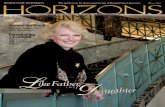

Mediating Generation: the mother-daughter plot

Transcript of Mediating Generation: the mother-daughter plot

Mediating Generation: the mother±daughter plot1

Lisa Tickner

1 Vanessa Bell

Let me begin with two images. One, a photograph of Virginia Woolf, wearing hermother's dress in Vogue, May 1926 (plate 8).2 (In January, revising her plan forTo the Lighthouse, with its portrait of her parents as Mr and Mrs Ramsay, shehad written that `we are handed on by our children.')3 Two, The Red Dress (c.

Art History ISSN 0141-6790 Vol. 25 No. 1 February 2002 pp. 23±46

23ß Association of Art Historians 2002. Published by Blackwell Publishers,108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

8 Virginia Wolf photographed in her mother's dress, Maurice Beck andHelen Macgregor, Vogue, May 1926. ß The Conde Nast Publications Ltd.

1929, plate 9) by her sister Vanessa Bell, in effect a kind of composite self-portrait:Bell in the guise of her mother Julia Stephen, as she appears in a photograph byher great-aunt, Julia Margaret Cameron (plate 10). (The photograph is plate 19 inVictorian Photographs of Famous Men and Fair Women, published withintroductions by Woolf and Roger Fry in 1926.)4 Their father Leslie Stephenwas a `Famous Man'.5 His library and example as an eminent writer were ofinestimable value to Virginia, who was embittered but perhaps also emancipatedby her exclusion from the Cambridge education of her father and brothers. (In ARoom of One's Own, musing on `how unpleasant it is to be locked out', sheconsiders `how it is worse perhaps to be locked in'.)6 Their mother Julia was a`Fair Woman' ± Leslie's `saint', a paragon of womanly virtues and a noted beauty,painted by Watts and Burne-Jones.7 This was a more equivocal heritage for theartist±daughter.

9 Vanessa Bell, The Red Dress, c. 1929. Oil on canvas, 73.3 � 60.5 cm.Photograph courtesy of Brighton Art Gallery. ß 1961 The Estate ofVanessa Bell, courtesy of Henrietta Garnett.

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

24 ß Association of Art Historians 2002

Julia Margaret Cameron, on the other hand, offered a rather unusual instanceof Victorian, middle-aged, matriarchal creativity, ruthlessly pursued. Tennysonreferred to her `wild-beaming benevolence', and Annie Thackeray to the `markedpeculiarity' of all seven Pattle sisters in `their respect for their own time' . . . `Theywere busy with their own affairs, and anything they undertook they followed upwith absolute directness of purpose.'8 This `masculine' ambition and focus wascombined ± in Carol Armstrong's view of Cameron ± with an engagement withphotography `as something altogether different from technical mastery,pertaining, rather, to the domestic, the incestuously familial and the feminine;as something like hysteria ± the hysteria of the mother'.9

10 Julia Margaret Cameron, photograph of Julia Jackson (later Duckworth,later Stephen), c. 1866. Plate 19 in Victorian Photographs of Famous Men andFair Women, with introductions by Virginia Woolf and Roger Fry, HogarthPress, London, 1926.

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

ß Association of Art Historians 2002 25

When Vanessa moved her siblings to Bloomsbury on the death of their fatherin 1904, she wrote to Virginia:

I have been hanging pictures in the hall . . . On the right-hand side as youcome in I have put a row of celebrities: 1. Herschel ± Aunt Julia'sphotograph. 2. Lowell. 3. Darwin. 4. father. 5. Tennyson. 6. Browning.7. Meredith ± Watts' portrait. Then on the opposite side I have put five ofthe best Aunt Julia photographs of Mother. They look very beautiful alltogether.10

On the right, the Famous Men; on the left, the Fair (Dead) Woman, structuringthe sisters' heritage through masculine intellect and feminine beauty, except thatthe mediating term is the photographer herself (famous and a woman).

Woolf claimed that `we think back through our mothers if we are women'(seeing the tradition of `great male writers' as a source of pleasure but not of help).11

She meant elective rather than natural mothers, in whom the nurturing roles mightbe reversed.12 Feminine creativity required the murder of `the Angel in the House',the internalized imago of their dead mother Julia, the embodiment of purity, defer-ence and chronic unselfishness.13 But Bell, like Woolf, could draw on Julia MargaretCameron's photographs of their mother (her niece and namesake), as a way ofmemorializing her, while staking a claim to a specifically matrilineal artistic heritage.

2 Mediating Generation: Bloom and Bourdieu

Woolf wrote that `books are descended from books as families are descendedfrom families . . . They resemble their parents; yet they differ as children differ,and revolt as children revolt.'14 This (almost) anticipates Harold Bloom, theAmerican critic, who argues that generation is a matter of oedipal rivalry and`creative misreading'. In Bloom's terms, the `anxiety of influence', successfullynegotiated, ensures the fertility of a vigorous, evolving, patrilineal genealogy:

battle between strong equals, father and son as mighty opposites, Laius andOedipus at the cross-roads . . . major figures . . . struggle with their strongprecursors, even to the death.15

How then are women to `think back through their mothers'?Several of Bloom's feminist critics have appealed instead to the alternative

myth of Demeter and Persephone.16 Demeter, mourning the loss of her daughterto Hades, negotiates her return for three seasons of the year. Loss is assuaged withthe advent of time: both linear time (the mother ages, the daughter matures) andcyclical time (the seasonal sequence of growth and decay). Demeter's creativity isrestored with Persephone's return. The earth blossoms. The Freudian model ofoedipal rivalry is replaced by an object-relations model of selfhood. Woolf doesnot struggle to free herself at the crossroads (mother and daughter as mightyopposites). She seeks attachment, not separation. A sense of kinship with her`strong precursors' reveals and preserves the heritage that forms and enriches her.

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

26 ß Association of Art Historians 2002

She gives birth retrospectively to `Judith Shakespeare', the poet's sister, who `livesin you and me, and in many other women', and who, with effort on our part, willcome finally to creative life.17 As Ellen Rosenman puts it, the daughter's creativeself lies through the precursor's self, `the situation deemed by Bloom to beintolerable to the male artist'.18 (For his part an unrepentant Bloom insists that:

The strongest women among the great poets, Sappho and EmilyDickinson, are even fiercer agonists than the men. Miss Dickinson ofAmherst does not set out to help Mrs Elizabeth Barrett Browningcomplete a quilt. Rather, Dickinson leaves Mrs. Browning far behind inthe dust . . .)19

No doubt both positions are over-idealized and over-determined: the son'sstruggle to the death on the one hand, the daughter's filial reciprocity on theother. It might help to consider the question of attachment or rupture, not as agendered distinction, but in terms of an historical contrast in modes ofproduction.

Dante's encounter with Virgil, as Gabriel Josipovici points out, was a sourcenot of oedipal rivalry but of wonder and delight. `Are you, then, that Virgil, thatfount which pours forth so broad a stream of speech? . . . You are my master andmy author. You alone are he from whom I took the fair style that has done mehonour.'20 Dante was writing in a craft tradition, before the Enlightenment andearly Romanticism, when the `substantial categories' of state, family, destiny andultimately craft production itself were eroded. From that point tradition and thecapacity to go on, had to be remade locally and contingently, in the rediscovery oftrust, whereas in the craft tradition the artist `thinks of himself as a maker, not acreator; as a supplier of something that is needed by the community, not as theunacknowledged legislator of mankind'. Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, Bach,Mozart, Haydn, were `firmly embedded in a craft tradition' (though Shakespeareand Mozart were already exploring the corrosive effects of a breakdown of trust);Milton, Blake, Wordsworth and Beethoven were not.21 Josipovici argues that:

A craft implies a tradition into which you are inducted by a master; inwhich you serve your apprenticeship; and in which you in turn become amaster. It implies that what you are doing when you practise your craft is,if not necessary to society, at least sanctioned by society. Weaving carpets ifyou are a female member of a nomadic tribe in Eastern Turkey is a crafttradition . . . .22

The anonymous weaver of Turkish kelims or Navajo blankets was trained byher mother; women artists in the craft tradition were trained by their fathers, ornot at all. Where the workshop was a family business a talented daughter couldsometimes help out.23 But the rising academies moved to exclude women, andstudio apprenticeship, still a necessary complement to academic instruction at thetime of David, was modelled on the pattern of father and sons.24 Asking,rhetorically, `Why are there no great women artists?', Linda Nochlin famouslyconcluded that: `The fault lies not in our stars, our hormones, our menstrual

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

ß Association of Art Historians 2002 27

cycles, or our empty internal spaces, but in our institutions and our education.'25

As the craft tradition crumbled and academic authority waned, larger numbers ofwomen than ever before were trained in public and private art schools here andabroad.26 But despite this or because of it, emphasis shifted from the biologicaldivision of labour (men create, women procreate) to women's psychologicalinadequacy as virile, autonomous, even revolutionary artist±agents. Much of thenew aesthetic depended on an (often noisy) plundering of self. In avant-garderhetoric the Academy, mass culture, commerce and fashion ± all the old enemies ±were variously characterized as `feminine' or effete. This is the historical contextfor Germaine Greer's response to Nochlin's question: `you cannot make greatartists out of egos that have been damaged, with wills that are defective, withlibidos that have been driven out of reach and energy diverted into certainneurotic channels.'27 (This is not, in fact, true, and Anthony Storr's The Dynamicsof Creation, among other texts, attempts to outline the relations between variouskinds of neurosis and artistic activity.)28

Vanessa Bell was on the cusp of what the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu calls theautonomizing aesthetic field.29 As a young woman she studied at the RoyalAcademy, admired Watts and poured tea for Meredith and Henry James.Scarcely a decade later she exhibited with the Post-Impressionists, bought aPicasso and dedicated herself to `significant form'. Her first solo exhibition wasin 1922 (when she was forty-three). She would not have made a living from salesalone. Consider, by contrast, Rachel Whiteread, whose acknowledgements tosponsors and benefactors bear witness to the institutionalization of modern art:the Arts Council of Great Britain, the Greater London Arts Association, theElephant Trust, the Henry Moore Foundation, ACME Housing, Artangel,Tarmac Structural Repairs (an award-winner under the Business SponsorshipIncentive Scheme), the Public Art Fund (New York), Beck's Beer, the BritishCouncil, and the dealers Karsten Schubert and Anthony d'Offay. She won theTurner Prize at twenty-nine years old and at thirty-three became the first womanto represent Britain (alone) in the Venice Biennale. None of which is to detractfrom the originality and resonance of her work; only to indicate ± and particu-larly in the case of a sculptor, whose public potential is tied to practicaldifficulties of labour, materials and space ± how individual agency is intricatelyentwined with that web of socio-aesthetic-economic relations which nowconstitutes the cultural field.30

What women have needed is the revision of actual or perceived forms ofexperiential, discursive and psychological difference. That is, freedom from theconstraints on their social opportunity (`our institutions and our education'); andfrom the delimiting effects of mythic narratives of creativity allied to narcissisticcultural investments in the Artist as an infantile idealization of the oedipal Father(who has then to be struggled with and overcome).31 De-idealization here isconnected to the de-masculinization of creative potential. There is, in fact, a greatdeal of psychoanalytic literature on gender and creativity which needs revision,now that the critical mass of women's work is sufficient to undermine its foundingpremises; and in particular the assumption that what women are recognized inexisting terms as having achieved is a measure of their potential under anyconditions of production or evaluation.32

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

28 ß Association of Art Historians 2002

Bloom deals in time, in genealogies, in `strong precursors' and `the anxiety ofinfluence'. Bourdieu deals in space, in the relations of the cultural field. Bloom'smodel is the family tree, Bourdieu's the map. In terms of `mediating gender andgeneration', the first is too exclusive (canonical males); the second too inclusive(an only hypothetically mappable social and psychic space of agents, works,institutions, social relations and `conditions of possibility'). As an image ofgeneration we might take a third model ± Deleuze and Guattari's `rhizome' ±instead. In A Thousand Plateaus, they argue that `evolutionary schemas may beforced to abandon the old model of the tree and descent.' The rhizome is `an anti-genealogy': multiple, diverse, heterogeneous, generative, resistant to hierarchiesand productive in its channelling of desire.33

This is the first generation in which women artists have grown up with bothparents. This eases, if it does not eradicate, the anxiety of influence, which, forwomen, may be the anxiety of finding oneself a motherless daughter seekingattachment, as much as it means rivalling the father while trying to please him.Finding (real and elective) artist±mothers releases women to deal with theirfathers and encounter their siblings on equal terms. Feminism fought for ourright to publicly acknowledged cultural expression; it also insists on our placein the patrimony, equal heirs with our brothers and cousins. Deleuze andGuattari are anti-the tree, anti-descent: `The tree is filiation, but the rhizome isalliance, uniquely alliance.'34 Within the autonomized cultural field, relations incultural space become more pressing, more determinant, than the authority ofthe line. This is not absolute, of course, but there is a compression of referencesuch that synchrony wins out over diachrony, siblings over grandparents.Impossible now to imagine a modern commission for one of those cycles ofgreat artists of the past that Francis Haskell discusses as indices of nationaltaste.35

Women appropriate and misread their fathers and struggle with their brotherstoo. Writing on Rachel Whiteread makes obligatory reference to Nauman's cast ofthe Space under my Steel Chair (1965±8) as the founding moment of `negativespace' and `a kind of parent-object' for Untitled (One Hundred Spaces) of 1995(plate 11). Nauman himself is playing off Johns and Johns off Duchamp. Butclearly One Hundred Spaces is an homage to Nauman and a wry allusion to thecritical literature and its search for origins. It is almost a parody of the assumptionthat women elaborate, colour and interpret, rather than originate structure andform. Briony Fer's description would take some bettering:

the neutral inert surfaces have been rendered invisible and visible insteadis a scintillating surface against the light. It is decrepit but dazzling,worm-eaten but ravishing . . . colour . . . seems to flaunt itself as such, andso overcomes the grid, overcomes even the effect of the cast . . . thelaborious process has its own patina ± more like a half-sucked sweet,glistening here, matt there. Some of the semi-transparent blocks are milkyblue-white, others are iridescent like shot silk or two-tone, almostfluorescent as a pungent, intense pink appears at the edge of a transparentorange block . . . light is trapped inside and the illusion is that the objectemanates light . . .36

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

ß Association of Art Historians 2002 29

What has been won here is not a place in a separate, parallel, maternal lineso much as the right to inhabit, appropriate, or `swerve' from the example offathers and brothers as well as mothers and aunts. The swerve is the first ofBloom's six categories of response to the `strong precursor', in which the artistacknowledges but adjusts the trajectory of the earlier work in `a correctivemovement'; the second is the fragment, the token of recognition that invokes theterms of the parent work before completing it `in another sense, as though theprecursor had failed to go far enough'.37 Both of which One Hundred Spacesdoes, of course. This is how generation is mediated here, not through a line ofunbroken maternal production, but not through murderous rivalry either.He leÁ ne Cixous claims that we become womanly through writing womanlytexts.38 If gender is at issue here it is not as a given but as a discovery in theinterplay, the forward-and-back, of `thinking through our mothers' andprojecting what we can be: `proceeding from the middle, through the middle,coming and going rather than starting and finishing' (Deleuze and Guattariagain).

11 Rachel Whiteread, Untitled (One Hundred Spaces), 1995. Resin, 100 units, size according toinstallation. Installation view: Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburg. Photograph by RichardStoner, courtesy of Anthony d'Offay Gallery, London.

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

30 ß Association of Art Historians 2002

3 Rachel Whiteread: Witness and Loss

Rosalind Krauss remarks that Whiteread's work `is continually moving through afunerary terrain, a necropolis of abandoned mattresses, mortuary slabs, hospitalaccoutrements (basins, hot-water bottles), condemned houses'.39 The criticalresponses to her work converge on the themes of witness and loss. Reference todeath masks, to the archaeological casts of Pompeian bodies dissolved from thevolcanic ash that `moulded' them, to photography as a comparably indexical,negative-to-positive commemorative process: these are standard tropes in theWhiteread literature.40 This gravitational pull back to `Witness and Loss' is not somuch wrong as limiting and exhausted. It masks her formal and technicalinventiveness and what David Batchelor rightly calls the `ecstatic' as well as`melancholy' qualities of more recent works.41 I am going to look finally atcasting, parentage and `monuments' in the context of `mediating generation'.

12 Rachel Whiteread, Untitled (House), 1993. Commissioned by Artangel.Sponsored by Becks. Photograph by John Davies, courtesy of Anthonyd'Offay Gallery, London.

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

ß Association of Art Historians 2002 31

Casting42

In The Poetics of Space (a book Whiteread admires), Gaston Bachelard writes thatwhen a poet polishes his table `with the woollen cloth that lends warmth toeverything it touches, he creates a new object; he increases the object's humandignity; he registers this object officially as a member of the human household.'43

Whiteread's process does the reverse. The object, recast, or defined in negative bythe solidifying of matter around and under it, is `made strange' ± uncanny ±unhomely in the Freudian sense.44 No longer a function or extension of the body,it is expelled from the human household into the world of `Please do not touch'.This is because the `inside-outness' of casting has psychic as well asphenomenological effects. Physical and psychic processes of ingestion andexpulsion, introjection and projection, first sketch the boundaries of a bodily`I'. (As Bachelard puts it, `Being is alternately condensation that disperses with aburst, and dispersion that flows back to a centre.')45 Casting as a kind of anatomylesson produces uncanny sensations in a viewer positioned in the impossible spacebetween inside and outside, or facing a work that anthropomorphizes the spacesof occupation. (Making House [plate 12], Whiteread says, `was like exploring theinside of a body, removing its vital organs'.)46

Whiteread discovered her project through discovering its means.47 It beginswith Closet (plate 13), the plaster cast of a wardrobe interior, covered in blackfelt. And it begins with regression.

13 Rachel Whiteread, Closet,1988. Wood, felt and plaster, 151.2� 113.4 � 50.4 cm. Photographcourtesy of Anthony d'OffayGallery, London.

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

32 ß Association of Art Historians 2002

I have a very clear image of, as a child, sitting at the bottom of my parents'wardrobe, hiding among the shoes and clothes, and the smell and theblackness and the little chinks of light . . . [these were] happy places, Isuppose, where you went and dreamt. Places of reverie. And where you'dmutilate your dolls, cut their hair and everything.48

This is a recognizably Kleinian scenario of aggression and reparation. Theaggression projected in mutilating the dolls is present, residually, in theessentially reparative acts of preserving, casting, binding and re-membering inWhiteread's oeuvre. (She has said of Ghost [plate 14] that it was a `plaster castfor a room, built up inch by inch . . . like covering a broken limb'.)49 These arestrategies that Mignon Nixon identifies in a Kleinian reading of feminist workwhich focuses not on a Freudian or Lacanian understanding of oedipalgendering, but on pre-oedipal (and hence ungendered) aggression in the field ofinfantile fantasy. The foremother here is Louise Bourgeois, whose delayedreception Nixon credits to `the current generation of feminist artists' which has`received and re-examined the investigation of the drives as a project of feministart'.50 (She is a Judith Shakespeare, in other words, brought to publiclyrecognized creative life through the work of the daughters she has alsoinspired.)

14 Rachel Whiteread, Ghost, 1990. Plaster on steel frame, 270 � 318 � 356 cm. SaatchiCollection, London. Photograph courtesy of Anthony d'Offay Gallery, London.

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

ß Association of Art Historians 2002 33

Generation51

Whiteread says that recent works `don't have that residue of everyday life on themso much'. `They have a sense of shape, form and colour, they don't have a sense ofshape, form, colour, and oh-is-that-granny's-fingerprint-underneath-that-table.'52

More icon, less index. More absorption, less theatricality.53 In interviews, she hasmentioned the influence of Carl Andre and Vito Acconci.54 But two differentparents come to mind. Is not Untitled: One Hundred Spaces by Nauman out ofEva Hesse (by Space Under My Chair [plate 15] out of Repetition Nineteen III[plate 16])?

Krauss describes Space Under My Chair as `taking the by then recognizableshape of a Minimalist sculpture' while being nonetheless `the complete anti-minimalist object'.55 Eva Hesse's anti-minimalism, while retaining an investmentin repetition and modularity, stressed process, crafted surfaces, elements offiguration, and springy or translucent materials like rubber and resin, all of whichundermined the rational and industrial attributes of Morris or Judd and led to ananxiety about the `feminine' gendering of `eccentric abstraction'. (Hesse wrote inher journal in 1965: `Do I have a right to womanliness? Can I achieve an artisticendeavor and can they coincide?')56 Nauman's cast, according to Krauss, does nottake the `anti-form' route out of minimalism, shattering and disbursing matterbut, more deadly, `the path of implosion or congealing', not of matter, but ofspace.57 All that is air turns solid. Hesse opts for translucency. Lippard speaks ofan `inner glow' and Fer of `buckets of light'.58 One Hundred Spaces, cued byHesse, takes Nauman's Space Under My Chair and (literally) re-casts it: multiplies

15 Bruce Nauman, Space UnderMy Steel Chair, 1965±68.Concrete, 45.1 � 39 � 37 cm.Collection Geertjan Visser, onloan to the Rijksmuseum Kroller-Muller, Otterloo. ß ARS, NY andDACS, London 2001.

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

34 ß Association of Art Historians 2002

it, jellies it, gives it that iridescent sucked-sweet brightness, renders itsimultaneously grave, funny and sublime.

And yet the patterns of affiliation are more fluid than this. Whiteread'swork is calculatedly `and-and' and `neither-nor'. Casting is neither carving(virile) nor modelling (`feminine'), neither fully form (sculpture) nor fullysurface (painting), not quite abstraction or figuration, reproductive yetinventive, simultaneously iconic and indexical (like the photograph) and thisundecidability ± the collapsing of these oppositions ± is, as Fer points out, whatWhiteread's work most fully is.59

Monuments

A monument is `[a] structure, edifice, or erection intended to commemorate anotable person, action, or event'.60 `Monumental' means massive and permanent,historically prominent, conspicuous, enduring. Monuments are `masculine' (withrare exceptions). First, men make them.61 Secondly, the notable persons, actionsand events are chiefly male. Thirdly, they incline to the heroic in theme and tone

16 Eva Hesse, Repetition Nineteen III, 1968. Nineteen tubular fibreglass units, 48 to 51 cm high� 27.8 to 32.3 cm diameter. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Charles and AnitaBlatt. Photograph ß The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Reproduced with the permissionof the Estate of Eva Hesse.

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

ß Association of Art Historians 2002 35

(even or especially when drawing on allegories of the female form).62 Fourthly,they belong in what Julia Kristeva calls `linear time' ± the time of history andnarrative ± where women have been associated with `cyclical time' (the time ofrepetition) or `monumental time' (the time of eternity).63

Virginia Woolf said: `I doubt that a writer can be a hero. I doubt that a herocan be a writer . . . the moment I become heroic, I become shrill and hard andpositive.'64 The rhetoric of heroism has proved inadequate to the traumas of thetwentieth century in which men, women and children were indiscriminatelyslaughtered. No lyric poetry after Auschwitz. The proposal for what wascommissioned as Whiteread's Judenplatz memorial to the Jews of Vienna grewout of local distaste for Alfred Hrdlicka's `grandiose scheme of writhing marblenudes'.65 The difficulties of adequately registering the Holocaust have created agenre of anti-memorials at the same time as Whiteread's generation has grown upin a landscape of artist±mothers informed by feminism.66 One way of marking thedifference between the Statue of Liberty, say, andHouse, is to see it as a shift fromthe `masculine' iconography of the phallic mother to a more `feminine' or feministmemorializing of domestic space. Another is to see it as signalling a breakdown inthe cultural association of women with `cyclical' and `monumental' time, andtheir symbolic reinsertion into the space of `linear' time all humans occupy and inwhich monuments are actually commissioned and produced.67

17 Rachel Whiteread, Holocaust Memorial, Judenplatz, Vienna. Concrete. Photograph courtesyof Anthony d'Offay Gallery, London.

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

36 ß Association of Art Historians 2002

The trajectory from Ghost to House to Judenplatz now seems inevitable, buton the rebound from difficulties in Vienna, Whiteread made Water Tower (plate18) for a public art project in New York.68 This time she `wanted to makesomething that was more like an intake of breath'.69 Water Tower is quiteunforthcoming, sometimes scarcely visible. It does not heckle. It summons theidea of a monument without marking a site of any obvious significance. It sitscomfortably, if a little exotically, among its siblings, implying ± as in the writingof Studs Terkel ± that what is worth remembering is under our noses and over ourheads: the labour and ingenuity of ordinary people and the unpredictable beautyof functional things.70

18 Rachel Whiteread, Water Tower, 1998. Resin cast of the interior ofa wooden water tank, 340.36 cm � 243.84 cm diameter. W. Broadway& Grand Street. A Public Art Fund project, June 1998±June 1999.Photograph by Marian Harders, courtesy of the Anthony d'OffayGallery, London.

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

ß Association of Art Historians 2002 37

Postscript

In 1975 Carolee Schneemann published an essay called `Woman in the Year 2000'.How can I resist it quoting it?

By the year 2000 . . . Our future student will be in touch with a continuousfeminine creative history ± often produced against impossible odds ± fromher present, to the Renaissance and beyond. In the year 2000 books andcourses will only be called `Man and His Image', `Man and His Symbols',`Art History of Man' . . By the year 2000 feminist archaeologists,etymologists, egyptologists, biologists, sociologists will have establishedbeyond question . . . that women determined the forms of the sacred andthe functional . . . evolved property, sculpture, fresco, architecture,astronomy and the laws of agriculture ± all of which belonged to thefemale realms of transformation and production.71

Well, perhaps not quite. But there is an old saying: `I'm a soldier so that my soncan be a politician so that his son can be a poet.' Perhaps Pat Whiteread is afeminist artist so that her daughter does not have to be. Rachel:

When things change, they become part of the fabric of life rather thansomething one has to constantly fight against . . . when people ask if I seemyself as a female artist, or whether my work has a part in feministhistory, I don't think I'm political in that sense. I see myself as a sculptorand as an artist and I think that my mother, her mother and theirgrandmothers worked incredibly hard for my generation to be able to dowhat we do.'72

`Thinking back through our mothers' acknowledges this, along with theheritage of exceptional women. It may be, finally, a necessary condition forreleasing the use-value of the paternal tradition ± enriched, reworked ± in forgingthe culture that is the daughter's bequest.

Lisa TicknerMiddlesex University

Notes

For my daughter ± of course ± Ellie Nairne.

1 This is a slightly extended version of my paperfor the Gender and Generation session of theC.I.H.A. conference, London 2000. I should liketo thank the session organizers, Marcia Pointonand Sigrid Schade, for their interest and support;Adrian Rifkin and Alex Potts for their commentson the original draft; and Jennifer Thatcher atAnthony d'Offay's, Rachel Whiteread and Briony

Fer, among others, for help with the illustrations.My title is borrowed from Marianne Hirsch,whose book The Mother±Daughter Plot issubtitled Narrative, Psychoanalysis, Feminism,Bloomington, 1989. Hirsch is writing about thenovel, `the optimal genre in which to study theinterplay between hegemonic and dissentingvoices' (p. 9). This will not quite work for the

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

38 ß Association of Art Historians 2002

image, of course, which is not `polyvocal' inquite this way, or for those forms of modernismin which the son's dissent has beeninstitutionalized. I have nevertheless held theseterms in mind in exploring the changing relationsof gender and generation ± in both senses ± firstin a painting by Vanessa Bell, and then as theyare reconfigured and given monumental form inworks by Rachel Whiteread.

2 Studio photograph by [Maurice] Beck and[Helen] Macgregor, Vogue's chief photographersin this period. Woolf sat to them in 1924 and1925. A full-face, three-quarter length versionwas taken at the same sitting. See Anne OlivierBell assisted by Andrew McNeillie, The Diary ofVirginia Woolf, vol. 3 1925±30, London, 1980,p. 12, entry for Monday 27 April 1925: `I havebeen sitting to Vogue, the Becks that is, in theirmews, which Mr Woolner built as his studio, &perhaps it was there he thought of my mother,whom he wished to marry, I think.' (The studiosat 4 Marylebone Mews had been built in 1861 bythe PreRaphaelite sculptor Thomas Woolner,who proposed to Julia Jackson but was refused.)See also Elizabeth P. Richardson, A BloomsburyIconography, Winchester, 1989, p. 291 (where thephotograph is dated 1924).

3 Woolf's note on her plan of the ten chapters ofTo the Lighthouse, cited in Juliet Dusinberre,Alice to the Lighthouse: Children's Books andRadical Experiments in Art, Basingstoke, 1987,p. 146. Woolf wrote in `A Sketch of the Past'that until she wrote To The Lighthouse, `thepresence of my mother obsessed me. I could hearher voice, see her, imagine what she would do orsay as I went about my day's doings . . . when itwas written, I ceased to be obsessed by mymother. I no longer hear her voice; I do not seeher . . . I suppose that I did for myself whatpsychoanalysts do for their patients.' (JeanneSchulkind (ed)., Moments of Being, London,1989, pp. 89±90.

4 Victorian Photographs of Famous Men and FairWomen was published by the Hogarth Press,London, 1926. (Fry discusses this particularphotograph on p. 13.) On 2 June 1926 Woolfwrote to her sister about one of her paintingsbased on `the Aunt Julia photograph' in theopening exhibition of the London Artists'Association (Nigel Nicolson [ed.], The Letters ofVirginia Woolf, London, 1977, vol. 3, p. 271). InAugust 1921 Bell had asked Duncan Grant to`bring Aunt Julia's portrait' to Charleston, whereshe hoped to paint from it (perhaps this was thesame picture); see Bell to Grant, 3 August [1921],in Regina Marler (ed)., Selected Letters ofVanessa Bell, London, 1993, p. 254. In 1929 shereferred to copying a Cameron photograph of hermother, probably for this painting of The RedDress, exhibited in 1934 and now in thecollection of Brighton Art Gallery. Both Bell andWoolf resembled their mother physically, but if

anything Bell has rounded and softened herfeatures in The Red Dress, making them closer toher own as a young woman. On the Stephensisters' maternal heritage, see Elizabeth FrenchBoyd, Bloomsbury Heritage: Their Mothers andAunts, London, 1976; Diane F. Gillespie andElizabeth Steele (eds.), Julia Duckworth Stephen:Stories for Children, Essays for Adults, Syracuse,N.Y., 1987; and Martine Stemerick, `VirginiaWoolf and Julia Stephen: The Distaff Side ofHistory', among other essays in Elaine K.Ginsberg and Laura Moss Gottlieb (eds.),Virginia Woolf: Centennial Essays, Troy, N.Y.,1983.

5 Sir Leslie Stephen was a prodigious essayist,editor and biographer, from 1882 the editor ofthe Dictionary of National Biography.

6 Woolf, A Room of One's Own, Harmondsworth,Middlesex [1928], 1973, pp. 25-6.

7 In her diary, Woolf recalls meeting a friend ofher mother, who described her as `the mostbeautiful Madonna & at the same time the mostcomplete woman of the world' (Diary, 4 May1928, vol. 3 op. cit. [note 2], p. 183). She wasvenerated by her husband, who considered thatman unfortunate `who has not a saint of hisown' (`Forgotten Benefactors', 1896, included inSocial Rights and Duties, 2 vols, London, 1896,quotation vol. 2, p. 264). After her early death,Julia was memorialized as the embodiment of anidealized maternity in Leslie Stephen's TheMausoleum Book, ed. Alan Bell, Oxford, 1977.Paintings, portrait-busts, photographs anddrawings of Julia are listed in Richardson, ABloomsbury Iconography, op. cit. (note 2).Appendix A lists twenty-eight photographs of herby Julia Margaret Cameron. One plate isinscribed `My Favourite Picture of All MyWorks. My Niece Julia' (April 1867); another, ofJulia in mourning after the death of her firsthusband, Herbert Duckworth, `She Walks inBeauty' (September 1874). Julia Stephen had beenthe model for the Virgin in Burne-Jones'sAnnunciation, completed in 1879 when she waspregnant with Vanessa. William Rothensteinremembered Vanessa and Virginia `in plain blackdresses with white lace collars and wrist bands,looking as though they had walked straight outof a canvas by Watts or Burne-Jones' (quoted inBoyd, Bloomsbury Heritage, op. cit. [note 4],p. 36).

8 Annie Thackeray's essay on `Alfred, LordTennyson and His Friends' is quoted byElizabeth French Boyd, Bloomsbury Heritage, op.cit. (note 4), p. 87: `our philistine domestic rule,by which, from earliest hour in the morning, thewomen of the house are expected to be at thereceipt of custom, to live in public, to receive anycasual stranger, any passing visitor, was utterlyignored by [the Pattle sisters].' Cameron wasrecalled by others as alarmingly energetic,imperious but sociable, dressed in dark clothes

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

ß Association of Art Historians 2002 39

stained with chemicals (Tennyson is quoted onp. 21).

9 Carol Armstrong, `Cupid's Pencil of Light: JuliaMargaret Cameron and the Maternalization ofPhotography', October, no. 76, Spring 1996, pp.115±41 (quotation p. 119). See also p. 138: as forRoland Barthes, in Camera Lucida, `Cameron'sconception of photography fell under the sign ofthe Mother' . . . `But the other side of thesephotographs' story of sexuality is . . . [that theylean] so heavily on the female side of the familyas to exclude memory of its masculine aspect andits heterosexual foundations.'

10 Vanessa Bell to Virginia Woolf, 1 November1904, Berg Collection, New York Public Library,quoted in Christopher Reed, `A Room of One'sOwn' in Christopher Reed (ed.), Not at Home:The Suppression of Domesticity in Modern Artand Architecture, London, 1996, pp. 147±60(quotation p. 148). Reed discusses the sisters'`liminal position between [patriarchal andmatriarchal] traditions' visualized here.

11 Woolf, A Room of One's Own, op. cit. (note 6),p. 76.

12 It was I think Alan Bennett who added a gloss toPhilip Larkin's famous line `They fuck you up,your Mum and Dad', to the effect that `unless ofcourse they don't fuck you up and you want tobe a writer in which case you're really fucked.'Artists are on the whole not nurtured by Angels.

13 Or so it seemed to Woolf, and seems to me. Seethe chapter on `Vanessa Bell: Studland Beach,Domesticity and `̀ Significant Form'' ' in myModern Life & Modern Subjects: British Art inthe Early Twentieth Century, New Haven andLondon, 2000. A rather different argument isadvanced by the art historian and analystRozsika Parker in ` `̀ Killing the Angel in theHouse''': Creativity, Femininity and Aggression',International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, vol. 79,1998, pp. 757±74. She points out that the `angel'is made to represent `creative inhibition,functioning both intrapsychically andinterpersonally', forbidding `spontaneity,independence, aggression and desire'; but thatWoolf overlooks the angel's potentially positiverole in representing a concern with the work'simpact on the reader or viewer. `Rather thanannihilating the angel, the task of those engagedin creative endeavour is to . . . allow an elementof aggression, assertion and ruthlessness into therelationships that determine creativity withoutlosing the critical awareness of the conditions ofreception that is the positive attribute of theangel.' (pp. 757, 758).

I am very grateful to Rozsika Parker forsending me a copy of her paper after my bookwas in press. It sent me back to two earlier texts,D. W. Winnicott's Playing and Reality, London,1997 and Rozsika Parker's own Torn in Two:The Experience of Maternal Ambivalence,London, 1995. From the perspective of (the

adult's past as) the child, Winnicott locates theorigins of creativity in play and the emergence ofplay in the `potential space' between mother andbaby. (This is the precursor of the potentialspace between adult and environment in whichcultural activity takes place.) From theperspective of the mother, Parker claims `aspecifically creative role for manageable maternalambivalence': that is, she argues that thesuccessful management of the guilt and anxietyprovoked by conflicting emotions of love andhate provides creative release (pp. 6±7).

14 Woolf, `The Leaning Tower', Collected Essays II,p. 163, quoted in Ellen Bayuk Rosenman, TheInvisible Presence: Virginia Woolf and theMother±Daughter Relationship, Baton Rouge andLondon, 1986, p. 134.

15 Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence: ATheory of Poetry, New York and Oxford, 1973,pp. 11, 5. Bloom means `anxiety' in the strong,Freudian sense: `When a poet experiencesincarnation qua poet, he experiences anxietynecessarily towards any danger that might endhim as a poet. The anxiety of influence is soterrible because it is both a kind of separationanxiety and the beginning of a compulsionneurosis, or fear of a death that is a personifiedsuperego.' (p. 58) On Bloom see Louis A. Renza,`Influence', in Frank Lentricchia and ThomasMcLaughlin (eds), Critical Terms for LiteraryStudy, Chicago and London, 1990, pp. 186±202.Renza acknowledges that `the flight patterns ofall texts are determined by the psychiccrosswinds deriving from other texts' (p. 196),but suggests that Bloom's theory `seems todisplace the source of anxious literary productionand reception from culture-specific ideologicalcircumstances to the theatre of timeless psychicforces' (p. 197).

17 On feminist uses of the Demeter-Kore orDemeter-Persephone myth in literary studies, seeAnnette Kolodny, `A Map for Rereading: Or,Gender and the Interpretation of Literary Texts',New Literary History , 11, 1980, pp. 451±67;Ellen Bayuk Rosenman, The Invisible Presence,op. cit. (note 14), pp. 138±9; Mary Jacobus, FirstThings: The Maternal Imaginary in Literature,Art, and Psychoanalysis, New York and London,pp. 16±18.

17 Woolf, A Room of One's Own, op. cit. (note 6),pp. 48±50; pp. 111±2.

18 Ellen Bayuk Rosenman, The Invisible Presence,op. cit. (note 14), p. 139.

19 Harold Bloom, The Western Canon: The Booksand School of the Ages, London and Basingstoke[1994], 1995, p. 34. In Bloom's view it will takemore than a feminist idealization of femininity to`change the entire basis of the Westernpsychology of creativity, male and female, fromHesiod's contest with Homer down to the agonbetween Dickinson and Elizabeth Bishop'. Thereare strong women poets ± Sappho, Emily

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

40 ß Association of Art Historians 2002

Dickinson, Bloom's biblical `J' (perhapsBathsheba, `fully the rival of Homer and Dante,of Shakespeare and Milton') ± but the masculineoedipal trajectory seems to hold for them too.Bloom claims to have been travestied by the `sixbranches of the School of Resentment: Feminists,Marxists, Lacanians, New Historicists,Deconstructionists, Semioticians', but in truth heveers between seeing the anxiety of influence as arelation between writers and a relation betweentexts.

20 Gabriel Josipovici, On Trust: Art and theTemptations of Suspicion, London and NewHaven, 1999, p. 80. Nicholas Penny seems also todoubt the murderous nature of family rivalries inthe craft tradition. Reviewing titles on the HighRenaissance in the London Review of Books,(`Nymph of the Grot', 13 April 2000, p. 19), hewrites that: `When we read of a painter`̀ embracing the counter-maniera'' we are boundto think of an act akin to taking Holy Orders orreversing a political allegiance, but surely itwasn't like that. In as much as artists were awareof adopting or rejecting a style, they sawthemselves more like members of a family,dissociating themselves from a foreign branch,revering and reviving a grandfather'sachievements, rejecting a father but workingalongside an uncle. Models taken from religiousor political practice, or from the `̀ movements'' towhich artists . . . have belonged during the lastcentury, do not help us to assess the ideologicalimplications of stylistic change.'

21 Josipovici, On Trust, op. cit. (note 20), pp. 102,103.

22 ibid., pp. 1±2. This broad-brushed distinctionbetween modes of production carries overlappinghistorical, geographic, sociological, material andgendered connotations: Romantic and modernversus pre-modern; western versus non-western;high versus popular; art versus craft; `masculine'(oedipal, competitive, innovative) versus`feminine' (pre-oedipal, cooperative,interpretative). Most of these are gatheredtogether in his opening example. It chimes withWoolf's assertion that `Anon . . . was often awoman' (A Room of One's Own, op. cit. [note6], pp. 50±1) and her interest in an unegotisticaland communal culture.

23 Artemisia Gentileschi is a famous example. Theprincipal monograph is Mary Garrard, ArtemisiaGentileschi: The Image of the Female Hero inItalian Baroque Art, Princeton, N.J., 1989. Seealso the discussion in chapter 5 of GriseldaPollock's Differencing the Canon: Feminist Desireand the Writing of Art's Histories, London andNew York, 1999. Recent work on the psychologyof creativity, influenced by object relationstheory, suggests that the `internal father' isessential to female creativity, and that fathersnurture it by stimulating and welcoming theirdaughters' often physical excitement and by

sharing in their endeavours. While the womanartist was, for social and ideological reasons,exceptional, the craft tradition could neverthelessfoster such relations, particularly where sonswere lacking, untalented or indifferent. On thepsychology of creativity in women writers, seeSusan Kavaler-Adler, The Compulsion to Create:A Psychoanalytic Study of Women Artists, NewYork and London, 1993.

24 See, for example, Thomas Crow, Emulation:Making Artists for Revolutionary France, NewHaven and London, 1995. Crow calls his studyof David and his followers `a history of missingfathers, of sons left fatherless, and of thesubstitutes they sought'; a history of painter±sonswhose `passionate imagination of antiquitybrought them, over and over again, to thetroubled territory of filiation and inheritance'; ahistory of studio brothers concerned to `seizetheir artistic patrimony' and make their mark onthe turbulent years in which `a king whoembodied all patriarchal authority was put todeath, and a republic of equal male brotherhoodproclaimed'. Crow suggests that David's ownneeds meshed with those of his (fatherless) pupilsto suffuse the studio with a more thanconventionally familial charge, but that moststudios in this period were spaces of an almostexclusively masculine sociability, which `onlyconfirmed an increasing masculinisation ofadvanced art' in which artists were asked `notonly to envisage military and civic virtue intraditionally masculine terms, but werecompelled to imagine the entire spectrum ofdesirable human qualities, from battlefieldheroics to eroticised corporeal beauty, as male'(pp. 1, 2).

25 Nochlin's much-cited essay, `Why Have ThereBeen No Great Women Artists' [1971], is quotedhere from Women, Art and Power and OtherEssays, New York, 1988, p. 150.

26 In the `craft' tradition ± we should probablyinclude the Academies here with the artisans andjourneymen ± few women trained as artists; butwhere they did, its certainties of meaning, value,patronage and purpose embraced them too.(Exclusion was more emphatically social andinstitutional than it was discursive andpsychological.) As so often, women were let in atthe point that men were getting out: Woolf wroteto their brother Thoby in 1901, as Vanessa tookthe entrance examination for the Royal AcademySchools: `Privately I dont [sic] think anyhowthere can be much doubt. The Schools are veryempty, so they will let in bad people.' Virginia toThoby Stephen, Wednesday [July 1901], NigelNicolson (ed)., The Letters of Virginia Woolf,vol. 1, London, 1975, p. 43.

27 Germaine Greer, The Obstacle Race: TheFortunes of Women Painters and Their Work,London, 1979, p. 327. These lines from herconcluding paragraph are given special

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

ß Association of Art Historians 2002 41

prominence on the dustjacket. In the main bodyof her text she goes on to acknowledge the`neurotic' nature of much Western art, whilemaintaining that `the neurosis of the artist is of avery different kind from the carefully culturedself-destructiveness of women.'

28 Anthony Storr, The Dynamics of Creation,London, 1972. Freud himself claimed thatpsychoanalysis had clarified the `internal kinship'between the artist and the neurotic as well as thedistinction between them (`A Short Account ofPsychoanalysis' [1923], The Pelican FreudLibrary, vol. 15, Historical and ExpositoryWorks on Psychoanalysis, Harmondsworth,Middlesex, 1986, p. 180). Storr attempts toanalyse the relations between different kinds ofneuroses and particular forms of creative activityor creative expression. At the same time heacknowledges that psychoanalysis rarelydistinguishes between good and bad art orbetween a work of art and a neurotic symptom.See also Susan Kavaler-Adler, The Compulsionto Create, op. cit. (note 23), in which EmilyDickinson ± one of a handful of great womenpoets in Bloom's canon ± is discussed as one ofthe most `arrested' and unwell. Some analystsdiscriminate between `authentic' creation, whichfacilitates psychic development, and `factitious'creation, which helps maintain the ego's defenceagainst reality. Janine Chasseguet-Smirgel sees`factitious' creativity as one means by which`those who have not been able to project theirEgo Ideal onto their father' grant themselvestheir missing identity, and yet, because paternalcapacities and attributes have not beenintrojected, `find it difficult to be the father of agenuine work' (Creativity and Perversion,London, 1985, pp. 69±70).

29 See, in particular, Pierre Bourdieu, The Rules ofArt: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field,trans. Susan Emanuel, Cambridge [1992], 1996;and The Field of Cultural Production, acollection of translated essays by Bourdieu, ed.Randal Johnson, Cambridge, 1993. On the socialeconomy of modernism, see Robert Jensen,Marketing Modernism in Fin-de-SieÁ cle Europe,Princeton, 1994. The emerging institutions ofBourdieu's `autonomous aesthetic field' ± fromthe Salon des Refuse s of 1863 to the varioussecessions and avant gardes before 1914 ± whiletrumpeting schism and change, were ambiguousin their gendered effects. The educational andexhibition opportunities opening up to womenwere those of a crumbling craft tradition in theprocess of being replaced by a new emphasis onexpressive intensity and `significant form'. In thegalleries of promotional dealers, among thevociferous avant gardes, in terms of high-profilemonographs and retrospective exhibitions,women were largely absent or marginal, and incritical discourse `feminine' and its cognates wereterms of abuse.

30 The circumstances under which Bell andWhiteread came to a practical sense of theirartistic identity were necessarily different. AfterWorld War II, modernism was increasinglyinstitutionalized. In the last twenty years, newcorporate, charitable and private sources offunding have emerged and specialist magazineshave proliferated. Women have filled the artschools on more equal terms. Unlike Bell, whofound Professor Tonks at the Slade a mostdepressing tutor, Whiteread was taught bywomen as well as men, and worked as anassistant to a talented woman sculptor, AlisonWilding. The role models were there. And nowcomputer indexing (there are entries for Bell andWhiteread on The Art Index and in ArtBibliographies Moderne), has itself become apowerful new tool for `thinking back throughour mothers' and keeping their work fromhistorical amnesia. The art market was alwayscommercial, by definition, but it is a big leap inreal terms from Bell's prices to the $167,500 thatWhiteread's dealer, Anthony d'Offay, paid atSotheby's in 1997 for Untitled (Double AmberBed) (1991) ± four times its estimate. (SeeArtnews vol. 96, December 1997, p. 46.)

31 Griselda Pollock (drawing on Sarah Kofman),Differencing the Canon, op. cit. (note 23), pp. 13,16: `The canon is fundamentally a mode for theworship of the artist, which is in turn a form ofmasculine narcissism.' (p. 13) `The question thenis: could we invert it, and insert a feminineversion? Mothers, heroines, female Oedipalrivalry, female narcissism and so forth? Wouldwe want to? Or would we try to side with Freudin the move into an adult rather than an infantilerelation to art by wanting to disinvest from evena revised, feminist myth of the artist, and addressourselves to the analysis of the riddle of the textsunencumbered by such narcissistic idealisation?'The chance of social access to a craft traditionthat might have nurtured women wascompromised with the ideological rise of theartist±hero, the heightening of oedipal tensionsand the conflation of creativity withprocreativity. As Sarah Kofman puts it: `Societytakes the artist to be the father of his creation,and the artist, wishing to believe himself thefather of his works, wants to be his own father.Society therefore grants full licence to the artistto show that he is subject to no externalconstraints, that he is free and fully his ownmaster, that like God, he is self-sufficient.' (SarahKofman, The Childhood of Art: AnInterpretation of Freud's Aesthetics, trans.Winifred Woodhull, New York, 1988, p. 95.)There is not much chance of a foothold for awoman artist in this quasi-theologicalpatrilineage, ideologically speaking, though thevexed question of how `femininity' might figurein the chance play of `biological forces, psychicalforces, and external forces' (Kofman, p. 169) that

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

42 ß Association of Art Historians 2002

in their interaction produce life and art, remainsan open one.

32 See, for example, Phyllis Greenacre, `Woman asArtist' [1960], in Emotional Growth:Psychoanalytic Studies of the Gifted and a GreatVariety of Other Individuals, vol. 2, New York,1971, pp. 575±91. She is inclined to takeNochlin's question as a fact requiringpsychological rather than social explanation,concluding that girls are `more readily blocked inmaterialising artistic creativity . . . both throughthe nature of the castration complex and thespecial exigencies of the oedipal conflict' (p. 591).

33 Gilles Deleuze and Fe lix Guattari, A ThousandPlateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans.and foreword by Brian Massumi, London [1980]1988, pp. 10, 11. Deleuze had already describedhis early work on western philosophers in termsthat read like a homosexual (but fecund) parodyof Bloom's oedipal rivalries, displacing the`anxiety of influence' onto the `strong precursor':`What got me by during that period wasconceiving of the history of philosophy as a kindof ass-fuck, or, what amounts to the same thing,an immaculate conception. I imagined myselfapproaching an author from behind and givinghim a child that would indeed be his but wouldnonetheless be monstrous' (`I Have Nothing toAdmit', 1977, quoted by Brian Massumi in hisforeword to A Thousand Plateaus, p. x).

34 Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus,p. 25. The `Tree or Root as an image, endlesslydevelopes the Law of the One that becomes two,then the two that become four. . . Binary logic isthe spiritual reality of the root-tree.' (p. 5)Whereas the rhizome is `an anti-genealogy'assuming `very diverse forms, from ramifiedsurface extension in all directions to concretioninto bulbs and tubers' (p. 7). Its desirablecharacteristics include its heterogeneity and modeof connection (`any point of a rhizome can beconnected to anything other, and must be'); itsmultiplicity and diversity; its self-generativecapacities; its ability to comprehend different ±viral or technological ± evolutionary schemas; itsresistance to structural or hierarchical models(command trees or centred systems); and itsproductive channelling of desire.

35 Francis Haskell, Rediscoveries in Art: SomeAspects of Taste, Fashion and Collecting inEngland and France, London, 1976, pp. 9±16.

36 Briony Fer, `Treading Blindly, or the ExcessivePresence of the Object', Art History, vol. 20,June 1997, pp. 268±88, quotation pp. 285±6. Thisessay extends a brief account of Whiteread'swork at the end of Fer's book On Abstract Art,New Haven and London, 1997. I have not donejustice to the richness of Fer's discussion of Hesseand Whiteread in brief quotations. Whiteread hasworked hard to exploit the poetic potential of arange of demotic materials unusual in fine art:plaster, resins, different colours and consistencies

of rubber - Untitled (Black Bath) as though hewnfrom a lump of coal, Untitled (Orange Bath)marbled like warm flesh or onyx.

37 Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence, op. cit. (note15), `Synopsis: Six Revisionary Ratios'. Each`ratio' is assigned a name from esoteric classicalsources. Clinamen ± a swerve: the poetacknowledges but adjusts the trajectory of anearlier poem in `a corrective movement' to thatwhich it should have taken. Tessera: a fragmentor token of recognition enables the poet to retainthe terms of the parent poem while meaningthem `in another sense, as though the precursorhad failed to go far enough'. Kenosis: a breakfrom the precursor, `a revisionary movement ofemptying' which seems a kind of humbling butwhich, in fact, deflates or empties out theprecursor-poem. Daemonization: the later poetopens himself to a power in the parent poem infact deriving from sources beyond it, so as `togeneralize away the uniqueness of the earlierwork'. Askesis: a `movement of self-purgation',of curtailing, in which the later poet yields uppart of his own human and imaginativeendowment', separating himself from othersincluding the precursor, so that `the precursor'sendowment is also truncated.' Apophrades: `thereturn of the dead'; the later poet holds his workopen to the precursor in such a way as toproduce the uncanny effect of reversing theheritage, `as though the later poet himself hadwritten the precursor's characteristic work'.

38 Cixous is cited in Griselda Pollock, Differencingthe Canon, op. cit. (note 23), p. 123.

39 Rosalind Krauss, `X Marks the Spot' in RachelWhiteread: Shedding Life, exhib. cat., TateGallery Liverpool, 13 Sept. 1996±5 Jan. 1997, pp.74±81 (quotation p. 76). Whiteread admits tohaving been preoccupied with death. Interviewedby Lynne Barber she said that she did not reallywant to talk about it, but acknowledged that`there was a period when I made a lot of workthat was obviously very connected with it' (`In aPrivate World of Interiors', Observer, 1September 1996, pp. 7±8). Her father died of aheart condition in 1989, soon after she left theSlade, and a couple of months before she madethe first `bed piece' called Shallow Breath. By thispoint she had experienced an unusual number ofdeaths in her circle (about ten). `I try not tothink about it too much.' Like most artists, andunderstandably, she does not want the value andmeaning of her work to be constrained by abiographical reading.

40 Krauss (ibid., p. 76) suggests that `Barthes hasalready written the outlines of a critical text onWhiteread's art, in his own consideration ofphotography as a kind of traumatic death mask'.And in conversation with Fiona Bradley,Whiteread spoke `about casting in terms ofremoving a surface from one thing and putting iton to another, of `̀ taking an image''' (invoking

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

ß Association of Art Historians 2002 43

death masks, and photography). RachelWhiteread: Shedding Life, op. cit. (note 39),p. 14.

41 David Batchelor in the Burlington Magazine,Dec. 96, pp. 837±8.

42 Casting has a lowly place in the repertoire ofsculptural techniques. Carving, modelling, evenconstruction, are seen to require the active andinventive deployment of resistant materials.Casting was traditionally a technical process ofduplication, of transcribing surfaces or producingmultiple copies for clients or the studio. Castcourts, as Rosalind Krauss points out (ibid.,p. 80), `do not pretend to have the repleteness ofa work of art' but `are signposts pointingelsewhere' (usually to ancient Rome orRenaissance Italy). Whiteread's casts also `pointelsewhere', to the ordinary objects from whichthey are made and the human processes whichuse and mark them. Whiteread is extraordinarilyattentive to surface ± she retains the marks of thepathologist's knife on the mortuary slabs andencourages rust to bleed through the plaster ofEther like scum in the bath. But the imprint ofdaily activity, morbid or mundane, is subservientto the overall impact of forms claiming `therepleteness of a work of art'. Some women artistshave, perhaps subliminally, found in the use ofunpretentious materials or techniques a disguiseor disclaimer for aesthetic `presumption'. Castingmight then appeal precisely because it is a wayof generating something with (apparently)minimal intervention. Casting ± an ear, a chair, aroom, a house ± suggests a non-style style, atransaction between surfaces rather than theexpression of a personality. It has nevertheless,become Whiteread's signature (and scanning theplaster surfaces I wonder if the combination ofWhite + Read is mere coincidence).

43 Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, trans.Maria Jolas, Boston [1958], 1994, p. 67. In thecourse of this passage the subject shifts gender.`The housewife awakens furniture that wasasleep. . . A house that shines from the care itreceives appears to have been rebuilt from theinside . . . In the intimate harmony of walls andfurniture, it may be said that we becomeconscious of a house that is built by women,since men only know how to build a house fromthe outside, and they know little or nothing ofthe `̀ wax'' civilization.'

44 This is often referred to in shorthand as `negativespace'. It is not, of course; space is not `negative'.It is the positive materialization of space enclosedby or surrounding an object by making a mouldof it. The mould itself becomes the artwork.There is always an interplay of positive andnegative. Mostly the stress is on the strangenessof the negative. Sometimes, as with the baths(such as Ether, 1990), the negative underside ofthe bath echoes the original surface so that itreads like a larger and more sepulchral positive.

In either case, space flows on and around theinitiating object. Limiting the shape of the mould± shaping the new work ± is an aestheticdecision, sometimes a controversial one. See, forexample, Tom Lubbock's attentive but reductivecritique, `The Shape of Things Gone', ModernPainters, vol. 10, Autumn 1997, pp. 34±7: `Thegood works of Rachel Whiteread are few andthese: Ghost (the room), House (the house),Torso (the hot-water-bottle).' (p. 34) He excludesthe other works as exploiting redundant,arbitrary or `under-motivated' spaces.

Various writers discuss Whiteread and the`unheimlich'. Anthony Vidler, contributing toRachel Whiteread: House, ed. James Lingwood,London, 1995, p. 71, notes that: `the causes ofuncanny feelings included, for Freud, thenostalgia that was tied to the impossible desire toreturn to the womb, the fear of dead thingscoming alive, the fragmentation of things thatseemed all too like bodies for comfort' (allthemes arising in responses to House). This waspartly because of the way in which it seemed toincite but also to cancel the memory of livedsocial relations (in glaring contrast, as DoreenMassey points out, with the efforts of heritagesites to `animate' the past) (ibid., p. 43).Margaret Iversen lists further components of theuncanny in art (and refers to Ghost) in `In theBlind Field: Hopper and the Uncanny', ArtHistory, vol. 21, September 1998, pp. 409±29.

45 Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, op. cit. (note43), `the dialectics of outside and inside', pp.217±8.

Neville Wakefield points out (Parkett, p. 79)that Valley and the bath pieces posit `theabsented body as extending into a domesticarterial and venous system similar to, and indeedconnected to, its own': the corporeal flows of thebody, with their psychic analogues, mesh withthe mechanics of household plumbing andenvironmental water and sewage systems,electricity and gas supplies, informationhighways.

46 Whiteread began by making casts of parts of herbody as a student, before deciding that:`Everything we use has been designed by us andfor us, and for me that is much more interestingthan replicating our physical tangibilities.'(Grunenberg p. 15) On `the space of release' seeNeville Wakefield, `Rachel Whiteread: SeparationAnxiety and the Art of Release', Parkett, no. 42,December 1994, pp. 76±82. Wakefield notes thatWhiteread uses sophisticated silicon releases,microns thin, and that the space we are presentedwith as viewers is `an impossible space, viewedfrom a position we could never assume, the spacebetween object and cast, the space of release'(pp. 76, 78). Mark Cousins points out that it isvery difficult to `read' the inverted detailing ofcast constructions. `It is as if perception wants totravel in the opposite direction from the

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

44 ß Association of Art Historians 2002

intellectual knowledge of what is beingrepresented, of what has been cast. Perceptuallyit is as if we demand to read the object as theexterior of a solid construction.' (Cousins, `InsideOutcast', Tate, no. 10, Winter 1996, pp. 36±41,quotation p. 37.)Whiteread compared the process of casting

House to `exploring the inside of a body' in avery interesting interview with Andrea Rose: `Wespent about six weeks working on the interior ofthe house, filling cracks and getting it ready forcasting. It was as if we were embalming a body.'(`Rachel Whiteread Interviewed by Andrea Rose,March 1997', in Rachel Whiteread, London,1997, catalogue for the British Pavilion at theXLVII Venice Biennale, 15 June±9 November1997, pp. 29±35, quotation p. 33.)

47 Whiteread has in different contexts creditedEdward Allington and Richard Wilson withshowing her how to cast. See the Lynn Barberinterview, `In a Private World of Interiors' op.cit. (note 39), pp. 7±8: `It was just incrediblyliberating that you could make an impression insand and pour molten metal into it and then youhad an object. I liked the simplicity and thedirectness of it . . . you're also changingsomething that exists . . . That's what I like, thatyou can subtly change people's perception of theeveryday.'

48 Lynn Barber interview, ibid., pp. 7±8. See alsoBachelard, The Poetics of Space op. cit. (note43), p. 79: `Every poet of furniture . . . knowsthat the inner space of an old wardrobe is deep.A wardrobe's inner space is also intimate space,space that is not open to just anybody . . . In thewardrobe there exists a centre of order thatprotects the entire house against uncurbeddisorder.' (Bachelard seems to be thinking of alinen-closet or armoire.) And on the relation ofmemory to art, see Sarah Kofman, TheChildhood of Art: An Interpretation of Freud'sAesthetics, trans. Winifred Woodhull, New York,1988, p. 78: `though it is true that the work ofart bears the traces of the past, these traces arenot to be found anywhere else . . . the work doesnot translate memory in distorted form, butrather constitutes it phantasmally.'

49 `Rachel Whiteread in conversation with IwonaBlazwick', in Rachel Whiteread, exhib. cat.,Vann Abbemuseum, Eindhoven (n.d., c. 1992),pp. 8±16, quotation p. 14.

50 Mignon Nixon, `Bad Enough Mother', October,no. 71, Winter 1995, pp. 70±92 (quotation p. 91).

51 I have focused on `elective' parents here but it issignificant that Whiteread's mother, Pat, isherself an artist. As a child, Whiteread was takenon many trips around England with her parents.Her father, a former geography teacher, wouldpoint out glacial formations in the naturallandscape. Her mother would stop the car tophotograph the industrial desecration of thelandscape for her political collages. Her father

taught her `to look up'. Her mother set anexample of drive and tenacity.

52 `In a Private World of Interiors', op. cit. (note39), p. 8.

53 Figurative and metaphorical references, andsurfaces marked by human gesture, are a kind ofheresy in minimalism, but what Whiteread shareswith minimalist sculpture is a concern with thephenomenological encounter between viewer andwork.

54 Whiteread interviewed by Iwona Blazwick, op.cit. (note 49), p. 9: Andre (`Mainly through theconfidence of placing something, having theconfidence to put a white block in the middle ofthe floor and let it be simply a white block');Acconci, more surprisingly, as an influencethrough his masturbatory Seed Bed onWhiteread's floor pieces. Andre 's minimalism isthat of a `masculine' rationality adapted to theuse of industrial surfaces, geometric form andstandardized units; Acconci's performance artdepends on a `feminine' (or effeminate)exploitation of the exhibitionist body. Bringingthem into contact produces an interestinglyhybrid aesthetic: the gestalt of a quasi-minimalistform which nevertheless registers the contingenttraces of human presence; and the suggestion offigurative reference, narrative, even theatricalityin objects and surfaces pressed by the castingprocess into the semblence of modernist form.House, as Anthony Vidler points out, is less likeits Victorian original than the modernistprototypes of Loos, Reitveld, Corbusier and Mies(Anthony Vidler, `A Dark Space' in JamesLingwood (ed)., Rachel Whiteread: House, op.cit. [note 44], p. 68). (Vidler also points out thatarchitectural schools have, since the 1930s, usedsolid plaster models of interior spaces todemonstrate the history of spatial types and todemonstrate by implication the `purity' of ahistory of architecture understood as a history ofmanipulated space rather than period styles.)

55 Krauss, `X Marks the Spot', op. cit. (note 39),p. 74.

56 Hesse is quoted in Lucy Lippard, Eva Hesse,New York, 1976, p. 34. `Eccentric Abstraction'was the title of an exhibition organized byLippard and including Hesse at the FischbachGallery, New York, 20 September±October 81966. There is now an extensive literature onHesse, but for an account of the problematicrelations between gender and modernism, see inparticular Anne MiddletonWagner, Three Artists(Three Women): Modernism and the Art ofHesse, Krasner and O'Keeffe, Berkeley, 1996).

57 Krauss, `X Marks the Spot' op. cit. (note 39),p. 74.

58 Briony Fer (who also quotes Lippard), `TreadingBlindly', op. cit. (note 36), pp. 278, 279.

59 Briony Fer, On Abstract Art, op. cit. (note 36),p. 162. Fer, talking about the floor pieces,suggests that Whiteread's work `falls somewhere

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

ß Association of Art Historians 2002 45

between abstraction and figuration', anopposition that collapses as she `stages theabstract in its phantasmatic dimension'. FredOrton borrows from Jacques Derrida indiscussing the `undecidability' of Jasper Johns'sFlag (1954±5): see chapter 2, `A Different Kind ofBeginning', in Orton, Figuring Jasper Johns,London, 1994.

60 According to the Shorter Oxford EnglishDictionary. The function of monuments is tocarry the past into the future, beyond thevagaries of human memory. (Or perhaps wemake them so that we can forget. Robert Musilremarked that: `There is nothing in the world asinvisible as a monument . . . Like a drop of wateron an oilskin, attention runs down them withoutstopping for a moment'. Quoted in JamesLingwood (ed.), Rachel Whiteread: House, op.cit. (note 44), p. 11 (in Lingwood's introduction).

61 Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock have atelling quotation from `Du rang des femmes dansl'art', Gazette des Beaux-Arts (1860), OldMistresses: Women, Art and Ideology, London,1981, p. 13: `Male genius has nothing to fearfrom female taste. Let men of genius conceive ofgreat architectural projects, monumentalsculpture, and elevated forms of painting. In aworld, let men busy themselves with all that hasto do with great art. Let women occupythemselves with those types of art they havealways preferred, such as pastels, portraits, orminiatures.'

62 See Marina Warner, Monuments & Maidens:The Allegory of the Female Form, London, 1985,p. xix: `Often the recognition of a differencebetween the symbolic order, inhabited by ideal,allegorical figures, and the actual order, ofjudges, statesmen, soldiers, philosophers,inventors, depends on the unlikelihood of womenpractising the concepts they represent.'

63 Julia Kristeva, `Women's Time', trans. AliceJardine and Harry Blake, in Toril Moi (ed)., TheKristeva Reader, Oxford, 1986, pp. 187±213.

64 Speech before the London/National Society forWomen's Service, 21 January 1931, in MitchellA. Leaska (ed.), The Pargiters, London, 1978,pp. xxxix, xliv. A shorter version was publishedas `Professions for Women' (ed. Barret., 1979 pp.57±63).

65 Robert Storr, `Remains of the Day', Art inAmerica, vol. 87, April 1999, pp. 104±109, 154,quotation p. 108. Hrdlicka's five-part Monumentagainst War and Fascism in the Albertinaplatz isillustrated and discussed in James Young, TheTexture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials andMeaning, New Haven and London, 1993,

pp. 106-12. One of its most controversialcomponents is the street-scrubbing Jew (after theAnschluss, local Jews were made to scrub anti-Nazi graffiti from buildings and cobblestones).Unheeding pedestrians used it as a bench so thatit had to be defended against insult with barbedwire. See also Adrian Forty and Susanne KuÈ chler(eds), The Art of Forgetting, Oxford and NewYork, 1999, which refers to Whiteread'sJudenplatz memorial pp. 12±13.

66 Whiteread considers Maya Ying Lin's VietnamMemorial in black granite, inscribed with thenames of 58,000 American soldiers, `profoundlymoving . . . one of the few great contemporarymemorials' (interview with Andrea Rose, op. cit.[note 96], p. 31).

67 In Kristeva's view the `corporeal and desiringspace' is now available for the `parallel existenceor the intermingling of all three approaches tofeminism, all three concepts of time' (in TorilMoi (ed)., The Kristeva Reader, op. cit. (note63), p. 188).

68 See Looking Up: Rachel Whiteread's WaterTower, ed. Louise Neri, New York, n.d. It hasthe following dedication: `This project isdedicated to my father, Thomas Whiteread(1928±1988), whose interest in industrialarchaeology enabled me to look up. '

69 ibid., pp. 166, 167. Roberta Smith says it relatesto its neighbours `as a translucent, freshly shedsnakeskin relates to a snake'.

70 Studs Terkel, U.S. oral historian, is the author orcompiler of various collections includingWorking: people talk about what they do all dayand how they feel about what they do, London,1975, and Coming of Age: the story of ourcentury by those who've lived it, New York,1995. Woolf, `Women and Fiction', reprinted inMicheÁ le Barrett (ed.), Virginia Woolf: Womenand Writing, London, 1979, p. 44: `But of ourmothers, our grandmothers, our greatgrandmothers, what remains? . . . it is only whenwe can measure the way of life and theexperience of life made possible to the ordinarywoman that we can account for the success orfailure of the extraordinary woman as a writer[an artist].'

71 Carolee Schneemann, in Bruce McPherson (ed.),More than Meat Joy: Carolee Schneemann:Complete Performance Works & SelectedWritings, New Paltz, New York, 1979, pp. 198±9.

72 `When things change': Carey Lovelace, `WeighingIn On Feminism', Art News, May 1997, p. 145;`when people ask': Andrea Rose interview, op.cit. (note 46), p. 33.

THE MOTHER±DAUGHTER PLOT

46 ß Association of Art Historians 2002