Mechanisms of change in adolescent life satisfaction: A longitudinal analysis

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

4 -

download

0

Transcript of Mechanisms of change in adolescent life satisfaction: A longitudinal analysis

Journal of School Psychology 51 (2013) 587–598

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of School Psychology

j ourna l homepage: www.e lsev ie r .com/ locate / j schpsyc

Mechanisms of change in adolescent life satisfaction: A longitudinal analysis

Michael D. Lyons, E. Scott Huebner ⁎, Kimberly J. Hills, M. Lee Van HornUniversity of South Carolina, USA

a r t i c l e i n f o

⁎ Corresponding author at: Dept. of Psychology, UE-mail address: [email protected] (E.S. Huebner).ACTION EDITOR: Andrew Roach.

0022-4405/$ – see front matter © 2013 Society for thehttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2013.07.001

a b s t r a c t

Article history:Received 22 June 2012Received in revised form 1 July 2013Accepted 8 July 2013

This study explored the psychosocial mechanisms of change associated with differences in levelsand linear change of adolescents' global life satisfaction across a 2-year time period. Based on atheoretical model proposed by Evans (1994), this study tested the relations between selectedpersonality (i.e., extraversion and neuroticism) and environmental (stressful life events) variablesand global life satisfaction whenmediated by internalizing and externalizing problems. The resultssuggested support for internalizing problems as a mediator of the relationship of personalityand environmental variables with life satisfaction. Pathways mediated by internalizing problemssignificantly predicted levels and linear change of life satisfaction across a 2-year time span.Furthermore, pathways mediated by externalizing problems significantly predicted the level butnot the linear change of life satisfaction. Thus, behavior problems and their antecedents appear torelate significantly to adolescents' perceptions of their quality of life. Implications for adolescentmental health promotion were discussed.© 2013 Society for the Study of School Psychology. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:Life satisfactionAdolescenceInternalizing problemsExternalizing problemsPersonalityLife events

1. Introduction

School psychologists have historically focused on identifying risk factors that contribute to psychopathology in childrenand adolescents. Although this research has provided a better understanding of potential causes of psychopathology, positivepsychology research suggests that a focus on reducing symptoms of psychopathology in children is not enough (Seligman& Csikszentmihalyi, 2001). For example, Suldo, Thalji, and Ferron (2011) found that collecting data on a child's positive subjectivewell-being (including life satisfaction) in addition to traditional indicators of psychological symptoms provided a morecomprehensive assessment of mental health and predicted significantly more variance in students' school performance. Thisstudy and similar studies (e.g., Antaramian, Huebner, Hills, & Valois, 2010; Lyons, Huebner, & Hills, 2012) suggests that collectinginformation on a child's subjective well-being could prove to be useful in fully understanding children's mental health and schooladjustment.

Subjective well-being is typically conceptualized as a higher-order construct including individuals' reports of global lifesatisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect (Diener, 2000). Perception of overall quality of life, or global life satisfaction, hasreceived the most research attention in children and adolescents (Huebner, Gilman, & Ma, 2012; Proctor, Linley, & Maltby, 2009).Global life satisfaction has been defined as a person's cognitive evaluation of her life overall, based on her own criteria (Shin &Johnson, 1978). Life satisfaction measures can reflect a continuum of judgments ranging from very low satisfaction to neutralto very high satisfaction. Life satisfaction has proven to be a useful psychological construct in children and adults reflectingmeaningful relationships with a wide-ranging network of measures of adaptive and maladaptive functioning across a variety ofmajor life domains (Diener, 2000; Huebner et al., 2012; Proctor et al., 2009). For example, Lyubomirsky, King, and Diener's (2005)meta-analysis revealed that life satisfaction is an antecedent of important social, vocational, and health outcomes for adults.Specifically, the authors found that adultswho reported higher levels of life satisfactionweremore likely to succeed inwork, experience

niversity of South Carolina, Columbia, SC 29208, USA. Tel.: +1 803 777 4137.

Study of School Psychology. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

588 M.D. Lyons et al. / Journal of School Psychology 51 (2013) 587–598

more satisfying social relationships (e.g., marriages and friendships), and live longer lives. Adults with higher life satisfaction werealso less likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking and drug abuse.

In a review of life satisfaction research on children and adolescents, Proctor et al. (2009) found that life satisfaction positivelycorrelated with engagement in school, quality of social relationships, and positive self-concept. The authors also found that lifesatisfaction positively correlated with physical health, goal attainment, and grade point average. Although longitudinal researchon the consequences of individual differences in life satisfaction judgments among children has been sparse, low levels of globallife satisfaction have been shown to precede decreases in adolescents' school engagement (Lewis, Huebner, Malone, & Valois,2011) and parental support (Saha, Huebner, Suldo, & Valois, 2010), as well as increases in peer relational victimization (Martin,Huebner, & Valois, 2008). The previously described literature suggests potential adverse consequences of lower levels of lifesatisfaction in adults and children. Furthermore, the extant literature suggests that global life satisfaction decreases duringadolescence. Such a finding is consistent with evidence from research conducted with samples of children in the United States(e.g., Suldo & Huebner, 2006) and elsewhere (Bradshaw, Rees, Keung, & Goswami, 2010; Chang, McBride-Chang, Stewart, & Au,2003; Goldbeck, Schmitz, Besier, Herschback, & Henrich, 2007; Leung, McBride-Chang, & Lai, 2004; Park & Huebner, 2005; Ullman& Tatar, 2001; Weber, Ruch, & Huebner, 2013).

Given the potential adverse consequences of lower levels of life satisfaction and declines in life satisfaction among adolescents,researchers have begun investigating the determinants of individual differences in life satisfaction. Although numerous antecedentshave been identified, most pertinent to this study, prominent scholars have reported that a person's display of behavior problems(e.g., externalizing disorders, internalizing disorders, psychotic disorders) is an important antecedent of low perceived quality of life(e.g., life satisfaction; see Diener & Seligman, 2004, for a review). However, these studies have been primarily limited to adults. Oneexception is a study by Shek (1998) who found a significant bidirectional relationship between a measure of composite measuresof behavior problems and positive mental health (including life satisfaction) in Chinese adolescents. Together, extant research on childand adolescent life satisfaction suggests the need for additional studies of its antecedents, including behavior problems. Clarificationof relationships between youth behavior problems and quality of life should have major implications for public policy making andindividual choices (Diener & Seligman, 2004).

Much of the existing research on children's life satisfaction has been atheoretical in nature (Huebner, 2004). However, ina review of research on life satisfaction, Evans (1994) proposed an integrative bio-social-cognitive model to explain individualdifferences in life satisfaction. The model proposed by Evans suggests that personality factors (e.g. extraversion and neuroticism),along with environmental factors (e.g. life stressors), directly and indirectly affect life satisfaction. Evans further argued that fourcognitive and behavioral mechanisms potentially mediate the relations between environmental and personality factors and lifesatisfaction. Evans defined the four variables that mediated the relations between environmental, personality, and life satisfactionas general social behaviors (e.g., maladaptive social behaviors, such as externalizing and internalizing problems), domain-specificskills (e.g., academic ability), affect, and social support. Although not all individual causal pathways have been tested within thismodel, empirical evidence exists for some of these variables as mediators between environmental and personality factors and lifesatisfaction. For example, research suggests that individual differences in social behaviors mediate the relations between personalityand environmental conditions and individuals' well-being, including life satisfaction (Argyle & Lu, 1990; Fogle, Huebner, & Laughlin,2002; Graziano, Jensen-Campbell, & Finch, 1997). Since the time that Evans proposed his model, research related to the origins andassociated psychosocial mechanisms through which life satisfaction develops in children and adolescents has grown; however, majorgaps in knowledge remain. The extant body of research, which is limited mostly to cross-sectional studies, supports portions of themodel proposed by Evans.

Nevertheless, more comprehensive longitudinal studies, incorporating a wider array of personality, environmental, andpsychosocial variables, are needed to test the model proposed by Evans (1994). In the following section, we provided an overviewof the literature related to adolescents' global life satisfaction and the constructs used to evaluate Evans' theory: personalityvariables (i.e., extraversion and neuroticism), environmental conditions (i.e., stressful life events), and maladaptive socialbehavior (e.g., externalizing and internalizing problems). These particular variables were selected because they are among thestrongest correlates of global life satisfaction (see Proctor et al., 2009, for a review). Specifically, we included neuroticism andextraversion because a meta-analysis of studies of personality traits and subjective well-being revealed that neuroticismand extraversion were significant correlates of life satisfaction (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998). Furthermore, we also examined stressfullive events, because Luhman, Hofman, Eid, and Lucas (2012) reported, in another meta-analysis, that the rate of adaptationwas much slower for many negative life events than positive life events. Finally, we included measures of both internalizing andexternalizing problems to cover the two major factors of maladaptive social behaviors in adolescents (Achenbach, 1966).

1.1. Correlates of life satisfaction

Extraversion and neuroticism constitute two of the most widely empirically validated personality variables relevant to lifesatisfaction of adolescents (Roberts &DelVecchio, 2000; Shiner & Caspi, 2003). Extraversion refers to a personality trait characterized bysociability, cheerfulness, and high activity levels, whereas neuroticism refers to a personality trait characterized by frequent negativeemotions, such as anxiety and insecurity (Cloninger, 2008). A modest but growing body of research suggests that these personalitycharacteristics are correlated with global life satisfaction in children and adolescents. For example, Greenspoon and Sasklofske (2001)found that extraversion was positively related to life satisfaction, whereas neuroticism was negatively related to life satisfaction andpositively related to psychopathology in a sample of Canadian elementary school students in grades 3 through 6. McKnight, Huebner,

589M.D. Lyons et al. / Journal of School Psychology 51 (2013) 587–598

and Suldo (2002) also found similar relations between extraversion and neuroticism and life satisfaction in a sample of Americanstudents between grades 6 through 12.

In addition to showing that personality characteristics are an important predictor of life satisfaction in children and adolescents,research also indicates that environmental differences are significant correlates of life satisfaction. Steel, Schmidt, and Shultz (2008)estimated that approximately 50% of the variability in life satisfaction was attributable to environmental variables. Environmentalvariables include stressful (or positive) life experiences, which are construed as external to the individual (McNamara, 2000).Consistentwith Evans's (1994)model, research exploring the impact of stressful life events has revealed significant relations betweenlife satisfaction andmajor uncontrollable life stressors (e.g., death of a close friend, divorce of parents, and relocation). Among adults,Headey and Waring (1989) found that stressful life events predicted additional variance in life satisfaction above and beyondpersonality characteristics (extraversion and neuroticism) in a sample of approximately 1000 Australian adults. Among youth, AshandHuebner (2001) andMcKnight et al. (2002) also demonstrated significant inverse relations between acute (and chronic) stressorsand life satisfaction.

What accounts for the relations between life satisfaction and personality predispositions and environmental circumstances?As noted previously, one proposed psychosocial mechanism in Evans's (1994)model involves general social behaviors as mediators. Inthis study, we operationalized social behaviors that were expected to relate to lower levels of global life satisfaction as maladaptivesocial behaviors, specifically externalizing and internalizing problems. Thesemaladaptive behaviors include responses that are orientedoutward to the environment (e.g., externalizing behavior such as fighting with peers) and responses that are oriented inward to theindividual (e.g., internalizing problems such as worrying). Internalizing and externalizing problems in children and adolescents haveconsistently been related to lower levels of global life satisfaction (Haranin, Huebner, & Suldo, 2007; Huebner & Alderman, 1993; Suldo& Huebner, 2006).

Furthermore, research has shown that extraversion relates negatively to internalizing problems whereas extraversion relatespositively to externalizing problems (Berdan, Keane, & Calkins, 2008; Prinzie et al., 2004). Costa and McCrae (1980) also observedthat neuroticism related positively to internalizing and externalizing problems. Finally, the frequencies of stressful life eventshave been related to externalizing and internalizing problems as well (Jaser et al., 2005; Suldo, Shaunessy, & Hardesty, 2008).In sum, the literature suggests the plausibility of a model, such as Evans's (1994) model, in which the occurrence of frequentstressful life events and particular personality characteristics predispose adolescents to engage in maladaptive social behaviors(externalizing and internalizing problems), which in turn influence their global life satisfaction.

1.2. The current study

The bulk of studies investigating the various relationships in Evans's (1994) model have been cross-sectional, limitingthe interpretation of the directionality of the relations and providing only limited support for this model. This study went beyondprevious research by evaluating Evans's model on the development of life satisfaction (1) using a longitudinal design, and(2) through the incorporation of a more comprehensive array of the determinants in the model. The longitudinal design allowedfor the prediction of both average levels of life satisfaction adjusted for covariates and linear changes in life satisfaction acrosstime. Specifically, extraversion, neuroticism and stressful life events were hypothesized to predict adolescents' global lifesatisfaction, mediated by internalizing and externalizing problems. By conducting a mediational analysis examining longitudinalchanges in life satisfaction over time, the present study was designed to answer the following three questions. First, wereextraversion, neuroticism and stressful life events related to adolescents' internalizing and externalizing problems? Second, wereinternalizing and externalizing problems related to the average level (across 2-years) or the linear change of adolescents'life satisfaction? Third, did extraversion, neuroticism, and stressful life events operate through internalizing and externalizingproblems to predict adolescents' life satisfaction?

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The data used for this study were part of an extant dataset. Analyses from this database have been reported on elsewhere(e.g., Haranin et al., 2007; Suldo & Huebner, 2006). However, the following analyses are new.

The data were gathered from five schools in a Southeastern state in the United States in the fall of each school year for twoyears. Over a period of 2-years, three waves of data were collected in the fall of each school year. At Time 1, 1201 students fromgrades 6 to 12 completed the survey. At Time 2, 689 students completed the survey, and 570 students completed the surveyat Time 3. Although there was only a 47% (n = 570) retention rate, 25% (n = 291) of students did not complete the survey at all

Table 1Sample size and descriptive statistics across the 2-year sample.

Time Age in years M (SD) % Girls % Free lunch n n Grade 6 n Grade 7 n Grade 8 n Grade 9 n Grade 10 n Grade 11 n Grade 12

T1 13.81 (1.64) 62 61 910 184 185 154 194 193 142 149T2 14.74 (1.55) 63 59 689 – 142 132 124 149 142 –

T3 15.79 (1.54) 64 55 570 – – 104 121 102 114 129

590 M.D. Lyons et al. / Journal of School Psychology 51 (2013) 587–598

three time points because they graduated from high school. Additionally, 28% (n = 340) of students did not complete the surveyat all three data collection points for unknown reasons. Although the reason for student attrition is unknown, this response rate isconsistent with other longitudinal research (Mroczek, 2007). The mean student age at Time 1 was 13.81 years (SD = 1.64 years),62% of the sample was made up of girls, and 61% of the sample participated in the free and reduced lunch program. Fifty-eightpercent of the students were African American, 34% were Caucasian, and the remainder was from other ethnic backgrounds.Sample sizes, average age and free lunch status for participants across measurement times, split by grade can be found in Table 1.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Stressful Life Events Scale (Johnson & McCutcheon, 1980)The Stressful Life Events Scale is awidely used self-reportmeasure appropriate for adolescents, inwhich respondents indicate if they

have experienced a particular stressful life event over the past 12 months. This scale includes 28 items that refer to controllable stressfullife events and 18 items that refer to uncontrollable stressful life events. For the purpose of this study, only items that referred touncontrollable stressful life events (e.g., parent's loss of job) were used. The dichotomous responses were summed to create ameasureof overall stressful life events in the past 12 months. In this study, the coefficient alpha value was equal to .75. However, the alphacoefficient should be interpreted cautiously because the stressful life events instrument is an index reflecting a composite of observedvariables in which the endorsement of one item is not expected to be related to the endorsement of other items (Streiner, 2003).

2.2.2. Abbreviated Junior Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (JEPQR-A; Francis, 1996)Students completed the 24-item version of the Abbreviated Junior Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (JEPQR-A), which was

derived from the widely used 81-item Junior Eysenck Personality Inventory (Eysenck, 1965) and an abbreviated version, the48-item Revised Junior Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (JEPQR-S; Corulla, 1990). The JEPQR-A was designed for students about7 to 15 years old, but it has been used successfully with older adolescents (e.g., Suldo & Huebner, 2006). Students responded toquestions in a “yes/no” format, with higher scores indicating higher levels of the personality trait. Francis (1996) reportedcoefficient alpha values of .66 and .70 for the Extraversion and Neuroticism subscales, respectively. The convergent validity ofthe JEPQR-A was supported by high correlations between the JEPQR-A and the JEPQR-S Extraversion scale (r = .91) as well as theNeuroticism scale (r = .91; Francis, 1996). In this study, the coefficient alpha values were .66 and .68 for the Extraversion and theNeuroticism scales, respectively.

2.2.3. Youth Self-Report Form of the Child Behavior Checklist (YSR; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1991)The YSR is a 118-item measure of self-reported behavior problems, appropriate for students of about 11 to 18 years old.

Students reported how often they engaged in the relevant behavior problems using a 3-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhator sometimes true, and 2 = very true or often true). For this study, only 61 items that constituted the Internalizing Problems andExternalizing Problems subscales were used. The Internalizing Problems subscale consists of items related to somatic complaints(9 items), depression/anxiety (16 items) and withdrawal (7 items). The Externalizing Problems subscale consists of items relatedto delinquent (11 items) and aggressive behaviors (19 items). Validity studies support the use of the YSR for distinguishingadolescents with internalizing problems (Ferdinand, 2008) as well as externalizing problems (Ebesutani, Bernstein, Martinez,Chorpita, & Weisz, 2011). Data reported in the manual and other sources indicate internal consistency estimates and 1-week testcoefficients in the .80s and validity coefficients in the .40 range between the YSR and the parent and teacher versions (Merrell,2008). In this study, the coefficient alpha values were .87 and .90 for the measures of externalizing and internalizing problemsrespectively.

2.2.4. Students' Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS; Huebner, 1991)The SLSS is a 7-item, self-report scale designed to measure global life satisfaction in children of about ages 8 to 18. Participants

respond to statements about their perceived quality of life using a 6-point Likert scale in which 1 = strongly disagree and 6 = stronglyagree. Thus, higher scores are considered an indication of higher levels of overall life satisfaction. The SLSS total score has been shown tohave moderate reliability and to be supported by several types of validity evidence for elementary, middle, and high school students(Proctor et al., 2009). For example, a coefficient alpha value of .84 has previously been reported in Huebner (1991), and its validity hasbeen supported by factor-analytic findings and expected correlations between the SLSS and related variables obtained from parentreports and teacher reports (see Huebner, Gilman, & Suldo, 2007, for a review). The coefficient alpha values in this study were .83at Time 1, .81 at Time 2, and .86 at Time 3.

2.3. Procedure

The data were obtained from three middle and two high schools in a Southeastern United States school district over a period of2-years with data collection occurring three times in the fall. Parent consent and student assent were required for participationin the study. Trained graduate students administered the measures with assistance from classroom teachers during a 30-minuteperiod in regular classroom settings in a counterbalanced fashion. Because of time constraints imposed by the school, we selectedthe briefest possible measures, with reported internal consistency reliabilities approximating or exceeding .70, reflecting theminimum criterion considered acceptable for research purposes and measuring the breadth of the psychological constructs(Boyle, 1991; Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

Extraversion

Neuroticism

Stressful life events

InternalizingProblems

ExternalizingProblems

β0i: Levels of

Life Satisfaction

β1i: Linear Change of Life Satisfaction

β1:

-0.16*

β2:

0.54*

β3:

0.14*

β2:

0.23*

β1:

0.13*

β3:

0.25*

γ04:

:

-0.21*

γ05

:

-0.15*

γ15

:

0.03

γ15

:

0.07*

Time 1 Time 1 Time 1, 2, & 3

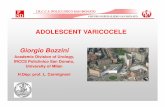

Fig. 1. Empirical model tested based on Evans's (1994) theoretical model. *p b .05.

591M.D. Lyons et al. / Journal of School Psychology 51 (2013) 587–598

2.4. Data analysis

To assess the changes in life satisfaction for each individual based on the mechanisms outlined by Evans (1994), amultimediator model was estimated with baseline stressful life events, extraversion, and neuroticism predicting the linear changeand differences in levels of life satisfaction adjusted for covariates as mediated by internalizing and externalizing problems(see Fig. 1 for the complete model that was tested). Because of the varying ages in these analyses, both age and time wereincluded as covariates. Time from first assessment (centered on the mean) was used to set the scale of the growth curves. Age atfirst assessment (also centered on the mean) was used as a covariate, which serves as a control across individuals for the effects ofdifferences in age. Because time was grand mean centered, the intercept is the predicted value of life satisfaction at the center ofthe growth curve which allows the effects on the intercept to be interpreted as effects on predicted levels of life satisfactionaveraged across the time points available for that individual and adjusted for differences between individuals in ages (Blozis &Cho, 2008). By contrast, effects on the slope of time are interpreted as effects on the linear change in life satisfaction over time.All other variables, except age and time, were converted to z-scores in order to estimate the fully mediated effect and to allow theeffects to be interpreted on a standard metric. Following the terminology introduced by MacKinnon (2008), two pathways wereestimated. The “a Path”was estimated to test the relations of predictors on the mediators. Then, the “b Path”was estimated to testthe relations of the mediators on the outcome. Finally, the product of the coefficients obtained from the “a” and “b” pathways wascalculated to test the full mediated effect of the predictors on the outcome when mediated by internalizing and externalizingproblems (for a review, see Fairchild & McQuillin, 2010). An alpha level of .05 was used throughout to determine statisticalsignificance.

2.4.1. Relations of predictors to mediators (a path)To assess the relations of the predictors to the mediators, a multivariate regression equation was estimated in which baseline

levels of extraversion, neuroticism, and stressful life events were used to predict baseline levels of internalizing and externalizingproblems using the base package for R version 2.15.1. These parameters were estimated only at Time 1 and do not reflect changeslongitudinally (see Eq. 1).

Internþ Extern ¼ β0 þ β1 Extraversionð Þ þ β2 Neurotð Þ þ β3 Stressð Þ þ β4 Ageð Þ þ rit: ð1Þ

592 M.D. Lyons et al. / Journal of School Psychology 51 (2013) 587–598

2.4.2. Relations of mediators to criterion variables (b path)The relations of these predictors on the levels of life satisfaction were assessed with a multilevel model. The multilevel model

was estimated with a random effect for the intercept and for time and fixed effects for extraversion, neuroticism, stressful lifeevents, internalizing problems, and externalizing problems (see Eq. (2)).

Table 2Parame

Media

Intern

Exter

Note. *p

LSit¼ γ00þγ01 Extraversionð Þþγ02 Neurotð Þþγ03 Stressð Þþγ04 Internð Þþγ05 Externð Þþγ07 Ageð Þþγ10 Timeð Þþγ11 Extraversion � Timeð Þþγ12 Neurot � Timeð Þþγ13 Stress � Timeð Þþγ14 Intern � Timeð Þþγ15 Extern � Timeð Þþu0tþu1t Timeð Þþrit:

ð2Þ

The mediators' associations with the level in individual life satisfaction were estimated using the main effects of internalizingand externalizing problems on life satisfaction. Linear change in life satisfaction as a function of the mediating variables wasestimated using the interactions between time and maladaptive problems (i.e., internalizing and externalizing behaviors).An additional advantage of using a multilevel model is that data for students who were not present at every time point can still beincluded in the analysis, potentially resulting in less bias than the use of listwise deletion (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

2.4.3. Relations of the predictors to the criterion variables (ab path)The relation of the predictors to the criterion variables was estimated to examine the relations between the personality and

stressful life event variables and life satisfaction when mediated by internalizing and externalizing problems. Alwin and Hauser(1975) described this indirect effect as the change that occurs when the independent variables of interest operate to influence themediator variables that in turn influence the dependent variables. The product of the beta coefficients from the “a” and “b” pathswas calculated to obtain an estimate of the fully mediated effect for each pathway. As described by MacKinnon (2008), thestandard errors estimated from multimediator models are inaccurate because the product of two normal sampling distributionsdoes not result in a normal sampling distribution. Following MacKinnon, an empirical sampling distribution for each mediatedpathway was estimated, and confidence intervals for each pathway were constructed. Confidence intervals for the mediatedpathways were estimated from using bootstrapped data with 500 iterations and were drawn from the individual level using thebase package in R version 2.15.1.

3. Results

3.1. Relations of predictors to mediators (a Path)

To assess the relations between the predictors and mediators, a multivariate regression equation was estimated in whichextraversion, neuroticism, and stressful life events were used to predict internalizing and externalizing problems with studentage included as a covariate. Table 2 shows the standardized parameter estimates and standard errors of these analyses, and Fig. 1shows these results in the context of the complete model that was tested. The covariate, student age, was significantly relatedto internalizing problems, t(1192) = −2.22, p = .03, but not externalizing problems, t(1192) = 1.36, p = .18. However, eachestimate represented a small effect size (cf. Cohen, 1988).

Extraversion significantly predicted both internalizing problems, t(1192) = −6.93, p b .001, and externalizing problemsat Time 1, t(1192) = 4.50, p b .001. The standardized parameter estimate for extraversion predicting internalizing problems was−0.16, and the standardized parameter estimate for extraversion predicting externalizing problems was 0.13. Because theseparameters are standardized, a one standard deviation increase in extraversion represents a 0.16 standard deviation decrease ininternalizing problems and a 0.13 standard deviation increase in externalizing problems controlling for all other predictors in themodel. These effects represent small effect sizes (Cohen, 1988). Neuroticism was found to significantly predict both internalizingproblems, t(1192) = 22.91, p b .001, and externalizing problems, t(1192) = 8.16, p b .001. The standardized parameter

ter estimates for relations of predictors to mediators (a path).

tor Predictor β SE t

alizing problemsIntercept −0.002 0.001 0.04Age b0.01 b0.01 −2.22*Extraversion −0.16 0.02 −6.93*Neuroticism 0.54 0.02 22.91*Stressful life events 0.14 0.02 6.38*

nalizing problemsIntercept b0.01 0.03 0.01Age −0.001 0.001 1.36Extraversion 0.13 0.03 4.50*Neuroticism 0.23 0.03 8.16*Stressful life events 0.25 0.03 9.00*

b .05.

593M.D. Lyons et al. / Journal of School Psychology 51 (2013) 587–598

estimate for neuroticism predicting internalizing problems was 0.54, and the standardized parameter estimate for neuroticismpredicting externalizing problems was 0.23 controlling for all other predictors in the model.

Stressful life events significantly predicted both internalizing problems, t(1192) = 6.37, p b .001, as well as externalizingproblems, t(1192) = 9.00, p b .001. The standardized parameter for stressful life events predicting internalizing problems was0.14 and the standardized parameter for stressful life events predicting externalizing problems was 0.25 controlling for all otherpredictors in the model. Both of these parameters represent small effect sizes (Cohen, 1988).

3.2. Relations of mediators to criterion variables (b Path)

Prior to running a full model, an unconditional model was run to assess the between-individual variability in life satisfactionover time. The intraclass correlation obtained from this model found that 55% of the variance in life satisfaction was explainedby between-individual differences, whereas 45% of the variance in life satisfaction was explained by within-individual differencesover time. Next, a second model was run to test the longitudinal effect of internalizing and externalizing problems on lifesatisfaction. Table 3 provides the complete results of these analyses and shows that internalizing and externalizing problemssignificantly predicted levels in life satisfaction. Internalizing problems significantly predicted levels in life satisfaction,t(1190) = −5.77, p b .001, as well as linear change in life satisfaction, t(1389) = −2.27, p = .02. Results also showed thatinternalizing problems related to the linear change of life satisfaction such that students with higher internalizing problemsoverall had lower levels of life satisfaction but increased their life satisfaction at a faster rate such that after 2-years there wasno longer a predicted difference in life satisfaction between those at different levels of internalizing problems controlling for allother predictors in the model. To illustrate the predicted to change in life satisfaction across individuals with different baselinelevels of internalizing problems, Fig. 2 shows the predicted trajectory of life satisfaction for participants who were at the 16th and84th percentiles of internalizing behaviors.

Externalizing problems significantly predicted levels in life satisfaction, t(1190) = −4.89, p b .001, but did not significantlypredict linear change in life satisfaction. The standardized parameter estimate that represented levels in life satisfaction equaled−0.15. This parameter was interpreted as a 0.15 standard deviation decrease in the level of life satisfaction for every one standarddeviation unit increase in externalizing problems controlling for all other predictors in the model. To illustrate the predicted tochange in life satisfaction across individuals with different baseline levels of externalizing problems, Fig. 3 shows the predictedtrajectory of life satisfaction for participants who were at the 16th and 84th percentiles of externalizing behaviors.

3.3. Relations of the predictors to the criterion variables (ab Path)

Based on the empirical sampling distributions of 500 bootstrapped datasets, 95% confidence intervals were constructed toassess the effect of the predictors on the outcomes. Confidence intervals that do not contain zero indicate a statistically significanteffect at p b .05. The estimated parameters and confidence intervals for the relations of the predictors to the criterion variables arereported in Table 4.

None of the confidence intervals that represented the mediated pathways predicting differences in the levels of life satisfactioncontained zero, thus indicating statistically significant effects. These findings suggest that internalizing and externalizing problems

Table 3Parameter estimates for relations of mediators to criterion variables (b path).

Parameter Unconditional model Full model

Fixed effects β SE β SE

Intercept (γ00) −0.01 0.02 −0.04 0.02Extraversion (γ01) 0.07⁎ 0.03Neuroticism (γ03) −0.13⁎ 0.03Stressful life events (γ04) −0.07⁎ 0.03Internalizing Problemsa (γ05) −0.21⁎ 0.07Externalizing Problemsa (γ06) −0.15⁎ 0.03Age (γ07) −0.002⁎ 0.001Time (γ10) −0.03 0.02Time ∗ Extraversion (γ11) −0.02 0.02Time ∗ Neuroticism (γ12) 0.01 0.03Time ∗ Stress (γ13) 0.02 0.02Time ∗ Internalizing Problemsb (γ14) 0.07⁎ 0.03Time ∗ Externalizing Problemsb (γ15) 0.03 0.03

Random effects Variance Variance r between τ00 and τ10

Intercept (τ00) 0.42Time (τ10) 0.37 0.37Residual (σ2) 0.45 0.35

Note. a“b” path for predicting levels in life satisfaction. b“b” path for predicting linear change of life satisfaction.⁎ p b .05.

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

1 3

Lif

e Sa

tisfa

ctio

n (z

-sco

res)

Time

Individual at the 16th percentile of internalizing problems

Individual at the 84th percentile of internalizing problems

Fig. 2. Predicted trajectories of life satisfaction as a function of internalizing problems.

594 M.D. Lyons et al. / Journal of School Psychology 51 (2013) 587–598

mediated the effects of extraversion, neuroticism, and stressful life events on levels of life satisfaction. Despite statistically significanteffects, all pathways had very small effect sizes (ranging from −0.11 to 0.03). The confidence intervals for the pathways predictinglinear change in life satisfactionwere only significant for pathwayswith internalizing problems as amediator. However, the effect sizesfor these pathways were also small, with a range between −0.01 and 0.04.

4. Discussion

Quality of life research is only just beginning to elucidate the psychosocial mechanisms through which life satisfactiondevelops, is maintained, or changes over time. This paper represents the first formal attempt using longitudinal data toempirically test Evans's (1994) model of the development of global life satisfaction in adolescents. The model proposed by Evanssuggests that personality factors, along with environmental factors, directly and indirectly affect life satisfaction. Evans furtherargued that a variety of cognitive and behavioral mechanisms potentially mediate the relations between global life satisfactionand environmental and personality variables. Specifically, this study tested the relations between adolescents' global lifesatisfaction and selected personality characteristics and life stressors across a 2-year time period, when mediated by two types ofmaladaptive social behaviors (i.e., internalizing and externalizing problems). The results from these analyses, therefore, providepartial empirical support for Evans's theoretical model of life satisfaction. Extraversion, neuroticism, and stressful life events allsignificantly predicted behavior problems. Additionally, internalizing and externalizing behavior problems significantly predictedlevels of life satisfaction. However, only internalizing behaviors predicted linear change in life satisfaction across a 2-year period.The current study supports previous research, indicating that individuals' maladaptive social behaviors are directly related to a

-0.25

-0.2

-0.15

-0.1

-0.05

0

0.05

0.1

0.15

0.2

1 3

Lif

e Sa

tisfa

ctio

n (z

-sco

res)

Time

Individual atthe 16th percentile ofexternalizingproblems

Individual at the 84th percentile of externalizingproblems

Fig. 3. Predicted trajectories of life satisfaction as a function of externalizing problems.

Table 4Parameter estimates for relations of the predictors to the criterion variables (ab path).

Mediated pathways Levels of LS Linear growth of LS

Predictor Mediator β 95% CI β 95% CI

Extraversion Internalizing Problems 0.03⁎ [0.020, 0.051] −0.01⁎ [−0.018, −0.001]Neuroticism Internalizing Problems −0.11⁎ [−0.150, −0.078] 0.04⁎ [0.003, 0.054]Stressful life events Internalizing Problems −0.03⁎ [−0.044, −0.019] 0.02⁎ [0.001, 0.015]Extraversion Externalizing Problems −0.02⁎ [−0.030, −0.008] 0.00 [−0.008, 0.012]Neuroticism Externalizing Problems −0.04⁎ [−0.050, −0.020] 0.00 [−0.002, 0.020]Stressful life events Externalizing Problems −0.04⁎ [−0.052, −0.021] 0.00 [−0.002, 0.020]

Note. LS = life satisfaction.⁎ p b .05.

595M.D. Lyons et al. / Journal of School Psychology 51 (2013) 587–598

number of variables, including key personality traits and stressful life experiences. Maladaptive social behaviors, in turn, relateto reduced levels of life satisfaction.

The results indicated that the complete model significantly predicted levels in life satisfaction, supporting the hypothesisthat stressful life events, personality factors, and maladaptive problems relate to adolescents' global life satisfaction. However,the complete model did not significantly predict the linear change of life satisfaction across time. Rather, the relations amongpersonality, stressful life events, and the linear change of life satisfaction were significantly related only through the internalizingproblems pathway. In addition to the overall findings, specific implications for each of the research questions were identified andare addressed in the paragraphs that follow.

First, we addressed the statistical significance and magnitude of the relations between the predictor variables and the mediatorvariables. The results of the analyses suggested small to moderate relations among extraversion, neuroticism, and stressful life eventsand externalizing and internalizing problems based on parameter estimates. These results are consistent with previous research thatsuggests personality and life stressors are related tomaladaptive social behaviors (Ash & Huebner, 2001;McKnight et al., 2002; Proctoret al., 2009; Steel et al., 2008). These findings provide important insight about the relation of exogenous factors (i.e., personality traitsand environmental stressors) to individuals' behavioral responses. Specifically, the results suggest that adolescentswith higher levels ofextraversion report fewer internalizing problems and more externalizing problems, which is consistent with personality researchnoting that extraverted individuals tend to engage in problems that are oriented outward toward their environment (Berdan et al.,2008; Prinzie et al., 2004). Moreover, adolescents with higher levels of neuroticism reported more internalizing and externalizingproblems. These results are consistent with previous research that has supported the significant link between neuroticism andinternalizing and externalizing problems (e.g., Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989).

Second, we evaluated the statistical significance and magnitude of the relations between the mediator variables and levels ofadolescents' life satisfaction as well as change in life satisfaction. The results of these analyses showed that both internalizing andexternalizing problems were negatively related to levels in global life satisfaction. Previous research has found similar, negativerelations between these maladaptive social behaviors and life satisfaction (Carver et al., 1989; Suldo & Huebner, 2006; Zimmer‐Gembeck, Lees, & Skinner, 2011). However, this study extended previous research by examining these effects longitudinally. Thisstudy demonstrated that the association between internalizing problems and global life satisfaction did not persist across therelevant time period. In fact, children with higher levels of internalizing problems at Time 1 saw increases in the linear change oflife satisfaction at Time 3, which suggests that this association does not continue for individuals over the 2-year period. Given thatadolescents' self-reports of internalizing problems are less stable than externalizing problems (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), it ispossible that internalizing problems have decreasing relations with adolescents' global life satisfaction whereas externalizingproblems have more persistent relations with adolescents' global life satisfaction. It is also possible that the finding related tointernalizing problems may reflect the phenomenon of regression toward the mean. That is, extreme student responses may havetended toward the mean in subsequent survey administrations reducing the association between internalizing problems and lifesatisfaction. Although variations in the linear change of behavior problems were not predicted, they extend previous researchby suggesting differential outcomes related to the relations between adolescents' perceived quality of life and internalizingand externalizing problems. Overall, the results of this study do support the general premise of Evans's (1994) theoretical modelin that maladaptive social behaviors were significantly related to individual differences in levels of global life satisfaction.

Third, we addressed whether externalizing problems, and internalizing problems mediated the relations among stressful lifeevents, personality variables, and the mean differences and the linear change of life satisfaction. The results of the analyses foundthat the pathways,which contained internalizing problems as amediator, significantly predicted both levels of life satisfaction aswell aschanges in the linear change of life satisfaction. However, the effect sizes for the mediated pathways that contained internalizingproblems represented small effects. The pathways that contained externalizing problems as a mediator were significant predictors oflevels of life satisfaction, but not change over time. These results are consistent with the few studies that have examined the relationbetween maladaptive social behaviors, personality, and life satisfaction (Bolger, 1990; Fogle et al., 2002; Long & Sangster, 1993).

Overall, this study presents additional empirical support for the findings of cross-sectional research, which have consistentlyindicated a link between neuroticism and maladaptive social behaviors, like internalizing and externalizing problems.

596 M.D. Lyons et al. / Journal of School Psychology 51 (2013) 587–598

Additionally, the results also supported the mediating role of internalizing problems in the relation between life satisfactionand the stressful life events and personality variables. The results support the general premise of Evans's (1994) theoretical modelthat (maladaptive) social behavior represents a behavioral mechanism linking personality and stressful life events to thedevelopment of individual differences in life satisfaction. That is, maladaptive social behaviors appear to mediate the relationbetween life satisfaction and personality traits (e.g., neuroticism) and environmental variables (e.g., stressful life events).Finally, the use of multilevel modeling allowed an examination of between-person differences (i.e., levels of life satisfaction) aswell as within-person changes in life satisfaction longitudinally, thus leading to the finding that internalizing problems weresignificantly related to lower levels of life satisfaction and increases in the linear change of individual life satisfaction reportsacross time.

4.1. Implications for practice

The results of this study speak to the salience of maladaptive social behaviors in adolescents' quality of life. Specifically, thefindings implicate maladaptive social behaviors, both internalizing and externalizing problems, as antecedents of reduced levelsof global life satisfaction among adolescents. Furthermore, the findings suggest that somewhat stable personality characteristics(i.e., extraversion and neuroticism) and prior stressful life events are antecedents of internalizing and externalizing problems.

Taken together, these findings should inform efforts to prevent or reduce maladaptive social behaviors as well as enhance thequality of life of adolescents. For example, prevention efforts using sophisticated psychological screening systems that reflectcomprehensive assessment of personality and life events, as well as indicators of subjective well-being (e.g., life satisfaction)along with the traditional indicators of psychopathology could be critical in accurately identifying at-risk youth. According toSuldo et al. (2011), individuals who experience low well-being and high psychopathology are at the most risk for negativeoutcomes, followed by those who experience low well-being and low psychopathology. Whatever the case, the findings of thisresearch are consistent with studies of adults that suggest that maladaptive social behaviors (e.g., externalizing and internalizingproblems) can play an important role in adolescents' quality of life (Diener & Seligman, 2004).

4.2. Limitations and future directions

Although this study provides initial empirical evidence to support Evans's (1994) theoretical model of life satisfactiondevelopment, future studies need to be conducted to provide additional support for this theory of the development of lifesatisfaction in adolescents. Future studies should strive to extend this study in several major ways.

First, future studies should test adaptive and maladaptive social behaviors as mediators of personality, stressful life events,and life satisfaction. This study tested the relations between life satisfaction and only two specific types of maladaptive socialbehaviors (i.e., internalizing and externalizing problems) as mediators; however, research has suggested that additional socialbehaviors may be related to life satisfaction, especially increasing life satisfaction. For example, Chao (2011) found that direct,prosocial problem-solving behaviors were associated with higher life satisfaction in a sample of college students. Further,as children grow older, particularly in adolescence, their behavioral repertoires expand and become more diverse (Zimmer‐Gembeck et al., 2011); thus, adolescents should become better able to match effective behavior to the perceived context ofthe stressor (Compas, Connor-Smith, & Jaser, 2004). Hence, future studies that incorporate a broader range of adaptive andmaladaptive social behaviors within specific contexts will provide more comprehensive information regarding the likely complexnature of how social behavior mediates the effect of personality processes and stressful life events on changes in adolescents' lifesatisfaction.

Second, future studies may test this relationship across different time periods. Although this study found statisticallysignificant effects for many of the pathways hypothesized by Evans (1994), the associated effect sizes were relatively small.Because developmental research suggests that changes in adolescent life satisfaction may occur in earlier years (i.e., during thetransition to secondary school), it is possible that these mechanisms may influence changes in adolescent life satisfaction morequickly than tested in this study. Nevertheless, the findings are impressive given that the predictors are related to changes inglobal life satisfaction across a 2-year time period during adolescence.

Third, future studies should strive to test this model using more diverse samples of students to test the generalizability of thismodel. The sample used in this study was relatively homogeneous and the proposed mechanisms may not operate in the samemanner for all populations. For example, Park and Huebner (2005) found that conceptualizations and correlates of life satisfactiondiffered across samples of American and Korean adolescents. Thus, future cross-cultural research with adolescents is needed toevaluate the applicability of Evans's (1994) model across different cultures.

Finally, studies employing experimental designs (e.g., randomized control intervention studies) will also be needed to formulatestrong conclusions regarding causal relations between life satisfaction and its antecedent variables. Although the longitudinal designof this study represented an advance relative to previous cross-sectional studies, the derivation of causal inferences is still limited giventhe inability to rule out all possible causal influences (e.g., unmeasured third variables that influence the predictor and criterionvariables). A full understanding of the interrelationships among personality, environmental, social behavior, and life satisfactionvariables will require converging evidence from a number of complementary methodologies, including both experimental and quasi-experimental studies (Diener & Chan, 2011).

597M.D. Lyons et al. / Journal of School Psychology 51 (2013) 587–598

References

Achenbach, T. M. (1966). The classification of children's psychiatric symptoms: A factor analytic study. Psychological Monographs, 80, 1–37.Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. S. (1991). Youth Self-Report Manual. Burlington, VT: Author.Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001).Manual for the ASEBA School-age Forms and Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children,

Youth and Families.Alwin, D. F., & Hauser, R. M. (1975). The decomposition of effects in path analysis. American Sociological Review, 40, 37–47.Antaramian, S., Huebner, E. S., Hills, K. J., & Valois, R. F. (2010). A dual-factor model of mental health: Toward a more comprehensive understanding of youth

functioning. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80, 462–472. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01049.x.Argyle, M., & Lu, L. (1990). Happiness and social skills. Personality and Individual Differences, 11, 1255–1261. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(90)90152-H.Ash, C., & Huebner, E. (2001). Environmental events and life satisfaction reports of adolescents: A test of cognitive mediation. School Psychology International, 22,

320–336. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0143034301223008.Berdan, L. E., Keane, S. P., & Calkins, S. D. (2008). Temperament and externalizing behavior: Social preference and perceived acceptance as protective factors.

Developmental Psychology, 44, 957–968.Blozis, S., & Cho, Y. (2008). Coding and centering of time in latent curve models in the presence of interindividual time heterogeneity. Structural Equation Modeling,

15, 413–433. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10705510802154299.Bolger, N. (1990). Coping as a personality process: A prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 525–537. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1037/0022-3514.59.3.525.Boyle, G. J. (1991). Does item homogeneity indicate internal consistency or item redundancy in psychometric scales? Personality and Individual Differences, 12,

291–294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(91)90115-R.Bradshaw, J., Rees, G., Keung, A., & Goswami, H. (2010). The subjective well-being of children. In C. McAuley, & W. Rose (Eds.), Child Well-being: Understanding

Children's Lives (pp. 181–204). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56,

267–283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267.Chang, L., McBride-Chang, C., Stewart, S. M., & Au, E. (2003). Life satisfaction, self-concept, and family relations in Chinese adolescents and children. International

Journal of Behavioral Development, 27, 182–189. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650250244000182.Chao, R. (2011). Managing stress and maintaining well-being: Social support, problem-focused coping, and avoidant coping. Journal of Counseling and

Development, 89, 338–348. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00098.x.Cloninger, S. (2008). Theories of Personality (5th ed.)Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.)Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J., & Jaser, S. S. (2004). Temperament, stress reactivity, and coping: Implications for depression in childhood and adolescence. Journal

of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 21–31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_3.Corulla, W. J. (1990). A revised version of the psychoticism scale for children. Personality and Individual Differences, 11, 65–76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(90)

90169-R.Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1980). Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 38, 668–678. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.38.4.668.DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 124,

197–229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.197.Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55, 34–43. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34.Diener, E., & Chan, M. Y. (2011). Happy people live longer: Subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 3,

1–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01045.x.Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5, 1–31. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00501001.x.Ebesutani, C., Bernstein, A., Martinez, J. I., Chorpita, B. F., & Weisz, J. R. (2011). The youth self report: Applicability and validity across younger and older youths.

Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40, 338–346. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2011.546041.Evans, D. R. (1994). Enhancing quality of life in the population at large. Social Indicators Research, 33, 47–88. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01078958.Eysenck, S. B. G. (1965). Manual of the Junior Eysenck Personality Inventory. London, UK: University of London Press.Fairchild, A. J., & McQuillin, S. D. (2010). Evaluating mediation and moderation effects in school psychology: A presentation of methods and review of current

practice. Journal of School Psychology, 48, 53–84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2009.09.001.Ferdinand, R. F. (2008). Validity of the CBCL/YSR DSM-IV scales anxiety problems and affective problems. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 126–134. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.01.008.Fogle, L. M., Huebner, E. S., & Laughlin, J. E. (2002). The relationship between temperament and life satisfaction in early adolescence: Cognitive and behavioral

mediation models. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 372–392. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1021883830847.Francis, L. J. (1996). The development of an abbreviated form of the revised Junior Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (JEPQR-A) among 13–15 year olds.

Personality and Individual Differences, 21, 835–844. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00159-6.Goldbeck, L., Schmitz, T. G., Besier, T. G., Herschback, P., & Henrich, G. (2007). Life satisfaction decreases during adolescence. Quality of Life Research, 16, 969–979.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11136-007-9205-5.Graziano, W. G., Jensen-Campbell, L. A., & Finch, J. F. (1997). The self as a mediator between personality and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 73, 392–404. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.2.392.Greenspoon, P. J., & Sasklofske, D. H. (2001). Toward an integration of SWB and psychopathology. Social Indicators Research, 54, 81–108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:

1007219227883.Haranin, E. C., Huebner, E., & Suldo, S. M. (2007). Predictive and incremental validity of global and domain-based adolescent life satisfaction reports.

Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 25, 127–138. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0734282906295620.Headey, B., & Waring, A. (1989). Personality, life events, and subjective well-being: Toward a dynamic equilibrium model. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 57, 731–739. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.4.731.Huebner, E. (1991). Initial development of the Student's Life Satisfaction Scale. School Psychology International, 12, 231–240. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0143034391123010.Huebner, E. S. (2004). Research on assessment of life satisfaction in children and adolescents. Social Indicators Research, 66, 3–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:

SOCI.0000007497.57754.e3.Huebner, E., & Alderman, G. L. (1993). Convergent and discriminant validation of a children's life satisfaction scale: Its relationship to self- and teacher-reported

psychological problems and school functioning. Social Indicators Research, 30, 71–82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01080333.Huebner, E. S., Gilman, R., & Ma, C. (2012). Subjective life satisfaction. In K. Land, J. Sirgy, & A. C. Michalos (Eds.), Handbook of Social Indicators and Quality of Life

Research (pp. 355–373). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.Huebner, E. S., Gilman, R., & Suldo, S. M. (2007). Assessing perceived quality of life in children and youth. In S. R. Smith, & L. Handler (Eds.), The Clinical Assessment

of Children and Adolescents: A Practitioner's Handbook (pp. 347–363). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.Jaser, S. S., Langrock, A. M., Keller, G., Merchant, M. J., Benson, M. A., Reeslund, K., et al. (2005). Coping with the stress of parental depression II: Adolescent and

parent reports of coping and adjustment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 193–205. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_18.Johnson, J. H., & McCutcheon, S. (1980). Assessing life stress in older children and adolescents: Preliminary findings with the Life Events Checklist. In I. G. Sarason,

& C. D. Spielberger (Eds.), Stress and Anxiety (pp. 111–125). Washington, DC: Hemisphere Press.

598 M.D. Lyons et al. / Journal of School Psychology 51 (2013) 587–598

Leung, C. W. Y., McBride-Chang, C., & Lai, B. P. Y. (2004). Relations among maternal parenting style, academic competence, and life satisfaction in Chinese earlyadolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence, 24, 113–143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0272431603262678.

Lewis, A. D., Huebner, E. S., Malone, P. S., & Valois, R. F. (2011). Life satisfaction and engagement among adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 249–262.http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9517-6.

Long, B. C., & Sangster, J. I. (1993). Dispositional optimism/pessimism and coping strategies: Predictors of psychosocial adjustment of rheumatoid andosteoarthritis patients. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23, 1069–1091. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1993.tb01022.x.

Luhman, M., Hofman, W., Eid, M., & Lucas, R. E. (2012). Subjective well-being and adaptation to life events: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and SocialPsychology, 102, 592–615. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0025948.

Lyons, M. D., Huebner, E. S., & Hills, K. J. (2012). The dual-factor model of mental health: A short-term longitudinal study of school-related outcomes.Social Indicators Research, 54, 1–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0161-2.

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803–855.http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803.

MacKinnon (2008). Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.Martin, K., Huebner, E. S., & Valois, R. F. (2008). Does life satisfaction predict adolescent victimization experiences? Psychology in the Schools, 45, 705–714.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pits.20336.McKnight, C. G., Huebner, E., & Suldo, S. (2002). Relationships among stressful life events, temperament, problem behavior, and global life satisfaction in

adolescents. Psychology in the Schools, 39, 677–687. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pits.10062.McNamara, S. (2000). Stress in Young People: What's New and What Can We Do? New York, NY: Continuum.Merrell, K. W. (2008). Behavioral, Social, and Emotional Assessment of Children and Adolescents (3rd ed.)New York: Erlbaum.Mroczek, D. K. (2007). The analysis of longitudinal data in personality research. In R. W. Robins, R. C. Fraley, & R. F. Krueger (Eds.), Handbook of Research Methods

in Personality Psychology (pp. 543–556). New York, NY: Guilford Press.Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, J. H. (1994). Psychometric Theory (3rd ed.)New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.Park, N., & Huebner, E. (2005). A cross-cultural study of the levels and correlates of life satisfaction among adolescents. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36,

444–456. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022022105275961.Prinzie, P., Onghena, P., Hellinckx, W., Grietens, H., Ghesquière, P., & Colpin, H. (2004). Parent and child personality characteristics as predictors of negative

discipline and externalising problem behaviour in children. European Journal of Personality, 18, 73–102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/per.501.Proctor, C. L., Linley, P., & Maltby, J. (2009). Youth life satisfaction: A review of the literature. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10, 583–630. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1007/s10902-008-9110-9.Raudenbush, S., & Bryk, A. (2002). Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods (2nd ed.)Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Roberts, B. W., & DelVecchio, W. F. (2000). The rank–order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old-age: A quantitative review of longitudinal

studies. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 3–25.Saha, R., Huebner, E. S., Suldo, S. M., & Valois, R. F. (2010). A longitudinal study of adolescent life satisfaction and parenting. Child Indicators Research, 3, 149–165.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12187-009-9050-x.Seligman, M. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2001). Positive psychology: An introduction: Reply. American Psychologist, 56, 89–90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.1.89.Shek, D. T. (1998). Adolescent positive mental health and psychological symptoms: A longitudinal study in a Chinese context. Psychologia: An International Journal

of Psychology in the Orient, 41, 217–225.Shin, D. C., & Johnson, D. M. (1978). Avowed happiness as an overall assessment of the quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 5, 475–492. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1007/BF00352944.Shiner, R., & Caspi, A. (2003). Personality differences in childhood and adolescence: Measurement, development, and consequences. Journal of Child Psychology

and Psychiatry, 44, 2–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00101.Steel, P., Schmidt, J., & Shultz, J. (2008). Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 138–161. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.138.Streiner, D. L. (2003). Being inconsistent about consistency: When coefficient alpha does and does not matter. Journal of Personality Assessment, 80, 217–222.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA8003_01.Suldo, S. M., & Huebner, E. (2006). Is extremely high life satisfaction during adolescence advantageous? Social Indicators Research, 78, 179–203. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1007/s11205-005-8208-2.Suldo, S. M., Shaunessy, E., & Hardesty, R. (2008). Relationships among stress, coping, and mental health in high-achieving high school students. Psychology in the

Schools, 45, 273–289. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pits.20300.Suldo, S., Thalji, A., & Ferron, J. (2011). Longitudinal academic outcomes predicted by early adolescents' subjective well-being, psychopathology, and mental

health status yielded from a dual factor model. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6, 17–30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2010.536774.Ullman, C., & Tatar, M. (2001). Psychological adjustment among Israeli adolescent immigrants: A report on life satisfaction, self-concept and self-esteem.

Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30, 449–464. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1010445200081.Weber, M., Ruch, W., & Huebner, E. S. (2013). Adaptation and initial validation of the German version of the Students' Life Satisfaction Scale (German SLSS).

European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 29, 105–112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000133.Zimmer‐Gembeck, M. J., Lees, D., & Skinner, E. A. (2011). Children's emotions and coping with interpersonal stress as correlates of social competence. Australian

Journal of Psychology, 63, 131–141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9536.2011.00019.x.