting list, high-urgency (HU) HTx (ie, HTx while upgraded toHU status), elective HTx (ie, HTx while not in HU status), anddelisting due to clinical deterioration or improvement. The term“HU-status” is temporarily applied to patients in intensive careunits with cardiac index " 2.2 liters/m2/min and mixed venousoxygen saturation " 55%, while receiving inotropic therapy for atleast 48 hours and beginning secondary organ failure. Patients onMCSD are not eligible for HU status in Germany as long as theydo not suffer from device-related complications (eg, recurrentembolism, infection). Thus, a patient receiving MSCD supportwho was listed for HU because of MCSD-related complicationswas not considered as HU and vice versa.

Data analysesAnalyses were conducted using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSSInc, Chicago, IL) and R 2.12.0 software, including thepackage cmprsk 2.2-1. Missing data in medical baselineparameters ranged from 0.6% (heart rate) to 24.8% (peakoxygen consumption), the latter largely due to inpatientstatus.3,7 The 5 patients with MCSD devices at time oflisting were excluded from the present analyses. The 3psychosocial risk groups were compared by demographic,medical, and psychosocial characteristics at time of listingusing chi-square for categoric variables and single-factoranalysis of variance for continuous variables. The Welchcorrection was used if homogeneity of variance was absent.Statistically significant overall effects were examined applyingHochberg’s GT2 (unequal sample sizes, equal variances) orGames-Howell (unequal variances) post hoc tests. To accountfor multiple testing when evaluating group differences withregard to the 50 waiting list–related stressors, we conducted 4multivariate analyses of variance, 1 for each domain.

17Spaderna et al. Medical and Psychosocial Predictors of MCSD

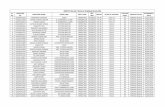

Table 1 Demographic and Medical Characteristics of Psychosocial Risk Groups at Time of Listing for HTx

Variablesa No.

Psychosocial risk

p-valueLow (n # 46) Medium (n # 231) High (n # 36)

DemographicsAge, years 51.4 (12.6) 52.9 (10.9) 55.9 (10.7) 0.188Women, n (%) 10 (21.7) 43 (18.6) 5 (13.9) 0.661Living alone, n (%) 1 (2.2) 42 (18.2) 10 (27.8) 0.006Married, n (%) 37 (80.4) 150 (64.9) 22 (61.1) 0.093Education # 9 years, n (%) 25 (54.3) 148 (64.1) 24 (66.7) 0.407Currently working, n (%) 3 (6.5) 21 (9.1) 2 (5.6) 0.692Inpatient, n (%) 14 (30.4) 63 (27.3) 9 (25.0) 0.853BMI category, n (%) 0.691

Underweight (" 18.5 kg/m2)

0 (0.0) 4 (1.7) 2 (5.6)

Normal weight (18.5 - 24.9kg/m2)

20 (43.5) 90 (39.0) 15 (41.7)

Overweight (25.0 - 29.9 kg/m2)

19 (41.3) 101 (43.7) 14 (38.9)

Obese ($# 30.0 kg/m2) 7 (15.2) 36 (15.6) 5 (13.9)Medical characteristics

HFSS 8.0 (0.8) 7.8 (0.9) 7.7 (1.1) 0.210MABP, mm Hgb 78.5 (10.6) 77.9 (11.9) 74.8 (13.3) 0.314LVEF, %b 24.7 (9.8) 23.6 (10.1) 21.4 (12.5) 0.355Heart rate, beats/minb 77.8 (18.8) 76.9 (15.8) 78.9 (18.3) 0.784Peak VO2, ml/m/kgb 11.1 (2.8) 11.1 (2.6) 11.0 (2.1) 0.999Sodium, mmol/literb 137.7 (3.3) 137.1 (4.2) 137.1 (4.0) 0.617PCWP, mm Hg 19.4 (9.1) 20.3 (8.2) 21.4 (9.0) 0.576Creatinine, mg/dl 1.4 (0.4) 1.4 (0.5) 1.4 (0.5) 0.980Cardiac index, liter/min/m2 2.1 (0.9) 2.0 (0.5) 2.0 (0.5) 0.570QRS $ 0.12 sec, n (%)b 26 (60.5) 121 (55.5) 14 (40.0) 0.160Ischemic diagnosis, n (%)b 10 (21.7) 90 (39.0) 18 (50.0) 0.024NYHA class, n (%) 0.472

II, II-III, III 20 (43.5) 92 (40.2) 9 (25.0)III-IV 16 (34.8) 81 (35.4) 16 (44.4)IV 10 (21.7) 56 (24.5) 11 (30.6)

Comorbidities, n (%)Atrial fibrillation 253 9 (19.6) 32 (13.9) 7 (19.4) 0.345Mitral valve regurgitation 221 15 (32.6) 68 (29.4) 7 (19.4) 0.469Peripheral artery disease 259 3 (6.5) 8 (3.5) 0 (0.0) 0.310Diabetes mellitus 275 10 (21.7) 59 (25.5) 6 (16.7) 0.654Previous heart surgery 285 10 (21.7) 67 (29.0) 13 (36.1) 0.192Dialysis/hemofiltration 287 0 (0.0) 3 (1.3) 0 (0.0) 0.596ICD 274 26 (56.5) 131 (56.7) 16 (44.4) 0.785

Medication, n (%)Catecholamines 305 7 (15.2) 34 (14.7) 8 (22.2) 0.563!-Blockers 308 41 (89.1) 198 (85.7) 29 (80.6) 0.453ACE inhibitors 307 38 (82.6) 170 (73.6) 26 (72.2) 0.495Aldosterone antagonists 308 27 (58.7) 156 (67.5) 22 (61.1) 0.305Diuretics 308 41 (89.1) 207 (89.6) 28 (77.8) 0.041Digitalis 309 22 (47.8) 117 (50.6) 15 (41.7) 0.522Antidepressants 208 1 (2.4) 16 (7.8) 5 (14.7) 0.148

Psychosocial variablesDepression (0–21)c 5.3 (2.1) 7.5 (3.9) 11.9 (2.7) "0.0001Depressed (HADS-D "9), n (%) 0 (0.0) 85 (36.8) 36 (100.0) "0.0001Network sizec 17.5 (5.5) 7.2 (4.8) 2.4 (0.8) "0.0001Network size, n (%) "0.0001

"4 0 (0.0) 30 (13.0) 36 (100.0)4–10 0 (0.0) 185 (80.1) 0 (0.0)$10 46 (100.0) 16 (6.9) 0 (0.0)

MLHFQ (0–105)d 61.6 (19.0) 61.6 (18.9) 63.7 (16.8) 0.814

Continued on page 19.

18 The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation, Vol 31, No 1, January 2012

Figure 1 Heart failure and waiting list–related stressors in patients with low, medium, and high psychosocial risk. Bars denote itemmeans. Em, emotional stressors; F/S, family/social stressors; HTx, heart transplantation; W/F, stressors related to work/finances.*Significant group differences in univariate analysis of variance (p " 0.05). ‡Marginal group differences in univariate analysis ofvariance (p " 0.10).

Table 1 Continued from page 18.

Variablesa No.

Psychosocial risk

p-valueLow (n # 46) Medium (n # 231) High (n # 36)

MLHFQ physical (0–40)d 28.0 (8.1) 28.4 (7.9) 28.6 (7.8) 0.938MLHFQ emotional (0–25)d 12.1 (5.9) 12.7 (6.6) 14.9 (6.3) 0.108

ACE, Angiotensin converting enzyme, AT1 receptor blockers; BMI, body mass index; HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Depression score;HFSS, Heart Failure Survival Score; HTx, heart transplantation; ICD, intracardiac cardioverter-defibrillator; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MABP,mean arterial blood pressure; MLHFQ, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCWP, pulmonary capillarywedge pressure; PeakVO2, peak oxygen consumption.

aUnless otherwise indicated, data are presented as mean (standard deviation).bIncluded in the HFSS.cDepression accounted for only 1.4% of the variability in network size (r313 # %0.12, p # .030).dHigher scores denote lower quality of life.

19Spaderna et al. Medical and Psychosocial Predictors of MCSD

The association of medical characteristics and psychos-ocial risk group with waiting list outcomes was analyzedwithin a competing risks approach (Figure 1), consideringthe mutually exclusive outcomes MCSD implantation,death on the waiting list, HU-HTx, elective HTx, and del-isting due to clinical improvement and deterioration as com-peting events, whichever occurred first.15 Thus, the occur-rence of one event (eg, MCSD implantation), would alterthe probability of other events (eg, death). We plotted cu-mulative incidence functions for all outcome types (ie, theproportion of patients having experienced an outcome overthe course of time) and report sub-distribution estimates foreach outcome for the total sample and by psychosocial riskgroup.16

In addition, cause-specific Cox proportional hazard mod-els were run to evaluate the association of risk factors withMCSD and each of the competing outcomes,17 both inunivariate and multivariate analyses. For the latter, psycho-social risk was entered in the third step after controlling forage and sex (step 1) and medical predictors significantlyassociated with any of the outcomes (step 2). Because of thelow event rate of delisting due to clinical deterioration, thisoutcome was not analyzed in multivariate models. Modelswere rerun omitting all statistically non-significant variables(p $ 0.30) to avert model overfit. The overall contributionof psychosocial risk group was determined via reductions ofthe %2 log likelihood, expressed as change of chi-square.Group comparisons were accomplished with “low psycho-social risk” as reference group. Statistical tests were 2-tailedwith significance level at p " 0.05.

Results

Comparison of psychosocial risk groups at time oflisting

There were 36 (11.5%) patients with high psychosocial risk,46 (14.7%) with low psychosocial risk and 231 were cate-gorized as medium psychosocial risk (73.8%). The 3 groups

were generally similar in baseline medical risk, medication,and quality of life (Table 1), but experienced specific wait-ing list-related stressors according to their risk group. Sig-nificant multivariate effects of psychosocial risk group wereobtained for stressors in the domains family/social (Wilks’lambda # 0.78, F26, 586 # 3.01, p " 0.001), work/finances(Wilks’ lambda # 0.93, F10, 612 # 2.15, p # 0.019), andemotional stressors (Wilks’ lambda # 0.85, F32, 582 # 1.58,p # 0.023). Mean values of single stressors by psychosocialrisk group and specific group differences according to posthoc tests are displayed in Figure 2. Psychosocial risk groupsdid not differ in bodily/medical stressors (Wilks’ lambda #0.90, F32, 564 " 1, p # 0.484, data not shown).

Waiting list outcomes

By March 31, 2010, 26 patients (2 female) received aMCSD (14 left ventricular assist devices [12 continuous-flow]; 1 right ventricular assist device; 7 biventricular assistdevices, 4 total artificial hearts). Cumulative incidences aredisplayed in Figure 3. Thirty-seven patients were still wait-ing for a transplant without MCSD.

Univariate analyses

Table 2 reports medical risk factors and their associationwith outcomes. A worse HFSS was related to a shorter timeuntil MCSD, death, and HU-HTx, and a longer time untildelisting due to improvement (p " 0.05). Similarly, higherPCWP was associated with deterioration as indicated byMCSD, death, or HU-HTx (p " 0.05). Psychosocial riskgroup was also significantly associated with time untilMCSD (& chi-square [df 2] # 8.28, p # 0.016), delistingdue to improvement (& chi-square [df 2] # 9.12, p #0.010), and HU-HTx (& chi-square [df 2] # 9.25, p #0.010). The cumulative incidence of MCSD was 0% with

Figure 2 Competing study endpoints. HTx, heart transplanta-tion; MCSD, mechanical circulatory support device.

Figure 3 Cumulative incidence functions for the competingoutcomes mechanical circulatory support device (MCSD) implan-tation, death, high urgency heart transplantation (HTx), electivetransplantation, delisting due to clinical improvement, delistingdue to clinical deterioration, and delisting due to other reasons(N # 313).

20 The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation, Vol 31, No 1, January 2012

low psychosocial risk, but 10% and 11% in the medium andhigh groups (Figure 4). Cumulative incidence of improve-ment was 22% for low psychosocial risk compared with 8%and 6% in the other groups. Patients with low and high risk

had higher cumulative incidences of HU-HTx (46% and44%) than the medium risk group (29%; Table 2).

Because of the low event numbers in the high psychos-ocial risk group (4 MCSDs, 6 deaths, 2 delistings due to

Figure 4 Cumulative incidence functions, stratified by psychosocial risk group (low, medium, high), for the competing outcomesmechanical circulatory support device (MCSD) implantation, death, high-urgency heart transplantation (HTx), elective transplantation,delisting due to clinical improvement, and delisting due to clinical deterioration.

Table 2 Univariate Predictors of Mechanical Circulatory Support Device Implantation and Competing Waiting List Outcomes

PredictorMCSD (26 events) Death (53 events)

HU-HTx (103events) E-HTx (41 events)

Improvement (31events)

Deterioration (15events)

HR (95% CI) HR (95% CI) HR (95% CI) HR (95% CI) HR (95% CI) HR (95% CI)

Age 1.01 (0.97–1.06) 0.99 (0.96–1.02) 0.99 (0.97–1.01) 1.00 (0.97–1.03) 0.97 (0.94–1.00) 1.05 (0.98–1.12)Female sex 0.47 (0.11–2.00) 2.34 (1.30–4.21)b 0.92 (0.54–1.56) 1.64 (0.81–3.36) 0.85 (0.30–2.42) 2.02 (0.64–6.37)Inpatient 2.34 (0.91–6.04) 1.26 (0.56–2.81) 5.53 (3.71–8.23)b 3.77 (1.95–7.29)b 0.99 (0.30–3.27) 2.25 (0.63–8.01)HFSS 0.55 (0.33–0.89)b 0.58 (0.42–0.81)b 0.71 (0.57–0.90)b 0.95 (0.67–1.34) 1.54 (1.09–2.18)b 0.83 (0.46–1.49)PCWP 1.06 (1.01–1.11)b 1.05 (1.02–1.09)b 1.03 (1.01–1.06)b 0.98 (0.95–1.02) 1.03 (0.99–1.07) 0.99 (0.93–1.05)Cardiac index 0.47 (0.19–1.15) 0.55 (0.30–1.01) 0.47 (0.31–0.73)b 1.20 (0.76–1.89) 1.57 (1.04–2.39)b 1.54 (0.80–3.00)Creatinine 1.35 (0.55–3.32) 2.62 (1.62–4.26)b 1.34 (0.90–1.99) 1.47 (0.77–2.80) 0.67 (0.24–1.91) 2.02 (0.74–5.53)Psychosocial

riska

Low [Ref group] [Ref group] [Ref group] [Ref group] [Ref group] [Ref group]Medium NCc 2.21 (0.69–7.13) 0.53 (0.32–0.86)b 0.98 (0.38–2.52) 0.27 (0.13–0.59)b 1.72 (0.22–13.26)High NCc 3.07 (0.76–12.29) 1.02 (0.53–1.96) 1.42 (0.41–4.91) 0.34 (0.07–1.55) 3.20 (0.29–35.45)

CI, confidence interval; E-HTx, elective heart transplantation; HFSS, Heart Failure Survival Score; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; HR,hazard ratio; HTx, heart transplantation; HU, high urgency; MCSD, mechanical circulatory support; NC, not computable

aSignificant overall effects were obtained for MCSD, HU-HTx, and delisting due to improvement (see text for details).bValues were significant (p " 0.05).cBecause none of the patients with low psychosocial risk needed a MCSD, computation of HRs with low psychosocial risk as reference group was not

feasible.

21Spaderna et al. Medical and Psychosocial Predictors of MCSD

Table 3 Multivariate Cox Models Evaluating Time Until Mechanical Circulatory Support Device Implantation and CompetingOutcomes

Outcome Events HR (95% CI) &Chi-square (df) p-value

MCSD 261. Age 1.00 (0.96–1.05) 1.54 (2) 0.463

Female sex 0.55 (0.13–2.39)2. Inpatient 1.78 (0.65–4.85) 11.63 (5) 0.040

HFSS 0.66 (0.40–1.10)PCWP 1.04 (0.98–1.09)Cardiac index 0.63 (0.25–1.60)Creatinine 1.18 (0.44–3.17)

3. Psychosocial riska 7.30 (2) 0.026Low [Ref group]Medium NCHigh NC

Death 531. Age 0.98 (0.95–1.01) 7.16 (2) 0.028

Female sex 3.03 (1.62–5.68)b

2. Inpatient 1.06 (0.46–2.45) 33.95 (5) "0.0001HFSS 0.64 (0.45–0.89)b

PCWP 1.04 (1.01–1.08)c

Cardiac index 0.86 (0.47–1.58)Creatinine 2.84 (1.71–4.73)d

3. Psychosocial risk 2.06 (2) 0.356Low [Ref group]Medium 1.76 (0.54–5.75)High 2.69 (0.66–10.95)

High urgency HTx 1031. Age 0.98 (0.96–0.99)b 1.76 (2) 0.415

Female sex 1.03 (0.59–1.81)2. Inpatient 5.53 (3.62–8.46)d 83.73 (5) "0.00001

HFSS 0.82 (0.66–1.04)e

PCWP 1.00 (0.97–1.02)Cardiac index 0.47 (0.30–0.75)b

Creatinine 1.29 (0.82–2.02)3. Psychosocial risk 9.98 (2) 0.007

Low [Ref group]Medium 0.54 (0.33–0.89)c

High 1.17 (0.60–2.27)Delisting due to improvement 311. Age 0.98 (0.94–1.02) 2.85 (2) 0.240

Female sex 0.71 (0.23–2.13)2. Inpatient 1.20 (0.34–4.28) 11.52 (5) 0.042

HFSS 1.79 (1.21–2.63)b

PCWP 1.06 (1.01–1.11)c

Cardiac index 1.20 (0.77–1.86)Creatinine 0.77 (0.27–2.21)

3. Psychosocial risk 9.93 (2) 0.007Low [Ref group]Medium 0.23 (0.10–0.54)b

Elective HTx 411. Age 0.99 (0.96–1.02) 1.73 (2) 0.442

Female sex 1.93 (0.90–4.14)e

2. Inpatient 4.07 (2.04–8.09)d 17.00 (5) 0.004HFSS 0.90 (0.65–1.27)PCWP 0.97 (0.93–1.01)Cardiac index 1.09 (0.63–1.89)Creatinine 1.39 (0.73–2.67)

Continued on page 23.

22 The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation, Vol 31, No 1, January 2012

deterioration, 2 improved patients), univariate analyses forpsychosocial risk were repeated combining the high-riskand medium-risk groups. Regarding cumulative incidences,patients of the low psychosocial risk group were signifi-cantly less likely than patients of the medium/high psycho-social risk group to get a MCSD (0% vs 10%, p # 0.025)and to die on the waiting list (7% vs 19%, p # 0.049); yet,they were more likely to experience delisting due to im-provement (22% vs 8%, p # 0.003) and to receive HU-HTx(46% vs 31%, p # 0.040).

Multivariate analyses

In multivariate models including age, sex, inpatient status,HFSS, PCWP, cardiac index, creatinine, and psychosocialrisk group, an unfavorable HFSS still was significantlyassociated with death and a favorable one with delisting dueto improvement (Table 3). Higher PCWP and creatininevalues also increased the risk for death, and a better cardiacindex reduced the risk for HU-HTx (Table 3).

The statistically significant overall associations of psy-chosocial risk with MCSD, delisting due to improvement,and HU-HTx persisted after adjusting for the above-men-tioned covariates (Table 3) and were maintained after addi-tional adjustments for diuretics (MCSD: & chi-square [df 2] #7.58, p # 0.023; HU-HTx: & chi-square [df 2] # 8.19, p #0.017; improvement: & chi-square [df 2] # 12.02, p # 0.002).

The robustness of these results was confirmed whenmore parsimonious models were run omitting non-signifi-cant predictors (Table 4). The HFSS and PCWP both re-mained associated with MCSD, death, and improvement,and the HFSS with HU-HTx (Table 4). The contribution ofpsychosocial risk group to time until MCSD, improvement,and HU-HTx was also stable. Repeating these analyses withthe combination of medium/high psychosocial risk vs lowpsychosocial risk also produced comparable results regard-ing psychosocial risk (MCSD: & chi-square [df 1] # 6.72,p # 0.010; HU-HTx: & chi-square [df 1] # 3.65, p # 0.056;improvement: & chi-square [df 1] # 11.47, p # 0.001;death: & chi-square [df 1] # 1.41, p # 0.235).

Discussion

Our prospective observational data show that the most se-verely ill patients, as defined by the HFSS and the PCWPmeasurements at time of listing, were significantly morelikely to either receive a MCSD, or to be listed as an HUpatient, or to die on the waiting list. These findings confirmthat future deterioration of a transplant candidate can bepredicted by the medical profile at the time of listing. Fur-thermore, the HFSS, which was originally developed topredict survival in ambulatory patients referred for HTxevaluation before MCSD use,18 may also have prognosticvalue in the current era of advanced heart failure manage-ment.10

This extended follow-up of participants in the Waiting for aNew Heart Study underlines the importance of psychosocialrisk for prognosis, including MCSD implantation. Patientswithout depressive symptoms who were also socially inte-grated at the time of listing did not require MCSD support andwere significantly more likely to become delisted due to im-provement compared to patients with high or medium psycho-social risk, even after adjusting for age, sex, and medical riskfactors at time of listing. Specifically, our finding regardingdelisting due to clinical improvement, which was based ontime-to-event modeling and additional covariates (PCWP, car-diac index, creatinine, inpatient status) corroborates our 12-month results.3,4

There was also some suggestion that even the presenceof only one psychosocial risk factor had an adverse effect ondeath on the waiting list. This finding, which did not reachstatistical significance in multivariate analyses, must beviewed cautiously and within the competing risks setting.Patients whose health status deteriorated received rapidHTx while in HU status, which was the case for mostpatients in our cohort, or received a MCSD, thus avoiding“death on the waiting list.”

Unexpectedly, patients with low psychosocial risk werealso at increased risk for HU-HTx similar to patients withhigh psychosocial risk. One might speculate that, indepen-dent of objective health status, socially integrated and psy-

Table 3 Continued from page 22.

Outcome Events HR (95% CI) &Chi-square (df) p-value

3. Psychosocial riskLow [Ref group] 0.51 (2) 0.776Medium 0.94 (0.36–2.45)High 1.36 (0.39–4.81)

CI, confidence interval; NC, not computable because of n # 0 events in the reference group; HFSS, Heart Failure Survival Score; HR, hazard ratio; HTx,heart transplantation; MCSD, mechanical circulatory support device; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure.

All coefficients pertain to the final model. Due to the low event rate of delistings due to clinical deterioration, this outcome was not analyzed inmultivariate models.

aBecause none of the patients with low psychosocial risk needed a MCSD, computation of HRs with this low psychosocial risk as reference group wasnot feasible.

bp-value " 0.01.cp-value " 0.05.dp-value " 0.0001.ep-value " 0.10.

23Spaderna et al. Medical and Psychosocial Predictors of MCSD

chologically stable patients appear to be particularly goodcandidates for HTx, potentially hastening the physician’sdecision for HU listing and subsequent HTx. Studies offactors influencing health professionals’ decisions for HU-HTx listing are clearly warranted.

From a medical perspective, psychosocial risk groups didnot differ substantially at time of listing. Although patientsin the high-risk group were more likely to have ischemicheart disease as the underlying diagnosis, the groups werecomparable in hemodynamic, laboratory, and functional pa-rameters, comorbidities, and most medications.

Considering the similar starting point of the 3 psychos-ocial risk groups at time of listing and the effect of medicalrisk at baseline on prognosis, the role of psychosocial risk isintriguing. Although the psychosocial risk groups did notdiffer in quality of life and in their overall experience ofphysical/medical waiting list-related stressors, such asshortness of breath or medication side effects, group-spe-cific stressor profiles emerged in other stressor domains. Infact, compared with patients with at least one psychosocialrisk factor, patients with low psychosocial risk reportedmore worries about the other family members, not being

Table 4 Parsimonious Multivariate Cox Models for the Outcomes

Outcome Event HR (95% CI) &Chi-square (df) p-value

MCSD 261. Inpatient 1.76 (0.66–4.68) 11.35 (3) 0.010

HFSS 0.65 (0.39–1.07)b

PCWP 1.04 (1.00–1.09)b

2. Psychosocial riska 7.34 (2) 0.025Low [Ref group]Medium NCHigh NC

Death 531. Age 0.98 (0.95–1.01) 7.16 (2) 0.028

Female sex 3.12 (1.69–5.75)d

2. HFSS 0.64 (0.45–0.89)c 33.51 (3) "0.0001PCWP 1.05 (1.01–1.08)c

Creatinine 2.83 (1.71–4.68)e

3. Psychosocial risk 2.25 (2) 0.325Low [Ref group]Medium 1.81 (0.56–5.88)High 2.79 (0.69–11.24)

High urgency HTx 1031. Age 0.98 (0.96–0.99)c 1.59 (1) 0.2072. Inpatient 5.52 (3.65–8.35)e 83.88 (4) "0.00001

HFSS 0.83 (0.67–1.03)b

Cardiac index 0.48 (0.31–0.72)c

Creatinine 1.28 (0.82–2.01)3. Psychosocial risk 9.97 (2) 0.007

Low [Ref group]Medium 0.54 (0.33–0.89)f

High 1.17 (0.60–2.26)Delisting due to improvement 311. Age 0.97 (0.94–1.01) 2.64 (1) 0.1042. HFSS 1.80 (1.23–2.64)c 8.61 (2) 0.013

PCWP 1.06 (1.01–1.10)f

3. Psychosocial risk 11.70 (2) 0.003Low [Ref group]Medium 0.22 (0.08–0.48)d

High 0.32 (0.07–1.49)

CI, confidence interval; HFSS, Heart Failure Survival Score; HR, hazard ratio; HTx, heart transplantation; NC, not computable because of events in thereference group; MCSD, mechanical circulatory support device; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure.

All coefficients pertain to the final model.aBecause none of the patients with low psychosocial risk needed a MCSD, computation of hazard ratios with low psychosocial risk as reference group

was not feasible.bp-value "0.10.cp-value "0.01.dp-value "0.001.ep-value "0.0001.fp-value " 0.05.

24 The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation, Vol 31, No 1, January 2012

able to fulfill family obligations, and inadequate job perfor-mance (Figure 2).

In contrast, patients with high psychosocial risk reportedmore stress than the other 2 groups due to lacking familysupport, to being unable to confide in somebody, withdrawalof friends and acquaintances, fear of being alone if heartproblems arise, doubts if decision for HTx was right, impa-tiently waiting for the phone call, and feelings of hopelessnessand helplessness (Figure 2). This stressor profile indicatesambivalent attitudes towards HTx and emotional problems,whereas patients with low psychosocial risk were more con-cerned with the well-being of others. In turn, these patientsmay receive more support from others to engage in health-related behaviors, given their larger network size. To explorethe validity of this speculation, we compared ratings on thesocial support scales that had also been administered in thepresent study.6 Patients with low psychosocial risk indeedreported higher levels of instrumental support (Mean [M] #4.4 ! 0.8 vs 3.6 ! 1.6), support for healthy eating (M #6.0 ! 2.4 vs 4.1!1.8), and for engaging in physical activity(M # 10.3 ! 3.0 vs 7.9 ! 3.4) than high-risk patients (all p "0.01).

It is conceivable that depressive symptoms and social iso-lation (including living alone) contribute to disease progressionboth via behavioral and physiologic pathways.19 It is discon-certing to note that patients with such risk factors are morelikely to receive surgical therapies that demand psychologicstability and social support to ensure success. Even more dis-concerting may be that only 35% of the depressed patientsreported psychosocial counseling.7 Thus, psychosocial inter-ventions early in the course of HTx are clearly warranted. Theycould help stabilize patients’ health by providing opportunitiesto develop and extend helpful social contacts, involving part-ners, and, possibly, self-help groups. Also, addressing doubtsassociated with the decision for HTx and facilitating emotionalproblem solving, such as reducing fear of being alone whenheart problems emerge, could help to decrease distress and itsnegative effects on the organism.

Our study has several limitations: First, it relied on self-reports for depressive symptoms instead of clinical diagnosisand a single item to assess network size. However, depressionin our study was defined as scores " 9 on the HADS, which isconsidered clinically relevant.20 Moreover, the specific stressorprofiles obtained for the psychosocial risk groups support thevalidity of our categorizations.

Second, predictors were assessed only at time of listing,which precluded an evaluation of potential changes in thesepredictors and their effect on disease progression and out-comes.

Third, event rates, except for HU-HTx, were low, and someof the Cox models had " 10 events per predictor.21 However,this does not necessarily lead to bias in multivariate Coxregression.22 Nevertheless, stability of significant results wasconfirmed by comparing these results with those from models,from which irrelevant predictors had been removed.22 Most ofthe adverse events (ie, death, delisting due to deterioration, andall MCSDs) observed in our sample were confined to those

with elevated psychosocial risk, independent of medical risk,which also supports the validity of our results.

While female gender remained a significant predictor ofdeath in this extended follow-up, the relatively low numberof female patients precludes an examination of gender xpsychosocial risk interactions.23 Yet, there is some indica-tion that psychological factors might have different effectson outcomes in men than in women.23

Finally, further studies incorporating repeated measure-ments of psychosocial risk factors are needed to more pre-cisely elucidate the effect of depressive symptoms and so-cial isolation on different waiting list outcomes, includingMCSD.

To conclude, medical and psychosocial risk factors bothcontributed to the prognosis of HTx candidates in this ex-tended follow-up that included MCSD implantation as anoutcome. Independent of disease severity, depressive symp-toms, together with being socially isolated, appear to berelated to deterioration requiring MCSD, HU-HTx, and re-duced chances for clinical improvement.

Disclosure statementThe authors thank Markus Homberg and Vina Bunyamin for theirassistance in data acquisition and management, and manuscriptpreparation, the hospitals and the patients for their participation,and the reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier versionof this manuscript.

This work was supported by the International Society for Heartand Lung Transplantation (H.S., G.W.), Alexander-von-HumboldtFoundation (G.W.), Eurotransplant International Foundation, Ger-man Academic Exchange Service (G.W.); German Research Foun-dation (DFG, grant numbers SP 945/1-1, SP 945/1-3, SP945/1-4 toH.S., MA 155/75-1 to G.W), and research funds from the JohannesGutenberg-University Mainz (HS).

None of the authors has a financial relationship with a com-mercial entity that has an interest in the subject of the presentedmanuscript or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

A list of study sites and investigators is presented in the Ap-pendix.

Part of this work was presented at the Annual Meeting of theInternational Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT),San Diego, California, April 13-16, 2011.

Appendix

The Waiting for a New Heart Study Group consists of thefollowing sites and investigators:

Eurotransplant International Foundation: Dr Smits, Dr Rah-mel, Prof Dr Meiser;Med. Klinik I/Kardiologie, Pneumologie, Angiologie Uni-versitätsklinikum Aachen: Prof Dr Kelm, Dr Koch;Herz-Zentrum Bad Krozingen: Prof Dr Neumann, Dr Zeh;Herz- und Diabeteszentrum Nordrhein-Westfalen BadOeynhausen: Prof Dr Körfer, Dr Tenderich (now Prof DrGummert);Herzzentrum Dresden: Prof Dr Strasser, Dr Thoms;

25Spaderna et al. Medical and Psychosocial Predictors of MCSD

Herzchirurgische Klinik der Universitätsklinik Erlangen:Prof Dr Weyand, Dr Tandler;Med. Klinik III/Kardiologie Klinikum der UniversitätFrankfurt: Prof Dr Zeiher, Dr Seeger;Klinik für Thorax-, Herz-, und Gefä!chirurgie des Klini-kums Fulda: Dr Dörge;Abt. Kardiologie, Universitätsklinikum Gie!en und Mar-burg, Standort Gie!en: Dr Heidt, Dr Stadlbauer;Klinik für Chirurgie der Medizinischen Universität Graz:Prof Dr Tscheliessnigg, Dr Kahn;Universitätsklinik und Poliklinik für Herz- und Thorax-chirurgie Halle-Wittenberg: Prof Dr Silber, Dr Hofmann;Universitäres Herzzentrum Hamburg GmbH: Prof Dr DrReichenspurner, Dr Meffert, Dr Wagner;Klinik für Herz-, Thorax- und Gefä!chirurgie des Univer-sitätsklinikums Jena: Prof Dr Gummert, Dr Malessa, DrTigges-Limmer;Klinik und Poliklinik für Herz- und Thoraxchirurgie derUniversität zu Köln: Dr Müller-Ehmsen;Klinik für Herzchirurgie des Herzzentrums Leipzig GmbH:Prof Dr Mohr, Dr Doll;II. Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik UniversitätsmedizinMainz: Prof Dr Münzel, Dr Hink;Herzchirurgische Klinik der Universität München: Prof DrReichart, Dr Kaczmarek;Klinik und Poliklinik für Herz-, Thorax- und herznaheGefä!chirurgie der Universität Regensburg: Prof Dr Birn-baum, Dr Rupprecht (now Prof Dr Schmid).

References

1. Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Kormos RL, et al. Third INTERMACS annualreport: The evolution of destination therapy in the United States.J Heart Lung Transplant 2011;30:115-23.

2. Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Kormos RL, et al. Second INTERMACSannual report: more than 1,000 primary left ventricular assist deviceimplants. J Heart Lung Transplant 2010;29:1-10.

3. Spaderna H, Mendell NR, Zahn D, et al. Social isolation and depres-sion predict 12-month outcomes in the “waiting for a new heart study.”J Heart Lung Transplant 2010;29:247-54.

4. Zahn D, Weidner G, Beyersmann J, et al. Combined risk scores anddepression as predictors for competing waiting-list outcomes in theWaiting for a New Heart Study. Transpl Int 2010;23:1223-32.

5. Struber M, Meyer AL, Malehsa D, Kugler C, Simon AR, Haverich A.The current status of heart transplantation and the development of“artificial heart systems.” Dtsch Arztebl Int 2009;106:471-7.

6. Spaderna H, Weidner G, Zahn D, Smits JMA. Social integrationand psychological characteristics of patients with ischemic andnon-ischemic heart failure newly listed for heart transplantation:

The Waiting for a New Heart Study. Appl Psychol HealthWell-Being 2009;1:188-210.

7. Spaderna H, Zahn D, Schulze Schleithoff S, et al. Depression anddisease severity as correlates of everyday physical activity in hearttransplant candidates. Transpl Int 2010;23:813-22.

8. Mehra MR, Kobashigawa J, Starling R, et al. Listing criteria for hearttransplantation: International Society for Heart and Lung Transplan-tation guidelines for the care of cardiac transplant candidates—2006.J Heart Lung Transplant 2006;25:1024-42.

9. Lund LH, Aaronson KD, Mancini DM. Predicting survival in ambu-latory patients with severe heart failure on beta-blocker therapy. Am JCardiol 2003;92:1350-4.

10. Goda A, Lund LH, Mancini D: The Heart Failure Survival Scoreoutperforms the peak oxygen consumption for heart transplantationselection in the era of device therapy. J Heart Lung Transplant 2011;30:315-25.

11. Herrmann-Lingen C, Buss U, Snaith RP. HADS-D Hospital Anxietyand Depression Scale—Deutsche Version. Ein Fragebogen zur Erfas-sung von Angst und Depressivität in der somatischen Medizin.[HADS-D Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale—German version.A questionnaire to assess anxiety and depression in somatic medicine.]2nd ed. Bern: Huber; 2005.

12. Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Gravel G, et al. Social support, de-pression, and mortality during the first year after myocardial infarction.Circulation 2000;101:1919-24.

13. Jalowiec A, Grady K, White-Williams C. Stressors in patients awaitinga heart transplant. Psych Med 1994;19:145-54.

14. Rector TS, Kubo SH, Cohn JN. Patients’ self-assessment of theircongestive heart failure. Part 2: Content, reliability and validity of anew measure, the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire.Heart Fail 1987;198-209.

15. Kim HT. Cumulative incidence in competing risks data and competingrisks regression analysis. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:559-65.

16. Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulativeincidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat 1988;16:1141-54.

17. Beyersmann J, Dettenkofer M, Bertz H, Schumacher M. A competingrisks analysis of bloodstream infection after stem-cell transplantationusing subdistribution hazards and cause-specific hazards. Stat Med2007;26:5360-9.

18. Aaronson KD, Schwartz JS, Chen T-M, Wong K-L, Goin JE, ManciniDM. Development and prospective validation of a clinical index topredict survival in ambulatory patients referred for cardiac transplantevaluation. Circulation 1997;95:2660-7.

19. Kop WJ, Synowski SJ, Gottlieb SS. Depression in heart failure: biobe-havioral mechanisms. Heart Fail Clin 2011;7:23-38.

20. Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of theHospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review.J Psychosom Res 2002;52:69-77.

21. Harrell FE, Jr., Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models:issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy,and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 1996;15:361-87.

22. Vittinghoff E, McCulloch CE. Relaxing the rule of ten events pervariable in logistic and Cox regression. Am J Epidemiol 2007;165:710-8.

23. Weidner G, Zahn D, Mendell NR, et al. Gender and emotional supportas predictors of death and clinical deterioration while waiting for aheart transplant: Results from the 1-year follow-up. Prog Transplant2011;21:106-14.

26 The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation, Vol 31, No 1, January 2012